1. Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common genetic heart disease, characterized by left ventricle (LV) hypertrophy in the absence of abnormal loading conditions [

1]. Its clinical course ranges from mildly symptomatic longevity to sudden cardiac death (SCD), advanced heart failure (HF), or embolic stroke. In approximately 50% of cases, HCM is caused by (likely) pathogenic variants (previously mutations) in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins. Sarcomeres, the basic contractile units of cardiomyocytes, facilitate contraction through cyclic interactions between the thick filament protein myosin and thin filament protein actin. This process is finely regulated by the troponin-tropomyosin complex, a component of the thin filament. Calcium binding to troponin triggers conformational changes in both troponin and tropomyosin which expose binding sites on actin, thereby enabling actin-myosin cross-bridge formation and subsequent muscle contraction [

2].

The most frequently mutated genes in HCM (80% of genotype-positive cases) encode thick filament proteins, including β-myosin heavy chain (

MYH7) and myosin-binding protein C (

MYBPC3) [

3]. A smaller proportion of patients (an average of 6% from submitted to genetic testing) carry (likely) pathogenic variants in thin filament genes, such as alpha-actin (

ACTC1), troponin C (

TNNC1), troponin I (

TNNI3), troponin T (

TNNT2), and alpha-tropomyosin (

TPM1) [

4].

Mutations in β-cardiac myosin lead to hypercontractility of the heart [

5], a primary defect in HCM that precedes LV hypertrophy [

6]. This knowledge has guided the development of cardiac myosin inhibitors, small molecules that reduce sarcomere contractility and mitigate HCM features [

7,

8]. While LV hypercontractility is a shared hallmark of HCM, the underlying mechanisms differ between thick and thin filament mutations [

9]. Thick filament HCM is primarily associated with increased ATPase activity and an elevated disordered relaxed state of myosin [

5]. Conversely, thin filament mutations initially disrupt calcium regulation: increased Ca

2+ buffering and altered handling contribute to pathogenesis via Ca

2+ -dependent signaling pathways [

10].

Some studies have described distinct clinical presentations and outcomes in HCM patients with thin filament mutations. However, these findings remain controversial, and further prospective research is needed to better understand this rare HCM subgroup.

The study aimed to evaluate the clinical features and prospective outcomes of patients with HCM caused by (likely) pathogenic variants in thin filament sarcomeric genes, in comparison to those with thick filament HCM. Additionally, results were interpreted in the context of previous studies.

2. Materials and Methods

Sarcomere-positive HCM patients from an ongoing single-center prospective study (protocol previously described in [

11] were enrolled. The study included carriers of single (likely) pathogenic variants. The diagnosis of HCM was established based on imaging criteria, defined as increased LV wall thickness ≥15 mm (≥13 mm for relatives) not solely explained by loading conditions. Carriers of variants in

ACTC1, TNNC1, TNNI3, TNNT2, and

TPM1 (thin filament group) were compared with those harboring variants in

MYBPC3, MYH7, MYL2, and

MYL3 (thick filament group) regarding baseline characteristics, treatment approaches, and clinical outcomes. The outcomes analyzed were the following: (1) all-cause mortality; (2) malignant arrhythmic events, including SCD, successful resuscitation and appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shocks; (3) stroke (fatal and non-fatal); (4) HF outcome, including new HF progression and death from HF; HF progression was defined as hospitalizations requiring parenteral infusion of diuretics and/or inotropes, transition to hypokinetic HCM with a decrease in LV ejection fraction below 50%, or first occurrence of New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III/IV. The frequency of ICD insertion and septal reduction therapy was assessed over a single time period, including past history and follow-up. Additionally, the thin filament group was evaluated in the context of previously reported data on thin filament HCM from the literature.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as the median with interquartile range [25th–75th percentile] for non-normally distributed data. Comparisons were made using the Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate. Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages and were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Survival analyses were conducted using Cox proportional hazards regression. Survival curves and times were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. All p-values were two-tailed and considered significant at <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0.

3. Results

Of the 230 genotyped HCM patients, 88 (39%) were sarcomere-positive. Six patients with multiple (likely) pathogenic variants were excluded. Of the remaining 82 patients with single sarcomeric variants, 15 (18%) carried nine unique variants in thin filament genes (one in

ACTC1, two in

TNNI3, two in

TNNT2, one in

TNNC1, and nine in

TPM1) and 67 (82%) carried 45 unique variants in thick filament genes (41 in

MYBPC3, 23 in

MYH7, and three in

MYL2) (

Supplementary Table S1).

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Patients with thin filament HCM (n = 15) were diagnosed and enrolled in the study at a median age of 44 and 49 years, respectively; probands comprised 80% of the group; half of the group presented with HCM-associated symptoms such as dyspnoea (n = 7, 47%), palpitations (n = 4, 27%), and chest pain (n = 4, 27%); two (13%) had nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) on Holter monitoring; of the probands (n = 12), seven had familial HCM, and two had SCD in families. All baseline characteristics, including imaging and electrocardiographic data, and comparisons between thin and thick filament HCM groups are shown in

Table 1. All participants were Caucasian; 88% were of Eastern Slavic origin.

Patients with thin filament HCM exhibited significantly lower maximal LV wall thickness values, as measured by both echocardiography (p = 0.024) and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) (p = 0.006). They also had smaller indexed LV end-diastolic volumes on CMR (p = 0.041) and a lower 5-year SCD risk score (p = 0.007). Although patients in the thick filament group were more frequently indicated for ICD insertion based on an SCD risk score > 6%, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.06). No other differences in baseline characteristics were observed.

3.2. Treatment and Follow-Up

Follow-up duration was similar for thin and thick filament groups (4.7 ± 2.3 vs. 4.4 ± 3.4 years;

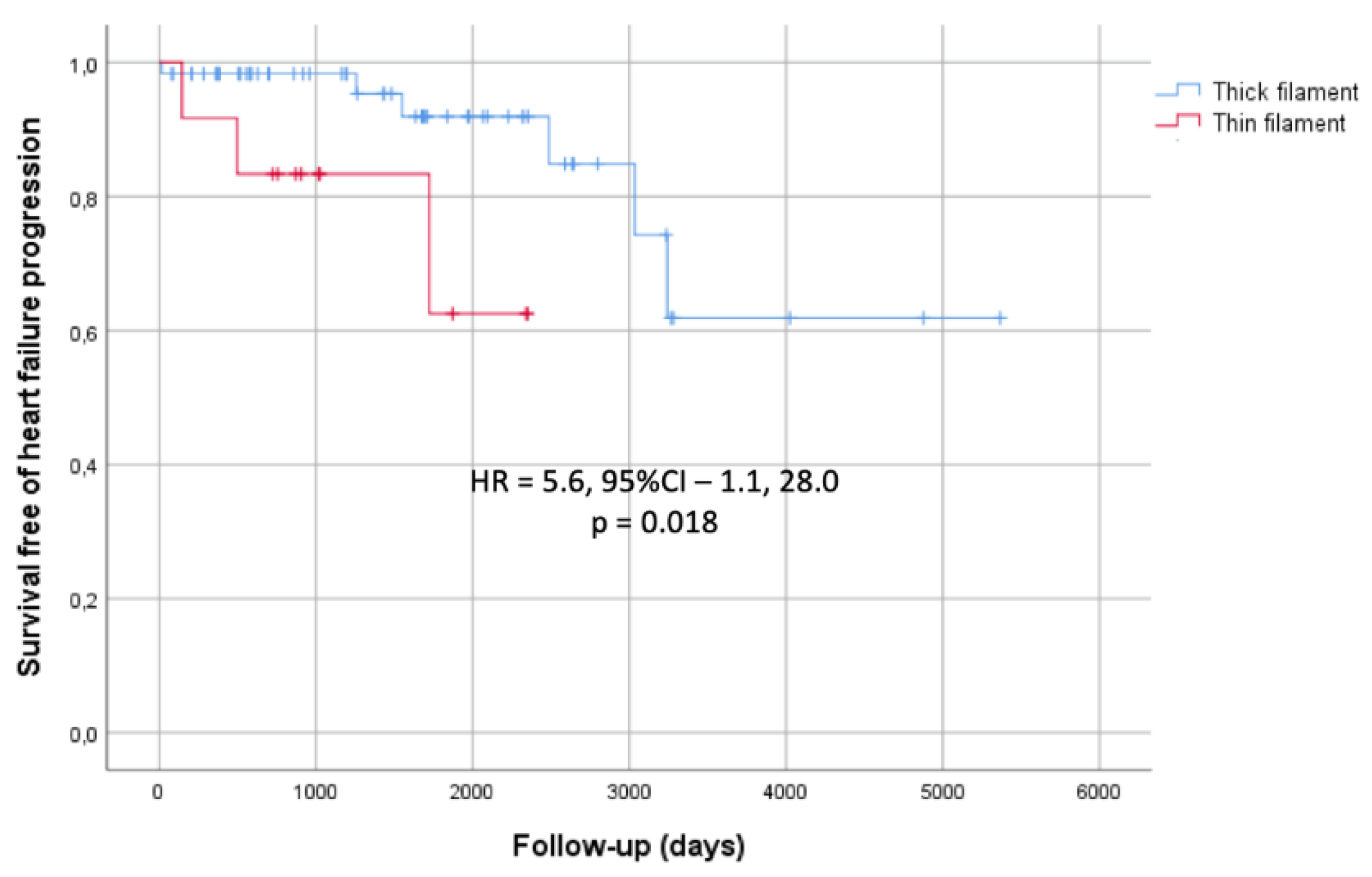

p = 0.79). Of 82 patients, two died due to HF (both from thick filament group), one had a non-fatal stroke (from thick filament group), and nine progressed to severe HF (three from thin filament group and five from thick filament group). None of the patients experienced malignant arrhythmic events. When comparing the thin and thick filament groups, there were no differences in outcomes such as all-cause mortality, malignant arrhythmic events, or stroke. However, thin filament HCM patients exhibited more rapid progression to advanced HF, with significance observed among probands (

Figure 1). The predicted mean survival time until HF progression was 5.2 ± 0.64 years in the thin filament group compared to 11.8 ± 1.04 years in the thick filament group (p = 0.018). They also underwent septal reduction therapy less often. Only one patient (7%) in the thin filament group had alcohol septal ablation, compared to 12 (17%) in the thick filament group who underwent septal myectomy (

p = 0.025). Nine patients in thick filament group (12%) and none in thin filament group received an ICD; the difference was not significant (p = 0.18).

3.3. Comparison Thin Filament HCM Patients Across Different Studies

Data on baseline characteristics and outcomes from our study, the adult studies by Coppini et al. (2014) and van Driest et al. (2003), and the pediatric study by Norrish et al. (2024) are shown in

Table 2.

The predominant genotype in our cohort was TPM1, whereas in all other studies it was TNNT2. Other parameters in our group were in close agreement with the findings from adult cohorts reported by Coppini et al. and van Driest et al., including a low prevalence of thin filament variants among genotyped patients (approximately 6%), age at diagnosis 40-45 years, LV wall thickness < 20mm, prevalence of LV outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) at an average of 30%, and a significant prevalence of late gadolinium enhancement (> 80%). In our cohort, 20% of patients were relatives, whereas two other adult cohorts included only unrelated individuals. In contrast, the majority of the pediatric population (two thirds) consisted of relatives. Compared with adult cohorts, pediatric patients predictably had a higher prevalence of familial HCM, lower LV wall thickness values, and a significantly lower incidence of LVOTO.

Septal reduction therapy was performed in a minority of thin filament HCM patients in our cohort (7%) and in Coppini’s study (14%). This contrasts with the findings from Driest et al., who reported high rates of myectomy in both thin filament (32%) and non-thin filament (41%) groups, which they attributed to a surgical referral bias. In the pediatric population, septal reduction therapy was performed at the lowest rate (5%).

The follow-up period across studies was comparable averaged nearly five years. In all four studies, major adverse events such as malignant arrhythmias, stroke, or death were rare or absent among thin filament patients, with no significant differences compared to the thick filament groups. The proportion of patients who developed severe HF symptoms was significant and comparable between our cohort (20%) and Coppini’s (15%). In addition, a notable 18% of patients in Coppini’s cohort completed the study with severe LV dysfunction, defined as an LV ejection fraction below 50%. In contrast, no pediatric patients experienced HF events. Interestingly, a substantially higher proportion of pediatric patients (62%) underwent ICD insertion compared to adult cohorts (0-24%).

4. Discussion

Studies on HCM associated with thin filament gene variants are limited and mainly consist of case series focusing on individual genes [

15,

16]. Beyond our work, only three studies have analyzed thin filament HCM as a group without gene preselection: Coppini et al. [

12], van Driest et al. [

13], and Norrish et al. [

14]. Thin filament variants are found in approximately 6% of genotyped adult HCM cohorts, a consistent finding across studies, including our own. This low prevalence makes the study of this subgroup challenging.

Our study, along with Coppini’s, demonstrated that LV wall thickness is lower in thin filament compared to thick filament HCM. In the pediatric cohort, baseline differences in LV wall thickness were not significant. Although van Driest et al. reported no statistical significances in any of the baseline characteristics, the mean LV wall thickness in the thin filament group was below 20 mm, compared to over 21 mm in the rest of the cohort. These findings are consistent with earlier studies [

17]. Collectively, this evidence indicates that in adults, the ‘thinner’ phenotype is strongly associated with the thin filament genotype.

Septal reduction therapy was less common in the thin filament group in both our and Coppini’s studies. Coppini et al. attributed this to the lower prevalence of LVOTO, whereas we associated it with a thinner septum, potentially affecting surgical decisions. The prevalence of LVOTO in thin filament HCM ranged from 5% in the pediatric population to 42% in van Driest’s study. Notably, only Coppini et al. reported a significant difference in LVOTO prevalence between thin and thick filament HCM groups (19% vs. 34%). These findings suggest that the presence of LVOTO is unlikely to be directly influenced by genotype.

The ‘thinner’ myocardium accounts for the lower 5-year SCD risk scores in our thin filament group, as the other parameters in the calculator were similar to the thick filament group. None of our thin filament patients developed malignant arrhythmias or SCD during follow-up, none had a 5-year SCD risk score >6% and received an ICD. One subject had a family history of multiple SCD, which is an indication for an ICD according to American guidelines. The rate of malignant arrhythmic events was similar between thin and thick filament groups, which is consistent with Coppini’s findings. In the pediatric study, children with thin filament variants more frequently experienced NSVT and underwent ICD insertion compared to those with thick filament variants. However, similar to adult studies, malignant arrhythmic events did not differ significantly. The authors suggested that the higher ICD insertion rate in thin filament children might partially due to their older age at the last follow-up. While early studies on

TNNT2- and

TPM1-associated HCM reported a high SCD risk [

17], accumulating evidence suggests that overall arrhythmic risk in thin filament HCM is comparable to that in thick filament HCM. Additional factors, including certain malignant mutations, should be considered to improve SCD risk prediction.

In our study and Coppini’s, patients with thin filament HCM progressed more rapidly to advanced HF. Myocardial fibrosis, a key contributor to HF, was frequently observed on CMR in both thin and thick filament groups across both studies. While we did not assess fibrosis extent, Coppini’s study found significantly greater fibrous tissue in thin filament patients, potentially explaining these findings. The pediatric study showed no difference in HF outcomes between thin and thick filament patients, likely due to the relatively short follow-up. In child-onset HCM, ventricular arrhythmias are the most common events during the first decade after baseline visit, while HF predominates by the end of the second decade of follow-up [

18].

A recent meta-analysis by Saul et al., including 177 thin filament HCM patients (two-thirds were relatives) from 21 studies, reported high HF morbidity and mortality, which is consistent with our conclusions. The study also shows a trend towards an increased risk of SCD and ventricular arrhythmias [

19], which is opposite to our and Coppini’s findings. One explanation may be that the meta-analysis comprised both pediatric and adult onset cases. It is also important to note, that most of the included studies were case reports with potential bias towards severe phenotypes, and not all provided specific time frames or explicit confirmation of the absence of certain outcomes in patients, which may have led to under- or overestimation of prognosis and the effects of interventions.

In summary, our study supports the evidence that thin filament HCM is characterized by a thinner phenotype and a worse prognosis for HF in adults. In some cases, this may delay diagnosis and calls for more careful monitoring of HF symptoms in these patients. Different conclusions regarding the arrhythmogenicity of thin filament mutations do not allow the use of this genotype alone in the individual prognosis for SCD, and new additional biomarkers are needed. Finally, recent experiments have shown that while the first-in-class myosin inhibitor mavacamten is known to reverse the increased contractility caused by thick filament mutations, its effect on HCM thin filament mutations through decrease of calcium sensitivity only partially rescues the contractile cellular phenotype and, in some cases, may exacerbate the effect of the mutation [

20]. Therefore, the new therapeutics should be investigated in relation to the genotype status of the patients, including whether they belong to thin or thick filament HCM.

5. Conclusions

Patients with thin filament HCM face an elevated risk of rapid HF progression despite their ‘thinner’ phenotype. The genetic profile of HCM patients should be considered in further diagnostic and treatment response studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Sarcomeric Gene Variants Identified in the Study Group

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation—O.S.C.; resources, T.N.B. and D.A.Z.; data curation, writing—review and editing, D.A.Z.; project administration, T.N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (grant No. 20-15-00353).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the Ethics Committee of City Clinical Hospital #17, Moscow (protocol 5, 22 MAY 2009) and confirmed for extension (protocol #9, 04 NOV 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the doctors the Cardiology and Internal medicine Departments of the City Clinical Hospital #17 (Moscow, Russia), who helped with the examination and follow-up of the patients

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Elliott, P.M.; Anastasakis, A.; Borger, M.A.; Borggrefe, M.; Cecchi, F.; Charron, P.; Hagege, A.A.; Lafont, A.; Limongelli, G.; Mahrholdt, H.; McKenna, W.J.; Mogensen, J.; Nihoyannopoulos, P.; Nistri, S.; Pieper, P.G.; Pieske, B.; Rapezzi, C.; Rutten, F.H.; Tillmanns, C.; Watkins, H. 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2014, 35, 2733–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Namba, K.; Fujii, T. Cardiac muscle thin filament structures reveal calcium regulatory mechanism. Nat Commun 2020, 11(1):153. [CrossRef]

- Christian, S.; Cirino, A.; Hansen, B.; Harris, S.; Murad, A.M.; Natoli, J.L.; Malinowski, J.; Kelly, M.A. Diagnostic validity and clinical utility of genetic testing for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2022, 9, e001815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, L.R.; Rahman, M.S.; Elliott, P.M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of genotype–phenotype associations in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by sarcomeric protein mutations. Heart 2013, 99(24):1800-1811. [CrossRef]

- Spudich, J.A. Three perspectives on the molecular basis of hypercontractility caused by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol 2019, 471(5):701-717. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.Y.; Sweitzer, N.K.; McDonough, B.; Maron, B.J.; Casey, S.A.; Seidman, J.G.; Seidman, C.E.; Solomon, S.D. Assessment of Diastolic Function With Doppler Tissue Imaging to Predict Genotype in Preclinical Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2002, 105(25):2992-2997. [CrossRef]

- Green, E. M.; Wakimoto, H.; Anderson, R. L.; Evanchik, M. J.; Gorham, J. M.; Harrison, B. C.; Henze, M.; Kawas, R.; Oslob, J. D.; Rodriguez, H. M.; Song, Y.; Wan, W.; Leinwand, L. A.; Spudich, J. A.; McDowell, R. S.; Seidman, J. G.; & Seidman, C. E. A small-molecule inhibitor of sarcomere contractility suppresses hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Science 2016, 351(6273):617-621. [CrossRef]

- Olivotto, I.; Oreziak, A.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Abraham, T. P.; Masri, A.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Saberi, S.; Lakdawala, N. K.; Wheeler, M. T.; Owens, A.; Kubanek, M.; Wojakowski, W.; Jensen, M. K.; Gimeno-Blanes, J.; Afshar, K.; Myers, J.; Hegde, S. M.; Solomon, S. D.; Sehnert, A. J.; Zhang, D.; Li, W.; Bhattacharya, M.; Ho, C.; Jacoby, D.; EXPLORER-HCM study investigators. Mavacamten for treatment of symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (EXPLORER-HCM): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2020, 396(10253):759-769. [CrossRef]

- Keyt, L.K.; Duran, J.M.; Bui, Q.M.; Chen, C.; Miyamoto, M.I.; Enciso, J.S.; Tardiff, J.C.; Adler, E.D. Thin filament cardiomyopathies: A review of genetics, disease mechanisms, and emerging therapeutics. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9:972301. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.; Liu, X.; Sparrow. A.; Patel, S.; Zhang, Y-H.; Casadei, B.; Watkins, H.; Redwood, C. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations increase myofilament Ca2+ buffering, alter intracellular Ca2+ handling, and stimulate Ca2+-dependent signaling. J Biol Chem 2018, 293(27):10487-10499. [CrossRef]

- Chumakova, O.S.; Baklanova, T.N.; Milovanova, N.V.; Zateyshchikov, D.A. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Underrepresented Populations: Clinical and Genetic Landscape Based on a Russian Single-Center Cohort Study. Genes 2023, 14(11):2042. [CrossRef]

- Coppini, R.; Ho, C. Y.; Ashley, E.; Day, S.; Ferrantini, C.; Girolami, F.; Tomberli, B.; Bardi, S.; Torricelli, F.; Cecchi, F.; Mugelli, A.; Poggesi, C.; Tardiff, J.; Olivotto, I. Clinical Phenotype and Outcome of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Associated With Thin-Filament Gene Mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014, 64(24):2589-2600. [CrossRef]

- Van Driest, S.L.; Ellsworth, E.G.; Ommen, S.R.; Tajik, A.J.; Gersh, B.J.; Ackerman, M.J. Prevalence and Spectrum of Thin Filament Mutations in an Outpatient Referral Population With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2003; 108(4):445-451. [CrossRef]

- Norrish, G.; Gasparini, M.; Field, E.; Cervi, E.; Kaski, J.P. Childhood-onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by thin-filament sarcomeric variants. J Med Genet Published online January 31, 2024:jmg-2023-109684. [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, M.J.; VanDriest, S.L.; Ommen, S.R.; Will, M.L.; Nishimura, R.A.; Tajik, A.J.; Gersh, B.J. Prevalence and age-dependence of malignant mutations in the beta-myosin heavy chain and troponin t genes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002, 39(12):2042-2048. [CrossRef]

- Pasquale, F.; Syrris, P.; Kaski, J.P.; Mogensen, J.; McKenna, W.J.; Elliott, P. Long-Term Outcomes in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Caused by Mutations in the Cardiac Troponin T Gene. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2012, 5(1):10-17. [CrossRef]

- Watkins, H.; McKenna, W. J.; Thierfelder, L.; Suk, H. J.; Anan, R.; O’Donoghue, A.; Spirito, P.; Matsumori, A.; Moravec, C. S.; Seidman, J. G. Mutations in the Genes for Cardiac Troponin T and α-Tropomyosin in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 1995, 332(16):1058-1065. [CrossRef]

- Marston, N. A.; Han, L.; Olivotto, I.; Day, S. M.; Ashley, E. A.; Michels, M.; Pereira, A. C.; Ingles, J.; Semsarian, C.; Jacoby, D.; Colan, S. D.; Rossano, J. W.; Wittekind, S. G.; Ware, J. S.; Saberi, S.; Helms, A. S.; Ho, C. Y. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in childhood-onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2021, 42(20):1988-1996. [CrossRef]

- Saul, T.; Bui, Q.M.; Argiro, A.; Keyt, L.; Olivotto, I.; Adler, E. Natural history and clinical outcomes of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from thin filament mutations. ESC Heart Fail Published online May 21, 2024:ehf2.14848. [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, A.J.; Watkins, H.; Daniels, M.J.; Redwood, C.; Robinson, P. Mavacamten rescues increased myofilament calcium sensitivity and dysregulation of Ca2+ flux caused by thin filament hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2020, 318(3):H715-H722. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).