Submitted:

24 December 2025

Posted:

31 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and RSV Detection

2.2. RSV Classification Using G Gene Sequences

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Information and Demographics

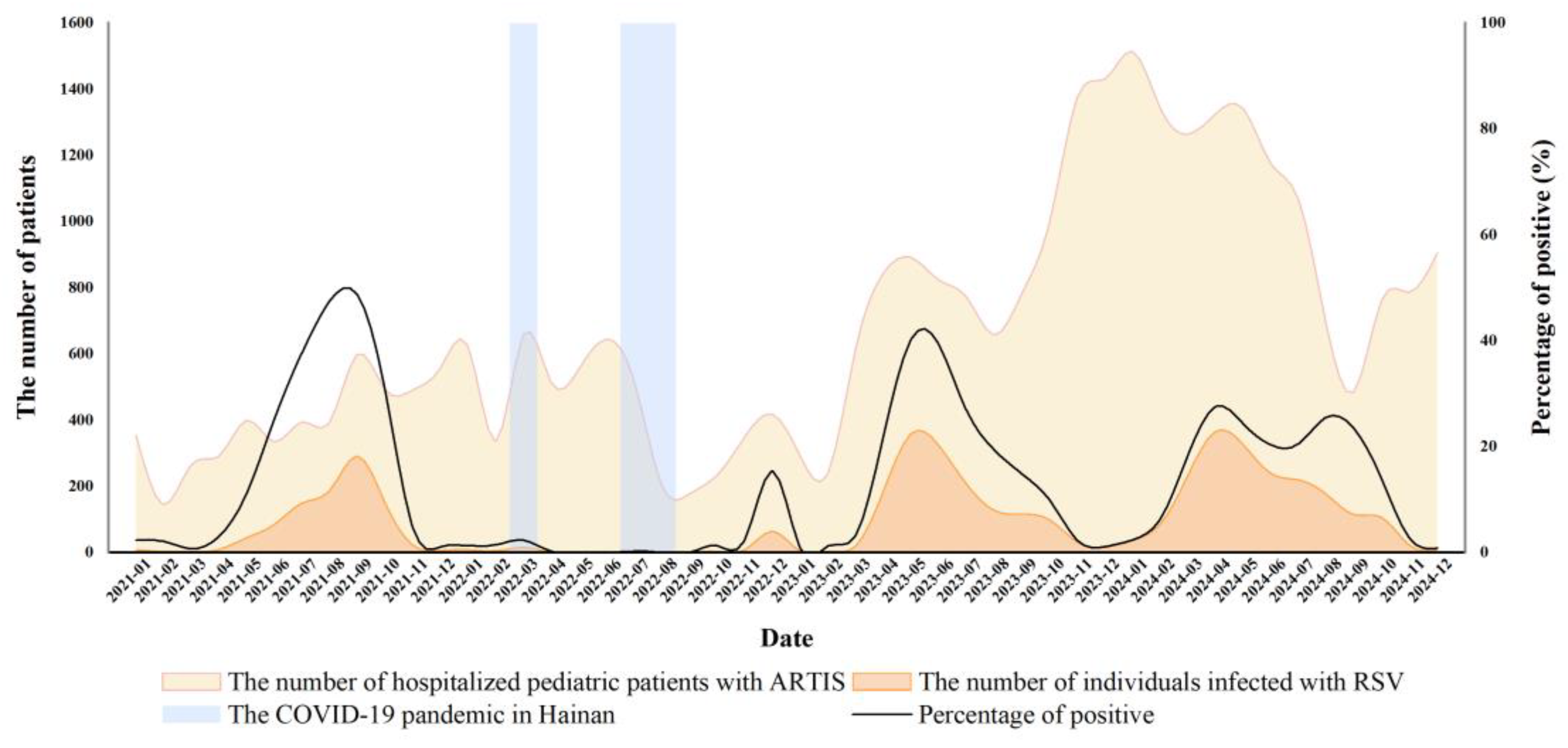

3.2. Analysis of RSV Infection Trends Before and After the Ending of Dynamic Zero-COVID Policy

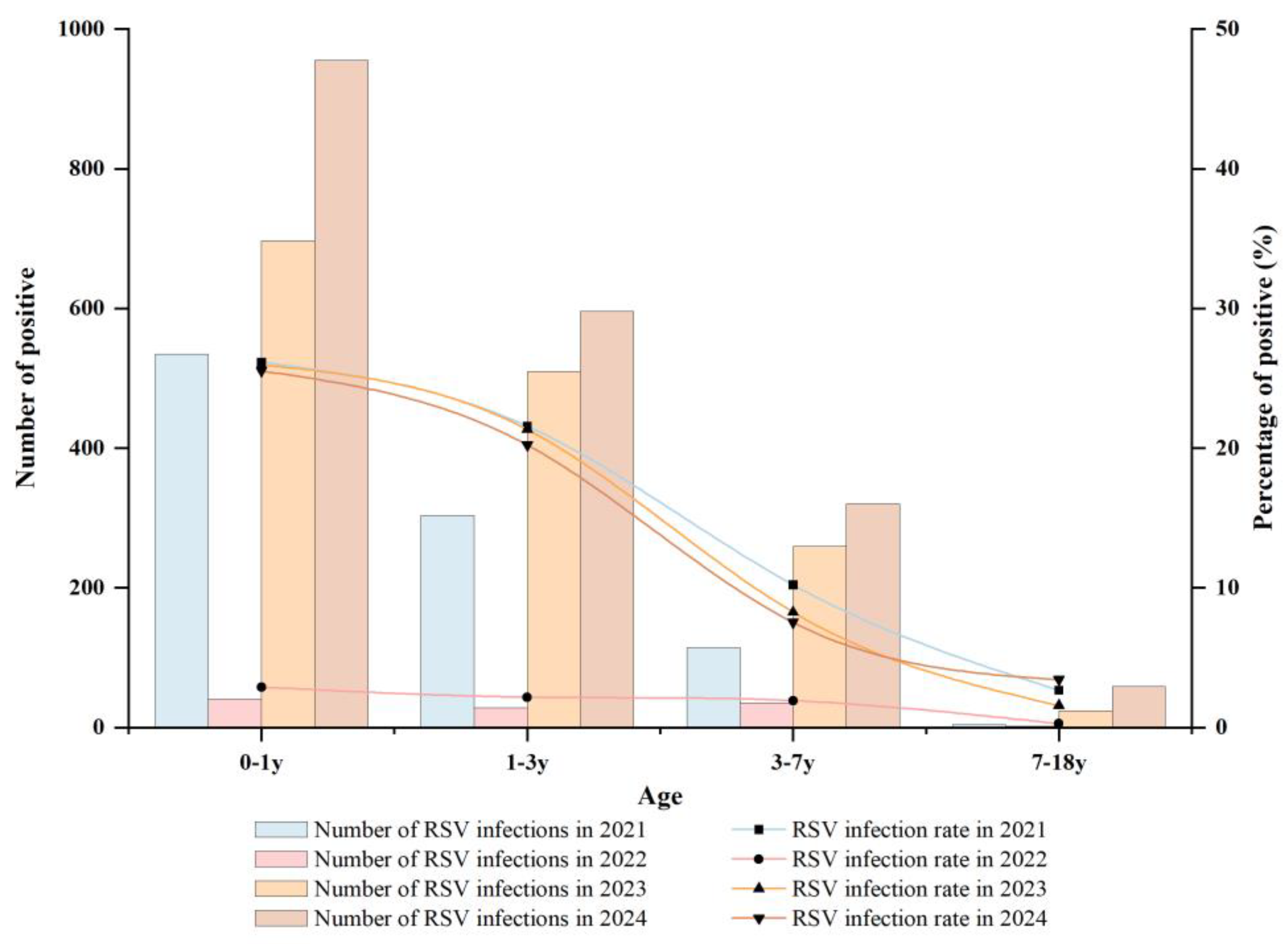

3.3. Age-Based Analysis of RSV Infections

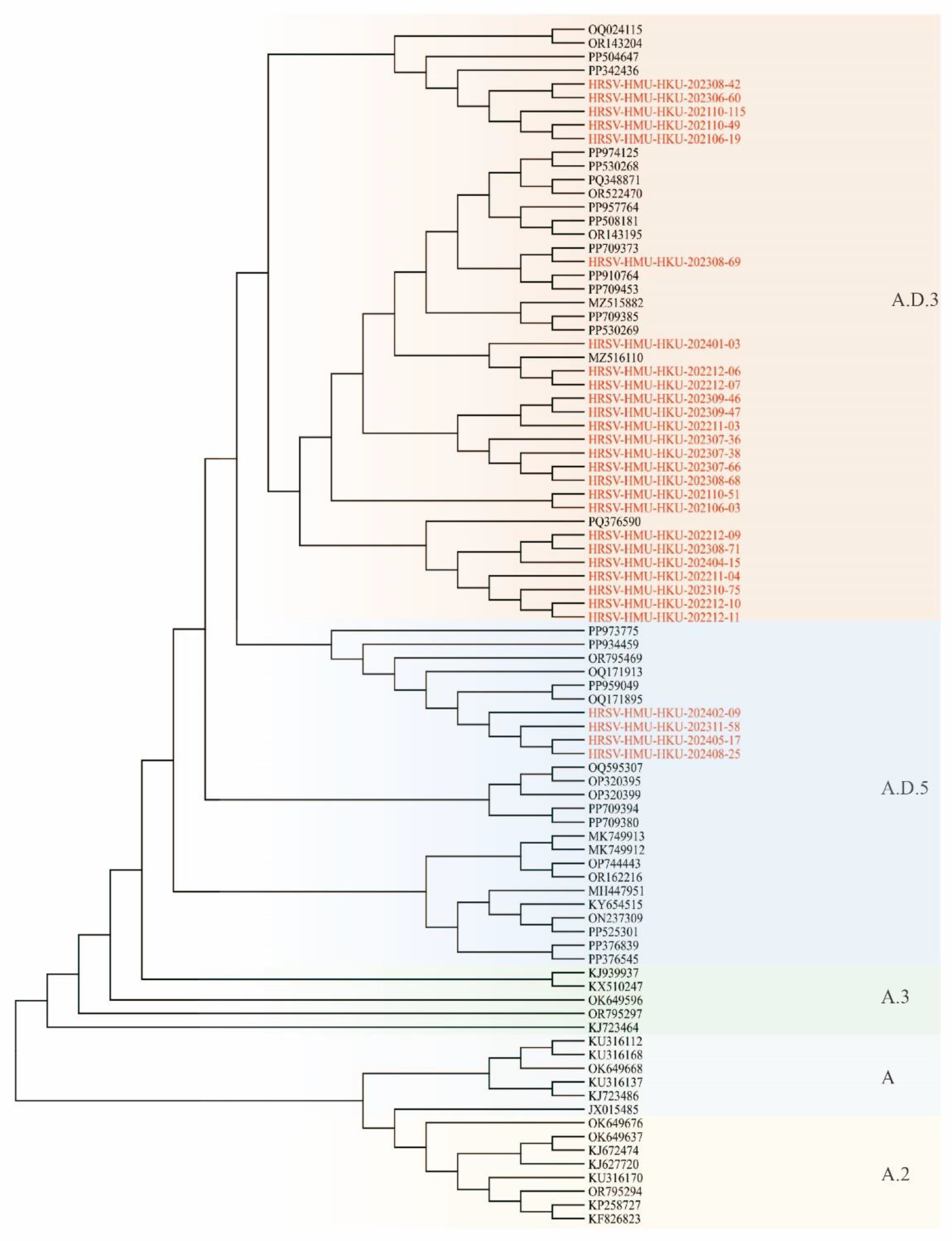

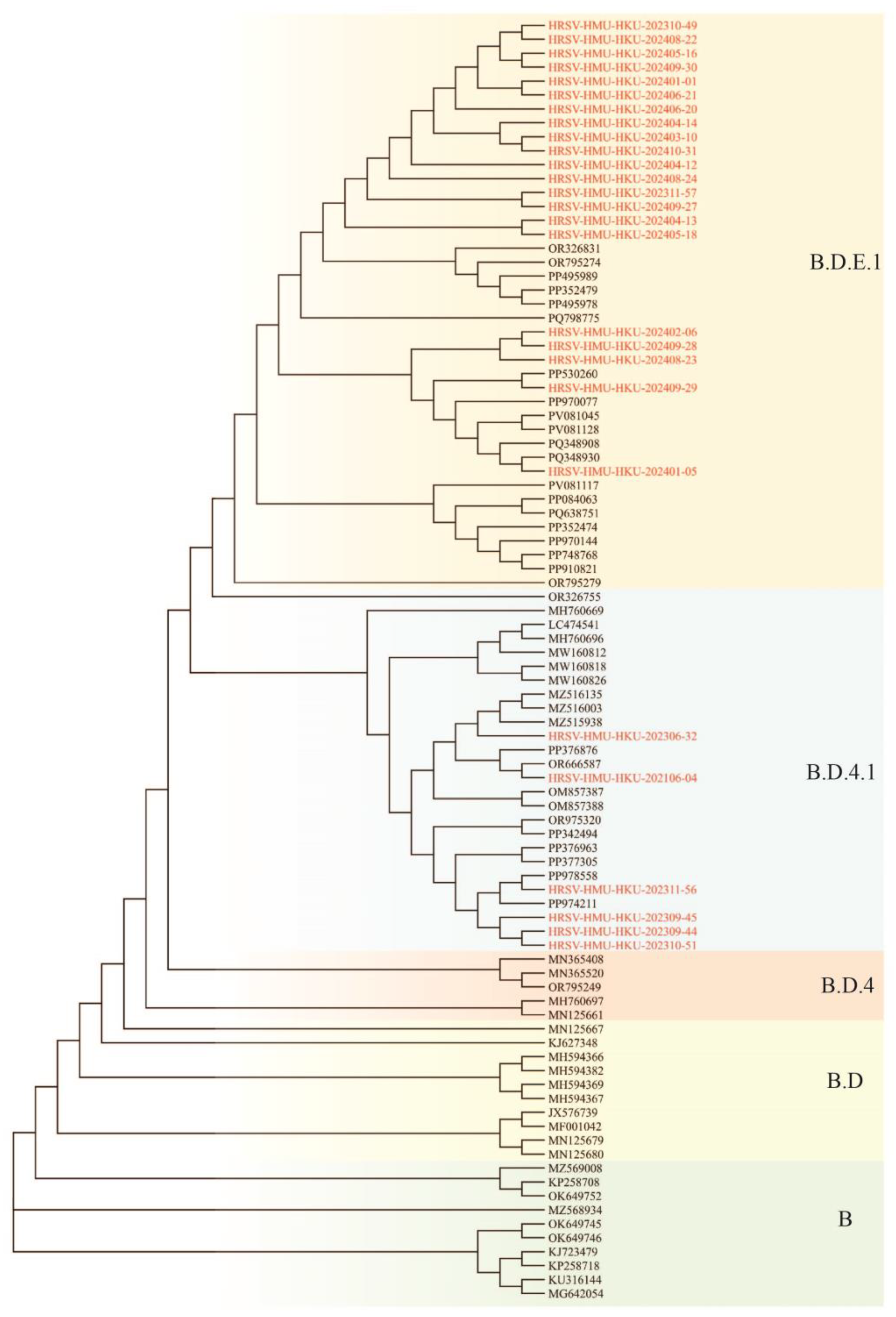

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of RSV

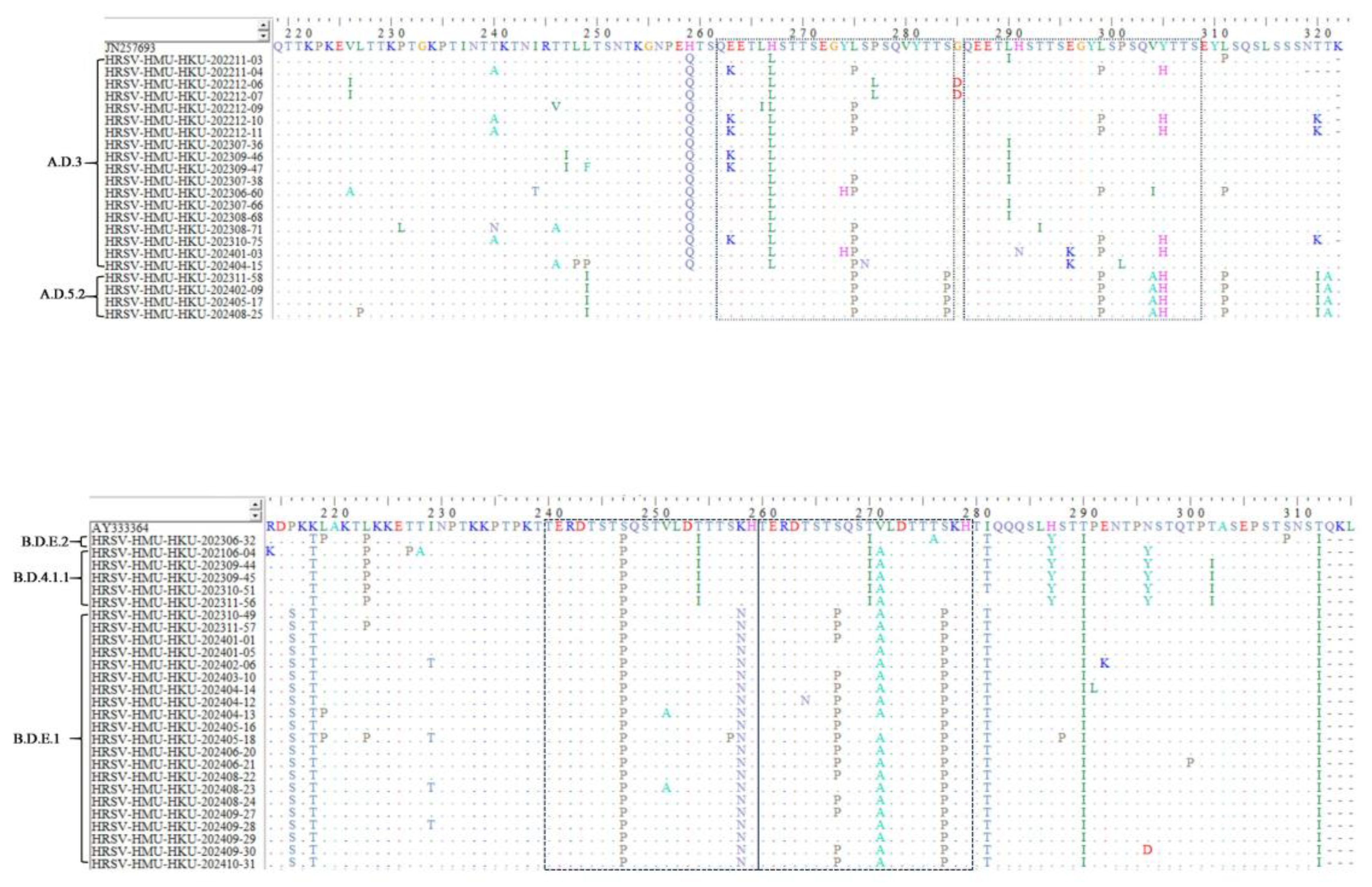

3.5. Amino Acid Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, T.; Bont, L.J.; Chu, H.Y.; Zar, H.J.; Wahi-Singh, B.; Ma, Y.; Cong, B.; Sharland, E.; et al. Global disease burden of and risk factors for acute lower respiratory infections caused by respiratory syncytial virus in preterm infants and young children in 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregated and individual participant data. Lancet 2024, 403, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Mazur, N.; Caballero, M.T.; Nunes, M.C. Severe respiratory syncytial virus infection in children: burden, management, and emerging therapies. Lancet 2024, 404, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Escalante, J.C.; Comas-García, A.; Bernal-Silva, S.; Robles-Espinoza, C.D.; Gómez-Leal, G.; Noyola, D.E. Respiratory syncytial virus A genotype classification based on systematic intergenotypic and intragenotypic sequence analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, C.; An, S.; Lu, G.; Jin, R.; Xu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, A.; et al. A multi-center study on Molecular Epidemiology of Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus from Children with Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infections in the Mainland of China between 2015 and 2019. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 1475–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, E.J.; Uyeki, T.M.; Chu, H.Y. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on community respiratory virus activity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, S.; Brendish, N.J.; Clark, T.W. SARS-CoV-2 has displaced other seasonal respiratory viruses: Results from a prospective cohort study. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.E.; Park, S.W.; Yang, W.; Vecchi, G.A.; Metcalf, C.J.E.; Grenfell, B.T. The impact of COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on the future dynamics of endemic infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 30547–30553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, K.; Jung, J.; Hong, J.; Kim, M.; Ahn, J.G.; Kim, J.-H.; Kang, J.-M. Impact of Nonpharmaceutical Interventions on the Incidence of Respiratory Infections During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in Korea: A Nationwide Surveillance Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, e184–e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.W.; Bialasiewicz, S.; Dwyer, D.E.; Dilcher, M.; Tellier, R.; Taylor, J.; Hua, H.; Jennings, L.; Kok, J.; Levy, A.; et al. Where have all the viruses gone? Disappearance of seasonal respiratory viruses during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Med Virol. 2021, 93, 4099–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.N.; Yao, J.H.; Wu, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, C.; Wang, G.F.; Wu, Z.Y.; Yang, W.Z.; et al. Experience and thinking on the normalization stage of prevention and control of COVID-19 in China. 2021, 101, E001. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Qi, J.; Kang, L.; Hu, G.; Gong, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, F.; et al. Novel imported clades accelerated the RSV surge in Beijing, China, 2023-2024. J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Shi, S.; Jin, Y.; Wang, G.; Peng, R.; An, J.; Huang, Y.; Hu, X.; Tang, C.; Niu, Y.; et al. Epidemiology and Genetic Evolutionary Analysis of Influenza Virus Among Children in Hainan Island, China, 2021–2023. Pathogens 2025, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Banu, A.; Jia, Y.; Chang, M.; Wang, G.; An, J.; Huang, Y.; Hu, X.; Tang, C.; Li, Z.; et al. Circulation pattern and genetic variation of rhinovirus infection among hospitalized children on Hainan Island, before and after the dynamic zero-COVID policy, from 2021 to 2023. J. Med Virol. 2024, 96, e29755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Banu, A.; Zeng, X.; Shi, S.; Peng, R.; Chen, S.; Ge, N.; Tang, C.; Huang, Y.; Wang, G.; et al. Epidemiology of Human Parainfluenza Virus Infections among Pediatric Patients in Hainan Island, China, 2021–2023. Pathogens 2024, 13, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agoti, C.N.; Mwihuri, A.G.; Sande, C.J.; Onyango, C.O.; Medley, G.F.; Cane, P.A.; Nokes, D.J. Genetic Relatedness of Infecting and Reinfecting Respiratory Syncytial Virus Strains Identified in a Birth Cohort From Rural Kenya. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 206, 1532–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Ashman, M.; Taha, M.-K.; Varon, E.; Angoulvant, F.; Levy, C.; Rybak, A.; Ouldali, N.; Guiso, N.; Grimprel, E. Pediatric Infectious Disease Group (GPIP) position paper on the immune debt of the COVID-19 pandemic in childhood, how can we fill the immunity gap? Infect. Dis. Now 2021, 51, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piret, J.; Boivin, G. Viral Interference between Respiratory Viruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umar, S.; Yang, R.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ke, P.; Qin, S. Molecular epidemiology and characteristics of respiratory syncytial virus among hospitalized children in Guangzhou, China. Virol. J. 2023, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phyu, W.W.; Htwe, K.T.Z.; Saito, R.; Kyaw, Y.; Lin, N.; Dapat, C.; Osada, H.; Chon, I.; Win, S.M.K.; Hibino, A.; et al. Evolutionary analysis of human respiratory syncytial virus collected in Myanmar between 2015 and 2018. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021, 93, 104927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chon, I.; Phyu, W.W.; Kyaw, Y.; Aye, M.M.; Setk, S.; Win, S.M.K.; Yoshioka, S.; Wagatsuma, K.; Sun, Y.; et al. Molecular epidemiological surveillance of respiratory syncytial virus infection in Myanmar from 2019 to 2023. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramuto, F.; Maida, C.M.; Mazzucco, W.; Costantino, C.; Amodio, E.; Sferlazza, G.; Previti, A.; Immordino, P.; Vitale, F. Molecular Epidemiology and Genetic Diversity of Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Sicily during Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Surveillance Seasons. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pu, D.; Liu, Q.; Li, B.; Lu, B.; Cao, B. Epidemic Outbreak of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection After the end of the Zero-COVID-19 Policy in China: Molecular Characterization and Disease Severity Associated With a Novel RSV-B Clade. J. Med Virol. 2025, 97, e70343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langedijk, A.C.; Vrancken, B.; Lebbink, R.J.; Wilkins, D.; Kelly, E.J.; Baraldi, E.; Santos, A.H.M.d.L.; Danilenko, D.M.; Choi, E.H.; Palomino, M.A.; et al. The genomic evolutionary dynamics and global circulation patterns of respiratory syncytial virus. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, S.S.; Cowling, B.J.; Peiris, J.M.; Chan, E.L.; Wong, W.H.; Lee, K.P. Effects of Nonpharmaceutical COVID-19 Interventions on Pediatric Hospitalizations for Other Respiratory Virus Infections, Hong Kong. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, H.G.; Ritschel, T.; Pascual, G.; Brakenhoff, J.P.J.; Keogh, E.; Furmanova-Hollenstein, P.; Lanckacker, E.; Wadia, J.S.; A Gilman, M.S.; Williamson, R.A.; et al. Structural basis for recognition of the central conserved region of RSV G by neutralizing human antibodies. PLOS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedechkin, S.O.; George, N.L.; Wolff, J.T.; Kauvar, L.M.; DuBois, R.M. Structures of respiratory syncytial virus G antigen bound to broadly neutralizing antibodies. Sci. Immunol. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Escalante, J.C.; Comas-García, A.; Bernal-Silva, S.; Noyola, D.E. Respiratory syncytial virus B sequence analysis reveals a novel early genotype. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.N.; Hwang, J.; Yoon, S.-Y.; Lim, C.S.; Cho, Y.; Lee, C.-K.; Nam, M.-H. Molecular characterization of human respiratory syncytial virus in Seoul, South Korea, during 10 consecutive years, 2010–2019. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0283873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 618/3002(20.57) | 54/3173(1.70) | 968/5951(16.27) | 1192/7507(15.88) | 2832/19633(14.42) |

| Female | 339/1719(19.72) | 52/2054(2.53) | 522/3781(13.81) | 738/5142(14.35) | 1651/12696(13.00) |

| χ2 value | 0.51 | 4.32 | 10.79 | 5.50 | 13.03 |

| p value | 0.477 | 0.038 | 0.001 | 0.019 | <0.001 |

| season | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | 56(5.85) | 16(0.93) | 569(24.14) | 926(23.56) |

| Summer | 422(37.54) | 1(0.07) | 655(29.09) | 632(21.64) |

| Autumn | 462(29.20) | 12(1.57) | 245(7.76) | 240(11.77) |

| Winter | 17(1.61) | 77(5.61) | 21(1.07) | 132(3.51) |

| χ2 value | 636.76 | 126.29 | 917.55 | 721.83 |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Age | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total | χ2 value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1y | 535/2045(26.16) | 41/1413(2.90) | 697/2684(25.97) | 955/3740(25.53) | 2228/9882(22.55) | 364.70 | <0.001 |

| 1-3y | 304/1409(21.57) | 28/1305(2.15) | 510/2391(21.33) | 596/2946(20.23) | 1438/8051(17.86) | 263.83 | <0.001 |

| 3-7y | 114/1117(10.20) | 35/1809(1.93) | 259/3140(8.25) | 320/4248(7.53) | 728/10314(7.06) | 97.50 | <0.001 |

| 7-18y | 4/150(2.67) | 2/700(0.29) | 24/1517(1.58) | 59/1715(3.44) | 89/4082(2.18) | 27.26 | <0.001 |

| Total | 957/4721(20.27) | 106/5227(2.03) | 1490/9732(15.31) | 1930/12649(15.25) | 4483/32329(13.86) | 812.97 | <0.001 |

| χ2 value | 144.17 | 16.293 | 643.24 | 743.12 | 1597.85 | / | |

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| lineage | Sample number | N85 | N100 | N103 | N135 | N179 | N237 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ON1 | |||||||

| JN257693 | + | + | + | + | |||

| A.D.3 | |||||||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202211-03 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202211-04 | + | + | + | + | |||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202212-06 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202212-07 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202212-09 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202212-10 | + | + | + | + | |||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202212-11 | + | + | + | ||||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202401-03 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202404-15 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202307-36 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202309-46 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202309-47 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202307-38 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202306-60 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202307-66 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202308-68 | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202308-71 | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202310-75 | + | + | + | + | |||

| A.D.5.2 | |||||||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202408-25 | + | + | + | + | |||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202405-17 | + | + | + | + | |||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202311-58 | + | + | + | + | |||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202402-09 | + | + | + | + |

| lineage | Sample number | N230 | N258 | N296 | N310 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA9 | |||||

| AY333364 | + | + | + | ||

| B.D.4.1.1 | |||||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202306-32 | + | + | |||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202106-04 | + | ||||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202309-44 | + | ||||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202309-45 | + | ||||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202310-51 | + | ||||

| B.D.E.1 | |||||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202311-56 | + | ||||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202310-49 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202311-57 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202401-01 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202401-05 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202402-06 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202403-10 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202404-14 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202404-12 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202404-13 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202405-16 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202405-18 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202406-20 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202406-21 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202408-22 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202408-23 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202408-24 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202409-27 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202409-28 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202409-29 | + | + | + | ||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202409-30 | + | + | |||

| HRSV-HMU-HKU-202410-31 | + | + | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.