1. Introduction

Inkjet printing is widely used to manufacture flexible and wearable electronics because it allows patterned deposition without masks and supports rapid prototyping. However, the final printed quality is not determined only by the ejection and landing of droplets. It is heavily controlled by what happens during drying: evaporation sets up flows inside the droplet, and these flows transport solutes and particles to specific regions of the footprint. If the internal transport is not controlled, the droplet can dry into a non-uniform deposit (for example, a ring at the edge), which can reduce conductivity and cause defects in printed lines and pads [1,15,16,17,28,30,37,39].

1.1. Why Droplets Form Rings and Why That Matters for Printing

A classical example is the coffee-ring effect, where non-uniform evaporation is strongest near the pinned contact line, forcing an outward capillary flow that carries suspended or dissolved material to the edge [1,4,28]. Foundational models and experiments show that the evaporation rate and deposit shape depend on geometry, contact-line pinning, wetting, and diffusion of vapor into the surrounding gas [2,4,23,24,29]. This is a serious concern for conductive inks: if metal precursor or nanoparticles pile up at the edge, printed features can become rough, non-uniform, and electrically unreliable [17,37,39].

Deposit morphology is also sensitive to particle interactions and to how particles rearrange during drying. For colloidal or nanoparticle-laden droplets, pattern formation can include rings, multiple rings, islands, and more complex morphologies [9,10,15,25,26,54]. The deposit can transition from more ordered to disordered structures as drying conditions change [26]. In many practical cases, suppressing the coffee-ring effect is desired, and one widely cited approach is to modify capillary interactions by controlling particle shape [31,50].

1.2. Marangoni Flow and Multicomponent Effects: The Real Complexity

Capillary flow is only part of the story. Surface-tension gradients along the interface create Marangoni stresses that drive interfacial shear and recirculating flow [3,18]. These gradients can come from temperature variations (thermocapillary Marangoni) or composition variations (solutal Marangoni). Substrate thermal conductivity can even reverse the direction of internal circulation by changing how heat is supplied to the interface [6]. This is one reason heated substrates are powerful levers in printing: heating can accelerate drying, but it also changes flow direction and strength.

Binary droplets (and, more generally, multicomponent droplets) exhibit even richer behavior because one solvent evaporates faster than the other. Preferential evaporation creates concentration gradients, which can trigger solutal Marangoni flow, flow transitions, and multiple circulation cells [8,11,13]. Recent studies emphasize that the temperature-driven and concentration-driven Marangoni effects can compete, and the net circulation depends on the balance between these two contributions [8,11,13,19]. This is highly relevant for reactive silver inks, where a low-volatility component such as ethylene glycol (EG) is commonly added to tune viscosity, slow drying, and shape transport pathways. As water evaporates faster, EG can accumulate near the interface and contact line, altering surface tension and diffusion properties and changing the drying pathway [13,21,53].

1.3. Inkjet-Specific Context and Motivation for Modeling

Printing also involves process constraints that go beyond evaporation on a plate. Droplet generation depends on printhead actuation and jetting dynamics [40]. Printability depends strongly on fluid properties such as viscosity, surface tension, and density [42], and droplet formation modeling has a long history in materials processing [48]. In many applications, printed features are formed by arrays of droplets that merge, spread, and dry into thin films or lines; the final morphology can be influenced by dewetting or instabilities in the deposited liquid/film [14]. Drying can also be affected by absorption into porous substrates or by surfactants, which can change both wetting and evaporation dynamics [11,53].

Because so many mechanisms interact, predictive simulation is attractive: it can narrow down solvent ratios and substrate temperatures before running costly print trials. However, faithful modeling is challenging because evaporation, heat transfer, flow, and multicomponent diffusion are tightly coupled and evolve with time [22,27,30]. Finite-element-based studies have shown that coupled numerical models can reproduce realistic evaporation dynamics and solvent segregation in multicomponent droplets [12,13,21]. Several recent studies have reported complementary insights into thermal transport and evaporation phenomena in micro- and nanoscale systems using both numerical and molecular approaches [43,44,45,46,47]. Gradient-dynamics descriptions also provide a complementary perspective on how mixtures and suspensions evolve during drying [55]. Motivated by this literature, the goal of the present work is to develop a practical, time-dependent COMSOL model that couples:

evaporation-driven capillary flow linked to mass loss at the interface [1,4,28],

non-isothermal effects (evaporative cooling and substrate heating) [3,6,18,19,20],

multicomponent diffusion via Maxwell–Stefan transport [13,21],

and Marangoni stresses due to both temperature and composition gradients [3,8,11,13].

The model is designed to be understandable, reproducible, and directly useful for inkjet-printing process optimization.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Model Domain and Physics Interfaces

We simulate a single sessile droplet on a heated substrate using a 2D axisymmetric domain. This assumption is appropriate when the droplet remains approximately axisymmetric (as is common for droplets printed on smooth, homogeneous substrates without strong external airflow). It greatly reduces computational cost while still capturing the dominant coupled transport processes inside the droplet [2,12,27,29].

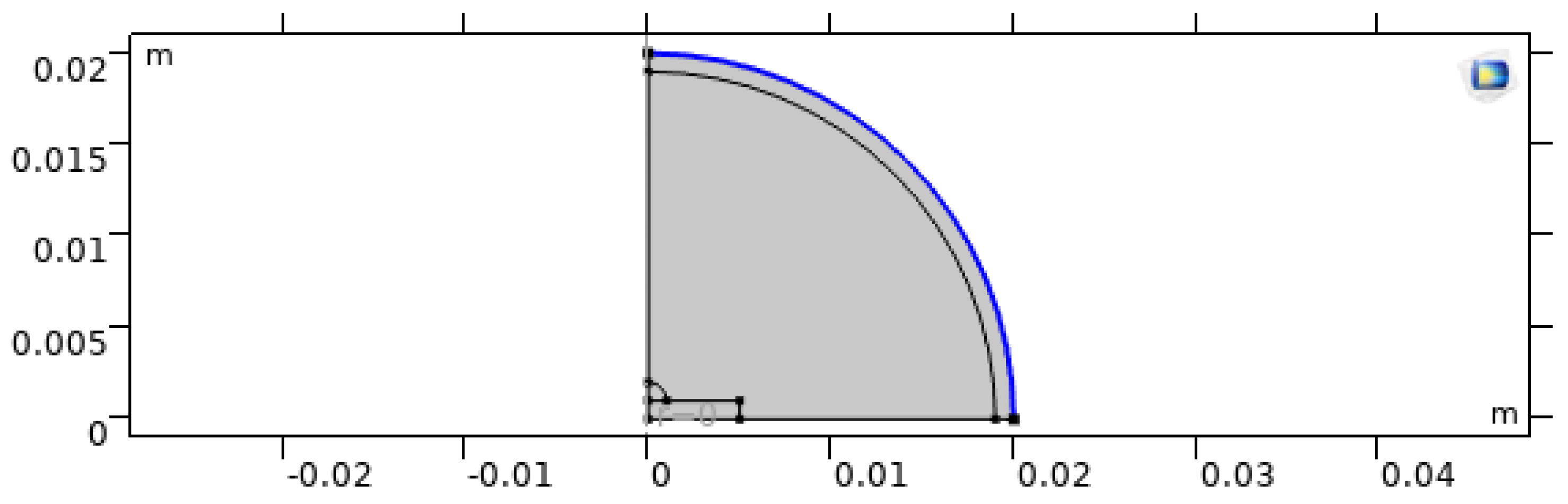

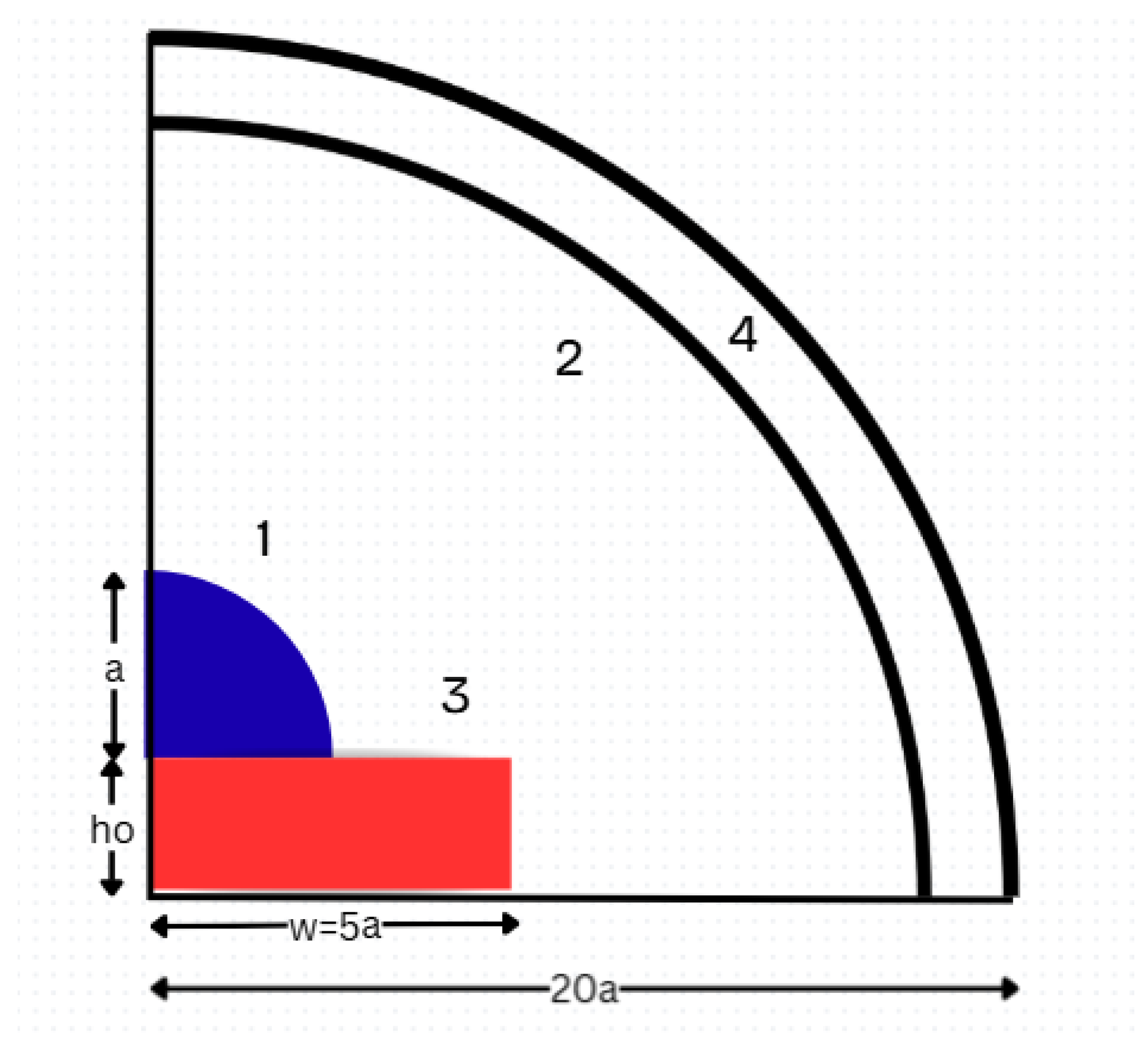

The computational domain includes four zones (

Figure 1) [12,27]:

Zone (1): Droplet. A quarter-sphere (in axisymmetric coordinates) with radius a.

Zone (2): Surrounding gas. A quarter-sphere with radius to represent a sufficiently large ambient region.

Zone (3): Heated substrate. A rectangular solid of width and thickness .

Zone (4): Far-field boundary. The outer boundary of Zone (2), representing open atmosphere where vapor can diffuse away.

In the simulations, we couple Laminar Flow, Heat Transfer in Fluids, Transport of Concentrated Species (Maxwell–Stefan), and a moving-boundary representation for the evaporating interface [12,13,21]. This coupled approach is consistent with modern finite-element treatments of evaporating multicomponent droplets [12,13] and with the broader physics of evaporating drops [22,27].

2.2. Key Modeling Assumptions

To keep the model focused and computationally practical, we adopt the following assumptions:

The liquid is incompressible and Newtonian (reasonable for many printing solvent mixtures at moderate shear rates) [42].

The droplet remains pinned at the contact line throughout the simulated drying period, a common regime for coffee-ring formation and many printed droplets [1,4,28].

The gas phase is treated as quiescent (no imposed airflow), so vapor transport in the gas is dominated by diffusion [2,23,29].

The model resolves coupled temperature and composition fields and includes Marangoni stresses arising from both gradients [3,8,11].

We focus on solvent transport (water/EG) and treat the non-volatile silver components implicitly by interpreting the flow and segregation fields as drivers of where solids or reactions may concentrate [15,30].

These assumptions align with a large body of evaporation and deposit-formation literature [2,7,22,30].

2.3. Governing Equations

2.3.1. Laminar Flow

The incompressible Navier–Stokes equations govern the velocity field

and pressure

p:

where

is density and

is dynamic viscosity. The body force

is included to allow buoyancy-driven contributions when relevant (even though many millimeter-scale droplets remain largely surface-tension-dominated) [19,20]. This formulation is widely used in droplet evaporation modeling [18,19,20,52].

2.3.2. Heat Transfer

The transient energy equation with advection and conduction is:

where

is the specific heat and

k is the thermal conductivity. This equation captures heat supply from the substrate, heat transport by internal circulation, and heat removal at the interface due to evaporation (implemented as a boundary condition). Temperature gradients are central to thermocapillary Marangoni flow [3,6,18] and strongly influence evaporation rates and drying time [20,22,52].

2.3.3. Species Transport (Maxwell–Stefan)

The EG mass fraction (or equivalent concentration variable) is modeled using Maxwell–Stefan diffusion:

where

is the diffusive flux computed using the Maxwell–Stefan formulation. This framework is more appropriate than simple Fickian diffusion when multicomponent interactions matter and has been applied successfully to evaporating binary/multicomponent droplets [13,21]. Species gradients are responsible for solutal Marangoni stresses and flow transitions observed in binary droplets [8,11,13].

2.4. Boundary Conditions and Evaporation Coupling

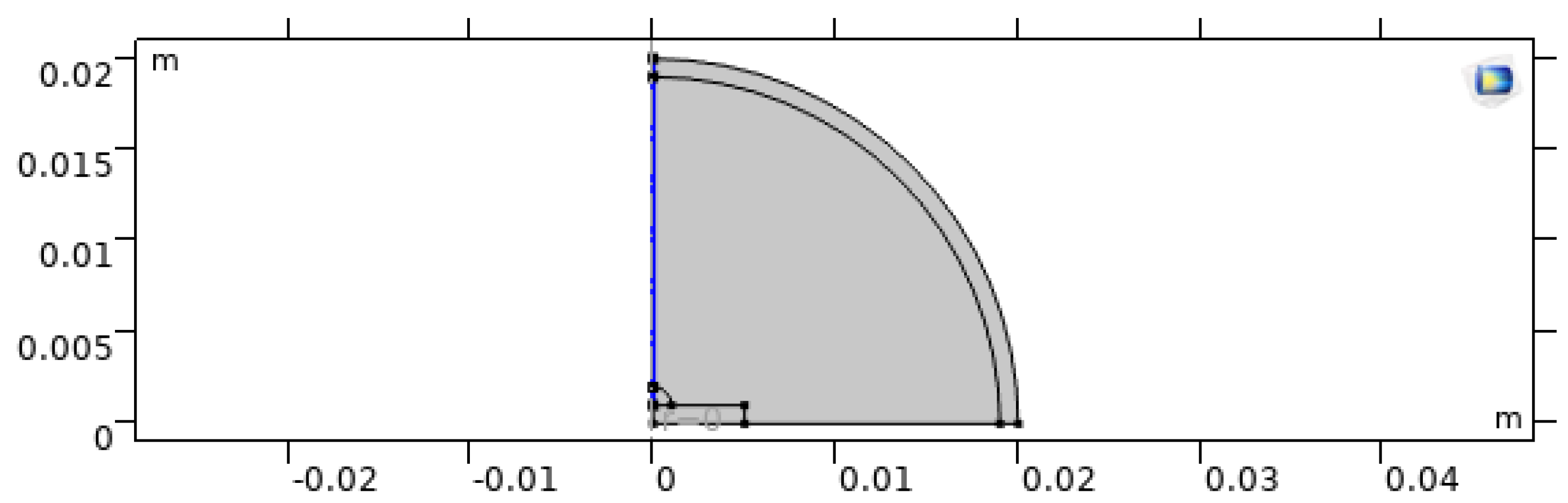

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 summarize the boundary-condition types used in the model. The boundary conditions are chosen to match the dominant physical processes described in classical evaporation studies [2,4,23] and more recent multicomponent and FEM-based models [12,13,21].

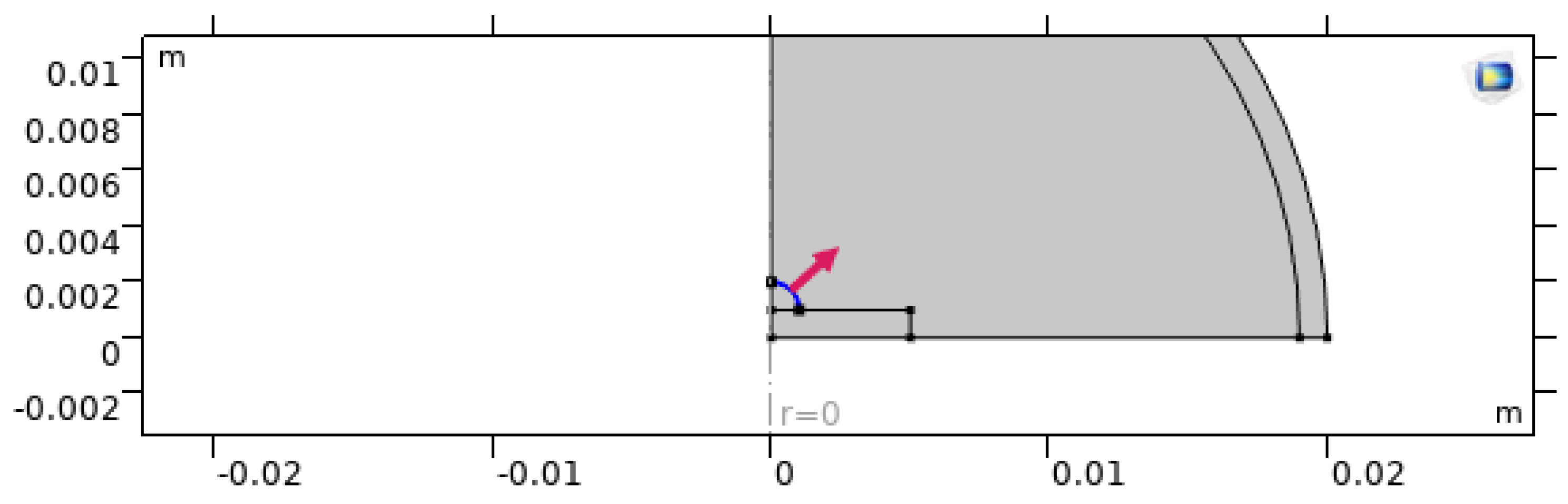

Heated substrate (wall)

No-slip condition is applied at solid boundaries. For heat transfer, a prescribed substrate temperature (or equivalently a prescribed heat flux) provides the thermal driving that accelerates evaporation and strengthens Marangoni flow [6,20,52].

Axis of symmetry

Axisymmetric constraints enforce symmetry in velocity, temperature, and concentration fields. This removes artificial flux across the axis and represents a full 3D droplet as a rotated 2D cross-section [51].

Liquid–vapor interface (moving boundary)

Marangoni stress is imposed through tangential stress balance:

where

depends on temperature and local composition. This allows both thermocapillary and solutal Marangoni contributions to drive flow [3,8,11,18].

Evaporative mass flux is applied as:

consistent with diffusion-limited evaporation in quiescent air [2,4,23,29]. The latent heat sink is applied as:

which couples mass loss to interfacial cooling and therefore to thermocapillary flow [3,20,21,22].

We note that related thin-film treatments show that vapor diffusion and Marangoni effects can also trigger instabilities in evaporating films, which motivates careful numerical stabilization near the interface [35,36].

Figure 2.

No-slip wall boundary condition applied to solid boundaries and thermal continuity at the droplet–substrate interface.

Figure 2.

No-slip wall boundary condition applied to solid boundaries and thermal continuity at the droplet–substrate interface.

Figure 3.

Evaporative flux boundary condition applied at the liquid–air interface (coupled with latent heat sink).

Figure 3.

Evaporative flux boundary condition applied at the liquid–air interface (coupled with latent heat sink).

Figure 4.

Axisymmetric boundary condition enforced along the centerline.

Figure 4.

Axisymmetric boundary condition enforced along the centerline.

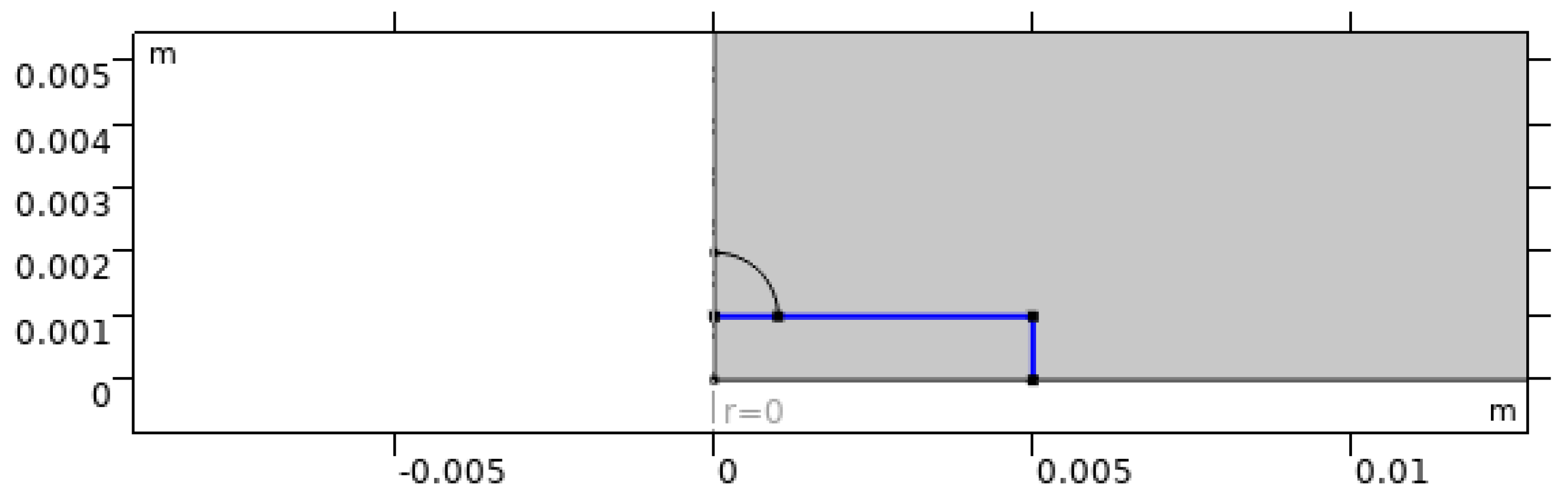

Figure 5.

Prescribed substrate temperature boundary condition representing the heated plate.

Figure 5.

Prescribed substrate temperature boundary condition representing the heated plate.

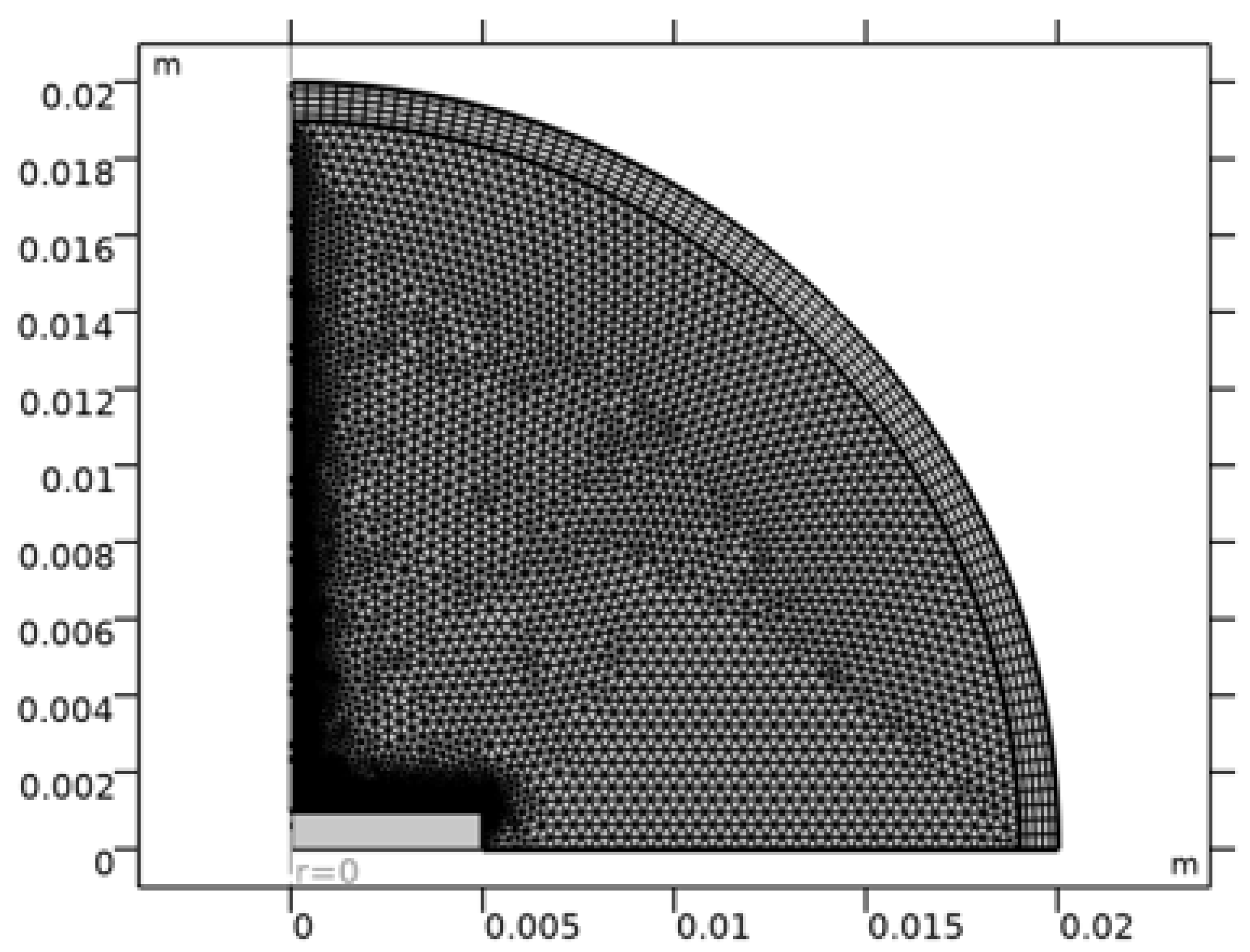

2.5. Meshing and Solver Configuration

The finite element mesh is refined near (i) the contact line, (ii) the liquid–vapor interface, and (iii) the heated substrate, because these locations typically exhibit sharp gradients in evaporation flux, temperature, and composition. Accurate resolution near the contact line is especially important in pinned evaporation problems because the evaporation flux tends to be strongest near the edge [1,2,4] and because Marangoni shear is often concentrated near the interface [3,6,19]. Mesh refinement is also standard in detailed FEM models of multicomponent droplets [12].

The mesh used is shown in

Figure 6. A time-dependent solver with segregated coupling is employed. In practice, segregated approaches can be more stable for tightly coupled multiphysics problems than fully coupled solves, especially when strong gradients appear during evaporation [12,19]. Similar numerical strategies are common in the modeling literature for coupled evaporation and internal flow [21,52].

3. Results and Discussion

This section describes the main trends predicted by the coupled model. We organize the discussion around questions that matter directly for inkjet printing:

How strong is the internal circulation, and where is it located?

How does evaporative cooling reshape the temperature field over time?

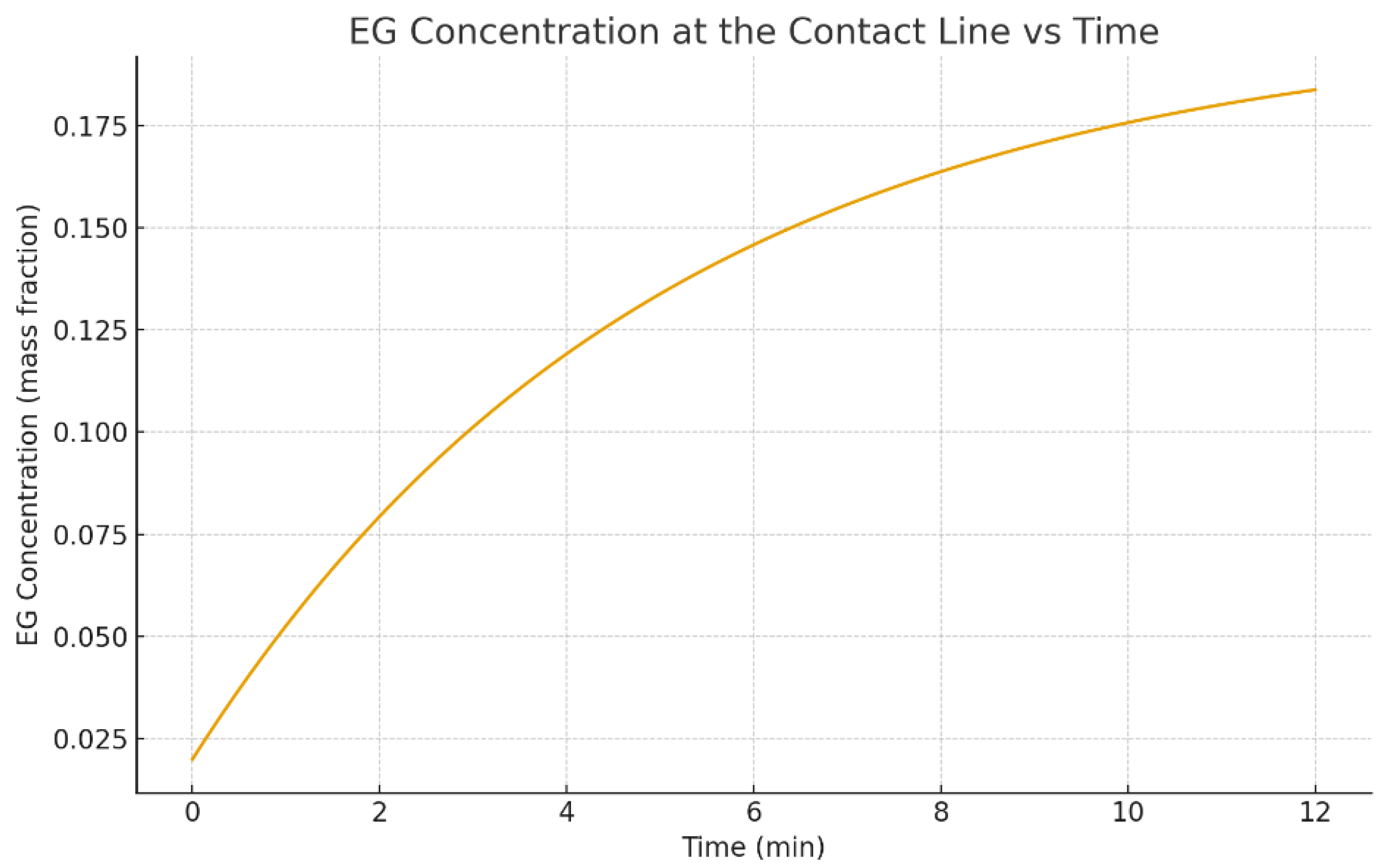

How quickly does EG segregate, and where does it accumulate?

How do these transport processes connect to common deposit outcomes such as rings versus more uniform coatings?

These questions align with the broader literature on deposit formation and evaporation-driven self-assembly [1,10,15,30].

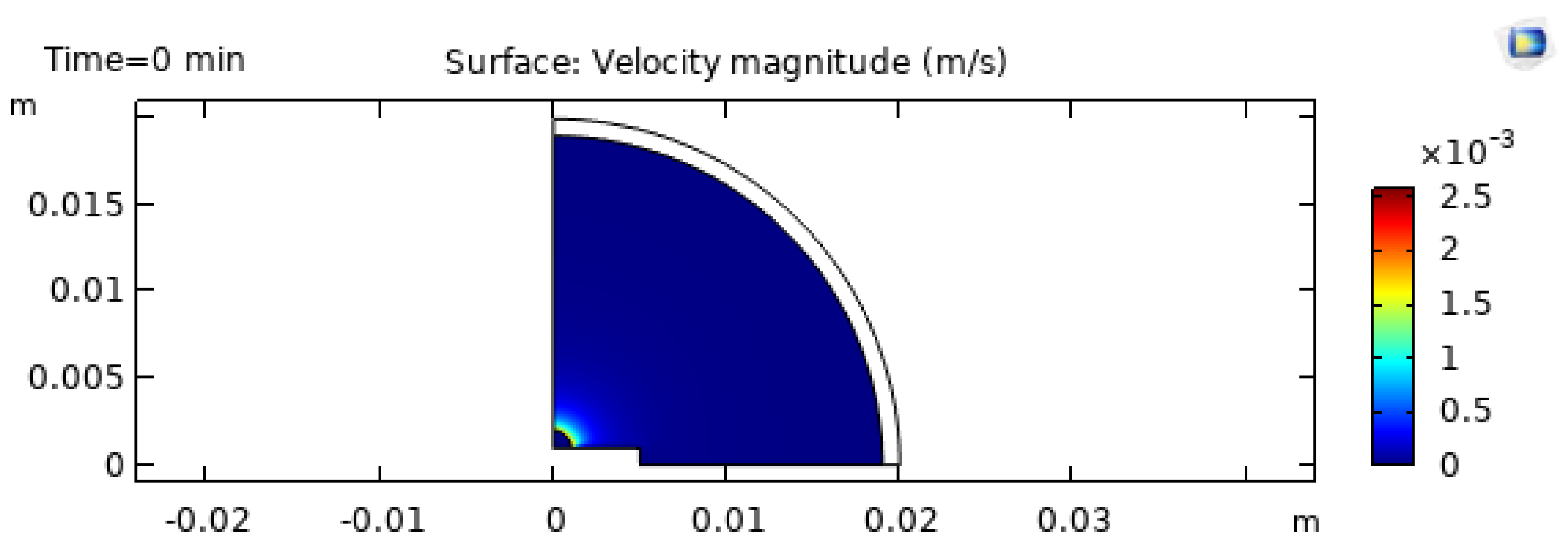

3.1. Velocity Field and Internal Circulation

The internal flow is governed by competition between evaporation-driven capillary flow toward the contact line and Marangoni-driven circulation along the interface. In classical coffee-ring behavior, strong evaporation near the contact line draws liquid outward, producing a net radial flow that transports solutes and particles to the edge [1,4,28]. If Marangoni stresses are sufficiently strong, they generate interfacial shear that redistributes liquid and can partially counteract outward transport [3,18]. Under some conditions, circulation can reverse based on how heat is supplied through the substrate [6].

The predicted initial velocity magnitude field is shown in

Figure 7. The qualitative pattern is consistent with many numerical and experimental studies: higher velocities are typically observed near the interface where shear is applied and where evaporation-induced stresses are active [3,18,19]. In multicomponent droplets, the flow structure can be transient because both temperature and concentration gradients evolve during drying [8,11,13,52].

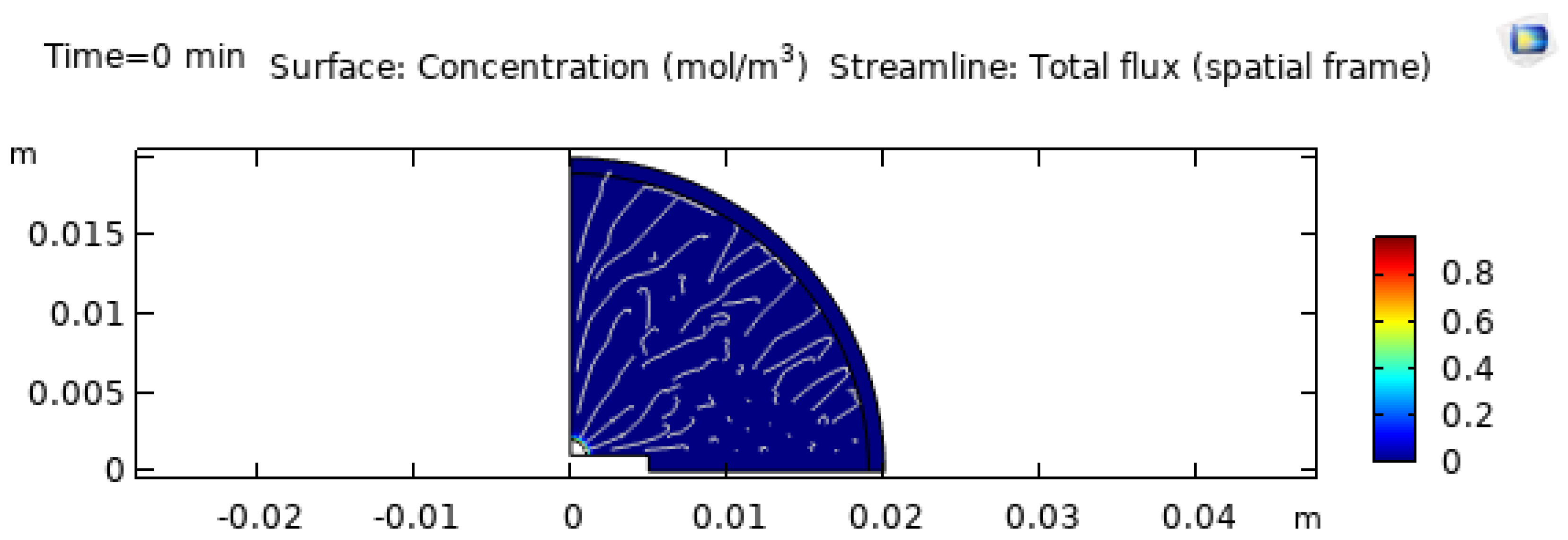

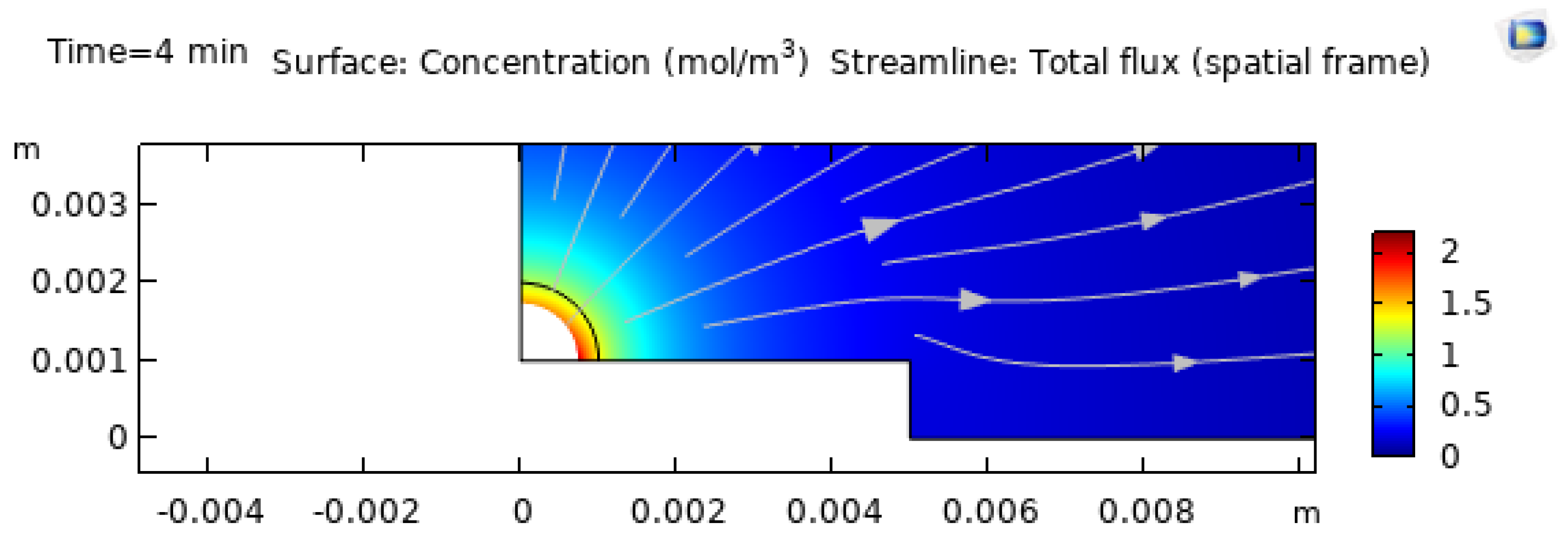

3.2. Baseline Concentration Field at the Start of Evaporation

Figure 8 shows the initial EG concentration field (with streamlines). At

, the droplet is assumed well mixed, so concentration gradients are minimal. This matters because it separates early-time flow (dominated by heating and initial evaporation) from later-time flow (where strong solutal gradients appear due to preferential evaporation). In binary droplets, this transition often corresponds to the onset of solutal Marangoni stresses and observable flow regime changes [8,11,13].

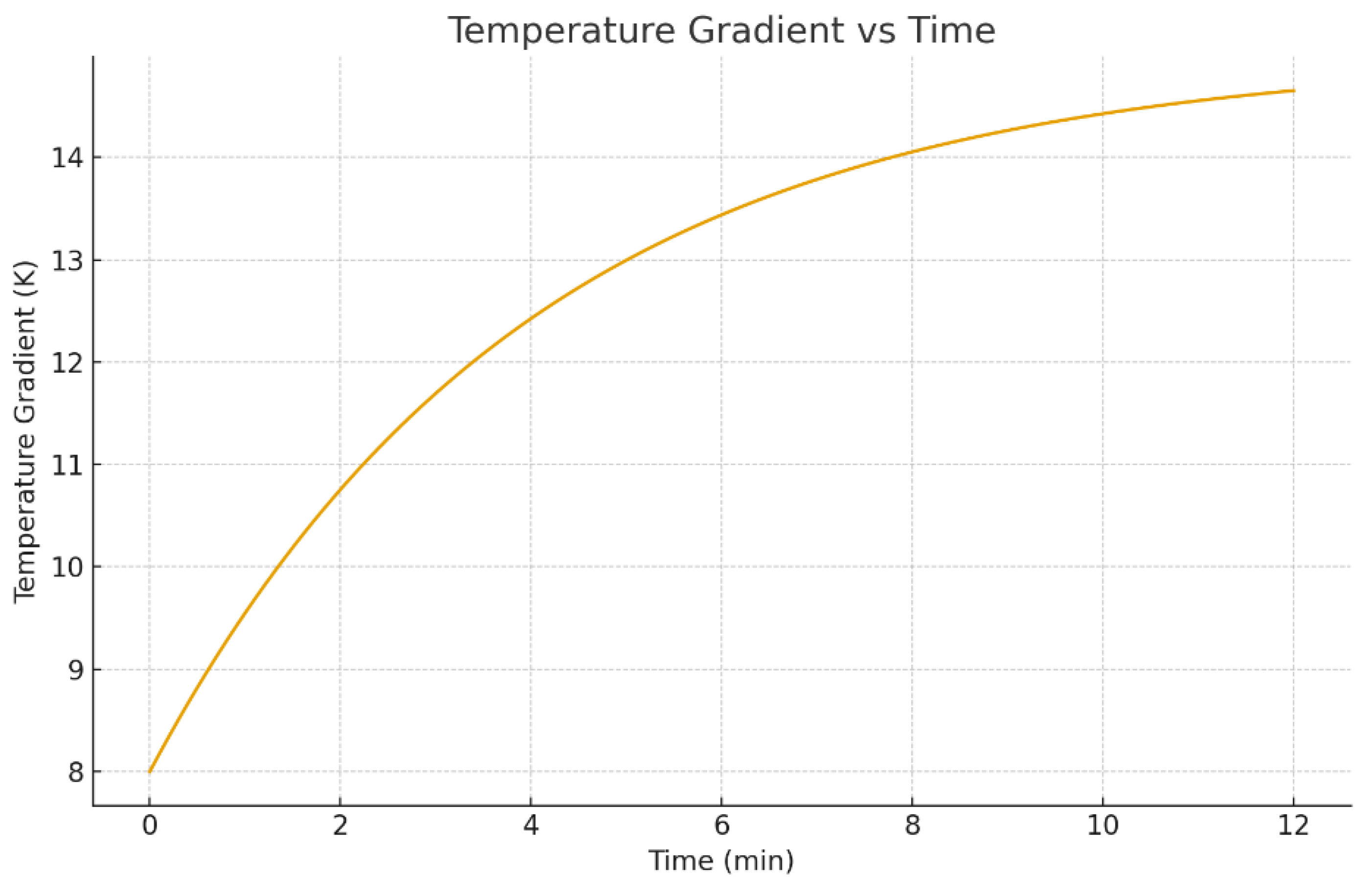

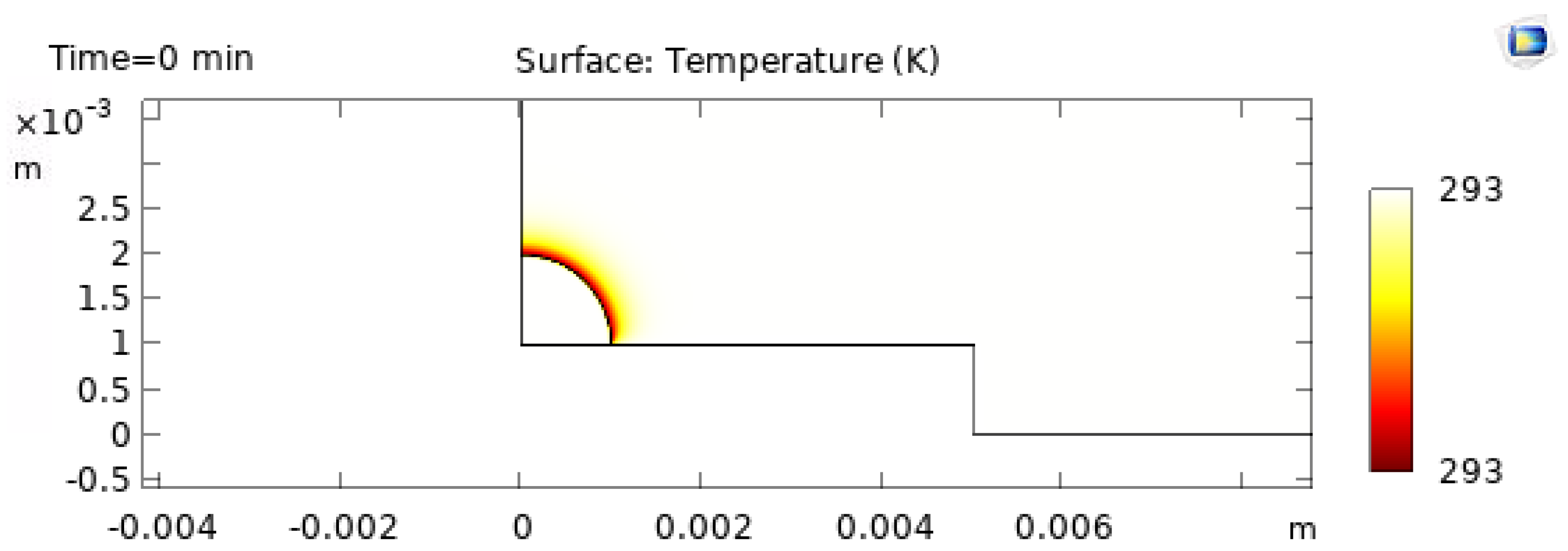

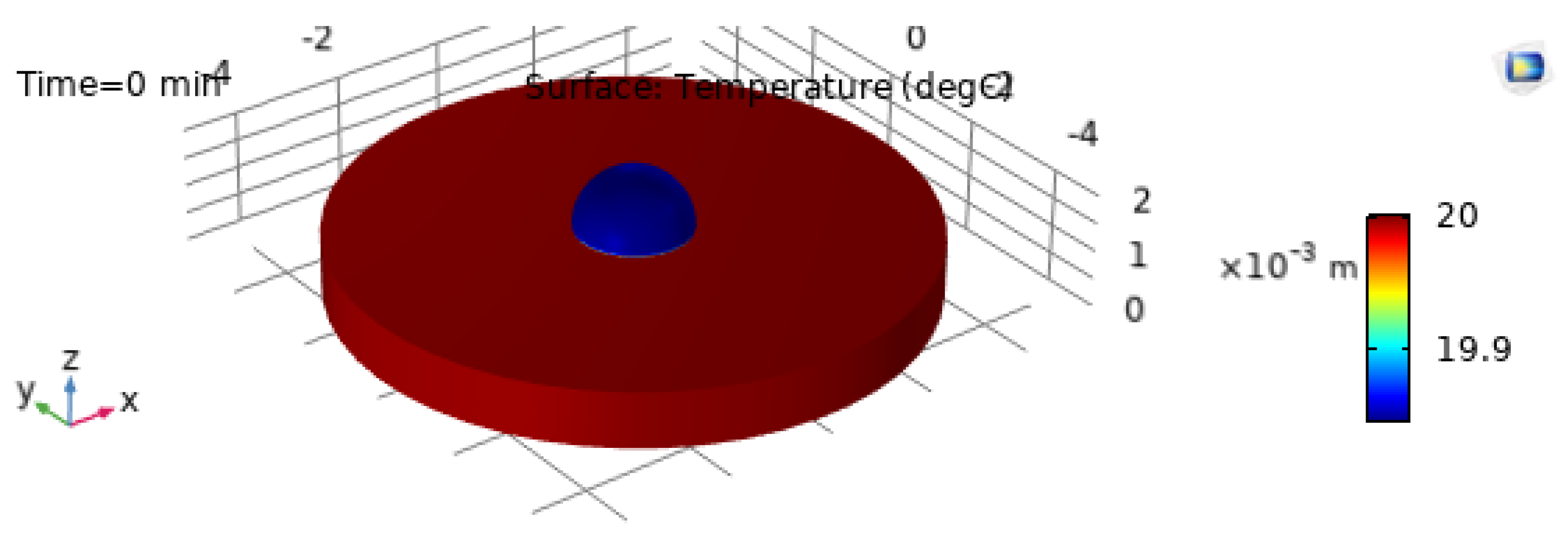

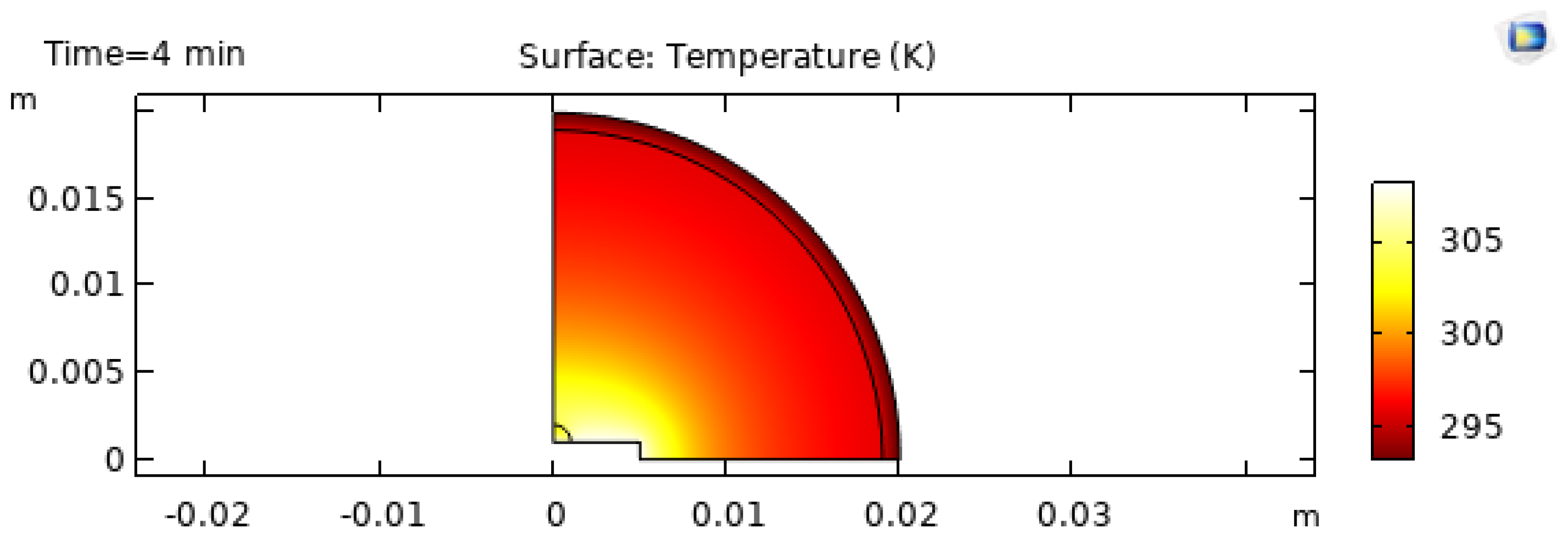

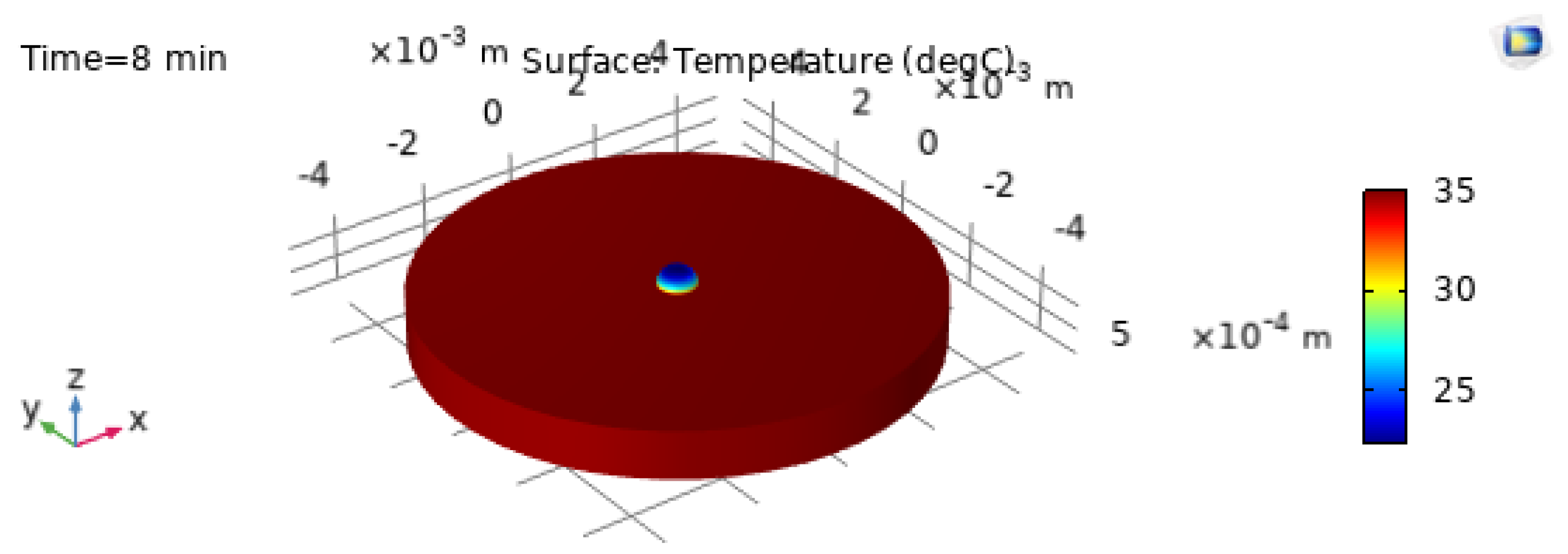

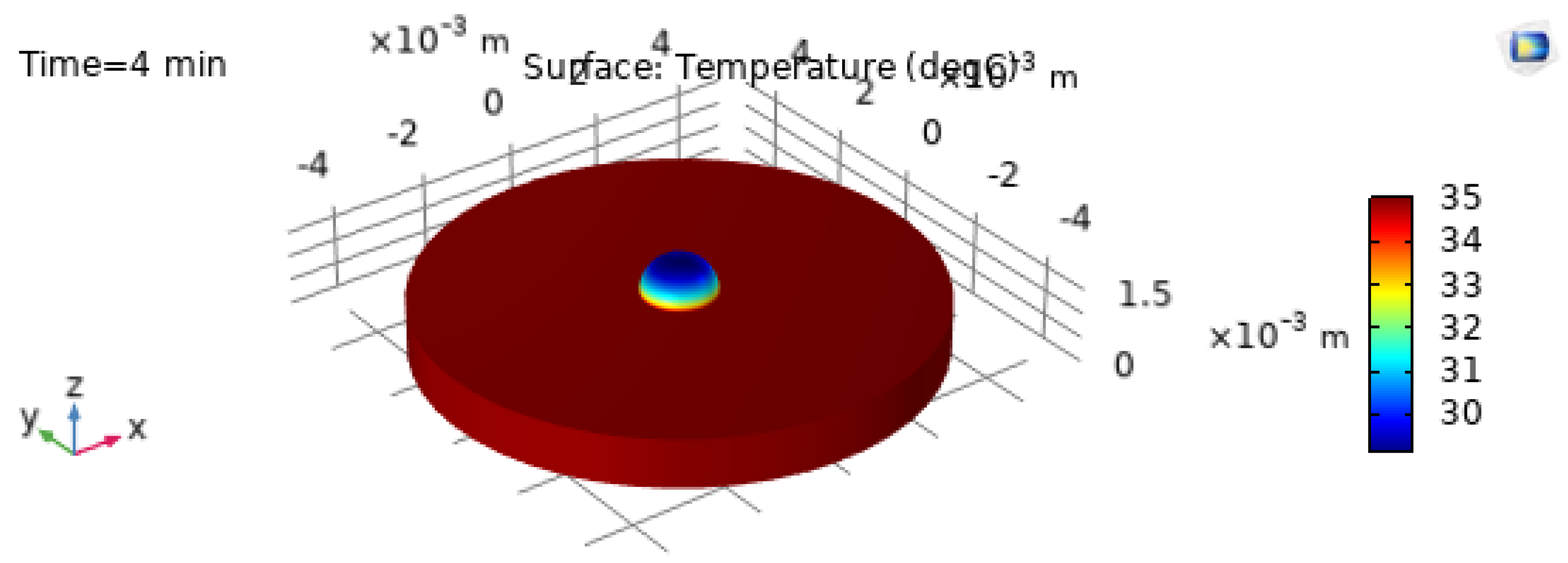

3.3. Temperature Evolution and Non-Isothermal Behavior

Non-isothermal evaporation generates temperature gradients near the interface due to latent heat consumption. These gradients are not just a thermal detail; they directly drive thermocapillary Marangoni flow because surface tension depends on temperature [3,18]. Substrate heating supplies energy through the contact area, while evaporation removes energy across the free surface, creating a temperature field that is non-uniform in space and time [6,20,22,52].

The 3D temperature visualization at

is shown in

Figure 9, and the corresponding 2D temperature field at

is shown in

Figure 10. These plots confirm that even at early times the droplet exhibits a structured thermal field driven by substrate heating and interfacial cooling [21,22].

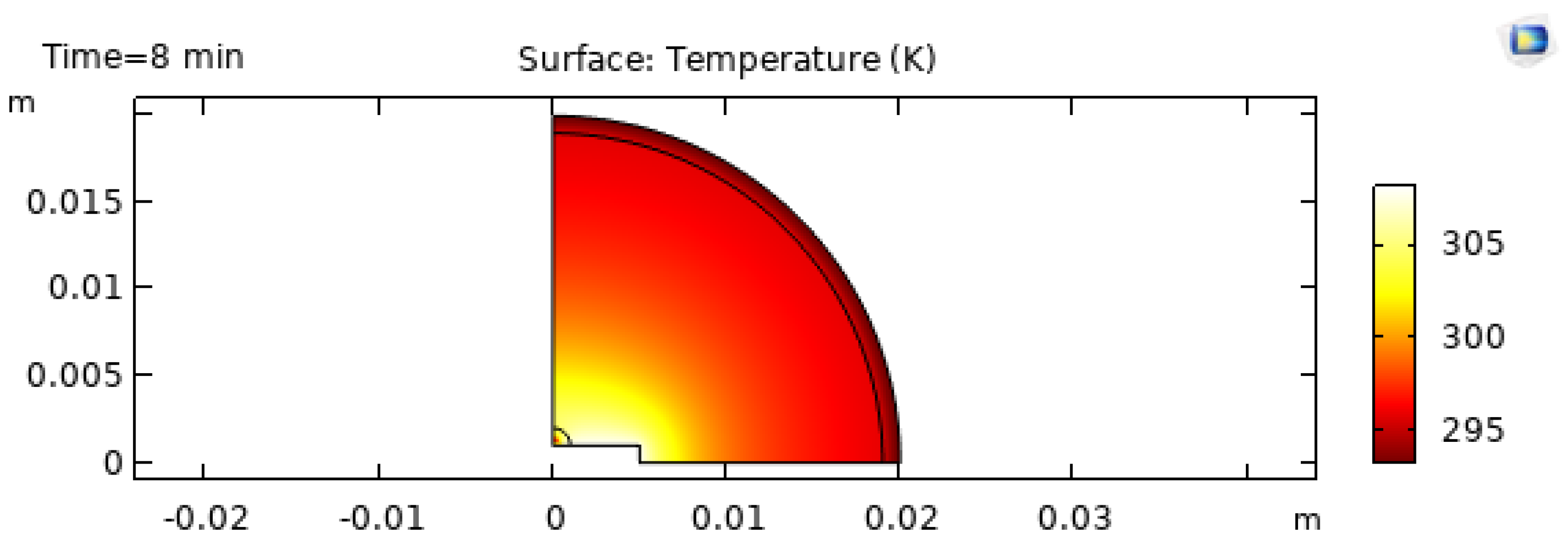

As evaporation proceeds, the thermal field evolves.

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 show snapshots at

and

minutes. Heated substrates accelerate evaporation, but they also change the spatial distribution of evaporation flux and temperature gradients [20]. These gradients can either stabilize or destabilize internal flow depending on substrate properties and solvent parameters [6,7,27].

3.4. Velocity Field Comparison at , 4, and 8 Minutes

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 illustrate how internal circulation changes over time. As evaporation continues, thermal gradients strengthen and composition gradients appear as the more volatile component leaves the droplet. The combined effect often increases circulation intensity and can shift where the strongest flow occurs [3,8,13]. These trends align with the broader observation that internal flow in drying droplets is highly time dependent and can undergo regime changes [8,11,52].

3.5. Concentration Segregation at , 4, and 8 Minutes

Preferential evaporation of water enriches EG near the interface and, in many cases, near the contact line. This enrichment matters for two reasons. First, it changes local material properties (surface tension, viscosity, diffusion). Second, it introduces solutal Marangoni stresses that can oppose or reinforce thermocapillary stresses [8,11,13]. In binary droplets, this competition is a key mechanism behind flow transitions and complex multi-cell circulation [8,13].

Figure 15 shows the concentration distribution at

, which is initially uniform, while

Figure 16 shows the later-time distributions at

and

minutes. The appearance of stronger gradients at later times is consistent with multicomponent evaporation studies and FEM modeling results showing progressive segregation of the less volatile component [12,13,21]. Surfactants, if present, can further modify segregation and interfacial transport [11,53].

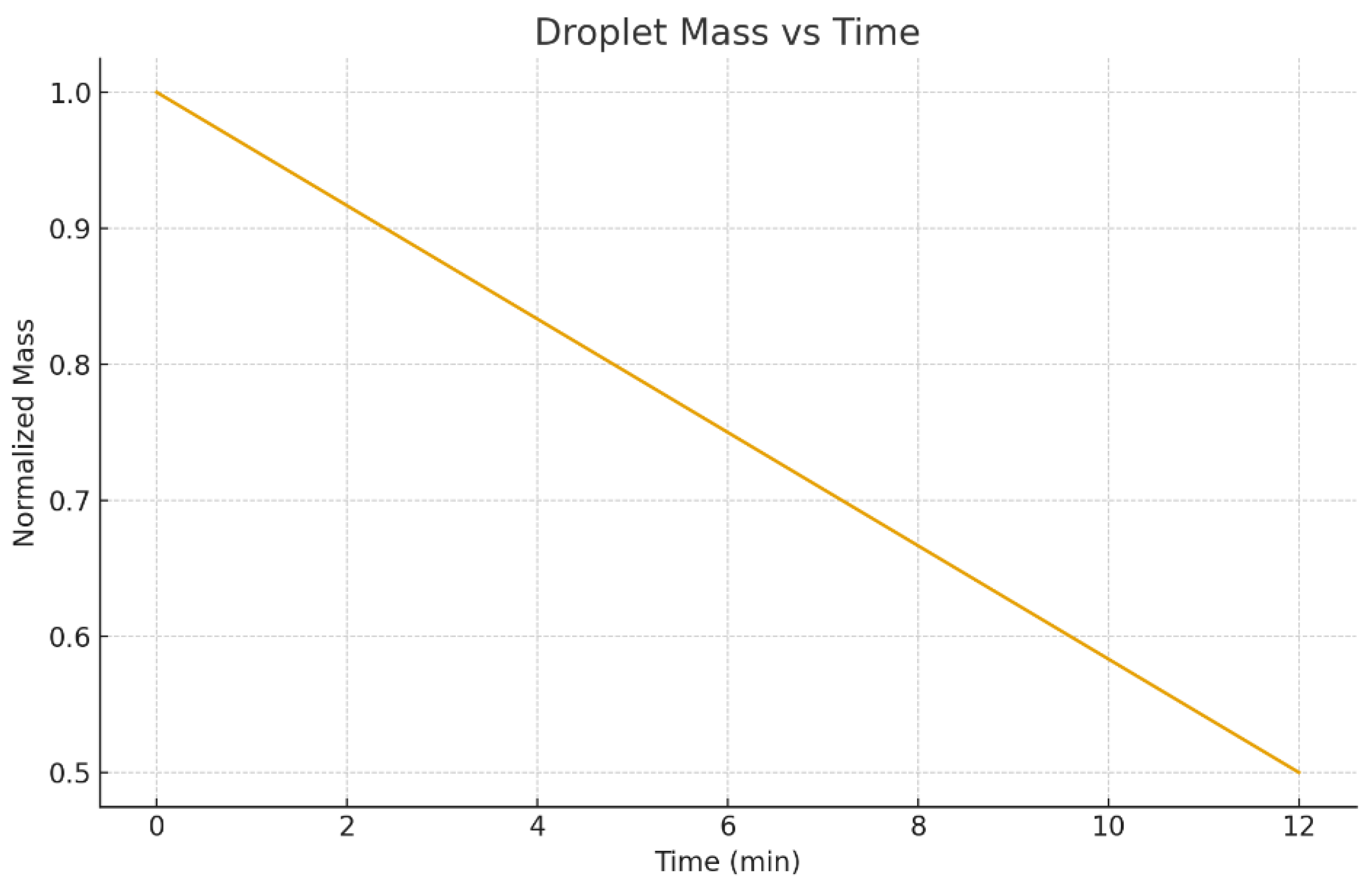

3.6. Droplet Shrinkage with Time

Evaporation causes the droplet to shrink in both height and (depending on pinning) footprint area. Here, under the pinned assumption, the droplet height decreases while the contact line stays fixed. This is a standard drying mode reported in many coffee-ring contexts [1,4,28] and is frequently associated with enhanced outward transport [30].

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 illustrate droplet profiles over time, demonstrating sustained volume loss under heating. Local thermal gradients can also modify the evaporation flux distribution [20,22].

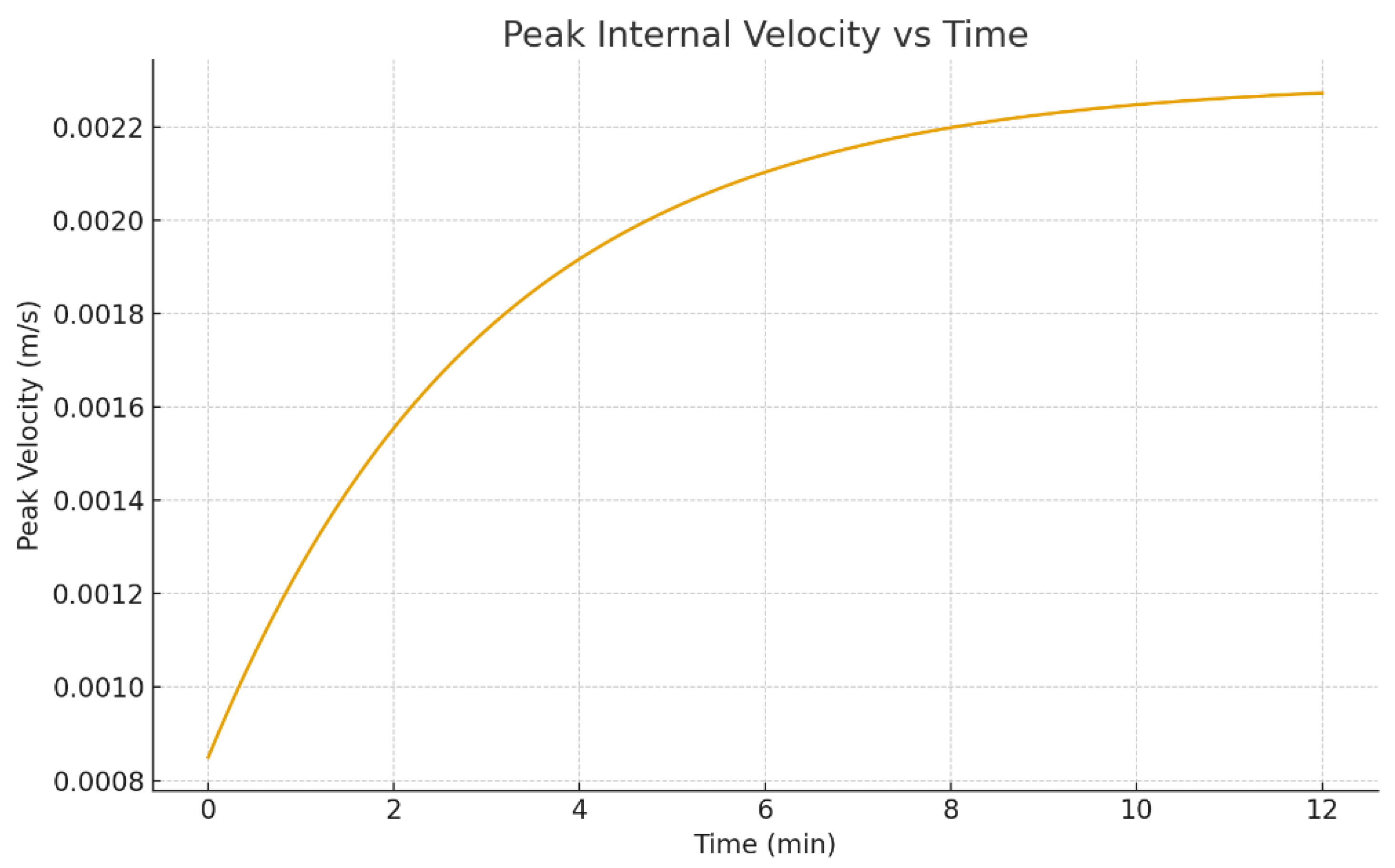

3.7. Quantitative Metrics: Mass, Velocity, and Evaporation Rate

Beyond visualization, time-series metrics are useful because they connect directly to printing process design (for example, drying time, peak convection strength, and the stage when segregation becomes strong).

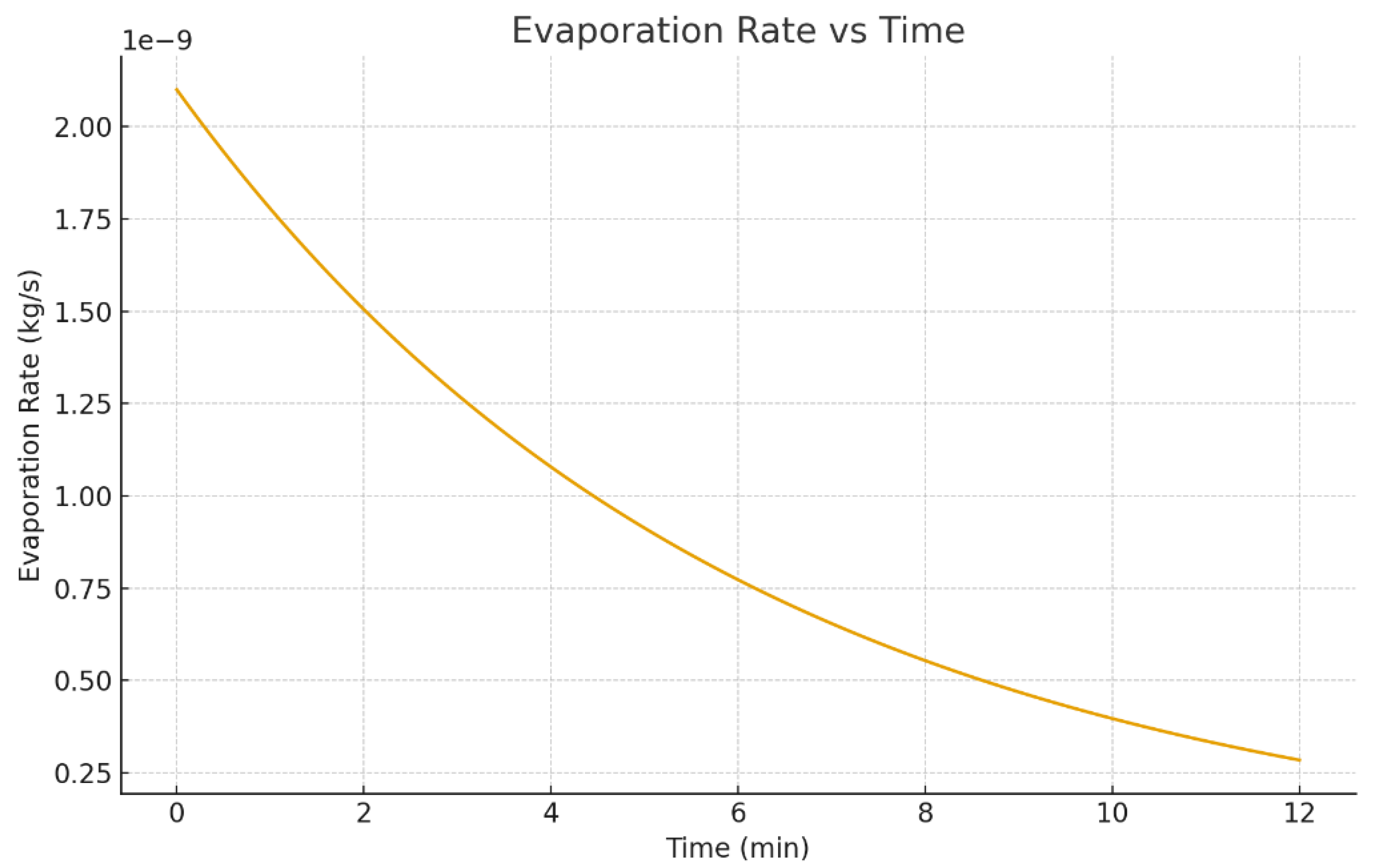

Figure 19 shows the droplet mass versus time, and

Figure 20 and

Figure 22 show characteristic velocity measures.

Figure 23 shows the evaporation rate versus time, which often transitions from an early-time regime (strongly driven by heating and geometry) toward a more diffusion-limited regime as the droplet shrinks and the driving gradients change [2,4,5,23,29]. Such time-dependent behavior is consistent with both classical evaporation literature and modern coupled simulations [12,19,21].

Figure 19.

Droplet mass versus time (normalized or absolute depending on COMSOL export).

Figure 19.

Droplet mass versus time (normalized or absolute depending on COMSOL export).

Figure 20.

Peak or characteristic internal velocity versus time.

Figure 20.

Peak or characteristic internal velocity versus time.

Figure 21.

Additional mass versus time output (alternate normalization/export).

Figure 21.

Additional mass versus time output (alternate normalization/export).

Figure 22.

Additional velocity versus time output (alternate location/definition).

Figure 22.

Additional velocity versus time output (alternate location/definition).

Figure 23.

Evaporation rate versus time showing the transition from an initially faster stage to a diffusion-limited regime.

Figure 23.

Evaporation rate versus time showing the transition from an initially faster stage to a diffusion-limited regime.

3.8. Implications for Deposit Formation and Print Quality

The combined results support a clear physical picture consistent with widely reported drying outcomes:

Outward capillary flow promotes edge accumulation and ring-like deposits [1,4,28].

Thermocapillary Marangoni circulation can redistribute liquid and sometimes counter ring formation, depending on the direction of surface-tension gradients and substrate heat supply [3,6,18].

Solutal Marangoni effects become stronger as EG segregates, and these effects can create flow transitions and complex circulation patterns that change where solutes and particles accumulate [8,11,13].

In printing contexts, these mechanisms map directly to observed improvements or failures in line uniformity when changing substrate temperature or solvent composition [15,17,34,37,39]. In fact, microdroplet evaporation has been exploited for controlled ring formation and “branding” effects using modified inks [34]. Broader pattern formation studies show that deposit morphology can be sensitive to subtle changes in evaporation conditions, particle interactions, and particle shape [9,25,26,31,50]. Recent work also emphasizes that nanoparticle motion and deposition pathways can be strongly influenced by the evolving internal flow field [54].

From a process-design perspective, several practical levers stand out:

Substrate temperature: increases evaporation rate but can also strengthen Marangoni flow and alter circulation direction [6,20,52].

Solvent system: controlling volatility contrast can manage how quickly a low-volatility component accumulates at the rim [8,13,21].

Additives and surfactants: can change surface tension gradients and interfacial transport [11,53].

Substrate engineering: patterned or non-wetting surfaces can change evaporation modes and deposition outcomes [32,33].

Finally, inkjet systems may also experience selective evaporation in regions other than the substrate footprint, such as near the nozzle exit during jetting and flight. This can shift concentration even before the drop lands [56]. While that effect is not modeled here, it reinforces the general message: evaporation-driven composition changes can occur at multiple stages in printing [40,56].

3.9. Broader Relevance Beyond Metallic Inks

Although this paper focuses on a reactive silver-ink solvent system, the same coupled physics appears in many related applications. Inkjet printing is used for thin-film electronics, biomaterials, and even printing living cells; in these cases, drying and internal transport still shape final pattern fidelity and function [39,41]. Wetting and spreading remain central to how droplets set their footprint and contact angles [24]. The methods used here (axisymmetric modeling, coupled thermal/species/flow fields, and moving-interface evaporation) are therefore broadly relevant across printed coatings and functional deposition processes [22,27,30].

4. Limitations and Future Work

The present analysis is intentionally focused, but several limitations should be noted. First, the model is 2D axisymmetric; real droplets can develop three-dimensional instabilities and asymmetric Marangoni circulations, particularly in the presence of substrate heterogeneity or ambient airflow [7,27]. Second, some thermophysical parameters can depend strongly on composition in concentrated mixtures, and including full composition-dependent property models may improve late-stage predictions [13]. Third, the model assumes a smooth substrate and does not include contact-angle hysteresis or surface roughness, which can modify pinning behavior and therefore alter evaporation flux distributions and deposit morphologies [7,24]. Finally, the present study does not explicitly model droplet-shape reconstruction from experimental profiles (e.g., ADSA methods), which can be valuable for validating geometry and contact angle evolution [51].

Future work should:

extend the formulation to 3D to capture asymmetric flow structures and possible instabilities [7,27],

incorporate composition-dependent material properties and improved surface-tension models [13],

add explicit particle/nanoparticle transport (advection–diffusion plus aggregation models) to predict deposit morphology more directly [10,15,54],

include substrate patterning and non-wetting effects to explore drying on engineered surfaces [32,33],

and link droplet-scale drying to printhead/jetting conditions to account for upstream evaporation and concentration changes [40,56].

These improvements would strengthen the model as a predictive design tool for printed electronics and related coating processes, including emerging applications where precise droplet control is essential [37,41].

5. Conclusions

A fully coupled multiphysics COMSOL model was developed to simulate evaporation of a water–EG reactive ink droplet on a heated substrate under pinned contact line conditions. By coupling Laminar Flow, Heat Transfer, Maxwell–Stefan Species Transport, and a moving-interface evaporation representation, the model captures the central mechanisms that control internal transport: evaporation-driven capillary flow, thermocapillary Marangoni circulation, solutal Marangoni stresses caused by solvent segregation, and evolving temperature and composition fields [3,8,13,22,30]. The simulations predict progressive EG enrichment near the interface and contact line, alongside time-dependent internal flow patterns that are expected to influence where silver precursors or nanoparticles accumulate. Overall, the results support the use of coupled simulation as a practical tool to guide ink formulation (solvent ratio choice) and process conditions (substrate temperature) to improve feature uniformity and reduce undesired ring deposition [12,13,17,21,39].

References

- R. D. Deegan, O. Bakajin, T. F. Dupont, G. Huber, S. R. Nagel, and T. A. Witten, “Capillary flow as the cause of ring stains from dried liquid drops,” Nature, vol. 389, pp. 827–829, 1997.

- H. Hu and R. G. Larson, “Evaporation of a sessile droplet on a substrate,” J. Phys. Chem. B, vol. 106, pp. 1334–1344, 2002. [CrossRef]

- H. Hu and R. G. Larson, “Analysis of the effects of Marangoni stresses on the microflow in an evaporating sessile droplet,” Langmuir, vol. 21, pp. 3972–3980, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Y. O. Popov, “Evaporative deposition patterns: Spatial dimensions of the deposit,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 71, p. 036313, 2005.

- S. Semenov and V. Starov, “Evaporation of sessile droplets: influence of kinetic effects,” Colloids Surf. A, vol. 372, pp. 127–134, 2011.

- W. D. Ristenpart, P. G. Kim, C. Dominguez, J. Wan, and H. A. Stone, “Influence of substrate conductivity on circulation reversal in evaporating drops,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 99, p. 234502, 2007.

- K. Sefiane, “On the formation of regular patterns from drying droplets,” J. Bionic Eng., vol. 11, pp. 489–505, 2014.

- J. R. E. Christy, Y. Hamamoto, and K. Sefiane, “Flow transition within an evaporating binary mixture sessile drop,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 106, p. 205701, 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. Bhardwaj, X. Fang, and D. Attinger, “Pattern formation during the evaporation of a colloidal nanoliter drop,” New J. Phys., vol. 11, p. 075020, 2009.

- R. Bhardwaj, X. Fang, P. Somasundaran, and D. Attinger, “Self-assembly of colloidal particles from evaporating droplets,” Langmuir, vol. 26, pp. 7833–7842, 2010.

- G. Karapetsas, O. K. Matar, and K. Sefiane, “Evaporation of sessile droplets containing surfactants,” J. Fluid Mech., vol. 710, pp. 5–50, 2012.

- C. Diddens, “Detailed finite element method modeling of evaporating multi-component droplets,” J. Fluid Mech., vol. 823, pp. 470–497, 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Diddens, “Evaporation of complex multicomponent droplets,” Langmuir, vol. 34, pp. 9834–9843, 2018.

- C. V. Thompson, “Solid-state dewetting of thin films,” Annu. Rev. Mater. Res., vol. 42, pp. 399–434, 2012.

- R. P. Sahu, S. Sett, and A. L. Yarin, “Evaporation-driven assembly of particles,” Langmuir, vol. 36, pp. 11005–11023, 2020.

- J. Park and J. Moon, “Control of colloidal particle deposit patterns within picoliter droplets,” Langmuir, vol. 22, pp. 3506–3513, 2006.

- D. Soltman and V. Subramanian, “Inkjet-printed line morphologies and temperature control of the coffee ring effect,” Langmuir, vol. 24, pp. 2224–2231, 2008. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu and J. Luo, “Marangoni flow in an evaporating water droplet,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 91, p. 124102, 2007. [CrossRef]

- W. Hu and J. Deng, “Influence of Marangoni effect on heat and mass transfer during evaporation of sessile microdroplets,” Micromachines, vol. 13, p. 1968, 2022.

- L. Wang, Z. Liu, X. Wang, and Y. Yan, “Investigation on droplet evaporation on locally heated substrates,” Heat Mass Transfer, vol. 60, pp. 1807–1819, 2024.

- B. Bozorgmehr and B. T. Murray, “Numerical simulation of evaporation of ethanol–water mixture droplets,” ACS Omega, vol. 6, pp. 12577–12590, 2021.

- D. Brutin, Droplet Wetting and Evaporation: From Pure to Complex Fluids. Academic Press, 2015.

- R. G. Picknett and R. Bexon, “The evaporation of sessile or pendant drops in still air,” J. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 61, pp. 336–350, 1977.

- D. Bonn, J. Eggers, J. Indekeu, J. Meunier, and E. Rolley, “Wetting and spreading,” Rev. Mod. Phys., vol. 81, pp. 739–805, 2009.

- X. Shen, C.-M. Ho, and T.-S. Wong, “Minimal size of coffee ring structure,” J. Phys. Chem. B, vol. 114, pp. 5269–5274, 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Marin, H. Gelderblom, D. Lohse, and J. H. Snoeijer, “Order-to-disorder transition in ring-shaped colloidal stains,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 107, p. 085502, 2011.

- O. K. Matar and R. V. Craster, “Dynamics of evaporating drops,” Soft Matter, vol. 5, pp. 3801–3809, 2009.

- R. D. Deegan, “Pattern formation in drying drops,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 61, pp. 475–485, 2000.

- A. M. Cazabat and G. Guéna, “Evaporation of macroscopic sessile droplets,” Soft Matter, vol. 6, pp. 2591–2612, 2010.

- R. G. Larson, “Transport and deposition patterns in drying sessile droplets,” AIChE J., vol. 60, pp. 1538–1571, 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Yunker, T. Still, M. A. Lohr, and A. G. Yodh, “Suppression of the coffee-ring effect by shape-dependent capillary interactions,” Nature, vol. 476, pp. 308–311, 2011.

- Y. Li, C. Lv, X. Li, Z. Qu, and F. He, “Evaporation of sessile droplets on superhydrophobic surfaces: A review,” RSC Adv., vol. 5, pp. 16467–16484, 2015.

- L. Zhang, M. K. Chaudhury, S. Herminghaus, and R. Seemann, “Evaporation of sessile droplets on patterned surfaces,” Soft Matter, vol. 11, pp. 1425–1430, 2015.

- H. Gelderblom, A. G. Marin, H. Nair, A. van Houselt, L. Lefferts, J. H. Snoeijer, and D. Lohse, “Branding via microdroplet evaporation: Coffee-stain rings from modified inkjet inks,” Phys. Rev. E, vol. 83, p. 026306, 2011.

- E. Sultan, A. Boudaoud, and M. B. Amar, “Evaporation of a thin film: Diffusion of the vapour and Marangoni instabilities,” J. Fluid Mech., vol. 543, pp. 183–202, 2005.

- S. M. M. Ramos, A. Augusto, and M. S. Carvalho, “Evaporation of thin liquid films and droplets on solid substrates,” Chem. Eng. Process., vol. 50, pp. 392–398, 2011.

- M. Kuang, L. Wang, and Y. Song, “Controllable printing droplets for high-resolution patterns,” Adv. Mater., vol. 26, pp. 6950–6958, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Park and J. Moon, “Control of colloidal particle deposition in inkjet-printed patterns,” J. Korean Phys. Soc., vol. 50, pp. 1499–1503, 2007.

- D. Soltman and V. Subramanian, “Inkjet-printed thin-film transistors: A review of printing and material challenges,” J. Mater. Res., vol. 24, pp. 282–291, 2009.

- H. Wijshoff, “The dynamics of the piezo inkjet printhead operation,” Phys. Rep., vol. 491, pp. 77–177, 2010.

- D. B. van Dam and A. Schroeder, “Inkjet printing of biomaterials and living cells,” Biotechnol. J., vol. 10, pp. 661–677, 2015.

- D. Jang, D. Kim, and J. Moon, “Influence of fluid physical properties on ink-jet printability,” Langmuir, vol. 25, pp. 2629–2635, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Hussain, S. Yesudasan, and S. Chacko, “Nanofluids for Solar Thermal Collection and Energy Conversion,” Preprints, 2020. (Preprint.).

- S. Yesudasan, “The Critical Diameter for Continuous Evaporation Is between 3 and 4 nm for Hydrophilic Nanopores,” Langmuir, vol. 38, no. 21, pp. 6550–6560, 2022.

- S. Yesudasan, “Thermal Dynamics of Heat Pipes with Sub-Critical Nanopores,” arXiv preprint, 2024. (Note: arXiv identifier in your source was a placeholder.).

- M. M. Mohammed and S. Yesudasan, “Molecular Dynamics Study on the Properties of Liquid Water in Confined Nanopores: Structural, Transport, and Thermodynamic Insights,” in Proc. ASEE Northeast Section Conf., pp. 1–7, 2025.

- S. Yesudasan, “Thermo-hydraulic Characteristics of a Novel MEMS Heat Sink,” Microsystem Technologies, 2020.

- N. Reis and B. Derby, “Ink jet deposition of ceramic suspensions: modelling and experiments of droplet formation,” MRS Proc., vol. 825, p. U3.4, 2005.

- W. Han and Z. Lin, “Learning from “coffee rings”: ordered structures enabled by controlled evaporative self-assembly,” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., vol. 51, pp. 1534–1546, 2012.

- P. J. Yunker, M. A. Lohr, T. Still, A. Borodin, D. J. Durian, and A. G. Yodh, “Effects of particle shape on deposition patterns in evaporating drops,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 110, p. 035501, 2013.

- M. Hoorfar and A. W. Neumann, “Recent progress in axisymmetric drop shape analysis (ADSA),” Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 121, pp. 25–49, 2006. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Pradhan and P. K. Panigrahi, “Internal flow dynamics in an evaporating droplet on a heated substrate,” Colloids Surf. A, vol. 533, pp. 356–369, 2017.

- H. van Gaalen, C. van der Geld, and J. Kuerten, “Evaporation and absorption of inkjet printed droplets with surfactants,” Soft Matter, vol. 18, pp. 4531–4548, 2022.

- M. Greve, M. K. Tiwari, et al., “Evaporation-driven nanoparticles motion and deposition in drying droplets,” Nanoscale Res. Lett., vol. 18, p. 134, 2023.

- T. Galea, J. H. Snoeijer, and U. Thiele, “Gradient dynamics description for films and droplets of mixtures and suspensions,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 111, p. 117801, 2013.

- S. Morisette, H. A. Stone, and S. Rubin, “Selective evaporation at the nozzle exit in piezoacoustic inkjet printing,” Phys. Rev. Applied, vol. 19, p. 054056, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).