Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

25 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

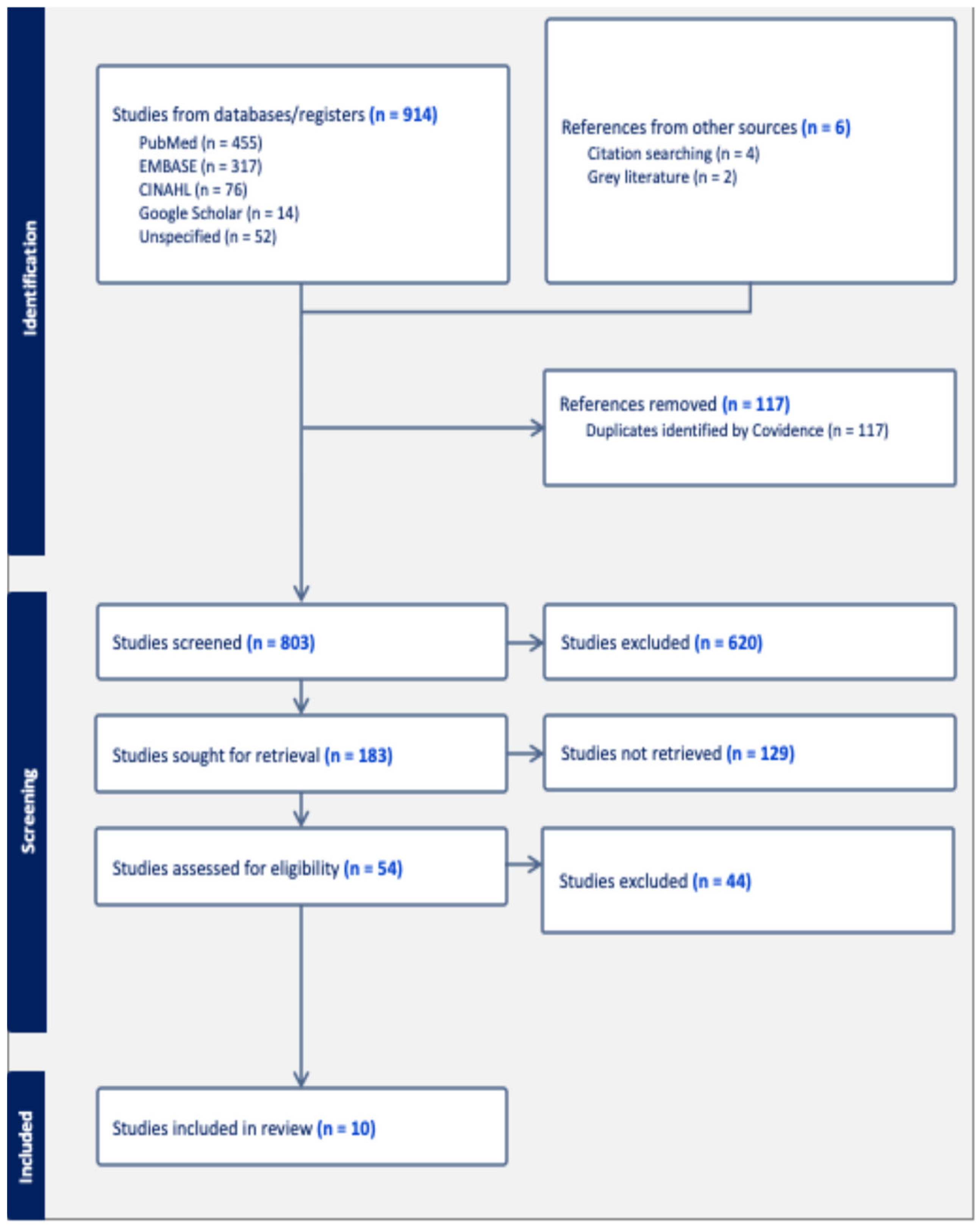

Background: Cardiometabolic risk (CMR), including obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and impaired glucose regulation, disproportionately affects Hispanic/Latinx adults in the United States (U.S.). Although plant-forward dietary patterns are established as cardioprotective, less is known about how dietary patterns within Hispanic/Latinx subgroups relate to CMR. Methods: A narrative review was conducted of observational studies among U.S. Hispanic/Latinx adults (≥18 years) examining defined dietary patterns (a priori, a posteriori, or hybrid) in relation to CMR outcomes (e.g., BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, glucose, lipids). Risk of bias was assessed using an adapted Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. Results: Ten studies met inclusion criteria, including Seventh-day Adventist Latinx, Puerto Rican adults, Mexican American adults, Hispanic women, and a national Hispanic cohort. Plant-forward dietary patterns were associated with lower BMI and waist circumference, lower triglycerides and fasting glucose, and higher HDL-C. In contrast, energy-dense patterns characterized by refined grains, added sugars, processed meats, fried foods, solid fats, and sugar-sweetened beverages were associated with greater adiposity, poorer lipid profiles, and higher blood pressure. Traditional rice-and-beans–based patterns observed in Puerto Rican and Mexican American groups were associated with central adiposity and higher metabolic syndrome prevalence, despite modestly higher intakes of fruits, vegetables, and fiber. Study quality ranged from good (n = 4) to very good (n = 6). Conclusions: Across Hispanic/Latinx subgroups, plant-forward dietary patterns were associated with favorable cardiometabolic profiles, whereas refined and animal-based patterns aligned with higher CMR. Culturally grounded dietary counseling, along with additional longitudinal and intervention studies, is needed to support cardiometabolic health in these populations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Outcomes

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.6. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Risk of Bias

3.2. Sample Characteristics

3.3. Study Characteristics

3.4. Association between dietary patterns and CMR outcomes

3.4.1. Adiposity: BMI, and Central Adiposity (WC)

3.4.2. Blood Pressure (BP)

3.4.3. Lipid Profile: HDL-C, LDL-C, and Triglycerides

3.4.5. Glycemic Outcomes, Type 2 Diabetes and Metabolic syndrome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHS-2: | Adventist Health Study–2 |

| AMEN: | Adventist Multiethnic Nutrition Study |

| BMI: | body mass index (kg/m²) |

| BP: | blood pressure (mmHg) |

| BPRHS: | Boston Puerto Rican Health Study |

| BRFSS: | Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System |

| CHD: | coronary heart disease |

| CI: | confidence interval |

| CMR: | cardiometabolic risk |

| CMD: | cardiometabolic diseases |

| CVD: | cardiovascular disease |

| DBP: | diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

| DP: | dietary pattern |

| DASH: | Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension |

| EPIC: | European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition |

| FBG: | fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) |

| FFQ: | food frequency questionnaire |

| FG: | fasting glucose (mg/dL) |

| HbA1c: | hemoglobin A1c (%) |

| HCHS/SOL: | Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos |

| HDL-C: | high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL) |

| HEI: | Healthy Eating Index |

| LDL-C: | low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL) |

| MetS: | metabolic syndrome |

| MI: | myocardial infarction |

| NHANES: | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| NOS: | Newcastle–Ottawa Scale |

| ns: | not significant |

| NYC: | New York City |

| OR: | odds ratio |

| OW/OB: | overweight/obese |

| PBD: | plant-based diet |

| PICO: | Population, Intervention/Exposure, Comparison, Outcome |

| PR: | Puerto Rican |

| RCT: | randomized controlled trial |

| RoB: | risk of bias |

| RRR: | reduced rank regression |

| SDA: | Seventh-day Adventist |

| SBP: | systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

| SES: | socioeconomic status |

| SPAN: | School Physical Activity and Nutrition |

| SWFFQ: | Southwestern Food Frequency Questionnaire |

| T2DM: | type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TG: | triglycerides (mg/dL) |

| U.S.: | United States |

| UEI: | Unhealthy Eating Index |

| WC: | waist circumference (cm) |

| WHO: | World Health Organization |

References

- Kirk, E.P.; Klein, S. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of the cardiometabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2009, 11, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Koyama, A.K. Prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases among racial and ethnic subgroups in adults—behavioral risk factor surveillance system, United States, 2013–2021. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2024, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hearn, M.; et al. Trends and disparities in cardiometabolic health among US adults, 1999-2018. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Cao, Z. Cardiometabolic diseases, total mortality, and benefits of adherence to a healthy lifestyle: a 13-year prospective UK Biobank study. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Appel, L.J.; Van Horn, L. Components of a cardioprotective diet: new insights. Circulation 2011, 123, 2870–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, L.K.; et al. Dietary patterns and health: insights from NESR systematic reviews to inform the dietary guidelines for Americans. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2024, 56, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; et al. Dietary patterns and cardiometabolic health: Clinical evidence and mechanism. MedComm 2023, 4, e212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micha, R.; Michas, G.; Mozaffarian, D. Unprocessed red and processed meats and risk of coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes–an updated review of the evidence. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2012, 14, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality—a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1029–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clem, J.; Barthel, B. A look at plant-based diets. Mo. Med. 2021, 118, 233. [Google Scholar]

- Satija, A.; Hu, F.B. Plant-based diets and cardiovascular health. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 28, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Part, D. Chapter 8: Dietary Patterns. In Guidelines Advisory Committee; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schiavenato, M.; Chu, F. PICO: What it is and what it is not. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 56, 103194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babineau, J. Product review: Covidence (systematic review software). J. Can. Health Libr. Assoc. /J. De L'association Des Bibliothèques De La Santé Du Can. 2014, 35, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abesig, J.; et al. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies. 2020, 12, 10.1371. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, H.; et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes in two groups of Hispanic Americans with differing dietary habits. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1999, 18, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, S.E.; et al. A traditional rice and beans pattern is associated with metabolic syndrome in Puerto Rican older adults. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1360–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Campo, Y.E. Dietary Patterns Associated with Cardiometabolic Risk for Puerto Ricans with and Without Diabetes, and the Psychosocial Health Correlates of Adherence to the Disease-Related Patterns; The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, P.M.; Gao, X.; Tucker, K.L. A study of dietary patterns in the Mexican-American population and their association with obesity. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1735–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, B.; Haemer, M.A. Dietary patterns and their association with cardiometabolic biomarkers and outcomes among Hispanic adults: a cross-sectional study from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2013–2018). Nutrients 2023, 15, 4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.N.; et al. Plant-based diets are associated with lower adiposity levels among Hispanic/Latino adults in the Adventist Multi-Ethnic Nutrition (AMEN) study. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; et al. Plant-based diets in hispanic/latino adult adventists in the United States and their association with body mass index. Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnik, T.A.; Spence, M.M.; Hosler, A.S. Fat-related dietary behaviors of adult Puerto Ricans, with and without diabetes, in New York City. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reininger, B.; et al. Healthy eating patterns associated with acculturation, sex and BMI among Mexican Americans. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1267–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Gastélum, M.; et al. Dietary patterns with healthy and unhealthy traits among overweight/obese Hispanic women with or at high risk for type 2 diabetes. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 8, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, H.S.J.; et al. Effects of plant-based diets on anthropometric and cardiometabolic markers in adults: an umbrella review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Re, A.; Aspry, K. Update on plant-based diets and cardiometabolic risk. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2022, 24, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashugi, L.; et al. Lifestyle-related behavior and self-reported health status among Seventh-day Adventists. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2023, 15598276231184401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; et al. Optimal dietary patterns for prevention of chronic disease. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satia-Abouta, J.; et al. Dietary acculturation: applications to nutrition research and dietetics. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, N. Acculturation, socioeconomic status, and health among Hispanics. Napa Bull. 2010, 34, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegria, K.; et al. How socioeconomic status and acculturation relate to dietary behaviors within Latino populations. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022, 36, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignatius, T.; Shelly, L. Clinical Epidemiology Workshop 6—Sources of bias in cross-sectional studies; summary on sources of bias for different study designs. Hong Kong Med. J. 2012, 18, 226. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, Z. Cross-sectional studies: strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations. Chest 2020, 158, S65–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First author, year | Selection (Max 5) |

Comparability (Max 2) |

Outcome (Max 3) |

Total | Quality | Notes (Sampling, Adjustment, Validation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singh et al., 2019 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | Very Good | Non-random sampling recruited from SDA churches; adjusted models (age, sex, education); validated Epic Oxford FFQ; objective outcomes not self-reported; no non-response comparison. |

| Alexander et al., 1999 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | Very Good | Non-random convenience sampling through churches; adjusted models (age, sex, BMI, WC); validated FFQ; objective outcomes not self-reported (anthropometric/labs); no non-respondent data. |

| Jaceldo-Siegl et al., 2019 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | Good | Cohort from Adventist Health Study 2 (AHS-2); adjusted models (age, sex, lifestyle); validated FFQ; self-reported outcome (BMI). No non-respondent data. |

| Noel et al., 2009 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 10 | Very Good | Sample from BPRHS using block enumeration; fully adjusted models (SES, behaviors, medications); validated FFQ; objective biomarkers; reasons for exclusions/dropouts fully described. |

| Del Campo, 2020 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 10 | Very Good | Sample from BPRHS; multivariable adjustment (age, SES, lifestyle); validated FFQ; objective biomarkers; comparison between included/excluded. |

| Melnik et al., 2006 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | Good | Cohort from BRFSS using random-digit dialing; adjusted models (age, SES, lifestyle); validated diet behavior tool; outcomes self-reported; no non-response comparison. |

| Carrera et al., 2007 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | Very Good | NHANES probability sampling; adjusted models (age, sex, SES); validated 24-hr recall; objective anthropometrics; non-response data not reported. |

| Reininger et al., 2017 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 | Good | Sample from Cameron County Hispanic Cohort (random); adjusted models (age, sex, education); School Physical Activity & Nutrition (SPAN) recall; objective outcomes not self-reported (BMI); no non-respondent data. |

| Arias-Gastélum et al., 2021 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 8 | Good | Sample from “De Por Vida” RCT (random); unadjusted analyses (correlations only); validated FFQ; objective biomarkers; no non-respondent data. |

| Osborn & Haemer, 2023 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 | Very Good | NHANES probability sampling; multivariable adjustment (age, sex, SES, diet, lifestyle); validated 24-hr recalls; objective biomarkers; exclusions not compared. |

| First author, year | Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | Sample Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seventh-day Adventist Hispanic/Latinx Adults | |||

| Singh et al., 2019 | Inclusion: ≥ 18 years; baptized into SDA church; self-identify as Hispanic/Latinx | Exclusion: self-report of dementia, pregnancy/breastfeeding | Vegetarians vs non-vegetarians: mean age ~54 vs 48 years; women 82.6% vs 66.0%; >college education 73.9% vs 45.1%. Non-vegetarians were slightly more often foreign-born (92.2% vs 87%); years of religiosity did not differ | |

| Alexander et al., 1999 | Inclusion: Self-identify as Hispanic/Latinx; SDA or Catholic affiliation Exclusion: Use of lipid- or diabetes-lowering medications | Mean age similar between SDA and Catholic groups (~42 vs 45 years); years of religiosity did not differ. Lifestyle behaviors: more alcohol (0% vs 42%) and smoking (0 % vs 9.5%) among Catholics; physical activity similar (≈2.0 times/week.) | |

| Jaceldo-Siegl et al., 2019 | Inclusion: SDA adults self-identifying as Hispanic/Latinx with completed assessments (2002–2007) | Exclusion: Incomplete or missing FFQ, anthropometric or lifestyle data | Mean age across DPs ~50 years; women in semi/pesco-vegetarian (~72%) vs non-vegetarians (65.6%); PBD more often had >college education (42.6%) vs non-vegetarian (33.8%); PBD slightly more often foreign-born (63.8%) vs no-vegetarian (58%) | Lifestyle behaviors: PBD more often never-smokers (84.2 % vs 80.8%) and never-drinkers (66.3% vs 51.2%) than non-vegetarian | |

| Puerto Rican Adults | |||

| Noel et al., 2009 | Inclusion: Puerto Rican adults aged 45–75 years | Exclusion: Incomplete or implausible FFQ data; serious illness preventing participation; no permanent address; relocation within 2 years | Across the highest quantile (Q5) of all DPs, Age (years): Traditional PR pattern (59) > Sweets pattern (56.9) > Meat pattern (54.6); Female: Sweets pattern (76.2%) > Traditional PR pattern (75.3%) > Meat pattern (53.2%); <8th-grade education: Traditional PR pattern (59.4%) > Sweets pattern (52.3%) > Meat pattern (41.6%); Acculturation (higher score = more acculturated): Meat pattern (24.6) > Sweets pattern (24.1) > Traditional PR pattern (19.2) | Lifestyle behaviors: Smoking (current): Meat pattern (37.2%) > Sweets pattern (30.0%) > Traditional PR pattern (23.9%); Alcohol (current): Meat pattern (53.2%) > Sweets pattern (34.6%) > Traditional PR pattern (33.5%) | |

| Del Campo et al., 2020 | Inclusion: Puerto Rican adults 45-75 years | Exclusion: Incomplete or missing data; antilipemic medications; implausible dietary intake | Across the highest tertile (T3) of both diabetes and non-diabetes DP scores: Age (years): Diabetes (55.9) > No-Diabetes (52.6); Female: No-Diabetes (56%) < Diabetes (60%); Less than 8th grade education: Diabetes (45%) > No-Diabetes (37%); BMI: Diabetes (33.5 kg/m²) > No-Diabetes (29.3 kg/m²) | Lifestyle behaviors: Current cigarette smoker: No-Diabetes (39%) > Diabetes (23%); Alcohol use (past year [%]): Diabetes (46%) < No diabetes (52%) | |

| Melnik, 2006 | Inclusion: ≥18 years; self-identify as Puerto Rican; NYC resident; with or without self-reported diabetes | Exclusion: Not reported | Predominantly younger adults, with 64% aged 18–44 years, 55.8% were women. 33.8% had >high school education; 52.9% were U.S.-born, and most were nonsmokers (70.8%). The prevalence of diagnosed diabetes in this population was 11.3% | |

| Study | Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | Sample Characteristics | |

| Mexican American Adults | |||

| Carrera et al., 2007 | Inclusion: ≥ 18 years. | Exclusion: Pregnancy, or breastfeeding; extreme energy intake, missing data | Men were slightly younger than women (36.1 vs 38.7 years); WC> cutoff (%): Men 34.4 % vs Women 70 %; Smoking (%): Men 26.8 % vs ↓ Women 13.9 %; Overweight: Men 24.5 % vs Women 36 %; Obese: Men 47.2 % vs Women 38 % Educational attainment and income were similar across sexes. |

|

| Reininger et al., 2017 | Inclusion: ≥ 18 years; Exclusion: pregnancy, or breastfeeding. extreme energy intake, missing data | Age (≥36 years): 68.4%; Sex: ~55% women; Education (>8 years): 72.04%; Weight Status: OW/OB 85.7%; Diabetes prevalence: 24.7%; Language: Spanish-speaking preference: 68.0%; Generation: 1st-gen Mexican American 60.3% | |

| Hispanic Women | |||

| Arias-Gastélum et al., 2021 | Inclusion: ≥ 18 years; self-identify as Hispanic; BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2; have diabetes or pre-diabetes. | Exclusion: cancer treatment in the past 2-year: psychiatric hospitalization; on weight loss meds over past 6-months; pregnancy/breastfeeding | Mean age 44 years; mean BMI 36.4 kg/m²; 86% obese; mean WC 115.4 cm; mean FBG 135 mg/dL; mean HbA1c 6.5%. Sugar & fat-laden and meat & snacks patterns associated with younger age. | |

| Multicultural Hispanic U.S. Adults | |||

| Osborn & Haemer, 2023 | Inclusion: ≥ 18 years; self-identify as Mexican American or “other Hispanic” | Exclusion: Missing dietary recalls, or sociodemographic data. | Sex: 51.7% women; Incomes of USD ≥35,000 per year: 57.8%; Education (≤high school): 34.6%, and 43.6% had at least some college. U.S.-born: 49.1%, having lived in the U.S. ≥10 or more years: 40.3%. Mexican Americans sample: 62.3%; other Hispanic origin: 37.7% | |

| First Author, Year |

Objective | Analysis / Sample / Outcomes |

Dietary Assessment and Pattern Method |

Dietary Patterns | Key Results | Conclusion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seventh-day Adventist Hispanic/Latinx Adults | |||||||||

| Singh et al., 2019 | Examine whether plant-based dietary (PBD) patterns are associated with adiposity | Cross-sectional; n = 74 SDA Hispanic/Latinx adults (AMEN Study); outcomes: BMI, WC, SBP, DBP | 24-h recall plus EPIC-Oxford–adapted FFQ (30-day intake) | 2 DPs: 1) Non-vegetarian; 2) PBD (pescatarian, lacto-ovo, strict vegetarian) | PBD vs non-vegetarian: BMI 24.5 vs 27.9 kg/m² (↓); WC 88.4 vs 95.2 cm (↓); BP ns | Higher plant-based intake associated with healthier adiposity markers | |||

| Alexander et al., 1999 | Compare CVD and T2DM risk factors between SDA vegetarians and Catholic omnivores | Cross-sectional; n = 74 SDA vs n = 45 Catholic Hispanic adults; outcomes: BMI, WC, SBP, DBP, TG, glucose, HDL-C, LDL-C | FFQ (3-month intake) | 2 DPs: 1) Vegetarians (lacto-ovo/strict); 2) omnivores | Vegetarians vs omnivores: BMI 27.2 vs 31.4 kg/m²; WC 89.2 vs 99.3 cm; SBP 109.8 vs 117.1 mmHg; TG 152 vs 229 mg/dL; glucose 88.9 vs 103.4 mg/dL; HDL-C 44.5 vs 39.9 mg/dL | SDA vegetarians exhibited lower cardiometabolic risk | |||

| Jaceldo-Siegl et al., 2019 | Characterize PBD patterns and examine BMI associations | Cross-sectional; n = 3,475 Hispanic/Latinx SDAs (AHS-2); outcomes: BMI | 1-year FFQ validated with six 24-h recalls | 2 DPs: 1) non-vegetarian; 2) PBD (vegetarian, pesco-vegetarian, semi-vegetarian) | BMI (% difference vs non-vegetarian): vegan −14.3%; vegetarian −8.2%; pesco-vegetarian −4.2%; semi-vegetarian −2.96% (ns) | Greater adherence to PBD strongly associated with lower BMI | |||

|

First Author, Year |

Objective | Analysis / Sample / Outcomes |

Dietary Assessment and Pattern Method |

Dietary Patterns | Key Results | Conclusion | |||

| Puerto Rican Adults | |||||||||

| Noel et al., 2009 | Identify dietary patterns and associations with metabolic syndrome (MetS) | Cross-sectional; n = 1,167 PR adults (BPRHS); outcomes: MetS | 12-month FFQ validated with plasma carotenoids; Method: factor analysis | 3 DPs: 1) Meat/processed and French fries (“Meats”); 2) Traditional rice/beans (“Traditional PR”); 3) Sweets/sugary beverages and dairy desserts (“Sweets”) | MetS prevalence: Traditional PR > Sweets > Meats (74.5% > 64.9% > 62.1%); Meat Pattern: OR 1.2 [0.76–2.0]; ↑ DBP; Traditional PR: OR 1.7 [1.04, 2.7]; Sweets: OR 1.8 [1.03, 3.3], ↓ HDL-C; ↓fasting glucose | Traditional PR and sweets patterns linked to higher MetS risk and lower HDL, while the Meat pattern linked to ↑ DBP risk | |||

| Del Campo et al., 2020 | Derive dietary pattern scores by diabetes status and examine 2-year CMR change | Cross-sectional plus prospective; n = 703 PR adults (BPRHS); outcomes: HDL-C, TG, LDL-C, SBP, WC | 1-year FFQ; Method: RRR | 2 DPs:a 1) Diabetes DP Score; 2) No-diabetes DP Score |

Cross-sectional: Diabetes DP score ↑ WC; No-diabetes DP score ↓ HDL-C 2-year follow-up: WC ↑ in both groups; Diabetes DP score ↓ LDL-C −4.44 mg/dL [−8.35, −0.54]; No-diabetes DP score ↑ HDL-C 1.03 mg/dL [1.01, 1.05] |

Baseline dietary patterns did not predict 2-year CMR change, but among participants, those without diabetes were more likely to be in the highest tertile of the DP score | |||

| Melnik, 2006 | Assess fat-related dietary behaviors by diabetes status among PR adults | Cross-sectional; n = 1,304 PR adults (NYC BRFSS); outcomes: T2DM | BRFSS fat-related diet habits questionnaire (3-month intake) | Composite fat-related diet score (1–4-point scale, with higher scores = ↑ fat intake). Subscales: 1) Avoid fat as flavoring: 2) Avoid fried foods: 3) Modify meats to be low fat: 4) Substitute fat-modify products |

Diabetes associated with lower fat intake: β −0.27, p = 0.01; interactions: diabetes × family history β 0.19, p = 0.03; diabetes × weight β 0.26, p = 0.02; diabetes × exercise β −0.23, p = 0.01 | Adults with diabetes practiced more practiced more meat-modification and fat-lowering behaviors. Obesity and family history predicted higher fat intake | |||

|

First Author, Year |

Objective | Analysis / Sample / Outcomes |

Dietary Assessment and Pattern Method |

Dietary Patterns |

Key Results | Conclusion | |||

| Mexican American Adults | |||||||||

| Carrera et al., 2007 | Examine dietary patterns and central obesity among Mexican Americans | Cross-sectional; n = 659 Mexican American adults (NHANES 2001–2002); outcomes: BMI, WC | 24-h recall; Method: cluster analysis | 4 DPs: 1) Poultry/alcohol; 2) Milk/baked goods; 3) Traditional Mexican; 4) Meat | BMI similar across patterns at ~28 kg/m²; WC (cm): women: meat 95.2 > poultry 94.2 > traditional Mexican 93.1 > milk/baked 92.0; men: traditional Mexican 97.8 > poultry 95.8 > milk/baked 95.6 > meat 94.2 | All four DPs had high mean BMI. Women in all DPs showed mean WC above the cutoff of 88 cm. |

|||

| Reininger et al., 2017 | Examine healthy and unhealthy dietary patterns and diabetes prevalence in Mexican Americans | Cross-sectional; n = 1,250 Mexican American adults (Cameron County Hispanic Cohort); outcomes: BMI, T2DM | SPAN-adapted 24-h recall plus Method: HEI and UEI |

2 DPs:b(1) Healthy Eating Index, (2) Unhealthy Eating Index | HEI ↑ with age, Spanish preference, first generation; UEI ↑ with acculturation and second generation; no association with BMI or diabetes | Less acculturation (Spanish-preferring, 1st-gen, older adults) → ↑ HEI + ↓ UEI; More acculturation (English-preferring, women, 2nd-gen) → ↑ UEI + ↓ HEI; DPs not associated with BMI or diabetes prevalence | |||

| Hispanic Women | |||||||||

| Arias-Gastélum et al., 2021 | Identify dietary patterns and associations with glycemic risk | Cross-sectional; n = 191 Hispanic women with diabetes or prediabetes; outcomes: FBG, HbA1c | 3-mo intake (SWFFQ); Method: factor analysis | 6 DPs: 1) Sugar/Fat-laden (“Western”); 2) Plant/Fish (“Mediterranean-like”); 3) Soups/Starch (“Traditional.”); 4) Meat/Snacks (“High-fat, processed meat pattern”); 5) Beans/Grains (“Mixed “healthy + processed” pattern”); 6) Eggs/Dairy | Sugar and fat-laden and meat and snacks patterns associated with younger age: β −0.23 and −0.30; plant and fish pattern associated with higher FBG: β 0.15; no associations with BMI, WC, or HbA1c | Sugar/fat-laden and meats/snacks DPs were negatively associated with age. Sugar and fat-laden the plant/fish DP unexpectedly was significantly associated with ↑ FBG | |||

| First Author, Year | Objective | Design / Sample / Outcomes | Dietary Assessment and Pattern Method | Dietary Patterns | Key Results | Conclusion | |||

| Multicultural Hispanic U.S. Adults | |||||||||

| Osborn and Haemer, 2023 | Identify dietary patterns among U.S. Hispanic adults and cardiometabolic associations | Cross-sectional; n = 2,049 Hispanic adults (NHANES 2013–2018); outcomes: BMI, T2DM, body fat, MI, CHD, HDL-C, LDL-C, TG, SBP, DBP | Two 24-h recalls; Methods: factor analysis | 3 DPs:C (1) Solid fats and refined carbohydrates, (2) Vegetables, (3) Plant-based | Solid fats and refined carbohydrates: ↑ BMI β 1.07 [0.14, 1.99], ↓ HDL-C β −4.53 [−7.03, −2.03], ↓ SBP β −2.47 [−4.89, −0.59]; Vegetables: ↓ body fat percentage β −1.57 [−2.74, −0.39], ↓ HDL-C at moderate intake β −2.62 [−4.79, −0.47]; Plant-based: no associations | Energy-dense patterns linked to worse cardiometabolic health. Solid fats/refined carbs DP was associated with ↑ BMI, ↓HDL-C; the vegetable DP was linked to ↓body fat and ↓ HDL-C at moderate intake, and the DP 3 showed no significant associations with CMR factors | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).