Submitted:

01 October 2025

Posted:

02 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

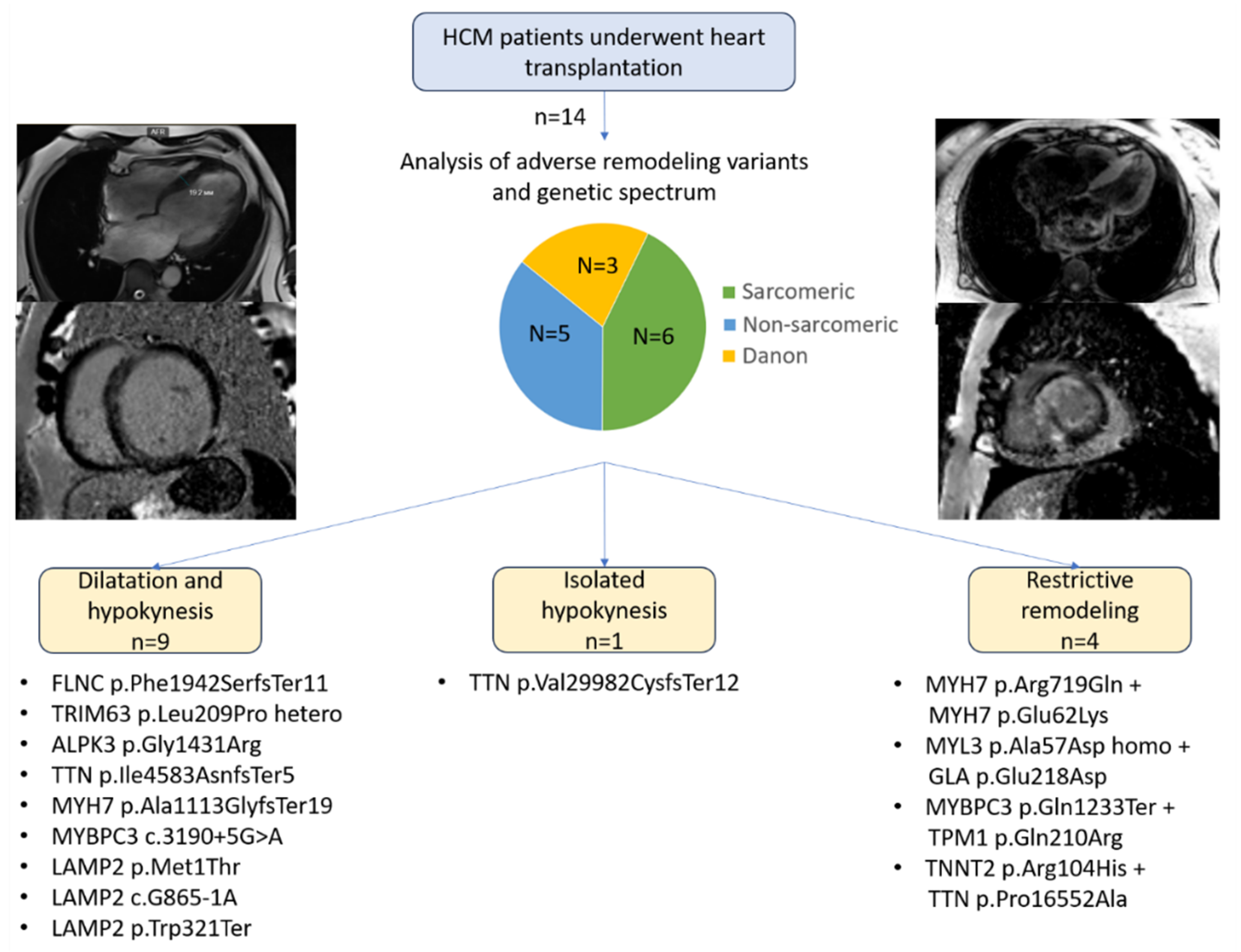

3.1. General Clinical Characteristics

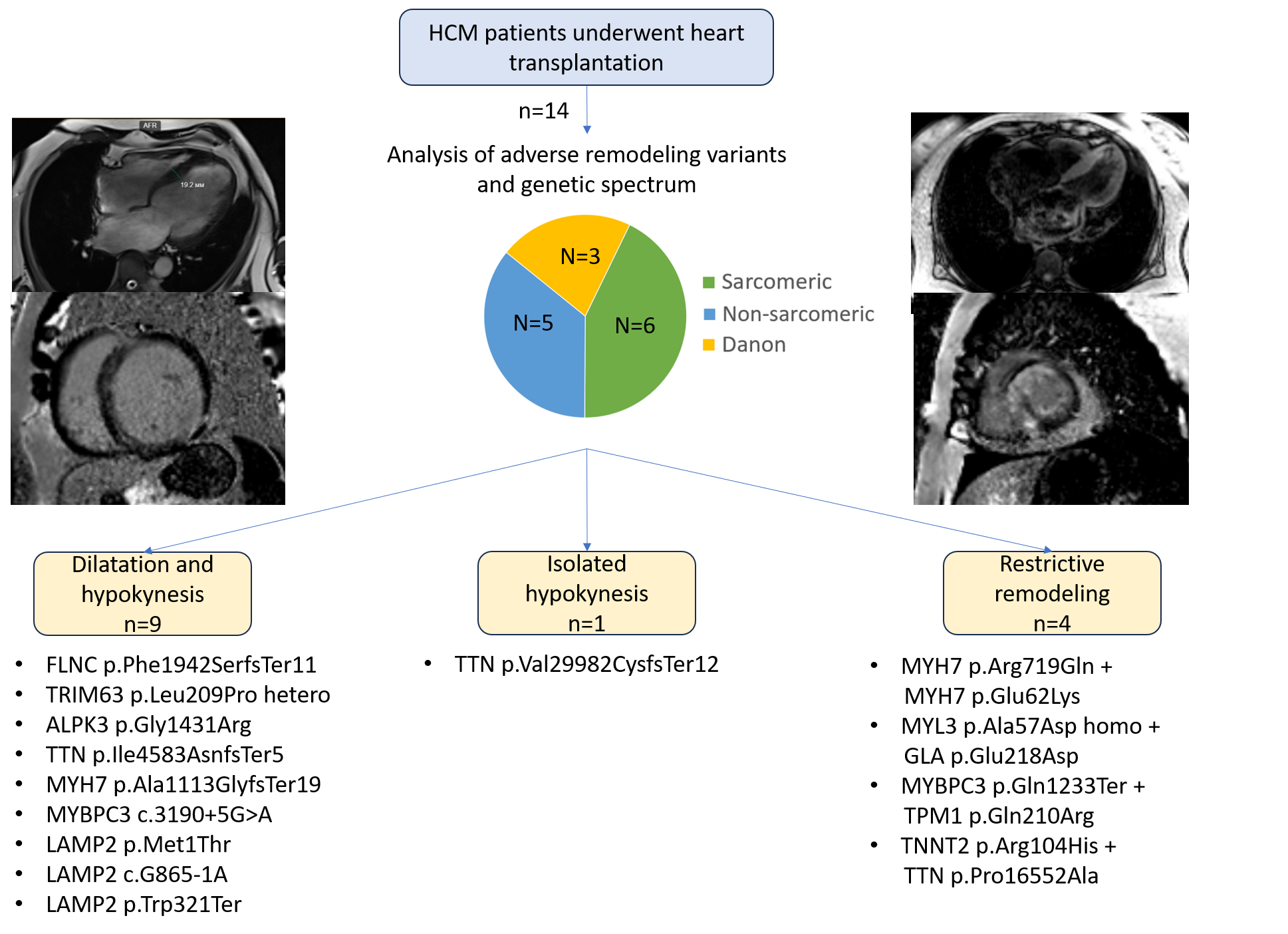

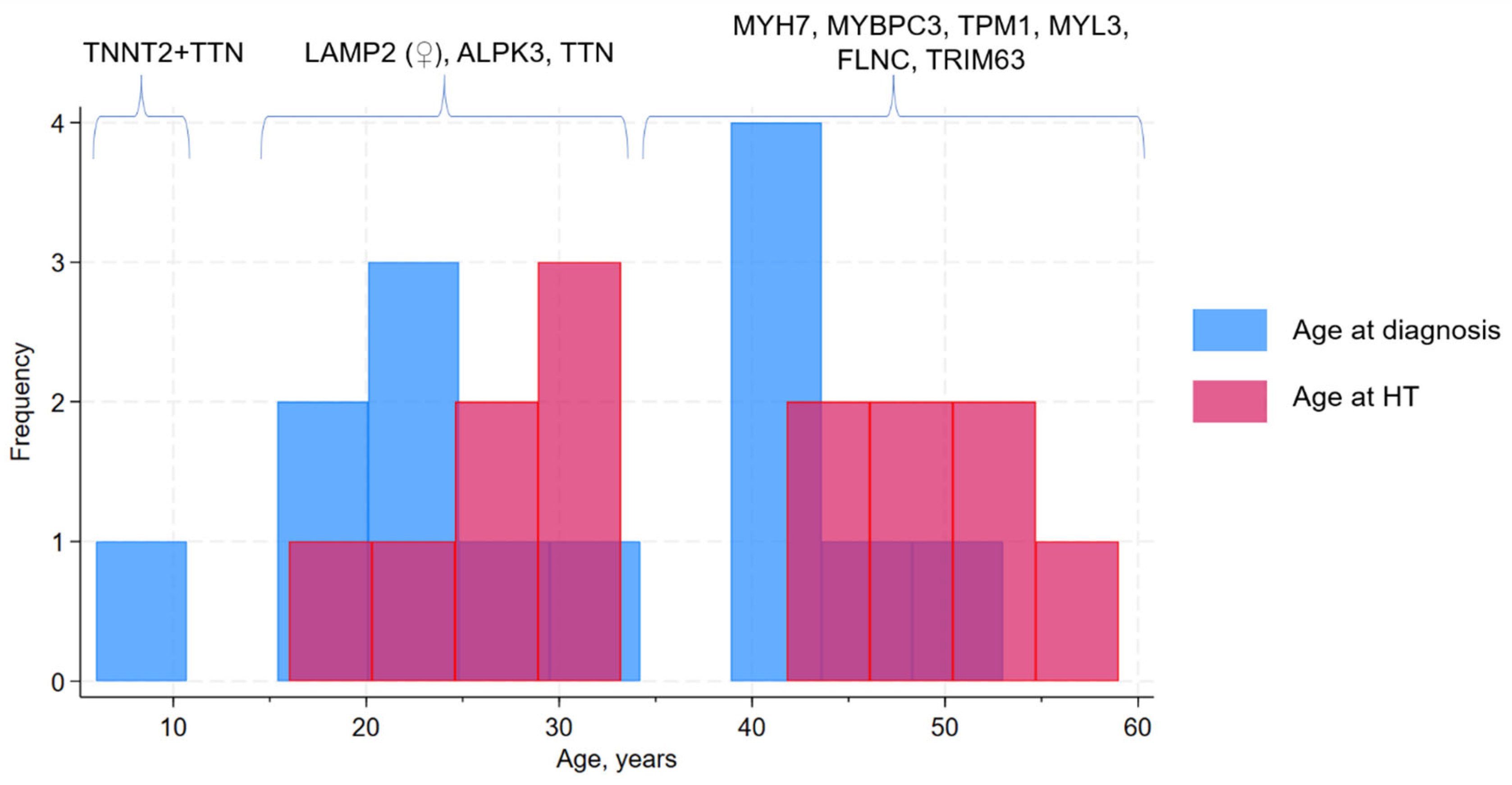

3.2. Genetic Spectrum and Association with Clinical Course and Adverse Remodeling Variants

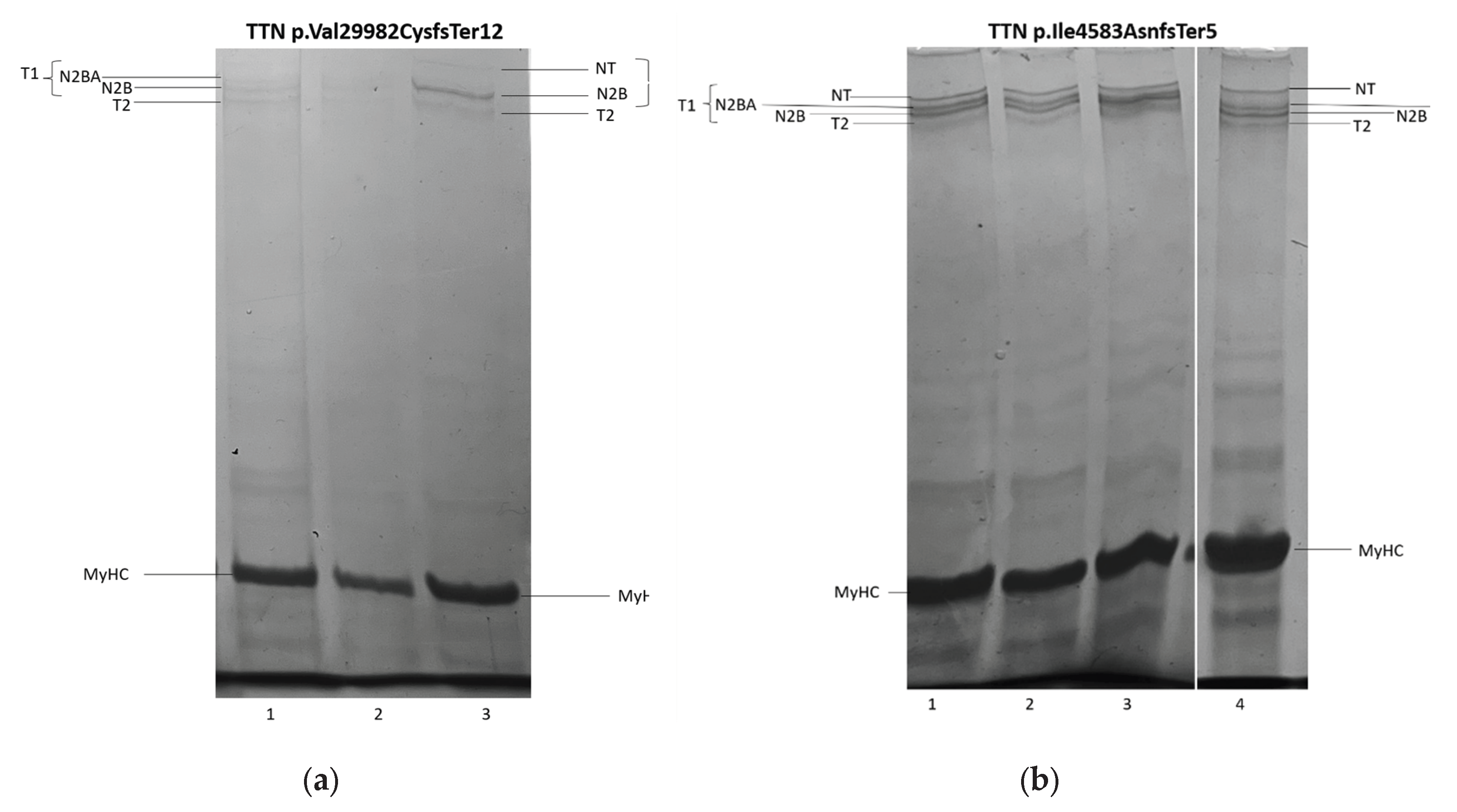

3.3. Titin Isoforms Electrophoretic Analysis.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics |

| HCM | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| HT | Heart transplantation |

| LV | Left ventricle |

| RV | Right ventricle |

Appendix A

Target 172 Genes Panel

Target 108 genes panel:

Target 39 genes panel:

References

- Arbelo E, Protonotarios A, Gimeno JR, Arbustini E, Arbelo E, Barriales-Villa R, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies: Developed by the task force on the management of cardiomyopathies of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2023;44(37):3503–626.

- Zampieri M, Salvi S, Fumagalli C, Argirò A, Zocchi C, Del Franco A, et al. Clinical scenarios of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-related mortality: Relevance of age and stage of disease at presentation. Int J Cardiol [Internet]. 2023 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Sep 30];374:65–72. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36621577/.

- Argirò A, Zampieri M, Marchi A, Cappelli F, Del Franco A, Mazzoni C, et al. Stage-specific therapy for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J Suppl [Internet]. 2023 May 1 [cited 2025 Sep 30];25(Suppl C):C155–61. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37125313/.

- Marstrand P, Han L, Day SM, Olivotto I, Ashley EA, Michels M, et al. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy with Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction: Insights from the SHaRe Registry. Circulation [Internet]. 2020 Apr 28 [cited 2025 Jul 1];141(17):1371–83. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32228044/.

- Li S, Wu B, Yin G, Song L, Jiang Y, Huang J, et al. MRI characteristics, prevalence, and outcomes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with restrictive phenotype. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging [Internet]. 2020 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jul 16];2(4):e190158. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33778596/.

- Miklin DJ, DePasquale E. Transplantation Trends in End Stage Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Over 35 Years: A UNOS Registry Analysis. J Hear Lung Transplant [Internet]. 2023 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Apr 27];42(4):S240. Available from: https://www.jhltonline.org/action/showFullText?pii=S1053249823005843.

- Georgiopoulos G, Figliozzi S, Pateras K, Nicoli F, Bampatsias D, Beltrami M, et al. Comparison of Demographic, Clinical, Biochemical, and Imaging Findings in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Prognosis: A Network Meta-Analysis. JACC Hear Fail [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jul 1];11(1):30–41. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36599547/.

- Bonaventura J, Rowin EJ, Chan RH, Chin MT, Puchnerova V, Polakova E, et al. Relationship Between Genotype Status and Clinical Outcome in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 1];13(10):e033565. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38757491/.

- Harper AR, Goel A, Grace C, Thomson KL, Petersen SE, Xu X, et al. Common genetic variants and modifiable risk factors underpin hypertrophic cardiomyopathy susceptibility and expressivity. Nat Genet 2021 532 [Internet]. 2021 Jan 25 [cited 2022 Apr 23];53(2):135–42. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41588-020-00764-0.

- Vikhlyantsev IM, Podlubnaya ZA. New titin (connectin) isoforms and their functional role in striated muscles of mammals: facts and suppositions. Biochemistry (Mosc) [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2025 Sep 30];77(13):1515–35. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23379526/.

- Yakupova EI, Abramicheva PA, Rogachevsky V V., Shishkova EA, Bocharnikov AD, Plotnikov EY, et al. Cardiac titin isoforms: Practice in interpreting results of electrophoretic analysis. Methods [Internet]. 2025 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Aug 25];236:17–25. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39993454/.

- Vikhlyantsev IM, Podlubnaya ZA. Nuances of electrophoresis study of titin/connectin. Biophys Rev [Internet]. 2017 Jun 1 [cited 2025 Sep 30];9(3):189–99. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28555301/.

- Hernandez SG, Romero L de la H, Fernández A, Peña-Peña ML, Mora-Ayestaran N, Basurte-Elorz MT, et al. Redefining the Genetic Architecture of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Role of Intermediate Effect Variants. Circulation [Internet]. 2025 Aug 13 [cited 2025 Sep 30];online ahead of print. Available from: /doi/pdf/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.125.074529?download=true.

- Hespe S, Waddell A, Asatryan B, Owens E, Thaxton C, Adduru ML, et al. Genes Associated With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Reappraisal by the ClinGen Hereditary Cardiovascular Disease Gene Curation Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet]. 2025 Feb 25 [cited 2025 Jul 23];85(7):727–40. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39971408/.

- Marston NA, Han L, Olivotto I, Day SM, Ashley EA, Michels M, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in childhood-onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J [Internet]. 2021 May 21 [cited 2025 Sep 30];42(20):1988. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8139852/.

- Ortiz-Genga MF, Cuenca S, Dal Ferro M, Zorio E, Salgado-Aranda R, Climent V, et al. Truncating FLNC Mutations Are Associated With High-Risk Dilated and Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Dec 6;68(22):2440–51.

- J Verdonschot JA, Vanhoutte EK, F Claes GR, J M Helderman-van den Enden AT, J Hoeijmakers JG, E I Hellebrekers DM, et al. A mutation update for the FLNC gene in myopathies and cardiomyopathies. | Stephane R B Heymans [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 Oct 12];41(6):1091–111. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/humu.24004.

- Sepp R, Hategan L, Csányi B, Borbás J, Tringer A, Pálinkás ED, et al. The Genetic Architecture of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Hungary: Analysis of 242 Patients with a Panel of 98 Genes. Diagnostics [Internet]. 2022 May 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];12(5):1132. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35626289/.

- Fomin A, Gärtner A, Cyganek L, Tiburcy M, Tuleta I, Wellers L, et al. Truncated titin proteins and titin haploinsufficiency are targets for functional recovery in human cardiomyopathy due to TTN mutations. Sci Transl Med [Internet]. 2021 Nov 3 [cited 2025 Jul 28];13(618):eabd3079. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34731013/.

- Yakupova EI, Vikhlyantsev IM, Lobanov MY, Galzitskaya O V., Bobylev AG. Amyloid properties of titin. Biochem [Internet]. 2017 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];82(13):1675–85. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29523065/.

- Andreeva SE, Snetkov PP, Vakhrushev YA, Piankov IA, Yaznevich OO, Bortsova MA, et al. Molecular basis of amyloid deposition in myocardium: not only ATTR and AL. Case report. Transl Med. 2023 Mar 2;9(6):26–35.

- Song S, Shi A, Lian H, Hu S, Nie Y. Filamin C in cardiomyopathy: from physiological roles to DNA variants. Heart Fail Rev [Internet]. 2022 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Jul 28];27(4):1373–85. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34535832/.

- Zheng SL, Jurgens SJ, McGurk KA, Xu X, Grace C, Theotokis PI, et al. Evaluation of polygenic scores for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the general population and across clinical settings. Nat Genet [Internet]. 2025 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Sep 30];57(3):563–71. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41588-025-02094-5.

- Ryu SW, Jeong WC, Hong GR, Cho JS, Lee SY, Kim H, et al. High prevalence of ALPK3 premature terminating variants in Korean hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients. Front Cardiovasc Med [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 30];5(11):1424551. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39036505/.

- Jorholt J, Formicheva Y, Vershinina T, Kiselev A, Muravyev A, Demchenko E, et al. Two New Cases of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Skeletal Muscle Features Associated with ALPK3 Homozygous and Compound Heterozygous Variants. Genes (Basel) [Internet]. 2020 Oct 1 [cited 2022 Jun 22];11(10):1–9. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7602582/.

- Myasnikov RP, Kulikova O V., Meshkov AN, Bukaeva AA, Kiseleva A V., Ershova AI, et al. A Splice Variant of the MYH7 Gene Is Causative in a Family with Isolated Left Ventricular Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy. Genes (Basel) [Internet]. 2022 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Aug 25];13(10):1750. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36292635/.

- Consevage MW, Salada GC, Baylen BG, Ladda RL, Rogan PK. A new missense mutation, Arg719Gln, in the β-cardiac heavy chain myosin gene of patients with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet [Internet]. 1994 Jun [cited 2025 Jul 30];3(6):1025–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7848441/.

- Huang X, Song L, Ma AQ, Gao J, Zheng W, Zhou X, et al. A malignant phenotype of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by Arg719Gln cardiac beta-myosin heavy-chain mutation in a Chinese family. Clin Chim Acta [Internet]. 2001 Aug 20 [cited 2025 Jul 30];310(2):131–9. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0009898101005381.

- Golubenko M V., Pavlyukova EN, Salakhov RR, Makeeva OA, Puzyrev K V., Glotov OS, et al. A New Leu714Arg Variant in the Converter Domain of MYH7 is Associated with a Severe Form of Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Front Biosci - Sch [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 29];16(1):1. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38538344/.

- Osborn DPS, Emrahi L, Clayton J, Tabrizi MT, Wan AYB, Maroofian R, et al. Autosomal recessive cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death associated with variants in MYL3. Genet Med [Internet]. 2021 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Jul 30];23(4):787–92. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1098360021024473?ref=pdf_download&fr=RR-2&rr=964d1fdc4e046132.

| Mean (SD) | Dilated remodeling (n=10) | Restrictive remodeling (n=4) | Overall (n=14) | |

| EF, % | at debut | 48.3 (4.7) | 61.8 (5.6) | 52.1 (4.0) |

| at terminal stage | 22.3 (2.2) | 44.5 (2.) | 28.6 (3.2) | |

| Wall thicknes, mm | at debut | 18.6 (0.9) | 18 (1.60) | 18.5 (0.8) |

| at terminal stage | 12.7 (0.9) | 17 (1.1) | 13.9 (0.9) | |

| iEDV, ml/m3 | at debut | 90.1 (11.2) | 51.0 (7.2) | 78.9 (9.5) |

| at terminal stage | 140.8 (17.1) | 49.0 (10.0) | 114.6 (16.) | |

| iLAV, ml/m3 | at debut | 55.7 (6.0) | 56.3 (7.4) | 55.9 (4.6) |

| at terminal stage | 70.9 (6.7) | 90.8 (8.6) | 76.6 (5.8) | |

| RV hypertrophy | 5 (50%) | 4 (100%) | 9 (64%) | |

| LV hypertrabeculation | 6 (60%) | 1 (25%) | 7 (50%) | |

| Female sex | 6 (60%) | 3 (75) | 9 (64%) | |

| AF | 6 (60%) | 3 (75%) | 9 (64%) | |

| Hypertension | 3 (30%) | 0 | 3 (21%) | |

| Septal myoectomy | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Diabetes | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Liver fibrosis | 0 | 2 (50%) | 2 (14%) | |

| Precapillary pulmonary hypertension | 2 (20%) | 2 (75%) | 4 (29%) | |

| NT-proBNP, ng/ml | 6509.2 (1682.0) | 4444.5 (741.0) | 5873.9 (1193.2) | |

| Time from debut to HT | 6.9 (0.8) | 10 (4.2) | 7.8 (1.3) | |

| Age at debut | 31.1 (4.2) | 29.5 (8.3) | 30.6 (3.6) | |

| Age at HT | 38.0 (4.1) | 39.5 (8.0) | 38.4 (3.5) | |

| Patient | Gene | GRCh38 position, cDNA | Amino acid substitution | Variant type | Rs, MAF% | Zygosity | ACMG pathogentity | Gene panel |

| 1 | FLNC | 7:128851605, c.5823delC | p.Phe1942SerfsTer11 | Inframe deletion | - | hetero | LP | 39 |

| 2 | TRIM63 | Chr 1:26058595, c.T626C | p.Leu209Pro | missense | rs1553145730 0,00007 |

hetero | VUS | 39 |

| 3 | ALPK3 | Chr15:8486279, c.G4291A | p.Gly1431Arg | Missense | rs750258262 0,001 |

homo | LP | 172 |

| 4 | TTN | Chr2: 178552954-GACAdel: c.89943 89946del | p.Val29982CysfsTer12 | Inframe deletion | - | hetero | LP | 172 |

| Chr2: 178616815: c.G48074A | p.Ser16025Asn | Missense | rs727504720 0,00007 |

hetero | VUS | |||

| 5 | TTN | Chr2: 178748649: c.13748 13751delTTTA | p.Ile4583AsnfsTer5 | Frameshift | rs1460696675 0,002 |

hetero | LP | 172 |

| 6 | MYH7 | Chr14:23420234insC c.3337dupl |

p.Ala1113GlyfsTer19 | Splice-region+ frameshift | hetero | LP | 108 | |

| 7 | MYBPC3 | Сhr11: 47333552: c.3190+5G>A | - | Splice-region | rs587782958 0,0006 |

hetero | P | 39 |

| 8 | LAMP2 | ChrX: 20469168: c.T2C | p.Met1Thr | Start-loss | - | hetero | LP | 39 |

| 9 | LAMP2 | ChrX: 120442663: c.G865-1A | - | Splice-region | rs397516752 | hetero | P | 172 |

| 10 | LAMP2 | СhrX: 120441861: c.G962A | p.Trp321Ter | Nonsense | rs1060502306 | hetero | P | 39 |

| 11 | MYH7 | Сhr14: 23425970: c.G2156A | p.Arg719Gln | Missense | rs121913641 | hetero | P | 39 |

| Сhr14: 23433549: c.G184A | p.Glu62Lys | Missense | rs727504416 0,0005 |

hetero | VUS | |||

| 12 | MYL3 | Chr3: 46860813: c.C170A | p.Ala57Asp | Missense | rs139794067 0,01 |

homo | LP | 39 |

| GLA | ChrX: 101398932: c.A654T | p.Glu218Asp | Missense | - | hetero | VUS | ||

| 13 | MYBPC3 | Chr11: 47332189: c.C3697T | p.Gln1233Ter | Nonsense | rs397516037 0,0008 |

hetero | P | 172 |

| TPM1 | Chr15:63061778: c.A629G | p.Gln210Arg | Missense | rs777139450 | hetero | LP | ||

| 14 | TNNT2 | Chr1:201365291: c.G311GA | p.Arg104His | Missense | rs397516457 | hetero | P | 172? |

| TTN | Chr2:178613067: c.C49654G | p.Pro16552Ala | Missense | - | hetero | VUS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).