Submitted:

26 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

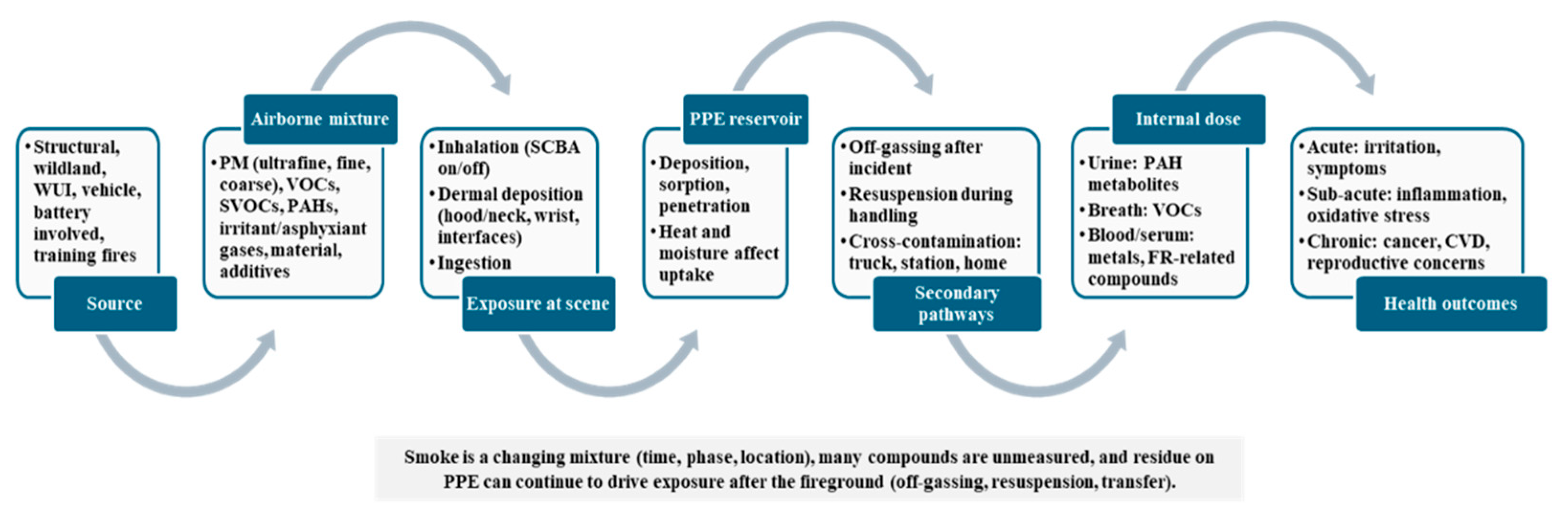

2. Firefighters’ Exposure Environments

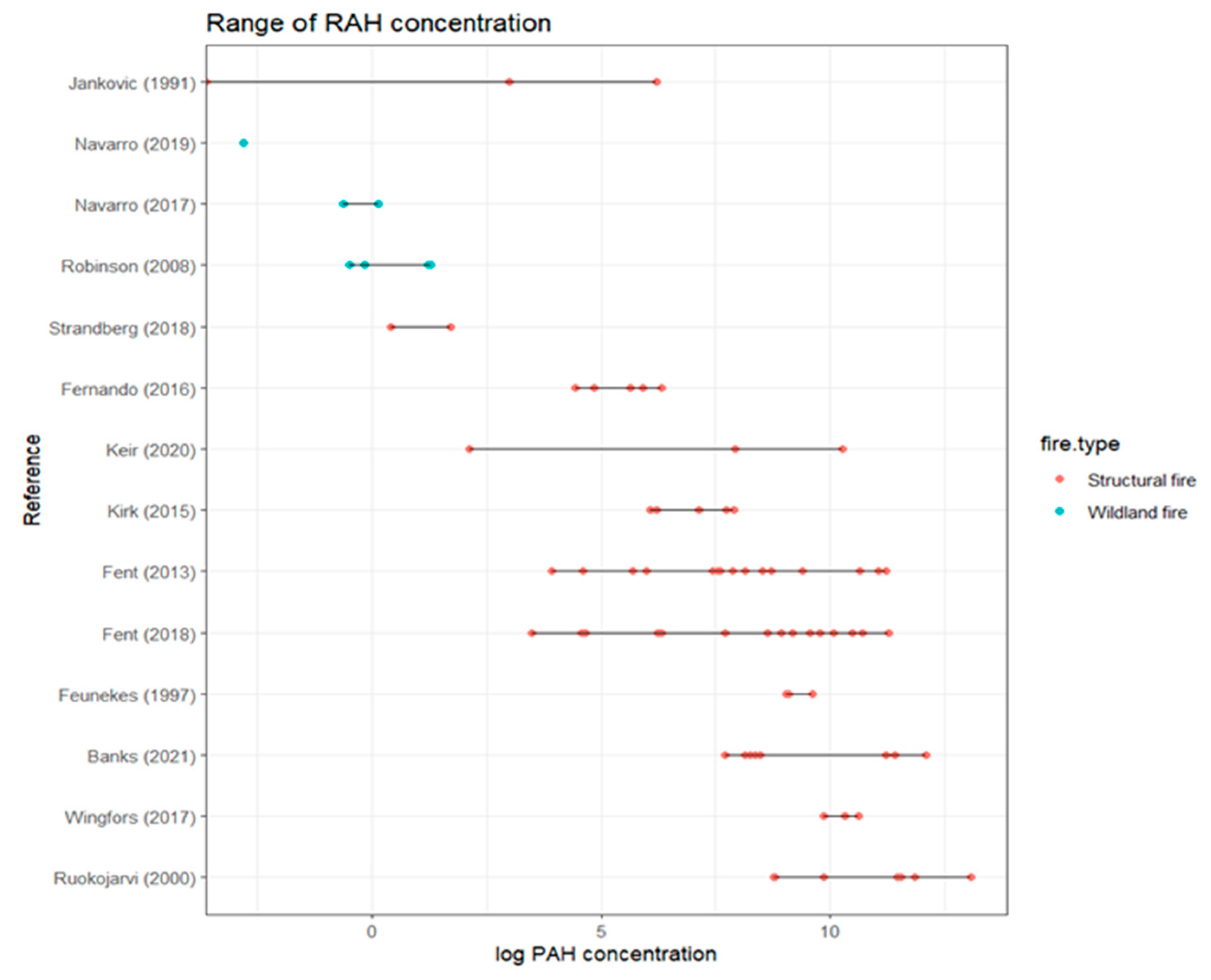

2.1. Firefighters’ Exposure Across Fire Incident Types

2.2. Firefighters’ Exposure to PFAS

2.3. Routes of Exposure of Firefighters

2.4. Methods for Characterizing Exposure Environments

2.5. Research Platforms and Methods for Quantifying Firefighters’ Exposure Environments

2.5.1. Field Deployment Studies in Real Incidents and Training Fires

2.5.2. Large Scale Exposure Simulators for Repeatability and Intervention Testing

2.5.3. Lab-Based Small Scale Combustion and Smoke Simulator

2.6. Synthesis of Research Gaps and Priorities

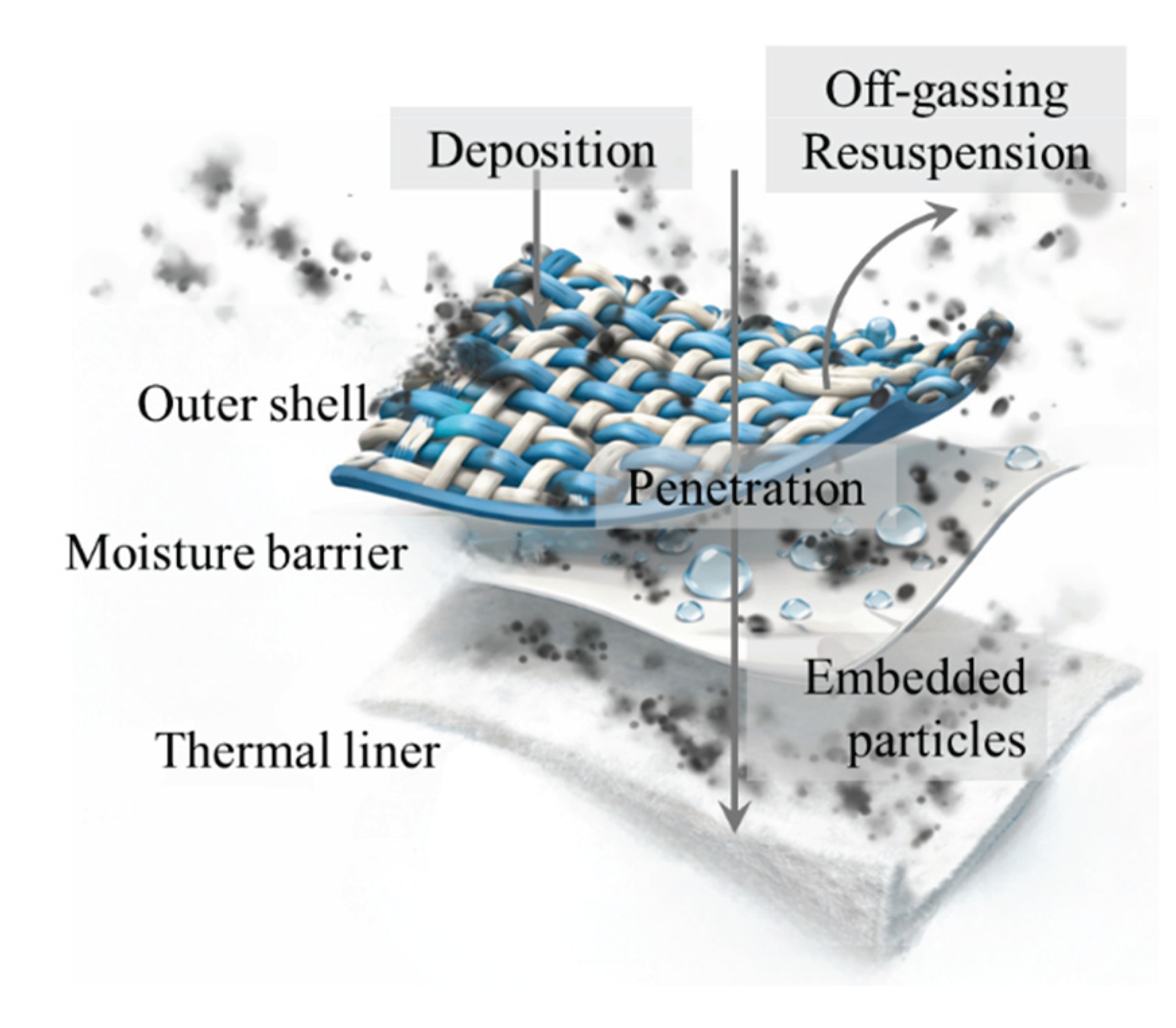

3. Firefighter PPE Contamination

3.1. Contaminant Deposition, Sorption, and Penetration

3.2. Contaminant Off-Gassing and Resuspension

3.3. Contamination Simulation and Studies

3.3.1. Methods to Simulate and Characterize PPE Contamination

3.3.2. Methods to Characterize Contaminant Deposition and Penetration

4. Firefighter PPE Decontamination

4.1. Decontamination Processes, Methods, and Issues

4.2. Secondary Emissions and Cross-Contamination as Part of the Decontamination Problem

4.3. Aging, Repeated Contamination Cycles, and the Missing Longitudinal Evidence

4.4. Effect of Decontamination on PPE Performance

4.5. Cleaning Efficacy Definition: How Clean Is Clean?

4.6. Methodological Gaps and Research Priorities for PPE Decontamination

5. Health Outcome and Biological Evidence Associated with Firefighting Smoke Exposure

5.1. Cancer and Long-Latency Outcomes

5.2. Cardiovascular and Cardiometabolic Outcomes

5.3. Respiratory, Immune, and Other Non-Cancer Outcomes

5.4. Biomarkers and Mechanistic Evidence

5.5. Key Research Gaps and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VOCs | Volatile organic compounds |

| BTEXs | Benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes |

| PAHs | Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| PFAS | Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| DEHP | Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) phthalate |

| AFFF | Aqueous film-forming foam |

| WUI | Wildland-urban interface |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

| SCBA | Self-contained breathing apparatus |

| IARC | International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| IAFF | International Association of Fire Fighters |

| NFPA | National Fire Protection Association |

| EVs | Electric vehicles |

| ECHA | European chemical agency |

References

- Quintela, D., et al., Working conditions of firefighters: Physiological measurements, subjective assessments and thermal insulation of protective clothing. Occupational Safety and Hygiene; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013: p. 521-526.

- Willi, J.M., G.P. Horn, and D. Madrzykowski, Characterizing a firefighter’s immediate thermal environment in live-fire training scenarios. Fire Technology, 2016. 52(6): p. 1667-1696.

- Navarro, K.M., et al., Wildland firefighter smoke exposure and risk of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality. Environmental Research, 2019. 173: p. 462-468. [CrossRef]

- Demers, P.A., et al., Carcinogenicity of occupational exposure as a firefighter. The Lancet Oncology, 2022. 23(8): p. 985-986.

- Rita Fahy, B.E.a.G.P.S., Us fire department profile 2020. 2022.

- Hall, S. and B. Evarts, Fire loss in the united states during 2021. 2022, National Fire Protection Association (NFPA).

- Fahy, R.F. and J.T. Petrillo, Firefighter fatalities in the us in 2020. 2021, NFPA.

- Campbell, R. and S. Hall, United states firefighter injuries in 2022. 2023, NFPA. https://www.nfpa.org/education-and-research/research/nfpa-research/fire-statistical-reports/firefighter-injuries-in-the-united-states.

- Frielander, S.K., Smoke, dust, and haze-fundamentals of aerosol behavior. 1977.

- McAllister, S., J.-Y. Chen, and A.C. Fernandez-Pello, Fundamentals of combustion processes. Vol. 302. 2011: Springer.

- Fabian, T.Z., et al., Characterization of firefighter smoke exposure. Fire Technology, 2014. 50(4): p. 993-1019. [CrossRef]

- Kesler, R.M., et al., Evaluation of combustion products in air from electric and internal combustion engine vehicles during full-scale fire experiments. Fire Safety Journal, 2025. 158: p. 104558. [CrossRef]

- Fent, K.W., et al., Understanding airborne contaminants produced by different fuel packages during training fires. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2019. 16(8): p. 532-543. [CrossRef]

- Austin, C., Municipal firefighter exposures to toxic gases and vapours. 1997, McGill University Libraries.

- Wesolek, D. and R. Kozlowski, Toxic gaseous products of thermal decomposition and combustion of natural and synthetic fabrics with and without flame retardant. Fire Materials, 2002. 26(4-5): p. 215-224. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L. and O.A. Ezekoye, Time-resolved characterization of toxic and flammable gases during venting of li-ion cylindrical cells with current interrupt devices. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries, 2025. 94: p. 105488. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J., et al., Characterization of wildland firefighters’ exposure to coarse, fine, and ultrafine particles; polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; and metal(loid)s, and estimation of associated health risks. Toxics, 2024. 12(6): p. 422. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.D.M., et al., Wildfire smoke and firefighter safety: A review of toxic particle exposure, clothing performance and health implications. Fire and Materials, 2025. n/a(n/a). [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.E. and K.W. Fent, Ultrafine and respirable particle exposure during vehicle fire suppression. Environmental Science: Processes Impacts, 2015. 17(10): p. 1749-1759. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J., et al., Assessment of coarse, fine, and ultrafine particulate matter at different microenvironments of fire stations. Chemosphere, 2023. 335: p. 139005. [CrossRef]

- Brandt-Rauf, P., et al., Health hazards of fire fighters: Exposure assessment. Occupational Environmental Medicine, 1988. 45(9): p. 606-612. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., et al., Excess of covid-19 cases and deaths due to fine particulate matter exposure during the 2020 wildfires in the united states. Science Advances, 2021. 7(33): p. eabi8789 DOI: doi:10.1126/sciadv.abi8789.

- Mayer, A.C., et al., Evaluating exposure to vocs and naphthalene for firefighters wearing different ppe configurations through measures in air, exhaled breath, and urine. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2023. 20(12): p. 6057. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/12/6057.

- Rogula-Kozłowska, W., et al., Off-gassing from firefighter suits (nomex) as an indoor source of btexs. Chemosphere, 2024. 350: p. 140996. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.C., et al., Characterizing exposure to benzene, toluene, and naphthalene in firefighters wearing different types of new or laundered ppe. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2022. 240: p. 113900. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J., et al., Human exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during structure fires: Concentrations outside and inside self-contained breathing apparatus and in vitro respiratory toxicity. Environmental Pollution, 2025. 373: p. 126112. [CrossRef]

- Fent, K.W., et al., Firefighters’ absorption of pahs and vocs during controlled residential fires by job assignment and fire attack tactic. Journal of Exposure Science Environmental Epidemiology, 2020. 30(2): p. 338-349. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., et al., Contamination and removal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in multilayered assemblies of firefighting protective clothing. Journal of Industrial Textiles, 2022. 52: p. 15280837221130772. [CrossRef]

- Stec, A.A., et al., Occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and elevated cancer incidence in firefighters. Scientific Reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Valavanidis, A., et al., Persistent free radicals, heavy metals and pahs generated in particulate soot emissions and residue ash from controlled combustion of common types of plastic. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2008. 156(1-3): p. 277-284. [CrossRef]

- Al-Malki, A.L., Serum heavy metals and hemoglobin related compounds in saudi arabia firefighters. Journal of Occupational Medicine Toxicology, 2009. 4(1): p. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Young, A.S., et al., Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (pfas) and total fluorine in fire station dust. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol, 2021. 31(5): p. 930-942. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, B.M. and C.S. Baxter, Plasticizer contamination of firefighter personal protective clothing–a potential factor in increased health risks in firefighters. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2014. 11(5): p. D43-D48. [CrossRef]

- Silver, G., et al., Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial examining the effect of blood and plasma donation on serum perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substance (pfas) levels in firefighters. BMJ Open, 2021. 11(5): p. e044833. [CrossRef]

- Papas, W., et al. Occupational exposure of on-shift ottawa firefighters to flame retardants and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Toxics, 2024. 12,. [CrossRef]

- Fent, K.W., et al., Evaluation of dermal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in fire fighters. 2013: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

- Oliveira, M., et al., Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons at fire stations: Firefighters’ exposure monitoring and biomonitoring, and assessment of the contribution to total internal dose. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2017. 323: p. 184-194. [CrossRef]

- Fent, K.W., et al., Volatile organic compounds off-gassing from firefighters’ personal protective equipment ensembles after use. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2015. 12(6): p. 404-414. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M., Characterizing the composition of contamination in wildland firefighters’ protective clothing due to the combustion of wood. 2024, Oklahoma State University: United States -- Oklahoma. p. 86. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/characterizing-composition-contamination-wildland/docview/3080053877/se-2?accountid=10906. https://quicksearch.lib.iastate.edu/openurl/01IASU_INST/01IASU_INST:01IASU?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:dissertation&genre=dissertations&sid=ProQ:ProQuest+Dissertations+%26+Theses+Global&atitle=&title=Characterizing+the+Composition+of+Contamination+in+Wildland+Firefighters%E2%80%99+Protective+Clothing+Due+to+the+Combustion+of+Wood&issn=&date=2024-01-01&volume=&issue=&spage=&au=Islam%2C+Md.+Momtaz&isbn=9798383217146&jtitle=&btitle=&rft_id=info:eric/&rft_id=info:doi/.

- Keir, J.L., et al., Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (pah) and metal contamination of air and surfaces exposed to combustion emissions during emergency fire suppression: Implications for firefighters’ exposures. Science of the Total Environment, 2020. 698: p. 134211. [CrossRef]

- Kirk, K.M. and M.B. Logan, Firefighting instructors’ exposures to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during live fire training scenarios. Journal of occupational and environmental hygiene, 2015. 12(4): p. 227-234.

- Navarro, K.M., et al., Characterization of inhalation exposures at a wildfire incident during the wildland firefighter exposure and health effects (wffehe) study. Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 2023. 67(8): p. 1011–1017. [CrossRef]

- Banks, A.P., et al., Off-gassing of semi-volatile organic compounds from fire-fighters’ uniforms in private vehicles—a pilot study. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 2021. 18(6): p. 3030. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M., et al., Occupational exposure of firefighters to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in non-fire work environments. Science of The Total Environment, 2017. 592: p. 277-287.

- Brown, F.R., et al., Levels of non-polybrominated diphenyl ether brominated flame retardants in residential house dust samples and fire station dust samples in california. Environmental Research, 2014. 135: p. 9-14. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J., et al., Evaluation of accumulated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and asbestiform fibers on firefighter vehicles: Pilot study. Fire Technology, 2019. 55(6): p. 2195-2213. [CrossRef]

- Fahy, R.F. and J.T. Petrillo, Firefighter fatalities in the us in 2021. 2022, NFPA.

- Daniels, R.D., et al., Mortality and cancer incidence in a pooled cohort of us firefighters from san francisco, chicago and philadelphia (1950–2009). Occupational Environmental Medicine, 2014. 71(6): p. 388-397. [CrossRef]

- Pinkerton, L., et al., Mortality in a cohort of us firefighters from san francisco, chicago and philadelphia: An update. Occupational Environmental Medicine, 2020. 77(2): p. 84-93. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, B., et al., Lung cancer risk after exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: A review and meta-analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2004. 112(9): p. 970-978. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, R.D., et al., Exposure–response relationships for select cancer and non-cancer health outcomes in a cohort of us firefighters from san francisco, chicago and philadelphia (1950–2009). Occupational Environmental Medicine, 2015. 72(10): p. 699-706. [CrossRef]

- Casjens, S., T. Brüning, and D. Taeger, Cancer risks of firefighters: A systematic review and meta-analysis of secular trends and region-specific differences. International Archives of Occupational Environmental Health, 2020: p. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Howe, G.R. and J.D. Burch, Fire fighters and risk of cancer: An assessment and overview of the epidemiologic evidence. American Journal of Epidemiology, 1990. 132(6): p. 1039-1050. https://academic.oup.com/aje/article-abstract/132/6/1039/81375?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

- LeMasters, G.K., et al., Cancer risk among firefighters: A review and meta-analysis of 32 studies. Journal of Occupational Environmental Medicine, 2006. 48(11): p. 1189-1202. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, R.J., et al., Risk of cancer among firefighters in california, 1988–2007. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 2015. 58(7): p. 715-729. [CrossRef]

- IAFF. Faq, what are some of the latest statistics related to cancer in the fire service? 2021; Available from: https://firefightercancersupport.org/resources/faq/.

- Fent, K.W., et al., Contamination of firefighter personal protective equipment and skin and the effectiveness of decontamination procedures. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2017. 14(10): p. 801-814. [CrossRef]

- Arouca, A.M., et al., Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contamination of personal protective equipment of brazilian firefighters during training exercise. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society, 2025. 36(10): p. e-20250089.

- Szmytke, E., et al., Firefighters’ clothing contamination in fires of electric vehicle batteries and photovoltaic modules—literature review and pilot tests results. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022. 19(19): p. 12442.

- Krzemińska, S. and M. Szewczyńska, Pah contamination of firefighter protective clothing and cleaning effectiveness. Fire Safety Journal, 2022. 131: p. 103610. [CrossRef]

- Horn, G.P., et al., Airborne contamination during post-fire investigations: Hot, warm and cold scenes. Journal of occupational and environmental hygiene, 2022. 19(1): p. 35-49.

- Wingfors, H., et al., Impact of fire suit ensembles on firefighter pah exposures as assessed by skin deposition and urinary biomarkers. Annals of Work Exposures Health, 2018. 62(2): p. 221-231. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.C., et al., Firefighter hood contamination: Efficiency of laundering to remove pahs and frs. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2019. 16(2): p. 129-140. [CrossRef]

- Li, G., V. Shanov, and M.J. Schulz, Tracking toxic gases penetration through firefighter’s garment.

- He, M., T.A. Ghee, and S. Dhaniyala, Aerosol penetration through fabrics: Experiments and theory. Aerosol Science Technology, 2020. 55(3): p. 289-301. [CrossRef]

- Jaques, P.A. and L. Portnoff, Evaluation of a passive method for determining particle penetration through protective clothing materials. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2017. 14(12): p. 995-1002. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.D., et al., Persistent organic pollutants including polychlorinated and polybrominated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans in firefighters from northern california. Chemosphere, 2013. 91(10): p. 1386-1394. [CrossRef]

- Fang, T., et al., Wildfire particulate matter as a source of environmentally persistent free radicals and reactive oxygen species. Environmental Science: Atmospheres, 2023. 3(3): p. 581-594.

- Sjöström, M., et al., Airborne and dermal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds, and particles among firefighters and police investigators. Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 2019. 63(5): p. 533-545. [CrossRef]

- Knipp, M.J., Assessment of municipal firefighters’ dermal occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. 2010, University of Cincinnati.

- Keir, J.L.A., et al., Effectiveness of dermal cleaning interventions for reducing firefighters’ exposures to pahs and genotoxins. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 2023. 20(2): p. 84-94. [CrossRef]

- Bonner, E.M., et al., Silicone passive sampling used to identify novel dermal chemical exposures of firefighters and assess ppe innovations. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2023. 248: p. 114095. [CrossRef]

- NFPA, Nfpa 1851, standard on selection, care, and maintenance of protective ensembles for structural fire fighting and proximity fire fighting.

- Stull, J.O., Ppe: How clean is clean? 2018, Fire Engineering.

- Crown, E.M., A. Feng, and X. Xu, How clean is clean enough? Maintaining thermal protective clothing under field conditions in the oil and gas sector. International Journal of Occupational Safety Ergonomics, 2004. 10(3): p. 247-254. [CrossRef]

- Banks, A.P., et al., Assessing decontamination and laundering processes for the removal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and flame retardants from firefighting uniforms. Environmental Research, 2021. 194: p. 110616. [CrossRef]

- Graber, J.M., et al., Prevalence and predictors of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (pfas) serum levels among members of a suburban us volunteer fire department. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021. 18(7): p. 3730. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/7/3730.

- Cornelsen, M., R. Weber, and S. Panglisch, Minimizing the environmental impact of pfas by using specialized coagulants for the treatment of pfas polluted waters and for the decontamination of firefighting equipment. Emerging Contaminants, 2021. 7: p. 63-76. [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.M., et al., Exposure, health effects, sensing, and remediation of the emerging pfas contaminants – scientific challenges and potential research directions. Science of The Total Environment, 2021. 780: p. 146399. [CrossRef]

- Glüge, J., et al., An overview of the uses of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (pfas). Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts, 2020. 22(12): p. 2345-2373. [CrossRef]

- Schellenberger, S., et al., An outdoor aging study to investigate the release of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (pfas) from functional textiles. Environmental Science & Technology, 2022. 56(6): p. 3471-3479. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X., et al., Comparative study of pfas treatment by uv, uv/ozone, and fractionations with air and ozonated air. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology, 2019. 5(11): p. 1897-1907.

- Bolstad-Johnson, D.M., et al., Characterization of firefighter exposures during fire overhaul. AIHAJ-American Industrial Hygiene Association, 2000. 61(5): p. 636-641. [CrossRef]

- Licina, D., et al., Clothing-mediated exposures to chemicals and particles. Environmental Science Technology, 2019. 53(10): p. 5559-5575. [CrossRef]

- Fent, K.W., et al., Systemic exposure to pahs and benzene in firefighters suppressing controlled structure fires. Annals of Occupational Hygiene, 2014. 58(7): p. 830-845. [CrossRef]

- Hirschler, M.M. Fire retardance, smoke toxicity and fire hazard. in Flame Retardants. 1994.

- Reisen, F., Inventory of major materials present in and around houses and their combustion emission products. Report to Bushfire CRC, 2011. 7.

- Kirk, K.M. and M.B. Logan, Structural fire fighting ensembles: Accumulation and off-gassing of combustion products. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2015. 12(6): p. 376-383. [CrossRef]

- Horn, G.P., et al., Impact of repeated exposure and cleaning on protective properties of structural firefighting turnout gear. Fire Technology, 2021. 57(2): p. 791-813. [CrossRef]

- Reisen, F., M. Bhujel, and J. Leonard, Particle and volatile organic emissions from the combustion of a range of building and furnishing materials using a cone calorimeter. Fire Safety Journal, 2014. 69: p. 76-88. [CrossRef]

- Shemwell, B.E. and Y.A. Levendis, Particulates generated from combustion of polymers (plastics). Journal of the Air Waste Management Association, 2000. 50(1): p. 94-102. [CrossRef]

- Tame, N.W., B.Z. Dlugogorski, and E.M. Kennedy, Formation of dioxins and furans during combustion of treated wood. Progress in Energy Combustion Science, 2007. 33(4): p. 384-408. [CrossRef]

- Tomsej, T., et al., The impact of co-combustion of polyethylene plastics and wood in a small residential boiler on emissions of gaseous pollutants, particulate matter, pahs and 1,3,5- triphenylbenzene. Chemosphere, 2018. 196: p. 18-24. [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, L., Y.A. Levendis, and P. Vouros, Exploratory study on the combustion and pah emissions of selected municipal waste plastics. Environmental Science Technology, 1993. 27(13): p. 2885-2895.

- Fent, K.W., et al., Airborne contaminants during controlled residential fires. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2018. 15(5): p. 399-412. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.L., S.M. McCaffrey, and T. Patel-Weynand, Wildland fire smoke in the united states: A scientific assessment. 2022: Springer Nature.

- Nelson, J., et al., Physicochemical characterization of personal exposures to smoke aerosol and pahs of wildland firefighters in prescribed fires. Exposure and Health, 2021. 13(1): p. 105-118. [CrossRef]

- Prichard, S.J., et al., Wildland fire emission factors in north america: Synthesis of existing data, measurement needs and management applications. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 2020. 29(2): p. 132-147. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H., et al., Mutagenicity and lung toxicity of smoldering vs. Flaming emissions from various biomass fuels: Implications for health effects from wildland fires. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2018. 126(1): p. 017011 DOI: doi:10.1289/EHP2200.

- Urbanski, S., Wildland fire emissions, carbon, and climate: Emission factors. Forest Ecology and Management, 2014. 317: p. 51-60. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M., et al., Individual and cumulative impacts of fire emissions and tobacco consumption on wildland firefighters’ total exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2017. 334: p. 10-20. [CrossRef]

- Adetona, O., et al., Exposure of wildland firefighters to carbon monoxide, fine particles, and levoglucosan. Annals of Occupational Hygiene, 2013. 57(8): p. 979-991. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.L., et al., Adverse respiratory effects following overhaul in firefighters. Journal of Occupational Environmental Medicine, 2001. 43(5): p. 467-473.

- Jones, L., et al., Respiratory protection for firefighters—evaluation of cbrn canisters for use during overhaul. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2015. 12(5): p. 314-322. [CrossRef]

- Broznitsky, N., et al., A field investigation of 3 masks proposed as respiratory protection for wildland firefighters: A randomized controlled trial in british columbia, canada. Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Garg, P., et al., The effectiveness of filter material for respiratory protection worn by wildland firefighters. Fire Safety Journal, 2023. 139: p. 103811. [CrossRef]

- Fent, K.W., D.E. Evans, and J. Couch, Evaluation of chemical and particle exposures during vehicle fire suppression training. 2010: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and ….

- Fent, K.W. and D.E. Evans, Assessing the risk to firefighters from chemical vapors and gases during vehicle fire suppression. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 2011. 13(3): p. 536-543. [CrossRef]

- Truchot, B., F. Fouillen, and S. Collet, An experimental evaluation of toxic gas emissions from vehicle fires. Fire Safety Journal, 2018. 97: p. 111-118. [CrossRef]

- Kuti, R., et al., Examination of harmful substances emitted to the environment during an electric vehicle fire with a full-scale fire experiment and laboratory investigations. Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Analyses, 2025. 3(1): p. 1. https://www.mdpi.com/2813-4648/3/1/1.

- Kim, Y.H., et al., Chemical components of electric vehicle and internal combustion engine vehicle fire smoke and their mutagenic effects. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Willstrand, O., et al., Toxic gases from electric vehicle fires. DOSTUPNÉ NA: https://www. ri. se/sites/default/files/2020-12/FIVE2020_Willstrand. pdf, 2020.

- Liu, J., et al., Are first responders prepared for electric vehicle fires? A national survey. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 2023. 179: p. 106903. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W., et al., Disproportionately large impacts of wildland-urban interface fire emissions on global air quality and human health. Science Advances, 2025. 11(11): p. eadr2616 DOI: doi:10.1126/sciadv.adr2616.

- Holder, A.L., et al., Hazardous air pollutant emissions estimates from wildfires in the wildland urban interface. PNAS Nexus, 2023. 2(6). [CrossRef]

- Benedict, K.B., et al., Wildland urban interface (wui) emissions: Laboratory measurement of aerosol and trace gas from combustion of manufactured building materials. ACS ES&T Air, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Silberstein, J.M., et al., Residual impacts of a wildland urban interface fire on urban particulate matter and dust: A study from the marshall fire. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 2023. 16(9): p. 1839-1850. [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, T., et al., Wildland-urban interface fire ashes as a major source of incidental nanomaterials. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2023. 443: p. 130311. [CrossRef]

- Keir, J.L.A., et al., Use of silicone wristbands to measure firefighters’ exposures to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (pahs) during live fire training. Environmental Research, 2023. 239: p. 117306. [CrossRef]

- Fent, K.W., et al., Firefighters’ urinary concentrations of voc metabolites after controlled-residential and training fire responses. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2022. 242: p. 113969. [CrossRef]

- Fent, K.W., et al., Firefighters’ and instructors’ absorption of pahs and benzene during training exercises. International Journal of Hygiene Environmental Health, 2019. 222(7): p. 991-1000. [CrossRef]

- Fernando, S., et al., Evaluation of firefighter exposure to wood smoke during training exercises at burn houses. Environmental Science Technology, 2016. 50(3): p. 1536-1543. [CrossRef]

- Kirk, K.M. and M.B. Logan, Exposures to air contaminants in compartment fire behavior training (cfbt) using particleboard fuel. Journal of occupational and environmental hygiene, 2019.

- Horn, G.P., et al., Development of fireground exposure simulator (fes) prop for ppe testing and evaluation. Fire Technology, 2020. 56(5): p. 2331-2344. [CrossRef]

- Fabian, T., et al., Firefighter exposure to smoke particulates. 2010: Underwriters Laboratories.

- Kirk, K.M., M. Ridgway, and M.B. Logan, Firefighter exposures to airborne contaminants during extinguishment of simulated residential room fires. 2011, Research Report 2011-01/August 2011 (https://iab. gov/Uploads/).

- Rosenfeld, P.E., et al., Perfluoroalkyl substances exposure in firefighters: Sources and implications. Environmental Research, 2023. 220: p. 115164. [CrossRef]

- Maizel, A.C., et al., Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in new firefighter turnout gear textiles. 2023: National Institute of Standards and Technology, US Department of Commerce.

- Hall, S.M., et al., Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in dust collected from residential homes and fire stations in north america. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020. 54(22): p. 14558-14567. [CrossRef]

- Dobraca, D., et al., Biomonitoring in california firefighters: Metals and perfluorinated chemicals. Journal of Occupational Environmental Medicine, 2015. 57(1): p. 88. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.L., et al., Serum per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance concentrations in four municipal us fire departments. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 2023. 66(5): p. 411-423. [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, N.-U.-S., et al., Firefighters’ exposure to per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (pfas) as an occupational hazard: A review. Frontiers in Materials, 2023. Volume 10 - 2023. [CrossRef]

- Schöpel, M., et al., Analytical methods for pfas in products and the environment. 2022, Nordisk Ministerråd.

- Gainey, S.J., et al., Exposure to a firefighting overhaul environment without respiratory protection increases immune dysregulation and lung disease risk. PloS One, 2018. 13(8): p. e0201830. [CrossRef]

- Pleil, J.D., M.A. Stiegel, and K.W. Fent, Exploratory breath analyses for assessing toxic dermal exposures of firefighters during suppression of structural burns. Journal of Breath Research, 2014. 8(3): p. 037107. [CrossRef]

- Feunekes, F., et al., Uptake of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons among trainers in a fire-fighting training facility. American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal, 1997. 58(1): p. 23-28. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, G.C., et al., Role of clothing in both accelerating and impeding dermal absorption of airborne svocs. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 2016. 26(1): p. 113-118. [CrossRef]

- Ireland, N., Y.-H. Chen, and C.S.-J. Tsai, Potential penetration of engineered nanoparticles under practical use of protective clothing fabrics. ACS Chemical Health & Safety, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M., et al., Study on aerosol penetration through clothing and individual protective equipment. 2009, DEFENCE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY ORGANISATION VICTORIA (AUSTRALIA) HUMAN ….

- Cherry, N., et al., Urinary 1-hydroxypyrene and skin contamination in firefighters deployed to the fort mcmurray fire. Annals of work exposures and health, 2019. 63(4): p. 448-458.

- Alexander, B.M., Contamination of firefighter personal protective gear. 2012, University of Cincinnati.

- Sousa, G., et al., Gravimetric, morphological, and chemical characterization of fine and ultrafine particulate matter inside fire stations. Building and Environment, 2024: p. 111403. [CrossRef]

- EPA, Epa to-13a determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (pahs) in ambient air using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (gc/ms).

- EPA, Epa to-17 determination of volatile organic compounds in ambient air using active sampling onto sorbent tubes.

- Jeramy, B., et al., Evaluation of silicone-based wristbands as passive sampling systems using pahs as an exposure proxy for carcinogen monitoring in firefighters: Evidence from the firefighter cancer initiative. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sen, P., et al., Evaluation of passive silicone samplers compared to active sampling methods for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during fire training. Toxics, 2025. 13(2): p. 132. https://www.mdpi.com/2305-6304/13/2/132. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11860701/.

- Bonner, E.M., et al., Addressing the need for individual-level exposure monitoring for firefighters using silicone samplers. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 2025. 35(2): p. 180-195. [CrossRef]

- Bakali, U., et al., Mapping carcinogen exposure across urban fire incident response arenas using passive silicone-based samplers. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2021. 228: p. 112929. [CrossRef]

- Stephanie, C.H., et al., Comparing the use of silicone wristbands, hand wipes, and dust to evaluate children’s exposure to flame retardants and plasticizers. Environmental Science & Technology, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Gong, M., Y. Zhang, and C.J. Weschler, Measurement of phthalates in skin wipes: Estimating exposure from dermal absorption. Environmental Science & Technology, 2014. 48(13): p. 7428-7435. [CrossRef]

- Paiva, A.M., et al., Biomonitoring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons exposure and short-time health effects in wildland firefighters during real-life fire events. Science of The Total Environment, 2024: p. 171801. [CrossRef]

- Gill, B. and P. Britz-McKibbin, Biomonitoring of smoke exposure in firefighters: A review. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health, 2020. 15: p. 57-65. [CrossRef]

- Engelsman, M., et al., Biomonitoring in firefighters for volatile organic compounds, semivolatile organic compounds, persistent organic pollutants, and metals: A systematic review. Environmental Research, 2020. 188: p. 109562. [CrossRef]

- Marín-Sáez, J., et al., From flames to lab: A robust non-destructive sampling method for evaluating pah exposure in firefighters’ personal protection equipment. Microchemical Journal, 2024. 207: p. 111909. [CrossRef]

- Tysinger, P.M., Characterization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (pahs) in smoke produced from a preliminary small-scale live burn methodology, in Textile Engineering. 2024, North Carolina State University: Raleigh, North Carolina.

- Andersson, J.T. and C. Achten, Time to say goodbye to the 16 epa pahs? Toward an up-to-date use of pacs for environmental purposes. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds, 2015. 35(2-4): p. 330-354. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.A.G., et al., Targeted gc-ms analysis of firefighters’ exhaled breath: Exploring biomarker response at the individual level. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2019. 16(5): p. 355-366. [CrossRef]

- Geer Wallace, M.A., et al., Non-targeted gc/ms analysis of exhaled breath samples: Exploring human biomarkers of exogenous exposure and endogenous response from professional firefighting activity. Journal of Toxicology Environmental Health, Part A, 2019. 82(4): p. 244-260. [CrossRef]

- Kammer, R., H. Tinnerberg, and K. Eriksson, Evaluation of a tape-stripping technique for measuring dermal exposure to pyrene and benzo (a) pyrene. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 2011. 13(8): p. 2165-2171.

- Fent, K.W., et al., Tape-strip sampling for measuring dermal exposure to 1, 6-hexamethylene diisocyanate. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment Health, 2006: p. 225-231.

- Barros, B., M. Oliveira, and S. Morais, Biomonitoring of firefighting forces: A review on biomarkers of exposure to health-relevant pollutants released from fires. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B, 2023. 26(3): p. 127-171. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M., et al., Firefighters exposure to fire emissions: Impact on levels of biomarkers of exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and genotoxic/oxidative-effects. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2020. 383: p. 121179. [CrossRef]

- Keir, J.L.A., The use of urinary biomarkers to assess exposures to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (pahs) and other organic mutagens. 2017, Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa.

- Sara A. Jahnke, et al., Fireground exposure of firefighters: A literature review. 2021, NFPA.

- Carrico, C.M., et al., Rapidly evolving ultrafine and fine mode biomass smoke physical properties: Comparing laboratory and field results. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 2016. 121(10): p. 5750-5768. [CrossRef]

- Cedeño Laurent, J.G., et al., Physicochemical characterization of the particulate matter in new jersey/new york city area, resulting from the canadian quebec wildfires in june 2023. Environ Sci Technol, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Austin, C., et al., Characterization of volatile organic compounds in smoke at municipal structural fires. Journal of Toxicology Environmental Health Part A, 2001. 63(6): p. 437-458. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.C., et al., Impact of select ppe design elements and repeated laundering in firefighter protection from smoke exposure. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2020. 17(11-12): p. 505-514. [CrossRef]

- Bakali, U., et al., Characterization of fire investigators’ polyaromatic hydrocarbon exposures using silicone wristbands. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2024. 278: p. 116349. [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, J.L., et al., Characterizing firefighter’s exposure to over 130 svocs using silicone wristbands: A pilot study comparing on-duty and off-duty exposures. Science of The Total Environment, 2022. 834: p. 155237. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, C.S., et al., Exposure of firefighters to particulates and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2014. 11(7): p. D85-D91. [CrossRef]

- Bray, R.J., S. Tretsiakova-McNally, and J. Zhang, The controlled atmosphere cone calorimeter: A literature review. Fire Technology, 2023. 59(5): p. 2203-2245. [CrossRef]

- Sonnier, R., H. Vahabi, and C. Chivas-Joly, New insights into the investigation of smoke production using a cone calorimeter. Fire Technology, 2019. 55(3): p. 853-873. [CrossRef]

- Chatenet, S., An instrumented controlled-atmosphere cone calorimeter to characterize electrical cable behavior in depleted fires. 2019, Université de Lille.

- Barabad, M.L.M., et al., Characteristics of particulate matter and volatile organic compound emissions from the combustion of waste vinyl. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health, 2018. 15(7): p. 1390.

- Wang, S., et al., Smoldering and flaming of disc wood particles under external radiation: Autoignition and size effect. Frontiers in Mechanical Engineering, 2021. 7. [CrossRef]

- Goo, J., Study on the real-time size distribution of smoke particles for each fire stage by using a steady-state tube furnace method. Fire Safety Journal, 2015. 78: p. 96-101. [CrossRef]

- Blomqvist, P., et al., Detailed determination of smoke gas contents using a small-scale controlled equivalence ratio tube furnace method. Fire and Materials: An International Journal, 2007. 31(8): p. 495-521. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, F., et al., Obtaining emission factors for pm2, 5, gases and particles size distribution generated from the combustion of eucalyptus globulus and nothofagus obliqua on ideal conditions using a controlled combustion chamber 3ce.

- Singh, D., et al., Physicochemical and toxicological properties of wood smoke particulate matter as a function of wood species and combustion condition. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2023. 441: p. 129874. [CrossRef]

- Stec, A.A. and J. Rhodes, Bench scale generation of smoke particulates and hydrocarbons from burning polymers. Fire Safety Science, 2011. 10: p. 629-639.

- Stec, A.A., T.R. Hull, and K. Lebek, Characterisation of the steady state tube furnace (iso ts 19700) for fire toxicity assessment. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2008. 93(11): p. 2058-2065. [CrossRef]

- Babrauskas, V., The cone calorimeter. SFPE handbook of fire protection engineering, 2016: p. 952-980.

- Malmborg, V., et al. Biomass burning emissions and influence of combustion variables in the cone-calorimeter. in International Aerosol Conference 2022. 2022.

- Mustafa, B.G., et al. Particle size distribution during pine wood combustion on a cone calorimeter. in Proceedings of the Cambridge Particles Meeting 2017. 2017. University of Cambridge.

- ASTM, E1354 − 22b standard test method for heat and visible smoke release rates for materials and products using an oxygen consumption calorimeter. 2022, ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA DOI: DOI: 10.1520/E1354-17.

- ISO, 5660-1 reaction-to-fire tests — heat release, smoke production and mass loss rate, in Part 1: Heat release rate (cone calorimeter method) and smoke production rate (dynamic measurement). 2015: Geneva, Switzerland.

- Reisen, F., et al., Ground-based field measurements of pm2.5 emission factors from flaming and smoldering combustion in eucalypt forests. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 2018. 123(15): p. 8301-8314. [CrossRef]

- Salvador, S., M. Quintard, and C. David, Combustion of a substitution fuel made of cardboard and polyethylene: Influence of the mix characteristics—experimental approach. Fuel, 2004. 83(4-5): p. 451-462.

- Marsh, N.D., R.G. Gann, and M.R. Nyden, Smoke component yields from bench-scale fire tests: 2. Iso 19700 controlled equivalence ratio tube furnace. 2013: US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology.

- Purser, J.A., et al., Repeatability and reproducibility of the iso/ts 19700 steady state tube furnace. Fire Safety Journal, 2013. 55: p. 22-34. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H., et al., Toxicity of fresh and aged anthropogenic smoke particles emitted from different burning conditions. Science of The Total Environment, 2023. 892: p. 164778. [CrossRef]

- Garg, P., et al., Variations in gaseous and particulate emissions from flaming and smoldering combustion of douglas fir and lodgepole pine under different fuel moisture conditions. Combustion and Flame, 2024. 263: p. 113386. [CrossRef]

- Borucka, M., et al. Analysis of flammability and smoke emission of plastic materials used in construction and transport. Materials, 2023. 16, 2444. [CrossRef]

- Wolffe, T.A.M., et al., Contamination of uk firefighters personal protective equipment and workplaces. Scientific Reports, 2023. 13(1): p. 65. [CrossRef]

- Krzemińska, S. and M. Szewczyńska, Analysis and assessment of hazards caused by chemicals contaminating selected items of firefighter personal protective equipment–a literature review. Safety & Fire Technology, 2020. 56(2).

- NFPA, Nfpa 1971, standard on protective ensembles for structural fire fighting and proximity fire fighting. 2018: Quincy MA, USA.

- Lu, Y., G. Song, and J. Li, Analysing performance of protective clothing upon hot liquid exposure using instrumented spray manikin. Annals of Occupational Hygiene, 2013. 57(6): p. 793-804. [CrossRef]

- Ross, K., R. Barker, and A. Deaton, Translation between heat loss measured using guarded sweating hot plate, sweating manikin, and physiologically assessed heat stress of firefighter turnout ensembles, in Performance of protective clothing and equipment: 9 th volume, emerging issues and technologies. 2012, ASTM International.

- Song, G., et al., Thermal protective performance of protective clothing used for low radiant heat protection. Textile Research Journal, 2011. 81(3): p. 311-323. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y., J. Li, and G. Song, The effect of moisture content within multilayer protective clothing on protection from radiation and steam. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 2018. 24(2): p. 190-199. [CrossRef]

- Rosting, C., et al., Contamination of firefighters’ merino wool and mixed fibre sweater and hood undergarments with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 2025: p. wxaf031. [CrossRef]

- Engelsman, M., et al., Exposure to metals and semivolatile organic compounds in australian fire stations. Environmental Research, 2019. 179: p. 108745. [CrossRef]

- Banks, A.P.W., et al., The occurrence of pahs and flame-retardants in air and dust from australian fire stations. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2020. 17(2-3): p. 73-84. [CrossRef]

- Rogula-Kozłowska, W., et al., Respirable particles and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons at two polish fire stations. Building Environment, 2020. 184: p. 107255. [CrossRef]

- Bai, H., et al., Theoretical model of single fiber efficiency and the effect of microstructure on fibrous filtration performance: A review. Industrial Engineering Chemistry Research, 2020. 6(1): p. 3-36. [CrossRef]

- Al Assaad, D., et al., Modeling of indoor particulate matter deposition to occupant typical wrinkled shirt surface. Building and Environment, 2020. 179: p. 106965. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., et al., Deposition of fine particles on vertical textile surfaces: A small-scale chamber study. Building Environment, 2018. 135: p. 308-317. [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.C., Particle deposition and decay in a chamber and the implications to exposure assessment. Water, Air, Soil Pollution, 2006. 175(1): p. 323-334.

- Ranade, M., Adhesion and removal of fine particles on surfaces. Aerosol Science Technology, 1987. 7(2): p. 161-176. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A., P. Dunn, and R. Brach, Microparticle detachment from surfaces exposed to turbulent air flow: Effects of flow and particle deposition characteristics. Journal of Aerosol Science, 2004. 35(7): p. 805-821. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A., P. Dunn, and M. Qazi, Experiments and validation of a model for microparticle detachment from a surface by turbulent air flow. Journal of Aerosol Science, 2008. 39(8): p. 645-656.

- Friedlander, S., Particle diffusion in low-speed flows. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 1967. 23(2): p. 157-164.

- Gutfinger, C. and S. Friedlander, Enhanced deposition of suspended particles to fibrous surfaces from turbulent gas streams. Aerosol Science Technology, 1985. 4(1): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R. and S. Ratnapandian, Care and maintenance of textile products including apparel and protective clothing. 2018: CRC Press.

- Hill, M.A., et al., Investigation of aerosol penetration through individual protective equipment in elevated wind conditions. Aerosol Science Technology, 2013. 47(7): p. 705-713. [CrossRef]

- Fent, K.W., et al., Flame retardants, dioxins, and furans in air and on firefighters’ protective ensembles during controlled residential firefighting. Environment International, 2020. 140: p. 105756. [CrossRef]

- Gao, P., et al., Evaluation of nano-and submicron particle penetration through ten nonwoven fabrics using a wind-driven approach. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2011. 8(1): p. 13-22. [CrossRef]

- Licina, D. and W. Nazaroff, Clothing as a transport vector for airborne particles: Chamber study. Indoor Air, 2018. 28(3): p. 404-414. [CrossRef]

- Cho, M., et al., Simple formula for the non-uniform contaminant deposition on a cylindrical human body surrounded by porous clothing. Journal of Mechanical Science Technology, 2016. 30(4): p. 1595-1601. [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.F., Measurement of the deposition of aerosol particles to skin, hair and clothing. 1999.

- Easter, E., D. Lander, and T. Huston, Risk assessment of soils identified on firefighter turnout gear. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2016. 13(9): p. 647-657. [CrossRef]

- Stull, J.O., et al., Evaluating the effectiveness of different laundering approaches for decontaminating structural fire fighting protective clothing, in Performance of protective clothing: Fifth volume. 1996, ASTM International.

- Wilkinson, A.F., et al., Use of undergloves to assess pathways leading to contamination on firefighters’ hands. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 2025: p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Gagas, D.F., Characterization of contaminants on firefighter” s protective equipment a firefighter’s potential exposure to heavy metals during a structure fire. 2015.

- Huston, T.N., Identification of soils on firefighter turnout gear from the philadelphia fire department. 2014.

- Lao, J.-Y., et al., Size distribution and clothing-air partitioning of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons generated by barbecue. Science of the Total Environment, 2018. 639: p. 1283-1289. [CrossRef]

- Rakowska, J., M. Rachwał, and A. Walczak, Health exposure assessment of firefighters caused by pahs in pm4 and tsp after firefighting operations. Atmosphere, 2022. 13(8): p. 1263.

- Keir, J.L., et al., Elevated exposures to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and other organic mutagens in ottawa firefighters participating in emergency, on-shift fire suppression. Environmental Science Technology, 2017. 51(21): p. 12745-12755. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, A. and M. Byrne, The influence of human physical activity and contaminated clothing type on particle resuspension. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity, 2014. 127: p. 119-126. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, A. and M. Byrne, A study of the size distribution of aerosol particles resuspended from clothing surfaces. Journal of Aerosol Science, 2014. 75: p. 94-103. [CrossRef]

- Ziskind, G., M. Fichman, and C. Gutfinger, Resuspension of particulates from surfaces to turbulent flows—review and analysis. Journal of Aerosol Science, 1995. 26(4): p. 613-644. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y., K. Inthavong, and J. Tu, Dynamic meshing modelling for particle resuspension caused by swinging manikin motion. Building Environment, 2017. 123: p. 529-542. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., et al., Characterizing the partitioning behavior of formaldehyde, benzene and toluene on indoor fabrics: Effects of temperature and humidity. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2021. 416: p. 125827.

- Girase, A., A. Shinde, and R.B. Ormond Qualitative assessment of off-gassing of compounds from field-contaminated firefighter jackets with varied air exposure time intervals using headspace gc-ms. Textiles, 2023. 3, 246-256. [CrossRef]

- Macy, G.B., et al., Examining behaviors related to retirement, cleaning, and storage of turnout gear among rural firefighters. Workplace Health Safety, 2020. 68(3): p. 129-138. [CrossRef]

- Helgesen, J., Management and decontamination of firefighters structural protective clothing and equipment. 2010.

- Qian, J., A.R. Ferro, and K.R. Fowler, Estimating the resuspension rate and residence time of indoor particles. Journal of the Air Waste Management Association, 2008. 58(4): p. 502-516. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H., et al., A review of airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (pahs) and their human health effects. Environment International, 2013. 60: p. 71-80.

- Shen, B., et al., High levels of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in vacuum cleaner dust from california fire stations. Environmental Science Technology, 2015. 49(8): p. 4988-4994. [CrossRef]

- Bates, B., et al., Effect of different laundering and drying procedures on the performance of fire-protective fabrics. Journal of Polymer Science, 2025. 63(16): p. 3496-3508. [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.S. and P.I. Dolez, Aging of high-performance fibers used in firefighters’ protective clothing: State of the knowledge and path forward. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2023. 140(32): p. e54255. [CrossRef]

- Munevar-Ortiz, L., J.A. Nychka, and P.I. Dolez, Moisture barriers used in firefighters’ protective clothing: Effect of accelerated thermal aging on their mechanical and barrier performance. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. n/a(n/a): p. e55548. [CrossRef]

- Allen, J., Investig ation of turnout clothing contamination and validation of cleaning procedures – phase 1. 2017, Intertek Testing Services NA, Inc.

- Tarley, J., Ppe cleaning validation_supplement c: Investigation of simulated fire ground exposures. 2019, NIOSH NPPTL.

- Cereceda-Balic, F., et al., Emission factors for pm2. 5, co, co2, nox, so2 and particle size distributions from the combustion of wood species using a new controlled combustion chamber 3ce. Science of the Total Environment, 2017. 584: p. 901-910. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, F., et al., Effects of wood moisture on emission factors for pm2. 5, particle numbers and particulate-phase pahs from eucalyptus globulus combustion using a controlled combustion chamber for emissions. Science of the Total Environment, 2019. 648: p. 737-744. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.L., et al., Particles emitted from smouldering peat: Size-resolved composition and emission factors. Environmental Science: Atmospheres, 2025. 5(3): p. 348-366.

- Wilkinson, A.F., et al., Use of preliminary exposure reduction practices or laundering to mitigate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contamination on firefighter personal protective equipment ensembles. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2023. 20(3): p. 2108. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/3/2108.

- Trojanowski, R. and V. Fthenakis, Nanoparticle emissions from residential wood combustion: A critical literature review, characterization, and recommendations. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2019. 103: p. 515-528. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, N., et al., Investigating repetitive reaction pathways for the formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in combustion processes. Combustion Flame, 2017. 180: p. 250-261. [CrossRef]

- Töpperwien, K., et al., Burn parameters affect pah emissions at conditions relevant for prescribed fires. Atmospheric Pollution Research, 2025. 16(5): p. 102438. [CrossRef]

- Holder, A.L. and A.P. Sullivan, Emissions, chemistry, and the environmental impacts of wildland fire. ACS ES&T Water, 2024. 4(9): p. 3614-3618. [CrossRef]

- Shen, G., et al., Influence of fuel mass load, oxygen supply and burning rate on emission factor and size distribution of carbonaceous particulate matter from indoor corn straw burning. Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2013. 25(3): p. 511-519. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, N.E., et al., Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (pah), soot and light gases formed in the pyrolysis of acetylene at different temperatures: Effect of fuel concentration. Journal of Analytical Applied Pyrolysis, 2013. 103: p. 126-133. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., et al., Effect of interactions of biomass constituents on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (pah) formation during fast pyrolysis. Journal of Analytical Applied Pyrolysis 2014. 110: p. 264-269.

- Marquis, D., E. Guillaume, and A. Camillo. Effects of oxygen availability on the combustion behaviour of materials in a controlled atmosphere cone calorimeter. in Proceedings of the Eleventh International Symposium on Fire Safety Science. 2014.

- Forester, C.D. and J. Tarley, Effects of temperature and advanced cleaning practices on the removal of select organic chemicals from structural firefighter gear. Fire Technology, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Girase, A., D. Thompson, and R.B. Ormond, Bench-scale and full-scale level evaluation of the effect of parameters on cleaning efficacy of the firefighters’ ppe. Textiles, 2023. 3(2): p. 201-218. https://www.mdpi.com/2673-7248/3/2/14.

- Shinde, A. and R.B. Ormond, Headspace sampling-gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer as a screening method to thermally extract fireground contaminants from retired firefighting turnout jackets. Fire Materials, 2021. 45(3): p. 415-428. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J., et al., Preliminary analyses of accumulation of carcinogenic contaminants on retired firefighter ensembles. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene: p. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Kander, M.C., et al., Evaluating the ingress of total polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (pahs) specifically naphthalene through firefighter hoods and base layers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene: p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Shen, G., et al., Emission and size distribution of particle-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from residential wood combustion in rural china. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2013. 55: p. 141-147. [CrossRef]

- Billets, S., A literature review of wipe sampling methods for chemical warfare agents and toxic industrial chemicals. 2007, US EPA.

- Horn, G.P., et al., Hierarchy of contamination control in the fire service: Review of exposure control options to reduce cancer risk. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 2022(just-accepted): p. 1-33.

- Stolpman, D., et al., Decontamination of metals from firefighter turnout gear. Journal of occupational and environmental hygiene, 2021(just-accepted): p. 1-11.

- SZMYTKE, E., et al., Firefighters’ protective clothing – water cleaning method vs liquid co method in aspect of efficiency. Architecture, Civil Engineering, Environment, 2022. 15(2): p. 169-176 DOI: doi:10.2478/acee-2022-0024.

- Calvillo, A., et al., Pilot study on the efficiency of water-only decontamination for firefighters’ turnout gear. Journal of Occupational Environmental Hygiene, 2019. 16(3): p. 199-205. [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, J. and R.E. Gold, Water hardness, detergent type, and prewash product use as factors affecting methyl parathion residue retained in protective apparel fabrics. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 1990. 8(4): p. 61-67.

- Krzemińska, S.M., et al. Effects of washing conditions on pah removal effectiveness in firefighter protective clothing materials. Materials, 2025. 18, 4073. [CrossRef]

- Girase, A., D. Thompson, and R.B. Ormond, Comparative analysis of the liquid co2 washing with conventional wash on firefighters’ personal protective equipment (ppe). Textiles, 2022. 2(4): p. 624-632. https://www.mdpi.com/2673-7248/2/4/36.

- Hossain, M.T., A.G. Girase, and R.B. Ormond, Evaluating the performance of surfactant and charcoal-based cleaning products to effectively remove pahs from firefighter gear. Frontiers in Materials, 2023. 10: p. 207.

- Aslanidou, D., I. Karapanagiotis, and C. Panayiotou, Tuneable textile cleaning and disinfection process based on supercritical co2 and pickering emulsions. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids, 2016. 118: p. 128-139.

- Farcas, D., et al., Survival of staphylococcus aureus on the outer shell of fire fighter turnout gear after sanitation in a commercial washer/extractor. Journal of Occupational Medicine Toxicology, 2019. 14(1): p. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Sorbo, N.W., Firefighter turnout gear svoc cleaning efficiency of co2-based cleaning process compared to traditional water-based cleaning methods. 2020.

- Rezazadeh, M. and D.A. Torvi, Assessment of factors affecting the continuing performance of firefighters’ protective clothing: A literature review. Fire Technology, 2011. 47(3): p. 565-599. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., et al., Interaction effects of washing and abrasion on thermal protective performance of flame-retardant fabrics. International Journal of Occupational Safety Ergonomics, 2018. 27(1): p. 86-94.

- Salmi, R. and J. Laitinen, Evaluation of the decontamination methods for turnout gear. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 2025: p. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Lucena, M.A., et al., Evaluation of an ozone chamber as a routine method to decontaminate firefighters’ ppe. International journal of environmental research and public health, 2021. 18(20): p. 10587.

- Commission, P.S., Gs specification: Testing and assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (pahs) in the awarding of gs marks specification pursuant to article 21 (1) no. 3 of the product safety act (prodsg). 2020.

- Aranda-Rodriguez, R., et al., Profiles of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in firefighter turnout gear and their impact on exposure assessment. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts, 2025.

- DeBono, N.L., et al., Firefighting and cancer: A meta-analysis of cohort studies in the context of cancer hazard identification. Safety and Health at Work, 2023. 14(2): p. 141-152. [CrossRef]

- Pukkala, E., et al., Cancer incidence among firefighters: 45 years of follow-up in five nordic countries. Occupational Environmental Medicine, 2014. 71(6): p. 398-404. [CrossRef]

- Soteriades, E.S., et al., Cardiovascular disease in us firefighters: A systematic review. Cardiology in Review, 2011. 19(4). https://journals.lww.com/cardiologyinreview/fulltext/2011/07000/cardiovascular_disease_in_us_firefighters__a.5.aspx.

- Chen, H., et al., Cardiovascular health impacts of wildfire smoke exposure. Particle and Fibre Toxicology, 2021. 18(1): p. 2. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L., et al., Cardiovascular strain of firefighting and the risk of sudden cardiac events. Exercise Sport Sciences Reviews, 2016. 44(3): p. 90-97. [CrossRef]

- Denise, M.G., et al., Arterial stiffness, oxidative stress, and smoke exposure in wildland firefighters. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.V., et al., Firefighters’ occupational exposure to air pollution: Impact on copd and asthma--study protocol. BMJ Open Respiratory Research, 2024. 11(1): p. e001951. [CrossRef]

- Wah, W., et al., Systematic review of impacts of occupational exposure to wildfire smoke on respiratory function, symptoms, measures and diseases. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 2025. 263: p. 114463. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-E., et al., Urinary concentrations of organophosphate esters and associated health outcomes in korean firefighters. Chemosphere, 2023. 339: p. 139641. [CrossRef]

- Hoppe-Jones, C., et al., Evaluation of fireground exposures using urinary pah metabolites. Journal of exposure science & environmental epidemiology, 2021. 31(5): p. 913-922.

- Hwang, J., et al. Urinary metabolites of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in firefighters: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022. 19, 8475. [CrossRef]

|

Sample preparation |

Decontamination method |

PPE item |

Decontamination efficacy and performance change | Ref |

| Fireground smoke exposure simulator, mannequin trial | On scene wet soap decontamination followed by machine laundering | Knit and particulate blocking hood, jacket | Laundering showed a positive association with PAH breakthrough and a negative association with benzene breakthrough | [168] |

| Firefighter exposed to live controlled fire in a single family residential structure | Front load washing machine without agitator, 55 min wash, ARM and HAMMER Plus OxiClean detergent | Hood | Total PAHs reduced by 75.5%. Benzo[a]pyrene 81.6%, phenanthrene 34.8%. Total PBDEs decreased by 98.9%, NPBFRs increased by 240%, OPFRs reduced by 41.9% | [63] |

| Simulated wood frame residential structure fire with ceiling lining and furnishings | Gross on scene decontamination | Jacket | BDE 47, BDE 99, and BDE 100 reduced by 82 to 97%. Limited or no removal observed for BDE 153 and TBBPA. TDCPP increased by 421% | [217] |

| Bench top combustion chamber | NFPA 1851 compliant washing using 60 L water, 40 g detergent, 45 RPM rotation, 20 min wash | Fabric swatch on protective clothing | Total PAH removal ranged from 65% to 97% depending on weathering and aging condition | [28] |

| Live fire training enclosure simulator | Laboratory washing machine using 65 L water at 60 C with non phosphate detergent | Fabric swatch attached to protective clothing | PAH reduction of 79 ± 14% for outer shell, 63 ± 25% for membrane, and 58 ± 14% for thermal barrier | [60] |

| Physical doping using 16 EPA PAHs | Industrial detergent containing D limonene, washer extractor programmed per NFPA 1851 | Fabric swatch | Total PAH removal ranged from 20 to 50% at standard temperature and 50 to 80% at elevated temperature | [258] |

| Physical doping using 16 EPA PAHs | Bench scale washing using water shaker bath and full-scale washer extractor at 40 and 65 C for 15 and 60 min using two commercial detergents | Fabric swatch | Greater than 90% removal for phenol, approximately 80% for phenanthrene, 45 to 55% for pyrene, 15 to 25% for benzo[a]pyrene, and 10 to 20% for DEHP | [259] |

| Outer shell fabric swatches inoculated with Staphylococcus aureus | ASTM E2274 washing followed by commercial washer for jacket | Outer shell fabric swatch | Ten second disinfection reduced bacterial viability by 73 to 100%. Commercial washer achieved 99.7% effectiveness | [274] |

| Physical doping using 16 EPA PAHs | Bench scale washing using water shaker with eight commercial detergents including charcoal based products at 0 to 50 mL | Fabric swatch | Low molecular weight PAHs reduced by 60 to 90%. High molecular weight PAHs reduced by 10 to 90% depending on detergent level | [272] |

| Physical doping using 10 NFPA 1851 compounds | CO2 plus system | Fabric swatch | Approximately 100% removal for all tested NFPA compounds | [275] |

| Used and repeatedly contaminated PPE donated from fire stations | Liquid CO2 cleaning under 53 bar pressure | Contaminated PPE | Total PAHs reduced to below detection limits in outer shell, membrane, and lining layers | [267] |

| Physical doping using 10 NFPA 1851 compounds | Liquid CO2 cleaning with 50 min cycle at 600 to 850 psi compared with conventional laundering | Fabric swatch | Conventional laundering removed 30.29 to 95.59%. Liquid CO2 removed 89.67 to 98.52% of target compounds | [271] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).