1. Introduction

Hypertension is a nearly ubiquitous comorbidity in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), affecting over the vast majority of individuals across all stages of renal impairment [

1]. Raised blood pressure (BP) reflects underlying pathophysiologic disturbances but also create a veritable vicious cycle by accelerating the progression of renal dysfunction and substantially increases cardiovascular risk [

2]. Indeed, even modest elevations in systolic blood pressure (SBP) have been clearly associated with faster declines in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), increased left ventricular hypertrophy, and greater incidence of heart failure and stroke [

3,

4]. This bidirectional relationship forms a complex and self-perpetuating cycle that demands nuanced clinical management, notwithstanding the limitations of current clinical models [

5].

Despite the high prevalence and clinical importance of hypertension in CKD, control rates remain suboptimal and indeed resistant or refractory hypertension—defined as BP above goal despite three or more antihypertensive agents, including a diuretic—is disproportionately common in this population [

6], with key challenges primarily arising from altered drug pharmacokinetics, volume overload, neurohormonal activation, and diagnostic pitfalls such as white-coat hypertension or pseudohypertension [

7]. Furthermore, therapeutic inertia, reluctance to escalate renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockade in advanced CKD, and misconceptions about hemodynamic stability in dialysis patients compound the difficulty of effective BP management [

8].

This comprehensive review aims to poignantly dissect the major pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying hypertension in renal insufficiency, examine current evidence for pharmacologic and device-based treatment options, and confront widespread myths that hinder optimal care. We place special emphasis on the evolving role of renal denervation (RDN) and the importance of tailoring strategies to diverse clinical scenarios, including dialysis and transplant settings [

9,

10]. Our goal is to provide clinicians with a clear, evidence-informed framework for managing hypertension in CKD—one that integrates mechanistic understanding, critical appraisal of therapeutic efficacy, and pragmatic consideration of patient-centered outcomes.

2. Umbrella Review on Hypertension in Chronic Kidney Disease

Before perusing the evidence base on hypertension and chronic kidney disease, we aimed at searched and appraising systematic reviews on this topic. Accordingly, PubMed was queried on December 29, 2025, using the following string: hypertension AND (‘renal failure’ OR nephropathy OR ESRD) AND systematic[sb]. From a total of 1,149 hits, we finally included five systematic reviews, with three centered on dialysis populations and two addressing kidney–BP questions outside strict ESRD cohorts [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The dialysis reviews examined intradialytic hypertension or hypotension, antihypertensive strategies, and proposed target ranges, including one meta-analysis restricted to randomized trials [

12,

13,

15]. The non-dialysis reviews focused on renal biopsy findings in malignant hypertension and on associations between Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet adherence with eGFR and albuminuria outcomes [

11,

14].

Across dialysis-focused reviews, intradialytic blood pressure instability was repeatedly associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes and higher mortality risk, largely in observational evidence. Definitions of intradialytic hypertension and hypotension, timing of measurements, dialysis prescriptions, and adjustment for volume status varied, limiting comparability and leaving substantial potential for confounding and reverse causation.

The randomized-trial meta-analysis suggested that BP–lowering interventions in hypertensive hemodialysis patients reduce all-cause mortality, with the pooled estimate favoring active treatment [

12]. On this basis, authors proposed systolic values below roughly 140 mmHg as a plausible target, while emphasizing few trials and incomplete reporting of blinding procedures. Trial populations, drug classes, and BP ascertainment differed, so the pooled estimate should be interpreted as suggestive rather than definitive guidance for universal targets.

Complementary qualitative synthesis emphasized that BP control in renal failure is not purely pharmacologic and is tightly coupled to fluid management and dialysis delivery. It highlighted dry-weight optimization, sodium balance, and careful timing or withholding of medications to prevent intradialytic hypotension, while noting limited evidence for a single “ideal” interdialytic or intradialytic range.

In malignant hypertension, a large systematic review of kidney histology found frequent thrombotic microangiopathy and other severe vascular and glomerular lesions, reinforcing that extreme hypertensive states can precipitate profound renal dysfunction [

14]. Because biopsies are selectively performed and reporting is heterogeneous, lesion prevalence estimates likely reflect referral and indication biases rather than population-representative rates.

In chronic kidney disease, a DASH diet systematic review and meta-analysis reported small, statistically uncertain differences in eGFR by adherence level and sparse albuminuria reporting, with most evidence from a few cohorts using self-reported intake measures [

11]. Taken together, the evidence supports individualized care using out-of-chair BP assessment, rigorous volume and sodium management, and judicious antihypertensive selection aligned with dialysis timing and symptom burden.

3. Pathophysiological Mechanisms

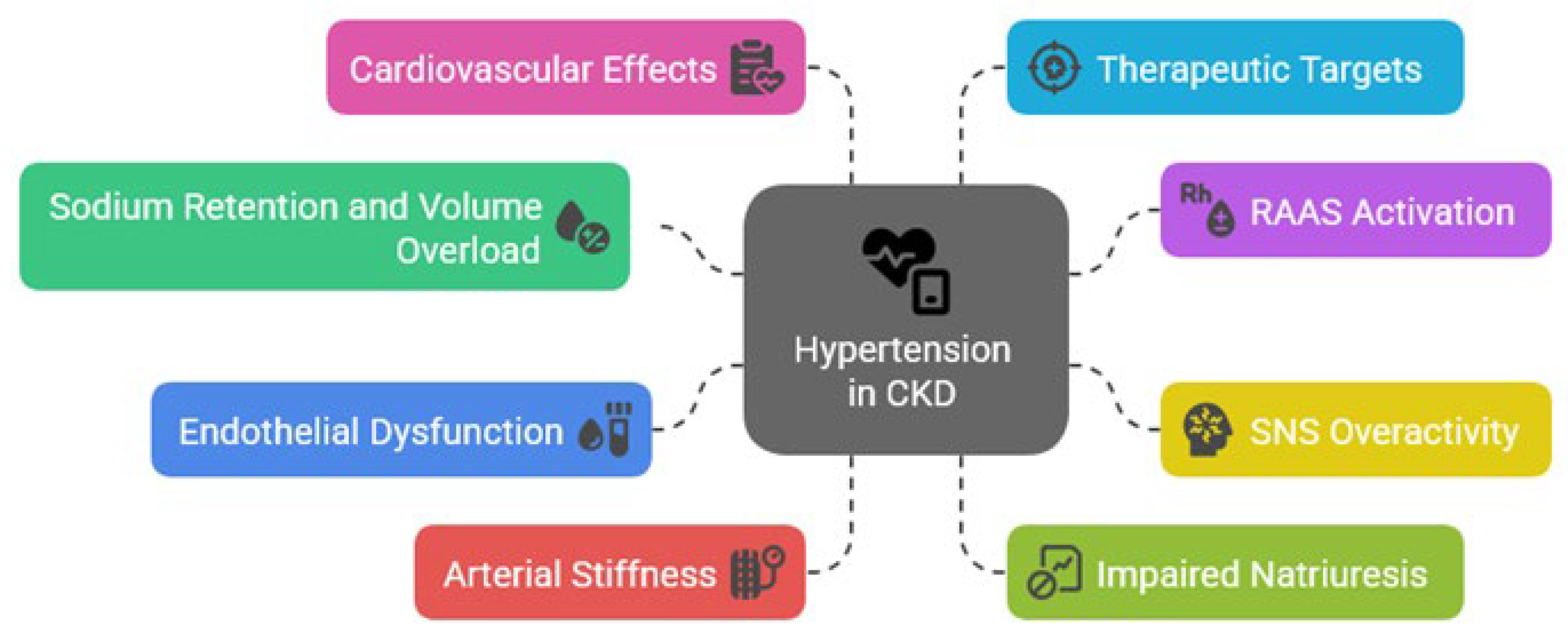

Hypertension in patients with CKD arises from a complex interplay of hemodynamic, neurohormonal, and structural abnormalities, with sodium and volume retention due to impaired renal excretory capacity proving as fundamental contributors (

Figure 1) [

16]. Reduced nephron mass leads to diminished natriuresis, promoting extracellular fluid expansion and increased cardiac output, thereby elevating SBP. This mechanism is particularly relevant in early to moderate stages of CKD, where fluid overload often goes unrecognized (

Table 1).

Figure 1.

Pathophysiologic mechanisms of hypertension in chronic kidney disease (CKD). RAAS=renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; SNS=sympathetic nervous system.

Figure 1.

Pathophysiologic mechanisms of hypertension in chronic kidney disease (CKD). RAAS=renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; SNS=sympathetic nervous system.

Table 1.

Pathophysiological mechanisms linking hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD). CV=cardiovascular; ESKD=end-stage kidney disease; LVH=left ventricular hypertrophy; NO=nitric oxide; RAAS=renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; RND=renal denervation.

Table 1.

Pathophysiological mechanisms linking hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD). CV=cardiovascular; ESKD=end-stage kidney disease; LVH=left ventricular hypertrophy; NO=nitric oxide; RAAS=renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; RND=renal denervation.

| Mechanism |

Description |

Real-World

Example |

Prevalence and

Impact on Hard Events |

Clinical Implication |

| Sodium and volume overload |

Impaired natriuresis → expansion of extracellular volume |

Overhydration in dialysis; interdialytic weight gain |

~80% in ESKD; associated with LVH, stroke, mortality |

Need for aggressive volume and salt control |

| RAAS activation |

Vasoconstriction and aldosterone-driven salt retention |

Proteinuric diabetic nephropathy |

Present in all CKD stages; linked to progression, CV mortality |

Justifies RAAS blockade |

| Sympathetic nervous system overdrive |

Afferent and efferent neural hyperactivity |

Elevated norepinephrine in ESKD patients |

↑ sympathetic tone in 100% ESKD; ↑ sudden cardiac death risk |

Targeted by RDN |

| Endothelial dysfunction |

Reduced NO bioavailability and oxidative stress |

Low flow-mediated dilation in CKD patients |

Found in ≥60% CKD; predictor of CV events |

Encourages statins, anti-inflammatories |

| Microcirculatory impairment |

Capillary rarefaction, hypoxia, impaired autoregulation |

Reduced capillary density in renal biopsies |

Subclinical; related to ischemic nephropathy, heart failure |

Limited therapeutic targeting yet emerging |

The activation of the RAAS plays a significant role in the hypertensive phenotype of CKD, with declining renal perfusion stimulating renin release, enhancing angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction and aldosterone-driven sodium reabsorption. [

17] Beyond volume effects, RAAS overactivation contributes to vascular remodeling, myocardial fibrosis, and progressive nephron injury, and thus pharmacologic inhibition of this axis remains a cornerstone in both BP control and renoprotection. [

18]

Sympathetic nervous system (SNS) overactivity is a hallmark of advanced renal insufficiency and correlates with both hypertension severity and cardiovascular risk. Afferent renal nerve signaling enhances central sympathetic output, exacerbating vasoconstriction, tachycardia, and renin release [

19]. This creates a vicious cycle of heightened neurohumoral activation, impaired baroreceptor sensitivity, and refractory hypertension, providing the background for the emerging therapeutic role of RDN, as it can specifically target this mechanism, underscoring its potential value in CKD [

20].

Finally, vascular dysfunction contributes significantly to sustained hypertension in renal disease, with endothelial injury, oxidative stress, and arterial stiffness impairing vasodilation and increasing systemic resistance [

21]. These processes are compounded by uremic toxins and inflammation, which accelerate arteriosclerosis. Microvascular rarefaction further limits tissue perfusion, perpetuating ischemic injury and hypertensive end-organ damage [

22].

4. Diagnostic Framework

Accurate diagnosis and classification of hypertension in patients with CKD are foundational to effective management as hypertension in this context may be categorized as controlled, uncontrolled, or resistant, the latter defined by persistently elevated BP despite the use of three or more antihypertensive agents, including a diuretic [

16]. Importantly, these classifications should be interpreted within the context of renal function stage and comorbid conditions. BP targets have been progressively lowered in recent guidelines, with recommendations for a SBP goal of <120 mmHg based on standardized office measurements in patients with CKD and elevated BP, though achieving this safely remains challenging in advanced stages of disease [

23].

Most importantly, BP measurement modality significantly impacts diagnosis as office BP readings, though widely used, often fail to capture true BP burden due to white-coat or masked hypertension [

24]. Conversely, ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) and home BP monitoring (HBPM) offer superior prognostic value, particularly in identifying nocturnal hypertension and non-dipping patterns, which are prevalent in CKD and associated with adverse outcomes [

25]. Accordingly, ABPM remains the gold standard for diagnosing resistant hypertension and should be utilized when available to confirm true resistance and guide therapy [

26].

Volume status assessment is another essential diagnostic component, particularly in dialysis-dependent patients where interdialytic weight gain and ultrafiltration rates influence BP variability [

27]. Clinical evaluation should include signs of volume overload, alongside laboratory markers (e.g., natriuretic peptides) and, where possible, bioimpedance analysis, accompanied by concurrent evaluation of target organ damage—such as left ventricular hypertrophy, albuminuria, or hypertensive retinopathy—supports risk stratification and treatment prioritization. Diagnostic clarity not only directs therapeutic intensity but also distinguishes between pharmacologic resistance and pseudo-resistance due to nonadherence or suboptimal measurement [

26].

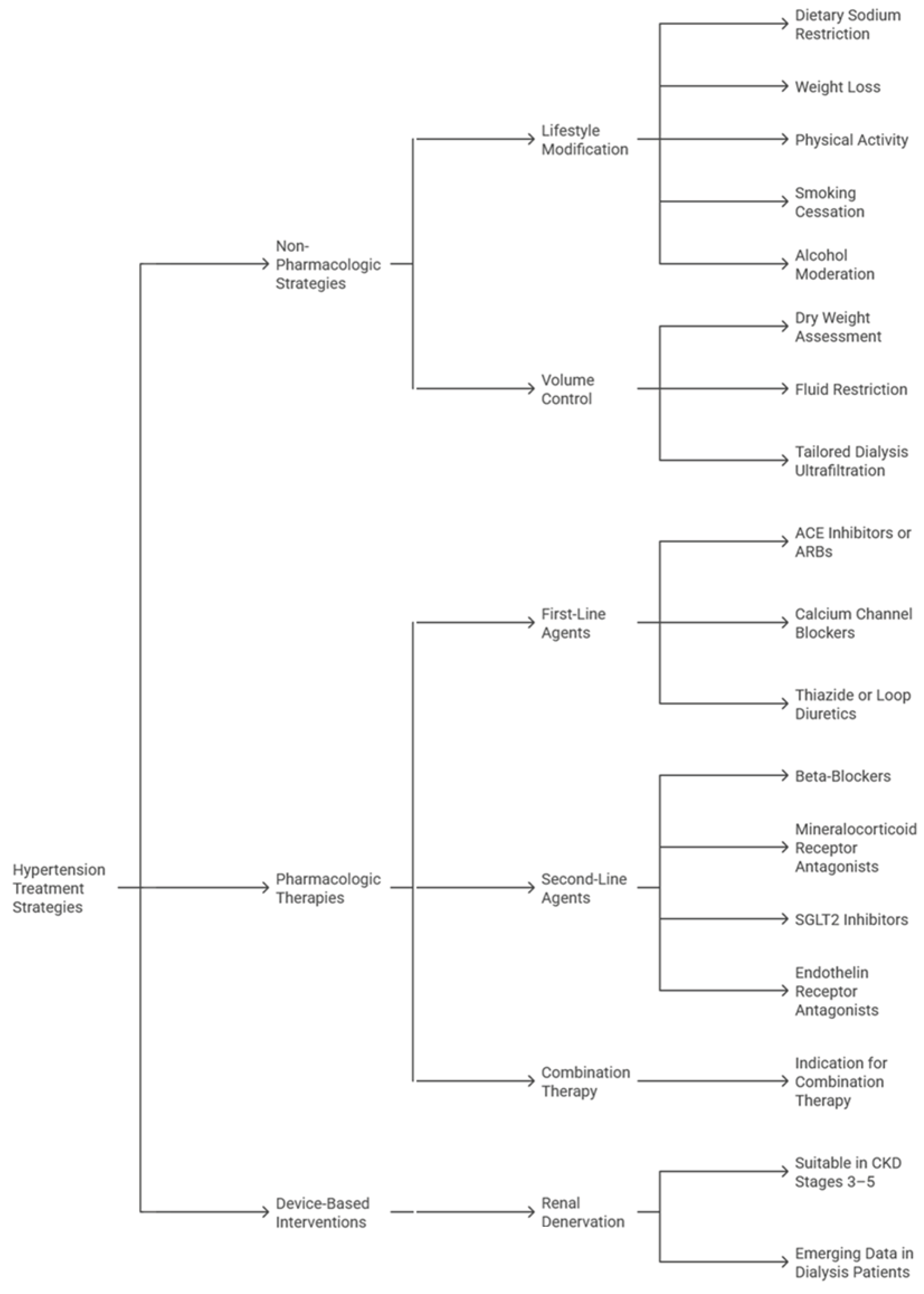

5. Therapeutic Strategies

Management of hypertension in patients with CKD demands a multifaceted approach that balances effective BP control with renal protection, with overarching goals including minimizing cardiovascular risk, slowing progression to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), and reducing treatment-related complications (

Figure 2) [

28]. Guidelines such as those from the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Collaborators and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Society of Hypertension (ESH) emphasize individualized therapy, recognizing the high prevalence of resistant hypertension in this population. Tailored interventions must account for volume status, residual kidney function, comorbidities, and medication tolerance [

23,

28].

Non-pharmacologic strategies remain foundational in CKD-related hypertension). Sodium restriction to less than 2.3 grams/day, moderation of fluid intake, weight control, and structured physical activity have demonstrable benefits in lowering BP and enhancing responsiveness to antihypertensive medications (

Table 2) [

29]. In dialysis patients, achieving and maintaining optimal dry weight through ultrafiltration is critical, while dietary counseling, particularly in potassium and phosphorus management, should align with the CKD stage. In addition, growing emphasis has been placed on patient education and behavioral interventions to improve long-term adherence [

30].

Table 2.

Therapeutic approaches for hypertension (HTN) in chronic kidney disease (CKD). ACE=angiotensin-converting-enzyme; ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker; BP=blood pressure; CAD=coronary artery disease; CCB=calcium channel blocker; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVH=left ventricular hypertrophy; MRA=mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; SGLT2= sodium-glucose cotransporter-2.

Table 2.

Therapeutic approaches for hypertension (HTN) in chronic kidney disease (CKD). ACE=angiotensin-converting-enzyme; ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker; BP=blood pressure; CAD=coronary artery disease; CCB=calcium channel blocker; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVH=left ventricular hypertrophy; MRA=mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; SGLT2= sodium-glucose cotransporter-2.

| Treatment |

Purported Benefits |

Ideal Candidate |

Possible Candidate |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs |

Reduce proteinuria, slow CKD progression, lower BP |

CKD with albuminuria, diabetes, hypertension |

Normoalbuminuric CKD with hypertension |

| Beta-blockers |

Reduce heart rate, LVH; useful in ischemia |

CKD with CAD or heart failure |

Advanced CKD with high sympathetic tone |

| Calcium Channel Blockers (CCBs) |

Effective BP control, salt-insensitive |

CKD with isolated systolic hypertension |

General CKD patients without albuminuria |

| Diuretics (Loop/Thiazide) |

Volume control, enhanced natriuresis |

Volume-expanded CKD stage 3–5, resistant hypertension |

Controlled HTN with borderline fluid status |

| MRAs (e.g., finerenone) |

Anti-fibrotic, further RAAS inhibition, proteinuria reduction |

Diabetic CKD with persistent albuminuria on ACEI/ARB |

Non-diabetic CKD with proteinuria |

| Renal Denervation |

Reduces sympathetic activity and BP, medication sparing |

Resistant HTN with eGFR >30, failed triple therapy |

ESKD on dialysis with refractory BP |

| SGLT2 inhibitors |

Cardioprotective, reduce albuminuria, mild BP reduction |

CKD stage 2–4 with diabetes or proteinuria |

Non-diabetic CKD with residual albuminuria |

Pharmacologic therapy should be individualized based on CKD stage, proteinuria, and cardiovascular risk (

Figure 3) [

23,

26]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are cornerstone therapies, particularly in proteinuric CKD, owing to their renoprotective and antiproteinuric effects. Diuretics, especially loop diuretics in advanced CKD, play a vital role in volume management. Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are effective in reducing systolic hypertension and it can safely combined with RAAS inhibitors [

31]. Beta-blockers may be considered, particularly in patients with concomitant coronary artery disease or arrhythmia Tomiyama H. In resistant hypertension, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) such as finerenone are increasingly usedalthough hyperkalemia risk requires close monitoring [

32].

Device-based approaches, particularly RDN, offer a compelling therapeutic adjunct for patients with resistant hypertension, a condition frequently observed in CKD [

33]. involves catheter-based ablation of sympathetic nerve fibers surrounding the renal arteries, thereby interrupting both efferent and afferent signaling pathways that contribute to hypertension and sympathetic overactivity [

4]. The pathophysiological basis is particularly relevant in CKD, where sympathetic hyperactivity is amplified and contributes to progressive renal function decline and heightened cardiovascular risk. A growing body of evidence, including observational studies and small-scale trials, has demonstrated that RDN can safely lower BP in patients with moderate-to-severe CKD, including dialysis-dependent individuals, without causing significant deterioration in renal function [

34,

35,

36].

While these benefits appear durable, with reductions in both office and 24-hour ambulatory SBP persisting over months, Patient selection remains paramount: ideal candidates are those with documented medication adherence, uncontrolled BP despite optimal pharmacologic therapy, and suitable vascular anatomy for catheter access [

37,

38]. Indeed, anatomical considerations, such as vascular calcification or altered renal artery structure, are particularly important in CKD patients [

39]. While RDN is currently used in select clinical contexts, ongoing randomized trials aim to refine patient eligibility criteria, evaluate long-term safety, and potentially expand its role in routine nephrology and hypertension care.

In summary, successful BP management in renal insufficiency requires integrating pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic therapies with emerging interventional modalities. As evidence accumulates, particularly for therapies like RDN, clinicians should remain agile in updating treatment algorithms. Multidisciplinary collaboration among nephrologists, cardiologists, dietitians, and primary care providers is essential for achieving optimal outcomes in this high-risk population. Precision in tailoring therapy not only controls BP but may also mitigate the accelerated progression of CKD and its cardiovascular sequelae.

6. Hypertension in Special Renal Populations

Hypertension is highly prevalent in patients undergoing dialysis, with up to 80% affected and it is notably It is multifactorial, driven by volume overload, sodium retention, arterial stiffness, and heightened sympathetic activity. [

33,

40] Volume control remains the cornerstone of management, yet excessive ultrafiltration can paradoxically induce intradialytic hypotension, and ambulatory and interdialytic BP monitoring are recommended for accurate assessment in dialysis patients [

27]. Recent studies also support cautious use of RAAS inhibitors and β-blockers, while newer therapies such as SGLT2 inhibitors are under investigation for adjunctive roles [

41].

Post-transplant hypertension occurs in most of recipients, and it is evidently influenced by immunosuppressive agents (especially calcineurin inhibitors), chronic allograft dysfunction, and residual native kidney function.

42] Management must balance cardiovascular protection with graft preservation, with RAAS blockade being frequently favored due to its antiproteinuric benefits, but requires monitoring for hyperkalemia and potential effects on graft perfusion. In addition, mTOR inhibitors, CCBs, and diuretics play variable roles based on the patient’s comorbidity profile and graft function [

43].

Older adults with CKD often exhibit isolated systolic hypertension and are at elevated risk of orthostatic hypotension and adverse drug events, thus BP targets are essential, considering frailty, fall risk, and cognitive impairment [

44]. Polypharmacy is common, requiring regular medication reviews, while non-pharmacological interventions such as dietary sodium restriction and supervised exercise programs are underutilized but essential in this group. Overall, it is clear that tailored, goal-directed management improves outcomes while minimizing treatment burden [

45].

7. Controversies and Misconceptions

Despite growing awareness of the impact hypertension in CKD, misconceptions continue to influence clinical decisions and impede optimal management, with a prevalent issue being the overreliance on office BP readings, which may not reflect true BP control due to white-coat or masked hypertension [

46]. Ambulatory or home BP monitoring offers superior prognostic value, especially in advanced CKD where BP variability and nocturnal hypertension are common, yet, unfortunately, these tools are underutilized in nephrology practice, contributing to misclassification and therapeutic inertia [

47].

A second enduring myth is the hesitancy to continue RAAS inhibitors in patients with declining eGFR [

48]. Although mild increases in serum creatinine are expected with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, these agents confer substantial renal and cardiovascular protection. Inappropriately discontinuing them out of fear of worsening kidney function may accelerate disease progression and expose patients to adverse outcomes. Guidelines recommend continuing RAAS blockade unless hyperkalemia or symptomatic hypotension mandates withdrawal KDIGO [

23].

Another common misconception pertains to dialysis-induced hypotension [

27]. Although some patients experience intradialytic BP drops, this should not preclude treatment of pre-dialysis hypertension, which is associated with increased mortality. Evidence suggests that volume overload, not dialysis per se, drives most hypertensive phenotypes in this population, accordingly individualized dry weight targets and dietary sodium restriction remain pivotal interventions.

Finally, therapeutic inertia—defined as failure to intensify treatment despite uncontrolled BP—remains a critical barrier [

49]. Clinicians may mistakenly attribute persistent hypertension to patient nonadherence alone, overlooking structural barriers and biologic resistance. Overcoming this inertia requires structured assessment tools, multidisciplinary input, and consideration of adjunctive strategies such as RDN in carefully selected patients [

50].

8. Conclusions

Recent advances in hypertension management increasingly emphasize individualized approaches supported by precision medicine and emerging technologies. Biomarker-guided therapy may soon allow clinicians to predict patient responsiveness to interventions such as RDN or novel antihypertensive agents, including SGLT2 inhibitors and aldosterone synthase blockers. Artificial intelligence (AI) and digital monitoring tools—particularly wearable devices—offer promising avenues for real-time BP tracking and adherence assessment [

51]. Meanwhile, upcoming clinical trials targeting patients with advanced CKD are expected to provide definitive evidence on the long-term efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of RDN, potentially reshaping therapeutical approaches for resistant hypertension in this population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.V., G.B.Z.; methodology, D.M.G., G.F., L.F.d.N., E.R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.V., G.B.Z., E.R.G.; writing—review and editing, D.M.G., G.F., L.F.d.N.; visualization, E.R.G.; supervision, F.V., G.B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was drafted and illustrated with the assistance of artificial intelligence tools, such as ChatGPT 5.1 (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA), and Napkin AI (Napkin AI, Palo Alto, CA, USA), in keeping with established best practices (Biondi-Zoccai G, editor. ChatGPT for Medical Research. Torino: Edizioni Minerva Medica; 2024). The final content, including all conclusions and opinions, has been thoroughly revised, edited, and approved by the authors. The authors take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the work and retain full credit for all intellectual contributions. Compliance with ethical standards and guidelines for the use of artificial intelligence in research has been ensured.

Conflicts of Interest

Giuseppe Biondi-Zoccai has consulted, lectured and/or served as advisory board member and/or expert witness for Abiomed, Advanced Nanotherapies, Amarin, AstraZeneca, Balmed, Cardionovum, Cepton, Crannmedical, Endocore Lab, Eukon, Guidotti, Innova HTS, Innovheart, Menarini, Microport, Opsens Medical, Otsuka Medical Devices Europe, Recor, Servier, Synthesa, Terumo, and Translumina, outside the present work. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABPM |

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring |

| ACEi |

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor |

| ARB |

Angiotensin receptor blocker |

| BP |

Blood pressure |

| CCB |

Calcium channel blocker |

| CKD |

Chronic kidney disease |

| eGFR |

Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| ESH |

European Society of Hypertension |

| ESC |

European Society of Cardiology |

| HBPM |

Home blood pressure monitoring |

| KDIGO |

Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes |

| MRA |

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist |

| RAAS |

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system |

| RDN |

Renal denervation |

| SBP |

Systolic blood pressure |

| SGLT2 |

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 |

| SNS |

Sympathetic nervous system |

References

- Hamrahian, S.M.; Falkner, B. Hypertension in Chronic Kidney Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017, 956, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ku, E.; Lee, B.J.; Wei, J.; Weir, M.R. Hypertension in CKD: Core curriculum 2019. Am J Kidney Dis 2019, 74, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.H.; Yang, W.; Townsend, R.R.; Pan, Q.; Chertow, G.M.; Kusek, J.W.; Charleston, J.; He, J.; Kallem, R.; Lash, J.P.; et al. Time-updated systolic blood pressure and the progression of chronic kidney disease: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015, 162, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnier, M.; Damianaki, A. Hypertension as Cardiovascular Risk Factor in Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ Res 2023, 132, 1050–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntounousi, E.; D’Arrigo, G.; Gori, M.; Bruno, G.; Mallamaci, F.; Tripepi, G.; Zoccali, C. The bidirectional link between left ventricular hypertrophy and chronic kidney disease. A cross lagged analysis. J Hypertens 2025, 43, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veglio, F.; Mulatero, P. Resistant or refractory hypertension: It is not just the of number of drugs. J Hypertens 2021, 39, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntner, P.; Anderson, A.; Charleston, J.; Chen, Z.; Ford, V.; Makos, G.; O’Connor, A.; Perumal, K.; Rahman, M.; Steigerwalt, S.; et al. Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Investigators. Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in adults with CKD: Results from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2010, 55, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, S. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone pathway modulators in chronic kidney disease: A comparative review. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1101068. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeanu, E.M.; Morisot, E.; Bronner, F.; Prinz, E.; Stephan, D. From resistant hypertension to renal denervation: An emerging therapeutic approach in light of new international guidelines. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev 2025, 27, 200550. [Google Scholar]

- Versaci, F.; Sciarretta, S.; Scappaticci, M.; Calcagno, S.; Di Pietro, R.; Sbandi, F.; Dei Giudici, A.; Del Prete, A.; De Angelis, S.; Biondi-Zoccai, G. Renal arteries denervation with second generation systems: A remedy for resistant hypertension? Eur Heart J Suppl 2020, 22, L160–L165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderoju, Y.B.G.; Hayford, F.E.A.; Achempim-Ansong, G.; Duah, E.; Baloyi, T.V.; Morerwa, S.; Agordoh, P.; Dzansi, G. Exploring the application of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) in the management of patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2025, 69, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftab, R.A.; Sellappans, R.; Ming, C.K.; Shaik, I. Taking a Step Further in Identifying Ideal Blood Pressure Range Among Hemodialysis Patients: A Systematic Review and a Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Khan, A.H.; Adnan, A.S.; Syed Sulaiman, S.A.; Gan, S.H.; Khan, I. Management of Patient Care in Hemodialysis While Focusing on Cardiovascular Disease Events and the Atypical Role of Hyper- and/or Hypotension: A Systematic Review. Biomed Res Int 2016, 2016, 9710965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Qushayri, A.E.; Khalaf, K.M.; Dahy, A.; Mahmoud, A.R.; Benmelouka, A.Y.; Ghozy, S.; Mahmoud, M.U.; Bin-Jumah, M.; Alkahtani, S.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Fournier’s gangrene mortality: A 17-year systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2020, 92, 218–225. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani, R.; Noel, E.; Boyle, S.; Balina, H.; Ali, S.; Fayoda, B.; Khan, W.A. Role of Antihypertensives in End-Stage Renal Disease: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e27058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgianos, P.I.; Agarwal, R. Hypertension in chronic kidney disease: Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation notable 2017 advances. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2019, 34, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bader, M. Tissue renin-angiotensin-aldosterone systems: Targets for pharmacological therapy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2010, 50, 439–465. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlonka, J.; Buchalska, B.; Buczma, K.; Borzuta, H.; Kamińska, K.; Cudnoch-Jędrzejewska, A. Targeting the Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone System (RAAS) for Cardiovascular Protection and Enhanced Oncological Outcomes: Review. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2024, 25, 1406–1427. [Google Scholar]

- Varghese, T.P.; Tazneem, B. Unraveling the complex pathophysiology of heart failure: Insights into the role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Curr Probl Cardiol 2024, 49, 102411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolu-Akinnawo, O.; Ray, D.N.; Awosanya, T.; Nzerue, C.; Okafor, H. Hypertension and Device-Based Therapies for Resistant Hypertension: An Up-to-Date Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e66304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, A.; Mazzapicchi, A.; Baiardo Redaelli, M. Systemic and Cardiac Microvascular Dysfunction in Hypertension. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 13294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nowak, K.L.; Jovanovich, A.; Farmer-Bailey, H.; Bispham, N.; Struemph, T.; Malaczewski, M.; Wang, W.; Chonchol, M. Vascular Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney360 2020, 1, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group. KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int 2021, 99, S1–S87. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, B.B.; Anderson, M.L.; Cook, A.J.; Ehrlich, K.; Hall, Y.N.; Hsu, C.; Joseph, D.; Klasnja, P.; Margolis, K.L.; McClure, J.B.; et al. Clinic, Home, and Kiosk Blood Pressure Measurements for Diagnosing Hypertension: A Randomized Diagnostic Study. J Gen Intern Med 2022, 37, 2948–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, S.; Garofalo, C.; Gabbai, F.B.; Chiodini, P.; Signoriello, S.; Paoletti, E.; Ravera, M.; Bussalino, E.; Bellizzi, V.; Liberti, M.E.; et al. Dipping Status, Ambulatory Blood Pressure Control, Cardiovascular Disease, and Kidney Disease Progression: A Multicenter Cohort Study of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2023, 81, 15–24.e1. [Google Scholar]

- Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R.; Brunström, M.; Burnier, M.; Grassi, G.; Januszewicz, A.; Muiesan, M.L.; Tsioufis, K.; Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Algharably, E.A.E.; et al. ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J Hypertens 2023, 41, 1874–2071. [Google Scholar]

- Flythe, J.E.; Chang, T.I.; Gallagher, M.P.; Lindley, E.; Madero, M.; Sarafidis, P.A.; Unruh, M.L.; Wang, A.Y.; Weiner, D.E.; Cheung, M.; et al. Blood pressure and volume management in dialysis: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2020, 97, 861–876. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, D.; Hishida, E. Elucidating the complex interplay between chronic kidney disease and hypertension. Hypertens Res 2024, 47, 3409–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, E.J.; Campbell, K.L.; Bauer, J.D.; Mudge, D.W. Altered dietary salt intake for people with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021, 6, CD010070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, E.P.; Rosario, V.D.; Probst, Y.; Beck, E.; Tran, T.B.; Lambert, K. Lifestyle Interventions, Kidney Disease Progression, and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Kidney Med 2023, 5, 100643. [Google Scholar]

- Ino, S.; Ishii, A.; Yanagita, M.; Yokoi, H. Calcium channel blocker in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol 2022, 26, 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bakris, G.L.; Agarwal, R.; Anker, S.D.; Pitt, B.; Ruilope, L.M.; Rossing, P.; Kolkhof, P.; Nowack, C.; Schloemer, P.; Joseph, A.; et al. Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 2219–2229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scalise, F.; Quarti-Trevano, F.; Toscano, E.; Sorropago, A.; Vanoli, J.; Grassi, G. Renal Denervation in End-Stage Renal Disease: Current Evidence and Perspectives. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Prev 2024, 31, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Scalise, F.; Sole, A.; Singh, G.; Sorropago, A.; Sorropago, G.; Ballabeni, C.; Maccario, M.; Vettoretti, S.; Grassi, G.; Mancia, G. Renal denervation in patients with end-stage renal disease and resistant hypertension on long-term haemodialysis. J Hypertens 2020, 38, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ott, C.; Mahfoud, F.; Mancia, G.; Narkiewicz, K.; Ruilope, L.M.; Fahy, M.; Schlaich, M.P.; Böhm, M.; Schmieder, R.E. Renal denervation in patients with versus without chronic kidney disease: Results from the Global SYMPLICITY Registry with follow-up data of 3 years. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2022, 37, 304–310. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Yin, X.M.; Li, Z.Q.; He, Q.; Sun, X.Q.; Xia, D.C.; Kong, D.L.; Lu, C.Z. Ultra-long-term follow-up of renal denervation in patients with resistant hypertension and mild chronic kidney disease. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 2025, 53, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Mahfoud, F.; Böhm, M.; Schmieder, R.; Narkiewicz, K.; Ewen, S.; Ruilope, L.; Schlaich, M.; Williams, B.; Fahy, M.; Mancia, G. Effects of renal denervation on kidney function and long-term outcomes: 3-year follow-up from the Global SYMPLICITY Registry. Eur Heart J 2019, 40, 3474–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Phillips, J.K. Patient Selection for Renal Denervation in Hypertensive Patients: What Makes a Good Candidate? Vasc Health Risk Manag 2022, 18, 375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, P.; DeRiso, A.; Patel, M.; Battepati, D.; Khatib-Shahidi, B.; Sharma, H.; Gupta, R.; Malhotra, D.; Dworkin, L.; Haller, S.; et al. Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease: Diversity in the Vessel Wall. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, N.; Artinian, N.T.; Bakris, G.; Chang, T.; Cohen, J.; Flythe, J.; Lea, J.; Vongpatanasin, W.; Chertow, G.M.; American Heart Association Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; et al. Hypertension in Patients Treated With In-Center Maintenance Hemodialysis: Current Evidence and Future Opportunities: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2023, 80, e112–e122. [Google Scholar]

- Tomson, C.R.V.; Cheung, A.K.; Mann, J.F.E.; Chang, T.I.; Cushman, W.C.; Furth, S.L.; Hou, F.F.; Knoll, G.A.; Muntner, P.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; et al. Management of Blood Pressure in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease Not Receiving Dialysis: Synopsis of the 2021 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med 2021, 174, 1270–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opelz, G.; Döhler, B. Collaborative Transplant Study. Improved long-term outcomes after renal transplantation associated with blood pressure control. Am J Transplant 2005, 5, 2725–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, M.R.; Burgess, E.D.; Cooper, J.E.; Fenves, A.Z.; Goldsmith, D.; McKay, D.; Mehrotra, A.; Mitsnefes, M.M.; Sica, D.A.; Taler, S.J. Assessment and management of hypertension in transplant patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015, 26, 1248–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.W. Blood Pressure Control in Elderly Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Electrolyte Blood Press 2022, 20, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Hwang, W.M. Management of Elderly Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Yonsei Med J 2025, 66, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, A.G. Clinical Value of Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2023, 81, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, N.; Missick, S.; Haley, W. Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring: Profiles in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients and Utility in Management. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2019, 26, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakris, G.L.; Weir, M.R. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated elevations in serum creatinine: Is this a cause for concern? Arch Intern Med 2000, 160, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunton, S.A. Therapeutic Inertia: Still a Big Problem. Clin Diabetes 2024, 42, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlowitz, D.R.; Ash, A.S.; Hickey, E.C.; Friedman, R.H.; Glickman, M.; Kader, B.; Moskowitz, M.A. Inadequate management of blood pressure in a hypertensive population. N Engl J Med 1998, 339, 1957–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi-Zoccai, G.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Giordano, S.; Mirzoyev, U.; Erol, Ç.; Cenciarelli, S.; Leone, P.; Versaci, F. Artificial Intelligence in Cardiology: General Perspectives and Focus on Interventional Cardiology. Anatol J Cardiol 2025, 29, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |