Submitted:

30 December 2025

Posted:

31 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

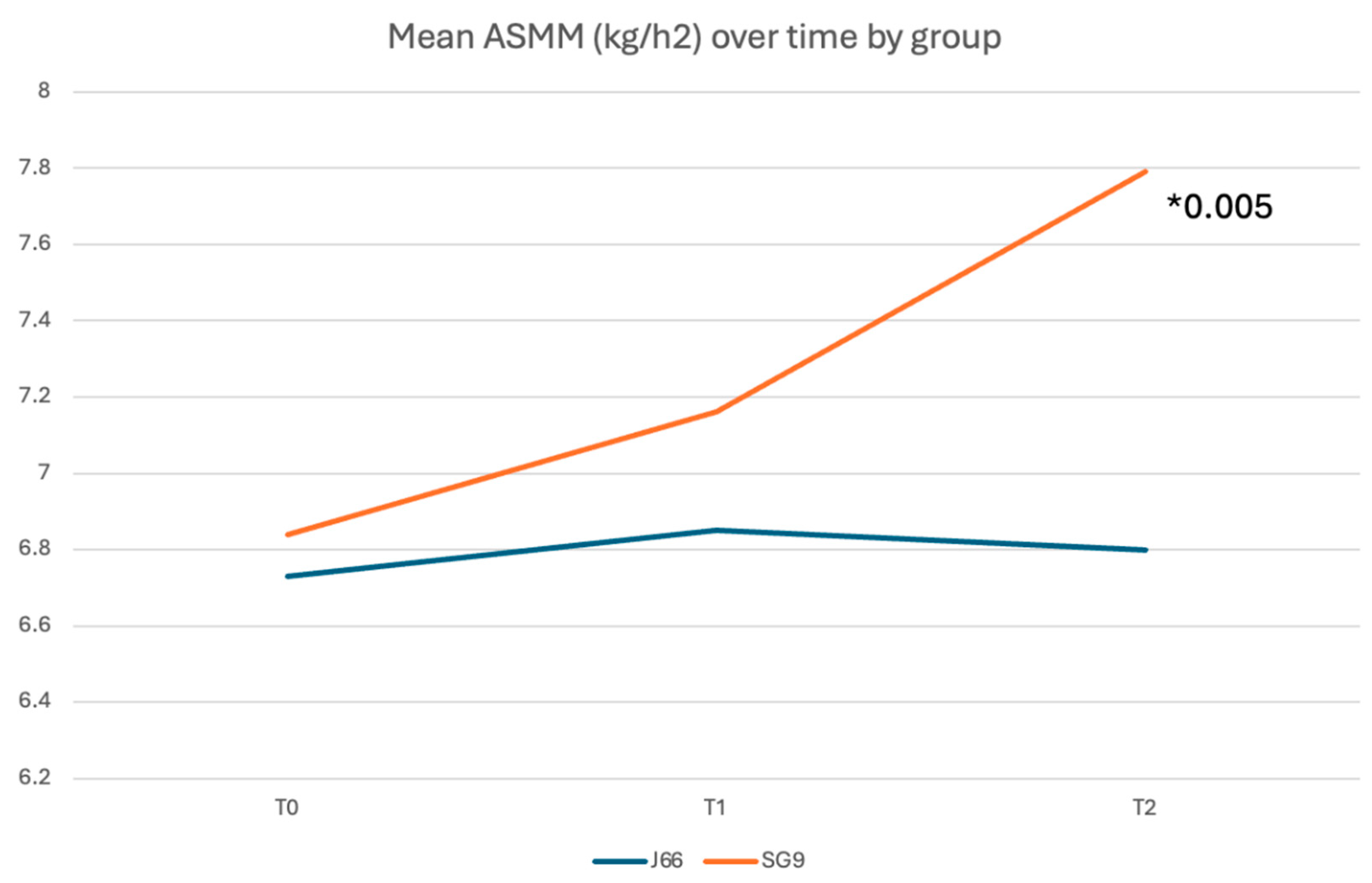

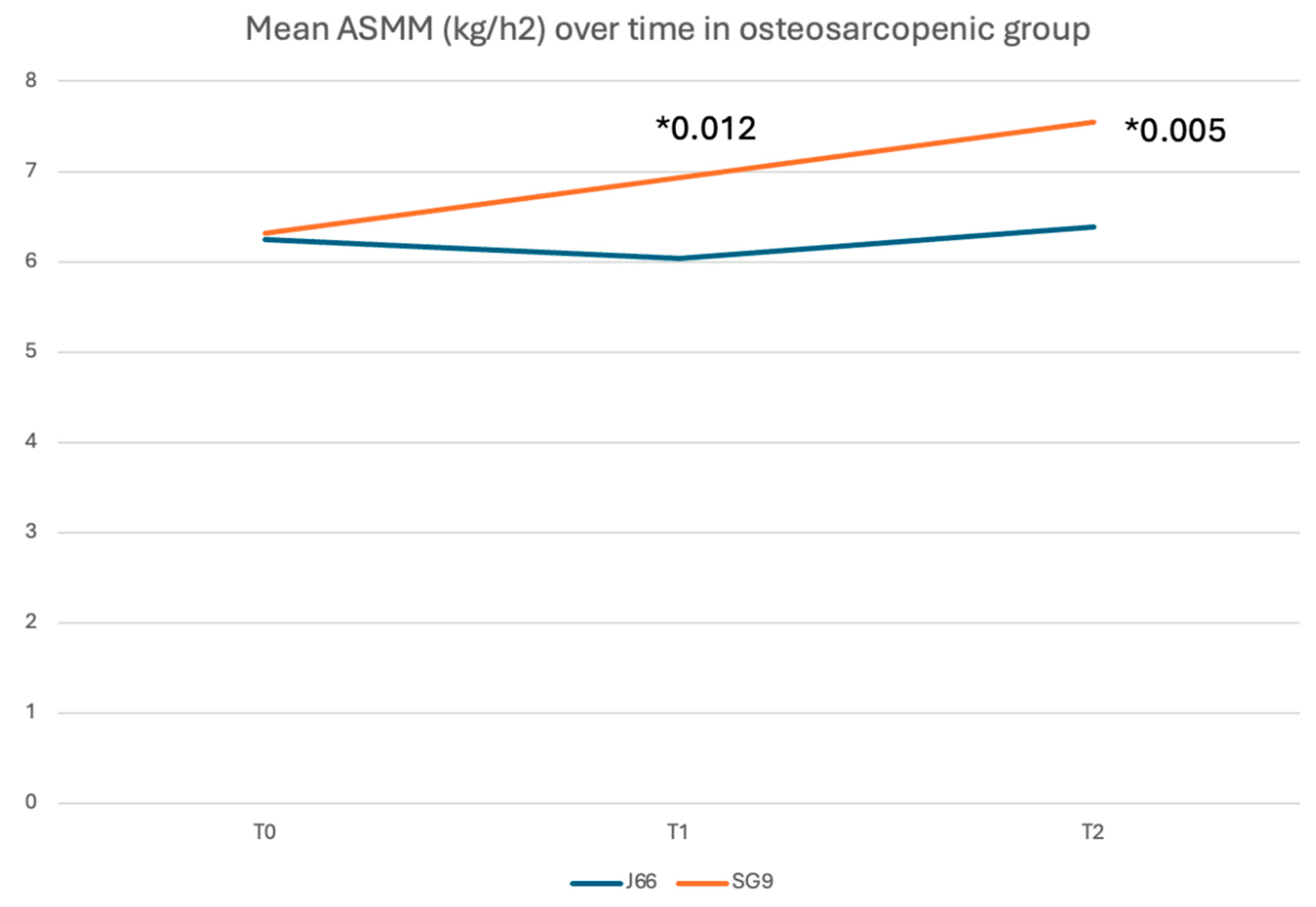

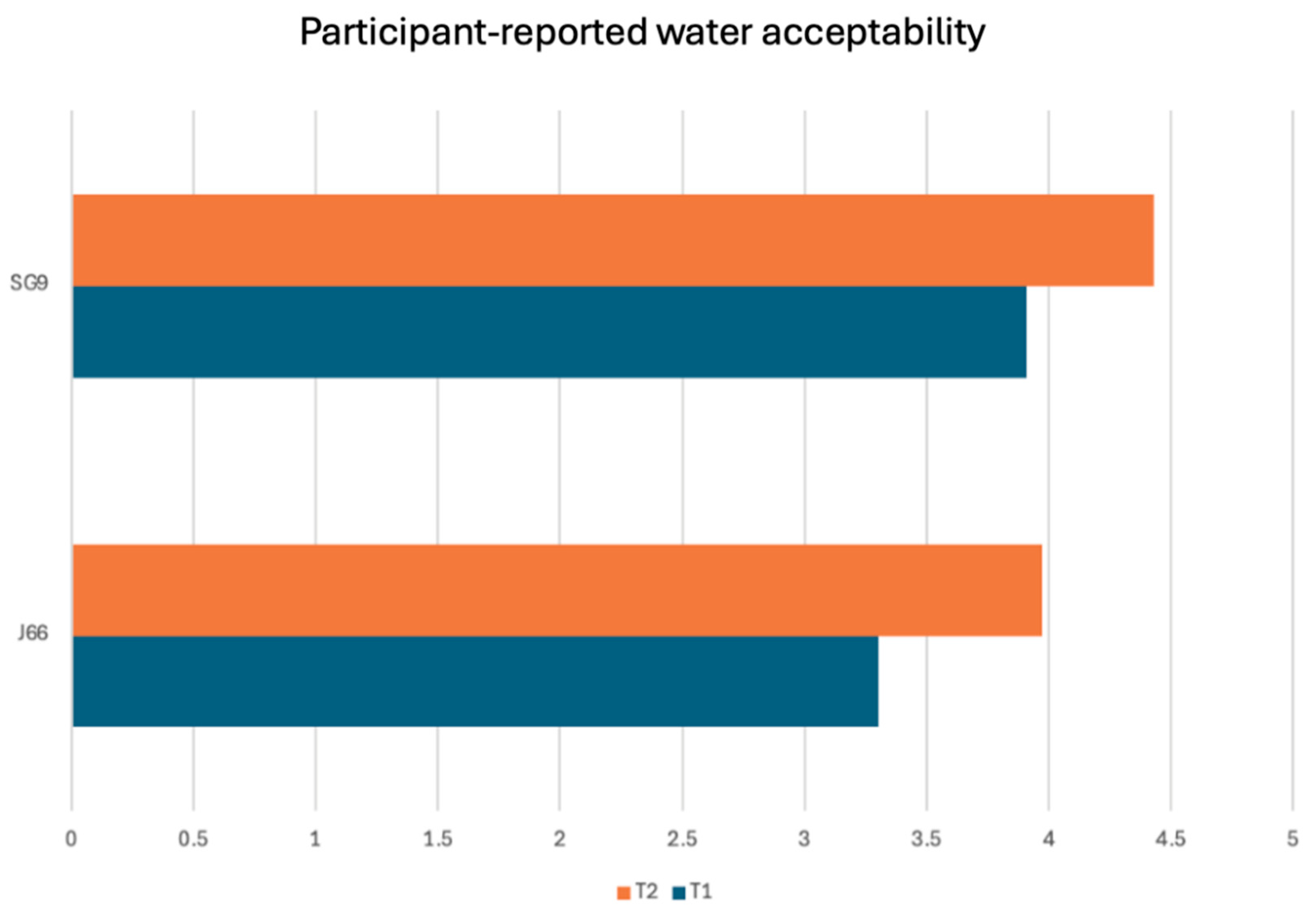

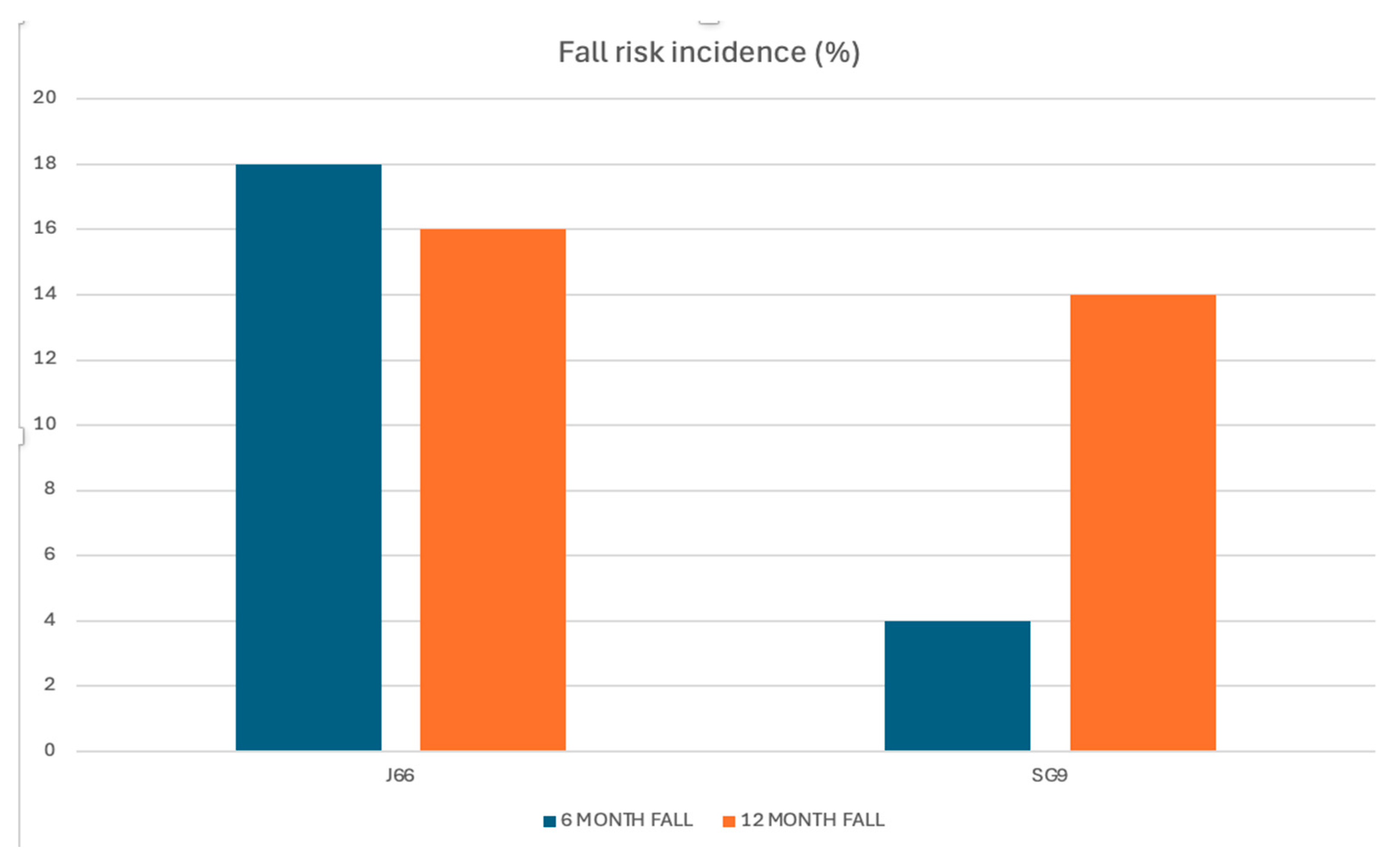

Background/Objectives: Calcium and magnesium are essential minerals involved in neuromuscular function, bone metabolism, and fall prevention. Deficiency of these minerals contributes to musculoskeletal fragility, including osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and falls. While dairy products are the traditional source of dietary calcium, mineral waters naturally rich in calcium and magnesium offer a highly bioavailable alternative. This study evaluated the efficacy of daily intake of a naturally calcium‑ and magnesium‑rich mineral water compared with low-mineral water on fall risk, muscle mass, and muscle function in adults aged ≥50 years, with or without osteosarcopenia. Methods: In this 12‑month, randomized, double‑blind, controlled trial, 98 participants were assigned to consume 1 L/day of either SG9 (mineral water with high calcium and magnesium content) or J66 (low-mineral water). Outcomes included incidence of falls (primary endpoint), appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASMM), muscle strength, physical performance, biochemical markers, and patient-reported measures. Assessments were performed at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months following CONSORT guidelines. Results: Ninety-eight participants (mean age ~63 years) were randomized and completed the 12-month follow-up. At 6 months, the incidence of falls was significantly lower in the SG9 group compared with the J66 group (relative risk reduction 82%; RR = 0.18, 95% CI 0.04–0.88; p < 0.05), whereas no significant between-group difference was observed at 12 months. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass indexed to height (ASMM/h²) was significantly higher in the SG9 group at 12 months (p = 0.005). In participants with osteosarcopenia, SG9 intake was associated with a consistent improvement in ASMM/h² at 6 and 12 months (p = 0.012 and p = 0.005, respectively). No significant between-group differences were detected in physical performance scores, biochemical markers, or quality-of-life measures. Conclusions: Daily consumption of calcium- and magnesium rich mineral water reduced fall risk and improved muscle mass in adults over 50 years, with or without osteosarcopenia. These findings support the role of calcium- and magnesium-rich mineral water as a complementary nutritional strategy for musculoskeletal health and fragility prevention.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vannucci, L.; Fossi, C.; Quattrini, S.; Guasti, L.; Pampaloni, B.; Gronchi, G.; Giusti, F.; Romagnoli, C.; Cianferotti, L.; Marcucci, G.; Brandi, M. L. Calcium Intake in Bone Health: A Focus on Calcium-Rich Mineral Waters. Nutrients 2018, 10(12), 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldurthy, V.; Wei, R.; Oz, L.; et al. Vitamin D, calcium homeostasis and aging. Bone Res 2016, 4, 16041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goltzman, D; Mannstadt, M; Marcocci, C. Physiology of the Calcium-Parathyroid Hormone-Vitamin D Axis. Front Horm Res. 2018, 50, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima, G; Dzupina, A; B Alhmadi, H; Magomedova, A; Siddiqui, Z; Mehdi, A; Hadi, N. Magnesium Matters: A Comprehensive Review of Its Vital Role in Health and Diseases. Cureus 2024, 16(10), e71392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dominguez, LJ; Mérida, DM; Donat-Vargas, C; Banegas, JR; Veronese, N; Barbagallo, M; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F; Guallar-Castillón, P. Higher Magnesium Intake Is Associated with a Lower Risk of Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc.;Epub 2025, 26(1), 105335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

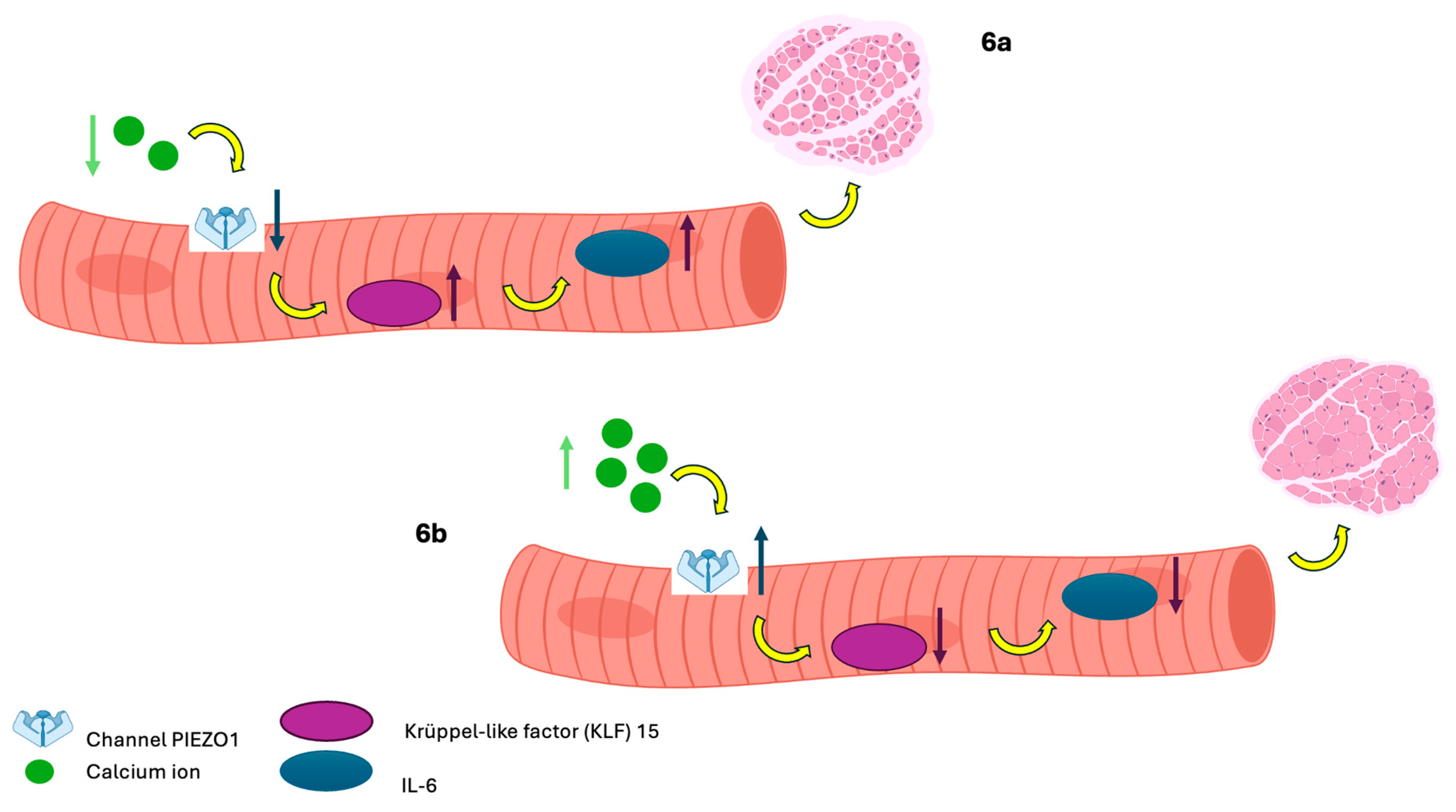

- Pietropaolo, G; Castiglioni, S; Maier, JA; Wolf, FI; Trapani, V. Magnesium Preserves Calcium Homeostasis and Contributes to Protect Myotubes from Inflammation-Induced Damage. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26(20), 9912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kanis, JA; McCloskey, EV; Johansson, H.; Oden, A.; Melton, L.J., 3rd; Khaltaev, N. A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone 2008, 42(3), 467–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, AJ; Bahat, G; Bauer, J; et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48(1), 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clynes, MA; Gregson, CL; Bruyère, O; Cooper, C; Dennison, EM. Osteosarcopenia: where osteoporosis and sarcopenia collide. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021, 60(2), 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, BM; Eslick, GD; Nowson, C; Smith, C; Bensoussan, A. Use of calcium or calcium in combination with vitamin D supplementation to prevent fractures and bone loss in people aged 50 years and older: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2007, 370, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolland, MJ; Leung, W; Tai, V; et al. Calcium intake and risk of fracture: systematic review. BMJ 2015, 351, h4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabit, H; Barry, M; Sreenan, S; Smith, D. Proximal myopathy in lacto-vegetarian Asian patients responding to Vitamin D and calcium supplement therapy - two case reports and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 2011, 5, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, JK; Cao, S; Cladis, DP; Weaver, CM. Lactose Intolerance and Bone Health: The Challenge of Ensuring Adequate Calcium Intake. Nutrients 2019, 11(4), 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, A; Liguori, S; Paoletta, M; Migliaccio, S; Toro, G; Gimigliano, F; Iolascon, G. Bone fragility during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of macro- and micronutrients. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2023, 15, 1759720X231158200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matković, V; Kostial, K; Simonović, I; Buzina, R; Brodarec, A; Nordin, BE. Bone status and fracture rates in two regions of Yugoslavia. Am J Clin Nutr 1979, 32(3), 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cepollaro, C; Orlandi, G; Gonnelli, S; Ferrucci, G; Arditti, JC; Borracelli, D; Toti, E; Gennari, C. Effect of calcium supplementation as a high-calcium mineral water on bone loss in early postmenopausal women. Calcif Tissue Int. 1996, 59(4), 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S; Chan, AW; Collins, GS; Hróbjartsson, A; Moher, D; Schulz, KF; Tunn, R; Aggarwal, R; Berkwits, M; Berlin, JA; Bhandari, N; Butcher, NJ; Campbell, MK; Chidebe, RCW; Elbourne, D; Farmer, A; Fergusson, DA; Golub, RM; Goodman, SN; Hoffmann, TC; Ioannidis, JPA; Kahan, BC; Knowles, RL; Lamb, SE; Lewis, S; Loder, E; Offringa, M; Ravaud, P; Richards, DP; Rockhold, FW; Schriger, DL; Siegfried, NL; Staniszewska, S; Taylor, RS; Thabane, L; Torgerson, D; Vohra, S; White, IR; Boutron, I. CONSORT 2025 statement: updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ 2025, 389, e081123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iolascon, G; de Sire, A; Calafiore, D; Benedetti, MG; Cisari, C; Letizia Mauro, G; Migliaccio, S; Nuti, R; Resmini, G; Gonnelli, S; Moretti, A. Multifactorial Assessment of Risk of Falling in 753 Post-Menopausal Women: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study by the Italian Group for the Study of Metabolic Bone Diseases. Clin Interv Aging 2020, 15, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Asano, K; Kabasawa, K; Takachi, R; Sawada, N; Tsugane, S; Ito, Y; Narita, I; Nakamura, K; Tanaka, J. Association of dietary calcium intake with risk of falls in community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults. J Nutr Health Aging 2025, 29(3), 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, S; Moretti, A; Paoletta, M; Gimigliano, F; Iolascon, G. Role of Magnesium in Skeletal Muscle Health and Neuromuscular Diseases: A Scoping Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25(20), 11220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moretti, A. What is the role of magnesium for skeletal muscle cramps? A Cochrane Review summary with commentary. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2021, 21(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vannucci, L; Fossi, C; Quattrini, S; Guasti, L; Pampaloni, B; Gronchi, G; Giusti, F; Romagnoli, C; Cianferotti, L; Marcucci, G; Brandi, ML. Calcium Intake in Bone Health: A Focus on Calcium-Rich Mineral Waters. Nutrients 2018, 10(12), 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, I; Greupner, T; Hahn, A. Magnesium bioavailability from mineral waters with different mineralization levels in comparison to bread and a supplement. Food Nutr Res 2017, 61(1), 1384686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Canfora, I; Tarantino, N; Pierno, S. Metabolic Pathways and Ion Channels Involved in Skeletal Muscle Atrophy: A Starting Point for Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Cells 2022, 11(16), 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polito, A; Barnaba, L; Ciarapica, D; Azzini, E. Osteosarcopenia: A Narrative Review on Clinical Studies. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23(10), 5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, C; Brandi, ML. Muscle Physiopathology in Parathyroid Hormone Disorders. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 764346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | J66 Water (N = 48) | SG9 Water (N = 50) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.08 ± 6.61 | 62.96 ± 8.10 | 0.424 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 24.52 ± 3.71 | 26.23 ± 4.69 | 0.065 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.77 ± 0.16 | 0.77 ± 0.12 | 0.927 |

| ALT (U/L) | 18.40 ± 7.80 | 19.38 ± 8.34 | 0.456 |

| AST (U/L) | 21.42 ± 4.65 | 21.76 ± 6.32 | 0.628 |

| Magnesium (mEq/L) | 2.01 ± 0.17 | 2.03 ± 0.24 | 0.896 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 3.45 ± 0.47 | 3.40 ± 0.43 | 0.559 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.45 ± 0.45 | 9.50 ± 0.44 | 0.889 |

| Total ALP (U/L) | 72.35 ± 23.83 | 75.08 ± 18.96 | 0.463 |

| 25OH-Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 32.02 ± 10.15 | 31.87 ± 10.82 | 0.907 |

| bALP (%) | 11.85 ± 4.94 | 12.80 ± 8.64 | 0.710 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 33.66 ± 11.99 | 34.56 ± 15.11 | 0.930 |

| Magnesium (urinary, mEq/24h) | 8.05 ± 3.66 | 8.36 ± 4.63 | 0.970 |

| Phosphate (urinary, mg/24h) | 596.81 ± 248.28 | 645.62 ± 323.46 | 0.409 |

| Calcium (urinary, mg/24h) | 164.37 ± 95.99 | 165.86 ± 116.43 | 0.802 |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | 87.05 ± 25.98 | 95.56 ± 52.22 | 0.947 |

| TNF-ALFA | 44.88 ± 70.17 | 44.06 ± 124.5 | 0.265 |

| P3NP | 10.59 ± 3.30 | 10.31 ± 2.72 | 0.594 |

| Sclerostin | 74.21 ± 50.53 | 67.05 ± 45.99 | 0.518 |

| Leptin | 12.25 ± 11.00 | 17.00 ± 18.62 | 0.593 |

| CTX | 0.21 ± 0.17 | 0.24 ± 0.29 | 0.657 |

| Irisin | 140.83 ± 38.5 | 137.99 ± 39.89 | 0.341 |

| P1NP (µg/L) | 544.36 ± 258.24 | 503.31 ± 235.29 | 0.334 |

| CIRS Severity Index | 1.37 ± 0.24 | 1.33 ± 0.24 | 0.226 |

| CIRS Comorbidity Index | 2.0 (0–6) | 1.0 (0–6) | 0.601 |

| CIRS Total Score | 5 (0–13) | 4 (0–13) | 0.110 |

| EuroQoL-5D Index | 0.99 ± 0.09 | 0.97 ± 0.10 | 0.110 |

| EuroQoL-5D (VAS) | 70.52 ± 13.50 | 72.80 ± 13.75 | 0.527 |

| SPPB Total Score | 7.0 (1–11) | 7.0 (2–12) | 0.173 |

| SPPB Balance | 3.0 (0–4) | 4.0 (0–4) | 0.155 |

| SPPB Gait Speed | 2.0 (1–4) | 2.0 (1–4) | 0.178 |

| SPPB Sit-to-Stand | 2.0 (0–4) | 2.0 (0–4) | 0.470 |

| Handgrip Strength (kg) | 22.98 ± 6.86 | 23.69 ± 8.64 | 0.577 |

| ASMM (kg) | 17.68 ± 3.13 | 19.19 ± 4.74 | 0.063 |

| ASMM (kg)/h2(m) | 6.73 ± 0.92 | 6.84 ± 1.71 | 0.055 |

| IPAQ | 4083.02 ± 3989.10 | 4717.61 ± 3821.65 | 0.346 |

| MET (total) | 11817.29 ± 3572.44 | 11735.26 ± 4169.68 | 0.744 |

| MET (week) | 1771.20 ± 517.54 | 1765.60 ± 531.18 | 0.755 |

| Parameters | J66 Water (N = 8) | SG9 Water (N = 12) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68.42 ± 7.11 | 65.5 ± 8.53 | 0.424 |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 22.15 ± 2.57 | 25.54 ± 3.94 | 0.076 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.73 ± 0.15 | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 0.463 |

| ALT (U/L) | 18.29 ± 7.65 | 25.50 ± 15.52 | 0.462 |

| AST (U/L) | 20.86 ± 3.67 | 26.88 ± 11.37 | 0.536 |

| Magnesium (mEq/L) | 2.08 ± 0.06 | 2.06 ± 0.15 | 0.776 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 3.47 ± 0.36 | 3.35 ± 0.46 | 0.561 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.5± 0.16 | 9.29 ± 0.45 | 0.557 |

| Total ALP (U/L) | 71.57 ± 19.75 | 84.63 ± 21.05 | 0.247 |

| 25OH-Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 38.47 ± 8.55 | 32.41 ± 12.48 | 0.280 |

| bALP (%) | 12.45 ± 4.54 | 14.22 ± 6.41 | 0.537 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 35.15 ± 19.96 | 35.90 ± 304. | 0.939 |

| Magnesium (urinary, mEq/24h) | 5.92 ± 1.53 | 6.72 ± 3.67 | 0.821 |

| Phosphate (urinary, mg/24h) | 439.71 ± 110.8 | 483.88 ± 323.46 | 0.353 |

| Calcium (urinary, mg/24h) | 142.42 ± 72.65 | 113.05 ± 100.17 | 0.554 |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | 63.14 ± 17.3 | 115.00 ± 101.88 | 0.185 |

| TNF-ALFA | 3.42 ± 5.19 | 25.14 ± 60.33 | 0.486 |

| P3NP | 10.42 ± 2.82 | 8.52 ± 2.54 | 0.758 |

| Sclerostin | 48.1 ± 25.02 | 54.53 ± 39.29 | 0.787 |

| Leptin | 8.04 ± 5.6 | 14.11 ± 12.89 | 0.355 |

| CTX | 0.23 ± 0.18 | 0.41 ± 0.62 | 0.728 |

| Irisin | 134.47 ± 40.27 | 111.06 ± 59.19 | 0.616 |

| P1NP (µg/L) | 481.24 ± 148.73 | 524.15± 311.05 | 0.817 |

| CIRS Severity Index | 1.55 ± 0.29 | 1.39 ± 0.31 | 0.096 |

| CIRS Comorbidity Index | 4.0 (0–6) | 2.50 (0–6) | 0.256 |

| CIRS Total Score | 7 (1–13) | 5 (0–13) | 0.151 |

| EuroQoL-5D Index | 0.96 ± 0.09 | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 0.610 |

| EuroQoL-5D (VAS) | 73.57 ± 13.75 | 68.75 ± 13.56 | 0.430 |

| SPPB Total Score | 5.0 (1–8) | 5.50 (2–8) | 0.876 |

| SPPB Balance | 2.0 (0–4) | 1.0 (0–4) | 1.000 |

| SPPB Gait Speed | 1.0 (1–2) | 2.0 (1–2) | 0.276 |

| SPPB Sit-to-Stand | 2.0 (0–3) | 1.50 (0–3) | 0.904 |

| Handgrip Strength (kg) | 15.48 ± .68 | 15.61 ± 2.74 | 0.876 |

| ASMM (kg) | 15.57 ± 1.99 | 18.03 ± 3.51 | 0.063 |

| ASMM (kg)/h2 (m) | 6.24 ± 0.57 | 6.31 ± 2.0 | 0.057 |

| IPAQ | 2962.14 ± 1539.72 | 1360.63 ± 800.84 | 0.589 |

| MET (total) | 9528.00 ± 4805.66 | 8033.88 ± 4294.99 | 0.758 |

| MET (week) | 1544.57 ± 720.09 | 1677.63 ± 296.44 | 0.396 |

| Parameters | J66 Water (M ± SD) |

SG9 Water (M ± SD) |

Mean Difference |

95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium (mEq/L) | 2.064 ± 0.183 | 2.242 ± 0.837 | -0.022 | [-0.093, 0.049] | 0.541 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 3.612 ± 0.448 | 3.604 ± 0.481 | -0.013 | [-0.110, 0.084] | 0.787 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.455 ± 0.381 | 9.100 ± 1.987 | -0.017 | [-0.080, 0.046] | 0.582 |

| Total ALP (U/L) | 76.94 ± 25.98 | 75.04 ± 17.26 | -2.625 | [-16.798, 11.548] | 0.709 |

| 25OH-Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 28.64 ± 9.99 | 26.64 ± 9.48 | -1.208 | [-6.343, 3.927] | 0.637 |

| bALP (%) | 10.46 ± 4.42 | 9.83 ± 3.60 | -0.663 | [-2.849, 1.523] | 0.538 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 36.88 ± 13.68 | 34.05 ± 12.83 | -1.625 | [-9.432, 6.182] | 0.672 |

| Urinary Magnesium (mEq/24h) | 11.05 ± 4.22 | 10.76 ± 3.33 | 0.282 | [9.694, 12.397] | 0.786 |

| Urinary Phosphate (mg/24h) | 756.61 ± 295.95 | 679.79 ± 278.29 | 76.814 | [655.893, 857.319] | 0.326 |

| Urinary Calcium (mg/24h) | 176.03 ± 83.94 | 242.25 ± 100.07 | -66.220 | [144.227, 207.789] | 0.009 |

| TNF-alfa | 1.82 ± 3.24 | 39.37 ± 163.09 | -0.088 | [-0.591, 0.415] | 0.720 |

| P3NP | 10.75 ± 6.80 | 9.60 ± 5.67 | -0.013 | [-0.073, 0.047] | 0.667 |

| Sclerostin | 65.41 ± 54.79 | 66.85 ± 52.95 | -0.016 | [-0.085, 0.053] | 0.641 |

| Leptin | 15.84 ± 13.26 | 19.22 ± 20.88 | -0.081 | [-0.398, 0.236] | 0.610 |

| CTX | 0.292 ± 0.186 | 0.274 ± 0.242 | -0.007 | [-0.117, 0.103] | 0.899 |

| Irisin | 198.72 ± 168.20 | 160.18 ± 119.30 | -0.006 | [-0.047, 0.035] | 0.770 |

| P1NP | 296.40 ± 163.22 | 313.65 ± 205.81 | -0.008 | [-0.078, 0.062] | 0.812 |

| EuroQoL-5D Index | 0.936 ± 0.110 | 0.935 ± 0.103 | 0.001 | [0.898, 0.973] | 0.992 |

| EuroQoL-5D (VAS) | 74.85 ± 13.43 | 67.50 ± 16.49 | 7.348 | [69.690, 80.007] | 0.069 |

| SPPB Total Score | 10 (3-12) | 9 (5-12) | 0.622 | [-.591, 1.833] | 0.552 |

| SPPB Balance | 4 (1-4) | 4 (1-4) | 0.356 | [-0.207, 0.919] | 0.211 |

| SPPB Gait Speed | 3 (1-4) | 3 (1-4) | 0.181 | [-0.349, 0.712] | 0.495 |

| SPPB Sit-to-Stand | 3 (0-4) | 3 (0-4) | 0.000 | [-0.589, 0.589] | 1.000 |

| Handgrip Strength (kg) | 24.59 ± 7.56 | 25.47 ± 9.82 | -0.885 | [-5.498, 3.728] | 0.555 |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.805 ± 0.225 | 0.733 ± 0.266 | 0.072 | [-0.059, 0.203] | 0.224 |

| ASMM (kg)/h2 (m) | 6.85 ± 1.05 | 7.16 ± 1.17 | -0.570 | [-0.908, 0.277] |

0.292 |

| IPAQ | 3977.67 ± 4491.88 | 3935.29 ± 3408.62 | -153.399 | [8.668, 10.241] |

0.833 |

| MET (total) | 12247.79 ± 2345.71 | 12021.04 ± 3102.27 | -133.28 | [-1218.462, 1671.955] |

0.794 |

| MET (week) | 1791.61 ± 328.38 | 1870.38 ± 282.70 | -78.76 | [-245.486, 87.948] |

0.252 |

| Parameters | J66 Water (M ± SD) |

SG9 Water (M ± SD) |

Mean Difference |

95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnesium (mEq/L) | 2.07 ± 0.13 | 2.07 ± 0.16 | 0.010 | [-0.068, 0.088] | 0.797 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 3.48 ± 0.42 | 3.58 ± 0.58 | -0.117 | [3.316, 3.801] | 0.374 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.12 ± 0.27 | 9.10 ± 0.33 | 0.080 | [8.960, 9.253] | 0.293 |

| Total ALP (U/L) | 68.42 ± 21.68 | 69.03 ± 16.67 | -0.333 | [61.173, 75.960] | 0.948 |

| 25OH-Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 36.68 ± 11.55 | 36.08 ± 10.60 | 1.793 | [31.948, 41.759] | 0.529 |

| bALP (%) | 9.98 ± 3.58 | 10.12 ± 3.50 | -0.183 | [8.614, 11.490] | 0.848 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 32.78 ± 11.57 | 29.44 ± 11.84 | 4.383 | [24.985, 37.772] | 0.136 |

| Urinary Magnesium (mEq/24h) | 9.03 ± 4.79 | 11.90 ± 5.93 | -3.077 | [7.054, 14.163] | 0.035 |

| Urinary Phosphate (mg/24h) | 599.15 ± 288.58 | 611.03 ± 228.96 | -19.866 | [490.909, 707.091] | 0.776 |

| Urinary Calcium (mEq/24h) | 160.82 ± 134.83 | 231.39 ± 113.46 | -66.500 | [118.866, 279.566] | 0.050 |

| TNF-alfa | 4.15 ± 3.26 | 18.77 ± 76.35 | -15.137 | [-16.488, 40.070] | 0.305 |

| P3NP | 7.25 ± 2.75 | 7.31 ± 2.72 | 0.030 | [6.142, 8.001] | 0.963 |

| Sclerostin | 84.81 ± 36.44 | 92.51 ± 46.28 | -9.100 | [68.622, 109.445] | 0.420 |

| Leptin | 14.05 ± 11.10 | 16.86 ± 17.37 | -1.079 | [9.372, 21.081] | 0.775 |

| CTX | 0.371 ± 0.205 | 0.322 ± 0.209 | 0.042 | [0.242, 0.434] | 0.439 |

| Irisin | 53.41 ± 36.48 | 52.44 ± 26.24 | 1.680 | [42.168, 67.666] | 0.842 |

| P1NP | 402.09 ± 223.45 | 385.39 ± 201.99 | 4.700 | [307.675, 470.225] | 0.933 |

| EuroQoL-5D Index | 0.91 ± 0.11 | 0.95 ± 0.09 | -0.037 | [0.877, 0.987] | 0.155 |

| EuroQoL-5D (VAS) | 70.45 ± 15.33 | 69.09 ± 13.78 | 1.833 | [63.684, 76.150] | 0.627 |

| SPPB Total Score | 10 (6-12) | 9 (6-12) | .171 | -0.71 to 1.32 | 0.539 |

| SPPB Balance | 4 (1-4) | 4 (1-4) | 0.000 | [3.577, 4.023] | 1.000 |

| SPPB Gait Speed | 3 (1-4) | 3 (1-4) | 0.133 | [2.676, 3.457] | 0.562 |

| SPPB Sit-to-Stand | 3 (0-4) | 3 (0-4) | 0.066 | [2.253, 3.147] | 0.821 |

| Handgrip Strength (kg) | 22.28 ± 7.18 | 23.85 ± 8.98 | -2.001 | [-6.326, 2.324] | 0.358 |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.94 ± 0.30 | 0.85 ± 0.21 | 0.072 | [-.036, .236] | 0.146 |

| ASMM (kg)/h2 (m) | 6.80 ± 0.99 | 7.79 ± 1.49 | -.890 | [-1.499, -.281] | 0.005 |

| IPAQ | 3568.100 ± 4595.32 | 21966.267 ± 98552.99 | -18398.167 | [-23161.187, 48696.183] | 0.334 |

| MET (total) | 11920.18 ± 2503.44 | 12824.36 ± 2470.98 | -620.333 |

[-1847.544, 606.878] | 0.316 |

| MET (week) | 1800.15 ± 389.12 | 1870.70 ± 343.38 | -44.833 | [-228.576, 138.910] | 0.627 |

| Parameters | J66 Water (n=12) (M ± SD) |

SG9 Water (n=8) (M ± SD) |

Mean Difference |

95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 3.47 ± 0.12 | 3.80 ± 0.81 | -0.25 | [-1.24 ; 0.74] | 0.569 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.33 ± 0.06 | 9.36 ± 0.34 | 0.17 | [-0.40 ; 0.73] | 0.515 |

| Total ALP (U/L) | 86.00 ± 31.77 | 83.40 ± 22.72 | -1.40 | [-40.60 ; 37.80] | 0.935 |

| 25OH-Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 29.50 ± 4.33 | 27.98 ± 13.17 | 1.12 | [-15.11 ; 17.35] | 0.875 |

| bALP (%) | 14.50 ± 5.76 | 10.64 ± 4.59 | 1.99 | [-6.34 ; 10.31] | 0.591 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 28.43 ± 8.43 | 28.30 ± 9.38 | 2.50 | [-11.71 ; 16.71] | 0.690 |

| Urinary Magnesium (mEq/24h) | 11.87 ± 3.19 | 9.84 ± 3.42 | 1.01 | [-4.33 ; 6.35] | 0.668 |

| Urinary Phosphate (mg/24h) | 760.33 ± 99.75 | 677.00 ± 233.77 | 8.25 | [-323.48 ; 339.98] | 0.955 |

| Urinary Calcium (mg/24h) | 241.33 ± 96.60 | 226.00 ± 109.44 | -4.00 | [-163.82 ; 155.82] | 0.954 |

| TNF-alfa | 2.09 ± 2.36 | 162.19 ± 356.56 | -160.63 | [-588.17 ; 266.92] | 0.404 |

| P3NP | 7.43 ± 2.16 | 8.76 ± 2.38 | -0.24 | [-4.31 ; 3.84] | 0.895 |

| Sclerostin | 58.40 ± 46.91 | 96.36 ± 82.41 | -41.71 | [-148.51 ; 65.09] | 0.386 |

| Leptin | 12.58 ± 5.18 | 15.06 ± 16.24 | -4.32 | [-24.65 ; 16.01] | 0.631 |

| CTX | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.34 ± 0.44 | 0.03 | [-0.51 ; 0.56] | 0.905 |

| Irisin | 101.00 ± 101.06 | 139.18 ± 99.62 | -18.93 | [-171.28 ; 133.42] | 0.777 |

| P1NP | 436.15 ± 160.12 | 342.91 ± 369.59 | 41.62 | [-434.12 ; 517.35] | 0.842 |

| EuroQoL-5D Index | 0.827 ± 0.000 | 0.937 ± 0.116 | -0.07 | [-0.23 ; 0.10] | 0.370 |

| EuroQoL-5D (VAS) | 80.00 ± 0.00 | 60.00 ± 15.81 | 20.00 | [1.04 ; 38.96] | 0.041 |

| SPPB Total Score | 8 (3-10) | 8 (6-11) | -1.25 | [-5.77 ; 3.27] | 0.534 |

| SPPB Balance | 3 (1-4) | 3.5 (1-4) | -0.25 | [-2.39 ; 1.89] | 0.790 |

| SPPB Gait Speed | 3 (1-3) | 3 (1-4) | -0.55 | [-2.40 ; 1.30] | 0.505 |

| SPPB Sit-to-Stand | 1 (1-3) | 2 (0-4) | -0.45 | [-2.30 ; 1.40] | 0.584 |

| Handgrip Strength (kg) | 14.08 ± 1.95 | 18.80 ± 6.06 | -4.57 | [-12.03 ; 2.89] | 0.190 |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.787 ± 0.30 | 0.818 ± 0.17 | -0.16 | [-0.58 ; 0.26] | 0.397 |

| ASMM (kg)/h2 (m) | 6.04 ± 0.56 | 6.93 ± 0.34 | -0.88 | [-1.51 ; -0.26] | 0.012 |

| IPAQ | 2324.063 ± 1396.6592 | 3301.364 ± 4300.8436 |

-915.13 | [-8102.27; 6272.02] | 0.772 |

| MET (total) | 10806.33 ± 2307.93 | 9729.80 ± 4996.79 | 1042.45 | [-5260.97; 7345.87] | 0.707 |

| MET (week) | 1583.67 ± 331.54 | 1746.00 ± 178.16 | -161.75 | [-514.82; 191.32] | 0.315 |

| Parameters | J66 Water (M ± SD) |

SG9 Water (M ± SD) |

Mean Difference |

95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 3.42 ± 0.46 | 3.62 ± 0.66 |

-0.197 | [-0.996, 0.602] | 0.588 | |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.00 ± 0.19 | 8.88 ± 0.27 | 0.080 | [-0.160, 0.320] | 0.510 | |

| Total ALP (U/L) | 70.40 ± 13.98 | 74.33 ± 13.23 | -0.333 | [-8.215, 7.548] | 0.931 | |

| 25OH-Vitamin D (ng/mL) |

46.34 ± 12.67 | 34.38 ± 11.95 | 1.793 | [-3.841, 7.427] | 0.529 | |

| bALP (%) | 10.32 ± 1.32 | 10.38 ± 3.21 | -0.183 | [-2.215, 1.849] | 0.848 | |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 30.90 ± 14.25 | 29.88 ± 10.40 | 4.383 | [-1.428, 10.194] | 0.136 | |

|

Urinary Magnesium (mEq/24h) |

7.38 ± 3.31 | 11.82 ± 8.31 | -3.077 | [-5.943, -0.211] | 0.035* | |

| Urinary Phosphate (mg/24h) |

385.20 ± 182.19 | 603.67 ± 156.71 | -19.866 | [-169.313, 129.581] | 0.776 | |

|

Urinary Calcium (mg/24h) |

85.80 ± 69.76 | 218.83 ± 125.65 | -66.500 | [-133.267, 0.267] | 0.050* | |

| TNF-alfa | 3.30 ± 1.4 | 77.76 ± 178.45 | -15.137 | [-41.313, 11.039] | 0.305 | |

| P3NP | 5.97 ± 1.48 | 8.80 ± 1.99 | 0.030 | [-1.146, 1.206] | 0.963 | |

| Sclerostin | 76.80 ± 29.25 | 112.98 ± 92.45 | -9.100 | [-31.413, 13.213] | 0.420 | |

| Leptin | 10.49 ± 5.95 | 15.11 ± 8.98 | -1.079 | [-8.987, 6.829] | 0.775 | |

| CTX | 0.41 ± 0.19 | 0.35 ± 0.21 | 0.042 | [-0.064, 0.148] | 0.439 | |

| Irisin | 35.84 ± 13.75 | 48.47 ± 23.18 | 1.680 | [-15.986, 19.346] | 0.842 | |

| P1NP | 365.60 ± 164.66 | 465.83 ± 310.48 | 4.700 | [-71.373, 80.773] | 0.933 | |

| EuroQoL-5D Index | 0.85 ± 0.84 | 0.94 ± 0.09 | -0.037 | [-0.088, 0.014] | 0.155 | |

| EuroQoL-5D (VAS) | 76.00 ± 8.94 | 65.00 ± 12.25 |

1.833 | [-5.410, 9.076] | 0.627 | |

| SPPB Total Score | 8 (6-11) | 9 (7-12) | 0.622 | [-1.310, 2.554] | 0.539 | |

| SPPB Balance | 4 (1-4) | 4 (3-4) | 0.000 | [-0.303, 0.303] | 1.000 | |

| SPPB Gait Speed | 3 (1-4) | 3 (2-4) | 0.133 | [-0.325, 0.591] | 0.562 | |

| SPPB Sit-to-Stand | 2 (1-3) | 2 (0-4) | 0.066 | [-0.497, 0.629] | 0.821 | |

| Handgrip Strength (kg) | 17.3 ± 9.86 | 18.74 ± 6.49 | -1.567 | [-4.978, 1.844] | 0.358 | |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.78 ± 0.24 | 0.79 ± 0.15 |

0.072 | [-0.026, 0.170] | 0.146 | |

| ASMM (kg)/h2 (m) | 6.39 ± 0.627 | 7.55 ± 0.69 | -0.988 | [-1.682, -0.294] | 0.005 | |

| IPAQ | 2425.00 ± 1537.425 | 1165.00 ± 612.88 | 1260.000 | [-277.113, 2797.113] | 0.097 | |

| MET (total) | 10426.0000 ± 2383.29709 |

12027.50 ± 1810.45 |

-904.183 | [-2692.106, 883.740] | 0.316 | |

| MET (week) | 1511.2000 ± 356.49923 |

1774.33 ± 276.51 |

-70.550 | [-346.106, 205.006] | 0.627 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).