Submitted:

25 December 2025

Posted:

26 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

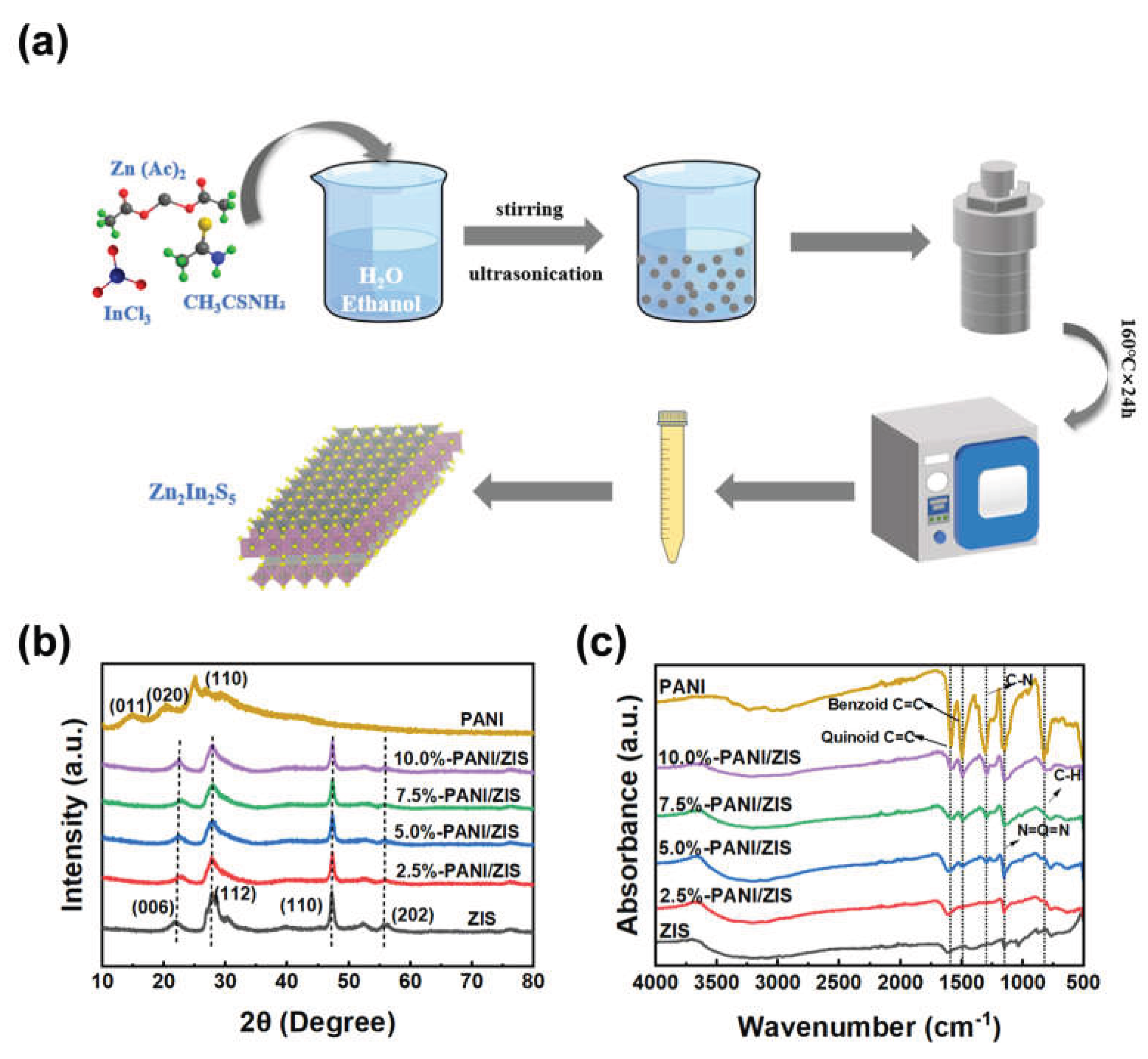

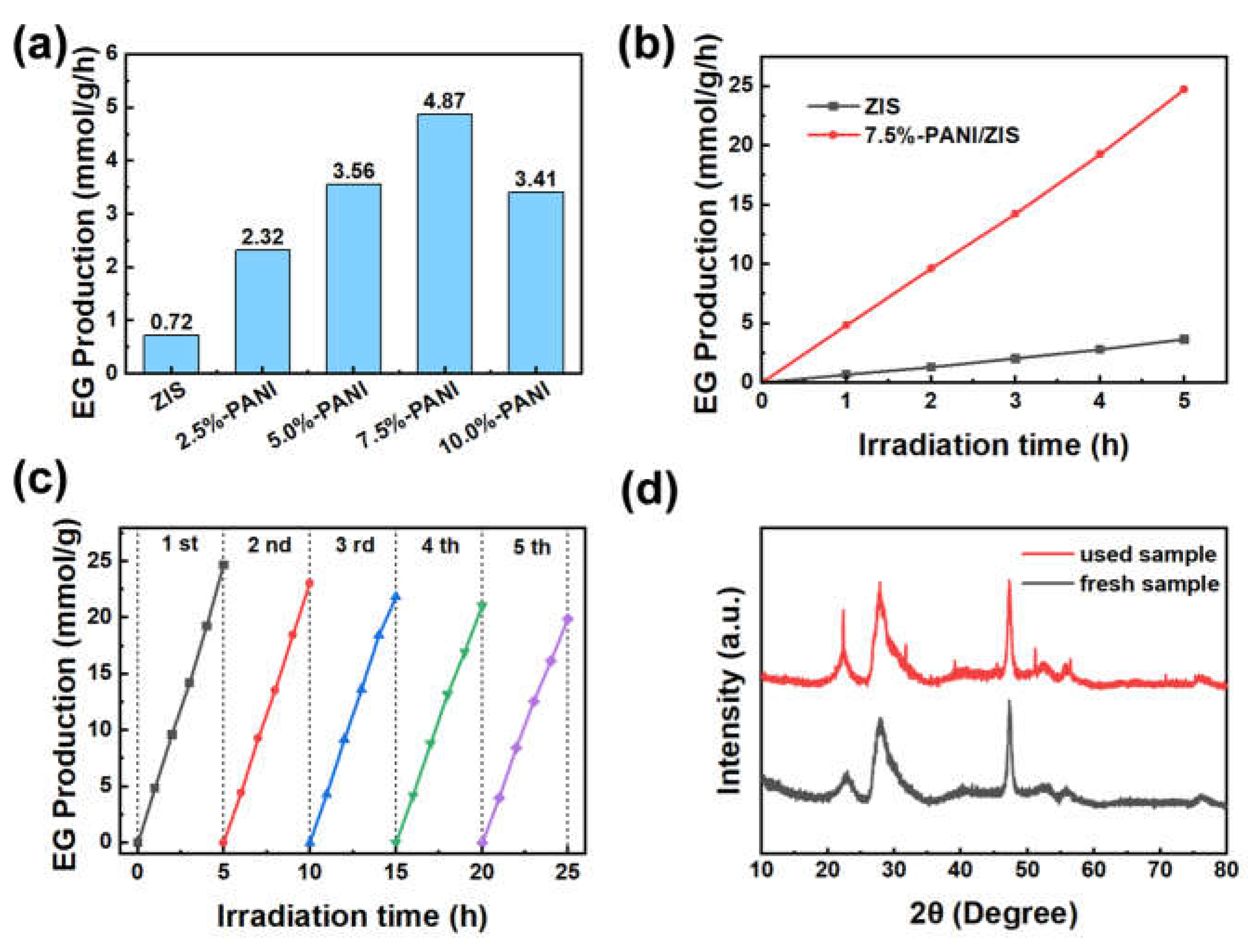

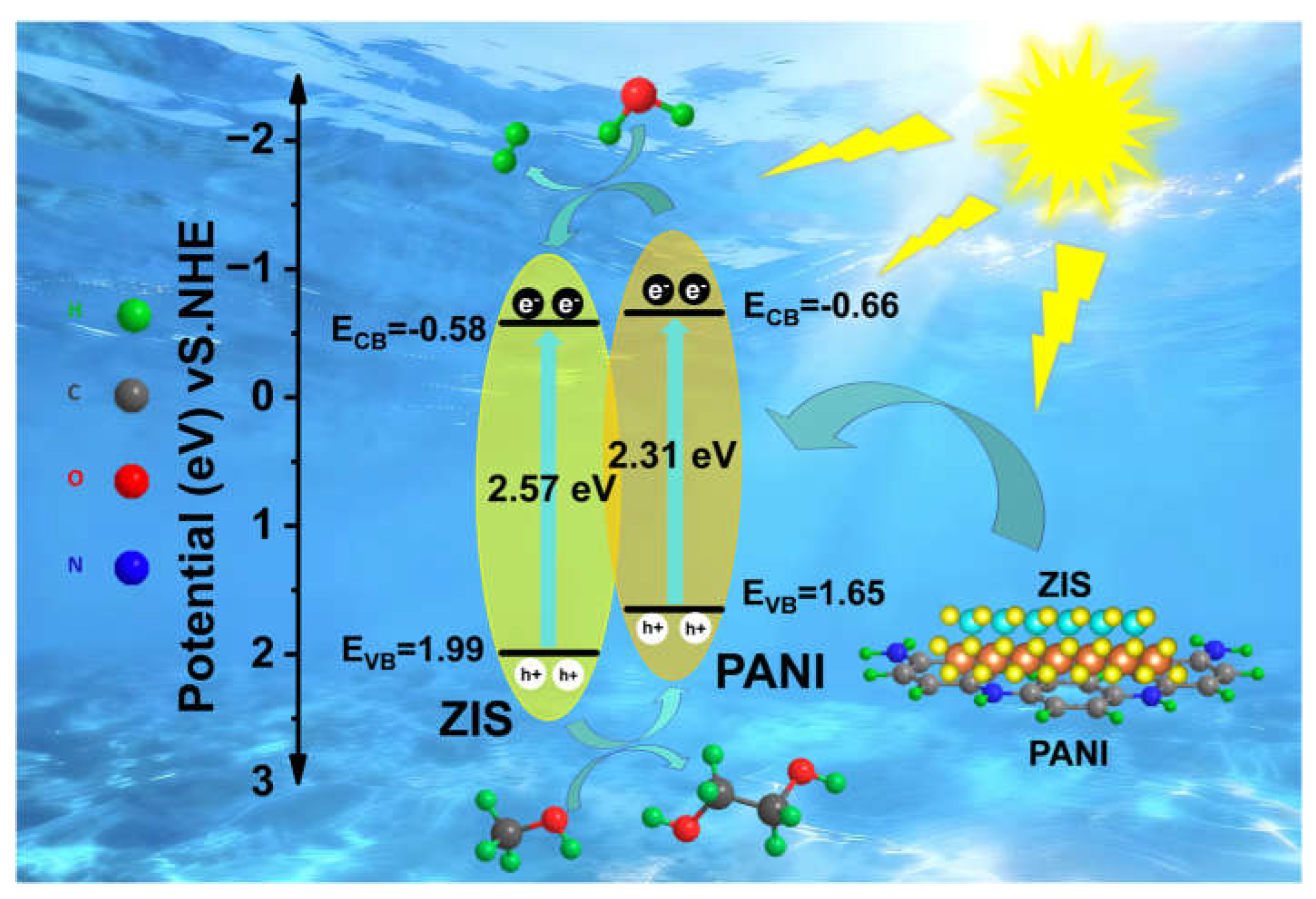

The photocatalytic dehydrogenative coupling of methanol to produce the high-value-added chemical ethylene glycol (EG) has garnered widespread attention owing to its environmental benignity and mild reaction conditions. The ternary metal sulfide Zn2In2S5(ZIS), by virtue of its unique stoichiometric ratio, demonstrates a high intrinsic selectivity for the activation of the α-C-H bond in methanol. However, pristine ZIS faces the challenge of rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, which severely restricts its photocatalytic efficiency. In this study, the conductive polymer polyaniline (PANI) was successfully coupled with the ZIS photocatalyst via a simple one-step hydrothermal polymerization method to fabricate a series of PANI/ZIS nanocomposite photocatalysts. Systematic evaluation results indicate that the optimal catalyst, 7.5%-PANI/ZIS, exhibits exceptional catalytic performance under visible light, achieving an ethylene glycol generation rate as high as 4.87 mmol/g/h, representing a 6.76-fold enhancement over pristine ZIS (0.72 mmol/g/h). The significant performance enhancement is attributed to the synergistic effects of PANI and ZIS, which formed Type-II heterojunction effectively promotes the separation and transport of photogenerated charges and significantly reduces the charge transfer resistance. This research provides new insights into interfacial engineering based on conductive polymers and is of significant scientific importance for the high-value utilization of C1 small molecules.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and instruments

2.2. Preparation of Photocatalysts

2.2.1. Preparation of Zn2In2S5

2.2.2. Preparation of PANI

2.2.3. Preparation of PANI/Zn2In2S5

2.3. Photocatalytic experiments

2.4. Electrochemical Measurements

3. Results

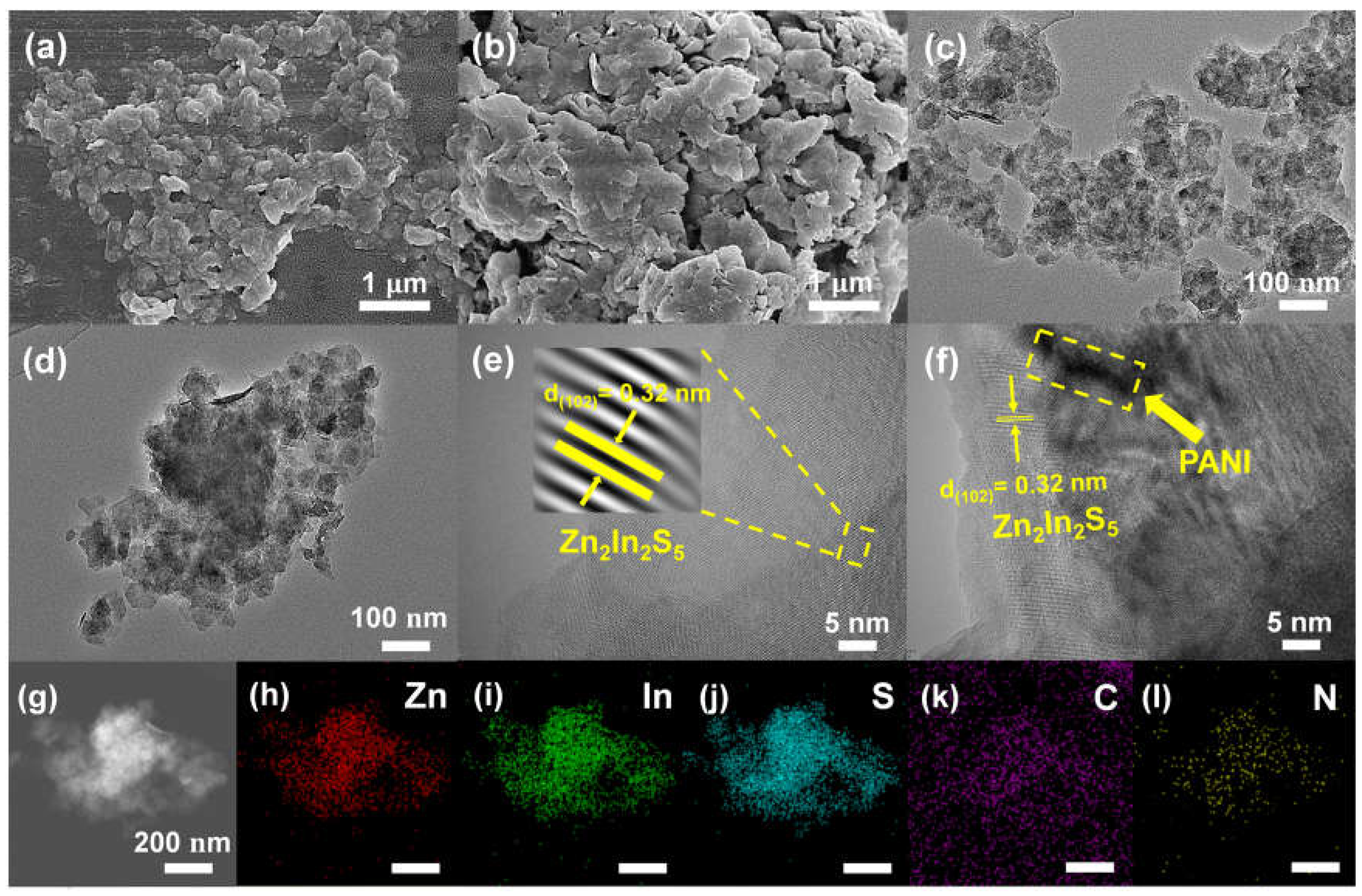

3.1. Structural characterization of catalysts

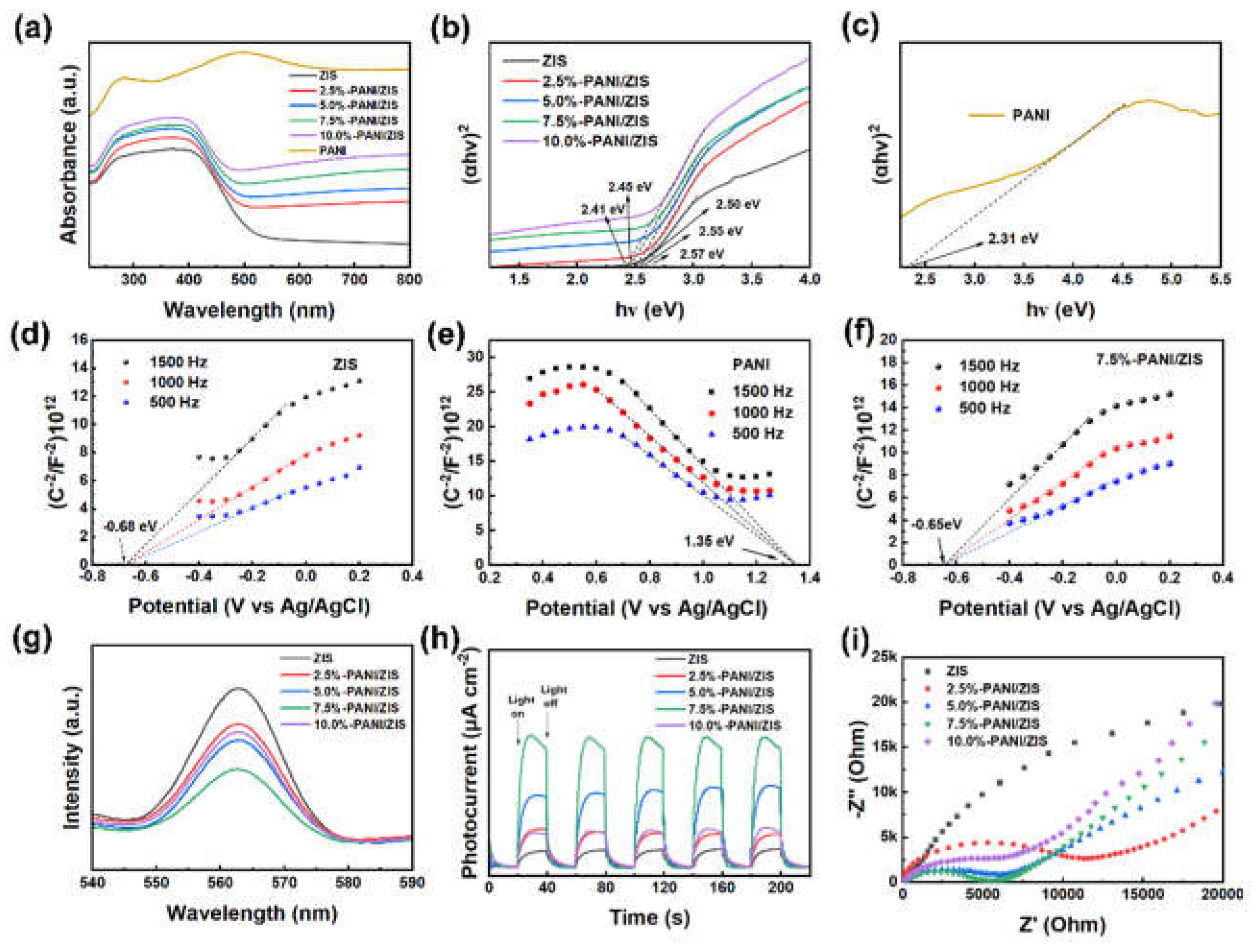

3.2. Photoelectric properties of composite photocatalysts

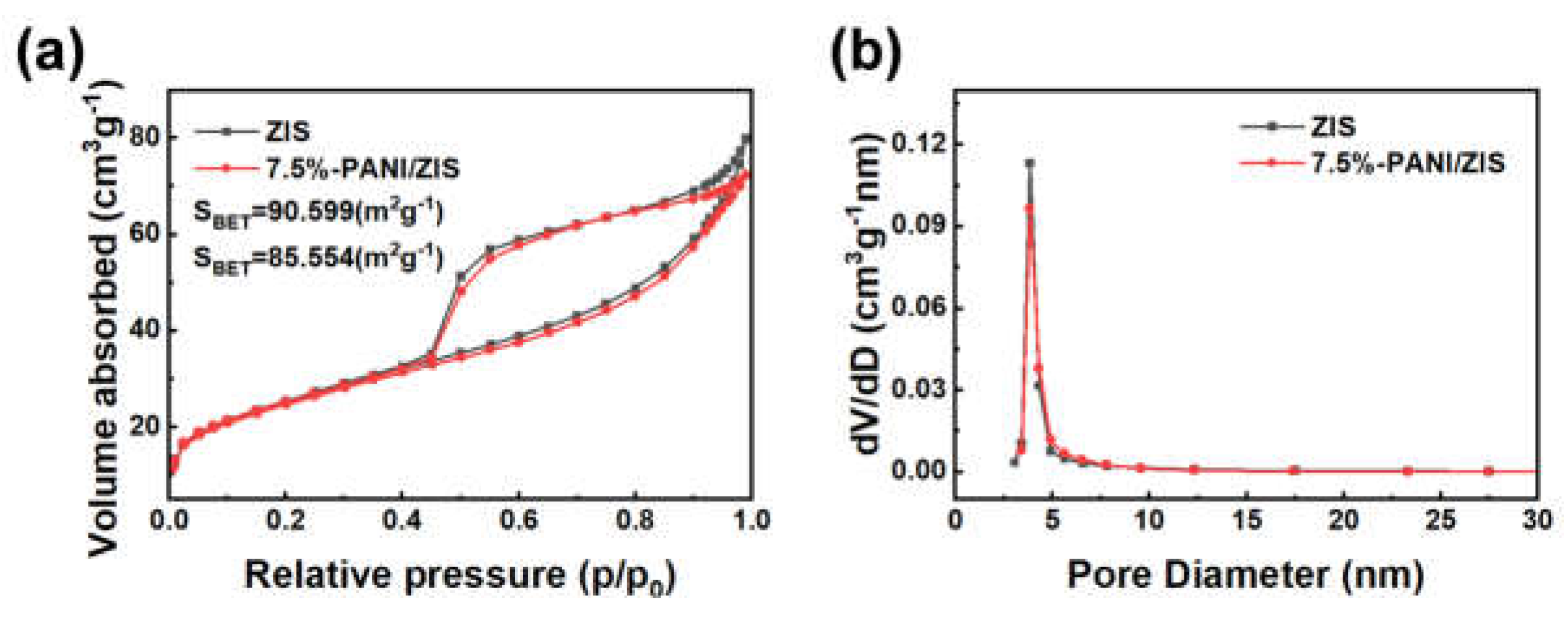

3.3. Nitrogen adsorption-desorption analysis

3.4. Photocatalytic activity of composite catalyst

3.5. Photocatalytic mechanism

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ZIS | Zn2In2S5 |

| PANI | Polyaniline |

| EG | Ethylene Glycol |

| CB | Conduction Band |

| VB | Valence Band |

| NHE | Normal Hydrogen Electrode |

| EIS | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| UV-vis DRS | Ultraviolet-visible Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

References

- Chandran, B.; Oh, J.-K.; Lee, S.-W.; Um, D.-Y.; Kim, S.-U.; Veeramuthu, V.; Park, J.-S.; Han, S.; Lee, C.-R.; Ra, Y.-H. Solar-Driven Sustainability: III–V Semiconductor for Green Energy Production Technologies. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Linley, S.; Reisner, E. Solar Reforming as an Emerging Technology for Circular Chemical Industries. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024, 8, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.; Foo, J. J.; Ong, W. Solar-powered Chemistry: Engineering Low-dimensional Carbon Nitride-based Nanostructures for Selective CO2 Conversion to C1-C2 Products. Infomat 2022, 4, e12279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Ma, Y.; Liu, T.; Liao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Su, C.; Liu, B. Uncovering the Photocatalytic Conversion of Methanol for C2+ Chemicals. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 111830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Ma, W.; Wu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Photocatalytic and Electrocatalytic Transformations of C1 Molecules Involving C-C Coupling. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 37–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Shen, Z.; Deng, J.; Guo, P.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ma, C.; Jiang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Deng, D.; Wang, Y. Visible Light-Driven C-H Activation and C-C Coupling of Methanol into Ethylene Glycol. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, F.; Hu, J.; Hu, W.; Xie, S.; Wang, Y.; Feng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Precisely Constructed Metal Sulfides with Localized Single-Atom Rhodium for Photocatalytic C−H Activation and Direct Methanol Coupling to Ethylene Glycol. Adv. Mater. 35, 2205782. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Xu, S.; Du, H.; Gong, Q.; Xie, S.; Deng, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Advances in the Solar-Energy Driven Conversion of Methanol to Value-Added Chemicals. Mol. Catal. 2022, 530, 112593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, Z.; Yang, D.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Tang, K.; Yang, H.; Zhan, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, W. Crystal-Interface-Mediated Self-Assembly of ZnIn2S4/CdS S-scheme Heterojunctions Toward Efficient Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Carbon Energy 2025, 7, e707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yin, Y.; Li, X.; Hu, G.; Wang, B. Sulfur Vacancy-Engineered O-Gradient ZnS@ZnIn2S4 Hollow Heterojunctions for Efficient Photocatalytic Co-Generation of Ethylene Glycol and Hydrogen from Methanol. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 518, 164602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebian-Kiakalaieh, A.; Li, H.; Guo, M.; Hashem, E. M.; Xia, B.; Ran, J.; Qiao, S.-Z. Photocatalytic Reforming Raw Plastic in Seawater by Atomically-Engineered GeS/ZnIn2S4. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2404963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Song, R.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Low, J.; Fu, F.; Xiong, Y. Full-Space Electric Field in Mo-Decorated Zn2In2S5 Polarization Photocatalyst for Oriented Charge Flow and Efficient Hydrogen Production. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2405060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Sun, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Z.; Yi, X.; Xie, S. Solar-Driven Highly Effective Biomass-Derived Alcohols C–C Coupling Integrated with H2 Production by CdS Quantum Dots Modified Zn2In2S5 Nanosheets. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 4581–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xie, S.; Hu, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Y. C-H Activations of Methanol and Ethanol and C-C Couplings into Diols by Zinc-Indium-Sulfide under Visible Light. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 1776–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Su, K.; Liu, X.; Cai, S.; He, P.; Xiao, Y.; Ren, T. Anchoring Bimetallic Phosphide NiCoP Cocatalyst on Marigold-like Zn2In2S5 for Enhanced Photocatalytic H2 Evolution Performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 119, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, L.; An, C. Engineered Metal-Atom Aggregates Enable Selective Ethylene Glycol Production through Photocatalytic Methanol C–C Coupling. Nano Res. 2025, 18, 94907765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.-X.; Zhang, M.-R.; Yuan, S.-X.; Zhang, M.; Lu, T.-B. Chlorine Radical-Mediated Photocatalytic C─C Coupling of Methanol to Ethylene Glycol with Near-Unity Selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202510993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Li, N.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Z. Photo-Fenton-Induced Selective Dehydrogenative Coupling of Methanol into Ethylene Glycol over Iron Species-Anchored TiO2 Nanorods. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2023, 13, 1482–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shi, L.; Su, J.; Li, J.; Xu, X. Selective Hydrobenzoin Photosynthesis from Benzyl Alcohol over AgIn5S8@Zn2In2S5 Seamless Heterostructures. Appl. Catal. B 2025, 378, 125613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shi, L.; Konysheva, E. Y.; Xu, X. Selective Photocatalysis of Benzyl Alcohol Valorization by Cocatalyst Engineering Over Zn2In2S5 Nanosheets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 35, 2418074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnan, N. S. N.; Nordin, N. A.; Mohamed, M. A. Synergistic Interaction and Hybrid Association of Conducting Polymer Photocatalysts/Photoelectrodes for Emerging Visible Light Active Photocatalytic Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 27892–27931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Wang, R.; Pan, Y.; Ni, J.; Liang, X.; Du, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, W. High Conductive Polymer PANI Link Bi2MoO6 and PBA to Establish “Tandem Hybrid Catalysis System” by Coupling Photocatalysis and PMS Activation Technology. Appl. Catal. B 2024, 344, 123621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Yin, J.; Xun, S.; Zhu, L.; Li, H.; He, M.; Wu, P.; Li, H.; Zhu, W. Constructing Interface Chemical Coupling S-Scheme Heterojunction MoO3-x@PPy for Enhancing Photocatalytic Oxidative Desulfurization Performance: Adjusting LSPR Effect via Oxygen Vacancy Engineering. Appl. Catal. B 2024, 355, 124155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Xiong, J.; Zeng, H.; Liao, M. Polyaniline-ZnTi-LDH Heterostructure with d–π Coupling for Enhanced Photocatalysis of Pollutant Removal. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 684, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadoun, S.; Yáñez, J.; Mansilla, H. D.; Riaz, U.; Chauhan, N. P. S. Conducting Polymers/Zinc Oxide-Based Photocatalysts for Environmental Remediation: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2063–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-Y.; Li, H.-S.; Kuchayita, K. K.; Huang, H.-C.; Su, W.-N.; Cheng, C.-C. Exfoliated 2D Nanosheet-Based Conjugated Polymer Composites with P-N Heterojunction Interfaces for Highly Efficient Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2407061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Ming, H.; Li, D.; Chen, T.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Xin, H.; Qin, X. Enhanced Phonon Scattering and Thermoelectric Performance for N-Type Bi2Te2.7Se0.3 through Incorporation of Conductive Polyaniline Particles. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455, 140923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, T.; Husain, S.; Khanuja, M. Novel Ternary Z Scheme Carbon Quantum Dots (CQDs) Decorated WS2/PANI ((CQDs@WS2/PANI):0D:2D:1D) Nanocomposite for the Photocatalytic Degradation and Electrochemical Detection of Pharmaceutical Drugs. Nano Mater. Sci. 2025, 7, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Y.; Huang, E.; Cao, L.; Gao, H.; Zhao, S.; Li, Y.; Li, W. Facile Synthesis of PA Photocatalytic Membrane Based on C-PANI@BiOBr Heterostructures with Enhanced Photocatalytic Removal of 17β-Estradiol. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 490, 151617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lyu, M.; Chen, P.; Tian, Y.; Kang, J.; Lai, Y.; Cheng, X.; Dong, Z. Photothermal Effect and Hole Transport Properties of Polyaniline for Enhanced Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting of BiVO4 Photoanode. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 684, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.; Gouadria, S.; Alharbi, F.; Iqbal, M. W.; Sunny, M. A.; Hassan, H.; Ismayilova, N. A.; Alrobei, H.; Alawaideh, Y. M.; Umar, E. Design and Optimization of ZnIn2S4/Zr2C@PANI Hybrid Materials for Improved Energy Storage and Hydrogen Evolution Performance toward Advanced Energy Applications. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 180, 114987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R.; Joshi, M. C.; Ramadurai, R.; Sunkara, M.; Kannan, V. Structural and Electrical Conductivity Studies of Polyaniline - WO3 Hybrid Nanocomposites for Gas Sensing Applications. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2778, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saib, F.; Abdi, A.; Haouchine, L. A.; Touahra, F.; Laoui, F. M.; Zemmache, S.; Lerari, D.; Bachari, K.; Trari, M. Synthesis, Physical Properties, and Photo-Electrochemical Characterization of a Novel n-Type PANI/PATSA Semiconductor. Polym. Bull. 2025, 82, 10947–10965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, H. N.; Le, T. V. Effect of Photoinduction in PANi/TiO2 Heterogeneous Structure on Conductance of PANi Component. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafuri, H.; keshvari, M.; Eshrati, F.; Hanifehnejad, P.; Emami, A.; Zand, H. R. E. Catalytic Efficiency of GO-PANI Nanocomposite in the Synthesis of N-Aryl-1,4-Dihydropyridine and Hydroquinoline Derivatives. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 82907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Hu, J.; Liu, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, C.; Zou, Z. Self-Integrated Black NiO Clusters with ZnIn2S4 Microspheres for Photothermal-Assisted Hydrogen Evolution by S-Scheme Electron Transfer Mechanism. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2025, 42, 100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesseha, Y. A.; Kuchayita, K. K.; Su, W.-N.; Chiu, C.-W.; Cheng, C.-C. Organic-Inorganic Conjugated Polymer-Exfoliated Tungsten Disulfide Nanosheet P-N Heterojunction Composites for Efficient and Stable Hydrogen Evolution Reactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 509, 161501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Deng, R.; Qin, Z.; Shi, F.; Zeng, J.; Zhao, C.; Pu, Y.; Duan, T. Effective Charge Separation in CdS@PANI Heterostructure for Ultrafast Visible Light-Driven Photocatalytic Reduction of Uranium(VI). Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lu, Q.; Guo, E.; Wei, M.; Pang, Y. Hierarchical Co9S8/ZnIn2S4 Nanoflower Enables Enhanced Hydrogen Evolution Photocatalysis. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 4541–4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, F. Fabrication of Two-Dimensional Ni2P/ZnIn2S4 Heterostructures for Enhanced Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 353, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, X.; Xue, Y.; Liu, W.; Tian, J. Dual Cocatalysts and Vacancy Strategies for Enhancing Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production Activity of Zn3In2S6 Nanosheets with an Apparent Quantum Efficiency of 66.20%. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 640, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Sun, S.; Li, X.; Wang, N.; Wang, X.; Tao, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, B.; Li, X. Ultrasensitive Ammonia Sensor with Excellent Humidity Resistance Based on PANI/SnS2 Heterojunction. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 487, 137181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, J.; Kampermann, L.; Mockenhaupt, B.; Behrens, M.; Strunk, J.; Bacher, G. Limitations of the Tauc Plot Method. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2304523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarina, S.; Waclawik, E. R.; Zhu, H. Photocatalysis on Supported Gold and Silver Nanoparticles under Ultraviolet and Visible Light Irradiation. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Q.; Miao, T.; Wang, H.; Tang, J. Insight on Shallow Trap States Introduced Photocathodic Performance in N-Type Polymer Photocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2795–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhao, D.; Han, H.; Li, C. A Novel Sr2CuInO3S P-Type Semiconductor Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Production under Visible Light Irradiation. J. Energy Chem. 2014, 23, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xu, Y.; Tang, S.; Shi, W.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.-X.; Zhang, W.-D. Photoreduction of Aqueous Protons Coupling with Alcohol Oxidation on a S-Scheme Heterojunction Photocatalyst MnO/Carbon Nitride. Small 2023, 20, 2306563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, E.; Sung, S.-J.; Yang, K.-J.; Lee, J.; Hoang, V.-Q.; Kadiri-English, B.; Hwang, D.-K.; Kang, J.-K.; Kim, D.-H. Enhanced P-Type Conductivity in Sb2Se3 through Alkali and Alkaline Earth Metal Doping. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 8507–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Wang, L.; Li, K.; Tang, J.; Du, R.; Rao, S.; Wu, M. Donor-Acceptor-Donor Organic Small Molecules as Hole Transfer Vehicle Covalently Coupled Znln2S4 Nanosheets for Efficient Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 35, 2412644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Jin, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, B.; Yang, X.; Su, B.-L. Probing Effective Photocorrosion Inhibition and Highly Improved Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production on Monodisperse PANI@CdS Core-Shell Nanospheres. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 188, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, T.; Xie, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; Ye, K.-H.; Chen, J.; Zou, W.; Shi, J.; Huang, Y. Polypyrrole as Photo-Thermal-Assisted Modifier for BiVO4 Photoanode Enables High-Performance Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boasquevisque, L. M.; Marins, A. A. L.; Muri, E. J. B.; Lelis, M. F. F.; Machado, M. A.; Freitas, M. B. J. G. Synthesis and Evaluation of Electrochemical and Photocatalytic Properties of Rare Earth, Ni and Co Mixed Oxides Recycled from Spent Ni–MH Battery Anodes. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 41, e01036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, C. Heterophase Junction Effect on Photogenerated Charge Separation in Photocatalysis and Photoelectrocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2025, 58, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Shi, W.; Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Shi, Y.; Guo, F.; Kang, Z. Dual-Channels Separated Mechanism of Photo-Generated Charges over Semiconductor Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Evolution: Interfacial Charge Transfer and Transport Dynamics Insight. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).