Submitted:

30 December 2025

Posted:

30 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

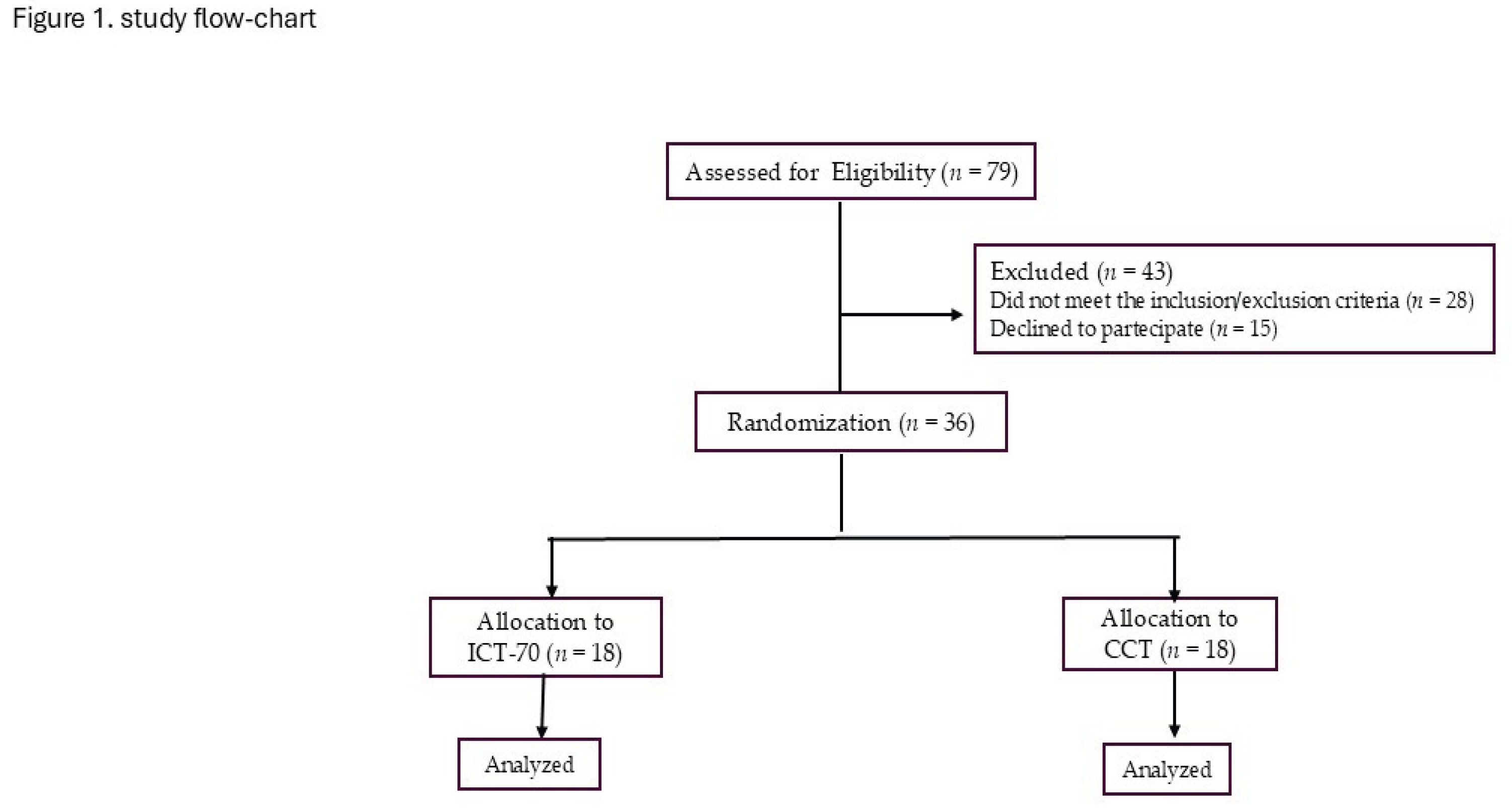

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Outcomes Measure

2.3.1. Resting Blood Pressure

2.3.2. Exercise Capacity

2.3.3. 24–h Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring

2.3.4. Exercise Sessions

2.3.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPV | Blood pressure variability |

| IHD | Ischemic heart disease |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| CCT | Continuous combined training |

| ICT | Interval combined training |

| MICT | Moderate intensity continuous training |

| HIIT | High-intensity interval training |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| ECG | Electrocardiography |

| CPET | Cardiopulmonary exercise testing |

| 6MWT | Six-minute walk test |

| ABPM | Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring |

| ARV | Average real variability |

| HR | Heart rate |

| 1-RM | One-repetition maximum |

| BMI | Body mass index |

References

- Wu, X.; Sha, J.; Yin, Q.; et al. Global burden of hypertensive heart disease and attributable risk factors, 1990–2021: insights from the global burden of disease study 2021. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 14594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forouzanfar, M.H.; Liu, P.; Roth, G.A.; Ng, M.; Biryukov, S.; Marczak, L.; et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mmHg, 1990–2015. JAMA 2017, 317, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z.F.; Han, J.M.; Jin, X.; Dong, Z.F.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Ye, T.B.; Yang, B.S.; Zhang, Y.P.; Shen, C.X. Patients with comorbid coronary artery disease and hypertension: a cross-sectional study with data from the NHANES. Ann Transl Med. 2022, 10, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, T.; Lang, I.; Zweiker, R.; Horn, S.; Wenzel, R.R.; Watschinger, B.; Slany, J.; Eber, B.; Roithinger, F.X.; Metzler, B. Hypertension and coronary artery disease: epidemiology, physiology, effects of treatment, and recommendations: A joint scientific statement from the Austrian Society of Cardiology and the Austrian Society of Hypertension. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2016, 128, 467–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, J.; Liang, J.; Zhuang, X.; et al. Intensive blood pressure treatment in coronary artery disease: implications from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT). J Hum Hypertens 2022, 36, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; Chieffo, A.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Deaton, C.; Doenst, T.; Jones, H.W.; Kunadian, V.; Mehilli, J.; Milojevic, M.; Piek, J.J.; Pugliese, F.; Rubboli, A.; Semb, A.G.; Senior, R.; Ten Berg, J.M.; Van Belle, E.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.M.; Vidal-Perez, R.; Winther, S.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. Erratum in: Eur Heart J. 2025, 46, 1565. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaf079. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parati, G.; Pomidossi, G.; Albini, F.; Malaspina, D.; Mancia, G. Relationship of 24-h blood pressure mean and variability to severity of target-organ damage in hypertension. J Hypertens 1987, 5, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Song, C.; Ouyang, F.; Ma, T.; He, L.; Fang, F.; Zhang, G.; Huang, J.; Bai, Y. Systolic blood pressure variability: risk of cardiovascular events, chronic kidney disease, dementia, and death. Eur Heart J. 2025, 46, 2673–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladini, F.; Fania, C.; Mos, L.; Vriz, O.; Mazzer, A.; Spinella, P.; Garavelli, G.; Ermolao, A.; Rattazzi, M.; Palatini, P. Short-Term but not Long-Term Blood Pressure Variability Is a Predictor of Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Young Untreated Hypertensives. Am J Hypertens. 2020, 33, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palatini, P.; Saladini, F.; Mos, L.; Fania, C.; Mazzer, A.; Cozzio, S.; Zanata, G.; Garavelli, G.; Biasion, T.; Spinella, P.; Vriz, O.; Casiglia, E.; Reboldi, G. Short-term blood pressure variability outweighs average 24-h blood pressure in the prediction of cardiovascular events in hypertension of the young. J Hypertens. 2019, 37, 1419–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, S.; Parati, G.; Bangalore, S.; Bilo, G.; Kim, B.J.; Kario, K.; Messerli, F.; Stergiou, G.; Wang, J.; Whiteley, W.; Wilkinson, I.; Sever, P.S. Blood pressure variability: a review. J Hypertens. 2025, 43, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.G.; Yan, P.; Jeffers, B.W. Effects of amlodipine and other classes of antihypertensive drugs on long-term blood pressure variability: evidence from randomized controlled trials. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014, 8, 340–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toba, A. Effect of exercise and physical activity on blood pressure reduction. Hypertens Res 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEvoy, J.W.; McCarthy, C.P.; Bruno, R.M.; Brouwers, S.; Canavan, M.D.; Ceconi, C.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Daskalopoulou, S.S.; Ferro, C.J.; Gerdts, E.; Hanssen, H.; Harris, J.; Lauder, L.; McManus, R.J.; Molloy, G.J.; Rahimi, K.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Rossi, G.P.; Sandset, E.C.; Scheenaerts, B.; Staessen, J.A.; Uchmanowicz, I.; Volterrani, M.; Touyz, R.M.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2024, 45, 3912–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelliccia, A.; Sharma, S.; Gati, S.; Bäck, M.; Börjesson, M.; Caselli, S.; Collet, J.P.; Corrado, D.; Drezner, J.A.; Halle, M.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 17–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Koning, I.A.; Heutinck, J.M.; Vromen, T.; Bakker, E.A.; Maessen, M.F.H.; Smolders, J.; Eijsvogels, T.M.H.; Grutters, J.P.C.; van Geuns, R.-J.M.; Kemps, H.M.C.; et al. Cardiac rehabilitation vs. percutaneous coronary intervention for stable angina pectoris: A retrospective study of effects on major adverse cardiovascular events and associated healthcare costs. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2024, 31, 1987–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosetti, M.; Abreu, A.; Corrà, U.; Davos, C.H.; Hansen, D.; Frederix, I.; et al. Secondary prevention through comprehensive cardiovascular rehabilitation: from knowledge to implementation. 2020 update. A position paper from the secondary prevention and rehabilitation section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2021, 28, 460–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibben, G.O.; Faulkner, J.; Oldridge, N.; Rees, K.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2023, 44, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambic, T.; Šarabon, N.; Lainscak, M.; Hadžić, V. Combined resistance training with aerobic training improves physical performance in patients with coronary artery disease: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 9, 909385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminiti, G.; Mancuso, A.; Raposo, A.F.; Fossati, C.; Selli, S.; Volterrani, M. Different exercise modalities exert opposite acute effects on short-term blood pressure variability in male patients with hypertension. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019, 26, 1028–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminiti, G.; Iellamo, F.; Mancuso, A.; Cerrito, A.; Montano, M.; Manzi, V.; Volterrani, M. Effects of 12 weeks of aerobic versus combined aerobic plus resistance exercise training on short-term blood pressure variability in patients with hypertension. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2021, 130, 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, X.; Jiao, H.; Li, Y.; Pan, G.; Yitao, X. The Effect of High-Intensity Interval Training on Exercise Capacity in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiol Res Pract. 2023, 2023, 7630594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, X.; Shen, F.; Xu, N.; Li, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Effects of high-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training on blood pressure in patients with hypertension: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e32246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Vera, L.; Ulloa-Díaz, D.; Araya-Sierralta, S.; Guede-Rojas, F.; Andrades-Ramírez, O.; Carvajal-Parodi, C.; Muñoz-Bustos, G.; Matamala-Aguilera, M.; Martínez-García, D. Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training on Blood Pressure Levels in Hypertensive Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Life (Basel) 2024, 14, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A. PAFS consensus group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammin, E.J. The 6-Minute Walk Test: Indications and Guidelines for Use in Outpatient Practices. J Nurse Pract. 2022, 18, 608–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mena, L.; Pintos, S.; Queipo, N.V.; Aizpurua, J.A.; Maestre, G.; Sulbaran, T. A reliable index for the prognostic significance of blood pressure variability. J Hypertens 2005, 23, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flight, L.; Julious, S.A. Practical guide to sample size calculations: An introduction. Pharm. Stat. 2016, 15, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M; Lin, Y; Li, Y; Lin, X. Effect of exercise training on blood pressure variability in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0292020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.; Mesquita-Bastos, J.; Garcia, C.; Leitão, C.; Ribau, V.; Teixeira, M.; Bertoquini, S.; Ribeiro, I.P.; de Melo, J.B.; Oliveira, J.; et al. Aerobic exercise improves central blood pressure and blood pressure variability among patients with resistant hypertension: Results of the EnRicH trial. Hypertens. Res. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Hypertens. 2023, 46, 1547–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Z.; Tran, J.; Lam, A.; Yiu, K.; Tsoi, K. Aerobic, Resistance, and Isometric Exercise to Reduce Blood Pressure Variability: A Network Meta-Analysis of 15 Clinical Trials. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2025, 27, e70050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zercher, S.; Muth, B.; Stock, J.; Edwards, D.G. The Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training and Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training in Sedentary Individuals on Blood Pressure Reactivity. Physiology 2025, 40, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MartinezAguirre-Betolaza, A.; Mujika, I.; Fryer, S.M.; Corres, P.; Gorostegi-Anduaga, I.; Arratibel-Imaz, I.; Pérez-Asenjo, J.; Maldonado-Martín, S. Effects of different aerobic exercise programs on cardiac autonomic modulation and hemodynamics in hypertension: data from EXERDIET-HTA randomized trial. J Hum Hypertens. 2020, 34, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Neto, M.; Durães, A.R.; Conceição, L.S.R.; Silva, C.M.; Martinez, B.P.; Carvalho, V.O. High-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training on exercise capacity and health-related quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Phys Ther. 2025, 29, 101137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannan, A.L.; Hing, W.; Simas, V.; et al. High-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training within cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access J Sports Med. 2018, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ICT (n=18) | CTT (n=18) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 66.1±11.2 | 65.4±12.7 | 0.682 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.3±6.8 | 29.1±8.0 | 0.473 |

| Males, n (%) | 17 (94.4) | 16 (88.8) | 0.457 |

| Previous STEMI/NSTEMI-UA, n (%) | 13 (72.2)/ 5 (27.7) | 14 (77.7) / 4 (22.2) | 0.542 |

| Previous CABG/PCI, n (%) | 10 (55.5) / 14 (77.7) | 11 (61.1) / 14 (77.7) | 0.846 |

| Multivessel disease, n (%) | 13 (72.2) | 15 (83.3) | 0.439 |

| Carotid artery disease, n (%) | 9 (50.0) | 10 (55.5) | 0.598 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4 (22.2) | 5 (27.7) | 0.362 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 16 (88.8) | 17 (94.4) | 0.248 |

| Previous/active smoker, n (%) | 13 (72.2) / 3 (16.6) | 11( 61.1) / 2 (11.1) | 0.623 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 74.8±10.3 | 72.5±13.6 | 0.528 |

| LVEF, % | 54.2±7.2 | 53.8±8.2 | 0.344 |

| E/e’ ratio | 7.2±2.2 | 7.8±1.6 | 0.597 |

| Treatment | |||

| ACE-i/ARBs, n (%) | 18 (100.0) | 18 (100.0) | 0.784 |

| Betablockers, n (%) | 18 (100.0) | 18 (100.0) | 0.572 |

| MRAs, n (%) | 5 (27.7) | 4 (22.2) | 0.211 |

| Thiazide diuretic, n (%) | 9 (50.0) | 11 ( 61.1) | 0.668 |

| Ivabradine, n (%) | 2 (11.1) | 3 (16.6) | 0.395 |

| Statins, n (%) | 18 (100.0) | 18 (100.0) | 0.714 |

| CCAs, n (%) | 10 (55.5) | 11 (61.1) | 0.848 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 16 (88.8) | 16 (88.8) | 0.652 |

| Clopidogrel, | 3 (16.6) | 2 (11.1) | 0.283 |

| GLT-2 |

| ICT | CCT | Adjusted between-group p | |||

| Baseline | 12-weeks | Baseline | 12-weeks | ||

| CPET | |||||

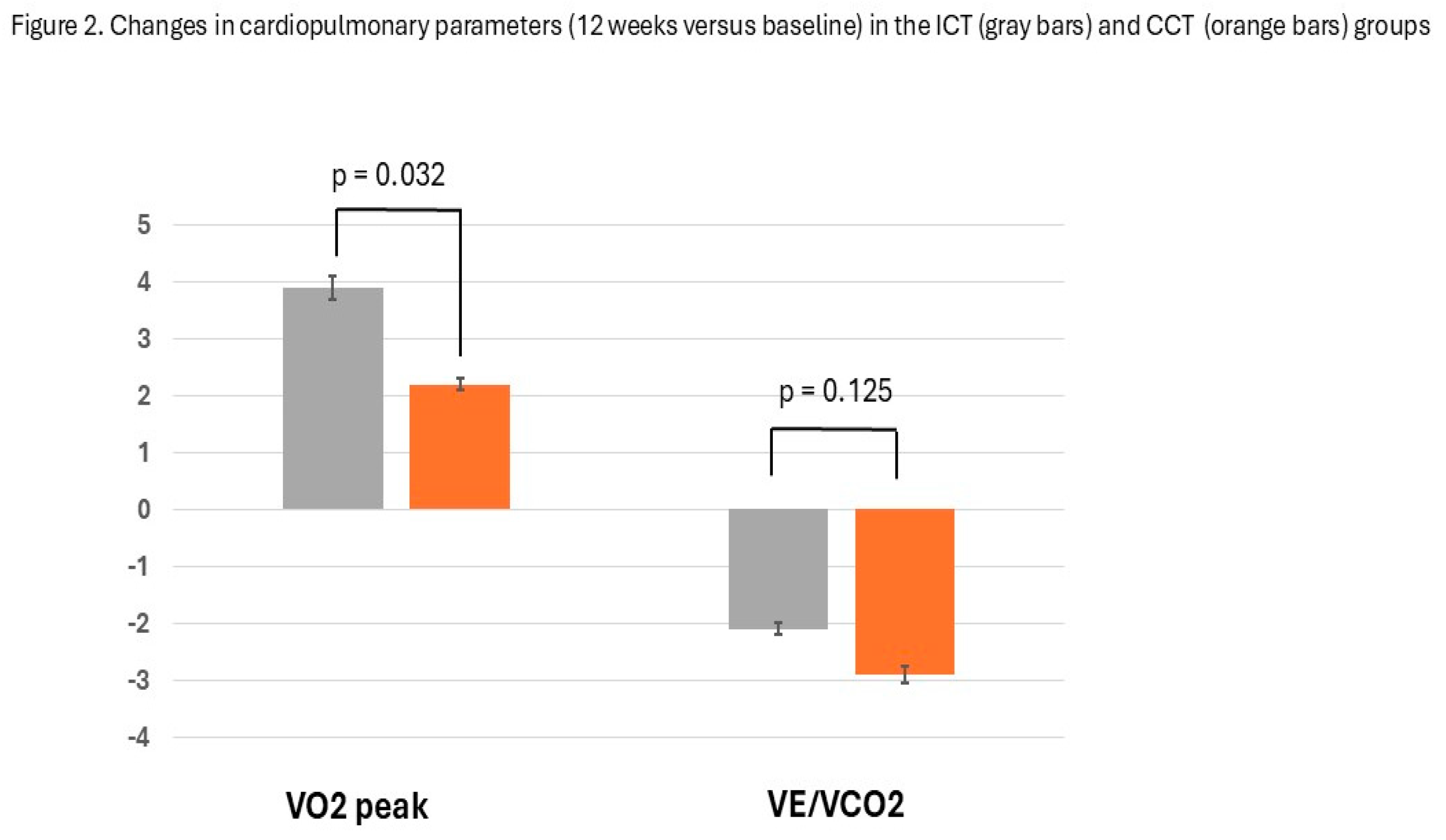

| VO2, ml/ kg/min | 25.5±3.9 | 29.4±3,6 | 24.9±4.3 | 27.1±38 | 0.032 |

| VE/VCO2 | 31.3±6.9 | 29.2±7.8 | 32.4±8.1 | 29.5±6.4 | 0.095 |

| Exercise time, sec | 498±66.2 | 567.3±73.1 | 512.6±78.8 | 581.2±84.1 | 0.368 |

| 6MWT distance, m | 351.7±88.4 | 426.3±92.1 | 349.4±84.8 | 413.3± 98.2 | 0.185 |

| SBP at rest , mmHg | 116.5±12.7 | 112.1±7.9 | 117.2±10.3 | 114.6±8.4 | 0.174 |

| DBP at rest, mmHg | 78.1 ± 6.8 | 75.7±7.6 | 77.7 ± 6.8 | 77.3 ± 5.4 | 0.511 |

| 24/h BP monitoring, mmHg | |||||

| BP averages | |||||

| 24/h SBP | 117.6±6.6 | 117.4±8.1 | 119.1±10.8 | 118.2±9.6 | 0.476 |

| Daytime SBP | 119±17.4 | 121.1±16.9 | 121.9±22.3 | 120.4±18.4 | 0.251 |

| Nighttime SBP | 111.5±13.2 | 112.1±16.8 | 112.7±13.5 | 112.1±15.0 | 0.063 |

| 24/h DBP | 76.6±4.4 | 75.1±5.7 | 72.9±6.9 | 72.8±8.0 | 0.683 |

| Daytime DBP | 78.2±8.4 | 77.8±9.1 | 75.3±6.6 | 75.4±9-4 | 0.372 |

| Nighttime DBP | 69.0±5.7 | 68.3±8.8 | 66.7±7.3 | 67.0±8.7 | 0.239 |

| BP variabiliy | |||||

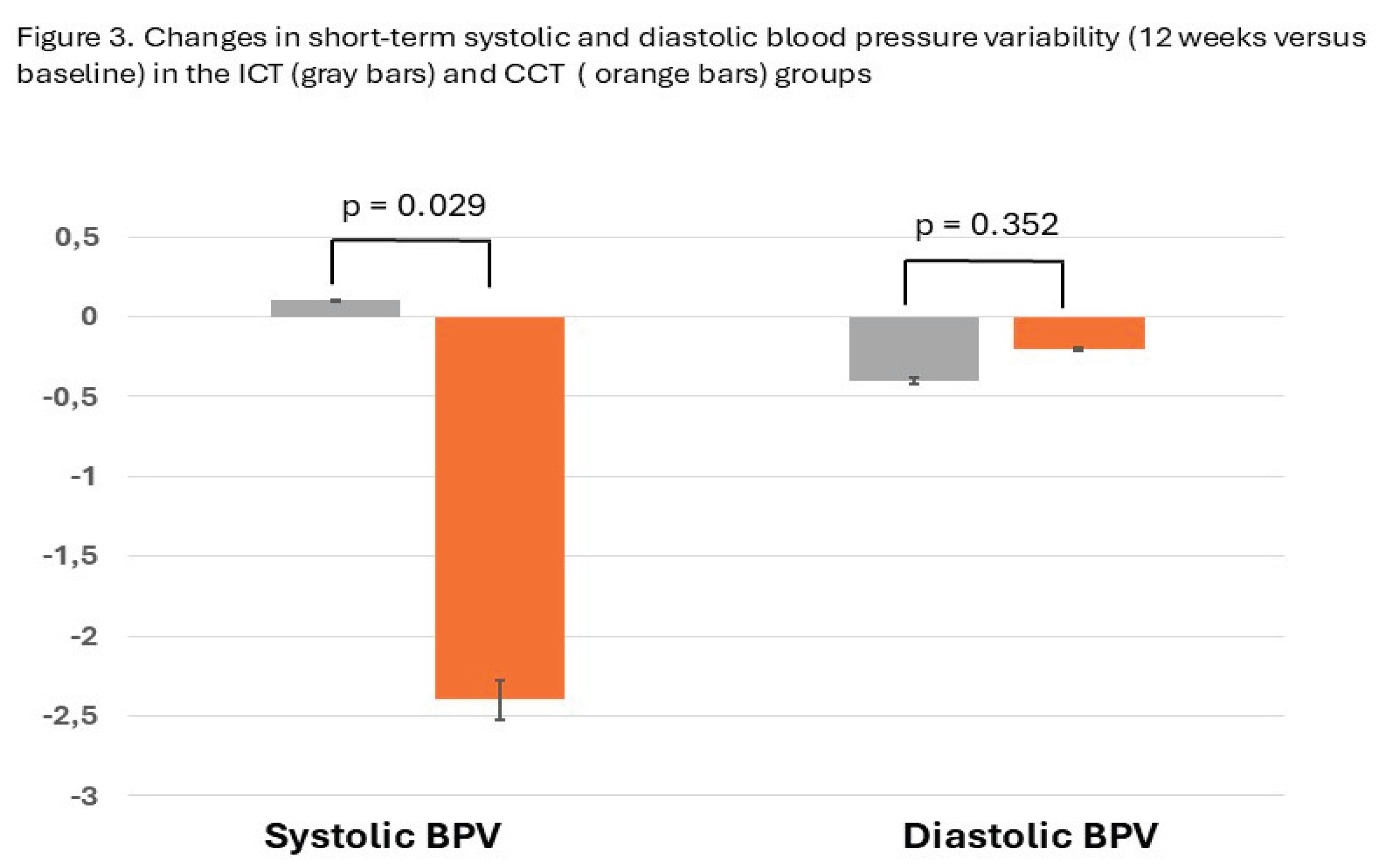

| PAS – AVR | 9.4±2.1 | 9.5±2.7 | 10.7 ±2.6 | 8.3±1.8* | 0.029 |

| PAD- AVR | 7.6±1.4 | 7.2±1.0 | 8.1±2.6 | 7.9±2.8 | 0.352 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).