Submitted:

12 June 2025

Posted:

13 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

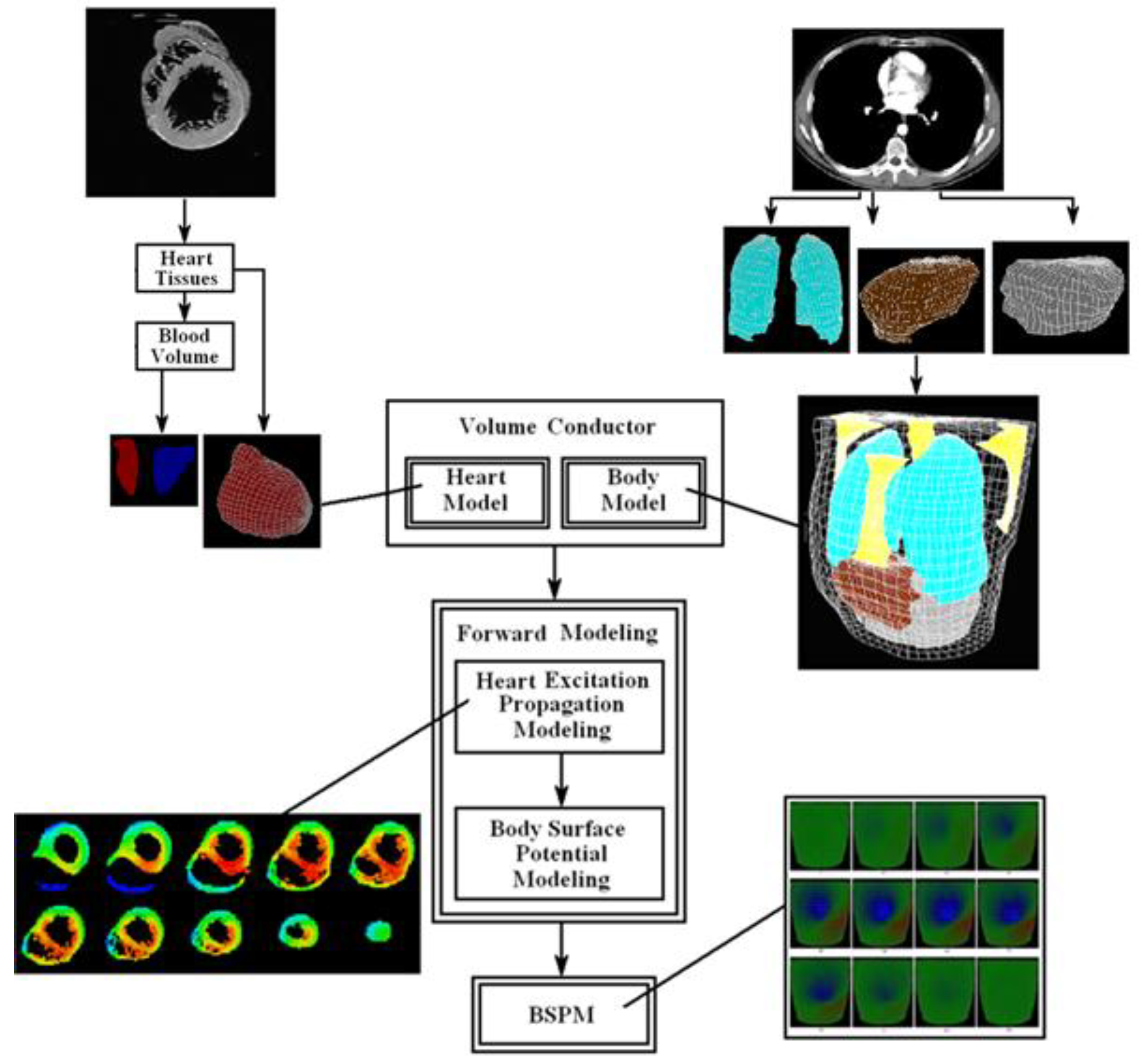

2. Methods

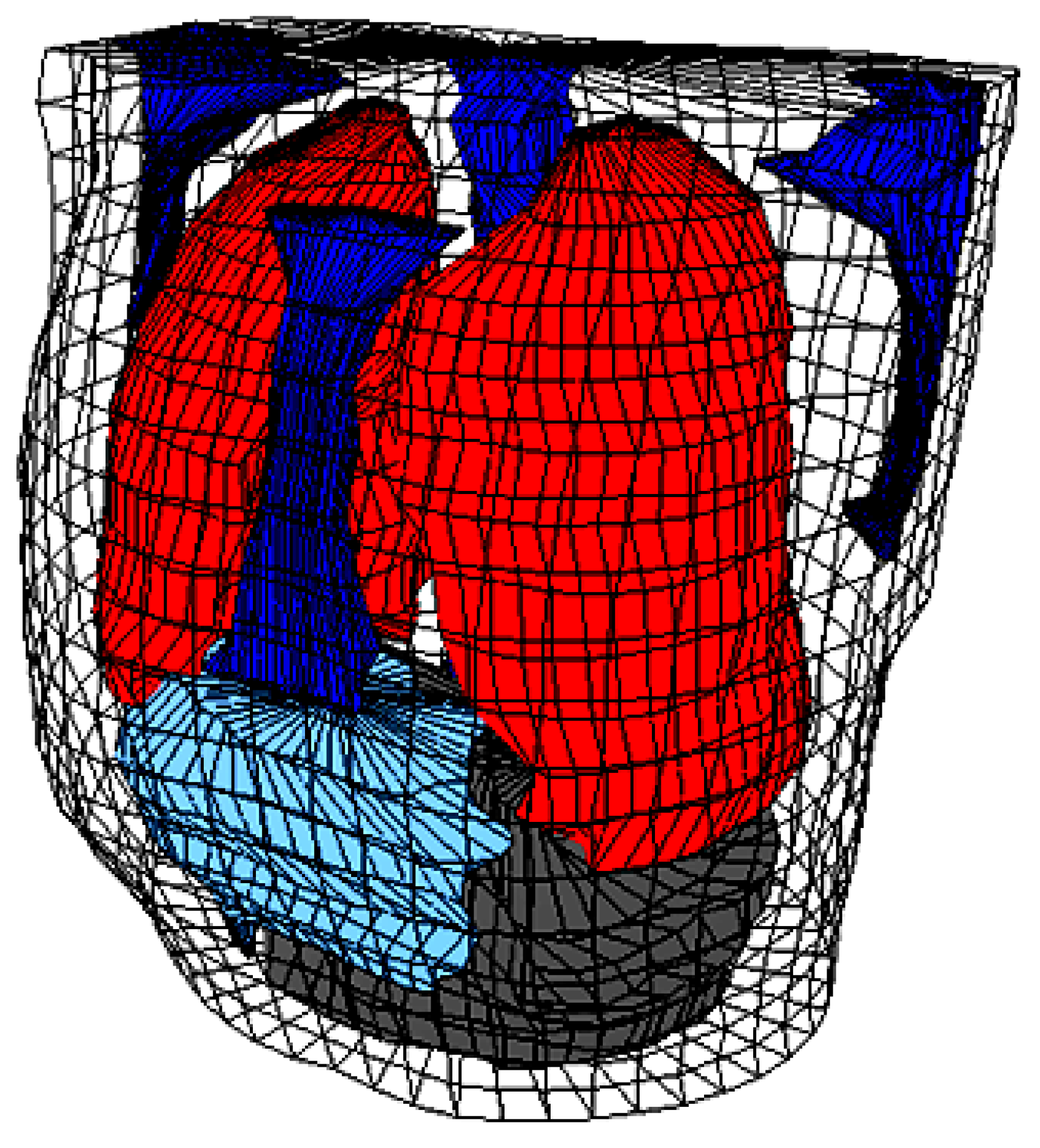

2.1. The Human Torso and the Human Heart Modeling

| Organ/Tissue | Resistivity (Ωcm) |

Conductivity (mS/mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Skeletal muscle | 400 | 25 |

| Fats | 2000 | 5 |

| Bone | 2000 | 5 |

| Liver | 600 | 16.7 |

| Left lung, right lung | 1325 | 7.5 |

| Blood masses | 150 | 66.7 |

| Other tissues and organs | 460 | 21.7 |

| Heart muscle | 450 | 22.2 |

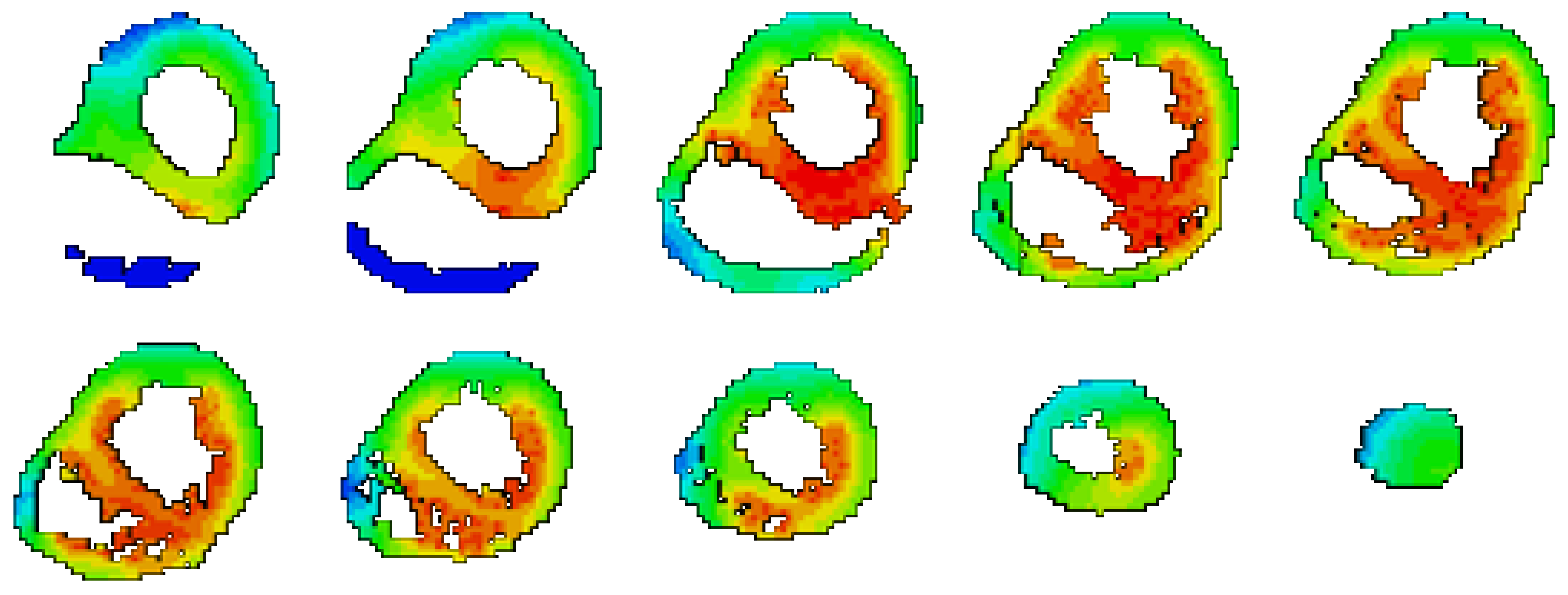

2.2. Heart Activation Isochrones

2.3. Body Surface Potential Map

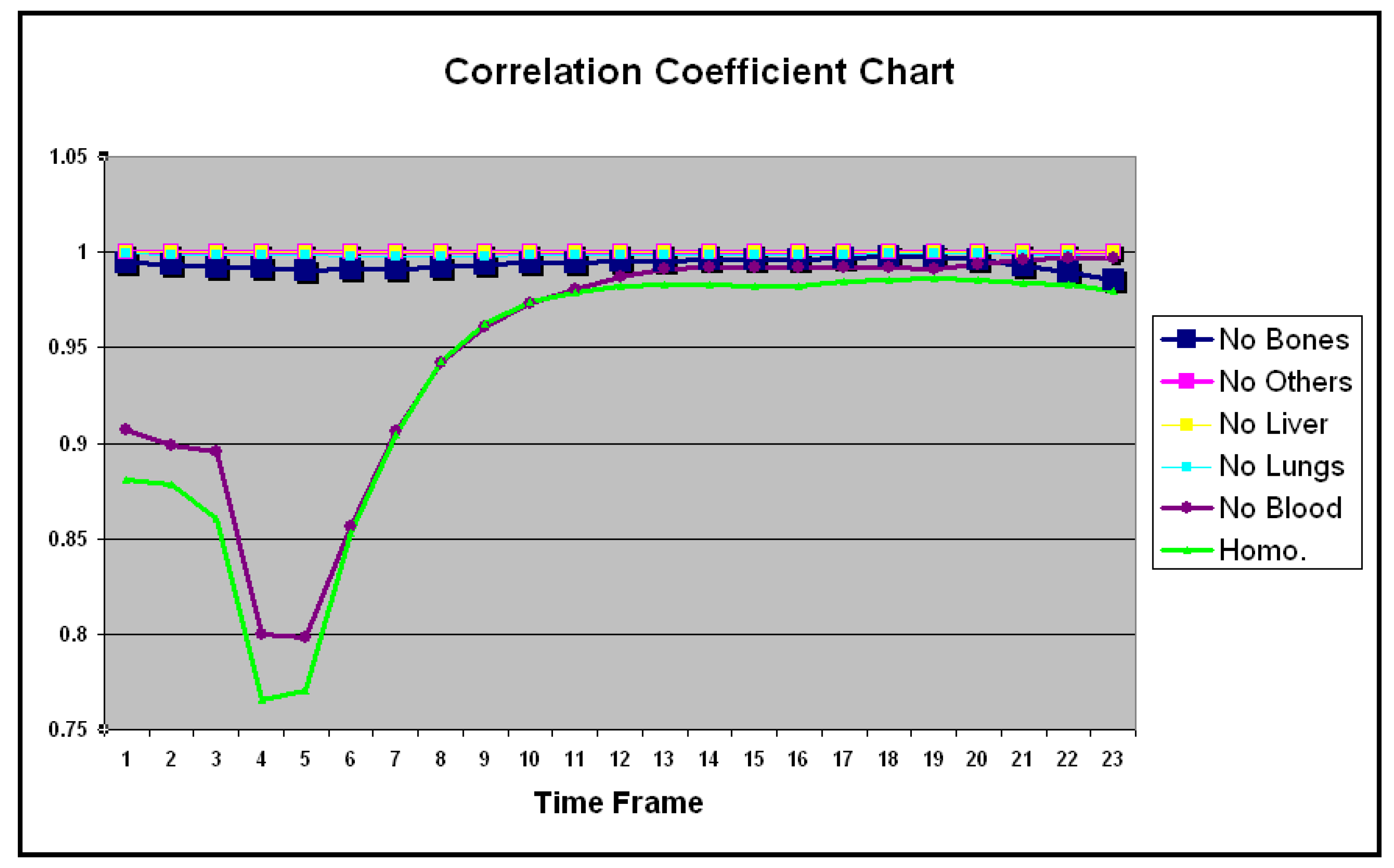

3. Results

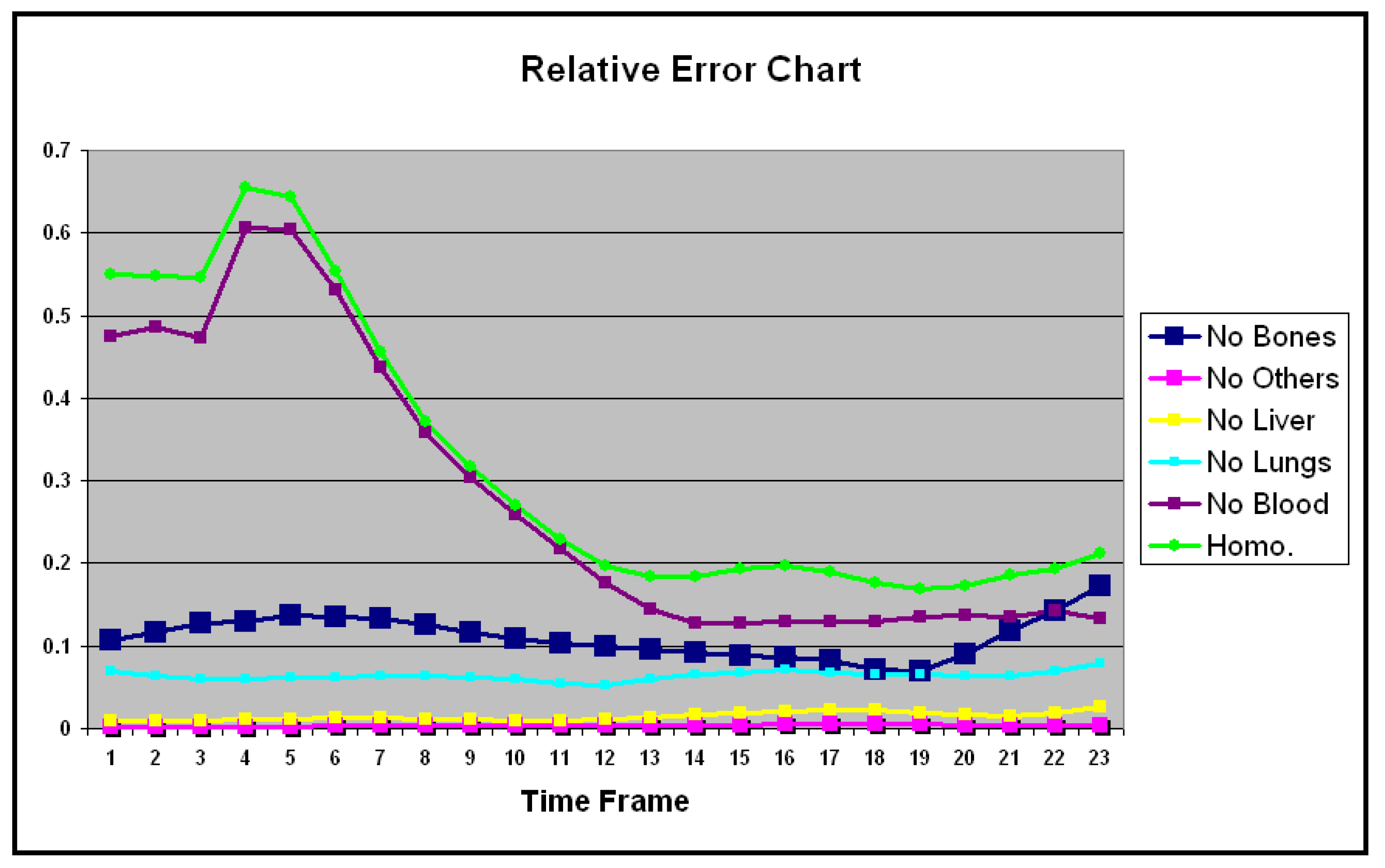

- Removing Bones only.

- Removing Other organs only.

- Removing Liver only.

- Removing Lungs only.

- Removing Blood Volume only.

- Homogeneous body.

- The Blood Volume.

- The Bones.

- The Lungs.

- The Liver.

- Any Other organs.

4. Conclusions

References

- J. Malmivuo and R. Plonsey “Bioelectromagnetism: Principles and Applications of Bioelectric and Biomagnetic Fields” Oxford Univ. Press, 1st Ed., (1995); ISBN: 0195058232.

- R.M. Gulrajani and G.E. Mailloux “A simulation study of the effects of torso inhomogeneities on electrocardiographic potentials, using realistic heart and torso models” Circ. Res., (1983); 52:45-56.

- K. Simeliusa, J. Nenonena, M. Horácekb “Modeling Cardiac Ventricular Activation” Inter. J. of Bioelectromagnetism, (2001); 3(2):51 - 58.

- X. Zhang, I. Ramachandra, Z. Liu, B. Muneer, S.M. Pogwizd, and B. He “Noninvasive three-dimensional electrocardiographic imaging of ventricular activation sequence” Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol (2005); 289: H2724–H2732.

- G. Li, X. Zhang, J. Lian, and B. He “Noninvasive Localization of the Site of Origin of Paced Cardiac Activation in Human by Means of a 3-D Heart Model” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. (2003); 50(9): 1117-1120.

- Z. Liu, C. Liu, and B. He “Noninvasive Reconstruction of Three-Dimensional Ventricular Activation Sequence From the Inverse Solution of Distributed Equivalent Current Density” IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. (2006); 25(10): 1307-1318.

- V. Jazbinsek, R. Hren, and Z. Trontelj “High resolution ECG and MCG mapping: simulation study of single and dual accessory pathways and influence of lead displacement and limited lead selection on localisation results” Bulletin of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Technical Sciences, (2005); 53(3): 195-205.

- L.W. Wang, H.Y. Zhang, P.C. Shi “Simultaneous Recovery of Three-dimensional Myocardial Conductivity and Electrophysiological Dynamics: A Nonlinear System Approach” Computers in Cardiology, (2006);33:45-48.

- L. Cheng “Non-Invasive Electrical Imaging of the Heart”, Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Auckland,New Zealand (2001).

- D.S. Farina, O. Skipa, C. Kaltwasser, O. Dossel and W.R. Bauer “Personalized Model of Cardiac Electrophysiology of a Patient” IJBEM (2005);7(1): 303-306.

- M. Seger “Modeling the Electrical Function of the Human Heart”, Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Austria (2006).

- M. Lorange, and R. M. Gulrajani “A computer Heart Model Incorporating Anisotropic Propagation” Journal of Electrocardiology, (1993);26(4):245-261.

- C. Hintermuller “Development of a Multi-Lead ECG Array for Noninvasive Imaging of the Cardiac Electrophysiology”, Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology,Austria, (2006).

- T. Berger, G. Fischer, B. Pfeifer, R. Modre, F. Hanser,T. Trieb, F. X. Roithinger, M. Stuehlinger, O. Pachinger,B. Tilg, and F. Hintringer “Single-Beat Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Electrophysiology of Ventricular Pre-Excitation” J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. (2006);48:2045-2052.

- B.E. Pfeifer “Model-based segmentation techniques for fast volume conductor generation”, Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Austria (2005).

- B. He, and D. Wu “Imaging and Visualization of 3-D Cardiac Electric Activity” IEEE Tran. Inf Tech. Biomed. 2001; 5(3): 181-186.

- M. Seger, R. Modre, B. Pfeifer, C. Hintermuller and B. Tilg “Non-invasive Imaging of Atrial Flutter” Computers in Cardiology (2006);33:601-604.

- C.G. Xanthis, P.M. Bonovas, and G.A. Kyriacou “Inverse Problem of ECG for Different Equivalent Cardiac Sources” PIERS Online, 2007; 3(8): 1222-1227.

- B. He, C. Liu ,and Y. Zhang “Three-Dimensional Cardiac Electrical Imaging From Intracavity Recordings” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. (2007); 54(8): 1454-1460.

- Elaff, I. “Modeling of 3D Inhomogeneous Human Body from Medical Images”, World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences. 2025, 15(02): 2010-2017. [CrossRef]

- D.F. Scollan “Reconstructing The Heart: Development and Application of Biophysically Based Electrical Models of Propagation in Ventricular Myocardium Reconstructed from DTMRI”, Ph.D. Thesis, Johns Hopkins University ( 2002).

- S. Ohyu, Y. Okamoto and S. Kuriki “Use of the Ventricular Propagated Excitation Model in the Magnetocardiographic Inverse Problem for Reconstruction of Electrophysiological Properties” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. (2002); 49(6): 509-518.

- Berenfeld and J. Jalife “Purkinje-Muscle Reentry as a Mechanism of Polymorphic Ventricular, Arrhythmias in a 3-Dimensional Model of the Ventricles” Circ. Res., (1998);82;1063-1077.

- B. He, G.Li, and X. Zhang “Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Transmembrane Potentials Within Three-Dimensional Myocardium by Means of a Realistic Geometry Anisotropic Heart Model” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. (2003); 50(10): 1190-1202.

- V.Soundararajan and W.G. Besio “Simulated Comparison of Disc and Concentric Electrode Maps During Atrial Arrhythmias” IJBEM,(2005); 7(1):217-220.

- BJ Messinger-Rapport and Y. Rudy “Noninvasive recovery of epicardial potentials in a realistic heart- torso geometry.Normal sinus rhythm” American Heart Association (1990);66;1023-1039.

- H.S. Oster, B.Taccardi, R.L. Lux, P.R. Ershler and Y. Rudy “Electrocardiographic Imaging : Noninvasive Characterization of Intramural Myocardial Activation From Inverse-Reconstructed Epicardial Potentials and Electrograms” American Heart Association (1998);97:1496-1507.

- C. Ramanathan, P. Jia, R. Ghanem, D. Calvetti, and Y. Rudy “Noninvasive Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI):Application of the Generalized Minimal Residual (GMRes) Method” Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2003; 31(8): 981–994.

- R. N. Ghanem,P. Jia, C. Ramanathan, K. Ryu, A. Markowitz, and Y. Rudy “Noninvasive Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI): Comparison to intraoperative mapping in patients” Heart Rhythm. 2005; 2(4): 339–354.

- Elaff, I. “Modeling of the Body Surface Potential Map for Anisotropic Human Heart Activation”, Research Square, 2025. [CrossRef]

- G.A. Tan, F. Brauer, G. Stroink and C.J. Purcell “The effect of measurement conditions on MCG inverse solutions”, IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1992; 39(9): 921-927.

- J. Nenonen, C.J. Purell, B.M. Horacek, G. Stroink and T. Katila “Magnetocardiographic functional localization using a current dipole in a realistic torso” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., 1991; 38(7): 658-664.

- C.J. Purcell and G. Stroink “Moving dipole inverse solutions using realistic torso models” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., 1991; 38(1):82-84.

- Elaff, I. “Modeling of the Human Heart in 3D Using DTI Images”, World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences, 2025, 15(02), 2450-2459. [CrossRef]

- El-Aff, I.A.I. “Extraction of human heart conduction network from diffusion tensor MRI” The 7th IASTED International Conference on Biomedical Engineering, 217-22.

- Elaff, I. “Modeling the Human Heart Conduction Network in 3D using DTI Images”, World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences, 2025, 15(02), 2565–2575. [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. “Modeling of realistic heart electrical excitation based on DTI scans and modified reaction diffusion equation” Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences: 2018, 26(3): Article 2.

- Elaff, I. “Modeling of The Excitation Propagation of The Human Heart”, World Journal of Biology Pharmacy and Health Sciences, 2025, 22(02): 512–519. [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. “Effect of the material properties on modeling of the excitation propagation of the human heart”, World Journal of Biology Pharmacy and Health Sciences, 2025, 22(3): 088–094. [CrossRef]

| No Bones | No Others | No Liver | No Lungs | No Blood | Homo. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.907 | 0.880 |

| 2 | 0.993 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.898 | 0.878 |

| 3 | 0.991 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.895 | 0.860 |

| 4 | 0.991 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.800 | 0.765 |

| 5 | 0.990 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.797 | 0.770 |

| 6 | 0.991 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.856 | 0.852 |

| 7 | 0.991 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.906 | 0.904 |

| 8 | 0.992 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.942 | 0.942 |

| 9 | 0.993 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.961 | 0.962 |

| 10 | 0.994 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.972 | 0.973 |

| 11 | 0.994 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.980 | 0.979 |

| 12 | 0.995 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.986 | 0.981 |

| 13 | 0.995 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.990 | 0.983 |

| 14 | 0.995 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.992 | 0.983 |

| 15 | 0.996 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.991 | 0.981 |

| 16 | 0.996 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.991 | 0.982 |

| 17 | 0.996 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.992 | 0.984 |

| 18 | 0.997 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.991 | 0.985 |

| 19 | 0.997 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.991 | 0.985 |

| 20 | 0.996 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.993 | 0.985 |

| 21 | 0.993 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.995 | 0.983 |

| 22 | 0.989 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.996 | 0.983 |

| 23 | 0.985 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.997 | 0.996 | 0.979 |

| Mean | 0.993 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.949 | 0.937 |

| SD | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.061 | 0.068 |

| No Bones | No Others | No Liver | No Lungs | No Blood | Homo. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.106 | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.069 | 0.473 | 0.549 |

| 2 | 0.117 | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.063 | 0.485 | 0.547 |

| 3 | 0.127 | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.060 | 0.473 | 0.546 |

| 4 | 0.129 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.060 | 0.606 | 0.655 |

| 5 | 0.137 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 0.061 | 0.604 | 0.643 |

| 6 | 0.134 | 0.003 | 0.012 | 0.062 | 0.532 | 0.554 |

| 7 | 0.134 | 0.003 | 0.012 | 0.063 | 0.436 | 0.455 |

| 8 | 0.125 | 0.003 | 0.012 | 0.063 | 0.357 | 0.371 |

| 9 | 0.116 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.061 | 0.304 | 0.317 |

| 10 | 0.108 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.059 | 0.259 | 0.270 |

| 11 | 0.102 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.053 | 0.217 | 0.228 |

| 12 | 0.100 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.052 | 0.176 | 0.197 |

| 13 | 0.096 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.059 | 0.144 | 0.184 |

| 14 | 0.091 | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0.064 | 0.128 | 0.183 |

| 15 | 0.088 | 0.004 | 0.018 | 0.068 | 0.127 | 0.193 |

| 16 | 0.086 | 0.004 | 0.021 | 0.070 | 0.130 | 0.197 |

| 17 | 0.081 | 0.005 | 0.023 | 0.068 | 0.130 | 0.189 |

| 18 | 0.071 | 0.005 | 0.023 | 0.065 | 0.129 | 0.176 |

| 19 | 0.069 | 0.004 | 0.018 | 0.065 | 0.134 | 0.168 |

| 20 | 0.089 | 0.004 | 0.015 | 0.064 | 0.136 | 0.172 |

| 21 | 0.117 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.063 | 0.135 | 0.185 |

| 22 | 0.142 | 0.002 | 0.017 | 0.070 | 0.141 | 0.193 |

| 23 | 0.172 | 0.003 | 0.026 | 0.079 | 0.132 | 0.211 |

| Mean | 0.110 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.063 | 0.278 | 0.321 |

| SD | 0.024 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.171 | 0.170 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).