1. Introduction

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a widely used noninvasive technique for monitoring brain activity with millisecond-level temporal resolution. Owing to its portability and cost-effectiveness, EEG has become indispensable in brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) [

1], neuroscientific studies [

2], and clinical applications [

3]. However, EEG recordings are characterized by low-amplitude neural signals and are frequently corrupted by diverse artifacts and interferences, such as power-line noise, electromyographic (EMG) activity, and electrooculographic (EOG) artifacts. These contaminations substantially overlap with neural components in both time and frequency domains, leading to low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and limiting robust deployment of EEG systems beyond controlled laboratory settings [

4]. Importantly, for neuroengineering applications, the ultimate goal is not merely to “clean” waveforms, but to obtain task-relevant and noise-robust representations that generalize across subjects, sessions, and acquisition conditions.

In response to this challenge, EEG denoising and robustness modeling have experienced several paradigm shifts. Earlier studies predominantly followed prior-/model-driven signal processing pipelines, where artifacts are mitigated by enforcing explicit assumptions about signal generation and separability. Typical techniques include blind source separation (BSS) methods that exploit statistical structure across channels, such as Independent Component Analysis (ICA) and Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), as well as adaptive decomposition methods, such as Wavelet Transform and Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD), which are often effective for certain non-stationary components. Despite clear theoretical foundations, these approaches can be sensitive to assumption violations (e.g., limited channel count, multisource superposition, and strong non-stationarity) and to expert choices in parameterization and component selection, which may hinder robustness and reproducibility across datasets.

More recently, data-driven approaches have demonstrated significant potential in EEG processing by learning artifact suppression and robustness patterns directly from data. Supervised neural models, such as CNN-based and GAN-based methods, were pioneers in enabling end-to-end modeling for complex artifacts [

5]. However, many supervised denoising settings require paired targets (either curated or synthetically generated), while truly “clean” EEG is virtually unattainable in practical scenarios [

6], and synthetic corruption may not faithfully capture real-world artifact distributions. In parallel, another line of work emphasizes learning artifact-robust features for downstream tasks rather than optimizing a standalone denoising objective, where artifact suppression is achieved through representation learning and decoding optimization. Nevertheless, these paradigms still face limitations: their effectiveness is contingent upon how well the learned representations capture the intrinsic structure of neural signals, and under substantial inter-subject variability or extremely low SNR, it remains challenging to balance artifact suppression with the preservation of discriminative neural information.

The advent of self-supervised learning (SSL) has introduced a new data-driven paradigm for addressing data scarcity by autonomously generating supervision signals through pretext objectives, such as masked reconstruction and contrastive learning [

7,

8]. Its principal advantage lies in its ability to uncover latent structure and derive robust EEG representations from large-scale unlabeled data, thereby improving transferability across tasks and datasets. SSL has developed two dominant families: generative SSL, which emphasizes signal recovery/reconstruction to capture intrinsic temporal dependencies, and contrastive SSL, which enhances feature discriminability by constructing positive and negative pairs through physiology-inspired data augmentation. Transformer architectures further strengthen long-range dependency modeling and facilitate cross-scenario adaptation. Trained on large-scale and diverse datasets, SSL-based EEG encoders have increasingly served as general-purpose representation extractors for tasks such as motor imagery decoding, abnormal EEG detection, and event-related potential analysis. At the same time, SSL representations are influenced by the input distribution shaped by preprocessing; consequently, classical preprocessing may either complement SSL by stabilizing learning or interfere by distorting informative structures in a task-dependent manner. This motivates a systematic investigation of the synergy between preprocessing strategies and SSL-based EEG representation learning.

In response to rapid advances, there is still a lack of a comprehensive framework that integrates the full methodological spectrum from prior-/model-driven pipelines to modern data-driven representation learning, and clarifies their connections and boundaries under different application scenarios. Existing reviews predominantly focus on either traditional methodologies [

9] or deep learning [

10]. While some studies have recognized the emergence of transformers in EEG representation learning, they have not thoroughly examined the evolution, variants, and cross-architecture fusion modes spanning CNN, GAN, and Transformer paradigms [

11,

12]. Moreover, standardized empirical evidence remains limited regarding when classical preprocessing is beneficial (or detrimental) to modern SSL encoders across heterogeneous downstream tasks. There is therefore an urgent need for a review that systematically consolidates these paradigms and provides actionable guidance grounded in reproducible evaluation.

To address this gap, this study proposes a dual-path analysis framework centered on preprocessing-centric artifact mitigation and representation-learning-centric robustness. Within this framework, we systematically delineate the evolution of key techniques from traditional signal processing to deep learning and self-supervised learning and clarify their underlying assumptions and adaptation relationships. Furthermore, we quantify the impact of classical preprocessing on SSL performance through standardized experiments, aiming to provide practical guidance for method selection and future research directions in neuroengineering applications.

1.1. Contributions and Overview

To systematically sort out the technical context of EEG signal denoising and feature representation and provide empirical references for future research, the core contributions of this study are as follows:

Systematic synthesis of methods and applicability. We present a unified survey organized along two complementary routes—preprocessing for artifact mitigation and representation learning for robustness—covering prior-/model-driven signal processing, supervised data-driven models, and self-supervised learning.

Quantified synergistic effects. Under a standardized experimental protocol, we quantify how representative traditional preprocessing modules interact with SSL encoders across downstream tasks, showing strong task dependence and providing empirical evidence for practical use.

Practical guidelines and future directions. We provide a compact checklist to support task- and data-adaptive pipeline selection, and discuss open challenges and research directions toward hybrid frameworks that integrate signal-processing priors with self-supervised models.

1.2. Paper Organization

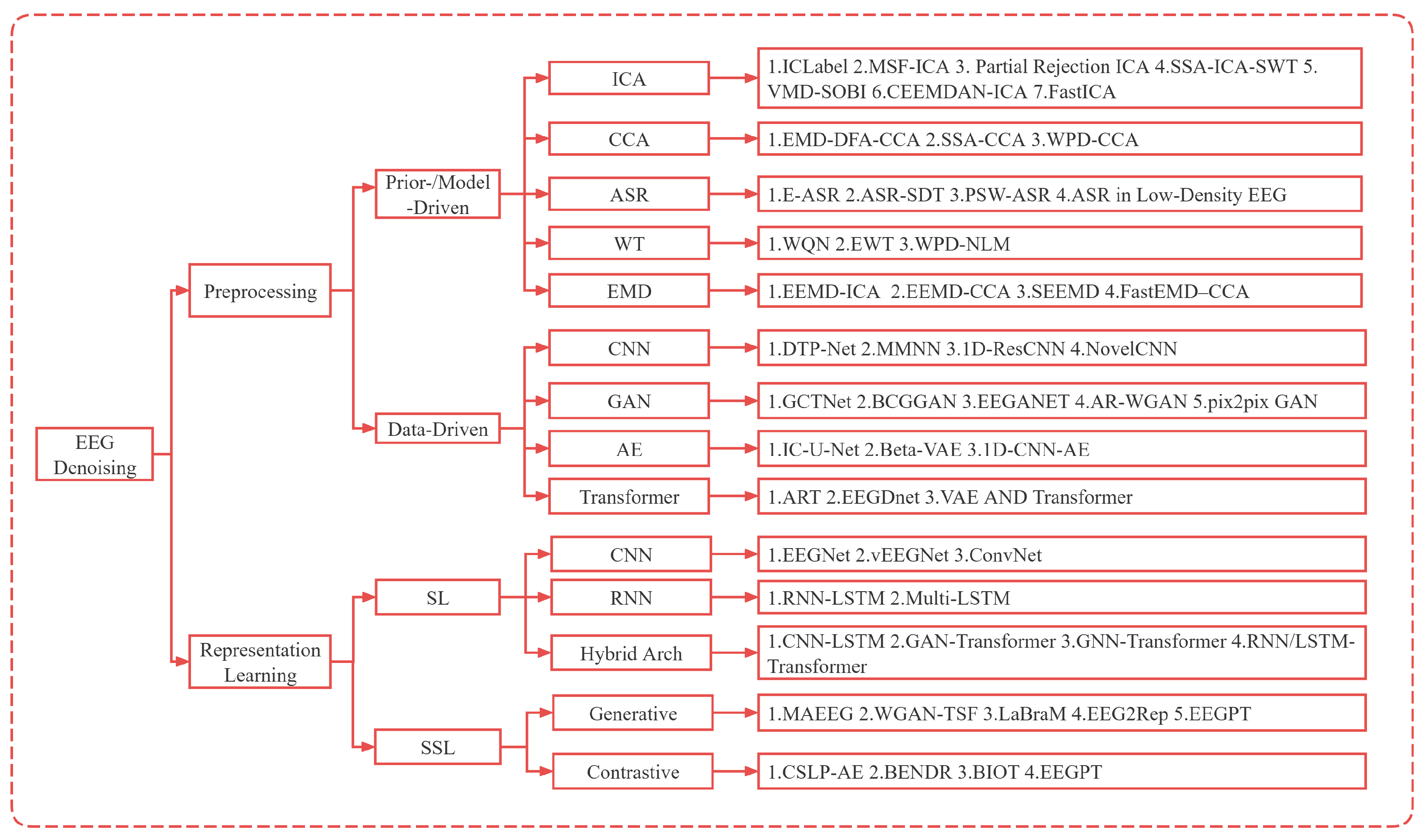

This paper seeks to systematically delineate the progression of EEG artifact mitigation and feature representation technologies by organizing them according to technical logic and application relevance. The structure of this paper is as follows: Section II elaborates on preprocessing-centric methods, covering both prior-/model-driven signal processing and data-driven preprocessing models; Section III introduces representation-learning-centric robustness, focusing on supervised and self-supervised paradigms; Section IV examines the synergy between classical preprocessing and self-supervised learning through standardized experiments; Section V discusses current challenges and provides practical guidelines for preprocessing–SSL pipeline selection; and Section VI concludes the paper. The detailed framework is depicted in

Figure 1.

2. Preprocessing-Centric Artifact Mitigation

Preprocessing-centric artifact mitigation aims to improve EEG signal quality before downstream modeling by attenuating artifacts and interferences at the input level. This route remains widely adopted in practice due to its modularity (easy to plug into existing pipelines), controllability (artifact attenuation can be tuned), and relatively clear neurophysiological interpretability in many scenarios. In this section, we review preprocessing-centric methods under a unified framework aligned with

Figure 1, covering both prior-/model-driven signal processing techniques and data-driven preprocessing models.

Specifically, prior-/model-driven preprocessing methods design deterministic separation or filtering strategies based on explicit assumptions. In contrast, data-driven preprocessing methods learn artifact suppression transformations from data (typically via neural networks), offering stronger nonlinear modeling capacity but introducing new challenges such as target definition (what constitutes “clean” EEG), controllability, and generalization to unseen artifact distributions. We summarize both families below.

2.1. Prior-/Model-Driven Preprocessing Methods

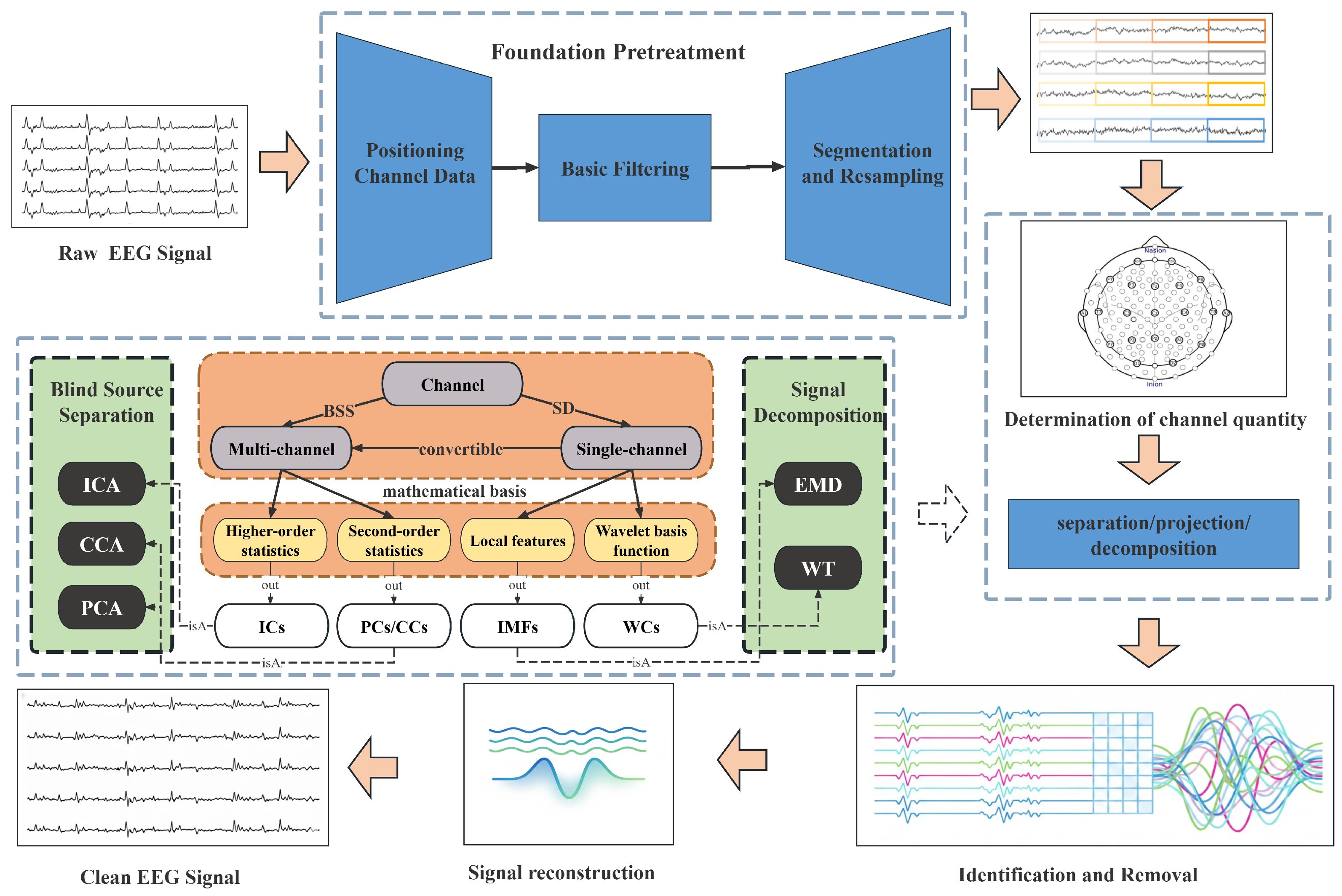

Prior-/model-driven preprocessing methods exploit time–frequency characteristics and statistical properties of EEG and perform artifact attenuation through deterministic algorithms. They are often computationally efficient, amenable to real-time use, and do not require large labeled datasets. As illustrated in

Figure 2, these methods can be broadly categorized into two groups: (i) blind source separation, which is particularly suitable for multi-channel physiological artifacts, and (ii) signal decomposition/transform-domain techniques, which are widely used for nonstationary noise and transient artifacts.

2.1.1. Blind Source Separation

This class of methods assumes that the underlying source signals are statistically independent, and separates neural activity and various noise components from multichannel mixed EEG. It is particularly suitable for removing physiological artifacts from multichannel recordings. Core techniques include Independent Component Analysis (ICA), Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), and Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Independent Component Analysis (ICA) is a milestone technique in this field. Vigario et al.[

13] were among the first to apply ICA for artifact removal, decomposing EEG into statistically independent components (ICs), then manually identifying and discarding artifact-dominated components before reconstructing the signal. However, traditional ICA exhibits three major limitations: (1) the identification of artifact ICs relies on expert experience, (2) it is not directly applicable to single-channel data, and (3) its performance is sensitive to the assumption of source independence[

14,

15]. Subsequent research has developed along two main directions. The first is the automated IC classification. For example, Pion-Tonachini et al.[

16] proposed the ICLabel model, a classifier trained on large-scale datasets that automatically labels ICs into seven categories: Brain, Muscle, and Eye. The binary to seven-class classification accuracy ranges from 87.0% to 59.7%, substantially reducing manual effort. Recent studies have also focused on ocular artifacts—one of the predominant physiological artifacts—and proposed “partial rejection” ICA strategies that selectively attenuate ocular components instead of removing them entirely[

17,

18]. Second, adaptation to single-channel data: methods such as Singular Spectrum Analysis (SSA), Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD), and Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (CEEMDAN) are used to decompose single-channel signals into multiple subcomponents, forming virtual multichannel data. ICA is then applied to these virtual channels to separate the artifacts [

19,

20,

21].

Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), as a blind source separation technique based on second-order statistics, separates noise sources by maximizing the autocorrelation of signals across time windows. Multiple studies have shown that CCA-based methods consistently outperform ICA-based methods in removing electromyographic (EMG) artifacts [

13]. However, CCA is constrained by its requirement for signal stationarity, and its computational complexity increases significantly with the number of channels. To address these issues, existing research often adopts a “single-channel decomposition–multichannel reconstruction” strategy to construct suitable inputs for CCA and overcome its application bottlenecks.For instance, Hossain et al.[

22] used Wavelet Packet Decomposition (WPD) to generate multichannel subbands and then applied CCA to further separate and remove motion artifacts. Feng et al.[

23] proposed an SSA-CCA framework, where SSA decomposes single-channel EEG into multiple reconstructed components (RCs) that are passed to CCA, enabling further separation and removal of EMG artifacts. In addition, hybrid CCA-based approaches for multi-artifact denoising have been explored. For example, Satyender et al. [

24] proposed the EMD-DFA-CCA framework, where EMD-DFA complements CCA by removing electrooculographic (EOG) artifacts.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a second-order statistics-based method for dimensionality reduction and decorrelation, and is often used as a preprocessing step for ICA. Recent work has been largely inspired by the Artifact Subspace Reconstruction (ASR) method, a PCA-based statistical technique for removing large-amplitude artifacts. Studies have demonstrated that by integrating signal decomposition techniques such as Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD), Wavelet Transform (WT), and SSA, ASR can be effectively adapted to single-channel EEG and achieve better performance than traditional ICA [

25]. Further optimizations include parameter-tuning strategies specific to low-density EEG systems [

26], the incorporation of Hebbian/anti-Hebbian learning networks for self-organized updating of the artifact subspace [

27], and embedded ASR (E-ASR), which converts single-channel EEG into multichannel matrices via dynamic embedding [

28]. These advances highlight the broad application potential of ASR in portable brain–computer interface (BCI) systems.

2.1.2. Signal Decomposition

Signal decomposition methods adaptively decompose nonstationary EEG signals into subcomponents at different scales, and selectively discard those dominated by noise. They are particularly suitable for handling nonstationary interference, such as power-line noise and motion artifacts. Core techniques include Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) and its variants, as well as wavelet transform and wavelet packet decomposition.

Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD). The Method decomposes signals into a finite number of Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) through an iterative sifting process, thereby separating oscillatory modes at different temporal scales. Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD), a noise-assisted extension of EMD, adds Gaussian white noise to mitigate mode mixing and is better suited to nonstationary EEG processing. Research on EMD-related techniques exhibits a clear common pattern: EEMD (or its variants) serves as the core signal decomposition step, providing multiscale IMFs for subsequent Blind Source Separation (BSS) methods. Denoising is achieved through a ‘decomposition–artifact-related IMF selection–noise concentration–artifact separation and removal’ pipeline, with a consistent emphasis on balancing noise suppression and preservation of neural information. Specifically, Chen et al.[

29,

30] proposed a hybrid EEMD–CCA framework that first applies EEMD to obtain IMFs and then uses BSS to separate artifacts. This framework can effectively preserve neural oscillatory features, even under low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions. Dai et al. developed a serialized EEMD (sEEMD) approach based on signal serialization to improve EEMD efficiency for multichannel data and to provide CCA with IMFs that can be processed rapidly, thereby accelerating artifact removal and facilitating real-time BCI applications[

31]. Egambaram et al. [

32] proposed the FastEMD–CCA method, which improves EEMD’s interpolation scheme and stopping criteria to speed up decomposition and combines it with CCA for unsupervised ocular artifact removal. This method outperforms traditional filtering techniques in preserving signal integrity.

Wavelet transform, leveraging its joint time–frequency localization capability, suppresses high-frequency noise while preserving abrupt changes in EEG through the selection of appropriate wavelet bases and thresholding functions. In recent years, a variety of wavelet-based extensions have emerged and have demonstrated strong advantages in processing nonstationary EEG signals. Nayak et al.[

33] proposed the Empirical Wavelet Transform (EWT), which performs adaptive spectral segmentation to construct customized wavelet filter banks, achieving an SNR improvement of 28.26 dB in motion artifact removal. Phadikar et al.[

34] developed a hybrid Wavelet Packet Decomposition–Nonlocal Means (WPD-NLM) framework, where a metaheuristic algorithm is employed to automatically optimize parameters. This approach attains high structural similarity in muscle artifact removal. Dora et al. [

35] proposed Wavelet Quantile Normalization (WQN), which uses distribution-transport techniques to preserve the statistical properties of EEG and successfully restore the continuity of

rhythms during anesthesia monitoring.

2.2. Data-Driven Preprocessing Methods

In recent years, neural networks have enabled data-driven preprocessing for EEG artifact mitigation by learning nonlinear transformations that suppress artifacts under diverse conditions. Depending on the training protocol, these models may be optimized with paired supervision (often using synthetically corrupted signals or pseudo-clean references), weak/self-supervision, or hybrid objectives that combine reconstruction fidelity and perceptual/feature-level constraints. Compared with prior-driven pipelines, data-driven preprocessing can improve adaptability to complex artifact mixtures; however, it also raises practical concerns regarding the definition of training targets, robustness to distribution shift, and the risk of removing task-relevant neural components.

According to the backbone architecture, mainstream methods can be grouped into CNN-dominated models, GAN-based models, and autoencoder/transformer-based models. Their characteristics and reported evaluation results are summarized in

Table 1.

2.2.1. CNN-Dominated Denoising Models

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), relying on the characteristics of local connection, weight sharing, and parameter efficiency, are naturally compatible with the temporal attributes and local correlation of EEG signals. They serve as the core basic architecture in the field of EEG denoising, focusing on mining spatio-temporal local discriminative features while balancing the model complexity and denoising effect. In early representative works, the 1D-ResCNN model proposed by Sun et al. [

36] alleviated the gradient vanishing problem in deep networks through residual connections and used an end-to-end design to directly capture local waveform patterns from single-channel EEG, providing a feasible path for single-channel signal denoising. To meet the needs of specific artifact processing, Zhang et al. [

37] designed a dedicated CNN architecture for electromyographic (EMG) artifacts using multi-scale convolution kernels to separate high-frequency noise from effective EEG signals. In multichannel data processing scenarios, the multimodule neural network (MMNN) proposed by Zhang et al. [

38] further integrates the spatial topology information of electrode channels and strengthens the integrity of feature representation through multimodule collaborative learning. In recent years, cross-architecture fusion has become an important trend to overcome the limitation of the CNN’s local receptive field. The DTP-Net proposed by Pei et al. [

39] innovatively combines CNN with Transformer, realizing multi-scale feature reuse and global dependency modeling in the time-frequency domain, which provides a new paradigm for the performance optimization of CNN-based models.

2.2.2. GAN-Based Denoising Models

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), relying on the adversarial training mechanism between generators and discriminators, can learn the distribution differences between EEG signals and noise, and generate clean signals that conform to real neural activities, showing unique advantages in complex artifact removal scenarios. EEGANet, proposed by Sawangjai et al. [

40] is specially designed for electrooculographic (EOG) artifacts, capturing the essential differences between artifacts and neural signals through adversarial learning, and providing a targeted solution for specific physiological artifact removal. AR-WGAN, proposed by Dong et al. [

43] introduces the Wasserstein distance to optimize the training process, improving the training stability of the model in mixed scenarios of electromyographic (EMG) and electrooculographic (EOG) artifacts, and expanding the application scenarios of GAN models in multi-artifact joint processing. To address the insufficient accuracy and stability of existing methods under low signal-to-noise ratio conditions, Wang et al. [

44] proposed an improved GAN model based on the actual needs of brain-computer interface systems. Its generator integrates BiLSTM and LSTM to strengthen temporal dependency modeling, and the discriminator is based on a CNN to improve the feature discrimination ability, which can remove various physiological artifacts such as EOG and EMG. BCGGAN developed by Lin et al. [

46] focuses on Ballistocardiogram (BCG) artifacts in the simultaneous acquisition scenario of functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), and realizes targeted denoising through training on real-scenario data, filling the gap in noise processing during cross-modal simultaneous acquisition. The pix2pixGAN proposed by Wang et al. [

49] draws on the core idea of image translation, converting EEG denoising into a mapping task in the signal domain and providing a new technical path for the collaborative removal of multiple types of artifacts.

Table 1.

Data-Driven Denoising Method Based On Deep Learning

Table 1.

Data-Driven Denoising Method Based On Deep Learning

| Model |

Year |

Structure |

Artifacts |

Dataset |

Evaluation |

Code Link |

| 1D-ResCNN [36] |

2020 |

CNN+ResNet |

Multiple Artifacts |

PhysioNet |

SNR: 22.944, RMSE: 0.0858 |

None |

| EEGANet [40] |

2021 |

GAN |

EOG |

Multiple Real Datasets |

SNR: 3.247, RMSE: 3.6350, CC: 0.945 |

EEGANet |

| NovelCNN [37] |

2021 |

CNN |

EMG |

EEGdenoiseNet |

RRMSE: 0.4480, CC: 0.863 |

NovelCNN |

| IC-U-Net [41] |

2022 |

U-Net+ICA |

Multiple Artifacts |

Simulated Data |

SNR: 24.880, RMSE: 0.6320 |

IC-U-Net |

| MMNN [38] |

2022 |

CNN |

Multiple Artifacts |

EEGdenoiseNet |

RRMSE: 0.3295, CC: 0.927 |

MMNN |

| FrComp-CAE [42] |

2022 |

1D-CAE+TM+FrBP |

EMG |

Mendeley, Bonn |

SNR: 8.680, RMSE: 0.0900, CC: 0.930 |

None |

| AR-WGAN [43] |

2023 |

WGAN |

EMG, EOG |

EEGdenoiseNet |

RRMSE: 0.1760, CC: 0.726 |

None |

| ImprovedGAN [44] |

2022 |

GAN |

EOG, EMG |

EEGdenoiseNet |

RRMSE: 0.1590, CC: 0.915 |

None |

| GCTNet [45] |

2023 |

GAN |

Multiple Artifacts |

EEGdenoiseNet |

SNR: 12.141, RRMSE: 0.3080, CC: 0.925 |

None |

| BCGGAN [46] |

2024 |

GAN |

BCG |

Self-collected Data |

PTPR:1.203 |

None |

| Beta-VAE [47] |

2024 |

VAE |

Extreme Artifacts |

DEAP |

Gaussian/Popped MSE:0.0440 |

None |

| DCAE [48] |

2024 |

CAE |

Antagonistic noise |

ERN, MI |

- |

None |

| DTP-Net [39] |

2024 |

CNN+TRM |

Multiple Artifacts |

EEGdenoiseNet |

SNR: 14.312, RRMSE: 0.2342, CC: 0.981 |

DTP-Net |

| pix2pixGAN [49] |

2024 |

GAN |

EMG |

EEGdenoiseNet |

RRMSE: 0.5797, CC: 0.865 |

None |

| AT-AT [50] |

2025 |

AT+TRM |

EMG |

EEGdenoiseNet |

RRMSE: 0.5400, CC: 0.825 |

None |

2.2.3. Autoencoder and Transformer-Based Denoising Models

Autoencoders, relying on the core logic of encoding-decoding, are naturally suitable for unsupervised/semi-supervised denoising scenarios, and continue to expand their application value through architectural innovations: IC-U-Net proposed by Chuang et al. [

41] combines U-Net with ICA to achieve accurate separation of multiple artifacts; the fractional-order 1D CNN autoencoder designed by Nagar and Kumar [

42] extracts orthogonal domain sparse features using Tchebisef moments, and combines fractional-order hyperparameter optimization and model compression to efficiently remove electromyographic artifacts and adapt to resource-constrained devices; Beta-VAE by Mahaseni et al. [

47] strengthens latent code regularization through adjustable hyperparameters, specially optimizing extreme artifact processing; Ding et al. [

48] innovatively applied Denoising Convolutional Autoencoder (DCAE) to brain-computer interface adversarial defense, regarding adversarial perturbations as special noise, and improving system security through signal manifold mapping. Transformer, relying on the self-attention mechanism, efficiently captures the long-range temporal dependencies of EEG signals and cross-channel global correlations, breaking through the local receptive field limitation of traditional architectures: the AT-AT model by Choi et al. [

50] adopts an “Autoencoder-Targeted Adversarial Transformer" architecture, specifically handling electromyographic (EMG) artifacts. It can globally distinguish noise from effective signals without convolution and has excellent noise robustness. These two types of models are complementary and suitable for different scenarios—autoencoders excel in unsupervised reconstruction and lightweight deployment, while transformers are strong in global temporal modeling, jointly enriching the EEG denoising technology system.

However, data-driven preprocessing for EEG artifact mitigation still faces two major methodological challenges.

First, the definition of training targets and supervision bias remains unresolved. Many supervised denoising models are trained with “noisy–clean” pairs, yet truly artifact-free EEG is rarely available in practice. As a result, “clean” targets are often surrogate references—either synthetically generated signals or pseudo-clean signals produced by prior-/model-driven pipelines. This practice can bias learned mappings toward reproducing the characteristics (and failure modes) of the target-generating procedure, and it does not guarantee physiological fidelity even when waveform-level metrics improve.

Second, the denoising strength is often difficult to control and may remove task-relevant neural information. Compared with prior-/model-driven methods whose attenuation behavior can be tuned explicitly, neural models may exhibit limited transparency and calibratability in how much and which components are suppressed. In low-SNR conditions, they can over-smooth or over-denoise, potentially attenuating weak but informative neural oscillations and event-related patterns that are critical for downstream neuroengineering tasks. Consequently, improvements in signal-level measures (SNR or RMSE) do not necessarily translate to better decoding/detection performance, and may even reduce interpretability and clinical trust.

These limitations motivate complementary approaches that evaluate robustness from a representation-learning perspective and optimize for downstream objectives, which we review in the next section.

3. Representation-Learning-Centric Methods

Feature extraction is a core component of EEG analysis pipelines, aiming to transform raw signals into compact representations that support downstream tasks such as classification, detection, and state monitoring. Beyond improving waveform quality at the input level (

Section 2), representation-learning-centric approaches seek to learn

artifact-robust features such that nuisance variations caused by artifacts have reduced influence on the learned representations and task decisions. In this review, we use the term

representation denoising to refer to this family of methods where robustness to artifacts is achieved

jointly with feature learning and task optimization, rather than via a dedicated preprocessing module.

Notably, representation robustness is not always equivalent to signal-level denoising: a method may yield representations that are robust for a given task without producing visually “clean” waveforms, and improvements in SNR/RMSE do not necessarily translate to better downstream performance.

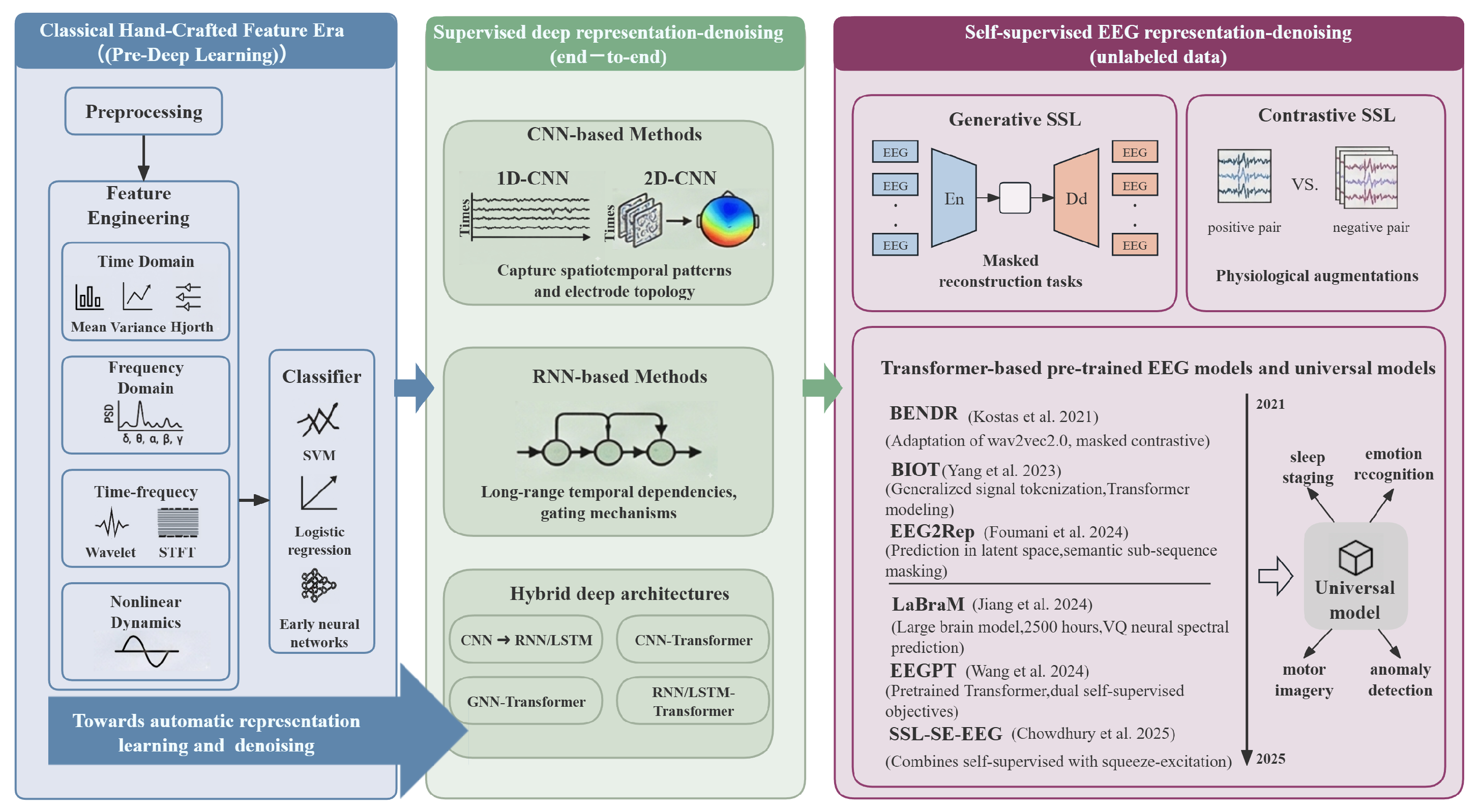

Figure 3 illustrates the evolution from handcrafted feature engineering to modern supervised and self-supervised representation learning paradigms.

Early studies mainly relied on signal processing techniques to manually construct features from multiple perspectives, including the time domain (mean, variance, Hjorth parameters [

51]), frequency domain (power spectral density of

,

,

,

,

rhythms [

52]), time–frequency domain (wavelet transform, short-time Fourier transform [

53,

54]), and nonlinear dynamics. Although these methods offer clear physiological interpretations and are computationally efficient, they suffer from notable limitations: their heavy dependence on expert knowledge leads to limited generalization and difficulty in capturing individual variability and complex patterns. More critically, handcrafted feature quality is often constrained by upstream preprocessing quality; residual artifacts can severely undermine feature discriminability, making the conventional two-stage pipeline of preprocessing-centric artifact mitigation followed by handcrafted feature engineering insufficient in challenging, low-SNR, or cross-subject settings.

Deep learning provides a key pathway for breaking this bottleneck by enabling automatic representation learning without manual feature engineering. By stacking nonlinear transformations and optimizing data-driven objectives, deep networks can learn task-adaptive features and, in many cases, attenuate nuisance variations associated with artifacts within the learned representations. However, such robustness is not guaranteed: without appropriate objectives, regularization, or pretraining, models may also exploit artifact-related spurious cues. We summarize these deep representation-learning approaches under the umbrella of representation denoising and review their implementation pathways, representative models, and EEG applications along two methodological branches: supervised learning and self-supervised learning [

55].

3.1. Supervised Representation Learning

In supervised deep representation learning, models are trained in an end-to-end manner using large quantities of EEG data with precise labels, learning direct mapping from input signals to task-specific outputs. During the process of minimizing the prediction error, the intermediate layers automatically acquire task-adaptive discriminative features while naturally filtering out components that are irrelevant to the labels. This constitutes an early core implementation paradigm for representation denoising [

56].

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs). By leveraging their local connectivity and weight-sharing properties, CNNs have become the cornerstone for extracting spatiotemporal EEG features [

57,

58,

59]. When processing EEG signals, one-dimensional CNNs can effectively capture local waveform patterns (such as event-related potential components or epileptiform discharges) from individual channels. Two-dimensional CNNs, by arranging multichannel EEG signals spatially into a “brain topographic map” or a time–channel “image,” can learn spatiotemporal features through convolutional kernels that jointly model temporal dynamics and spatial dependencies, thereby capturing spatial topologies and functional connectivity among different electrode sites [

60].

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their variants. Architectures such as long short-term memory (LSTM) networks and gated recurrent units (GRUs) [

61,

62] are particularly adept at modeling long-range temporal dependencies through their recurrent connections and gating mechanisms. This capability is especially important for tasks that require modeling of the duration and evolution of states, such as stage transitions in sleep staging [

63] or the complete dynamic process of epileptic seizures from onset and propagation to termination.

Hybrid architectures. Various hybrid architectures have been proposed to integrate the advantages of different model families and strengthen both feature expressiveness and noise filtering. Cascaded CNN–RNN models [

64] use CNNs to extract spatial features from multichannel signals, and LSTMs to learn temporal contextual dependencies. CNN–transformer hybrids employ serial and other fusion strategies tailored to the multidimensional spatiotemporal nature of EEG: CNNs capture local spatiotemporal patterns, such as electrode spatial topology and transient waveforms, while transformers model long-range dependencies through self-attention [

65,

66]. Since the advent of transformers, more cross-type hybrids have been developed. GAN–Transformer architectures exploit the strengths of generative adversarial networks in distribution modeling for EEG image reconstruction (rather than directly processing the signal domain), leveraging their ability to accurately generate and reconstruct image-level features. By performing adversarial training in the image domain to capture structural regularities in visualized EEG and combining this with transformers’ powerful long-range dependency modeling, these methods enable efficient feature extraction from EEG-derived images [

67,

68,

69]. GNN–Transformer models use graph neural networks to map EEG electrodes to graph nodes, precisely modeling spatial relationships and functional connectivity across brain regions, and then integrate transformers to capture long-range temporal dependencies, thereby jointly extracting spatial topologies and temporal dynamics to improve cross-channel information fusion in tasks such as emotion recognition and seizure prediction [

70,

71]. RNN/LSTM–Transformer hybrids combine the gated mechanisms of RNNs/LSTMs, which excel at modeling local short-term temporal dynamics and contextual relations, with transformers’ self-attention mechanisms that address the long-range dependency bottleneck, achieving a balance between fine-grained local details and global temporal structure in tasks such as sleep staging and cognitive impairment detection [

72,

73].

Despite the remarkable success of supervised learning methods, their performance relies heavily on a large amount of high-quality, fine-grained labeled data. In clinical medical scenarios, acquiring such data is typically costly, time-consuming, and susceptible to the subjectivity of annotators. This bottleneck significantly limits the application and generalization ability of supervised learning models in a wider range of scenarios.

Note: Cross-dataset generalization is based on conclusions from original studies. Code links refer to official repositories provided in the original papers; marked as “None" if not publicly available. Abbreviation: LSTE=Local Spatiotemporal Embedding; SSP=Semantic Subsequence Preservation.

3.2. Self-Supervised Representation Learning

Self-supervised representation-denoising methods do not require large amounts of human-annotated data. Instead, they designed pretext tasks that serve as proxy supervision signals and can be constructed automatically from large-scale unlabeled EEG, thereby driving models to learn the intrinsic structure and general representations of the data while performing noise filtering during feature learning. This paradigm elegantly overcomes the reliance of supervised representation denoising on labeled data and has become a research hotspot in recent years. The representative methods are summarized in

Table 2.

Early self-supervised approaches were extensively borrowed from mature techniques in computer vision and natural language processing, forming two major paradigms: generative and contrastive.

Generative approaches focus on reconstructing or recovering the signal itself, forcing the model to capture underlying data structures. Typical methods include masked reconstruction [

7] and signal-generation-based reconstruction [

81].

Contrastive approaches, by contrast, construct positive pairs via physiologically inspired data augmentation strategies in the time or frequency domains, and treat other signals as negative examples. This drives models to learn robust representations that are invariant to noise and individual variability [

74,

76,

82].

As research has progressed, transformer-based pre-trained models have opened up a new path for learning universal EEG representations. In 2021, Kostas et al.[

75] proposed BENDR, an early exploration that adapts the wav2vec 2.0 framework from speech recognition to EEG. BENDR applies masked contrastive learning over large-scale unlabeled EEG data and achieves strong cross-dataset generalization. Subsequently, Yang et al.[

66] proposed BIOT, which introduces a generalized signal tokenization scheme to represent EEG recordings with varying channels, lengths, and quality as “sentences,” followed by efficient transformer-based modeling. This study lays the groundwork for constructing flexible EEG foundation models.

In recent years, self-supervised learning has further evolved towards specialization, scale-up, and multi-task integration. To address inherent challenges in EEG, such as low signal-to-noise ratio and ambiguous semantic segmentation, Foumani et al.[

77] proposed EEG2Rep, which performs prediction in a latent representation space and introduces a semantic subsequence-preserving masking strategy. This guides the model to learn higher-level semantic features and significantly improves the performance on downstream tasks. Jiang et al.[

78] proposed LaBraM in May 2024, which, for the first time, pre-trains on approximately 2,500 h of large-scale EEG data using a vector-quantized neural spectral prediction objective, demonstrating the substantial potential of scaling both data and model size. To further enhance the representation quality, Wang et al. [

79] proposed EEGPT, which adopts a dual self-supervised mechanism that combines spatiotemporal representation alignment with masked reconstruction. By integrating the strengths of different self-supervised paradigms, EEGPT learns features that exhibit excellent generality and robustness in linear probing evaluations.

Other Learning Paradigms. Beyond the mainstream methods described above, several specialized learning paradigms offer innovative solutions to specific challenges in EEG analysis, such as individual variability, data scarcity, domain shifts, and feature redundancy. Unsupervised continual learning for individual adaptation dynamically balances model stability and plasticity, enabling rapid adaptation to new subjects without labels while avoiding catastrophic forgetting of previously acquired knowledge [

83,

84]. Reinforcement learning–based feature optimization formulates the extraction of critical information as a sequential decision problem, automatically selecting informative channels, key temporal segments, or feature dimensions, thereby reducing redundancy and enhancing model robustness [

85,

86]. Few-shot and meta-learning implement the principle of “learning to learn,” deriving generic learning rules from a large set of related tasks so that new tasks can be learned efficiently from only a handful of examples [

78,

87]. Unsupervised domain adaptation leverages techniques such as adversarial domain training, pseudo-labeling, and variational autoencoders to mitigate distributional shifts across subjects and sessions, thereby encouraging the learning of domain-invariant neural representations [

88,

89]. Collectively, these paradigms enrich the technical landscape of EEG representation learning from multiple perspectives and open new possibilities for robust deployment in complex real-world scenarios.

4. Synergy of Preprocessing and SSL

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has shown strong potential for EEG representation learning, yet its effectiveness can be sensitive to the input distribution shaped by preprocessing and recording quality. Prior-/model-driven preprocessing can attenuate artifacts and stabilize certain signal characteristics, but it may also distort subtle neural patterns or shift data statistics that pretrained encoders rely on. A practical open question is therefore: when does preprocessing complement SSL, and when does it conflict with it? To answer this question, we treat preprocessing as a plug-in module placed before the SSL encoder and quantify its impact on downstream transfer under a standardized protocol.

4.1. Datasets and Preprocessing

Three types of datasets covering different channel counts, signal qualities, and task types were selected for the experiments: PhysioNetMI [

90], TSUBenchmark [

91], and SEED [

92], which were used for model pre-training and performance verification to ensure the generality and representativeness of the experimental results. Three typical adjustable preprocessing technologies were selected: 1) ICA+ICLabel component selection, which controls denoising intensity by retaining independent components of different categories to efficiently remove physiological artifacts; 2) EEMD signal decomposition denoising, which realizes adaptive separation of non-stationary noise by adjusting parameters and retains the temporal characteristics of signals; and 3) wavelet threshold denoising, which balances noise suppression and transient feature retention by selecting appropriate wavelet bases and threshold rules, adapting to abnormal signal detection scenarios.

4.2. Implementation and Setup

EEGPT[

79] was used as the basic self-supervised model in the experiment. The downstream experimental datasets include the BCIC-2A/2 B datasets from BCI Competition IV (for motor imagery classification tasks) [

93,

94], PhysioNet P300 dataset (for event-related potential detection tasks) [

90], and TUAB dataset (for abnormal EEG detection tasks) [

95]. Four groups of comparative experiments were set up: raw data baseline (EEGPT standard preprocessing), ICA+ICLabel enhancement, EEMD enhancement, and wavelet threshold enhancement. Classification accuracy, weighted F1 score, AUC-ROC, and Cohen’s kappa coefficient were used as the core evaluation metrics. Combined with representation quality analysis and computational efficiency evaluation, each experiment was repeated four times, and the mean ± standard deviation was calculated to ensure the reliability of the results, systematically quantifying the synergistic value of different preprocessing strategies and self-supervised learning.

Table 3.

Comparison of Linear Detection Performance of Different Preprocessing Models on Downstream Tasks

Table 3.

Comparison of Linear Detection Performance of Different Preprocessing Models on Downstream Tasks

| Datasets |

Methods |

Balanced Accuracy |

Weighted F1 / AUROC |

Cohen’s Kappa |

| BCIC-2A |

Baseline |

|

|

|

| |

ICA+ICLabel |

|

|

|

| |

EEMD |

|

|

|

| |

Wavelet |

|

|

|

| BCIC-2B |

Baseline |

|

|

|

| |

ICA |

|

|

|

| |

EEMD |

|

|

|

| |

Wavelet |

|

|

|

| PhysioP300 |

Baseline |

|

|

|

| |

ICA+ICLabel |

|

|

|

| |

EEMD |

|

|

|

| |

Wavelet |

|

|

|

| TUAB |

Baseline |

|

|

– |

| |

ICA+ICLabel |

|

|

– |

| |

EEMD |

|

|

– |

| |

Wavelet |

|

|

– |

4.3. Results

Linear probing indicates that the effect of preprocessing on SSL representations is task- and dataset-dependent. For motor imagery (BCIC-2A/2B), preprocessing can help or hurt: ICA+ICLabel improves BCIC-2A but degrades BCIC-2B, while EEMD and wavelet thresholding are inconsistent, suggesting that aggressive or mismatched processing may suppress rhythm modulations. For ERP detection (PhysioNet P300), preprocessing is largely comparable to the EEGPT baseline, implying limited benefit for time-locked component–driven decoding. In contrast, for abnormal EEG detection (TUAB), all preprocessing methods yield consistent gains—most notably EEMD and wavelet thresholding—indicating that moderate time–frequency shaping can enhance pathology-related morphology/spectral cues in artifact-rich clinical recordings. Overall, preprocessing should be viewed as a task-adaptive design choice rather than a fixed front end when paired with SSL encoders.

5. Discussion

Centered on the objective of

suppressing artifacts across diverse scenarios while preserving task-relevant neural information, EEG denoising has evolved from prior-/model-driven signal processing to supervised data-driven models, and more recently to self-supervised pretraining and transfer learning. Early studies, represented by blind source separation and subspace-based techniques [

13,

16,

19,

21] and signal decomposition methods [

33,

34], mitigate artifacts by imposing explicit priors on source separability or time–frequency structure. These approaches are often computationally efficient and physiologically interpretable; however, their effectiveness can be sensitive to assumption violations, hyperparameter choices, and component/threshold selection, making it difficult to consistently balance artifact attenuation and information preservation under low-SNR recordings, mixed artifact conditions, or limited-channel settings.

Supervised deep learning introduced a data-driven route that learns nonlinear transformations for artifact suppression in an end-to-end manner [

36,

39,

40,

41,

43,

50]. While many methods achieve strong performance on benchmarks constructed with synthetic corruptions or pseudo-clean targets, they remain challenged by the scarcity and ambiguity of reliable training references, limited cross-subject/session generalization, and the lack of explicit controllability over the denoising–information-retention trade-off.

More recently, self-supervised pretraining frameworks [

7,

75,

78,

79] leverage objectives such as masked reconstruction and contrastive learning to learn transferable EEG representations from large-scale unlabeled data, alleviating label scarcity and improving task transfer. Nevertheless, SSL performance is sensitive to the input distribution shaped by preprocessing and augmentation design; under real-world conditions with extreme artifacts and pronounced inter-individual variability, achieving robust representations that both attenuate artifacts and preserve critical neural information

without over-reliance on labeled data remains a central open problem. Importantly, our standardized EEGPT-based evaluation suggests that the synergy between classical preprocessing and SSL is highly task-dependent, underscoring the need for principled guidelines rather than one-size-fits-all pipelines.

5.1. Challenges

Although EEG denoising methods have made notable progress in both theory and application, several key challenges remain before they can be transitioned from laboratory research to large-scale clinical and everyday applications.

5.1.1. Data Dilemma

Data-related issues remain fundamental bottlenecks for EEG denoising and representation learning [

6]. Supervised models typically require large-scale, high-quality datasets with accurate annotations; however, clinical labeling is time-consuming, costly, and subject to inter-rater variability, resulting in a persistent scarcity of labeled EEG data [

55]. Moreover, many supervised denoising settings rely on “noisy–clean” training pairs, whereas truly artifact-free EEG is rarely obtainable in real recordings. In practice, training targets are often constructed using synthetic corruptions or pseudo-clean references generated by prior-/model-driven preprocessing, which may introduce supervision bias and distribution mismatch.

Importantly, even for self-supervised learning (SSL) methods that do not require labels, performance can still be strongly affected by the quality of the input signals. In real-world settings, raw EEG often exhibits low SNR and diverse nonstationary artifacts, which can undermine training stability and the reliability of learned representations, especially when artifacts are consistently present and may be partially absorbed as signal.

5.1.2. Lack of Efficient Synergy Between Prior-Driven Preprocessing and Modern Representation Learning

There is a lack of generally applicable schemes for integrating prior-/model-driven signal processing with modern representation learning, particularly SSL. Prior-driven preprocessing aims to attenuate artifacts under explicit assumptions, whereas representation learning optimizes objectives that encourage invariances and preserve information useful for transfer. This objective mismatch can lead to adaptation conflicts: preprocessing may improve SNR for certain artifacts yet alter signal statistics or remove subtle patterns that are beneficial for representation learning, especially for nonstationary signals where aggressive smoothing can attenuate weak but informative neural activity.

More importantly, the effectiveness of different preprocessing–model combinations is highly dependent on data characteristics and downstream tasks. A strategy that improves motor imagery decoding may not benefit, and can even harm, abnormal EEG detection or other out-of-distribution settings. The field still lacks standardized guidelines and evaluation protocols to select appropriate combinations based on data properties and task demands [

89].

5.1.3. Challenges in Practical Deployment

The combined challenges of computational efficiency, generalization, and interpretability pose major obstacles to deploying EEG denoising and representation models as practical products or clinical tools [

23,

46]. First, many models incur high computational and memory costs, limiting real-time use on portable or embedded devices. Second, generalization remains difficult due to pronounced inter-subject and cross-session variability; performance often degrades when models are applied to new individuals, devices, or recording environments [

74,

83,

87]. Third, limited interpretability reduces clinical trust: black-box models make it difficult to relate learned features and decisions to concrete neurophysiological mechanisms, falling short of the requirement to not only predict accurately but also provide reasonable explanations [

51,

52].

5.2. Future Research Directions

To address these challenges, future research should focus on improving data utilization, enabling principled synergy between prior-driven preprocessing and SSL, and advancing subject-aware and deployment-friendly modeling.

5.2.1. Prior-Guided Self-Supervision and Weak Supervision

Prior-/model-driven methods can support efficient data utilization in two complementary ways. (i) As a scalable source of weak supervision, automated pipelines such as ICA with component labeling tools [

16,

19] can generate artifact annotations or pseudo-clean references to reduce the burden of manual labeling. (ii) As inductive biases for SSL, priors from decomposition and time–frequency analysis can be incorporated into masked reconstruction, contrastive objectives, or multi-view learning to guide models toward neural-activity-related structure rather than artifact regularities.

5.2.2. Multimodal Fusion

EEG can be jointly modeled with other physiological modalities (e.g., fNIRS, BCG, and other biosignals) to enhance robustness against artifacts and distribution shifts. Inspired by universal physiological tokenization [

66], multimodal learning can exploit complementary information across sensors to improve artifact detection and representation stability in low-SNR and low-label regimes.

5.2.3. Fine-Grained Subject- and Session-Aware Modeling

To improve cross-subject and cross-session generalization, future models should explicitly account for individual and session variability. Physiologically interpretable features [

51,

52] and source separation techniques such as ICA/CCA [

13,

23] can help characterize subject- or session-specific components, enabling the construction of “fingerprints” that can be used as conditional priors or auxiliary branches in SSL pretraining and downstream adaptation.

5.3. Practical Guidelines

We summarize actionable recommendations for selecting preprocessing and SSL strategies. The key takeaway is that preprocessing should be treated as a task-adaptive design choice and validated by downstream performance rather than signal-level metrics alone.

Task–data–constraint checklist.

Table 4 provides a compact checklist that maps common EEG task families to typical discriminative cues, the main risk of over-processing, and a recommended starting point.

Actionable rules

Use downstream metrics (Acc/F1/AUC/Kappa) as primary criteria; SNR/RMSE can be misleading.

Start from the baseline SSL pipeline and add preprocessing only when necessary; treat it as tunable.

Watch for distribution shift: strong preprocessing may reduce the usefulness of pretrained invariances.

For MI, reduce denoising strength if performance drops (risk of over-denoising task-relevant rhythms).

For ERP, prioritize temporal fidelity; avoid operations that alter waveform morphology/latency.

For abnormal detection, moderate stabilization can help, but report efficiency and generalization (subject/session/site).

6. Conclusions

In this survey, we proposed a two-level taxonomy for EEG denoising and representation learning, distinguishing (i) preprocessing-centric artifact mitigation versus representation-learning-centric robustness, and (ii) prior-/model-driven methods versus data-driven methods. We further quantified, under a unified protocol, how classical preprocessing interacts with EEGPT-based self-supervised learning across motor imagery classification, ERP detection, and abnormal EEG detection. Our results show that the benefit of combining preprocessing with SSL is strongly task- and data-dependent, suggesting that preprocessing should be treated as a task-specific design choice rather than a universal default.

Looking forward, key challenges remain in data availability and target definition, principled prior–SSL integration, and deployable robustness (generalization, interpretability, and efficiency). We expect future progress to come from prior-guided self-supervision and weak supervision, multimodal fusion, subject-/session-aware personalization, and lightweight deployment-oriented architectures.

References

- Yi, Z.; Pan, J.; Chen, Z.; Lu, D.; Cai, H.; Li, J.; Xie, Q. A hybrid BCI integrating EEG and Eye-Tracking for assisting clinical communication in patients with disorders of consciousness. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; Wu, Z.; Yue, Z.; Li, B.; Chen, Q.; Han, B. Prior Knowledge Uses Prestimulus Alpha Band Oscillations and Persistent Poststimulus Neural Templates for Conscious Perception. Journal of Neuroscience 2023, 43, 6164–6175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Wu, M.; Gao, J.; Lu, D.; Ding, Z.; Hu, B. An optimal channel selection for EEG-based depression detection via kernel-target alignment. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2020, 25, 2545–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthukumaraswamy, S.D. High-frequency brain activity and muscle artifacts in MEG/EEG: a review and recommendations. Frontiers in human neuroscience 2013, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Deng, F.; Jiang, P. EEGDiR: Electroencephalogram denoising network for temporal information storage and global modeling through Retentive Network. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 177, 108626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craik, A.; He, Y.; Contreras-Vidal, J. Deep Learning for EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interfaces: A Review. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2019, 30, 4–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, H.Y.S.; Goh, H.; Sandino, C.M.; Cheng, J.Y. Maeeg: Masked auto-encoder for eeg representation learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.02625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, S.; Wu, D.; Wu, X. Self-Supervised Learning with Adaptive Frequency-Time Attention Transformer for Seizure Prediction and Classification. Brain Sciences 2025, 15, 382. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, F. A review of epilepsy detection and prediction methods based on EEG signal processing and deep learning. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2024, 18, 1468967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pup, F.; Zanola, A.; Tshimanga, L.F.; Bertoldo, A.; Atzori, M. The more, the better? Evaluating the role of EEG preprocessing for deep learning applications. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Xun, G.; Jia, K.; Zhang, A. A multi-view deep learning framework for EEG seizure detection. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics 2018, 23, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Zhu, K. Eeg-fm-bench: A comprehensive benchmark for the systematic evaluation of eeg foundation models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.17742. [Google Scholar]

- Vigário, R.N. Extraction of ocular artefacts from EEG using independent component analysis. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology 1997, 103, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mognon, A.; Jovicich, J.; Bruzzone, L.; Buiatti, M. ADJUST: An automatic EEG artifact detector based on the joint use of spatial and temporal features. Psychophysiology 2011, 48, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburro, G.; Fiedler, P.; Stone, D.; Haueisen, J.; Comani, S. A new ICA-based fingerprint method for the automatic removal of physiological artifacts from EEG recordings. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pion-Tonachini, L.; Kreutz-Delgado, K.; Makeig, S. ICLabel: An automated electroencephalographic independent component classifier, dataset, and website. NeuroImage 2019, 198, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Molina, M.; Tardón, L.J.; Barbancho, A.M.; Barbancho, I. Implementation of tools for lessening the influence of artifacts in EEG signal analysis. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, A.; Tardón, L.J.; Barbancho, I.; Barbancho, A.M.; Brattico, E.; Haumann, N.T. Preprocessing for lessening the influence of eye artifacts in EEG analysis. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorbasha, S.K.; Sudha, G.F. Removal of EOG artifacts and separation of different cerebral activity components from single channel EEG—An efficient approach combining SSA–ICA with wavelet thresholding for BCI applications. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2021, 63, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, C. Remove artifacts from a single-channel EEG based on VMD and SOBI. Sensors 2022, 22, 6698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Yan, Z.; Fu, W. Electroencephalogram artifact filtering method of single channel EEG based on CEEMDAN-ICA. Chin. J. Sens. Actuators 2018, 31, 1211–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.S.; Chowdhury, M.E.; Reaz, M.B.I.; Ali, S.H.M.; Bakar, A.A.A.; Kiranyaz, S.; Khandakar, A.; Alhatou, M.; Habib, R.; Hossain, M.M. Motion artifacts correction from single-channel EEG and fNIRS signals using novel wavelet packet decomposition in combination with canonical correlation analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 3169. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, A.; Qian, R.; Chen, X. A novel SSA-CCA framework for muscle artifact removal from ambulatory EEG. Virtual Reality & Intelligent Hardware 2022, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhull, S.K.; Singh, K.K.; et al. EEG artifact removal using canonical correlation analysis and EMD-DFA based hybrid denoising approach. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 218, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaongoen, N.; Jo, S. Adapting Artifact Subspace Reconstruction Method for SingleChannel EEG using Signal Decomposition Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2023 45th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), 2023; IEEE; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo, A.; Criscuolo, S.; De Benedetto, E.; Masciullo, A.; Pesola, M.; Schiavoni, R.; Invitto, S. A method for optimizing the artifact subspace reconstruction performance in low-density EEG. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 21257–21265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, B.Y.; Diddi, S.V.S.; Ko, L.W.; Wang, S.J.; Chang, C.Y.; Jung, T.P. Development of an adaptive artifact subspace reconstruction based on Hebbian/anti-Hebbian learning networks for enhancing BCI performance. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2022, 35, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, D.; Vishnu, K.; Ransing, R.; Gupta, C.N. Dynamical Embedding of Single-Channel Electroencephalogram for Artifact Subspace Reconstruction. Sensors 2024, 24, 6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; Chen, D.; Ouyang, G.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Li, X. An EEMD-ICA approach to enhancing artifact rejection for noisy multivariate neural data. IEEE transactions on neural systems and rehabilitation engineering 2015, 24, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.J. A novel EEMD-CCA approach to removing muscle artifacts for pervasive EEG. IEEE Sensors Journal 2018, 19, 8420–8431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Duan, F.; Feng, F.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Caiafa, C.F.; Marti-Puig, P.; Solé-Casals, J. A fast approach to removing muscle artifacts for EEG with signal serialization based ensemble empirical mode decomposition. Entropy 2021, 23, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egambaram, A.; Badruddin, N.; Asirvadam, V.S.; Begum, T.; Fauvet, E.; Stolz, C. FastEMD–CCA algorithm for unsupervised and fast removal of eyeblink artifacts from electroencephalogram. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2020, 57, 101692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.B.; Shah, A.; Maheshwari, S.; Anand, V.; Chakraborty, S.; Kumar, T.S. An empirical wavelet transform-based approach for motion artifact removal in electroencephalogram signals. Decision Analytics Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadikar, S.; Sinha, N.; Ghosh, R.; Ghaderpour, E. Automatic muscle artifacts identification and removal from single-channel eeg using wavelet transform with meta-heuristically optimized non-local means filter. Sensors 2022, 22, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dora, M.; Holcman, D. Adaptive single-channel EEG artifact removal with applications to clinical monitoring. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2022, 30, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Su, Y.; Wu, X.; Wu, X. A novel end-to-end 1D-ResCNN model to remove artifact from EEG signals. Neurocomputing 2020, 404, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, C.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Q.; Wu, H. A novel convolutional neural network model to remove muscle artifacts from EEG. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2021; IEEE; pp. 1265–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, X.; Rong, X.; Iwata, M. A novel multimodule neural network for eeg denoising. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 49528–49541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, C.; Yu, F.; Zhang, L.; Luo, W. DTP-Net: learning to reconstruct EEG signals in time-frequency domain by multi-scale feature reuse. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2024, 28, 2662–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawangjai, P.; Trakulruangroj, M.; Boonnag, C.; Piriyajitakonkij, M.; Tripathy, R.K.; Sudhawiyangkul, T.; Wilaiprasitporn, T. EEGANet: Removal of ocular artifacts from the EEG signal using generative adversarial networks. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2021, 26, 4913–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.H.; Chang, K.Y.; Huang, C.S.; Jung, T.P. IC-U-Net: a U-Net-based denoising autoencoder using mixtures of independent components for automatic EEG artifact removal. NeuroImage 2022, 263, 119586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, S.; Kumar, A. Orthogonal features based EEG signals denoising using fractional and compressed one-dimensional CNN AutoEncoder. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2022, 30, 2474–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Tang, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, N.; Tian, L.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, S.; Li, G.; et al. An approach for EEG denoising based on wasserstein generative adversarial network. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2023, 31, 3524–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Luo, Y.; Shen, H. An improved Generative Adversarial Network for Denoising EEG signals of brain-computer interface systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 China Automation Congress (CAC). IEEE, 2022; pp. 6498–6502. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Liu, A.; Li, C.; Qian, R.; Chen, X. A GAN guided parallel CNN and transformer network for EEG denoising. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, T.; Kong, W.; Lei, X.; Qiu, T. Ballistocardiogram artifact removal in simultaneous EEG-fMRI using generative adversarial network. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2022, 371, 109498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahaseni, B.; Khan, N.M. EEG Signal Denoising Using Beta-Variational Autoencoder. In Proceedings of the 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Li, L.; Li, Q. Adversarial Defense Based on Denoising Convolutional Autoencoder in EEG-Based Brain–Computer Interfaces. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Lv, M.; Wang, D.; Zhang, W. EEG Signal Denoising Using pix2pix GAN: Enhancing Neurological Data Analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.13288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.J. Removing neural signal artifacts with autoencoder-targeted adversarial transformers (AT-AT). arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.05332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, B. EEG analysis based on time domain properties. Electroencephalography and clinical neurophysiology 1970, 29, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.U.; Malik, A.S.; Ahmad, R.F.; Badruddin, N.; Kamel, N.; Hussain, M.; Chooi, W.T. Feature extraction and classification for EEG signals using wavelet transform and machine learning techniques. Australasian physical & engineering sciences in medicine 2015, 38, 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Subasi, A.; Ercelebi, E. Classification of EEG signals using neural network and logistic regression. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2005, 78, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.R.; Sree, S.V.; Ang, P.C.A.; Yanti, R.; Suri, J.S. Application of non-linear and wavelet based features for the automated identification of epileptic EEG signals. International journal of neural systems 2012, 22, 1250002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirrmeister, R.T.; Springenberg, J.T.; Fiederer, L.D.J.; Glasstetter, M.; Eggensperger, K.; Tangermann, M.; Hutter, F.; Burgard, W.; Ball, T. Deep learning with convolutional neural networks for EEG decoding and visualization. Human brain mapping 2017, 38, 5391–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. ieee transactions on knowledge and data engineering 2010, 22(10), 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zancanaro, A.; Cisotto, G.; Zoppis, I.; Manzoni, S.L. vEEGNet: learning latent representations to reconstruct EEG raw data via variational autoencoders. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health, 2023; Springer; pp. 114–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lawhern, V.J.; Solon, A.J.; Waytowich, N.R.; Gordon, S.M.; Hung, C.P.; Lance, B.J. EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Journal of neural engineering 2018, 15, 056013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Tang, F.; Si, B.; Feng, X. Learning joint space–time–frequency features for EEG decoding on small labeled data. Neural Networks 2019, 114, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xia, P.; Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Du, L.; Fang, Z.; Du, M. EEG-based emotion recognition using a 2D CNN with different kernels. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, T.; Jaafar, R.; Remli, R.; Wan Zaidi, W.A. A classification model of EEG signals based on RNN-LSTM for diagnosing focal and generalized epilepsy. Sensors 2022, 22, 7269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falaschetti, L.; Biagetti, G.; Alessandrini, M.; Turchetti, C.; Luzzi, S.; Crippa, P. Multi-class detection of neurodegenerative diseases from EEG signals using lightweight lstm neural networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Xu, F.; Liu, X.; Hou, F. Deep learning in automatic sleep staging with a single channel electroencephalography. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12, 628502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Dai, W.; Zhang, H.; Jin, X.; Cao, J.; Kong, W. Brain-machine coupled learning method for facial emotion recognition. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2023, 45, 10703–10717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, H.; Dong, X.; Zhong, X.; Cui, H.; Ji, D.; He, L.; Liu, G.; Zhou, W. CNN-Informer: A hybrid deep learning model for seizure detection on long-term EEG. Neural Networks 2025, 181, 106855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Westover, M.; Sun, J. Biot: Biosignal transformer for cross-data learning in the wild. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 78240–78260. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Tang, P.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X. Denoise enhanced neural network with efficient data generation for automatic sleep stage classification of class imbalance. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 2023; IEEE; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Hu, S.; Ma, X.; Tao, X. Multi-Class Image Generation from EEG Features with Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Wireless Communications and Signal Processing (WCSP), 2023; IEEE; pp. 534–539. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Guo, Y. Dual AxAtGAN: A Feature Intregrate BCI Model for Image Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 2023 13th International Conference on Information Technology in Medicine and Education (ITME), 2023; IEEE; pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.; Cui, W.; Yu, S.; Han, H.; Hu, B.; Li, Y. A dual-branch dynamic graph convolution based adaptive transformer feature fusion network for EEG emotion recognition. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2022, 13, 2218–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, W.; Yu, T.; Li, X.; Liao, X.; Li, Y. Dynamic multi-graph convolution-based channel-weighted transformer feature fusion network for epileptic seizure prediction. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2023, 31, 4266–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- kumar Ravikanti, D.; Saravanan, S. EEGAlzheimer’sNet: Development of transformer-based attention long short term memory network for detecting Alzheimer disease using EEG signal. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 86, 105318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tao, X. TBEEG: A two-branch manifold domain enhanced transformer algorithm for learning EEG decoding. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2024, 32, 1466–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsenvand, M.N.; Izadi, M.R.; Maes, P. Contrastive representation learning for electroencephalogram classification. In Proceedings of the Machine learning for health. PMLR, 2020; pp. 238–253. [Google Scholar]

- Kostas, D.; Aroca-Ouellette, S.; Rudzicz, F. BENDR: Using transformers and a contrastive self-supervised learning task to learn from massive amounts of EEG data. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2021, 15, 653659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørskov, A.; Neergaard Zahid, A.; Mørup, M. Cslp-ae: A contrastive split-latent permutation autoencoder framework for zero-shot electroencephalography signal conversion. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 13179–13199. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi Foumani, N.; Mackellar, G.; Ghane, S.; Irtza, S.; Nguyen, N.; Salehi, M. Eeg2rep: enhancing self-supervised eeg representation through informative masked inputs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2024; pp. 5544–5555. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.B.; Zhao, L.M.; Lu, B.L. Large brain model for learning generic representations with tremendous EEG data in BCI. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2405.18765. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, W.; He, Y.; Xu, C.; Ma, L.; Li, H. Eegpt: Pretrained transformer for universal and reliable representation of eeg signals. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 39249–39280. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, M.R.; Ding, Y.; Sen, S. SSL-SE-EEG: A Framework for Robust Learning from Unlabeled EEG Data with Self-Supervised Learning and Squeeze-Excitation Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.19829. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, T.j.; Fan, Y.; Chen, L.; Guo, G.; Zhou, C. EEG signal reconstruction using a generative adversarial network with wasserstein distance and temporal-spatial-frequency loss. Frontiers in neuroinformatics 2020, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uraechu, U. Self-Supervised Contrastive Learning Using EEG Signals For Mental Stress Assessment. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H.; Li, S.; Li, T.; Pan, G. SPICED: A Synaptic Homeostasis-Inspired Framework for Unsupervised Continual EEG Decoding. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.17439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Xie, C.; Zhang, J.; You, Q.; Pan, J. A Progressive Multi-Domain Adaptation Network With Reinforced Self-Constructed Graphs for Cross-Subject EEG-Based Emotion and Consciousness Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Bae, J.; Wang, B.; Ko, H.; Lim, J.S. Feature selection method using multi-agent reinforcement learning based on guide agents. Sensors 2022, 23, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Shang, S.; Tang, L.; He, L.; Zhou, M. EEG channel selection algorithm based on Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Networking, Sensing and Control (ICNSC), 2022; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wu, C.; Pan, J.; Wang, F. Few-shot EEG sleep staging based on transductive prototype optimization network. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics 2023, 17, 1297874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Chen, P.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; Li, M.; Yang, X.; Gao, Z. EEG-based motor imagery recognition framework via multisubject dynamic transfer and iterative self-training. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023, 35, 10698–10712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellot, A.; Collas, A.; Chevallier, S.; Engemann, D.; Gramfort, A. Physics-informed and unsupervised riemannian domain adaptation for machine learning on heterogeneous EEG datasets. In Proceedings of the 2024 32nd European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO). IEEE, 2024; pp. 1367–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberger, A.L.; Amaral, L.A.; Glass, L.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Ivanov, P.C.; Mark, R.G.; Mietus, J.E.; Moody, G.B.; Peng, C.K.; Stanley, H.E. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. circulation 2000, 101, e215–e220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Gao, X.; Gao, S. A benchmark dataset for SSVEP-based brain–computer interfaces. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2016, 25, 1746–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]