1. Introduction

Mechanical circulatory support, whether as durable long-term therapy, bridge to transplantation, or bridge to recovery, has become an integral component in the management of advanced heart failure [

1]. Over the past decade, substantial technological advances have markedly improved the durability and reliability of contemporary left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) [

2]. Together with refined patient selection and the implementation of structured follow-up programs, these developments have led to a reduction in device-related complications and, consequently, to a significant improvement in long-term survival among patients supported with durable LVADs.

As a result, a growing number of patients supported by LVADs require long-term outpatient care and increasingly present not only to implanting centers but also to non-specialized hospitals and outpatient clinics with acute cardiac or extracardiac conditions. In these settings, urgent questions frequently arise regarding device function, cardiac performance, and hemodynamic stability. Echocardiography remains the most readily available and widely used imaging modality for assessing cardiac function and the interaction between the heart and the LVAD in this patient population.

Importantly, the vast majority of echocardiographic examinations in LVAD patients are performed in the context of routine ambulatory follow-up or during non–device-related hospital admissions. These examinations differ fundamentally from perioperative or early postoperative assessments and are typically conducted outside highly specialized LVAD programs. Accordingly, the focus is on standardized evaluation of cardiac structure, ventricular loading, valve function, and device–heart interaction under stable support conditions, rather than on complex decision-making scenarios such as assessment of myocardial recovery, candidacy for LVAD explantation, or planning of interventional treatment strategies (e.g., for aortic valve insufficiency).

However, echocardiography in LVAD patients is technically demanding. Standard imaging windows—particularly apical views—are frequently compromised by the presence of the inflow cannula at the LV apex and by device-related artifacts. As a result, conventional echocardiographic parameters may be difficult to acquire, poorly reproducible, or misleading if interpreted outside the specific hemodynamic context of mechanical circulatory support. Alternative imaging approaches, including off-axis parasternal views or transhepatic windows, have been proposed and may improve visualization of ventricular size and function, albeit often at the expense of temporal resolution.

Adjustment of LVAD support profoundly influences cardiac structure and function. Pump speed and loading conditions affect left ventricular unloading and reverse remodeling, aortic valve opening patterns, the development of clinically relevant aortic regurgitation, and right ventricular performance. In this setting, echocardiography is the primary diagnostic tool for longitudinal follow-up and plays a central role in guiding routine device optimization and medical therapy.

Given these challenges and the growing number of patients requiring longitudinal assessment, there is a critical need for a standardized, comprehensive, and reproducible echocardiographic protocol tailored to LVAD physiology. The aim of this paper is to provide a practical framework for routine ambulatory and inpatient echocardiographic assessment in patients with durable LVAD support, integrating standardized image acquisition and documentation with a structured interpretation of common pathological findings and device-related complications encountered in everyday clinical practice.

2. Basic Principles of LVAD-Hemodynamics

Durable LVADs withdraw blood from the left ventricle and deliver it into the ascending aorta, thereby partially or fully bypassing native LV ejection. Contemporary devices provide no direct support to the right ventricle; therefore, adequate right ventricular (RV) function is mandatory to maintain left ventricular (LV) preload and effective LVAD flow.

LVAD performance is determined by:

Pump speed

Preload (RV function, volume status, pulmonary circulation)

Afterload (systemic vascular resistance, arterial pressure)

Displayed LVAD flow is an estimated value, derived from pump speed, power consumption, and blood viscosity, and does not represent a direct volumetric measurement. Consequently, echocardiographic assessment of ventricular size, septal position, valve function, and forward stroke volumes is indispensable for physiological interpretation of LVAD parameters.

Changes in pump speed directly affect intracardiac pressures [

3]. Increasing rotor speed reduces LV pressure and promotes unloading, often preventing aortic valve opening. Excessive unloading may result in leftward septal shift, impaired RV geometry, worsening tricuspid regurgitation, and RV failure. Conversely, inadequate unloading or increased afterload leads to elevated LV and left atrial pressures, pulmonary congestion, rightward septal shift, and secondary RV deterioration.

Understanding these interactions between the device and the native heart is fundamental for correct echocardiographic interpretation in LVAD patients.

3. Parameters Displayed on the LVAD Console and Their Interpretation

The LVAD console displays the following parameter:

Rotation per minute (RPM) refers to the speed the LVAD is working, higher rpm ensures higher blood flow, runs from 3000 – 9000 rpm in HeartMate 3™ devices.

Watt refers to the energy use of the LVAD, it is important parameter to look at as changes in the energy consumption may reflect pre-, intra- or post pump flow obstructions [

4].

LVAD Flow is an estimated parameter derived from pump-specific algorithms based on rotor speed, power consumption, and the patient’s hematocrit. Typical flow values range from approximately 3.0 to 6.0 L/min.

Pulsatility Index (PI) evaluating the device's performance and the patient's hemodynamic status. A higher PI indicates more pulsatile flow, which is generally associated with better cardiac function, while a lower PI may suggest less effective circulation or potential complications

4. Standardized Imaging Protocol

Echocardiographic evaluation in patients supported by mechanical circulatory support should follow a standardized approach. Such standardization is essential to improve reproducibility and to reliably document temporal changes during mechanical support. Only a structured and standardized assessment enables meaningful longitudinal comparisons and provides the basis for informed long-term device optimization and medical therapy in mechanical circulatory support (MCS) patients.

The imaging protocol should be grounded in the chamber quantification recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging [

5], as well as in current consensus statements on multimodality imaging in patients with left ventricular assist devices and temporary mechanical support [

6]. Serial echocardiography plays a central role not only in monitoring cardiac reverse remodeling [

7], but also in assessing the potential for myocardial recovery and candidacy for LVAD weaning [

8,

9].

In every standardized examination, the type of LVAD, pump speed, estimated LVAD flow, pulsatility index, and blood pressure (mean arterial pressure in the absence of pulsatile flow) should be documented.

The following sections outline the key echocardiographic views and measurements and describe their interpretation in context.

4.1. Parasternal View

Parasternal imaging of the heart is of particular importance in echocardiographic evaluation of patients with LVADs. While orthogonal apical imaging is often impeded by the device, parasternal image quality is usually preserved and allows for a wide range of views and measurements. The following echocardiographic views and recordings are recommended.

Parsternal long axis view (2D, video)

Parasternal long axis view (color doppler aortic + mitral valve, video)

Parasternal long axis view (M-mode of the aortic valve)

RV inflow view (2D, video)

RV inflow view (color doppler tricuspid valve, video)

-

Parasternal short axis view:

- ○

Mitral valve level (video)

- ○

Mid-papillary level (video)

- ○

Aortic valve level (video)

- ○

Aortic valve Level (color doppler aortic valve, video)

- ○

Aortic valve level (color doppler pulmonary valve, video)

- ○

Aortic valve level (pw-doppler right ventricular outflow tract, video)

- ○

Aortic valve level (color doppler tricuspid valve, video)

- ○

Aortic valve level (cw-doppler tricuspid valve, video)

4.2. Apical View

The device is positioned at the apex and usually prevents acquisition of the classic apical four-chamber view of the heart. Instead, imaging from a more apical position using a slightly modified or foreshortened four-chamber approach is often feasible. This perspective is not suitable for volumetric assessment of the left ventricle. However, the mitral valve, tricuspid valve, and the free wall of the right ventricle can usually be visualized and assessed reliably. The two-chamber and three-chamber views are often only obtainable in a highly modified form and are usually of limited diagnostic value. Orthograde alignment of the aortic valve or the left ventricular outflow tract with spectral Doppler is generally not achievable. However, color Doppler imaging may still provide useful information. The following echocardiographic views and recordings are recommended.

Apical four chamber view (2D, video)

Apical four chamber view (color doppler mitral valve, video)

Right ventricular focused four chamber view (2D, video)

Right ventricular focused four chamber view (color doppler tricuspid valve, video)

Right ventricular focused four chamber view (cw-doppler tricuspid valve, video)

4.3. Subcostal View

The subcostal view is essential for assessment of the size and respiratory variability of the inferior vena cava. In this view, the device outflow graft can often also be visualized. Using pulsed-wave Doppler, the characteristic flow signal can be obtained. The subcostal window may additionally be used to gain further information on the position of the interatrial and interventricular septa, as well as to assess right ventricular function and tricuspid valve performance. The recommended echocardiographic subcostal views and recordings include the following.

Longitudinal view of the vena cava inferior

Subcostal four chamber view

Color doppler oft he hepatic veins

PW-doppler oft he hepatic veins

5. Interpretation of the Echocardiographic Findings

Beyond acquisition of the above-mentioned views and measurement of the corresponding parameters, echocardiography in LVAD patients requires a fundamental understanding of the individual parameters in the context of hemodynamics, cardiac function, and device performance.

5.1. Left Ventricular Size and Function

As noted above, left ventricular size should primarily be assessed using linear measurements. Implantation of a continuous-flow LVAD is typically associated with progressive left ventricular unloading and a corresponding reduction in ventricular size While mean left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) reduction of approximately 1 cm has been reported, the magnitude of this change varies substantially between individual patients [

7,

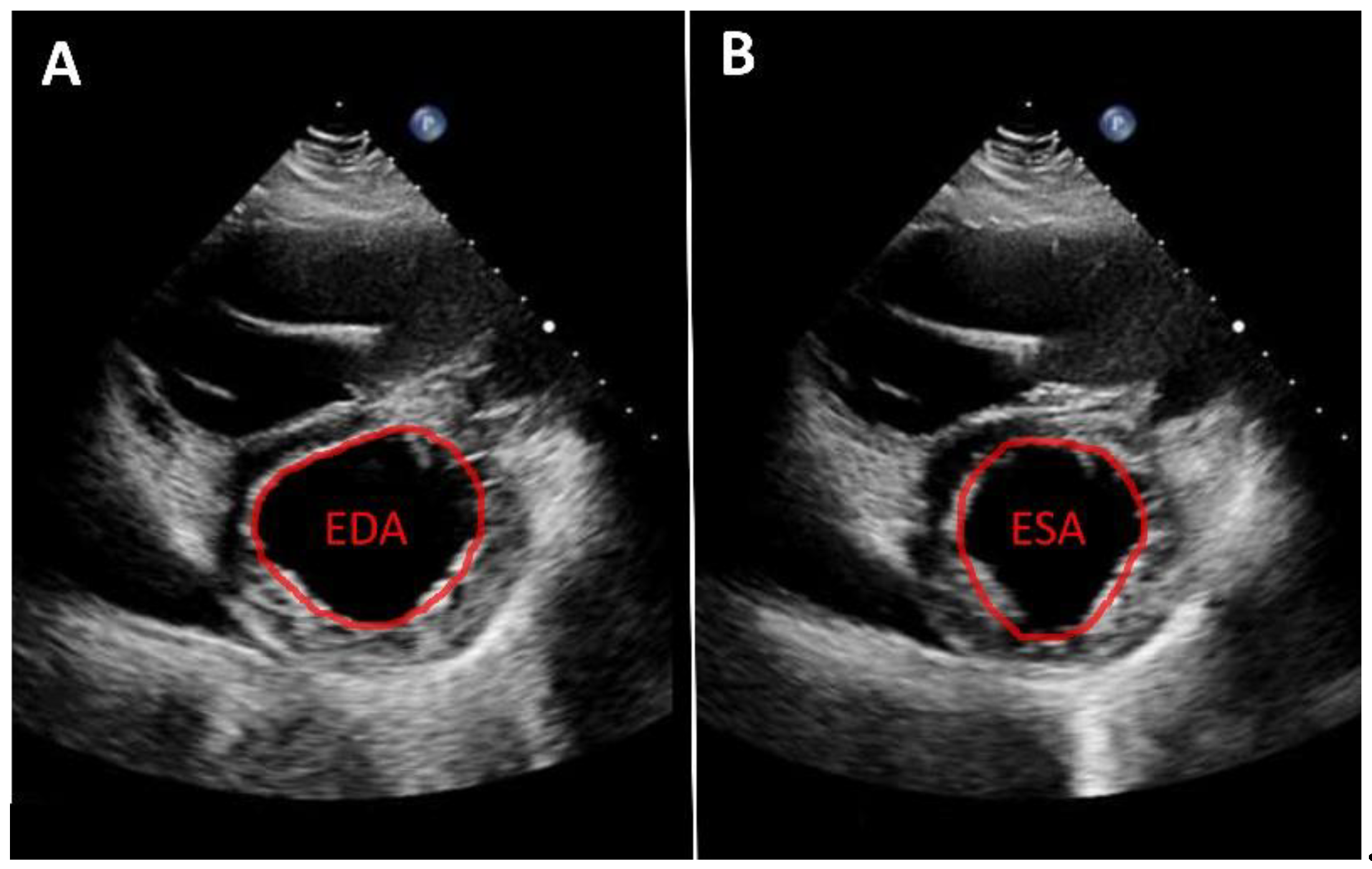

10]. A substantial reduction in left ventricular diameter is often associated with a leftward septal shift and may occur in the context of excessive left ventricular unloading. Left ventricular function can likewise only rarely be quantified from apical views. Consequently, volumetric determination of ejection fraction as well as assessment of global longitudinal strain are usually not feasible. Therefore, linear measurements—such as fractional shortening—obtained from the parasternal long-axis view are recommended. An even more accurate assessment, which is also frequently feasible, is measurement of left ventricular fractional area change in the parasternal short-axis view (

Figure 1). Mild improvements in left ventricular function after LVAD implantation are frequently observed [

7,

10,

11]. More substantial recovery of left ventricular function has been reported in a small but clinically relevant subset of patients [

8,

12,

13]. In such cases, following comprehensive evaluation using dedicated testing and standardized weaning protocols, LVAD explantation may be considered.

5.2. Mitral Valve

Preoperative mitral regurgitation (MR) often decreases markedly after LVAD implantation [

7,

14]. Concomitant mitral valve repair at the time of LVAD implantation may be considered in selected cases but is not strongly recommended by current guidelines [

15,

16]. However, significant residual MR after LVAD implantation has been associated with persistent pulmonary hypertension and impaired right ventricular function [

17,

18].

Echocardiographic assessment of MR in LVAD patients should primarily rely on parasternal views, as apical imaging is frequently limited. In selected cases, apical visualization and quantification using the PISA method may be feasible. Importantly, the severity of MR is flow-dependent and influenced by LVAD settings. Only rare cases of percutaneous mitral valve repair (MitraClip™) after LVAD implantation have been reported [

19].

5.3. Aortic Valve

In patients with an LVAD, aortic valve opening depends on left ventricular contractility, left ventricular filling, and the pump speed and resulting flow through the LVAD. A persistently non-opening aortic valve is not uncommon and is observed in approximately one third of patients [

7]. A persistently non-opening aortic valve is associated with a poorer prognosis and promotes the development of aortic regurgitation [

20,

21,

22,

23]. For echocardiographic assessment of aortic valve opening, visualization in zoom mode as well as the use of M-mode are recommended. The degree of aortic valve opening should be documented in every examination. It has proven useful to distinguish between absent opening, intermittent opening, and regular opening of the aortic valve during the cardiac cycle.

Aortic regurgitation (AR) is a common finding in patients supported by durable LVADs. With contemporary continuous-flow devices, AR develops in approximately 8% of patients within the first year after implantation [

24,

25]. Its incidence increases progressively over time, with up to 25% of patients developing moderate or severe AR after 48 months, as reported in the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS) registry [

26].

The development of AR results in a recirculating loop between the aorta and the left ventricle, leading to ineffective forward flow and reduced systemic perfusion. Clinically relevant AR is associated with higher rates of heart-failure–related hospitalizations and reduced survival [

26].

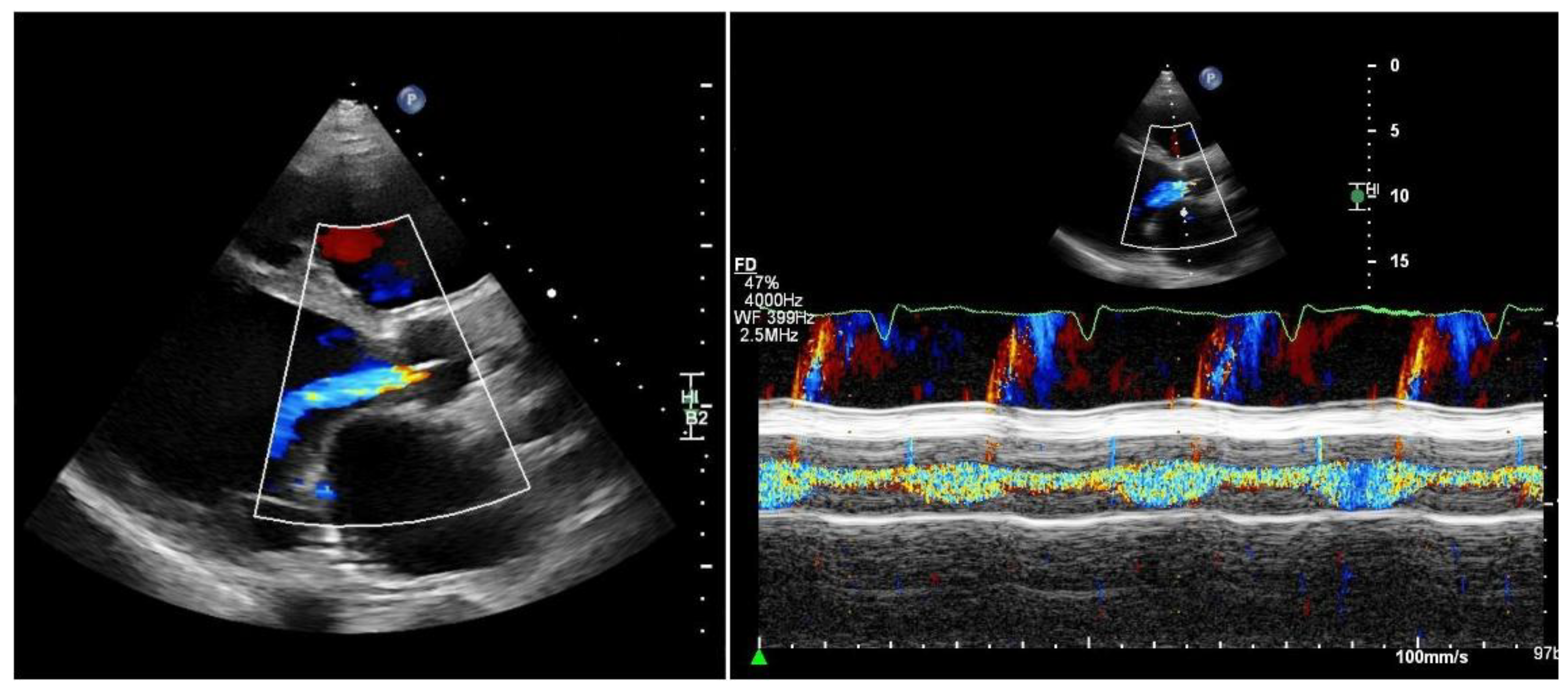

Quantifying aortic regurgitation (AR) in patients supported by a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) remains challenging. Conventional echocardiographic parameters are based on the assumption of isolated diastolic regurgitation, an assumption that often does not apply in the LVAD setting. In fact, holocyclic regurgitation (systolic and diastolic) is frequently observed, particularly in patients with more advanced AR (

Figure 2).

Consequently, accurate quantification of AR should ideally be performed at specialized centers. Comprehensive assessment typically requires transthoracic echocardiography supplemented by transesophageal echocardiography to improve visualization of the regurgitant jet, as well as right heart catheterization for detailed hemodynamic evaluation [

24,

25].

As a practical and readily available approach, vena contracta width and the ratio of the regurgitant jet width to the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) diameter may be used for semi-quantitative assessment:

Both parameters suggest at least moderate, AR [

27]. Conversely, if the regurgitant jet is absent or only mildly detectable during diastole, mild AR may be assumed. In addition, progressive left ventricular dilatation over time supports the presence of chronic volume overload and is consistent with hemodynamically significant AR, particularly in symptomatic patients.

More recently, a novel transthoracic pulse-wave Doppler – based parameter obtained from a modified right-sided parasternal window has been proposed. By interrogating the LVAD outflow graft, diastolic flow acceleration and the systolic-to-diastolic peak velocity ratio (S/D ratio) can be calculated [

28]:

5.4. Right Ventricle

Even after LVAD implantation, the patient’s right heart must continue to function. Right ventricular contraction pumps blood through the pulmonary circulation, thereby ensuring adequate filling of the left ventricle and, consequently, sufficient inflow to the LVAD. Clinical experience shows that even ventricular fibrillation can be compensated for a limited period of time, as the LVAD is able to draw blood through the pulmonary circulation. However, the development of clinical decompensation—with peripheral edema, ascites, reduced exercise capacity, and ultimately declining LVAD flow—is an inevitable consequence over time.

Acute right ventricular failure after LVAD implantation occurs in approximately 10–40% of cases [

29] and, in severe cases, may necessitate a right ventricular assist device. However, this entity is not the focus of the present review.

Chronic right ventricular failure is also a common phenomenon and manifests as clinical signs of right-sided heart failure, often requiring hospitalization and treatment with intravenous diuretics and/or inotropic therapy [

30].

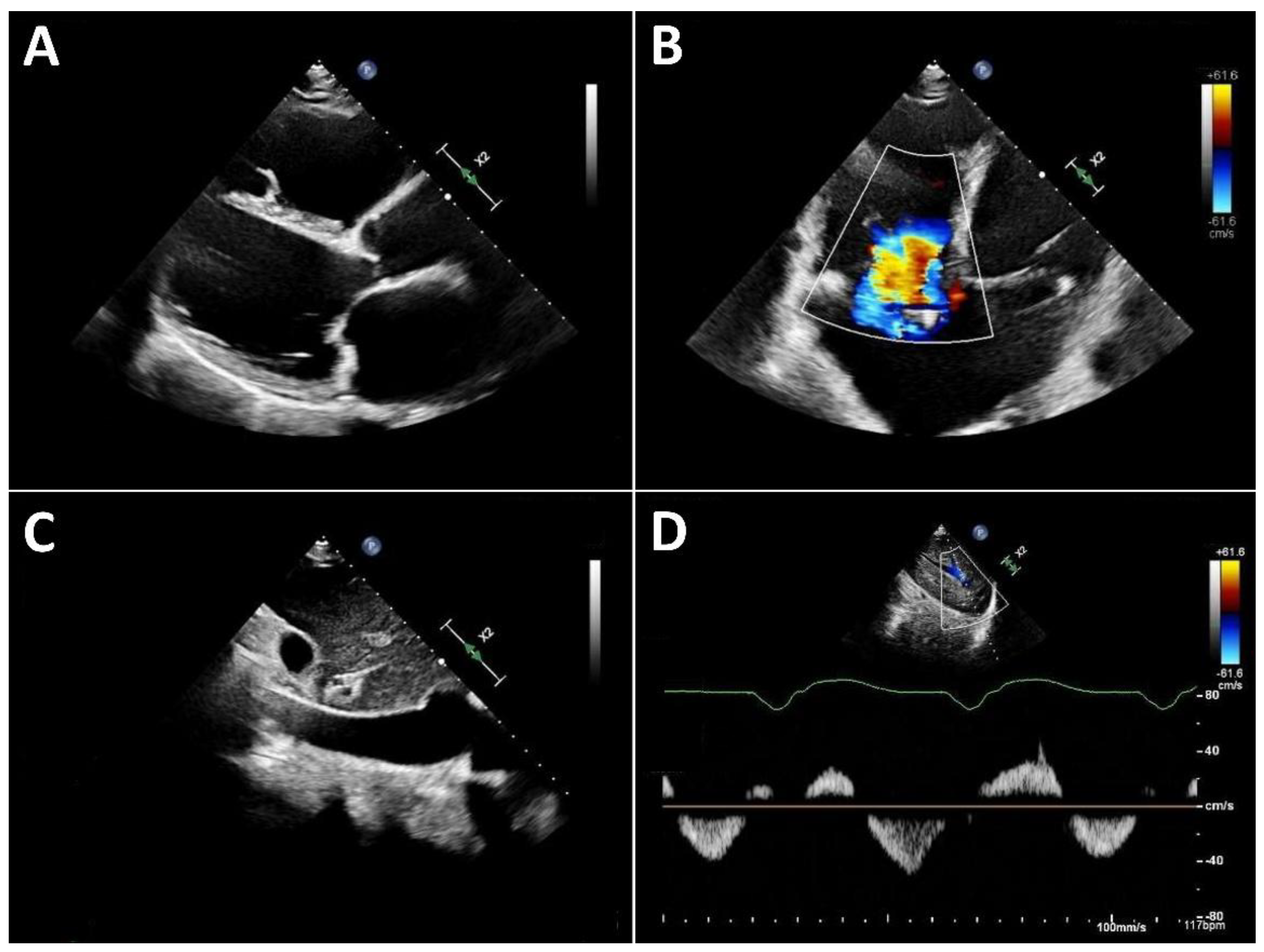

Typical echocardiographic signs of right ventricular failure include right ventricular dilatation, reflected by an increase in the proximal RV outflow tract (RVOT) diameter and RVD1 (

Figure 3). This is frequently accompanied by dilatation of the tricuspid annulus with progressive tricuspid regurgitation. In severe cases, a leftward deviation of the interventricular septum may be observed. In advanced stages, the inferior vena cava is markedly dilated and exhibits significantly reduced respiratory variation. Quantification of tricuspid regurgitation can be performed using the standard guideline-recommended parameters, with a five-grade severity classification having proven useful [

31].

Three-dimensional echocardiography of the right heart is often not feasible in many LVAD patients due to limited acoustic windows. Therefore, assessment of right ventricular (RV) function primarily relies on two-dimensional parameters. Longitudinal RV function is frequently reduced after cardiac surgery [

32], a finding that is also observed in patients with LVAD support. Accordingly, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) typically decreases after LVAD implantation [

7,

33]. This reduction in longitudinal function is, however, partially compensated by an increase in radial RV contraction.

Consequently, right ventricular fractional area change (FAC) is recommended over TAPSE for the assessment of RV function in LVAD patients [

34]. Importantly, RV function under LVAD support cannot be adequately characterized by a single parameter. Instead, it should always be interpreted in the context of preload (inferior vena cava filling), afterload (pulmonary artery pressure), septal position (reflecting adequate left ventricular filling), and the severity of tricuspid regurgitation.

6. Interaction and Interdependence of Valve Function, Ventricular Function and Measured Parameters

There are substantial interactions between valvular dysfunction, ventricular function, and LVAD support. Isolated right ventricular failure, for example, rarely occurs in isolation; it inevitably leads to reduced left ventricular filling. As a consequence, the left ventricle may be unable to generate native systolic ejection, resulting in a persistently closed aortic valve and, ultimately, the development of secondary aortic regurgitation.

Another example is severe mitral regurgitation, which likewise leads to impaired effective left ventricular forward stroke volume and aortic valve opening promoting the long-term development of aortic regurgitation. In addition, by increasing pulmonary arterial pressure, severe mitral regurgitation may further contribute to right ventricular loading and dysfunction.

Adjustment of LVAD flow can have a substantial impact on echocardiographic parameters. For example, increasing LVAD flow by raising pump speed (RPM) alters intracardiac filling pressures [

3]. This, in turn, affects cardiac geometry and the interaction between the right and left ventricles [

35]. Therefore, achieving optimal device settings often requires the use of a ramp test, particularly in the presence of valvular regurgitation and/or right ventricular dysfunction. In such a ramp test, hemodynamics are assessed in parallel using right heart catheterization and echocardiography, while LVAD settings are adjusted according to a predefined protocol [

36,

37].

Details of ramp testing, as well as specific protocols for evaluating myocardial recovery prior to LVAD explantation, are beyond the scope of this review. Readers are referred to the relevant literature.

7. A normal Echocardiographic Finding

With adequate interaction between the LVAD and the patient’s heart, the left ventricle may be markedly dilated. More important than ventricular size alone is the position of the interventricular septum, which should be midline and should not exhibit abnormal systolic leftward displacement throughout the cardiac cycle. Left ventricular systolic function may be severely reduced without representing a pathological finding in this context. In contrast, normal or near-normal ejection fraction (or fractional area change and fractional shortening) should prompt consideration of the potential for LVAD weaning, which should subsequently be evaluated in dedicated follow-up testing.

The aortic valve may remain closed throughout the entire cardiac cycle. However, particularly in patients without an intention for LVAD weaning or explantation, intermittent or regular opening of the aortic valve is generally preferable.

Ideally, no aortic regurgitation should be present. If aortic regurgitation is detected, it should be ensured that it is only mild. It should be noted that, due to their frequently continuous systolic and diastolic regurgitant flow, aortic regurgitation in LVAD patients is often underestimated when assessed using conventional echocardiographic parameters. Mild to moderate mitral regurgitation may occur and can usually be tolerated. In cases of severe mitral regurgitation, further evaluation should be considered, including a ramp test with right heart catheterization.

Evaluation of the right heart includes the conventional parameters recommended by current guidelines [

38] (Mukherjee). However, TAPSE is frequently markedly reduced in LVAD patients and is therefore of limited value for routine assessment of right ventricular function. More useful global indicators of significantly impaired right ventricular function include right ventricular size, the severity of tricuspid regurgitation, and the diameter and respiratory variability of the inferior vena cava.

In the setting of an overall normal examination, only mild right ventricular dilatation and mild to moderate tricuspid regurgitation should be present. The inferior vena cava may be dilated as a consequence of long-standing cardiac disease, but preserved respiratory variability should still be demonstrable.

8. Summary

Echocardiography is an indispensable tool in the routine care of patients with durable LVAD support. A standardized imaging protocol combined with a basic understanding of LVAD physiology and device–heart interactions allows reliable assessment of cardiac function and hemodynamic status in everyday clinical practice. The structured approach outlined in this review is intended to support sonographers and cardiologists in performing and interpreting routine echocardiographic examinations in LVAD patients, both in the outpatient setting and during non–device-related hospital admissions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Standardized Echocardiographic Imaging Protocol for Patients with LVADs.

Author Contributions

N.M. Conceptualization, writing – original draft preparation, visualization; F.S. writing—review and editing; E.P. writing—review and editing; J.K. Conceptualization, writing – original draft preparation, visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 5.2 for translation. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

N. M. reports honoraria for lectures from GE Healthcare. E.P. has received consulting fees as well as honoraria for lectures from Abbott, Abiomed, and Recovery Therapeutics, and has served on an advisory board for Abbott. F.S received institutional grants from Novartis, Abbott, and institutional fees (speaker honoraria) from Abbott, Bayer, Novartis and Johnson&Johnson outside of the submitted work. J.K. decares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LVAD |

left ventricular assist device |

| VAD |

ventricular assist device |

| RPM |

rounds per minute |

| LV |

left ventricle |

| RV |

right ventricle |

| PI |

pulsatility index |

| MCS |

mechanical circulatory support |

| 2D |

two-dimensional |

| LVEDD |

left ventricular end-diastolic diameter |

| MR |

mitral regurgitation |

| AR |

aortic regurgitation |

| INTERMACS |

interagency registry for mechanical assisted circulatory support |

| LVOT |

left ventricular outflowtract |

| RVOT |

right ventricular outflowtract |

| TAPSE |

tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion |

| FAC |

fractional area change |

References

- Nayak, A.; Cascino, T.M.; DeFilippis, E.M.; Hanff, T.C.; Cevasco, M.; Keenan, J.; Zhen-Yu Tong, M.; Kilic, A.; Koehl, D.; Cantor, R.; et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs 2025 Annual Report: Focus on Outcomes in Older Adults. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2025, S0003497525010604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, M.R.; Goldstein, D.J.; Cleveland, J.C.; Cowger, J.A.; Hall, S.; Salerno, C.T.; Naka, Y.; Horstmanshof, D.; Chuang, J.; Wang, A.; et al. Five-Year Outcomes in Patients With Fully Magnetically Levitated vs Axial-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices in the MOMENTUM 3 Randomized Trial. JAMA 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, A.N.; Frantz, R.P.; Kushwaha, S.S.; Stulak, J.M.; Maltais, S.; Behfar, A. Novel Left Heart Catheterization Ramp Protocol to Guide Hemodynamic Optimization in Patients Supported With Left Ventricular Assist Device Therapy. JAHA 2019, 8, e010232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandroglio, A.M.; Kaufmann, F.; Pieri, M.; Kretzschmar, A.; Müller, M.; Pergantis, P.; Dreysse, S.; Falk, V.; Krabatsch, T.; Potapov, E.V. Diagnosis and Treatment Algorithm for Blood Flow Obstructions in Patients With Left Ventricular Assist Device. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 67, 2758–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015, 16, 233–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estep, J.D.; Nicoara, A.; Cavalcante, J.; Chang, S.M.; Cole, S.P.; Cowger, J.; Daneshmand, M.A.; Hoit, B.D.; Kapur, N.K.; Kruse, E.; et al. Recommendations for Multimodality Imaging of Patients With Left Ventricular Assist Devices and Temporary Mechanical Support: Updated Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2024, 37, 820–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulzer, J.; Krastev, H.; Hoermandinger, C.; Merke, N.; Alhaloush, M.; Schoenrath, F.; Falk, V.; Potapov, E.; Knierim, J. Cardiac Remodeling in Patients with Centrifugal Left Ventricular Assist Devices Assessed by Serial Echocardiography. Echocardiography 2022, echo.15338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knierim, J.; Heck, R.; Pieri, M.; Schoenrath, F.; Soltani, S.; Stawowy, P.; Dreysse, S.; Stein, J.; Müller, M.; Mulzer, J.; et al. Outcomes from a Recovery Protocol for Patients with Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2019, 38, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrytsyna, Y.; Kneissler, S.; Kaufmann, F.; Müller, M.; Schoenrath, F.; Mulzer, J.; Sündermann, S.H.; Falk, V.; Potapov, E.; Knierim, J. Experience with a Standardized Protocol to Predict Successful Explantation of Left Ventricular Assist Devices. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2021, S0022522321000374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topilsky, Y.; Oh, J.K.; Atchison, F.W.; Shah, D.K.; Bichara, V.M.; Schirger, J.A.; Kushwaha, S.S.; Pereira, N.L.; Park, S.J. Echocardiographic Findings in Stable Outpatients with Properly Functioning HeartMate II Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography 2011, 24, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakos, S.G.; Wever-Pinzon, O.; Selzman, C.H.; Gilbert, E.M.; Alharethi, R.; Reid, B.B.; Saidi, A.; Diakos, N.A.; Stoker, S.; Davis, E.S.; et al. Magnitude and Time Course of Changes Induced by Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device Unloading in Chronic Heart Failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2013, 61, 1985–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwar, M.K.; Selzman, C.H.; Ton, V.-K.; Miera, O.; CornwellIII, W.K.; Antaki, J.; Drakos, S.; Shah, P. Clinical Myocardial Recovery in Advanced Heart Failure with Long Term Left Ventricular Assist Device Support. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2022, S105324982201957X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birks, E.J.; Drakos, S.G.; Patel, S.R.; Lowes, B.D.; Selzman, C.H.; Starling, R.C.; Trivedi, J.; Slaughter, M.S.; Atluri, P.; Goldstein, D.; et al. A Prospective Multicentre Study of Myocardial Recovery Using Left Ventricular Assist Devices (REmission from Stage D Heart Failure: RESTAGE-HF): Medium Term and Primary Endpoint Results. Circulation 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrovie, M.; Spampinato, R.A.; Efimova, E.; da Rocha e Silva, J.G.; Fischer, J.; Kuehl, M.; Voigt, J.-U.; Belmans, A.; Ciarka, A.; Bonamigo Thome, F.; et al. Reversibility of Severe Mitral Valve Regurgitation after Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: Single-Centre Observations from a Real-Life Population of Patients†. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 2018, 53, 1144–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, E.V.; Antonides, C.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Combes, A.; Färber, G.; Hannan, M.M.; Kukucka, M.; de Jonge, N.; Loforte, A.; Lund, L.H.; et al. 2019 EACTS Expert Consensus on Long-Term Mechanical Circulatory Support. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 2019, ezz098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, D.; Feldman, D.; Banayosy, A.E.; Birks, E.; Blume, E.; Cowger, J.; Hayward, C.; Jorde, U.; Kremer, J.; MacGowan, G.; et al. The 2023 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for Mechanical Circulatory Support: A 10- Year Update. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2023, 42, e1–e222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassis, H.; Cherukuri, K.; Agarwal, R.; Kanwar, M.; Elapavaluru, S.; Sokos, G.G.; Moraca, R.J.; Bailey, S.H.; Murali, S.; Benza, R.L.; et al. Significance of Residual Mitral Regurgitation After Continuous Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation. JACC: Heart Failure 2017, 5, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertugay, S.; Kemal, H.S.; Kahraman, U.; Engin, C.; Nalbantgil, S.; Yagdi, T.; Ozbaran, M. Impact of Residual Mitral Regurgitation on Right Ventricular Systolic Function After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation: MITRAL REGURGITATION AFTER LVAD IMPLANTATION. Artificial Organs 2017, 41, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.K.; Vullaganti, S.; Maybaum, S.; Lima, B.; Fernandez, H.; Stevens, G.; Davidson, K.; Rutkin, B.; Wilson, S.; Koss, E.; et al. “Clipping the Leak” - A Case Series of Transcatheter Mitral Valve Repair after Left Ventricular Assist Device. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2021, 40, S520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobarro, D.; Urban, M.; Booth, K.; Wrightson, N.; Castrodeza, J.; Jungschleger, J.; Robinson-Smith, N.; Woods, A.; Parry, G.; Schueler, S.; et al. Impact of Aortic Valve Closure on Adverse Events and Outcomes with the HeartWare Ventricular Assist Device. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2017, 36, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Dorta, E.; Meyn, R.; Müller, M.; Hoermandinger, C.; Schoenrath, F.; Falk, V.; Meyer, A.; Merke, N.; Potapov, E.; Mulzer, J.; et al. Potential Benefits of Aortic Valve Opening in Patients with Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Artificial Organs 2024, aor.14891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatano, M.; Kinugawa, K.; Shiga, T.; Kato, N.; Endo, M.; Hisagi, M.; Nishimura, T.; Yao, A.; Hirata, Y.; Kyo, S.; et al. Less Frequent Opening of the Aortic Valve and a Continuous Flow Pump Are Risk Factors for Postoperative Onset of Aortic Insufficiency in Patients With a Left Ventricular Assist Device. Circ J 2011, 75, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deo, S.V.; Sharma, V.; Cho, Y.H.; Shah, I.K.; Park, S.J. De Novo Aortic Insufficiency During Long-Term Support on a Left Ventricular Assist Device: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. ASAIO Journal 2014, 60, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, D.; Grinstein, J.; Kremer, J.; Cowger, J.A. Aortic Insufficiency in the Patient on Contemporary Durable Left Ventricular Assist Device Support: A State-of-the-Art Review on Preoperative and Postoperative Assessment and Management. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2024, 43, 1881–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowger, J.; Pagani, F.D.; Haft, J.W.; Romano, M.A.; Aaronson, K.D.; Kolias, T.J. The Development of Aortic Insufficiency in Left Ventricular Assist Device-Supported Patients. Circ Heart Fail 2010, 3, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truby, L.K.; Garan, A.R.; Givens, R.C.; Wayda, B.; Takeda, K.; Yuzefpolskaya, M.; Colombo, P.C.; Naka, Y.; Takayama, H.; Topkara, V.K. Aortic Insufficiency During Contemporary Left Ventricular Assist Device Support. JACC: Heart Failure 2018, 6, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainback, R.F.; Estep, J.D.; Agler, D.A.; Birks, E.J.; Bremer, M.; Hung, J.; Kirkpatrick, J.N.; Rogers, J.G.; Shah, N.R. Echocardiography in the Management of Patients with Left Ventricular Assist Devices: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography 2015, 28, 853–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstein, J.; Kruse, E.; Sayer, G.; Fedson, S.; Kim, G.H.; Jorde, U.P.; Juricek, C.; Ota, T.; Jeevanandam, V.; Lang, R.M.; et al. Accurate Quantification Methods for Aortic Insufficiency Severity in Patients With LVAD. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2016, 9, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, B.C.; Teuteberg, J.J. Right Ventricular Failure after Left Ventricular Assist Devices. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015, 34, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, R.L.; Antonides, C.F.J.; Goldstein, D.J.; Cowger, J.A.; Starling, R.C.; Kirklin, J.K.; Rame, J.E.; Rosenthal, D.; Mooney, M.L.; Caliskan, K.; et al. Updated Definitions of Adverse Events for Trials and Registries of Mechanical Circulatory Support: A Consensus Statement of the Mechanical Circulatory Support Academic Research Consortium. J Heart Lung Transplant 2020, 39, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.T.; Thomas, J.D.; Khalique, O.K.; Cavalcante, J.L.; Praz, F.; Zoghbi, W.A. Imaging Assessment of Tricuspid Regurgitation Severity. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019, 12, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raina, A.; Vaidya, A.; Gertz, Z.M.; Susan Chambers; Forfia, P.R. Marked Changes in Right Ventricular Contractile Pattern after Cardiothoracic Surgery: Implications for Post-Surgical Assessment of Right Ventricular Function. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2013, 32, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapor, M.; Pilat, A.; Gackowski, A.; Misiuda, A.; Gorkiewicz-Kot, I.; Kaleta, M.; Kleczynski, P.; Zmudka, K.; Legutko, J.; Kapelak, B.; et al. Echo-Guided Left Ventricular Assist Device Speed Optimisation for Exercise Maximisation. Heart 2022, 108, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulzer, J.; Krastev, H.; Hoermandinger, C.; Meyer, A.; Haese, T.; Stein, J.; Müller, M.; Schoenrath, F.; Knosalla, C.; Starck, C.; et al. Development of Tricuspid Regurgitation and Right Ventricular Performance after Implantation of Centrifugal Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2021, 10, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addetia, K.; Uriel, N.; Maffessanti, F.; Sayer, G.; Adatya, S.; Kim, G.H.; Sarswat, N.; Fedson, S.; Medvedofsky, D.; Kruse, E.; et al. 3D Morphological Changes in LV and RV During LVAD Ramp Studies. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2018, 11, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriel, N.; Morrison, K.A.; Garan, A.R.; Kato, T.S.; Yuzefpolskaya, M.; Latif, F.; Restaino, S.W.; Mancini, D.M.; Flannery, M.; Takayama, H.; et al. Development of a Novel Echocardiography Ramp Test for Speed Optimization and Diagnosis of Device Thrombosis in Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices: The Columbia Ramp Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012, 60, 1764–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, E.; Thorvaldsen, T.; Dalén, M.; Svenarud, P.; Hallberg Kristensen, A.; Eriksson, M.J.; Maret, E.; Lund, L.H. Validation of Non-Invasive Ramp Testing for HeartMate 3. ESC Heart Fail 2020, 7, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Rudski, L.G.; Addetia, K.; Afilalo, J.; D’Alto, M.; Freed, B.H.; Friend, L.B.; Gargani, L.; Grapsa, J.; Hassoun, P.M.; et al. Guidelines for the Echocardiographic Assessment of the Right Heart in Adults and Special Considerations in Pulmonary Hypertension: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2025, 38, 141–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).