1. Introduction

Breast cancer has emerged as a significant concern for women globally, with 2.26 million reported cases in 2020, surpassing all other forms of cancers and becoming the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women [

1,

2]. The number of new cases in the United States had increased by 31% in 2023 [

3]. Despite advancements in cancer diagnosis and treatment, the development of chemotherapeutic drugs continues to be intensively researched [

4,

5]. Plants have been used for medicinal purposes for centuries, and many plant species contain chemical compounds that have exhibited potent effects in cancer treatment [

6]. Plant secondary metabolites with anticancer properties, such as alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenolics may provide a broad range of therapeutic benefits [

7,

8,

9]. Recent research suggests that phytochemicals could have various therapeutic effects, such as preventing tumor growth by activating several cellular signaling pathways and targeting specific receptors [

10,

11,

12,

13]. One of the well-known receptors that can be activated by phytochemicals is the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptor. TRPV1 receptors are ion channels belonging to the TRP channel superfamily, modulated by several phytochemicals and activating several cell death signaling pathways, thus exhibiting antiproliferative effects [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The TRPV1 channel is a non-selective cation channel primarily linked to pain and temperature sensation [

19]. However, recent data suggests that TRPV1 is associated with various physiological and pathological processes, including cancer [

14,

20,

21,

22], and is expressed in different carcinoma tissues, including all types of breast cancers [

23]. Various plant phytochemicals, including capsaicin, gingerol, piperine, and resiniferatoxin (RTX), are the commonly known activators of the TRPV1 channel [

17,

20]. In cancer cells, TRPV1 activation leads to an influx of calcium, initiating subsequent signaling cascades and triggering antiproliferative effects [

14,

24,

25]. Further study is required to fully understand the potential of phytochemicals targeting TRPV1 in cancer therapy.

One genus known to have antiproliferative effects is

Euphorbia (

Euphorbiaceae). Many species of

Euphorbia are used in traditional folk medicine to treat different diseases [

26] and have been extensively studied because of their wide range of biological activities, including antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic properties [

27,

28,

29].

Euphorbia species, such as

E. helioscopia, and

E. macroclada, have been found to possess anticancer properties by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, inhibiting cell proliferation, and reversing the multidrug resistance of different breast cancer cell lines [

30,

31,

32,

33].

Euphorbia bicolor, also known as Snow-on-the-prairie, is native to south-central USA. No scientific research has been done on this species. Our previous research found that the latex extract of

E. bicolor and its phytochemicals showed antiproliferative properties in ER-positive MCF-7 and T47D, as well as triple-negative MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-469 breast carcinomas, but the mechanisms of action were not determined [

32].

The present investigation aims to determine the antiproliferative mechanisms of action of

E. bicolor diterpene extract on ER-positive T47D and triple-negative MDA-MB-231 cell lines. Resiniferatoxin, a common diterpene present in

E. bicolor [

29], was reported to activate the TRPV1 channel in neurons and cancer cells [

34,

35]. We hypothesized that

E. bicolor diterpene extract would activate TRPV1 and induce TRPV1-dependent antiproliferative mechanisms of action in the breast cancer cell lines. We report that

E. bicolor diterpene extract possesses antiproliferative properties in both breast cancer cell lines under study and induces apoptosis through multiple cell death pathways. To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the antiproliferative mechanisms of action of

E. bicolor diterpene extract on ER-positive T47D and triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines.

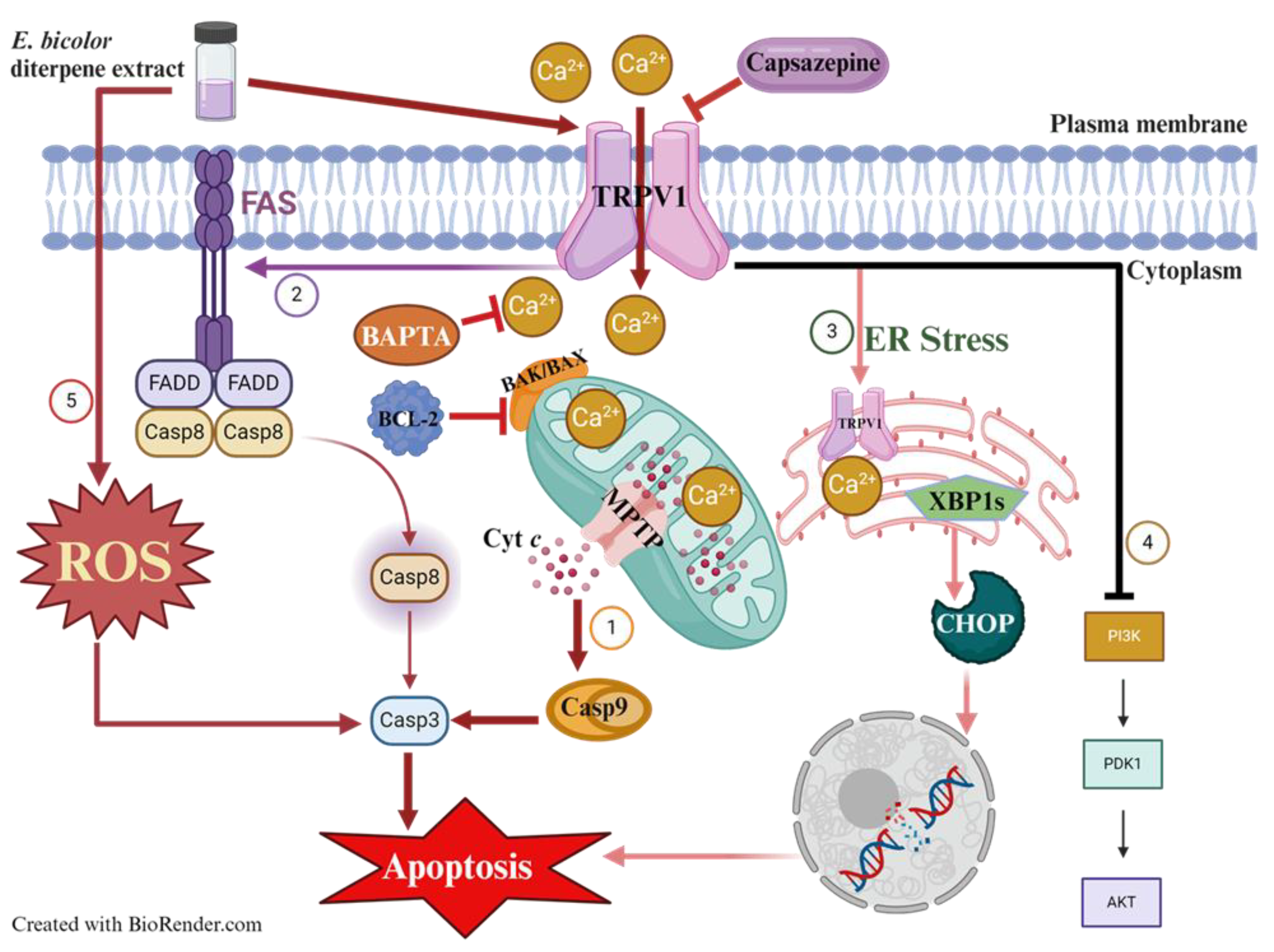

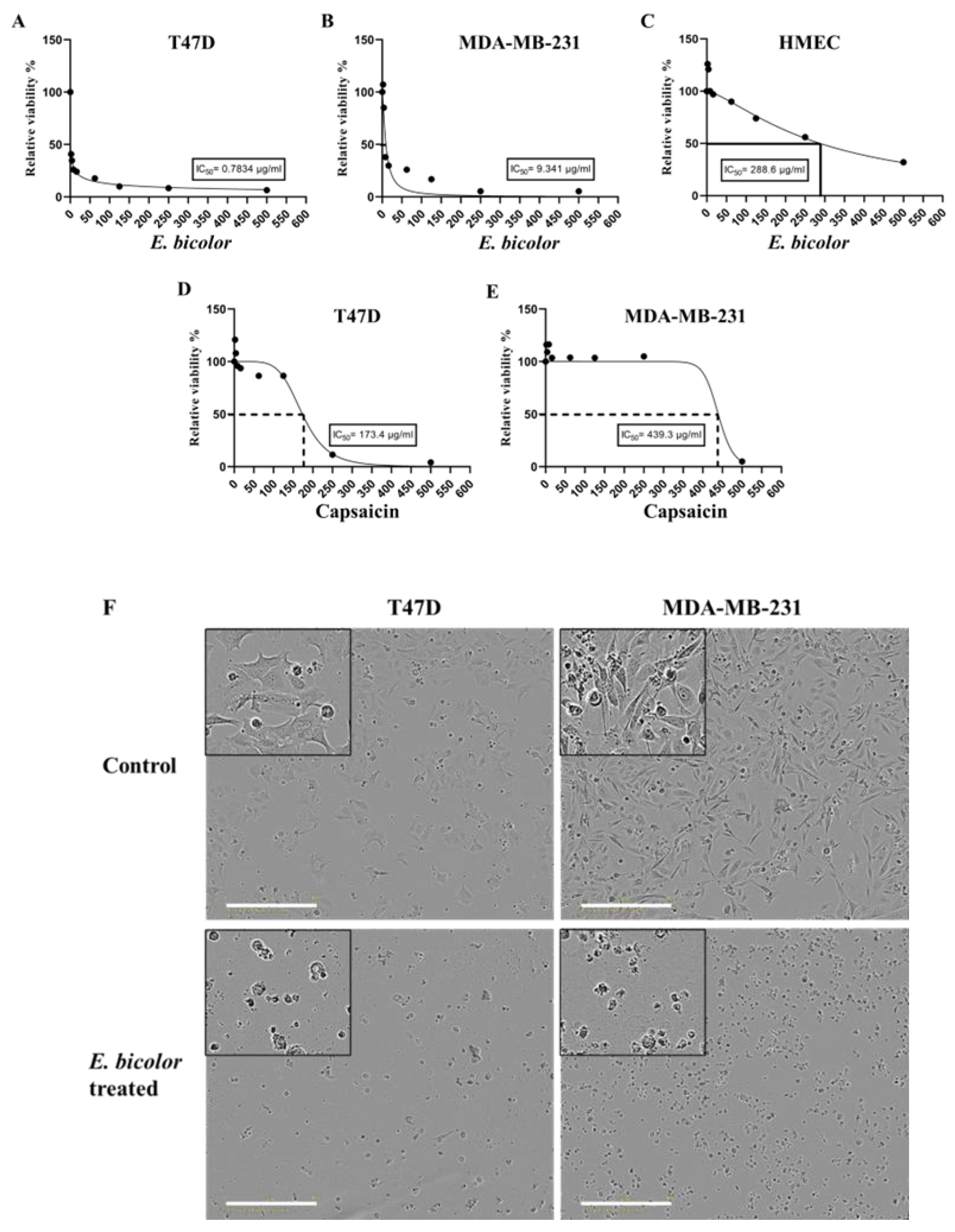

3. Discussion

Worldwide, breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women [

38]. To reduce the global death rate from breast cancer, advances in diagnosis and treatment must be widened. Numerous plant species contain natural substances with anti-cancer properties [

39]. Conducting focused research on bioactive plant chemicals, scientists could develop novel therapeutic options for breast cancer treatment. The present study tested the antiproliferative activities of

E. bicolor diterpene extract on ER-positive T47D and triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines and found that the extract significantly reduced the proliferation of both breast cancer cell lines (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). It was previously reported that

E. bicolor latex extract possesses antiproliferative activity on T47D and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines [

32], but no mechanisms of action were provided. This study proposes the mechanisms of action of

E. bicolor diterpene extract in the two cell lines under study presented in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11.

Plants of

Euphorbia genus are well-known for their antiproliferative effects.

E. hirta methanolic extract suppressed MCF-7 cell growth at 24 h with a GI50 value of 25.26 µg/mL [

40]. A study on the effect of

E. macroclada acetone extract made from leaves and flowers reported significant cytotoxicity in MCF-7 breast cancer cells [

41]. Another study showed that dichloromethane and ethyl acetate extracts of

E. macroclada exhibited cytotoxic effects on MDA-MB-468 cells. In contrast, the methanol and latex extracts in DMSO were not cytotoxic at the concentrations used [

33]. Butanol, hexane, and methanol extracts of

E. tirucalli stem inhibited the proliferation of MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 in a concentration-dependent manner [

42]. Our study found that

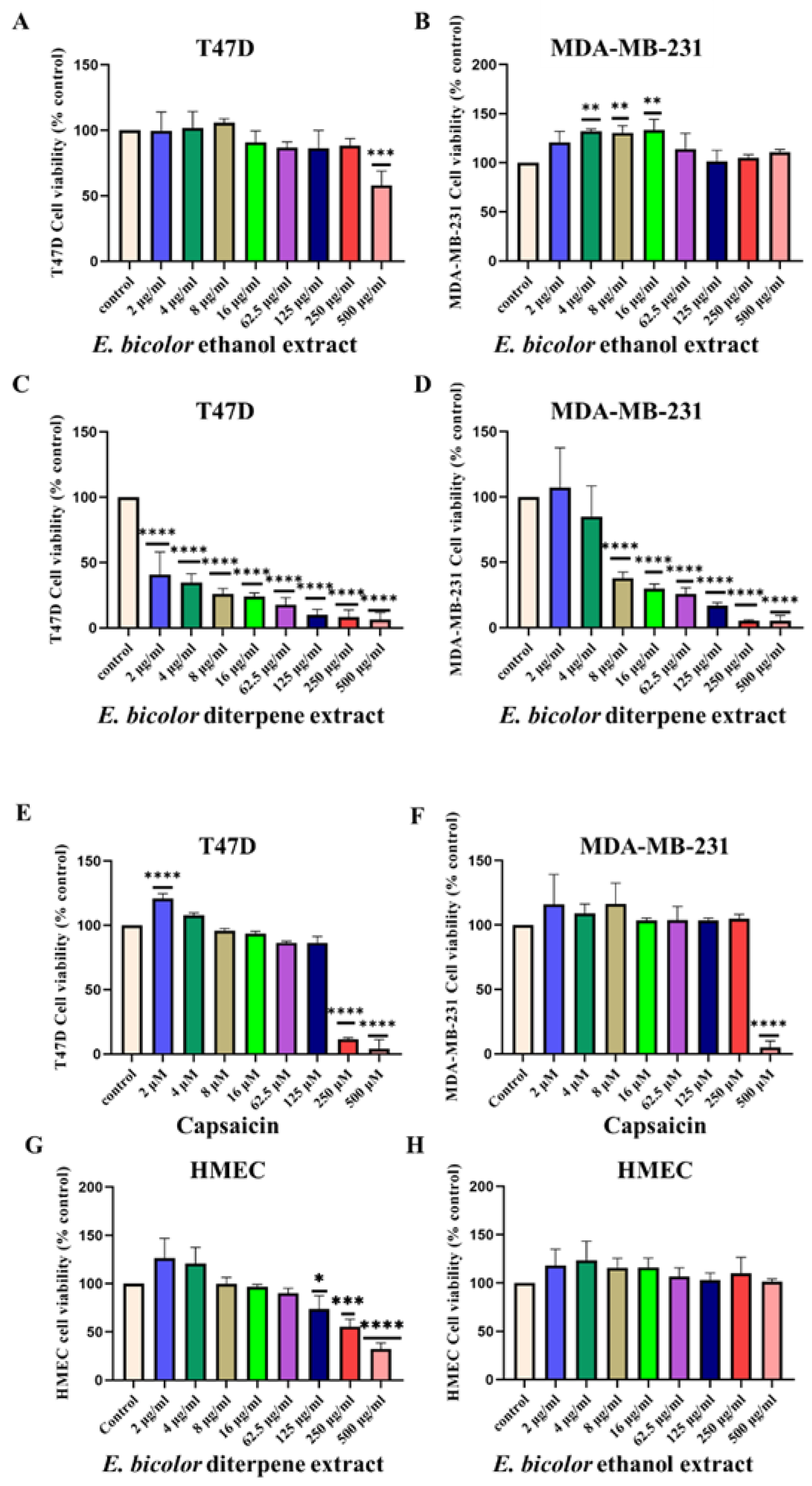

E. bicolor ethanol extract possesses antiproliferative effects only at higher concentrations in ER-positive T47D cells. However, no antiproliferative effect was observed on the triple-negative MDA-MB-231 cells (

Figure 1). Different solvent extracts of

Euphorbia species, as well as extract concentration used, show a wide range of antiproliferative effects in breast cancer cell lines.

Compared to

E. bicolor ethanol extract, the diterpene extract was toxic to HMEC at high concentrations. Previous research showed that the diterpene RTX was not toxic to normal cells [

32,

43,

44]. However,

E. bicolor diterpene extract contains other diterpenes besides RTX. Biochemical identification results from our lab, previously published, showed that

E. bicolor latex extract contains the diterpenes RTX, and abietic acid [

29]. The HMEC cytotoxicity may be a combined effect of RTX, abietic acid, and other diterpenes in the extract. Therefore, future research should focus on chemical identification and isolation of other diterpenes in

E. bicolor extracts, to individually be used to study antiproliferative effects, thus selecting the nontoxic ones for possible drug development.

In our attempt to understand the antiproliferative mechanisms of action of

E. bicolor diterpene extract in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells, we considered the activation of TRPV1, calcium influx, and apoptotic markers. As calcium ions are secondary messengers in cells, maintaining the balance of Ca

2+ is crucial for regulating many cellular functions, including processes relevant to tumor growth and development, such as apoptosis and metastasis [

43,

44]. TRPV superfamily of plasma membrane ion channels is one of the most active calcium-permeable superfamily in regulating Ca

2+ influx [

14,

25]. Experimental evidence shows that capsaicin can activate TRPV1 in cancer cells and have potent anticancer activity against certain cancer types through both Ca

2+-dependent and -independent mechanisms [

44,

45]. In our study, capsaicin showed antiproliferative activity in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells at much higher concentrations than

E. bicolor diterpene extract, which may be because the extract contains various diterpenes, and they may synergistically work to induce the observed antiproliferative effects.

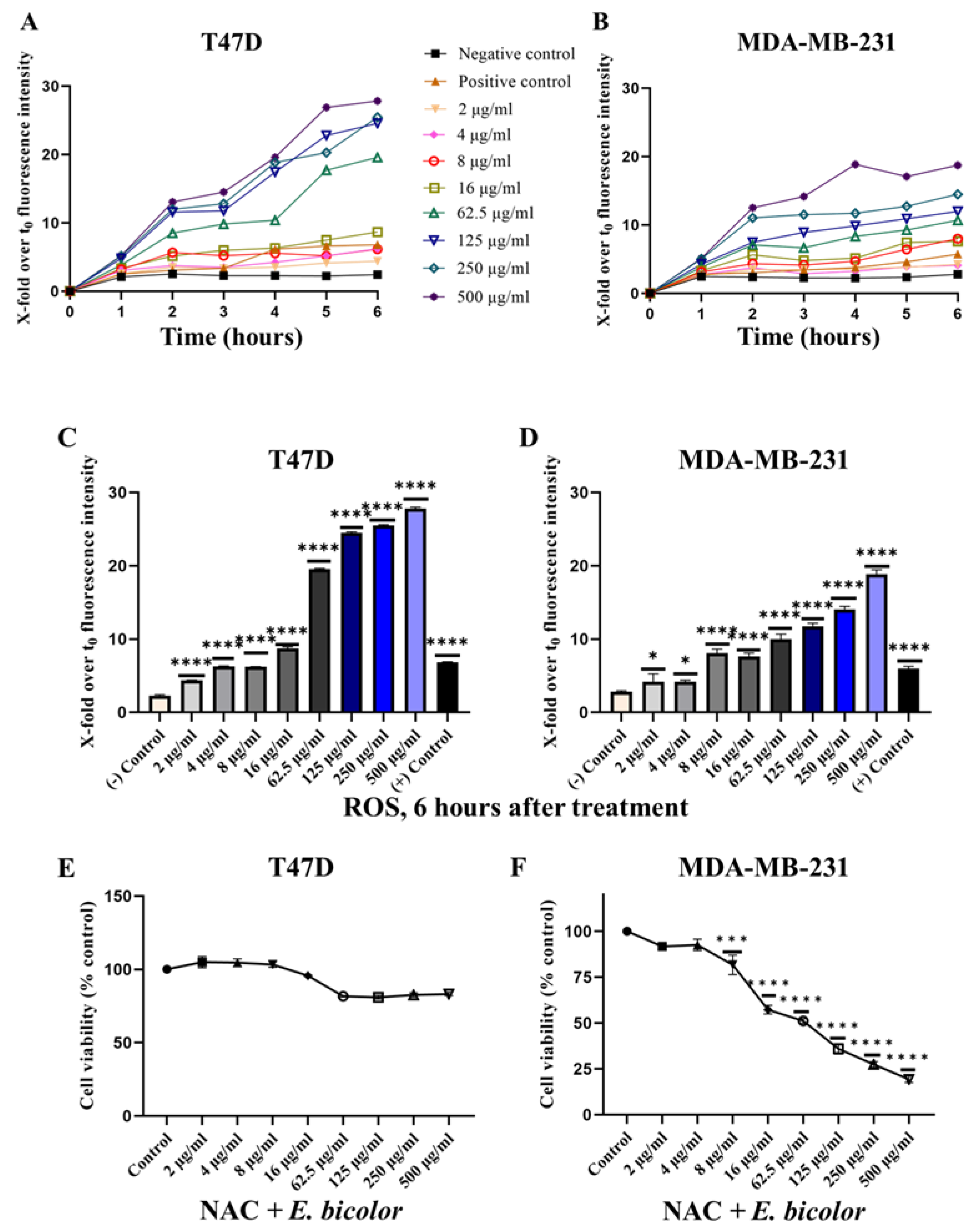

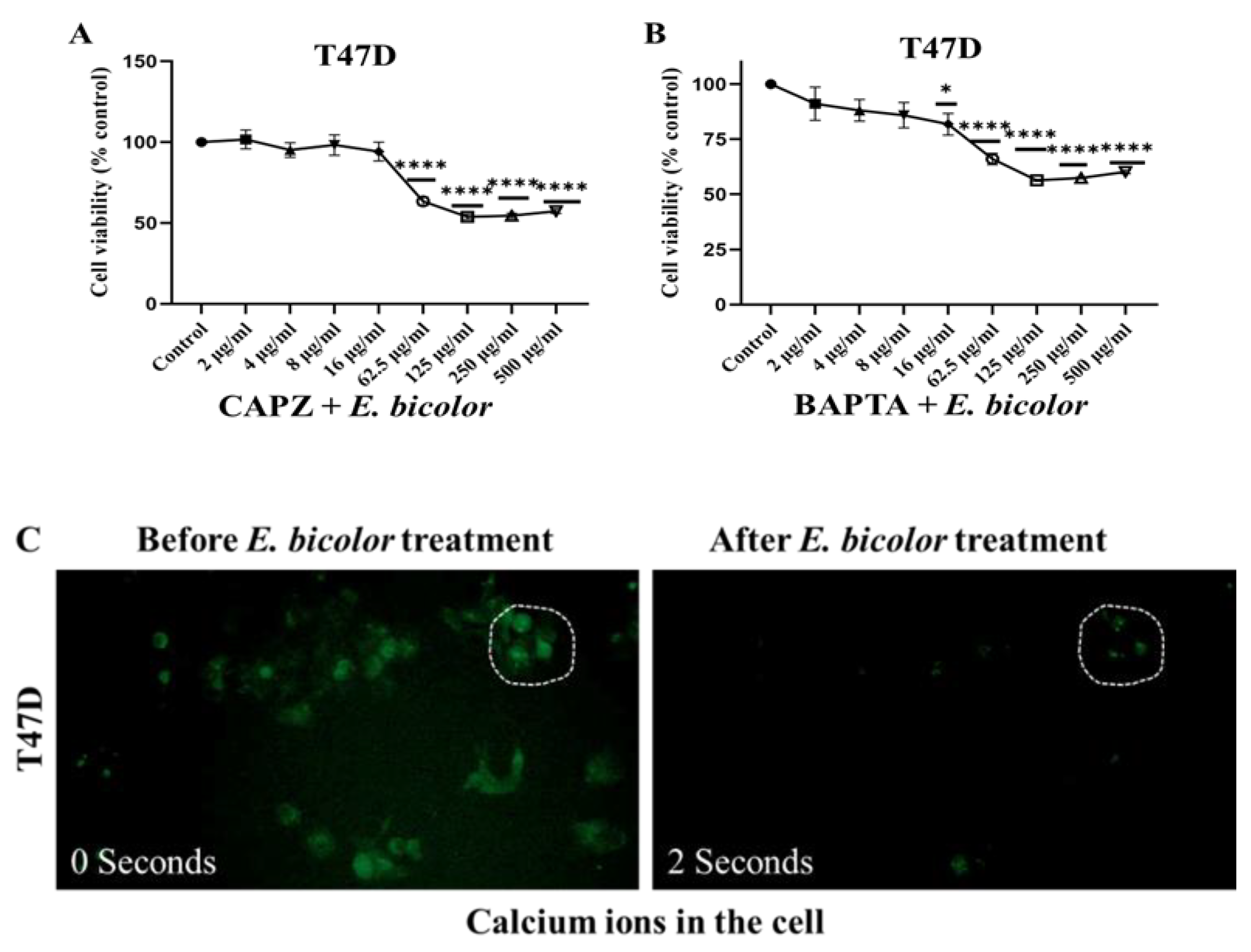

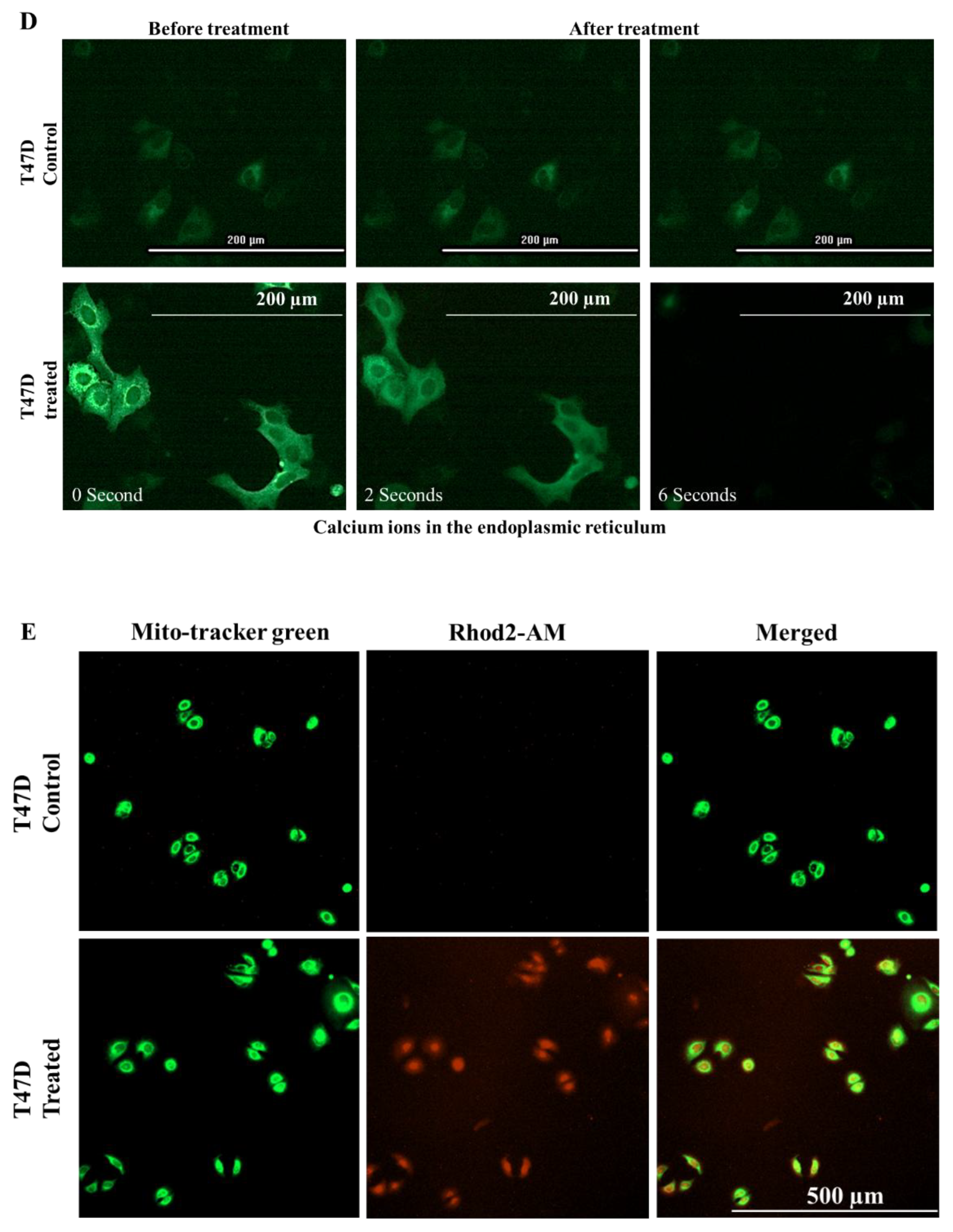

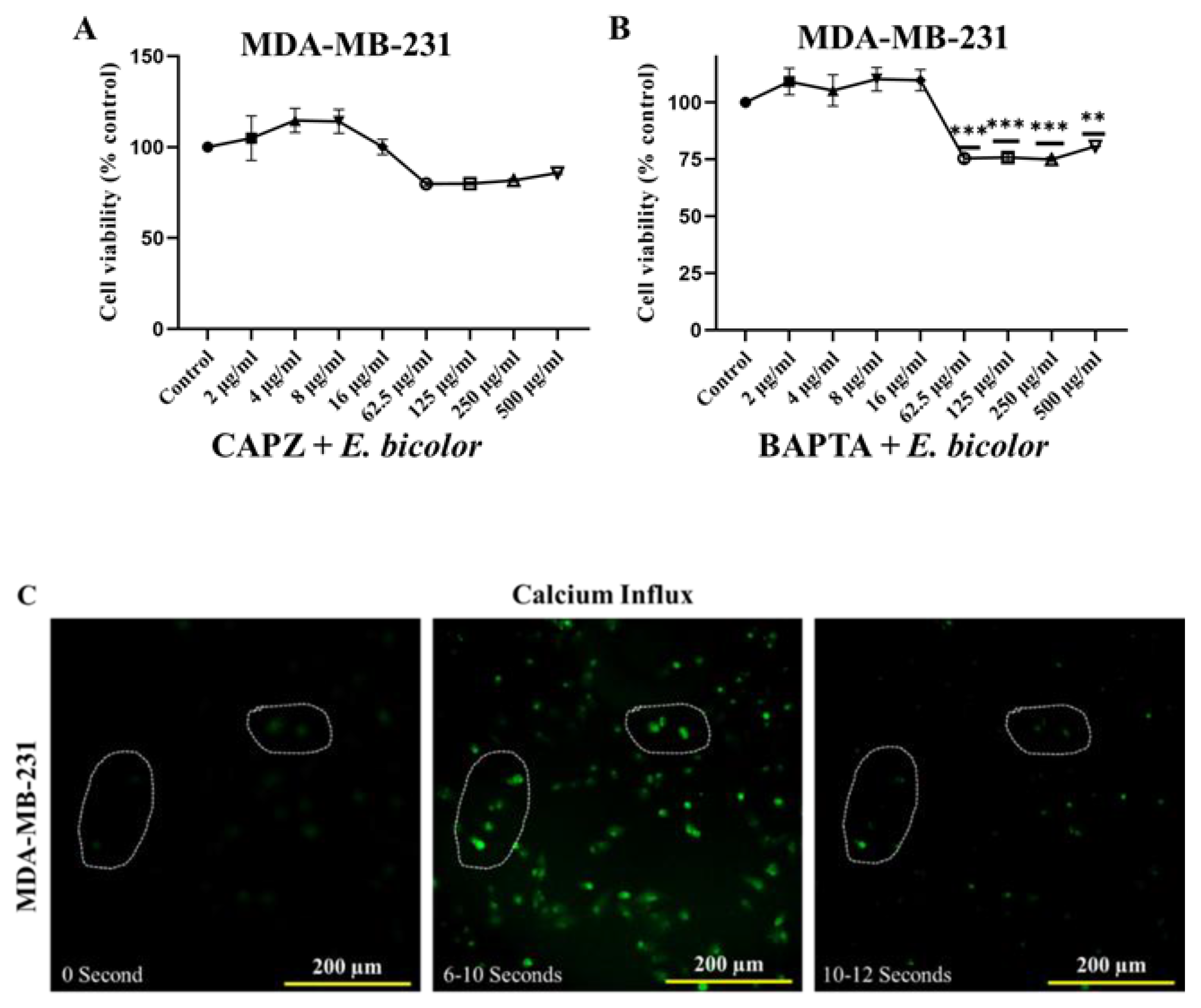

Blocking TRPV1 and chelating calcium increased the T47D and MDA-MB-231 cell viability but did not completely counteract the effect of

E. bicolor diterpene extract. On the other hand, inhibiting ROS formation with NAC completely blocked the effect of

E. bicolor diterpene extract resulting in increased cell viability of only T47D cells, suggesting that increased ROS level is the underlying mechanism of cell death in T47D cells. Other antiproliferative studies employing

Euphorbia species, such as

E. lathyris,

E. antiquorum, and

E. fischeriana, have also found that increased ROS levels induced apoptosis [

46,

47,

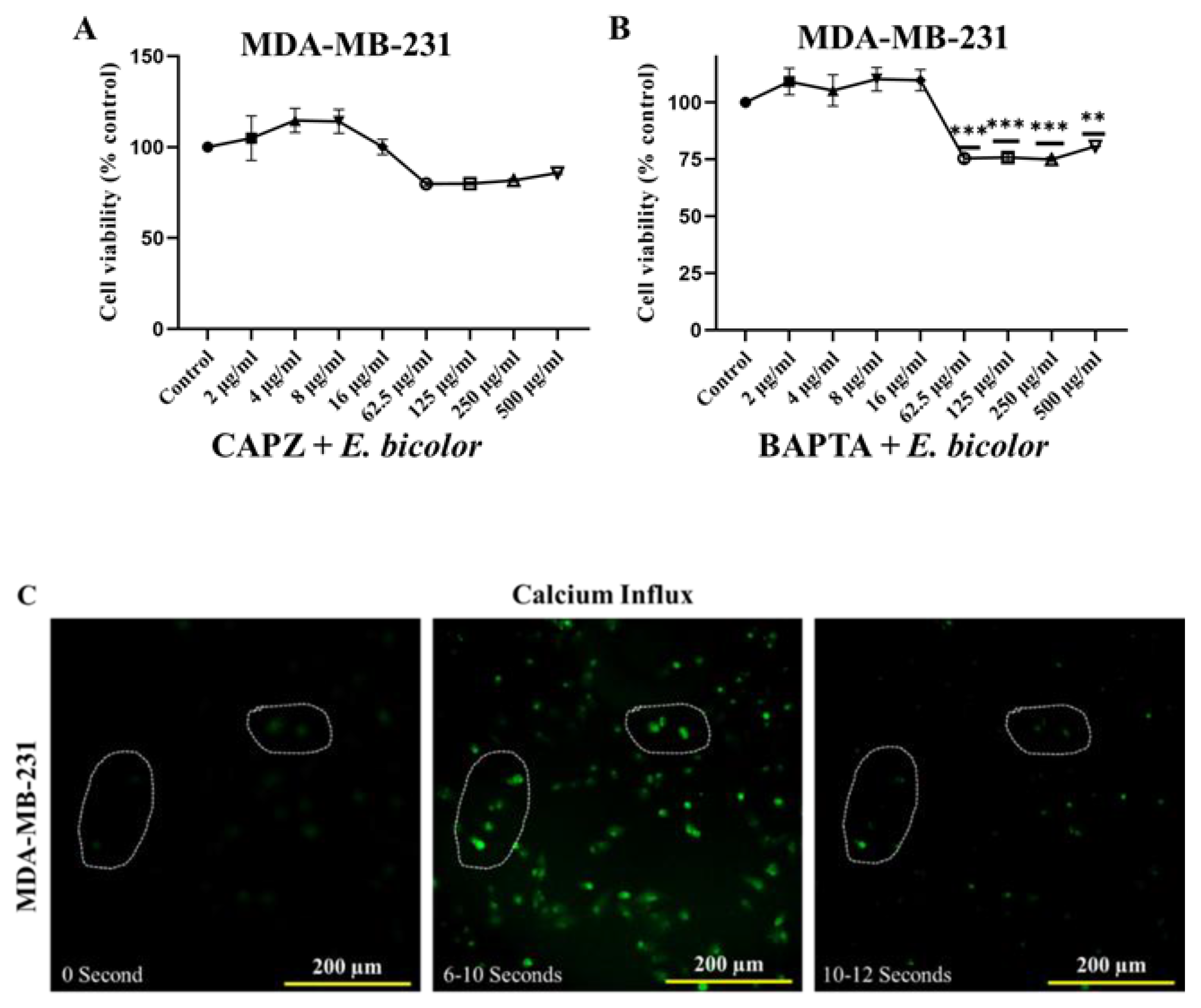

48]. Our results also revealed an immediate (2 seconds after treatment) release of calcium from the ER and mitochondrial calcium overload (27 seconds after treatment) in T47D cells, indicating that increased ROS levels trigger the accumulation of calcium in mitochondria. Other studies also revealed crosstalk between ROS levels and calcium signaling in different diseases, including cardiac physiology, pathologies, and neurodegeneration [

49,

50]. Blocking TRPV1 using capsazepine and chelating calcium with BAPTA-AM led to increased cell viability of MDA-MB-231 cells, suggesting that the activation of TRPV1 by

E. bicolor diterpene extract is the primary mechanism responsible for cell death in that cell line. Consequently, activation of TRPV1 causes an excessive influx of calcium in the cells, ultimately leading to apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells. Therefore, a potential approach for developing new drug therapies for triple-negative breast cancer could involve channel activators to induce calcium influx and cell death [

16]. In T47D cells, blocking TRPV1 with CAPZ inhibited the effect of

E. bicolor diterpene extracts but only at small concentrations of extract (2-16 µg/mL), suggesting that TRPV1 may still be involved in reducing cell viability.

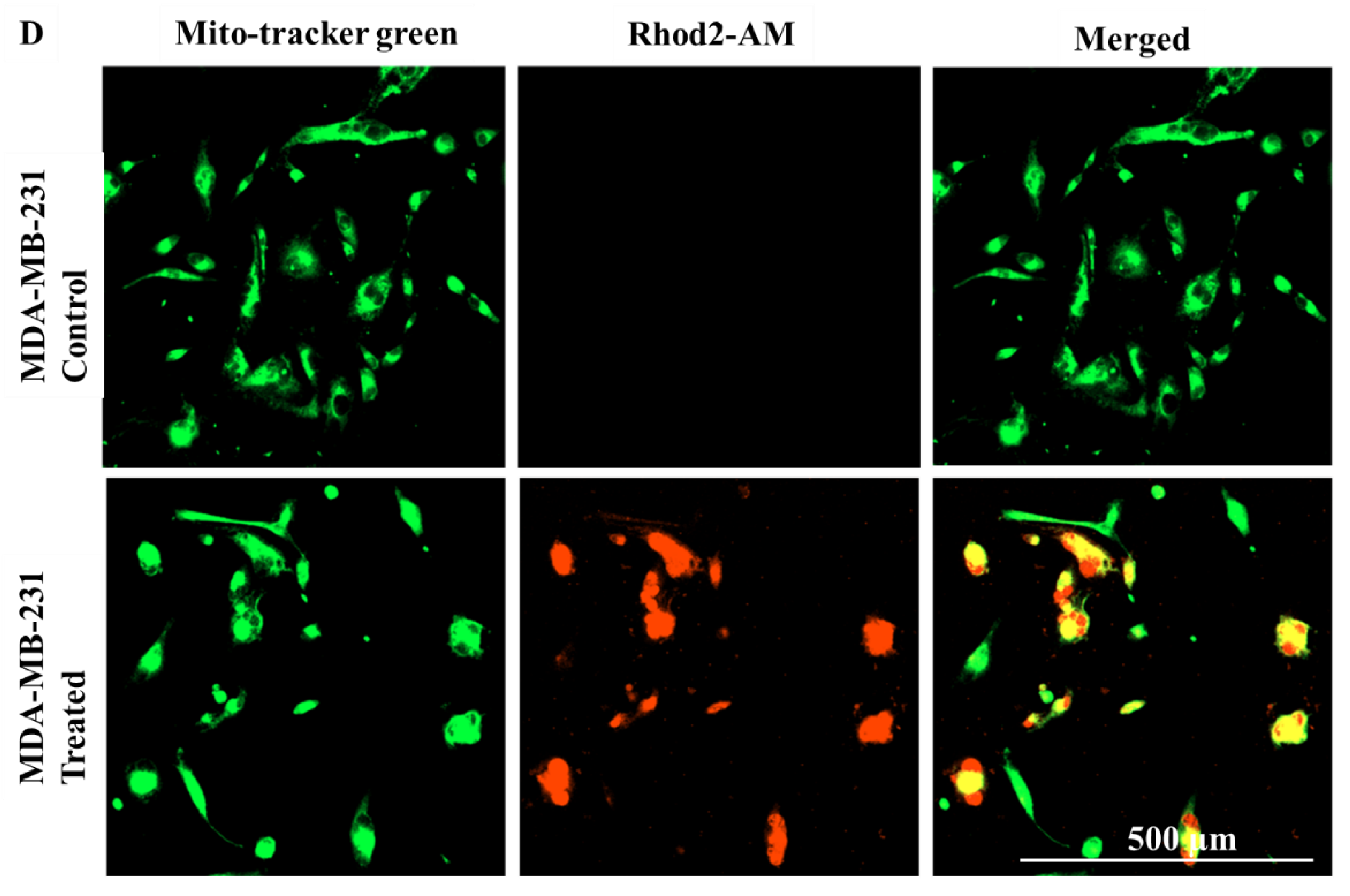

Experimental evidence indicates that when calcium homeostasis is disrupted, it leads to the breakdown of the mitochondrial membrane potential. This disruption also increases ROS levels and the release of proapoptotic proteins, resulting in apoptosis [

13,

51,

52,

53]. In our study, mitochondrial Ca

2+ overload was observed after

E. bicolor diterpene extract treatments in both T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells (

Figure 6). To investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying

E. bicolor induced cell death, we examined the expression of apoptotic protein markers in both the mitochondrial intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. It is known that mitochondrial depolarization induces cytochrome c release into the cytoplasm, activating caspase-3 via caspase-9 [

54]. Activated caspase-3 is one of the hallmarks of apoptosis induced by several

Euphorbia plant extracts such as

E. tirucalli and

E. esula [

9,

11,

55,

56,

57].

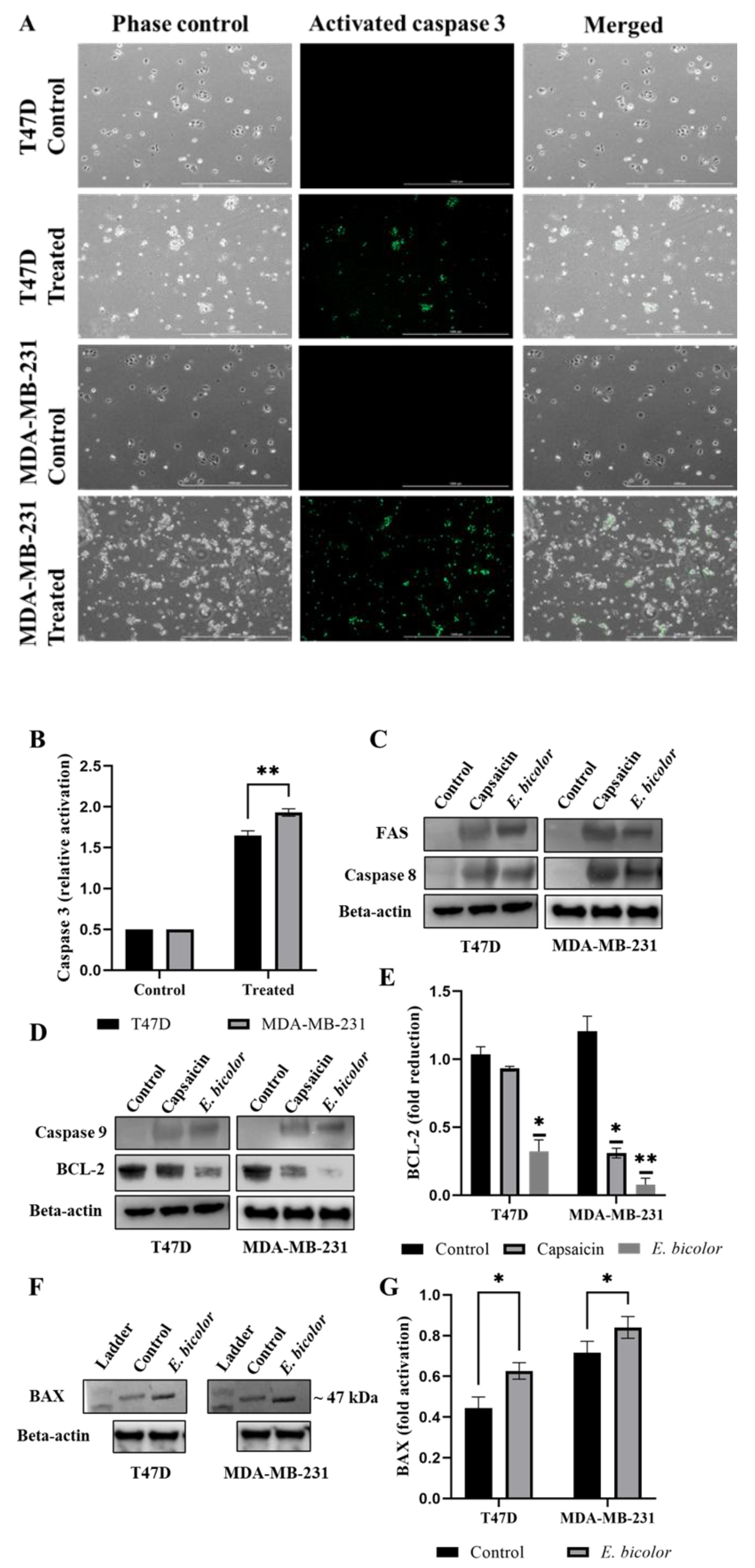

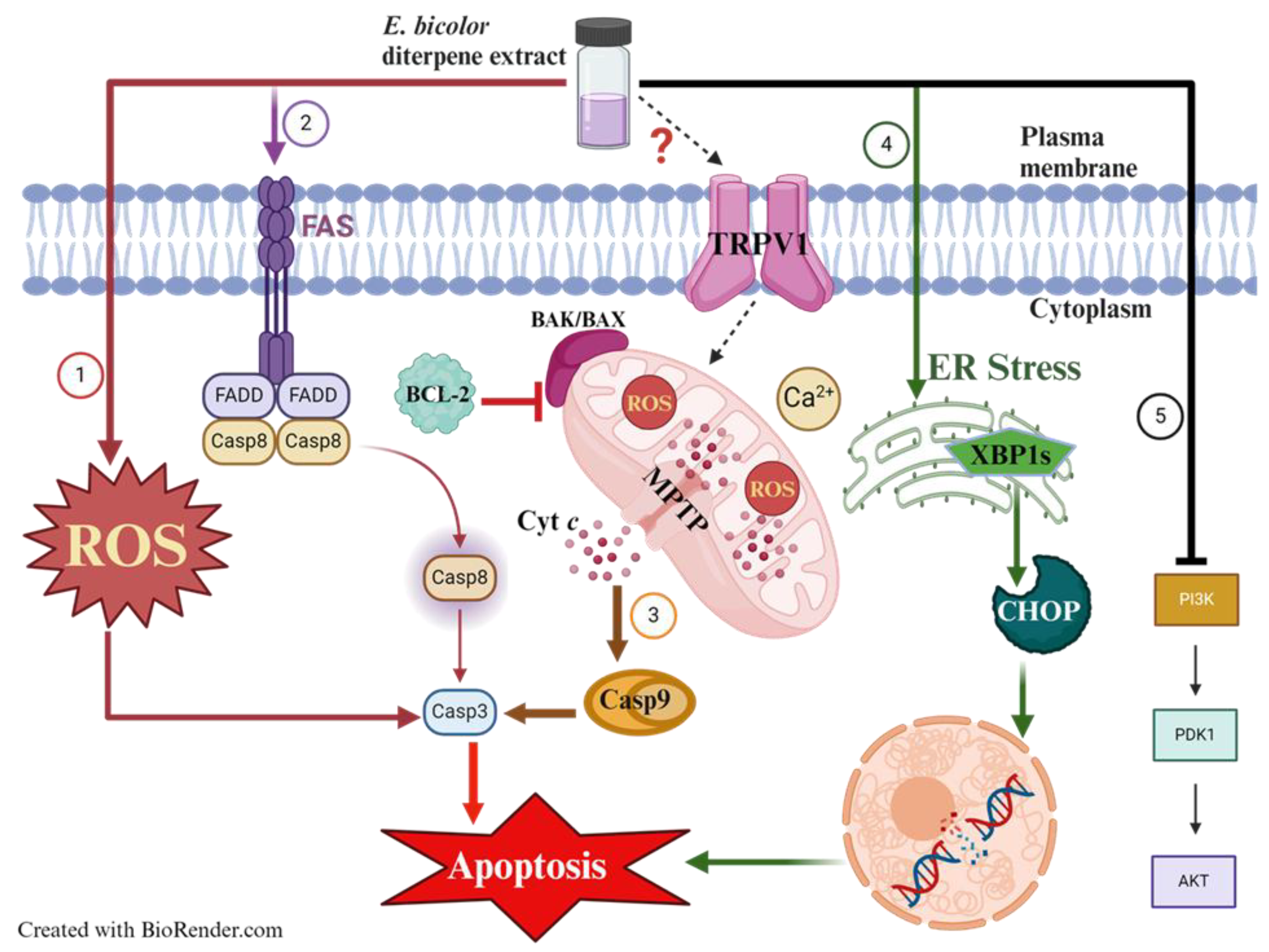

E. bicolor diterpene extract activated downstream caspases-3/9 (

Figure 7), indicating the activation of the apoptotic pathways, as presented in the proposed models of apoptotic mechanisms in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. Anti-apoptotic BCL-2 protein protects cancer cells by preventing apoptosis [

58]. We observed reduced expression of BCL-2 protein in

E. bicolor diterpene extract-treated T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells, suggesting that

E. bicolor diterpenes could be excellent candidates for targeting BCL-2 proteins in different cancers. Our results indicate that the BAX protein is expressed at a high molecular weight on Western blot. Studies indicated that BAX forms oligomers, necessary for its proapoptotic activity. The high molecular weight BAX oligomers bind to the mitochondrial membrane, leading to the mitochondrial intrinsic apoptotic pathway [

16,

59].

E. bicolor diterpene extract activated the extrinsic apoptotic pathway, as observed in the expression of FAS and caspase 8 proteins (

Figure 7 and

Figure 11, and 12). Previous studies support our findings and moreover, they indicate that the TRPV1 N-terminus can bind to proapoptotic FAS-associated proteins, activating extrinsic apoptotic pathways [

16,

60,

61]. TRPV1 is also found in the ER membrane [

62]. Its activation can lead to calcium disruption and cause ER stress [

53], which can be an active source of calcium release in the cytoplasm. ER stress and compromised mitochondria can subsequently release apoptotic signals [

16,

54]. Our results show that

E. bicolor diterpene extract induced ER stress and ultimately triggered apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. In T47D cells, increased ROS levels may trigger ER stress and activate mitochondrial apoptosis as a result of

E. bicolor diterpene extract treatment. Expression of XBP1s, an activated (by splicing) transcription factor that facilitates ER stress [

63], was observed in both

E. bicolor extract treated T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells as an indication of ER-mediated stress, which stimulated the expression of CHOP, a transcription factor that increases the expression of other apoptotic factors [

64] (

Figure 9,

Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Our results also suggest that

E. bicolor diterpene extract targets the PI3K/AKT signal transduction pathway, precisely downregulating it (

Figure 8 and

Figure 11, and 12). The serine/threonine kinase AKT, also known as protein kinase B (PKB), plays a crucial role in regulating many cellular processes, including cell survival, growth, proliferation, cell cycle, and metabolism. The balance between loss or gain of AKT activation is fundamental to the pathophysiological properties of cancer [

65,

66]. We observed significantly low total and phosphorylated AKT and PI3K protein expressions in both

E. bicolor diterpene extract-treated T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells (

Figure 8). Studies have shown that activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway contributes to tumorigenesis, and inhibition of PI3K and AKT can decrease cellular proliferation and increase cell death [

53]. Therefore, our results suggest that

E. bicolor diterpenes could become potential candidates for targeting the PI3K/AKT signaling pathways in breast cancers.

The current study revealed two different antiproliferative mechanisms for the two breast cancer types, ER-positive and triple-negative, which most likely are because of their distinct molecular profiles. T47D cancer cells express estrogen and progesterone hormone receptors, the primary targets for current hormone therapies. MDA-MB-231 cancer cells lack hormone receptors, and therefore, they are not responsive to hormone therapies [

67,

68]. It is known that natural products have multiple molecular targets [

69].

E. bicolor diterpene extract, containing a variety of diterpenes, may affect different targets depending on the cancer cells molecular characteristics resulting in distinct antiproliferative molecular mechanisms.

In conclusion, our study presents for the first time the ROS-mediated antiproliferative mechanisms of action of

E. bicolor diterpene extract in T47D cells (

Figure 11) and TRPV1-dependent mechanisms of action in MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 12).

E. bicolor diterpene extract generates high ROS levels in T47D cells and triggers several apoptotic pathways. In MDA-MB-231 cells,

E. bicolor diterpene extract activates TRPV1 and induces mitochondrial and ER stress-mediated apoptotic pathways. In addition,

E. bicolor diterpene extract downregulates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in both T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. Our findings suggest that

E. bicolor diterpene extract could be used to design specific therapeutics for cancer cell types. For ER-positive cell types, therapeutic agents could target the ROS-inducing apoptotic mechanism. For MDA-MB-231 cell types, the therapeutic mechanism could target the TRPV1-dependent apoptotic pathways.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Extracts

E. bicolor plants were collected from fields around Denton, Texas, USA, during September and October 2023. Aerial plant tissues (50 g) were extracted in 95% ethanol (1:4 w/v) at room temperature for two days. Supernatants were filtered through Whatman filter paper #54 (Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ, USA). To extract diterpenes from

E. bicolor, the protocol from Tidgewell (2007) was used with slight modifications [

70]. Plant aerial tissues (50 g) were extracted in 200 proof xylene (Fisher Scientific, NH, USA) (1:4 w/v) at room temperature for one day, and supernatants were filtered through Whatman filter paper. The filtrates were transferred to a pre-weighted vial and evaporated to dryness under nitrogen gas flow. Dried extract was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Fisher Scientific, NH, USA) in a 1:1 ratio and stored at -20 °C until use. The extract collected using ethanol solvent is named ethanol extract, and the extract collected using xylene solvent is named diterpene extract.

4.2. Cell Lines and Cell Culture Conditions

Estrogen receptor-positive T47D, triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines, and adult human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). T47D and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines were cultured and maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; ThermoFisher Scientific, Township, NJ, USA), as previously reported [

32]. Adult human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC) were grown in mammary epithelial basal medium (ATCC) supplemented with mammary epithelial cell growth kit (ATCC). All cell lines were incubated under a humid atmosphere of 5% (v/v) CO2 at 37 °C.

4.3. Cell Culture Treatments

All cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture plates at 10,000 cells/well in a phenol-red-free medium and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After 24 h, the cells were treated with different concentrations of E. bicolor ethanol, diterpene extracts in DMSO (2, 4, 8, 16, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 µg/ml) or capsaicin at 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 250, and 500 µM concentrations. The final concentration of DMSO was <0.1%.

4.4. Antiproliferative Assays

Antiproliferative activity was evaluated by performing MTS [3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium] assay (Abcam, USA) [

32]. Briefly, cells were seeded into a 96-well plate (10,000 cells/well) and exposed to various concentrations of

E. bicolor ethanol, diterpene extracts, or capsaicin. After 72 h of treatments, 10 µl of MTS reagent was added to each well, and plates were incubated at 37 °C for 2.5 h, and absorbance was read at 490 nm using a Biotek's Synergy HT plate reader (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) [

32]. At least three separate experiments, each containing three replicates, were performed. HMEC cells showed reduction of cell viability starting at 125 µg/ml concentration using

E. bicolor diterpene extract. Therefore, the rest of the experiments were set up to use 62.5 µg/ml concentration to determine the antiproliferative mechanisms.

4.5. IC50 Estimation

The MTS assay results were used to calculate the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) using the GraphPad Prism 9.4 software. A dose-response curve was fitted using nonlinear regression.

4.6. Visualization of Cytotoxic Effects

The morphological changes of the cells were observed using the live cell imaging system IncuCyte (Sartorius, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) for several days. Cells were seeded into a 96-well plate (10,000 cells/well) and exposed to 62.5 µg/ml of E. bicolor diterpene extract, before being placed into the IncuCyte live cell imaging system. The system was programmed to capture high-resolution, bright field photos every 4 hours.

4.7. Detection of Apoptosis

Cell apoptosis was observed by employing the Click-iT™ Plus TUNEL (the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling) assay kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Cells were grown on coverslips inside the 6-well plate and treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract at a concentration of 62.5 µg/mL. Twenty-four hours after treatments, T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde. TUNEL assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, and nuclear fluorescence of cells was detected and analyzed using a LionHeart FX microscope (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

4.8. Capsazepine Treatments to Block TRPV1

Cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture plates at 10,000 cells/well and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After 24 h, cells were pretreated with 10 µM of capsazepine (Abcam, USA), a TRPV1 antagonist, for 30 minutes. Afterward, cells were treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract (62.5 µg/mL). The plates were incubated for 72 h at 37 °C. Cell viability was measured using MTS assays. Three independent experiments were conducted.

4.9. Calcium Chelation

Cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture plates at 10,000 cells/well and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After 24 h, cells were pretreated with 1 µM of BAPTA-AM (Abcam, USA), a calcium chelator, for 30 minutes, and then treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract (62.5 µg/mL). The plates were incubated for 72 h at 37 °C. Then, cell viability was measured using MTS assays. Three independent experiments were conducted.

4.10. Visualization of TRPV1 Activation

The cytoplasmic calcium dynamics as the result of TRPV1 activation were observed using Fura2-AM staining. T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded into a 6-well plate and cultured overnight. After 24 h, cells were loaded with 5 μM of Fura2-AM for 30 min. Following E. bicolor diterpene treatment, the cytosolic Ca2+ signal was monitored continuously for 20 min using a LionHeart FX microscope.

4.11. ROS Detection

The intracellular ROS levels were determined using cell-permeant reagent 2',7'–dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA). Tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP; 250 μM) was used as positive control. The fluorescence intensity values at each time point were calculated as the ratio of the value at a specific t-time point to the value at point zero time (t-time point/t0); t0 = first measurement). Briefly, cells were plated in FBS-supplemented medium without phenol red onto 96-well plates. After 24 hours, the cells were washed once with 1X buffer provided in the kit, then the cells were incubated with 10 μM of DCFDA for 30 min at 37 °C, protected from light. Following incubation, the wells were washed with PBS, and treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract. ROS production was determined immediately by measuring the formation of fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (DCF), using a Synergy microplate reader, at 485 nm excitation and 535 nm emission. Measurements were taken every 60 min for six hours. Three independent experiments were conducted.

4.12. N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) Treatments to Block ROS Generation

Cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture plates at 10,000 cells/well and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After 24 h, cells were pretreated with NAC (5 mM) for 1 h followed by treatment with or without E. bicolor for another 72 h, and cell viability was measured using MTS assay. Three independent experiments were conducted.

4.13. Visualization of ER Calcium

ER-targeted low-affinity GCaMP6-210 variant, a fluorescent reporter for ER calcium signaling, was used to observe endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ dynamics. T47D cells were seeded into a 24-well plate at 10.4 x 104 cells in 500 µL phenol red free growth medium. After 24 h, cells were transfected with the GCaMP6-210 variant using Invitrogen™ Lipofectamine™ 3000 Transfection Reagent (Thermofisher Scientific, USA). Twelve hours after incubation, immediately after E. bicolor diterpene extract treatment (62.5 µg/mL), calcium influx was observed with the LionHeart FX microscope.

4.14. Visualization of Mitochondrial Calcium

The mitochondrial calcium dynamics were observed using Rhod2-AM (Abcam, USA). T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were grown in 6-well plates and simultaneously loaded with 5 μM of Rhod2-AM, 10 μM of MitoTracker Green (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) and then exposed to E. bicolor diterpene extracts (62.5 µg/mL). The corresponding fluorescence signals were monitored for 10 minutes with the LionHeart FX microscope in red and green fluorescence channels.

4.15. Caspase 3 Activation Assay

All cells were seeded into 6-well cell culture plates at 2 x 105 cells/well and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After 24 h, cells were treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract (62.5 µg/mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. One drop of the CellEvent™ Caspase-3/7 Green ReadyProbes™ reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) was added in each well. After a 45-minute incubation, cell fluorescence was detected and analyzed with a LionHeart FX microscope.

4.16. Western Blotting

As previously reported [

16], Western blotting was carried out with a few changes. Proapoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins were examined using total cellular protein. The cell lysates were prepared using RIPA lysis and extraction buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) supplemented with Halt™ protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Cell lysates were centrifuged at 12,000xg at 4 °C for 5 min, the supernatant was collected, and the total protein concentrations were estimated using Pierce™ 660nm Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Protein samples were subjected to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (BioRad, USA). The membranes were immersed in blocking buffer (0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4, with 5% (w/v) skim milk) at room temperature for 2 hours. They were then probed using antibodies in the same blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C.

Antibodies used were as follows: anti-beta actin, anti-caspase 9, anti-caspase 8, anti-CHOP, anti-ATF4, anti-FAS, anti-PERK (mouse monoclonal antibody conjugated with HRP; 1:1000, v/v) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), anti-AKT, anti-pAKT (mouse monoclonal antibody conjugated with Alexa 488; 1:1000, v/v) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA). Membranes were washed three times with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST) for 5 minutes each, incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate solution (BioRad, USA) for 5 min, according to the manufacturer's instructions, and visualized with a ChemiDoc system. For anti-Bcl-2, anti-BAX (rabbit monoclonal antibody; 1:1000, v/v) (Abcam, USA), anti-pPERK, anti-PI3K, anti-XBP1s (rabbit monoclonal antibody; 1:1000, v/v) (Cell Signaling Technology, USA), following the overnight incubation, the membranes were incubated with the secondary antibody (Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L, Alexa Fluor® 488; 1:500 v/v) for five minutes each after being rinsed three times in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h. Following incubation, the membranes underwent three rounds of washing with TBST buffer and were immediately visualized using a ChemiDoc system.

4.17. Statistical Analyses

Means and standard errors of the mean of at least three experiments were calculated. One-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Tukey's posthoc test to determine significant differences among the means for the antiproliferative (MTS) assays and fold expression analysis of Western blot (to compare DMSO control and

E. bicolor diterpene extract treatment) using GraphPad Prism 9.4. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Unpaired Welch’s t-test, to compare treated to DMSO control set, was used for TUNEL assays. A two-way ANOVA was performed, followed by the Dunnett test to determine significant differences among the means of Western blot fold expression (to compare DMSO control,

E. bicolor diterpene extract, and capsaicin treatment). ImageJ software (

https://imagej.net/ij/download.html) was used to determine fold protein expression on Western blots.

Figure 1.

Antiproliferative activities of E. bicolor extracts on ER-positive T47D and triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines. (A, B) Effect of E. bicolor ethanol extract on T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells; (C, D) Effect of E. bicolor diterpene extract on T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells; (E, F) Effect of capsaicin (+ control) on T47D and MDA-MB-231 cell lines; (G, H) Effect of E. bicolor diterpene and ethanol extracts on the growth of human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC). Values represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. A one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Tukey's post hoc test. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set.

Figure 1.

Antiproliferative activities of E. bicolor extracts on ER-positive T47D and triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines. (A, B) Effect of E. bicolor ethanol extract on T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells; (C, D) Effect of E. bicolor diterpene extract on T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells; (E, F) Effect of capsaicin (+ control) on T47D and MDA-MB-231 cell lines; (G, H) Effect of E. bicolor diterpene and ethanol extracts on the growth of human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC). Values represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. A one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Tukey's post hoc test. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set.

Figure 2.

Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of E. bicolor diterpene extract and capsaicin in ER-positive T47D and triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines. (A) T47-D; (B) MDA-MB-231; (C) HMEC; (D, E) IC50 of capsaicin in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cell lines, respectively. (F) T47D and MDA-MB-231 cell morphology 72 h after E. bicolor diterpene extract treatment (62.5 μg/ml). Cell morphological changes were observed for seven days using the live cell imaging system IncuCyte. Representative pictures of cell morphologies three days after treatment. Scale bar: 400 μm.

Figure 2.

Half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of E. bicolor diterpene extract and capsaicin in ER-positive T47D and triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines. (A) T47-D; (B) MDA-MB-231; (C) HMEC; (D, E) IC50 of capsaicin in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cell lines, respectively. (F) T47D and MDA-MB-231 cell morphology 72 h after E. bicolor diterpene extract treatment (62.5 μg/ml). Cell morphological changes were observed for seven days using the live cell imaging system IncuCyte. Representative pictures of cell morphologies three days after treatment. Scale bar: 400 μm.

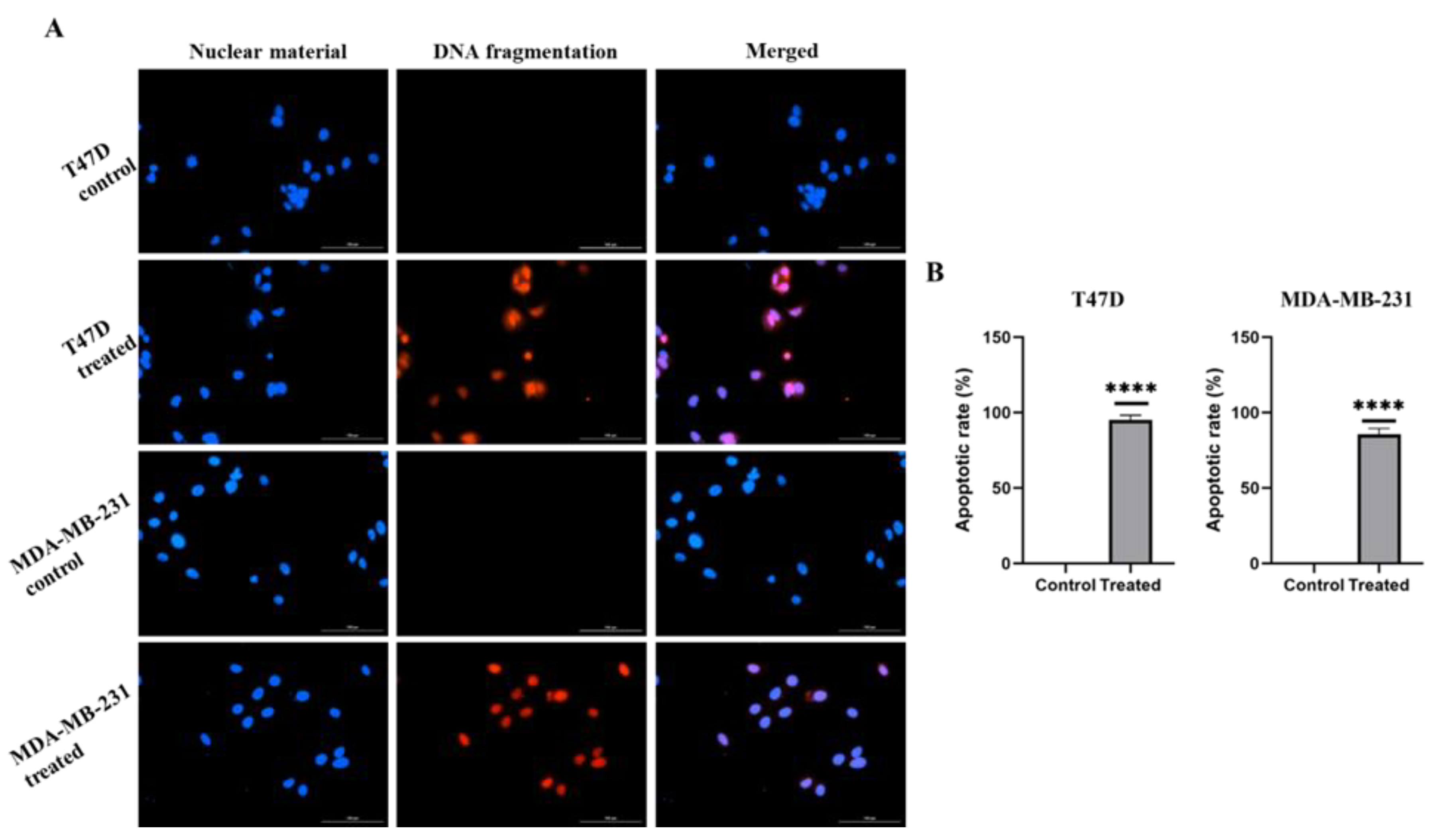

Figure 3.

Apoptosis detected by TUNEL assay. (A) T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract. Red fluorescence indicates that the modified dUTPs from the TUNEL test kit bind to the apoptotic broken DNA. Hoechst 33342 was used to stain nuclear material (blue fluorescence). Cells were visualized with LionHeart FX microscope, scale bar: 100 μm (B) Apoptotic rate (%) of TUNEL assays. The number of apoptotic cells were counted using LionHeart BioTek Gen5.0 software. Unpaired Welch’s t-test, ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set.

Figure 3.

Apoptosis detected by TUNEL assay. (A) T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract. Red fluorescence indicates that the modified dUTPs from the TUNEL test kit bind to the apoptotic broken DNA. Hoechst 33342 was used to stain nuclear material (blue fluorescence). Cells were visualized with LionHeart FX microscope, scale bar: 100 μm (B) Apoptotic rate (%) of TUNEL assays. The number of apoptotic cells were counted using LionHeart BioTek Gen5.0 software. Unpaired Welch’s t-test, ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set.

Figure 4.

ROS level detection after E. bicolor diterpene extract treatment. (A, B) Increased ROS levels with time in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. (C, D) ROS accumulation at 6 hr of treatment. Tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP, 250 μM) was used as the positive control, and DMSO (0.1%) as the negative control. (E, F) Cell viability after inhibition of ROS formation with NAC in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were pretreated with NAC (5 mM), a ROS inhibitor, for 1 h, then treated with or without E. bicolor diterpene extract for 72 h. Cell viability was measured using MTS assay. Values represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set.

Figure 4.

ROS level detection after E. bicolor diterpene extract treatment. (A, B) Increased ROS levels with time in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. (C, D) ROS accumulation at 6 hr of treatment. Tert-butyl hydroperoxide (TBHP, 250 μM) was used as the positive control, and DMSO (0.1%) as the negative control. (E, F) Cell viability after inhibition of ROS formation with NAC in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were pretreated with NAC (5 mM), a ROS inhibitor, for 1 h, then treated with or without E. bicolor diterpene extract for 72 h. Cell viability was measured using MTS assay. Values represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set.

Figure 5.

Calcium dynamics in T47D induced by E. bicolor diterpene extract treatment. (A) Cell viability after blocking TRPV1 with capsazepine (CAPZ), a TRPV1 antagonist. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM CAPZ, and then treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract. (B) Cell viability after chelating calcium with BAPTA-AM. Cells were pretreated with 1 μM of BAPTA-AM, and then treated with E. bicolor extract (62.5 μg/ml). Cell viability was measured by MTS assay. Values represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set. (C) Visualization of calcium dynamics in T47D cells. Cells were loaded with 5 μM of Ca2+ sensitive fluorescent probe Fura2-AM and then exposed to 62.5 μg/ml of E. bicolor in HBSS buffer (with Ca2+ and Mg2+). The fluorescent images were captured every 2 seconds and recorded for 10 min. Representative Ca2+ fluorescence images at indicated time points are shown. The region of interest was drawn with a dotted circle. (D) Visualization of ER calcium dynamics with a fluorescent reporter for ER calcium signaling in GCaMP6-210 plasmid variant. T47D cells were grown in a 24-well plate for 24 hours and transfected with GCaMP6-210 plasmid variant. Twelve hours after incubation, cells were exposed to 62.5 μg/ml of E. bicolor in HBSS buffer (with Ca2+ and Mg2+). The fluorescent images were captured every 2 seconds and recorded for 10 min. (E) visualization of mitochondrial calcium with MitoTracker Green. T47D cells were simultaneously loaded with 10 μM of MitoTracker Green and 5 μM of Rhod2-AM and then exposed to 62.5 μg/ml of E. bicolor diterpene extract. A LionHeart FX microscope, 4X magnification, monitored the corresponding fluorescence signal.

Figure 5.

Calcium dynamics in T47D induced by E. bicolor diterpene extract treatment. (A) Cell viability after blocking TRPV1 with capsazepine (CAPZ), a TRPV1 antagonist. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM CAPZ, and then treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract. (B) Cell viability after chelating calcium with BAPTA-AM. Cells were pretreated with 1 μM of BAPTA-AM, and then treated with E. bicolor extract (62.5 μg/ml). Cell viability was measured by MTS assay. Values represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set. (C) Visualization of calcium dynamics in T47D cells. Cells were loaded with 5 μM of Ca2+ sensitive fluorescent probe Fura2-AM and then exposed to 62.5 μg/ml of E. bicolor in HBSS buffer (with Ca2+ and Mg2+). The fluorescent images were captured every 2 seconds and recorded for 10 min. Representative Ca2+ fluorescence images at indicated time points are shown. The region of interest was drawn with a dotted circle. (D) Visualization of ER calcium dynamics with a fluorescent reporter for ER calcium signaling in GCaMP6-210 plasmid variant. T47D cells were grown in a 24-well plate for 24 hours and transfected with GCaMP6-210 plasmid variant. Twelve hours after incubation, cells were exposed to 62.5 μg/ml of E. bicolor in HBSS buffer (with Ca2+ and Mg2+). The fluorescent images were captured every 2 seconds and recorded for 10 min. (E) visualization of mitochondrial calcium with MitoTracker Green. T47D cells were simultaneously loaded with 10 μM of MitoTracker Green and 5 μM of Rhod2-AM and then exposed to 62.5 μg/ml of E. bicolor diterpene extract. A LionHeart FX microscope, 4X magnification, monitored the corresponding fluorescence signal.

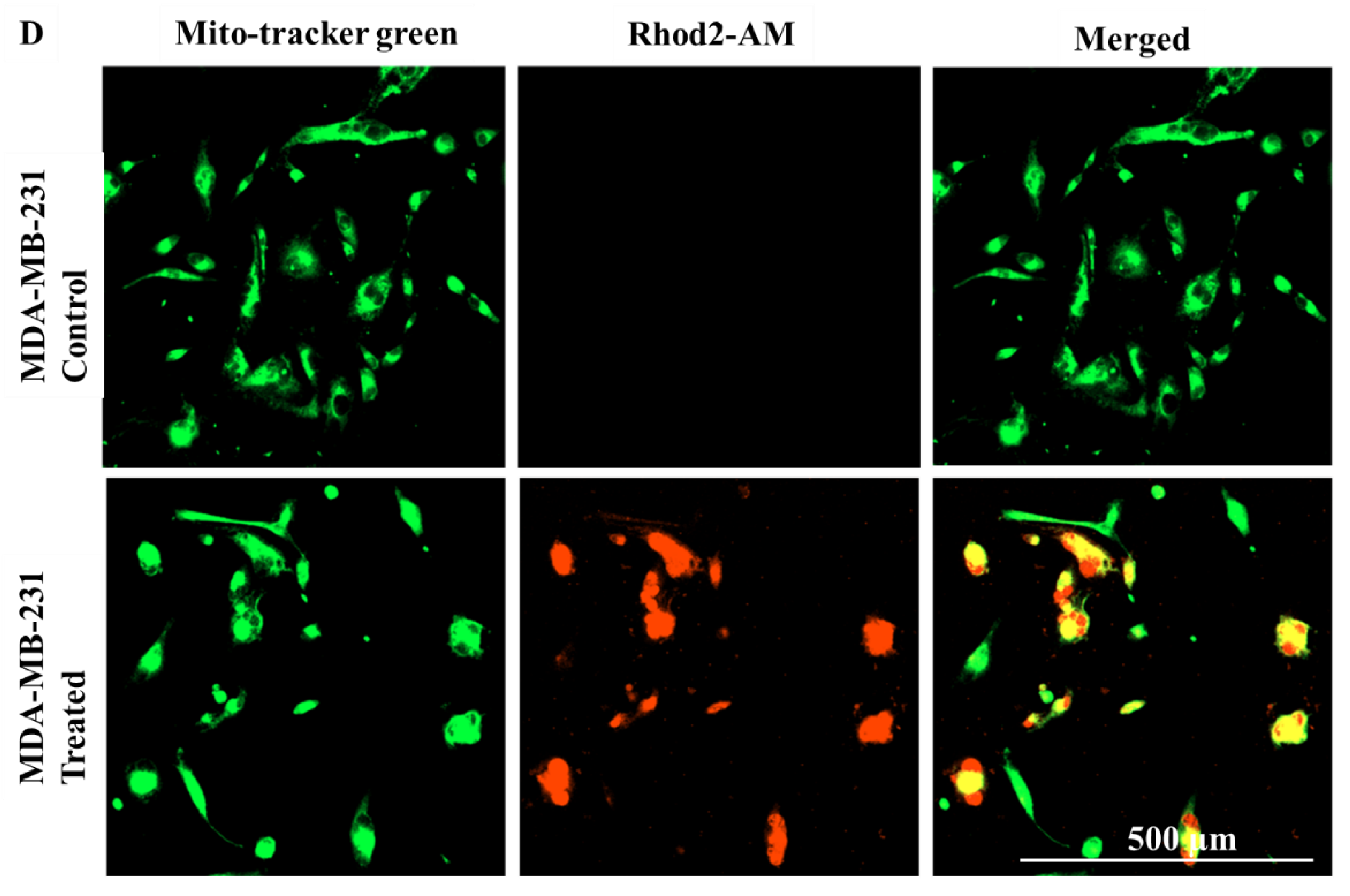

Figure 6.

Calcium dynamics in MDA-MB-231 cells induced by E. bicolor diterpene extract. (A) Cell viability after blocking TRPV1 with CAPZ. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM CAPZ and then treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract (62.5 μg/ml). (B) Cell viability after chelating calcium with BAPTA-AM. Cells were pretreated with 1 μM of BAPTA-AM and then treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract (62.5 μg/ml). Cell viability was measured by MTS assay. Values represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set. (C) Visualization of calcium dynamics in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were loaded with 5 μM of Ca2+ sensitive fluorescent probe Fura2-AM and then exposed to E. bicolor diterpene extract (62.5 μg/ml) in HBSS buffer (with Ca2+ and Mg2+). The fluorescent images were captured every 2 seconds and recorded for 10 min. Representative Ca2+ fluorescence images at indicated time points were shown, and regions of interest were drawn with dotted circles. (D) Visualization of mitochondrial calcium with MitoTracker Green. MDA-MB-231 cells were simultaneously loaded with 10 μM of MitoTracker Green and 5 μM of Rhod2-AM and then exposed to E. bicolor extract (62.5 μg/ml). The corresponding fluorescence signal was monitored by a LionHeart FX microscope at 4X magnification.

Figure 6.

Calcium dynamics in MDA-MB-231 cells induced by E. bicolor diterpene extract. (A) Cell viability after blocking TRPV1 with CAPZ. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM CAPZ and then treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract (62.5 μg/ml). (B) Cell viability after chelating calcium with BAPTA-AM. Cells were pretreated with 1 μM of BAPTA-AM and then treated with E. bicolor diterpene extract (62.5 μg/ml). Cell viability was measured by MTS assay. Values represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set. (C) Visualization of calcium dynamics in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were loaded with 5 μM of Ca2+ sensitive fluorescent probe Fura2-AM and then exposed to E. bicolor diterpene extract (62.5 μg/ml) in HBSS buffer (with Ca2+ and Mg2+). The fluorescent images were captured every 2 seconds and recorded for 10 min. Representative Ca2+ fluorescence images at indicated time points were shown, and regions of interest were drawn with dotted circles. (D) Visualization of mitochondrial calcium with MitoTracker Green. MDA-MB-231 cells were simultaneously loaded with 10 μM of MitoTracker Green and 5 μM of Rhod2-AM and then exposed to E. bicolor extract (62.5 μg/ml). The corresponding fluorescence signal was monitored by a LionHeart FX microscope at 4X magnification.

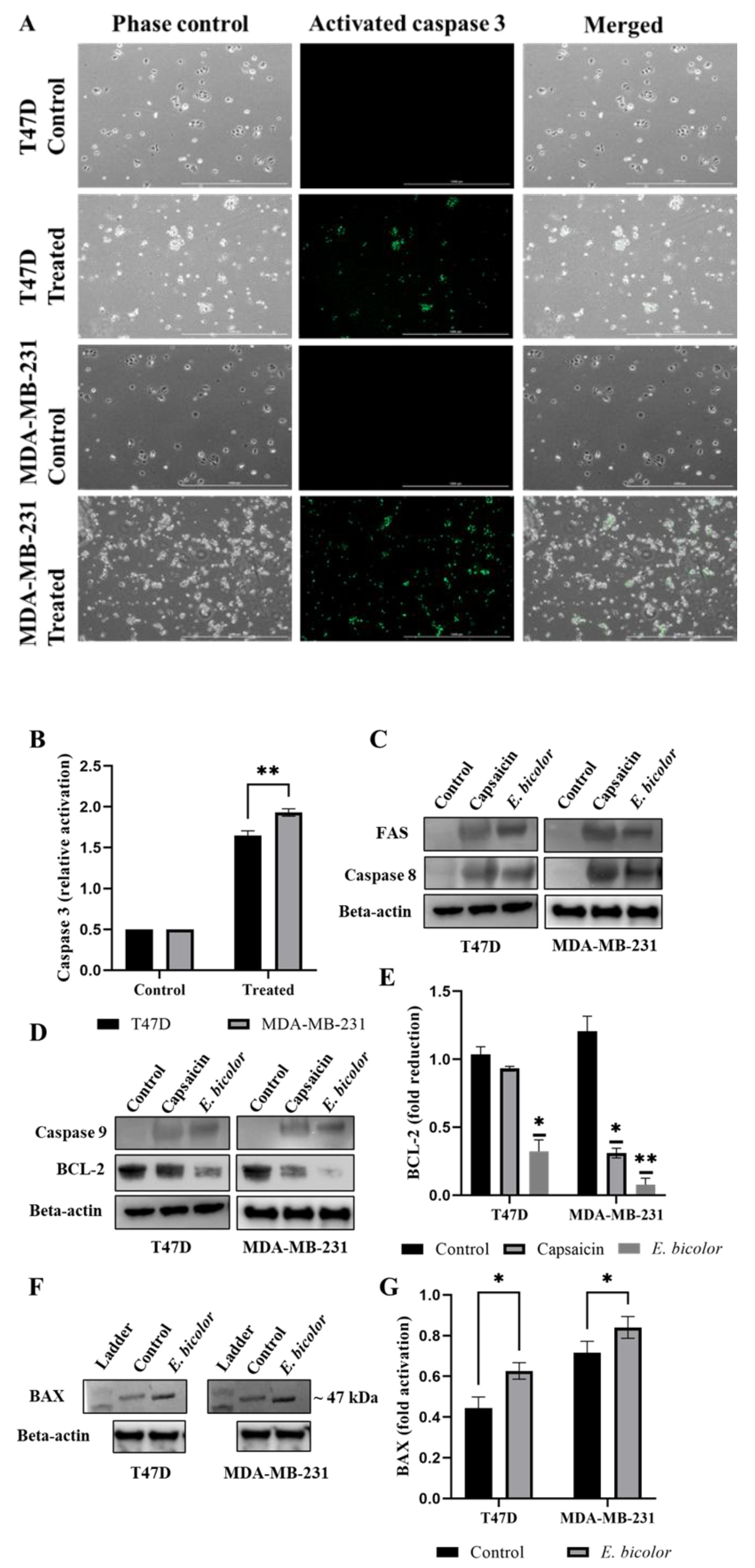

Figure 7.

E. bicolor diterpene extract induces mitochondrial intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Visualization of activated caspase 3 after E. bicolor diterpene extract treatment. T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with E. bicolor (62.5 µg/ml) for 24 h, one drop of caspase 3/7 reagent was added, and the corresponding fluorescence signal was monitored by a LionHeart FX microscope; scale bar, 200 μm. (B) Relative activation of caspase 3 measured with LionHeart BioTek Gen5.0 software. Two-way ANOVA, **p<0.001. (C) Western blot analyses of mitochondrial extrinsic apoptotic proteins FAS and caspase 8. T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with E. bicolor (62.5 µg/mL) or capsaicin (500 µM) for 24 h; cell lysates were isolated and immunoblot analyses of proteins FAS and caspase 8 were performed. (D) Western blot analyses of mitochondrial intrinsic apoptotic protein caspase 9 and antiapoptotic BCL-2. T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with E. bicolor (62.5 µg/mL) or capsaicin (500 µM) for 24 h, and cell lysates were isolated, and immunoblot analyses of proteins caspase 9 and BCL-2 were performed. (E) Fold reduction of BCL-2. One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. (F) Western blot analyses of proapoptotic BAX protein. (G) Fold activation of BAX. Unpaired t-test, *p<0.05. Representative Western blots, beta-actin served as loading control. Control, non-treated cells (DMSO).

Figure 7.

E. bicolor diterpene extract induces mitochondrial intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Visualization of activated caspase 3 after E. bicolor diterpene extract treatment. T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with E. bicolor (62.5 µg/ml) for 24 h, one drop of caspase 3/7 reagent was added, and the corresponding fluorescence signal was monitored by a LionHeart FX microscope; scale bar, 200 μm. (B) Relative activation of caspase 3 measured with LionHeart BioTek Gen5.0 software. Two-way ANOVA, **p<0.001. (C) Western blot analyses of mitochondrial extrinsic apoptotic proteins FAS and caspase 8. T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with E. bicolor (62.5 µg/mL) or capsaicin (500 µM) for 24 h; cell lysates were isolated and immunoblot analyses of proteins FAS and caspase 8 were performed. (D) Western blot analyses of mitochondrial intrinsic apoptotic protein caspase 9 and antiapoptotic BCL-2. T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with E. bicolor (62.5 µg/mL) or capsaicin (500 µM) for 24 h, and cell lysates were isolated, and immunoblot analyses of proteins caspase 9 and BCL-2 were performed. (E) Fold reduction of BCL-2. One-way ANOVA, *p<0.05, **p<0.01. (F) Western blot analyses of proapoptotic BAX protein. (G) Fold activation of BAX. Unpaired t-test, *p<0.05. Representative Western blots, beta-actin served as loading control. Control, non-treated cells (DMSO).

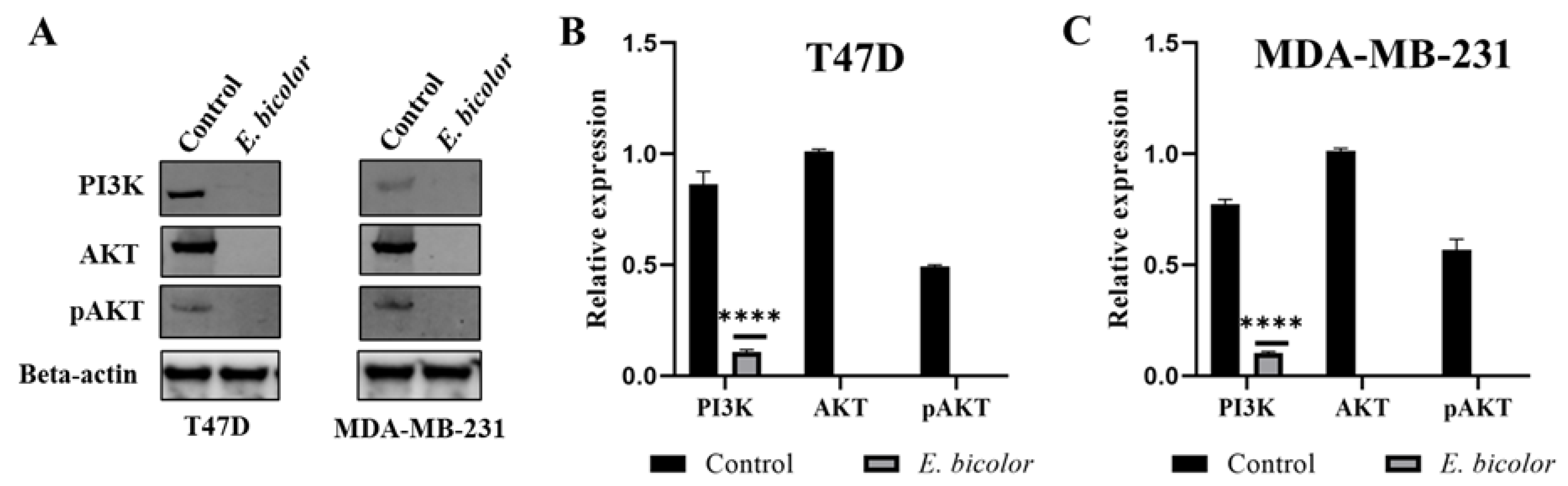

Figure 8.

E. bicolor diterpene extract inhibits the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Western blot analyses. Cells were treated with E. bicolor extract (62.5 µg/ml) for 24 h, cell lysates were isolated, and immunoblot analyses of proteins PI3K, AKT, and pAKT were performed. Representative Western blot, control – untreated cells (DMSO); beta-actin served as loading control. (B, C) Relative expressions of PI3K, AKT, and pAKT in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively. Unpaired t-test, ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set. Control, untreated cells (DMSO).

Figure 8.

E. bicolor diterpene extract inhibits the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Western blot analyses. Cells were treated with E. bicolor extract (62.5 µg/ml) for 24 h, cell lysates were isolated, and immunoblot analyses of proteins PI3K, AKT, and pAKT were performed. Representative Western blot, control – untreated cells (DMSO); beta-actin served as loading control. (B, C) Relative expressions of PI3K, AKT, and pAKT in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells, respectively. Unpaired t-test, ****p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set. Control, untreated cells (DMSO).

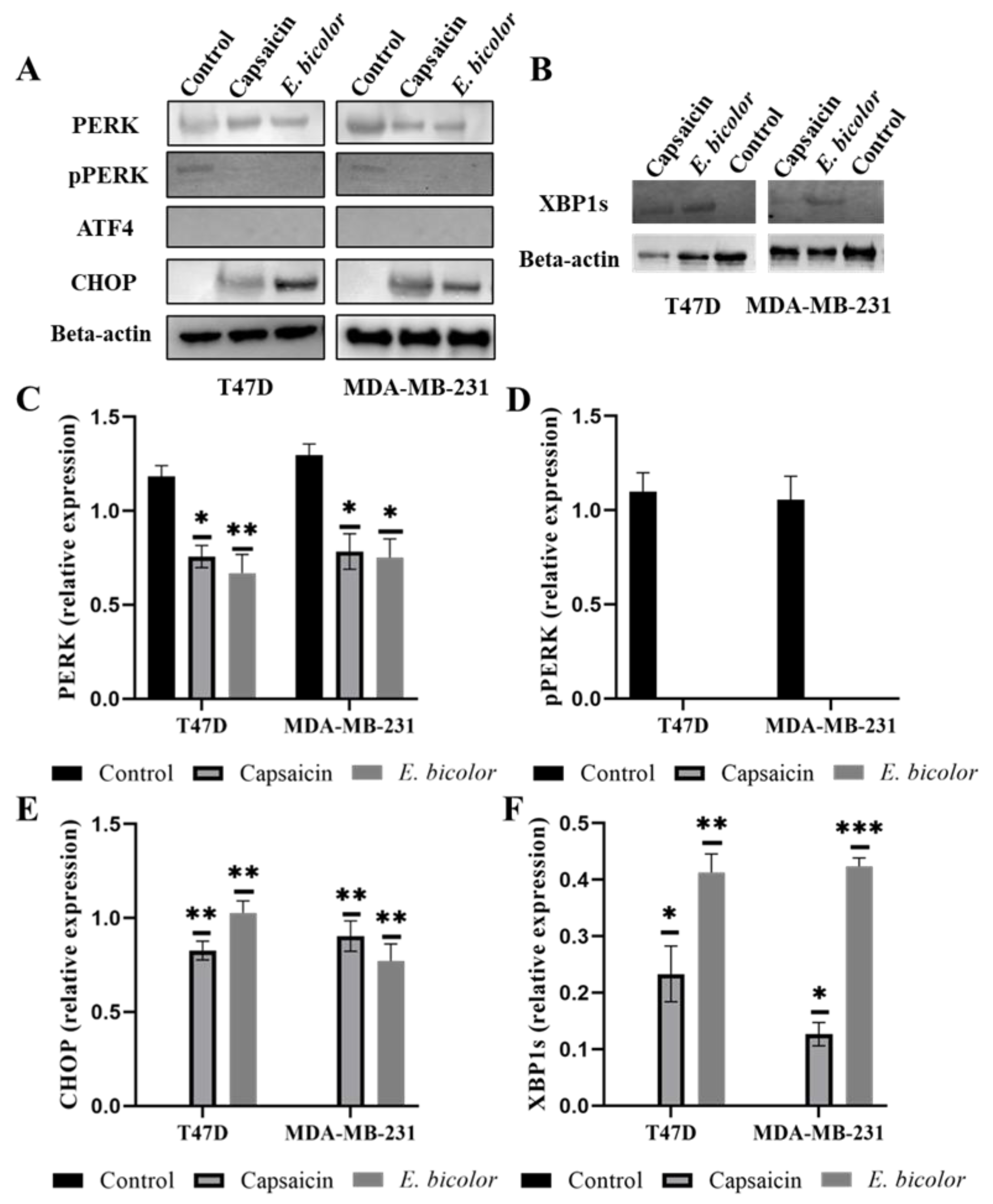

Figure 9.

E. bicolor induces ER stress-dependent apoptosis in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. (A, B) Western blot analysis of ER-stress mediated apoptotic proteins. T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with E. bicolor (62.5 µg/mL) or capsaicin (500 µM) for 24 h. Western blot analyses of ER stress-dependent apoptotic proteins PERK, pPERK, CHOP, and ATF4, XBP1s were performed. Representative Western blot, beta-actin served as the loading control. (C, D, E) Relative expression of PERK, pPERK, and CHOP in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. (F) Relative expression of XBP1s. One-way ANOVA, **p<0.01, ***p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set. Control, cells in DMSO medium. ImageJ software was used to determine fold protein expression.

Figure 9.

E. bicolor induces ER stress-dependent apoptosis in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. (A, B) Western blot analysis of ER-stress mediated apoptotic proteins. T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with E. bicolor (62.5 µg/mL) or capsaicin (500 µM) for 24 h. Western blot analyses of ER stress-dependent apoptotic proteins PERK, pPERK, CHOP, and ATF4, XBP1s were performed. Representative Western blot, beta-actin served as the loading control. (C, D, E) Relative expression of PERK, pPERK, and CHOP in T47D and MDA-MB-231 cells. (F) Relative expression of XBP1s. One-way ANOVA, **p<0.01, ***p<0.0001 vs. DMSO control set. Control, cells in DMSO medium. ImageJ software was used to determine fold protein expression.

Figure 10.

Proposed model of the mechanisms of action of E. bicolor diterpene extract on ER-positive T47D breast cancer cells. (1) Plant extract increases ROS level. The elevated ROS level could trigger several apoptotic pathways. Increasing levels of ROS led to caspase 3 activation, increasing proapoptotic proteins BAK/BAX, decreasing anti-apoptotic BCL-2, and leading to mitochondrial intrinsic (3) and extrinsic (2) apoptotic pathway by activating FAS, caspase 8, and caspase 3. It may be that plant extract activates the FAS-caspase 8 pathway directly (2). (4) ER-stress mediated apoptosis pathway. Increasing ROS level and/or E. bicolor plant extract led to ER stress. ER-stress activates XBP1s, which activates CHOP leading to XBP1s-CHOP-mediated apoptosis. (5) E. bicolor diterpene extract downregulates the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. The question mark (?) signifies that TRPV1 may or may not be involved in triggering apoptotic pathways depending on E. bicolor diterpene extract concentrations. Created with BioRender.com.

Figure 10.

Proposed model of the mechanisms of action of E. bicolor diterpene extract on ER-positive T47D breast cancer cells. (1) Plant extract increases ROS level. The elevated ROS level could trigger several apoptotic pathways. Increasing levels of ROS led to caspase 3 activation, increasing proapoptotic proteins BAK/BAX, decreasing anti-apoptotic BCL-2, and leading to mitochondrial intrinsic (3) and extrinsic (2) apoptotic pathway by activating FAS, caspase 8, and caspase 3. It may be that plant extract activates the FAS-caspase 8 pathway directly (2). (4) ER-stress mediated apoptosis pathway. Increasing ROS level and/or E. bicolor plant extract led to ER stress. ER-stress activates XBP1s, which activates CHOP leading to XBP1s-CHOP-mediated apoptosis. (5) E. bicolor diterpene extract downregulates the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. The question mark (?) signifies that TRPV1 may or may not be involved in triggering apoptotic pathways depending on E. bicolor diterpene extract concentrations. Created with BioRender.com.

Figure 11.

Proposed model of the mechanisms of action of E. bicolor diterpene extract on triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Plant extract activates TRPV1, inducing calcium influx into cells. The elevated intracellular calcium triggers several apoptotic pathways, such as the mitochondria mediated intrinsic, extrinsic, and ER-stress mediated pathways. (1) Accumulation of Ca2+ in mitochondria causes the transient depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential. As a result, the mitochondrial permeability transition pores (MPTPs) open and release cytochrome c (cyt c), leading to caspase activation, increasing proapoptotic proteins BAK/BAX, decreasing anti-apoptotic BCL-2, thus leading to apoptosis. (2) Calcium influx through TRPV1 triggers the extrinsic pathway by activating FAS, caspase 8, and caspase 3, leading to apoptosis. (3) Plasma membrane TRPV1 activation and calcium influx lead to ER stress. ER TRPV1 becomes another source of calcium release in the cell. ER stress activates XBP1s, which activates CHOP, leading to XBP1s-CHOP-mediated apoptosis. (4) E. bicolor diterpene extract downregulates the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. (5) Plant extract increases cellular ROS levels triggering several apoptotic pathways.

Figure 11.

Proposed model of the mechanisms of action of E. bicolor diterpene extract on triple-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Plant extract activates TRPV1, inducing calcium influx into cells. The elevated intracellular calcium triggers several apoptotic pathways, such as the mitochondria mediated intrinsic, extrinsic, and ER-stress mediated pathways. (1) Accumulation of Ca2+ in mitochondria causes the transient depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential. As a result, the mitochondrial permeability transition pores (MPTPs) open and release cytochrome c (cyt c), leading to caspase activation, increasing proapoptotic proteins BAK/BAX, decreasing anti-apoptotic BCL-2, thus leading to apoptosis. (2) Calcium influx through TRPV1 triggers the extrinsic pathway by activating FAS, caspase 8, and caspase 3, leading to apoptosis. (3) Plasma membrane TRPV1 activation and calcium influx lead to ER stress. ER TRPV1 becomes another source of calcium release in the cell. ER stress activates XBP1s, which activates CHOP, leading to XBP1s-CHOP-mediated apoptosis. (4) E. bicolor diterpene extract downregulates the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. (5) Plant extract increases cellular ROS levels triggering several apoptotic pathways.