1. Introduction

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) is a major cause of respiratory tract infections worldwide in infants and young children [

1]. It is highly contagious, transmitted through respiratory droplets and touch, posing a significant global health burden [

2], predominantly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [

3]. Globally, one in every 50 deaths among under-five children is attributable to RSV. In 2019, there were around 3.6 million hospital admissions and 26,300 in-hospital deaths globally in children under five years due to RSV [

3]. LMICs bear the brunt of the RSV burden, accounting for over 95% of RSV-acute lower respiratory infections and over 97% of related mortality in all age groups globally [

3].

Bangladesh, an LMIC, faces a significant RSV burden, with approximately 90% of excess mortality during the RSV season attributed to RSV infections [

4]. Hospitalization rates due to RSV are considerable, with RSV having the highest burden among both hospitalized (34%) and non-hospitalized (39%) cases in children under the age of five [

5].

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant changes in the epidemiology of RSV worldwide. Studies in developed countries have reported delayed RSV peaks during the pandemic following an absence during its typical season [

6]. Reduced transmission of RSV was observed due to non-pharmaceutical interventions like lockdowns and school closings [

7]. Furthermore, changes in the age distribution of RSV infections have been noted, with preschool-aged children being more affected than school-going children [

8]. However, the specific impact of the pandemic on RSV epidemiology in LMICs, including Bangladesh, remains an important data gap that needs to be addressed.

Understanding the burden of RSV-associated under-five child deaths in Bangladesh, both during and before the COVID-19 pandemic, is critical for designing context-specific interventions and public health policies. Data on RSV-associated morbidity and mortality may guide effective strategies to reduce RSV burden. This study aimed to address these gaps and generate critical evidence on RSV-associated deaths among under-five children with SARI in Bangladesh, ultimately contributing to improved public health responses and better outcomes for the vulnerable under-five population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study population

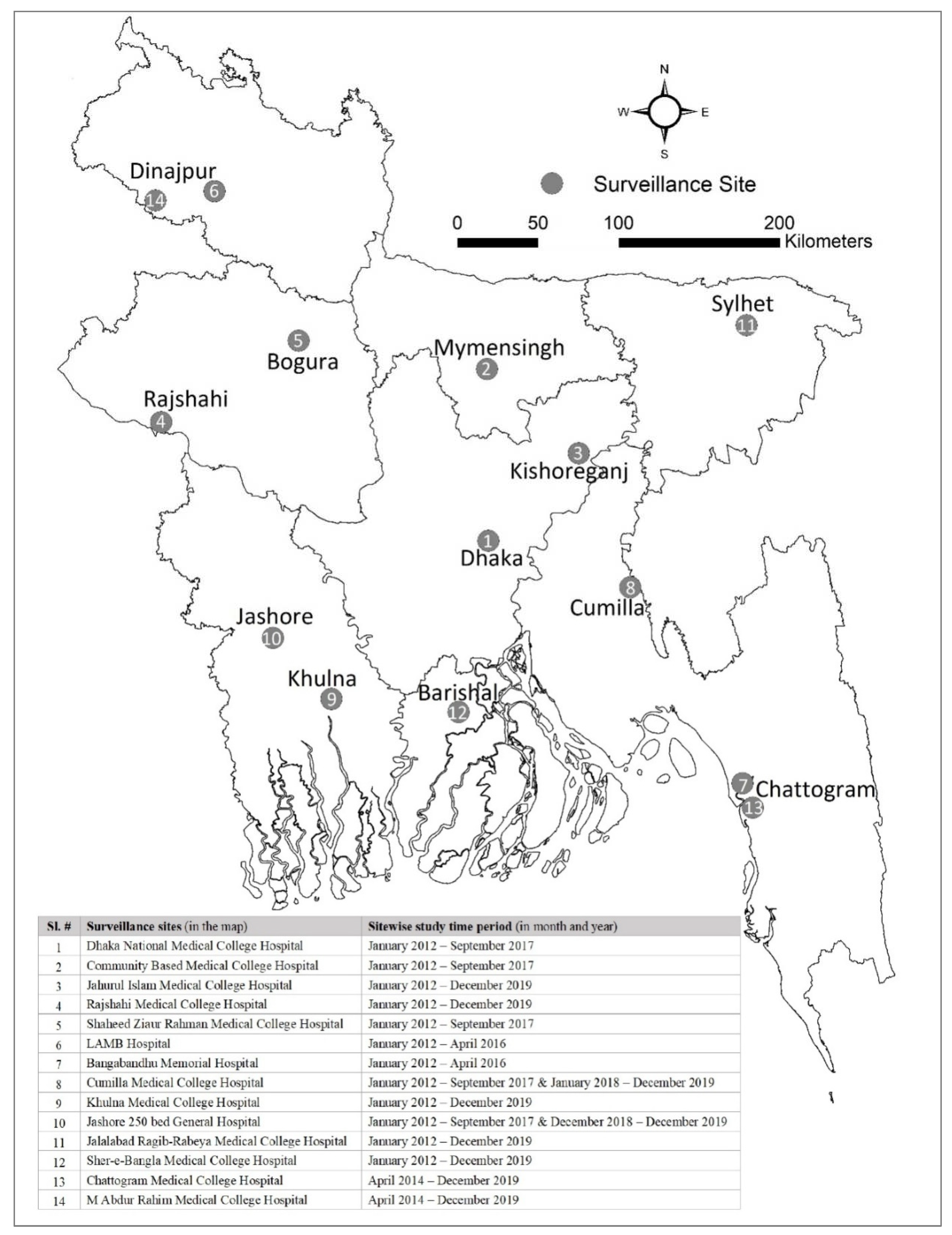

We analyzed the data from the hospital-based influenza surveillance (HBIS) system to characterize SARI deaths. The HBIS was initiated in Bangladesh in 2007 in 12 tertiary care hospitals. The surveillance was conducted in a maximum of 14 hospitals at different geographical locations across Bangladesh over different time points (

Figure 1), the number of sites ranged from 7-14 depending on the year. Since 2018, it has been operational in nine tertiary care level hospitals (seven public and two private) geographically distributed all over Bangladesh. The activities of the surveillance system are carried out jointly by the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) and the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR) of the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) with the technical support from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC). The inpatient capacity of the surveillance hospitals ranges from 500 to 1500 beds with a 100%–150% bed occupancy rate.

For this study, we analyzed the data of the participants enrolled from August 2009 to March 2022 in HBIS. Despite the ongoing pandemic in 2020 and subsequent pandemic control efforts, the surveillance remained active and continued its operations six days a week (Saturday to Thursday) by collecting data from the in-patient departments of the study hospitals. In our study, the pre-pandemic period spanned from August 2009 to February 2020, and the pandemic period was considered from March 2020 to March 2022.

2.2. Case identification and data collection:

The surveillance physicians and support staff screened and identified the SARI patients who met the WHO case definition of SARI defined as an acute respiratory infection with subjective or measured fever of ≥ 38°C and a history of cough with onset within the last 10 days from inpatient departments of medicine and pediatrics wards, coronary care units (CCU), and specialized COVID-19 isolation wards established during the COVID-19 pandemic.

After identification, written informed consent was obtained from the parents or caregivers of the under-five children with SARI. The surveillance physicians then enrolled and performed a physical examination of all the under-five children with SARI. This was followed by the collection of data using a standardized surveillance form in a handheld computer. The form included demographic, clinical, history of comorbid conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, cancer, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart diseases) and available diagnostic findings of the patients. At the time of discharge, outcome status (referral to another facility, partial recovery, full recovery, and in-hospital death) of the participants were recorded.

2.3. Sample collection and laboratory analysis

Maintaining all aseptic precautions, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs were collected from the SARI patients after written informed consent from their parents or caregivers to participate in our study. Swabs were placed into viral transport media, stored in a nitrogen dry shipper on site and then transported to the virology laboratory of icddr,b, Dhaka every week. We tested all the in-hospital death cases for common respiratory viruses: RSV, adenoviruses, influenza, human metapneumovirus (HMPV), human parainfluenza viruses (HPIV) and SARS-CoV-2 (from March 2020) by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR).

2.4. Data analysis:

We calculated descriptive statistics for all variables. Continuous variables were summarized using median and interquartile range (IQR) based on the distribution of the variables. We provided frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. We used Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests to compare the contribution of RSV in SARI mortality among under-5 children before and during the pandemic where we considered the p-value <0.05 statistically significant. We conducted the statistical analyses using Stata version 15, College Station, Texas 77845 USA.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of study participants

We enrolled 8,923 under 5-year-old children with SARI during the pre-COVID-19 pandemic phase (August 2009-February 2020). Median age was 6 months (IQR: 2.5–12) and 67% were male (5956). During the pandemic period (March 2020-March 2022), 2,570 children < 5 years were enrolled. Median age was found 6 months (IQR: 3–14); 65% males (1680) (

Table 1).

3.2. Contribution of RSV in SARI mortality pre and during pandemic

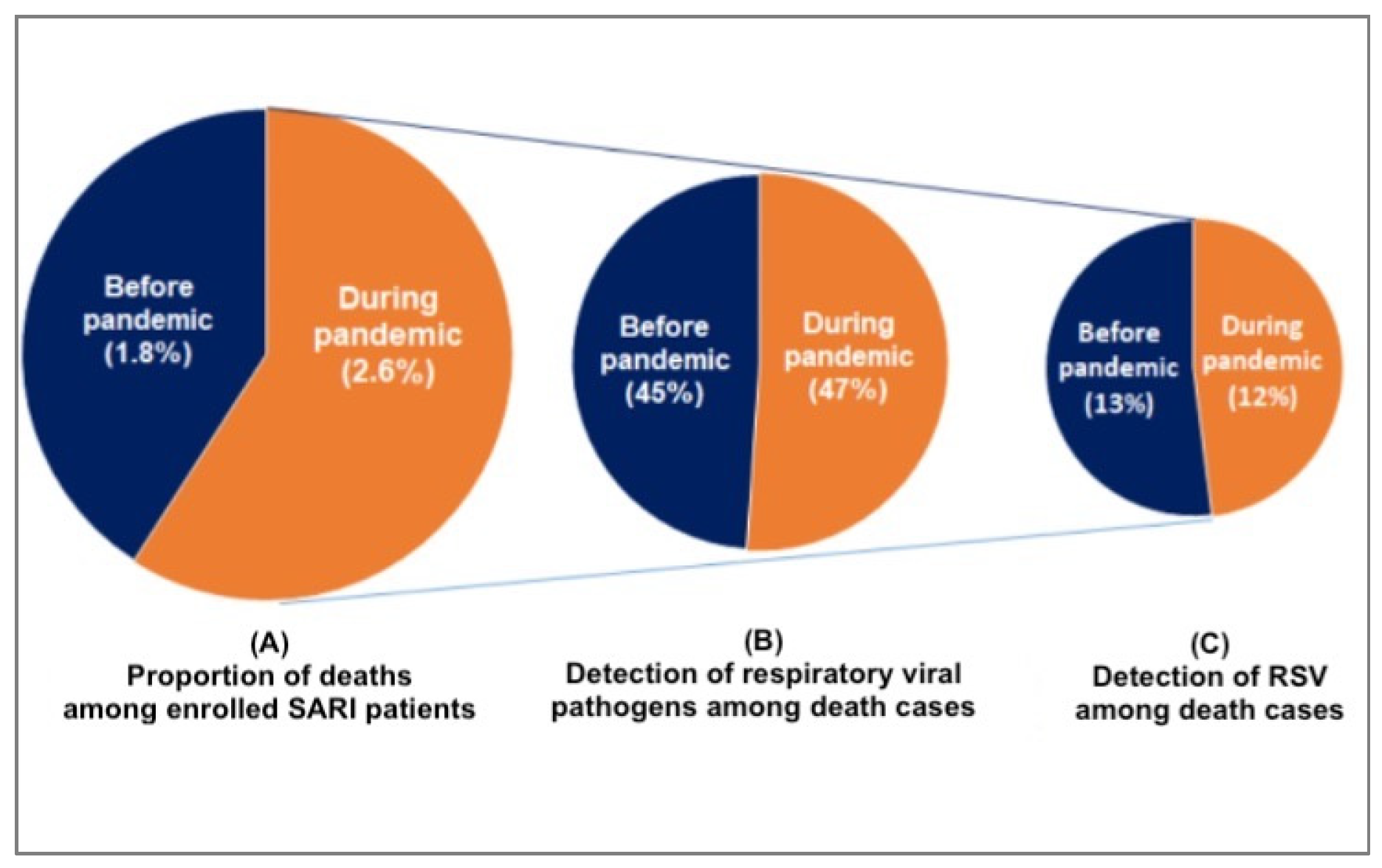

We found that compared to the pre-pandemic period, the proportion of SARI deaths at the time of the pandemic was higher [((1.8%, 159) vs. 2.6%, 66); p<0.001]. During the pre-pandemic period, 45% (71 /159) of the death cases revealed respiratory viruses whereas it was 47% (31 /66) during the pandemic (

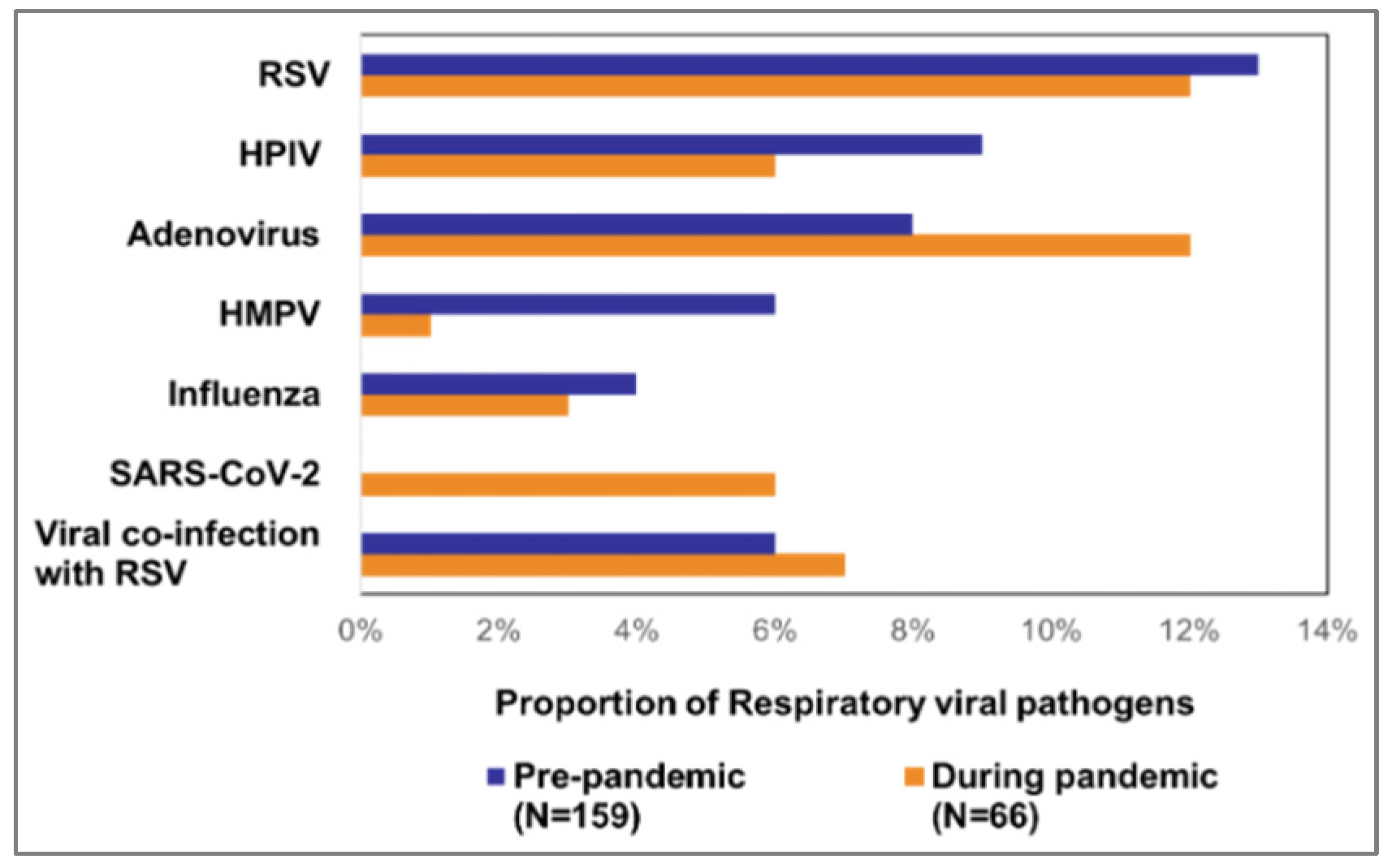

Figure 2). Of 159 pre-pandemic deaths, RSV was predominantly detected (13%, 20). The other findings included adenovirus (8%, 12), HPIV (9%, 14), HMPV (6%, 10), and influenza (4%, 6). 9 (6%) death cases detected viral co-infections including 3 (2%) co-infections with RSV. During the pandemic period, RSV (12%, 8) as well as adenovirus (12%, 8) comprised the largest proportions of the 66 pandemic deaths. The other detected viruses were SARS-CoV-2 (6%, 4), HPIV (6%, 4), influenza (3%, 2), HMPV (1%, 2). We also detected co-infection with RSV and adenovirus (3%, 2) and with HPIV and adenovirus (3%, 2) (

Figure 3).

3.3. Characteristics of RSV-associated SARI deaths among under-five children before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were 20 recorded deaths in children under the age of 5 years attributed to severe acute respiratory syndrome associated with RSV. The median age of these cases was 3.5 months (interquartile range, IQR: 2.3–6 months), and 65% of the cases were male (13/20). Of these cases, 85% (17/20) were children aged <1 year and 65% (13/20) were aged < 6 months. Co-morbid conditions were present in 10% of the cases (2/20).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there were 8 deaths in under 5-year-olds associated with RSV-SARI. Median age for these cases was 7.5 months (IQR: 2.5–13.5 months), and 25% were male (2/8). Among these cases, 75% (6/8) were children under 1 year of age, 38% (3/8) were under 6 months of age, and 13% (1/8) had at least one co-morbid condition.

RSV was solely detected in 57% (16) of the <6 months old, in 25% (7) of the 6-12 months old, in 11% (3) 1-2 years old and in 7% (2) of the 3-5 years old among all the death cases. All cases exhibited a history of breathing difficulty.

4. Discussion

Our study showed that both in pre-pandemic and pandemic periods, RSV was the major contributor to deaths among young children with SARI. Notably, we observed that nearly half of all SARI-related deaths in under 5-year-old children were associated with various respiratory viral pathogens, with RSV consistently responsible for a substantial portion of these cases, exhibiting minimal variation between the two periods (pre-pandemic: 13%, during pandemic: 12%). These findings underscore the urgency of implementing measures to prevent vaccine-preventable deaths.

Our study, as far as we are aware, represents the first of its kind in Bangladesh, concentrating exclusively on mortality among children under the age of five linked to RSV. A prior study conducted in Bangladesh revealed a surge in unclassified pneumonia-related deaths (64%) in children <2 years during the peak seasons of bronchiolitis [

9]. Estimating RSV-related mortality in Bangladesh has proven challenging, primarily due to the absence of comprehensive, long-term systematic surveillance [

10].

Our ongoing surveillance platform, hospital-based influenza surveillance (HBIS), has been consistently monitoring data both before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This platform enables us to systematically analyze deaths attributed to RSV and all respiratory viruses in a comprehensive manner. The findings from our study underscore the necessity for continued surveillance and further research to investigate the underlying factors associated with RSV-related mortality and to identify effective strategies for preventing childhood RSV infections and deaths in Bangladesh.

The study reveals a slight decrease in the total number of RSV-associated deaths among children under five years old with SARI during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previously, RSV-related deaths accounted for 20 out of 159 (13%) of all deaths, but during the pandemic, this figure slightly decreased to 8 out of 66 (12%). It’s worth noting that the total number of SARI patients in children under five also decreased during this period. This trend of reduced RSV-associated morbidity and mortality during the pandemic has been observed in several other countries, including China [

11], Austria [

12], France [

13], Brazil [

14] and globally [

15,

16,

17].

Apart from the concept of viral interference, the non-pharmacological interventions (NPIs) enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the use of face masks, frequent handwashing, social distancing, and lockdowns, may have played a role in lower circulation of RSV. When compared to the pre-pandemic period, our research indicates a shift in the median age of RSV-related deaths among children under five, increasing from 3.5 months (IQR 2.3-6) to 7.5 months (IQR 2.5-13.5) during the pandemic. The proportion of deaths due to RSV among children aged under six months decreased from 65% before the pandemic to 38% during the pandemic. This suggests that a higher percentage of older children, primarily over 6 months old, were succumbing to RSV infections during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period. A study in France also reported a similar increase in the median age of RSV admissions among children [

18].

Various studies worldwide have reported that the decline or near absence of RSV cases was followed by a delayed seasonal resurgence, accompanied by an increase in the median age of infection and death. We attribute this phenomenon to a significant cohort of older children who remained immunologically vulnerable due to the NPIs during the COVID-19 pandemic, and later, when these measures were relaxed, they came into contact with the virus [

11,

19,

20,

21]. To combat emerging RSV epidemics, in addition to promoting personal hygiene practices and social distancing for sick individuals, future preventive measures, such as infant monoclonal antibody prophylaxis and RSV vaccination for mothers should be evaluated to combat these premature deaths.

We observed that the presence of co-morbid conditions was 10% (2/20) before the pandemic and 13% (1/8) during the pandemic. Notably, a history of breathing difficulty was a common feature among children under five upon hospitalization. Due to the limited number of deaths, conducting a risk factor analysis was not feasible. However, future work should consider such analysis using a larger cohort and develop risk detection or prediction models to predict unfavorable outcomes. In resource-constrained settings like ours, the creation and utilization of clinical prediction tools can facilitate early disease severity detection, aid in diagnosis and prognosis, and offer clinical decision support [

22,

23].

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, we only tested the SARI-death cases. To have a better understanding of the seasonality of RSV and the impact of COVID-19 on the seasonality and circulation of RSV, we need continuous year-round geographically representative surveillance. Secondly, we only used data from our hospital-based SARI surveillance and likely missed RSV cases that are non-SARI or non-medically attended due to healthcare-seeking behavior where only 34% of the population receives healthcare from trained medical personnel [

24]. We were also unable to do a risk factor analysis due to the low number of deaths captured through the hospital-based SARI surveillance system. Community-based surveillance can provide a more accurate insight into the RSV circulation and burden in Bangladesh.

5. Conclusions

Both before and during the pandemic periods, RSV was a significant factor leading the under-five children with SARI to mortality in Bangladesh. Evidence-based measures such as monoclonal antibody prophylaxis for infants and RSV vaccination for mothers should be evaluated. These preventive interventions may help us combat these unexpected premature deaths in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MZH, MAI and FC; methodology, MZH, MAI, SH, TS, FC; software, MZH, MAI, SH.; validation, MZH, MAI, SH, TS and FC; formal analysis, MZH, MAI.; investigation, MZH, MAI, SH, TS, and FC; resources, MZH, MAI; data curation, MZH and MAI; writing—original draft preparation, MZH, SH; writing—review and editing, MAI, SH, TS, FC; visualization, MZH, MAI; supervision, TS, FC; project administration, MZH, MAI, FC; funding acquisition, MZH, MAI, FC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia, USA, grant number [U01GH002259]. The APC was funded by the US CDC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Institutional Review Board of icddr,b.

Informed Consent Statement

The legal guardians of the under-five children provided informed written consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available to ensure the protection of privacy.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge surveillance physicians, collaborators at the hospitals, and field staff for their continuous support. We are grateful to the study participants for their time. Hospital-based influenza surveillance was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, USA, under cooperative agreement number U01GH002259. icddr,b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of CDC to its research efforts. icddr,b is grateful to the Governments of Bangladesh and Canada for providing core/unrestricted support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hall, C.B. Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Parainfluenza Virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 1917–1928. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.B. Nosocomial Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections: The "Cold War" Has Not Ended. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 31, 590–596. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Blau, D.M.; Caballero, M.T.; Feikin, D.R.; Gill, C.J.; A Madhi, S.; Omer, S.B.; Simões, E.A.F.; Campbell, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 2047–2064. [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; McAllister, D.A.; O’Brien, K.L.; Simoes, E.A.F.; Madhi, S.A.; Gessner, B.D.; Polack, F.P.; Balsells, E.; Acacio, S.; Aguayo, C.; et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet 2017, 390, 946–958. [CrossRef]

- Nasreen, S., et al., Population-based incidence of severe acute respiratory virus infections among children aged <5 years in rural Bangladesh, June-October 2010. PLoS One, 2014. 9(2): p. e89978. [CrossRef]

- Agha, R.; Avner, J.R. Delayed Seasonal RSV Surge Observed During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics 2021, 148, 2021052089. [CrossRef]

- Chow, E.J.; Uyeki, T.M.; Chu, H.Y. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on community respiratory virus activity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 21, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gao, J.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W. Changes of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children before and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Henan, China. J. Infect. 2022, 86, 154–225. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, A.L., A.F. Rahman, and A. Rahman, ARI situation in our country: aren’t we oblivious of bronchiolitis in Bangladesh? Mymensingh medical journal : MMJ, 2009. 18(1 Suppl): p. S50-55.

- Stockman, L.J.; Brooks, W.A.; Streatfield, P.K.; Rahman, M.; Goswami, D.; Nahar, K.; Rahman, M.Z.; Luby, S.P.; Anderson, L.J. Challenges to Evaluating Respiratory Syncytial Virus Mortality in Bangladesh, 2004–2008. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e53857. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Xu, M.; Cao, L.; Su, L.; Lu, L.; Dong, N.; Jia, R.; Zhu, X.; Xu, J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of respiratory viruses in children with lower respiratory tract infections in China. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Redlberger-Fritz, M., et al., Significant impact of nationwide SARS-CoV-2 lockdown measures on the circulation of other respiratory virus infections in Austria. J Clin Virol, 2021. 137: p. 104795. [CrossRef]

- Angoulvant, F.; Ouldali, N.; Yang, D.D.; Filser, M.; Gajdos, V.; Rybak, A.; Guedj, R.; Soussan-Banini, V.; Basmaci, R.; Lefevre-Utile, A.; et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: Impact Caused by School Closure and National Lockdown on Pediatric Visits and Admissions for Viral and Nonviral Infections—a Time Series Analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, 319–322. [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, F.; Ongaratto, R.; Scotta, M.C.; Veras, T.N.; Stein, R.T.; Lumertz, M.S.; Jones, M.H.; Comaru, T.; Pinto, L.A. Early Impact of Social Distancing in Response to Coronavirus Disease 2019 on Hospitalizations for Acute Bronchiolitis in Infants in Brazil. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, 2071–2075. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, A.C., et al., The Effect of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Mitigation Strategies on Seasonal Respiratory Viruses: A Tale of 2 Large Metropolitan Centers in the United States. Clin Infect Dis, 2021. 72(5): p. e154-e157. [CrossRef]

- Van Brusselen, D., et al., Bronchiolitis in COVID-19 times: a nearly absent disease? Eur J Pediatr, 2021. 180(6): p. 1969-1973. [CrossRef]

- Di Mattia, G., et al., During the COVID-19 pandemic where has respiratory syncytial virus gone? Pediatr Pulmonol, 2021. 56(10): p. 3106-3109. [CrossRef]

- Fourgeaud, J.; Toubiana, J.; Chappuy, H.; Delacourt, C.; Moulin, F.; Parize, P.; Scemla, A.; Abid, H.; Leruez-Ville, M.; Frange, P. Impact of public health measures on the post-COVID-19 respiratory syncytial virus epidemics in France. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect Dis. 2021, 40, 2389–2395. [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, U.; Hartling, U.B.; Nielsen, J.; Vestergaard, L.S.; Dungu, K.H.S.; Nielsen, J.S.A.; Sellmer, A.; Matthesen, A.T.; Kristensen, K.; Holm, M. Hospital admissions and need for mechanical ventilation in children with respiratory syncytial virus before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Heal. 2023, 7, 171–179. [CrossRef]

- Dolores, A., et al., RSV reemergence in Argentina since the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J Clin Virol, 2022. 149: p. 105126. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.; Sinharoy, A.; Gope, S. The Influence of COVID-19 on Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Virus Activities. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2022, 14, 134–141. [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, M., et al., Bronchiolitis Score of Sant Joan de Deu: BROSJOD Score, validation and usefulness. Pediatr Pulmonol, 2017. 52(4): p. 533-539. [CrossRef]

- Mount, M.C.; Ji, X.; Kattan, M.W.; Slain, K.N.; Clayton, J.A.; Rotta, A.T.; Shein, S.L. Derivation and Validation of the Critical Bronchiolitis Score for the PICU. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 23, e45–e54. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.J.; Ferdousi, M.J.; Siddique, A.B.; Tipu, S.M.M.U.; Qayyum, M.A.; Laskar, M.S. Self-reported health problems, health care seeking behaviour and cost coping mechanism of older people: Implication for primary health care delivery in rural Bangladesh. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 1209–1215. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).