1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, between 200,000 and 500,000 new cases of traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) are registered on a global scale each year [

1]. However, contemporary methods of treating spinal injuries have been criticized for not restoring lost functions of the central nervous system adequately [

2,

3]. Consequently, the quest for efficacious treatment methodologies that can effectively mitigate the ramifications of SCI has emerged as a pivotal domain of interest within the realm of neurology. One such method is electrical stimulation of the spinal cord, which has been demonstrated to activate spinal neural networks that are known as locomotor pattern generators [

4]. These, in turn, can initiate walking movements in humans [

5,

6]. However, the locomotor pattern induced by spinal cord stimulation does not usually provide full locomotor function. In fact, it is only a trigger for initiating locomotion. For example, in a horizontal or vertical body position, spinal cord stimulation at thoracolumbar level causes rhythmic movements of the lower limbs, mainly in the hip joint, with predominant activation of the proximal leg muscles [

7].

It is assumed that sensory-motor integration is required for successful locomotor behavior: descending commands, activity of spinal locomotor neural networks, and afferent input from the limbs. Therefore, in the neurorehabilitation of patients with motor disorders of various origins, combined electrical stimulation of the spinal cord and locomotor training are used [

8]. The achievement of this technology is the demonstration of independent overground walking by spinal individuals under conditions of spinal cord stimulation and the use of external support (cane, walker) to control balance [

9,

10]. At the same time, it was noted that when spinal individuals walk under electrical stimulation in the area of localization of neural locomotor networks, the muscles of the lower leg are not sufficiently activated, which does not allow them to push the body forward in the stance phase and perform dorsiflexion of the foot in swing phase. To some extent, this deficiency was overcome by using non-invasive multimodal spinal cord stimulation, combining continuous stimulation of the neural locomotor networks and targeted stimulation of the posterior roots that activate the flexor/extensor motor pools of the leg in certain phases of the gait cycle [

11].

With this stimulation, we observed quite effective propulsion of the body in the stance phase and dorsiflexion of the foot in the swing phase in healthy volunteer subjects. However, in spinal individuals, this effect was not as pronounced, apparently due to structural and functional changes in the muscles [

12,

13].

The aim of this study is to investigate the effectiveness of regulating the stance and swing phases by transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the posterior roots, leg muscles, and their combined effects while walking of healthy volunteers on treadmill belt.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

The Materials and Methods This study was approved by the Pavlov Institute of Physiology Ethics Committee (Minutes № 25-01, dated 25 February 2025). All participants provided written informed consent. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sixteen healthy participants (13 males and 3 females, aged 19-35) participated in the study. The subjects performed walking movements on an Ortorent treadmill (Moscow, Russia) at a speed of 2 km/h.

2.2. Protocol

The study consisted of eight consecutive conditions: walking without stimulation and walking with transcutaneous spatial-temporal stimulation applied to the spinal posterior roots and shin muscles of the right leg. The first conditions were walking without stimulation (

Table 1).

L2: right spinal cord roots at L2 vertebrae level; HAM: right hamstring muscles; MG: right m. gastrocnemius; T12: right spinal cord roots at T12 vertebrae level; TA: right m. tibialis anterior. The duration of each condition was 20-30 seconds.

2.3. Transcutaneous Spinal-Muscular Stimulation

To stimulate the spinal posterior roots, electrodes were placed on the skin at the level of the T12 and L2 vertebrae. Round electrodes (cathodes) made of adhesive conductive rubber (ø 2.5 cm; ValuTrode® Axelgaard Manufacturing Co., Fallbrook, CA, USA) were placed laterally ~1.5-2 cm from the midline of the spine (

Figure 1). One common anode + (rectangular electrode 5*10 cm2; ValuTrode® Axelgaard Manufacturing Co., Fallbrook, CA, USA) was placed on the skin above the right iliac crest.

For stimulation of right tibialis anterior muscle (m. tibialis ant.), the electrode (cathode) (ø3.2 cm; ValuTrode® Axelgaard Manufacturing Co., Fallbrook, CA, USA) was placed in the broad part of the muscle, below the lateral condyle of the tibia, and the anode (rectangular electrode 5*10 cm2; ValuTrode® Axelgaard Manufacturing Co., Fallbrook, CA, USA) was placed in the lower third of the m.tibialis ant, above the transition of the muscle into the tendon (

Figure 1).

To stimulate the gastrocnemius muscle (MG), the electrode (cathode) was placed in the upper part of the muscle, between the medial and lateral heads of the muscle, and the anode in the lower part of the muscle. For stimulation the hamstring muscles (HAM), the electrode (cathode) was placed on the upper back of the thigh, under the gluteal fold, and the anode was placed distally in the middle of the back of the thigh. The electrodes 5 x 10 cm² (ValuTrode® Axelgaard Manufacturing Co., Fallbrook, CA, USA) were used.

Transcutaneous spinal-muscle stimulation was performed using monopolar pulses with frequency of 30 Hz at the T12 level and a frequency of 15 Hz at the L2 level. The pulses of 1 ms duration were filled with a carrier frequency of 5 kHz. The muscles of the lower extremities were stimulated with frequency of 35 Hz, pulses of 0,3 ms duration which were filled with a carrier frequency of 5 kHz).

A Neuroprosthesis-NP stimulator (Cosyma LLC, Moscow, Russia) was used for spinal-muscle stimulation. The stimulation intensity was selected individually for each person in a sitting position. The intensity for posterior roots stimulation was at the level of paresthesia but did not cause discomfort. The current strength for muscle stimulation was selected to cause a pronounced muscle contraction without causing discomfort.

An algorithm developed for controlling spinal cord posterior roots stimulation, described in detail in [

11] was used. Sensors combining a gyroscope and an accelerometer were used to determine the phases of the step cycle. The sensor was placed on the front surface of the thigh above the knee joint of the participant right leg. During walking, the angle of the sensor's measuring axis with the vertical in the sagittal plane was analyzed. The moment of leg lift was determined as the beginning of the swing phase. This event corresponds to the beginning of hip flexion.

Gait cycle is considered to be the moment when the foot is placed on the treadmill belt (heel strike) to the next same contact with the same leg [

14].

During stance phase the stimulation of the L2 roots was performed from 0% to 55%, HAM from 0% to 30%, MG from 25% to 55% of the current step cycle. During swing phase the stimulation of the posterior roots at T12 (vertebral level) and TA muscle was performed from 57% to 98% of the current step cycle [

15] (

Figure 1c).

2.4. Recording of Kinematic Characteristics of Walking

Marker coordinates at a sampling rate of 100 Hz were recorded using a 10-camera (optoelectronic) Oqus 500 system (Qualisys, Gothenburg, Sweden). Markers with a diameter of 19 mm were used. Calibration errors were <0.5 mm for a working space volume of approximately 4×2×2.5 m

3 [

16]. Reflective markers placed at the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, greater trochanter, lateral epicondyle of the femur, lateral malleolus, heel and hallux were used to reconstruct the kinematics of stepping movements. Movements were reconstructed in Qualisys Track Manager (Qualisys, Gothenburg, Sweden). A marker model was used to assess the biomechanics of the lower extremities [

17].

2.5. Data Analysis

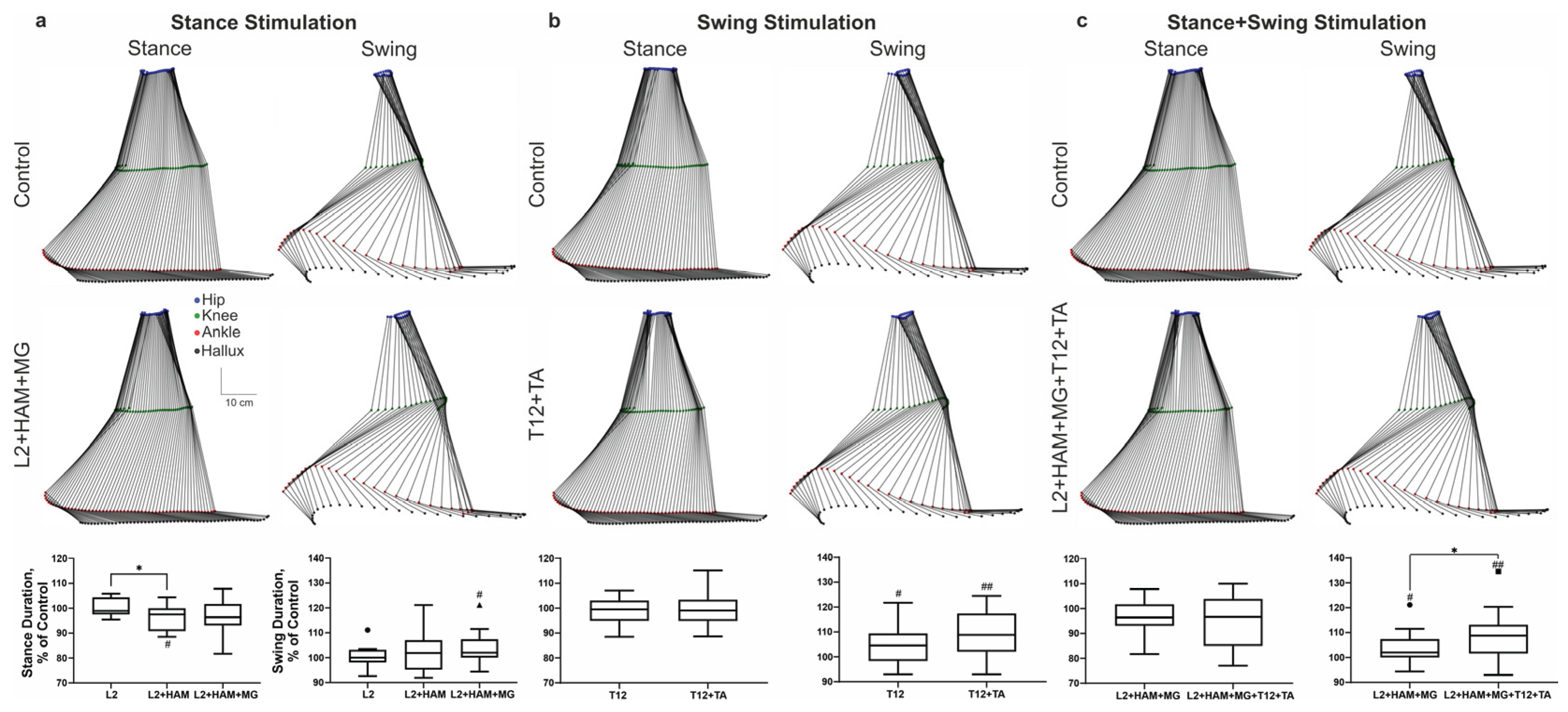

The obtained data with marker coordinates were exported to TSV files and processed using an original program developed in Python. The original program was used to calculate more than 80 spatio-temporal and kinematic parameters of walking. In addition, markers were used to visualize the trajectories of the hip, knee, ankle, heel, and big toe within the gait cycle. The original program was used to construct stick diagrams for the phases of the right leg step (

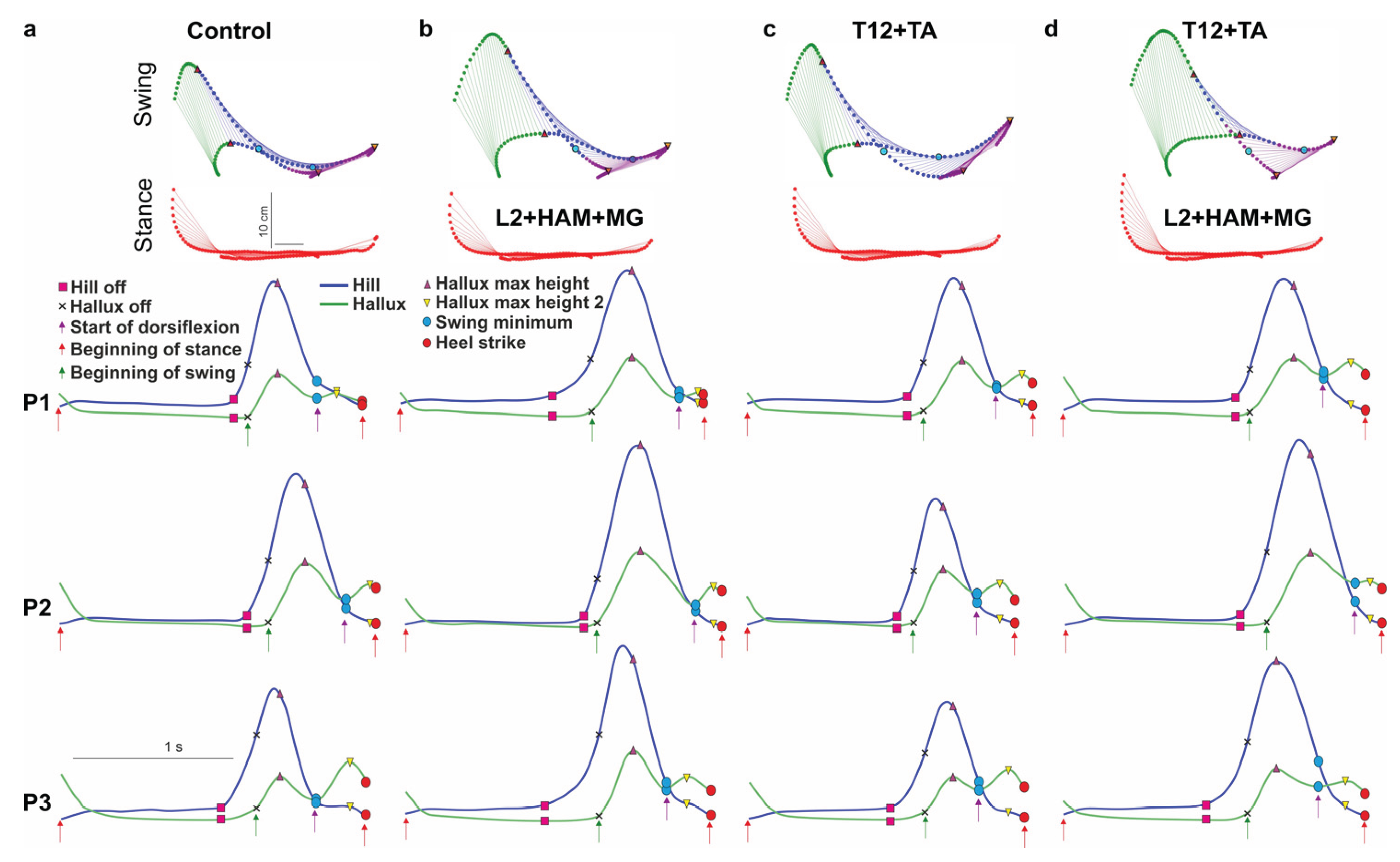

Figure 2).

The values obtained for the parameters of five gait cycles recorded under various stimulation conditions were averaged and normalized to the parameters of five gait cycles recorded without stimulation (control) while walking on a treadmill at each stage of the study (

Table 1). The obtained sets of values were checked for normality using the D'Agostino-Pearson criterion. To identify significant differences at the 0.05 level of sets of values from 100%, we used Student's t-test or Wilcoxon's t-test. To compare sets of values with each other, we used Student's paired t-test or Wilcoxon's paired t-test (one-way analysis of variance with repeated measurements with Tukey's correction for multiple comparisons or Friedman's criterion when comparing more than two sets) for normally and non-normally distributed sets of values, respectively. The analysis was performed using Prism 9.0 statistical data processing software (GraphPadSoftware, La Jolla, CA, USA). Movement parameters are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Stimulation of the Posterior Root L2 and Extensor Leg Muscles During the Stance Phase

Figure 2 shows the stick diagrams of reconstructed gait movements when walking on a treadmill belt with spinal and muscular stimulation applied in different phases of the gait cycle. Spinal cord stimulation of the posterior root (L2) during the stance phase had no significant effect on the duration of the phase, whereas combined stimulation of the posterior root L2 and muscle stimulation (HAM) significantly shortened the duration of the stance phase - 4% (p <0.05) relative to L2 stimulation. L2+HAM+MG stimulation led to a decrease in the stance phase duration as a tendency. At the same time, such stimulation significantly increased the subsequent unstimulated swing phase by +4% (p <0.05) (

Figure 2a

).

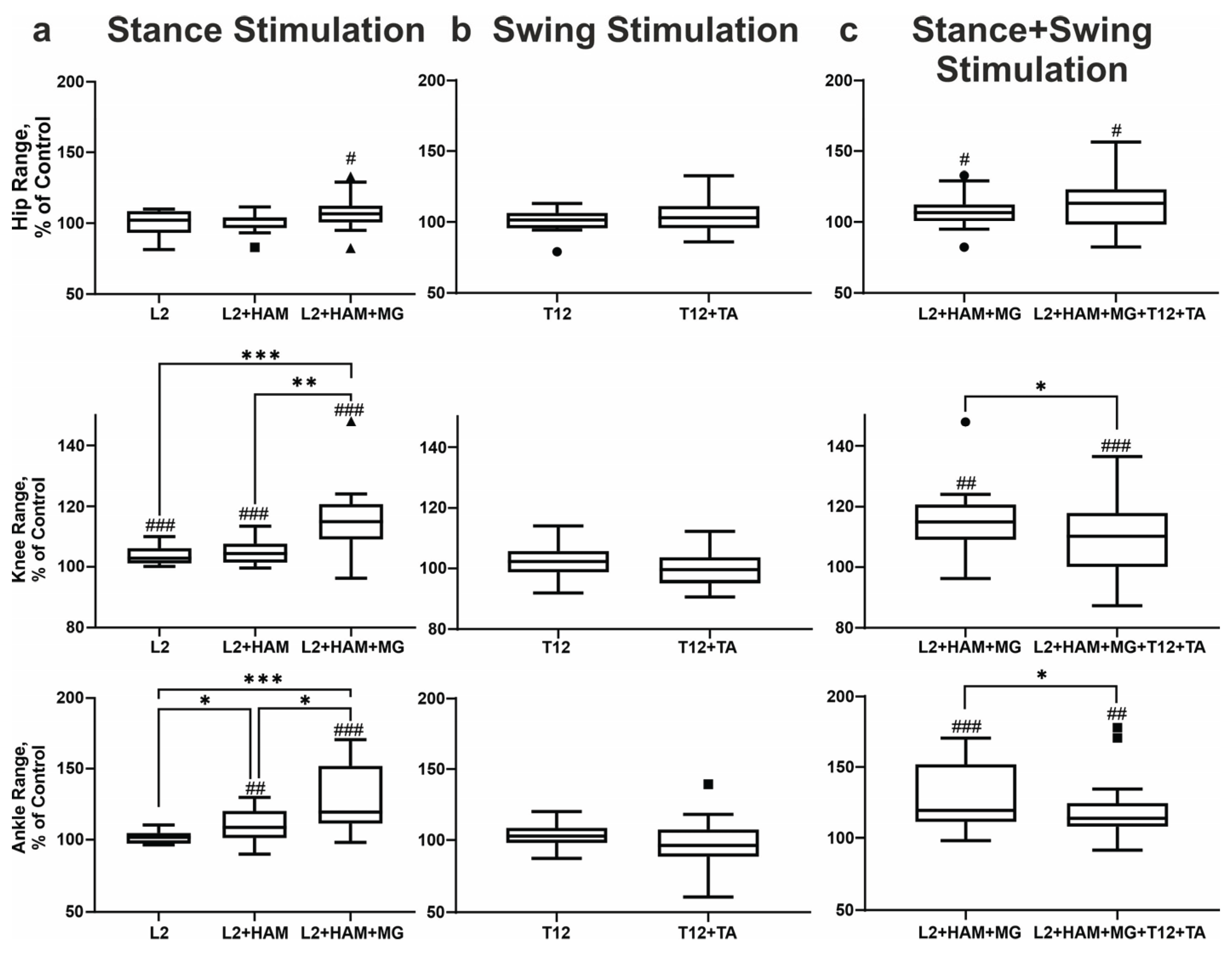

When L2 was stimulated during the stance phase, the amplitude of movement in the hip and ankle joints remained unchanged, while in the knee joint the amplitude increased by +4% (p < 0.001). The application of L2+HAM stimulation resulted in no alteration in the range of motion of the hip joint. In the knee joint the range of motion increased by +5% (p < 0.001), and in the ankle joint by +10% (p < 0.01). The application of combined L2+HAM+MG stimulation resulted in a significant augmentation in the amplitude of movement in the hip, knee, and ankle joints by 8% (p < 0.05), 16% (p < 0.001), and 29% (p < 0.001), respectively (

Figure 3a). At the same time, during L2+HAM+MG stimulation the length of the hip joint movement trajectory shortened by -6% (p < 0.01), the knee joint shortened by 8%, (p < 0.01), and the ankle joint shortened by - 4%. The application of L2+HAM+MG stimulation during stance, in the subsequent unstimulated swing phase, the length of the hip joint movement trajectory increased by +13% (p < 0.01), the knee joint by +20% (p < 0.0001), and the ankle joint by +3% (p < 0.05) (

Figure 3a).

Stimulation L2, L2+HAM and L2+HAM+MG during stance phase increased the height of the ankle lift by +9% (p<0.05), +20% (p <0 .001) and +35% (p < 0.001), respectively. Conversely, stimulation of L2+HAM+MG during the stance phase did not change the trajectory lengths of the heel or big toe during the swing phase, but increased the heel trajectory length by +6% (p < 0.001) and the big toe trajectory length by +4% (p < 0.01). Thus, activation of the extensor motor neuron pools (L2 stimulation) in combination with activation of the extensor muscles (HAM+MG) during stance phase shortened the duration of the phase, shortened the trajectories of the hip, knee and ankle joints, and caused the leg to rise above the treadmill belt and perform an intense swing of the limb.

3.2. Stimulation of the T12 Posterior Root and Leg Flexor Muscles During the Swing Phase

During the swing phase, stimulation of the T12 posterior roots and combined spinal-muscle stimulation (T12+TA) increased the duration of the swing phase by + 4% (p < 0.05) and +9% (p < 0.01), respectively (see

Figure 2b). Meanwhile, the subsequent unstimulated stance phase remained unchanged.

T12 and T12+TA stimulation did not change the amplitude of movements in the hip, knee and ankle joints (

Figure 3b). With T12+TA stimulation during swing the length of the hip joint movement trajectory increased by +13% (p < 0.01). The knee joint trajectory increased by +8% (p < 0.001) and the ankle joint trajectory by +3% (not significant).

When T12+TA was stimulated during swing phase, the height of the ankle lift increased by +5% (p < 0.05). The length of the heel movement trajectory increased by +4% (p < 0.05), while the length of the hallux movement trajectory increased by +3% (not significant). In the unstimulated stance phase, the length of the heel and hallux movement trajectories did not change.

T12+TA stimulation in the swing phase led to a change in the difference between the first and second peaks of hallux lift. In the control group, the first peak was 16 mm higher than the second one, but with stimulation, this indicator decreased to 6 mm. The change in this indicator characterizes an increase in the height of the maximum rise of the second peak by +80% (p < 0.001).

Thus, T12+TA stimulation in the swing phase led to a lengthening of the swing phase, an increase in the length of the trajectory in the hip, knee, and ankle joints, and an increase in the lift and swing of the leg above the treadmill belt, associated with an increase in foot dorsiflexion.

3.3. Combined Stimulation of the Posterior Roots of L2 and the Extensor Muscles of the Legs in the Stance Phase and the Posterior Roots of T12 and the Flexor Muscles of the Legs in the Swing Phase

With this stimulation, the duration of the stance phase remained unchanged, while the duration of the swing phase increased by +10% (p < 0.001) (see

Figure 2c). The amplitude of hip joint movements did not change in the stance phase but decreased in the swing phase by -1% (p < 0.05). Movement amplitude in the knee joint decreased by -1% (p < 0.05) in the stance phase and by -5% (p < 0.0001) in the swing phase. The amplitude of plantar flexion in the ankle joint increased by +1% (p < 0.05), while the amplitude of dorsiflexion in the ankle joint did not change.

The length of the hip joint trajectory decreased insignificantly by -4% in the stance phase, but increased by +15% (p < 0.05) in the swing phase. The knee joint trajectory decreased by -2% in the stance phase and increased by +18% (p < 0.0001) in the swing phase. The length of the ankle joint trajectory decreased by -5% in the stance phase (p < 0.05) and increased by +2% in the swing phase.

With combined stimulation, the height of the ankle lift increased significantly by +35% (p < 0.001). The length of the heel movement trajectory did not change in the stance phase, but increased by +7% (p < 0.01) in the swing phase. The length of the hallux movement trajectories in the stance and swing phases remained unchanged. Thus, combined stimulation of L2+HAM+MG during the stance phase, followed by stimulation of T12+TA during the swing phase, did not change the duration of the stance phase but increased the swing phase. Combined stimulation led to slight changes in amplitude at the hip, knee and ankle joints, increased leg lift above the treadmill belt and decreased angular displacement at the hip and ankle joints during the stance phase, while increasing angular displacement at the knee and ankle joints during the swing phase.

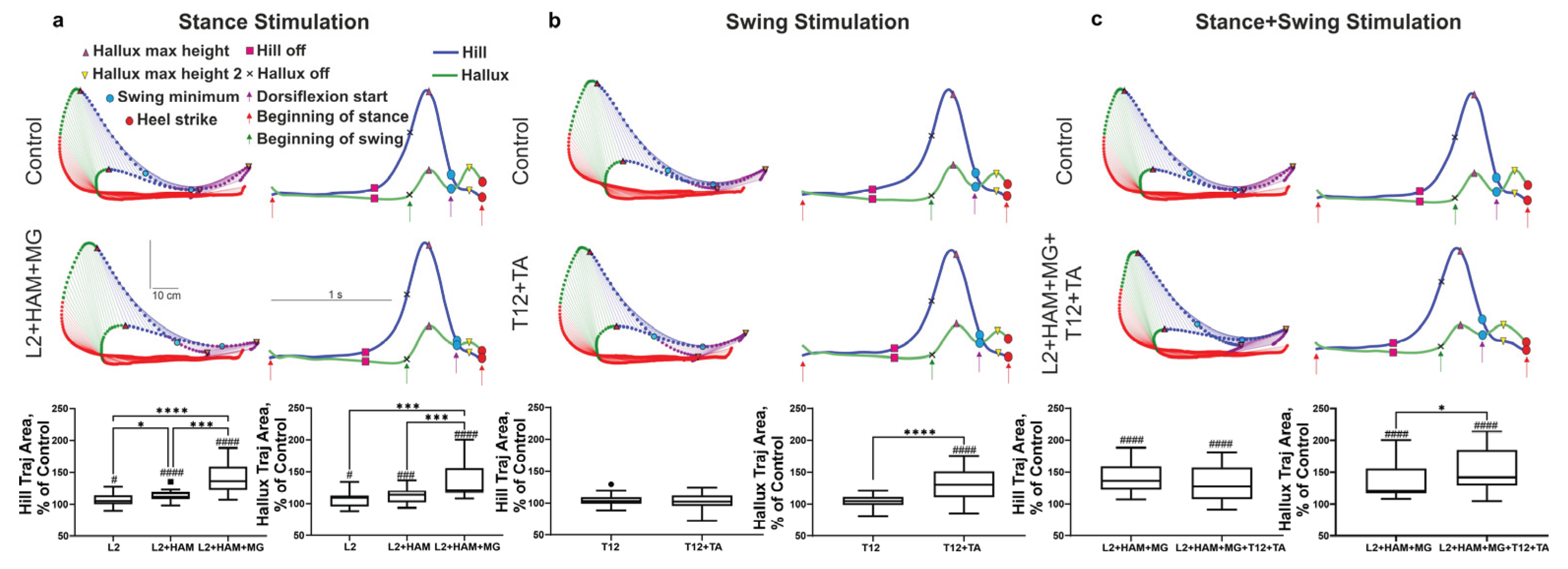

3.4. Characteristics of Foot Movement During Spinal-Muscular Stimulation

Figure 4 shows a stick diagrams of the reconstruction of heel and hallux movement during spinal-muscular stimulation. On the stick diagrams, the stance phase is highlighted in red, the beginning of the swing phase (initial swing) is highlighted in green (lift), and the heel/toe drop (mid swing) is highlighted in blue, and the second lift (start dorsiflexion/terminal swing) is highlighted in purple. On this figure the trajectories of the heel (blue line) and hallux (green line) in the gait cycle, indicating the start of lift (heel/hallux) (heel of), foot lift-off (start of the swing phase), and limb landing (heel strike) is presented. Kinematic analysis shows that, after positioning the limb on the treadmill belt, the heel and hallux remain on the belt for a period of time. At the end of the stance phase, the heel begins to rise while the hallux still touches the belt. Once the heel reaches a certain height, it and the hallux simultaneously lift above the treadmill belt. At this moment, the swing phase begins. The difference in behavior between the heel and hallux is that the heel goes through three stages in the stance phase—contact with the treadmill belt, lifting off above the belt, and heel lift—while the hallux goes through two stages: contact with the belt and lifting above it (

Figure 4a).

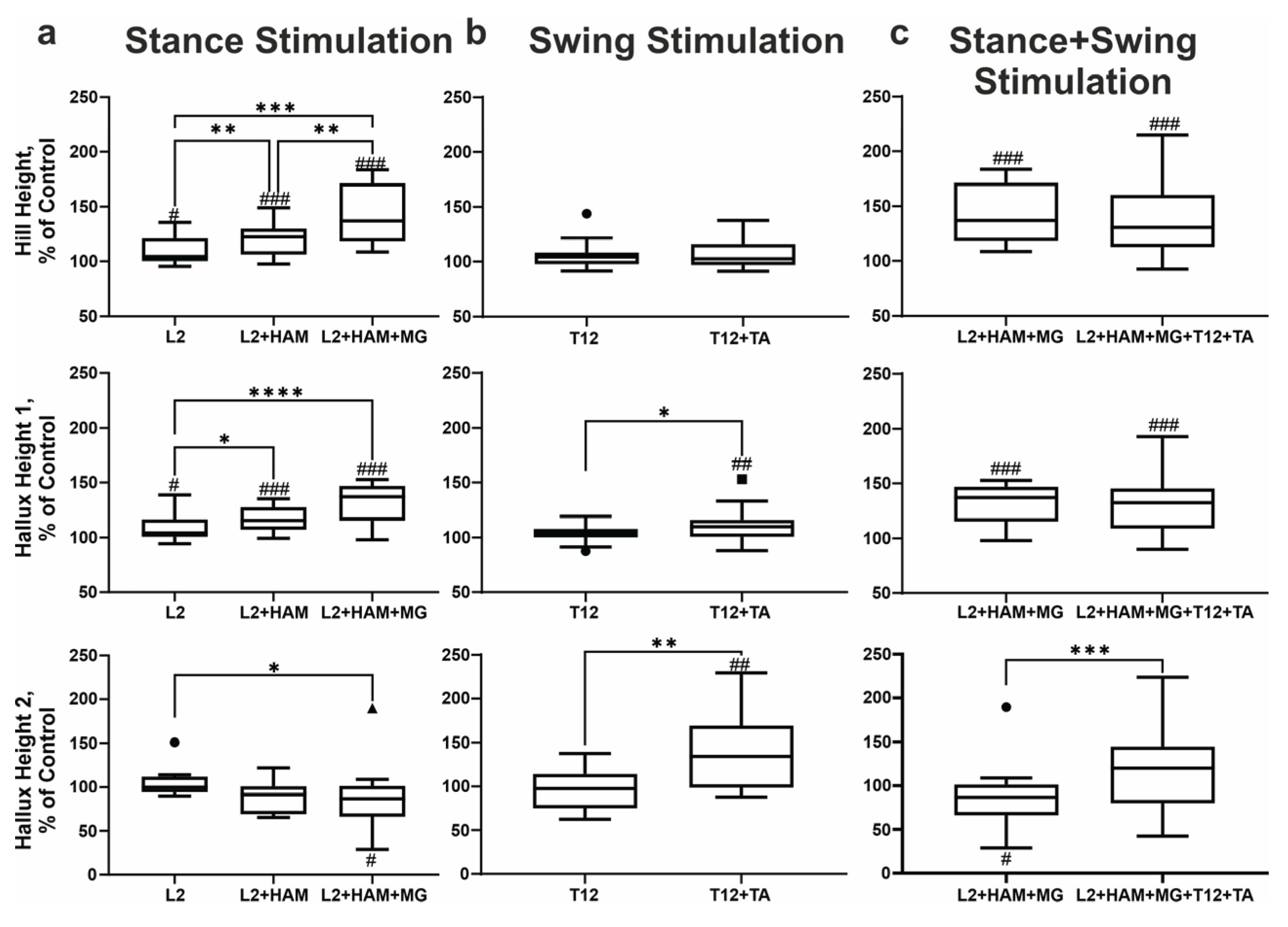

When L2 was stimulated during the stance phase, the integrals of heel and hallux movement within the gait cycle increased by +7% (p < 0.05) and +8% (p < 0.05), respectively. Stimulating L2+HAM increased the integral of heel movement by +14% (p < 0.0001) and the integral of hallux movement by +13% (p < 0.001). With L2+HAM+MG stimulation, these values increased by +39% (p < 0.0001) and +39% (p < 0.0001), respectively (

Figure 4a). With L2 and L2+HAM+MG stimulation during the stance phase, the height of the ankle lift increased by +9% (p < 0.05) and +35% (p < 0.001), respectively.

According to kinematic data, the heel lift in the stance phase does not change during spinal-muscular stimulation (

Figure 4a (red indication)), and the effect of stimulation appeared in the subsequent swing phase. Stimulation in the stance phase raises the heel above the treadmill belt (swing) significantly higher than in the control. Thus, with L2+HAM+MG stimulation in the stance phase, the maximum heel lift above the treadmill belt increased by +35% (p< 0.001) relative to the control (

Figure 4a). Stimulation in the stance phase also affected the movement characteristics of the hallux in the unstimulated swing phase. With L2 and L2+HAM+MG stimulation in the stance phase after the hallux left above the treadmill belt, the first peak of hallux lift increased by +8% (p< 0.05) and +30% (p < 0.001), respectively. With L2 stimulation, the second peak of hallux lift increased by +5% (not significant), and with L2+HAM+MG stimulation, the second peak decreased by -15% (p < 0.05).

When stimulating T12 and T12+TA in the swing phase, the integral of heel movement within the gait cycle did not change, while the integral of hallux movement increased by +33% (p < 0.0001) when stimulating T12+TA (

Figure 4b). During T12 stimulation in swing phase, the height of the ankle and heel lift remained unchanged. During T12+TA stimulation, the height of the ankle lift increased significantly by +5% (p < 0.05). The maximum height of the first and second peaks of the hallux lift did not change during T12 stimulation. However, during T12+TA stimulation, the maximum height first peak increased by +12% (p < 0.01), and the second peak increased by + 42% (p < 0.01) (

Figure 5b).

With combined stimulation of L2+HAM+MG during stance and T12+TA during swing, the integral of heel movement within the gait cycle increased by +44% (p < 0.001), and the integral of hallux movement increased by +51% (p < 0.001) (

Figure 4c).

Combined stimulation resulted in increasing, the height of the ankle lift by +34% (p< 0.001), and the maximum heel lift by +42% (p < 0.0001) (

Figure 5c). With L2+HAM+MG + T12+TA stimulation, the height of the first peak of the hallux lift increased by +31% (p < 0.001), and the second peak increased by +19% (not significant) (

Figure 5c).

Thus, L2+HAM+MG stimulation during stance increased the maximum heel lift by +42% (p < 0.001), while T12+TA stimulation during swing did not significantly change heel lift height. Combined L2+HAM+MG and T12+TA stimulation increased heel lift height by +42% (p<0.0001). With L2+HAM+MG stimulation, T12+TA stimulation, and combined L2+HAM+MG and T12+TA stimulation, the height of the first peak of hallux lift increased by +30% (p < 0.001), +12% (p < 0.01), and +31% (p < 0.001), respectively. The height of the second peak of the hallux lift decreased by -5% (p < 0.05), increased by +42% (p < 0.0001), and increased by +19% (not significant), respectively (

Figure 5a-c).

4. Discussion

There are currently two known spinal neuromodulation strategies directed to walking control. One uses tonic epidural stimulation of the spinal cord to optimize the excitability of spinal networks [

18]. The other is designed to rhythmically stimulate afferent fibers in the posterior roots that project to specific motor neuron pools. This strategy controls the swing and stance phases of stepping [

19].

The method of non-invasive, transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation to control stepping movements in non-injured subjects [

7] as well as in SCI subjects has been developed [

8,

20]. Novel method of regulating human gait through the non-invasive electrical stimulation of the spinal locomotor networks combining with stimulation of posterior roots to activate the flexor/extensor motor pools of the lower limbs in specific phases of the step cycle was reported [

11,

21]. Using this technology, we demonstrated improved kinematics during voluntary, non-weight-bearing locomotor-like stepping in a patient classified as AIS A with a SCI [

22]. At the same time, we observed that, with this neuromodulation strategy, SCI individual could not effectively perform body propulsion during stance phase and foot dorsiflexion during the swing phase.

In this study, we demonstrated that spatiotemporal alternating stimulation the posterior roots projecting to the leg flexor and extensor motor pools in combination with direct stimulation of the flexor and extensor leg muscles noticeably altered the structure of the gait (see Video S1). Stimulation during the stance phase increased forward propulsion; stimulation during the swing phase induced foot dorsiflexion; and stimulation during both phases modulated both forward propulsion and foot dorsiflexion.

4.1. Regulation of Stepping Movements During Spinal Cord and Muscle Stimulation

The results demonstrate the effectiveness of combining transcutaneous stimulation of the L2 posterior roots projecting to the leg's extensor motor pools and direct stimulation of the lower leg's extensor muscles (HAM and MG) in regulating the stance phase of stepping movements on a treadmill. According to [

21], rhythmic transcutaneous stimulation of the posterior root L1 in the stance phase leads to a shortening of the stance phase, increases the amplitude of movements in the hip joint, and decreases it in the knee and ankle joints [

8]. In the present study, it was found that rhythmic stimulation of L2+HAM+MG in the stance phase shortens the phase as a tendency, but at the same time increases the amplitude of movements in the hip, knee, and ankle joints, as well as significantly increases the elevation of the ankle and heel above the treadmill belt (

Figure 5). Thus, with combined stimulation of the posterior root L2 and extensor muscles, there is interaction between these two inputs, ensuring the lifting of the limb above the treadmill belt and the movement of the foot, which does not occur with stimulation of the posterior roots alone.

When walking on a treadmill, transcutaneous stimulation of the posterior roots (T12) projecting to the flexor motor pools of the leg and direct stimulation of the flexor muscles (TA) effectively regulated the limb swing phase. During the swing phase, stimulation of the T12 posterior root vs. stimulation of T12+TA had a weak effect. With both types of stimulation, heel lift height remained unchanged, while ankle lift increased with T12+TA stimulation. Previous studies have shown that rhythmic stimulation of the posterior root of T11 during the swing phase leads to an insignificant increase in the duration of this phase and an increase in the amplitude of flexion in the hip and ankle joints and knee lift [

8].

This study found that spinal-muscular stimulation of T12+TA during the swing phase increased the duration of this phase (

Figure 2b). The amplitude of movements in the hip, knee, and ankle joints did not change (

Figure 3b), but the length of the trajectory of movement of the hip, knee, and ankle joints increased. A study by Moshonkina and colleagues [

23] showed that with simultaneous continuous stimulation of the spinal cord at the C5–C6 level, T11–T12, and L1–L2, the maximum lift the foot above treadmill belt in the gait cycle is 10 ± 2 cm, and with rhythmic stimulation of MG+TA in certain phases of the gait cycle, the lift of the foot increases to 12 ± 2 cm. This value does not change with combined stimulation of the spinal cord and lower leg muscles [

23].

With combined stimulation of L2+HAM+MG in the stance phase and subsequent stimulation of T12+TA in the swing phase, the duration of the stance phase did not change, while the duration of the swing phase increased, and there was also a significant increase in the elevation of the ankle and heel above the treadmill belt. Combined stimulation led to an increase in the amplitude of movements in the hip, knee, and ankle joints, but at the same time, the length of their trajectory in the stance phase was shortened, and the duration of their movement in the swing phase increased.

The results obtained allow us to conclude that with combined stimulation of L2+HAM+MG in the stance phase and subsequent stimulation of T12+TA in the swing phase, their interaction occurred, facilitating forward propulsion and foot dorsiflexion.

4.2. Neurophysiological and Biomechanical Correlates of Forward Propulsion and Foot Dorsiflexion During Spinal and Muscular Stimulation

Propulsion is crucial for walking because it provides the force needed to move the body forward. It occurs during the stance phase, manifesting as the limb being lifted above the treadmill belt in combination with active foot plantar flexion. This causes the foot to push off from the treadmill belt. The following facts characterize the manifestation of forward propulsion during spinal-muscular stimulation. L2 stimulation during the stance phase increases the integral of heel and hallux during the gait cycle, as well as increasing the maximum height of ankle, heel and of the first and second hallux lift peaks. All of these values increase by around 10% relative to the control. When L2 is rhythmically stimulated in combination with extensor muscle stimulation (HAM+MG) during the stance phase, all these characteristics increase by around 35–40% relative to the control (see Results).

This indicates that stimulating the posterior root and the extensor muscles significantly enhances forward propulsion compared to stimulating the root alone. This is consistent with data obtained during continuous spinal cord stimulation combined with rhythmic extensor muscle stimulation (MG), which showed an increase of 2 cm in foot lift compared to spinal cord stimulation alone [

23]. Similar results were observed when analyzing the amplitude of movements in the ankle joint. With continuous spinal cord stimulation and rhythmic MG stimulation in the stance phase, the ankle joint movement amplitude increased by 4 degrees [

11]. In this study, with rhythmic L2 and L2+HAM+MG stimulation, the ankle joint movement amplitude increased by 6 degrees. With L2+HAM+MG stimulation, the large amplitude of ankle joint movement is mediated by a high heel lift as well as initial hallux lift during the unstimulated swing phase.

The following features were identified when comparing the movement of the heel and hallux. Forward propulsion begins with the heel lift. At this point, the hallux remains on above the treadmill belt. Judging by the slight deviation of its downward trajectory, foot plantarflexion (pushing the foot away from the belt) begins. The heel and hallux then simultaneously lift above the treadmill belt and the swing phase begins. In the control group, the maximum speed of heel movement from lift-off to maximum elevation was 1041 ± 134 mm/s. With L2 stimulation, this remained virtually unchanged; however, with L2+HAM+MG stimulation, the heel lift speed increased significantly to 1253 ± 142 mm/s. Similarly, the maximum speed of the hallux from lift-off to maximum elevation above the treadmill belt changed, from 972 ± 68 mm/s in the control group to 1150 ± 150 mm/s with L2+HAM+MG stimulation.

The temporary peaks of heel and hallux lift coincided. With L2+HAM+MG stimulation, the amplitude of heel lift above the treadmill belt increased by 42% (p < 0.001) and the amplitude of hallux lift increased by 30% (p < 0.001), relative to the control. The data obtained, as well as the difference in magnitude between heel and ankle lift in the control (19 mm) and during stimulation (25 mm), indicates stronger foot-off from the support surface during spinal-muscular stimulation, which facilitates forward propulsion.

Foot dorsiflexion occurs during the stance phase and is characterized by the lifting of the limb above the treadmill belt in conjunction with the active lifting of the hallux. During spinal-muscular stimulation, the peculiarities of foot dorsiflexion are that, with T12 stimulation, the height of the ankle and heel lift remains unchanged. However, with T12+TA stimulation, the ankle lift increases relative to the control from 69 ± 11 mm to 72 ± 12 mm). Additionally, during T12 and T12+TA stimulation, the integral of heel movement in the gait cycle remains unchanged, whereas the integral of hallux movement during T12+TA stimulation increases significantly by +33% (p<0.0001) (

Figure 4b). When T12+TA is stimulated in the swing phase, the heel trajectory length (644 ± 52 mm) and hallux trajectory length (621 ± 53 mm) increase relative to the control values (621 ± 56 mm and 605 ± 61 mm, respectively) (

Figure 5).

In the control group, the maximum speed of heel movement from lift-off to maximum elevation was 1061 ± 105 mm/s. With T12 stimulation, this increased to 1120 ± 107 mm/s, and with T12 + TA stimulation, it increased further to 1128 ± 109 mm/s. Meanwhile, the heel lift height remained unchanged.

During the swing phase with T12+TA stimulation the amplitude of the first hallux lift peak changed insignificantly. However, during stimulation, the amplitude of the second hallux lift peak (53 ± 14 mm) significantly exceeded that of the control group (40. ± 13 mm). In percentage terms, the first peak increased by +11.82% (p<0.01) and the second peak by +42% (p<0.01) with T12+TA stimulation (

Figure 5b). The increase in the second peak of hallux lift correlates with active foot dorsiflexion (

Figure 5).

Forward propulsion and foot dorsiflexion were facilitated by combined L2+HAM+MG stimulation during the stance phase and T12+TA stimulation during the swing phase (

Figure 6). Analysis showed that the kinematic characteristics of the heel and hallux during L2+HAM+MG stimulation and combined L2+HAM+MG and T12+TA stimulation are largely similar during stance and swing phases, respectively. The high speed of movement of the heel and hallux from lift-off to maximum elevation during combined stimulation (stance and swing) indicates the high effectiveness of forward propulsion during these phases. With combined stimulation, the height of the heel lift increased by +38% (p < 0.001). The height of the first and second peaks of hallux lift increased by +31% (p<0.001) and +19% respectively (not significant). These results provide evidence that combined stimulation of the posterior roots and extensor/flexor muscles during the stance and swing phases can effectively control forward propulsion and foot dorsiflexion.

5. Conclusions

The loss of joint coordination and gait dysfunction is a typical case in subjects after stroke, and gait recovery is a major objective in the rehabilitation for stroke patients. Traditional gait rehabilitation techniques in people post-stroke are functional electrical stimulation (FES), robotic devices, and brain-computer interfaces. However, each approach has some limitations. During FES, weak ankle plantar flexors and strong ankle dorsiflexors resulted in increased ankle dorsiflexion, which reduced drop foot [

24]. It was reported that the clinical and biomechanical gait functions of the individuals changed slightly during the FES course in the early recovery phase after ischemic stroke [

24]. There is a consensus that despite the significant technical progress achieved in the last 10 to 15 years in the FES field, these systems are not sufficiently advanced and that they need further development [

25].

It has been demonstrated that cervical epidural stimulation of the spinal cord can increase cerebral blood flow and restore motor function [

26]. Visocchi et al. reported an increase in regional cerebral blood flow in individuals who had experienced a stroke during spinal stimulation [

27]. This increase was accompanied by improved voluntary movements, reduced spasticity, increased endurance, the disappearance of abnormal muscle co-activation, improved coordination between muscles and reduced clonus. However, improved movement may not only be associated with improved cerebral hemodynamics.

It has been reported that using transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation as a therapeutic catalyst to gait training may increase the efficacy of gait rehabilitation in individuals with chronic stroke [

28,

29]. A new method of regulating gait in stroke patients has recently been proposed. It uses continuous stimulation of spinal locomotor neural networks in combination with spatiotemporal activation of the flexor and extensor motor pools of the leg during a specific phase of the gait cycle [

11]. While this spinal cord stimulation technology can modulate gait parameters in stroke patients, it also has limitations in this regard [

28,

29].

The results of these studies clearly indicate that spinal neuromodulation combining with direct stimulation of shin muscles is an effective tool in regulation of stepping movements in healthy individuals. It has been suggested that spinal targeted stimulation of the posterior roots that activate the flexor/extensor motor pools of the leg in certain phases of the gait cycle is related to neuromodulation of spinal locomotor network consisting of flexor and extensor half-centers. The second mechanism is the prosthesis of motor function by direct activation of flexor/extensor leg muscles in specific phases of locomotor cycle. Such stimulation dictates which muscle and to what degree have to be activated to provide stance and swing phases during stepping. The activation of these two mechanisms simultaneously has complementary effects to facilitate the stepping performance in healthy participants. Specifically, the stimulation of posterior roots (L2) and extensor shin muscles in stance phase facilitates forward propulsion whereas the stimulation of posterior roots (T12) and flexor shin muscles in swing phase facilitates foot dorsiflexion. Their combined stimulation in stance and swing phases resulted in integration of these two inputs with spinal locomotor network providing effective control of forward propulsion and foot dorsiflexion within one gait cycle.

Spinal cord stimulation is an effective treatment for gait disturbance after cerebral circulation disorders because it can affect different levels of the central nervous system, including the spinal cord and the brain [

30]. This necessitates the development of special rehabilitation programs and new stimulation technologies, including multisegmental spinal neuromodulation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Video S1: control walking without stimulation (top left), walking with stimulation of the right posterior root L2 and right extensor leg muscles during the stance phase of the right leg (bottom left), walking with stimulation of the right posterior root T12 and right flexor leg muscles during the swing phase of the right leg (top right), walking with stimulation of the right posterior root L2 and the right extensor leg muscles during the stance phase of the right leg, and stimulation of the right posterior root T12 and the right flexor leg muscles during the swing phase of the right leg (bottom right).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G.; methodology, S.A., T.M. and A.G..; software, I.S., V.L. and A.G.; validation, I.S. and V.L.; formal analysis, V.L. and I.S.; investigation, S.A., I.S. and Y.G.; resources, T.M.; data curation, T.M. and Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.G. and S.A.; writing—review and editing, Y.G. and T.M.; visualization, I.S. and V.L.; supervision, Y.G.; project administration, funding acquisition, T.M. and Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by state funding allocated to the Pavlov Institute of Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences (No. 1021062411782-5-3.1.8), as well as by Cosyma LLC funding for the Pavlov Institute of Physiology, Russian Academy of Sciences' study on the theme of 'Searching for optimal methods for analysing movements recorded during transcutaneous electrical stimulation of the human spinal cord' (No. 2025-10-01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Pavlov Institute of Physiology Ethics Committee (Minutes № 25-01, dated 25 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the research participants and Elena Prazdnikova for her assistance with participant recruitment

Conflicts of Interest

Yury Gerasimenko, Tatiana Moshonkina and Alexandr Grishin are researchers on the study team and hold shareholder interest in Cosyma LLC (Moscow, Russia). They hold certain inventorship rights on intellectual property licensed by Cosyma LLC. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIS |

ASIA Impairment Scale |

| ASIA |

American Spinal Injury Association |

| FES |

functional electrical stimulation |

| HAM |

right hamstring muscles |

| L2 |

right spinal cord roots at L2 vertebrae level |

| MG |

right m. gastrocnemius |

| SCI |

spinal cord injury |

| T12 |

right spinal cord roots at T12 vertebrae level |

| TA |

right m. tibialis anterior |

| TSV |

tab-separated values |

References

- Yu, P.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Sheng, C.; So, K.-F.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, H. The Effects and Potential Mechanisms of Locomotor Training on Improvements of Functional Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury. In International Review of Neurobiology; Elsevier, 2019; Vol. 147, pp. 199–217 ISBN 978-0-12-816967-4.

- Loy, K.; Bareyre, FlorenceM. Rehabilitation Following Spinal Cord Injury: How Animal Models Can Help Our Understanding of Exercise-Induced Neuroplasticity. Neural Regen Res 2019, 14, 405. [CrossRef]

- Samejima, S.; Henderson, R.; Pradarelli, J.; Mondello, S.E.; Moritz, C.T. Activity-Dependent Plasticity and Spinal Cord Stimulation for Motor Recovery Following Spinal Cord Injury. Experimental Neurology 2022, 357, 114178. [CrossRef]

- Duysens, J.; Van de Crommert, H.W.A.A. Neural Control of Locomotion; Part 1: The Central Pattern Generator from Cats to Humans. Gait & Posture 1998, 7, 131–141. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijevic, M.R.; Gerasimenko, Y.; Pinter, M.M. Evidence for a Spinal Central Pattern Generator in Humans. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1998, 860, 360–376. [CrossRef]

- Dietz, V. Spinal Cord Pattern Generators for Locomotion. Clinical Neurophysiology 2003, 114, 1379–1389. [CrossRef]

- Gorodnichev, R.M.; Pivovarova, E.A.; Puhov, A.; Moiseev, S.A.; Gerasimenko, Y.P.; Savochin, A.A.; Moshonkina, T.R.; Chsherbakova, N.A.; Kilimnik, V.A.; Selionov, V.A.; et al. Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation of the Spinal Cord: A Noninvasive Tool for the Activation of Stepping Pattern Generators in Humans. Human Physiology 2012, 38, 158–167. [CrossRef]

- Gerasimenko, Y.; Gorodnichev, R.; Moshonkina, T.; Sayenko, D.; Gad, P.; Reggie Edgerton, V. Transcutaneous Electrical Spinal-Cord Stimulation in Humans. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 2015, 58, 225–231. [CrossRef]

- Angeli, C.; Rejc, E.; Boakye, M.; Herrity, A.; Mesbah, S.; Hubscher, C.; Forrest, G.; Harkema, S. Targeted Selection of Stimulation Parameters for Restoration of Motor and Autonomic Function in Individuals With Spinal Cord Injury. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface 2024, 27, 645–660. [CrossRef]

- Gill, M.L.; Grahn, P.J.; Calvert, J.S.; Linde, M.B.; Lavrov, I.A.; Strommen, J.A.; Beck, L.A.; Sayenko, D.G.; Van Straaten, M.G.; Drubach, D.I.; et al. Neuromodulation of Lumbosacral Spinal Networks Enables Independent Stepping after Complete Paraplegia. Nat Med 2018, 24, 1677–1682. [CrossRef]

- Moshonkina, T.; Grishin, A.; Bogacheva, I.; Gorodnichev, R.; Ovechkin, A.; Siu, R.; Edgerton, V.R.; Gerasimenko, Y. Novel Non-Invasive Strategy for Spinal Neuromodulation to Control Human Locomotion. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 622533. [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C.A.; Hicks, A.L. Muscle Fatigue Characteristics in Paralyzed Muscle after Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord 2011, 49, 125–130. [CrossRef]

- Vastano, R.; Perez, M.A. Changes in Motoneuron Excitability during Voluntary Muscle Activity in Humans with Spinal Cord Injury. J Neurophysiol.

- Grishin, A.A.; Bobrova, E.V.; Reshetnikova, V.V.; Moshonkina, T.R.; Gerasimenko, Yu.P. A System for Detecting Stepping Cycle Phases and Spinal Cord Stimulation as a Tool for Controlling Human Locomotion. Biomed Eng 2021, 54, 312–316. [CrossRef]

- Anwary, A.R.; Yu, H.; Vassallo, M. An Automatic Gait Feature Extraction Method for Identifying Gait Asymmetry Using Wearable Sensors. Sensors 2018, 18, 676. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Max, L. Accuracy and Precision of a Custom Camera-Based System for 2-D and 3-D Motion Tracking During Speech and Nonspeech Motor Tasks. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2014, 57, 426–438. [CrossRef]

- Leardini, A.; Sawacha, Z.; Paolini, G.; Ingrosso, S.; Nativo, R.; Benedetti, M.G. A New Anatomically Based Protocol for Gait Analysis in Children. Gait & Posture 2007, 26, 560–571. [CrossRef]

- Harkema, S.; Angeli, C.; Gerasimenko, Y. Historical Development and Contemporary Use of Neuromodulation in Human Spinal Cord Injury. Current Opinion in Neurology 2022, 35, 536–543. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, F.B.; Mignardot, J.-B.; Le Goff-Mignardot, C.G.; Demesmaeker, R.; Komi, S.; Capogrosso, M.; Rowald, A.; Seáñez, I.; Caban, M.; Pirondini, E.; et al. Targeted Neurotechnology Restores Walking in Humans with Spinal Cord Injury. Nature 2018, 563, 65–71. [CrossRef]

- Gerasimenko, Y.P.; Lu, D.C.; Modaber, M.; Zdunowski, S.; Gad, P.; Sayenko, D.G.; Morikawa, E.; Haakana, P.; Ferguson, A.R.; Roy, R.R.; et al. Noninvasive Reactivation of Motor Descending Control after Paralysis. J Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 1968–1980. [CrossRef]

- Gorodnichev, R.M.; Pukhov, A.M.; Moiseev, S.; Ivanov, S.; Markevich, V.; Bogacheva, I.; Grishin, A.; Moshonkina, T.R.; Gerasimenko, Y.P. Regulation of Gait Cycle Phases during Noninvasive Electrical Stimulation of the Spinal Cord. Human Physiology 2021, 47, 60–69. [CrossRef]

- Siu, R.; Brown, E.H.; Mesbah, S.; Gonnelli, F.; Pisolkar, T.; Edgerton, V.R.; Ovechkin, A.V.; Gerasimenko, Y.P. Novel Noninvasive Spinal Neuromodulation Strategy Facilitates Recovery of Stepping after Motor Complete Paraplegia. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 3670. [CrossRef]

- Moshonkina, T.R.; Ananyev, S.S.; Lyakhovetskii, V.A.; Grishin, A.A.; Gerasimenko, Y.P. Control of Walking Cycle Using Noninvasive Electrical Stimulation of the Spinal Cord and Muscles. Human physiology 2025, 51, doi:DOI:%2010.7868/S30346150250504e2.

- Santos, G.F.; Jakubowitz, E.; Pronost, N.; Bonis, T.; Hurschler, C. Predictive Simulation of Post-Stroke Gait with Functional Electrical Stimulation. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 21351. [CrossRef]

- Skvortsov, D.V.; Grebenkina, N.V.; Klimov, L.V.; Kaurkin, S.N.; Bulatova, M.A.; Ivanova, G.E. Functional Electrical Stimulation for Gait Correction in the Early Recovery Phase after Ischemic Stroke. jour 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hosobuchi, Y. Treatment of Cerebral Ischemia with Electrical Stimulation of the Cervical Spinal Cord. Pacing Clinical Electrophis 1991, 14, 122–126. [CrossRef]

- Visocchi, M.; Giordano, A.; Calcagni, M.; Cioni, B.; Di Rocco, F.; Meglio, M. Spinal Cord Stimulation and Cerebral Blood Flow in Stroke: Personal Experience. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 2002, 76, 262–268. [CrossRef]

- Moshonkina, T.R.; Zharova, E.N.; Ananev, S.S.; Shandybina, N.D.; Vershinina, E.A.; Lyakhovetskii, V.A.; Grishin, A.A.; Shlyakhto, E.V.; Gerasimenko, Y.P. A New Technology for Recovery of Locomotion in Patients after a Stroke. Dokl Biochem Biophys 2022, 507, 353–356. [CrossRef]

- Moshonkina, T.; Zharova, E.; Ananydev, S.; Shandybina, N.; Vershinina, E.; Lyakhovetskii, V.; Grisin, A.; Gerasimenko, Y. New Technology for Stroke Rehabilitation. Nep J Neurosci 2025, 22, 15–20. [CrossRef]

- Karbasforoushan, H.; Cohen-Adad, J.; Dewald, J.P.A. Brainstem and Spinal Cord MRI Identifies Altered Sensorimotor Pathways Post-Stroke. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3524. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).