1. Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the many common malignant tumors that affect women[

1]. Numerous internal and external factors contribute to the development and occurrence of breast cancer[

2]. The milk duct is often the site of emergence; lobules are the site of less serious cases. Cancers that affect the ductal region are referred to as ductal carcinomas, and those that affect the mammary lobules are known as lobular carcinomas[

3]. Triple-negative breast cancers, or TNBCs, are considered aggressive forms of breast cancer and result from reduced expression of the human growth factor receptor 2 as well as the progesterone and estrogen receptors[

4]. Natural recurrence occurs in TNBCs, which account for 12–17% of all breast cancer cases. Compared to other subtypes of breast cancer, their clinical behavior is comparatively more aggressive. Furthermore, TNBCs account for 24% of newly diagnosed breast cancers, and their incidence has been reported to be steadily rising. These cancers also have poor prognoses and typical metastatic patterns where the average survival rate is approximately 10.2 months; for regional tumors, the 5-year survival rate is 65%, and for tumors that have spread to distant organs, it is 11%[

5,

6,

7]. Globally, the incidence of breast cancer is increasing along with the disease's burden, making breast cancer an important public health concern[

8]. Due to population growth and aging, it is predicted that the incidence of breast cancer will increase by more than 40% by 2040, reaching roughly 3 million cases annually. In a similar vein, over 50% more people will die from breast cancer in 2040[

9]. Breast cancer has been linked to several established risk factors, such as late menopause, advanced age at first birth, fewer children, decreased breastfeeding, menopausal hormone replacement therapy, oral contraceptives, alcohol consumption, and excess body weight[

10].

The use of phytonutrients, also known as nutraceuticals and herbal medicines, is still growing worldwide, with many people turning to these products in various national healthcare settings to treat various health issues. For years, herbal remedies have been used as anticancer medications. They also have anti-inflammatory properties and many anticancer ingredients that have been shown to have direct cytotoxic effects and indirect actions on the tumor microenvironment, cancer immunity, and chemotherapy progression[

11,

12]. From 200 to 1800 AD, according to Aristotle and Galen's teachings, cancer was thought to be caused by the coagulation of "black bile." Until recently, when the prevalence of biology has led to a 25% decrease in mortality, herbs were crucial in managing cancer symptoms and improving the quality of life and survival of patients with the disease[

13]. Compared to conventional chemical drugs, herbal medicine fights cancer in a significantly different way, as it prevents DNA mutation in surviving cells. Another benefit of herbal medicines is that they can create an environment that is unfavorable to the growth of cancer[

14].

The

Mandragora autumnalis plant has been prized as one of the most significant medicinal plants and has had great cultural significance as an herb since ancient times. It was remarkably used throughout history.

Mandragora has a wide range of uses, including medicinal, hallucinogenic, and boosting ovulation. Furthermore,

Mandragora autumnalis possesses a narcotic effect, which is most likely caused by the presence of an alternative form of alkaloids[

15]. The plant genus

Mandragora, a member of the Solanaceae family, is commonly known as "mandrake". Historically, various parts of the

Mandragora species, including the root, fruit, and leaves, have been used to treat conditions like ulcers, inflammation, sleeplessness, and eye health issues. The mandrake plant has been used for centuries as a valuable and traditional herbal medicine; however, little research has been conducted on its biological activity and potential phytochemicals [

16,

17,

18].

In this work, we used Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) analytical examination and qualitative assays to examine the phytochemical composition of Mandragora autumnalis ethanolic leaf extract (MAE). Using the MDA-MB-231 cell line, we also investigated the anticancer potential of MAE by examining its effects on cell proliferation, the induction of apoptosis, and various hallmarks of cancer metastasis on a molecular level, including adhesion, invasion, cell cycle, angiogenesis, migration, and aggregation in TNBC.

3. Discussion

Plants and plant-derived metabolites still have major roles in the development of drugs for the prevention or treatment of diseases. Currently, there is growing interest in screening plants to identify therapeutic agents. However, there are scarce investigations on the therapeutic potential of its therapeutic bioactivities. Plant-derived drugs are the source of many of the current cancer chemotherapy agents[

37]. In this context, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authorized three herbal mixture-based treatments, including antiallergenic, anticancer, and anti-psoriatic medications, in recent years[

38]. Plants are rich in secondary metabolites with a variety of biological functions that are essential to the growth and development of the plant, in addition to serving as a reservoir of phytochemicals that shield the plant from environmental constraints and aid in adaptation. It is well known that many of these secondary metabolites have potent anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and antioxidant therapeutic qualities[

39]. However,

Mandragora autumnalis's medicinal potential has not been thoroughly studied. In this current study, we assessed the ethanolic extract of

Mandragora autumnalis (MAE) for antioxidant potential. We used LC-MS to qualitatively and quantitatively analyze the phytochemical composition of the extract. Furthermore, we examined MAE's potential as an anticancer agent by evaluating its impact on key indicators of cancer, such as adhesion, aggregation, invasion, migration, and proliferation, compared to the aggressive triple-negative breast cancer cell subtype and the underlying molecular mechanisms. Numerous classes of phytochemical compounds, such as flavonoids, phenols, tannins, steroids, and essential oils, were found in MAE, according to the qualitative phytochemical analysis. Our findings concur with earlier research indicating the presence of coumarins and lipid-like compounds in extracts from

Mandragora species[

17]. As a result of its capacity to scavenge DPPH radicals, the ethanolic extract of

Mandragora autumnalis demonstrated good antioxidant potential in vitro[

40,

41]. Moreover, phenols and flavonoids are recognized for their anticancer activity, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant function[

42]. The LC-MS profiling of the tested plant extract revealed a diverse set of bioactive phytochemicals, many of which have been documented in other medicinal plants for their promising anticancer properties, particularly against triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). TNBC is an aggressive breast cancer subtype lacking estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors, often exhibiting poor prognosis and limited therapeutic options[

43]. Hence, phytochemicals capable of multi-targeted anticancer action offer significant therapeutic value. In this study, the LC-MS analysis revealed a diverse profile of bioactive compounds, including alkaloids (hyoscyamine, tropine, tropinone, solacaproine), phenolic acids (chlorogenic acid), flavonoids (quercetin, chrysin), fatty acid derivatives (hexadecanamide, ethyl palmitate, linoleic acid, ethyl linolenate), and esters (ethyl hydrocinnamate, ethyl 3-hydroxybutanoate). Similar phytochemical compositions have been reported in medicinal plants like

Datura stramonium,

Atropa belladonna, and

Withania somnifera, which are known for their rich alkaloid and flavonoid contents, targeted anticancer therapies. Among the major identified compounds, chlorogenic acid, scopoletin, caffeic acid, rutin, hyperoside, and linolenic acid have garnered substantial interest for their roles in inhibiting TNBC cell viability and metastasis. For instance, chlorogenic acid—widely found in

Coffea arabica,

Lonicera japonica, and

Solanum nigrum—has demonstrated the ability to suppress TNBC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through the modulation of key signaling pathways such as NF-κB and PI3K/Akt[

44]. In MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells, chlorogenic acid downregulated MMP-9 expression and induced apoptosis, suggesting its chemopreventive potential[

45]. Scopoletin, found in

Morinda citrifolia,

Artemisia absinthium, and

Scopolia carniolica, appeared at high intensities in the sample, indicating a major role in bioactivity. This coumarin compound has been reported to inhibit TNBC cell growth by inducing oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis and enhancing chemosensitivity[

46]. Rutin and hyperoside, both flavonol glycosides, are common in

Sophora japonica,

Ginkgo biloba, and

Hypericum perforatum and exhibit anticancer potential by inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a critical event in TNBC metastasis. Rutin has also shown synergistic effects with doxorubicin in reducing TNBC tumor burden[

47]. Similarly, hyperoside inhibits the proliferation and migration of MDA-MB-231 cells by regulating miRNA expression and downregulating MMPs. Additionally, 3-methyl-2,5-furandione, a furan derivative, though less studied, shares structural similarity with compounds known for antiproliferative effects and may represent a novel candidate for anti-TNBC activity[

48]. Collectively, the presence of these compounds, many of which are found in medicinal plants traditionally used in cancer therapy, supports the potential of this extract as a multi-targeted approach against cancer, especially TNBC.

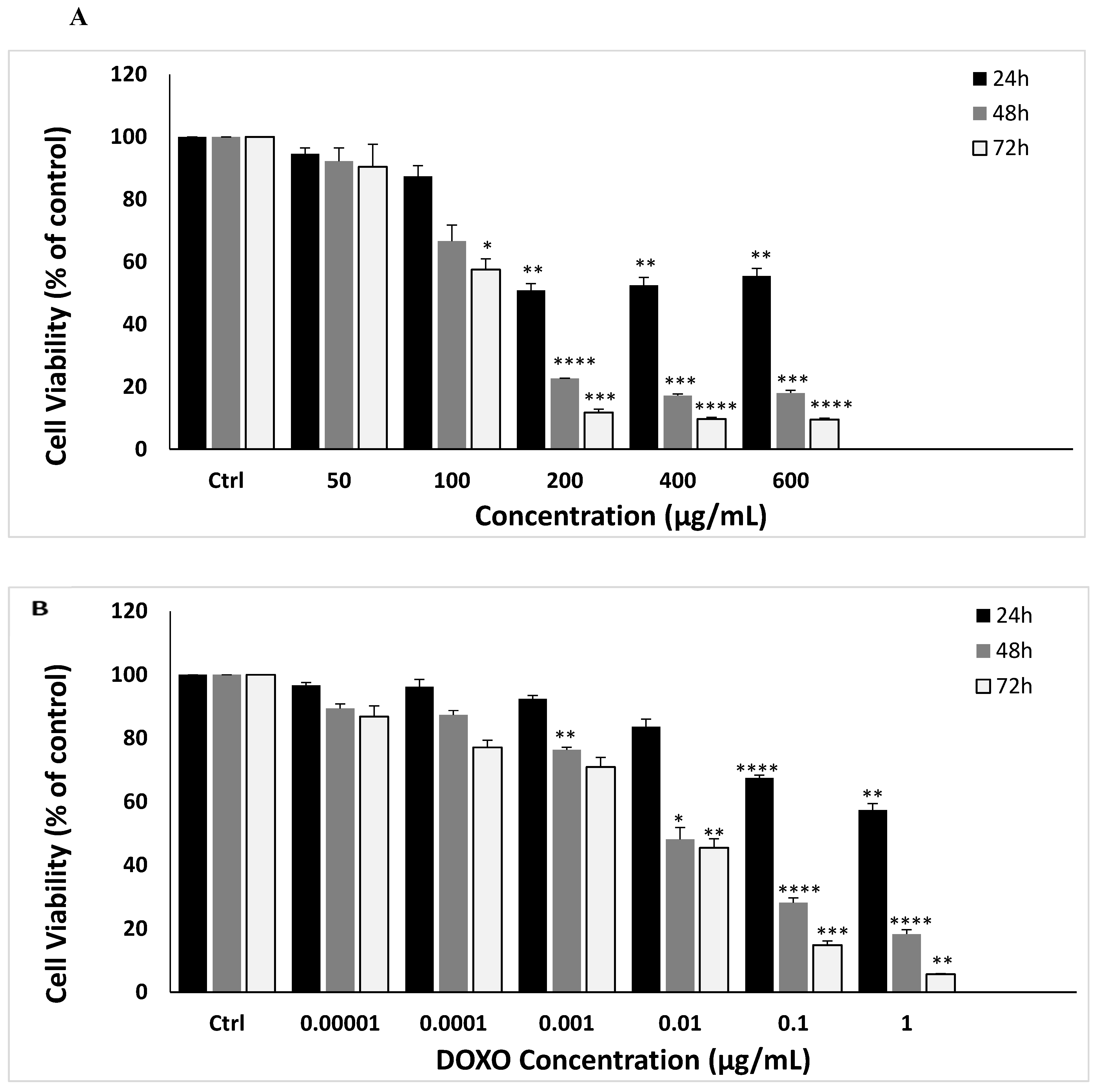

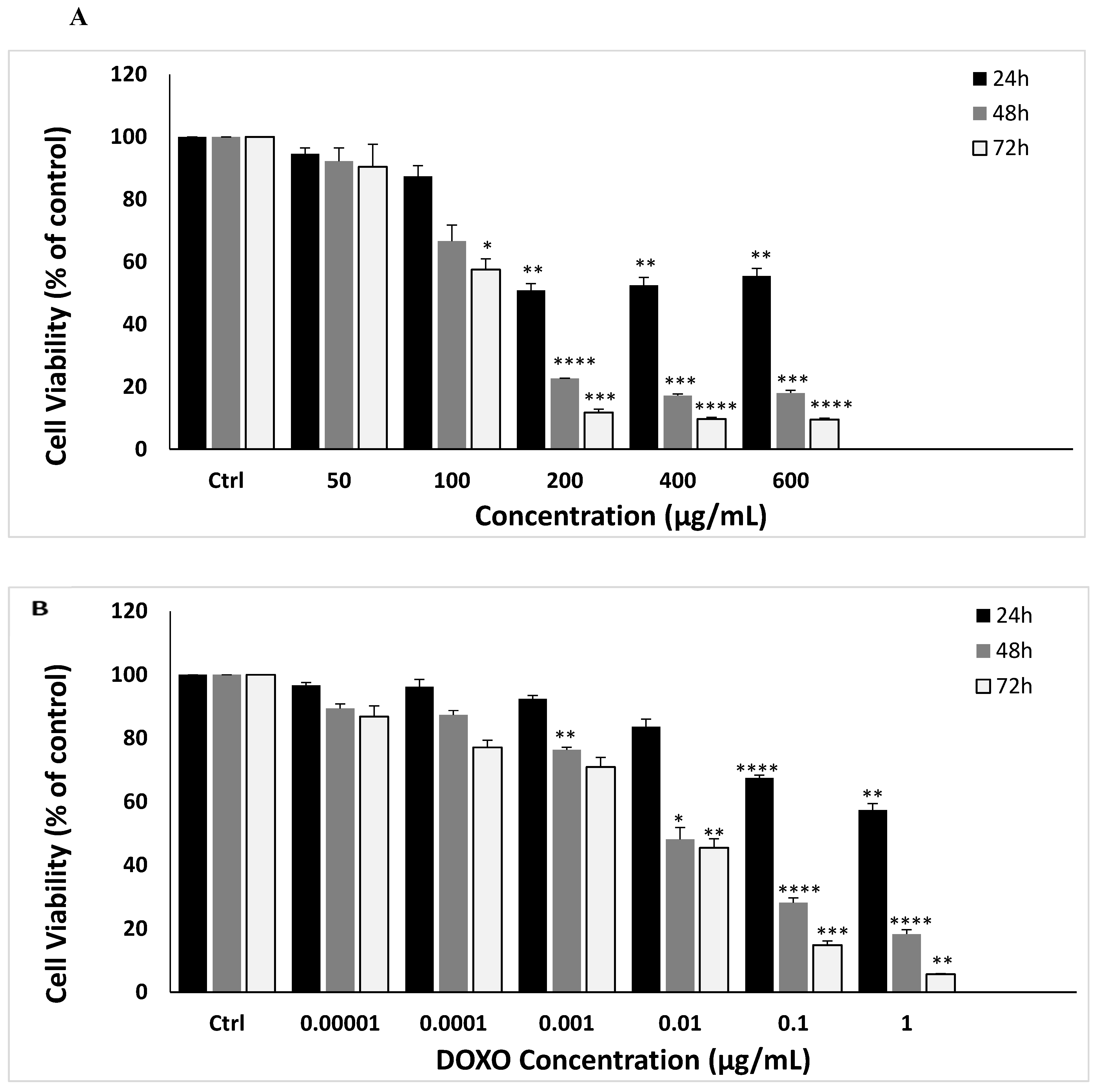

Cancer is marked by uncontrolled proliferation, resulting from improper cell division and death regulation[

49]. We found that MAE extract had significant anti-proliferative activity against MDA-MB-231 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. This coincided with a substantial decrease in Ki67, a highly expressed proliferation marker that correlates with tumor severity[

50]. Inducing apoptosis is an effective strategy for controlling cancer cell proliferation, and targeting apoptotic pathways is becoming increasingly important in cancer treatment development [

51]. To better understand the anti-proliferative mechanism of the MAE extract, we studied apoptosis induction. MAE significantly inhibited MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. Previous research has shown that

Mandragora autumnalis inhibits the proliferation of various cancer cell lines [

15]. This study is the first to evaluate the impact of MAE on the triple-negative subtype of breast cancer, including its underlying molecular mechanisms and cancer phenotypes.

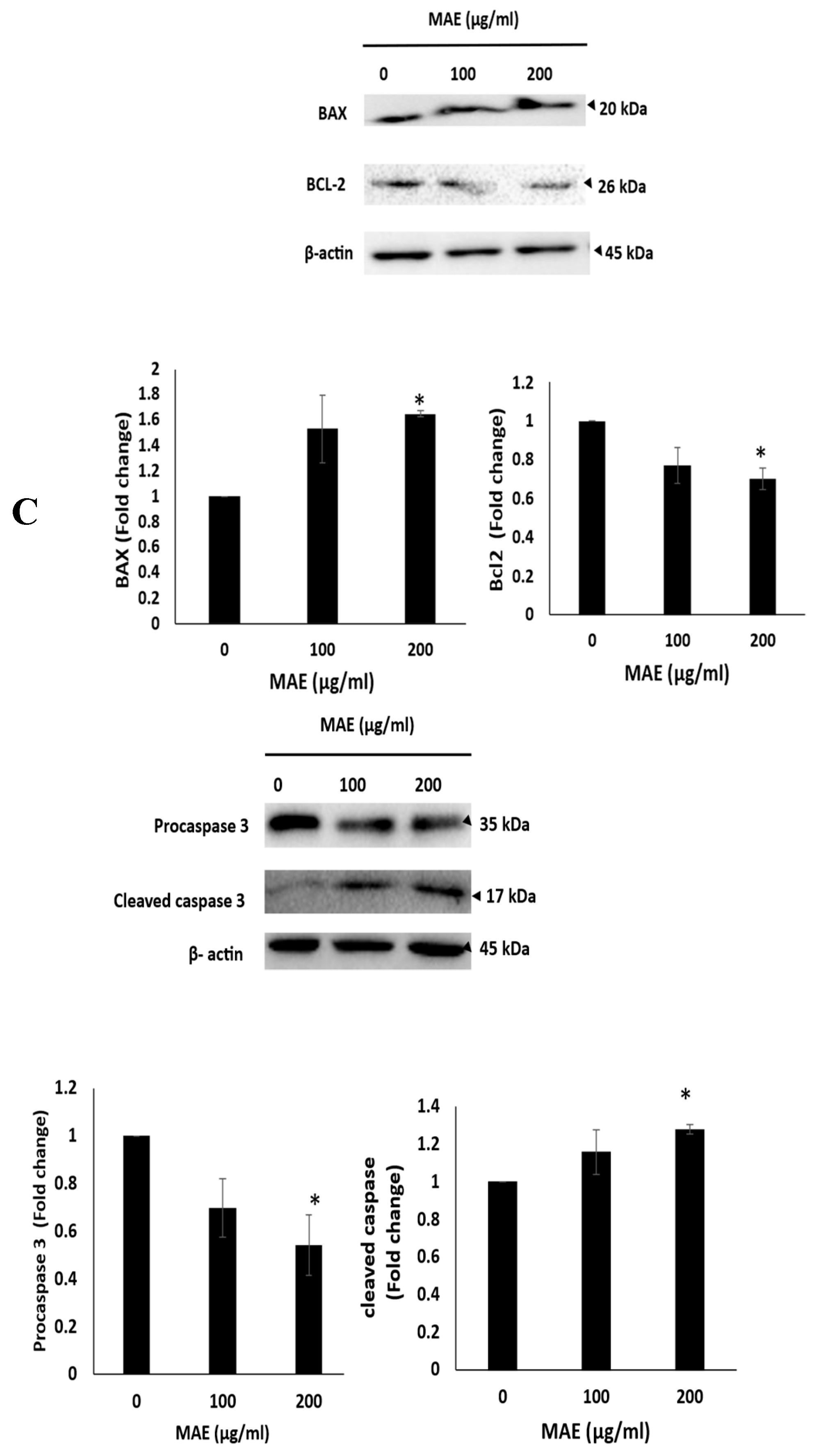

In cancer therapy, inducing apoptosis in cancer cells is an essential tactic in addition to preventing unchecked proliferation [

52]. TNBC is among the cancer cells that frequently avoid apoptosis, which promotes tumor growth and treatment failure[

53]. Consequently, activating apoptotic pathways is a highly effective method of treating cancer. The downregulation of pro-caspase 3, the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein, and the upregulation of the pro-apoptotic Bax protein and caspase 3 in our investigation all suggested that MAE induced intrinsic apoptosis. This comes in line with previous studies on other plant extracts, including

Ziziphus nummularia, and

Haludule uninervis, on triple-negative breast cancer cells[

54,

55].

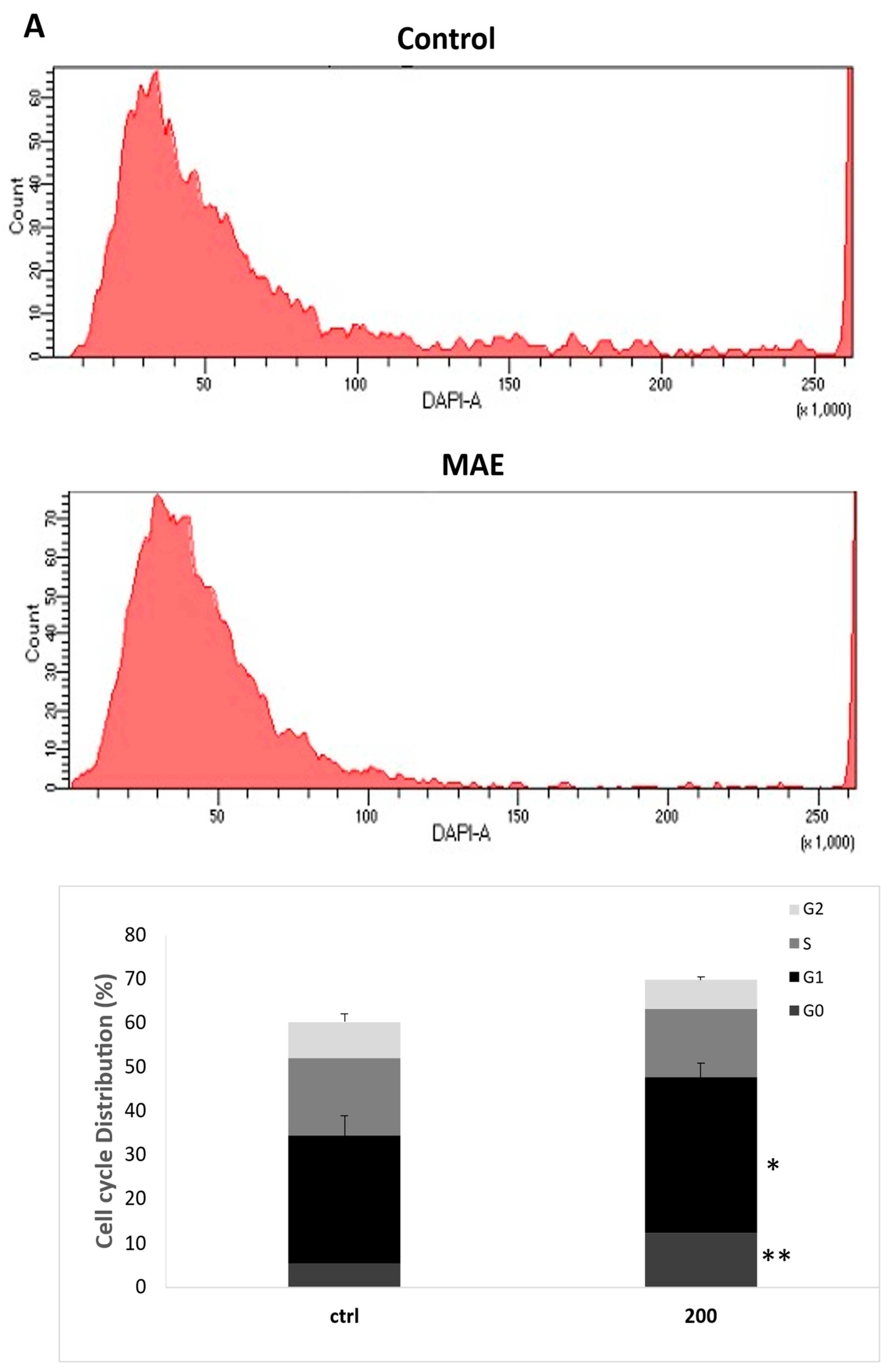

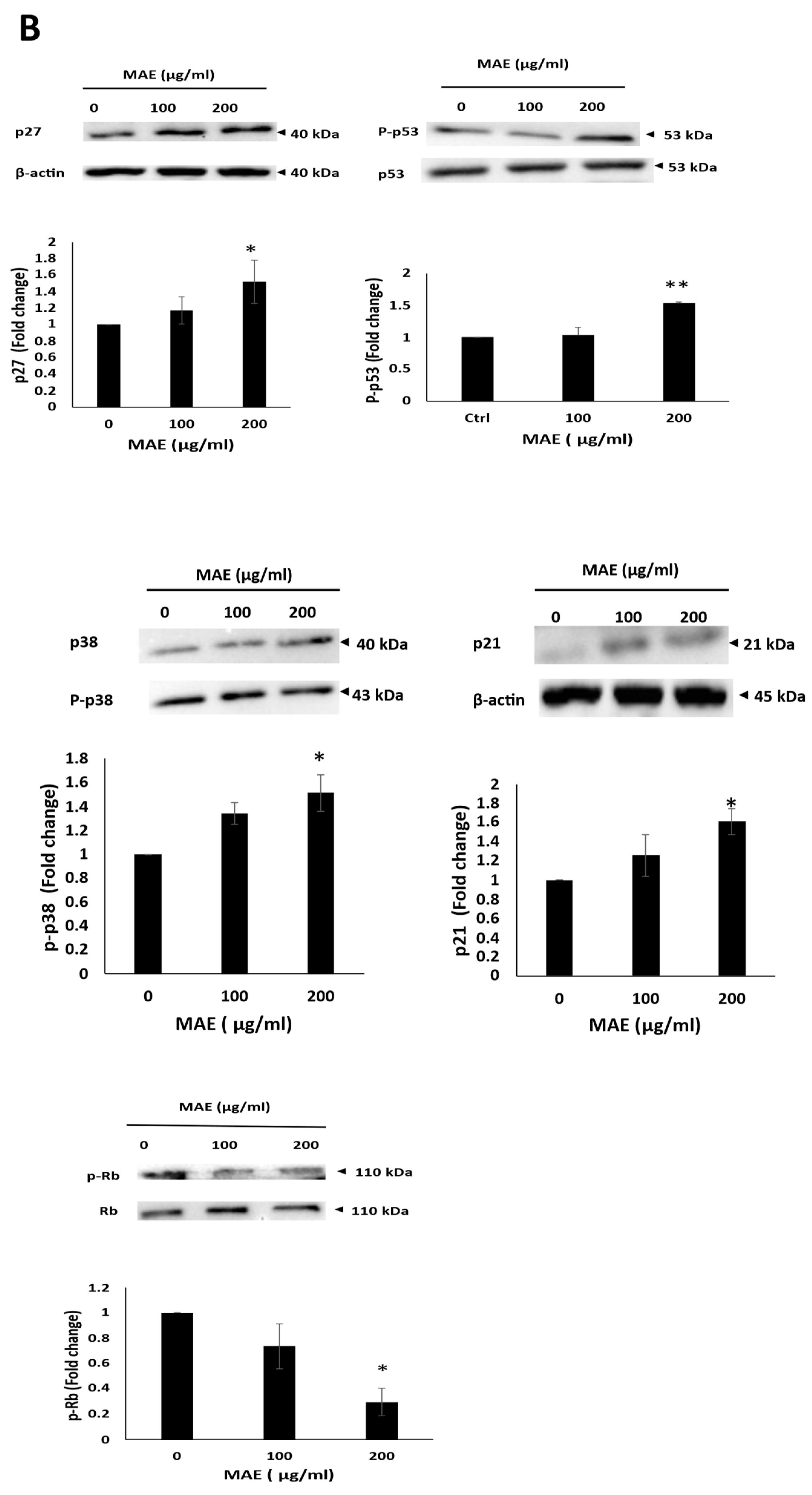

Additionally, the p53 pathway was investigated to better understand the mechanism of MAE's anti-proliferative effects. p53 is a tumor suppressor protein encoded by the TP53 gene; its primary biological function appears to be to protect the DNA integrity of the cell. TP53 has additional functions in development, aging, and cell differentiation [

56,

57]. Activated p53 promotes cell cycle arrest to allow DNA repair and apoptosis to prevent the spread of cells with severe DNA damage by transactivating target genes involved in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis[

58]. Mutations in the p53 gene (mtp53) are associated with a variety of cancers, including 70-80% of TNBC [

59]. Interestingly, the phosphorylation of Ser15 (mediated primarily by the ATM and ATR protein kinases in response to genotoxic stress) acts as a nucleation event that promotes or permits subsequent sequential modification of many residues[

60]. Furthermore, ATM-induced phosphorylation promotes the recruitment of histone/lysine acetyltransferases (HAT), such as p300 and CBP, resulting in the acetylation of multiple lysine residues in p53's DNA binding (DBD) and carboxy-terminal domains. These modifications are thought to contribute to the stabilization of p53 by blocking ubiquitylation and suggest that p53 restores its tumor-suppressive activity[

61]. MAE induced p53 phosphorylation in MDA-MB-231 cells, potentially restoring its wild-type conformation and increasing transcriptional activity. This suggests a promising therapeutic strategy for preventing cancer cell proliferation. Moreover, to gain insight into the mechanism of MAE-induced anti-proliferative effects, the involvement of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway was investigated. P38 is known to play a crucial role in maintaining cellular homeostasis by regulating various cellular processes, including cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and cellular response to stress[

62]. Our results showed that MAE increased the levels of p38, which is by other studies reporting the relationship between p38 activation and the induction of cell cycle arrest[

63]. In addition to that, the levels of the cell cycle inhibitor protein p21, a downstream effector of p38, and p27 were significantly increased by MAE. Moreover, MAE significantly reduced the phosphorylation of Rb, further implicating the p38 MAPK pathway in the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells. This can be explained by the activation of p38 MAPK, which stabilizes CDK inhibitors (e.g., p21 and p27) , delaying Rb phosphorylation, which keeps Rb in its active, growth-suppressing form and causes cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase[

64,

65]. As a result of TNBC, increasing the levels of activity of p27, p21, p38, Rb, and p53 leads to a significant extension of the G0 and G1 phases of the cell cycle, preventing cancer cells from entering the DNA synthesis S phase. This cell cycle arrest is a desirable therapeutic effect, as it limits tumor cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis or senescence. Targeting this network of tumor suppressors and stress response proteins holds promise for developing more effective treatments for TNBC, which currently lacks targeted therapies.

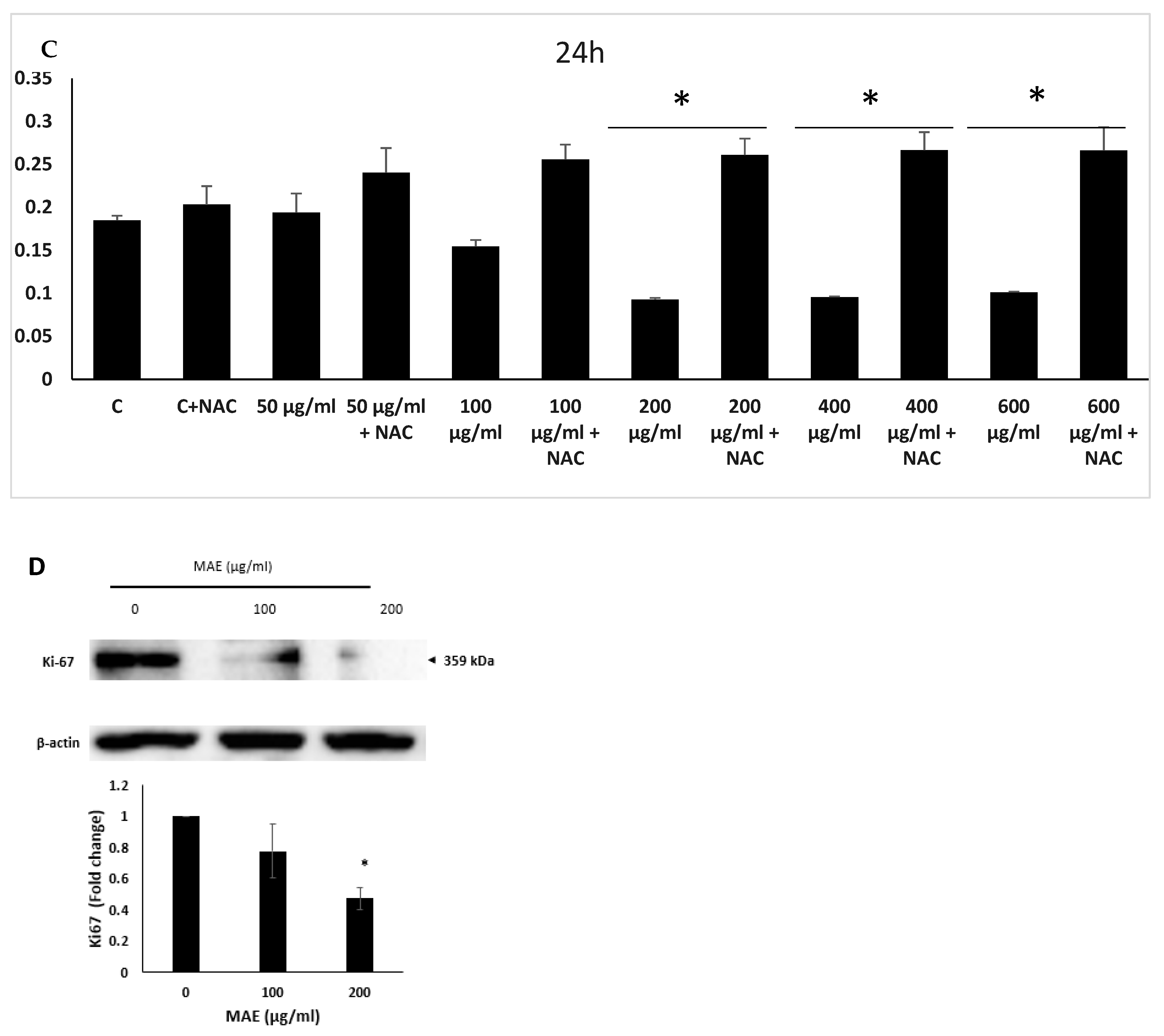

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are elevated in nearly all cancers, where they support various aspects of the growth and spread of the tumor. The delicate regulation of intracellular ROS signaling to efficiently rob cells of ROS-induced tumor-promoting events and tip the scales in favor of ROS-induced apoptotic signaling will present a challenge for innovative therapeutic approaches. On the other hand, therapeutic antioxidants may stop critical early stages of tumor development before ROS are produced[

66]. In this study, MAE reduction of MDA-MB-231 viability was attenuated by suppressing ROS levels with a potent antioxidant like NAC. All of these points to a scenario in which MAE causes ROS levels to rise, which in turn triggers anti-proliferative signaling pathways in MDA-MB-231 cells. It's possible that this signaling involves the ROS-p53 axis. Similar findings stated that when hysapubescin B, a withanolide derived from

Physalis pubescens, was applied to HCT116 colorectal cancer cells, it produced reactive oxygen species (ROS) that inhibited mTORC1, which in turn activated autophagy and caused cell death[

67] Notably, MAE stimulates the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), suggesting that MAE contributes to oxidative stress in MDA cells. One of the main causes of DNA damage and a threat to genomic integrity is oxidative stress, which activates members of the p53 family, most notably p53, which is essential for tumor suppression[

68]. Upcoming experiments using p53 inhibitors and ROS scavengers should provide insight into the mode of interaction between ROS and p53, including whether p53 acts upstream or downstream of ROS or whether there is a bidirectional crosstalk.

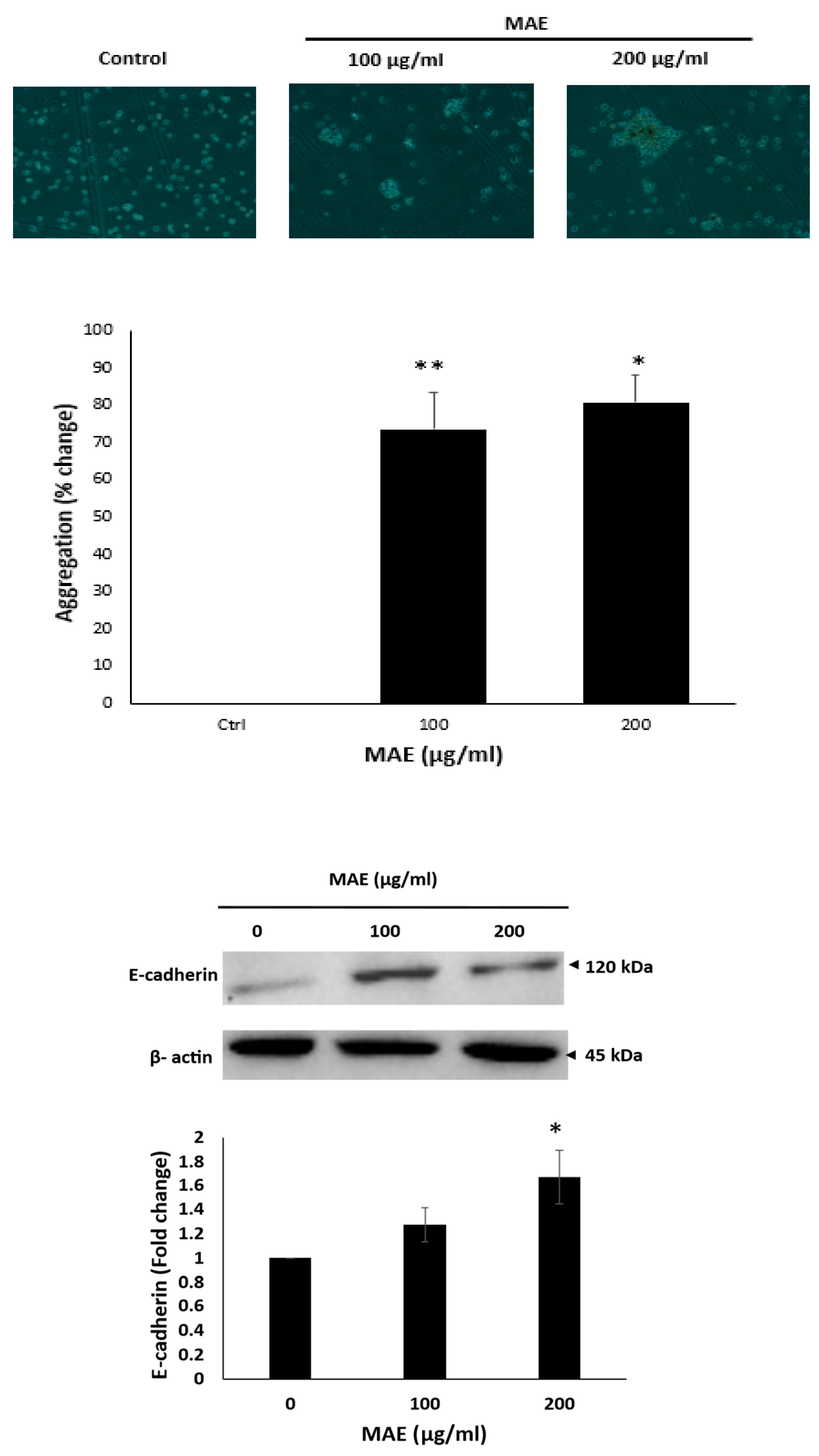

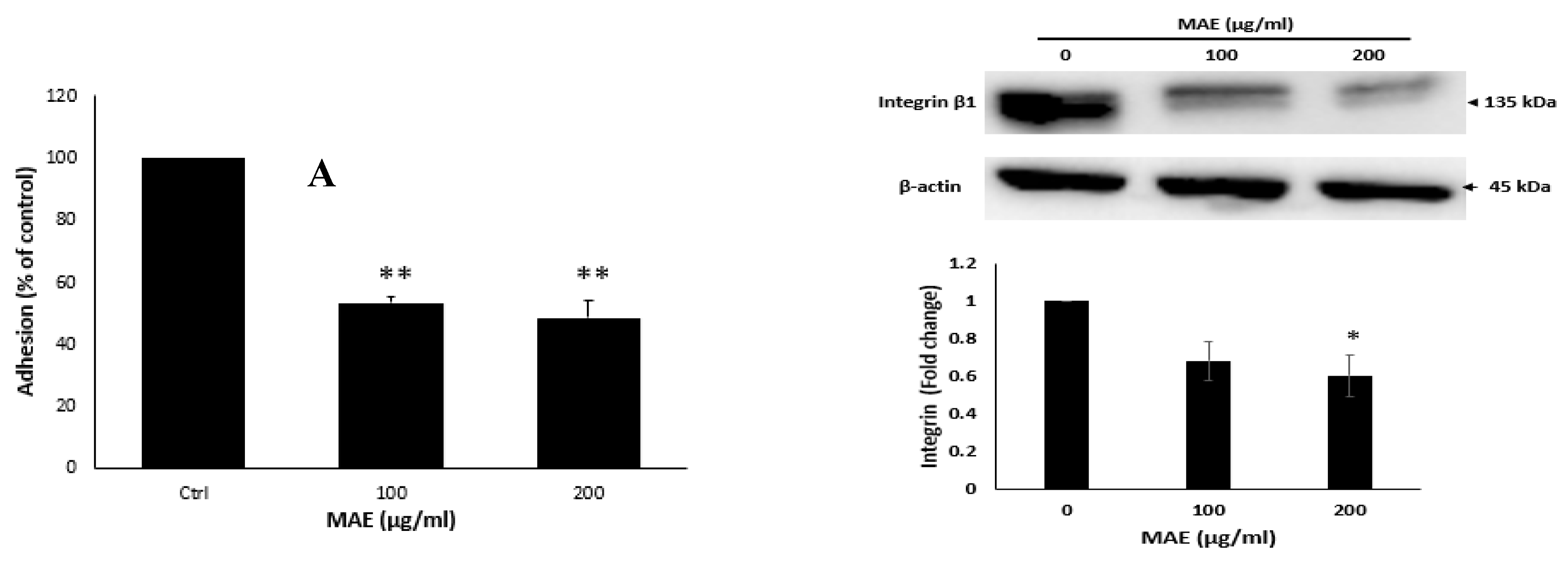

Furthermore, we demonstrated that MAE impacted MDA's ability to migrate and adhere to one another. These functions are essential to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and serve as a marker of the cancer's spread to metastases. Cancer cells can migrate and invade more areas with less cell-to-cell adhesion[

69].

Our study's results showed that treating MDA extract with MAE increased the creation of cell-cell aggregates and reduced their migration and invasion, reversing the EMT phenotype and preventing metastasis as a result. The complicated process of cancer metastasis involves the cancer cells moving from the main tumor site to other organs. It contributes to the spread of cancer and accounts for a sizable share of cancer-related mortality. Because of its aggressive nature, dismal prognosis, and resistance to treatment, TNBC metastasis poses a serious clinical challenge[

70]. Tumor cell invasion is commonly believed to require the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT); however, mounting data suggests that there are other pathways through which tumor cells can spread. Using mesenchymal or amoeboid dissemination mechanisms, tumor cells can spread individually or in clusters. Mesenchymal cells move forward through the production of traction force through integrin-mediated extracellular matrix adhesion and cytoskeletal contractility[

71]. With their elongated morphology, mesenchymal cells can move forward by producing traction force through integrin-mediated extracellular matrix adhesion and cytoskeletal contractility[

72]. The production of migration pathways by mesenchymal tumor cells is also dependent on proteolysis-dependent ECM degradation[

73]. It has been determined that epithelial tumor cells can acquire mesenchymal phenotypes through the use of EMT and hybrid EMT. However, in the absence of proteolysis-dependent ECM remodeling, amoeboid cells with a rounded and deformable morphology can fit through small pores and narrow spaces in the ECM[

74]. High-speed movement is produced during this kind of movement when the cells display bleb-like protrusions powered by actomyosin contractility and maintain weak but dynamic cell adhesion to ECM[

75]. Collective cell migration is a movement pattern of multiple cells that maintain cell-cell connections and migrate in unison, as opposed to single-cell motility[

76].Actin dynamics, integrin-based ECM adhesion, and proteolytic cleavage of ECM are the three factors that control this kind of tumor cell migration. The diverse tumor cells that migrate in cohesive groups preserve front-rear polarity and collaborate hierarchically [

77]. The increase in cancer cell migration and invasion is partly due to the dysregulation of cell-cell adhesion and the extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation by metalloproteinases (MMPs)[

78]. The MDA-MB-231 cells' ability to adhere to collagen was reduced by MAE treatment, suggesting that the cell-ECM interaction had been disrupted. Furthermore, MAE reduced the amounts of integrin β1, an adhesion molecule linked to TNBC's heightened invasiveness and aggression [

79]. These findings support MAE's capacity to suppress TNBC cells' capacity to spread by focusing on cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions. Boyden chamber and wound-healing assays were used in our study to examine the impact of MAE on the migration and invasion characteristics of MDA-MB-231. In this study, TNBC cell migration and invasion were markedly inhibited by MAE. Multiple investigations involving various plant extracts have demonstrated that the inhibition of MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression diminishes the migratory and invasive potential of MDA-MB-231 cells[

80]. In our investigation, MAE significantly and concentration-dependently decreased the MDA-MB-231 cells' cell-cell adhesion.

This was accompanied by a decrease in integrin β1 protein levels, suggesting that MAE could block tumor migration by inhibiting cell-to-cell adhesion. All things considered, MAE may be able to reduce TNBC metastasis by reducing cell-–ECM contact, preventing cell migration, adhesion, and invasion, and boosting cell-cell aggregation. More research is needed to determine whether the downregulation of MMPs mediates the MAE-induced inhibition of migration and invasion. The existence of multiple signaling pathways involved in cancer pathogenesis emphasizes the need for additional research[

81,

82]. Despite progress in cancer research, providing more involved pathways and molecular targets is very important[

83]. STAT3, in particular, plays important roles in a variety of cellular processes, including the cell cycle, cell proliferation, cellular apoptosis, and tumorigenesis[

84]. Persistent activation of STAT3 has been reported in a variety of cancer types, and a poor prognosis of cancer may be associated with the phosphorylation level of STAT3[

85]. STAT3 promotes tumor progression and metastasis in TNBC by regulating gene expression-related apoptosis, EMT, cell migration, aggregation, and invasion. STAT3 can be tightly controlled by upstream signaling molecules like Janus kinase (JAK) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)[

86]. It then localizes to the nucleus of cells and binds to target DNA, regulating the expression of subsequent proteins. However, in addition to its normal cell functions, STAT3 activation in the tumor microenvironment (TME) is considered an oncogenic event. High phospho-STAT3 expression is linked to a poor prognosis in cancer patients[

87]. STAT3 constitutive activation is critical for tumor formation, development, metastasis, and recurrence. These are strongly associated with cancer hallmarks and lead to poor patient outcomes[

88]. Therefore, the STAT3 pathway is a promising target for cancer therapy. Based on previous findings it has been shown that plant-derived compounds can reduce cancer by inhibiting the STAT3 signaling pathway and its associated genes. As an example, Baicalein and Cantharidin inhibit the STAT3 pathway via downregulating of IL6 and EGFR levels respectively. Moreover, Hydroxy-jolkinolide B, Deoxy-2β,16-dihydroxynagilactone E, Acetoxychavicol acetate inhibit triple negative breast cancer cells by downregulating of JAK/STAT pathway[

88].It has been demonstrated that phosphorylated STAT3 (p-STAT3), which was significantly decreased by MAE, downregulates important pro-metastatic factors like matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) which was significantly decreased, effectively inhibits tumor growth. When activated, the transcription factor p-STAT3 moves into the nucleus and stimulates the expression of genes related to invasion, metastasis, and cell survival. MMP-9, an enzyme that breaks down extracellular matrix components to promote cancer cell invasion and metastasis, is one of its well-established targets[

89]. Thus, blocking STAT3 phosphorylation results in a decrease in MMP-9 expression[

90], which in turn reduces TNBC cells' capacity for invasion which was achievedieved by MAE in this investigation. In order to reduce tumor aggressiveness and enhance outcomes for patients with TNBC, this regulatory axis emphasizes the therapeutic potential of targeting the STAT3/MMP-9 pathway.

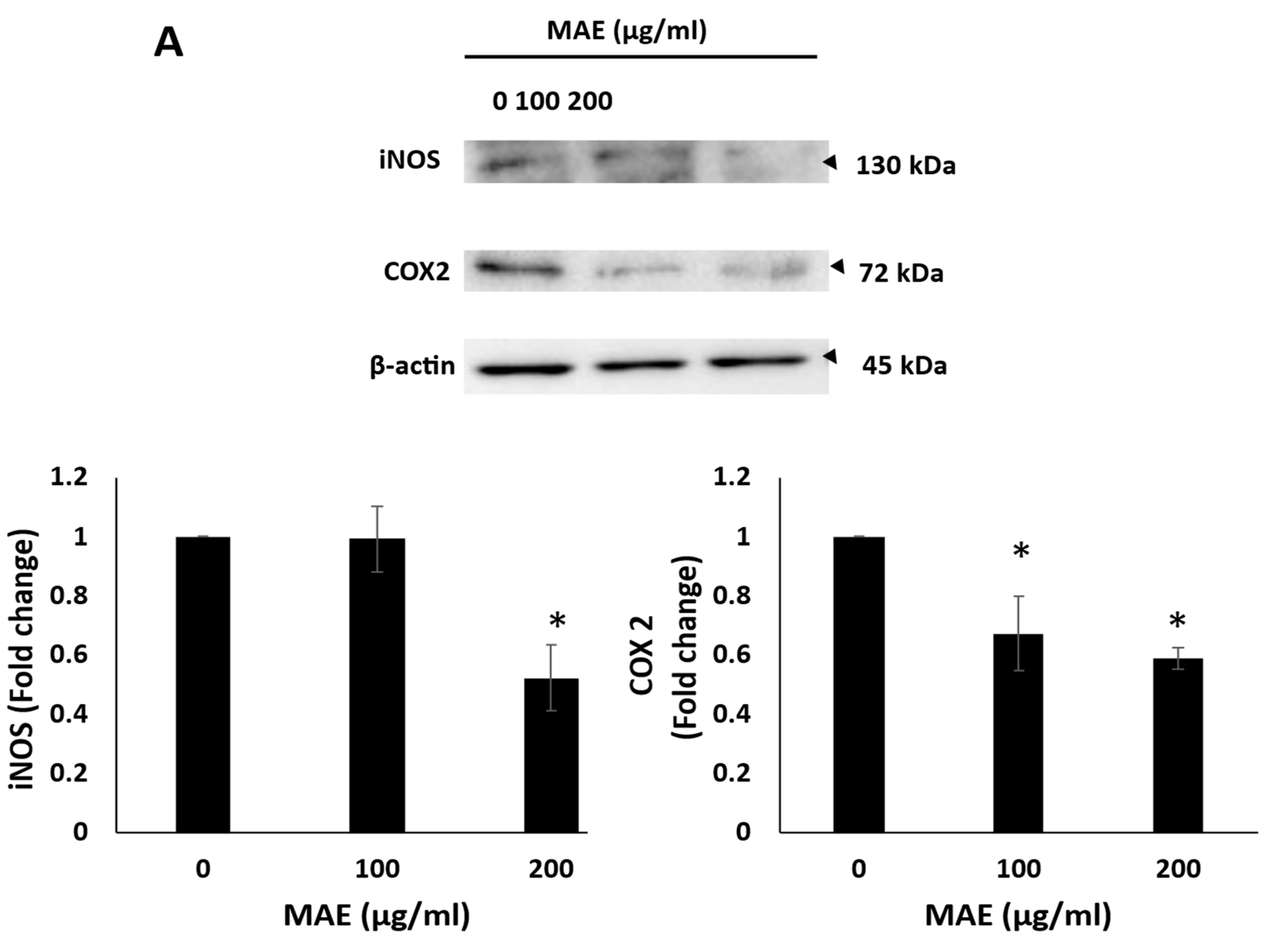

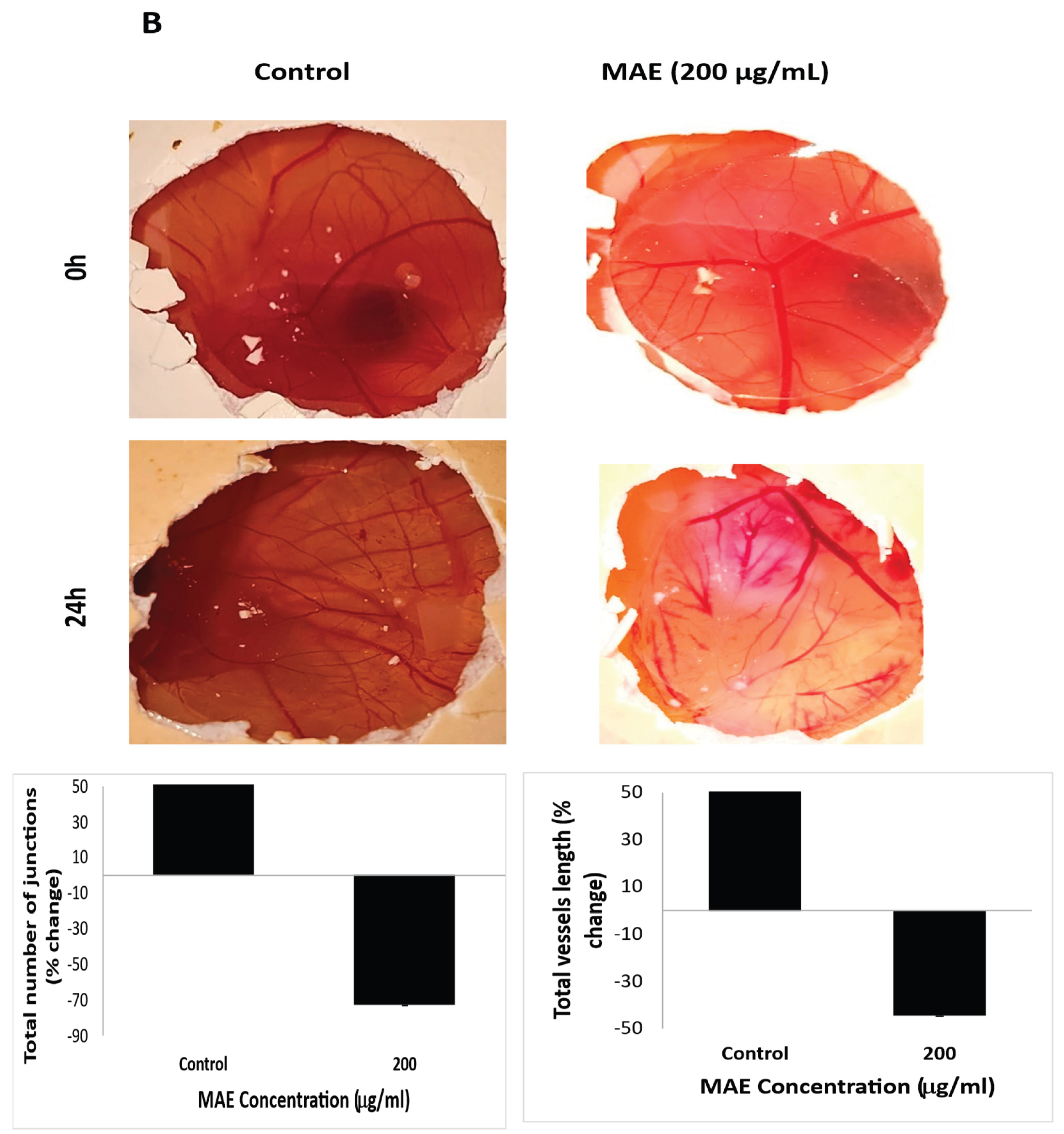

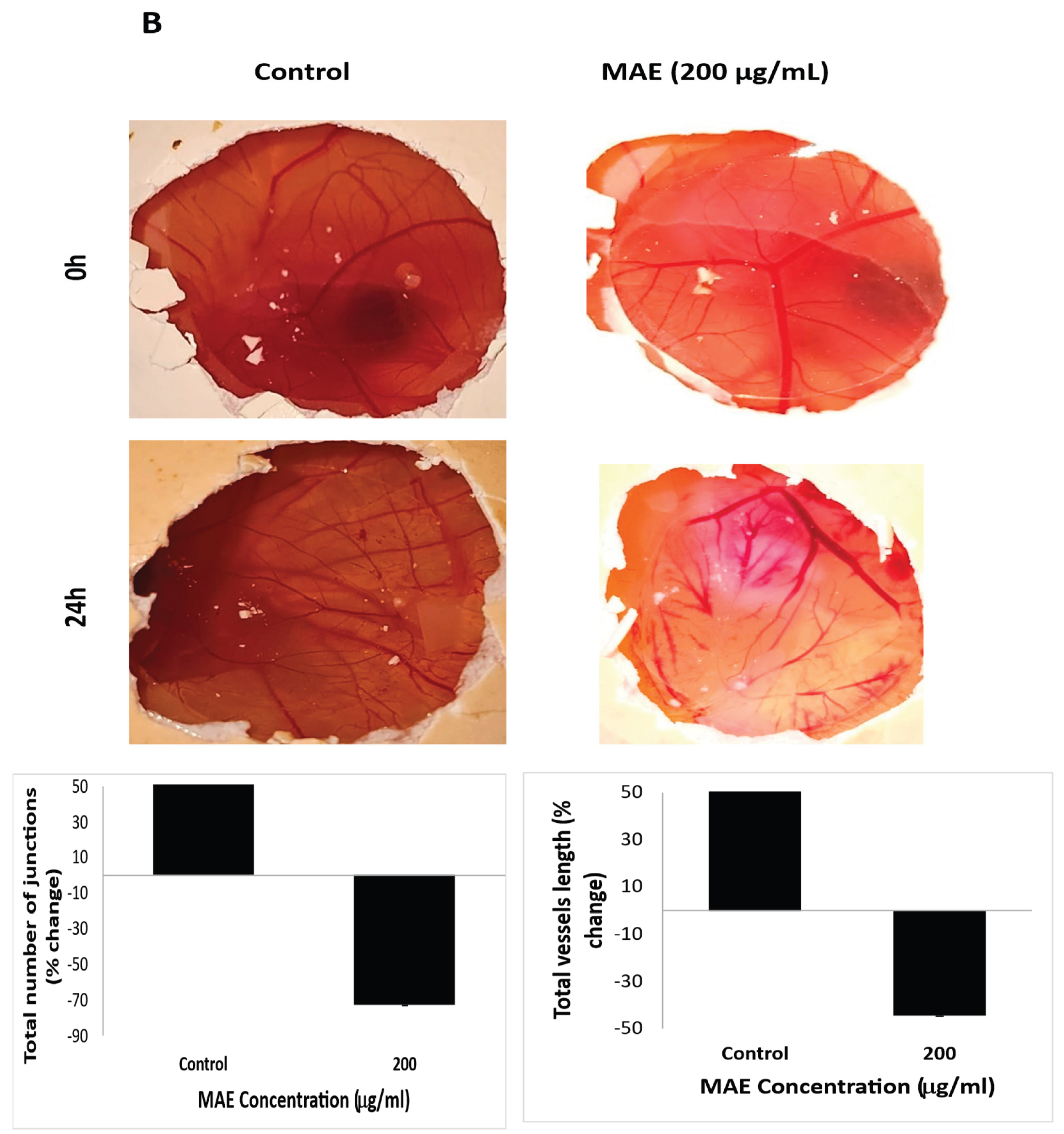

The development of new blood vessels, or angiogenesis, is a crucial step in the growth, invasion, and metastasis of tumors[

91]. Particularly, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) has high angiogenic activity, which promotes fast tumor growth and makes metastasis easier. Therefore, blocking pro-angiogenic factors to target angiogenesis has become a promising therapeutic strategy for controlling the progression of TNBC[

92]. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) are two important pro-angiogenic enzymes that are upregulated in TNBC. In TNBC, their overexpression increases the risk of metastasis and vascularization[

93]. Notably, treatment with MAE decreased the expression of COX-2 and iNOS in MDA-MB-231 cells. Additionally, in the chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay, MAE significantly reduced vessel length and the number of junctions, demonstrating a strong anti-angiogenic effect in vivo-like environment. These results are in line with earlier studies that demonstrated that

Halodule uninervis , a seagrass, also inhibits angiogenesis in TNBC[

55].

As a sum up, Effective therapeutic responses in TNBC are frequently characterized by downregulation of survival and invasion markers (e.g., Bcl-2, p-STAT3, MMP-9) and upregulation of pro-apoptotic and tumor suppressor proteins (e.g., Bax, caspase-3, p21, p27, p-p53). Increases in E-cadherin and decreases in integrin/MMP-9 indicate that EMT and metastasis are suppressed. All markers studied in this investigation were listed with their change and proposed role after treatment with MAE (

Table 4).

Per these findings, MAE inhibited apoptosis, adhesion, migration, invasion, cell cycle, and angiogenesis in MDA-MB-231 cells. Our research concludes that there are numerous significant plant phytochemicals in the ethanolic extract of Mandragora autumnalis leaves, many of which have been shown to have pharmacological properties. Additionally, we showed that the extract has potent anti-metastatic and anti-cancer characteristics, which may help to lessen the malignant phenotype of TNBC. The carcinogenesis process's hallmarks, such as cell proliferation, cell aggregation, cellular adhesion, migration, and invasion, were all impacted by MAE. This calls for additional investigation into MAE and the isolation of the bioactive metabolites responsible for the reported anticancer effects. These investigations could identify MAE as a new source of innovative drug candidates.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Collection of Mandragora autumnalis Leaves and Preparation of their Ethanolic Extract MAE

Mandragora autumnalis leaves were collected during the spring season from south Lebanon. The leaves were cleaned and dried at room temperature. The plants were identified by Mohammad Al-Zein, a resident plant taxonomist at the American University of Beirut (AUB) herbarium. A voucher specimen has been stored at the Post Herbarium, AUB, with identification number GA 2025-1. Leaves were washed and dried at room temperature and ground mechanically. The powder was suspended in 80% ethanol and incubated while shaking at 40 rpm in the dark for 72 hours. Afterward, the suspension was filtered using filter paper and lyophilized using a freeze-dryer. The obtained powder was dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 100 mg/mL. The prepared plant extract MAE was then stored in the dark at 4 °C for further usage and analysis.

4.2. Phytochemical Analysis

The chemical composition of the Mandragora autumnalis ethanolic and aqueous extracts was investigated by performing qualitative tests to detect the presence of primary and secondary metabolites. Test for anthocyanins: A total of 0.5 g of the extract was dissolved in 5 mL of ethanol, followed by ultrasonication for 15 min at 30 ◦C. Subsequently, 1 mL of each extract was combined with 1 mL of NaOH (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) and heated for 5 min at 100 ◦C. The presence of anthocyanins was indicated by the appearance of a bluish-green color. Anthraquinone test: 0.5 g of each extract (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 4 mL of benzene. 10% ammonia solution was added to the filtrate following filtration. The presence of anthraquinones was verified by the formation of a red or violet color. Test for cardiac glycosides: 5 mL of ethanol was used to dissolve 0.5 g of each extract. This was then ultrasonicated at 30 °C, filtered, and evaporated. Subsequently, the dehydrated extract was combined with 1 milliliter of glacial acetic acid (from Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) and a few drops of 2% FeCl3. Subsequently, the test tube's side was filled with 1 milliliter of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) from Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA. The appearance of a brown ring indicated the presence of cardiac glycosides. To test for essential oils, 0.5 g of each extract was dissolved in 5 mL of ethanol, then the mixture was ultrasonically sonicated at 30 °C and filtered. 100 µL of 1MNaOH was mixed with the filtrate. A tiny amount of 1MHCl (MERCK, Darmstadt, Germany) was then added. A white precipitate's formation indicated the presence of essential oils. Test for flavonoids. One milliliter of 2% NaOH and 0.2 g of each extract were combined. When a concentrated, yellow-colored solution was achieved, a few drops of diluted acid were added to the mixture. The color in the solution vanished, indicating that flavonoids were present. Phenols test: 5 mL of ethanol was used to dissolve 0.5 g of each extract, which was then ultrasonically sonicated at 30 °C and filtered. A mixture of 2 mL distilled water and the filtrate was prepared. Subsequently, a small amount of 5% FeCl3 was added, and this caused a dark green color to form, indicating the presence of phenols. 5 mL of ethanol was used to dissolve 0.5 g of the extract, which was then ultrasonicated at 30 °C and filtered. The filtrate was then mixed with 1 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4). The development of a red hue was indicative of the presence of quinones. To test for tannins, dissolve 0.5 g of each extract in 5 mL of distilled water, then filter and ultrasonicate at 80 °C. Once the filtrate had cooled to room temperature, five drops of 0.1% FeCl3 were added. A brownish-green or blue-green coloration suggested the presence of tannins. To test for terpenoids, dissolve 0.5 g of the extract in 5 mL of chloroform, then filter and ultrasonicate at 30 °C. The filtrate was then mixed with 2 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4). The creation of a reddish-brown hue indicated the presence of quinones.

4.3. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

With a few minor modifications, the Folin–Ciocalteu method was used to determine the total polyphenol content (TPC) of MAE[

94]. The concentration of both extracts was made to be 1 mg/mL. 500 μL of the extract was separated, combined with 2.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, and left to oxidize for five minutes. After adding 2 mL of a 75 g/L sodium carbonate solution to neutralize the reaction, the mixture of the extract was left to incubate for 1 hour at 37° C in the dark. Following incubation, the samples' absorbance at 765 nm was compared to standards of gallic acid, which is a known polyphenol. The TPC of the extract was given as a percentage (mg GAE/g) of the total gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry leaves used in the extract's preparation. The TPC analysis was carried out three times, and the mean values ±SEM of the outcomes are shown.

2.4. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

Using a modified aluminum chloride colorimetric assay, the total flavonoid content (TFC) of MAE was ascertained[

94]. To put it briefly, a concentration of 1 mg/mL was used to prepare the extract. Then, an aliquot (0.5 mL) of the extract was combined with 1.5 mL of 95% ethanol, 2.8 mL of ultra-pure distilled water, 0.1 mL of a 10% methanolic aluminum chloride solution, and 0.1 mL sodium acetate. Using quercetin as a standard, the absorbance was measured at 415 nm following a 30-minute dark incubation period at room temperature. The TFC was measured in (mg QE/g) of quercetin equivalents per gram of dry leaves used to prepare the extract. Three runs of this analysis were conducted, and the results are shown as mean values ± SEM.

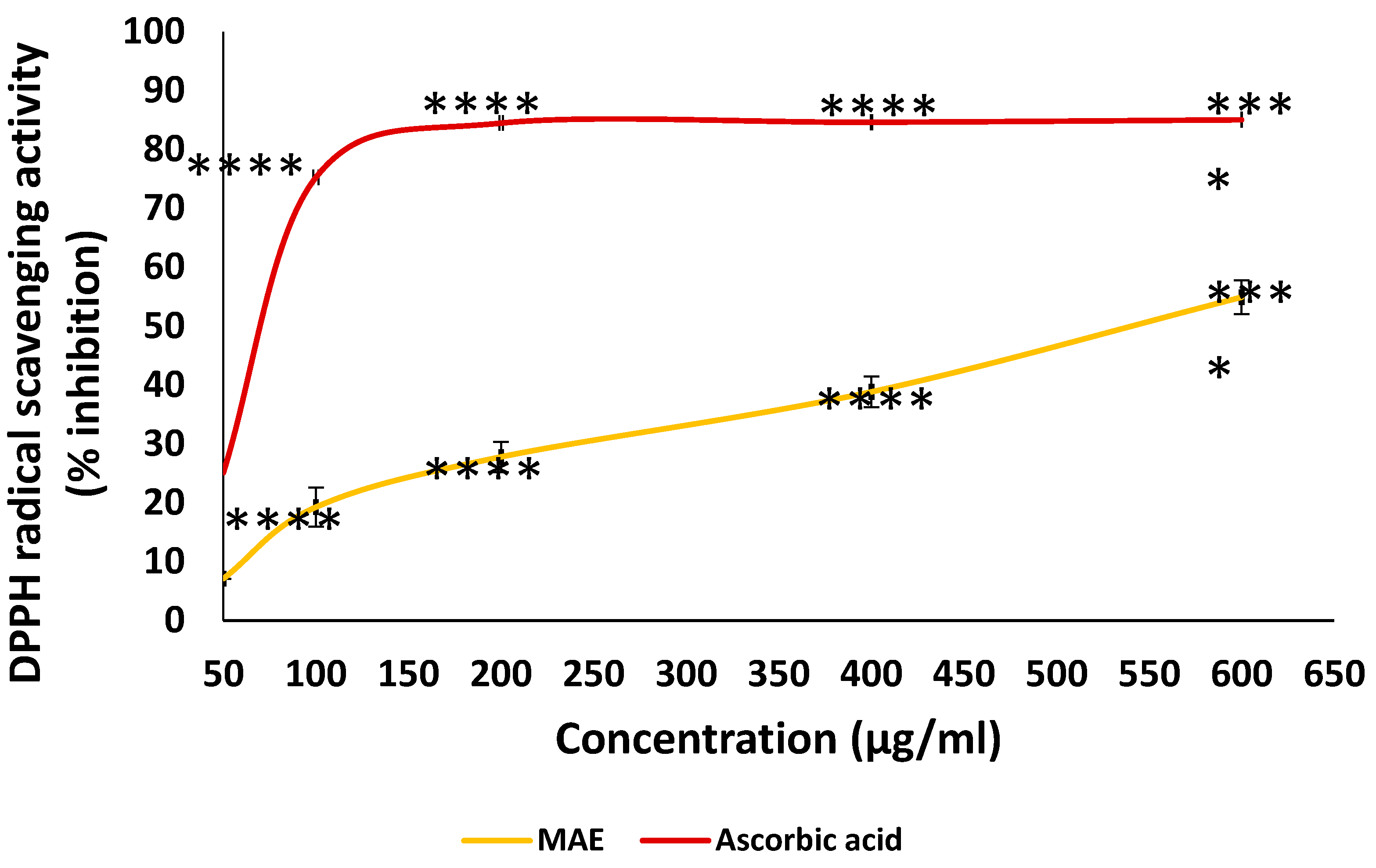

4.5. The antioxidant Activity (DPPH) of Mandragora autumnalis Ethanolic Extract

Using the free-radical-scavenging activity of α, α-diphenyl-α-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), the antioxidant activity of MAE was assessed. MAE at different concentrations (50, 100, 200, 400, or 600μg/mL) was combined with a 0.5 mM DPPH solution in methanol. DPPH solution (0.5 mL), methanol (3 mL), and 80% ethanol (0.5 mL) made up the blank solution, which was used for comparison. The combined samples were then exposed to darkness for 30 minutes, and a spectrophotometer was used to measure the optical density (OD) at a wavelength of 517 nm. The following formula was used to calculate the percentage of DPPH-scavenging activity for each MAE concentration. For comparison, ascorbic acid was used as the standard. Percentage of inhibition (absorbance of control − absorbance of the extract)/ (absorbance of control) × 100.

4.6. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

The Stock solution was prepared by dissolving 5 mg of the MAE sample in a solution of 50 µL of Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 450 µL of methanol, then 250 µL of the solution was diluted with 1 mL of methanol and then used for identification of the metabolite in the LC-MS system. All the other reagents, Acetonitrile, methanol, water, and formic acid, used were LC/MS grade. A Bruker Daltonik (Bremen, Germany) Impact II ESI-Q-TOF System equipped with Bruker Dalotonik. The Elute UPLC system (Bremen, Germany) was used for screening compounds of interest. We used standards for identification of m/z with high-resolution Bruker TOF MS and exact retention time of each analyte after chromatographic separation. This instrument was operated using the Ion Source Apollo II ion Funnel electrospray source. The capillary voltage was 2500 V, the nebulizer gas was 2.0 bar, the dry gas (nitrogen) flow was 8 L/min, and the dry temperature was 200 ºC. The mass accuracy was ˂ 1 ppm; the mass resolution was 50000 FSR (Full Sensitivity Resolution), and the TOF repetition rate was up to 20 kHz. using Elute UHPLC coupled to a Bruker Impact II QTOFMS. Chromatographic separation was performed using Bruker Solo 2.0_C-18 UHPLC column (100 mm x 2.1 mm x 2.0 μm) at a flow rate of 0.51 mL/min and a column temperature of 40 °C. Solvents:(A) water with 0.1% methanol and (B) Methanol injection volume 3 Μl. Data analysis was performed using Bruker's MetaboScape and DataAnalysis software. Compound annotation in MetaboScape was conducted using the MetaboBase library, a list of standards, as well as a custom list of previously reported compounds in the specific plant under investigation. The raw data files were converted to the mzML format using msConvert, a C++ tool from the ProteoWizard suite designed to convert raw files into standard mass spectrometry formats. The resulting mzML files were analyzed using an in-house R script based on the xcms, CAMERA, and MSnbase packages. Chemical formulas for annotated ions were generated and checked using the Rdisop package. The isotopic pattern for annotated chemical formulas matched the theoretical pattern with more than 99%. Chromatograms and spectra were generated using both Bruker Data Analysis and the ggplot2 library in R. The analyses performed using the two methods yielded comparable results.

4.7. Cell Culture

Human breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231 were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were cultured in a 37°C, 5% CO2 humidified chamber using DMEM high-glucose medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Corning, Massachusetts, United States).

4.8. MTT Cell Availability Assay

MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in a 96-well tissue culture plate at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well, and they were left to grow until 30% confluence was reached. The cells were subjected to escalating concentrations of MAE (50, 100, 200, 400, 600, and 1000 μg/mL) for 72 hours. The viability of the cells was assessed using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States). The viability of the cells was determined by comparing the proportionate viability of the treated cells to the vehicle-treated cells (equivalent concentration of DMSO), whose viability was assumed to be 100%.

4.9. Migration (Scratch) Assay

In 12-well plates, MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured until a confluent cell monolayer was formed. Next, a 10 μL pipette tip was used to create a scratch across the confluent cell monolayer. After removing the cell culture medium, the cells were cleaned with PBS to get rid of any debris. Following the addition of fresh medium containing MAE at the designated concentration (100, or 200 μg/mL), cells were incubated at 37°C. With an inverted microscope (objective ×4), photomicrographs of the scratch were taken at baseline (0 hours) and 10 hours post-scratch. Using the ZEN software (Zeiss, Germany), the width of the scratch was measured and expressed as the average difference ±SEM between the measurements made at time zero and the specified time point (10 hours).

4.10. Trans-Well Migration Assay

To test MDA-MB-231 cells' migratory potential, trans-well inserts (8 µm pore size; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) were employed. 3 × 105 cells were seeded into the insert's upper chamber. After that, cells were given the indicated MAE concentrations or not. A DMEM medium with 10% FBS was added as a chemoattractant in the lower chamber. After that, the cells were cultured at 37 °C and given 24 hours to migrate. The cells on the insert's upper surface were eliminated using a sterile cotton swab. Additionally, cells that moved to the insert's lower surface were stained with DAPI (1 µg/mL) and fixed with 4% formaldehyde. and examined for quantification at a 10× magnification using a fluorescence microscope. Three assay runs were conducted, and the results are shown as mean values ± SEM.

4.11. Matrigel Invasion Assay

To evaluate MDA-MB-231 cells' invasive potential, a BD Matrigel Invasion Chamber (8µm pore size; BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) was utilized. The experiment is comparable to the trans-well migration chamber assay, except that a diluted 1:20 Matrigel matrix is added. For quantification, cells that penetrated the Matrigel layer to the insert's lower surface were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, stained with DAPI, and examined under a fluorescence microscope. Three assay runs were conducted, and the results are shown as mean values ± SEM.

4.12. Aggregation Assay

MDA-MB-231 cells were collected from confluent plates using sterile 2 mM EDTA in Ca2+/Mg2+-free PBS to measure cell aggregation. The cells were divided into individual non-adherent culture plates and subjected to MAE treatment (100 or 200 μg/mL). After three hours of gentle shaking at 90 rpm and 37°C, the cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde. Photomicrographs were taken to be examined using an Olympus IX 71 inverted microscope.

4.13. Adhesion Assay

For a duration of 24 hours, MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured with or without different concentrations (100 or 200 μg/mL) of MAE. Following a collagen pre-coating, they were seeded onto 24-well plates and incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C. The MTT reduction assay was then used to determine the quantity of adherent cells after the cells had been washed with PBS to remove non-adherent cells.

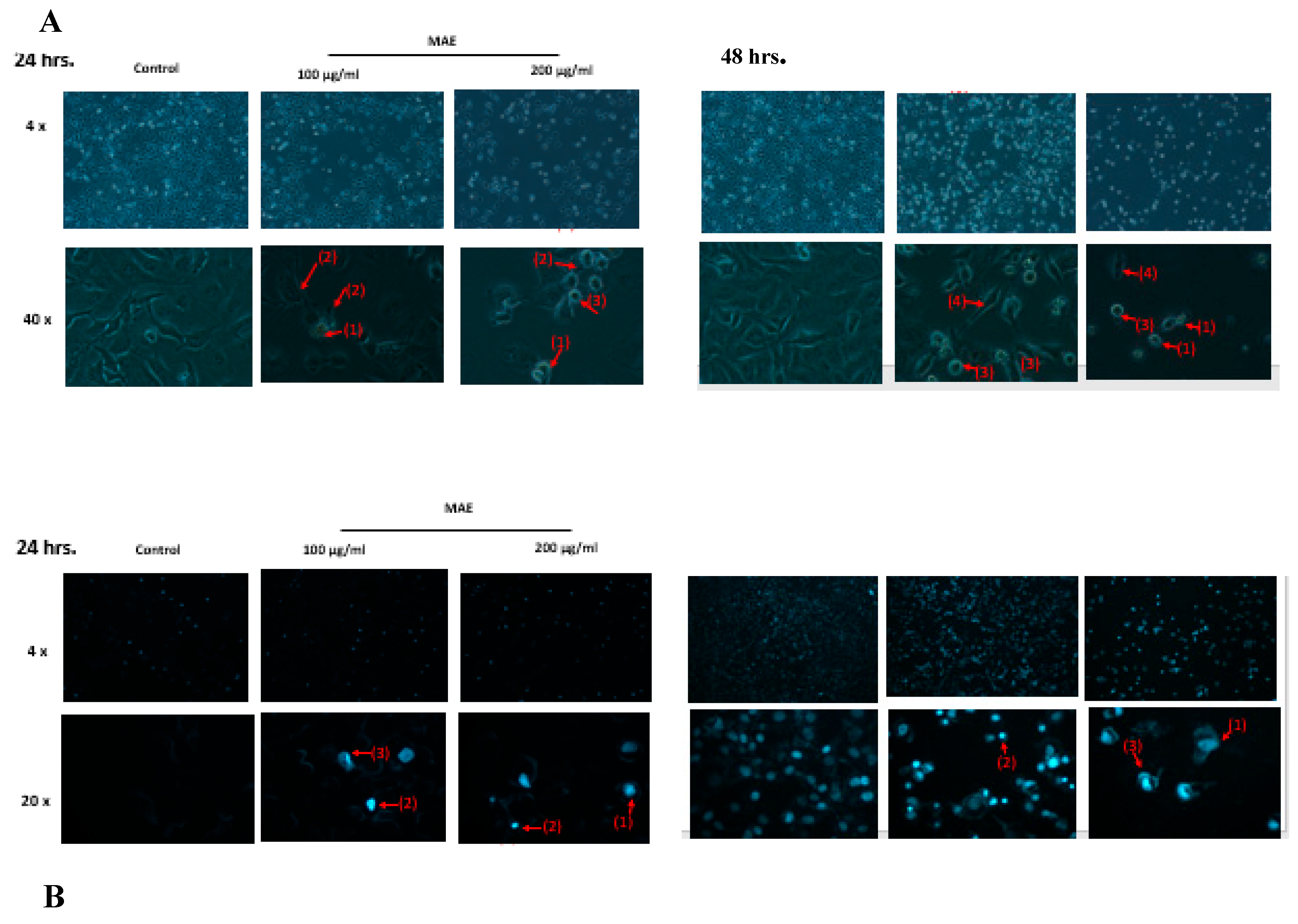

4.14. Analysis of Apoptotic Morphological Changes

Using a phase-contrast inverted microscope, characteristics associated with apoptotic cells were observed. For this, different concentrations of MAE (100 or 200 μg/mL) were either present or absent when growing cells in 6-well plates. After 24 hours, images at 4x, 10x, and 20x magnifications were captured. 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI) staining was used to identify changes in nuclear morphology indicative of apoptosis. For a full day, MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in a 12-well plate with or without the indicated concentrations of MAE (100 or 200 μg/mL). Following the manufacturer's instructions, the cells were stained with DAPI (Cell Signaling #4083), fixed with 4% formaldehyde, and then fluorescence microscopy was used to visualize the apoptotic morphological alterations.

4.15. Western Blot Analysis

To create whole-cell lysates, MDA-MB-231 cells were subjected to two PBS washes before being lysed in a lysis buffer that contained 60 mM Tris and 2% SDS (pH of 6.8). After that, the lysate mixture was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 1.5 × 104 g. Bradford protein quantification kit (Biorad, Hercules, CA, United States) was used to measure the amount of protein in the resultant supernatant. Protein extracts aliquots ranging from 25 to 30 μg were resolved using 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subsequently placed onto an Immobilon PVDF membrane (Biorad).

PVDF membrane was blocked with a 5% non-fat dry milk solution in TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20) for one hour at room temperature. To perform immunodetection, a particular primary antibody was incubated with the PVDF membrane for an entire night at 4°C. After removing the primary antibody and washing the membrane with TBST, the membrane was incubated for an hour with the secondary antibody, horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-IgG. Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) supplied an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate kit to visualize immunoreactive bands after washing the secondary antibody with TBST, by the manufacturer's instructions. Sourced from Cell Signaling (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, United States), all primary and secondary antibodies were used.

4.16. Gelatin Zymography

In a 100mm tissue culture plate, MDA-MB-231 cells (1.0 × 106) were cultivated in serum-free DMEM medium with or without varying concentrations (100, or 200 μg/mL) of MAE. The cultures' conditioned media were gathered and concentrated following a 24-hour incubation period. A 10% non-reducing polyacrylamide gel containing 0.1% gelatin was used to separate 30 µg of proteins. After electrophoresis, the gels were rinsed for one hour in 2.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 to get rid of SDS. They were then incubated for the entire night at 37°C in a solution that contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM ZnCl2, and 10 mM CaCl2 to enable the media's proteases to break down the gelatin substrate enzymatically. A 0.5% solution of Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 was used to stain the resultant gel. The gel showed clear patches that showed matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) breaking down the gelatin. Using ImageJ software, densitometry analysis was performed, and each cleared band's density was normalised to a nonspecific band on the gel that was equally loaded.

4.17. Flow Cytometry Analysis of Cell Cycle

MDA-MB-231 cells were cultivated in 100 mm tissue culture plates before incubating with or without MAE. Cells were extracted and then suspended in 500 µL of PBS after 24 hours. After that, the cells were fixed using an equivalent volume of 100% ethanol and maintained at -20°C for at least 12 hours. The cells were then centrifuged, pelleted, and washed with PBS before being resuspended in PBS containing 1 µg/mL of 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) and incubated at room temperature for half an hour. After that, the cell samples were evaluated using the Becton Dickinson BD FACSCanto II Flow Cytometry System (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and FACSDiva 6.1 software was used to facilitate data.

4.18. Chorioallantoic Membrane

Fertilized chicken eggs were cleaned with 70% ethanol, rotated, and incubated at 37 °C and 60% relative humidity. After a week, the air sac was revealed when the highly vascularized chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) was dropped by making an opening in the eggshell. The CAM was treated with 200 μg/mL of MAE and incubated for 24 hours to investigate its impact on blood vessel growth between treatment and control. AngioTool 0.5 software was then used to measure the lengths of the vessels and count the number of junctions in the CAM images that were taken.

4.19. Statistical Analysis

The results were assessed using the student's t-test. When comparing more than two means, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer's post hoc test were also utilized. P-values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

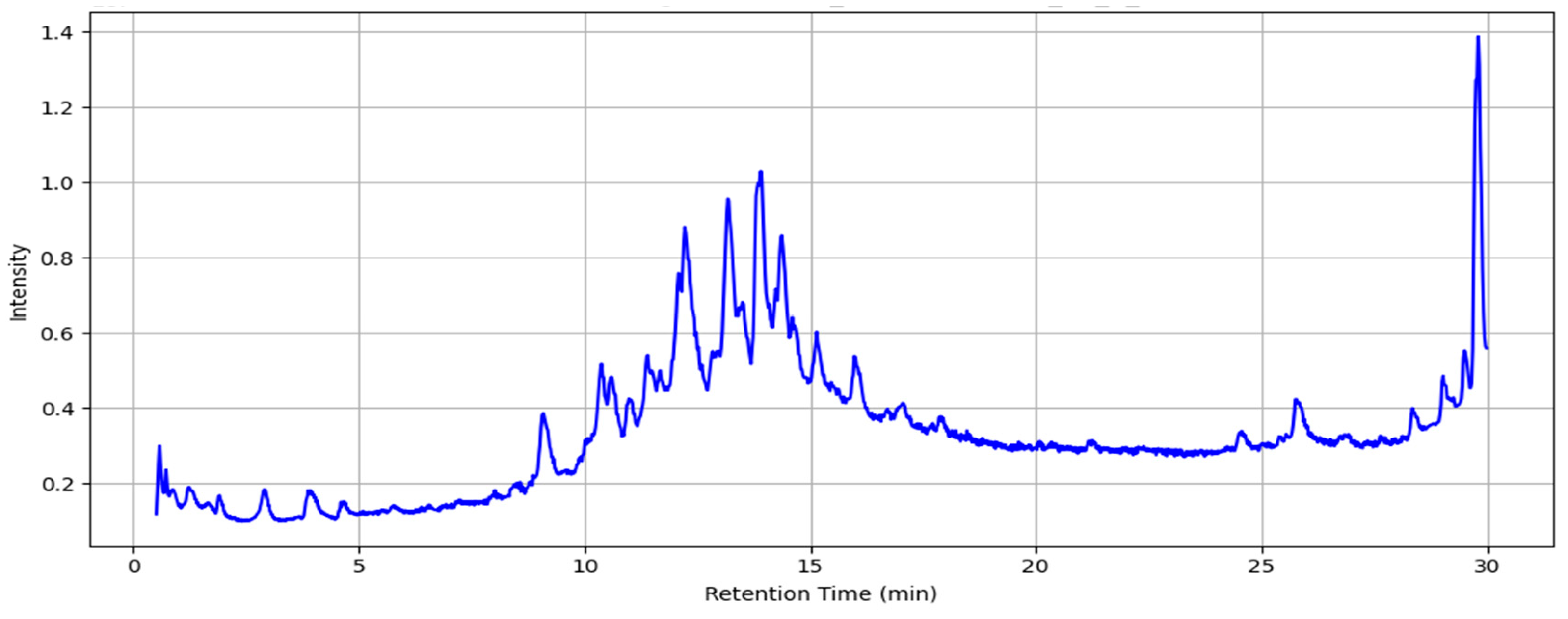

Figure 1.

Total ion chromatogram of MAE obtained using LC-MS (the intensity is multiplied by 10^7 a.u.).

Figure 1.

Total ion chromatogram of MAE obtained using LC-MS (the intensity is multiplied by 10^7 a.u.).

Figure 2.

The antioxidant capacities of various concentrations of MAE (50, 100, 200, 400, and 600 µg/mL) were measured using the DPPH free-radical-scavenging assay. The reference used was ascorbic acid. The values are displayed as the three experiments' average ± standard error (**** p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

The antioxidant capacities of various concentrations of MAE (50, 100, 200, 400, and 600 µg/mL) were measured using the DPPH free-radical-scavenging assay. The reference used was ascorbic acid. The values are displayed as the three experiments' average ± standard error (**** p < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

The cellular proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cancer cells is inhibited by MAE extract. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells received the indicated MAE concentrations for 24, 48, and 72 hours. The MTT assay, detailed in Materials and Methods, was used to assess the viability of the cells. The information is presented as a percentage and shows the mean ± SEM of three separate, triplicate experiments (n = 3), comparable control cells. (B) After 24, 48, and 72 hours of treatment, cell viability was assessed using either the vehicle control or the specified doxorubicin (DOXO) concentrations. (C) MDA-MB-231 cells were pre-treated with NAC (10 mM) for 30 min and then with MAE for 24 h. Values are expressed as % of the vehicle control and are represented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (D)The indicated concentrations of MAE (100 and 200 μg/mL) were incubated with and without MDA cells for 24 hours. After the cells were lysed, protein lysates were loaded with β-actin and subjected to Western blotting using a Ki67 antibody. The data are presented as a percentage of the corresponding control cells and show the mean ± SEM of three experiments (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, and the LSD post hoc test was used after (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

The cellular proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cancer cells is inhibited by MAE extract. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells received the indicated MAE concentrations for 24, 48, and 72 hours. The MTT assay, detailed in Materials and Methods, was used to assess the viability of the cells. The information is presented as a percentage and shows the mean ± SEM of three separate, triplicate experiments (n = 3), comparable control cells. (B) After 24, 48, and 72 hours of treatment, cell viability was assessed using either the vehicle control or the specified doxorubicin (DOXO) concentrations. (C) MDA-MB-231 cells were pre-treated with NAC (10 mM) for 30 min and then with MAE for 24 h. Values are expressed as % of the vehicle control and are represented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. (D)The indicated concentrations of MAE (100 and 200 μg/mL) were incubated with and without MDA cells for 24 hours. After the cells were lysed, protein lysates were loaded with β-actin and subjected to Western blotting using a Ki67 antibody. The data are presented as a percentage of the corresponding control cells and show the mean ± SEM of three experiments (n = 3). One-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis, and the LSD post hoc test was used after (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001).

Figure 4.

Changes in the morphology of cells were observed using light optical microscopy. Apoptotic bodies, echinoid spikes, membrane blebbing, and cell shrinkage are all indicated by arrows. (A) For 24 and 48 hours, cells were treated with either a vehicle-containing control or MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL). (B) After that, they were stained with DAPI so that fluorescence microscopy could be used to see changes in nuclear morphology. Photos were captured with a 10× magnification. Arrows depict chromatin lysis, nuclear condensation, and apoptotic bodies. (C) MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL) or a vehicle-containing control was used to treat the cells. Using Western blotting, the protein levels of procaspase 3, cleaved caspase 3, Bcl2, and Bax were ascertained. Loading control was established using β-actin. The three separate experiments' mean ± SEM (n = 3) is represented by the data. (*** indicates p < 0.001, and ** indicates p < 0.005).

Figure 4.

Changes in the morphology of cells were observed using light optical microscopy. Apoptotic bodies, echinoid spikes, membrane blebbing, and cell shrinkage are all indicated by arrows. (A) For 24 and 48 hours, cells were treated with either a vehicle-containing control or MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL). (B) After that, they were stained with DAPI so that fluorescence microscopy could be used to see changes in nuclear morphology. Photos were captured with a 10× magnification. Arrows depict chromatin lysis, nuclear condensation, and apoptotic bodies. (C) MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL) or a vehicle-containing control was used to treat the cells. Using Western blotting, the protein levels of procaspase 3, cleaved caspase 3, Bcl2, and Bax were ascertained. Loading control was established using β-actin. The three separate experiments' mean ± SEM (n = 3) is represented by the data. (*** indicates p < 0.001, and ** indicates p < 0.005).

Figure 5.

MAE promotes intercellular aggregation, and E-cadherin levels in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. After incubating MDA-MB-231 cells with either 100 or 200 µg/mL of MAE or a vehicle-containing control, the cells were tested for cell aggregation. The cells were photographed at a magnification of 4× after 4 hours, and the percentage of cell-cell aggregates was calculated as mentioned in the Materials and Methods section. Western blotting was used to analyze the protein levels of E-cadherin, using β-actin as a loading control where MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL) or a vehicle-containing control was applied to MDA-MB-231 cells for 24 hours. The three separate experiments' mean ± SEM (n = 3) is represented by the data (p* < 0.05, p **< 0.005).

Figure 5.

MAE promotes intercellular aggregation, and E-cadherin levels in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. After incubating MDA-MB-231 cells with either 100 or 200 µg/mL of MAE or a vehicle-containing control, the cells were tested for cell aggregation. The cells were photographed at a magnification of 4× after 4 hours, and the percentage of cell-cell aggregates was calculated as mentioned in the Materials and Methods section. Western blotting was used to analyze the protein levels of E-cadherin, using β-actin as a loading control where MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL) or a vehicle-containing control was applied to MDA-MB-231 cells for 24 hours. The three separate experiments' mean ± SEM (n = 3) is represented by the data (p* < 0.05, p **< 0.005).

Figure 6.

The ethanolic extract of Mandragora autumnalis inhibits the adherence of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells to collagen and lowers the levels of the protein integrin β1. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured for 24 hours with either MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL) or a vehicle-containing control. After that, cells were seeded into wells coated with collagen and given three hours to adhere. The MTT assay was used to measure adhesion, and the results were reported as a percentage of the corresponding control cells. (B) For 24 hours, MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured with either vehicle-containing control or MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL). β-actin served as a loading control when integrin β1 expression levels in whole-cell protein lysates were examined by Western blotting. The data show the average ± standard error of three separate experiments (n = 3), (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005, **** p < 0.0001).

Figure 6.

The ethanolic extract of Mandragora autumnalis inhibits the adherence of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells to collagen and lowers the levels of the protein integrin β1. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured for 24 hours with either MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL) or a vehicle-containing control. After that, cells were seeded into wells coated with collagen and given three hours to adhere. The MTT assay was used to measure adhesion, and the results were reported as a percentage of the corresponding control cells. (B) For 24 hours, MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured with either vehicle-containing control or MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL). β-actin served as a loading control when integrin β1 expression levels in whole-cell protein lysates were examined by Western blotting. The data show the average ± standard error of three separate experiments (n = 3), (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005, **** p < 0.0001).

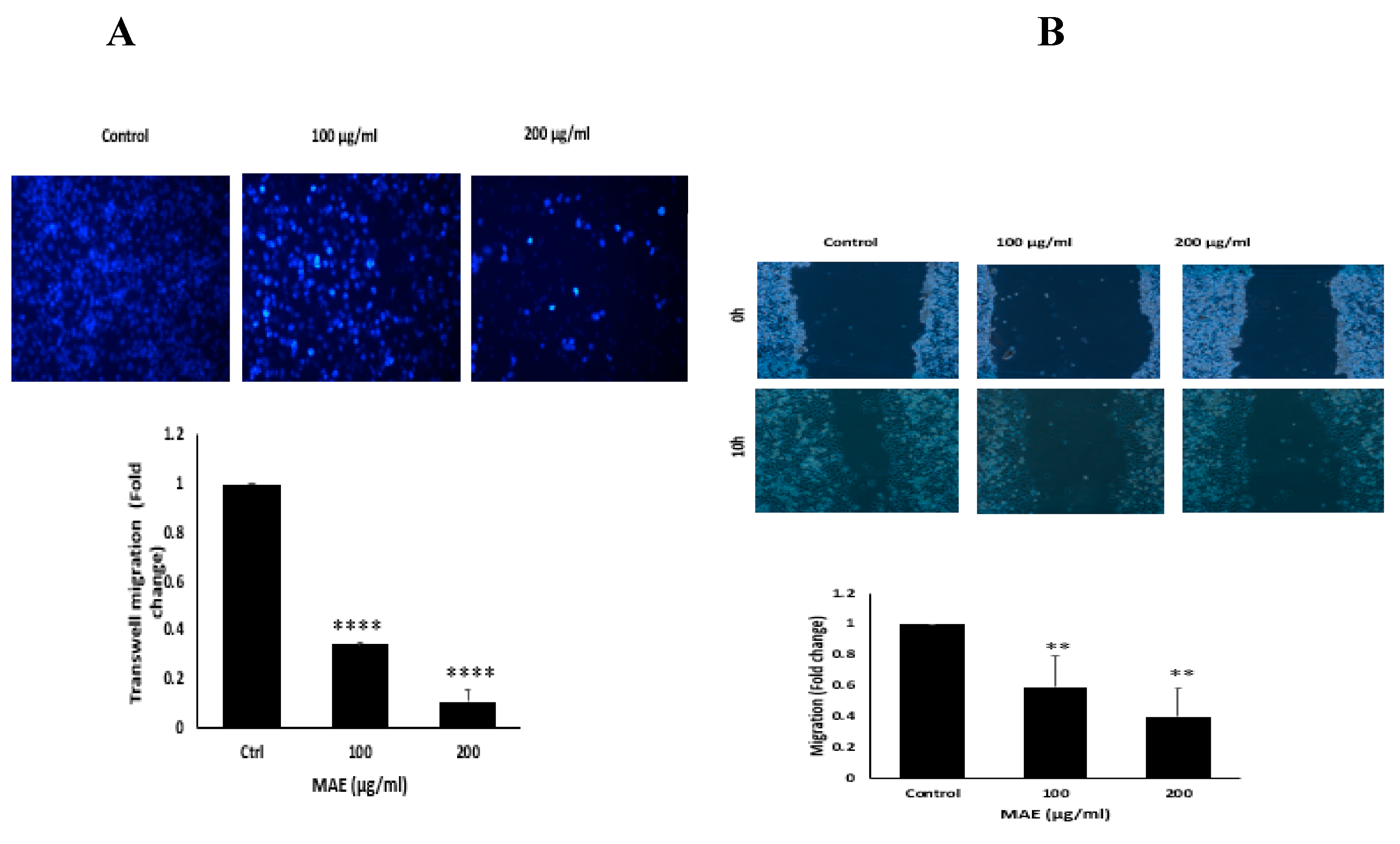

Figure 7.

Using an inverted phase-contrast microscope at the designated time points and 4× magnification, photomicrographs of the wound were taken. Plotted values represent the fold change in migration relative to control cells treated with a vehicle. (B) In Boyden chamber trans-well inserts, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated overnight with either MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL) or a vehicle-containing control. After migrating to the chamber's lower surface, the cells were counted, examined, photographed at a 4x magnification, and stained with DAPI. The data show the average ± standard error of three separate experiments (n = 3). (** p < 0.005, **** p < 0.0001).

Figure 7.

Using an inverted phase-contrast microscope at the designated time points and 4× magnification, photomicrographs of the wound were taken. Plotted values represent the fold change in migration relative to control cells treated with a vehicle. (B) In Boyden chamber trans-well inserts, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated overnight with either MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL) or a vehicle-containing control. After migrating to the chamber's lower surface, the cells were counted, examined, photographed at a 4x magnification, and stained with DAPI. The data show the average ± standard error of three separate experiments (n = 3). (** p < 0.005, **** p < 0.0001).

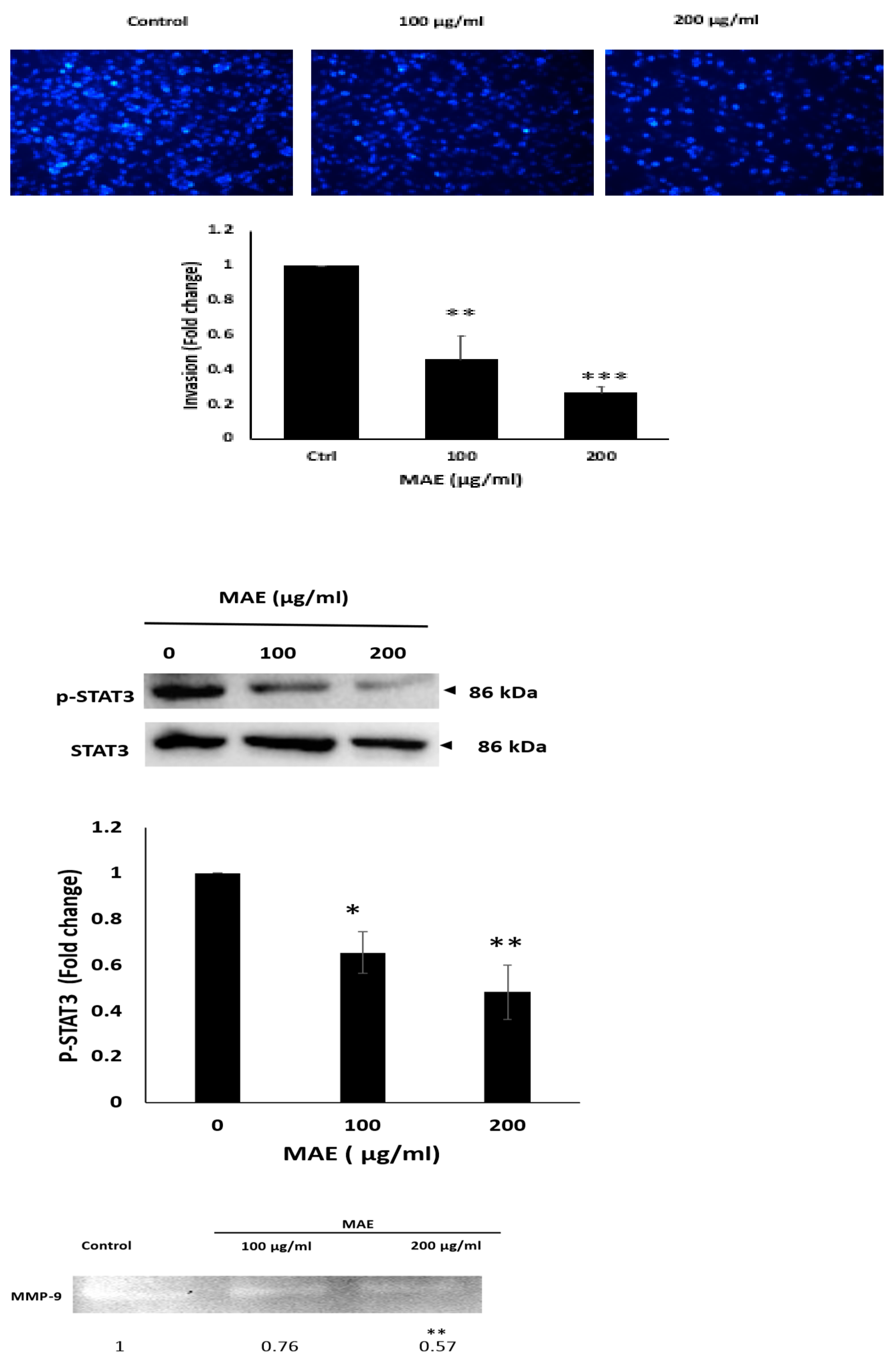

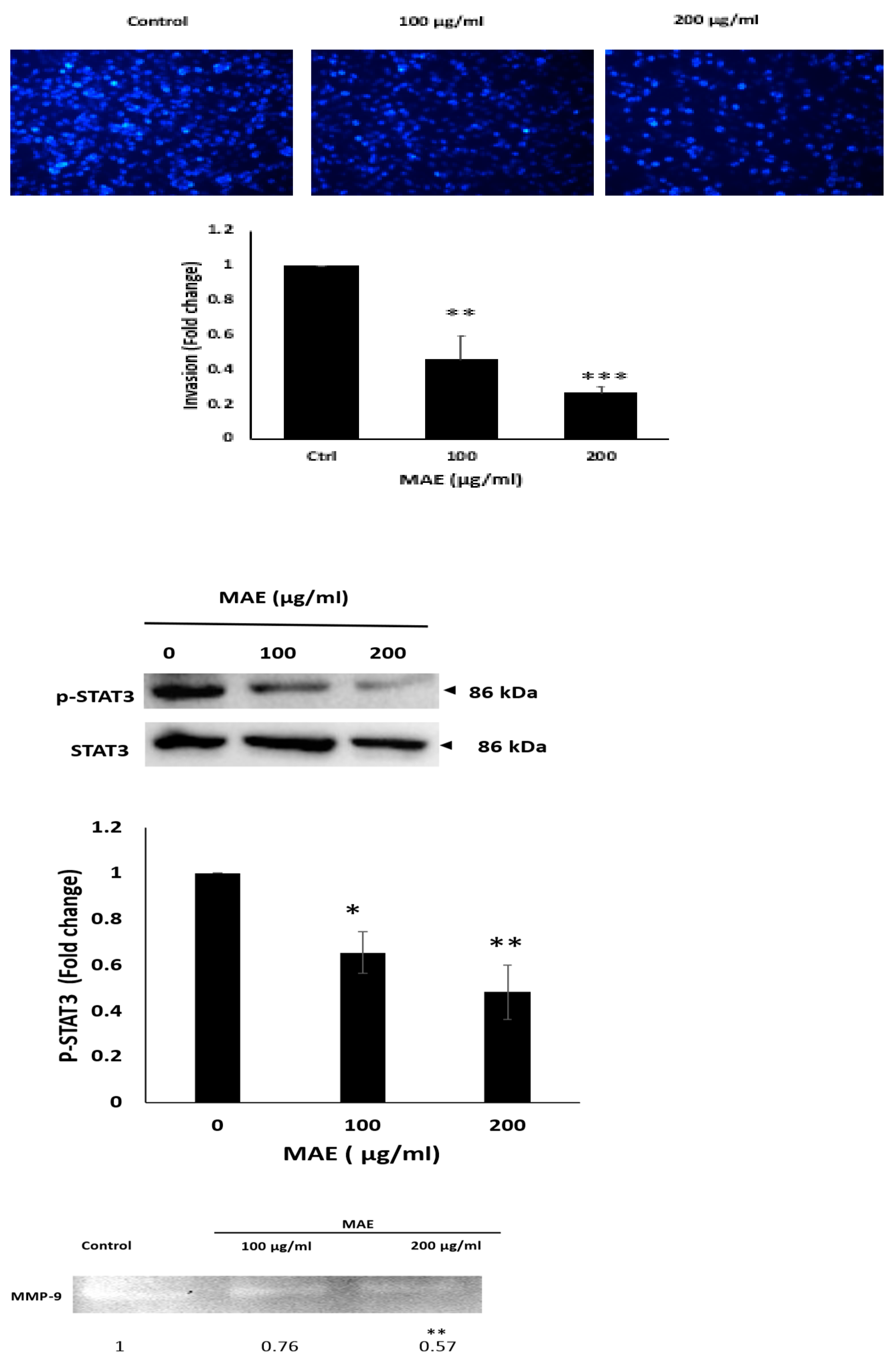

Figure 8.

The invasive potential of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells is decreased by MAE extract. For 24 hours, MDA cells were cultured in Boyden chamber trans-well inserts that had been previously coated with Matrigel, either with a vehicle-containing control or with 100 or 200 µg/mL of MAE. The Matrigel layer's invading cells were imaged, counted, and examined using DAPI staining. Images were captured with a 4x magnification. The three separate experiments' mean ± SEM (n = 3) is represented by the data. (**p < 0.005 and *** p < 0.001).Western blotting was used to measure the phosphorylated STAT3 protein levels, with β-actin serving as a loading control. Cells were treated either with a vehicle-containing control or with MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL). The results showe that the the STAT3 signaling pathway is inhibited by MAE extract. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n = 3), (*p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.005). After being seeded in serum-free media, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 100 or 200 µg/mL of MAE. Then the conditioned media were concentrated and put through gelatin zymography to determine MMP-9 activity (**p<0.01 and *** p <0.001).

Figure 8.

The invasive potential of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells is decreased by MAE extract. For 24 hours, MDA cells were cultured in Boyden chamber trans-well inserts that had been previously coated with Matrigel, either with a vehicle-containing control or with 100 or 200 µg/mL of MAE. The Matrigel layer's invading cells were imaged, counted, and examined using DAPI staining. Images were captured with a 4x magnification. The three separate experiments' mean ± SEM (n = 3) is represented by the data. (**p < 0.005 and *** p < 0.001).Western blotting was used to measure the phosphorylated STAT3 protein levels, with β-actin serving as a loading control. Cells were treated either with a vehicle-containing control or with MAE (100 or 200 µg/mL). The results showe that the the STAT3 signaling pathway is inhibited by MAE extract. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n = 3), (*p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.005). After being seeded in serum-free media, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 100 or 200 µg/mL of MAE. Then the conditioned media were concentrated and put through gelatin zymography to determine MMP-9 activity (**p<0.01 and *** p <0.001).

Figure 9.

The G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in MDA-MB-231 cells is induced by MAE. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured for 24 hours with 200 µg/mL of MAE or a vehicle-containing control. Following collection and fixation, cells were stained with 4′, 6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. The mean ± SEM of three separate experiments (n = 3) is represented by the data. (B) MAE (200 µg/mL) or a vehicle-containing control was used to treat the cells. Western blotting was used to measure the amounts of phosphorylated p38, p21, p27, Rb, and phosphorylated p53 proteins. To control loading, β-actin was employed. The mean ± SEM of three separate experiments (n = 3) is represented by the data. ** indicates p < 0.005, and * indicates p < 0.05.

Figure 9.

The G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in MDA-MB-231 cells is induced by MAE. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured for 24 hours with 200 µg/mL of MAE or a vehicle-containing control. Following collection and fixation, cells were stained with 4′, 6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. The mean ± SEM of three separate experiments (n = 3) is represented by the data. (B) MAE (200 µg/mL) or a vehicle-containing control was used to treat the cells. Western blotting was used to measure the amounts of phosphorylated p38, p21, p27, Rb, and phosphorylated p53 proteins. To control loading, β-actin was employed. The mean ± SEM of three separate experiments (n = 3) is represented by the data. ** indicates p < 0.005, and * indicates p < 0.05.

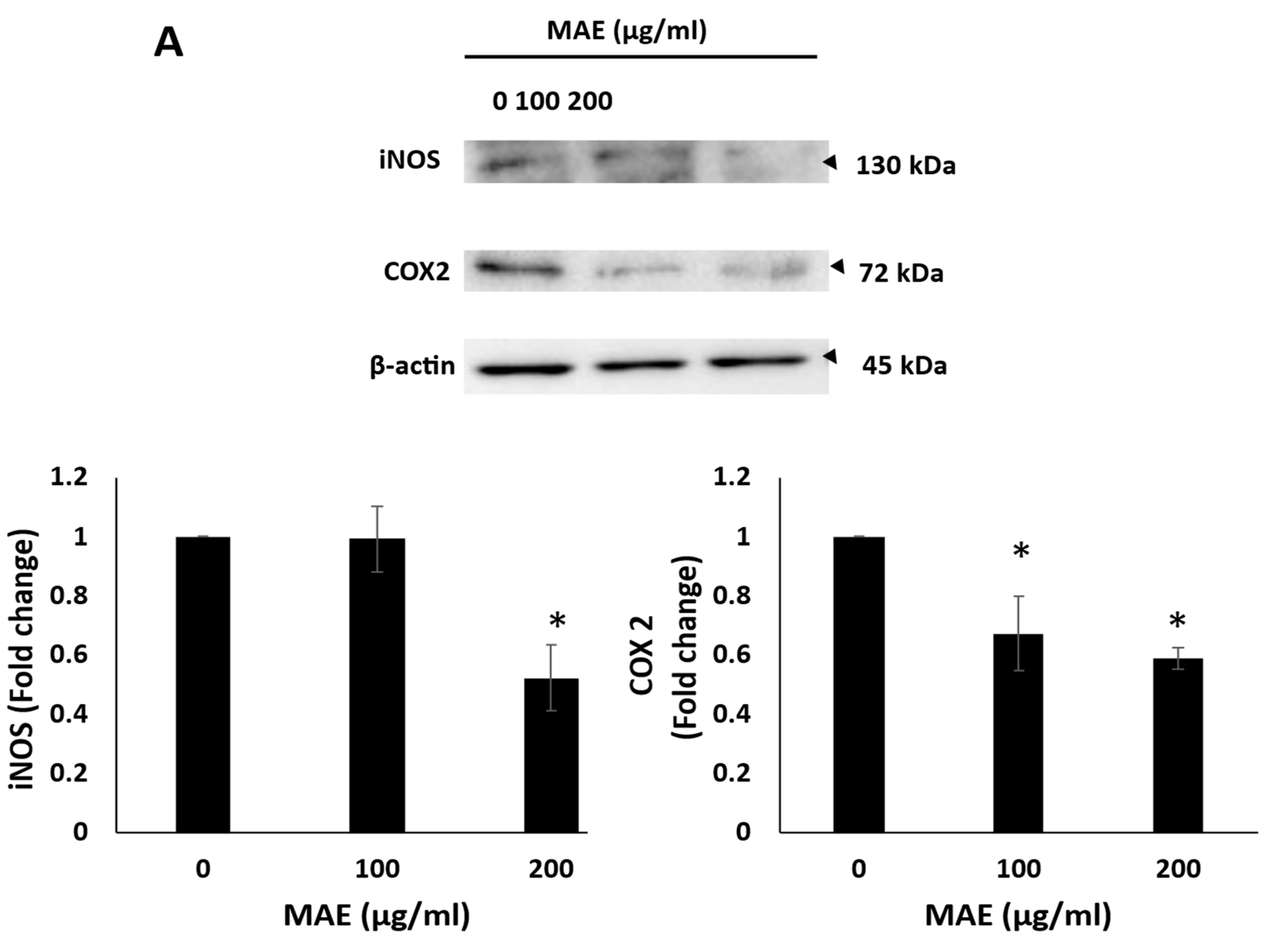

Figure 10.

MAE extract lowers the amounts of iNOS and COX-2 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and suppresses angiogenesis in fertilized chicken eggs. (A) MAE lowers the amounts of iNOS and COX-2 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and prevents angiogenesis in fertilized chicken eggs. (B) For 24 hours, MAE was applied to the fertilized chicken eggs' chorioallantoic membrane (CAM). Pictures were taken 24 hours before the fertilized chicken eggs' chorioallantoic membrane (CAM). To score the angiogenic response, pictures were taken both before and after treatment. AngiTool 0.5a software was used to measure the total length of the vessel and the total number of junctions. . Western blotting was used to measure the protein levels of COX-2 and iNOS, with β-actin serving as a loading control. The results were displayed as the percentage change compared to the vehicle-treated control.. The mean ± SEM of three separate experiments (n = 3) is represented by the data. ** p<0.005, *** p<0.001, * p<0.05).

Figure 10.

MAE extract lowers the amounts of iNOS and COX-2 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and suppresses angiogenesis in fertilized chicken eggs. (A) MAE lowers the amounts of iNOS and COX-2 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and prevents angiogenesis in fertilized chicken eggs. (B) For 24 hours, MAE was applied to the fertilized chicken eggs' chorioallantoic membrane (CAM). Pictures were taken 24 hours before the fertilized chicken eggs' chorioallantoic membrane (CAM). To score the angiogenic response, pictures were taken both before and after treatment. AngiTool 0.5a software was used to measure the total length of the vessel and the total number of junctions. . Western blotting was used to measure the protein levels of COX-2 and iNOS, with β-actin serving as a loading control. The results were displayed as the percentage change compared to the vehicle-treated control.. The mean ± SEM of three separate experiments (n = 3) is represented by the data. ** p<0.005, *** p<0.001, * p<0.05).

Table 1.

Qualitative Phytochemical analysis of Mandragora autumnalis ethanolic extract (MAE), (+) indicates the presence and (-) indicates the absence of the secondary metabolite.

Table 1.

Qualitative Phytochemical analysis of Mandragora autumnalis ethanolic extract (MAE), (+) indicates the presence and (-) indicates the absence of the secondary metabolite.

| Metabolite |

MAE |

| Anthraquinones |

- |

| Tannins |

+ |

| Resins |

- |

| Terpenoids |

+ |

| Flavonoids |

+ |

| Quinones |

- |

| Anthocyanins |

- |

| Saponins |

- |

| Phenols |

+ |

| Steroids |

+ |

| Cardiac glycosides |

- |

| Fixed oils and fatty acids |

+ |

Table 2.

TPC and TFC of Mandragora autumnalis ethanolic extract.

Table 2.

TPC and TFC of Mandragora autumnalis ethanolic extract.

| Assay Type |

MAE |

| TPC (mg GAE/g) |

58.98± 7.40 |

| TFC (mg QE/g) |

36.47± 0.87 |

Table 3.

Identified compounds in the ethanolic extract of Mandrgaora autumnalis using both (A) positive and (B) negative ionization modes in LC-MS.

Table 3.

Identified compounds in the ethanolic extract of Mandrgaora autumnalis using both (A) positive and (B) negative ionization modes in LC-MS.

|

| Number |

m/z |

RT [min] |

Ions |

Compound Name |

Molecular Formula |

Intensity |

| 1 |

127.0389 |

0.58 |

[M+H]+ |

5-Hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxaldehyde |

C6H6O3

|

49130.136 |

| 2 |

133.0827 |

0.71 |

[M+H]+ |

Ethyl 3-hydroxy-butanoate |

C6H12O3

|

72955.974 |

| 3 |

140.1066 |

0.86 |

[M+H]+ |

Tropinone |

C8H13NO |

21053.859 |

| 4 |

149.0596 |

1.23 |

[M+H]+ |

3-(Methylthio)propyl acetate |

C6H12O2S |

8790.512 |

| 5 |

117.0542 |

1.3 |

[M+H]+ |

1-Hydroxy-2-propanone acetate |

C5H8O3

|

8646.324 |

| 6 |

193.0492 |

2.91

|

[M+H-C6H10O5]+ |

Chlorogenic acid |

C16H18O9

|

669015.883 |

| 355.1018 |

[M+H]+ |

221652.966 |

| 445.0708 |

[M+Na+NaCOOH]+ |

20681.809 |

| 7 |

619.2479 |

2.91 |

[M+H]+ |

Simulanoquinoline |

C37H34N2O7

|

11326.110 |

| 8 |

641.2302 |

[M+Na]+ |

90245.22 |

| 9 |

290.1745 |

3.89 |

[M+H]+ |

Hyoscyamine |

C17H23NO3

|

5938808.003 |

| 10 |

303.0494 |

9.16 |

[M+H]+ |

Quercetin |

C15H10O7

|

20868.344 |

| 11 |

179.1178 |

9.6 |

[M+H]+ |

Ethyl hydrocinnamate |

C11H14O2

|

24858.923 |

| 12 |

255.0862 |

13.43 |

[M+H]+ |

Chrysin |

C15H10O4

|

11043.2 |

| 13 |

281.266 |

26.76 |

[M+H]+ |

Linoleic acid |

C18H32O2

|

70427.883 |

| 14 |

311.2933 |

27.7 |

[M+H]+ |

Ethyl oleate |

C20H38O2

|

4151.762 |

| 15 |

243.2505 |

28.62 |

[M+H]+ |

n-Pentadecanoic acid |

C15H30O2

|

13652.643 |

| 16 |

193.1581 |

29.04 |

[M+H]+ |

Ionone (β-Ionone) |

C13H20O |

10667.398 |

| 17 |

307.266 |

29.32 |

[M+H]+ |

Ethyl linolenate |

C20H34O2

|

10224.308 |

| 18 |

156.138 |

29.41 |

[M+H]+ |

Methylisopelletierine |

C9H17NO |

48479.510 |

| 19 |

114.0911 |

29.41 |

[M+H-C2H4]+ |

Tropine |

C8H15NO |

42742.76 |

| 142.1224 |

[M+H]+ |

57239.581 |

| 20 |

336.2868 |

29.49 |

[M+Na]+ |

Solacaproine |

C18H39N3O |

8765.329 |

| 21 |

256.2629 |

29.51 |

[M+H]+ |

Hexadecanamide (Palmitic amide) |

C16H33NO |

7806388.659 |

| 278.2449 |

[M+Na]+ |

1763628.958 |

| 511.5185 |

29.52 |

[2M+H]+ |

449241.592 |

| 533.5006 |

[2M+Na]+ |

363277.043 |

| 294.2182 |

[M+K]+ |

35062.909 |

| 22 |

297.2893 |

[M+H-NH3]+ |

Solacaproine |

C18H39N3O |

86740.906 |

| 314.3049 |

[M+H]+ |

52611.286 |

| 23 |

285.2879 |

29.77 |

[M+H]+ |

Ethyl palmitate |

C18H36O2

|

58073.530 |

|

| 24 |

111.0088 |

0.75 |

[M-H]- |

3-Methyl-2-5-furandione |

C5H4O3

|

100.285 |

| 25 |

117.01932 |

0.83 |

[M-H]- |

Succinic acid |

C4H6O4

|

12012 |

| 26 |

353.08783 |

2.21 |

[M-H]- |

Chlorogenic acid |

C16H18O9

|

258912 |

| 27 |

207.050913 |

3.29 |

[M-H]- |

4-O-Methylglucuronic acid |

C7H12O7

|

4598.659 |

| 28 |

131.07127 |

3.33 |

[M-H]- |

Ethyl 3-hydroxy-butanoate |

C6H12O3

|

2582 |

| 29 |

179.03492 |

3.86 |

[M-H]- |

Caffeic Acid |

C9H8O4

|

5934 |

| 30 |

175.04000 |

4.23 |

[M-H-COCH2]- |

4-Methylumbelliferyl acetate |

C12H10O4

|

27106.992 |

| 217.05106 |

[M-H]- |

4492.950 |

| 31 |

176.01133 |

6.56 |

[M-H-CH3]- |

Scopoletin |

C10H8O4

|

26388.932 |

| 191.03486 |

[M-H]- |

43250.386 |

| 259.02198 |

[M-H+NaCOOH]- |

9135.296 |

| 32 |

609.1457 |

9.19 |

[M-H]- |

Rutin |

C27H30O16

|

25850 |

| 33 |

463.08799 |

10.39 |

[M-H]- |

Hyperoside |

C21H20O12

|

18198 |

| 34 |

277.21675 |

29.84 |

[M-H]- |

Linolenic acid |

C18H30O2

|

51774.794 |

| 345.20465 |

[M-H+NaCOOH]- |

4077.093 |

Table 4.

The proposed mechanism of action of MAE in the treatment of TNBC through mediation of the selected markers.

Table 4.

The proposed mechanism of action of MAE in the treatment of TNBC through mediation of the selected markers.

| Marker |

Change |

Proposed Role of MAE in TNBC Treatment |

| Ki-67 |

↓ Decrease |

Reduced cell proliferation indicates an antiproliferative treatment effect. |

| Procaspase-3 |

↓ Decrease |

Suggests activation of caspase-3; promotes apoptosis. |

| Bcl-2 |

↓ Decrease |

Loss of anti-apoptotic protection favors apoptosis. |

| Caspase-3 |

↑ Increase |

Active executioner of apoptosis; confirms pro-apoptotic effect |

| BaX |

↑ Increase |

promotes mitochondrial apoptosis pathway |

| E-cadherin |

↑ Increase |

Enhances cell–cell adhesion; suppresses EMT and metastasis |

| Integrin β1 |

↓ Decrease |

Reduces cell migration and invasion; anti-metastatic effect |

| p-STAT3 |

↓ Decrease |

Reduces invasion, EMT, and survival signaling; enhances chemosensitivity. |

| MMP-9 |

↓ Decrease |

Less ECM degradation; limits invasion and metastasis |

| p21 |

↑ Increase |

CDK inhibitor; induces cell cycle arrest (G1 phase). |

| p27 |

↑ Increase |

CDK inhibitor; halts cell cycle progression; anti-proliferative |

| p-p38 |

↑ Increase |

Stress-activated kinase; can enhance apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. |

| p-p53 |

↑ Increase |

Activated tumor suppressor; promotes DNA repair or apoptosis |

| iNOS |

↓ Decrease |

May reduce nitric oxide-induced tumor progression and inflammation |

| p-Rb |

↓ Decrease |

May reflect enhanced apoptosis or cell cycle deregulation |

| COX-2 |

↓ Decrease |

Reduces inflammation and tumor-promoting prostaglandins; anti-tumor effect |