Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The BCI Competition IV Dataset 2a

2.2. EEG Microstates and Gaussian Microstate

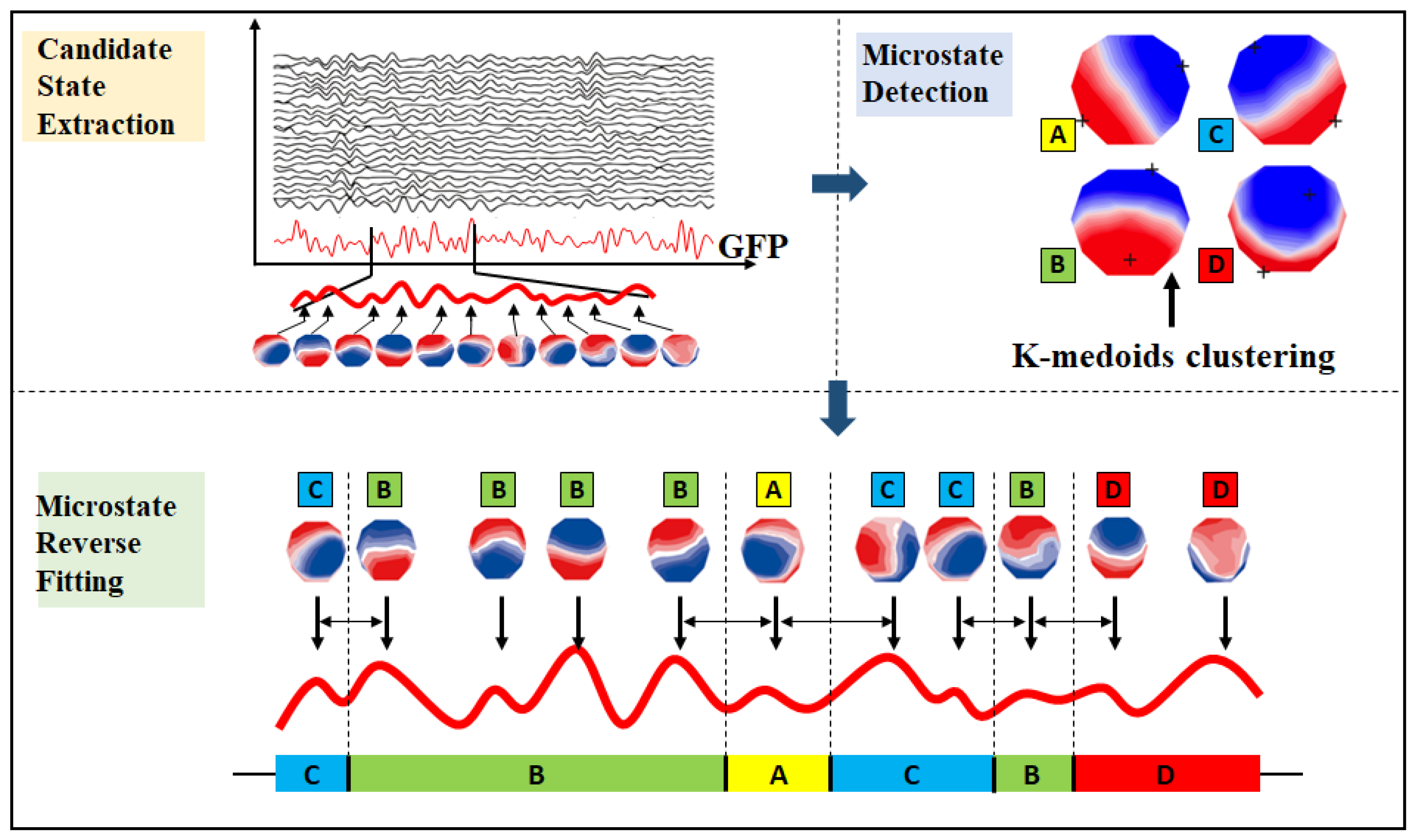

2.2.1. EEG Microstates

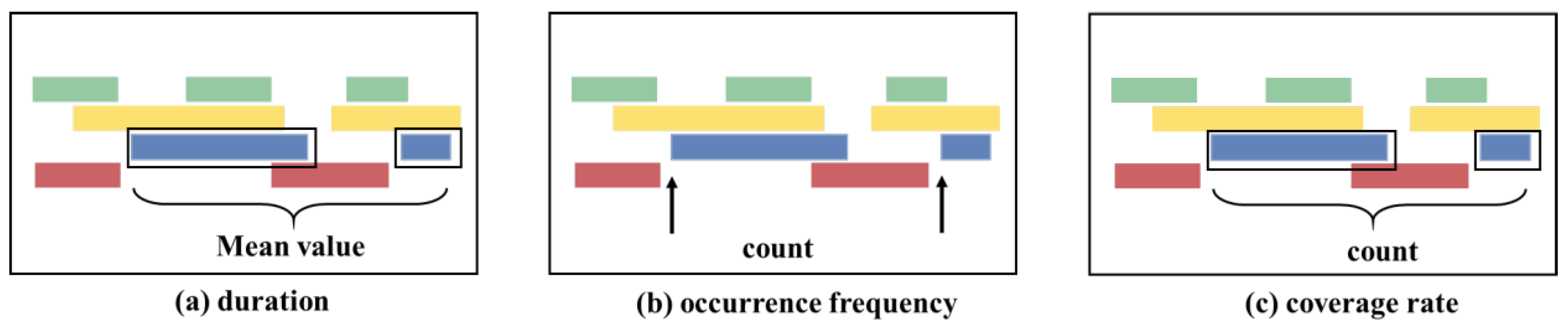

2.2.2. Gaussian Microstate

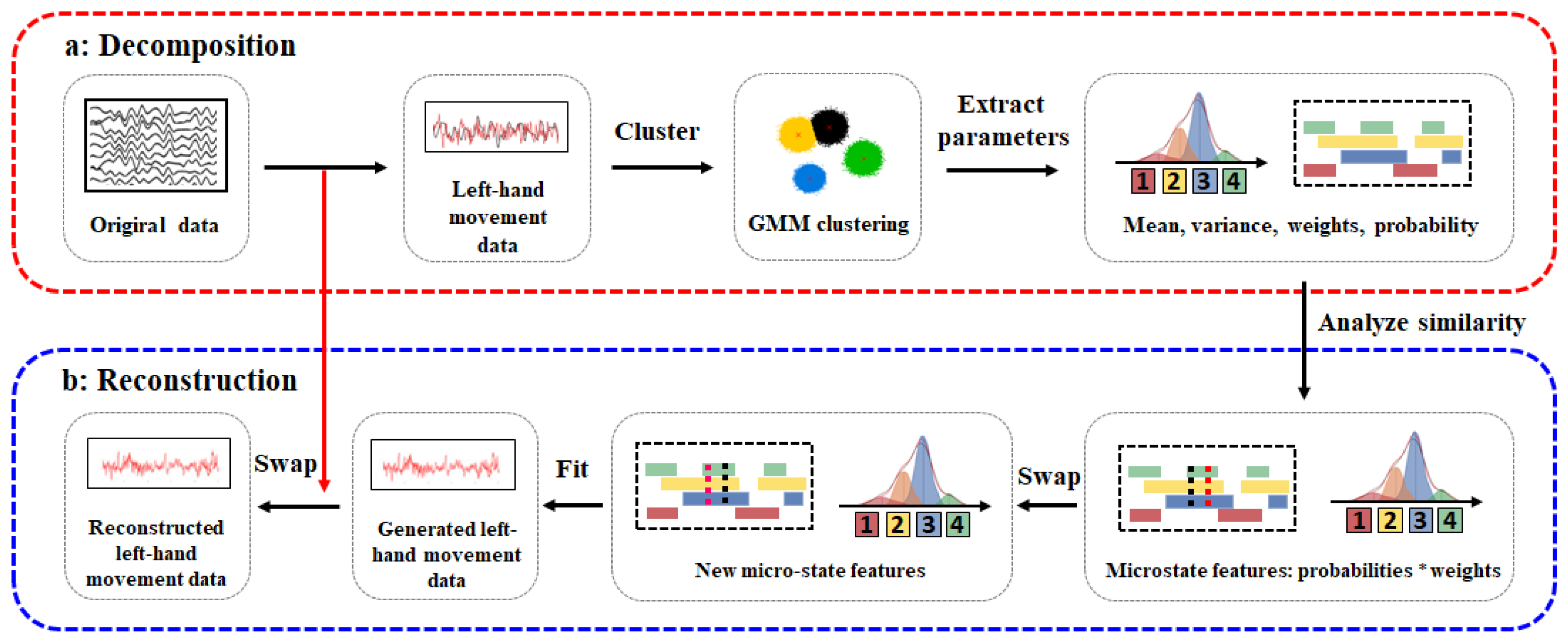

2.3. Gaussian Mixture Model-Based EEG Data Augmentation Method

2.3.1. Gaussian Microstate Decomposition

2.3.2. Gaussian Microstate Reconstruction

2.4. Other Augmentation Methods

2.4.1. Time-Domain Augmentation Methods

2.4.2. Frequency-Domain Augmentation Methods

2.4.3. Spatial-Domain Augmentation Methods

3. Experiment and Results

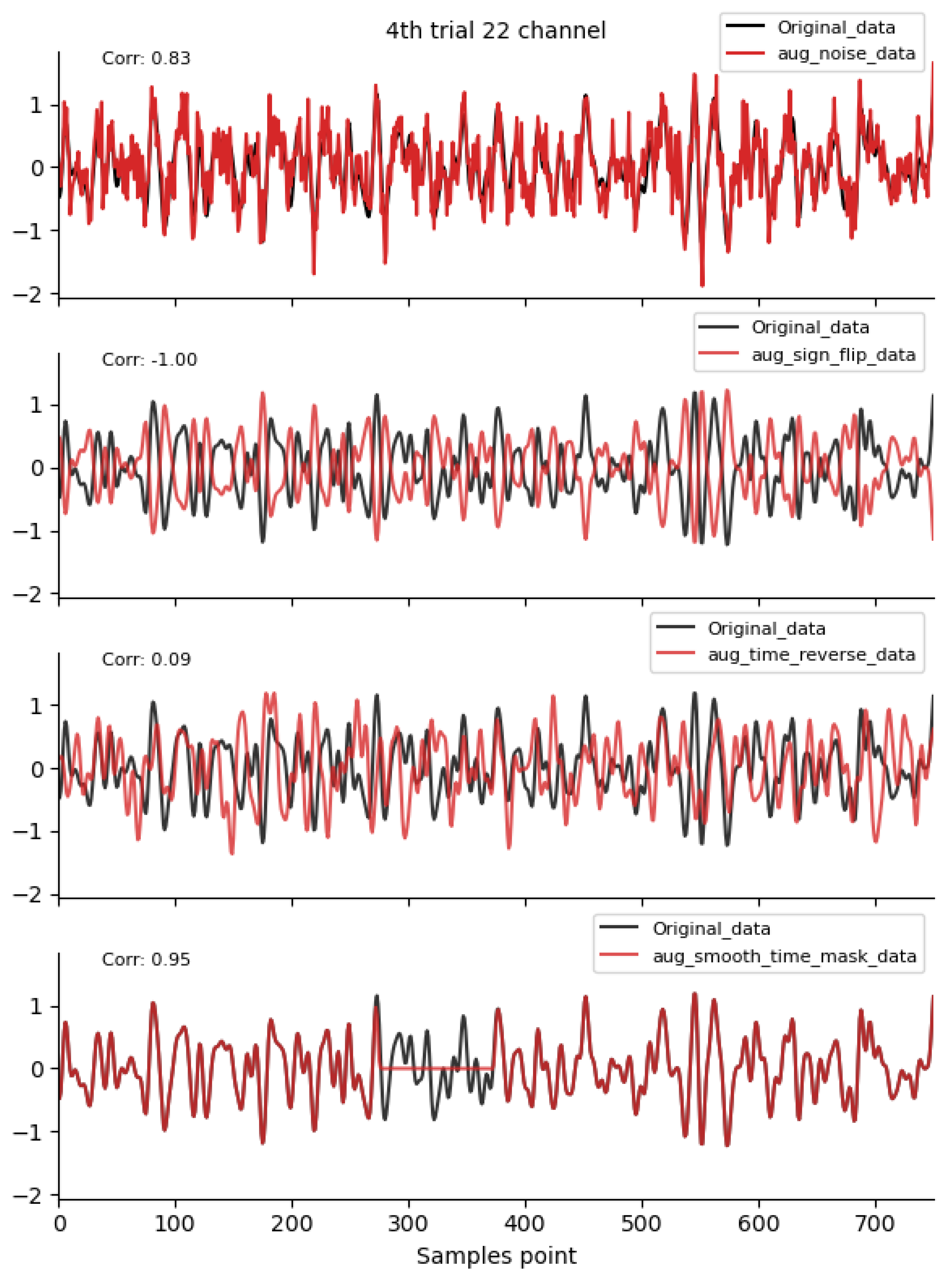

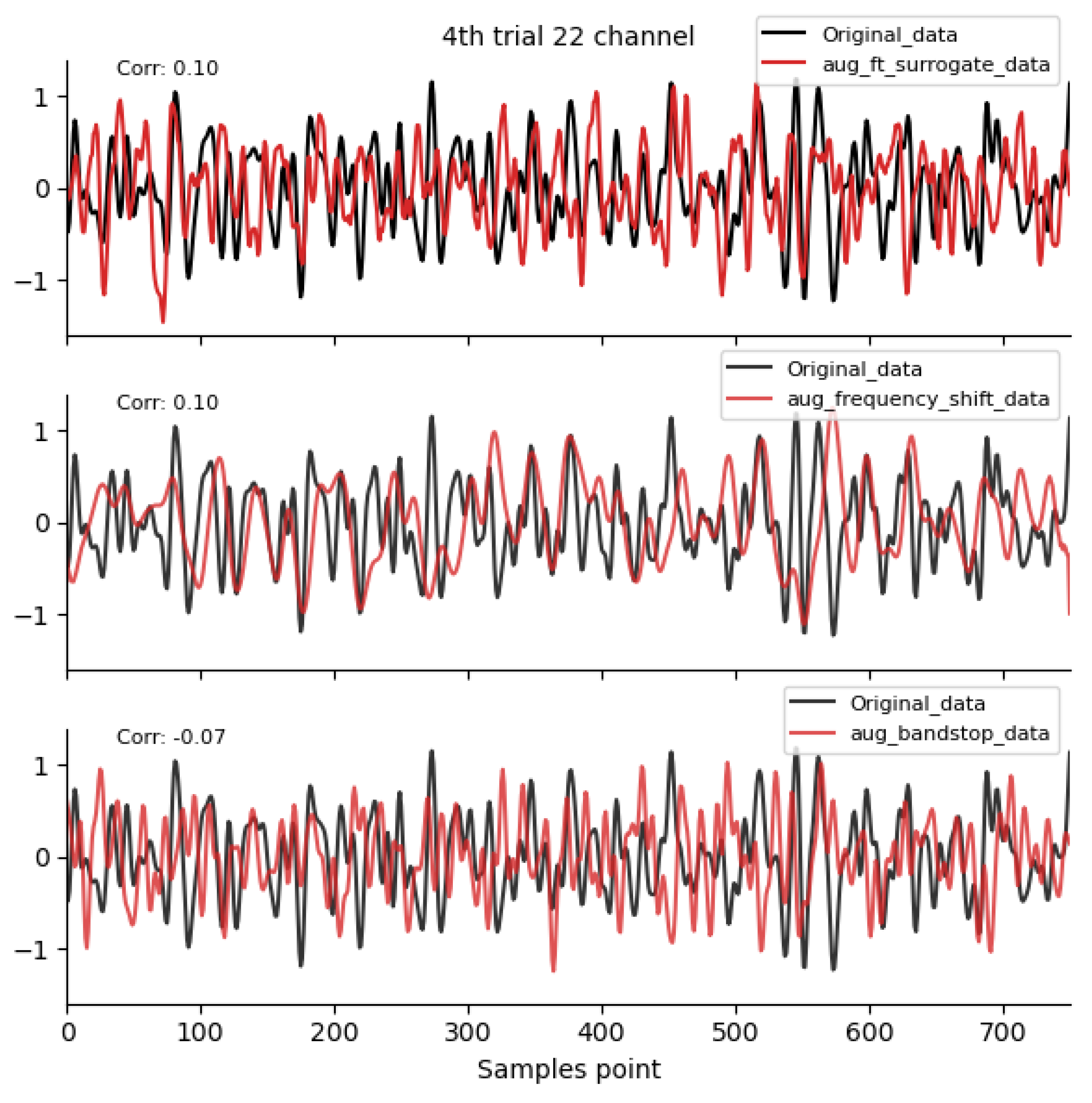

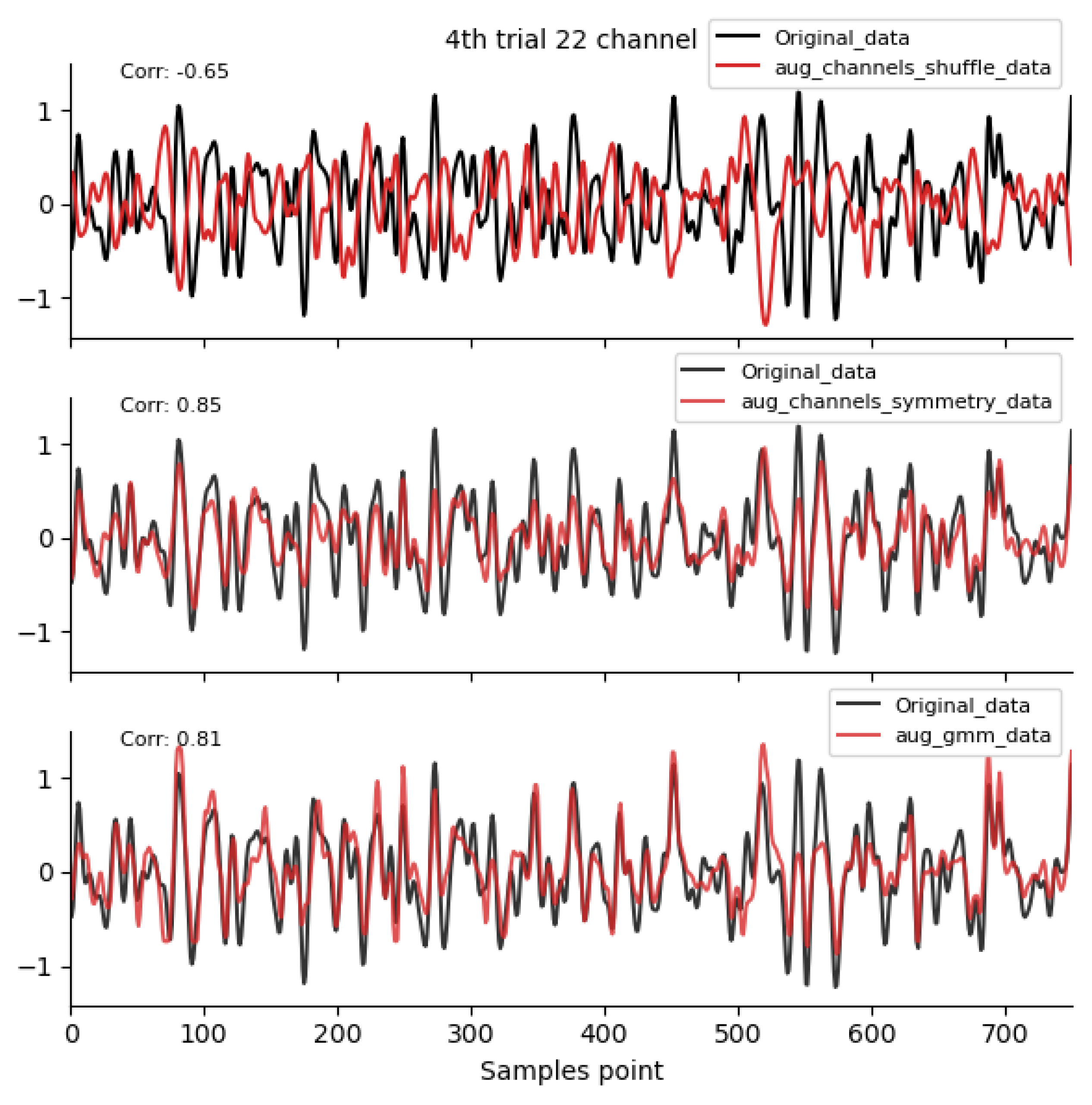

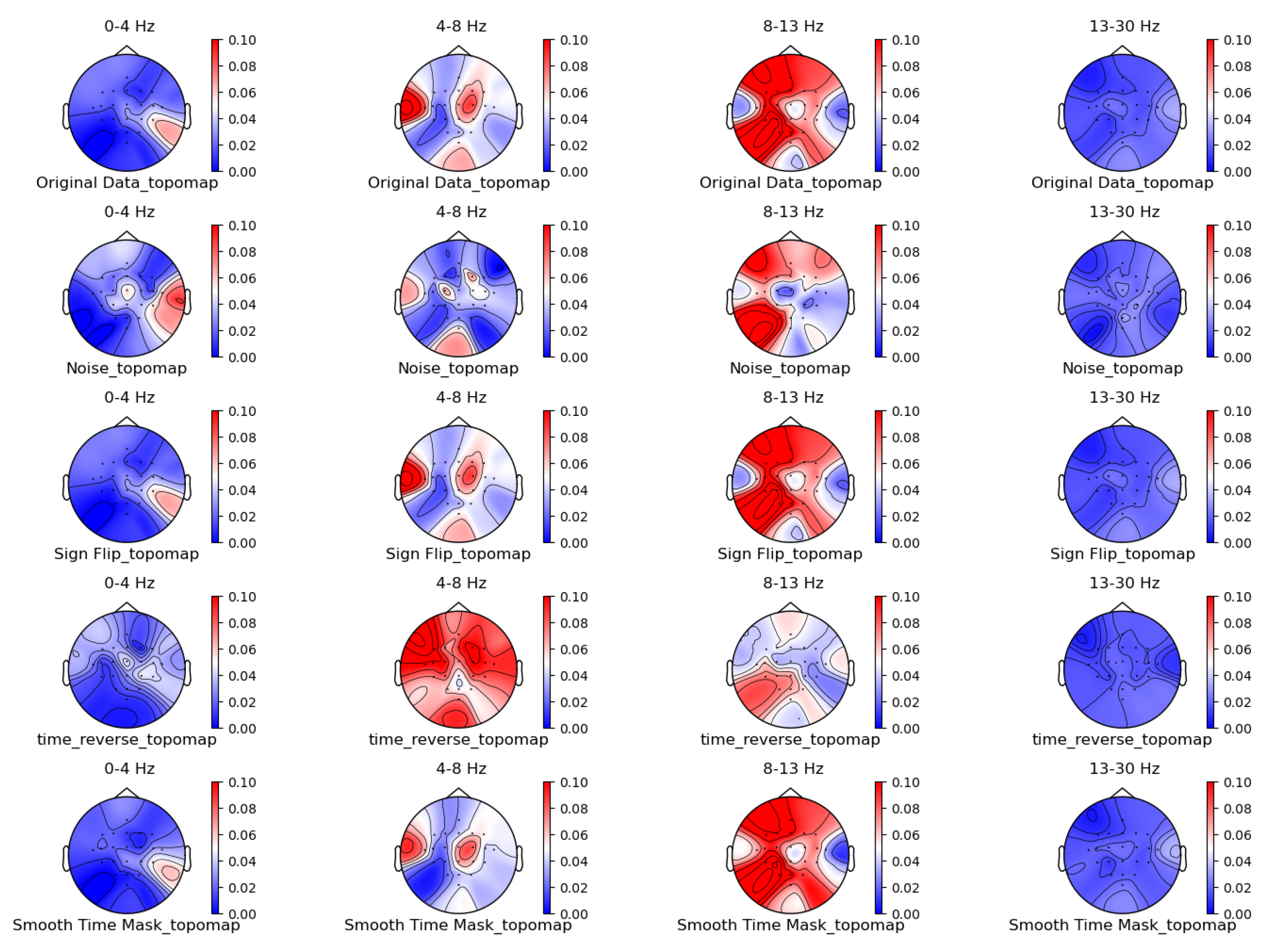

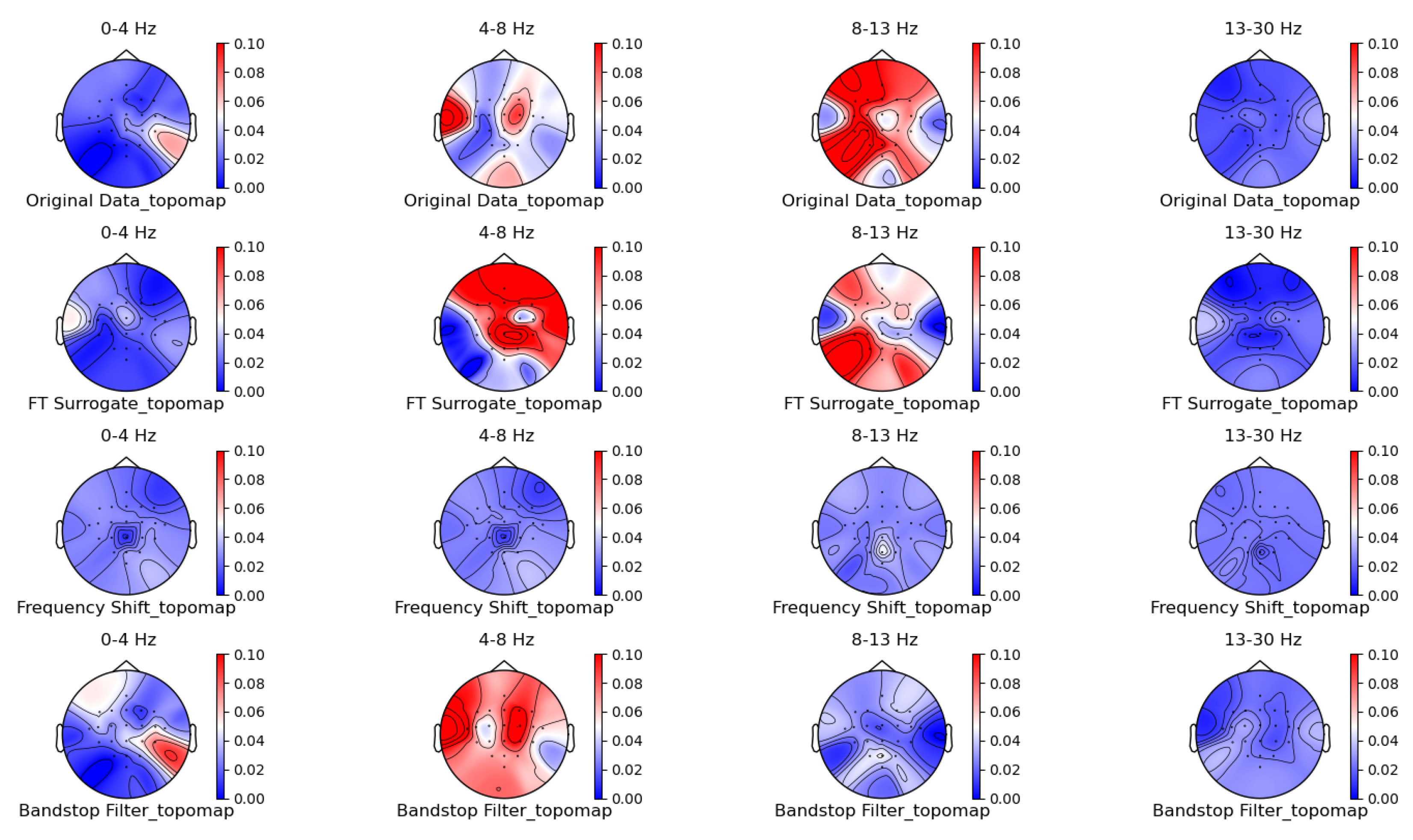

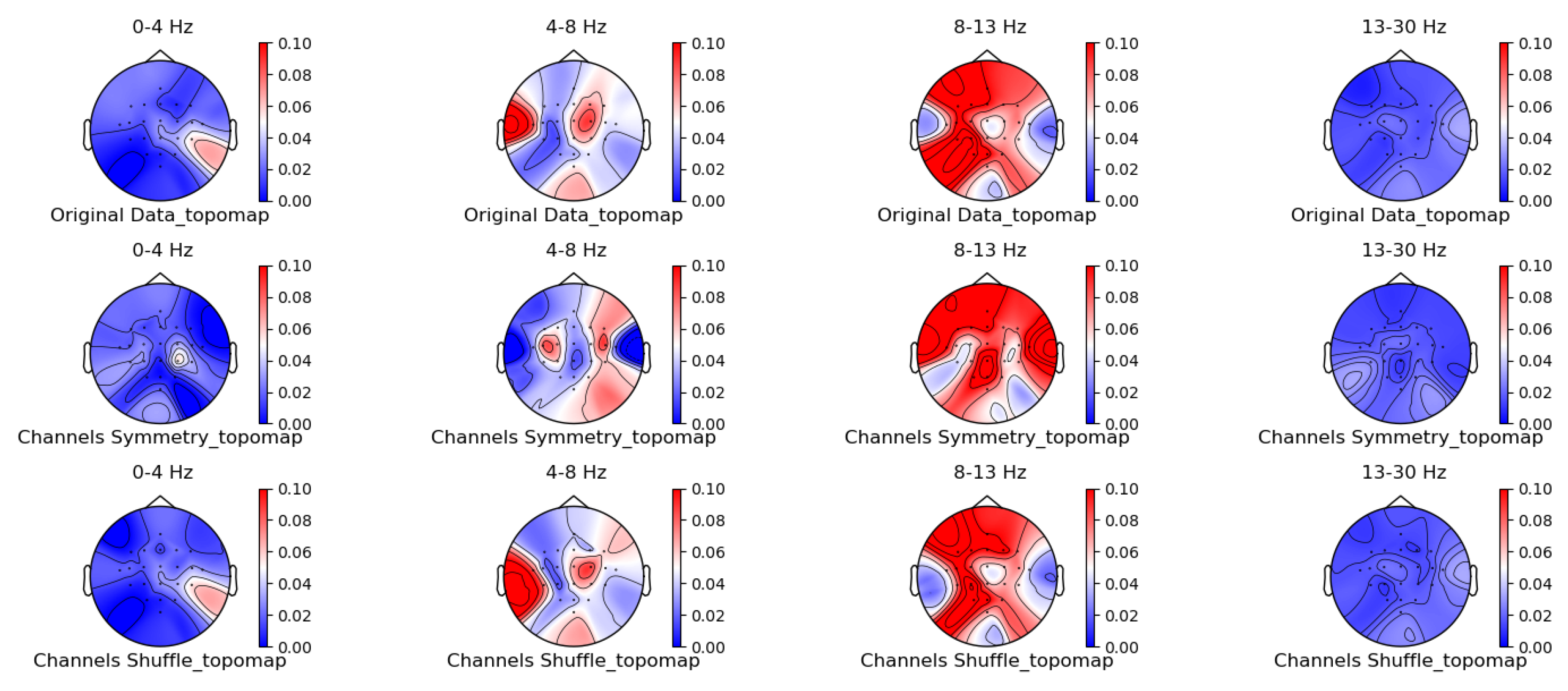

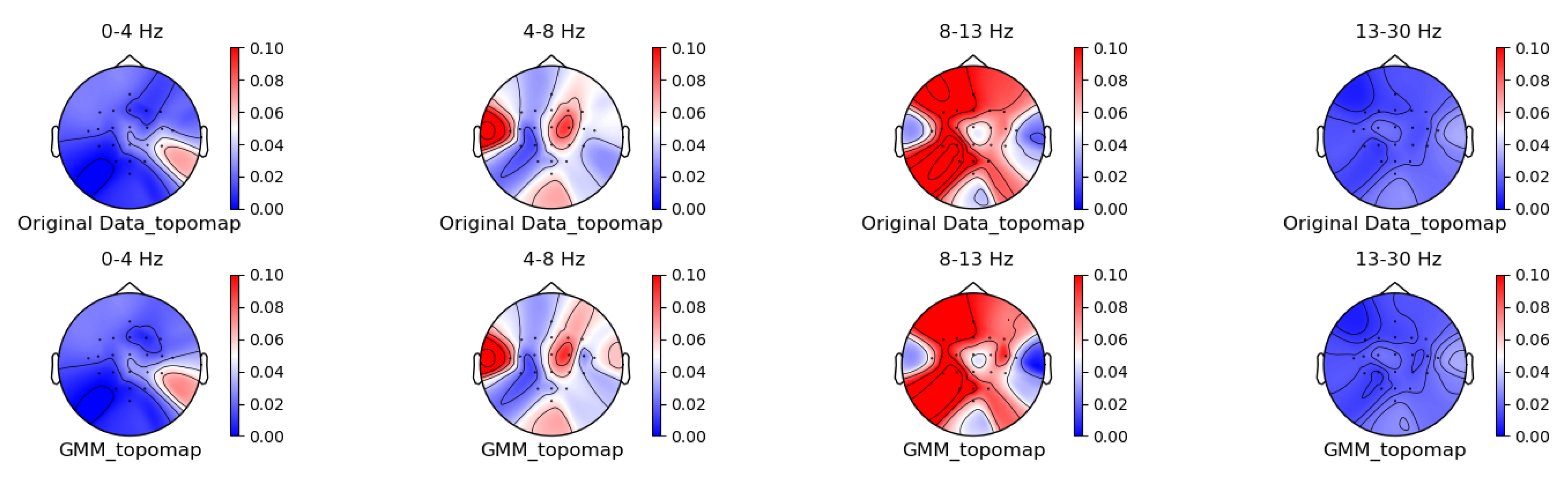

3.1. Comparison of Data Characteristics Generated by Different Augmentation Methods

3.2. Comparison of the Effectiveness of Data Generated by Different Augmentation Methods on Classification Models

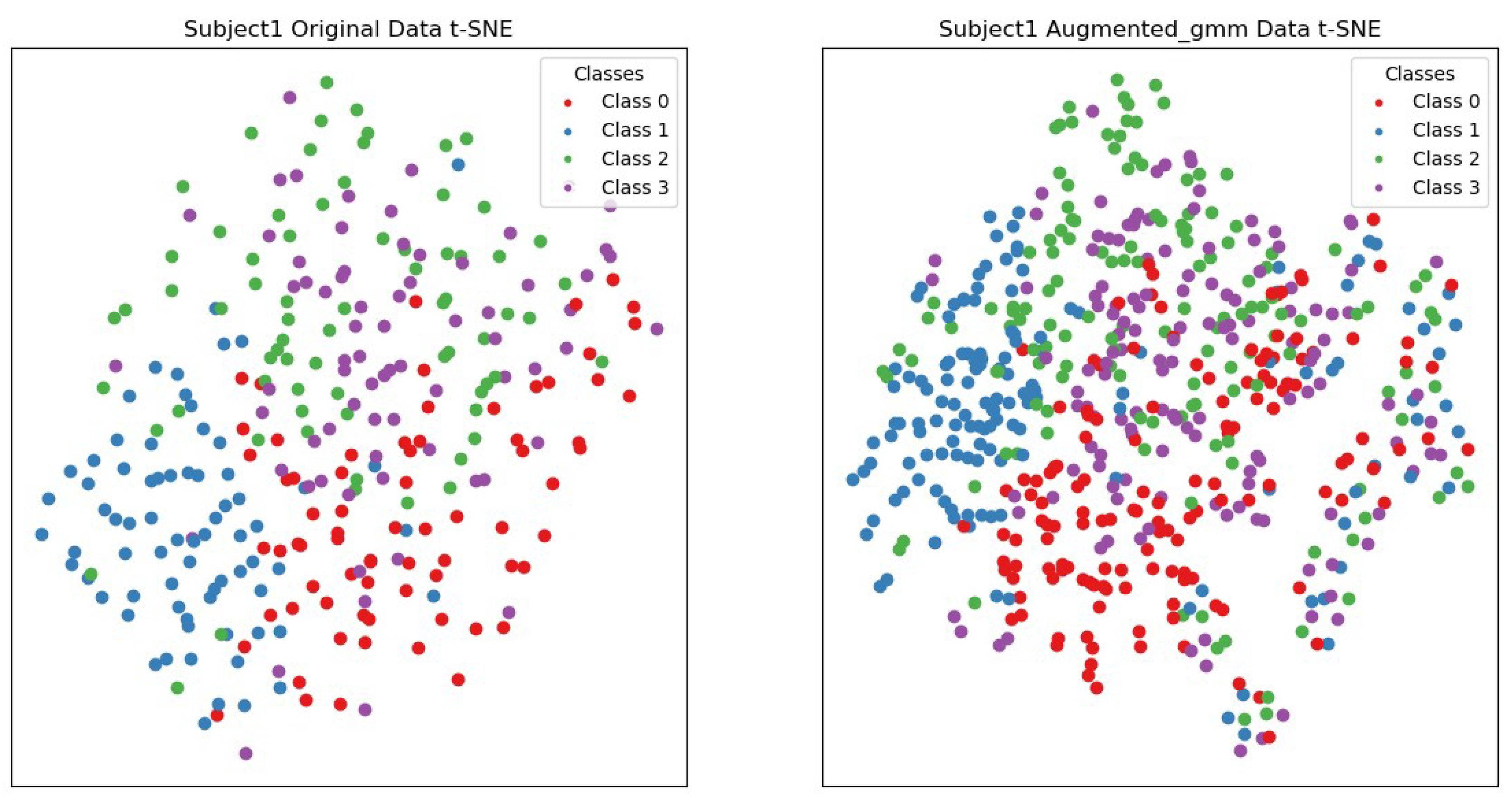

3.3. Comparison of Visualization Results Between Original Data and the Data Augmented Using the Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM)

3.3.1. Clarity of Clusters

3.3.2. Local Structure Compactness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Results

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EEG | Electroencephalograms |

| GNAs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| VAEs | Ariational Autoencoders |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise Ratio |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Models |

References

- Abdul Hussain, A.; Singh, A.; Guesgen, H.; Lal, S. A Comprehensive Review on Critical Issues and Possible Solutions of Motor Imagery Based Electroencephalography Brain-Computer Interface. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Y.; Banville, H.; Albuquerque, I.; Gramfort, A.; Falk, T.H.; Faubert, J. Deep learning-based electroencephalography analysis: a systematic review. Journal of Neural Engineering 2019, 16, 051001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigdely-Shamlo, N.; Mullen, T.; Kothe, C.; Su, K.M.; Robbins, K.A. The PREP pipeline: standardized preprocessing for large-scale EEG analysis. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jas, M.; Engemann, D.A.; Bekhti, Y.; Raimondo, F.; Gramfort, A. Autoreject: Automated artifact rejection for MEG and EEG data. NeuroImage 2017, 159, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramfort, A.; e, D.S.; Haueisen, J.; Hämäläinen, M.; Kowalskig, M. Time-frequency mixed-norm estimates: Sparse M/EEG imaging with non-stationary source activations. NeuroImage 2013, 70, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuanar, S.; Athitsos, V.; Pradhan, N.; Mishra, A.; Rao, K. Cognitive Analysis of Working Memory Load from Eeg, by a Deep Recurrent Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2018; pp. 2576–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramfort, A.; Strohmeier, D.; J. Haueisen e, f.; d, M.H.; g, M.K. Brain–machine interfaces from motor to mood. Nature Neuroscience 2019, 22, 1554–1564. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sani1, O.; Yang1, Y.; Lee1, M.; Dawes2, H.; Chang2, E.; Shanechi1, M. Neural Decoding and Control of Mood to Treat Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Biological Psychiatry 2020, 87, s95–s96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, A.; Minoda, Y.; Morikawa, K. Data augmentation methods for machine-learning-based classification of bio-signals. In Proceedings of the 2017 10th Biomedical Engineering International Conference (BMEiCON); 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krell, M.M.; Kim, S.K. Rotational data augmentation for electroencephalographic data. In Proceedings of the 2017 39th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2017; pp. 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, E.; Liang, D.; Maoz, U. Data augmentation for deep-learning-based electroencephalography. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2020, 346, 108885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Um, T.T.; Pfister, F.M.J.; Pichler, D.; Endo, S.; Lang, M.; Hirche, S.; Fietzek, U.; Kulić, D. Data augmentation of wearable sensor data for parkinson’s disease monitoring using convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2017; ICMI ’17, p. 216–220. [CrossRef]

- Lotte.; Fabien. Signal Processing Approaches to Minimize or Suppress Calibration Time in Oscillatory Activity-Based Brain–Computer Interfaces. Proceedings of the IEEE 2015, 103, 871–890. [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Luo, Z.; Yan, Y.; Yan, H.; Jiang, J.; Li, W.; Xie, L.; Yin, E. Data Augmentation: Using Channel-Level Recombination to Improve Classification Performance for Motor Imagery EEG. Proceedings of the IEEE 2021, 15, 645–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Lee, D.H.; Choi, Y.W. CropCat: Data Augmentation for Smoothing the Feature Distribution of EEG Signals. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Winter Conference on Brain-Computer Interface (BCI); 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y, L.; LZ, Z.; ZY, W.; BL, L. Data augmentation for enhancing EEG-based emotion recognition with deep generative models. Journal of neural engineering 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabedal, J.T.C.; Snyder, J.C.; Cakmak, A.; Nemati, S.; Clifford, G.D. Addressing Class Imbalance in Classification Problems of Noisy Signals by using Fourier Transform Surrogates. ArXiv, 2018; 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommel, C.; Moreau, T.; Gramfort, A. CADDA: Class-wise Automatic Differentiable Data Augmentation for EEG Signals. ArXiv, 2021; abs/2106.13695. [Google Scholar]

- Deiss, O.; Biswal, S.; Jing, J.; Sun, H.; Westover, M.B.; Sun, J. HAMLET: Interpretable Human And Machine co-LEarning Technique. ArXiv 2018, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Grangier, D.; Pietquin, O.; Zeghidour, N. Learning From Heterogeneous Eeg Signals with Differentiable Channel Reordering. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021 - 2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2021; pp. 1255–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Int. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhong, S.h.; Peng, J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, Y. Data Augmentation for EEG-Based Emotion Recognition with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the MultiMedia Modeling, Cham; 2018; pp. 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenvand, M.N.; Izadi, M.R.; Maes, P. Contrastive Representation Learning for Electroencephalogram Classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Machine Learning for Health NeurIPSWorkshop; Alsentzer, E.; McDermott, M.B.A.; Falck, F.; Sarkar, S.K.; Roy, S.; Hyland, S.L., Eds. PMLR, 11 Dec 2020, Vol. 136, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 238–253.

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A Survey on Transfer Learning. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2010, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhong, N. Human Emotion Recognition with Electroencephalographic Multidimensional Features by Hybrid Deep Neural Networks. Applied Sciences 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Wang, Y.; Jia, C. A new data augmentation method for EEG features based on the hybrid model of broad-deep networks. Expert Systems with Applications 2022, 202, 117386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjovsky, M.; Chintala, S.; Bottou, L. Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning - Volume 70. JMLR.org, 2017, ICML’17, p. 214–223. [CrossRef]

- Gulrajani, I.; Ahmed, F.; Arjovsky, M.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A. Improved training of wasserstein GANs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; NIPS’17, p. 5769–5779. [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Li, Q.; Xie, H.; Lau, R.Y.; Wang, Z.; Smolley, S.P. Least Squares Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017; pp. 2813–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, K.G.; Schirrmeister, R.T.; Ball, T. EEG-GAN: Generative adversarial networks for electroencephalograhic (EEG) brain signals. ArXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lu, B.L. EEG Data Augmentation for Emotion Recognition Using a Conditional Wasserstein GAN. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2018; pp. 2535–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimi, F.; Dosen, S.; Ang, K.K.; Mrachacz-Kersting, N.; Guan, C. Generative Adversarial Networks-Based Data Augmentation for Brain–Computer Interface. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 32, 4039–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramponi, G.; Protopapas, P.; Brambilla, M.; Janssen, R. T-CGAN: Conditional Generative Adversarial Network for Data Augmentationin Noisy Time Series with Irregular Sampling. CoRR, 2018; abs/1811.08295. [Google Scholar]

- JOUR. ; Fei, Z.; Fei, Y.; Yuchen, F.; Quan, L.; Bairong, S. Electrocardiogram generation with a bidirectional LSTM-CNN generative adversarial network. Scientific Reports 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Yan, B.; Tong, L.; Shu, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, K.; Zeng, Y. Data Augmentation for EEG-Based Emotion Recognition Using Generative Adversarial Networks. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, L.; Zhang, J. MEG cortical microstates: Spatiotemporal characteristics, dynamic functional connectivity and stimulus-evoked responses. NeuroImage 2022, 251, 119006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Liu, X.; Dai, R.; Tang, X. Exploring differences between left and right hand motor imagery via spatio-temporal EEG microstate. Computer Assisted Surgery 2017, 22, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, G.; Blankertz, B. BCI Competition 2003–Data set IIa: spatial patterns of self-controlled brain rhythm modulations. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2004, 51, 1062–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, J. Motor Imagery Recognition Based on GMM-JCSFE Model. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2024, 32, 3348–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, K.K.; Chin, Z.Y.; Wang, C.; Guan, C.; Zhang, H. Filter Bank Common Spatial Pattern Algorithm on BCI Competition IV Datasets 2a and 2b. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawhern, V.J.; Solon, A.J.; Waytowich, N.R.; Gordon, S.M.; Hung, C.P.; Lance, B.J. EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain–computer interfaces. Journal of Neural Engineering 2018, 15, 056013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingfei, H.; Deyang, W.; Haiyan, L.; Fei, J.; Hongtao, L. ShallowNet: An Efficient Lightweight Text Detection Network Based on Instance Count-Aware Supervision Information. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing, Cham; 2021; pp. 633–644. [Google Scholar]

- Schirrmeister, R.; Gemein, L.; Eggensperger, K.; Hutter, F.; Ball, T. Deep learning with convolutional neural networks for decoding and visualization of EEG pathology. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Signal Processing in Medicine and Biology Symposium (SPMB); 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm:EEG Data Augmentation Method Based on Gaussian Mixture Model |

|---|

| Input:original_data = (trial,channel,n_samples), original_labels =(trial,) |

| Output:gmm_data |

| Step1:Set model parameters.n_components = 10;random_stata = 42; = 0.8 |

| Step2:Cluster the data with the same label and calculate the microstate features |

| of each sample belonging to each cluster. |

| probs = gmm.predict_proba(original_data) |

| means = gmm.means_ |

| covariances = gmm. covariances_ |

| weights =gmm.weights_robs |

| Step3:Sampling. |

| for do |

| for do |

| for do |

| end |

| end |

| end |

| Step4:Calculate the product matrix. |

| weighted_probs_values = gmm.weights_ * probs |

| Step5:Swap similar points. |

| weighted_probs_values = swap_columns(weighted_probs_values, ) |

| Step6:Fit the data. |

| data_generate_sampel = np.matmul(weighted_probs_values ,fitted_values) |

| Step7:Swap channels and reconstruct the data. |

| gmm_data = GMM_FEATURE(probability=probability,random_state=42) |

| Method | FBCSP [40] | LSTM [41] | EEGNet [42] | ShallNet [43] | Deep4Net [44] | Avg | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original data | 67.75 | 48.17 | 46.07 | 48.91 | 52.89 | 52.76 | 8.74 |

| Noise Addition | 73.22 | 80.72 | 75.29 | 80.32 | 83.08 | 78.53 | 4.10 |

| Sign Flip | 74.63 | 80.72 | 74.50 | 81.84 | 82.75 | 78.89 | 4.01 |

| Time reverse | 78.27 | 79.32 | 76.39 | 79.73 | 79.90 | 78.72 | 1.45 |

| Time Masking | 75.46 | 79.88 | 75.52 | 80.17 | 80.92 | 78.39 | 2.67 |

| FT Surrogate | 81.26 | 77.60 | 73.34 | 80.13 | 82.19 | 78.90 | 3.55 |

| Frequency Shift | 81.18 | 74.40 | 68.47 | 72.79 | 76.83 | 74.73 | 4.72 |

| Bandstop fliter | 76.32 | 78.39 | 76.98 | 78.16 | 81.13 | 78.20 | 1.85 |

| Channel Sym | 77.87 | 75.86 | 73.93 | 79.47 | 81.61 | 77.75 | 3.00 |

| Channel Shuffle | 78.59 | 76.51 | 68.29 | 75.06 | 79.86 | 75.66 | 4.52 |

| GMM Aug | 79.67 | 80.53 | 77.70 | 82.61 | 82.73 | 80.64 | 2.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).