Submitted:

25 December 2025

Posted:

25 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

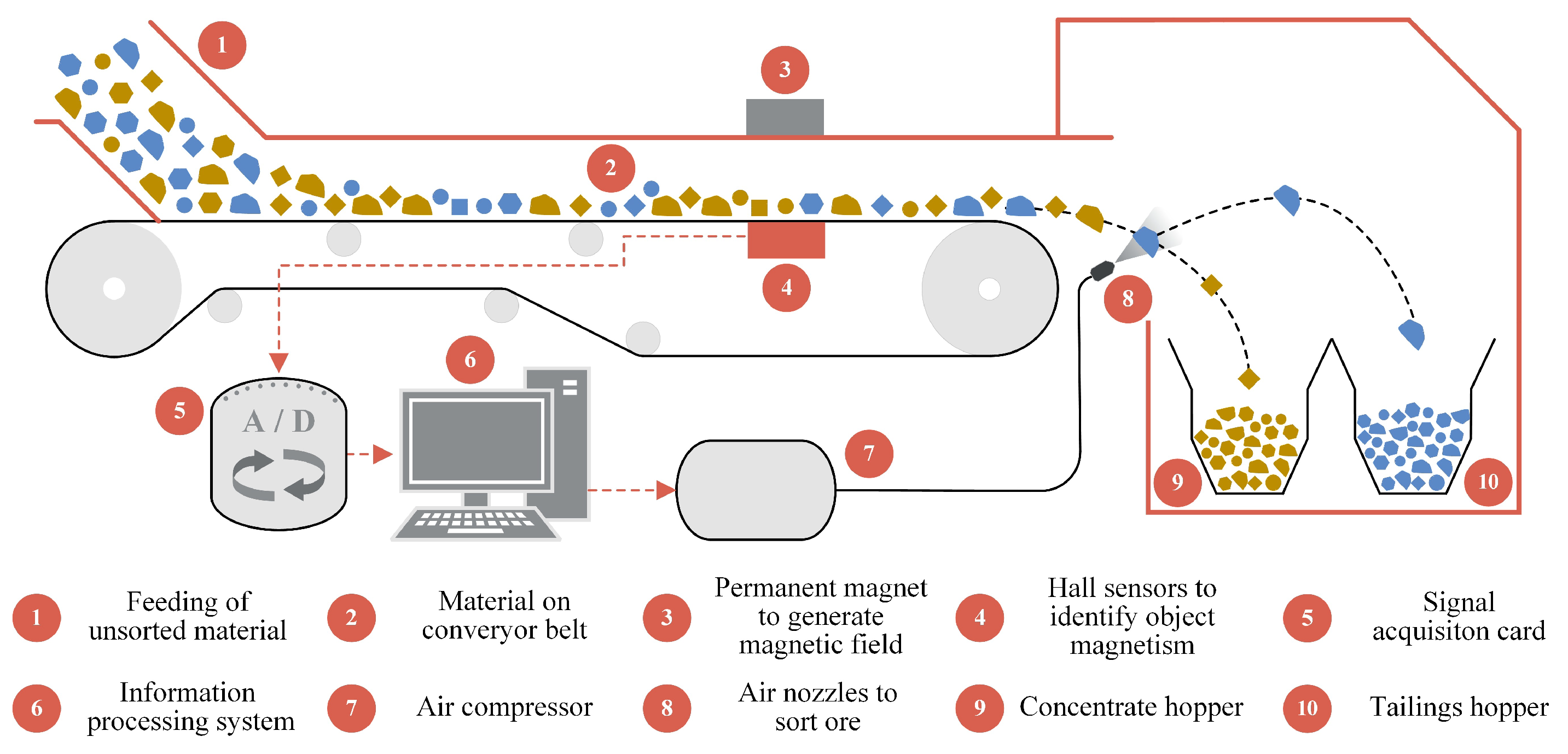

2. Magnetite Ore Sorting System Based on Hall Sensors

2.1. Magnetite Ore Sorting Principle

2.2. Magnetite Ore Sorting Device

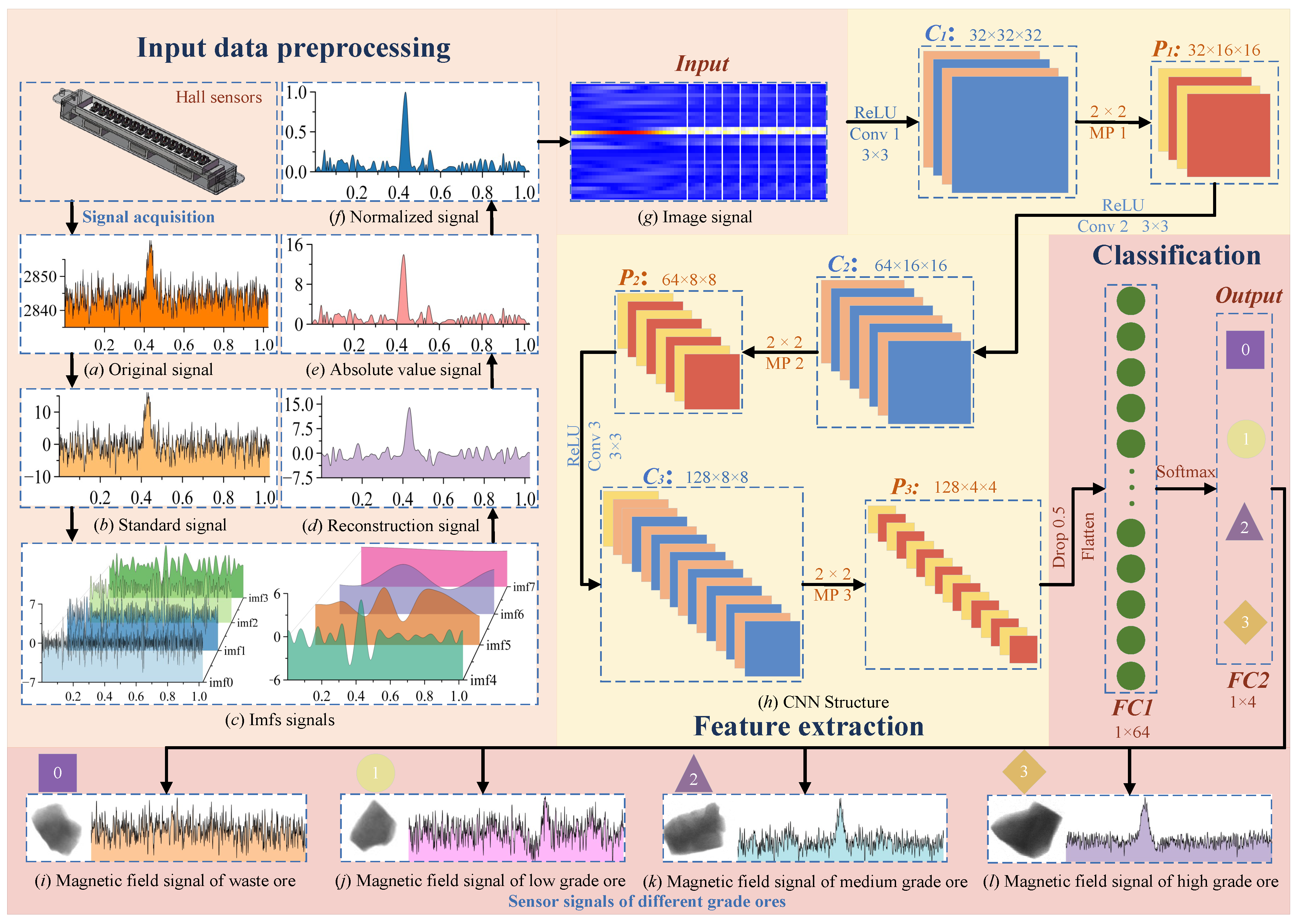

3. Signal Acquisition and Processing

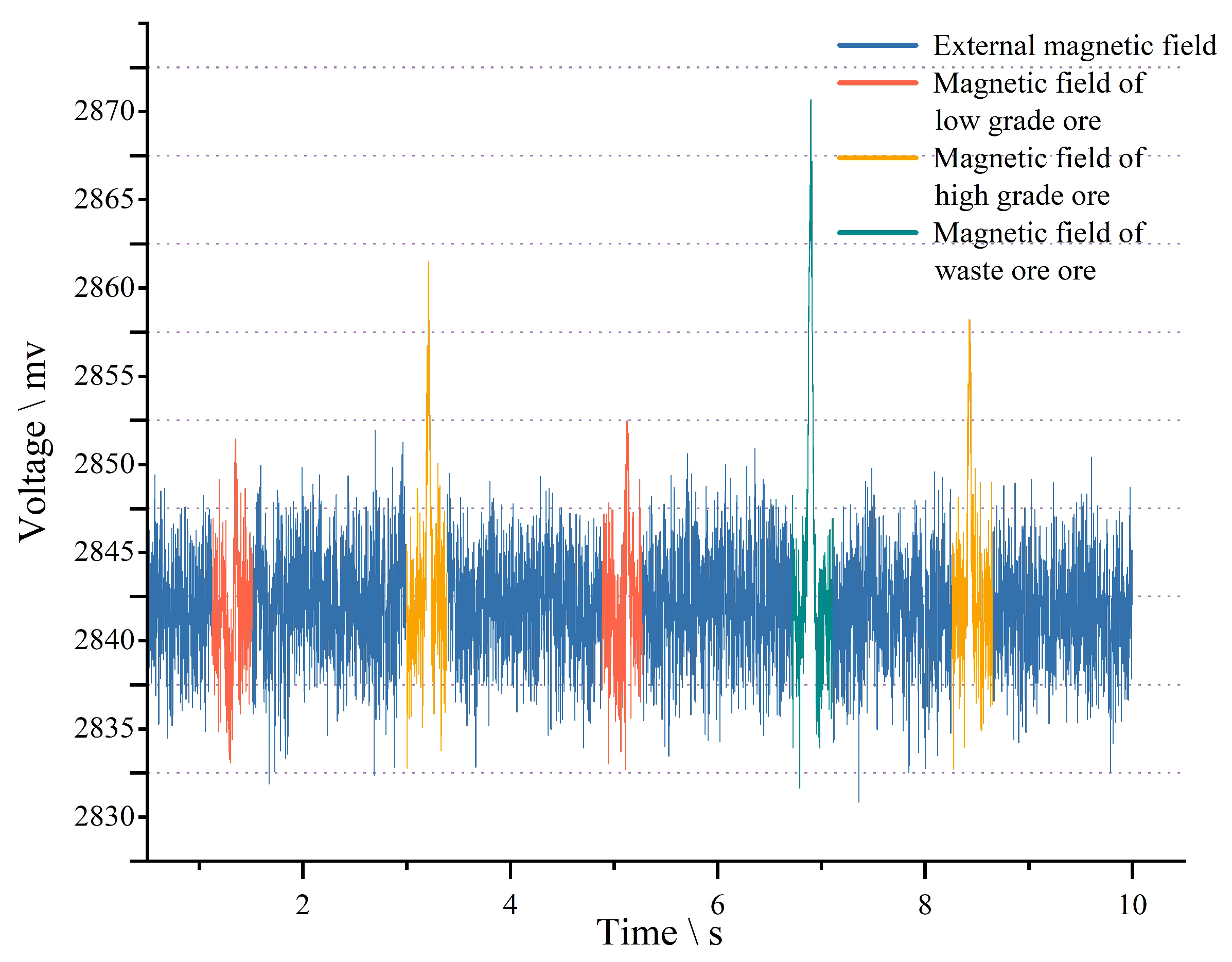

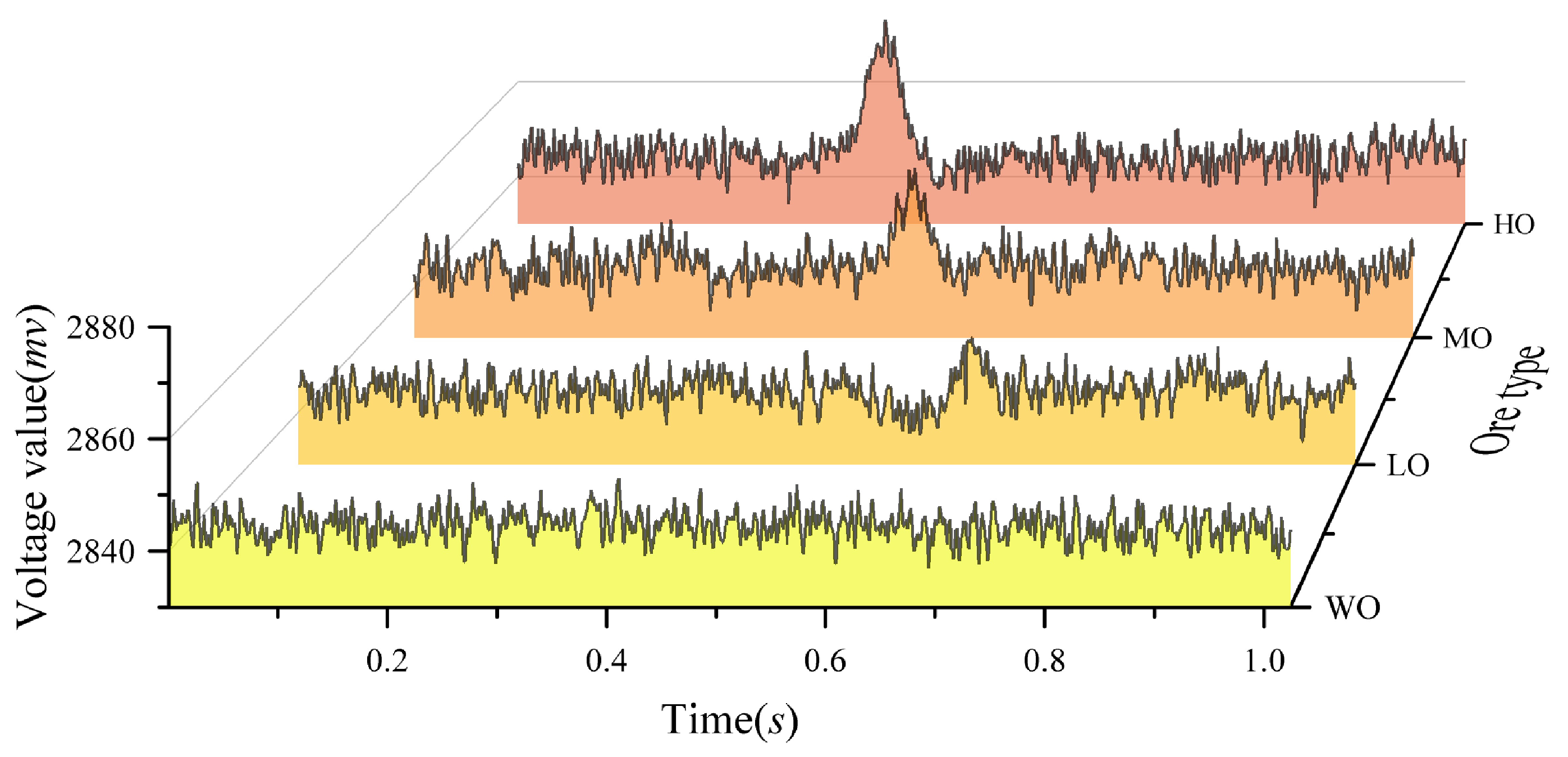

3.1. Signal Acquisition and Standardized Processing

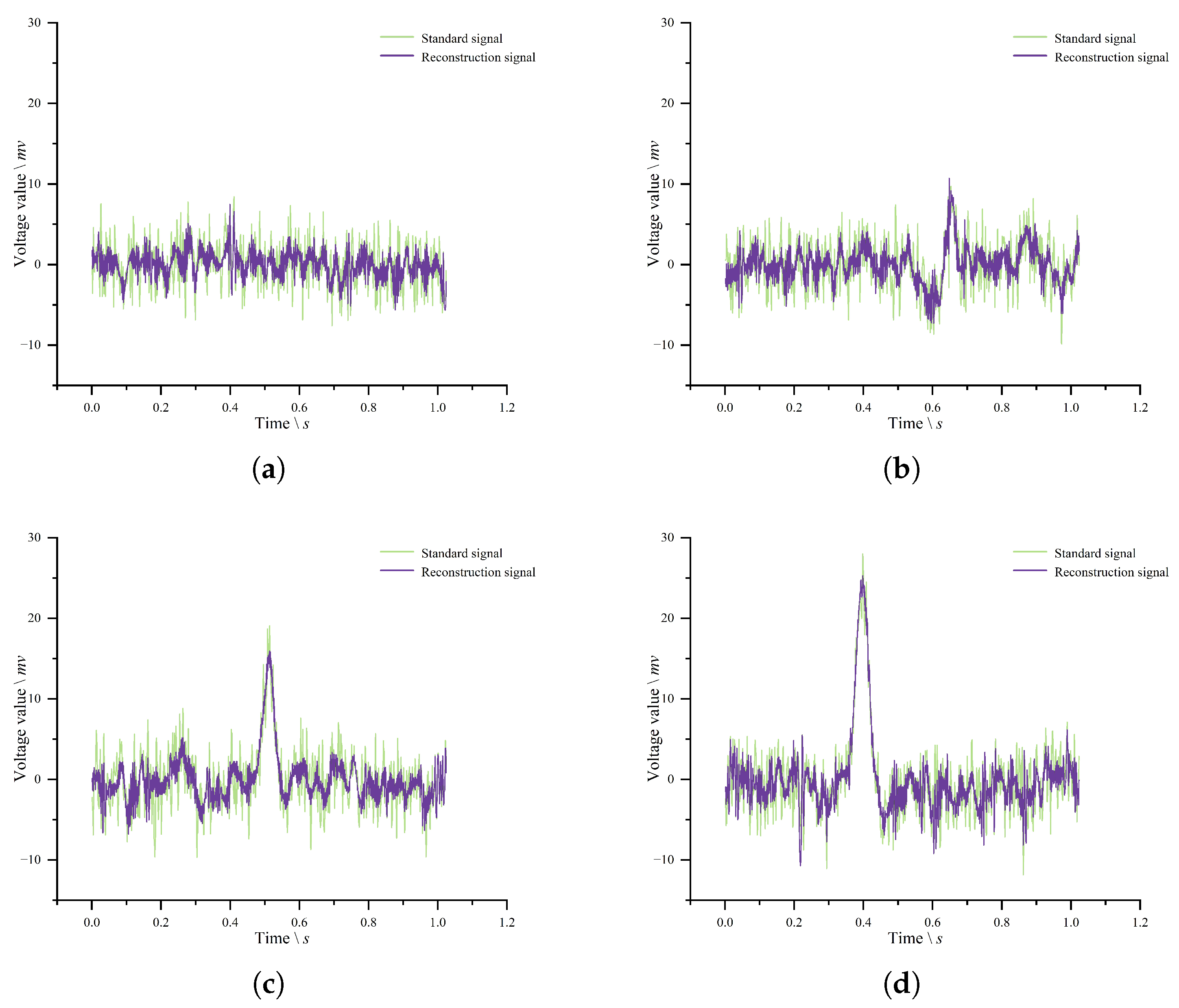

3.2. EMD Decomposition and Reconstruction

- Given the original signal , all local extrema are first identified. The upper envelope and lower envelope are then constructed using cubic spline interpolation of the local maxima and minima, respectively.

- The mean envelope is calculated from and , and the first component is obtained by subtracting from the original signal.

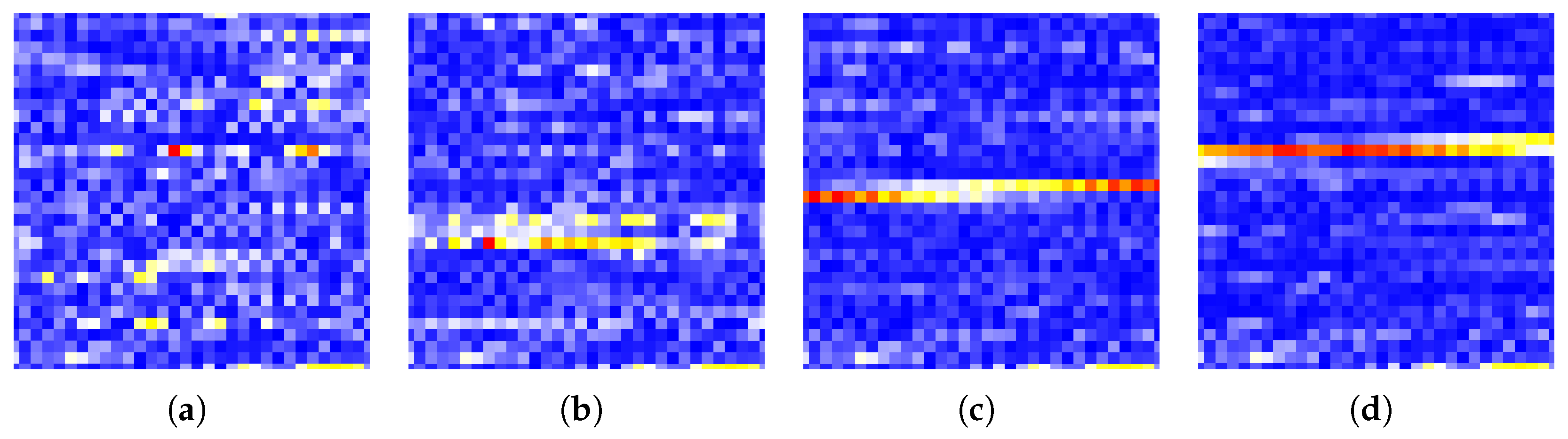

3.3. Establishment of Sample Set

3.3.1. Inversion Processing

3.3.2. Normalization Processing

3.3.3. Dimensionality Transformation

4. Magnetite Ore Identification

4.1. CNN Principle

4.1.1. Convolution Layer

4.1.2. Pooling Layer

4.1.3. Full Connection Layer

4.1.4. Activation Function

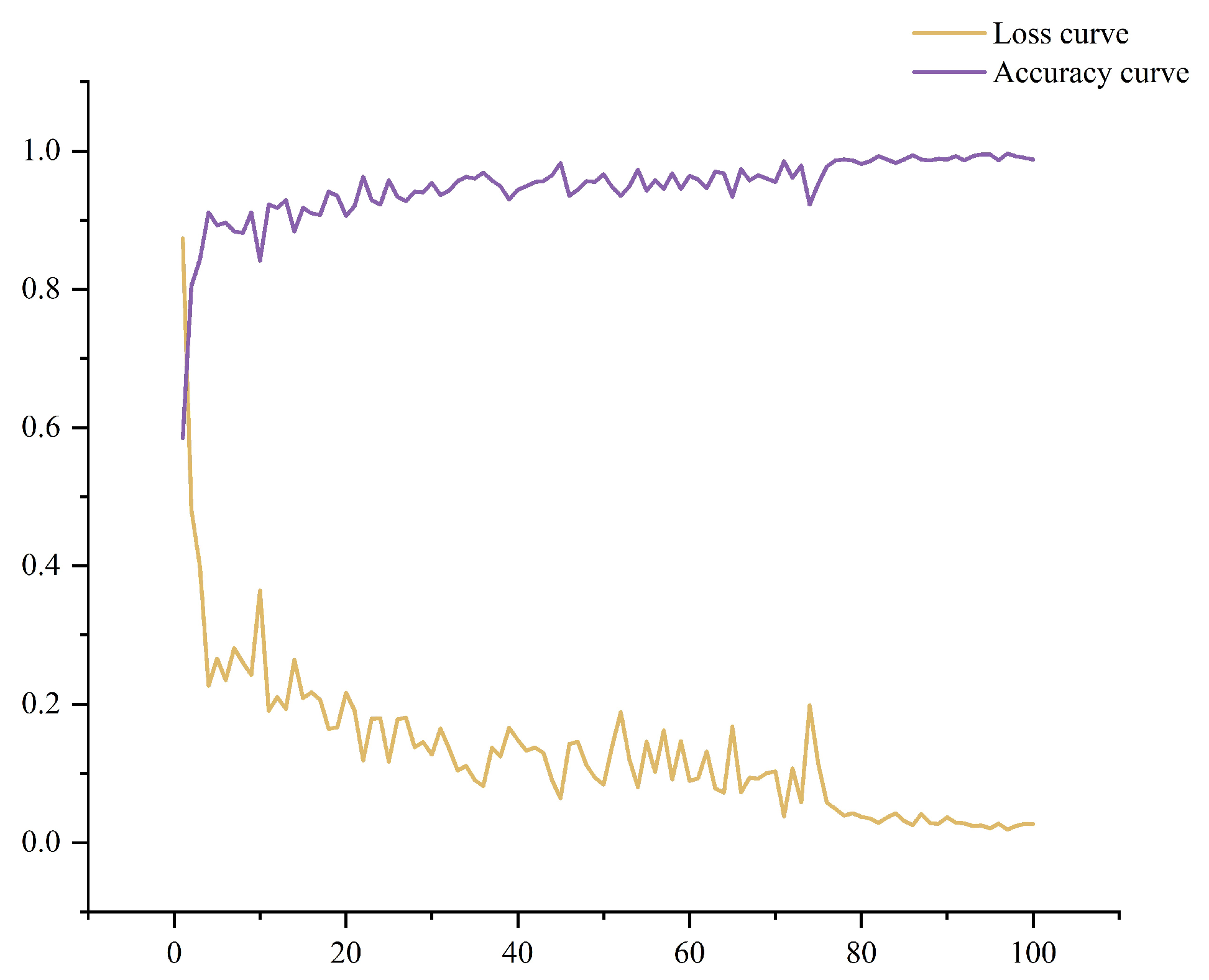

4.2. CNN Structure Design and Training

5. Experiment and Analysis

5.1. Input Data Preprocessing

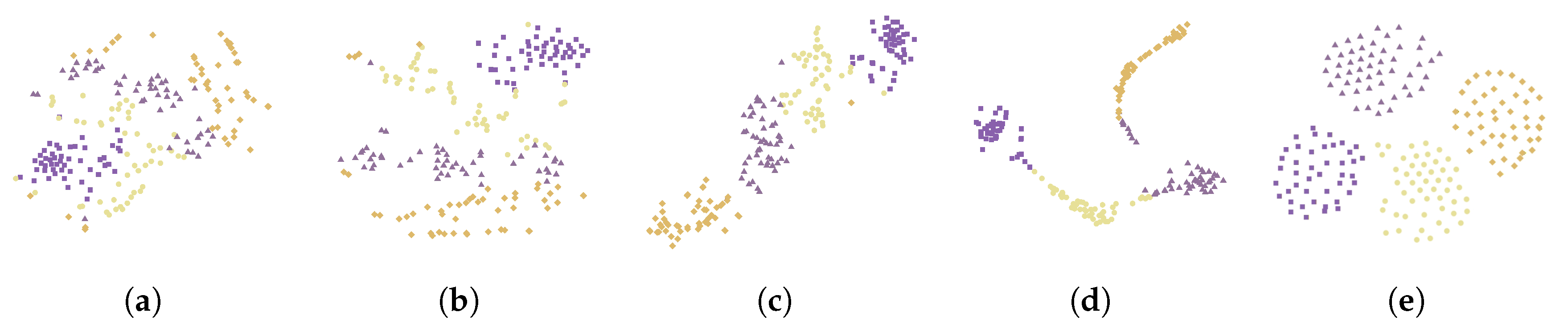

5.2. Feature Extraction

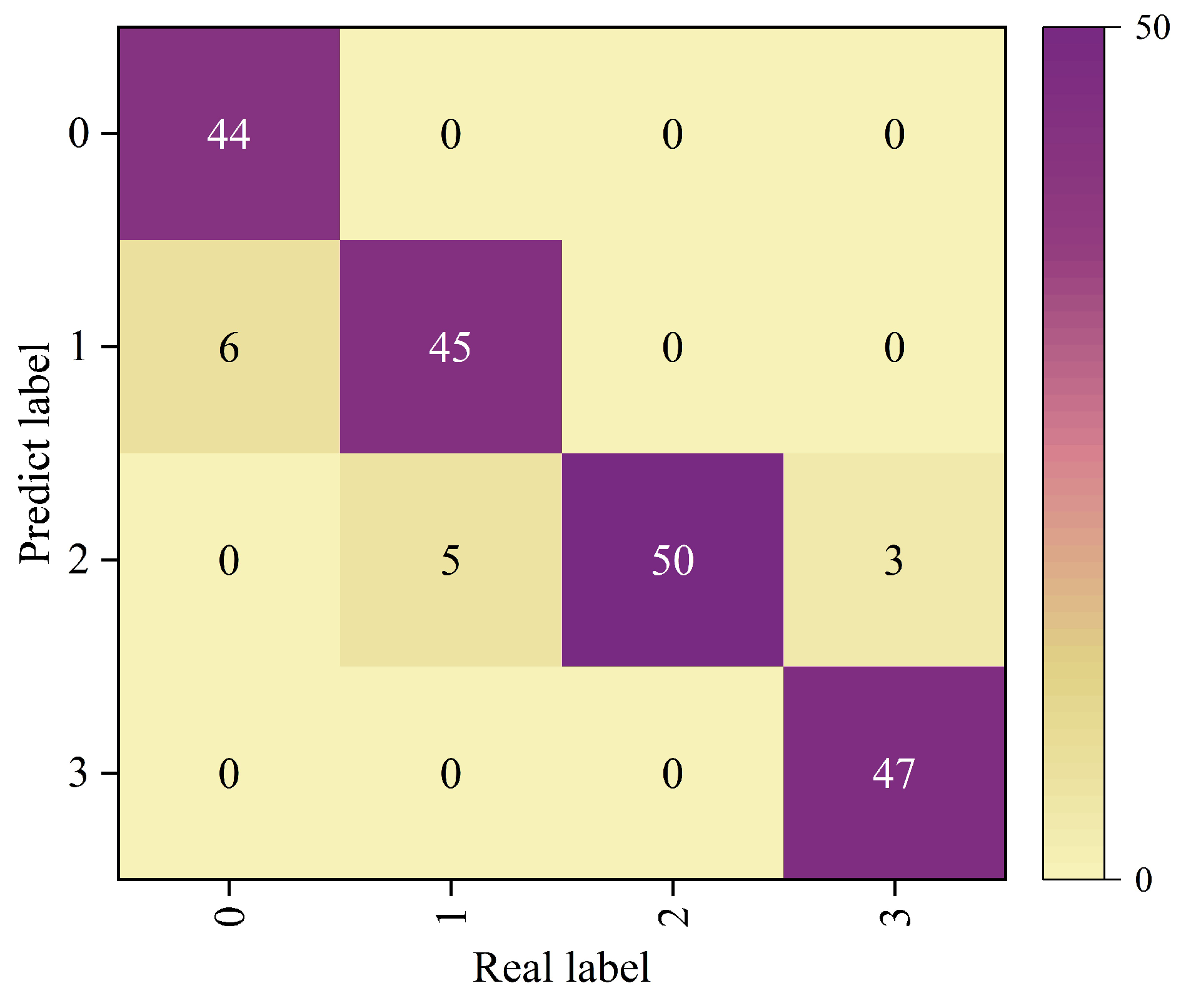

5.3. Result Analysis

5.4. Comparative Analysis

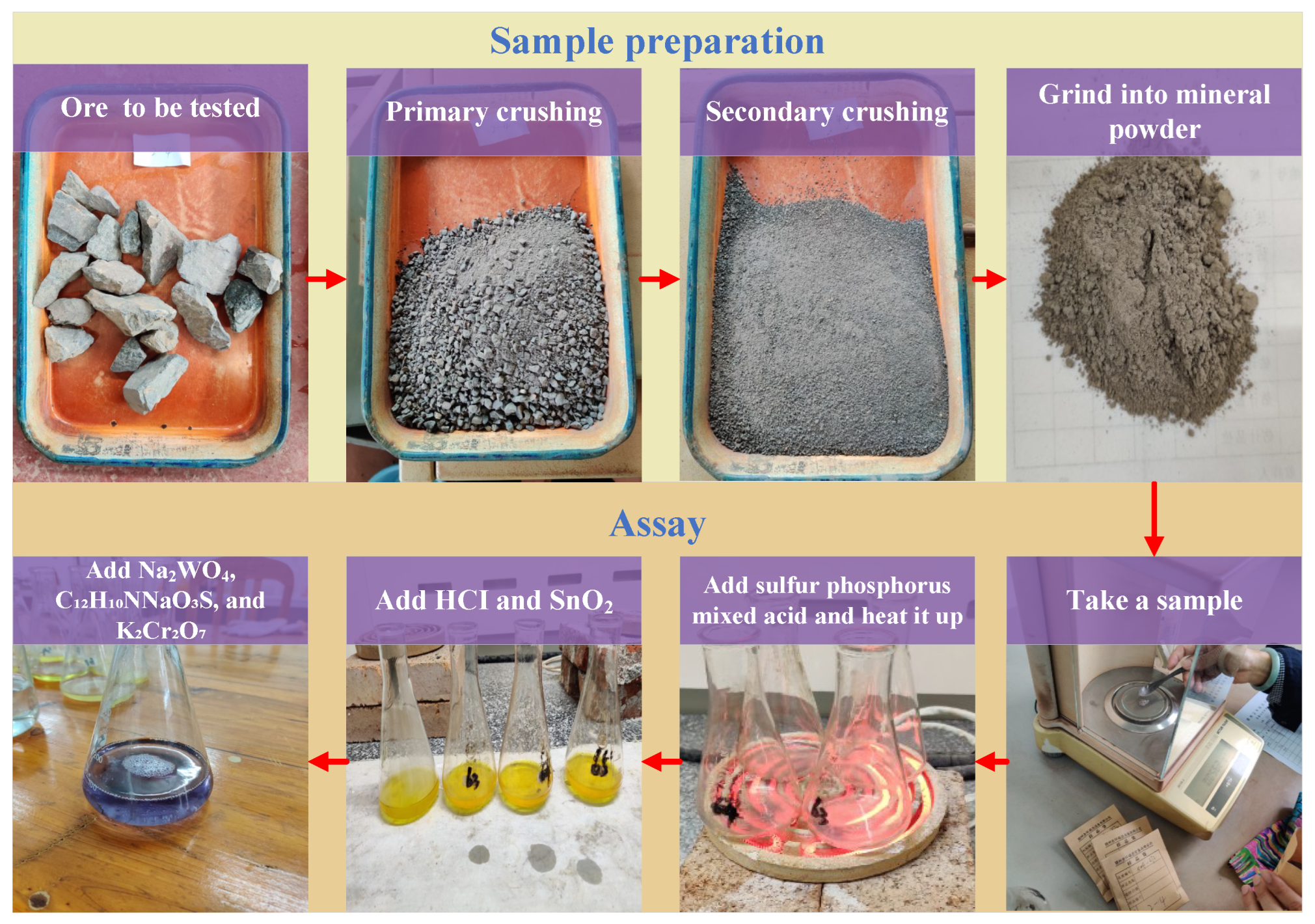

5.5. Ore Grade Assay

6. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baawuah, E.; Kelsey, C.; Addai-Mensah, J.; Skinner, W. Economic and socio-environmental benefits of dry beneficiation of magnetite ores. Minerals 2020, 10, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.; Bamber, A. Mineral sorting. In Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Handbook; Dunne, R. C., Kawatra, S. K., Eds.; Society for Mining,Metallurgy & Exploration: Englewood, CO, USA, 2019; pp. 763–786. [Google Scholar]

- Delwiche, S. R.; Pearson, T. C.; Brabec, D. L. High-speed optical sorting of soft wheat for reduction of deoxynivalenol. Plant Disease 2005, 89, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmack, W. J.; Clark, A. J.; Dong, Y.; Van Sanford, D. A. Mass selection for reduced deoxynivalenol concentration using an optical sorter in SRW wheat. Agronomy 2019, 9, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, B.; Smale, M.; Braun, H. J.; Duveiller, E.; Reynolds, M.; Muricho, G. Crops that feed the world 10. Past successes and future challenges to the role played by wheat in global food security. Food Security 2013, 5, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, N.; Garrinhas, I.; Maximo, A.; Belo, N.; Roque, P.; Carvalho, M. T. Recovery of glass from the inert fraction refused by MBT plants in a pilot plant. Waste Management 2015, 46, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, G.; Serranti, S. Imaging spectroscopy based strategies for ceramic glass contaminants removal in glass recycling. Waste Management 2006, 26, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesina, M. B.; De Jong, T. P. R.; Dalmijn, W. L. Automatic sorting of scrap metals with a combined electromagnetic and dual energy X-ray transmission sensor. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2007, 82, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picón, A.; Ghita, O.; Bereciartua, A.; Echazarra, J.; Whelan, P. F.; Iriondo, P. M. Real-time hyperspectral processing for automatic nonferrous material sorting. J. Electron. Imaging 2012, 21, 013018–013018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäcker, P.; Maier, G.; Gruna, R.; Längle, T.; Beyerer, J. Detecting tar contaminated samples in road-rubble using hyperspectral imaging and texture analysis. In Proc. Opt. Characterization Mater. Conf. 2023, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Paranhos, R. S.; Cazacliu, B. G.; Sampaio, C. H.; Petter, C. O.; Neto, R. O.; Huchet, F. A sorting method to value recycled concrete. J. Cleaner Prod. 2016, 112, 2249–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, S.; Thome, V.; Nühlen, J.; Gruna, R.; Dörmann, J. Baucycle-verwertungsstrategie für feinkörnigen bauschutt. Bauphysik 2018, 40, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollstein, F.; Cacho, Í.; Arnaiz, S.; Wohllebe, M. Challenges in automatic sorting of construction and demolition waste by hyperspectral imaging. In Advanced Environmental, Chemical, and Biological Sensing Technologies XIII 2016, 9862, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert, S.; Dittrich, S.; Bach, J. Recovery of raw materials from ceramic waste materials for the refractory industry. Processes 2021, 9, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegas, I.; Broos, K.; Nielsen, P.; Lambertz, O.; Lisbona, A. Upgrading the quality of mixed recycled aggregates from construction and demolition waste by using near-infrared sorting technology. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 75, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, H.; Benzaazoua, M.; Elghali, A.; Taha, Y.; El Ghorfi, M.; Krause, A.; Hakkou, R. Mine waste rock reprocessing using sensor-based sorting (SBS): Novel approach toward circular economy in phosphate mining. Miner. Eng. 2023, 204, 108415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robben, C.; Condori, P.; Pinto, A.; Machaca, R.; Takala, A. X-ray-transmission based ore sorting at the San Rafael tin mine. Miner. Eng. 2019, 145, 105870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, M. C.; Klein, B.; Futcher, W. A conceptual strategy for effective bulk ore sorting of copper porphyries: exploiting the synergy between two sensor technologies. Miner. Eng. 2023, 201, 108182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatwell, D. G.; Murray, V.; Barton, A. Real-time ore sorting using color and texture analysis. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuşa, L.; Kern, M.; Khodadadzadeh, M.; Blannin, R.; Gloaguen, R.; Gutzmer, J. Evaluating the performance of hyperspectral short-wave infrared sensors for the pre-sorting of complex ores using machine learning methods. Miner. Eng. 2020, 146, 106150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E. G. D.; Brum, I. A. S. D.; Ambrós, W. M. Techniques of pre-concentration by sensor-based sorting and froth flotation concentration applied to sulfide ores–a review. Minerals 2025, 15, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, G.; Gruna, R.; Längle, T.; Beyerer, J. A survey of the state of the art in sensor-based sorting technology and research. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 6473–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robben, C.; Wotruba, H. Sensor-based ore sorting technology in mining–past, present and future. Minerals 2019, 9, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokin, K. S.; Yedilbayev, A. I.; Yedilbayev, B. A.; Yugay, V. D. Dry magnetic separation of magnetite ores. Periódico Tchê Química 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Zeng, J.; Ding, L.; Liu, J. Processing of lean iron ores by dry high intensity magnetic separation. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 1689–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokin, K.; Yedilbayev, A.; Yugai, V.; Medvedev, A. Beneficiation of magnetically separated iron-containing ore waste. Processes 2022, 10, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; He, K.; Zhang, Y.; He, P.; Zhang, Y. A review of intelligent ore sorting technology and equipment development. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2022, 29, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xiong, D. Mineral sorting. In Progress in Filtration and Separation; Tarleton, S., Ed.; Academic Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 287–324. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, G.; Gruna, R.; Längle, T.; Beyerer, J. A survey of the state of the art in sensor-based sorting technology and research. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 6473–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wang, Z.; Kuen, J.; Ma, L.; Shahroudy, A.; Shuai, B.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Cai, J.; Chen, T. Recent advances in convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 77, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Han, S.; Zhu, Y. An enhanced rock mineral recognition method integrating a deep learning model and clustering algorithm. Minerals 2019, 9, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Apel, D. B.; Szmigiel, A.; Chen, J. Image recognition of coal and coal gangue using a convolutional neural network and transfer learning. Energies 2019, 12, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Wan, Z. Ore image classification based on improved CNN. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 99, 107819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, C.; Yang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Wang, R.; Tang, B. Study on photofluorescent uranium ore sorting based on deep learning. Miner. Eng. 2024, 206, 108523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xia, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Song, B.; Bai, Y. Iron ore information extraction based on CNN-LSTM composite deep learning model. IEEE Access 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, J.; Han, Y.; Li, Y. Enhanced pre-selection of spodumene via ultraviolet-induced fluorescence and improved YOLOv8 deep learning algorithm. Miner. Eng. 2025, 230, 109432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, H. H.; Buck, J. A. Engineering electromagnetics, 9rd ed.; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2019; pp. 184–187. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, N. E.; Shen, Z.; Long, S. R.; Wu, M. C.; Shih, H. H.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, H. H. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A: mathematical, physical and engineering sciences 1998, 454, 903–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C. K.; Buldyrev, S. V.; Havlin, S.; Simons, M.; Stanley, H. E.; Goldberger, A. L. Mosaic organization of DNA nucleotides. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 49, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 2002, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G. E.; Srivastava, N.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. R. Improving neural networks by preventing co-adaptation of feature detectors. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1207.0580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, E.; Echeverria, J. C.; Alvarez-Ramirez, J. Detrended fluctuation analysis of heart intrabeat dynamics. Physica A 2007, 384, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaten, L. V. D.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

| Structure | Size | Number | Strides | Padding | Activity function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C 1 | 3×3 | 32 | 1 | Same | ReLU |

| P 1 | 2×2 | 32 | 1 | - | - |

| C 2 | 3×3 | 64 | 1 | Same | ReLU |

| P 2 | 2×2 | 64 | 1 | - | - |

| C 3 | 3×3 | 128 | 1 | Same | ReLU |

| P 3 | 2×2 | 128 | 1 | - | - |

| Flatten | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dropout | - | - | - | - | - |

| FC 1 | - | 64 | - | - | ReLU |

| FC 2 | - | 4 | - | - | SoftMax |

| Sample set | Grade | Label | Training set | Test set | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waste ore | 0 | 200 | 50 | 250 | |

| Low-grade ore | 1 | 200 | 50 | 250 | |

| Medium-grade ore | 2 | 200 | 50 | 250 | |

| High-grade ore | 3 | 200 | 50 | 250 | |

| Sum | - | - | 800 | 2000 | 1000 |

| Ore types | IMF0 | IMF1 | IMF2 | IMF3 | IMF4 | IMF5 | IMF6 | IMF7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WR | 0.069 | 0.156 | 0.372 | 0.755 | 1.180 | 1.622 | 1.931 | - |

| LR | 0.053 | 0.183 | 0.424 | 0.742 | 1.249 | 1.629 | 1.858 | 2.036 |

| MR | 0.061 | 0.195 | 0.428 | 0.982 | 1.296 | 1.738 | 1.841 | - |

| HR | 0.098 | 0.214 | 0.479 | 0.905 | 1.458 | 1.669 | 1.892 | 2.013 |

| Ore types | IMF0 | IMF1 | IMF2 | IMF3 | IMF4 | IMF5 | IMF6 | IMF7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WR | 3.85 | 3.03 | 2.89 | 2.88 | 2.32 | 2.58 | 1.75 | - |

| LR | 3.29 | 3.17 | 3.15 | 4.81 | 5.47 | 3.08 | 1.70 | 1.38 |

| MR | 3.45 | 3.19 | 2.81 | 6.46 | 2.23 | 3.40 | 1.96 | - |

| HR | 5.61 | 3.18 | 3.17 | 7.49 | 7.62 | 3.53 | 1.71 | 1.72 |

| Ore types | CNN prediction | EMD-CNN prediction |

|---|---|---|

| WR | 76.1% | 88% |

| LR | 90% | 90% |

| MR | 82.2% | 100% |

| HR | 94% | 94% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).