1. Introduction

Myocardial disease represents one of the most promising and dynamic areas of modern cardiology. Of even greater interest is the combination of different myocardial diseases in a single patient, with particular emphasis on the combination of cardiomyopathies with myocarditis. Over the past 15 years, the frequency of the search term "cardiomyopathy and myocarditis" in international bibliographic databases has increased exponentially.

The increased susceptibility of genetically altered myocardium to myocarditis is a topic of active discussion in the scientific community. Furthermore, there is evidence that myocarditis may act as a trigger for the initiation of an abnormal genetic programme [

1,

2,

3,

4]. It was demonstrated that children with acute myocarditis have significantly more frequent mutations in genes associated with various cardiomyopathies

BAG3. DSP, PKP2. RYR2. SCN5A and

TNNI3 [

5]. There is evidence that patients with cardiomyopathies caused by mutations in the DSP gene, as well as

LAMA4 and

MyBPC3, have signs of active myocarditis, including elevated cardiac-specific enzymes, typical inflammatory changes on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET-CT), and on morphological examination [

6,

7]. In the European Cardiomyopathy and Myocarditis - Long Term (CMY-LT) registry, a combination of cardiomyopathy and myocarditis was identified in 128 individuals (3.2%), although this subgroup was not subjected to separate analysis.

It has been demonstrated that in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), histological examination reveals active myocarditis in more than 40% of patients [

8,

9]. A number of researchers have hypothesised that myocarditis represents a form of 'hot phase' in the development of this cardiomyopathy [

10,

11,

12]. Furthermore, the death of cardiomyocytes as a consequence of apoptosis, accompanied by the presentation of their antigens (Ag) during the natural course of ARVC, may give rise to the development of secondary inflammation in the myocardium. [

13].

Data on myocarditis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) are limited. A study was conducted by a group of Italian scientists led by A. Frustaci in 2007, which yielded the result that the frequency of myocarditis in HCM was 23.5%. It was observed that among these patients, there were no clinically stable patients, which serves to emphasise the contribution of myocarditis to the worsening of the clinical course of HCM.

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) can be a consequence of myocarditis, but primary, genetic forms of DCM are caused by mutations in a wide range of genes. In such cases, the role of superimposed myocarditis in the course of the disease may be significant. It has been demonstrated that in DCM resulting from mutations in the

DMD and

DYSF genes, the myocardium is susceptible to infection by Coxsackie virus due to disruption of the cardiomyocyte membrane structure, which facilitates rapid viral spread within the myocardium [

14,

15]. It has been documented that cases of viral myocarditis in patients with Duchenne myopathy and DCM have resulted in a rapid progression of systolic dysfunction and patient mortality [

16].

Left ventricular non-compaction (LVNC) was included in the classification of cardiomyopathies only in 2008 [

17]. This condition is also a favourable background for myocarditis of viral etiology (cardiotropic viruses [

18,

19], paramyxovirus [

20], SARS-CoV-2 [

21]). In all described clinical cases, the accession of myocarditis led to decompensation of chronic heart failure (CHF). There is also evidence that acute myocarditis in a patient with LVNC provoked the development of continuously recurrent ventricular tachycardia (VT) [

22].

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is the least prevalent of the various forms of cardiomyopathy. Nevertheless, there are also reports of RCM occurring in conjunction with myocarditis. For example, endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) results from 286 patients with the RCM phenotype demonstrated the presence of myocarditis in 19 cases, representing 6.6% of the total [

23]. Another study demonstrated that 7% of patients with morphologically confirmed myocarditis exhibited evidence of RCM on echocardiography (EchoCG) [

24]. Amyloidosis has been identified as the most prevalent underlying cause of secondary RCM. Concurrently, amyloid can exert a direct toxic effect on cardiomyocytes and function as a substrate for the development of immune-mediated secondary inflammation. The presence of concomitant myocarditis in patients with amyloidosis has been demonstrated to significantly worsen the prognosis [

25].

It is evident that the coexistence of myocarditis and diverse forms of cardiomyopathy is not an uncommon occurrence. However, the majority of existing literature in this field is limited to the description of individual clinical cases without any information on the ethiopathogenetic management of myocarditis. A comprehensive approach to the diagnosis and treatment of myocarditis in patients with cardiomyopathies has yet to be established. The characteristics of the clinical manifestations of myocarditis and their influence on prognosis, depending on the specific type of cardiomyopathy, remain to be investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

Aim: to investigate the prevalence and clinical implications of myocarditis in individuals with cardiomyopathies, to assess the efficacy of myocarditis treatment in patients with cardiomyopathies.

Patients with primary genetically determined cardiomyopathies aged 18 years or over who provided written informed consent to participate in the study were included. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Local Ethics Committee of Sechenov University (protocol code 10-22, dated 19 May 2022).

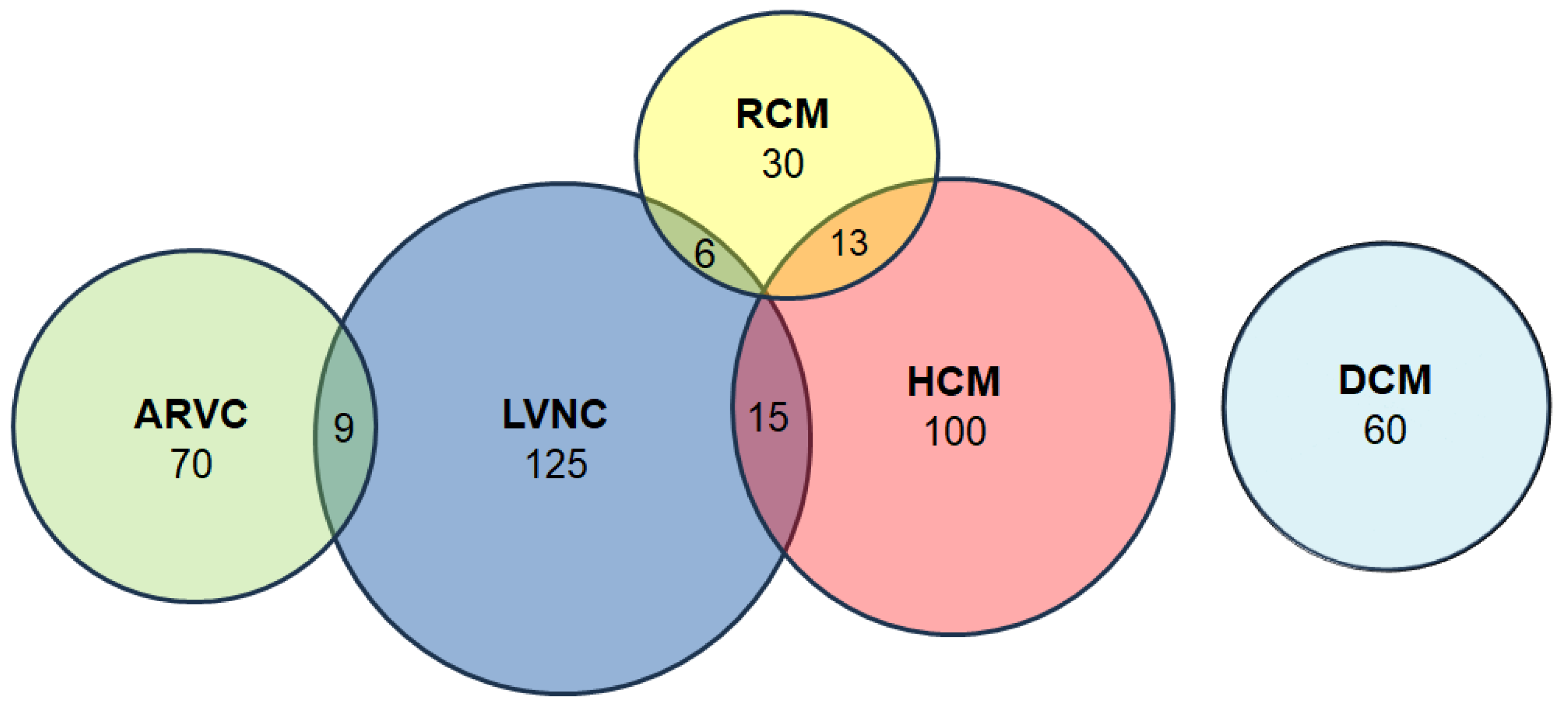

A total of 342 patients with primary cardiomyopathies were included in the study. The cohort comprised 125 patients with LVNC, 100 with primary myocardial hypertrophy syndrome, 70 with ARVC, 60 with DCM and 30 with RCM (

Figure 1). The study cohort also included patients with a range of mixed phenotypes: HCM + LVNC (n = 15), LVNC + ARVC (n = 9), LVNC + RCM (n = 6), HCM + RCM (n = 13). The patients were enrolled in the registry between 2008 and 2023 at an expert centre – the V.N. Vinogradov Faculty Therapeutic Clinic.

The exclusion criteria were age under 18 years, pregnancy or breastfeeding, mental retardation or incapacity, decompensated mental disorders, decompensated congenital heart disease with right heart overload, pulmonary embolism, primary pulmonary hypertension and acquired heart valves diseases (rheumatic or due to infective endocarditis). Patients with coronary artery stenosis of 70% or more, post-infarction cardiosclerosis, left ventricular hypertrophy resulting from arterial hypertension or congenital or acquired heart valves defects, alcoholic cardiomyopathy, systemic immune diseases, oncological diseases and sarcoidosis were also excluded.

The general clinical examination entailed the collection of patient complaints, a comprehensive history, and an objective examination. In the context of family history, particular attention was paid to the occurrence of sudden cardiac deaths in relatives, with a focus on those under the age of 35, as well as the presence of cardiomyopathies, rhythm and conduction disorders in first- and second-degree relatives. The age of disease onset, potential correlation with a preceding infection, and the possibility of an acute onset of symptoms were meticulously documented. All patients underwent a standard set of laboratory investigations, including a full blood count and biochemical panel, as well as instrumental investigations aimed at diagnosing cardiomyopathies, such as a 12-leads electrocardiogram (ECG) at rest, an EchoCG, and 24-hour ECG monitoring. Additional imaging modalities, including cardiac MRI, CT, or scintigraphy, and coronary angiography, were employed to substantiate the diagnosis. The frequency of these studies varied according to the specific type of cardiomyopathy, as detailed in

Table 1.

In addition, medical genetics counselling was provided to patients, with DNA diagnosis subsequently offered in the majority of cases (

Table 1). The isolation of DNA from the peripheral blood of patients was conducted using the phenol-chloroform deproteinization method. The amplification of the studied DNA fragments was conducted via PCR on the Veriti (Applied Biosystems, USA) and Tertsik (DNA-Technology, Russia) amplifiers. The DNA diagnostics were conducted at different time points of this study and employed the following techniques:

1) Bidirectional Direct Sequencing was conducted on an ABI 3730 XL automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

2) High-throughput semiconductor sequencing was conducted on the PGM IonTorrent platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A panel of genes for high-throughput sequencing was designed using AmpliSeq technology (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The presence of the mutations was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

3) Whole exome sequencing was conducted on the NextSeq550Dx instrument (Illumina, USA).

In cases 2 and 3, the presence of the identified mutations was confirmed through direct bidirectional Sanger sequencing. To ascertain the potential clinical significance, all identified genetic variants with a minor allele frequency of less than 5% as reported in the Exome Sequencing Project, 1000 Genomes, and ExAC databases were characterised using the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) recommendations [

26], the Guidelines for Interpreting Data from Massively Parallel Sequencing Methods [

27], and literature and bioinformatic data.

For DNA diagnostics, with the exception of whole exome sequencing, the following scope was applied. The following genes were analysed in the context of ARVC: PKP2, DSG2, DSP, DSC2, JUP, TMEM43, TGFB3, PLN, LMNA, DES, CTTN3, EMD, SCN5A, LDB3, CRYAB and FLNC. The LVNC gene panel included the MYH7, MYBPC3, TAZ, TPM1, LDB3, MYL2, MYL3, ACTC1, TNNT2 and TNNI3B. In the group with primary myocardial hypertrophy, a panel of sarcomeric genes MYBPC3, TAZ, TPM1, LDB3, MYL2, ACTC1, MYL3, MYH7, TNNI3, TNNT2 and/or a targeting study of genes responsible for the occurrence of HCM phenocopies GLA, LAMP2, TTR, FXN, PTPN11, etc.а was employed. The DCM panel comprised the genes ABCC9, ACTN2, ANKRD1, BAG3, CALR3, CAV3, CAVIN4, CSRP3, ILK, DES, DLG1, DMD, DTNA, EMD, EYA4, FHL1, FHOD3, FKTN, FLNA, FOXC1, FOXC2, GATA4, GATA5, GATA6, GATAD1, HSPB1, JPH2, LAMA4, LAMP2, LMNA, MIB1, MYBPC3, MYH6, MYH7, MYLK2, MYOZ2, MYPN, NEBL, NEXN, NKX2-5, NOTCH1, NOTCH2, PDLIM3, PLN, PRKAG2, PSEN1, PSEN2, RBM20, SDHA, SGCA, SGCB, SGCD, SGCE, SGCG, SMAD6, SNTA1, TCAP, TMPO, TNNC1, TNNT2, TPM1, TTN and VCL. In the RCM cohort, the genes that were subjected to evaluation were DES, MYH7, TNNI3, TNNT2. ACTN1, FLNC, TTN, TTR, and additional genes, contingent on the phenotypic features of each patient.

A whole exome sequencing approach was employed to investigate the genetic basis of diverse forms of cardiomyopathies. Bioinformatics searches for genetic variants were conducted within the Hereditary Heart and Vascular Diseases panel, which encompasses 302 genes (

Appendix A).

The diagnosis of myocarditis was established using a combination of techniques, including myocardial morphological examination and/or a non-invasive diagnostic algorithm. (

Table 1).

The material for morphological investigation was obtained in the majority of cases during EMB of the right ventricle (RV) (n=76). EMB was performed in accordance with the standard protocol, with access through the femoral vein using the Cordis STANDARD 5.5 F 104 FEMORAL forceps, with a sample of 3-5 myocardial fragments. In some cases, the material was obtained during open heart surgery (intraoperative myocardial biopsy, n=2), explanted heart examination (n=2) or autopsy (n=6). A total of 86 patients underwent myocardial morphological examination.

Myocardial analysis comprised a standard histological examination conducted under a light microscope with the use of hematoxylin-eosin and Van Gieson picrofuchsin staining (for the detection of connective tissue), in addition to the following: PAS (periodic acid Schiff) staining for the detection of glycogen and other complex carbohydrates, Congo-red staining for amyloid with examination of preparations in polarising light, and, in some cases, Masson and Perls staining. Additionally, an immunohistochemical study of the myocardium was conducted using antibodies (Ab) to CD3, CD20, CD45 and CD68. The myocardium was evaluated by PCR to ascertain the presence of a cardiotropic virus genome, specifically Adenoviruses, Herpes simplex virus type 2, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes simplex virus type 1, Epstein-Barr virus, Varicella-zoster virus, Parvovirus B19, Human herpesvirus 6, Human herpes virus 8 and in some cases hepatitis B and C viruses, and SARS-CoV-2 may also be present. The Dallas criteria were employed for the diagnosis of myocarditis at the myocardial morphological examination, with the additional utilisation of an immunohistochemical study with Ab to markers of T-lymphocytes (CD45+ and CD3+), macrophages (CD68+), and B-lymphocytes (CD20+) [

28].

In patients who had not undergone a myocardial morphological examination, a diagnosis of myocarditis was made on the basis of non-invasive algorithm [

29]. The algorithm is validated, it is based on the assessment of the diagnostic value of various non-invasive criteria in comparison with the data of myocardial morphological examination in 100 patients [

29]. The presence of a complete anamnestic triad (i.e., an association between the disease onset and infection, an acute onset, and a disease duration of less than one year), systemic immune manifestations, and high titres of anticardiac Ab were significant factors in the diagnosis. The Lake Louise criteria were used for the interpretation of MRI data [

30]. In addition, late contrast enhancement of subepicardial localization observed on cardiac CT and myocardial scintigraphy results was evaluated as an additional criterion.

Serum anti-cardiac Ab titres were determined by indirect immunofluorescence analysis. The Ab titres to Ag of the endothelium (AbEnd), cardiomyocyte Ag (AbCM), smooth muscle Ag (AbSM), cardiac conduction fibres Ag (AbCF) and cardiomyocyte nuclei Ag (specific antinuclear factor, ANF) were evaluated. To assess the Ab titres, bovine myocardial fragments were frozen in liquid nitrogen, after which slices prepared in the cryostat were incubated with patient serum at various dilutions (1:40, 1:80, 1:160 and 1:320). After incubation the slices were washed with phosphate buffer and fluoresceinisothiocyanate-labelled Ab against human IgG were applied. Subsequently, the slices were incubated once more, after which they were washed with phosphate buffer and coverslipped with 60% glycerol. The results were examined using a Leica luminescence microscope (DM4000B) at a magnification of ×400. The presence of fluorescent luminescence in the various structures of the bovine myocardium treated with patient serum at each dilution (1:40 to 1:320) was evaluated. The presence of antinuclear Ab at any titre was considered diagnostic. For the other Ab, titre values of 1:160-1:320 were found to be diagnostically significant.

Study design. Patients were divided into two groups according to the results of the examination: the primary group and the comparison group. The primary group consisted of patients with a combination of cardiomyopathy and myocarditis. The second group, used for comparison, consisted of patients with isolated cardiomyopathies without myocarditis. Patients in both groups were subdivided according to the type of cardiomyopathy (ARVC, HCM, DCM, LVNC and RCM). A comparison was conducted between patients with and without myocarditis within the respective subgroups. The treatment regimen included the administration of immunosuppressive therapy (IST) to patients with myocarditis without contraindications and with the possibility of regular laboratory and instrumental follow-up. Patients from both groups were treated with cardiotropic, antiarrhythmic, and diuretic therapies if indicated. Surgical treatment, including radiofrequency ablation of arrhythmogenic foci, implantation of cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD), and heart transplantation, was performed if necessary. In addition, the titres of anti-cardiac Ab in the presence of myocarditis were evaluated over time, and ECG at rest, 24-hour ECG monitoring and EchoCG were repeated regardless of the presence of myocarditis. The primary endpoints were death and heart transplantation, while the secondary endpoints were progression of CHF, syncope, sustained VT, and appropriate ICD intervention.

Statistical analysis. The data were subjected to statistical analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26. The presentation of discrete data is in the form of distributions of absolute values and percentages. Continuous data are presented as the arithmetic mean ± standard deviation when the distribution of values is normal, or as quartiles 50 [25; 75] when the distribution of the studied values differ significantly from normal. The normality of the distribution was evaluated using the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test when the number of observations was 50 or greater, and the Shapiro-Wilk test was employed when the number of observations was less. Differences between groups were evaluated using Student T-test (for variables with normal distribution and n ≥ 50) or Mann-Whitney U-test (for variables without normal distribution and n < 50). Risk factors were assessed using Cox regression in all subgroups, with the exception of RCM, which had an insufficient number of observations. The survival rates, contingent on the presence or absence of myocarditis, are illustrated graphically as Kaplan-Meier curves.

4. Discussion

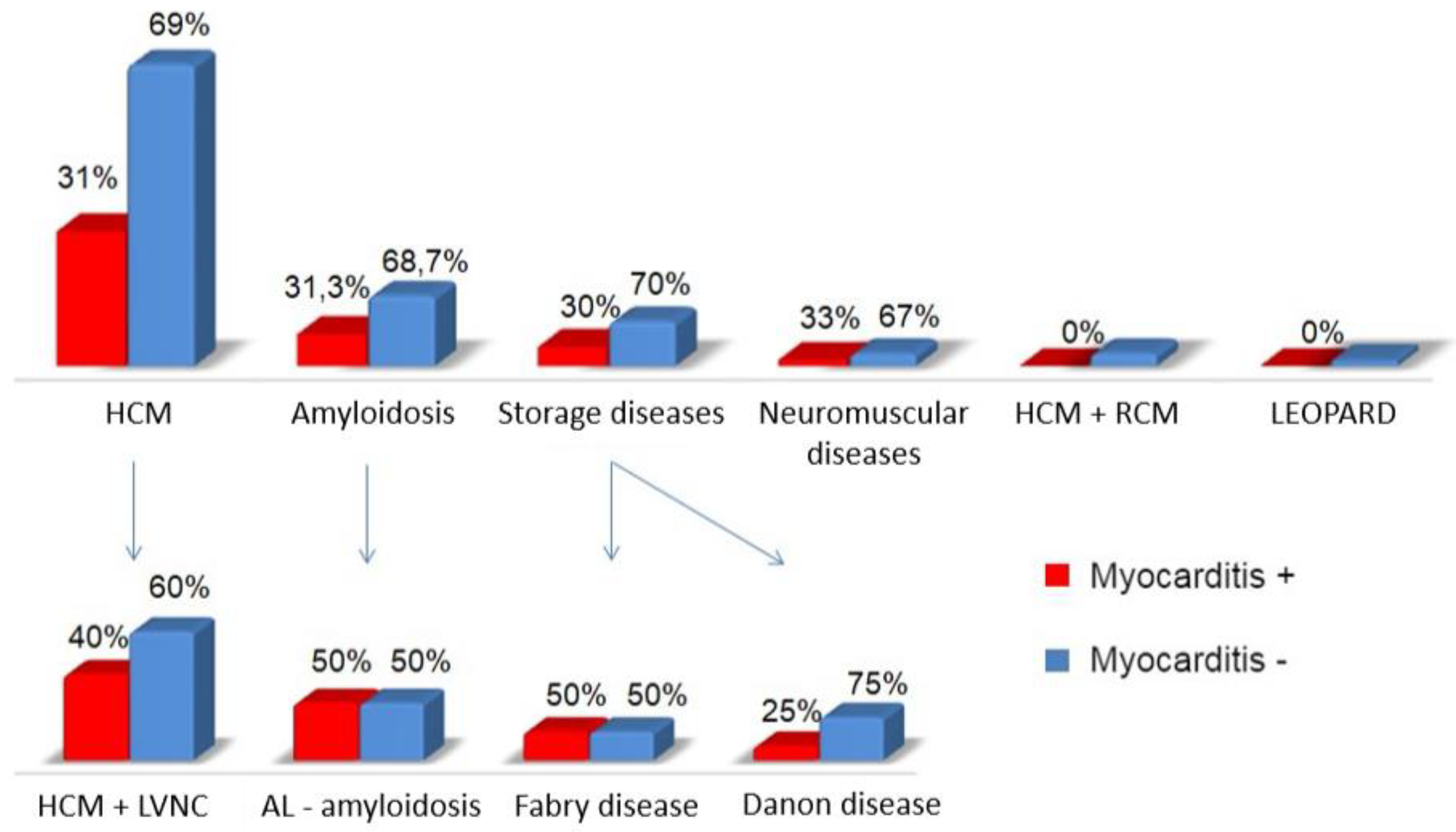

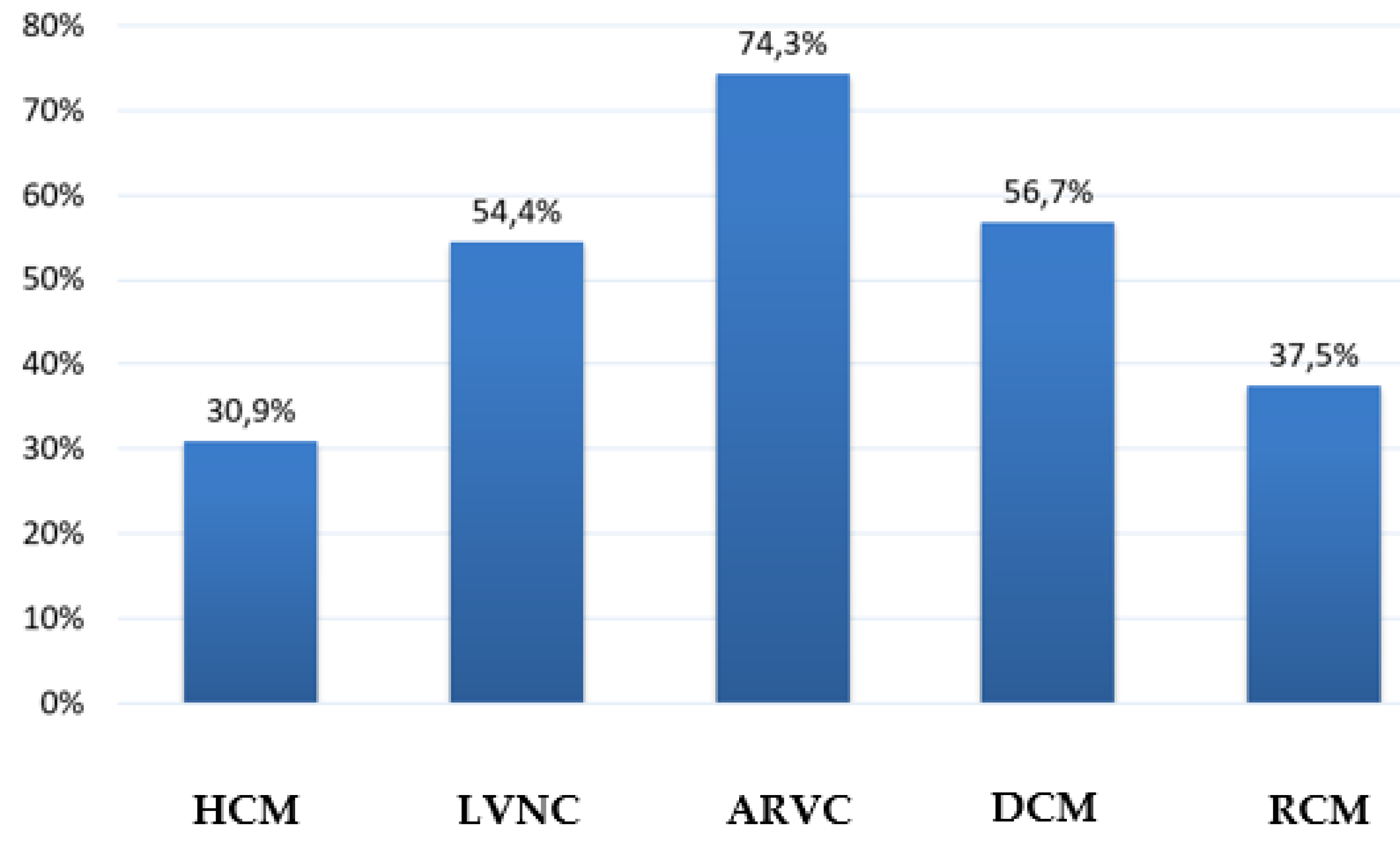

Myocarditis is a common phenomenon in cardiomyopathies, occurring either as a primary viral process or as a secondary autoimmune reaction, as indicated by elevated Ab titres directed against cardiac Ag. The prevalence of myocarditis differed according to the specific genetic form of cardiomyopathy (

Figure 7).

The highest incidence was observed in ARVC. Myocarditis was observed in almost three-quarters of patients, and the significant contribution of autoimmune aggression to the development of inflammation was noteworthy. This is in contrast to other cardiomyopathies, in which all types of anticardiac Ab are not elevated concurrently. In addition to the immune mechanism, a primary viral component was also identified, as evidenced by the detection of a viral genome in myocardial cells in half of the patients. It is also noteworthy that in approximately half of the patients with ARVC, the disease manifested acutely and was linked to a preceding viral infection. The frequency of pathogenic mutations detection was also the highest in ARVC, amounting to 25%. The contribution of inflammation to the development and progression of ARVC has been extensively discussed in the literature, with reference to both 'trivial' viral myocarditis [

31,

32] and auto-Ab [

33,

34,

35]. The mortality rate in patients with a combination of myocarditis and ARVC was the lowest, which can be attributed to the favourable outcomes observed in those with myocarditis, due to the potential for influencing the autoimmune component with IST. Therefore, myocarditis in ARVC is a significant contributor to the formation of the disease phenotype and the disease's overall outcome.

The second most frequently observed concomitant myocarditis was in primary DCM, accounting for 56.7% of cases. It is noteworthy that the viral genome was detected in only a quarter of the patients, a frequency about half that observed in ARVC, HCM or LVNC. This may indicate a greater role for immune mechanisms in the development of myocarditis in this cardiomyopathy. It is of particular note that AbEnd is increased in comparison to patients with isolated DCM, which is absent in cardiomyopathies other than ARVC. This may be indicative of vasculitis on the background of myocarditis. The frequency of mutation detection in patients with the combination of primary DCM and myocarditis was comparable with other groups, amounting to 20%. The presence of mutations that result in the synthesis of altered cardiomyocyte proteins may also represent an additional target for the development of autoimmune myocardial damage [

2]. Despite the relatively limited number of patients with a positive viral result, the vast majority of patients (91.2%) presented with an acute onset of the disease, a phenomenon that is considerably less prevalent in isolated cardiomyopathies. Furthermore, in approximately half of these cases, the onset was associated with a previous infection. It seems probable that the trigger for the development of inflammation in these cases was not the virus itself and its inherent properties, but rather the pathological activation of the immune system subsequent to the disease [

36]. The mortality rate among patients with DCM combined with myocarditis was the highest (35.3%) in comparison to other cardiomyopathies. This can be seen as a manifestation of the underlying disease, but it also reflects the severity of myocarditis itself. The mortality rate was lower (26.9%) among patients with DCM without myocarditis, and it was even higher (53.8%) among patients with myocarditis who did not receive IST.

In terms of frequency, LVNC occupies the third position, with a slight margin separating it from DCM (54.4%). The noncompact layer is a favourable target for viral attachment [

18,

19,

20], as evidenced by the fact that almost half of the patients were virus-positive. Furthermore, acute onset of the disease was recorded in 75% of cases. Concurrently, an active immune component was also present, as evidenced by elevated Ab titres for AbCM, AbSM, and AbCF. The frequency of mutation detection in patients with a combination of LVNC and myocarditis was the lowest in comparison to other cardiomyopathies. This is attributable to the high genetic heterogeneity of LVNC and the fact that not all genes that may lead to a non-compaction phenotype have been identified. The incidence of unfavourable outcomes in the combination of myocarditis with LVNC was relatively high (20.6%), with a further 7.9% having undergone heart transplantation. In the absence of this procedure, the outcome would also have been unfavourable. As in DCM, this is not only a feature of the cardiomyopathy itself, but also the influence of myocarditis. In patients with myocarditis who did not receive IST, these figures are significantly higher (death, 36%; death+ heart transplantation, 44%) compared to patients with isolated LVNC, in whom mortality was only 5.3%.

The fourth highest incidence of myocarditis was observed in the RCM group (37.5%). The frequency of viral genome detection in this group was relatively low in comparison to other cardiomyopathies, as well as in DCM. However, this may be attributed to the limited number of patients who underwent myocardial morphological examination and the fact that this group is the smallest due to the rarity of RCM. Nevertheless, the acute onset and association with infection in patients with myocarditis combined with RCM were also recorded less frequently than in other cardiomyopathies. Furthermore, there were no differences in these features between patients with and without RCM combined with myocarditis. This may indicate that the course of myocarditis in RCM is more hidden and latent. A distinctive feature of this group was a significant increase in ANF titre compared with other cardiomyopathies, while other Ab remained relatively low and did not differ statistically significantly from those in patients with isolated RCM. This may reflect a specific mechanism of myocarditis in RCM that requires further investigation. The mortality rate associated with the coexistence of myocarditis and RCM was found to be minimal and comparable to that observed in ARVC. As for treatment results, it requires further study on a larger number of patients to gain a full understanding of the results of myocarditis treatment in patients with RCM.

Concomitant myocarditis was observed with the lowest frequency in HCM. The frequency of this occurrence was 30.9%, with HCM exhibiting the highest percentage of virus-positive myocarditis (58.3%). This indicates that hypertrophied myocardium, as well as non-compacted layer, may be a susceptible target for viral infection, particularly given that both HCM and LVNC may be attributable to mutations in sarcomeric genes, which emphasises their common characteristics. With regard to the frequency of acute onset and the association of onset with infection, HCM is only slightly less prevalent than LVNC. Nevertheless, we found no data in the literature on the molecular mechanisms that might favour adhesion or rapid spread of the virus to the myocardium in mutations in sarcomeric genes, as in mutations in genes associated with DCM. With regard to the frequency of detection of pathogenic mutations, HCM is ranked second only to ARVC and RCM, with a prevalence of one-fifth among patients with myocarditis. A distinctive feature of HCM in conjunction with myocarditis is the occurrence of an isolated elevation in Ab titres directed towards cardiomyocytes, in comparison to patients exhibiting isolated HCM. This may be indicative of the fact that cardiomyocytes are the direct target of an autoimmune attack, including the disruption of the structure of sarcomeric proteins. A review of the literature reveals a paucity of studies examining anticardiac Ab in HCM. The majority of these studies, dating from the 1970s to 1980s, merely document the presence of such Ab in patients with idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis. The most recent study, published in 1992, offers a more comprehensive examination of this topic. B. Maisch demonstrated that 78% of patients with HCM had Ab to sarcolemma and 43% had Ab to myofibrils, which is consistent with our data on Ab to cardiomyocytes [

37]. The incidence of fatal outcomes in patients with myocarditis and HCM was high (26.7%), ranking second only to DCM. In patients with HCM without myocarditis, the mortality rate was significantly lower, at 6.4%. Therefore, myocarditis has a considerable effect on the prognosis of HCM, as is the case with other cardiomyopathies.

One of the principal findings of our study is the beneficial impact of IST for myocarditis. While there are several papers in the literature on the combination of myocarditis with various genetic cardiomyopathies, as referenced in the introduction, they are typically limited to a mere statement of the presence of myocarditis in this group of patients. There is a paucity of data regarding the treatment of myocarditis in genetic cardiomyopathies. Our study demonstrate that patients with cardiomyopathies benefit from administration of IST, which enables at least stabilisation (and in some cases improvement) of LV systolic function, enhances the efficacy of antiarrhythmic therapy, and reduces the probability of adverse outcomes. Conversely, patients with a combination of myocarditis and cardiomyopathies who did not received IST demonstrated unfavourable outcomes and a higher incidence of adverse events (in LVNC, ARVC and DCM groups).

Appendix A

The following is a list of genes from the «Hereditary Heart and Vascular Diseases» panel.

AARS2. ABCC6. ABCC9. ABLI, ACAD9. ACADVL, ACTAI, ACTA2. ACTCI, ACTN2. ACVR2B, ACVRLI, ADAMTS2. AGK, AGI, AGPAT2. AKAP9. ALMSI, ALPK3. ANK2. ANO5. APOAI, ATPAF2. BAG3. BAG5. BRAF, CACNA1C, CACNA1D, CACNB2. CALMI, CALM2. CALM3. CALR3. CAPN3. CASQ2. CASZI, CAV3. CBL, CDH2. CHRM2. CDK13. CFAP45. CEAP52. CFCI, CHD7. CHST14. CITED2. COLIAI, COLIA2. COLAI, COLSAI, COL5A2. COXIS, CRELDI, CPT2. CRYAB, CSRP3. CTNNA3. DBH, DCHS1. DES, DMD, DNAJCI9. DOLK, DPM3. DSC2. DSG2. DSP, DTNA, DYSF, EEF1A2. ELAC2. ELN, EMD, ENG, ENPPI, EPG5. EPHB4. ETEA, ETFDH, EYA4. FAH, FBN1. FBN2. FBXL4. FBX032. FHL1. FHOD3. FKBP14. FKRP, FKTN, FLNA, FLNC, FLT4. FOXD4. FOXFI, FOXREDI, FXN, GAA, GATA4. GATAS, GATA6. GATAD1. GATC, GBE1. GDF2. GFMI, GLA, GLB1. GJA1. GJA5. GMPPB, GNAI2. GNB5. GPD1L, GSK3B, GTPBP3. GUSB, HADHA, HAND1. HAND2. HCN4. HFE, HRAS, IDUA, ILK, CRPPA\ISPD, JAG1. JPH2. JUP, KCNAS, KCNEI, KCNE2. KCND3. KCNH2. KCNJ2. KCNJ5. KCNQI, KLHL24. KRAS, LAMA2. LAMA4. LAMP2. LARGEI, LDB3. LEMD2. LMNA, LMOD2. LOX, LRRC1O, LZTR1. MAP2K1. MAP2K2. MAP3K8. MAPK1. MED13L, MEAP5. MIBI, MIPEP, MLYCD, MMP21. MNS1. MRAS, MRPL3. MRPL44. MRPS22. MTO1. MYBPC3. MYBPHL, MYH6. MYH7. MYHIL, MYL2. MYL3. MYL4. MYLK, MYLK2. MYO18B, MYOT, MYOZ2. MYPN, MYRE, NDUFAF2. NEXN, NFI, NKX2-5. NKX2-6. NODAL, NONO, NOSIAP, NOTCH1. NOTCH2. NPPA, NR2F2. NRAP, NUPI55. PARS2. PCCA, PCCB, PKDILI, PKP2. PLDI, PLEC, PLEKHM2. PLN, PNPLA2. POMTI, PPA2. PPCS, PPPICB, PPPIRI3L, PRDM6. PRDMI6. PRKAG2. PRKDI, PRKGI, PSENI, PSEN2. PTPNII, ORSLI, RAFI, RASAI, RASA2. RBCKI, RBM20. RITI, RMNDI, RPL3L, RRAS, RRAS2. RYR2. SALL4. SCN10A, SCN1B, SCN2B, SCN3B, SCN4B, SCN5A, SCNNIB, SCNNIG, SCO1. SCO2. SDHA, SELENON, SGCA, SGCB, SGCD, SGCG, SHOC2. SKI, SLC2A10. SIC22A5. SLC25420. SLC2543. SLC2544. SLC39A13. SMAD2. SMAD3. SMAD4. SMAD6. SMCHDI, SNTA1. SOS1. SOS2. SPEG, SPRED1. SPRED2. STAG2. TAB2. TANGO2. TAZ, TBXI, TBX20. TBX3. TCAP, TECRL, TFAP2B, TGFB2. TGFB3. TGFBR1. TGFBR2. TLL1. TMEM43. TMEM70. TNNCI, TINZ3. TNNI3K, TNNT2. TNXB, TOR1AIP1. TPM1. TRDN, TRIM32.TRPM4. TSFM, TTN, TTR, VARS2. VCL, VCP, ZFPM2. ZIC3.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation depicts the structure of the patients included in the study, taking into account the presence of mixed phenotypes.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation depicts the structure of the patients included in the study, taking into account the presence of mixed phenotypes.

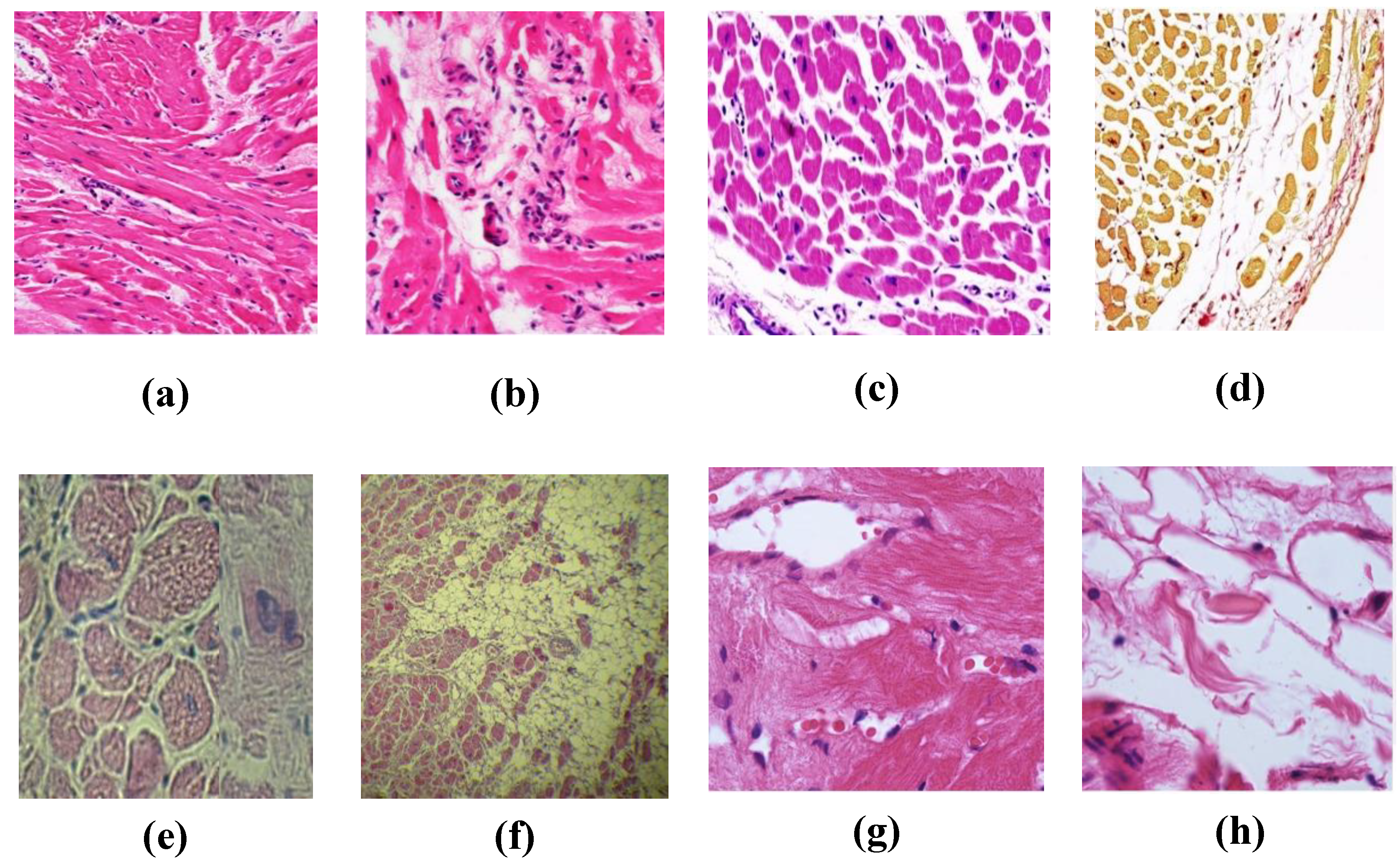

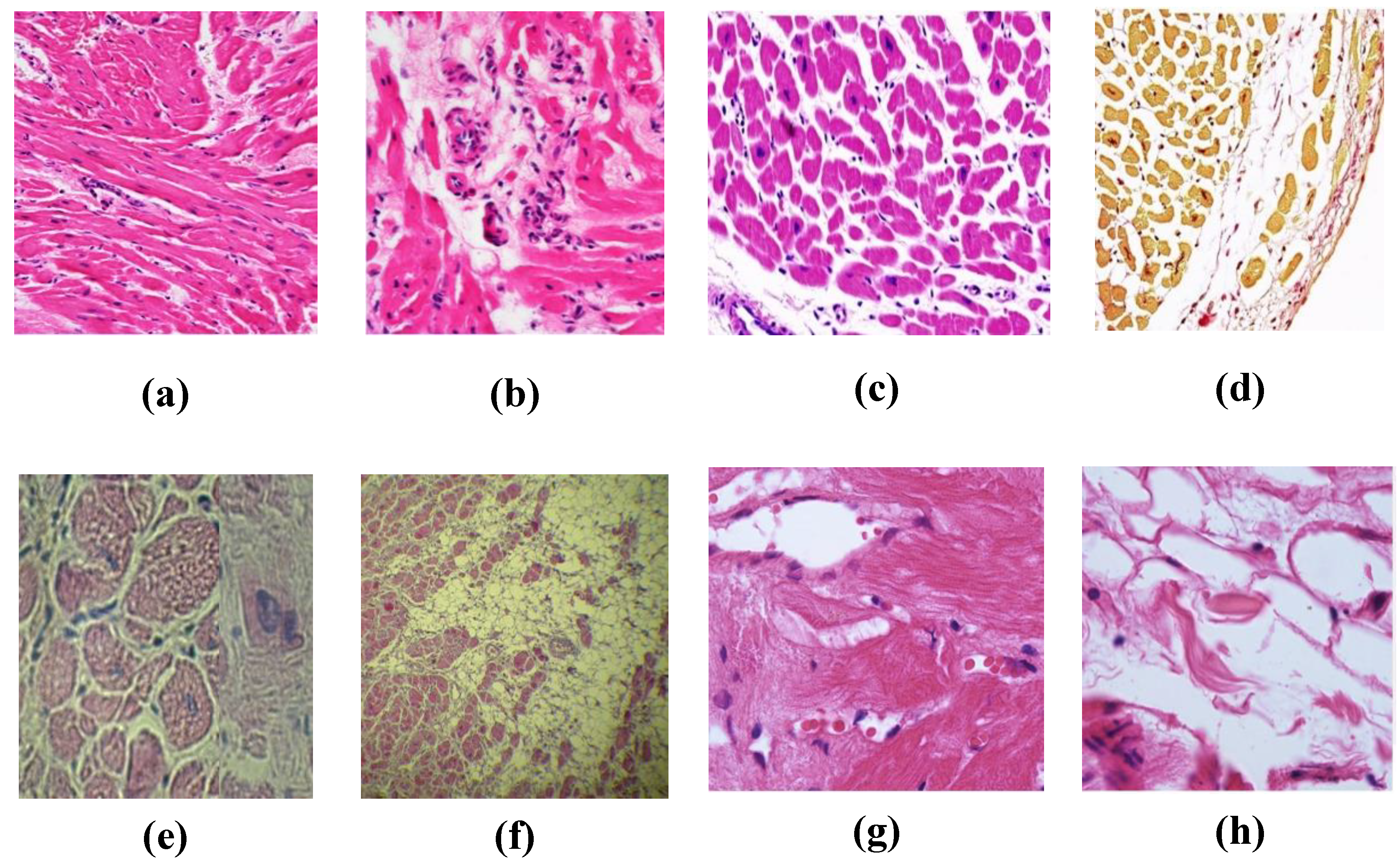

Figure 2.

Results of morphological study of myocardium in different cardiomyopathies. (a, b) - myocardial changes in HCM in the form of bizarre shape of branching cardiomyocytes, small focal cardiosclerosis with neoangiogenesis and lymphohistiocytic infiltrates in sclerosis foci; (c,d) - myocarditis in HCM with productive capillarites and development of interstitial sclerosis: myocardium is divided by fibrous septa of unequal thickness into lobules, uneven hypertrophy of nuclei is noted, vessels with swollen endothelium and perivascular accumulations of lymphoid elements, more than 14 in the field of view at high magnification; (e,f) - picture of lymphohistiocytic infiltration in ARVC, pronounced total fibrous-fatty replacement of myocardium of LV, the area of preserved myocardium in some areas does not exceed 25%; (g,h) - lymphohistiocytic infiltrates perivascularly and in the interstitium (g) in a patient with DCM within laminopathy, fatty tissue replacement of dead cardiomyocytes (h); (i,j) SARS-CoV-2 induced myocarditis in a patient with RCM caused by mutations in MyBPC3 and LZTR1 genes: marked lymphohistiocytic infiltration, areas of lipomatosis, dystrophic changes of cardiomyocytes; (k,l) - Ab to SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (k) and Spike-antigen (l). a, b, c, e, f, g, h, i, j - haematoxylin and eosin staining. d - Van Gieson picrofuchsin staining. k, l - immunohistochemical study. a, f - low magnification; b, c, d, e, g, h, i, j, k, l - high magnification.

Figure 2.

Results of morphological study of myocardium in different cardiomyopathies. (a, b) - myocardial changes in HCM in the form of bizarre shape of branching cardiomyocytes, small focal cardiosclerosis with neoangiogenesis and lymphohistiocytic infiltrates in sclerosis foci; (c,d) - myocarditis in HCM with productive capillarites and development of interstitial sclerosis: myocardium is divided by fibrous septa of unequal thickness into lobules, uneven hypertrophy of nuclei is noted, vessels with swollen endothelium and perivascular accumulations of lymphoid elements, more than 14 in the field of view at high magnification; (e,f) - picture of lymphohistiocytic infiltration in ARVC, pronounced total fibrous-fatty replacement of myocardium of LV, the area of preserved myocardium in some areas does not exceed 25%; (g,h) - lymphohistiocytic infiltrates perivascularly and in the interstitium (g) in a patient with DCM within laminopathy, fatty tissue replacement of dead cardiomyocytes (h); (i,j) SARS-CoV-2 induced myocarditis in a patient with RCM caused by mutations in MyBPC3 and LZTR1 genes: marked lymphohistiocytic infiltration, areas of lipomatosis, dystrophic changes of cardiomyocytes; (k,l) - Ab to SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (k) and Spike-antigen (l). a, b, c, e, f, g, h, i, j - haematoxylin and eosin staining. d - Van Gieson picrofuchsin staining. k, l - immunohistochemical study. a, f - low magnification; b, c, d, e, g, h, i, j, k, l - high magnification.

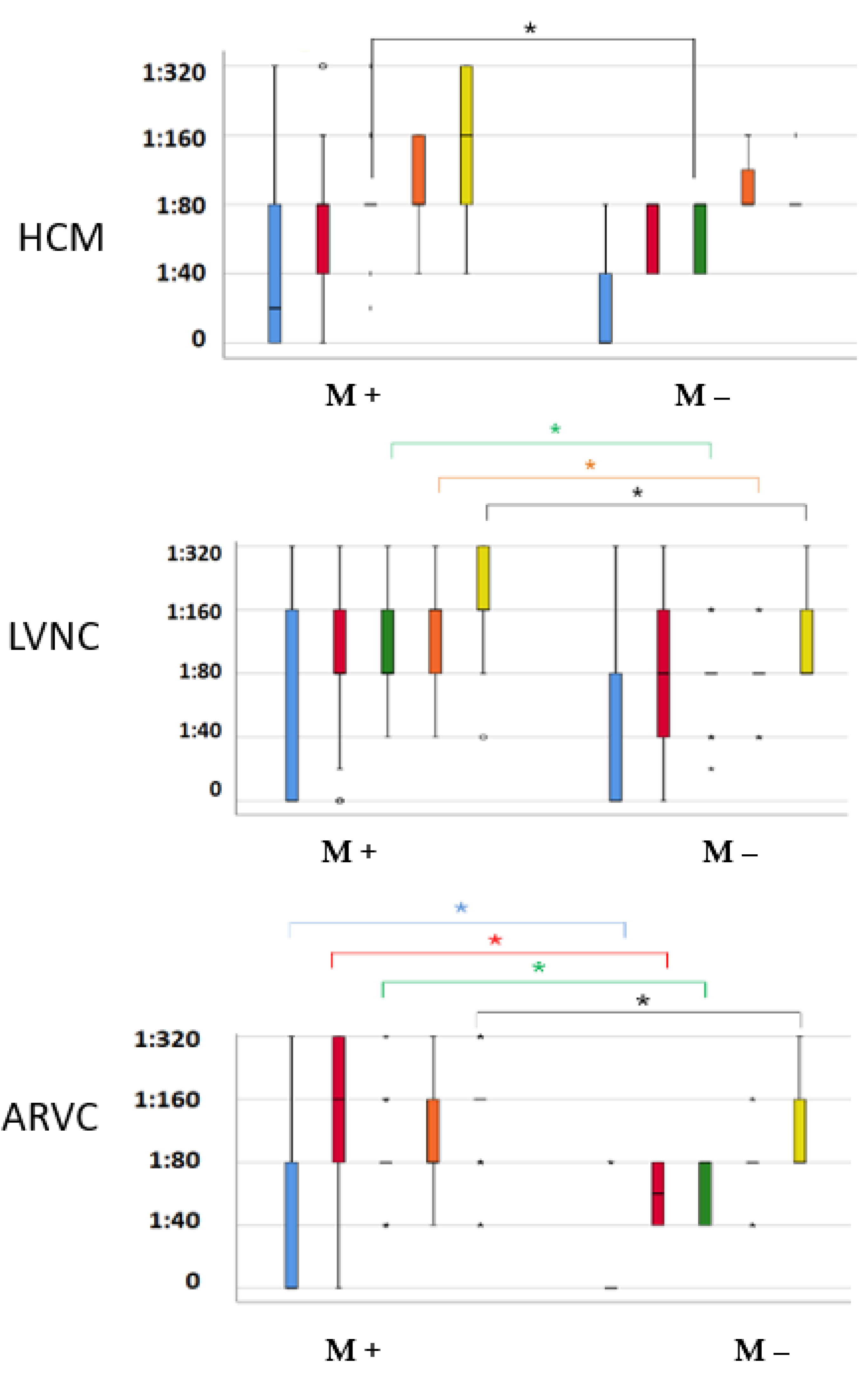

Figure 3.

Titres of anti-cardiac antibodies in different cardiomyopathies, depending on the presence (M+) or absence (M-) of myocarditis.

Figure 3.

Titres of anti-cardiac antibodies in different cardiomyopathies, depending on the presence (M+) or absence (M-) of myocarditis.

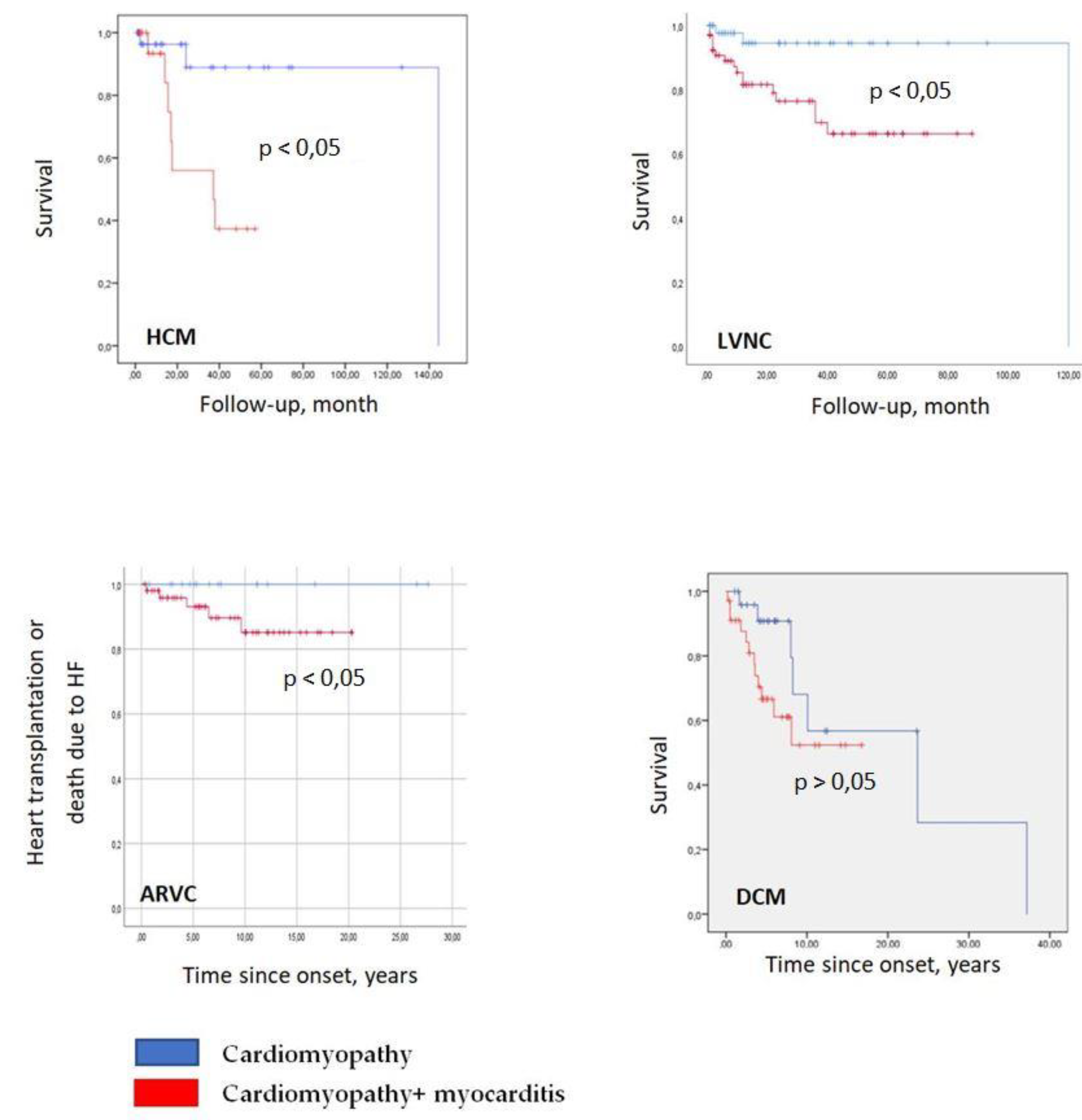

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves for different genetic cardiomyopathies, depending on the presence or absence of myocarditis. Red colour - patients with a combination of cardiomyopathy and myocarditis, blue colour - patients with isolated cardiomyopathies.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves for different genetic cardiomyopathies, depending on the presence or absence of myocarditis. Red colour - patients with a combination of cardiomyopathy and myocarditis, blue colour - patients with isolated cardiomyopathies.

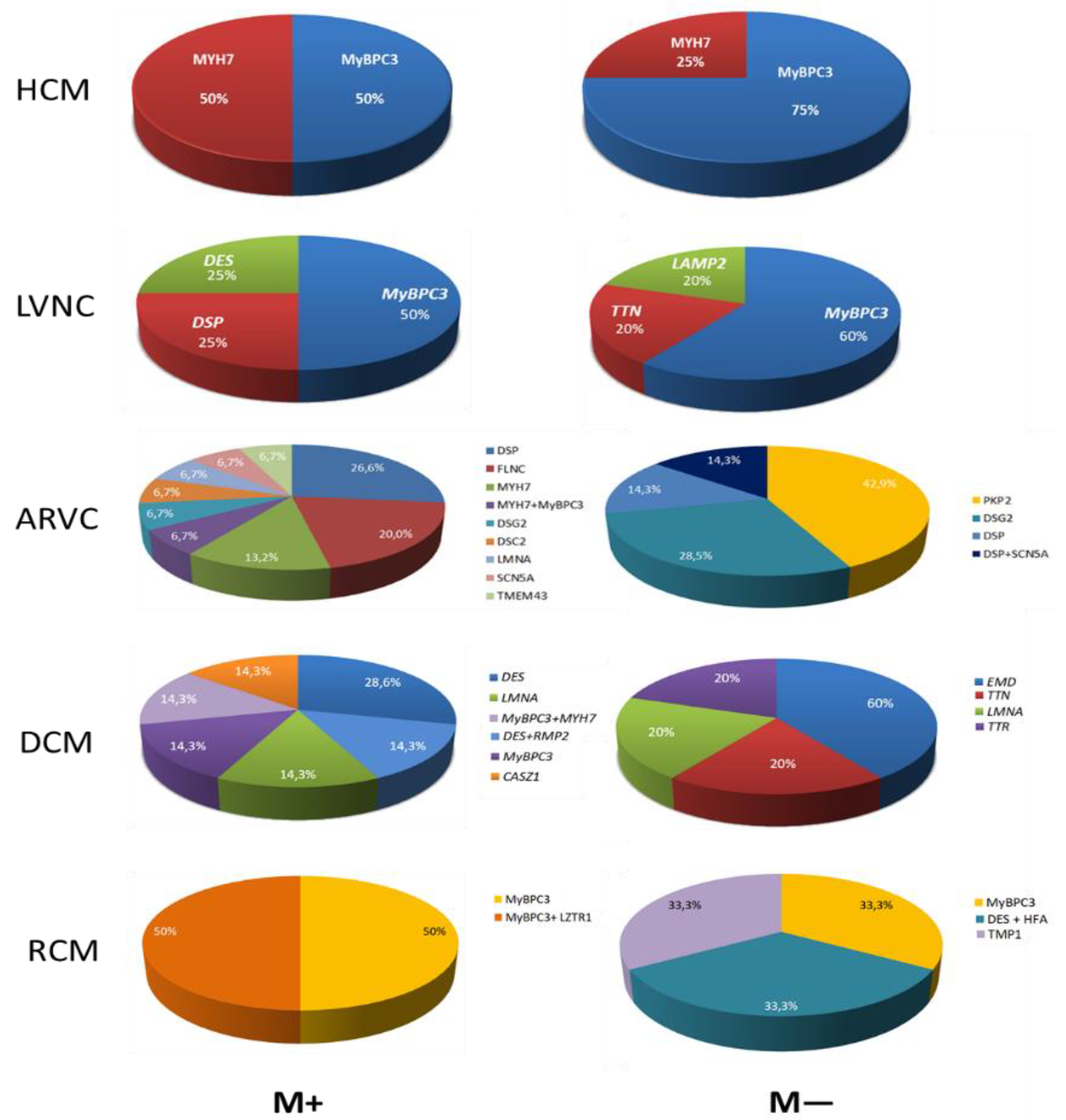

Figure 5.

Spectrum of pathogenic mutations in different cardiomyopathies, depending on the presence (M+) or absence (M-) of myocarditis.

Figure 5.

Spectrum of pathogenic mutations in different cardiomyopathies, depending on the presence (M+) or absence (M-) of myocarditis.

Figure 6.

Frequency of myocarditis in different causes of myocardial hypertrophy syndrome.

Figure 6.

Frequency of myocarditis in different causes of myocardial hypertrophy syndrome.

Figure 7.

Frequency of superimposed myocarditis, depending on the type of cardiomyopathy.

Figure 7.

Frequency of superimposed myocarditis, depending on the type of cardiomyopathy.

Table 1.

Frequency of investigations in different cardiomyopathies.

Table 1.

Frequency of investigations in different cardiomyopathies.

| Investigation |

HCM |

LNVC |

ARVC |

DCM |

RCM |

| Determination of anti-cardiac Ab titres in blood serum, % |

43.0 |

81.6 |

85.7 |

86.7 |

46.9 |

|

| Morphological investigation of myocardium with determination of cardiotropic virus genome, % |

30.0 |

20.8 |

12.9 |

33.3 |

36.7 |

|

| DNA diagnostic, % |

96.0 |

41.0 |

100.0 |

71.7 |

59.4 |

|

| Cardiac MRI, % |

31.0 |

84.0 |

91.4 |

30.0 |

37.5 |

|

| Cardiac CT, % |

32.0 |

68.0 |

27.1 |

55.0 |

12.5 |

|

| Myocardial scintigraphy, % |

11.0 |

21.6 |

7.1 |

18.3 |

18.8 |

|

| Coronary angiography, % |

18.0 |

27.2 |

21.4 |

43.3 |

21.9 |

|

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints of patients with HCM, classified according to the presence or absence of myocarditis.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints of patients with HCM, classified according to the presence or absence of myocarditis.

| Characteristic |

Myocarditis + |

Myocarditis - |

p |

| N (%) |

21 (30.9) |

47 (69.1) |

- |

| Age, years |

44.6 ± 12.9 |

48.8 ± 14.5 |

>0.05 |

| Acute onset, n (%) |

13 (61.9) |

2 (4.3) |

<0.001 |

| Relation to prior infection, n (%) |

13 (61.9) |

1 (2.1) |

<0.001 |

| Myocardial morphological investigation, n (%) |

11 (52.4) |

9 (19.1) |

0.009 |

| Viral genome in myocardium, n (% of patients with myocardial morphological examination) |

7 (63.6) |

5 (55.6) |

>0.05 |

| AbCM, titre |

1:80 [1:80; 1:80-1:160] |

1:80 [1:40; 1:80] |

0.017 |

| Pathogenic mutations, n (%) |

6 (28.6) |

8 (17.0) |

>0.05 |

| LV EF (EchoCG), % |

51.9 ± 16.3 |

57.8 ± 11.2 |

>0.05 |

| LV EF (EchoCG) ≤ 45%, n (%) |

8 (38.1) |

7 (14.9) |

0.032 |

| RV hypertrophy, n (%) |

4 (19) |

2 (4.3) |

0.059 |

| Maximum LV wall thickness (MSCT), mm |

18.0 ± 3.0 |

23.1 ± 6.5 |

0.038 |

| NYHA CHF class |

3 [2; 3] |

2 [1; 3] |

0.026 |

| Presence of atrial fibrillation, n (%) |

6 (28.6) |

25 (53.2) |

0.044 |

| PVCs per day, pcs. |

289 [14; 3513] |

63 [10; 404] |

>0.05 |

| Presence of VT, n (%) |

11 (52.4) |

23 (48.9) |

>0.05 |

| ICD implantation, n (%) |

6 (28.6) |

11 (23.4) |

>0.05 |

| Death, n (%) |

7 (33.3) |

3 (6.4) |

0.01 |

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints of patients with LVNC depending on the presence or absence of myocarditis.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints of patients with LVNC depending on the presence or absence of myocarditis.

| Characteristic |

Myocarditis + |

Myocarditis - |

p |

| N (%) |

68 (54.4) |

57 (45.6) |

- |

| Age, years |

46.3 ± 16.5 |

48.2 ± 16.4 |

>0.05 |

| Duration of the disease, months |

27 [4; 84] |

53 [13; 144] |

0.016 |

| Acute onset, n (%) |

51 (76) |

15 (26.3) |

<0.001 |

| Relation to prior infection, n (%) |

40 (58.8) |

9 (15.8) |

<0.001 |

| Myocardial morphological investigation, n (%) |

21 (30.9) |

5 (8.8) |

>0.05 |

| Pathogenic mutations, n (%) |

8 (11.8) |

5 (8.8) |

>0.05 |

| Family burden |

9 (13.2) |

17 (29.8) |

0.02 |

| Structural and functional parameters in echocardiography and MRI |

| EDV |

168 [120; 202] |

134 [100; 182] |

0.043 |

| ESV |

100 [70; 137] |

81 [49; 121] |

0.03 |

| LV EF (ЭхoКГ), % |

35 ± 13 |

43±14 |

0.002 |

| LV EF (ЭхoКГ) ≤ 35%, n (%) |

37 (54.4) |

17 (29.8) |

0.004 |

| RV, ml |

73 [49; 90] |

54 [45; 86] |

0.042 |

| E/A |

1.6 [1.1; 2.6] |

1.3 [0.7; 1.8] |

0.046 |

| LGE at MRI, n (%) |

27 (39.7) |

9 (15.8) |

0.004 |

| Parameters characterising heart failure |

| NYHA CHF class |

2-3 [1; 3] |

2 [1; 3] |

0.029 |

| Administration of ACE, n (%) |

51 (75) |

25 (43.9) |

<0.001 |

| Administration of β-blocker + ACE, n (%) |

43 (63.2) |

26 (45.6) |

0.017 |

| Administration of spironolactone, n (%) |

47 (69.1) |

26 (45.6) |

0.003 |

| Parameters characterising rhythm disturbances |

| Need for anticoagulant prescriptions, n (%) |

38 (55.9) |

22 (38.6) |

0.017 |

| Presence of VT, n (%) |

46 (67.6) |

20 (35.1) |

<0.001 |

| Sustained VT, n (%) |

12 (17.6) |

6 (10.5) |

>0.05 |

| Implantation of ICDs, n (%) |

26 (38.2) |

13 (22.8) |

0.048 |

| End points |

| Appropriate ICD interventions, n (% of ICD patients) |

11 (42.3) |

3 (23.1) |

0.181 |

| Death, n (%) |

16 (23.5) |

3 (5.3) |

0.004 |

| Heart transplantation, n (%) |

6 (8.8) |

1 (1.8) |

0.09 |

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints of patients with ARVC depending on the presence or absence of myocarditis.

Table 4.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints of patients with ARVC depending on the presence or absence of myocarditis.

| Characteristic |

Myocarditis + |

Myocarditis - |

p |

| N |

52 |

18 |

- |

| Acute onset, n (%) |

55.8 |

44.4 |

0.364 |

| Relation to prior infection, n (%) |

53.8 |

11.1 |

0.002 |

| Myocardial morphological investigation, n (%) |

15.4 |

5.5 |

>0.05 |

| Pathogenic mutations, n (%) |

28.9 |

38.9 |

0.380 |

| LV EF (EchoCG), % |

53.1 ± 14.3 |

60.0 ± 7.5 |

0.071 |

| LV EF (EchoCG) ≤ 35%, n (%) |

11.5 |

0 |

0.192 |

| NYHA CHF class |

15.4 |

0 |

0.09 |

| PVC, thousands |

18.2 [3.2; 36.0] |

13.7 [2.1; 19.0] |

0.161 |

| RFA, % |

30.8 |

16.7 |

0.187 |

| Efficiency of RFA, % |

50 |

100 |

0.470 |

| Sustained VT, % |

26.9 |

50.0 |

0.075 |

| Fat in the RV (MRI), % |

42.3 |

66.7 |

0.040 |

| RV thinning, % |

30.8 |

61.1 |

0.010 |

| Death, % |

11.5 |

16.7 |

0.420 |

| Death/HT due to progressive CHF |

9.6 |

0 |

0.215 |

Table 5.

Follow-up of patients with ARVC combined with myocarditis who did and did not receive IST.

Table 5.

Follow-up of patients with ARVC combined with myocarditis who did and did not receive IST.

| Characteristic |

Baseline |

Follow-up |

p |

| IST + |

| LV EF, % |

51.0 ± 13.6 |

50.9 ±12.5 |

0.166 |

| EDS LV / antero-posterior dimension RV |

1.9 ± 0.6 |

1.9 ±0.5 |

0.968 |

| PVCs, thousands per day |

15 [3.2; 35.5] |

0.7 [0.01; 3.8] |

<0.001 |

| Non-sustained VT, % |

55.3 |

26.3 |

0.021 |

| Sustained VT, % |

21.1 |

0 |

0.008 |

| IST - |

| LV EF, % |

57.7 ±16.1 |

53.6 ± 10.6 |

0.018 |

| EDS LV / antero-posterior dimension RV |

2.0 ± 0.6 |

2.4 ± 0.5 |

0.091 |

| PVCs, thousands per day |

20 [0.6; 38] |

3.7 [0; 9.3] |

0.028 |

| Non-sustained VT, % |

71.4 |

16.7 |

0.046 |

| Sustained VT, % |

42.9 |

0 |

0.317 |

Table 6.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints of patients with DCM depending on the presence or absence of myocarditis.

Table 6.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints of patients with DCM depending on the presence or absence of myocarditis.

| Characteristic |

Myocarditis + |

Myocarditis - |

p |

| N |

34 |

26 |

- |

| Acute onset, n (%) |

91.2 |

76.9 |

0.065 |

| Relation to prior infection, n (%) |

55.9 |

26.9 |

0.018 |

| Myocardial morphological investigation, n (%) |

47.1 |

15.4 |

>0.05 |

| Pathogenic mutations, n (%) |

20.6 |

19.2 |

0.580 |

| EDV, ml |

182 [126; 233] |

198 [142; 243] |

0.584 |

| LV EF (EchoCG), % |

25 [20; 38] |

33 [27; 41] |

0.041 |

| Interventricular septum, mm |

9 [8; 10] |

11 [9; 12] |

0.024 |

| NYHA CHF class ≥ 3 , % |

3 [2; 3] |

3 [2; 3] |

0.651 |

| Administration of torasemide, % |

50.0 |

23.1 |

0.031 |

| PVCs, number per day. |

961 [160; 5227] |

658 [6; 4281] |

0.406 |

| Non-sustained VT, % |

58.8 |

34.6 |

0.054 |

| Administration of amiodarone, % |

67.6 |

46.2 |

0.059 |

| ICD Implantation, % |

38.2 |

26.9 |

0.261 |

| SCD, % |

14.7 |

3.8 |

0.171 |

| SCD + ICD interventions, % |

29.4 |

15.4 |

0.168 |

| Death, % |

35.3 |

26.9 |

0.342 |

| Heart transplantation, % |

11.8 |

7.7 |

0.472 |

Table 7.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints of patients with RCM, depending on the presence or absence of myocarditis.

Table 7.

Baseline characteristics and endpoints of patients with RCM, depending on the presence or absence of myocarditis.

| Characteristic |

Myocarditis + |

Myocarditis - |

p |

| N (%) |

5 (33.3) |

10 (66.6) |

- |

| Age, years |

54.0 ± 17.5 |

49.4 ± 17.4 |

0.713 |

| Acute onset, n (%) |

0 |

1 (10) |

0.667 |

| Relation to prior infection, n (%) |

2 (40) |

2 (20) |

0.758 |

| Rhythm and conduction abnormalities |

| PQ, ms |

190 [180; 200] |

160 [150; 160] |

0.046 |

| PVCs per day. |

5043 [827; 12 416] |

326 [45; 1677] |

0.086 |

| Non-sustained VT, n (%) |

3 (60) |

4 (40) |

0.427 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) |

4 (80) |

7 (70) |

0.593 |

| Parameters characterizing heart failure |

| NYHA CHF class |

3 [3; 3] |

3 [3; 3] |

0.661 |

| LV EF (EchoCG), % |

47 [30.5; 59] |

46.5 [43; 61.5] |

0.759 |

| LV EF (EchoCG) ≤ 45%, n (%) |

2 (40) |

4 (40) |

0.713 |

| Е/А |

3.6 ± 0.1 |

2.5 ± 0.3 |

0.076 |

| Interventricular septum (EchoCG), mm |

9.8 ± 1.9 |

10.6 ± 2.5 |

0.617 |

| Posterior wall (EchoCG), mm |

10.0 ± 2.2 |

10.2 ± 2.6 |

1.00 |

| LV EDV (EchoCG), ml |

84 [70; 125] |

74 [64; 89.5] |

0.327 |

| RV (EchoCG), cm |

2.5 [2.5; 4.2] |

3.2 [2.8; 3.8] |

0.639 |

| Left atrium (EchoCG), ml |

129 [63; 137.5] |

106 [81; 153] |

0.713 |

| Right atrium (EchoCG), ml |

120 [47.5; 136] |

83 [50.5; 176.5] |

0.739 |

| End points |

| Death, n (%) |

0 |

2 (20) |

0.429 |