Introduction

Each year, mosquitoes wage a silent yet devastating war—infecting nearly 700 million people and claiming more than a million lives across the globe [

1]. Mosquito-borne viruses like dengue, chikungunya, and Zika have devastated 166 countries over the last five decades, costing nearly

$100 billion and surging fourteen-fold between 2013 and 2022 [

2]. While malaria continues to devastate Africa—accounting for over 90% of cases reported in the WHO African Region [

3]—Asia is grappling with dengue, which is responsible for nearly 70% of global infections [

4], with Southeast Asia bearing the heaviest burden [

5]. Although the COVID-19 pandemic momentarily disrupted this trajectory, the post-pandemic resurgence of dengue infections reveals its persistent grip on the region [

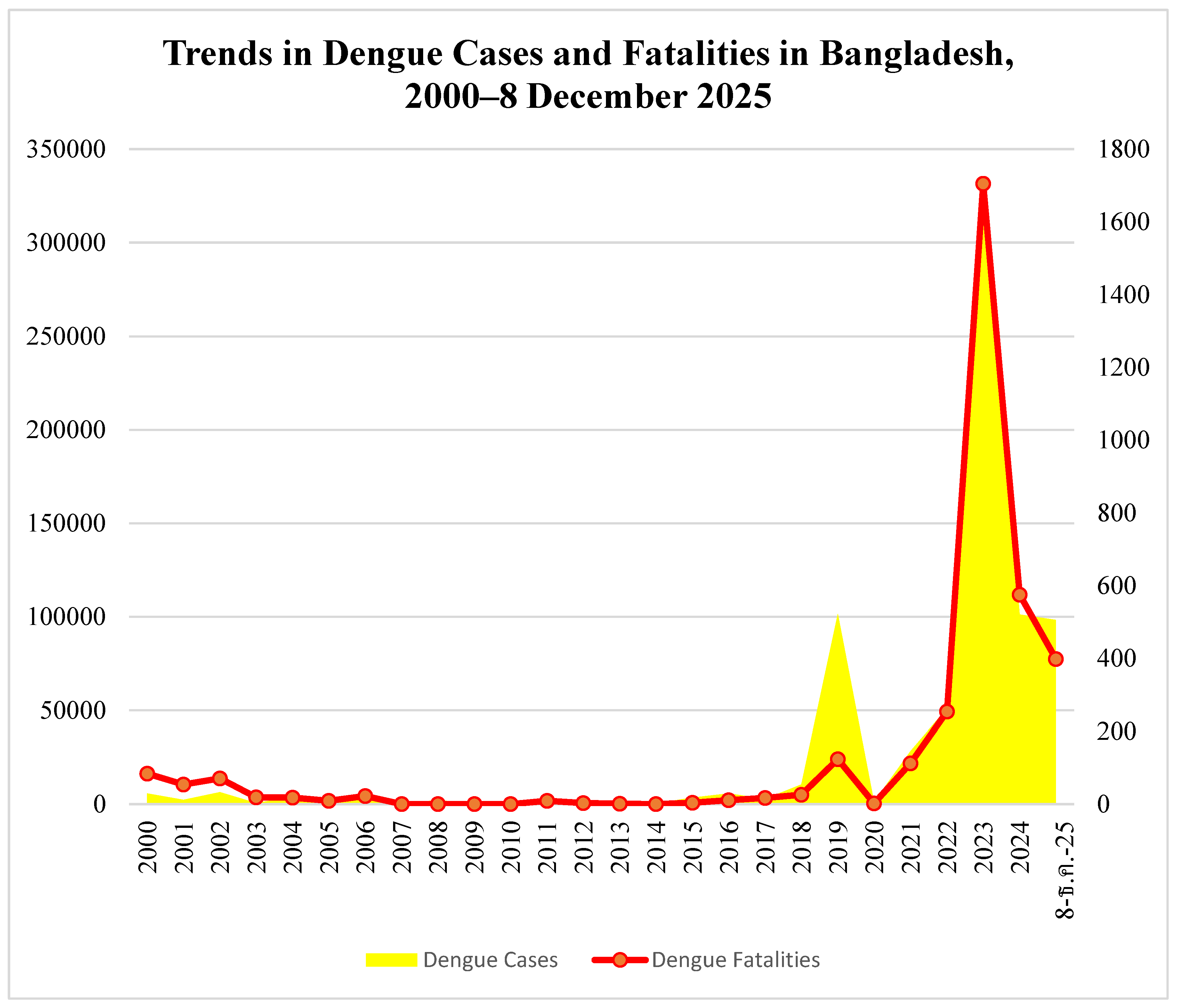

6]. In Bangladesh, dengue remained relatively rare before 2018 but surged thereafter, following global trends, briefly paused during the COVID-19 pandemic, and emerged as the deadliest infectious disease in the post-COVID era, peaking in 2023 (

Figure 1). This alarming rise, driven by a combination of meteorological changes and overlooked socioeconomic factors, forms the central focus of this paper.

Methodology

This review synthesizes evidence from leading global health datasets, peer-reviewed literature, major international reports, and national sources including the DGHS, IEDCR, and the Bangladesh Meteorological Department to assess recent trends in dengue transmission in Bangladesh. When contemporary scholarly data were unavailable or incomplete, rigorously verified reports from reputable news media were incorporated to provide timely contextual updates. Environmental and socioeconomic determinants of dengue transmission were systematically integrated with key climatic variables—temperature, humidity, and rainfall—to construct a multidimensional understanding of transmission dynamics. Given the rapidly evolving nature of dengue epidemiology in Bangladesh, the analysis also employed cautiously framed predictive inferences informed by both local and global research. This approach enabled the identification of several under-recognized drivers of dengue virus transmission that may influence future outbreak patterns.

Literature Review

The Current Global Landscape of Dengue

Global dengue incidence is rising at an alarming rate. While reported patterns vary, the surge is undeniable. According to WHO, 6.5 million cases and 8,791 deaths were reported globally in 2023 [

7], rising to 7.6 million cases and 3,000 deaths by April 2024 [

8]. Notably, the US CDC and WHO’s global dengue surveillance system, launched in May 2024, reported 12–13 million cases and over 7,000 deaths in the Americas alone in 2024 [

9,

10]. Ranked among WHO’s top ten global health threats, dengue affected approximately 90 countries in 2024, with Brazil bearing the highest burden, followed by Argentina and Mexico [

11]. Current WHO estimates suggest that dengue causes up to 400 million infections annually [

12], with incidence having increased thirtyfold over the past fifty years [

13], now placing 3.9–5.6 billion people—more than half of the world’s population—at risk [

14,

15]. Moreover, the US CDC reports that half of the global population lives in dengue-risk areas, putting both residents and travelers at risk [

16]. Dengue, primarily transmitted by

Aedes aegypti and

Aedes albopictus, disproportionately affects the southern hemisphere, making effective tetravalent vaccines critical for global health [

17]. Current vaccine development faces challenges in ensuring protection against all serotypes, addressing varied immune responses, and adapting to emerging strains.

Meteorological and Socioeconomic factors of Dengue Transmission

Environmental and socioeconomic factors jointly drive global dengue transmission, with climate conditions like temperature, rainfall, and humidity shaping mosquito habitats, while urbanization, population density, poverty, and inadequate sanitation increase human exposure and vulnerability, as discussed in

Table 1.

Key Risk Factors for Dengue in Bangladesh: Insights from Previous Research

Bangladesh, a tropical country in South Asia situated between 20°–27°N and 88°–93°E, occupies the world’s largest and most densely populated delta—the low-lying Ganges–Brahmaputra Delta, formed by rivers originating in the Himalayas. With more than 1,000 rivers spanning roughly 24,140 km and a coastline along the Bay of Bengal, the nation experiences high humidity and heavy rainfall, making it particularly vulnerable to floods and tropical cyclones [

27,

28,

29]. Over the past four decades, temperatures in Bangladesh have risen by approximately 0.5 °C, which has lengthened the dengue season and accelerated transmission, with case numbers doubling roughly every decade since 1990. The World Bank notes that dengue infections increase significantly at temperatures between 25 °C and 35 °C, peaking around 32 °C, while global mosquito transmission capacity has grown by up to 9.5% since 1950 [

30].

A study published in Oxford Academic on dengue transmission in Bangladesh (2000–2022) found that rising temperatures and shifts in rainfall patterns between 2011 and 2022 were closely linked to increased cases and deaths [

31]. Recent climatic shifts have further intensified the risk. From 2022 to 2025, October rainfall in Bangladesh has been highly variable, with a trend toward heavier late-monsoon precipitation. Such changes have prompted entomologists to warn of prolonged dengue outbreaks [

32,

33,

34]. A comprehensive review of three major medical databases—PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science—up to December 5, 2024, indicates that climate change is reshaping temperature, rainfall, and humidity patterns, thereby expanding the geographic range of dengue and altering exposure risks across different populations [

35].

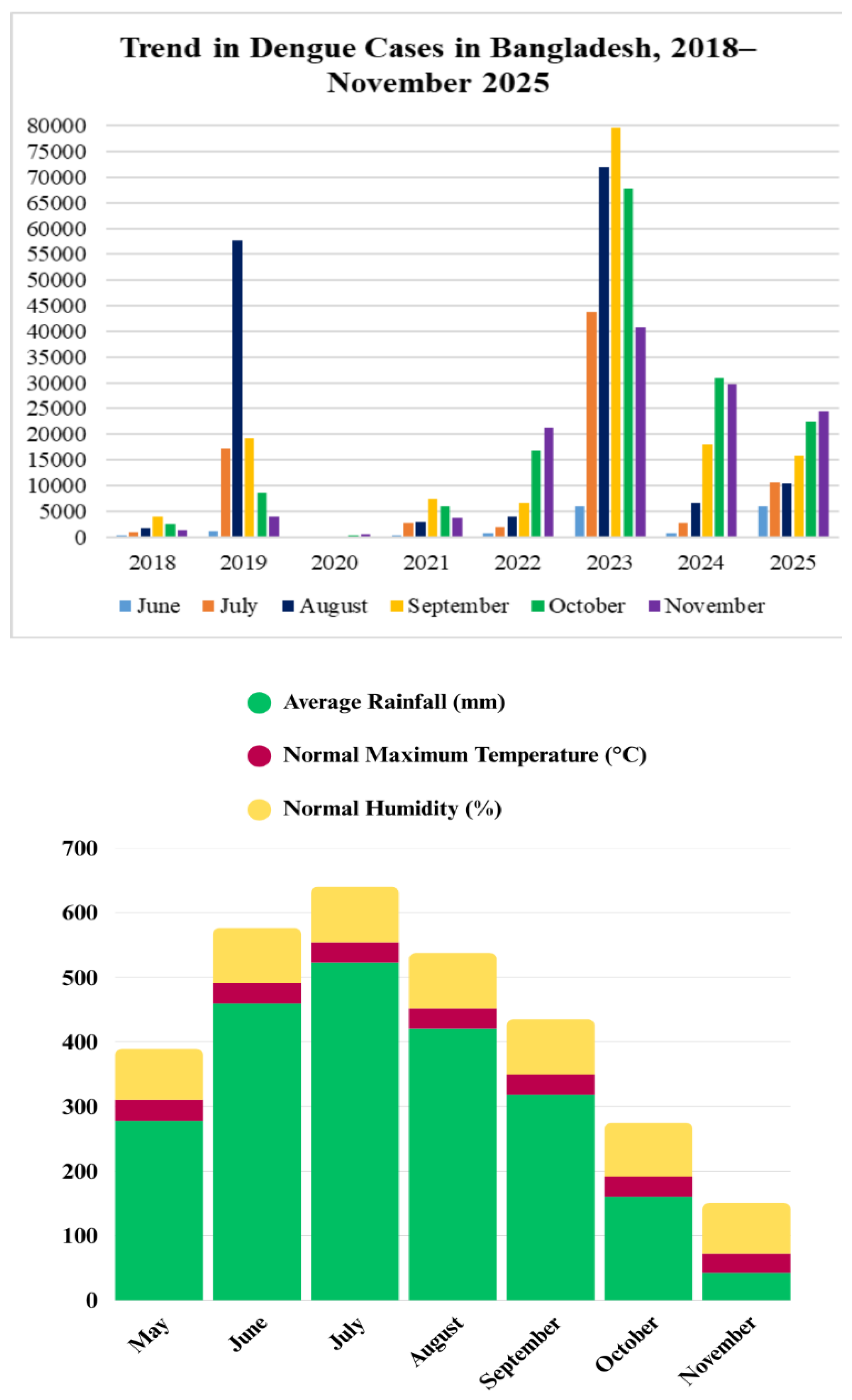

Figure 2 shows that, following the global pattern, dengue cases rise in tandem with increases in temperature, rainfall, and humidity.

Evaluating the various dengue determinants in Bangladesh from 2000 to 2023, researchers from Begum Rokeya University used XGBoost and LightGBM with explainable AI to identify population density, precipitation, temperature, and land-use as key predictors, aligning with recent studies and supporting early-warning systems [

36]. A comparative analysis with Singapore found that rainfall fueled dengue transmission in Bangladesh while humidity and sunshine suppressed it—whereas in Singapore, warmer temperatures drove infections and rainfall and humidity helped curb spread [

37]. Hossain et al. (2023) identified rapid urbanization, climatic suitability, and the persistent presence of

Aedes mosquitoes as key drivers of increased human–vector contact and the expanding geographic reach of dengue. Periodic serotype shifts, weak surveillance, limited healthcare capacity, and low public awareness further intensify these risks [

38]. Building on this, Khan et al. (2024) highlighted possible post-COVID immune effects, climate variability, dominant viral serotypes, and systemic failures in patient management as contributors to Bangladesh’s recent high fatality rates, underscoring the need for stronger clinical care, more trained personnel, improved vector control, and investment in One Health–based prevention [

39].

Examining seasonal dengue patterns from January 2008 to November 2024, Alam et al. (2025) showed that incidence is tightly linked to meteorological conditions, with peaks strongly correlated with higher temperatures, humidity, rainfall, and wind speed. Their study emphasized the need for future models to integrate real-time meteorological inputs along with urbanization and socioeconomic factors [

40]. Islam et al. (2023) similarly argued that combining climate projections with human mobility and socio-environmental variables is essential for forecasting outbreaks and guiding effective prevention strategies [

41]. Supporting this, Islam and Hu (2024) identified rapid human movement as a major transmission driver in Bangladesh, with festival gatherings, increased mobility, and post-lockdown shifts all associated with higher case burdens [

42]. Ogieuhi et al. (2025) noted that poor sanitation, insecticide resistance, limited vaccine access, low public awareness, and mounting healthcare pressures, combined with climate change and rapid urbanization, collectively heighten dengue risks, especially for vulnerable populations [

43].

Common Public Perception Vs Reality

In Bangladesh, dengue perception shows a mix of high awareness of its severity (it’s deadly) but low personal risk (susceptibility), leading to inconsistent prevention, with educated urban dwellers often better informed than rural populations.

Table 2 offers an overview of dengue-related knowledge, perception, and attitudes across different Bangladeshi populations.

The recent dengue outbreaks, driven by shifting climate patterns, rapid urbanization, dense populations, insecticide resistance, and low public awareness, have severely strained Bangladesh’s healthcare system and economy. While climate change strongly shapes dengue (

Flavivirus) transmission, insecticide misuse and rising resistance also play critical roles. WHO has warned that fogging is ineffective against

Aedes mosquitoes, underscoring city corporations’ misplaced reliance on mass spraying instead of source reduction, targeted larviciding, and proper vector control. Compounding the problem, widespread metabolic resistance and common kdr mutations have greatly reduced the effectiveness of pyrethroid insecticides, producing very low mosquito mortality even at elevated doses [

54,

55,

56].

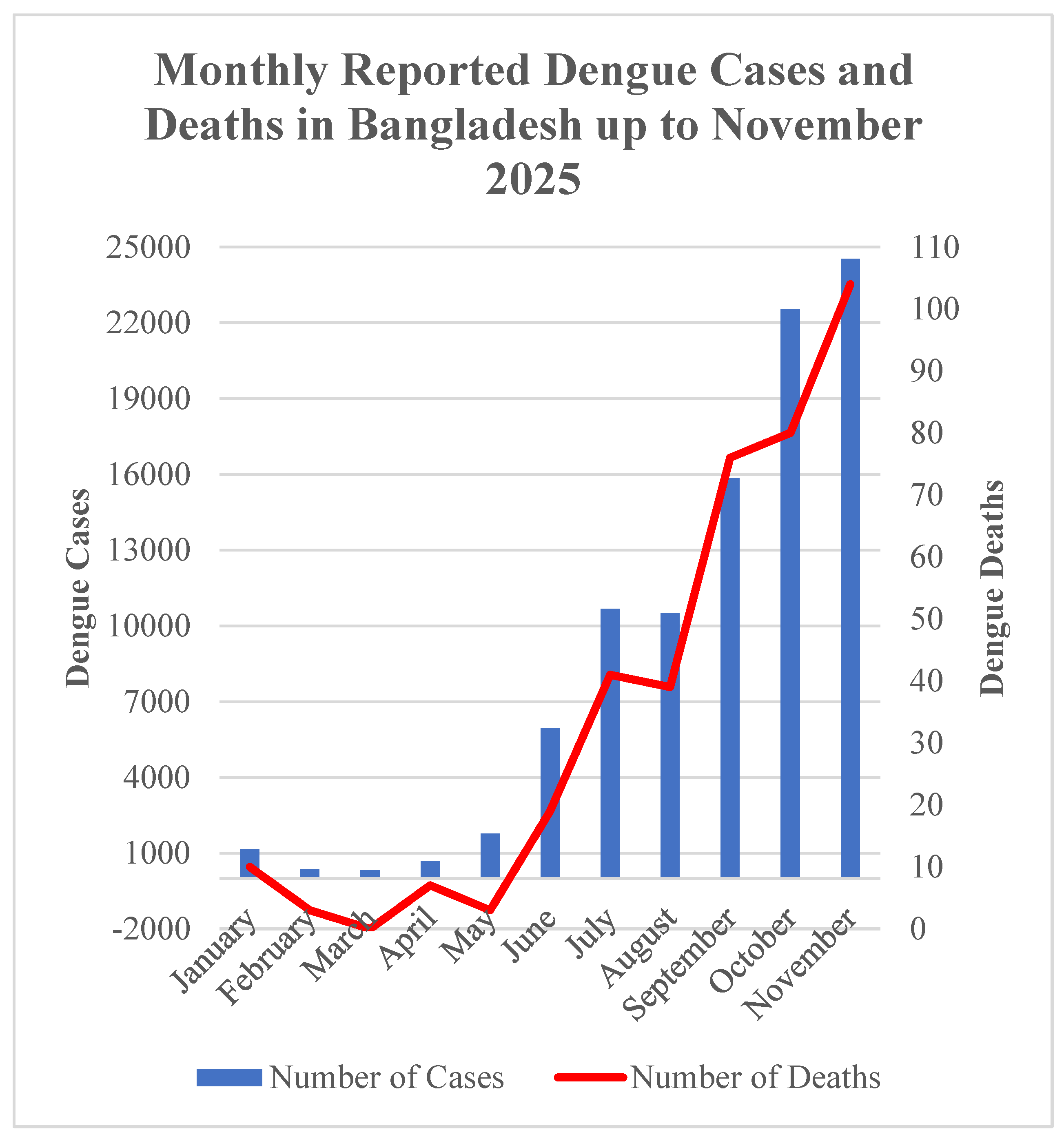

Rainfall influences mosquito growth in complex ways. While light rain creates standing water ideal for breeding, heavy rainfall can destroy breeding sites or wash away larvae, limiting mosquito development. Additionally, wind speed was found to be weakly positively correlated with dengue incidence in Bangladesh. Although many attributed the 2025 outbreak to heavy rainfall, the persistence of dengue had already been evident, with over 320,000 infections and 1,700 deaths recorded in 2023—figures considerably higher than those observed in 2025 (

Figure 3). Interestingly, a study conducted in Dhaka revealed that dengue cases actually declined with increasing levels of both rainfall and sunshine, contradicting common public perception [

57]. Experts warn that prolonged monsoons and poor waste management have created stagnant water and ecological imbalance, enabling mosquitoes to breed more extensively and intensifying the outbreaks [

58].

Discussion

Escalating Dengue Burden in Bangladesh

Bangladesh is at the epicenter of the crisis, grappling with unprecedented challenges. By 21 September 2025, deaths had surged 150% and cases had doubled from the previous year [

59], and just two months later, by 23 November, infections had topped 90,000 with fatalities reaching 364 [

60]—70% higher than six weeks earlier [

61]. Hospital admissions, according to dynamic data from the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) [

62], nearly quadrupled from 5,951 in June to 22,520 in October 2025, pushing an already fragile healthcare system to the brink (

Figure 3).

November 2025 brought the crisis to a new peak: on 18 November alone, over 900 viral fever patients flooded hospitals, joining nearly 3,000 dengue cases already under treatment [

63]. Since 2023, more than half a million Bangladeshis have been infected and over 2,670 have died—marking the deadliest dengue toll in the nation’s history. By the end of November, total cases had surpassed 94,300, hospitalizations had exceeded 92,000, and deaths had risen to 382. November alone recorded more than 24,500 cases and 104 fatalities, meaning that over one-quarter of the year’s infections and deaths occurred in a single, devastating month [

62].

Historical data magnify the crisis. Between 2000 and 2022, Bangladesh recorded 853 dengue-related deaths [

39,

64], yet 2023 alone more than doubled that total, with 1,705 fatalities and over 321,000 infections—the largest annual outbreak on record (

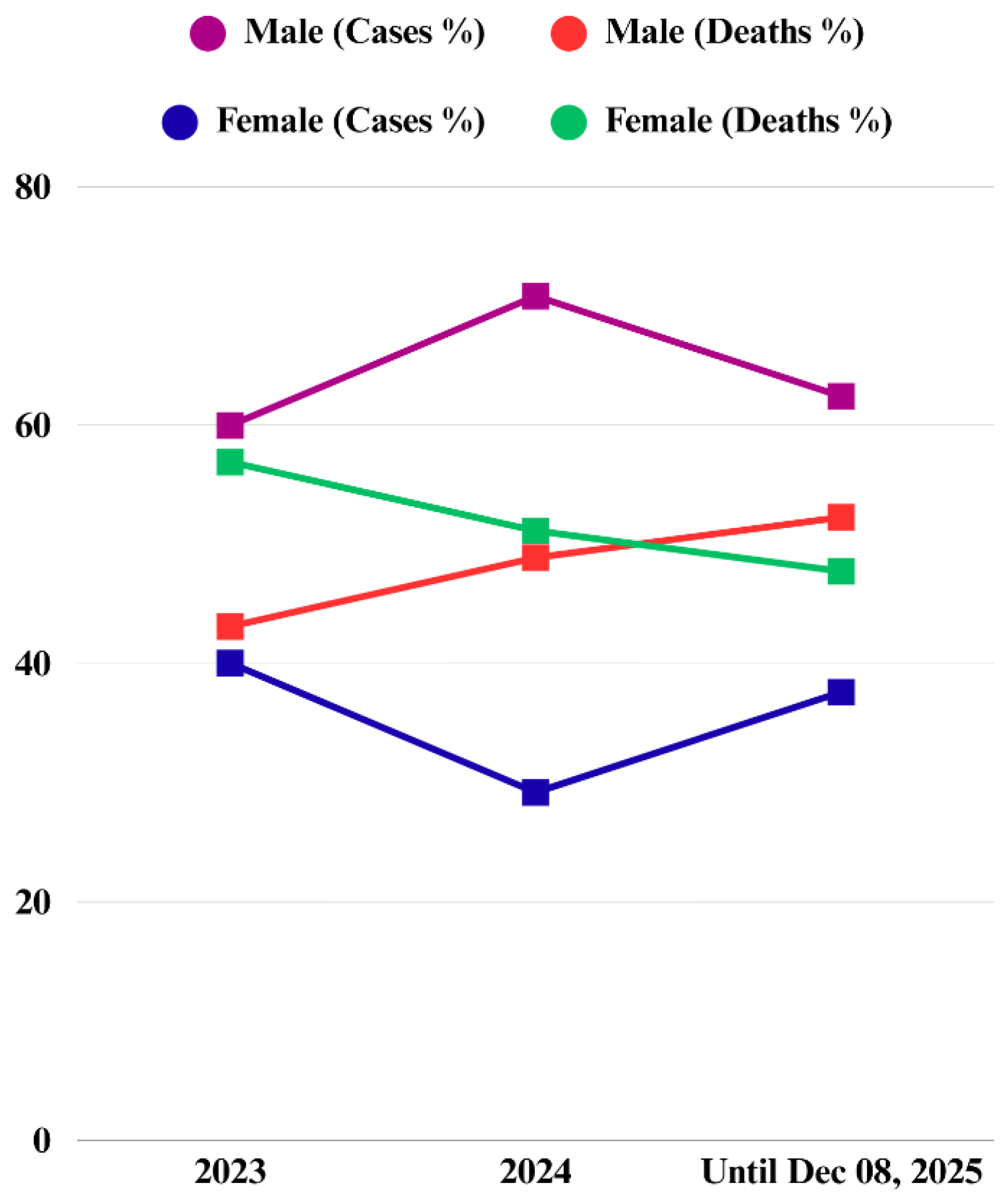

Figure 1). The demographic landscape is shifting. In 2023, women represented roughly 40% of dengue cases but accounted for 57% of deaths [

65]. By December 8, 2025, men experienced nearly twice as many cases and over half of all deaths (

Figure 4). Notably, in 2023, older adults faced disproportionately severe dengue and higher mortality due to immune vulnerability and comorbidities, with each additional decade raising fatality by 30%, whereas by 2025, young adults aged 21–30 accounted for over a quarter of both cases and deaths [

62,

65]. However, older adolescents and young adults also represented more than half of all cases during the 2016, 2018, and 2019 outbreaks [

65].

Results and Findings

The Overlooked Drivers of Bangladesh’s Escalating Dengue Crisis

The recent dengue outbreaks, fueled by changing climate patterns, rapid urbanization, high population density, insecticide resistance, and low public awareness, have placed a severe strain on Bangladesh’s healthcare system and economy. While climate change and urban growth are widely acknowledged as major drivers of the rising dengue burden, several less-discussed factors—often tied to uncontrolled urbanization—have intensified the crisis; these interconnected issues, highlighted in recent international research and media, remain largely overlooked by the public due to limited awareness.

Vegetation Loss, and Rising Temperature

Warmer temperatures accelerate mosquito aging, shortening their lifespan and altering infection patterns [

66]. Yet, over successive generations, heat-exposed mosquitoes can develop greater tolerance to viruses without losing vitality, a recent study shows [

67]. Global warming has thus become a “perfect storm” for mosquito-borne diseases, affecting every stage of transmission [

68].

Urbanization-driven loss of natural vegetation further elevates dengue risk, as areas with reduced green cover provide ideal conditions for mosquito breeding and disease spread, as demonstrated in studies from Mexico [

69] and Brazil [

70]. In Amazonian Brazil, for example, deforestation of just one square kilometer was linked to 27 additional malaria cases [

71].

Between 1989 and 2020, Dhaka lost more than half of its green cover due to rapid urban growth, triggering a significant rise in temperatures [

72]. Over three decades, the number of extreme heat days (≥35 °C) nearly doubled, making Dhaka one of the fastest-warming cities in the world, according to the International Institute for Environment and Development [

73]. Furthermore, the World Bank reports that the city’s heat index has increased more than 65% faster than the national average [

74]. These hotter, denser conditions let

Aedes mosquitoes adapt to heat, building stronger virus tolerance and becoming even more efficient carriers [

63]. A climate projection from a decade ago indicates that, without adaptation, a 3.3 °C increase by 2100 could result in more than 16,000 additional dengue cases [

75].

Population Density, Poor Sanitation, and Waste Disposal

Rapid urbanization and extreme population density in Bangladesh are creating ideal conditions for intensified dengue transmission. In overcrowded cities with inadequate sanitation, stagnant water accumulates easily, offering abundant breeding sites for

Aedes mosquitoes. Dhaka—home to more than 75,000 people per square mile [

76]—is now the world’s second most densely populated city [

77], and its tightly packed, human-built landscape accelerates

Aedes aegypti growth, reproduction, and survival far more than suburban or rural settings [

78]. Monsoon-season spikes in heat, humidity, and rainfall further amplify this risk, with 2019 data showing that nearly 90% of dengue cases erupted between June and October, overwhelmingly concentrated in the city’s hottest, most densely built neighborhoods [

79]. Dengue hotspots consistently emerge where population density is highest, particularly in Thanas such as Badda, Jatrabari, Kadamtali, Mirpur, Mohammadpur, Sobujbagh, Shyampur, Tejgaon, Dhanmondi, and Uttara, where close human–mosquito contact further amplifies transmission [

80].

In Bangladesh, roughly 40% of the population lives in urban areas, with over half residing in densely packed slums [

81]. Communities without adequate sanitation—especially in these overcrowded settlements—are highly vulnerable to mosquito-borne diseases such as dengue and chikungunya [

82]. Dhaka’s congested neighborhoods, compounded by poor sanitation, provide abundant stagnant water, creating ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes. More than one-third of the population still lacks access to safely managed sanitation, and UNICEF estimates that about 230 tons of fecal waste enter Dhaka’s 4,500-kilometer drainage network every day. The system is already 70% clogged with trash and debris because of poor infrastructure and longstanding neglect, according to the Institute of Water Modelling [

83,

84]. As a result, even moderate rainfall creates stagnant, mosquito-infested pools—a problem further intensified by flooding and extreme weather across both urban and rural areas [

85]. Additionally, in many dense urban neighborhoods, inconsistent water supply forces residents to store water in containers [

43], a practice well documented in neighboring India, further increasing the risk of mosquito-borne diseases [

86].

Poor waste management is a critical driver of dengue risk among both children and adults—and in urban Bangladesh this threat looms large. Shockingly, 55% of solid waste in urban areas remains uncollected, creating ideal breeding grounds for the mosquitoes that spread the disease [

87]. Evidence from urban Thiruvanathapuram, South India, indicates that inadequate waste management infrastructure can be associated with a 40% higher incidence of dengue and chikungunya cases [

88]. Likewise, studies in informal urban settlements in Indonesia and Fiji reported that by age 4–5, over half of children had already been infected, highlighting how insufficient waste disposal accelerates early exposure to dengue [

89].

Pollution as a Trigger for Viral Resistance and Mosquito Dynamics

The WHO estimates that nearly a quarter of human diseases and deaths stem from long-term exposure to pollution [

90]. While research on environmental impacts on dengue in Bangladesh remains limited, international studies underscore their significance. Recent findings from cities in Taiwan [

91], Singapore [

92], Guangzhou [

93], Upper Northern Thailand [

94], Melaka, Malaysia [

95], and Greater São Paulo [

96] demonstrate that air pollutants—such as particulate matter PM2.5, SO₂, O₃, CO, and NOx—interact with climate factors to influence mosquito populations, viral activity, and human immunity to the virus. These impacts, however, vary depending on pollutant type, concentration, and region, often producing complex, non-linear effects on mosquito dynamics. Interestingly, a study covering 76 provinces in Thailand from 2003 to 2021 found that higher surface concentrations of SO₂ and PM2.5 were generally associated with lower incidences of dengue, malaria, chikungunya, and Japanese encephalitis, likely due to adverse effects on mosquito survival and behavior [

97]. These findings highlight the need for further research.

A

Lancet study reported that improperly discarded plastics accumulate stagnant water, creating ideal breeding sites for

Aedes mosquitoes that transmit dengue, Zika, chikungunya, and yellow fever, thereby directly increasing vector populations. Indirectly, plastic debris also clogs drainage systems, producing large stagnant pools that promote mosquito proliferation and elevate the risk of diseases such as malaria [

98]. Bangladesh is now experiencing an alarming rise in micro plastic pollution. Just three rivers--Meghna, Karnaphuli, and Rupsha discharge nearly one million metric tons of mismanaged plastic each year [

99]. In total, 36 rivers in Bangladesh are among the 1,656 waterways worldwide responsible for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions [

100]. Per-capita plastic consumption has tripled—from 9 kg in 2005 to 2020—while COVID-19 contributed an additional 78,000 tons in a single year, according to a 2021 report by the Environment and Social Development Organization (ESDO) [

101].

In Dhaka, per-capita use reaches 24 kg, and nearly one-eighth of all plastic waste ends up in canals and rivers. An estimated 23,000 to 36,000 tons of plastic waste accumulate annually across 1,212 dumping hotspots surrounding the Buriganga, Turag, Balu, and Shitalakhsya rivers, a trend highlighted by a former World Bank country director during a program in Dhaka [

102]. Beyond environmental degradation, this rising plastic burden may intensify mosquito-borne disease risks: researchers from the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology show that mosquitoes exposed to micro plastics can transfer them to mammals, develop altered gut microbiomes, experience delayed development, and exhibit reduced insecticide susceptibility—factors that could heighten disease transmission [

103]. Also, micro plastics can adsorb pyrethroid insecticides such as deltamethrin, reducing the concentration available to act on mosquitoes. However, because the findings rely on a single study and other research shows conflicting results, more evidence is needed to clarify how micro plastic exposure influences mosquito dynamics and dengue transmission.

Construction Sites and High-Rises: Major Breeding Grounds Driving Dengue in Dhaka

Dhaka’s rapid and largely unplanned urban expansion has transformed the city into a highly conducive environment for

Aedes mosquito proliferation. Numerous under-construction buildings, left exposed to the elements, now serve as prime breeding grounds for the vectors of dengue. Surveys indicate that, in the decade preceding 2016, an average of 95,000 new structures were erected annually within the jurisdiction of the Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha (RAJUK). Over the subsequent fifteen years, at least 64,000 additional buildings were constructed across the capital [

104,

105]. In July 2020, inspections conducted by the Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC) revealed that nearly 70% (8,764 out of 12,619) of homes and construction sites surveyed across 55 wards harbored potential

Aedes breeding sources [

106]. These inspections were carried out in collaboration with the National Malaria Elimination and

Aedes Transmitted Disease Control Programme under the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS).

The following year, the situation deteriorated further. A 2021 DGHS study covering 70 areas of Dhaka reported alarming

Aedes densities, with the Breteau Index (BI)—the number of water-holding containers infested with larvae per 100 houses—rising to 23.3 in Lalmatia and Iqbal Road (Ward 32, DNCC) and 20.0 in Sayedabad and Uttar Jatrabari (Ward 48, DSCC). High-rise buildings accounted for over 45% of breeding sites, followed by under-construction structures at nearly 35% [

107]. In 2024, the former Mayor of DSCC warned that construction would be halted wherever

Aedes larvae were detected and that dengue control drives would be launched in advance of the rainy season, alongside the government’s seven-year National Dengue Prevention and Control Strategy [

108]. The most recent pre-monsoon survey, conducted jointly by the DGHS Communicable Disease Control Programme and the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR), presents a similarly concerning picture: multistory buildings accounted for almost 60% of

Aedes larvae, with a further 20% found in under-construction sites [

109].

From Neglect to Epidemic: How Policy Failures Worsened Dengue in Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s authorities have repeatedly failed to curb

Aedes populations, persisting with outdated chemical approaches while neglecting structural determinants and community-level interventions. Government action has remained fragmented and reactive; in 2023, officials proved unable to control

Aedes mosquitoes, opting instead to fault households and impose ethically questionable fines. Such mismanagement and flawed strategies have allowed dengue transmission to escalate unchecked, rendering official prevention efforts largely performative (

Figure 5). Transparency International Bangladesh has identified several drivers of high mortality, including inadequate hospital staffing, delayed diagnoses, false-negative NS1 results, weak vector-control measures, and limited healthcare capacity beyond Dhaka [

110]. Experts further warn that the absence of strategic planning, non-adherence to WHO guidelines, and the failure to involve qualified public-health professionals have deepened the crisis. By 2024, South Asia was experiencing its most severe dengue epidemic on record, with Bangladesh and India reporting thousands of deaths as hospitals were overwhelmed. Concerns have mounted over inadequate anti-mosquito measures and the near absence of public awareness campaigns, shortcomings partly attributed to the lack of elected union parishad leadership under the interim government. Yet Dhaka’s two city corporations have spent more than BDT 1,000 crore (over USD 81 million) on mosquito-control programs in the past decade, even as the capital continues to account for the majority of infections and fatalities [

111]. In 2023 alone, Dhaka recorded more than half of all cases and nearly 70 per cent of fatalities, underscoring that vector-borne outbreaks transcend partisan boundaries [

112]. In FY 2024–25, Dhaka South City Corporation spent less than 40 per cent of its overall budget despite increasing its mosquito-control allocation by 19% [

113]. Weak implementation, poor coordination, obsolete operational strategies, and persistent shortages of chemicals and manpower have severely undermined larviciding, mosquito-control, and drain-cleaning activities.

Conclusions

In Bangladesh, rising temperatures, unplanned urban expansion, and worsening pollution have created conditions that strongly favor mosquito proliferation, turning rapid development into a relentless battle against one of the country’s deadliest tiny predators. The persistent and evolving threat of dengue underscores the need for timely hospitalization—because the illness can deteriorate quickly—as well as systematic research to understand how environmental pollution, climate variability, and extensive pesticide use are shaping viral resistance and mosquito behavior. Media coverage has largely failed to capture the severity of the crisis, and domestic research remains limited, often attributing outbreaks only to erratic rainfall, monsoon shifts, and stagnant water.

Yet evidence from regions with similar dengue patterns points to several overlooked drivers, including air pollution, pesticide and micro plastic resistance, and the complex interactions between rapid urbanization and mosquito ecology. With low levels of health literacy, even strong research rarely translates into public awareness or policy reform, and progress in evidence-based studies remains slow. Coordinated efforts that combine early clinical care with rigorous scientific investigation are therefore essential to mitigating the country’s growing dengue burden.

This national tragedy is part of a much larger global shift. A study in Nature warns that by 2080, nearly three in five people could be at risk of dengue [

114]. Last year alone, more than fourteen million people were infected worldwide—twice the previous year and twelve times higher than a decade ago [

115,

116]. As climate instability, unplanned urbanization, and expanding mosquito habitats intensify, dengue is no longer a regional challenge—it is an emerging pandemic that demands urgent international action. The time to act is now, before a greater catastrophe unfolds and more lives are lost.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Institutional Review Board Statement

N/A.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from the Dengue Dynamic Dashboard for Bangladesh, maintained by the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), Health Emergency Operation Center & Control Room. These data are publicly available at:

https://dashboard.dghs.gov.bd/pages/heoc_dengue_v1.php.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Abbreviations

| BI |

Breteau Index |

| DGHS |

Directorate General of Health Services |

| DNCC |

Dhaka North City Corporation |

| DSCC |

Dhaka South City Corporation |

| IEDCR |

The Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research |

| NS1 |

Nonstructural Protein 1 |

| RAJUK |

Rajdhani Unnayan Kartripakkha |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Jackson A. World mosquito Day 2025 - A Global Health Crisis. World Mosquito Program. 2025 Aug 11.

- Roiz, D; Pontifes, PA; Jourdain, F; et al. The rising global economic costs of invasive Aedes mosquitoes and Aedes-borne diseases. Sci Total Environ. 2024, 933, 173054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Africa Region. Malaria; World Health Organization, 2023. [Google Scholar]

-

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), International Science Council (ISC). UNDRR–ISC Hazard Information Profiles – 2025 Update: BI0207 Dengue; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction; International Science Council, 2025.

- Ahmad, LC; Gill, BS; Sulaiman, LH; et al. Molecular epidemiology of dengue in Southeast Asia (SEA): Protocol of systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2025, 15, e088890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, SL; Hung, FY; Li, ST; et al. Dengue epidemiology in 7 Southeast Asian countries: 24-year, retrospective, multicountry ecological study. Interact J Med Res. 2025, 14, e70491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishen, S. The world is in the grip of a record dengue fever outbreak. What’s causing it and how can it be stopped? World Economic Forum 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Dengue - Global situation; Disease Outbreak News, 30 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Current dengue outbreak; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 29 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- eClinicalMedicine. Dengue as a growing global health concern. 2024, 77, 102975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.-X.; Zhao, T.-Y.; Wang, C.-C.; He, Y.; Lu, H.-Z.; Zhang, H.-T.; Wang, L.-M.; Mao, Z.; Li, C.-X.; Deng, S.-Q. Assessing the global dengue burden: Incidence, mortality, and disability trends over three decades. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2025, 19, e0012932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Dengue fact sheet; World Health Organization, 21 Aug 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S; Zhang, T; Sun, S; et al. The shift in mosquito-borne disease incidence across the Asia-Pacific region (1992–2021): Insights from an age-period-cohort analysis using the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, JH; Lim, AY; Kim, SH. Evaluating the effectiveness of dengue surveillance in the tropical and sub-tropical Asian nations through dengue case data from travelers returning to the five western Pacific countries and territories. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2025, 64, 102802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, A; Shearer, FM; Sewalk, K; Pigott, DM; Clarke, J; Ghouse, A; Judge, C; Kang, H; Messina, JP; Kraemer, MUG; Gaythorpe, KAM; de Souza, WM; Nsoesie, EO; Celone, M; Faria, N; Ryan, SJ; Rabe, IB; Rojas, DP; Hay, SI; Brownstein, JS; Golding, N; Brady, OJ. The overlapping global distribution of dengue, chikungunya, Zika and yellow fever. Nat Commun. 2025, 16, 3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Areas with Risk of Dengue. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Updated December 8, 2025.

- Ulgheri, FM; Bernardes, BG; Lancellotti, M. Decoding Dengue: A Global Perspective, History, Role, and Challenges. Pathogens 2025, 14, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, CW; Comrie, AC; Ernst, K. Climate and dengue transmission: evidence and implications. Environ Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengliu, F; Ma, Y; Qin, P; Zhao, Y; Liu, Z; Wang, W; Cheng, B. Temperature-Driven Dengue Transmission in a Changing Climate: Patterns, Trends, and Future Projections. GeoHealth 2024, 8, e2024GH001059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedum, CM; Seidahmed, OME; Eltahir, EAB; Markuzon, N. Statistical modeling of the effect of rainfall flushing on dengue transmission in Singapore. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018, 12, e0006935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophia, Y; Roxy, MK; Murtugudde, R; et al. Dengue dynamics, predictions, and future increase under changing monsoon climate in India. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monintja, TCN; Arsin, AA; Amiruddin, R; Syafar, M. Analysis of temperature and humidity on dengue hemorrhagic fever in Manado Municipality. Gaceta Sanitaria 2021, 35, S330–S333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, H; Gwee, S; Koh, J; Pang, J. Weather Factors Associated with Reduced Risk of Dengue Transmission in an Urbanized Tropical City. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 19, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyarit, J; Sriwongsuk, K; Putepapas, S; Intarasaksit, P. Environmental health factors influencing dengue: a systematic review with thematic categorization. Int J Environ Health Res. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nature Education. Dengue Transmission. Nature.com. Published 2014.

- Lozano-Fuentes, S; Hayden, MH; Welsh-Rodriguez, C; et al. The dengue virus mosquito vector Aedes aegypti at high elevation in Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012, 87, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieghart, L; Rogers, D. Bangladesh: The Challenges of Living in a Delta Country; World Bank Blogs, 19 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, MA; Sato, T. Influence of Terrestrial Precipitation on the Variability of Extreme Sea Levels along the Coast of Bangladesh. Water 2021, 13, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, D. Sustainable river management in Bangladesh: Challenges and ways forward; The Climate Watch, 1 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, W; Mahmud, I; Hossain, R. Bangladesh: Finding it difficult to keep cool; World Bank: Washington, DC, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, MN; Khalil, I; Chowdhury, MAB; et al. Two decades of endemic dengue in Bangladesh (2000–2022): trends, seasonality, and impact of temperature and rainfall patterns on transmission dynamics. J Med Entomol. 2024, 61, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonna, AS; Pavel, SR; Mehjabin, T; Ali, M. Dengue in Bangladesh. IJID One Health 2023, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmus Sakib, SM. Heavy rains may double dengue cases in Oct; The Financial Express, 4 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- TBS Report. Why Bangladesh seeing so much rain in October? The Business Standard, 11 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, J; Frentiu, FD; Devine, GJ; Bambrick, H; Hu, W. A state-of-the-science review of long-term predictions of climate change impacts on dengue transmission risk. Environ Health Perspect. 2025, 133, 56002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, MS; Shiddik, MAB. Explainable artificial intelligence for predicting dengue outbreaks in Bangladesh using eco-climatic triggers. Glob Epidemiol 2025, 10, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, MT; Kamal, ASMM; Islam, MM; Hossain, S. Time series patterns of dengue and associated climate variables in Bangladesh and Singapore (2000–2020): A comparative study of statistical models to forecast dengue cases. Int J Environ Health Res. 2025, 35, 2289–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, MS; Noman, AA; Mamun, SMAA; Mosabbir, AA. Twenty-two years of dengue outbreaks in Bangladesh: Epidemiology, clinical spectrum, serotypes, and future disease risks. Trop Med Health 2023, 51, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S; Akbar, SM; Mahtab, MA; et al. Bangladesh records persistently increased number of dengue deaths in recent years: Dissecting the shortcomings and means to resolve. IJID Regions 2024, 12, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, KE; Ahmed, MJ; Chalise, R; et al. Time series analysis of dengue incidence and its association with meteorological risk factors in Bangladesh. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0323238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, MA; Hasan, MN; Tiwari, A; et al. Correlation of dengue and meteorological factors in Bangladesh: A public health concern. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, J; Hu, W. Rapid human movement and dengue transmission in Bangladesh: A spatial and temporal analysis based on different policy measures of COVID-19 pandemic and Eid festival. Infect Dis Poverty 2024, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogieuhi, IJ; Ahmed, MM; Jamil, S; et al. Dengue fever in Bangladesh: Rising trends, contributing factors, and public health implications. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines 2025, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, AB; Hasan, M; Ahmed, A; Rahman, MH; Sikder, MT. Youth’s climate consciousness: Unraveling the dengue-climate connection in Bangladesh. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1346692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, MS; Karamehic-Muratovic, A; Baghbanzadeh, M; et al. Climate change and dengue fever knowledge, attitudes and practices in Bangladesh: A social media–based cross-sectional survey. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2020, 115, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, MdI; Alam, NE; Akter, S; et al. Knowledge, awareness and preventive practices of dengue outbreak in Bangladesh: A countrywide study. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0252852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, MM; Khan, SJ; Tanni, KN; et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practices towards dengue fever among university students of Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 4023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, MM; Tanni, KN; Roy, T; et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices towards dengue fever among slum dwellers: A case study in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Int J Public Health 2023, 68, 1605364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, MS; Amrin, M; Chowdhury, AH; Suwanbamrung, C; Karamehic-Muratovic, A. Knowledge and beliefs about climate change and emerging infectious diseases in Bangladesh: Implications for one health approach. J Health Popul Nutr. 2025, 44, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, R; Islam, MS; Mubarak, M; Rahman, M; Gesesew, HA; Ward, PR; Sikder, MT. Public knowledge, belief, and preventive practices regarding dengue: Findings from a community-based survey in rural Bangladesh. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023, 17, e0011778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, NF; Haque, MJ; Jahan, MS; Rashid, MAM; Mostafa, MG; Rashid, F. Knowledge, beliefs, and preventive practices regarding dengue among rural communities in Bangladesh. KYAMC J 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, SMMH; Rashid, MA; Trisha, SY; Ibrahim, M; Hossen, MS. Dengue investigation research in Bangladesh: Insights from a scoping review. Health Sci Rep. 2025, 8, e70568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pure, E; Husna, ALA; Rokony, S; Thowai, AS; Moulee, ST; Jahan, A; Khatun, A; Sarkar, M; Bibi, S; Tabassum, TT; Nurunnabi, M. Knowledge, attitude, and practices regarding dengue infection: A community-based study in rural Cox’s Bazar. J Commun Dis. 2025, 57, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, AK. Dengue protection and cure: Bangladesh perspective. Eur J Sustain Dev Res. 2019, 4, em0104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amin, HM; Johora, FT; Irish, SR; et al. Insecticide resistance status of Aedes aegypti in Bangladesh. Parasit Vectors 2020, 13, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amin, HM; Gyawali, N; Graham, M; et al. Insecticide resistance compromises the control of Aedes aegypti in Bangladesh. Pest Manag Sci. 2023, 79, 2846–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S; Islam, MdM; Hasan, MdA; Chowdhury, PB; Easty, IA; Tusar, MdK; Rashid, MB; Bashar, K. Association of climate factors with dengue incidence in Bangladesh, Dhaka City: A count regression approach. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R; Fincher, C. Bangladesh sees worst single-day surge in dengue cases and deaths this year; Reuters, 21 Sep 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A. Dengue deaths up 150%, cases double compared to last year; Bonik Barta, 22 Sep 2025. [Google Scholar]

- UNB. 8 more dead, 778 hospitalised as Bangladesh fails to curb dengue; United News of Bangladesh, 23 Nov 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, R. Dengue cases surge across Bangladesh as experts call for urgent action; Reuters, 7 Oct 2025. [Google Scholar]

- DGHS/UNICEF. Dengue Dynamic Dashboard for Bangladesh. Health Emergency Operation Center & Control Room, Directorate General of Health Services. Accessed 2025 Dec 8.

- News Desk. Dengue: Four more die, 920 hospitalised in 24Hrs; Daily Sun, 18 Nov 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Asaduzzaman, M; Khan, EA; Hasan, MN; et al. The 2023 dengue fatality in Bangladesh: Spatial and demographic insights. IJID Regions 2025, 15, 100654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, MS; Noman, AA; Mamun, SMAA; Mosabbir, AA. Twenty-two years of dengue outbreaks in Bangladesh: Epidemiology, clinical spectrum, serotypes, and future disease risks. Trop Med Health 2023, 51, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, JS; Martin, LE; Tate, AT; Hillyer, JF. Warmer environmental temperature accelerates aging in mosquitoes, decreasing longevity and worsening infection outcomes. Immun Ageing 2024, 21, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdomo, HD; Khorramnejad, A; Cham, NM; Kropf, A; Sogliani, D; Bonizzoni, M. Prolonged exposure to heat enhances mosquito tolerance to viral infection. Commun Biol. 2025, 8, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo, J. Mosquitoes found in Iceland for 1st time as temperatures in the region rise; ABC News, 22 Oct 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Galeana-Pizaña, JM; Cruz-Bello, GM; Caudillo-Cos, CA; Jiménez-Ortega, AD. Impact of deforestation and climate on spatio-temporal spread of dengue fever in Mexico. Spat Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol 2024, 50, 100679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, AC; Falcão, LA; Borges, MA; Leite, ME; Espírito Santo, MM. Are land use and cover changes and socioeconomic factors associated with the occurrence of dengue fever? A case study in Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Resources 2024, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, LS; Conn, JE; López, RV; Sallum, MA. Abundance of impacted forest patches <5 km2 is a key driver of the incidence of malaria in Amazonian Brazil. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 7077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawar, N; Sorker, R; Chowdhury, FJ; Mostafizur Rahman, Md. Present status and historical changes of urban green space in Dhaka City, Bangladesh: A remote sensing driven approach. Environ Chall. 2022, 6, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IIED. Hot Cities: Dhaka; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, Jun 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Bangladesh faces health and economic risks from rising temperature. Press Release, 16 Sep 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Banu, S; Hu, W; Guo, Y; Hurst, C; Tong, S. Projecting the impact of climate change on dengue transmission in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Environ Int. 2014, 63, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quam, J; Campbell, S. South Asia: Urban Geography I – Dhaka. In The Eastern World: Daily Readings on Geography; College of DuPage Digital Press, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNB. Dhaka world’s 2nd largest city with 36.6 million: UN; The Daily Star, 26 Nov 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, A; Islam, A; Hosna, A; Tahsin, A; Islam, A. The impact of urbanization on the proliferation of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquito population in Dhaka Mega City, Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Zool 2024, 52, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, AS; Al-Montakim, MdN; Hasan, MdA; et al. Relationship between urban environmental components and dengue prevalence in Dhaka City—An approach of spatial analysis of satellite remote sensing, hydro-climatic, and census dengue data. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S; Biswas, A; Shawon, MT; Akter, S; Rahman, MM. Land use and meteorological influences on dengue transmission dynamics in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2024, 48, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inspira Advisory and Consulting Limited. Challenges of slum living in Bangladesh: A closer look at WASH inequities in Bangladesh’s slums. Inspira-bd.com. 2023 Jul 17.

- Paulson, W; Kodali, NK; Balasubramani, K; et al. Social and housing indicators of dengue and chikungunya in Indian adults aged 45 and above: Analysis of a nationally representative survey (2017–18). Arch Public Health 2022, 80, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. 230 tons of fecal waste end up in open water bodies in Dhaka daily — UNICEF and WaterAid call for stronger sanitation management; UNICEF Bangladesh, 25 Feb 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, HMN. Dhaka’s drains, dengue, and denial; The Daily Star, 10 Jul 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, J; Asif, MH; Rahman, S; Hasan, M. Exploring mosquito hazards in Bangladesh: Challenges and sustainable solutions. IUBAT Rev. 2024, 7, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nature India. Poor access to tap water linked to dengue risk. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNB. A roundtable discussion on ‘Solid Waste Management – Challenges and Solutions for Bangladesh’; United Nations Bangladesh, 3 Oct 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sasi, MS; Lal, N. The impact of solid waste management practices on vector-borne disease risk in Thiruvananthapuram. Int J Multidiscip Res 2024, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, JI; Openshaw, JJ; Lin, A; et al. Seroprevalence, incidence estimates, and environmental risk factors for dengue, chikungunya, and Zika infection amongst children living in informal urban settlements in Indonesia and Fiji. BMC Infect Dis. 2025, 25, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Climate change, pollution and health: Impact of chemicals, waste and pollution on human health. Executive Board EB154/24. Geneva: WHO; 2023 Dec 18. WHO: Geneva.

- Lu, HC; Lin, FY; Huang, YH; Kao, YT; Loh, EW. Role of air pollutants in dengue fever incidence: Evidence from two southern cities in Taiwan. Pathog Glob Health 2022, 117, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailepessov, D; Ong, J; Aik, J. Influence of air pollution and climate variability on dengue in Singapore: A time-series analysis. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 13467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X; Zhang, W; Yimaer, W; et al. How air pollution altered the association of meteorological exposures and the incidence of dengue fever. Environ Res Lett. 2022, 17, 124041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongtip, S; Sapbamrer, P; Chaichanan, P; Chiablam, S; Pimonsree, S. Association of meteorology and air quality with dengue fever incidence in upper northern Thailand. EnvironmentAsia 2025, 18, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, AKH; Che Dom, N; Do Camalxaman, S; Syed Ismail, SN. Correlational analysis of air pollution index levels on dengue surveillance data: A retrospective study in Melaka, Malaysia. J Sustain Sci Manag. 2020, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, MAF; Alves, BCA; Gehrke, FS; et al. Environmental factors can influence dengue reported cases. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2017, 63, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tewari, P; Ma, P; Gan, G; et al. Non-linear associations between meteorological factors, ambient air pollutants and major mosquito-borne diseases in Thailand. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023, 17, e0011763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maquart, P-O; Froehlich, Y; Boyer, S. Plastic pollution and infectious diseases. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, e842–e845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroze, CA; Ahmed, MN; Azam, MN; Jahan, R; Rahman, H. Microplastics pollution in Bangladesh: A decade of challenges, impacts, and pathways to sustainability. Integr Environ Assess Manag 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, LJJ; van Emmerik, T; van der Ent, R; Schmidt, C; Lebreton, L. More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. Sci Adv. 2021, 7, eaaz5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment and Social Development Organization (ESDO). Huge use of poly bag: 78 thousand tons of waste in a year. ESDO, 5 Jun 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, SI. Urban per capita plastic use 9 kg, 24 kg in Dhaka. New Age, 20 Dec 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, JH; Liu, XH; Liang, GR; et al. Microplastics affect mosquito from aquatic to terrestrial lifestyles and are transferred to mammals through mosquito bites. Sci Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shopon, HU-R. Dhaka: Unplanned city faces a grand spectacle of risks (Article in Bengali); Deutsche Welle, 23 Jul 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, A. Building faults overlooked if officials are appeased; Prothomalo, 9 Mar 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tribune Desk. Potential Aedes breeding grounds found in 70% DNCC homes; Dhaka Tribune, 4 Jul 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Staff, Correspondent. Greetings and promises on our 15th anniversary. Aedes reproduction--High rises mainly responsible; Daily Sun, 6 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- TBS Report. Construction work will be halted if Aedes larvae found on site: Mayor Taposh; The Business Standard, 25 Apr 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Staff Correspondent. Dengue infection: 13 Dhaka wards at high risk; The Daily Star, 19 Jun 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M; Sultana, R; Julkarnayeen, M. Dengue crisis prevention and control: Governance challenges and way forward; Transparency International Bangladesh, 30 Oct 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, MdJ. Dengue rages as TK1,000CR lost to futile mosquito control efforts; The Business Standard, 16 Nov 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M; Rakib, MS; Hasan, MM; Powshi, SN; Islam, E; Islam, NN. The 2023 dengue outbreak in Bangladesh: An epidemiological update. Health Sci Rep. 2025, 8, e70852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TBS Report. Dhaka south increases mosquito control budget amid rising dengue infections, reports revenue growth; The Business Standard, 6 Aug 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Messina, JP; Brady, OJ; Golding, N; et al. The current and future global distribution and population at risk of dengue. Nat Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haider, N; Hasan, MN; Onyango, J; et al. Global dengue epidemic worsens with record 14 million cases and 9000 deaths reported in 2024. Int J Infect Dis. 2025, 158, 107940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US CDC. Dengue on the rise: Get the facts; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 29 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Trends in Dengue Cases and Deaths in Bangladesh, 2000–8 December 2025 (Source: The Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research, IEDCR) / Directorate General of Health Services, DGHS). The figure depicts a pronounced increase in dengue cases and deaths in Bangladesh during the post-COVID period, showing a closely aligned temporal pattern between case numbers and fatalities.

Figure 1.

Trends in Dengue Cases and Deaths in Bangladesh, 2000–8 December 2025 (Source: The Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research, IEDCR) / Directorate General of Health Services, DGHS). The figure depicts a pronounced increase in dengue cases and deaths in Bangladesh during the post-COVID period, showing a closely aligned temporal pattern between case numbers and fatalities.

Figure 2.

Trend in Dengue Cases in Bangladesh, 2018–November 2025 (Source: DGHS/Bangladesh Meteorological Department). The figure illustrates a clear upward trend in dengue transmission in Bangladesh since 2019, with a brief pause in 2020 consistent with global patterns. From June onwards, cases begin to rise sharply, closely following periods of elevated temperature, humidity, and rainfall. Peaks in dengue incidence consistently occur between September and November in recent years, a pattern that meteorologists attribute to the unusually high rainfall observed in October from 2022 to 2025 (visualized using Canva Illustrator).

Figure 2.

Trend in Dengue Cases in Bangladesh, 2018–November 2025 (Source: DGHS/Bangladesh Meteorological Department). The figure illustrates a clear upward trend in dengue transmission in Bangladesh since 2019, with a brief pause in 2020 consistent with global patterns. From June onwards, cases begin to rise sharply, closely following periods of elevated temperature, humidity, and rainfall. Peaks in dengue incidence consistently occur between September and November in recent years, a pattern that meteorologists attribute to the unusually high rainfall observed in October from 2022 to 2025 (visualized using Canva Illustrator).

Figure 3.

Monthly Incidence of Dengue Cases and Dengue-Related Deaths in Bangladesh up to November 2025 (Source: DGHS). The figure shows a sharp rise in dengue cases and deaths beginning in June, with reported infections nearly quadrupling by October. The situation peaked in November 2025, when more than 24,500 cases and 100 deaths were recorded—over a quarter of the year’s total burden concentrated in a single month.

Figure 3.

Monthly Incidence of Dengue Cases and Dengue-Related Deaths in Bangladesh up to November 2025 (Source: DGHS). The figure shows a sharp rise in dengue cases and deaths beginning in June, with reported infections nearly quadrupling by October. The situation peaked in November 2025, when more than 24,500 cases and 100 deaths were recorded—over a quarter of the year’s total burden concentrated in a single month.

Figure 4.

Demographic shifts in male and female cases and deaths, 2023–December 8, 2025 (Data Source: DGHS). The figure illustrates a pronounced demographic transition: male cases surged sharply in 2024 before leveling off in 2025, whereas female cases initially declined and later partially rebounded. Concurrently, male deaths exhibited a steady rise, surpassing female deaths by 2025—a striking reversal from previous years (visualized using Canva Illustrator).

Figure 4.

Demographic shifts in male and female cases and deaths, 2023–December 8, 2025 (Data Source: DGHS). The figure illustrates a pronounced demographic transition: male cases surged sharply in 2024 before leveling off in 2025, whereas female cases initially declined and later partially rebounded. Concurrently, male deaths exhibited a steady rise, surpassing female deaths by 2025—a striking reversal from previous years (visualized using Canva Illustrator).

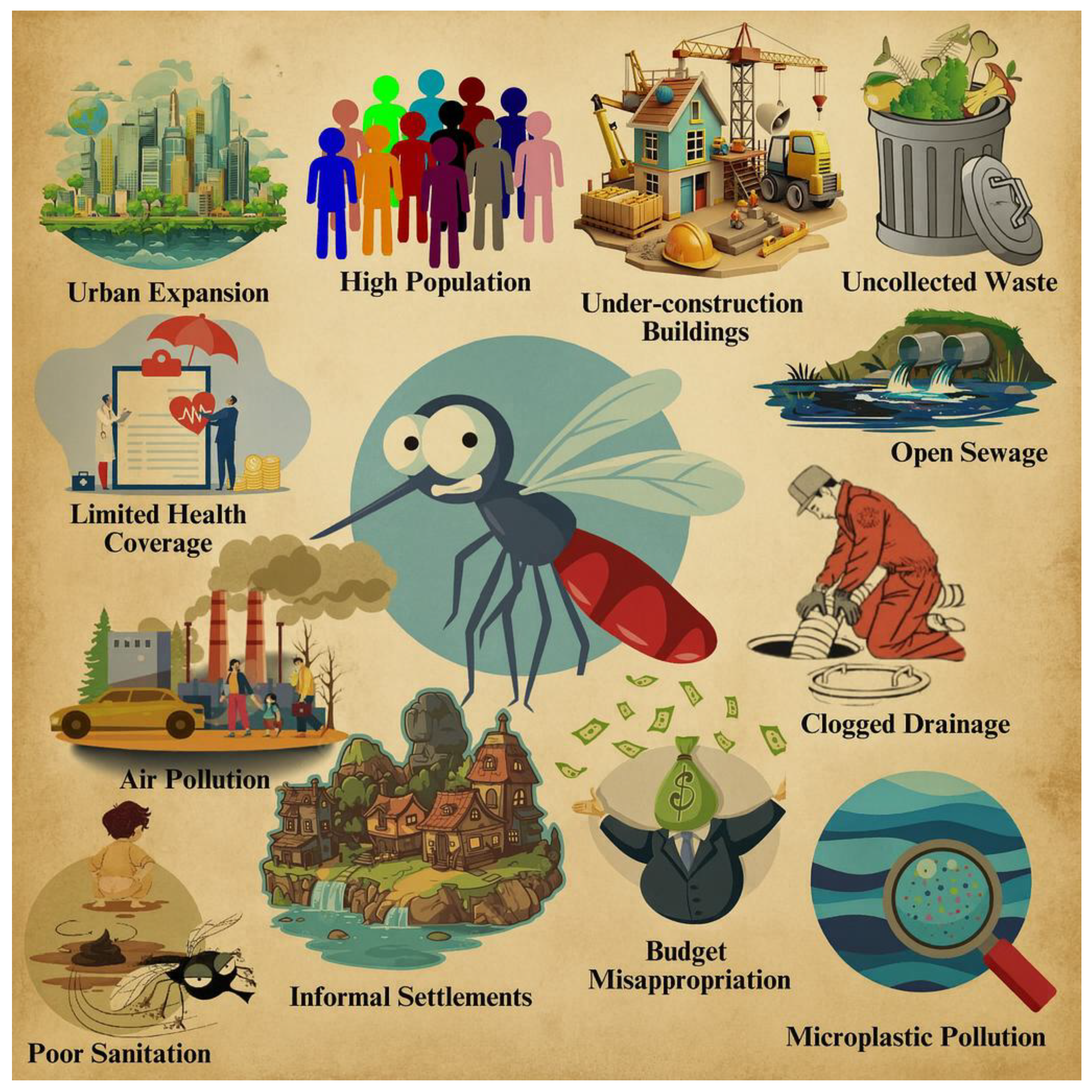

Figure 5.

Key Drivers of Bangladesh’s Rising Dengue Surge. Bangladesh’s dengue surge reflects a dangerous convergence of climate stress, rapid urbanization, dense settlements, and chronic sanitation failures, which together have created ideal conditions for Aedes mosquitoes to flourish. Shifting infection patterns—rising male fatalities, high hospital admissions, and a disproportionate burden on young people—underscore a worsening public-health emergency driven by environmental degradation, waste mismanagement, and construction-related breeding sites. The infographic illustrates how these interconnected pressures—heat, overcrowding, poor waste disposal, irregular water supply, declining green cover, and ineffective vector control—are fueling an escalating nationwide epidemic.

Figure 5.

Key Drivers of Bangladesh’s Rising Dengue Surge. Bangladesh’s dengue surge reflects a dangerous convergence of climate stress, rapid urbanization, dense settlements, and chronic sanitation failures, which together have created ideal conditions for Aedes mosquitoes to flourish. Shifting infection patterns—rising male fatalities, high hospital admissions, and a disproportionate burden on young people—underscore a worsening public-health emergency driven by environmental degradation, waste mismanagement, and construction-related breeding sites. The infographic illustrates how these interconnected pressures—heat, overcrowding, poor waste disposal, irregular water supply, declining green cover, and ineffective vector control—are fueling an escalating nationwide epidemic.

Table 1.

Determinants of Dengue Transmission: Climatic, Environmental, and Geographic Factors.

Table 1.

Determinants of Dengue Transmission: Climatic, Environmental, and Geographic Factors.

| Factor |

Key Points |

Evidence / Findings |

| Climate |

Shapes dengue ecology by influencing vector dynamics, virus development, and mosquito–human interactions. |

Relationships between climate variables and dengue transmission are complex [18]. |

| Temperature |

Rising temperatures increase dengue risk. |

Regions with notable warming, such as sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania, show higher dengue incidence [19]. |

| Rainfall |

Provides breeding sites for mosquitoes. |

Excess rainfall can wash away breeding sites, affecting outbreak patterns [20,21]. |

| Humidity |

Higher humidity supports mosquito survival and virus transmission. |

Humidity ≥60% and temperatures >27 °C elevate dengue risk; mosquitoes rarely survive below 60% humidity [21,22]. |

| Wind Speed |

Influences mosquito activity and breeding. |

Higher wind speeds reduce transmission by limiting mosquito flight, host-seeking, and breeding-site availability [23]. |

| Environmental Conditions |

Impact mosquito breeding and dengue transmission. |

Key factors include water storage, waste disposal, housing, drainage, vegetation, urbanization, seasonal variation, and water supply [24]. |

| Geography |

Vector thrives in tropical and subtropical regions. |

Spread is dictated by climate, urbanization, and population movement [12]. |

| Latitude |

Determines the global range of dengue. |

Aedes aegypti thrives between ~35°N–35°S; warming expands risk to higher latitudes, including Africa, South America, southern China, and the U.S. [19,25]. |

| Altitude |

Limits mosquito habitats. |

Mosquitoes generally stay below 6,500 ft; common up to 1,700 m, rare between 1,700–2,130 m; warming may increase risk at higher elevations [16,25,26]. |

Table 2.

Knowledge, Perception, and Attitudes Towards Dengue in Various Bangladeshi Populations.

Table 2.

Knowledge, Perception, and Attitudes Towards Dengue in Various Bangladeshi Populations.

| Study Place/ Population |

Knowledge |

Perception & Attitude |

| 1,358 youths of capital Dhaka |

Higher climate change knowledge; links with dengue awareness |

Positive attitude toward dengue–climate connection; socio-demographic/lifestyle factors influence awareness [44] |

| Students via social media survey |

Strong climate-change awareness; weak dengue-prevention knowledge |

Solid attitudes; past dengue experience predicts preventive behaviors [45] |

| 1,010 respondents across 9 regions |

Widespread awareness; educated/urban/better-off had higher knowledge |

Misconceptions persist (e.g., Aedes breed in dirty water); weak preventive practices [46] |

| Dhaka university students |

Good knowledge/practices; gaps in transmission, breeding sites, pregnancy-related risks |

Strong attitudes; mixed-unit residents showed weakest preparedness [47] |

| 745 slum dwellers of Dhaka |

Recognized dengue severity and transmission |

Low perceived personal risk; 60% inadequate preventive measures [48] |

| 1,905 Northern-region residents |

Limited awareness; poor understanding of climate-disease link |

Perception and attitude not well-developed [49] |

| 401 rural residents, Savar |

Moderate knowledge; influenced by education, age, gender, occupation, health beliefs |

High perceived severity; preventive practices unsatisfactory [50] |

| 364 rural adults from Puthia & Paba upazila |

48.4% had sufficient knowledge; higher education → better awareness |

Gaps in understanding transmission/prevention; attitude not emphasized [51] |

| Scoping review of 27 studies |

Moderate knowledge overall; rural/slum populations lower |

Varying perception; rural/slum communities had weak preventive practices [52] |

| 484 adults of Cox’s Bazar |

Average knowledge (84.3%) |

Positive attitude (63%); knowledge/attitude linked to preventive practices [53] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).