Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

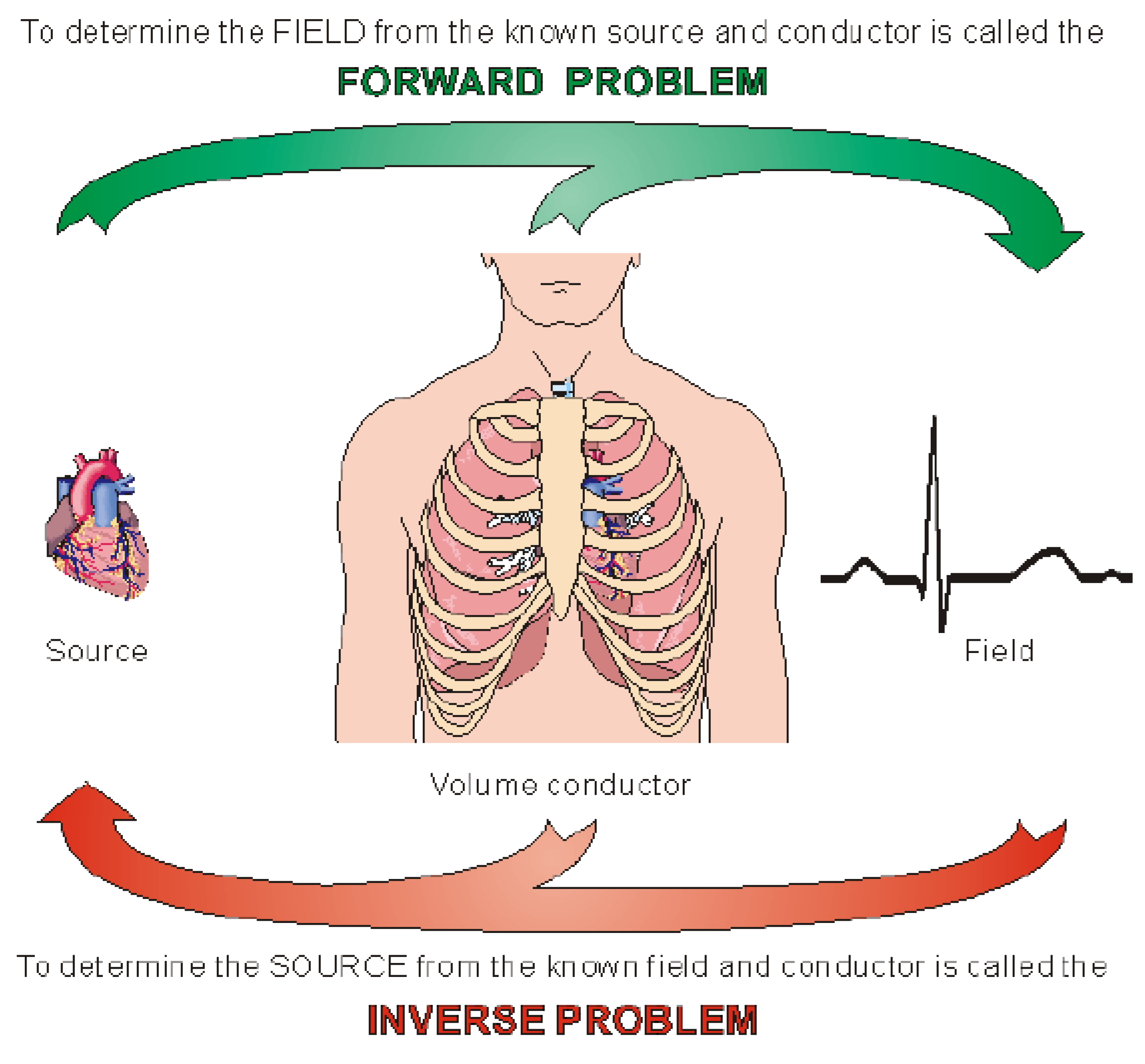

1. Introduction

- 1-

- An empirical approach based on the recognition of typical signal patterns that are known to be associated with certain source configurations.

- 2-

- Imposition of physiological constraints based on the information available about the anatomy and physiology of the active tissue. This imposes strong limitations on the number of available solutions.

- 3-

- Modeling the source and the volume conductor using simplified models. The source is characterized by only a few degrees of freedom (for instance a single dipole which can be completely determined by three independent measurements).

- 4-

- Examining the lead field pattern, from which the sensitivity distribution of the lead and therefore the statistically most probable source configuration can be estimated.

2. Methods

2.1. Regularization

2.2. The Minimum Norm (MN) Solution

2.3. The Weighted Minimum Norm (WMN) Solution

2.4. The Low Resolution Brain Electromagnetic Tomography (LORETA) solution

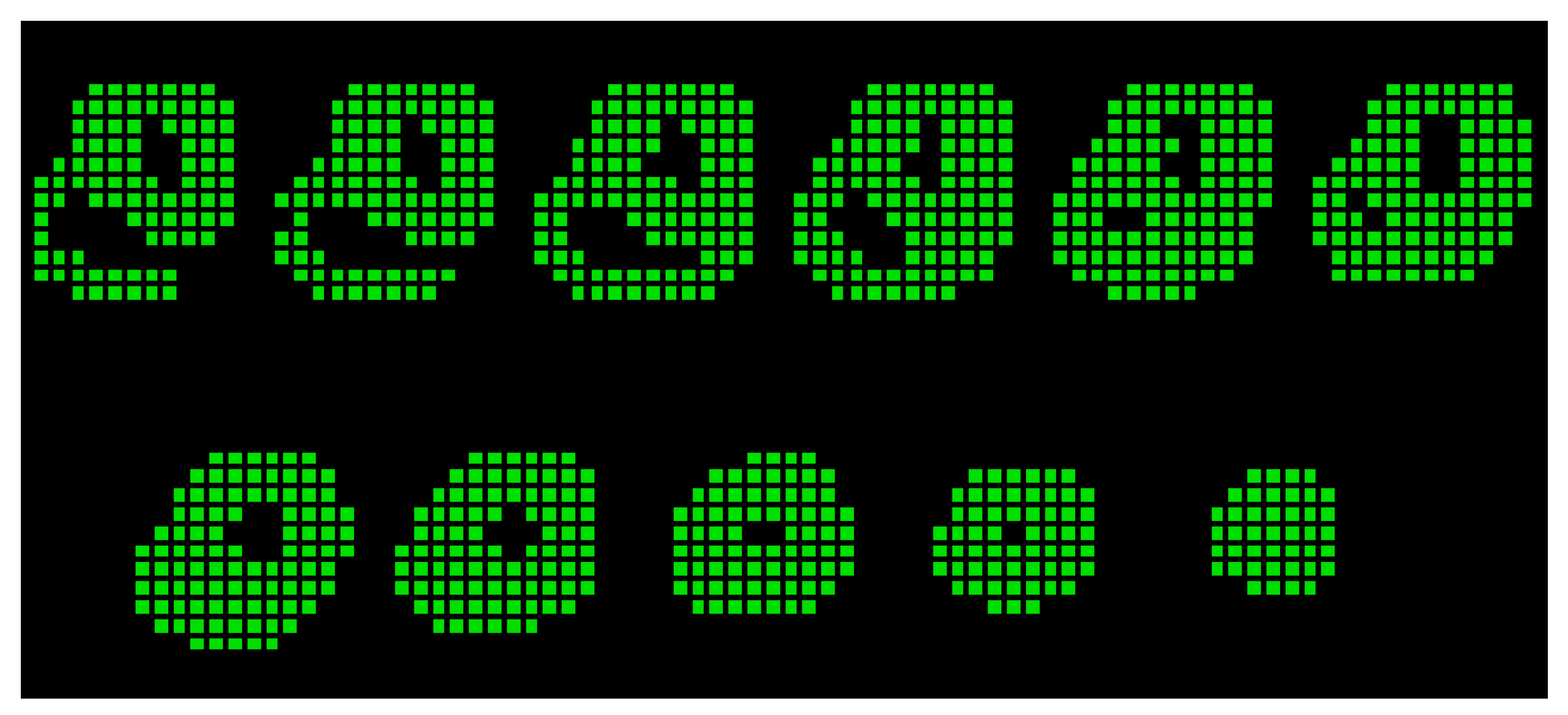

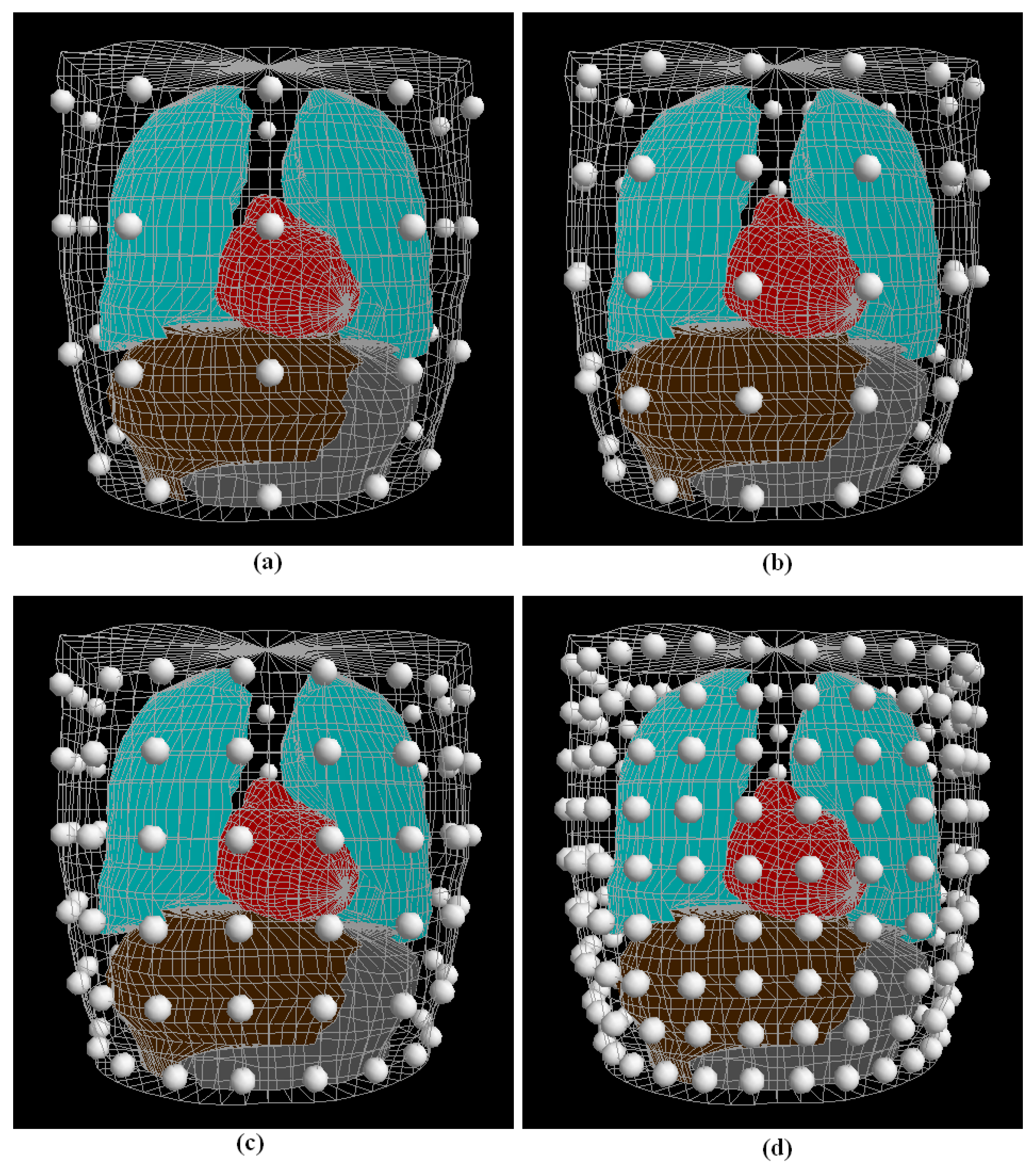

2.5. Data Generation

2.6. Localization Problem of Boundary Points

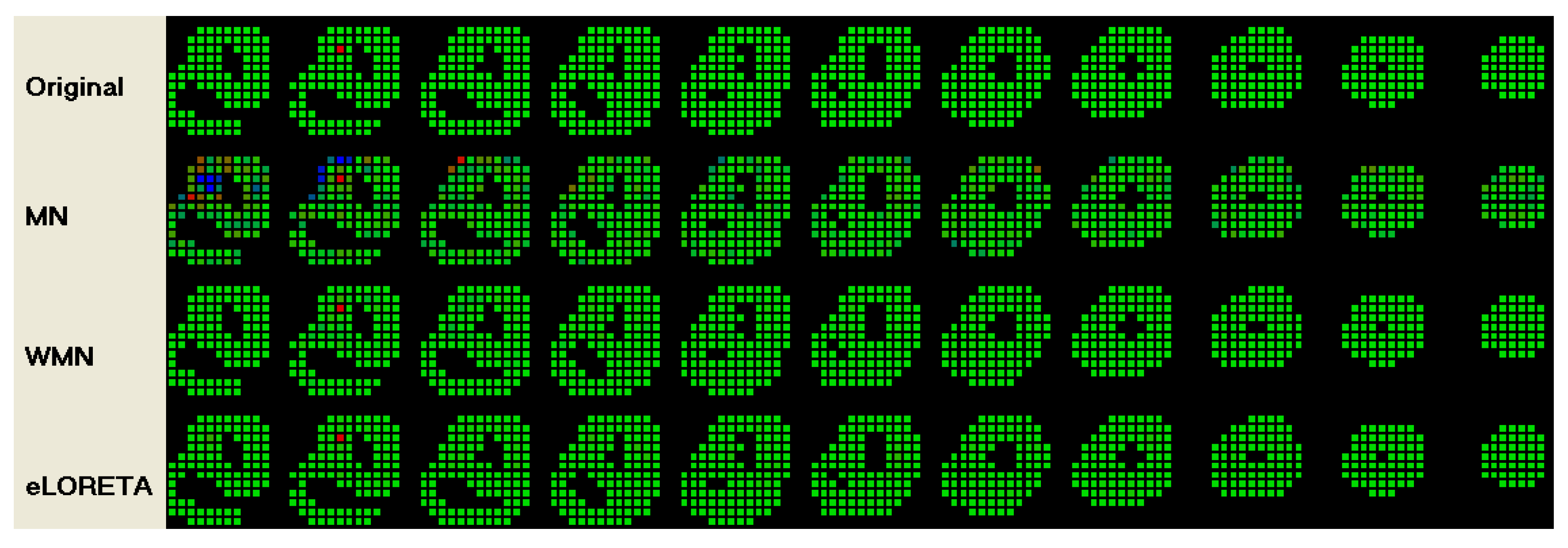

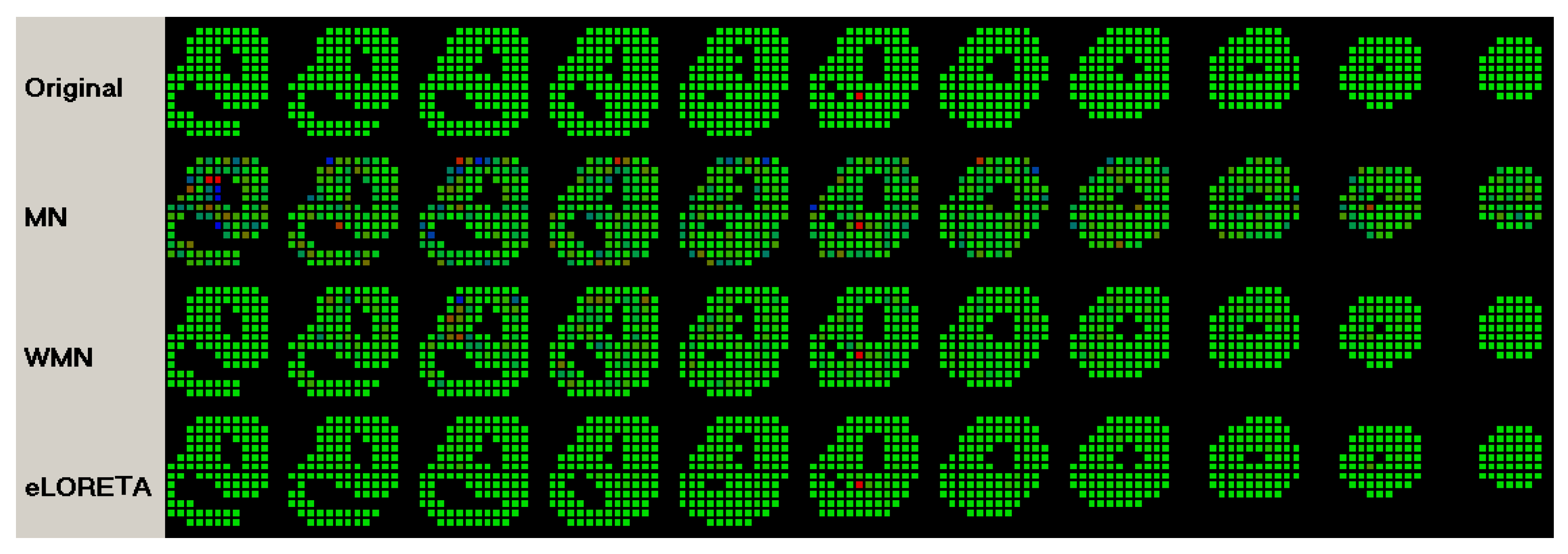

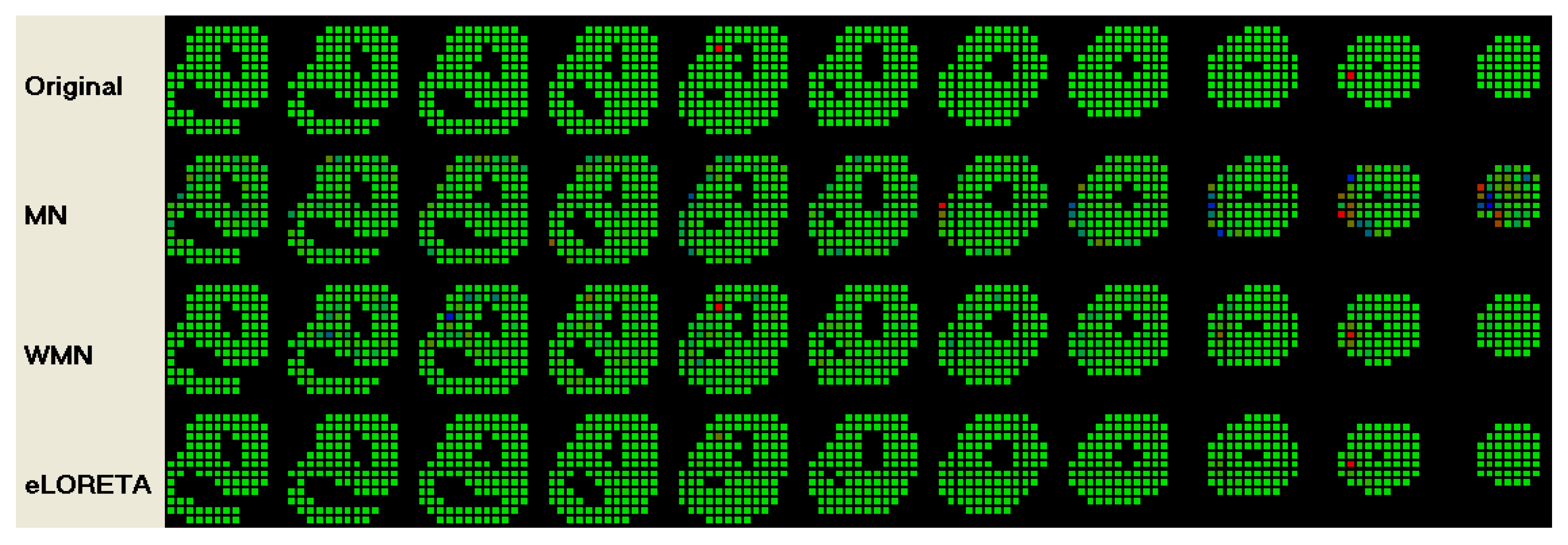

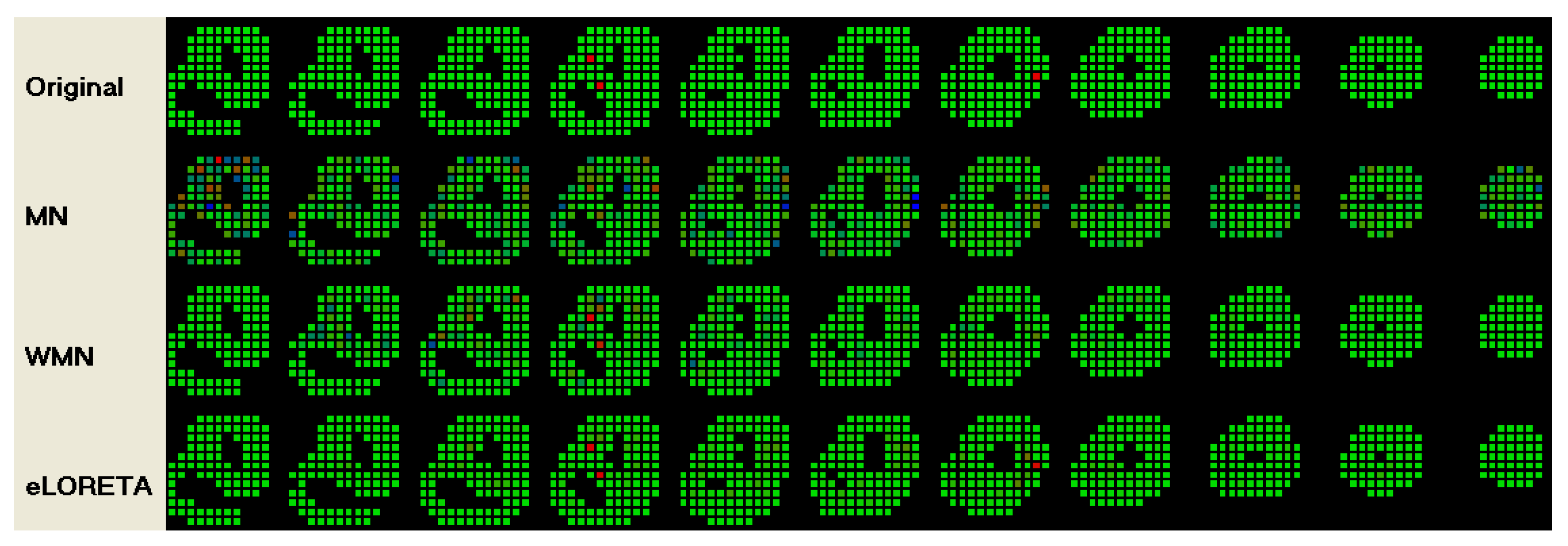

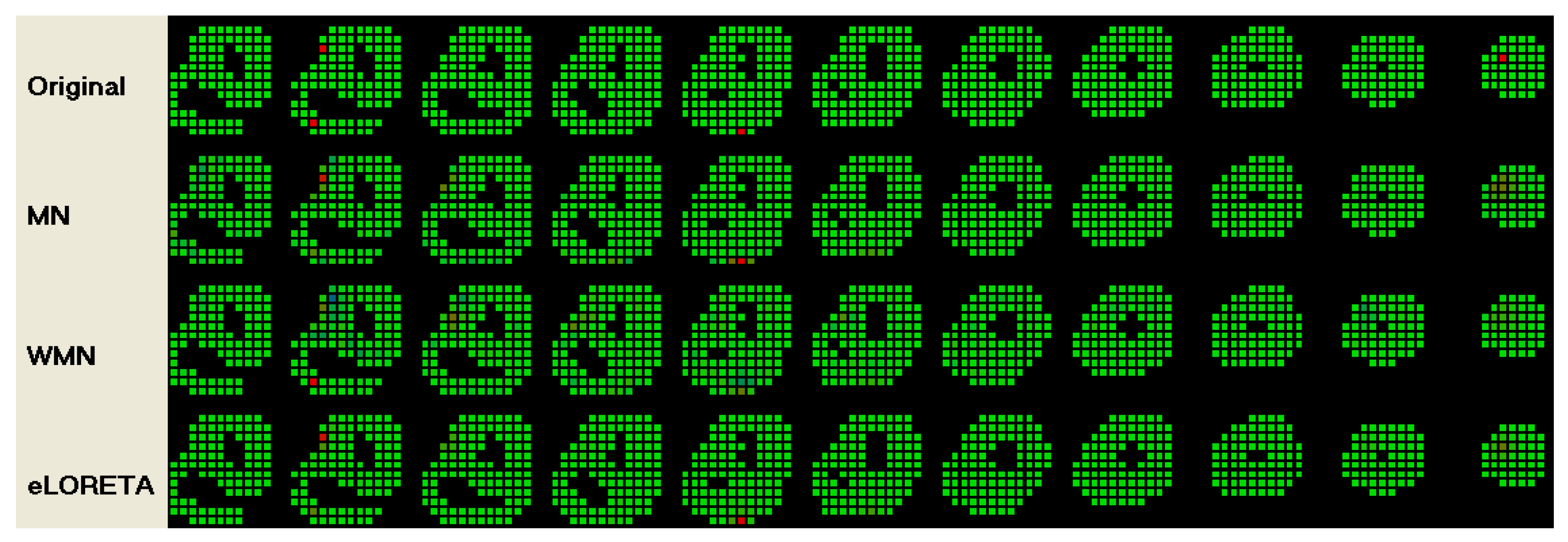

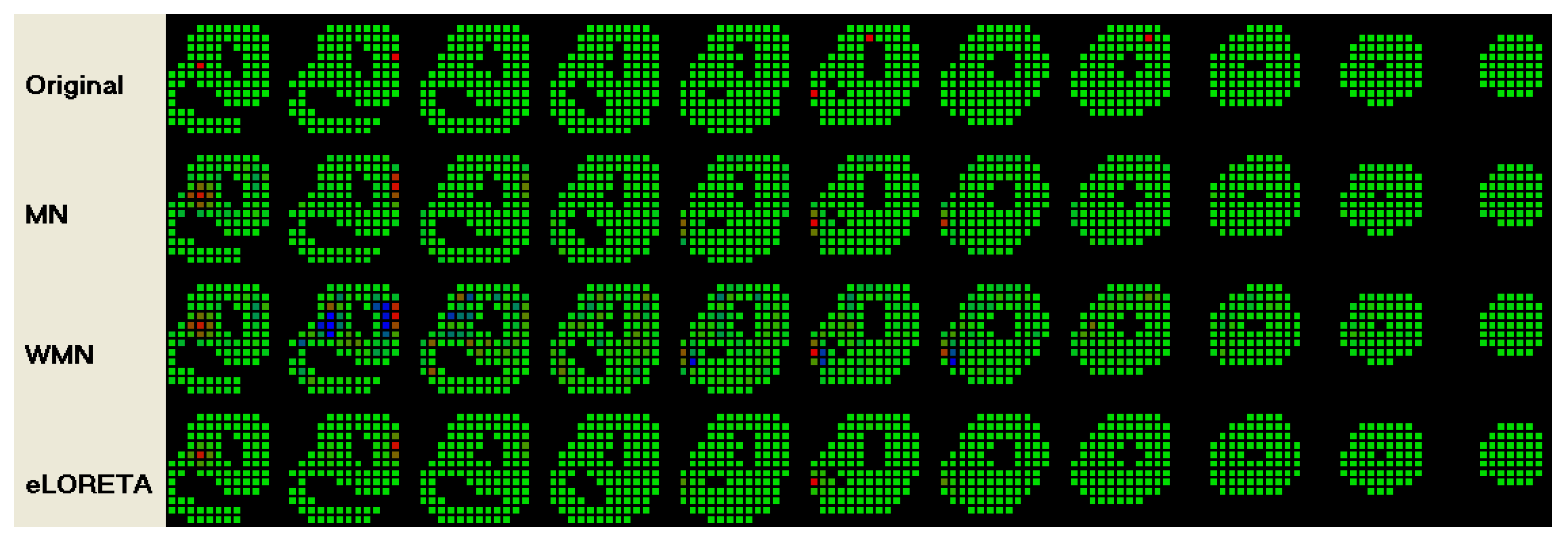

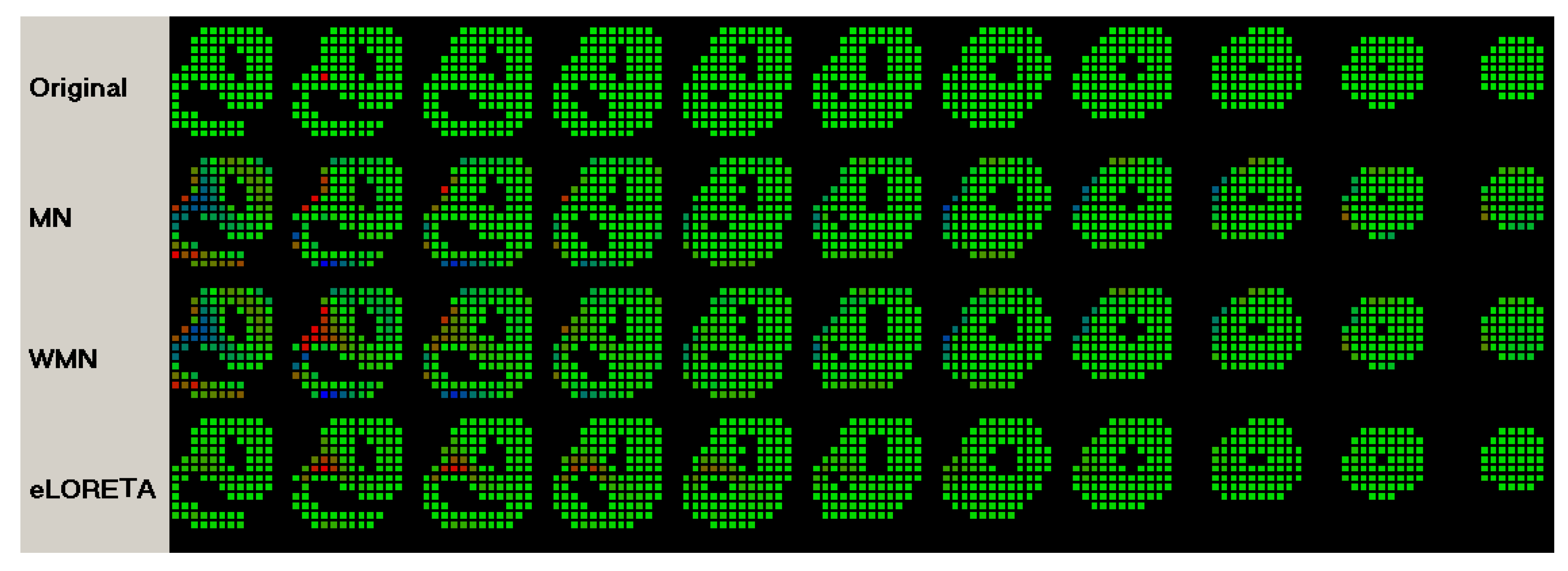

3. Results

4. Conclusion

References

- J. Malmivuo and R. Plonsey "Bioelectromagnetism: Principles and Applications of Bioelectric and Biomagnetic Fields" Oxford Univ. Press, 1st Ed., (1995); ISBN: 0195058232.

- M. Lorange, and R. M. Gulrajani "A computer Heart Model Incorporating Anisotropic Propagation" Journal of Electrocardiology, (1993);26(4):245-261. [CrossRef]

- M. Seger "Modeling the Electrical Function of the Human Heart", Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Austria (2006).

- D.H. Brooks and R.S. MacLeody "Electrical Imaging of the Heart: Electrophysical Underpinnings and Signal Processing Opportunities" IEEE Signal Processing, (1996); 14(1):24-42.

- C. Hintermuller "Development of a Multi-Lead ECG Array for Noninvasive Imaging of the Cardiac Electrophysiology", Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology,Austria, (2006).

- BJ Messinger-Rapport and Y. Rudy "Noninvasive recovery of epicardial potentials in a realistic heart- torso geometry.Normal sinus rhythm" American Heart Association (1990);66;1023-1039. [CrossRef]

- H.S. Oster, B.Taccardi, R.L. Lux, P.R. Ershler and Y. Rudy "Electrocardiographic Imaging : Noninvasive Characterization of Intramural Myocardial Activation From Inverse-Reconstructed Epicardial Potentials and Electrograms" American Heart Association (1998);97:1496-1507. [CrossRef]

- T. Berger, G. Fischer, B. Pfeifer, R. Modre, F. Hanser,T. Trieb, F. X. Roithinger, M. Stuehlinger, O. Pachinger,B. Tilg, and F. Hintringer "Single-Beat Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Electrophysiology of Ventricular Pre-Excitation" J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (2006);48:2045-2052. [CrossRef]

- L. Cheng "Non-Invasive Electrical Imaging of the Heart", Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Auckland, New Zealand (2001).

- C. Ramanathan, P. Jia, R. Ghanem, D. Calvetti, and Y. Rudy "Noninvasive Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI):Application of the Generalized Minimal Residual (GMRes) Method" Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2003; 31(8): 981–994. [CrossRef]

- R. N. Ghanem,P. Jia, C. Ramanathan, K. Ryu, A. Markowitz, and Y. Rudy "Noninvasive Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI): Comparison to intraoperative mapping in patients" Heart Rhythm. 2005; 2(4): 339–354. [CrossRef]

- A. Intini, R. N. Goldstein, P. Jia, C. Ramanathan,K.Ryu, B.Giannattasio,R.Gilkeson,B.S. Stambler,P. Brugada,W. G. Stevenson, Y. Rudy, and A. L. Waldo "Electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI), a novel diagnostic modality used for mapping of focal left ventricular tachycardia in a young athlete" Heart Rhythm. 2005; 2(11): 1250–1252. [CrossRef]

- P. Jia,C. Ramanathan,R.N. Ghanem,K. Ryu,N. Varma,and Y. Rudy "Electrocardiographic imaging of cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure: Observation of variable electrophysiologic responses" Heart Rhythm. 2006; 3(3): 296–310. [CrossRef]

- R.N. Ghanem, C. Ramanathan, P.Jia, and Y. Rudy "Heart-Surface Reconstruction and ECG Electrodes Localization Using Fluoroscopy, Epipolar Geometry and Stereovision:Application to Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Electrical Activity" IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2003; 22(10): 1307–1318. [CrossRef]

- T.Berger, F.Hintringer, G. Fischer, "Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Electrophysiology" Indian Pacing and Electrophysiology Journal, 2007; 7(3): 160-165.

- C. Ramanathan, R.N. Ghanem, P. Jia, K. Ryu, and Y. Rudy "Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging for cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmia" Nat Med. 2004; 10(4): 422–428. [CrossRef]

- S. Ghosh and Y. Rudy "Accuracy of Quadratic Versus Linear Interpolation in Noninvasive Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI)" Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2005; 33(9): 1187–1201. [CrossRef]

- M. Seger, R. Modre, B. Pfeifer, C. Hintermuller and B. Tilg "Non-invasive Imaging of Atrial Flutter" Computers in Cardiology (2006);33:601-604.

- X. Zhang, I. Ramachandra, Z. Liu, B. Muneer, S.M. Pogwizd, and B. He "Noninvasive three-dimensional electrocardiographic imaging of ventricular activation sequence" Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol (2005); 289: H2724–H2732. [CrossRef]

- C.G. Xanthis, P.M. Bonovas, and G.A. Kyriacou "Inverse Problem of ECG for Direrent Equivalent Cardiac Sources" PIERS Online, 2007; 3(8): 1222-1227.

- B. He, G.Li, and X. Zhang "Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Transmembrane Potentials Within Three-Dimensional Myocardium by Means of a Realistic Geometry Anisotropic Heart Model" IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. (2003); 50(10): 1190-1202. [CrossRef]

- B. He, and D. Wu "Imaging and Visualization of 3-D Cardiac Electric Activity" IEEE Tran. Inf Tech. Biomed. 2001; 5(3): 181-186. [CrossRef]

- G. Li, X. Zhang, J. Lian, and B. He "Noninvasive Localization of the Site of Origin of Paced Cardiac Activation in Human by Means of a 3-D Heart Model" IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. (2003); 50(9): 1117-1120. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, C. Liu, and B. He "Noninvasive Reconstruction of Three-Dimensional Ventricular Activation Sequence From the Inverse Solution of Distributed Equivalent Current Density" IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. (2006); 25(10): 1307-1318. [CrossRef]

- B. He, C. Liu ,and Y. Zhang "Three-Dimensional Cardiac Electrical Imaging From Intracavity Recordings" IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. (2007); 54(8): 1454-1460. [CrossRef]

- ELAFF I., “Formulation of the Transfer Matrix of the Invers Electrophysiology of the Heart Activation Inside Homogeneous and Inhomogeneous Volume Conductor”. Preprints 2025, 2025072286.

- R.D. Pascual-Marqui "Review of Methods for Solving the EEG Inverse Problem" Intr. J. Bioelectromagnetism (1999); 1(1): 75-86.

- R.S. MacLeod and D.H. Brooks "Recent Progress in Inverse Problems in Electrocardiology" (1998) University of Utah. [CrossRef]

- M.J.M. Cluitmans "Investigation of Electrocardiographic Imaging as a Medical Tool" Electrocardiographic Imaging as a Medical Tool, 2007.

- M. Burger "Inverse Problems" Lecture Notes, The Department of Computational and Applied Mathematics, University of Münster, (2007).

- G. Rodriguez "An algorithm for estimating the optimal regularization parameter by the L-curve" Rendiconti di Matematica, Serie VII (2005); 25: 69-84.

- S. Oraintara, W.C. Karl, D.A. Castanon and T.Q. Nguyen "A Method for Choosing the Regularization Parameter in Generalized Tikhonov Regularized Linear Inverse Problems" Multi-Dimensional Signal Processing Laboratory, Boston University. [CrossRef]

- M.E.Kilmer and D.P. O'Leary "Choosing Regularization Parameter in Iterative Methods for ill-posed Problems" SIAM J. on Matrix Analy. and App., (2000); 22(4): 1204 - 1221. [CrossRef]

- D. Krawczyk-Stando, M. Rudnicki "Regularization Parameter Selection in Discrete ill–Posed Problems —The use of the U–Curve" Int. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci., (2007); 17(2): 157–164.

- LORETA Site "https://www.uzh.ch/keyinst/loreta", July 2025.

- R.D. Pascual-Marqui, C.M. Michel, and D. Lehman "Low resolution electromagnetic tomography: A new method for localizing electrical activity in the brain" Inter. J. of Psych, (1994); 18: 49-65. [CrossRef]

- R.D. Pascual-Marqui, M. Esslen, K. Kochi and D. Lehman "Functional imaging with low resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (LORETA): a review" Methods & Findings in Experimental & Clinical Pharmacology, (2002); 24(C):91-95.

- R.D. Pascual-Marqui "Review of Methods for Solving the EEG Inverse Problem" Inter. J. of Bioelectromagnetism, (1999); 1(1):75-86.

- R.D. Pascual-Marqui "Discrete, 3D distributed linear imaging methods of electric neuronal activity. Part 1: exact, zero error localization" The KEY Institute for Brain-Mind Research, University Hospital of Psychiatry Lenggstr, Switzerland, (2007); arXiv:0710.3341 [math-ph].

- R.D. Pascual-Marqui "Standardized low resolution brain electromagnetic tomography (sLORETA): technical details" Methods & Findings in Experimental & Clinical Pharmacology (2002); 24(D):5-12.

- J.P. Russell and Z.J. Koles "A Comparison of LORETA and the Borgiotti-Kaplan Beamformer in Simulated EEG Source Localization with a Realistic Head Model" Inter. J. of Bioelectromagnetism (2007); 9(2): 97-98.

- R.G. de Peralta Menendez and S.G. Andino "Comparison of Algorithms for the Localization of Focal Sources: Evaluation with Simulated Data and Analysis of Experimental Data" Inter. J. of Bioelectromagnetism (IJBEM), (2002); 4(1): online.

- ALGLIB Site “http://www.alglib.net/”, July 2025.

- G.K. Massing, and T.N. James "Anatomical Configuration of the His Bundle and Bundle Branches in the Human Heart" Circ. (1976); 53(4):609-621. [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. “Modeling of the Human Heart in 3D Using DTI Images”, World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences, 2025, 15(02), 2450-2459. [CrossRef]

- El-Aff, I.A.I. "Extraction of human heart conduction network from diffusion tensor MRI" The 7th IASTED International Conference on Biomedical Engineering, 217-22. [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. “Modeling the Human Heart Conduction Network in 3D using DTI Images”, World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences, 2025, 15(02), 2565–2575. [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. "Modeling of realistic heart electrical excitation based on DTI scans and modified reaction diffusion equation" Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences: 2018, 26(3): Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. “Modeling of The Excitation Propagation of The Human Heart”, World Journal of Biology Pharmacy and Health Sciences, 2025, 22(02): 512–519. [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. “Modeling of 3D Inhomogeneous Human Body from Medical Images”, World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences. 2025, 15(02): 2010-2017. [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. “Modeling of the Body Surface Potential Map for Anisotropic Human Heart Activation”, Research Square, 2025. [CrossRef]

| # of | eLORETA | WMN | MN | ||||

| Sources | Electrodes | CC | RE | CC | RE | CC | RE |

| 1 | 200 | 0.813 ±0.076 |

0.712 ±0.210 |

0.305 ±0.170 |

3.277 ±1.329 |

0.353 ±0.261 |

3.543 ±2.324 |

| 2 | 200 | 0.657 ±0.104 |

0.830 ±0.170 |

0.279 ±0.125 |

2.486 ±0.910 |

0.364 ±0.197 |

1.996 ±1.195 |

| 3 | 200 | 0.606 ±0.109 |

0.826 ±0.126 |

0.312 ±0.097 |

1.946 ±0.644 |

0.408 ±0.172 |

1.424 ±0.880 |

| 4 | 200 | 0.575 ±0.104 |

0.842 ±0.110 |

0.286 ±0.086 |

1.804 ±0.486 |

0.376 ±0.159 |

1.406 ±0.786 |

| 5 | 200 | 0.563 ±0.095 |

0.836 ±0.079 |

0.298 ±0.072 |

1.609 ±0.397 |

0.404 ±0.134 |

1.168 ±0.480 |

| 1 | 100 | 0.518 ±0.144 |

1.771 ±0.610 |

0.229 ±0.133 |

4.229 ±2.155 |

0.232 ±0.221 |

3.933 ±2.164 |

| 2 | 100 | 0.432 ±0.108 |

1.420 ±0.440 |

0.234 ±0.096 |

2.667 ±1.231 |

0.257 ±0.172 |

2.559 ±1.566 |

| 3 | 100 | 0.419 ±0.099 |

1.177 ±0.268 |

0.225 ±0.070 |

2.087 ±0.569 |

0.298 ±0.133 |

1.634 ±0.725 |

| 4 | 100 | 0.385 ±0.114 |

1.157 ±0.262 |

0.224 ±0.077 |

1.945 ±0.627 |

0.279 ±0.128 |

1.654 ±0.899 |

| 5 | 100 | 0.393 ±0.105 |

1.079 ±0.167 |

0.232 ±0.073 |

1.721 ±0.422 |

0.296 ±0.112 |

1.359 ±0.393 |

| 1 | 64 | 0.375 ±0.110 |

2.699 ±0.908 |

0.203 ±0.119 |

4.419 ±1.803 |

0.181 ±0.156 |

3.954 ±1.754 |

| 2 | 64 | 0.313 ±0.084 |

2.027 ±0.665 |

0.181 ±0.086 |

3.345 ±1.380 |

0.175 ±0.117 |

3.045 ±1.347 |

| 3 | 64 | 0.285 ±0.082 |

1.629 ±0.407 |

0.184 ±0.077 |

2.502 ±1.000 |

0.201 ±0.097 |

2.244 ±1.005 |

| 4 | 64 | 0.282 ±0.076 |

1.509 ±0.374 |

0.185 ±0.066 |

2.191 ±0.756 |

0.203 ±0.090 |

1.963 ±0.766 |

| 5 | 64 | 0.276 ±0.065 |

1.436 ±0.297 |

0.194 ±0.062 |

1.918 ±0.512 |

0.225 ±0.074 |

1.665 ±0.449 |

| 1 | 32 | 0.277 ±0.080 |

3.784 ±1.270 |

0.150 ±0.107 |

4.860 ±1.662 |

0.136 ±0.131 |

4.373 ±1.740 |

| 2 | 32 | 0.230 ±0.060 |

2.727 ±0.895 |

0.146 ±0.079 |

3.651 ±1.356 |

0.142 ±0.099 |

3.295 ±1.425 |

| 3 | 32 | 0.215 ±0.047 |

2.264 ±0.627 |

0.152 ±0.069 |

2.902 ±0.984 |

0.155 ±0.085 |

2.662 ±0.953 |

| 4 | 32 | 0.211 ±0.044 |

1.954 ±0.493 |

0.157 ±0.051 |

2.384 ±0.645 |

0.164 ±0.063 |

2.226 ±0.689 |

| 5 | 32 | 0.207 ±0.049 |

1.853 ±0.410 |

0.162 ±0.057 |

2.258 ±0.648 |

0.171 ±0.066 |

2.116 ±0.637 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).