1. Introduction

Electroencephalography (EEG) has long provided crucial insights into brain activity, relying on features such as spectral power, band-specific energy, and spatial connectivity to understand cognitive processes and behaviors [

1,

2]. While these traditional features have significantly advanced the field, they often capture only low-level, task-specific characteristics, overlooking the deeper semantic layers of meaning, intention, and context encoded in neural signals.

The extraction of universal, task-independent semantic features from EEG data remains an underexplored frontier. Existing approaches that touch upon semantic interpretations tend to be narrowly tailored to specific tasks or depend on supervised methods, limiting their generality across different contexts and subjects. Developing a universal semantic feature would not only enrich our theoretical understanding of how the brain encodes meaning but also open up practical avenues for brain-computer interfaces (BCI), brain-to-brain communication systems (B2B-C), neurodiagnostics, education, and industrial automation.

Achieving this goal is challenging due to the complexity and variability inherent in neural representations, as well as the influence of contextual factors. Yet, enabling a broader, more flexible analysis of EEG signals is necessary. To address this challenge, our research focuses on three main objectives:

Defining what constitutes a semantic feature in EEG data,

outlining criteria and expectations for a universal semantic feature, such as task independence, robustness to inter-subject variability, and meaningfulness,

and assessing the feasibility of achieving these aims using state-of-the-art, unsupervised, and self-supervised deep learning (DL) techniques.

While our endeavor is ambitious, our approach is incremental. We propose and validate a framework to progressively capture semantic content, bridging the gap between the need for semantic interpretation and the limitations of current EEG feature sets. By doing so, we aim to establish a universal semantic representation independent of specific tasks or conditions, thus facilitating a wide range of analyses, including supervised classification, unsupervised clustering, cross-subject comparisons, and within-subject investigations over time.

Ultimately, this work lays the groundwork for transforming EEG analysis from a task-centric paradigm to one capable of universal semantic interpretation. Such progress is essential for advancing neuroscience research, fostering interdisciplinary collaborations, and enhancing the capabilities of neurotechnology and neuroinformatics applications.

The organization of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 discusses related work, followed by the proposed methodology in

Section 3.

Section 4 provides the mathematical formulation, and

Section 5 presents the results.

Section 6 discusses the findings in detail, and finally,

Section 7 concludes the study with key insights and future directions.

2. Related Works

EEG signal processing has progressed substantially, yielding successful applications in diverse tasks. Ensemble learning frameworks for motor imagery (MI) classification, such as correlation-optimized weighted stacking ensembles (COWSE) and weighted and stacked adaptive integrated ensemble classifiers (WS-AIEC), have improved accuracy and robustness across multiple datasets [

3,

4]. In clinical settings, hierarchical binary classification frameworks combining convolutional neural network (CNN)-based spectrogram features with random forests (RF) and approximate entropy (ApEn) have achieved perfect coma outcome prediction from just two minutes of EEG data per subject, underscoring their efficiency and practical relevance [

5].

Efforts to improve the security and robustness of EEG-based systems have introduced frameworks that enhance the resilience of B2B-C systems against adversarial attacks through adversarial neural network training (ANNT). These approaches have optimized architectures, such as CNN-temporal convolutional networks (TCN), achieving significant improvements in accuracy and security metrics [

6,

7].

Efforts toward semantic feature extraction from EEG signals have emerged in various domains. Studies examining potency, valence, and arousal via high-density EEG and source localization have revealed distinct spatiotemporal patterns for abstract and concrete words, illustrating EEG’s ability to represent subtle semantic distinctions [

8]. Similarly, differential entropy and peak-magnitude root mean square ratio, combined with variational mode decomposition (VMD), have improved epileptic seizure classification through semantic feature extraction [

9]. Event-related potential (ERP) investigations (e.g., N400 amplitude) further highlight that semantic relevance, rather than feature type or category, influences neural responses during concept retrieval [

10].

Recent approaches integrate EEG with visual data for semantic-driven image reconstruction. An EEG-visual-residual-network (EVRNet) and diffusion models have jointly achieved high-resolution image generation [

11], while dual conditional autoencoders (DCAE) fusing multimodal semantic features with UNet-based image generation have further improved reconstruction quality [

12]. Beyond this, multimodal frameworks have combined attention mechanisms, graph convolutional networks, and bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) layers to extract spatiotemporal-frequency semantic features for enhanced emotion recognition [

13]. NeuroBCI systems facilitate multi-brain-to-multi-robot interactions, employing dynamic EEG feature extraction, semantic transmission frameworks, and edge computing for parallel multi-agent control [

14]. Further, EEG-based word processing studies have identified theta-band activity in the left anterior temporal lobe as a key node linking distributed modality-specific networks into a multimodal semantic hub [

15].

Recent work has also decoupled semantic-related and domain-specific features from EEG and visual inputs, boosting visual category decoding by maximizing mutual information and ensuring geometric consistency [

16]. A comprehensive review spanning EEG, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), magnetoencephalography (MEG), and electrocorticography (ECoG) modalities has identified the absence of a universal, task-independent semantic feature, highlighting issues like inter-subject variability and multimodal integration challenges [

17]. Similarly, object-based decision tasks have demonstrated notable classification accuracy using common spatial patterns (CSP) and RF classifiers for semantic category decoding [

18].

These studies showcase significant strides in classification, interpretation, and semantic feature extraction using advanced techniques—from ensemble learning and deep networks to multimodal fusion and signal decomposition. However, they remain constrained by task specificity and often rely on supervised paradigms. No existing methodology provides a universal, task-independent semantic feature quantifying semantic richness in EEG data, regardless of context.

This research seeks to address this limitation by proposing a framework for extracting a universal, task-independent semantic feature from EEG signals. Building on the foundational advancements outlined above, this work introduces a novel methodology to advance EEG signal processing and semantic analysis, addressing task specificity and generalizability challenges.

3. Methodology

Extracting a universal, task-independent semantic feature from EEG signals requires a clear conceptual foundation. In this section, we define the notion of a semantic feature in EEG data, establish the criteria such a feature must satisfy, and introduce our proposed computational framework designed to achieve these objectives.

A semantic feature for EEG data encapsulates the high-level, contextually meaningful information encoded in neural activity, moving beyond the low-level, task-specific attributes (e.g., spectral power, temporal metrics) typically extracted. Rather than focusing narrowly on a particular frequency band or experimental condition, semantic features aim to capture the deeper cognitive or conceptual content processed by the brain, regardless of the external task or stimulus.

To qualify as a universal semantic feature, the representation must satisfy the following requirements:

Task Independence: Remain applicable across varying tasks, stimuli, and conditions without relying on task-specific labels or supervised models.

Robustness to Inter-Subject Variability: Consistently represent semantic content across individuals, accommodating anatomical and functional differences.

Scalability and Generalizability: Scale effectively to large datasets and generalize to new, unseen data with minimal performance degradation.

Interpretability: Convey meaningful information that aids in understanding underlying neural processes.

Compatibility with Downstream Analyses: Support a wide range of downstream tasks, including both supervised (e.g., classification) and unsupervised (e.g., clustering) analyses.

Modern DL and unsupervised learning techniques provide promising avenues for extracting such universal features. Unlike traditional machine learning (ML) approaches that rely on labeled datasets and are confined to specific tasks, unsupervised and self-supervised DL methods learn hierarchical representations directly from raw data, naturally aligning with our goal of task independence.

We, therefore, propose a novel computational framework that integrates three key DL components:

CNNs: Capture local spatial and temporal dependencies within multichannel EEG signals.

Autoencoders: Reduce dimensionality and filter noise by learning compressed latent representations, retaining only the most salient EEG features.

Transformers: Exploit self-attention mechanisms to model long-range temporal relationships and global context, extracting high-level semantic patterns independent of task conditions.

3.1. Model Architecture

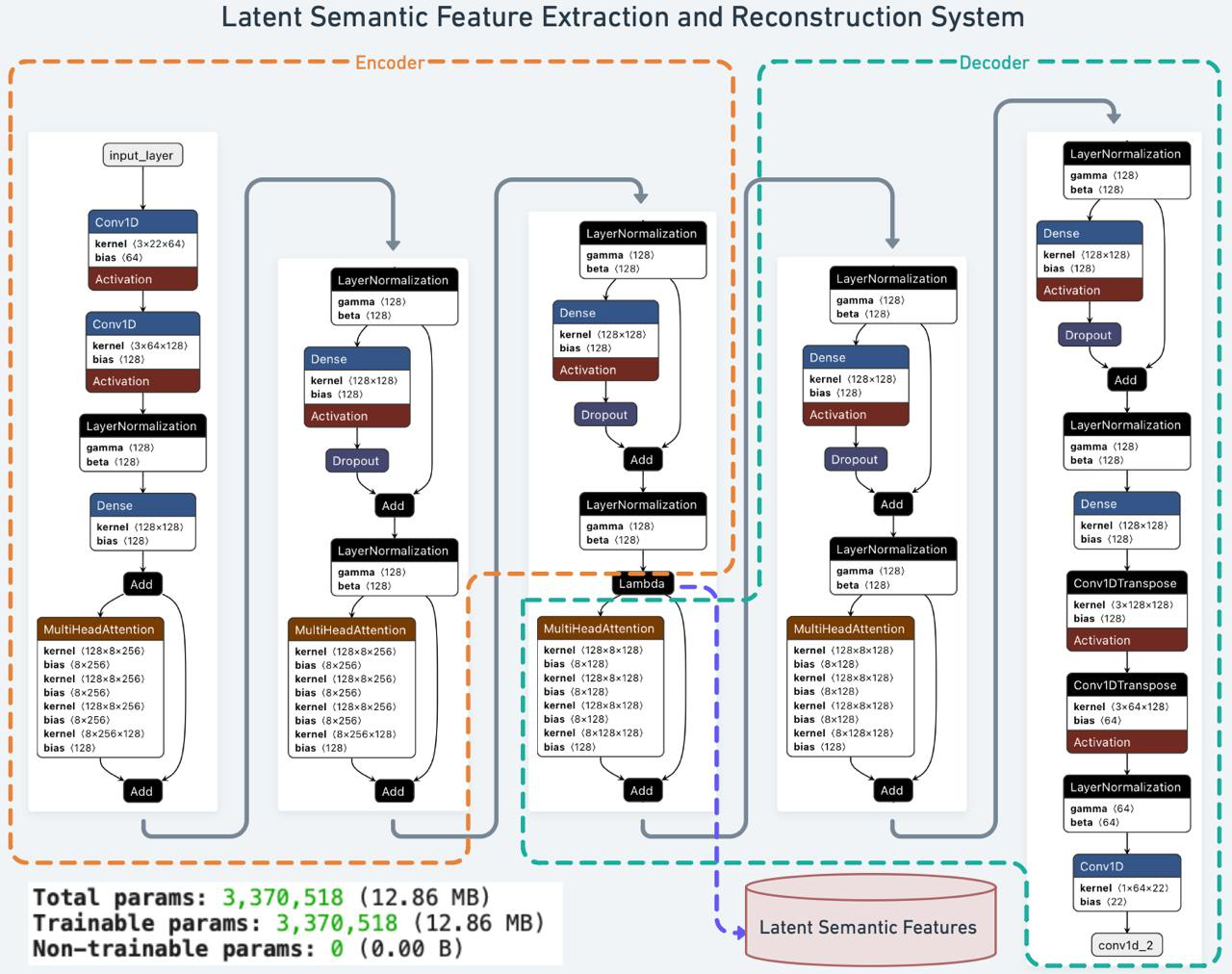

Our proposed architecture (

Figure 1) comprises an encoder, a bridging layer producing latent semantic features, and a decoder reconstructing the original signals.

The encoder (orange section) processes raw, preprocessed EEG segments. Two 1D CNN layers capture and refine local spatial-temporal patterns, followed by layer normalization to stabilize training. A dense projection layer then maps these extracted patterns into a suitable dimensionality, while a multi-head self-attention mechanism captures global dependencies and contextual relationships. This sequence of operations transforms the input EEG into a high-dimensional latent representation that abstracts away task-specific details.

A bridging Lambda layer converts the encoder’s high-dimensional output into task-independent latent semantic features. These features encapsulate high-level meanings and contextual information beyond low-level EEG attributes. They reduce noise, handle inter-subject variability, and produce interpretable patterns for various downstream analyses.

Finally, the decoder (green section) reconstructs the original EEG signals from these latent semantic features. A series of dense layers and normalization steps ensure stable and coherent feature distributions, while convolutional transpose layers invert the encoding process to restore the spatial-temporal structure of the input. The output layer produces the reconstructed EEG signals, enabling direct evaluation of how effectively the extracted semantic features represent the original data.

3.2. Datasets

To validate the effectiveness of our model, we utilized a diverse collection of publicly available EEG datasets encompassing MI, Steady-State Visually Evoked Potentials (SSVEP), and ERP, specifically P300 datasets. The details of these datasets are provided in

Table 1,

Table 2, and

Table 3.

3.3. Training Procedure

Our training procedure relies on unsupervised learning to derive task-independent EEG representations. The parameters and steps described here focus on the BCICIV_2a dataset but can be adapted for other EEG datasets as needed. Data preparation begins by segmenting EEG recordings into 1-second windows (250 samples at 250 Hz) with 50% overlap. After applying a zero-phase FIR band-pass filter (6–32 Hz, Hamming window) to isolate MI-relevant frequencies, we use a 50 Hz notch filter (also zero-phase FIR) to remove power line noise without phase distortion. Each channel is then standardized to zero mean and unit variance, and Gaussian noise is added to enhance robustness and generalization.

The model configuration includes two 1D CNN layers (64 and 128 filters, kernel size 3, ReLU activations) to capture local temporal-spatial patterns, followed by a Transformer module with an embedding size of 128, four layers, eight attention heads, and a 128-dimensional position-wise feed-forward network to model long-range dependencies. A symmetrical decoder, including Conv1DTranspose layers, reconstructs the original EEG signals from the latent features.

We train the model by minimizing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss, using Adam with a learning rate of , a batch size of 64, and up to 100 epochs. Regularization techniques such as EarlyStopping (patience=5) ensure training halts when validation loss stops improving, and ReduceLROnPlateau (factor=0.5, patience=3) reduces the learning rate if progress stagnates. A 90:10 train-validation split monitors generalization and informs hyperparameter tuning. Parameters like filter bands, Transformer depth, or training epochs can be adjusted for other EEG datasets (e.g., SSVEP or ERP) with different sampling rates, trial lengths, or complexities.

3.4. Evaluation and Analysis

We evaluated the extracted semantic features across multiple EEG paradigms, including MI, SSVEP, and ERP (P300), using both supervised classification tasks and additional exploratory analyses. For MI and SSVEP datasets, classification accuracy served as the primary metric, while ERP datasets employed the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) to address class imbalance. We used Leave-One-Subject-Out (LOSO) cross-validation for MI datasets and 10-fold cross-validation for SSVEP and ERP datasets to ensure robust estimates. A 2D CNN classifier was applied to map the semantic features to class labels, choosing architectures and hyperparameters that balanced complexity and generalization.

Beyond classification, we performed complementary analyses on the BCICIV_2a dataset to gain deeper insights into the structure and stability of the semantic features. Clustering and dimensionality reduction techniques were employed to determine whether these features inherently form meaningful groups, while correlation analysis helped identify and remove feature redundancies. Additionally, ablation studies examined the effect of modifying Transformer complexity (e.g., number of layers, attention heads) on the quality and fidelity of the extracted features.

4. Mathematical Formulation

We consider a dataset of EEG signals recorded from multiple subjects and aim to extract universal, task-independent semantic features from these signals. Our objectives are to design an unsupervised Autoencoder that captures latent representations of EEG data beyond traditional features, incorporate CNNs to model local spatial-temporal patterns, utilize Transformers with self-attention to capture global context, and ultimately produce subject-level semantic feature vectors for downstream analyses. While the following formulation is tailored to the BCICIV_2a MI dataset (with parameters such as , , and ), these choices can be adapted to other datasets as needed.

Let represent the set of subjects, and for each subject , EEG recordings are divided into segments. These segments are denoted as , where each contains T time steps per segment and C channels. We define as the encoder, and as the decoder, where represents the dimension of the latent semantic feature space, and is the output time resolution after encoding. With same-padding convolutions and consistent dimensionality, we have .

The model is an Autoencoder integrating CNN and Transformer modules. The encoder

transforms raw EEG segments into latent semantic features, while the decoder

reconstructs the original signals. In the encoder, we first reshape

to

and apply two 1D CNN layers along the temporal dimension:

where

and

are 1D CNNs with 64 and 128 filters, kernel size 3, and same-padding. After transposing

back to

, layer normalization yields:

Next, we project

into

using a Dense layer and then add positional encodings

to incorporate temporal order information. Letting

, we define:

where

is the embedded representation enriched with positional information.

We then apply

Transformer encoder layers, each with 8 heads. For layer

l, multi-head self-attention (MHA) is:

where

, and the same input

is used as the query, key, and value, to capture contextual relationships within the same sequence. It is followed by Add & Layer Normalization:

and a position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN):

with another Add & LayerNorm step:

where

are learnable parameters. After four layers, the encoder output is the latent representation of the input EEG segment:

The decoder

mirrors the encoder. We apply a Transformer decoder (also 4 layers, 8 heads, self-attention only) to

, producing

. A Dense layer maps it to 128 features:

Two Conv1DTranspose layers reconstruct the original temporal and channel dimensions:

and layer normalization is applied:

A final linear layer outputs:

where

is the reconstructed EEG segment.

We train the model by minimizing the MSE between the original and reconstructed EEG segments:

where

N is the total number of segments and

represents all trainable parameters.

After training, we extract semantic features as follows. For each segment

, the encoder produces:

Temporal averaging yields a fixed-size feature vector for each segment:

Averaging over all segments of subject

s gives a subject-level semantic feature vector:

Normalizing

to unit norm produces:

The resulting is the subject-level semantic feature vector, representing universal, task-independent information.

5. Results

This section presents the outcomes of our universal, task-independent semantic feature extraction framework across multiple EEG paradigms—MI, SSVEP, and ERP (P300)—summarized in

Table 1,

Table 2, and

Table 3. While the model was trained and evaluated on all datasets, we focus graphical and illustrative results on the BCICIV_2a MI dataset for brevity, as similar patterns were observed elsewhere. Our method is implemented with PyTorch 2.0+ in Python 3.11 using an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 with CUDA 12.0.

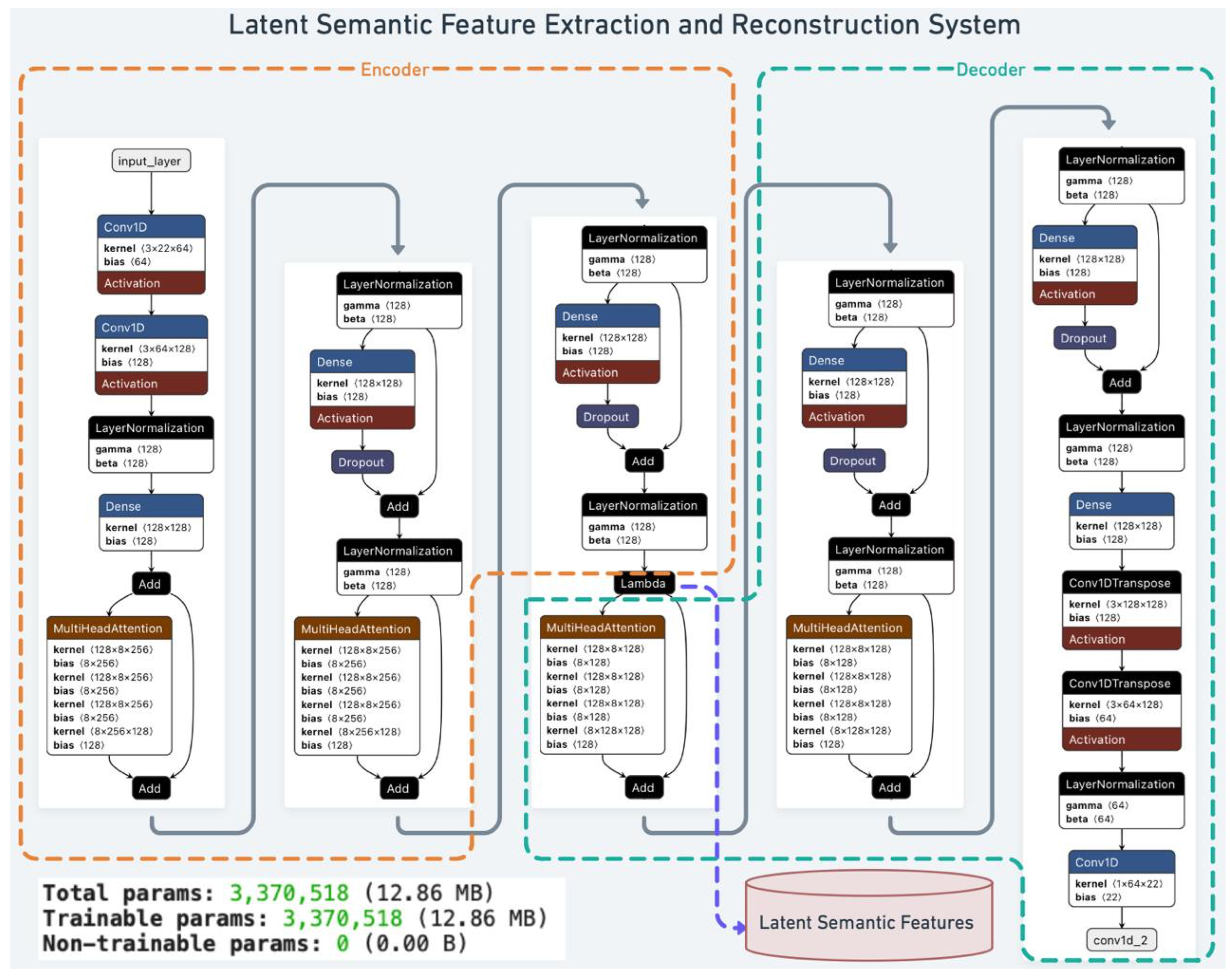

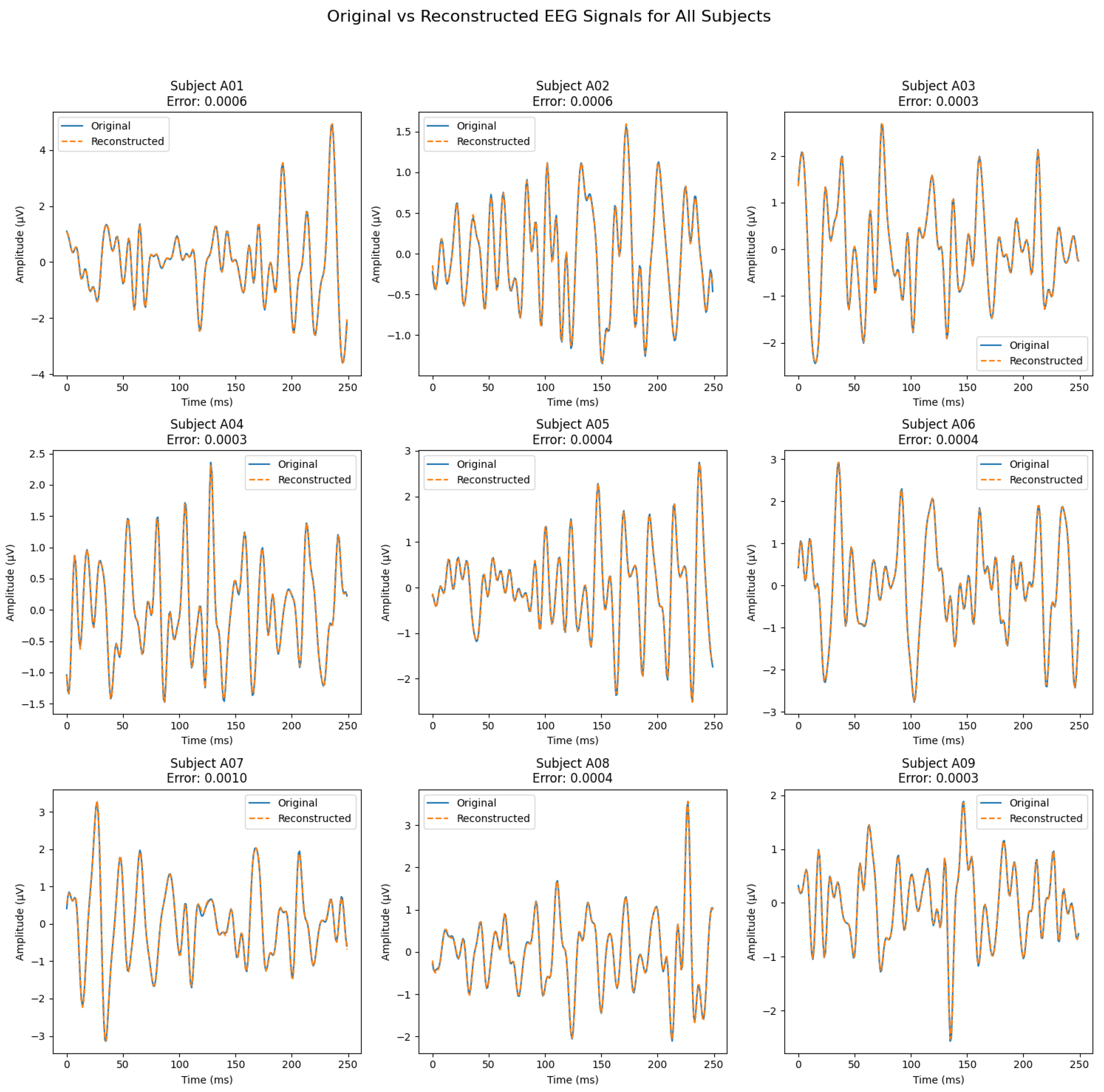

We first examine the model’s convergence behavior on BCICIV_2a.

Figure 2 shows that both training and validation losses steadily decrease, indicating effective learning and generalization—trends consistent across other datasets.

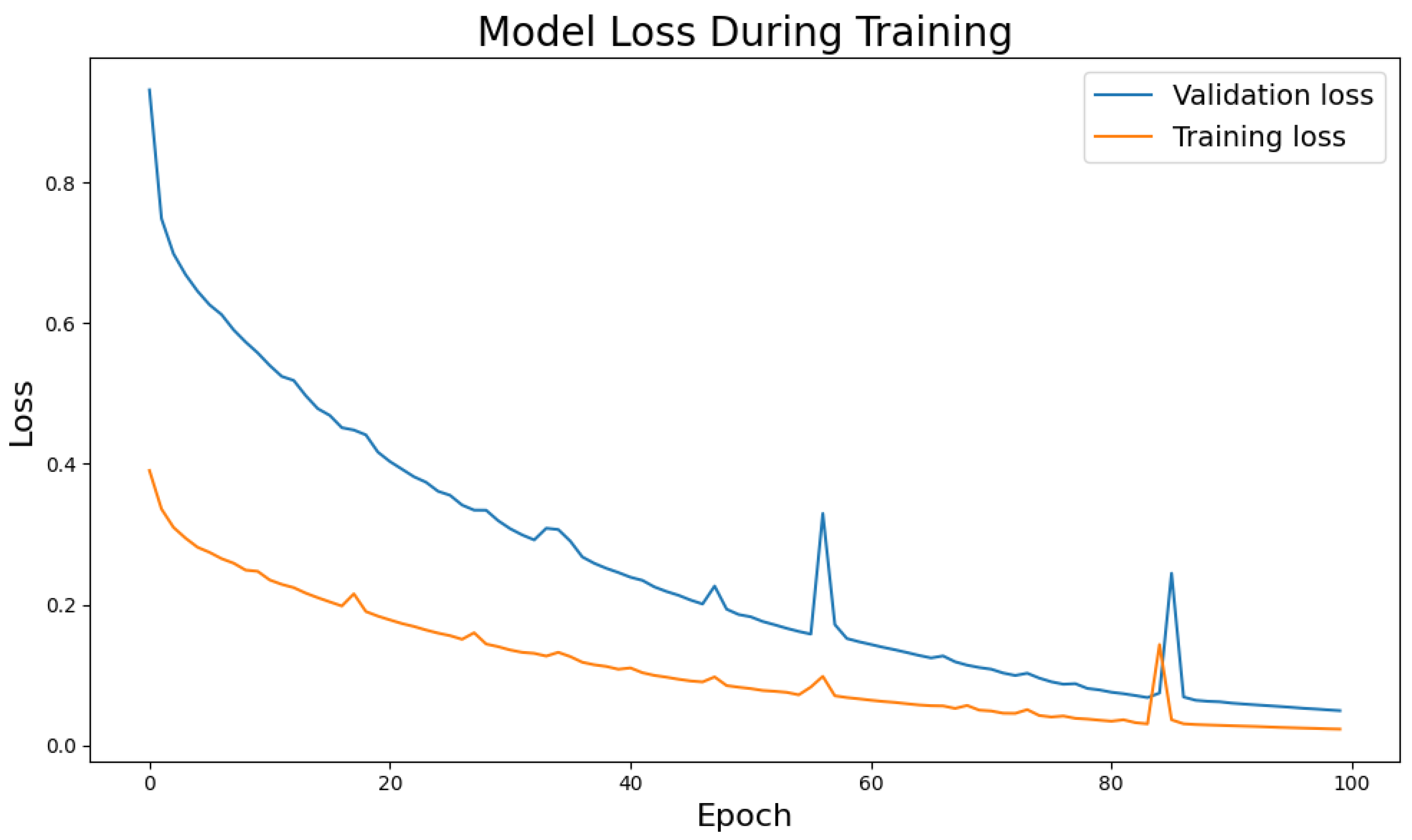

Next, we verify reconstruction quality.

Figure 3 compares original and reconstructed EEG signals, confirming that the latent semantic features preserve essential signal characteristics.

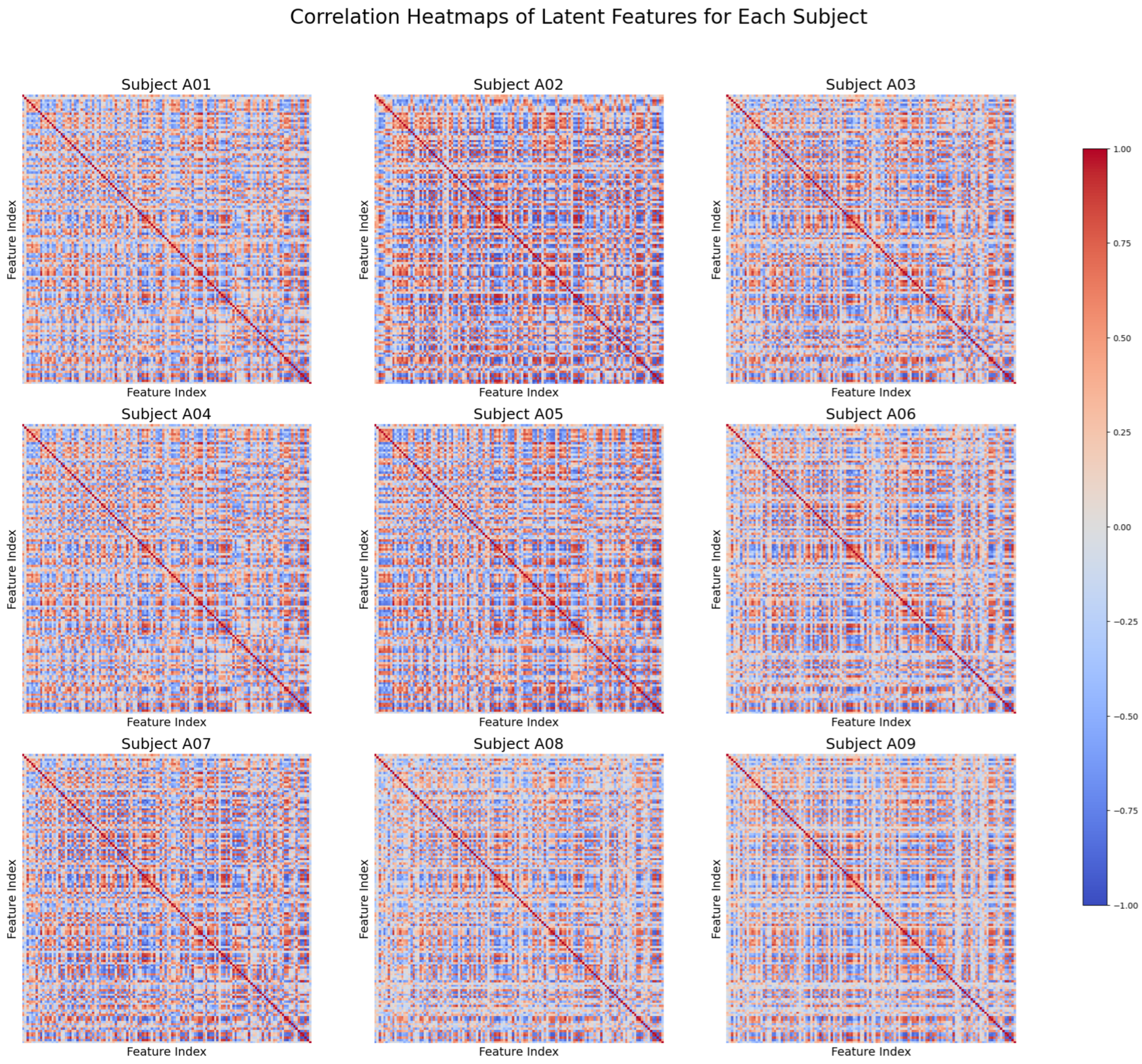

To further evaluate the extracted latent semantic features, we conducted a detailed correlation analysis for each subject. The correlation heatmaps, as shown in

Figure 4, reveal subject-specific structural patterns and provide insights into the consistency and diversity of the extracted features across individuals. These patterns underscore the model’s ability to balance universal feature representation with subject-specific nuances, paving the way for robust and adaptable downstream analyses.

Finally, we evaluated the semantic features in supervised classification tasks for MI, SSVEP, and ERP datasets. Although detailed comparisons with state-of-the-art methods are discussed later,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6, and

Table 7 show that our approach performs favorably. Accuracy is reported for MI and SSVEP (balanced classes) and AUC for ERP (P300) datasets (class imbalance). Subsequent sections provide interpretations and in-depth discussions of these findings. The acronyms (e.g., FBCSP, EEGNet) used in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6, and

Table 7 refer to models as originally presented in their respective studies, with details available in the cited references.

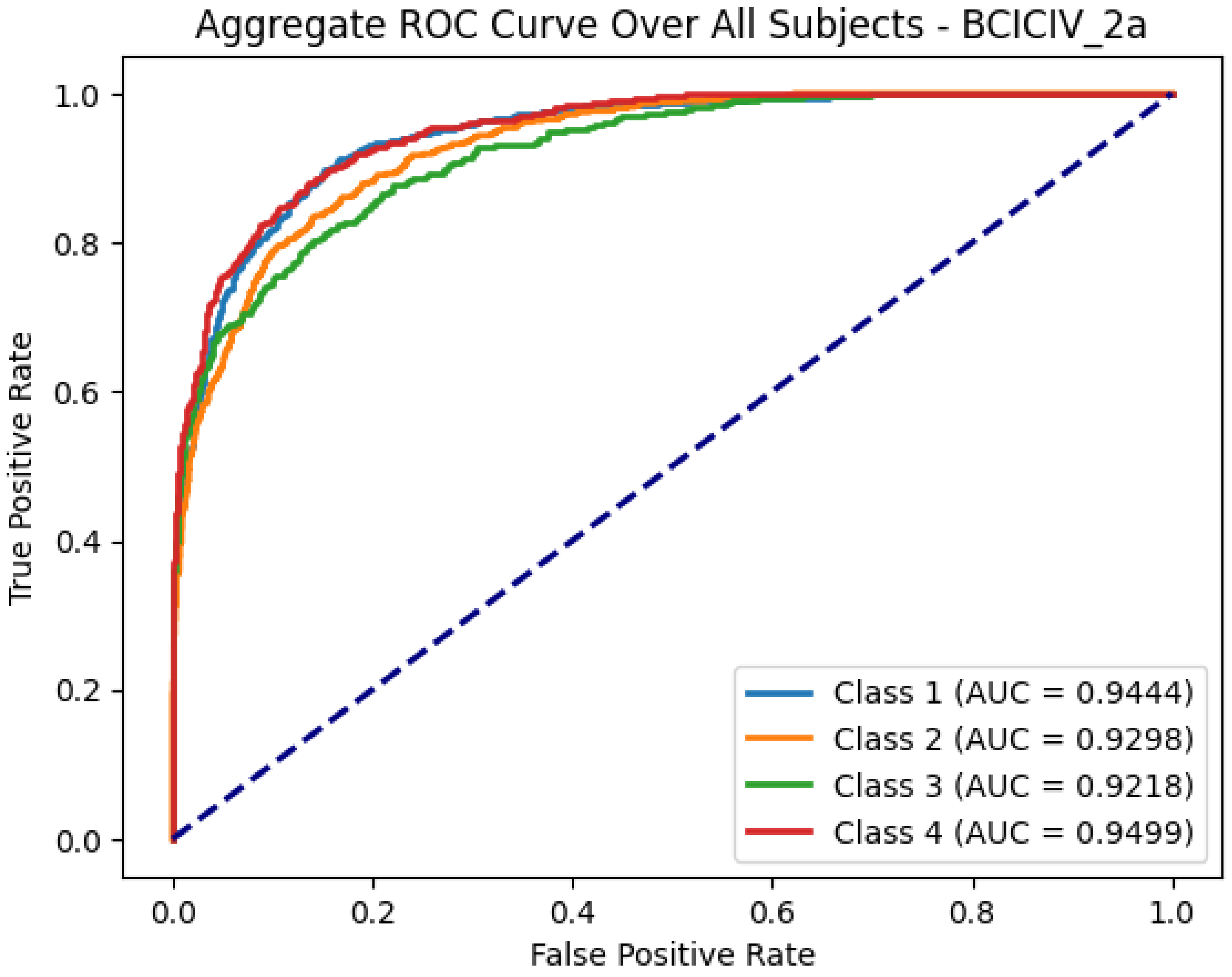

To comprehensively evaluate the classification performance on the BCICIV_2a dataset, we analyzed the ROC curves for each subject and aggregated the results to highlight overall performance trends. For brevity,

Figure 5 presents the aggregate ROC curve over all subjects, summarizing the discriminative capability of the model across the four MI classes, with high AUC values indicating robust classification performance.

6. Discussion

This section delves into the detailed interpretation of our findings, contextualizing the results presented earlier and exploring their implications for EEG-based semantic feature extraction.

6.1. Convergence Behavior and Generalization

Training and validation curves (

Figure 2) from the BCICIV_2a dataset illustrate the model’s stable learning dynamics and strong generalization capabilities. The training loss declines steadily, indicating effective learning of underlying EEG patterns, while the validation loss decreases at a similar pace, reflecting robust generalization. Minor fluctuations in validation loss likely stem from natural EEG variability, yet the model’s quick recovery demonstrates resilience. Similar convergence trends observed across other datasets confirm that the framework consistently learns task-independent semantic features, producing smoothly converging learning curves and minimal overfitting.

6.2. Reconstruction Performance

Reconstruction quality (

Figure 3) highlights the fidelity and utility of the latent semantic features. Across all subjects, reconstructed EEG signals closely mirror the originals, with minimal reconstruction errors (0.0006–0.001) indicating efficient encoding and decoding. Key temporal and amplitude characteristics remain intact, preserving essential neural patterns for downstream applications. Consistent reconstruction quality across subjects underscores the framework’s adaptability to inter-subject variability. High fidelity suggests that the latent features capture core information suitable for classification, clustering, and other analyses, thereby validating the effectiveness of the autoencoder-based extraction process in retaining meaningful patterns while minimizing noise.

6.3. Semantic Feature Correlation Analysis

Examining correlations among extracted semantic features (

Figure 4) reveals insights into their structure and diversity. Each participant exhibits a unique correlation matrix reflecting individual neural dynamics. High positive correlations indicate feature pairs that capture similar neural processes and reinforce the idea of task-independent representation, while each subject’s distinct pattern demonstrates adaptability to anatomical and functional differences. A mix of positive and negative correlations suggests both complementary and overlapping features, indicating that reducing redundancy and increasing diversity could enhance feature quality. These observations confirm that the framework extracts a balance of universal and subject-specific semantic features, resulting in robust, meaningful representations for various EEG-related tasks and applications.

6.4. Supervised Classification Performance and Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

We assessed the classification performance of our extracted semantic features across MI, SSVEP, and ERP (P300) datasets, comparing results against state-of-the-art approaches (

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6, and

Table 7). For MI datasets (BCICIV_2a and BCICIV_2b), our framework achieved top accuracies of 83.50% and 84.84%, respectively, outperforming leading approaches such as Conformer [

42], FBCNet [

40], DRDA [

41], and demonstrating robustness and adaptability to subject variability. On SSVEP datasets (Lee2019-SSVEP and Nakanishi2015), we recorded accuracies of 98.41% and 99.66%, surpassing TRCA [

48] (previous best) and confirming our model’s suitability for steady-state stimulus decoding. For ERP (P300) datasets, we attained the highest average AUC (91.80%) across eight datasets, exceeding results from [

51] and [

50], and setting new performance benchmarks in handling class-imbalanced conditions. Collectively, these results attest to the generality and resilience of our semantic feature extraction, capturing meaningful neural patterns that apply to diverse tasks. They highlight the approach’s scalability, versatility, and potential real-world utility, while establishing a new benchmark for EEG-based classification and advancing both theoretical and practical aspects of EEG analysis.

In addition to achieving high accuracy and AUC values, the ROC analysis provides deeper insights into the discriminative power of the extracted semantic features. The aggregate ROC curve for the BCICIV_2a MI dataset, presented in

Figure 5, consolidates the class-wise performance across all subjects, yielding high AUC values for all four classes (ranging from 0.9218 to 0.9499). These results emphasize the model’s robust ability to distinguish between different classes effectively, further reinforcing its generalization and adaptability in diverse classification scenarios.

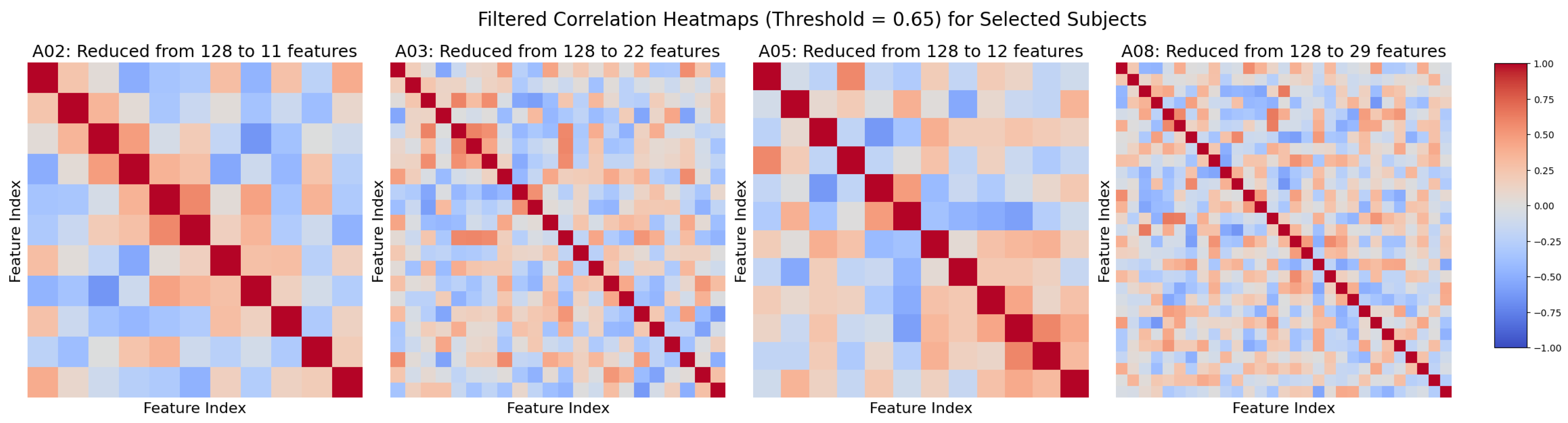

6.5. Correlation Between Subject Performance and Semantic Feature Characteristics

We examined whether subject-level classification performance correlates with the diversity and quality of extracted semantic features. As shown in

Figure 6, after applying a correlation threshold of 0.65 to reduce redundancy, subjects with lower accuracy (e.g., Subjects 2 and 5) retained fewer features (11 and 12, respectively), whereas high-performing subjects (e.g., Subjects 3 and 8) preserved substantially more (22 and 29). This suggests that better-performing subjects have more distinct and informative feature sets, while weaker performance may indicate redundancy or noise within the features.

To validate the significance of the retained features, we performed an ANOVA test on the 22 filtered features from Subject A03. Each feature was examined to determine whether its values differed significantly among the class labels (the factors in the analysis).

Table 8 shows that all 22 features were statistically significant (

), confirming that these filtered features are meaningful for distinguishing between classes for Subject A03.

These findings illustrate that selectively retaining the most meaningful semantic features can enhance classification accuracy and offer more interpretable neural patterns. By highlighting subject-specific feature quality and diversity, our framework enables targeted optimization and more nuanced applications, such as personalized feedback or adaptive EEG-based interfaces.

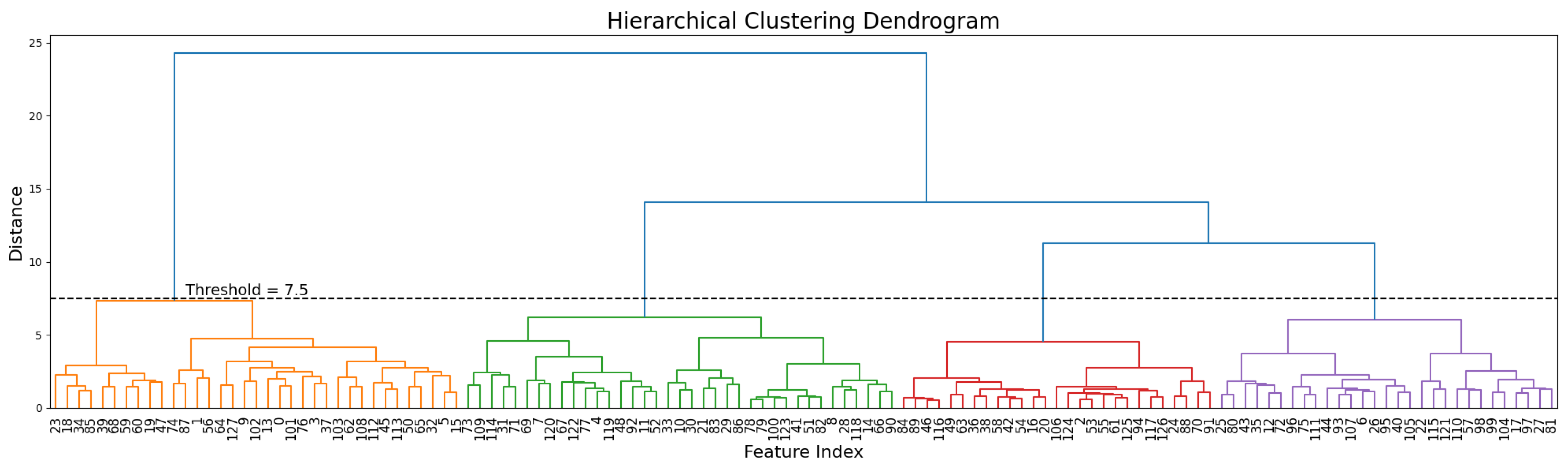

6.6. Clustering Analysis of Extracted Semantic Features

We examined the unsupervised clustering properties of the extracted semantic features using the BCICIV_2a dataset to evaluate their ability to naturally reflect task structure. Hierarchical clustering (

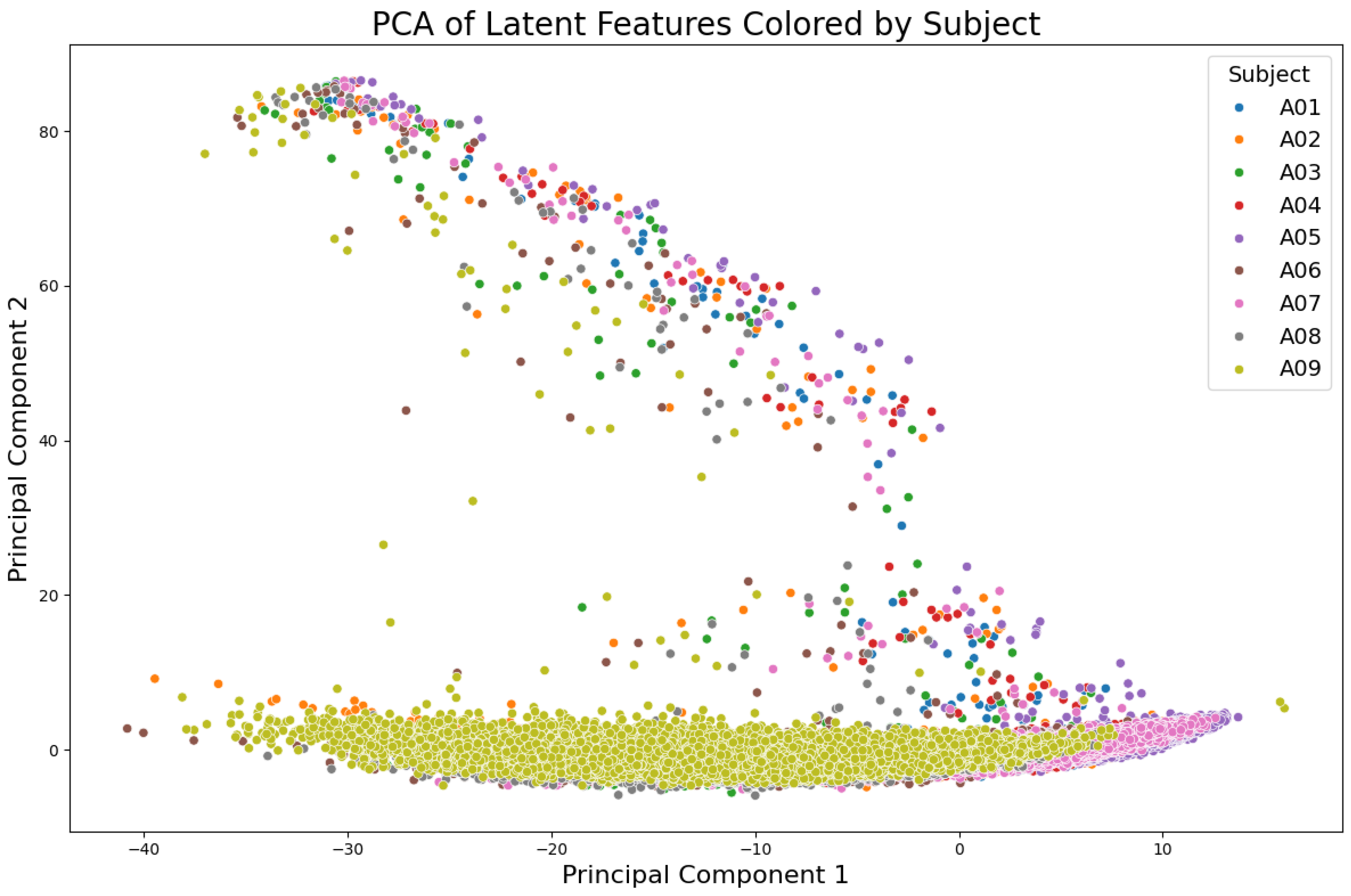

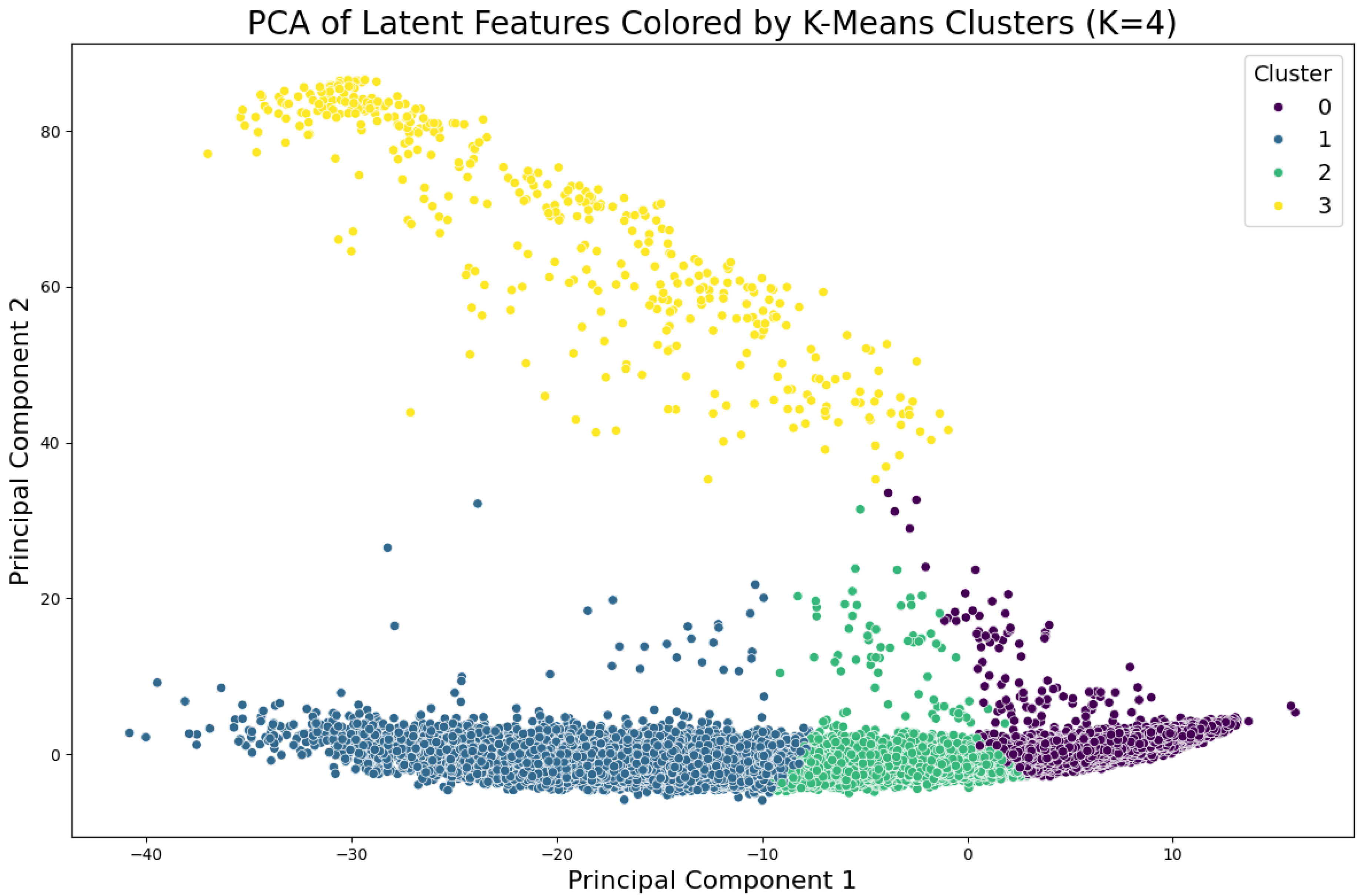

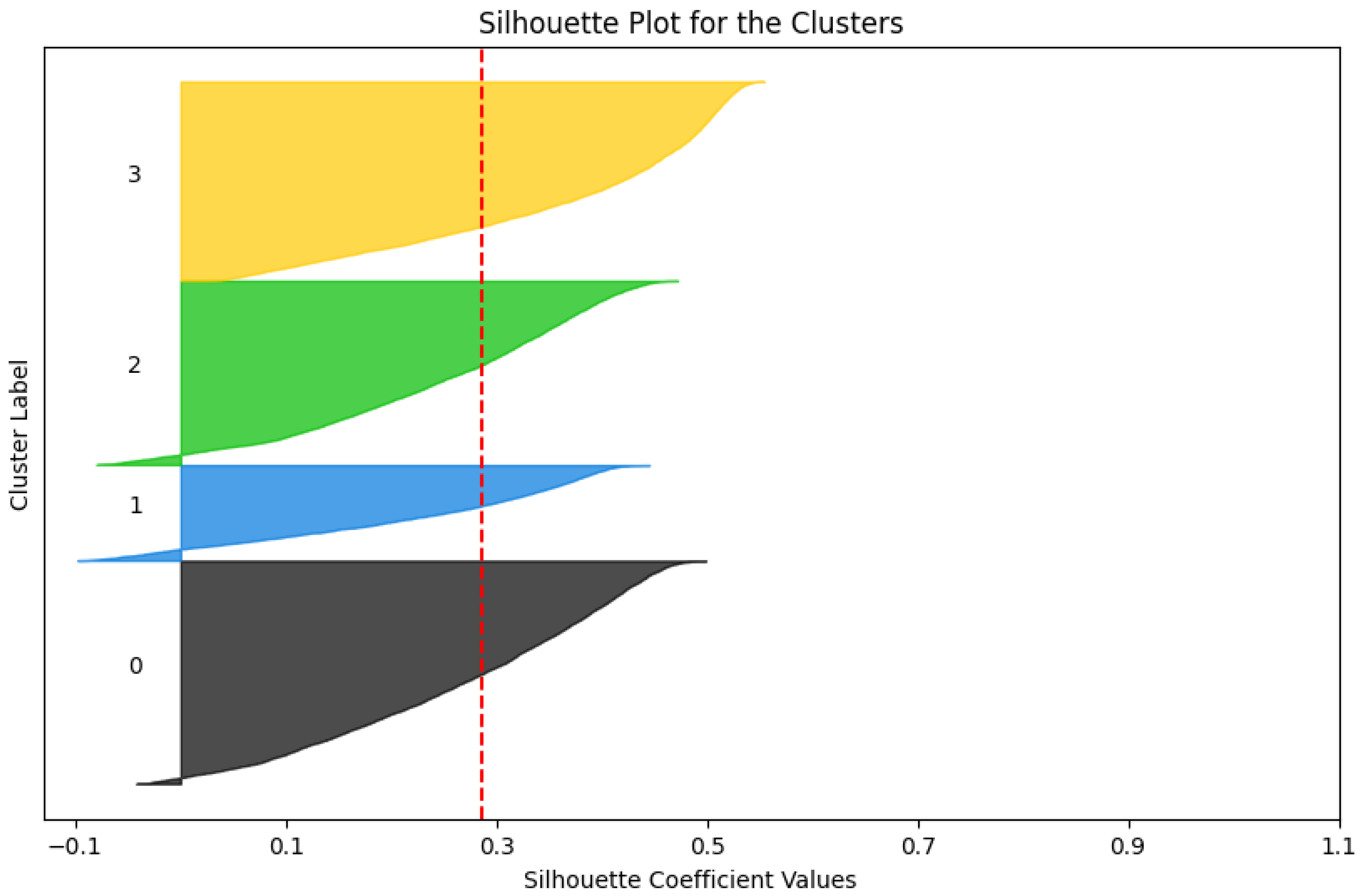

Figure 7) revealed distinct groupings with four well-defined clusters corresponding to the four MI classes. These clusters emerged below a chosen distance threshold, demonstrating the features’ ability to encode class-specific patterns without supervision. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was also applied to visualize the latent semantic features.

Figure 8 illustrates the PCA projection colored by subjects, highlighting inter-subject variability while preserving overall structure. When PCA projections were grouped using K-means clustering (k=4), as shown in

Figure 9, the clusters aligned naturally with the underlying MI classes, reinforcing the semantic features’ task-relevant organization. Further validating the clustering quality, silhouette analysis (

Figure 10) demonstrated strong cluster cohesion and separation, indicating that the semantic features inherently form well-organized latent spaces. This inherent organization supports downstream tasks like classification and anomaly detection by providing a task-relevant latent space. These results demonstrate the extracted features’ robustness and potential for real-world applications.

6.7. Ablation Analysis

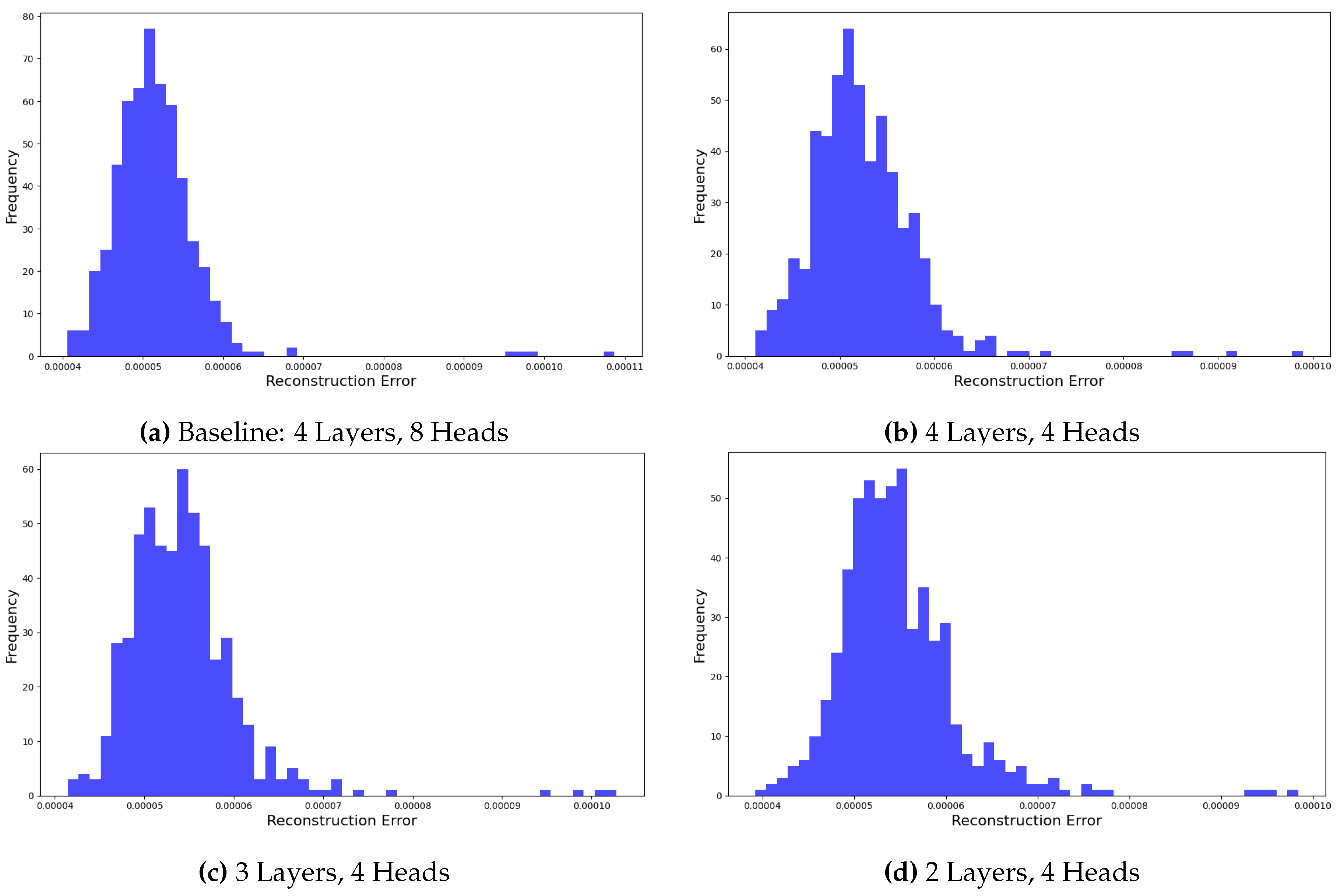

To validate our baseline Transformer configuration (four layers, eight heads), we examined how varying the number of layers and attention heads affected reconstruction quality.

Figure 11 show reconstruction error distributions for several configurations. Reducing attention heads from eight to four led to increased error variance, indicating that fewer heads limit the model’s ability to capture diverse feature dependencies. Similarly, decreasing the layer count (from four to three or two) further broadened the error distribution, underscoring the importance of network depth in modeling hierarchical representations. These findings confirm that our chosen configuration balances complexity and performance, as any deviation consistently reduces reconstruction fidelity.

6.8. Limitations and Future Directions

Although the proposed methodology demonstrates strong performance, several limitations must be acknowledged. Model complexity and high computational costs pose challenges for real-time or resource-constrained applications. The data-hungry nature of Transformers presents difficulties when dealing with typically small EEG datasets, raising the risk of overfitting and limited generalization. While data augmentation can address data scarcity, excessive augmentation risks diluting meaningful patterns. Furthermore, training deep models on constrained EEG datasets can lead to optimization issues, and the neurophysiological interpretation of the extracted semantic features remains unclear.

To overcome these constraints and advance the methodology, future work should focus on optimizing model configurations, such as determining the minimal number of layers or attention heads needed to maintain high accuracy while reducing complexity. EEG-specific data augmentation strategies can improve robustness without introducing noise or redundancy. Transfer learning from larger EEG corpora may enhance performance on smaller, domain-specific datasets. Additionally, neurophysiological validations are needed to establish clear links between the extracted features and underlying brain processes, improving interpretability and practical relevance. Efforts to streamline computational efficiency—through lighter architectures, pruning, or quantization—could make the approach more accessible. Finally, a theoretical framework is needed to better understand the semantic features’ role and utility while systematically balancing model complexity, data size, and computational overhead will ensure that solutions remain both practical and high-performing.

7. Conclusion

We presented a universal, task-independent framework for extracting semantic features from EEG signals, bridging the gap between conventional feature extraction and task-specific methods. By integrating CNNs, Autoencoders, and Transformers, our approach captures both spatial-temporal details and higher-level semantic representations. Evaluations across diverse EEG paradigms show that it surpasses state-of-the-art methods and yields generalizable features suitable for various research and applied domains.

Addressing high computational costs, refining data augmentation, and improving feature interpretability will enhance scalability and usability. Future efforts will optimize model configurations, employ transfer learning, develop targeted augmentation strategies, and pursue neurophysiological validations to deepen understanding of the extracted features and their neural underpinnings.

References

- D. L. Schomer and F. H. Lopes da Silva, Niedermeyer’s Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields, 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.

- C. M. Michel and T. Koenig, "EEG Microstates as a Tool for Studying the Temporal Dynamics of Whole-Brain Neuronal Networks: A Review," NeuroImage, vol. 180, pp. 577-593, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Ahmadi and L. Mesin, "Enhancing Motor Imagery Electroencephalography Classification with a Correlation-Optimized Weighted Stacking Ensemble Model," Electronics, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 1033, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Ahmadi and L. Mesin, "Enhancing MI EEG Signal Classification With a Novel Weighted and Stacked Adaptive Integrated Ensemble Model: A Multi-Dataset Approach," IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 103626-103646, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Ahmadi, P. H. Ahmadi, P. Costa, and L. Mesin, "A Novel Hierarchical Binary Classification for Coma Outcome Prediction Using EEG, CNN, and Traditional ML Approaches," in TechRxiv, , 2024. 21 November. [CrossRef]

- H. Ahmadi, A. H. Ahmadi, A. Kuhestani, and L. Mesin, "Adversarial Neural Network Training for Secure and Robust Brain-to-Brain Communication," IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 39450-39469, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Ahmadi, A. H. Ahmadi, A. Kuhest, and L. Mesin, "Securing Brain-to-Brain Communication Channels Using Adversarial Training on SSVEP EEG," in TechRxiv, , 2024. 21 November. [CrossRef]

- M. Fahimi Hnazaee, E. M. Fahimi Hnazaee, E. Khachatryan, and M. M. Van Hulle, "Semantic Features Reveal Different Networks During Word Processing: An EEG Source Localization Study," Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 12, p. 503, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Ravi Kumar and Y. Srinivasa Rao, "Epileptic Seizures Classification in EEG Signal Based on Semantic Features and Variational Mode Decomposition," Cluster Computing, vol. 22, suppl. 6, pp. 13521–13531, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Sartori, D. G. Sartori, D. Polezzi, F. Mameli, and L. Lombardi, "Feature Type Effects in Semantic Memory: An Event Related Potentials Study," Neuroscience Letters, vol. 390, no. 3, pp. 139-144, Oct. 2005. [CrossRef]

- H. Zeng, N. H. Zeng, N. Xia, D. Qian, M. Hattori, C. Wang, and W. Kong, "DM-RE2I: A Framework Based on Diffusion Model for the Reconstruction from EEG to Image," Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, vol. 86, p. 105125, 23. 20 July. [CrossRef]

- H. Zeng, N. H. Zeng, N. Xia, M. Tao, D. Pan, H. Zheng, C. Wang, F. Xu, W. Zakaria, and G. Dai, "DCAE: A Dual Conditional Autoencoder Framework for the Reconstruction from EEG into Image," Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, vol. 81, p. 104440, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen, Y. J. Chen, Y. Liu, W. Xue, K. Hu, and W. Lin, "Multimodal EEG Emotion Recognition Based on the Attention Recurrent Graph Convolutional Network," Information, vol. 13, no. 11, p. 550, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Ouyang, M. J. Ouyang, M. Wu, X. Li, H. Deng, Z. Jin, and D. Wu, "NeuroBCI: Multi-Brain to Multi-Robot Interaction Through EEG-Adaptive Neural Networks and Semantic Communications," IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, vol. 23, no. 12, pp. 14622-14637, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Rueschemeyer, "Cross-Modal Integration of Lexical-Semantic Features during Word Processing: Evidence from Oscillatory Dynamics during EEG," PLOS ONE, vol. 9, no. 7, p. e101042, 14. 20 July. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, L. H. Chen, L. He, Y. Liu, and L. Yang, "Visual Neural Decoding via Improved Visual-EEG Semantic Consistency," ArXiv, Aug. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.06788.

- M. Rybář and I. Daly, "Neural Decoding of Semantic Concepts: A Systematic Literature Review," Journal of Neural Engineering, vol. 19, no. 2, p. 021002, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Rekrut, M. M. Rekrut, M. Sharma, M. Schmitt, J. Alexandersson, and A. Krüger, "Decoding Semantic Categories from EEG Activity in Object-Based Decision Tasks," in Proc. 2020 8th International Winter Conference on Brain-Computer Interface (BCI), Gangwon, Korea (South), 2020, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- M. Tangermann, K. M. Tangermann, K. Müller, A. Aertsen, N. Birbaumer, C. Braun, C. Brunner, R. Leeb, C. Mehring, K. J. Miller, G. Nolte, G. Pfurtscheller, H. Preissl, G. Schalk, A. Schlögl, C. Vidaurre, S. Waldert, and B. Blankertz, "Review of the BCI Competition IV," in Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 6, p. 21084, 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Leeb, F. R. Leeb, F. Lee, C. Keinrath, R. Scherer, H. Bischof, and G. Pfurtscheller, "Brain–Computer Communication: Motivation, Aim, and Impact of Exploring a Virtual Apartment," in IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 473-482, Dec. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M. , Wang, Y., Wang, T., & Jung, P. (2015). A Comparison Study of Canonical Correlation Analysis Based Methods for Detecting Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials. PLOS ONE, 0140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. , Kwon, O., Kim, Y., Kim, H., Lee, Y., Williamson, J., Fazli, S., & Lee, S. (2019). EEG dataset and OpenBMI toolbox for three BCI paradigms: An investigation into BCI illiteracy. GigaScience. [CrossRef]

- G. Van Veen, A. Barachant, A. Andreev, G. Cattan, P. C. Rodrigues, M. Congedo, "Building Brain Invaders: EEG data of an experimental validation," arXiv preprint. arXiv:1905.05182.

- E. Vaineau, A. E. Vaineau, A. Barachant, A. Andreev, P. C. Rodrigues, G. Cattan, M. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1904.09111.

- Barachant, M. Congedo, "A Plug & Play P300 BCI using Information Geometry," arXiv:1409.0107, 2014. arXiv:1409.0107.

- M. Congedo, M. M. Congedo, M. Goyat, N. Tarrin, G. Ionescu, B. Rivet, L. Varnet, R. Phlypo, N. Jrad, M. Acquadro, C. Jutten, "‘Brain Invaders’: a prototype of an open-source P300-based video game working with the OpenViBE platform," in Proc. IBCI Conf., Graz, Austria, 2011, pp. 280-283.

- Korczowski, E. Ostaschenko, A. Andreev, G. Cattan, P. L. C. Rodrigues, V. Gautheret, M. Congedo, "Brain Invaders Solo versus Collaboration: Multi-User P300-Based Brain-Computer Interface Dataset (BI2014b)," 2019. [Online]. Available: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02173958.

- L. Korczowski, M. Cederhout, A. Andreev, G. Cattan, P. L. C. Rodrigues, V. Gautheret, M. Congedo, "Brain Invaders calibration-less P300-based BCI with modulation of flash duration Dataset (BI2015a)," 2019. [Online]. Available: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02172347.

- L. Korczowski, M. Cederhout, A. Andreev, G. Cattan, P. L. C. Rodrigues, V. Gautheret, M. Congedo, "Brain Invaders Cooperative versus Competitive: Multi-User P300-based Brain-Computer Interface Dataset (BI2015b)," 2019. [Online]. Available: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02172347.

- A. Riccio, L. A. Riccio, L. Simione, F. Schettini, A. Pizzimenti, M. Inghilleri, M. O. Belardinelli, D. Mattia, F. Cincotti, "Attention and P300-based BCI performance in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis," Front. Hum. Neurosci., vol. 7, pag. 732, 2013.

- L. A. Farwell and E. Donchin, "Talking off the top of your head: toward a mental prosthesis utilizing event-related brain potentials," Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, vol. 70, no. 6, pp. 510-523, Dec. 1988. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Aricò, F. P. Aricò, F. Aloise, F. Schettini, S. Salinari, D. Mattia, F. Cincotti, "Influence of P300 latency jitter on event related potential-based brain–computer interface performance," Journal of Neural Engineering, vol. 11, no. 3, 2013.

- J. Sosulski, M. J. Sosulski, M. Tangermann, "Electroencephalogram signals recorded from 13 healthy subjects during an auditory oddball paradigm under different stimulus onset asynchrony conditions," Dataset, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Sosulski, M. J. Sosulski, M. Tangermann, "Spatial filters for auditory evoked potentials transfer between different experimental conditions," in Graz BCI Conference, 2019.

- J. Sosulski, D. Hübner, A. Klein, M. Tangermann, "Online Optimization of Stimulation Speed in an Auditory Brain-Computer Interface under Time Constraints," arXiv preprint, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.06083.

- K. K. Ang, Z. Y. K. K. Ang, Z. Y. Chin, C. Wang, C. Guan, and H. Zhang, "Filter Bank Common Spatial Pattern Algorithm on BCI Competition IV Datasets 2a and 2b," Front. Neurosci., vol. 6, Mar. 2012, Art. no. 39. [CrossRef]

- R. T. Schirrmeister, J. T. R. T. Schirrmeister, J. T. Springenberg, L. D. Josef Fiederer, M. Glasstetter, K. Eggensperger, M. Tangermann, F. Hutter, W. Burgard, and T. Ball, "Deep learning with convolutional neural networks for EEG decoding and visualization," Hum. Brain Mapp., vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 5391–5420, 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. J. Lawhern, A. J. V. J. Lawhern, A. J. Solon, N. R. Waytowich, S. M. Gordon, C. P. Hung, and B. J. Lance, "EEGNet: a compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based brain-computer interfaces," J. Neural Eng., vol. 15, no. 5, Oct. 2018, Art. no. 056013. [CrossRef]

- S. Sakhavi, C. S. Sakhavi, C. Guan, and S. Yan, "Learning Temporal Information for Brain-Computer Interface Using Convolutional Neural Networks," IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., vol. 29, no. 11, pp. 5619–5629, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Mane, E. R. Mane, E. Chew, K. Chua, K. K. Ang, N. Robinson, A. P. Vinod, S. Lee, and C. Guan, "FBCNet: A Multi-view Convolutional Neural Network for Brain-Computer Interface," arXiv, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.01233.

- H. Zhao, Q. H. Zhao, Q. Zheng, K. Ma, H. Li, and Y. Zheng, "Deep Representation-Based Domain Adaptation for Nonstationary EEG Classification," IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 535–545, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Song, Q. Y. Song, Q. Zheng, B. Liu, and X. Gao, "EEG Conformer: Convolutional Transformer for EEG Decoding and Visualization," IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng., vol. 31, pp. 710–719, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Lin, C. Z. Lin, C. Zhang, W. Wu, and X. Gao, "Frequency Recognition Based on Canonical Correlation Analysis for SSVEP-Based BCIs," IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 53, no. 12, pp. 2610–2614, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

- A. Salami, J. A. Salami, J. Andreu-Perez, and H. Gillmeister, "EEG-ITNet: An Explainable Inception Temporal Convolutional Network for Motor Imagery Classification," IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 36672–36685, 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, X. X. Chen, X. Teng, H. Chen, Y. Pan, and P. Geyer, "Toward reliable signals decoding for electroencephalogram: A benchmark study to EEGNeX," Biomed. Signal Process. Control, vol. 87, Art. no. 105475, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Barachant, S. A. Barachant, S. Bonnet, M. Congedo, and C. Jutten, "Multiclass Brain–Computer Interface Classification by Riemannian Geometry," IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 59, no. 4, pp. 920–928, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Barachant, S. A. Barachant, S. Bonnet, M. Congedo, and C. Jutten, "Riemannian geometry applied to BCI classification," in Proc. 9th Int. Conf. Latent Variable Analysis and Signal Separation (LVA/ICA’10), St. Malo, France, 2010, pp. 629–636. Springer-Verlag. [CrossRef]

- M. Nakanishi, Y. M. Nakanishi, Y. Wang, X. Chen, Y.-T. Wang, X. Gao, and T.-P. Jung, "Enhancing Detection of SSVEPs for a High-Speed Brain Speller Using Task-Related Component Analysis," IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 104–112, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Barachant and M. Congedo, "A Plug&Play P300 BCI Using Information Geometry," arXiv, 2014. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.0107.

- A. Barachant, "MEG Decoding Using Riemannian Geometry and Unsupervised Classification," Technical Report, 2014. [Online]. Available: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid = rep1&type = pdf. doi = 753be0d9cf14014b2e6ac0f9e2a861d9b1468461.

- S. Chevallier et al., "Brain-Machine Interface for Mechanical Ventilation Using Respiratory-Related Evoked Potential," in Proc. Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning – ICANN 2018, V. Kůrková, Y. Manolopoulos, B. Hammer, L. Iliadis, and I. Maglogiannis, Eds., Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 11141, Cham: Springer, 2018. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Overview of the Latent Semantic Feature Extraction System. The architecture comprises an Encoder (orange), a bridging layer for Latent Semantic Features, and a Decoder (green).

Figure 1.

Overview of the Latent Semantic Feature Extraction System. The architecture comprises an Encoder (orange), a bridging layer for Latent Semantic Features, and a Decoder (green).

Figure 2.

Training and validation loss curves for the BCICIV_2a MI dataset, illustrating stable convergence and generalization.

Figure 2.

Training and validation loss curves for the BCICIV_2a MI dataset, illustrating stable convergence and generalization.

Figure 3.

Comparison of original and reconstructed EEG signals (one channel per subject, one single epoch shown), demonstrating accurate signal preservation by the latent semantic features.

Figure 3.

Comparison of original and reconstructed EEG signals (one channel per subject, one single epoch shown), demonstrating accurate signal preservation by the latent semantic features.

Figure 4.

Correlation heatmaps of latent semantic features for each subject, illustrating the structural patterns of inter-feature relationships. Each matrix demonstrates subject-specific correlations, highlighting both shared and unique feature dynamics across subjects.

Figure 4.

Correlation heatmaps of latent semantic features for each subject, illustrating the structural patterns of inter-feature relationships. Each matrix demonstrates subject-specific correlations, highlighting both shared and unique feature dynamics across subjects.

Figure 5.

Aggregate ROC curve over all subjects for the BCICIV_2a MI dataset. The plot illustrates class-wise performance with respective AUC values, demonstrating the model’s ability to discriminate between multiple MI classes.

Figure 5.

Aggregate ROC curve over all subjects for the BCICIV_2a MI dataset. The plot illustrates class-wise performance with respective AUC values, demonstrating the model’s ability to discriminate between multiple MI classes.

Figure 6.

Filtered correlation heatmaps after applying a 0.65 threshold. Lower-performing subjects (A02, A05) retained fewer features (11, 12), indicating higher redundancy, while higher performers (A03, A08) kept more features (22, 29), reflecting richer, more informative sets.

Figure 6.

Filtered correlation heatmaps after applying a 0.65 threshold. Lower-performing subjects (A02, A05) retained fewer features (11, 12), indicating higher redundancy, while higher performers (A03, A08) kept more features (22, 29), reflecting richer, more informative sets.

Figure 7.

Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of semantic features. A distance threshold (7.5) reveals four clusters corresponding to the BCICIV_2a MI dataset classes, highlighting the features’ ability to capture class-specific patterns without supervision.

Figure 7.

Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of semantic features. A distance threshold (7.5) reveals four clusters corresponding to the BCICIV_2a MI dataset classes, highlighting the features’ ability to capture class-specific patterns without supervision.

Figure 8.

PCA of latent semantic features, visualized for all subjects in the BCICIV_2a dataset. Each point represents a feature projection onto the first two principal components, with colors corresponding to individual subjects, highlighting the variability and clustering patterns unique to each participant.

Figure 8.

PCA of latent semantic features, visualized for all subjects in the BCICIV_2a dataset. Each point represents a feature projection onto the first two principal components, with colors corresponding to individual subjects, highlighting the variability and clustering patterns unique to each participant.

Figure 9.

PCA of latent semantic features, grouped by K-means clustering (k=4). The clusters demonstrate the natural grouping of features into distinct categories, corresponding to shared neural patterns across the BCICIV_2a dataset classes, underscoring the model’s ability to capture task-relevant information.

Figure 9.

PCA of latent semantic features, grouped by K-means clustering (k=4). The clusters demonstrate the natural grouping of features into distinct categories, corresponding to shared neural patterns across the BCICIV_2a dataset classes, underscoring the model’s ability to capture task-relevant information.

Figure 10.

Silhouette plot confirms strong cluster cohesion and separation.

Figure 10.

Silhouette plot confirms strong cluster cohesion and separation.

Figure 11.

Ablation analysis of reconstruction error distributions for different Transformer configurations. The baseline (4 layers, 8 heads) shows the lowest error variance, while reducing attention heads or layers increases variance, confirming the baseline’s near-optimal performance.

Figure 11.

Ablation analysis of reconstruction error distributions for different Transformer configurations. The baseline (4 layers, 8 heads) shows the lowest error variance, while reducing attention heads or layers increases variance, confirming the baseline’s near-optimal performance.

Table 1.

MI datasets with their specifications.

Table 1.

MI datasets with their specifications.

| Attribute |

BCICIV_2a [19] |

BCICIV_2b [20] |

| Subjects |

9 |

9 |

| Channels |

22 |

3 |

| Classes |

4 |

2 |

| Trials/class |

144 |

360 |

| Trial Duration |

4s |

4.5s |

| Sampling Rate |

250Hz |

250Hz |

| Sessions |

2 |

5 |

| Runs |

6 |

1 |

| Total trials |

62208 |

32400 |

Table 2.

SSVEP datasets with their specifications.

Table 2.

SSVEP datasets with their specifications.

| Attribute |

Lee2019_SSVEP [22] |

Nakanishi2015 [21] |

| Subjects |

54 |

9 |

| Channels |

62 |

8 |

| Classes |

4 |

12 |

| Trials/class |

50 |

15 |

| Trial length |

4s |

4.15s |

| Sampling rate |

1000Hz |

256Hz |

| Sessions |

2 |

1 |

Table 3.

ERP datasets with their specifications.

Table 3.

ERP datasets with their specifications.

| Dataset |

Subjects |

Channels |

Trials/class |

Trial Duration |

Sampling rate |

Sessions |

| BI2012 [23] |

25 |

16 |

640 NT / 128 T |

1s |

128Hz |

2 |

| BI2013a [24,25,26] |

24 |

16 |

3200 NT / 640 T |

1s |

512Hz |

8 1

|

| BI2014b [27] |

38 |

32 |

200 NT / 40 T |

1s |

512Hz |

3 |

| BI2015a [28] |

43 |

32 |

4131 NT / 825 T |

1s |

512Hz |

3 |

| BI2015b [29] |

44 |

32 |

2160 NT / 480 T |

1s |

512Hz |

1 |

| BNCI2014_008 [30,31] |

8 |

8 |

3500 NT / 700 T |

1s |

256Hz |

1 |

| BNCI2014_009 [32] |

10 |

16 |

1440 NT / 288 T |

0.8s |

256Hz |

3 |

| Sosulski2019 [33,34,35] |

13 |

31 |

7500 NT / 1500 T |

1.2s |

1000Hz |

1 |

|

Note 1: For the BI2013a dataset, there are eight sessions for subjects 1-7 and one session for all other subjects. |

Table 4.

Comparisons With State-of-the-Art Methods on Dataset BCICIV_2a (Accuracy).

Table 4.

Comparisons With State-of-the-Art Methods on Dataset BCICIV_2a (Accuracy).

| Methods |

. S01 |

S02 |

S03 |

S04 |

S05 |

S06 |

S07 |

S08 |

S09 |

Average |

| FBCSP [36] |

76.00 |

56.50 |

81.25 |

61.00 |

55.00 |

45.25 |

82.75 |

81.25 |

70.75 |

67.75 |

| ConvNet [37] |

76.39 |

55.21 |

89.24 |

74.65 |

56.94 |

54.17 |

92.71 |

77.08 |

76.39 |

72.53 |

| EEGNet [38] |

85.76 |

61.46 |

88.54 |

67.01 |

55.90 |

52.08 |

89.58 |

83.33 |

86.81 |

74.50 |

| C2CM [39] |

87.50 |

65.28. |

90.28 |

66.67 |

62.50 |

45.49 |

89.58 |

83.33 |

79.51 |

74.46 |

| FBCNet [40] |

85.42 |

60.42 |

90.63 |

76.39 |

74.31 |

53.82 |

84.38 |

79.51 |

80.90 |

76.20 |

| DRDA [41] |

83.19 |

55.14 |

87.43 |

75.28 |

62.29 |

57.15 |

86.18 |

83.61 |

82.00 |

74.74 |

| Conformer [42] |

88.19 |

61.46 |

93.40 |

78.13 |

52.08 |

65.28 |

92.36 |

88.19 |

88.89 |

78.66 |

| This study |

89.65 |

71.69 |

95.16 |

86.19 |

65.09 |

76.17 |

89.99 |

92.40 |

85.15 |

83.50 |

| Average Accuracy |

84.01 |

60.90 |

89.49 |

73.17 |

60.51 |

56.18 |

88.44 |

83.59 |

81.30 |

- |

Table 5.

Comparisons With State-of-the-Art Methods on Dataset BCICIV_2b (Accuracy).

Table 5.

Comparisons With State-of-the-Art Methods on Dataset BCICIV_2b (Accuracy).

| Methods |

S01 |

S02 |

S03 |

S04 |

S05 |

S06 |

S07 |

S08 |

S09 |

Average |

| FBCSP [36] |

70.00 |

60.36 |

60.94 |

97.50 |

93.12 |

80.63 |

78.13 |

92.50 |

86.88 |

80.00 |

| ConvNet [37] |

76.56 |

50.00 |

51.56 |

96.88 |

93.13 |

85.31 |

83.75 |

91.56 |

85.62 |

79.37 |

| EEGNet [38] |

75.94 |

57.64 |

58.43 |

98.13 |

81.25 |

88.75 |

84.06 |

93.44 |

89.69 |

80.48 |

| DRDA [41] |

81.37 |

62.86 |

63.63 |

95.94 |

93.56 |

88.19 |

85.00 |

95.25 |

90.00 |

83.98 |

| Conformer [42] |

82.50 |

65.71 |

63.75 |

98.44 |

86.56 |

90.31 |

87.81 |

94.38 |

92.19 |

84.63 |

| This study |

89.5 |

78.5 |

71.5 |

96.67 |

87.86 |

85.25 |

83.25 |

87.05 |

84.00 |

84.84 |

| Average |

79.31 |

62.51 |

61.64 |

97.26 |

89.25 |

86.41 |

83.67 |

92.36 |

88.06 |

- |

Table 6.

Comparisons With State-of-the-Art Methods on SSVEP Datasets (Accuracy).

Table 6.

Comparisons With State-of-the-Art Methods on SSVEP Datasets (Accuracy).

| Methods |

Lee2019-SSVEP |

Nakanishi2015 |

| CCA [43] |

90.97 |

92.53 |

| EEGITNet [44] |

86.84 |

80.86 |

| EEGNeX [45] |

93.81 |

82.65 |

| EEGNet [38] |

64.43 |

44.14 |

| MDM [46] |

75.38 |

78.77 |

| Barachant et al. [47] |

89.44 |

87.22 |

| ConvNet [37] |

69.36 |

57.47 |

| TRCA [48] |

97.78 |

99.20 |

| This Study |

98.41 |

99.66 |

Table 7.

Comparisons With State-of-the-Art Methods on P300 Datasets (AUC).

Table 7.

Comparisons With State-of-the-Art Methods on P300 Datasets (AUC).

| Methods |

BNCI2014-008 |

BNCI2014-009 |

BI2012 |

BI2013a |

BI2014b |

BI2015a |

BI2015b |

Sosulski2019 |

Average |

| EEGITNet [44] |

86.00 |

92.21 |

89.65 |

90.01 |

86.27 |

90.71 |

83.33 |

88.82 |

88.37 |

| EEGNeX [45] |

83.86 |

90.58 |

88.22 |

88.62 |

83.87 |

87.62 |

81.60 |

86.18 |

86.39 |

| EEGNet [38] |

85.91 |

91.37 |

87.13 |

85.40 |

80.14 |

86.80 |

86.63 |

87.14 |

86.31 |

| ERPCov+MDM [49] |

74.30 |

81.16 |

82.90 |

82.02 |

71.62 |

77.52 |

72.07 |

68.17 |

76.22 |

| ERPCov(svdn4)+MDM [49] |

75.42 |

84.52 |

79.02 |

82.07 |

76.48 |

77.92 |

77.09 |

70.63 |

77.89 |

| ConvNet [37] |

81.07 |

85.12 |

77.06 |

74.50 |

63.75 |

59.56 |

73.20 |

78.35 |

74.07 |

| LDA [37] |

82.24 |

64.03 |

76.74 |

76.60 |

73.02 |

76.02 |

77.74 |

67.49 |

74.23 |

| Barachant et al. [50] |

77.62 |

92.04 |

88.22 |

97.09 |

88.58 |

92.57 |

83.48 |

86.07 |

88.21 |

| Chevallier et al. [51] |

85.61 |

93.15 |

90.99 |

92.71 |

91.88 |

93.05 |

84.56 |

98.44 |

91.30 |

| This study |

96.74 |

91.95 |

92.86 |

90.32 |

89.93 |

91.43 |

95.12 |

86.07 |

91.80 |

Table 8.

ANOVA Results for Subject A03 Filtered Features ()

Table 8.

ANOVA Results for Subject A03 Filtered Features ()

| Feature |

F-Statistic |

p-value |

Feature |

F-Statistic |

p-value |

Feature |

F-Statistic |

p-value |

Feature |

F-Statistic |

p-value |

| 4 |

2.12 |

3.0290e-02 |

31 |

4.44 |

2.2074e-05 |

61 |

4.54 |

1.5580e-05 |

99 |

2.51 |

1.0203e-02 |

| 9 |

3.64 |

3.0569e-04 |

34 |

3.76 |

2.0664e-04 |

63 |

3.29 |

9.3683e-04 |

101 |

3.31 |

8.8735e-04 |

| 13 |

3.22 |

1.1641e-03 |

35 |

3.61 |

3.3751e-04 |

70 |

2.34 |

1.6581e-02 |

104 |

2.65 |

6.6284e-03 |

| 20 |

2.55 |

8.8489e-03 |

41 |

3.44 |

5.7951e-04 |

94 |

2.36 |

1.5399e-02 |

105 |

2.06 |

3.6188e-02 |

| 21 |

3.23 |

1.1200e-03 |

42 |

3.83 |

1.6363e-04 |

95 |

2.28 |

1.9735e-02 |

— |

— |

— |

| 28 |

3.91 |

1.2523e-04 |

56 |

2.71 |

5.4968e-03 |

98 |

2.64 |

6.8202e-03 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).