1. Introduction

Tetranychidae Donnadieu 1875 belong to the phylum Arthropoda, subphylum Chelicerata, and class Arachnida. They are mainly plant-dwelling mites, predominantly phytophagous, and very small in size (0.1–0.5 mm), bearing four pairs of legs characterised by four-segmented pedipalps, short claws, and 12–16 pairs of setae on the dorsal shield [

1]. These mites sometimes spin abundant webs, which facilitate their protection against natural enemies and dispersal across plants or fields through the wind or contact between leaves.

The Tetranychidae family currently includes nearly 1,300 described species worldwide, a significant number of which are associated with major economic agroecosystem damage, particularly because the widespread use of insecticides and acaricides has disturbed the balance between pests and beneficial organisms in crops[

1,

2].

In tropical Africa, Tetranychidae have been reported to be present on many food, vegetable, and fruit crops, among which cassava (

Manihot esculenta Crantz) is an important crop. Cassava is a perennial shrub from the Euphorbiaceae family that is mainly cultivated via cuttings and tolerates drought and poor soil fertility, which explains its widespread distribution in areas with food security constraints. Cassava tubers are rich in starch and serve as a source of carbohydrates, whereas the leaves are rich in proteins, vitamins, and minerals [

3]In the RC, cassava tubers and leaves are a staple food for majority of the population and thus play a strategic role in local food security[

4].

Infestations of spider mites on cassava can result in leaf chlorosis, reduced photosynthetic surface area, stunted growth, and ultimately root yield losses that may exceed 80%, causing a significant decrease in the production of cuttings intended for replanting [

5,

6].

Several studies conducted in Central Africa and the RC have reported that at least 13 Tetranychidae species are associated with cassava crops in Africa, including

Tetranychus urticae,

T. kanzawai,

T. gossypii,

T. neocaledonicus,

Mononychellus progresivus,

Oligonychus gossypii, and

O. coffeae. In the RC, research carried out as part of a thesis and a recent publication indicated that seven phytophagous species distributed across four genera are associated with various cassava crops[

7,

8]. For several decades, the identification of these species has been exclusively based on traditional taxonomy, which relies on the observation of distinguishing morphological features. Inter-specific differences mainly concern the structure of the aedeagus, arrangement of the dorsal and ventral setae, and structure of the gnathosoma. The identification of certain species, particularly within the genera

Oligonychus and

Tetranychus, requires simultaneous comparisons of male and female specimens.

In recent years, species characterisation based solely on traditional taxonomy has been gradually replaced by integrative taxonomy [

9,

10]. Indeed, combining morphological, molecular, and sometimes ecological approaches has become an essential tool [

11]for ensuring the reliable identification of numerous species belonging to various arachnid families, such as the Phytoseiidae [

12,

13,

14,

15]. The advent of molecular barcoding, based on the amplification of a standardised fragment (~650 bp) of the 5′-end of the mitochondrial cytochrome

c oxidase I (COI) gene, was proposed as a universal identifier for animals [

16] and represents a revolution in taxonomy, as it has resolved various taxonomic issues and revealed cryptic complexes in many groups [

17,

18,

19].

The COI fragment is particularly well-suited for species delimitation because it possesses several favourable properties: absence of introns, low indel frequency, high mitochondrial copy numbers that facilitate amplification, maternal inheritance without recombination, and a sufficient mutation rate to create a gap between intra- and inter-specific variability, resulting in lower intra-specific genetic divergence [

16,

20]. Currently, COI is no longer the only mitochondrial marker used; other markers, such as 12S, 16S, and CytB [

21,

22], as well as nuclear markers that include 18S and ITS, have been used, leading to the concept of multi-locus barcoding [

13,

15,

23].

In spider mites, studies using ITS2 and biological crosses have confirmed the synonymy between

T. kanzawai and

T. hydrangeae[

24], and COI has clarified the status of 13

Tetranychus species present in Japan [

18], as well as highlighted cases of synonymy and cryptic species in the genus

Oligonychus [

25,

26,

27].

Recently, a study conducted in the RC provided an overview of the diversity of Tetranychidae mites present on cassava crops [

8]. The latest data on the diversity of this family dates back to more than 20 years ago, emphasising the need to update knowledge on this group of mites. The aforementioned study revealed an overrepresentation of the genera

Mononychellus and

Oligonychus, which accounted for nearly 80% of the identified mites. In this context, although significant efforts have been made to inventory local diversity and identify the species present, some methodological limitations remain. Specific identification could not be achieved for two species from

Mononychellus and

Oligonychus because of the lack of taxonomic keys suitable for this geographic area. Furthermore, this was the first observation of

Eutetranychus orientalis in the RC, which is particularly important for understanding the local fauna and could have significant implications for agricultural management and phytosanitary monitoring in the region. Molecular analyses were performed to confirm the status of each species.

Until the present study, no sequences of Tetranychidae collected in the RC had been registered in the GenBank or BOLD databases, which greatly limits the possibilities for phylogenetic comparison and reliable assignment in future studies. This lack of public data contrasts with the strong pressure exerted by mites on cassava crops and the need for rapid identification tools for surveillance and integrated biological control programs. Moreover, the absence of sequences originating from the RC limits the exploration of differentiated lineages or endemic species in local agroecosystems.

The general objective of this study was to confirm the taxonomic status of the mite species identified in our study [

1,

8]through multi-locus barcoding, specifically using COI and ITS. The specific objectives of this study were as follows:

To confirm the taxonomic status (genus and/or species) of the species collected from cassava leaves in the RC;

To compare the genetic divergence of these species from others of the same genus that are available in public reference databases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

Mites were collected from sweet cassava leaves at two distinct sites in Brazzaville over a four-month period. Sampling was randomly conducted within each area, with 40 host plants selected per plot and samples collected across the lower, middle, and upper sections of each plant. The collected leaves consistently showed at least one of the classic signs of Tetranychidae infestation described in the scientific literature: punctiform chlorosis (small yellow spots on the leaf), silvery appearance (general discoloration of the leaf blade), or the presence of webs. These symptoms are recognised as reliable indicators of attacks by phytophagous mites of the Tetranychidae group, thereby optimising the probability of detecting the target organisms. No other eligibility criteria were applied during leaf selection to ensure sampling representativeness.

Immediately after collection, each leaf was placed in a plastic or paper bag and individually labelled with the site name, collection date, and host plant number. The samples were stored in a refrigerator to limit degradation of the leaf tissue. The maximum time between field collection and arrival at the laboratory did not exceed 6 h. This precaution was taken to preserve the integrity of the mites and quality of the subsequent analyses.

2.2. Individual Collection

The mites were individually collected from each host plant using a sterile brush under a binocular microscope (×40 magnification). They were then transferred into 1.5 mL microtubes containing either 70% ethanol for morphological analyses or absolute ethanol for molecular analyses. The samples were then stored at −20 °C.

For each species identified based on their morphological characteristics, representative specimens were selected for molecular analyses.

2.3. DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from each mite using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), with the protocol slightly adapted for microscopic arthropods. Each sample was incubated overnight at 56 °C in 20 µL proteinase K and 180 µL ATL buffer to ensure complete digestion of the chitinous cuticle. After adding AL buffer and 96% ethanol, the lysate was transferred to a silica column and washed twice (AW1 then AW2), whereafter the DNA was eluted in 50 µL preheated AE buffer. The obtained DNA was stored at −20 °C.

2.4. Selected Primers and DNA Amplification

Table 1.

Primers used for amplification and sequencing of 18S rRNA, ITS, and COI markers in Tetranychidae, including primer sequences and references.

Table 1.

Primers used for amplification and sequencing of 18S rRNA, ITS, and COI markers in Tetranychidae, including primer sequences and references.

| Characteristics of the primers selected to amplify each gene fragment are presented in Table 1. The following primers were used: 18SF and 18SR, used for complete amplification of the internal ITS region, and C1J1718 and 773, used to amplify the COI fragment [24,28]. All amplification reactions were performed in a final volume of 25 µL. The samples were initially denatured at 94 °C for 3 min. PCR was then performed for 35 cycles, with 1 min of denaturation at 94 °C, followed by 1 min of annealing at 51 °C for each sample. The final extension was carried out at 72 °C for 1.5 min, and the PCR products subsequently visualised on a 1% agarose gel saturated with ethidium bromide.Gènes |

Taille (pb) |

Position |

Amorces |

Référence |

Séquences nucléotidiques |

| |

|

3’de 18S |

18S |

Ben et al.2000 |

5’-AGAGGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAG-3’ |

ITS |

1200 |

5’de 28S |

18SR |

Navajas et al.1998 |

5’-ATATGCTTAAATTCAGCGGG-3’ |

| |

|

5.8S |

Inter S |

Navia et al.2005 |

5’-GATCACTCGAATTACCAATCG-3’ |

| |

|

5.8S |

Inter Rev |

Navia et al.2005 |

5’-CGATTGGTAATTCGAGTGATC-3’ |

| |

|

|

C1J1718 |

Simon et al.1994 |

5’-GGAGGATTTGGAAATTGATTAGTTCC -3’ |

COI

|

890 |

COI

|

773

Inter COI |

Navia et al.1994

this study |

5’-TACAGCTCCTATAGATAAAAC -3’

5’- GGNGANCCTATTTTATATCAAC -3’ |

| |

|

|

Inter Rev |

this study |

5’- GTTGATATAAAATAGGNTCNCC -3’ |

2.5. Sequencing, Correction and Processing of Chromatograms: Obtaining Consensus Sequences

PCR products were purified using ExoSAP-IT and then sequenced in both directions (5′–3′ and 3′–5′) by the MACROGEN Europe platform. Chromatograms (.ab1) were processed using Geneious Prime v.2019.2.1. After removing low-quality regions (Q <20), forward and reverse sequences were assembled into contigs, manually inspected for ambiguities, and then exported in FASTA format.

2.6. NCBI BLAST

The consensus sequences were compared against public databases using the BLASTn tool available on the NCBI website. Searches were performed in the core_nt database using the MegaBLAST algorithm (optimised for highly similar sequences). Default BLASTn parameters were used (word size = 28, match/mismatch scores = 1/−2; linear gap penalty), with an E-value threshold set at 0.005 and maximum of 100 target sequences returned. A filter for low-complexity regions was applied, and sequences derived from environmental or uncultured samples excluded from the analysis. Identification at the species level was accepted when the percentage identity was ≥97–98% and the alignment coverage >90%.

2.7. Methodology for Data Collection from GenBank

The sequences selected from public databases to calculate intra- and inter-specific divergences met the following eligibility criterion: number of base pairs = 800 bp, as the expected amplicon sizes were 890 bp for the COI fragment and 1,200 bp for the ITS fragment.

For the GenBank database, the chosen sequences were of those among the top 100 sequences derived from the MegaBLAST analysis that shared 100% coverage with the consensus sequences, with a percentage identity of at least 86% at the genus level and at least 97% at the species level.

For the BOLD database, the molecular identification of individuals was carried out using the BOLD Identification Engine (BOLD Systems) by querying the ANIMAL LIBRARY (PUBLIC) database, which contains non-redundant COI sequences of at least 500 bp in the standard barcode region (648 bp; COI-5P marker, ~9.1 million sequences). The obtained sequences were submitted in Rapid Species Search mode, with a minimum similarity threshold set at 94%, maximum of 25 matches (hits) per sequence, and maximum submission of 1,000 sequences per analysis.

2.8. Multiple Sequence Alignment

Multiple sequence alignment is defined as the sequential arrangement of two or more DNA nucleotide sequences to highlight regions of similarity. In this study, a multiple alignment was performed between the obtained sequences and 18 sequences from the Tetranychidae family selected from the GenBank database. These sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE multiple alignment procedure [

29]in MEGA12 software with the following parameters: gap opening = 15, gap extension = 6.66, and transition weight = 0.5. The absence of indels, frameshifts, and stop codons was also verified [

30]

2.9. Nucleotide Evolution Models, Genetic Divergence, and Phylogenetic Tree

Evolutionary models are used to estimate evolutionary distances and assess the relationships between species. Twenty-four evolutionary models were tested on all the analysed sequences. Pairwise genetic divergences (intra- and inter-specific variability) were estimated among all selected sequences using the Compute Pairwise Distances function in MEGA12 software [

30]The maximum threshold value used to assign sequences to the species rank for mitochondrial DNA (COI gene) was set at a 3% genetic divergence, as commonly proposed in molecular barcoding studies [

31]As no universal threshold exists for nuclear markers, species limits based on nuclear DNA were evaluated on a case-by-case basis, relying on consistency with morphological and phylogenetic data. Phylogenetic analysis of the relationships among various species was performed using the Maximum Likelihood method. The following parameters were applied: insertion of the best model, rate of heterogeneities using a gamma distribution and proportion of invariant sites, heuristic search, and 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Finally,

Phytoseiulus persimilis, belonging to the Phytoseiidae family, was added to the analysis as an outgroup to root the phylogenetic tree.

3. Results

3.1. Amplification Rate

Among the 12 DNA extracts sent to the MACROGEN laboratory in Amsterdam, we obtained only three sequences with the COI fragment (25% amplification rate), as the fragments of the ITS gene could not be amplified and sequenced (Data available).

3.2. BOLD Blast

Each consensus sequence analyzed with the BOLD Identification Engine best matched the GMGGA475-170 specimen (linked to BIN BOLD:ADJ5228), which belongs to the family Tetranychidae (Arthropoda, Arachnida, Trombidiformes). This match showed a nucleotide identity of 98.36% without insertions or deletions. As no genus or species designation is currently associated with this BIN in BOLD, identification of the studied specimens can only be reliably made at the family (and BIN) level.

Specimen GMGGA475-17 corresponds to a specimen that had been collected in Gabon, Lopé National Park (Rocher du Miel sector, savanna habitat, 240 m altitude; 0.16524° S, 11.617° E), using a Malaise trap between 29 August and 5 September 2014 (collector: Thibaud Decaens).

3.3. GenBank Blast

Each consensus sequence in the GenBank database best matched the specimen, O. biharensis, which belongs to the family Tetranychidae (Arthropoda, Arachnida, Trombidiformes), with 100% coverage and 86% identity.

3.4. Submission of Sequences to GenBank

The three COI sequences were submitted via BankIt with the following metadata: organism = Oligonychus sp. (due to the absence of a clear species-level identification); organelle = mitochondrion; molecule type = genomic DNA; isolate = 5; host = Manihot esculenta; db_xref = taxon:3064715; geographic location = Republic of the Congo: Brazzaville; collection date = 28-Jun-2021; and collected by = Benie Germine Jessica LOUZEYMO (species-level identification was not possible based on the available evidence)

Each sequence was referenced according to the following coding: PX672268, PX672269 and PX672270

3.5. Total Data

The sequences chosen for comparative analyses are listed in Table 2, along with information on their length, percentage of coverage, and identity. Overall, a total of 20 mitochondrial COI gene sequences were used for the comparative analysis, including (i) three novel Congolese sequences generated in this study (H210414-025 A07 5 2 773.ab1, H210414-025 M05 3 2 773.ab1, and H210414-025 C07 16 2 CIJ1718.ab1); (ii) a sequence obtained from the BOLD platform (GMGGA475-17 BOLD ADJ5228); and (iii) 18 sequences derived from GenBank, representing several major genera of Tetranychidae (Tetranychus, Oligonychus, and Panonychus). A representative of the predatory mite, Phytoseiulus persimilis (Phytoseiidae), was used as an outgroup. The final alignment length was 658 bp after eliminating ambiguous positions and standardising reading frames.

3.6. General Characteristics of the COI Alignment

The final alignment contained 658 nucleotide sites, including 214 variable and 178 parsimony-informative sites. The estimated transition/transversion ratio for the entire dataset was 2.31. Polymorphic positions were unevenly distributed among the three codon positions, with a high concentration observed at the third codon site.

3.7. Selection of the Best-Fitting Nucleotide Substitution Model

Model selection based on Maximum Likelihood analysis indicated that the GTR+G+I model provided the best fit to the COI dataset, as supported by the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC = 8332.73) and corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc = 7939.20) values. This model accounts for unequal base frequencies, different substitution rates, rate heterogeneity among sites, and a proportion of invariant sites. The estimated gamma shape parameter was 0.75, and the proportion of invariant sites was 0.44. Alternative models lacking either gamma-distributed rate variation or invariant sites showed substantially higher BIC and AICc values, indicating poorer fit to the data.

3.8. Intra- and Inter-group Genetic Divergence

The genetic distances calculated are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The analysis of genetic distances (p-distance, COI gene) showed structural divergence levels both within the reference species and local sequences. The three local sequences (H210414-025 A07, C07, and M05) displayed a low intra-group divergence (average = 1.0%, min–max = 0–1.9%). The BOLD sequence, GMGGA475-17, which grouped with the three local sequences, showed similar distances close to 0%, further supporting the coherence of this local cluster.

Among the reference species, intra-specific divergence was zero for T. cinnabarinus, T. evansi, and Pa. ulmi (0.0%), whereas T. urticae showed moderate variability (average = 2.1%; min–max = 0–3.1%). A slightly higher intra-specific divergence was observed for O. biharensis (average = 3.1%; min–max = 0–4.7%).

Inter-specific distances were significantly higher. Sequences from the RC showed an average divergence of approximately 12% when compared to the reference sequences of O. biharensis (individual values ≈ 0.119–0.120), and up to 17.8% for the comparison between the GMGGA475-17 BOLD sequence and O. biharensis. These values are much higher than the observed intra-specific divergence in O. biharensis (≈3%) and intra-cluster variability of the local group (≈1%), supporting the likely existence of two genetically distinct entities. Generally, distances among the main Tetranychus species range from 7–11%, whereas divergences between genera (for example, between local sequences and O. biharensis, or between Tetranychus and Panonychus/Eotetranychus) reach 13–18%.

These results highlight the lack of overlap between intra- and inter-group variation for both the reference species and local sequences. The low level of intra-specific divergence and large distances from other Oligonychus species available in the databases suggest that the local cluster represents a distinct lineage.

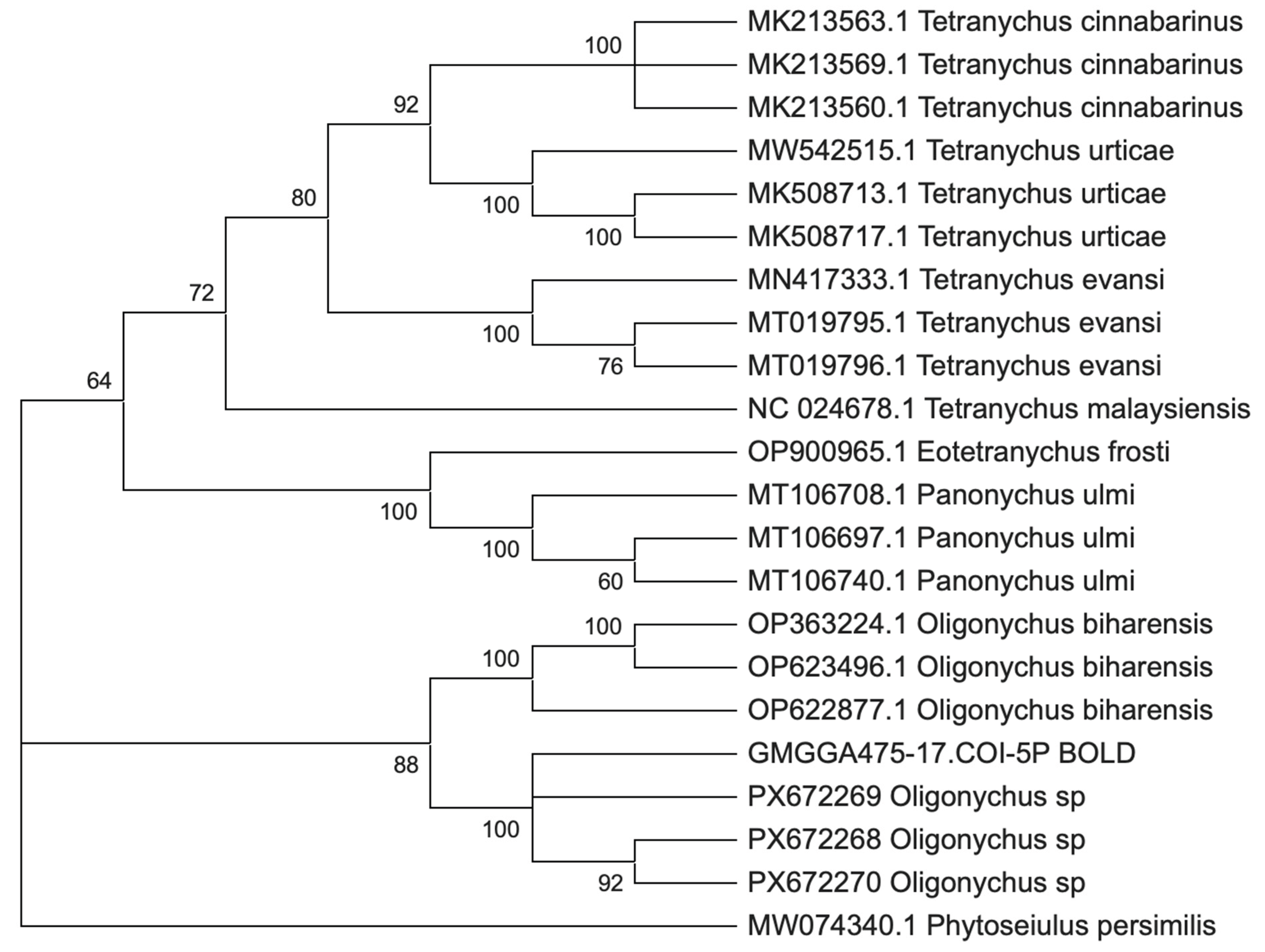

3.9. Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis (

Figure 1) using Maximum Likelihood (COI) revealed well-resolved clades corresponding to the main Tetranychidae species. The sequences of

T. cinnabarinus,

T. urticae,

T. evansi, and

Pa. ulmi each formed strongly supported monophyletic clades (BS = 92–100%). Similarly, the three

O. biharensis sequences were grouped together in a perfectly resolved clade (BS = 100%).

The three Congolese sequences derived from cassava formed a strongly supported monophyletic clade (BS = 100%), within which internal relationships were strongly resolved (BS = 92%). A related BOLD sequence (GMGGA475-17) was recovered as sister to the Congolese clade, and this assemblage clustered with Oligonychus biharensis with high bootstrap support (BS = 88%), indicating phylogenetic affinity between the lineages, although their species-level relationship could not be resolved with COI alone. Combined with the high COI genetic distance between the Congolese lineage and O. biharensis (~14%, see Table S1), this topology supports the presence of a genetically distinct Oligonychus lineage not represented among the currently available reference sequences.

4. Discussion

Molecular identification of pest mites is a major challenge in tropical agriculture, especially in regions where taxonomic studies are rare, and the actual mite diversity remains largely underestimated. In this study, use of the mitochondrial COI gene enabled the characterisation of phytophagous mite samples collected in the RC for the first time, even though only three of the 12 specimens collected yielded successful amplification and usable sequencing data. This low success rate limits the representativeness of the results and highlights the need to optimise extraction protocols. The lack of successful amplification with ITS markers, which are commonly used in Tetranychidae systematics, is also an important aspect to discuss, both in terms of methodological limitations and the possible biological peculiarities of the samples. This failure could be explained by DNA degradation, significant divergence of target sequences among local populations, or the presence of inhibitors in the DNA extracts.

Overall, the molecular results revealed relatively low genetic divergence (from 0–0.89%) between the three Congolese sequences and a sequence obtained from the BOLD database, which were all grouped into a homogeneous clade assigned to the genus Oligonychus but without a clear match with any described species. For example, the genetic distance between the Congolese sequences and O. biharensis was approximately 12%, which far exceeds the generally accepted threshold of 2–3% for species delimitation within Tetranychidae. At the same time, the genetic distances separating this group from reference taxa (notably O. biharensis, O. thelytokus, and species from the genera Tetranychus and Panonychus) appeared to be consistent with a level of inter-specific divergence, often between 10 and 20%. These findings suggest that the Congolese specimens could represent a distinct species closely related to O. biharensis or a potentially as-of-yet undescribed lineage. This discovery highlights the little-known diversity of the genus Oligonychus in Central Africa and underscores the importance of continuing taxonomic investigations in this region.

The phylogenetic tree showed that the three Congolese sequences grouped with the corresponding BOLD sequence and formed a distinct, strongly supported subclade that was clearly separated from O. biharensis, despite the apparent phylogenetic proximity of the latter species. Genetic divergence between the Congolese sequences and O. biharensis was high (approximately 12–15%), suggesting a marked genetic isolation. In Tetranychidae mites, previous studies based on the mitochondrial COI gene have shown that intra-specific distances are generally low (often <3%) but can reach 4–6% within the same species, as reported for T. urticae, in which two major lineages differ by approximately 5% (Matsuda et al. 2014; Navajas et al. 1994; Ros & Breeuwer 2007). In contrast, inter-specific distances observed between species of the genus Tetranychus and other Tetranychidae are more frequently in the range of 6–13%, although these values can vary between groups, and no universal threshold for species delimitation is recognised (İnak et al. 2022; de Mendonça et al. 2011b). In practice, this means that a genetic distance interval that clearly separates intra-specific from inter-specific variation often exists, known as the “barcoding gap.”

In the absence of convincing matches with sequences available in the GenBank and BOLD databases, and when considering the high divergence rate observed with O. biharensis—a polyphagous species widely reported in Asia and Africa—the RC specimens likely do not belong to this species. Furthermore, the low variability in the COI sequence of O. biharensis among the different populations analysed reinforces this interpretation. Therefore, the Congolese specimens likely do not represent an undescribed species or may belong to a complex of cryptic species within the genus Oligonychus, a phenomenon well documented in Tetranychidae, where strong morphological similarity can mask underlying genetic diversity (Navajas et al. 1998). This hypothesis is more credible because several recent studies have highlighted the limitations of approaches that are based solely on COI in Tetranychidae. For example, Matsuda et al. (2014) showed that phylogenies based only on COI are often poorly resolved and sometimes incongruent with morphological taxonomy, necessitating the re-evaluation of diagnostic characteristics (Matsuda et al. 2014). Similarly, Boubou et al. (2012) demonstrated the presence of highly divergent mitochondrial lineages and admixture events between lineages of T. evansi, illustrating that complex introgression and invasion scenarios can obscure interpretations based on mitochondrial data alone (Boubou et al. 2012). A critical analysis of these studies suggests that to confirm the discovery of a new species or cryptic complex, adopting an integrative taxonomic approach that combines morphological, ecological, and nuclear marker data is necessary.

Firstly, the samples studied likely belong to a known mite species absent from molecular databases, a situation frequently encountered in Central Africa, where the lack of genetic data recorded in international databases is glaring. For example, recent research on the genus

Oligonychus showed that only a fraction of described species has sequence data available, particularly for African populations, which greatly limits the possibilities for precise identification and phylogenetic comparison [

25,

27]Secondly, the hypothesis of a possible cryptic species is consistent with numerous studies showing that several species of the genus

Oligonychus, including the

O. coffeae complex, display marked genetic structuring despite having strong morphological homogeneity, suggesting the existence of cryptic lineages or sister species that are difficult to distinguish based solely on morphology [

25,

27]Similarly, studies conducted on the genus

Tetranychus have highlighted deeply divergent mitochondrial lineages within nominal species, such as

T. urticae [

32]and owing to barcoding, have confirmed the existence of cryptic species within the genus [

33] Thirdly, examples from other regions of the world demonstrate that targeted collection and sequencing campaigns can reveal unsuspected diversity among Tetranychidae. Recent revisions of the genus

Oligonychus have led to the description of new species and identification of species complexes based on integrative approaches that combine morphology and molecular markers [

25,

26,

27,

34]. This observation supports the strengthening of sampling and sequencing efforts in Central Africa to enrich existing databases and better document the true species richness of pest mites in this region.

4.1. Failure to Amplify ITS: Implications and Hypotheses

Despite their widespread use in mite systematics, the failure to amplify ITS markers can be explained by several factors. Firstly, technical limitations related to DNA quality (degradation, fragmentation, and presence of inhibitors) can affect longer nuclear markers, in contrast to mitochondrial COI, which is generally more robust [

35,

36]). Secondly, several studies have shown a high degree of divergence in ITS sequences, especially ITS2, between Tetranychidae species, which limits the effectiveness of truly “universal” primers and often requires the use of genus- or species-group-specific primers [

37,

38,

39]). Recent studies have demonstrated that ITS regions display high inter-specific variability, sometimes accompanied by significant intra-population variation, compromising their amplification or alignment [

27,

40]. Thirdly, ITS regions are multicopy, and several divergent copies may coexist within a single individual. This absence of concerted evolution, as documented in recent methodological reviews, frequently leads to non-specific amplification or a lack of usable amplicons [

41].

Thus, the failure of ITS does not call into question the results obtained with COI but rather indicates that a multi-locus approach that includes more stable nuclear markers (28S, EF-1α), or the use of region-specific primers, will be necessary to consolidate the molecular characterisation of African-origin Tetranychidae mites.

4.2. Study Limitations

Nonetheless, this study had several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. Firstly, the small number of COI sequences obtained reduced the representativeness of the sampling and did not reflect the real diversity of all populations present. Secondly, the absence of ITS marker amplification prevented the construction of a multi-locus phylogeny, which is essential for distinguishing closely related species and confirming the possible existence of a cryptic complex. Thirdly, the incompleteness of molecular databases for African species limits their identification accuracy.

These limitations do not invalidate the results obtained but rather indicate that they should be consolidated using complementary approaches.

5. Conclusions

Molecular analyses based on COI suggested the presence of an Oligonychus lineage in the RC that is distinct from species data stored in known reference databases, suggesting the existence of an unreferenced, new, or cryptic species complex. This discovery is of major agronomic interest and highlights the need to strengthen the completeness of international public databases with sequences originating from under-sampled regions. For the first time, DNA sequences of the Tetranychidae family collected from the RC were recorded in international public databases. These data will not only improve the reliability of identifying Tetranychidae species originating from the RC but also help develop suitable tools for monitoring these pests. These advances could open major scientific prospects for strengthening future biological control strategies and contributing to better crop protection in the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B.M.O.; Methodology, M.B.M.O.; Software, M.B.M.O. and B.G.J.L.; Validation, M.B.M.O. and A.L.; Formal analysis, M.B.M.O.; Investigation, B.G.J.L.; Resources, B.G.J.L.; Data curation, B.G.J.L.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.B.M.O.; Writing—review and editing, M.B.M.O.; Visualization, M.B.M.O.; Supervision, M.B.M.O.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Use of Generative AI

During the preparation of this study, the authors used an artificial intelligence tool to generate the graphical abstract. The authors reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Data Availability Statement

The nucleotide sequences generated in this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers: PX672268, PX672269 and PX672270. The raw sequencing chromatograms and original files received from Macrogen are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the local market gardeners/farmers in Brazzaville for providing access to their fields and facilitating cassava leaf sampling. We also thank all individuals who contributed to field logistics and sample handling.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COI |

Cytochrome c oxidase I |

| RC |

Republic of Congo |

References

- Bolland, H.; Gutierrez, J.; Flechtmann, C. World Catalogue of the Spider Mite Family (Acari: Tetranychidae). 1998.

- Migeon, A.; Nouguier, E.; Dorkeld, F. Spider Mites Web: A Comprehensive Database for the Tetranychidae. Trends Acarol. 2011, 557–560.

- Montagnac, J.A.; Davis, C.R.; Tanumihardjo, S.A. Nutritional Value of Cassava for Use as a Staple Food and Recent Advances for Improvement. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2009, 8, 181–194. [CrossRef]

- In FAO Save and Grow: Cassava: A Guide to Sustainable Production Intensification; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; ISBN 978-92-5-107641-5. 4. FAO Save and Grow: Cassava: A Guide to Sustainable Production Intensification; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; ISBN 978-92-5-107641-5.

- Ezenwaka, L.; Del Carpio, D.P.; Jannink, J.-L.; Rabbi, I.; Danquah, E.; Asante, I.; Danquah, A.; Blay, E.; Egesi, C. Genome-Wide Association Study of Resistance to Cassava Green Mite Pest and Related Traits in Cassava. Crop Sci. 2018, 58, 1907–1918. [CrossRef]

- Ezenwaka, L.; Rabbi, I.; Onyeka, J.; Kulakow, P.; Egesi, C. Identification of Additional /Novel QTL Associated with Resistance to Cassava Green Mite in a Biparental Mapping Population. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0231008. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, J.; Bonato, O. Les Acariens Tetranychidae Attaquant Le Manioc Au Congo et Quelques-Uns de Leurs Prédateurs. Rev. Zool. Afr. 1994, 108, 191–200.

- Belle Mbou Okassa, M.; Louzeymo, J.B.; Nianga Bikouta, G.; Lenga, A. Diversité Des Acariens Ravageurs de La Famille Des Tetranychidae Présents Sur Manihot Esculenta Dans La Commune de Brazzaville : État Des Lieux et Perspectives. Rev. Afr. D’Environnement D’Agriculture 2024, 7, 136–142. [CrossRef]

- Dayrat, B. Towards Integrative Taxonomy. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2005, 85, 407–415. [CrossRef]

- Padial, J.M.; Miralles, A.; De la Riva, I.; Vences, M. The Integrative Future of Taxonomy. Front. Zool. 2010, 7, 16. [CrossRef]

- Schlick-Steiner, B.C.; Steiner, F.M.; Seifert, B.; Stauffer, C.; Christian, E.; Crozier, R.H. Integrative Taxonomy: A Multisource Approach to Exploring Biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010, 55, 421–438. [CrossRef]

- Okassa, M.; Tixier, M.-S.; Kreiter, S. Morphological and molecular diagnostics of Phytoseiulus persimilis and Phytoseiulus macropilis (Acari: Phytoseiidae. Exp Appl Acarol 2010, 52, 291–303.

- Okassa, M.B.M.; Ntabi, D.M.; Lenga, A. Morphological and Molecular Identification of Specimens in the Genus Euseius (Acari: Phytoseiidae) from the Republic of Congo. Zootaxa 2020, 4768, 479–498. [CrossRef]

- Tixier, M.-S.; Kreiter, S.; Barbar, Z.; Ragusa, S.; Cheval, B. Status of two cryptic species, Typhlodromus exhilaratus Ragusa and Typhlodromus phialatus Athias-Henriot (Acari: Phytoseiidae): consequences for taxonomy. Zool Scr 2006, 35, 115–122.

- Tixier, M.-S.; Auger, P.; Migeon, A.; Douin, M.; Fossoud, A.; Navajas, M.; Arabuli, T. Integrated Taxonomy Supports the Identification of Some Species of Phytoseiidae (Acari: Mesostigmata) from Georgia. Acarologia 2021, 61, 824–844. [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Ratnasingham, S.; deWaard, J.R. Barcoding Animal Life: Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit 1 Divergences among Closely Related Species. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, S96–S99. [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Penton, E.H.; Burns, J.M.; Janzen, D.H.; Hallwachs, W. Ten Species in One: DNA Barcoding Reveals Cryptic Species in the Neotropical Skipper Butterfly Astraptes Fulgerator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 14812–14817. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, T.; Fukumoto, C.; Hinomoto, N.; Gotoh, T. DNA-Based Identification of Spider Mites: Molecular Evidence for Cryptic Species of the Genus Tetranychus (Acari: Tetranychidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2013, 106, 463–472. [CrossRef]

- Chan-Chable, R.J.; Martínez-Arce, A.; Mis-Avila, P.C.; Ortega-Morales, A.I. DNA Barcodes and Evidence of Cryptic Diversity of Anthropophagous Mosquitoes in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 4692–4705. [CrossRef]

- Ballard, J.W.O.; Whitlock, M.C. The Incomplete Natural History of Mitochondria. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 729–744. [CrossRef]

- Okassa, M.; Tixier, M.-S.; Cheval, B.; Kreiter, S. Molecular and Morphological Evidence for a New Species Status within the Genus Euseius (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Can. J. Zool. 2009, 87, 689–698. [CrossRef]

- Tixier, M.-S.; Okassa, M.; Kreiter, S. An Integrative Morphological and Molecular Diagnostic for Typhlodromus Pyri (Acari: Phytoseiidae). Zool. Scr. 2012, 41, 68–78. [CrossRef]

- Tixier, M.-S.; Hernandes, F.A.; Guichou, S.; Kreiter, S. The Puzzle of DNA Sequences of Phytoseiidae (Acari : Mesostigmata) in the Public GenBank Database. Invertebr. Syst. 2012, 25, 389–406. [CrossRef]

- Navajas, M.; Gutierrez, J.; Williams, M.; Gotoh, T. Synonymy between Two Spider Mite Species, Tetranychus Kanzawai and T. Hydrangeae (Acari: Tetranychidae), Shown by Ribosomal ITS2 Sequences and Cross-Breeding Experiments. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2001, 91, 117–123.

- Mushtaq, H.M.S.; Alatawi, F.J.; Kamran, M.; Flechtmann, C.H.W. The Genus Oligonychus Berlese (Acari, Prostigmata, Tetranychidae): Taxonomic Assessment and a Key to Subgenera, Species Groups, and Subgroups. ZooKeys 2021, 1079, 89–127. [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, H.M.S.; Kamran, M.; Saleh, A.A.; Alatawi, F.J.; Mushtaq, H.M.S.; Kamran, M.; Saleh, A.A.; Alatawi, F.J. Evidence for Reconsidering the Taxonomic Status of Closely Related Oligonychus Species in Punicae Complex (Acari: Prostigmata: Tetranychidae). Insects 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, H.M.S.; Saleh, A.A.; Kamran, M.; Alatawi, F.J. Molecular-Based Taxonomic Inferences of Some Spider Mite Species of the Genus Oligonychus Berlese (Acari, Prostigmata, Tetranychidae). Insects 2023, 14, 192. [CrossRef]

- de Mendonça, R.S.; Navia, D.; Diniz, I.R.; Auger, P.; Navajas, M. A Critical Review on Some Closely Related Species of Tetranychus Sensu Stricto (Acari: Tetranychidae) in the Public DNA Sequences Databases. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2011, 55, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple Sequence Alignment with High Accuracy and High Throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis Version 12 for Adaptive and Green Computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Cywinska, A.; Ball, S.L.; deWaard, J.R. Biological Identifications through DNA Barcodes. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 313–321. [CrossRef]

- Navajas, M.; Lagnel, J.; Gutierrez, J.; Boursot, P. Species-Wide Homogeneity of Nuclear Ribosomal ITS2 Sequences in the Spider Mite Tetranychus Urticae Contrasts with Extensive Mitochondrial COI Polymorphism. Heredity 1998, 80, 742–752. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, T.; Fukumoto, C.; Hinomoto, N.; Gotoh, T. DNA-Based Identification of Spider Mites: Molecular Evidence for Cryptic Species of the Genus Tetranychus (Acari: Tetranychidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2013, 106, 463–472. [CrossRef]

- Knihinicki, D.K.; Flechtmann, C.H. A New Species of Spider Mite, Oligonychus Calicicola (Acari: Tetranychidae), Damaging Date Fruit, Phoenix Dactylifera L. (Arecaceae), in Australia. Aust. J. Entomol. 1999, 38, 176–178. [CrossRef]

- Krehenwinkel, H.; Fong, M.; Kennedy, S.; Huang, E.G.; Noriyuki, S.; Cayetano, L.; Gillespie, R. The Effect of DNA Degradation Bias in Passive Sampling Devices on Metabarcoding Studies of Arthropod Communities and Their Associated Microbiota. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0189188. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sayas, C.; Pina, T.; Sabater-Muñoz, B.; Gómez-Martínez, M.A.; Jaques, J.A.; Hurtado-Ruiz, M.A. DNA Barcoding and Phylogeny of Acari Species Based on ITS and COI Markers. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2022, 2022, 5317995. [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, T.; Melamed, S.; Gerson, U.; Morin, S. ITS2 Sequences as Barcodes for Identifying and Analyzing Spider Mites (Acari: Tetranychidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2007, 41, 169–181. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, T.; Hinomoto, N.; Singh, R.N.; Gotoh, T. Molecular-Based Identification and Phylogeny of Oligonychus Species (Acari: Tetranychidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2012, 105, 1043–1050. [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Khaing, T.M.; Seo, H.; Ahn, J.; Jung, D.; Lee, J.; Lee, K. Development of Species-specific Primers for Rapid Diagnosis of T Etranychus Urticae , T. Kanzawai , T. Phaselus and T. Truncatus ( A Cari: T Etranychidae). Entomol. Res. 2016, 46, 162–169. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, T.; Kozaki, T.; Ishii, K.; Gotoh, T. Phylogeny of the Spider Mite Sub-Family Tetranychinae (Acari: Tetranychidae) Inferred from RNA-Seq Data. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0203136. [CrossRef]

- Razuvaeva, A.V.; Ulyanova, E.G.; Skolotneva, E.S.; Andreeva, I.V. Species Identification of Spider Mites (Tetranychidae: Tetranychinae): A Review of Methods. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2023, 27, 240–249. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).