1. Introduction

Cardiomyopathies represent a heterogeneous group of primary myocardial diseases that include a broad spectrum of structural and functional abnormalities, frequently leading to heart failure, arrhythmic events, and sudden cardiac death. Historically, their classification was predominantly based on morphological and functional phenotypes, giving rise to four major categories: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM), and arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. While this phenotype-based nomenclature provided a practical framework for diagnosis and management, it often failed to capture the underlying complexity and the overlapping features that exist among these entities.

The advances in molecular genetics have significantly reshaped the concept of cardiomyopathies by enabling the identification of pathogenic mutations underlying diverse phenotypes. The integration of genetic insights with multimodality imaging has facilitated a more precise delineation of genotype–phenotype correlations, thereby enhancing risk stratification, refining prognostic assessment, and informing the development of personalized, mechanism-based therapeutic strategies.

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) represents a rare form of cardiomyopathy characterized by diastolic dysfunction with preserved systolic function, often accompanied by marked biatrial enlargement [

1]. Although RCM is most associated with infiltrative or storage diseases, it can also arise from genetic causes. Notably, pathogenic variants in the MYH7 gene—frequently implicated in HCM—have been identified in patients presenting with overlapping features of hypertrophic, dilated, and restrictive cardiomyopathies. Such MYH7-related cardiomyopathies may manifest as mixed phenotypes, exhibiting combined features of HCM and RCM, thereby complicating accurate diagnosis.

Imaging modalities, particularly cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR)—play a key role in the differential diagnosis of cardiomyopathies. CMR provides a comprehensive assessment of myocardial structure and tissue characteristics by integrating data from Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), T1 mapping, and Extracellular volume (ECV) quantification. This combined approach enables the detection, distribution, and quantification of myocardial fibrosis, which differs in localization and extent across various cardiomyopathy subtypes. These tissue-specific signatures not only improve the accuracy of distinguishing between different cardiomyopathies but also provide prognostic information [

2,

3,

4].

2. Case Presentation

A 25-year-old patient, with no personal history of cardiovascular disease and no significant family history, was admitted to the Cardiology Department of our Emergency County hospital for a near-syncopal episode, progressive fatigue, and mild exertional dyspnea. On admission, vital signs were largely within normal limits, except for a borderline low blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg and bradycardia with a heart rate of 55 beats per minute. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air.

Cardiopulmonary auscultation revealed rhythmic heart sounds with no murmurs and clear lung fields. Initial laboratory investigations, including routine hematological and biochemical panels, were within normal limits. Blood tests for HIV 1 and 2 as well as hepatitis antigens and antibodies were also normal, excluding viral related cardiomyopathy [

5].

Chest radiography demonstrated reticulo-micronodular opacities of low intensity in the bilateral basal regions, with cardiac silhouette abnormalities including a more convex lower left cardiac border, a prominent middle arch, and a blurred aortic knob—suggestive of subtle structural changes.

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus bradycardia (52 bpm), narrow QRS complexes, and repolarization abnormalities characterized by ST segment depression and negative T waves in leads I, II, aVL, and V2–V6. Moreover, 24-hour Holter monitoring confirmed a sinus rhythm without sustained arrhythmia or RR pauses greater than 2 seconds. There were occasional supraventricular ectopic beats, but no significant rhythm disturbances.

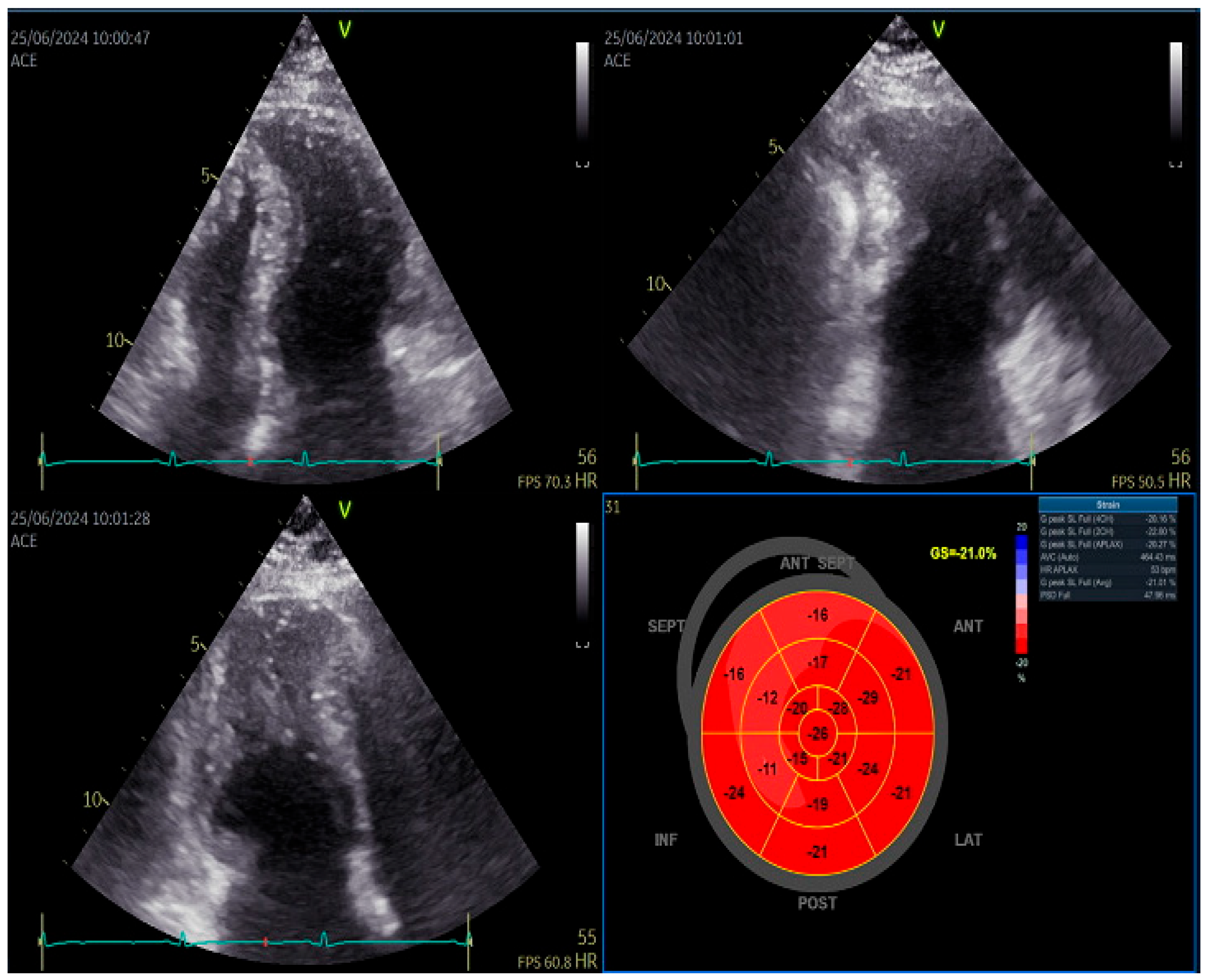

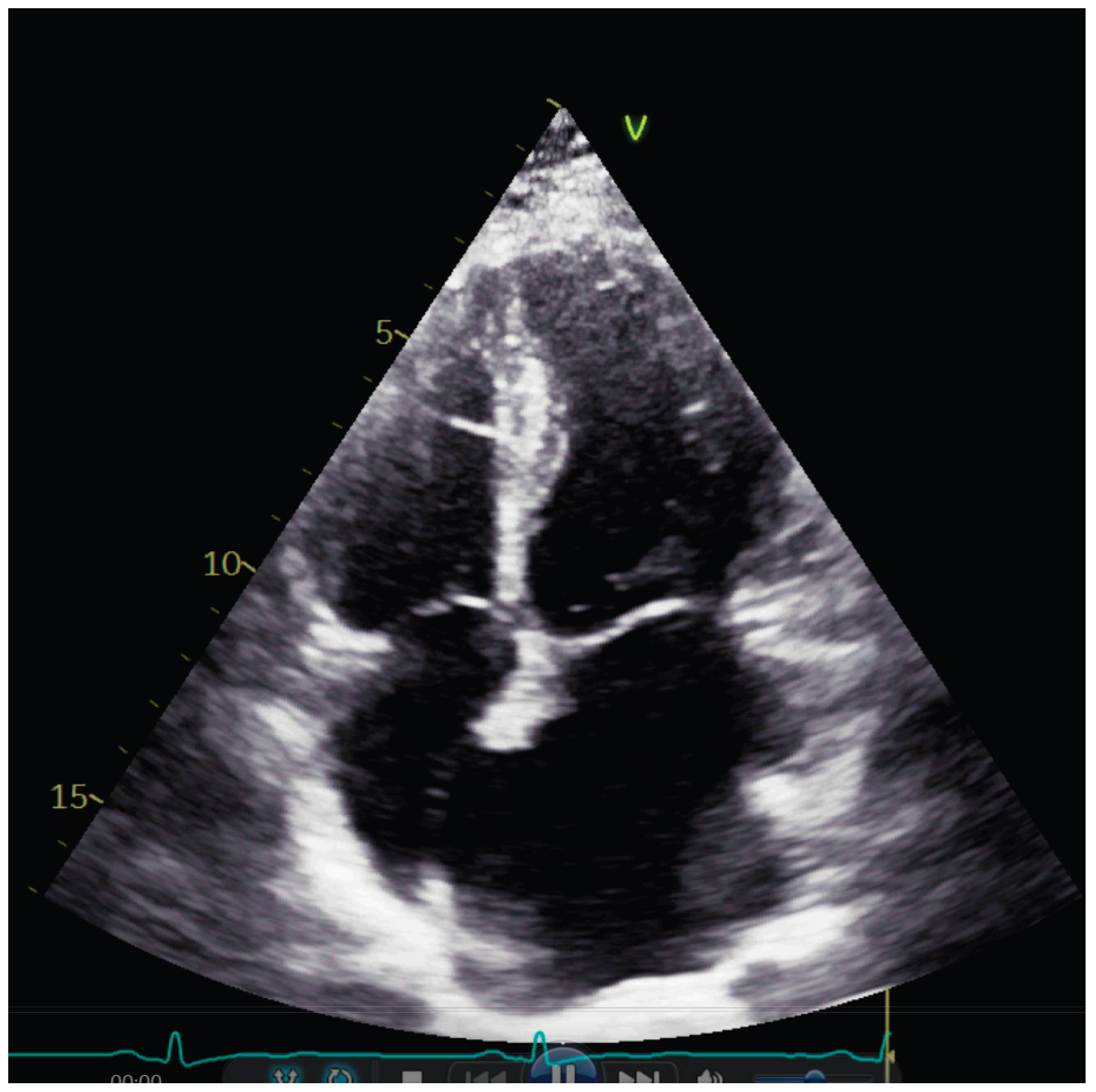

Transthoracic echocardiography showed normal diameters and volumes of the left ventricle. Interventricular wall thickness (IVWT) was within the normal ranges, respectively 8 mm. Transmitral Doppler showed a restrictive filling pattern with elevated E/A ratio and shortened deceleration time, consistent with impaired diastolic compliance. Extreme left atrium (LA) dilatation was observed, with the volume of 134 mL/m2. (

Figure 1)

Speckle tracking echocardiography revealed normal GLS and slightly decreased septal longitudinal strain but still within the normal ranges [

6]. Left atrium strain showed reduced reservoir function (27%).

Figure 2.

Left ventricular speckle tracking echocardiography showing slightly reduced septal longitudinal strain.

Figure 2.

Left ventricular speckle tracking echocardiography showing slightly reduced septal longitudinal strain.

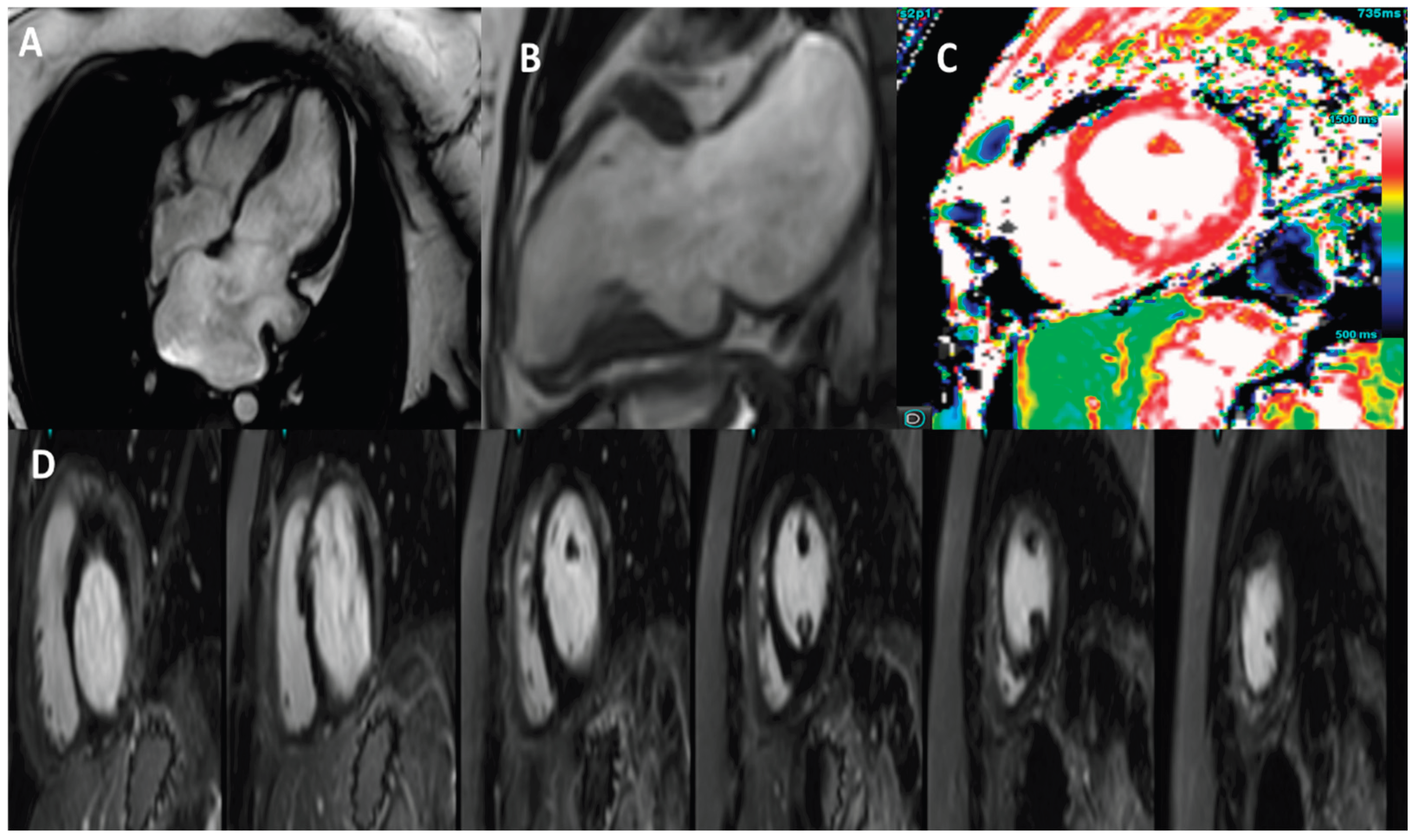

The patient underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, which subsequently revealed left ventricular volumes at the upper limits of normal with preserved systolic function (LVEF = 62%). CMR derived GLS was slightly decreased, –16.6%. IVWT and PWT were 8 mm respectively 9 mm. Moreover, no regional wall motion abnormalities were identified except the presence of a small aneurysmal outpouching in the basal inferior wall.

Native T1 values were mildly elevated, indicating diffuse interstitial myocardial fibrosis, while T2 values were normal, ruling out active myocardial edema. Mild mitral regurgitation was also detected on cine images with severe left atrial dilation. The absence of late gadolinium enhancement and normal T2 values argued against infiltrative or inflammatory cardiomyopathies, supporting a primary genetic etiology. Pericardial thickness was normal and no septal bounce or respiratory interventricular dependence was observed on cine imaging, making constriction unlikely.

Invasive hemodynamic confirmation was not performed; the diagnosis was based on noninvasive findings consistent with restrictive physiology.

Figure 3.

3 Tesla cardiac magnetic resonance images. A) Horizontal long axis view showing the enlarged left atrium. B) Vertical long axis view showing a basal inferior wall aneurysm. C) T1 native mapping with a value of 1260 ms. D) Phase-sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) showing no LGE enhancement .

Figure 3.

3 Tesla cardiac magnetic resonance images. A) Horizontal long axis view showing the enlarged left atrium. B) Vertical long axis view showing a basal inferior wall aneurysm. C) T1 native mapping with a value of 1260 ms. D) Phase-sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) showing no LGE enhancement .

The patient was discharged 3 days from the admission with no recommendation for cardiac medication, only ambulatory cardiological follow-up at six months. At six months follow-up, biological tests—including natriuretic peptide levels—remained within normal ranges.

Genetic testing using whole exome sequencing was recommended which identified the pathogenic genetic variant MYH7 – NM_000257.4:c.2162G>A in a heterozygous state, and the likely pathogenic genetic variant ABCC9 – NM_020297.4:c.3557G>A, also in a heterozygous state, a result that may explain the reported phenotype.

3. Discussion

Restrictive cardiomyopathy represents the rarest form of cardiomyopathy, accounting for approximately 5% of all cardiomyopathy cases, although its true prevalence remains insufficiently defined due to limited epidemiological data [

7,

8]. Current knowledge remains restricted as most available data are derived from small case series, registry-based cohorts, or single-case reports, which limits the generalizability of clinical and genetic observations.

Its rarity and heterogeneity pose substantial diagnostic challenges, as the wide range of underlying etiologies, clinical presentations, and overlapping imaging findings complicate accurate recognition and classification.

Notably, familial forms represent an even smaller subset, accounting for approximately 30% of reported cases of RCM [

7,

8]. Familial RCM is of particular clinical relevance because its manifestations can emerge at any stage of life, from childhood through adulthood. The disease is typically progressive, often presenting with signs of pulmonary and systemic venous congestion, and is associated with poor clinical outcomes if left untreated. Reported five-year mortality rates in familial or genetically confirmed RCM approach 25–30%, particularly in pediatric cohorts, underscoring its aggressive natural history [

9,

10,

11].

In the present case, the diagnosis was established in adulthood on the basis of mild clinical symptoms, and the patient had exhibited no symptoms during childhood, maintaining normal exercise tolerance throughout early life. Unlike previously reported MYH7-related restrictive cardiomyopathies, which often present with hypertrophy or early clinical deterioration, our patient exhibited preserved systolic function, absence of hypertrophy, and minimal fibrosis, suggesting a potentially distinct disease trajectory. In this context, multimodality imaging has emerged as a key tool for early and accurate phenotypic characterization of cardiomyopathies, particularly in genetically determined disease with atypical or overlapping features. Previous reports have demonstrated that the combined use of echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging allows refined myocardial assessment and improves diagnostic precision beyond conventional morphological criteria alone [

12]. A key limitation of this report is the absence of invasive hemodynamic assessment, which remains the reference standard for confirming restrictive physiology and for differentiating restrictive cardiomyopathy from constrictive pericarditis or other causes of diastolic dysfunction.

From a genetic standpoint, the TNNI3 and TNNT2 genes are the most commonly implicated in hereditary forms of RCM.

Pathogenic variants in MYH7 are well-established contributors to HCM and DCM, frequently showing marked intra- and interfamilial phenotypic heterogeneity and occasionally involving skeletal muscle [

13]. Although rare, certain MYH7 variants have been reported in patients with restrictive phenotypes, typically associated with a more unfavorable clinical course [

14]. Even rarer are cases with concomitant variants in MYH7 and ABCC9, sporadically described in association with RCM [

15].

ABCC9 encodes the sulfonylurea receptor 2 (SUR2) subunit of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel, and pathogenic variants have been linked to myocardial channelopathies and cardiomyopathic syndromes. Such variants may also contribute to bradycardia, likely through impaired channel function affecting cardiac action potential repolarization and may explain the low heart rate of the patient [

16].

Beyond diagnosis, risk stratification is crucial in RCM, particularly with respect to arrhythmic events and progression to advanced heart failure. Arrhythmias are frequently observed in restrictive cardiomyopathies. Atrial fibrillation represents the most common manifestation, whereas ventricular tachycardia occurs less frequently but is associated with a markedly increased risk of mortality. Bradycardia and conduction disturbances are also commonly encountered, although their prognostic implications remain less clearly defined. [

17,

18]

Genetic restrictive cardiomyopathy carries an unfavourable prognosis, with elevated mortality rates and a considerable likelihood of requiring heart transplantation within the early years following diagnosis, particularly in paediatric populations. In adults, survival tends to be comparatively longer; nevertheless, the disease remains associated with a markedly increased risk of sudden cardiac death and progressive heart failure [

16,

17].

Emerging precision therapies—including gene therapy, allele-specific silencing, and other molecular interventions aimed at correcting or compensating for underlying pathogenic variants—hold promise as future disease-modifying treatments. Preclinical models, including patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cell cardiomyocytes and engineered heart tissues, have demonstrated functional improvement, supporting the feasibility of gene-based interventions for genetic RCM. Although still experimental, these approaches represent a shift from supportive care to targeted therapy in this type of cardiomyopathy [

19,

20]

Future research should focus on establishing multicenter registries, integrating deep phenotyping with next-generation sequencing and advanced imaging techniques (e.g., Cardiac magnetic resonance) to refine risk stratification and identify disease-modifying pathways.

4. Conclusions

Restrictive cardiomyopathy is a rare but clinically severe condition, particularly in familial and pediatric cases which often pose diagnostic challenges. Severe atrial enlargement with restrictive physiology in a non-hypertrophic heart should prompt early genetic evaluation, even in young adults with mild symptoms. Early incorporation of genetic testing and multimodality imaging is essential for improving diagnostic accuracy and guiding management in patients with suspected RCM, particularly when clinical features are atypical.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and O.M.; methodology, M.P., O.M., V.R., R.I.R., G.C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M.; M.P, I.D., G.C.M, R.I.R.; writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Article Processing Charges were funded by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Craiova, Romania

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were obtained for this study (no. 74 from 7.09.2020)

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rapezzi, C.; Aimo, A.; Barison, A.; Emdin, M.; Porcari, A.; Linhart, A. Restrictive cardiomyopathy: definition and diagnosis. Eur Heart J. 2022, 43, 4679–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosadurg, N.; Lozano, P.R.; Patel, A.R.; Kramer, C.M. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in the Evaluation and Management of Nonischemic Cardiomyopathies. JACC Heart Fail. 2025, 13, 102525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Cheng, W.; Wan, K.; Li, W.; Pu, L. Incremental significance of myocardial oedema for prognosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2023, 24, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, Z.; Yao, J.; Chan, R.H.; He, J.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Y. Prognostic Value of LGE-CMR in HCM: A Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016, 9, 1392–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Șoldea, S.; Iovănescu, M.; Berceanu, M.; Mirea, O.; Raicea, V.; Beznă, M.C.; et al. Cardiovascular Disease in HIV Patients: A Comprehensive Review of Current Knowledge and Clinical Implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraru, L.; Mirea, O.; Toader, D.; Berceanu, M.; Soldea, S.; Munteanu, A. Lower Limit of Normality of Segmental Multilayer Longitudinal Strain in Healthy Adult Subjects. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2024, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowda, S.N.; Ali, H.J.; Hussain, I. Overview of Restrictive Cardiomyopathies. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2022, 18, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimiotti, D.; Budde, H.; Hassoun, R.; Jaquet, K. Genetic Restrictive Cardiomyopathy: Causes and Consequences-An Integrative Approach. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denfield, S.W.; Rosenthal, G.; Gajarski, R.J.; Bricker, J.T.; Schowengerdt, K.O.; Price, J.K.; Towbin, J.A. Restrictive cardiomyopathies in childhood. Etiologies and natural history. Tex Heart Inst J. 1997, 24, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ishida, H.; Narita, J.; Ishii, R.; Suginobe, H.; Tsuro, H.; Wang, R. Clinical Outcomes and Genetic Analyses of Restrictive Cardiomyopathy in Children. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2023, 16, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chintanaphol, M.; Orgil, B.O.; Alberson, N.R.; Towbin, J.A.; Purevjav, E. Restrictive cardiomyopathy: from genetics and clinical overview to animal modeling. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 23, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iovănescu, M.L.; Hădăreanu, D.R.; Militaru, S.; et al. The Value of Multimodal Imaging in Early Phenotyping of Cardiomyopathies: A Family Case Report. J Pers Med. 2023, 13, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Peng, L.; Zhao, C. MYH7 in cardiomyopathy and skeletal muscle myopathy. Mol Cell Biochem. 2024, 479, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.; Mo, H.; Hua, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Q.; Song, J. MYH7 Mutations in Restrictive Cardiomyopathy. JACC Adv. 2025, 4, 101693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neagoe, O.; Ciobanu, A.; Diaconu, R.; Mirea, O.; Donoiu, I.; Militaru, C. A rare case of familial restrictive cardiomyopathy, with mutations in MYH7 and ABCC9 genes. Discoveries (Craiova) 2019, 7, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liang, Z.; Wu, Y. Reevaluating the Mutation Classification in Genetic Studies of Bradycardia Using ACMG/AMP Variant Classification Framework. Int J Genomics 2020, 2020, 2415850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, J.; Lu, F.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Bai, Y. Prevalence and Impact of Arrhythmia on Outcomes in Restrictive Cardiomyopathy-A Report from the Beijing Municipal Health Commission Information Center (BMHCIC) Database. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinagra, G.; Carriere, C.; Clemenza, F.; Minà, C.; Bandera, F.; Zaffalon, D. Risk stratification in cardiomyopathy. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020, 27(2_suppl), 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, V.N.; Day, S.M.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Adler, E.D.; Olivotto, I.; Seidman, C.E. Advances in the study and treatment of genetic cardiomyopathies. Cell. 2025, 188, 901–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M.; Miki, K.; Kawamura, T.; Takei Sasozaki, I.; Higashiyama, Y.; Tsuchida, M. Gene correction and overexpression of TNNI3 improve impaired relaxation in engineered heart tissue model of pediatric restrictive cardiomyopathy. Dev Growth Differ. 2024, 66, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).