Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

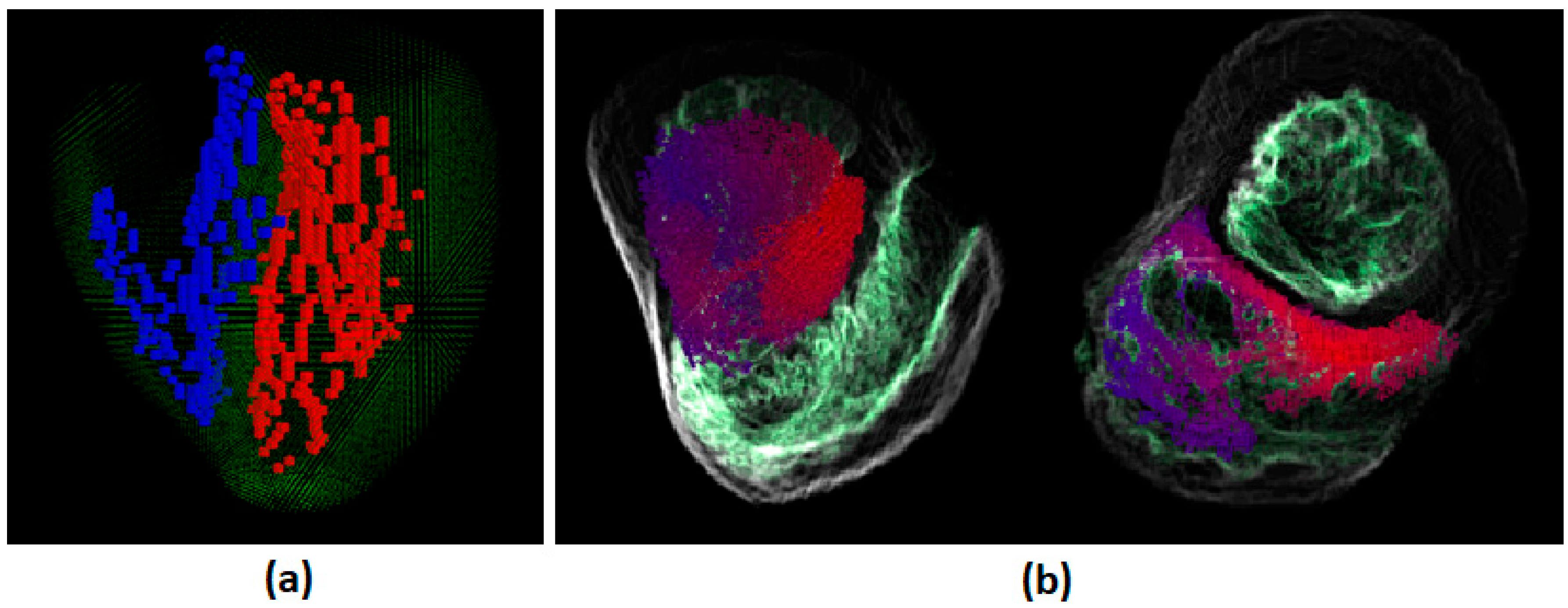

2.1. The Human Torso and the Human Heart Modeling

2.2. The Conduction Network Modeling

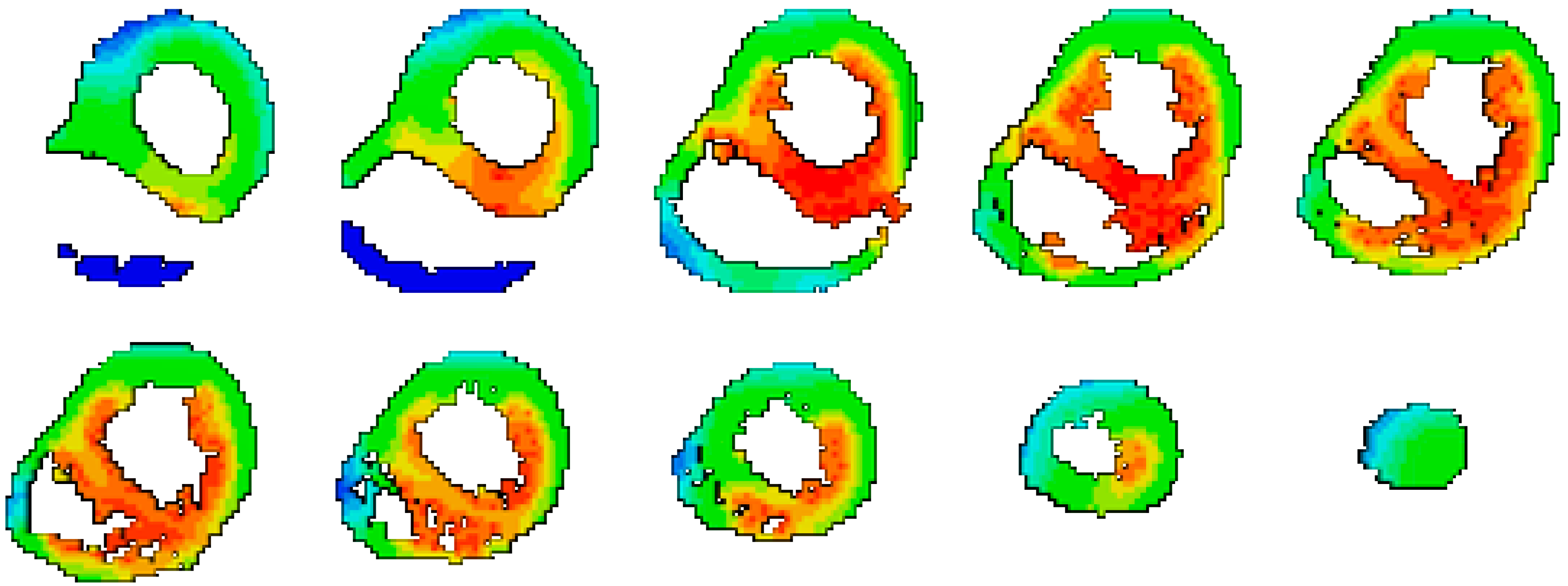

2.3. Activation Isochrones Modeling

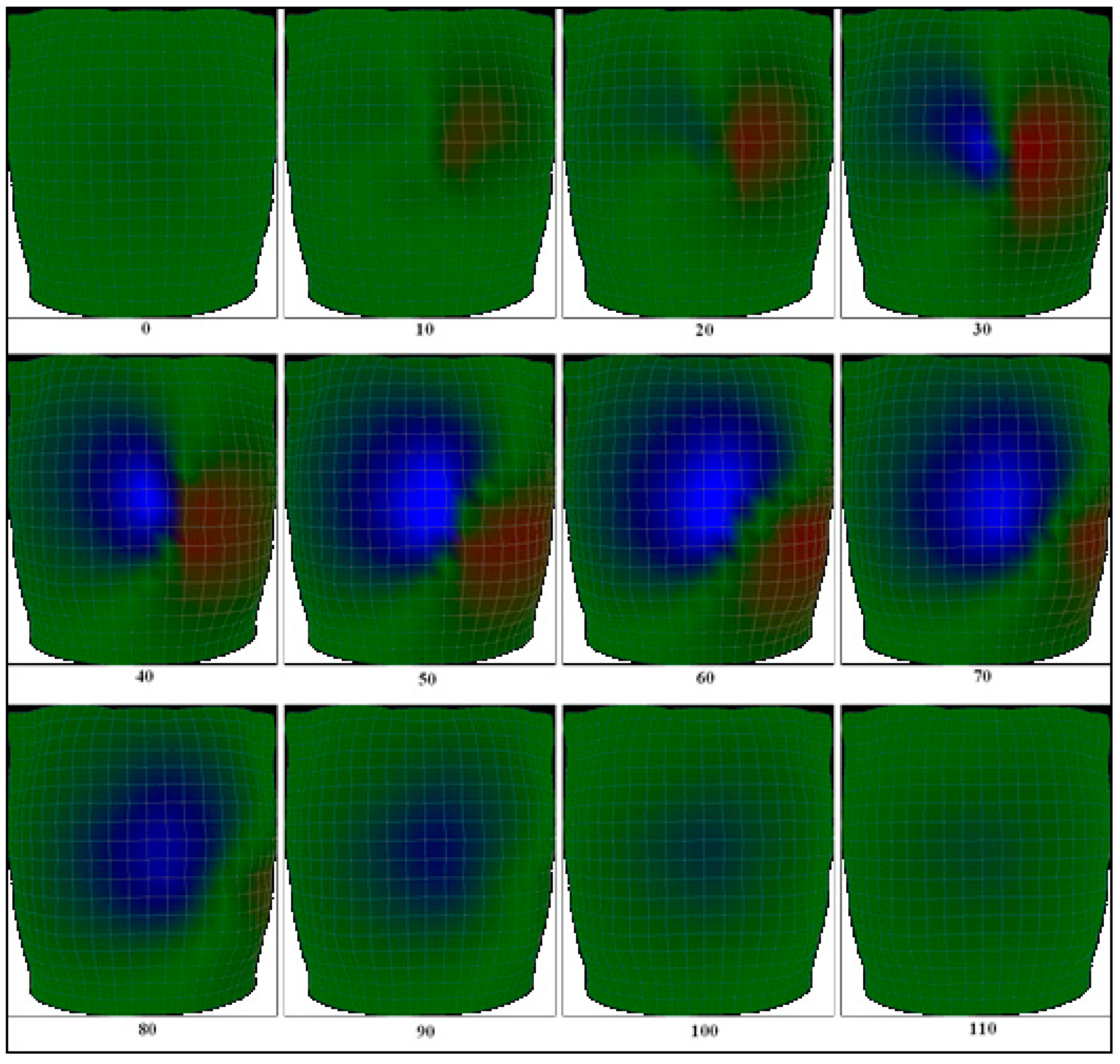

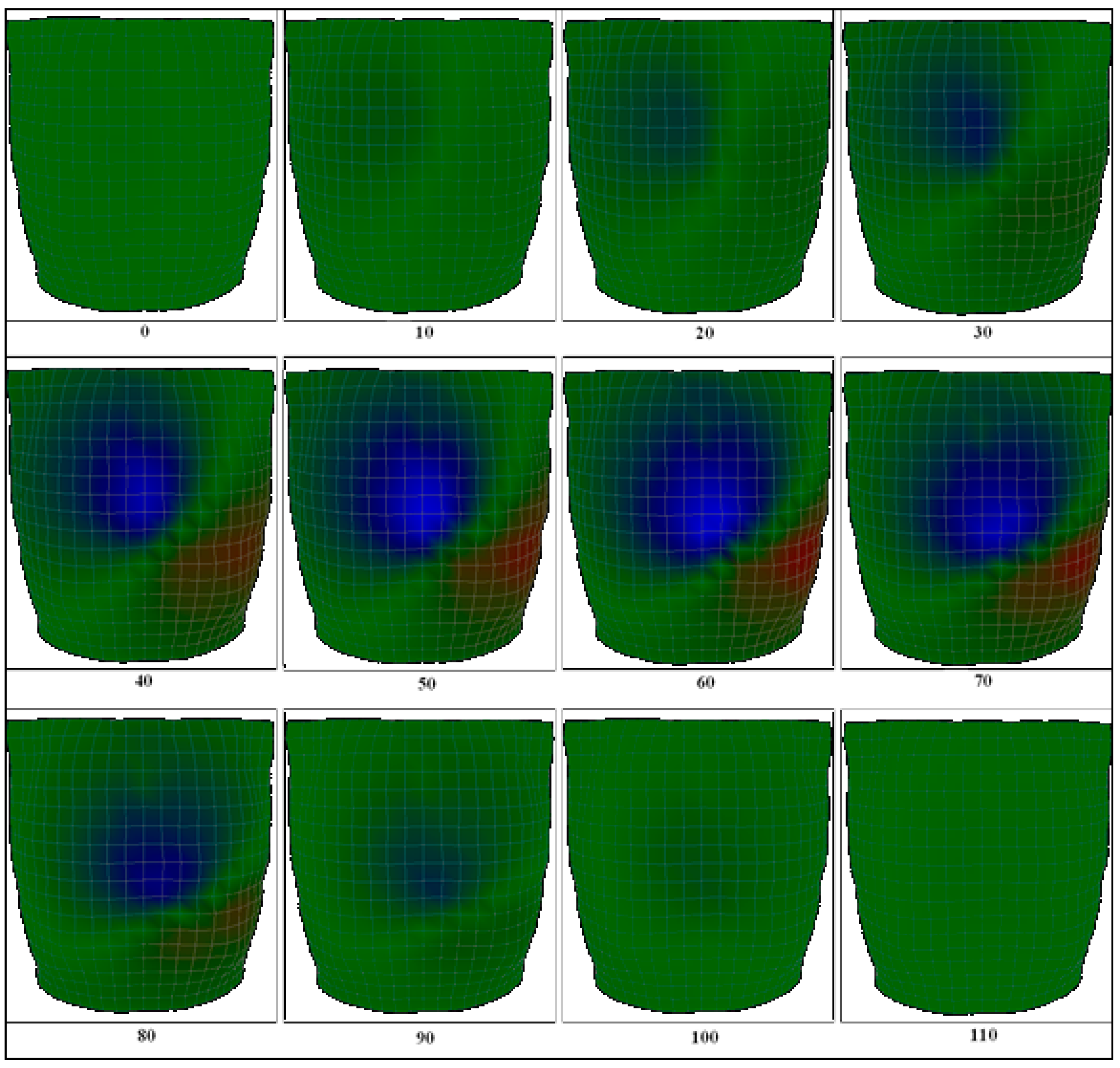

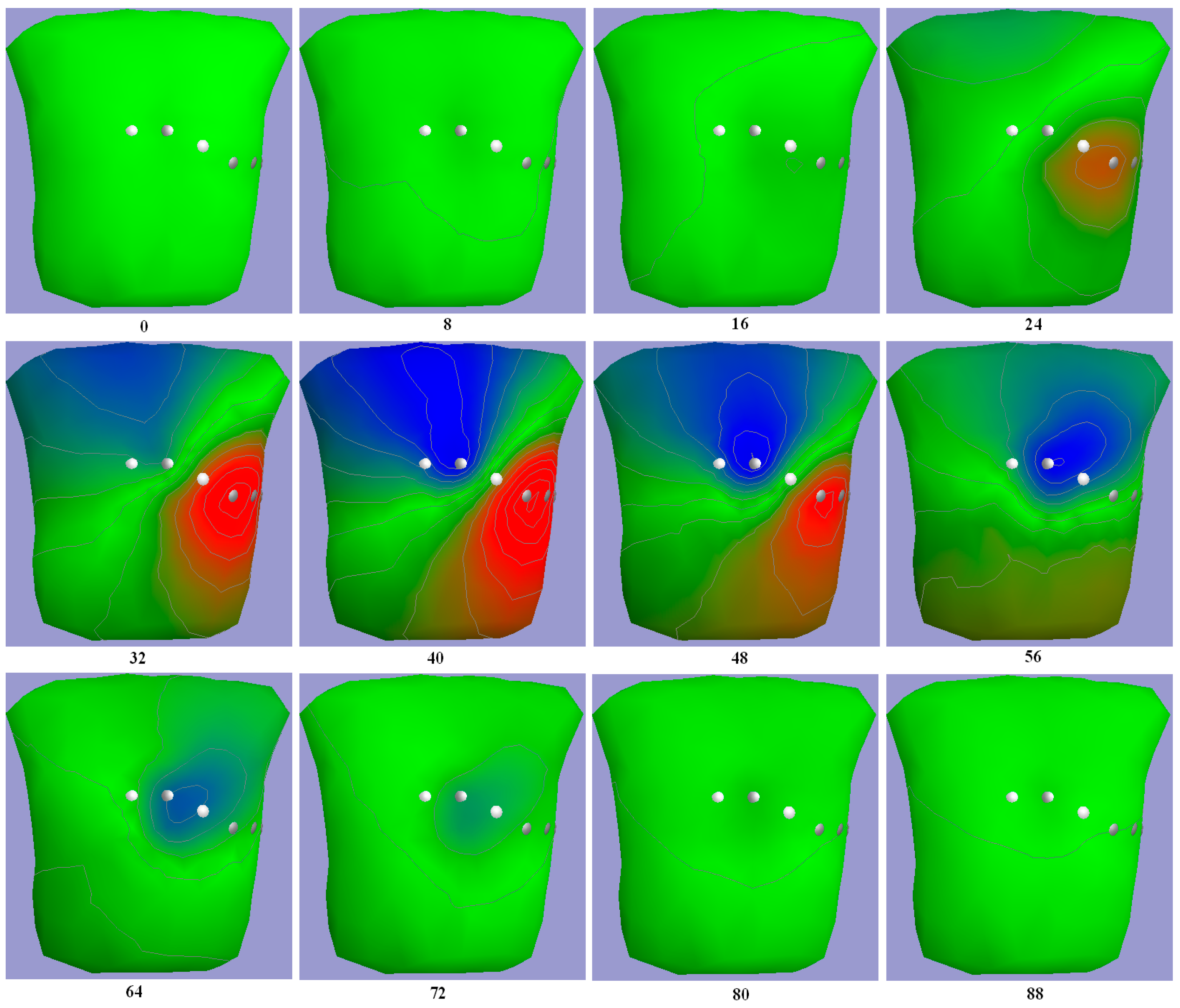

2.4. The Body Surface Potential Map (BSPM) Calculation

3. Results

3.1. Body Surface Potential Map Validation

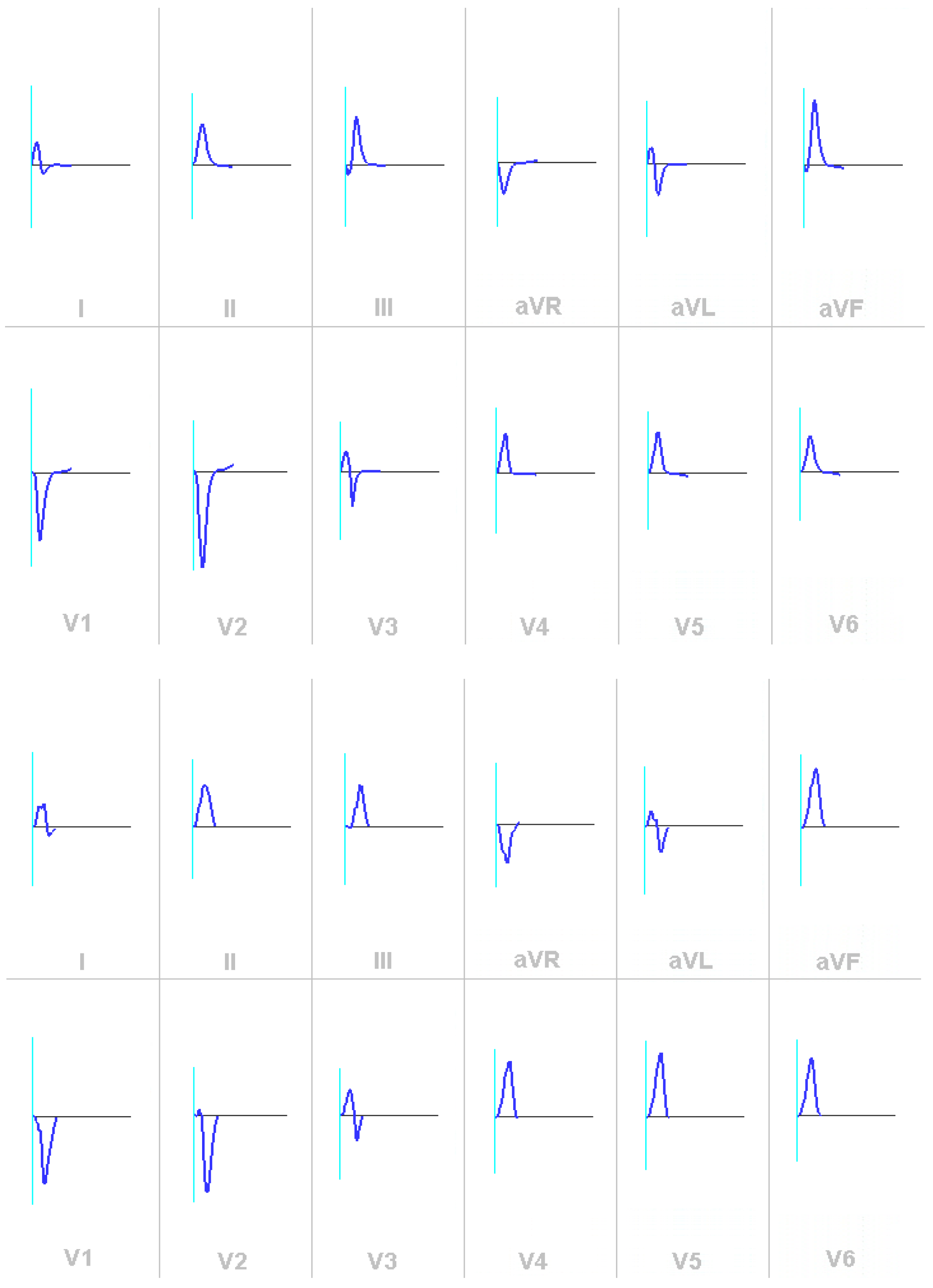

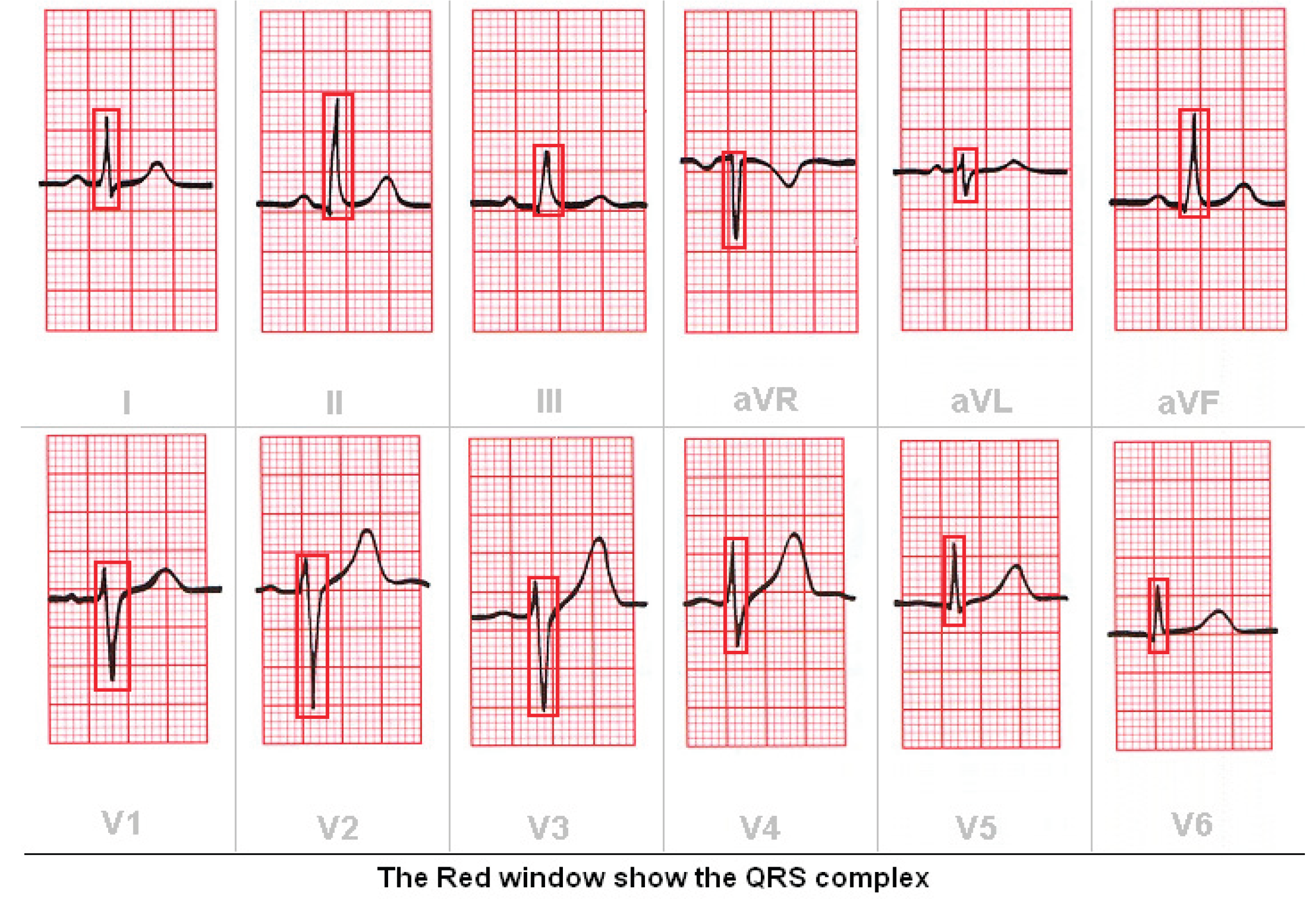

3.2. Validation of the ECG

4. Conclusion

References

- Gulrajani, R.M.; Mailloux, G.E. A simulation study of the effects of torso inhomogeneities on electrocardiographic potentials, using realistic heart and torso models. Circ. Res. 1983, 52, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmivuo, J.; Plonsey, R. Bioelectromagnetism: Principles and Applications of Bioelectric and Biomagnetic Fields, 1st Ed. ed; Oxford Univ. Press, 1995; ISBN 0195058232. [Google Scholar]

- Soundararajan, V.; Besio, W.G. Simulated Comparison of Disc and Concentric Electrode Maps During Atrial Arrhythmias. IJBEM 2005, 7, 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Simeliusa, K.; Nenonena, J.; Horácekb, M. Modeling Cardiac Ventricular Activation. Inter. J. of Bioelectromagnetism 2001, 3, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jazbinsek, V.; Hren, R.; Trontelj, Z. High resolution ECG and MCG mapping: simulation study of single and dual accessory pathways and influence of lead displacement and limited lead selection on localisation results. Bulletin of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Technical Sciences, 2005, 53, 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.W.; Zhang, H.Y.; Shi, P.C. Simultaneous Recovery of Three-dimensional Myocardial Conductivity and Electrophysiological Dynamics: A Nonlinear System Approach. Computers in Cardiology 2006, 33, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, D.S.; Skipa, O.; Kaltwasser, C.; Dossel, O.; Bauer, W.R. Personalized Model of Cardiac Electrophysiology of a Patient. IJBEM 2005, 7, 303–306. [Google Scholar]

- Seger, M. Modeling the Electrical Function of the Human Heart. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Biomedical Engineering, University for Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology.

- Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; He, B. Noninvasive reconstruction of three-dimensional ventricular activation sequence from the inverse solution of distributed equivalent current density. IEEE Trans. Med Imaging 2006, 25, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Liu, C. Three-Dimensional Cardiac Electrical Imaging From Intracavity Recordings. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2007, 54, 1454–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, A.E.; Barr, R.C. The Construction of an Anatomically Based Model of the Human Ventricular Conduction System. IEEE Trans. Biom. Eng. 1990, 37, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollan, D.F. Reconstructing The Heart: Development and Application of Biophysically Based Electrical Models of Propagation in Ventricular Myocardium Reconstructed from DTMRI. Ph.D. Thesis, Johns Hopkins University, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bernus, O.G. Development of a realistic computer model of the human ventricles for the study of reentrant arrhythmias. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gent, Belgium, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Simeliusa, K.; Nenonena, J.; Horácekb, M. Modeling Cardiac Ventricular Activation. Inter. J. of Bioelectromagnetism 2001, 3, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Berenfeld, O.; Jalife, J. Purkinje-Muscle Reentry as a Mechanism of Polymorphic Ventricular, Arrhythmias in a 3-Dimensional Model of the Ventricles. Circ. Res. 1998, 82, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farina, D.S.; Skipa, O.; Kaltwasser, C.; Dossel, O.; Bauer, W.R. Personalized Model of Cardiac Electrophysiology of a Patient. IJBEM 2005, 7, 303–306. [Google Scholar]

- Winslow, R.L.; Scollan, D.F.; Greenstein, J.L.; Yung, C.K.; Baumgartner, W.; Bhanot, G.; Gresh, D.L.; Rogowitz, B.E. Mapping, modeling,and visual exploration of structure-function relationships in the heart. IBM Sys J. 2001, 40, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaill, B.H.; LeGrice, I.J.; Hooks, D.A.; Pullan, A.J.; Caldwell, B.J.; Hunter, P.J. Cardiac structure and electrical activation: Models and measurement. Proc. of the Australian Physiological and Pharmacological Society 2004, 34, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisley, S.B.; Trayanova, N.; Aguel, F. Roles of Electric Field and Fibre Structure in Cardiac Electric Stimulation. Biophysical Journal 1999, 77, 1404–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, T.; Fischer, G.; Pfeifer, B.; Modre, R.; Hanser, F.; Trieb, T.; Roithinger, F.X.; Stuehlinger, M.; Pachinger, O.; Tilg, B.; et al. Single-Beat Noninvasive Imaging of Cardiac Electrophysiology of Ventricular Pre-Excitation. Circ. 2006, 48, 2045–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELAFF. Modeling of 3D Inhomogeneous Human Body from Medical Images. World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences 2025, 15, 2010–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. Modeling of the human heart in 3D using DTI images. World J. Adv. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2025, 15, 2450–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAI El-Aff. Extraction of human heart conduction network from diffusion tensor MRI. The 7th IASTED International Conference on Biomedical Engineering, 217–222.

- Elaff, I. Modeling the human heart conduction network in 3D using DTI Images. World J. Adv. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2025, 15, 2565–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELAFF. Modeling of realistic heart electrical excitation based on DTI scans and modified reaction diffusion equation. Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences 2018, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. Modeling of the excitation propagation of the human heart. World J. Biol. Pharm. Heal. Sci. 2025, 22, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaff, I. Effect of the material properties on modeling of the excitation propagation of the human heart. World J. Biol. Pharm. Heal. Sci. 2025, 22, 088–094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELAFF. Modeling of the Body Surface Potential Map for Anisotropic Human Heart Activation. Research Square, 2025.

- ECGSIM [online] https://www.ecgsim.org/.

- Hampton, J.R. The ECG made easy, 5th Ed.; Pearson Prof., 1997.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).