Introduction

In the face of global challenges such as climate change and resource depletion, sustainable food choices and dietary habits have gained prominence in research and government policy [

1,

2]. Currently, food production contributes to around one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions [

1]. Policy makers have recognized that unsustainable dietary practices, characterized by the overconsumption of animal-based products and extensive food waste, are significant contributors to environmental degradation [

1,

3]. In response, dietary guidelines increasingly recommend sustainable, plant-based eating patterns to promote human and environmental health [

4,

5]. For example, the EAT–Lancet Commission proposed a sustainable diet pattern (the EAT–Lancet diet) and defined pescatarian, vegetarian and vegan variants to support transitions towards this pattern, emphasising whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts and unsaturated oils, while reducing animal foods (e.g. poultry and seafood) and limiting red and processed meat, sugar, refined grains and starchy vegetables [

4,

5].

While many consumers report an interest in healthy and environmentally sustainable habits [

6], surveys consistently show a mismatch between their stated beliefs and their actual behaviour [

7]. This mismatch is variously described as the intention–behaviour gap [

8], the motivation–behaviour gap [

9] or, in the context of environmental sustainability, the green intention–behaviour gap [

10]. In recent years, sustainable diet research has expanded, but relatively few studies and reviews have focused explicitly on this intention–behaviour gap [

7,

11]. This has practical consequences: a recent umbrella review found that global initiatives rely heavily on labelling and information campaigns [

12]. While these strategies may successfully target consumer

intentions, they frequently fail to bridge the gap to

behaviour because they do not address the structural constraints that block action (Vargas et al., 2025). Nonetheless, if governments are to meet ambitious net-zero targets, bridging this gap is crucial.

To advance this goal, this paper adopts a systems approach, drawing on ecological psychology [

13] and contemporary active inference accounts of perception and action [

14] (Box 1 Glossary of Terms). Ecological psychology focuses on the relationship between individuals and their environments and emphasises how perception and action are interconnected [

15], introducing the concept of affordances: possibilities for action that depend jointly on the organism and its surroundings. Active inference, in turn, treats behaviour as the selection of actions that minimise uncertainty and risk (technically, expected “surprise”) relative to goals or prior preferences, given the constraints of the current context [

16,

17]. Together, these approaches support a systems view of the dynamic coupling between people and their environments: dietary choices arise from the actions that are available and achievable in each context. This combined perspective addresses a key limitation of traditional theories (

Table 1), which typically treat personal and environmental factors as independent, static influences rather than as mutually shaping, evolving processes. While the social determinants of health are well-established, existing literature has largely remained descriptive cataloguing

that poverty correlates with poor diet. This paper moves from description to mechanism. By formalising dietary behaviour as policy selection under constraints, we provide a computational account of

how environmental deficits (time, funds, access) are translated by the brain into specific dietary choices. This de-stigmatizes the behaviour, reframing the consumption of energy-dense foods not as a failure of self-regulation, but as a successfully optimized strategy for minimizing metabolic and financial risk in a structurally misaligned environment.

Box 1.

Glossary of Terms.

Box 1.

Glossary of Terms.

| Glossary |

|

| Sustainable Diet |

A dietary pattern that supports health while reducing environmental impacts (e.g., greenhouse gas emissions, land and water use) and maintaining nutritional adequacy. |

| Intention |

An intention is a mental representation of a planned future action or outcome (e.g., “eat more plant-based meals”), which can arise from deliberate reflection or habitual processes. Intentions organize and guide behavior but do not guarantee that the intended action will be carried out. |

| Intention–Behaviour Gap |

The discrepancy between what people endorse as their goals or intentions and what they enact in everyday behaviour. |

| Dietary Affordance |

The feasible set of food-related actions available to an individual in context, arising from person–environment interaction (e.g., time, income, skills, access, infrastructure, pricing). In active inference terms, dietary affordances define the feasible behavioural policy set. We formalise the affordance strength of option as the product of its pragmatic value and its predictive precision : |

|

Affordance field ()

|

The feasible set of food-related options available and achievable for an individual in a given context (the feasible policy set). |

| Active inference |

A framework in which agents select actions (policies) that reduce expected uncertainty and risk relative to prior preferences (preferred states), often described as minimising expected free energy. |

|

Pragmatic value ()

|

The option’s motivational attractiveness to the individual in context (what it is “worth” to them under current constraints), which may reflect cue-driven motivational pull and does not necessarily equal reported enjoyment. |

|

Normative value

|

The value of option judged against public goals such as health and sustainability, which may diverge from pragmatic value. |

| Predictive precision (Pi) |

The expected reliability with which option can be enacted (predictable cost, availability, time/effort, and household acceptance). Low reflects volatile or failure-prone execution (e.g., stock-outs, price spikes, time overruns, spoilage risk). |

| Policy (active inference) |

A candidate course of action (e.g., “cook from scratch,” “buy ready meals”) evaluated in terms of expected outcomes, effort, and risk (distinct from governmental policy). |

| Prior preferences |

Prior preferences are high-level, desired states encoded in the agent’s model of the world (e.g., being healthy, avoiding hunger, staying within budget, minimizing waste, “eating sustainably”). They define what counts as a “good” or “bad” outcome and shape the evaluation of different policies. |

| Variational Free Energy (Information Theory) |

A mathematical quantity describing the upper bound on "surprise" (prediction error). In active inference, agents act to minimize expected free energy. Note: This is an information-theoretic value representing uncertainty and risk; it is distinct from and should not be confused with thermodynamic or metabolic energy (e.g., kilocalories) |

| Leverage point |

A place in a system where a small change produces a big shift; here, changes that alter what food options are feasible or reliably doable (e.g., price, access, infrastructure, retail cues, social protection). |

| Heuristic |

A simple rule-of-thumb or lens for making sense of complex choices; here, “dietary affordances” is used as a lens to diagnose what makes sustainable eating easy or hard in real settings. |

Table 1.

Dominant health psychology theories viewed through an Active Inference lens.

Table 1.

Dominant health psychology theories viewed through an Active Inference lens.

| Main theory |

Core prediction / treatment of the gap |

The Active Inference Reframe (The Missing Mechanism) |

| Temporal Self-Regulation Theory (TST) |

Behavior is a balance between distal intentions and proximal urges. Gaps occur when immediate rewards (taste, convenience) outweigh delayed health benefits, or when "temptation" undermines self-regulation. |

TST frames the environment as "temptation" (competing reward). Active inference reframes this as a competition of precision: unsustainable habits are selected not because the consumer is "weak," but because processed food offers a high-precision policy (guaranteed outcome) that minimizes uncertainty. The gap opens because sustainable intentions function as low-precision priors in a volatile environment. |

| Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) |

Behavior is shaped by reciprocal interactions between people, behavior, and environment. Gaps arise when self-efficacy is low or when the environment fails to reinforce the new behavior. |

SCT acknowledges reciprocal causation but often models it linearly. It lacks a mechanism to explain how the environment becomes internalized. We argue the environment acts as a generator of priors: repeated exposure to 'food swamps' physically updates the generative model, increasing the precision of unhealthy habits until they become automatic, bypassing cognitive control entirely. |

| Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) |

Behavior is determined by intentions, moderated by Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC). Gaps occur when intentions are high but perceived control is low due to barriers. |

TPB treats the environment as a static "control belief" (PBC). This fails to capture how structural constraints prune the decision tree. Even with favorable attitudes, if the environment fails to afford a low-risk policy, the sustainable action is effectively invisible to the generative model, rendering the "intention" mathematically inert regardless of self-regulation. |

| Health Belief Model (HBM) |

Behavior is driven by a rational assessment of susceptibility, severity, benefits, and barriers. Gaps arise when perceived barriers outweigh perceived benefits. |

HBM assumes a "cost-benefit" calculation. We argue the brain minimizes surprise (variational free energy), not just cost. A user may reject a "beneficial" sustainable diet because the informational cost (uncertainty of cooking, risk of waste) is too high. Unsustainable choices are often the result of rational uncertainty minimization, not a failure to understand health risks. |

| Self-Determination Theory (SDT) |

Behavior is maintained when motivation is autonomous and satisfies needs (autonomy, competence, relatedness). Gaps occur when motivation is controlled or extrinsic. |

SDT focuses on the quality of motivation. However, even the most autonomously motivated agent cannot act if there is a structural misalignment between their goals and the feasible policy set. Affordance theory highlights that motivation is necessary but insufficient; the environment must provide a "bridge affordance" to allow that motivation to be enacted without prohibitive metabolic or cognitive cost. |

| Transtheoretical Model (TTM) |

Individuals move through stages (pre-contemplation to maintenance). Gaps occur when individuals stall in preparation without progressing to action. |

TTM describes that change happens in stages, but not why the shift occurs. We view stage transitions as non-linear phase transitions driven by environmental precision. A small change in affordance (e.g., a subsidized canteen) can act as a leverage point, tipping the system past a critical threshold from "deliberation" (Contemplation) to "automaticity" (Maintenance). |

| COM-B Model |

Behavior requires Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation. Gaps occur when any component is missing (e.g., lack of opportunity). |

COM-B is useful but "Opportunity" remains a broad checklist. We refine this by operationalizing Opportunity as the feasible policy set: it is not enough for the option to exist; it must minimize expected free energy (effort/risk) sufficiently to become the path of least resistance. If the sustainable option is high friction, the brain treats the opportunity as effectively null. |

In this perspective, we (1) outline the limits of existing intention–behaviour models for sustainable eating, (2) establish dietary affordances as both a mechanistic bridge linking environmental constraints to neurocognitive decision-making and a practical heuristic for auditing food systems, and (3) show how this framework moves the 'systems approach' from a descriptive metaphor to a predictive tool for policy. By developing this systems-oriented framework, we argue that closing the sustainable eating intention–behaviour gap will depend less on further strengthening individual motivation and more on re-engineering food environments so that the actions (or behavioural ‘policies’) people can most easily and safely enact are also those that support sustainable, nutritionally adequate diets.

The Intention–Behaviour Gap

The intention–behaviour gap is usually discussed through the lens of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB [

18]. In TPB, intentions are treated as the proximal determinant of behaviour, shaped by attitudes, perceived social norms, and perceived behavioural control (PBC) - the sense that a behaviour is realistically within one’s reach [

18,

19]. On this account, stronger intentions and higher PBC should, in principle, translate into action. In practice, they often do not. Meta-analytic reviews show that TPB variables account for substantially more variance in intentions than in behaviour: attitudes, norms, and PBC together explain around 40% of the variance in intentions, but only about 20–30% of the variance in actual behaviour [

8,

19,

20]. In other words, strengthening intentions and perceived control improves prediction, but leaves most of what people do unexplained. Sustainable eating is no exception. Blanke, et al. [

21] reported that, in a staff sample, intentions and self-reported behaviour were both higher for healthy than for sustainable grocery shopping, but that a significant intention–action gap existed for both and was larger for sustainability. This suggests that, even when people endorse health and sustainability goals, sustainable options are experienced as harder to translate into everyday shopping practices. O'Keefe, et al [

6] similarly reported that consumers were willing, in principle, to reduce meat intake by around 20%, yet this willingness did not extend to broader, coordinated changes across the rest of the diet. More generally, many households maintain a strong reliance on convenient, processed foods even when they endorse health and sustainability goals [

21,

22]. From an active inference perspective, this kind of reliance on convenient, processed foods can be understood as a high-precision habitual policy: a well-learned course of action that reliably delivers satiety under time and budget constraints and therefore carries more “weight” in everyday decision-making than newer, more uncertain sustainable intentions. Related work on grounded and situated cognition in eating shows that specific food cues and contexts trigger rich simulations of consumption, making some options feel immediately desirable and “ready-to-act-on” while others remain comparatively abstract [

23]. In practice, this means that convenient, highly cued options are not just available; they are experienced as the most obvious and actionable policies in a given setting.

Conventional interpretations of the intention–behaviour gap have largely emphasized individual-level explanations, that is limited self-regulation, weak motivation, competing goals, or biased risk appraisals [

8,

19]. In that framing, the environment typically appears only as perceived barriers or facilitators, captured in measures of perceived behavioural control, and shortfalls between intentions and action are usually cast as individual failures to overcome such barriers rather than as properties of the wider system.

In the systems-oriented account we develop here, informed by ecological psychology and active inference (Friston et al., 2012, 2013), we start from a different premise. We treat the gap as a “structural misalignment” between what people would like to do and the set of food-related actions that are realistically available, affordable, and low-risk in their everyday environments. By structural misalignment we mean that intentions point in one direction (e.g., “buy more sustainable foods,” “reduce meat consumption”), while the lowest-effort, lowest-risk, and most predictable options in each context point somewhere else. This is evident, for example, in the difficulties participants report in enacting sustainable purchasing relative to health goals [

21], and in the selective application of sustainability intentions, such as willingness to reduce meat intake without broader changes to processed food consumption [

6]. Put differently, many apparent “failures” of sustainable eating intentions are predictable responses to constrained dietary affordances: this is, when the everyday affordance field makes less sustainable options the safest and least disruptive policies, it is unsurprising that people choose them. This shift - from locating the problem primarily in individual shortcomings to focusing on the relational properties of people in environments - sets the stage for our use of “dietary affordances” as a more informative unit of analysis for understanding, and ultimately reducing, the sustainable eating intention–behaviour gap. Before introducing dietary affordances in detail, it is useful to clarify what we mean by “intention” within this broader systems-oriented account.

What are Intentions?

Intentions occupy a central place in psychological and behavioural theories: they are typically treated as the immediate precursors to action and as key outputs of deliberation and decision-making. At a basic level, an intention is a commitment or plan to engage in a specific behaviour in the future (e.g., “cook more plant-based meals on weeknights”). However, the nature of intentions, that is how they are formed, represented, and enacted, varies across theoretical frameworks.

A useful starting point is the distinction between different kinds of cognitive process. Dual-process accounts describe Type 1 processes as fast, automatic, and often unconscious, and Type 2 processes as slower, deliberative, and goal-directed [

24,

25]. Related work on construal level theory distinguishes between high-level, abstract “why” representations and low-level, concrete “how” representations of action [

26]. Some intentions are clearly the product of explicit, Type 2 reasoning (for example, deciding to follow dietary guidelines [

27] for health or environmental reasons), whereas others are more implicit, arising from repeated patterns of behaviour and context that function as “automatic intentions” or habits [

28]. In everyday life, expressed intentions often reflect a mixture of these elements: people articulate deliberate goals, but their actions are also guided by well-learned, context-sensitive response tendencies that require little conscious reflection.

In the active inference perspective we draw on, these different forms of intention can be viewed as expressions of prior preferences at different levels of abstraction - from high-level, verbally endorsed goals (for example, “eat more sustainably”) to low-level, habitual policies that have acquired high precision through repetition in particular environments [

14,

16,

29]. On this view, intentions are not only what people say they want to do, but also the entrenched patterns of action that their nervous system has learned to treat as reliable solutions to everyday demands. This framing helps to bridge dual-process accounts and the systems-oriented analysis that follows, in which we focus on the dietary affordances that shape which policies are even available for those intentions to be expressed. It also clarifies why strengthening verbally stated intentions alone (e.g., through education campaigns) is unlikely to close the sustainable eating intention–behaviour gap: high-level goals must compete with entrenched, high-precision habitual policies that are tuned to the constraints of everyday life. In the next section, we therefore shift attention from intentions themselves to the affordance structure of food environments and ask how changing that structure can realign habitual actions and policies with people’s stated health and sustainability goals.

Introducing Dietary Affordances

Intentions do not operate in a vacuum; they must be enacted within the hard constraints of reality. It is here that we introduce the construct of dietary affordances to occupy the crucial middle ground between internal intentions and observable behaviour.

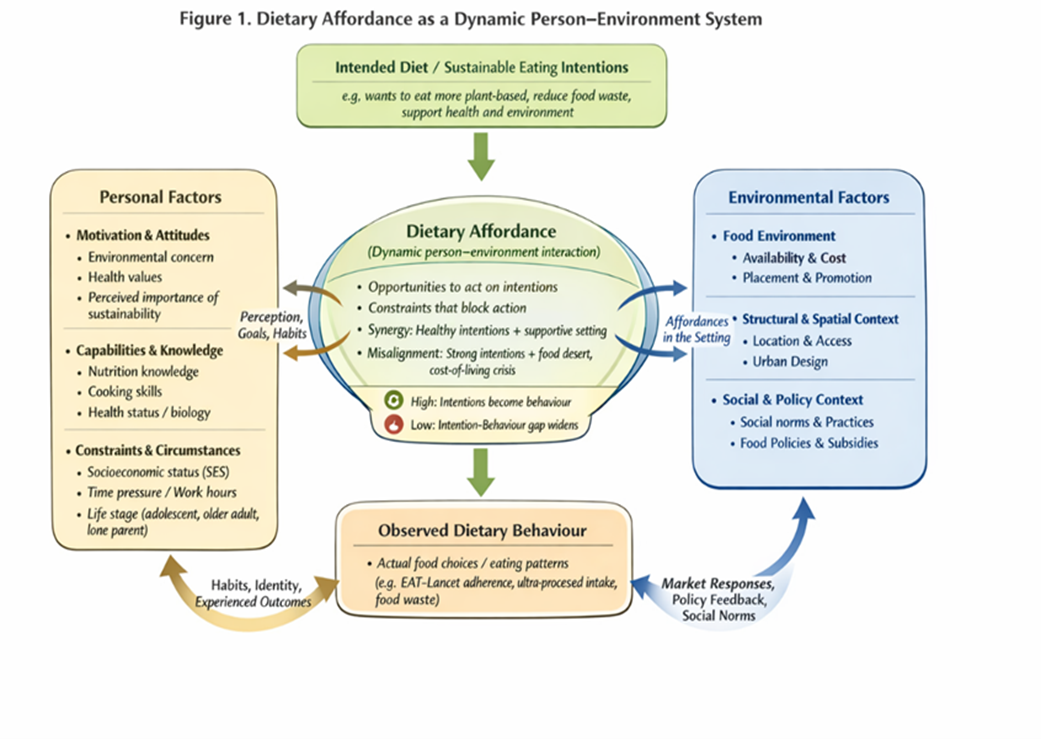

Drawing on ecological psychology, we define affordances not merely as physical properties, but as relational possibilities for action that emerge from the structural coupling between an environment and an individual [

13] (

Figure 1). A setting does not afford the same actions to everyone; its opportunities are dictated by the specific capabilities, resources, and needs of the person who encounters it [

15,

23]. The same supermarket offers a vastly different “menu” of choices to a wealthy retiree than it does to a time-poor single parent.

Crucially, from an active inference perspective, these affordances define the behavioural policy set: the hard boundary of action sequences an agent can realistically consider [

14,

16,

17]. This reframes the “choice” to eat unsustainably. For a parent working irregular hours with limited funds, “heat a ready meal” or “order takeout” are not failures of self-regulation; they are high-precision behavioural policies - reliable, low-risk solutions to the urgent problem of feeding a household. In such a context, “prepare a plant-based meal from scratch” effectively drops out of the feasible policy set entirely; it is too risky (potential rejection), too time-consuming, and too financially precarious to be a viable prediction. By contrast, a household with stable income and a well-equipped kitchen inhabits a fundamentally different affordance field, where batch cooking and experimenting with legumes become realistic, low-risk options.

More formally, we define dietary affordances as the set of food-related actions that are realistically available and achievable for an individual in a given context. These affordances emerge from the dynamic interaction between personal factors (e.g., income, time, cooking skills, health status, preferences) and environmental factors (e.g., price, retail layout, transport, cooking facilities, social norms). When these factors align, a synergistic effect can occur: the interaction creates a non-linear amplification of the behavioural pull, where the environment acts as a scaffold that transforms a weak preference into a high-precision habit.

In active inference terms, this non-linearity arises because predictive precision acts as a multiplicative “gain” on action selection. To reflect this gain effect in a parsimonious form, we approximate the affordance strength of each feasible option

as the product of its pragmatic value

and predictive precision

:

where

denotes the affordance field (the set of feasible options available in a given context). This relationship implies that when precision

is very low (for example, because outcomes are volatile or the option is complex and failure-prone), affordance strength

approaches zero, regardless of how much the individual values the goal. Conversely, small improvements in affordability or convenience can increase precision enough to tip an option past a critical threshold, shifting it from high-effort deliberation to an automatic default.

For example, an office worker who intends to eat more healthily is more likely to do so when the workplace cafeteria reliably affords that behaviour (through a clean space and a visible, appealing salad bar) than when only energy-dense options are prominently displayed. Here, the interaction between personal motivation () and environmental precision () produces a choice that would be unlikely if either were weak or absent.

Crucially, this is not simply a matter of “having options” in an abstract sense. Each afforded policy carries expected costs, risks, and rewards: the probability of food waste, the impact on the weekly budget, and the social acceptability of the meal. Policies that repeatedly “work” under these constraints acquire high precision and become entrenched habits. This formulation allows us to move beyond treating the ‘systems approach’ as a descriptive metaphor. By providing a formal computational account of the non-linear relationship between environmental precision and habit formation, we provide a mechanistic account of why small structural changes - or ‘leverage points’ - can produce disproportionate shifts in dietary behaviour.

Food labelling provides an everyday example of how affordances can fail when they do not align with these constraints. In principle, mandates such as Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 are designed to afford healthful choice by ensuring that nutritional information is physically available. However, in routine supermarket shopping, only a minority of consumers attend to nutrition information at the point of choice: across six product categories, 16.8% of shoppers were observed to look for nutrition information on the label [

30].

Psychologically, precision estimation can be understood as an attentional filter: beyond processing sensory data, the agent continuously evaluates the reliability and decision-relevance of that data in context [

31]. Computational simulations of selective attention within active inference show that when the inferred relevance of a sensory channel is low, the expected informational value of sampling it declines, and agents correspondingly allocate fewer resources to that channel [

32]. In the supermarket, this mechanism explains why data availability does not translate into data usage. If a time-poor consumer holds an a priori expectation that nutritional labels do not convey reliable utility relative to the cognitive cost of decoding them, they effectively attenuate that sensory channel. They are less likely to attend to let alone rely on, this information because they implicitly estimate that the expected information gain from reading the label is lower than the cost in time and effort [

30]. For most, decoding these panels remains a high-effort affordance recruited only when there are precise, Type-2 (deliberative) intentions (e.g. actively comparing sugar content) and sufficient time to act on them.

For policymakers, including the Food Standards Agency (FSA) and Defra, this illustrates why focusing on “information” alone is insufficient: adding mandatory data to an unchanged affordance field or retail environment rarely alters the high-precision habits driven by time and cost pressures.

Explaining the Gap: Type 1 vs. Type 2 Processing

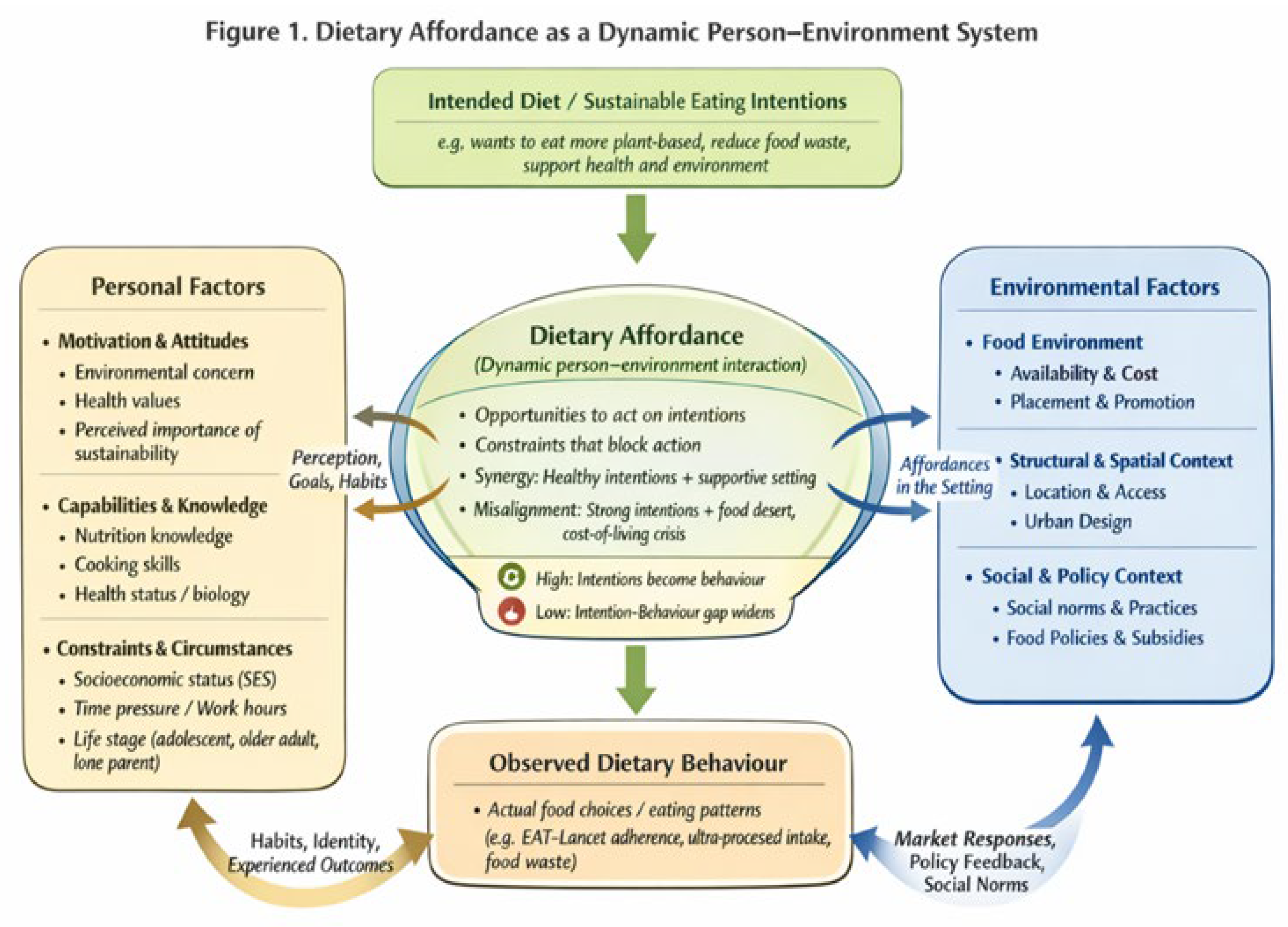

From this perspective, the sustainable eating intention–behaviour gap is not a failure of individual self-regulation, but a predictable, rational outcome of Bayesian optimization. Many dual-process accounts in health psychology frame this gap as a conflict between reflective goal directed Type 2 deliberation and impulsive cue driven Type 1 urges, with behaviour expected to shift toward the latter when control capacity is constrained [

25,

33,

34,

35,

36]. We challenge this deficit-based view. In an active inference framework, the dominance of unsustainable habits is not a loss of control; it is the maximization of model evidence [

16,

37,

38] (

Figure 2).

The brain constantly weighs competing policies based on their expected free energy (in this framework, “free energy” refers to an information-theoretic measure of uncertainty and risk, not to metabolic energy or calories), effectively a trade-off between the value of the goal and the certainty of achieving it [

39,

40,

41]. In constrained food environments, sustainable intentions (“eat plant-based”) typically function as low-precision priors: they are abstract, often expensive, and carry high variation in availability and quality [

38,

41]. Conversely, unsustainable options (“buy processed food”) operate as high-precision policies: they offer guaranteed satiety, fixed prices, and zero preparation failure rates [

37,

41]. Crucially, this precision extends to the sensory experience itself [

38,

40]. While natural foods vary in quality (a ripe vs. unripe fruit), ultra-processed foods are engineered for hyper-consistency, delivering a predictable dopaminergic reward every time [

14,

42]. In active inference, this lack of sensory variance effectively minimizes “hedonic surprise,” leading the brain to weight the processed option as the safer biological bet [

14,

38,

43]. When these two compete under pressure, the brain does not “fail” by choosing the processed option; it correctly identifies it as the optimal solution to the problem of minimizing metabolic and financial risk (

Figure 2).

Schematic illustration of dietary choice as policy selection under constraint. The upper panel depicts a reflective (Type 2) pathway in which nutritional preferences and health/sustainability goals generate a preferred set of sustainable policies. However, enactment depends on the feasible policy set available in context (the affordance field), which is shaped by practical constraints such as access, cost, time, skills, and household acceptability; options that are unreliable or infeasible are therefore unlikely to be selected. The lower panel depicts a cue-driven (Type 1) pathway in which environmental cues activate learned associations and habitual policies that are selected because they are reliably enacted (high precision) and minimise expected risk and effort. The dashed links indicate where preferred (intended) sustainable policies fail to translate into action when sustainable options are low precision (e.g., volatile costs/availability or high failure risk), leading to default selection of higher-precision habitual policies.

This reframing helps explain why interventions that focus on manipulating representations, such as framing tasks or “future thinking” exercises, can face a hard ceiling when the material environment is left unchanged. Experimental paradigms often rely on altering psychological distance or construal level while leaving the practical choice context constant [

26]. In active inference terms, such manipulations can increase the salience of higher-level goals by increasing the precision-weighting of preferences (our pragmatic value term,

). However, they typically do not increase the reliability with which the relevant actions can be executed in context (our enactment precision term,

). If the environment remains volatile or high friction, increasing goal salience therefore risks creating a precision mismatch: the person values the sustainable outcome more (higher

), but their generative model still predicts that the sustainable action is likely to fail (low

). Once the artificial support of the intervention is removed, the system predictably reverts to the policy with the highest historical reliability. Closing the gap, therefore, requires a shift from “motivating individuals” to “engineering precision”: reshaping the material, social, and institutional affordance field so that sustainable policies become the safest, most predictable route to satiety.

Limits of Dominant Behaviour Change Frameworks for Sustainable Diets

Over the past few decades, health psychology has developed a range of influential frameworks for understanding and changing behaviour, including the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) [

18], Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [

44], Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [

45], the Health Belief Model (HBM) [

46], the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) [

47], Temporal Self-Regulation Theory (TST) [

48], and the COM-B model [

49]. These models have been invaluable in cataloguing the determinants of behaviour - identifying

what matters (attitudes, norms, efficacy). However, when applied to sustainable eating, they face a practical limitation: they are strong at specifying

which determinants are associated with behaviour, but they are less explicit as process models of

how those determinants are integrated moment-to-moment to select actions under constraint. They rarely provide a computational account of how value, uncertainty, and environmental friction interact dynamically to suppress or amplify sustainable intentions in real settings (

Table 1).

Second, most of these frameworks retain a fundamentally individual-centric and linear view of behaviour. Behaviour is typically modelled as the endpoint of a causal chain starting from internal states (beliefs, attitudes). While these frameworks acknowledge environmental influence, they typically operationalise it as a static 'moderator' or 'barrier' to intention. This misses the causal reality: in an active inference system, the environment is not just a barrier to the intention; it is the generator of the precision that determines whether an action is selected at all. By treating context as a background variable, traditional models fail to capture how volatile food landscapes actively erode the reliability of sustainable intentions over time. For instance, while SCT formally recognises reciprocal causation, empirical applications frequently model one-way prediction of behaviour from internal predictors, ignoring how repeated actions reciprocally reshape the environment and subsequent preferences over time [

50].

Third, decision-making is frequently bifurcated in standard models, treating habits as ‘add-ons’ or competing systems. Standard dual-process accounts often frame sustainable diet gaps as a conflict between 'virtuous' Type 2 intentions and 'impulsive' Type 1 habits [

28]. This dualism obscures the unified computational process at play. The brain is not fighting itself; it is simply selecting the policy with the highest expected precision. What these models categorize as "mindless habit" or "failure of self-regulation" is often the rational prioritization of a high-certainty default in a high-uncertainty environment. Existing frameworks struggle to explain this because habit is often layered on top of intention-based models rather than integrated into a single dynamic system [

50,

51]. Consequently, feedback processes - where "eating well" reinforces the drive to do so - are often described informally rather than modelled explicitly as part of the system's dynamics [

50,

52].

By contrast, affordance theory shifts the unit of analysis from the individual to the relation. It challenges the assumption that “access” is an objective property of the environment (e.g., “is there a supermarket nearby?”). Instead, it starts from the premise that affordances depend jointly on environmental properties and the capabilities and states of the individual. [

13,

53,

54]. A supermarket stocked with lentils does not necessarily afford a sustainable meal to a parent who lacks the time or liquidity to risk a rejected dinner; in that context, the “cook lentils” policy is not a

viable affordance for that agent. In practical terms, this perspective forces us to stop asking “Is the food available?” and start asking “Is the action viable?” Or in active inference terms, does it have sufficient expected precision to be selected?

This shift from static barriers to dynamic affordances provides the necessary foundation for intervention. Rather than treating the environment as a passive stage where individuals must exert self-regulation, an affordance-based systems approach shows how context actively structures the decision space. This sets the stage for our use of active inference not just as a theory of brain function, but as an analytical lens for auditing and re-engineering food environments so that sustainable policies become the path of least resistance.

Aligning People and Places: an Active Inference Approach to Environmental Change

In an active inference framework, behaviour is the outcome of a generative model that agents hold about themselves in their environment [

14,

16]. This model acts as a probabilistic map: it encodes expectations about which states the agent should occupy (e.g., "fed," "solvent," "socially accepted") and which courses of action are likely to secure those states [

41,

55]. Behavioural policies, such as “buy ready meals” versus “cook from scratch”, are constantly evaluated in terms of their expected free energy: a trade-off between the value of the goal and the precision (reliability/effort) of achieving it [

37,

38,

42].

Crucially, the generative model is a model of the agent-in-context. What counts as a feasible behavioural policy depends entirely on the affordances the environment provides: the foods stocked, the prices set, and the time available [

13,

53,

56]. From this perspective, there are three routes to reducing "surprise" (prediction error) when reality diverges from preference [

41,

55]:

Perceptual Learning: Updating beliefs to accept the current reality (e.g., "I guess I don't care about sustainability"). This explains why some consumers disengage entirely.

Active Inference: Selecting actions to change personal state (e.g., "I will cook"). This represents the current dominant approach of relying on education and willpower. However, it frequently fails because it places an unsustainable cognitive burden on the individual to persistently overcome environmental friction.

Niche Construction: Modifying the environment itself so that preferred outcomes become easier to realise [

57,

58]. This shifts the burden from the individual to the system, ensuring the sustainable choice is the default.

While individuals can engage in micro-niche construction (e.g., meal prepping), they have limited scope for the systemic niche construction required to alter the reliability and computational cost of food environments - this is the primary function of policymakers [

58,

59,

60]. In this view, bodies such as Defra, the FSA, and OHID are not merely regulators monitoring compliance; they are niche constructors responsible for re-engineering the predictability of the food system [

57]. Their role is not just to ensure sustainable food is available, but to stabilize the affordance field - reducing the volatility and friction that make sustainable choices risky [

56,

61]. By doing so, they ensure that the policies that minimise expected surprise (financial shocks, wasted food, hunger) are aligned with, rather than antagonistic to, sustainable diets [

41,

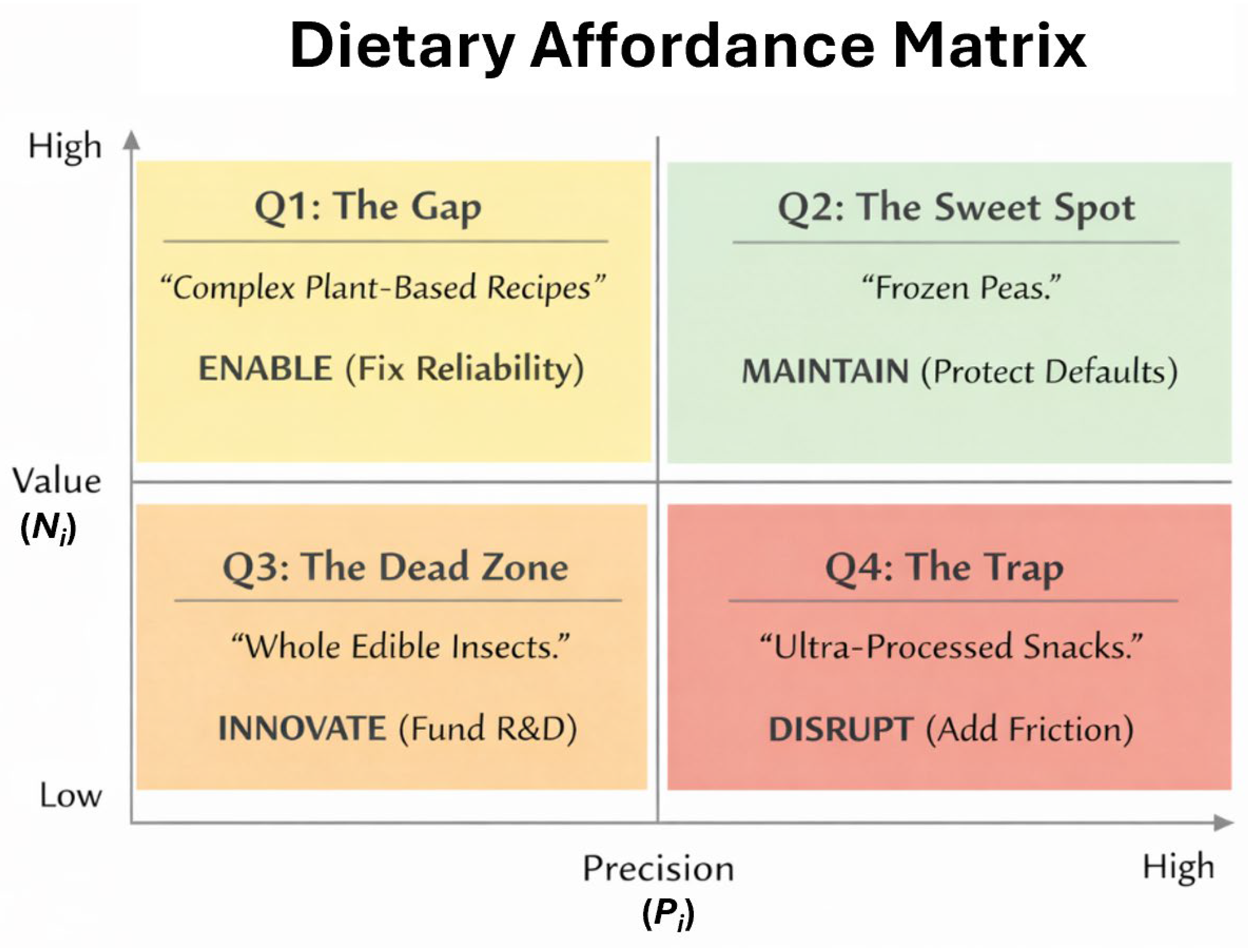

43]. To translate this theoretical shift into practice, we introduce the Dietary Precision Matrix (

Figure 3). This diagnostic tool allows policymakers to systematically audit the food environment, pinpointing exactly where low precision currently 'prunes' sustainable options from the consumer's feasible policy set before they can even be considered [

55].

By identifying the environment as the primary source of decision volatility, we expose the limitations of the status quo: an over-reliance on the second route (individual active inference) [

40]. Demanding that households under economic strain 'care more' about sustainability is effectively asking them to adopt a low-precision policy - one that incurs high metabolic and financial risk without altering the underlying constraints [

62]. It is neither ethical nor mathematically efficient to expect individuals to override high-precision survival priors (solvency, satiety) with abstract, high-variance intentions [

40,

41]. Instead, the goal is structural alignment: configuring retail geography, pricing, and infrastructure so that sustainable choices become the high-precision default [

57,

61]. When the environment acts as a scaffold by making the sustainable choice the safest, most predictable, and lowest-effort option, behaviour shifts not because the individual has “more self-regulation,” but because the expected free energy of the sustainable policy has been minimised [

41,

43]. Crucially, the dietary affordance framework advanced here does not merely advocate for niche construction in the abstract; it provides the mechanistic blueprint for how such environments should be constructed to align with the predictive nature of the human brain [

38,

57].

In the following sections, we apply this lens to the sharp end of the crisis: households navigating food insecurity and cost-of-living pressures. We identify concrete leverage points (including pricing, urban planning, and digital infrastructure) where precise interventions in the affordance field can trigger disproportionate shifts in behaviour. Moving beyond the static metaphor of 'barriers,' we demonstrate how leverage points function mechanistically: they alter the precision weighting of the environment, flipping the system’s path of least resistance from unsustainable habits to sustainable goals.

From Theory to Food Systems: Dietary Affordances Under Food Insecurity

The theoretical mechanics of active inference become starkly visible when applied to households navigating food insecurity and cost-of-living pressures. While it is sociologically obvious that poverty constrains choice, active inference reveals the computational mechanism behind this constraint. Here, socioeconomic variables are not merely external "barriers"; they are internalised as hard constraints on the feasible policy set that shape behaviour even when sustainable intentions remain strong.

To understand this as a generative process, consider the affordance field of a household operating under strict budget and time constraints [

63]. For such a consumer, the generative model prioritizes "avoiding hunger" and "maintaining financial solvency" as non-negotiable, high-precision priors. While the preference for sustainability may persist as a higher-level goal, it is effectively suppressed by the immediate urgency of these survival constraints. When this consumer evaluates the policy “buy fresh, sustainable ingredients,” the expected free energy is prohibitively high: the financial cost is volatile relative to the remaining budget, and the preparation time introduces outcome risk into a schedule already compressed by precarious employment or caregiving [

64].

By contrast, the policy “buy a processed ready meal” offers high enactment precision: the monetary cost is known at the point of purchase and the time and skill demands are minimal, making outcomes more reliable than many fresh-ingredient meals [

65]. The sensory outcome and immediate satiation are also highly predictable, reducing the risk of a failed evening meal under constraint [

66]. In active inference terms, when sustainable options carry greater financial and temporal uncertainty, they are effectively pruned from the feasible policy set; the system minimises expected surprise by selecting the lower-risk policy [

17,

41,

56].

Recent data from the United Kingdom Cost-of-Living Crisis makes these mechanics visible. Rising food and energy prices have compressed the feasible policy set, forcing households to trade-off between housing, utilities, and food [

67,

68]. In a Welsh national survey, approximately 20% of respondents reported eating less food and 12% reported eating more processed foods specifically in response to rising costs [

68]. Crucially, this shift occurred despite high reported concern for health and sustainability [

69]. This supports the active inference view: dietary behaviour adapted not because values changed, but because the affordance field shifted, making energy-dense, processed options the only policies capable of reliably minimizing the "surprise" of hunger within the new economic constraints [

68].

Inequality and the Contraction of the Policy Set

This framework clarifies how inequality reshapes the feasible set of action policies, helping to explain why certain groups (including lone-parent households, people with disabilities, and residents of areas with limited access to affordable healthy food (“food deserts”)) are disproportionately affected [

70,

71]. Standard accounts often assume that if a sustainable option is physically present (for example, stocked in a local shop), it is therefore ‘available’ to the consumer. An active inference perspective challenges this assumption: an option is only functionally available if it can be executed with sufficient reliability, given real constraints on time, money, mobility, fatigue, and competing demands. This distinction is captured by the affordance equation,

. Because precision

acts as a multiplier, small reductions in reliability under constraint can sharply diminish affordance strength, producing systematic divergence in observed behaviour even when stated goals and information are similar. These reliability penalties are not evenly distributed across populations.

For a household operating with a financial buffer, the policy "experiment with a new sustainable recipe" is a viable option. If the meal fails (spoilage, poor taste, rejection by children), the cost is trivial. However, for a household operating at the margins of solvency, that same outcome represents a critical prediction error: a waste of scarce liquidity and a failure to secure satiety [

63].

In this high-stakes context, decision-making narrows as scarcity taxes mental bandwidth and increases sensitivity to immediate risk [

72]. Sustainable options that require time, equipment, and tolerance of variable outcomes are more likely to be dropped from the feasible policy set because they carry greater expected uncertainty. Ultra-processed foods are not selected merely for “convenience”; they are selected because they are reliably executable: costs are predictable, preparation demands are low, and outcomes are consistent. Consistent with this account, food insecurity is associated with higher intake of ultra-processed foods, with proposed pathways including economic constraint, stress, and coping strategies that favour shelf-stable, ready-to-eat options [

73]. Thus, inequality does not only limit what consumers can buy; it limits the range of strategies they can risk.

Implications for Intervention

These patterns help to explain why policies focusing on information or "choice" have had limited impact [

74]. From an affordance perspective, interventions that attempt to strengthen intentions rely on the assumption that the barrier is psychological. In active inference terms, many “nudges” attempt to shift prior preferences (e.g., “eat sustainably”) while leaving the expected costs and risks of implementing those policies largely unchanged; policy selection therefore remains dominated by expected free energy under the current constraints [

17].

The Temporal Constraint: A Race Against Precision

Finally, this framework introduces a critical temporal dimension to intervention design. In active inference, learning (the updating of the generative model) is governed by the precision of existing beliefs (mathematically, the Kalman gain) [

76]. When a food environment or product is novel, priors are relatively imprecise and behaviour is more sensitive to external cues such as eco-labels or price promotions. With repetition, outcomes become predictable and priors gain precision. As a result, policies can become habitual and increasingly resistant to new information, effectively “locking in” behaviour even when subsequent educational appeals change stated preferences [

17].

This implies a "race against precision" for sustainable foods. Interventions must be deployed at the point of market entry when affordance fields shift and priors are destabilised. If sustainable options are introduced with "mediocre" precision, for example, plant-based alternatives that are expensive, unpredictable in texture, or hard to cook, consumers may rapidly form a resilient, negative prior that no future marketing campaign can unseat. A real market illustration of what happens when the first encounter doesn’t clear the viability threshold was the recent Nestle withdrawal of its plant-based Garden Gourmet and Wunda brands from sale in the UK in 2023, stating the products were “not viable” in current market conditions. The goal of niche construction, therefore, is not just to make sustainable options available, but to ensure their initial affordance is robust enough to seed a high-precision, sustainable habit before the window of plasticity closes.

Epistemic Value and the Initiation Problem

The temporal argument above also exposes a second barrier. Getting a person to try a sustainable option for the first time is often an exploration problem, not a persistence problem. In active inference, policy selection is guided by Expected Free Energy, and Expected Free Energy is not only about achieving preferred outcomes. It formally combines two components: a pragmatic drive to secure preferred outcomes by reducing expected risk, and an epistemic drive to reduce uncertainty by seeking information that resolves ambiguity [

41,

43]. This matters because novelty can be attractive in principle, but only when exploration is safe.

We can incorporate this directly into the dietary affordance account by making explicit that both value and precision evolve over time. For an option

, affordance strength at time

can be expressed as:

Here

captures the immediate goal value of the outcome (satiety, affordability, alignment with preferences and norms).

captures the temporary “information bonus” of trying something uncertain in order to find out what happens, and it is typically highest early in exposure when priors are imprecise.

captures the reliability of execution, meaning the probability that the option can be enacted without costly surprise (price spikes, stock-outs, time overruns, waste, rejection). As the option is repeated,

naturally decays because uncertainty is resolved, and the long-run fate of the behaviour depends on whether experience increases

enough for

to remain high under real-world constraint ambiguity [

41,

43]

This formulation sharpens the policy implication. Information-based campaigns implicitly assume that consumers will experiment with sustainable options and learn their value over time. Under constraint, however, epistemic value is down weighted because exploration is costly and risky, so novel sustainable options are not sampled, or are sampled once and rejected after a single failure. The design target is therefore twofold. Policy must first reduce the penalty for exploration so that initial sampling can occur without jeopardising satiety, time, or budget, and then it must engineer reliability so that repeated experience increases

and converts the option from a novel experiment into a low-risk default [

17].

A similar initiation dynamic is visible in digital choice architecture, where early friction teaches users which policy is safest to repeat, and later information has limited leverage once the default is automatised. Regulators introduced 'cookie banners' to empower choice (Type 2) but failed to account for the interaction cost. Users rapidly learned that 'Accept All' was the only high-precision policy to access content quickly [

77]. By the time regulators intervened to simplify rejection, the habitual reflex was already 'locked in.' Food policy risks repeating this error: if sustainable choices remain high friction during the critical window of habit formation, consumers will automate the 'unsustainable' choice to minimize metabolic effort, rendering later informational interventions ineffective.

Bridging the Intention–Behaviour Gap: Leverage Points in the Food System

To operationalise this shift from "informing individuals" to "reshaping environments," we draw on systems thinking to identify leverage points: places where relatively small changes in structures or signals can produce disproportionate shifts in the system’s behaviour [

67,

78].

Within our affordance framework, effective leverage points are interventions that increase affordance strength for a given option by maximising the synergy between pragmatic value and predictive precision . A structural change acts as a leverage point not merely by adding options, but by aligning these two dimensions. This ensures that sustainable choices are not just desirable (High Value) but structurally inevitable (High Precision).

Reframing Leverage: Why an Affordance Lens Matters

While fiscal and regulatory tools are well-established in policy discourse, an affordance-based approach alters how we understand their function. Traditional frameworks often treat interventions as competing forces against resistance (e.g., "How do we overcome barriers?"). By contrast, our framework identifies leverage points by fundamentally shifting the questions we ask about the food environment.

To operationalise this, we propose five key analytical shifts for policy design. These shifts move the focus from static measures of "access" to dynamic measures of "reliability" and "precision" (

Table 2).

Applying the Framework: Locating Leverage Points in Policy Domains

To demonstrate the practical utility of these analytical shifts, we examine three critical domains of food system intervention: fiscal policy, urban planning, and digital choice architecture.

In each domain, we move beyond the broad category to identify the specific mechanistic leverage point that active inference reveals. For fiscal policy, the leverage point shifts from

average price to price stability (variance). For urban planning, it shifts from

access to predictive reliability. For digital tools, it shifts from

education to default automation. By isolating these specific mechanisms, we show how current approaches often miss the target and how they can be re-engineered for efficacy. We summarise these shifts in

Table 3.

1. From Taxing Cost to Stabilizing Variance (Fiscal Policy)

Fiscal levers primarily operate on the expected financial cost of policy selection. In principle, instruments such as carbon taxes on high-emission foods (e.g., red meat) could reduce emissions [

3]. However, standard economic models assume that if the price of meat rises, consumers will switch "upward" to sustainable fresh ingredients.

Our framework predicts a different, riskier outcome - a "Precision substitution". To a brain where meat is a High-Precision Policy, it offers guaranteed satiety, familiar texture, and zero preparation risk. Fresh vegetables, by contrast, are a Low-Precision Policy: they carry a risk of spoilage, cooking failure, and family rejection. If a tax increases the cost of meat without altering the

precision of the alternatives, the agent will not switch to the "risky" fresh vegetables. Instead, they will switch to the next available high-precision policy: possibly cheaper, ultra-processed foods (UPF) [

86]. By their nature UPFs are predictable, calorie-dense, and ready-to-eat. Therefore, a carbon tax unaccompanied by measures to enhance the predictive precision of healthy sustainable options risks driving a precision substitution. Rather than adopting fresh produce, vulnerable consumers may retreat to high-reliability ultra-processed foods, minimizing financial risk at the cost of long-term health [

87].

This changes what we subsidise. The design implication is that we subsidise reliability, not just “health.” Many healthy-eating subsidies target raw, fresh produce (e.g., fruit-and-vegetable vouchers), but these schemes risk underperforming because they address financial cost while leaving computational cost unchanged: spoilage risk, preparation time, and outcome uncertainty remain borne by the household [

17,

80] . Consistent with this, constrained households tend to rely more on shelf-stable, ready-to-eat formats, including ultra-processed foods, because they minimise day-to-day risk and effort [

73]. An affordance-based approach therefore suggests targeting high-precision sustainable options (foods that bridge sustainability and reliability) such as frozen vegetables, tinned pulses, and minimally processed plant-based convenience foods. By reducing the cost of these

reliably executable formats, policy can create a viable “off-ramp” from meat that does not require households to gamble limited budgets on high-variance raw ingredients [

17].

2. From Physical Access to Predictive Reliability (Urban Planning)

While pricing targets financial cost, planning determines the physical effort and reliability required to access food. However, active inference challenges the traditional "food desert" focus on physical proximity. Standard theory assumes that if we place a healthy store within walking distance (reducing physical effort), consumption will follow. Our framework suggests that access is insufficient without predictive reliability [

17,

88].

Currently, "food swamps" dominate not just because fast food is nearby, but because it is a high-precision service: the "Golden Arches" signal guaranteed availability, consistent hours, and zero search cost. By contrast, sustainable food environments (e.g., farmers' markets, independent greengrocers) can be experienced as high variance, that is variable opening hours, seasonal stock fluctuations, and inconsistent quality [

89]. To a brain minimizing expected surprise, this lack of reliability marks the sustainable option as a "risky" policy, causing the agent to default to the high-precision certainty of the chain outlet regardless of distance.

This reframing alters the goal of intervention from "increasing access" to "increasing consistency." This logic is validated by a recent study by [

90], who optimized a university canteen menu to reduce its carbon footprint by 30%. Crucially, they achieved this by reconfiguring the menu options so that sustainable dishes were consistently paired with popular items. The intervention was successful because it respected the students' need for precision: the study noted that the "most preferred dish" was always available as a fallback, ensuring that the sustainable choice became the path of least resistance without removing the agent's sense of security. Because the shift generated no metabolic or hedonic "surprise", students enacted the sustainable policy habitually.

Similarly, this implies that zoning regulations shouldn't just restrict fast food locations [

91] but must actively degrade their sensory precision. If a fast-food outlet is the most visually salient feature of a daily commute [

92], the brain builds a strong prior that "food is here." Zoning interventions that restrict signage dilute this prior [

93]. Furthermore, when introducing new sustainable infrastructure, planners must balance novelty with reliability. While novelty (e.g., a pop-up market) is effective for updating a prior (generating the prediction error needed to grab attention) it is insufficient for maintaining a habit. For an agent under constraint, operational reliability (consistent, "boring" availability) is the decisive factor that allows a new option to transition from a "novel experiment" to a "low-risk daily default

3. From Information to Automated Defaults (Digital Architecture)

Finally, the immediate "choice architecture" of retail and digital environments profoundly shapes which policies are selected under time pressure. In the digital realm, algorithms that default to past purchases act as precision-preservers, solidifying existing habits and locking users into historical patterns even when intentions have changed [

94].

From an affordance perspective, these interfaces act as "technologies of entrapment." Interventions that alter defaults (such as prompting sustainable swaps at checkout or reshaping app interfaces) work by offloading the computational cost of finding sustainable options onto the environment.

While this approach resembles "choice architecture" [

95], the theoretical premise differs. Behavioral economics typically frames reliance on defaults as a product of inertia or

status quo bias, that is, a cognitive flaw to be exploited. Active inference reframes this as computational efficiency. For an energy-constrained brain, evaluating a new menu incurs a high metabolic "interaction cost." Adhering to the default is therefore not a sign of laziness, but a rational strategy to minimize expected free energy. In this view, setting sustainable defaults does not "trick" the user; it subsidizes the cognitive cost of the sustainable choice.

This theoretical shift dictates a different design standard: while a 'nudge' might succeed temporarily by exploiting inattention, an active inference approach requires that the default option minimises post-choice surprise; if the default produces repeated prediction error (unexpected cost or poor satiety), the agent updates its model and devalues that policy as unreliable [

17,

41]. Thus, sustainable defaults must not only be easy to select; they must be engineered to be the most reliable, ‘surprise-free’ experience in the system.

General Discussion: From "Overcoming Barriers" to "Engineering Precision"

Existing frameworks have been invaluable in identifying the determinants of dietary choice - highlighting the roles of attitude, capability, and opportunity. However, they have largely struggled to explain the persistent gap between what people intend to eat and what they actually consume, often attributing the shortfall to failures of individual self-regulation.

The active inference approach offers a fundamental reframe. It suggests that the intention–behaviour gap is not a failure of will, but a success of optimization. In volatile, time-constrained environments, the brain rationally prioritizes policies that minimize expected surprise by choosing the "unhealthy" options that offer guaranteed satiety, fixed prices, and zero preparation risk over sustainable options that are perceived as volatile and high-effort.

Operationalising the Framework: Diagnosing Policy Mismatches

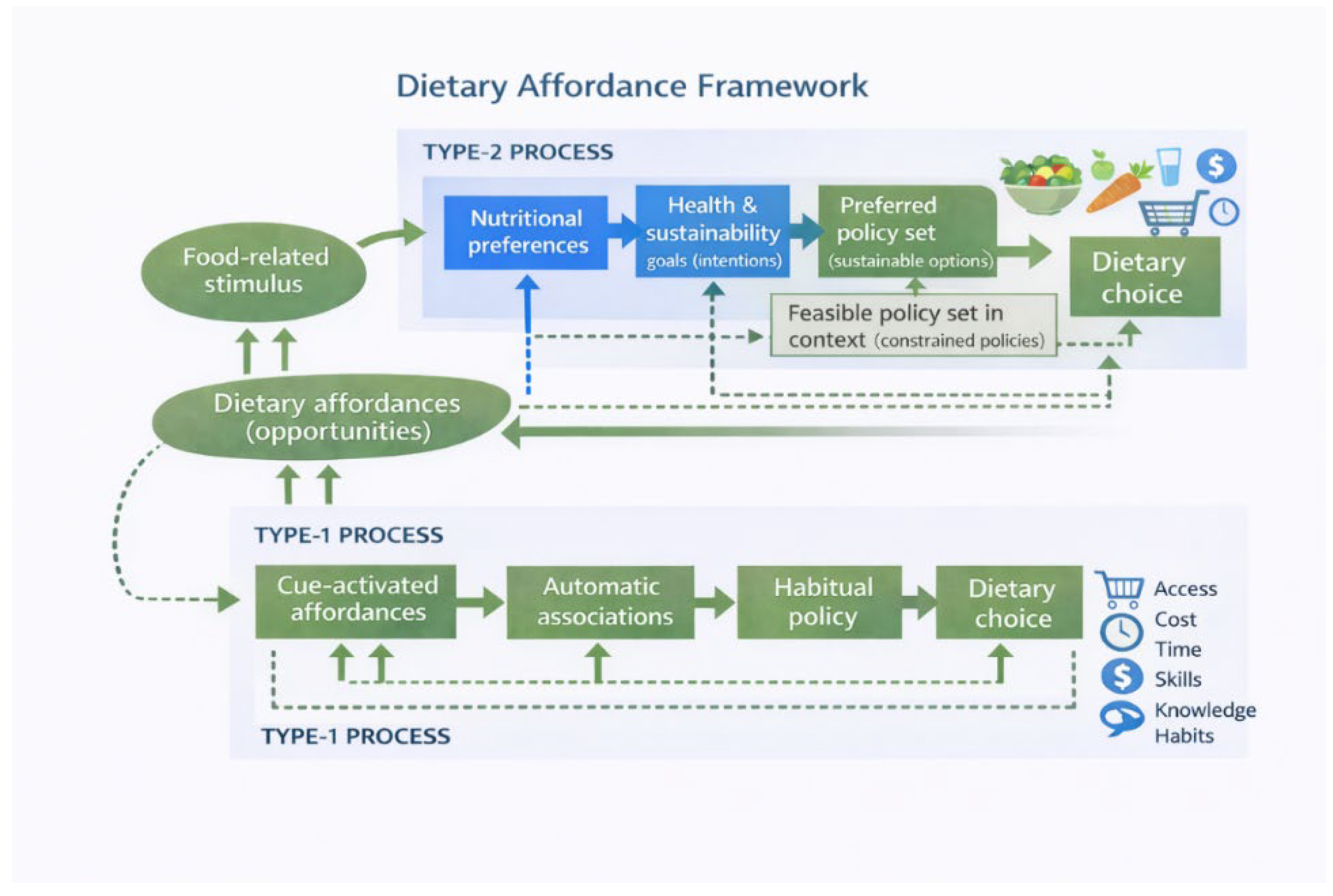

To apply this framework in practice, we introduce the Dietary Precision Matrix (

Figure 3) as a heuristic for intervention design. Currently, policymakers often apply a “blanket” approach by using information and education (attempting to increase normative value,

) without addressing environmental reliability (precision,

). The matrix clarifies why this often underperforms: different quadrants require fundamentally different mechanisms of change. Our framework therefore highlights two geometric pathways for effective intervention. (1) The Horizontal Shift (Stabilisation): stabilising aspirational foods by moving them from Q1 to Q2, by increasing the reliability of sustainable options (for example through processing, infrastructure, or targeted subsidies) so they become viable habits. (2) The Vertical Shift (Stealth): improving the sustainability of existing habits by moving them from Q4 to Q2. As demonstrated by the menu optimisation in [

90]Flynn et al. (2025), this is a “stealth” intervention that improves normative value without requiring the consumer to sacrifice precision.

The tool functions as a diagnostic coordinate system. When evaluating a specific food item or behaviour, the policymaker locates it within the matrix to identify the appropriate policy imperative, as follows. For foods in Q1 (The Gap), the barrier is not motivation but reliability; campaigns focusing on education are therefore unlikely to be effective on their own. The imperative is to ENABLE access by reducing friction (for example through pre-preparation infrastructure), not merely lowering the price of raw ingredients. For foods in Q4 (The Trap), the primary driver is automaticity (high precision) rather than alignment with health goals. Reward processes can dissociate into ‘liking’ (hedonic enjoyment) and ‘wanting’ (cue-triggered incentive salience) [

96,

97], such that an option can be repeatedly selected even when it is not strongly enjoyed. Accordingly, our pragmatic value term

should be understood as motivational pull in context (closer to ‘wanting’ than ‘liking’), which high precision

can readily translate into habitual selection [

14,

42]. Appealing to ‘personal choice’ is therefore ineffective. The imperative is to DISRUPT the behaviour by introducing friction (for example zoning restrictions) that degrades the predictive precision of the unhealthy option. Crucially, for items in Q3 (The Dead Zone), the matrix warns against premature deployment. Policies that attempt to subsidise low-value, low-precision options (for example whole insects) are unlikely to compete with the hyper-reliable mechanics of incumbents in Q4. These products require INNOVATION (R&D) to build basic reliability before they can enter the competition.

By mapping interventions to the correct quadrant, policymakers can avoid the “Diagonal Fallacy”: the costly error of asking consumers to trade high-precision habits for low-precision aspirations without adequate structural support to ensure they land in Q2. It also reduces the risk of “Precision Substitution”, where a tax on meat (Q4) without a viable Q2 alternative causes consumer to slide sideways to another high precision but unsustainable option (for example ultra-processed foods), rather than making the intended leap to healthy sustainable foods.

The matrix maps food options based on two axes derived from Active Inference: Normative value (Y-axis: health/sustainability) and Precision (X-axis: reliability/ease). Q1: The Gap (High Value, Low Precision). Aspirational foods (e.g., complex recipes) that fail due to high cognitive/time costs. Policy: ENABLE (Fix Reliability). Q2: The Sweet Spot (High Value, High Precision). Sustainable habits (e.g., frozen peas). Policy: MAINTAIN (Protect Defaults). Q3: The Dead Zone (Low Value, Low Precision). Failed products. Policy: INNOVATE (Fund R&D). Q4: The Trap (Low Value, High Precision). Unsustainable automatic habits (e.g., UPFs). Policy: DISRUPT (Add Friction). Note: The matrix plots normative value

(health/sustainability) against predictive precision

(reliability/ease). Behaviour is governed by affordance strength

(Aᵢ = Vᵢ × Pᵢ), where Vᵢ is

pragmatic value in context (including cue-driven motivational pull). Because ‘wanting’ can diverge from ‘liking’ [

96,

97], high-precision options can persist as habits even when reported enjoyment is modest. Thus, action can persist in Q4 because high precision supports habitual selection even when normative value is low. Sustainable behaviour is most reliably sustained in Q2, where normative value and precision are both high.

Future Directions: Operationalising the Framework

While this paper has focused on theoretical and policy implications, operationalising these constructs is the critical next step. We propose a practical measurement target. The affordance strength of an option

in context

can be operationalised as

, where

is pragmatic value (how desirable the option is in the moment) and

is predictive precision (how reliably it can be enacted without costly surprise). The methodological shift from “access” to “precision” follows directly from this equation. Conventional metrics often approximate

using knowledge, attitudes, stated preference, or mean price. The new metrics quantify

by measuring volatility, failure rates, and the reliability of fallback paths. This makes dietary affordance empirically tractable because

can be estimated from observed instability in the environment and then combined with measures of

to predict when

will be high enough for a sustainable policy to become a stable default [

17,

41].

One immediate example is pricing. Instead of asking whether sustainable options are cheaper or more expensive on average, which is a mean-cost metric that often fails to capture risk, we would quantify price volatility and promotion instability as components of

. This includes week-to-week variance in staple prices, the frequency of short-lived discounts, and the probability that a “budgeted” sustainable basket becomes unaffordable within a pay cycle. This matters because agents minimising expected free energy are sensitive to uncertainty and downside risk, not just mean costs [

41] and food price volatility is a recognised driver of welfare risk [

79].

A second example is operational reliability. Rather than treating sustainable food outlets (e.g., farmers’ markets, independent greengrocers) as simply “present” or “absent,” we would measure the variance in opening hours, stock continuity, and fallback availability as additional components of

. This can be operationalised as how often the sustainable option is open when the person is free, how often key items are out of stock, and what the lowest-friction substitute is when the plan fails. These reliability measures can be combined with geospatial analyses that map “affordance fields” not just by distance, but by exposure across daily activity spaces (home–work–commute) and the density of high-precision cues (e.g., takeaway outlet exposure along routes, signage-rich corridors) [

92].

A third example is temporal constraint at the individual level. Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) can operationalise short-term fluctuations that modulate

in practice. For example, stress, fatigue, and time pressure can be linked to the moments when agents revert to habitual policies [

98,

99]. In combination, these methods allow direct tests of the affordance equation. Interventions should succeed when they increase

(reliability) enough that

crosses a threshold, even if

(stated motivation) changes only modestly uncertainty [

17].

Across these examples, the empirical goal is to estimate how much reliability (predictive precision) is required for a sustainable policy to become a stable default, consistent with active inference accounts of policy selection and learning under uncertainty [

17].

Conclusion: Designing for the Path of Least Resistance

Ultimately, this paper has moved beyond simply describing the "green intention–behaviour gap" to providing a mechanistic explanation for it. By framing sustainable eating as an active inference problem, we have demonstrated that the discrepancy between what people intend to do and what they actually do is not a failure of individual self-regulation, but a predictable success of optimization. We have challenged the deficit-based view that characterizes consumers as impulsive or unmotivated, reframing the choice of energy-dense, unsustainable foods as a rational prioritization of high-precision policies in a volatile environment.

At the heart of this shift is our new construct: dietary affordances. We define dietary affordances as the set of food-related actions that are realistically available and achievable for an individual in a specific context. Unlike traditional measures of "access," which treat the environment as a static set of options, an affordance is relational: it emerges from the dynamic interaction between personal factors such as income, time, and skills, and environmental factors such as price, layout, and social norms. We formalize this relationship through the synergy equation, where the affordance strength of option is the product of its pragmatic value and its predictive precision : . This equation clarifies the logic of the intention–behaviour gap: if precision (the reliability with which an option can be enacted) approaches zero due to complexity or volatility, affordance strength approaches zero, regardless of how much the individual values the goal.

Using active inference to close the gap shifts the focus of interventions from "motivating individuals" to "engineering precision". The brain selects "policies" (action sequences) that minimize expected surprise and risk. In current food systems, unsustainable habits are often the only high-precision policies available; they offer guaranteed satiety and fixed costs with zero preparation risk. By contrast, sustainable intentions often function as low-precision priors. That is abstract goals that are perceived as expensive, time-consuming, or carrying a high risk of failure.

This shift changes the very questions we ask to guide policy. Instead of asking a static, resource-based question such as "Is healthy food available?", we must ask a dynamic, computational question: "Is the sustainable action viable and low-risk across busy weeks and stock-outs?". Instead of asking "Do people have enough information?", we ask "Does the environment sufficiently subsidize the cognitive and metabolic interaction cost of choosing the sustainable option?". Finally, instead of asking "How do we change individual preferences?", we ask "How do we increase environmental reliability and stability to force certainty for the consumer?".

We cannot "inform" our way out of a structural crisis. As long as sustainable diets remain low-precision policies (expensive, time-consuming, and risky) the brain will continue to default to the high-precision safety of processed foods. Closing the gap requires a systematic reshaping of the affordance field: using pricing, planning, and technology not just to make sustainable food available, but to make it the most reliable, predictable, and automatic solution to the everyday problem of being fed.

Policymakers must act as niche constructors, re-engineering the predictability of the food system so that sustainable choices become the "path of least resistance". We must move beyond asking "Is healthy food available?" to asking: "Does this intervention sufficiently reduce the expected risk and computational cost of the sustainable option to make it the dominant, high-precision policy?

To bridge the gap, we must identify leverage points that specifically target predictive precision (the reliability with which an option can be enacted) rather than focusing solely on pragmatic value . This exploits the non-linear synergy implied by the affordance equation, whereby small increases in reliability can produce disproportionate shifts in behaviour. Practical leverage points include reducing volatility through fiscal policy (for example, stabilising prices of key staples), designing for operational consistency in urban planning (for example, predictable access and provision), and lowering cognitive costs through digital choice architecture (for example, simplified defaults, planning supports, and decision aids).

Ultimately, a food system that relies on individual executive control to mitigate a climate crisis is a system designed to fail. By aligning environmental affordances with the brain’s fundamental drive to minimize uncertainty, we can ensure that sustainable habits are selected not through the exhausting effort of self-regulation, but as the natural, high-precision outcome of a successfully optimized system.

Funding

AM was supported by an Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) studentship. The research received no other specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT Statement

HY.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AM.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. AG.: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AB.: Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Swansea University for supporting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Crippa, M. et al. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food 2, 198-209 (2021). [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, O., Jacobs, N. & Clément, C. A ‘Common Food Policy’ for Europe: How governance reforms can spark a shift to healthy diets and sustainable food systems. Food Policy 96, 101849 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M. et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 562, 519-525 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Willett, W. et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet 393, 447-492 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J. et al. The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable, and just food systems. The Lancet (2025).

- O'Keefe, L., McLachlan, C., Gough, C., Mander, S. & Bows-Larkin, A. Consumer responses to a future UK food system. British Food Journal 118, 412-428 (2016). [CrossRef]

- ElHaffar, G., Durif, F. & Dubé, L. Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production 275, 122556 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P. Intention—Behavior Relations: A Conceptual and Empirical Review. European Review of Social Psychology 12, 1-36 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Groening, C., Sarkis, J. & Zhu, Q. Green marketing consumer-level theory review: A compendium of applied theories and further research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production 172, 1848-1866 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Frank, P. & Brock, C. Bridging the intention–behavior gap among organic grocery customers: The crucial role of point-of-sale information. Psychology & Marketing 35, 586-602 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y. & Rahman, Z. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. International Strategic Management Review 3, 128-143 (2015). [CrossRef]