1. Introduction

Many systems of contemporary interest are open systems: they interact continuously with environments that cannot be fully observed, controlled, or reset. This is true across technical, physical, biological, and social domains, where systems evolve not in isolation but through ongoing coupling with external conditions, constraints, and disturbances. In such settings, understanding system behavior is less a matter of internal specification and more a matter of how systems participate in the world over time.

Despite this, much reasoning about systems remains snapshot-oriented. Verification, validation, and plausibility are frequently derived from instantaneous measurements, static configurations, or endpoint outcomes. A system is deemed correct if it satisfies a set of conditions at a particular moment, or authentic if it produces an expected output under a prescribed test. These approaches work well in closed or tightly controlled environments, but they degrade as systems become adaptive, distributed, and embedded in complex surroundings.

The limitation of snapshot-based reasoning is not merely practical, but epistemic. Instantaneous states are often cheap to imitate: distinct processes can produce indistinguishable configurations, and identical endpoints can be reached through radically different histories. When observation is limited to what a system is at a moment, rather than how it became that way, essential information about process, interaction, and constraint is discarded.

This work argues that, in open systems, a significant class of evidence does not reside in static states at all. Instead, it resides in the irreversible trajectories systems trace as they progress through reality. These trajectories encode the cumulative effects of internal state, exogenous coupling, and irreversibility in ways that cannot be fully captured by snapshots or endpoints alone. While such information is always present in lived processes, it is often overlooked because it is not treated as a first-class evidentiary object.

The remainder of this paper develops a conceptual synthesis that makes this class of evidence explicit. By shifting attention from instantaneous states to irreversible trajectories, it becomes possible to reason about what systems reveal simply by existing, evolving, and persisting in open environments. This synthesis is introduced not as a new mechanism or law, but as a reframing of where evidence resides and how it becomes observable.

2. The Limits of Snapshot-Based Reasoning

Much of how systems are analyzed, verified, and compared rests on an implicit assumption: that a system’s state at a moment is a sufficient carrier of information about its behavior. Under this view, evidence is something that can be sampled, inspected, or measured instantaneously. If two systems present the same configuration, or produce the same output under a test, they are often treated as equivalent for the purposes of reasoning or decision-making.

This assumption conflates state with process. A state describes what a system is at an instant; a process describes how it changes, interacts, and persists. While states are convenient to observe and compare, they are fundamentally incomplete descriptors of open systems. Processes unfold through irreversible progression, accumulate history, and reflect constraints and interactions that are invisible when observation is reduced to isolated snapshots.

A related limitation appears in the emphasis on endpoints over paths. Many evaluations focus on whether a system reaches an expected outcome, satisfies a terminal condition, or converges to a desired configuration. However, identical endpoints can be reached through profoundly different paths. One system may arrive at an outcome through gradual adaptation and continuous interaction with its environment, while another may arrive through brittle shortcuts, precomputed behavior, or replay. When only the endpoint is considered, these distinctions collapse, and meaningful differences in how the outcome was produced are erased.

Crucially, identical outcomes do not imply identical processes. Two systems may obey the same rules, share the same initial conditions, and produce the same observable results, yet differ radically in how they traversed the space between. These differences matter because they reflect interaction with constraint, exposure to variability, and the accumulation of history. When reasoning is restricted to what can be observed at a single moment, these aspects are systematically excluded.

The consequence is not merely a loss of detail, but a loss of evidentiary depth. By privileging snapshots and endpoints, common modes of reasoning discard information that exists only across sequences of change. In open systems, where history cannot be rewound and environments cannot be fully controlled, this discarded information may be among the most informative signals available. Recognizing this gap is a prerequisite for understanding where additional evidence resides and why it has been overlooked.

3. Stateful Temporal Entropy

3.1. Definition

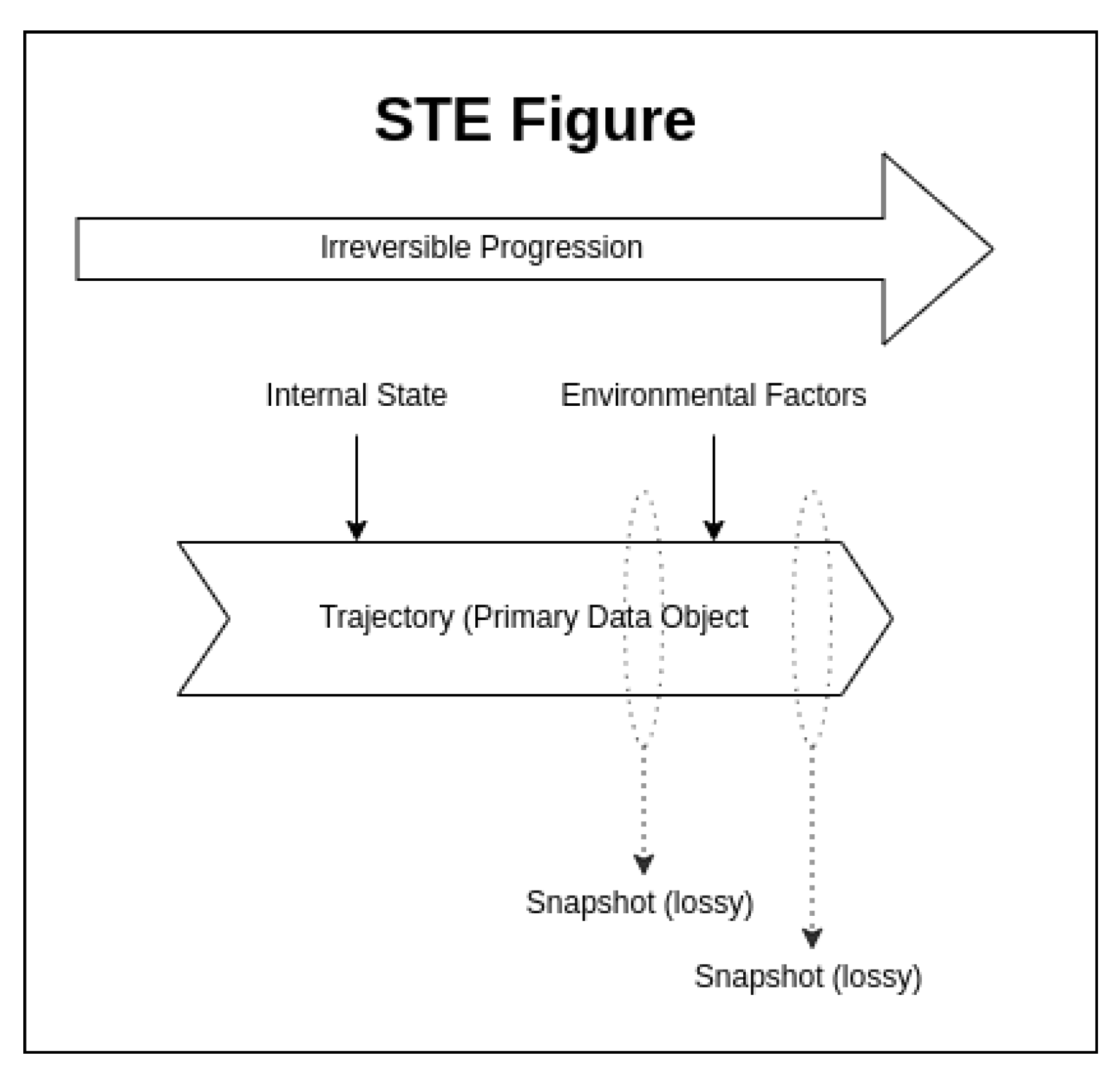

Stateful Temporal Entropy (STE) is introduced as a synthesis that treats a system’s trajectory, rather than its instantaneous state, as a first-class source of observable evidence. In contrast to snapshot-based reasoning, STE concerns how systems evolve under irreversible progression and what that evolution reveals to an external observer. In STE, the trajectory itself is treated as the primary data object; snapshot observations are lossy projections of that trajectory.

At its most compact, STE can be expressed as:

This formulation is intentionally minimal. It does not specify a particular entropy measure, estimator, or implementation. Instead, it captures the central idea that entropy may be extracted from the path a system takes through its space of possible configurations, rather than from any single configuration in isolation.

In this work, entropy is understood as a measure of uncertainty over a distribution of possible system configurations: an expression of how many distinct ways a system could plausibly exist from the perspective of an observer. This interpretation is consistent with classical and information-theoretic notions of entropy, but emphasizes its epistemic role rather than its physical instantiation.

A trajectory, in this sense, is not merely a sequence of states indexed by time. It reflects the combined influence of three factors:

Internal state encompasses history-dependent properties such as memory, inertia, adaptation, or accumulated change. Exogenous coupling refers to interaction with an environment that is not fully observable or controllable by the system itself. Irreversible progression denotes advancement along an ordering parameter that cannot be rewound without loss or hidden reset.

Crucially, the ordering parameter need not be physical clock time. While time is the most common and broadly applicable case, STE generalizes to any parameter that enforces irreversible progression. Examples include distance traversed, energy dissipated, work performed, commitments made, or entropy produced. What matters is not the specific parameter, but that progression along it imposes irreversible constraint.

To make this explicit, STE may be written more generally as:

where:

denotes entropy extracted by an observer.

denotes the path taken as a function of an irreversible ordering parameter s.

s may represent time or any other monotonic, non-reversible progression.

It is important to emphasize that STE is observer-side. The entropy in question is not assumed to be an intrinsic property computed or maintained by the system itself, nor does STE posit a new physical quantity. Instead, STE describes information available to an observer as a consequence of witnessing a system’s irreversible evolution under internal and external constraints. In this framing, entropy is treated not as noise or disorder to be eliminated, but as evidence that accrues through lived process.

STE therefore does not prescribe how trajectories should be measured, compared, or acted upon. Those choices are necessarily domain- and application-specific. STE is foundational in the narrower sense that it identifies where a class of evidentiary information resides and why that information is absent from snapshot-based observations.

Figure 1.

Conceptual structure of Stateful Temporal Entropy. Internal state and environmental factors condition a system’s irreversible trajectory, which is treated as the primary data object. Snapshot observations represent lossy projections of the trajectory and do not fully capture trajectory-level information.

Figure 1.

Conceptual structure of Stateful Temporal Entropy. Internal state and environmental factors condition a system’s irreversible trajectory, which is treated as the primary data object. Snapshot observations represent lossy projections of the trajectory and do not fully capture trajectory-level information.

3.2. Trajectory and Irreversible Progression

In the context of STE, the term trajectory refers not simply to a sequence of states, but to the ordered evolution of a system under constraint. A trajectory captures how a system moves through its space of possible configurations while interacting with internal state and external conditions, accumulating history that cannot be trivially undone. What distinguishes a trajectory from an arbitrary sequence is not continuity alone, but the presence of progression that leaves lasting trace.

Central to this notion is irreversible progression. For a trajectory to carry evidentiary weight, the system must advance along some ordering parameter that cannot be reversed without loss, intervention, or hidden reset. Irreversibility ensures that the path taken matters: earlier interactions constrain later possibilities, and the system’s present configuration encodes information about what has already occurred. Without irreversibility, trajectories collapse into reorderable sequences, and the distinction between process and snapshot dissolves.

Time is the most familiar and broadly applicable irreversible ordering parameter, and it serves as the canonical case in most discussions of trajectories. Systems persist through time, experience events in temporal order, and cannot revisit prior moments without external reconstruction. As a result, many trajectories of interest are naturally parameterized by time, and temporal evolution provides a convenient and intuitive axis along which irreversibility is enforced.

However, time is not fundamental to the concept of trajectory in STE. What matters is not temporal duration itself, but the existence of an ordering parameter that enforces non-reversibility. In different contexts, this parameter may take other forms. Distance traversed, energy dissipated, work performed, material wear, commitments made, or entropy produced can all serve as irreversible progressions along which a system accumulates history. In each case, advancement constrains future behavior and embeds evidence of interaction with the environment.

By generalizing trajectory beyond time, STE avoids conflating temporal indexing with evidentiary content. Two systems observed over the same duration may exhibit vastly different trajectories if one undergoes substantial irreversible progression while the other does not. Conversely, meaningful trajectories may unfold over short temporal windows if irreversible change is rapid. The evidentiary power of a trajectory arises from what is paid to move forward, not from the mere passage of time.

This distinction is critical for understanding why trajectories can serve as evidence in open systems. Irreversible progression forces systems to confront variability, constraint, and uncertainty in ways that cannot be perfectly anticipated or replayed. As a result, the paths systems take encode information about internal structure and external coupling that is absent from instantaneous observations. Trajectories become informative precisely because they are lived under conditions that cannot be rewound or fully controlled.

3.3. What STE Is and Is Not

Because Stateful Temporal Entropy is framed in terms of trajectory, irreversibility, and entropy, it is important to clarify the scope of the synthesis and the claims it does not make. STE is intended as a conceptual reframing of where evidence resides in open systems, not as a new law, mechanism, or decision procedure.

First, STE is not a physical law. It does not introduce new dynamics, conserved quantities, or thermodynamic principles, nor does it modify existing physical theory. While STE is compatible with physical notions of irreversibility and entropy, it does not assert that entropy itself behaves differently or that trajectories obey new rules. Rather, STE concerns how irreversible evolution becomes observable to an external observer, independent of the underlying physical substrate.

Second, STE is not a mechanism. It does not describe how systems generate trajectories, adapt to environments, or accumulate internal state. Questions of causation, control, and implementation lie outside its scope. STE does not explain why a particular trajectory occurs; it explains why the fact that a trajectory occurred at all can carry evidentiary significance. Mechanisms remain domain-specific and are intentionally left unspecified.

Third, STE is not an inference rule or decision procedure. It does not prescribe how observed trajectories should be evaluated, compared, or acted upon, nor does it specify thresholds, classifications, or outcomes. Any inference drawn from trajectory-based evidence necessarily depends on additional assumptions, models, or objectives introduced by a particular application. STE identifies what becomes observable; it does not dictate what conclusions must follow.

Instead, STE is a synthesis and an interpretive lens. It unifies ideas from trajectory-based reasoning, irreversibility, and entropy into a coherent way of understanding how evidence arises in open systems. By shifting attention from instantaneous states to irreversible evolution, STE reframes entropy as observer-side information embedded in lived process. Its contribution lies in making this class of evidence explicit and in clarifying why it is systematically absent from snapshot-based reasoning.

In this sense, STE operates at a conceptual level above mechanisms and below applications. It neither replaces domain-specific models nor competes with existing analytical tools. Rather, it provides a foundation upon which such tools can be interpreted, contextualized, or extended when reasoning about systems whose histories cannot be ignored.

4. Relationship to Existing Concepts

Stateful Temporal Entropy intersects with several established concepts that address history, dynamics, or variability in systems. However, these concepts differ from STE in both purpose and framing. Clarifying these distinctions is essential for understanding STE as a synthesis concerned with evidence and observability, rather than with mechanism, prediction, or identity.

4.1. Hysteresis: Mechanism Versus Evidence

Hysteresis describes systems whose responses depend on their history, such that identical inputs can produce different outputs depending on prior states. It is a mechanistic concept, concerned with internal memory, lag, or state retention within a system. Hysteresis explains why systems fail to retrace their behavior when external conditions are reversed.

STE neither replaces nor competes with hysteresis. Instead, it operates at a different level. Where hysteresis explains a cause of path dependence, STE explains how the resulting path dependence becomes observable evidence. A system may exhibit hysteresis, but STE is not concerned with modeling that behavior internally; it is concerned with what an observer can infer from the fact that such behavior unfolds irreversibly. Hysteresis shapes trajectories, but STE interprets trajectories.

4.2. Chaos and Nonlinear Dynamics: Behavior Versus Observability

Chaos theory and nonlinear dynamics study systems that exhibit sensitive dependence on initial conditions, complex trajectories, and unpredictable long-term behavior. These frameworks are primarily descriptive and predictive, focusing on how systems evolve given specific rules and parameters.

STE does not seek to characterize or predict system behavior in this sense. Instead, it asks a different question: what information becomes available to an observer as a consequence of irreversible evolution, regardless of whether the underlying dynamics are chaotic, stochastic, or stable? A system need not be chaotic for its trajectory to carry evidentiary weight, nor does chaotic behavior automatically imply evidentiary value. STE is agnostic to the source of complexity; it concerns the epistemic consequences of lived trajectories.

4.3. Classical Entropy: Measurement Versus Epistemic Role

In classical thermodynamics and information theory, entropy is typically treated as a measurable quantity associated with disorder, uncertainty, or the number of accessible microstates. In these contexts, entropy is often something to be minimized, controlled, or compensated for.

STE does not redefine entropy, nor does it propose a new entropy measure. Instead, it repositions entropy in an epistemic role. Within STE, entropy is not merely noise or loss, but information made available to an observer through irreversible evolution. The emphasis is not on the magnitude of entropy in isolation, but on how entropy accrues across trajectories and thereby distinguishes processes that may appear identical at individual moments.

4.4. Behavioral Analysis and Fingerprinting: Identity Versus Trajectory

Behavioral analysis and fingerprinting techniques attempt to identify or classify systems based on patterns of observed behavior. These approaches are often identity-centric, aiming to determine whether an observed entity matches a known profile or deviates from expected behavior.

STE differs in both scope and intent. It is not concerned with identifying who or what a system is, but with understanding what becomes observable when a system is forced to evolve under irreversible conditions. Behavioral fingerprints may be derived from trajectories, but STE itself does not assume the existence of stable identities, templates, or classes. Instead, it focuses on the structural properties of trajectories as evidence, leaving questions of classification or attribution to downstream methods.

Taken together, these distinctions position STE as neither a replacement for existing theories nor a competitor to established analytical tools. Rather, STE provides a conceptual layer above mechanisms and models, clarifying how irreversible evolution gives rise to observable evidence in open systems. By separating questions of behavior, identity, and dynamics from questions of observability and evidence, STE complements existing frameworks while addressing a gap they do not explicitly target.

5. Beyond Time: Generalizing the Ordering Parameter

Discussions of trajectories are often implicitly tied to time. Systems evolve over time, histories unfold in time, and irreversibility is frequently described as an arrow of time. While temporal progression is the most familiar and broadly applicable ordering parameter, STE does not treat time itself as fundamental. Instead, STE rests on a more general requirement: irreversible ordering.

An irreversible ordering parameter is any parameter along which progression cannot be reversed without loss, external intervention, or hidden reset. Advancement along such a parameter constrains future possibilities and embeds information about past interaction. It is this constraint, rather than temporal duration per se, that gives trajectories their evidentiary power.

Time serves as the canonical ordering parameter because most real systems persist in time and cannot revisit prior moments. However, many systems accumulate history and constraint through other forms of irreversible progression. Distance traversed cannot be undone without retracing effort. Energy dissipated cannot be fully recovered. Work performed leaves wear, heat, or deformation. Commitments made, whether physical, computational, or social, restrict future options and cannot be withdrawn without additional cost. In each case, progression imposes irreversible change that shapes the system’s trajectory.

From the perspective of STE, these parameters are interchangeable in principle. What matters is not which parameter is used, but whether progression along it forces the system to engage with constraints and variability it cannot fully anticipate or control. A system that advances rapidly along an irreversible parameter may accumulate significant trajectory evidence over a short temporal interval, while another may persist for long periods with little irreversible change. The evidentiary content of a trajectory therefore depends on what is expended to move forward, not merely on how long movement takes.

This distinction clarifies why irreversibility, rather than time, is the fundamental ingredient. Reversible sequences can be reordered, replayed, or compressed without loss of information. Irreversible sequences cannot. Once progression consumes resources, commits state, or dissipates energy, the path taken becomes informative precisely because it cannot be freely reconstructed. Trajectories acquire structure and diversity only when advancement has a cost that cannot be refunded.

Within this framing, the term temporal in Stateful Temporal Entropy should be understood broadly. It denotes ordered progression, not exclusively clock time. Temporal ordering provides the most intuitive instance of irreversibility, but STE explicitly generalizes beyond it to encompass any monotonic progression that enforces history dependence. This interpretation preserves the intuition associated with temporality while avoiding unnecessary restriction to a single dimension.

By decoupling trajectory from time alone, STE remains applicable across domains where evidence emerges through irreversible change rather than prolonged duration. This generalization is essential to the synthesis: it ensures that STE captures a structural property of open systems, not an artifact of temporal indexing. Trajectories become evidentiary not because they unfold slowly, but because they unfold irreversibly.

6. When Trajectories Become Evidence

To treat trajectories as evidence requires first clarifying what evidence means in the context of open systems. Evidence is not simply data, measurement, or observation in isolation. Rather, evidence is information that constrains plausible explanations of how a system behaves or participates in its environment. Evidence reduces uncertainty not by asserting correctness, but by narrowing the space of processes that could reasonably have produced what is observed.

Snapshot-based observations fail in this regard because they are epistemically thin. An instantaneous state may be accurate, measurable, and verifiable, yet remain compatible with a wide range of underlying processes. Distinct histories, interactions, and constraints can collapse into indistinguishable configurations when viewed at a single moment. In such cases, correctness of the snapshot provides little insight into how the system arrived there or what it has endured.

Trajectories differ fundamentally. A trajectory represents an ordered sequence of change under irreversible progression, shaped by internal state and exogenous coupling. As such, it accumulates information across transitions that cannot be compressed into any single observation. The structure, variability, and contingency of a trajectory reflect not what a system is capable of producing, but what it has been forced to accommodate along the way. This accumulated structure is what allows trajectories to function as evidence.

Importantly, the evidentiary value of a trajectory does not arise from its length or complexity alone, but from the constraints under which it unfolds. Because irreversible progression cannot be freely replayed or reordered, the path taken embeds information about interaction with conditions that were not fully predictable or controllable. In this sense, trajectories encode exposure to reality. They carry traces of adaptation, resistance, compromise, and persistence that snapshots systematically omit.

This distinction highlights the difference between plausibility and correctness. Snapshot-based reasoning often evaluates whether a system satisfies a condition or produces an expected output, treating correctness as the primary criterion. Trajectory-based evidence instead speaks to plausibility: whether the observed evolution of a system is consistent with having genuinely participated in the conditions it purports to represent. A system may be correct at a moment while remaining implausible as the product of an authentic process. Trajectories provide the information needed to make this distinction visible.

Crucially, recognizing trajectories as evidence does not require committing to any particular inference, classification, or decision. Observation and inference are distinct epistemic acts. STE is concerned solely with the former: identifying a class of observable information that arises from irreversible evolution and explaining why it is evidentially meaningful. How that evidence is interpreted, weighted, or acted upon necessarily depends on context, goals, and models external to STE itself.

In this framing, trajectories become evidence not because they guarantee truth, but because they impose cost on explanation. To account for a lived trajectory requires explaining how a system navigated constraint over irreversible progression. This explanatory burden is precisely what snapshots avoid, and what makes trajectory-based evidence difficult to fabricate, compress, or substitute. STE formalizes this intuition by treating the entropy of irreversible trajectories as observer-side information, elevating what has long been implicit in lived processes into an explicit epistemic category.

7. Illustrative Applications

The preceding sections introduce STE as a general synthesis concerned with how irreversible trajectories become observable evidence. To clarify the breadth of this framing without narrowing it to a specific domain, this section presents several illustrative contexts in which trajectory-based evidence naturally arises. These examples are not intended as implementations, detection mechanisms, or prescriptions. Rather, they demonstrate that STE identifies a class of observable structure that already exists across diverse systems and that may be acted upon by downstream logic appropriate to each domain.

7.1. Physical Entropy Sources and Traversal-Based Observation

Physical systems have long been used as sources of entropy precisely because they are difficult to model, control, or reproduce. Traditional approaches often rely on instantaneous measurements of such systems, such as sampling a configuration, capturing a frame, or reading a sensor value, and treat that snapshot as a source of randomness.

From an STE perspective, the evidentiary content of physical entropy sources does not reside solely in isolated observations, but in the trajectory of physical evolution itself. When a system is observed over a traversal involving irreversible physical change, such as fluid motion, thermal variation, or material deformation, the resulting trajectory reflects cumulative interaction with uncontrollable environmental factors. The ordering, timing, and structure of these changes encode information that cannot be reduced to any single measurement.

STE does not claim that such trajectories are inherently random, nor does it prescribe how entropy should be extracted from them. It clarifies only that irreversible physical evolution exposes observer-side information that snapshot-based sampling obscures. How that information is harvested, quantified, or used remains a separate, domain-specific concern.

7.2. Cyber and Cyber-Physical Systems

In cyber and cyber-physical systems, many interactions unfold as sequences of observation rather than isolated events. Systems often progress through stages of discovery, negotiation, selection, or adaptation before any durable commitment is made. These stages frequently involve interaction with environments that evolve independently of the observing system.

Viewed through the lens of STE, such stages constitute trajectories: ordered sequences of interaction constrained by protocol rules, environmental conditions, and irreversible progression. The structure of these trajectories, including variability across observations, responsiveness to changing conditions, or conformity to surrounding dynamics, may carry evidentiary content that is absent from any single message, measurement, or endpoint state.

STE does not assert that any particular protocol state is sufficient to draw conclusions, nor does it assign meaning to specific behaviors. Instead, it highlights that pre-commitment evolution itself produces observable structure. Downstream logic, whether analytical, heuristic, or policy-driven, may choose to act on that structure, but STE’s role is limited to identifying where such evidence exists.

7.3. Provenance and Forensic Reasoning

Provenance and forensic disciplines routinely rely on the idea that processes leave traces. Whether examining physical artifacts, digital records, or chains of custody, these fields treat the accumulation of irreversible change as informative about origin, handling, and interaction.

STE provides a unifying perspective on this intuition. Rather than focusing on any specific trace or artifact, STE frames provenance as a property of trajectories through constrained environments. Wear patterns, temporal ordering of events, material degradation, and contextual inconsistencies all arise from irreversible progression and cannot be fully reconstructed from final states alone.

Importantly, STE does not replace forensic methodology or establish criteria for attribution. It clarifies why provenance is epistemically meaningful in the first place: because explaining a trajectory requires accounting for a sequence of interactions that could not have been freely rearranged or replayed. Forensic conclusions remain inferential and contextual; STE explains why trajectories supply the evidence on which those inferences depend.

7.4. Socio-Technical Systems

Socio-technical systems, such as markets, organizations, or large-scale platforms, exhibit dynamics that are neither purely technical nor purely social. Actions accumulate commitments, exhaust options, and impose constraints that persist beyond individual decisions.

In such systems, trajectories arise through irreversible progressions such as resource expenditure, reputational change, institutional commitment, or coordination overhead. These trajectories encode information about participation, exposure to uncertainty, and adaptation to collective dynamics. A snapshot of a system’s current state may obscure these factors, while its trajectory reveals the cost and structure of its evolution.

STE does not attempt to formalize social behavior or predict outcomes. It highlights that socio-technical processes produce evidentiary structure through irreversible progression, and that this structure exists independently of any particular interpretive framework. Decisions about trust, legitimacy, or robustness belong to social, economic, or organizational analysis, not to STE itself.

Taken together, these examples illustrate that STE does not introduce new phenomena into these domains. Instead, it provides a common language for understanding why trajectories across disparate systems carry evidentiary content that snapshots do not. In each case, STE reveals observable structure created by irreversible interaction with environment and constraint. What downstream systems choose to do with that structure, whether nothing at all or something consequential, is necessarily a separate question.

8. Limitations and Non-Goals

As a conceptual synthesis, Stateful Temporal Entropy is intentionally scoped. Clarifying what STE does not attempt to do is essential for interpreting its role correctly and for avoiding misapplication.

First, STE does not prescribe decisions. It does not specify thresholds, classifications, policies, or actions, nor does it determine how observed evidence should be weighted or resolved. STE identifies a class of observable information arising from irreversible trajectories, but the interpretation and use of that information necessarily depend on domain-specific objectives, constraints, and risk tolerances that lie outside the synthesis itself.

Second, STE does not guarantee inference correctness. Trajectory-based evidence may reduce the space of plausible explanations, but it does not eliminate uncertainty or error. Observations may be incomplete, noisy, or misleading, and multiple inferences may remain consistent with the same trajectory. STE is therefore epistemic rather than prescriptive: it clarifies what information becomes available, not whether a particular conclusion drawn from that information is correct.

Third, STE can fail in closed, resettable, or fully replayable systems. When systems can be rewound without cost, reset to prior states, or isolated from exogenous influence, irreversible progression is absent or suppressed. In such settings, trajectories lose evidentiary depth, and snapshot-based reasoning may be sufficient. STE is explicitly concerned with open systems in which progression imposes irreversible constraint; where that condition does not hold, STE offers limited advantage.

Finally, STE complements rather than replaces domain-specific methods. It does not substitute for physical modeling, statistical analysis, protocol design, cryptographic mechanisms, or social theory. Instead, STE operates upstream of such methods, providing a way to recognize and reason about a class of evidence that those methods may later exploit, formalize, or ignore. Domain expertise remains necessary to determine how trajectory-based evidence should be incorporated into any concrete system.

These limitations are not deficiencies but reflections of STE’s intended role. By remaining agnostic to mechanism, inference, and application, STE preserves its generality and avoids conflating observability with decision-making. Its contribution lies in clarifying where evidence can arise in open systems, not in dictating how that evidence must be used.

9. Conclusion

This work has argued for a shift in how evidence is understood in open systems: from what systems are at a moment to how they become what they are through irreversible progression. Snapshot-based reasoning, while convenient and often sufficient in closed settings, systematically discards information that exists only across sequences of change. When systems cannot be fully observed, controlled, or reset, that discarded information may be among the most informative signals available.

Stateful Temporal Entropy reframes this observation by treating trajectories as first-class evidentiary objects. By focusing on irreversible evolution shaped by internal state and exogenous coupling, STE identifies a class of observer-side information that cannot be reduced to instantaneous measurements or endpoint outcomes. The evidentiary value of a trajectory arises not from duration or complexity alone, but from the constraints imposed by irreversibility, which force systems to accumulate history that cannot be freely replayed or compressed.

Crucially, STE does not prescribe how such evidence must be interpreted or acted upon. Its role is prior to inference and decision-making. By clarifying where evidence resides and why it becomes observable, STE provides a conceptual foundation upon which domain-specific reasoning may build, without constraining the form that reasoning must take. In this way, STE remains agnostic to mechanism, application, and outcome, while offering a unifying perspective across diverse systems.

The contribution of this synthesis is therefore not a method or a result, but a lens. It explains why lived processes leave traces that matter, why those traces resist substitution, and why reasoning that ignores them is necessarily incomplete. When trajectories are recognized as evidence, the question is no longer whether systems appear correct at a moment, but what their evolution reveals simply by having occurred.

References

- Claude E. Shannon. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 379–423, 1948

. [CrossRef]

- Edwin T. Jaynes. Probability Theory: The Logic of Science. Edited by G. Larry Bretthorst. Cambridge University Press, 2003 .

- Isaak D. Mayergoyz. Mathematical Models of Hysteresis. Academic Press, 2003 .

- Luc Moreau and Paolo Missier, editors. PROV-DM: The PROV Data Model. W3C Recommendation, 2013.

- Udo Seifert. Stochastic thermodynamics, fluctuation theorems and molecular machines. New Journal of Physics, vol. 17, 065001, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Lennart Dabelow, et al. Irreversibility in Active Matter Systems: Fluctuation Theorem and Mutual Information. Physical Review X, vol. 9, no. 2, 13 June 2018.

- Golan, Amos, and John Harte. Information Theory: A Foundation for Complexity Science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 119, no. 33, 27 July 2022.

- Luan Orion Barauna, et al. Characterizing Complex Spatiotemporal Patterns from Entropy Measures. Entropy, vol. 26, no. 6, 12 June 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).