1. Introduction

Phosphatidylserine (PS) is a crucial phospholipid that plays an essential role in maintaining brain function [

1,

2]. Predominantly located in the inner leaflet of cell membranes, PS contributes to various neuronal processes, including signal transduction, synaptic transmission, and neuroplasticity [

3,

4]. It is abundant in the brain, comprising 13-15% of the total phospholipid content in the cerebral cortex, where it supports neuronal membrane fluidity and the functional integrity of membrane-bound proteins, including receptors and ion channels [

5,

6]. The binding of PS to key proteins on the cell membrane facilitates the assembly of signaling complexes critical for synaptic transmission and plasticity [

7,

8]. Recent studies have highlighted the neuroprotective effects of PS, particularly in enhancing cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and processing speed [

9,

10]. Clinical trials suggest its potential as a dietary supplement for improving cognition, especially in aging populations and patients with early stages of neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other types of dementia, making it a candidate for addressing age-related cognitive decline [

11,

12].

Emerging evidence suggests that PS supplementation can modulate the expression of key transcriptional coactivators such as Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α or Ppargc1A) [

13,

14]. PGC1α is a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and energy metabolism, enhancing mitochondrial function in response to various physiological stimuli [

15,

16]. In the brain, PGC1α supports energy metabolism, antioxidant defense, and synaptic function, with neuroprotective roles including upregulation of antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase, which mitigate damage from reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

17,

18]. PGC1α also regulates neurotrophic factors essential for synaptic health and neuroplasticity [

19,

20]. Dysregulation of PGC1α is linked to neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and AD, where mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress are prevalent [

21,

22]. Understanding how PS affects Pgc1α expression in neurons could provide valuable insights into potential neuroprotective strategies [

14]. Additionally, Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a protein deacetylase that plays a critical role in cellular aging, metabolic regulation, and neuroprotection, has emerged as a potential modulator of Pgc1α [

23,

24]. SIRT1 can activate PGC1α by deacetylation, enhancing its activity in mitochondrial function, oxidative stress reduction, and neuroprotection [

25,

26]. Given that both SIRT1 and PGC1α are involved in neuroprotective pathways, investigating how PS affects their expression could uncover important mechanisms underlying PS’s potential benefits in neurodegenerative conditions [

27,

28].

In this study, we examined the effect of PS on both Sirt1 and Pgc1α expression using human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived cortical neurons. hESC-derived neurons serve as a reliable model for studying neuronal physiology and disease mechanisms, closely mimicking human cortical neuron properties. By using this model, we aimed to investigate whether the purity of PS impacts its ability to modulate Sirt1 and Pgc1α expression. The purity of supplements like PS can significantly influence their efficacy and safety, as impurities may affect bioavailability, alter pharmacodynamics. Thus, investigating PS purity is essential for optimizing neuroprotective strategies, ensuring consistent therapeutic outcomes, and advancing the use of PS as a combination with other supplements or therapeutic agents in neurodegenerative disease management.

2. Materials and Methods

Preparation of Phosphatidylserine (PS)

80% purity of PS (Notified ingredient No. 2-29, Manufactured by KONO CHEM CO., LTD), 70% and 50% PS (Notified ingredient No. 2-29, CERTIFIED NUTRACEUTICALS, INC.)

Differentiation of Human ESCs into Cortical Neurons

Human H1 embryonic stem cells were differentiated toward a cortical neuronal fate following a published protocol [

29]. Briefly, H1 ESC colonies were released from mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder layers and cultured as aggregates in suspension using human ESC medium lacking FGF2 for 6 days in low-attachment six-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). On day 7, embryoid bodies (EBs) were transferred onto Matrigel-coated plates to promote attachment and the emergence of neuroepithelial rosette-like structures. Rosette-containing aggregates (RONAs) were manually isolated to generate neurospheres, maintained for 24 h, dissociated into single cells, and plated onto laminin/poly-D-lysine–coated plates for downstream experiments. For neuronal maturation/differentiation, cells were maintained in neural differentiation medium consisting of Neurobasal supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen) and the following additives: brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; 20 ng/mL; PeproTech), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF; 20 ng/ml; PeproTech), ascorbic acid (0.2 mM; Sigma), dibutyryl adenosine 3′5′-monophosphate (cAMP; 0.5 mM; Sigma). Patterning factors were applied as indicated: retinoic acid (2 μM), SHH (50 ng/mL), purmorphamine (2 μM), or a combination of retinoic acid + SHH + purmorphamine. All experiments involving human stem cells were conducted under oversight and approval of the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Stem Cell Research Oversight (ISCRO) Committee.

Cell death and Viability Assessment

hESC–derived cortical neurons were exposed to 10 μM Aβ42 (Millipore) for 7 days. To assess cell death, nuclei of all cells were labeled with Hoechst 33342 (7 μM), while membrane-compromised (non-viable) cells were identified by propidium iodide (PI) staining (2 μM; Invitrogen). Fluorescence images were acquired using a Zeiss microscope, and the total number of nuclei and PI-positive cells were quantified using Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss). Cell viability was independently evaluated using the Alamar Blue assay (Invitrogen), with fluorescence measured at an excitation wavelength of 570 nm and an emission wavelength of 585 nm according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Luciferase Reporter Assays

Transcriptional activity of the human PGC1α promoter was assessed using a dual-secreted luciferase reporter system (Secrete-Pair Dual Luminescence Assay, GeneCopoeia). hESC-derived neurons were transfected with a lentiviral construct harboring a 1.3-kb fragment of the human PGC1α promoter (–1,274 to +26 relative to the transcription start site) upstream of a Gaussia luciferase reporter, along with a constitutively expressed secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) control cassette. Three days after transfection, Neurons were transfected with a SIRT1 expression vector and treated with phosphatidylserine (PS) as indicated for 48 h. Culture supernatants were collected for luminescence measurements. Gaussia luciferase activity was quantified by incubating 10 μL of conditioned medium with 100 μL of Gaussia luciferase substrate buffer for 30 s. To measure SEAP activity, aliquots of supernatant (10 μL) were heat-inactivated at 65 °C for 5 min and subsequently incubated with SEAP substrate for an additional 5 min. Gaussia luciferase signals were normalized to corresponding SEAP values to control for variations in transduction efficiency.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNAs from cultured human cortical neurons were extracted using a RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen Sciences, Inc.) and quantified using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). RNA was reverse-transcribed using a high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). cDNAs were amplified with PowerUp™ SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on a StepOnePlus™ system (Applied Biosystems). The amounts of cDNA within each sample were normalized to 18sRNA or glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Sequences for primer set were used: Human Drp1: (F) 5’-CGGAATCAAGAAGCGACCT-3’ and (R) 5’-ACAGCCATTCCCATCCACT-3, Human Fis1: (F) 5’-GGAGGAGAGGACGAGGAGA-3’ and (R) 5’-CTTGCTGTCCTCGGCTTCT-3’, Human Mfn1: (F) 5’-TGGATGCTTATGCGGAAGG-3’ and (R) 5’-AGGACCTGCTGCTGTCATCT-3’, Mfn2: (F) 5’-TTGTGTTTGGATGACCGCAG-3’ and (R) 5’-TGAGGTAGTCGTAGCCGAAG-3’

Immunoblot Assay

Protein lysates obtained from cultured human cortical neurons were separated on 4-20% gradient SDS–PAGE and subsequently transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in PBS containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 and 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin to prevent nonspecific binding. Following blocking, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies targeting SIRT1 (rabbit polyclonal, #2310, Cell Signaling Technology), PGC-1α (rabbit polyclonal, NBP1-04676, Novus Biologicals), MAP2 (rabbit polyclonal, #4542, Cell Signaling Technology), VGLUT1 (mouse monoclonal, N28/9, Abcam), Synapsin I (rabbit monoclonal, ab254349, Abcam), TBR1 (rabbit monoclonal, ab183032, Abcam), SATB1 (rabbit monoclonal, ab92446, Abcam), and β-actin (HRP-conjugated rabbit monoclonal, 13E5, Cell Signaling Technology). After washing tree times, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies against rabbit or mouse IgG (Amersham Biosciences). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Thermo Scientific) and captured on X-ray film (Amersham Bioscience Corp.). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software, and densitometric values represent the mean of minimum three independent experiments.

Statistics

Quantitative data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was assessed either via an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test or nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test for two-group comparison or an ANOVA test with Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis for comparison of more than three groups.

Results

This study investigated the effects of phosphatidylserine (PS) purity on neuronal function using human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived cortical neurons, examining PS at purities of 50%, 70%, and 80%. Additionally, the role of PS in mitigating Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-like pathology was assessed using an amyloid-beta 1-42 (Aβ42) peptide model. The findings demonstrate how PS purity influences critical protein expression, mitochondrial quality control, and neuroprotection.

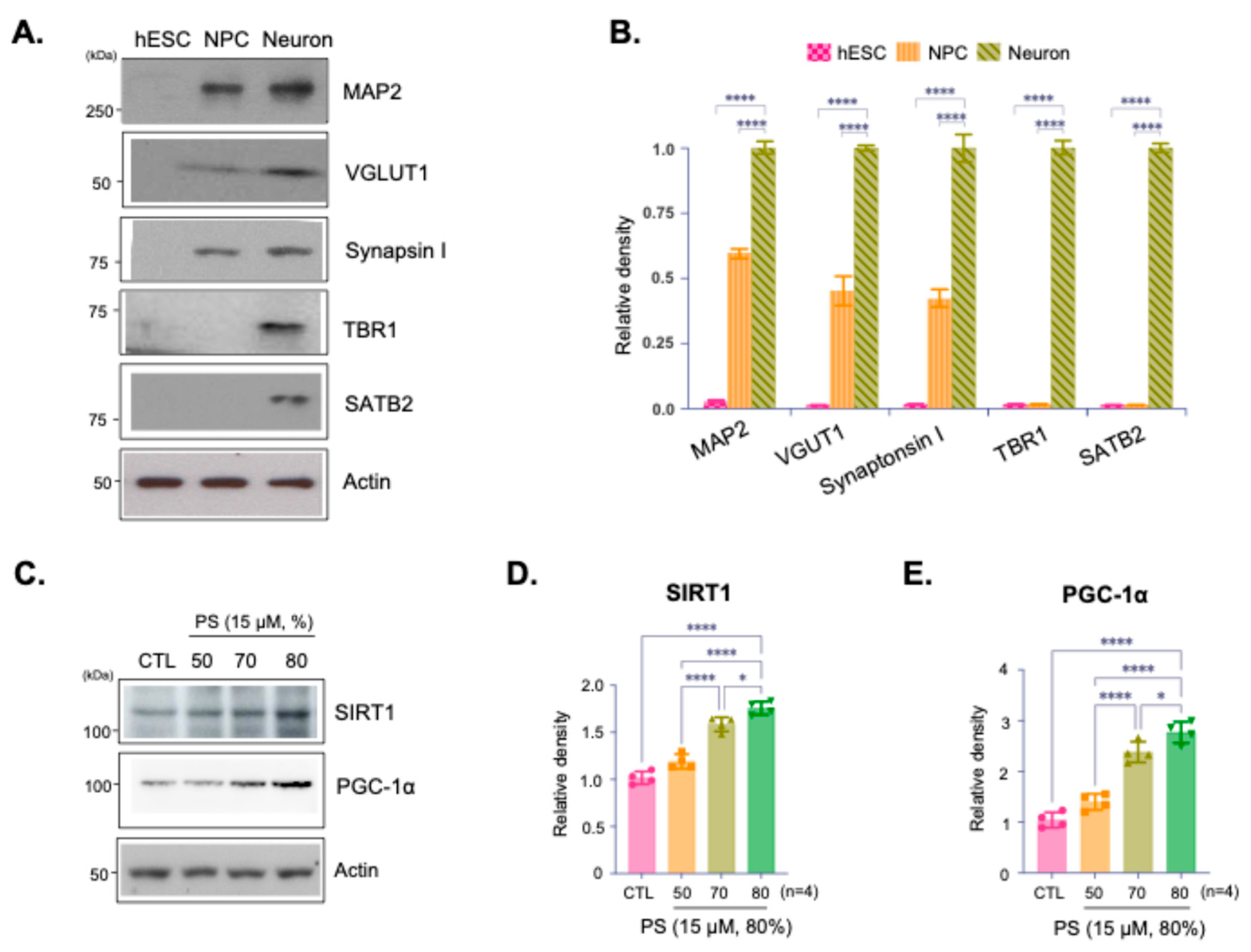

Effects of PS Purity on SIRT1 and PGC-1α Expression in hESC-Derived Cortical Neurons

Immunoblot analysis confirmed the developmental stage specific characters and neuronal identity of the cultured hESC-derived cortical neurons (

Figure 1A,B). Expressed protein levels of immunoblotting of the synaptic markers VGLUT and Synapsin I indicate that synaptic integrity was preserved (

Figure 1A,B). Furthermore, expression of MAP2, TBR1, and SATB2 confirmed the cortical identity and differentiation of these neurons, indicating they are functionally active and suitable for further analysis (

Figure 1A,B). Immunoblot analysis assessed the expression of SIRT1 and PGC-1α, proteins involved in cellular aging and metabolic regulation, in neurons treated with PS at 50%, 70%, and 80% purity (

Figure 1C). The results indicate a purity-dependent increase in SIRT1 and PGC-1α expression with higher PS purities, suggesting that increased PS purity promotes the expression of proteins. Quantification of SIRT1 and PGC-1α expression levels showed a statistically significant increase in SIRT1 and PGC-1α with higher PS purity levels, particularly at 80% (

Figure 1D,E).

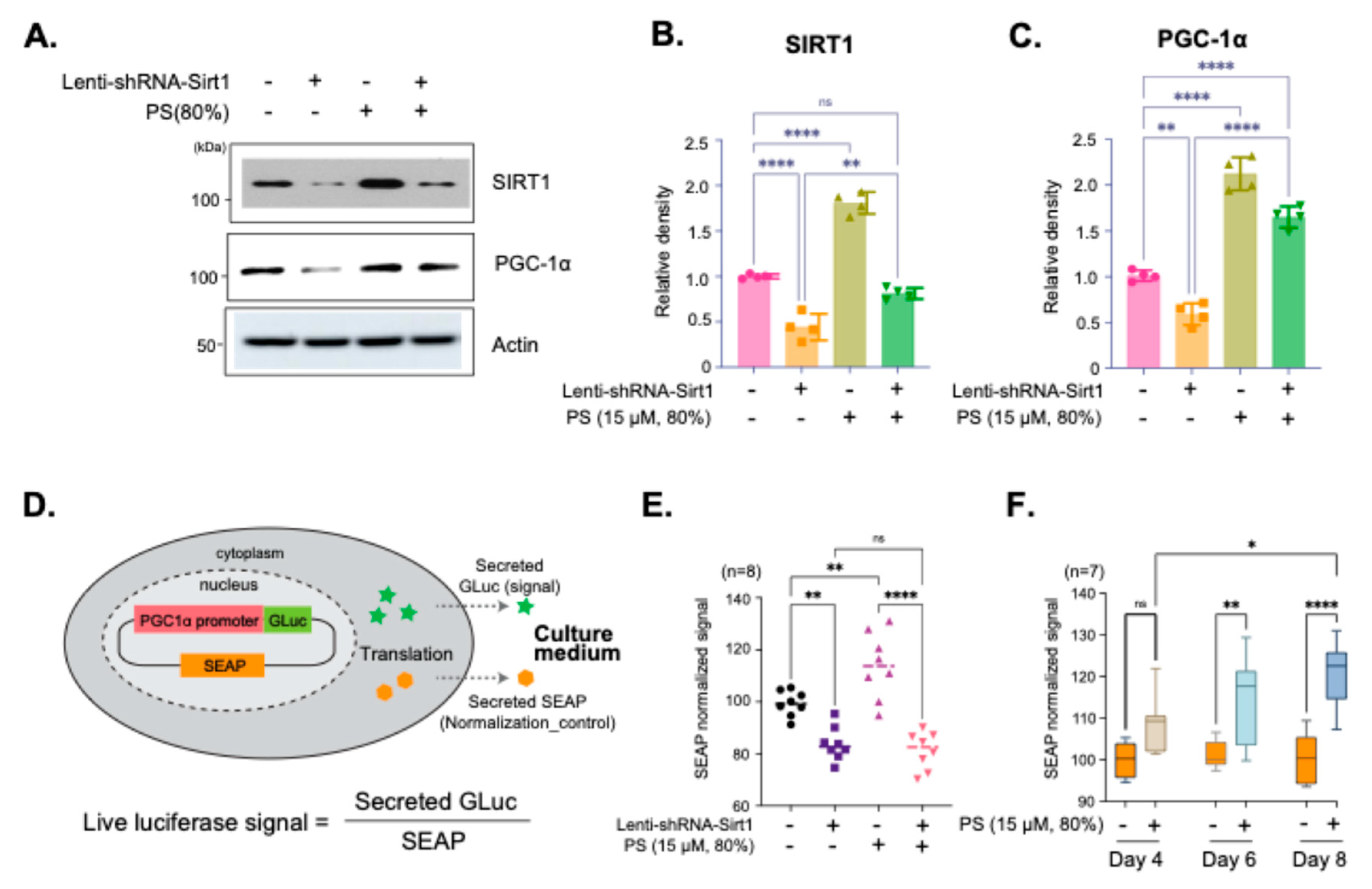

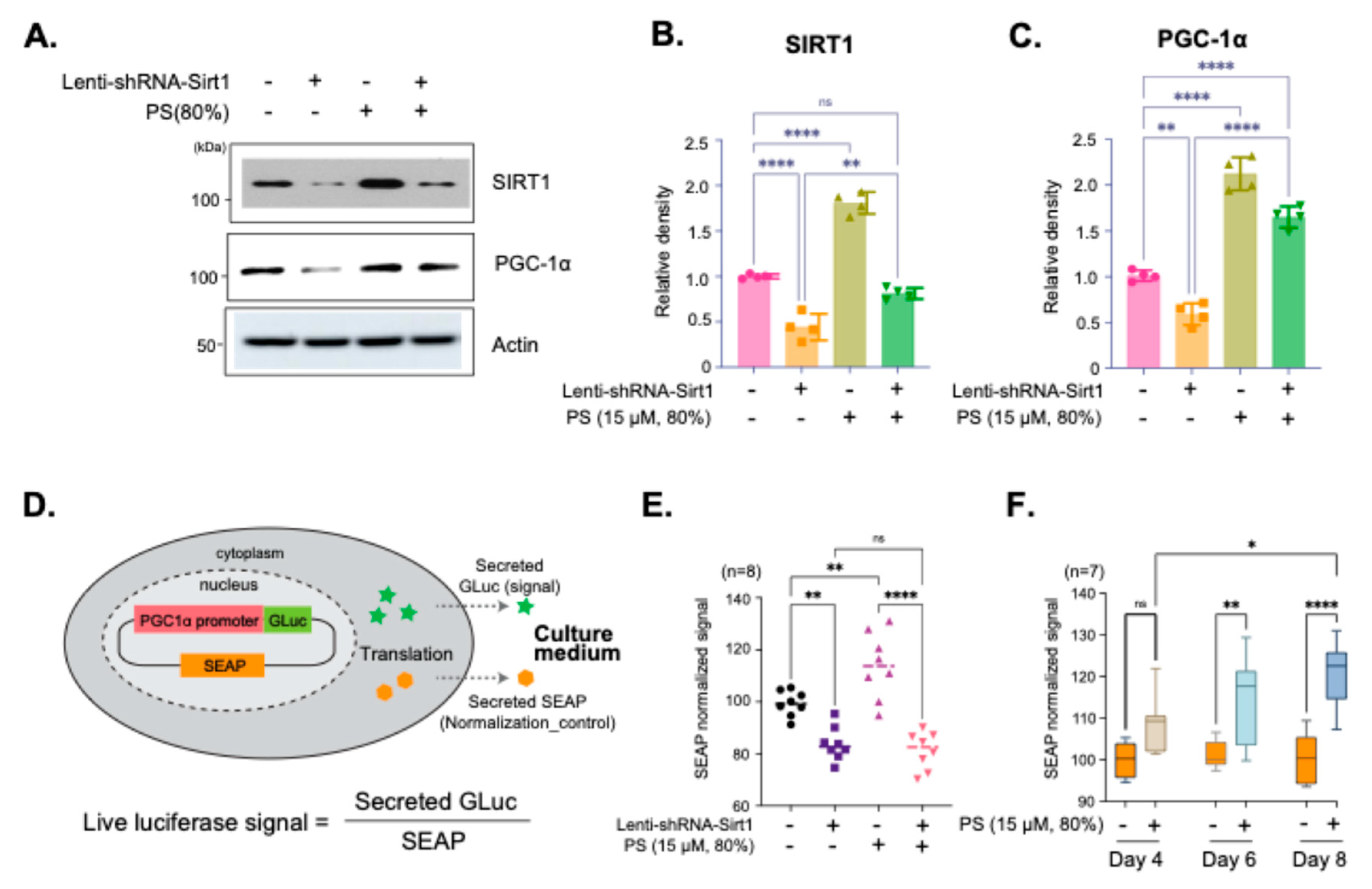

SIRT1-Dependent Regulation of PGC-1α Expression by PS in hESC-Derived Cortical Neurons

Immunoblot analysis showed the effects of SIRT1 knockdown on PGC-1α expression in neurons treated with 80% PS. Lenti-shRNA-Sirt1 was used to reduce SIRT1 expression, followed by treatment with 80% purity PS (

Figure 2A). The results showed a decrease in PGC-1α expression with SIRT1 knockdown, which is partially restored with PS treatment, indicating that PS mediates PGC-1α expression through SIRT1 (

Figure 2A–C). Quantification of SIRT1 and PGC-1α protein demonstrated that SIRT1 expression is significantly reduced with Lenti-shRNA-Sirt1, and PS treatment could restore SIRT1 levels to some extent (

Figure 2B). Additionally, PGC-1α expression was shown to be SIRT1-dependent, as indicated by the significant decrease in its levels upon SIRT1 knockdown, partially recovered with PS treatment (

Figure 2C). The Secrete-Pair™ Dual Luminescence Assay was employed to measure live

PGC-1α promoter activity without sacrificing cells and to observe changes in activity over time (

Figure 2D). The

PGC-1α promoter (1.3 kb from TSS) drives the expression of Gaussia Luciferase (GLuc) as a signal reporter, with Secreted Alkaline Phosphatase (SEAP) acting as a normalization control for assay accuracy as illustrated in

Figure 2D. The assay results showed the normalized GLuc signal for neurons treated with Lenti-shRNA-Sirt1 and 80% PS, indicating that

PGC-1α promoter activity is SIRT1-dependent and upregulated with PS treatment (

Figure 2E). Additionally, the effects of treatment with PS (80%) on Day 4, 6, and 8 were evaluated to observe changes in PGC-1α promoter activity. The time-dependent increase in

PGC-1α promoter activity demonstrated sustained activation over time (

Figure 2F).

Figure 1.

Effects of Phosphatidylserine (PS) purity on SIRT1 and PGC-1α expression in hESC-derived cortical neurons. (A) Immunoblot analysis of cultured hESC-derived cortical neurons assessed the expression of MAP1, VGLUT, Synapsin I, TBR1, and SATB2 confirming that both cortical identity and synaptic integrity were preserved in the neurons. (B) Quantification of relative protein density from Immunoblots normalized to actin. (C) Immunoblot analysis of SIRT1 and PGC-1α protein expression in hESC-derived cortical neurons treated with PS (15 µM) at different purities (50%, 70%, and 80%) and a control (CTL). (D and E) Quantification of relative SIRT1 (D) and PGC-1α (E) protein density from Immunoblots normalized to actin. Data are presented as means ±SEM, with n=4 biological replicates. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 1.

Effects of Phosphatidylserine (PS) purity on SIRT1 and PGC-1α expression in hESC-derived cortical neurons. (A) Immunoblot analysis of cultured hESC-derived cortical neurons assessed the expression of MAP1, VGLUT, Synapsin I, TBR1, and SATB2 confirming that both cortical identity and synaptic integrity were preserved in the neurons. (B) Quantification of relative protein density from Immunoblots normalized to actin. (C) Immunoblot analysis of SIRT1 and PGC-1α protein expression in hESC-derived cortical neurons treated with PS (15 µM) at different purities (50%, 70%, and 80%) and a control (CTL). (D and E) Quantification of relative SIRT1 (D) and PGC-1α (E) protein density from Immunoblots normalized to actin. Data are presented as means ±SEM, with n=4 biological replicates. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

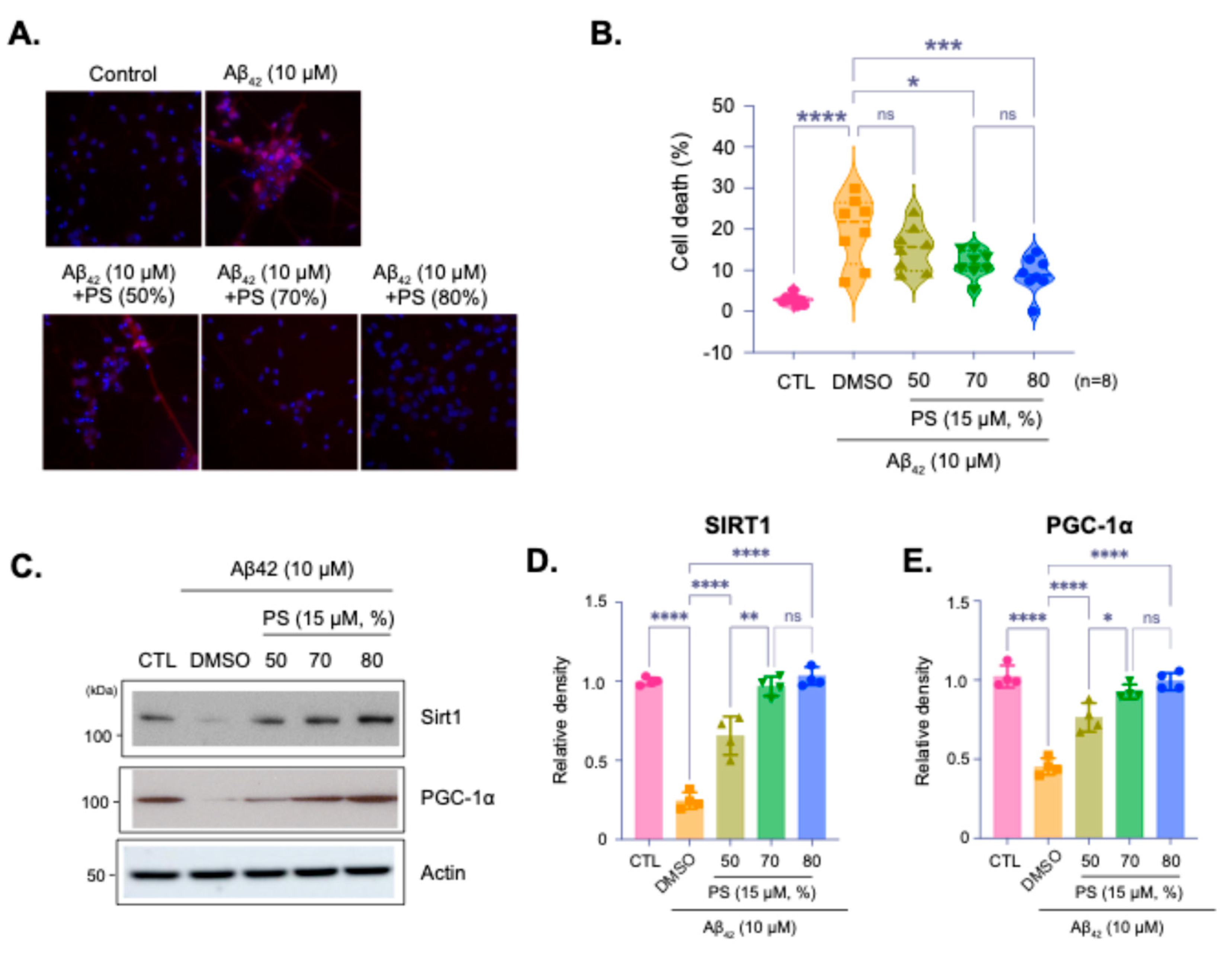

Protective Effects of PS Purity on SIRT1 and PGC-1α Expression in an AD Model

Representative images and quantification of cell viability in hESC-derived cortical neurons treated with Aβ

42 peptide (10 µM) to simulate AD-like pathology, with or without PS at varying purities (

Figure 3A). Images shows propidium iodide (PI) staining for cell death, with PI-positive cells indicating cytotoxicity (

Figure 3A). Quantification showed that PS treatment significantly reduces Aβ

42-induced cell death, with 80% purity providing the most effective neuroprotection (

Figure 3B). Immunoblot analysis of SIRT1 and PGC-1α expression in neurons treated with Aβ

42 and PS at different purities (

Figure 3C–E). Aβ

42 treatment reduced the expression of these proteins however, PS treatment, particularly at both 70% and 80% purities, mitigated this reduction, suggesting that PS helps preserve critical proteins associated with cellular health. Quantitative analysis of SIRT1 and PGC-1α levels normalized to actin showed that treatment of Aβ

42 significantly reduces SIRT1 and PGC-1α expression, while PS treatment, especially at 70% and 80%, restores their levels, demonstrating its protective effect against AD-like pathology (

Figure 3D,E).

Figure 2.

SIRT1-dependent regulation of PGC-1α expression by PS (15 µM, 80%) in hESC-derived cortical neurons. (A) Immunoblot images of SIRT1 and PGC-1α protein expression in hESC-derived cortical neurons. Cells were treated with Lenti-shRNA-Sirt1 to knock down SIRT1 expression and subsequently treated with 80% purity PS (15 µM). (B and C) Quantification of relative SIRT1 (B) and PGC-1α (C) protein density, normalized to actin. (D) Schematic illustration of the Secrete-Pair™ Dual Luminescence Assay used to measure PGC-1α promoter activity. The PGC-1α promoter drives expression of Gaussia Luciferase (GLuc) as a signal reporter, while Secreted Alkaline Phosphatase (SEAP) is used as a normalization control. (E) Quantification of PGC-1α promoter activity in hESC-derived cortical neurons after treatment with Lenti-shRNA-Sirt1 and 80% purity PS (15 µM). The GLuc signal, normalized by SEAP, shows Sirt1-dependent PGC-1α promoter activity. (F) Time-dependent measurement of PGC-1α promoter activity following PS treatment (15 µM, 80%) at Day 4, 6 and 8. Data are presented as means ±SEM, with sample sizes as indicated in each panel. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 2.

SIRT1-dependent regulation of PGC-1α expression by PS (15 µM, 80%) in hESC-derived cortical neurons. (A) Immunoblot images of SIRT1 and PGC-1α protein expression in hESC-derived cortical neurons. Cells were treated with Lenti-shRNA-Sirt1 to knock down SIRT1 expression and subsequently treated with 80% purity PS (15 µM). (B and C) Quantification of relative SIRT1 (B) and PGC-1α (C) protein density, normalized to actin. (D) Schematic illustration of the Secrete-Pair™ Dual Luminescence Assay used to measure PGC-1α promoter activity. The PGC-1α promoter drives expression of Gaussia Luciferase (GLuc) as a signal reporter, while Secreted Alkaline Phosphatase (SEAP) is used as a normalization control. (E) Quantification of PGC-1α promoter activity in hESC-derived cortical neurons after treatment with Lenti-shRNA-Sirt1 and 80% purity PS (15 µM). The GLuc signal, normalized by SEAP, shows Sirt1-dependent PGC-1α promoter activity. (F) Time-dependent measurement of PGC-1α promoter activity following PS treatment (15 µM, 80%) at Day 4, 6 and 8. Data are presented as means ±SEM, with sample sizes as indicated in each panel. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

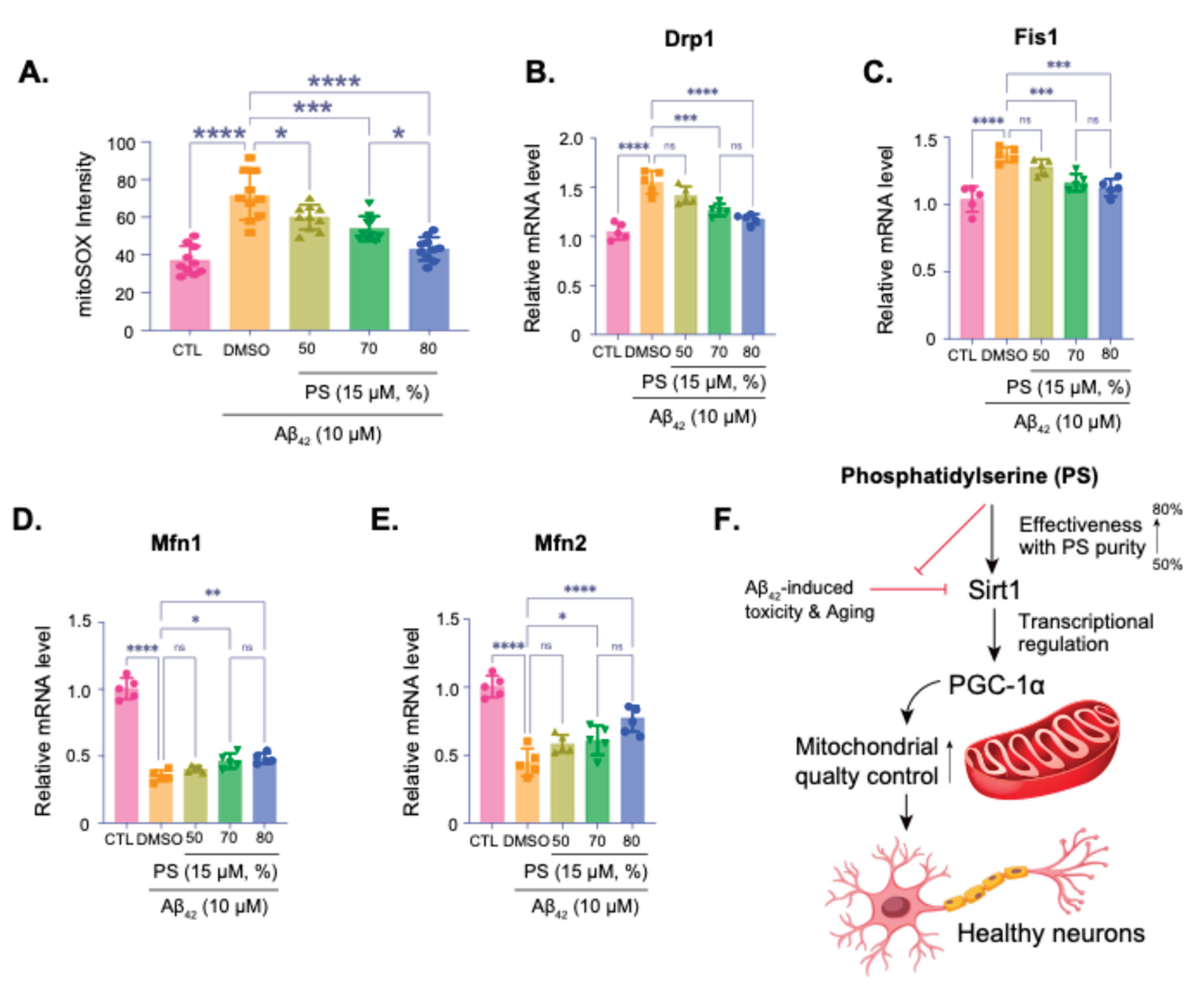

PS-Induced Mitochondrial Quality Control via SIRT1 and PGC-1α in an AD Model

Measurement of mitochondrial superoxide levels using mitoSOX staining, showing oxidative stress in neurons treated with Aβ

42 and various purities of PS (

Figure 4A). Higher PS purity significantly reduced oxidative stress, as indicated by the decrease in mitoSOX intensity, with 80% purity showing the most effective reduction (

Figure 4A). qPCR analysis of the mitochondrial fission-related genes Drp1 (

Figure 4B) and Fis1 (

Figure 4C), both of which are upregulated under Aβ

42-treatment, and mitochondrial fusion-related genes Mfn1 (

Figure 4D) and Mfn2 (

Figure 4E), both of which are downregulated under Aβ

42-treatment suggesting mitochondrial dysfunction, were quantitatively investigated with various purities of PS. PS treatment, particularly at 70% and 80% purities, restores their levels, supporting mitochondrial fission and fusion, and its integrity stress (

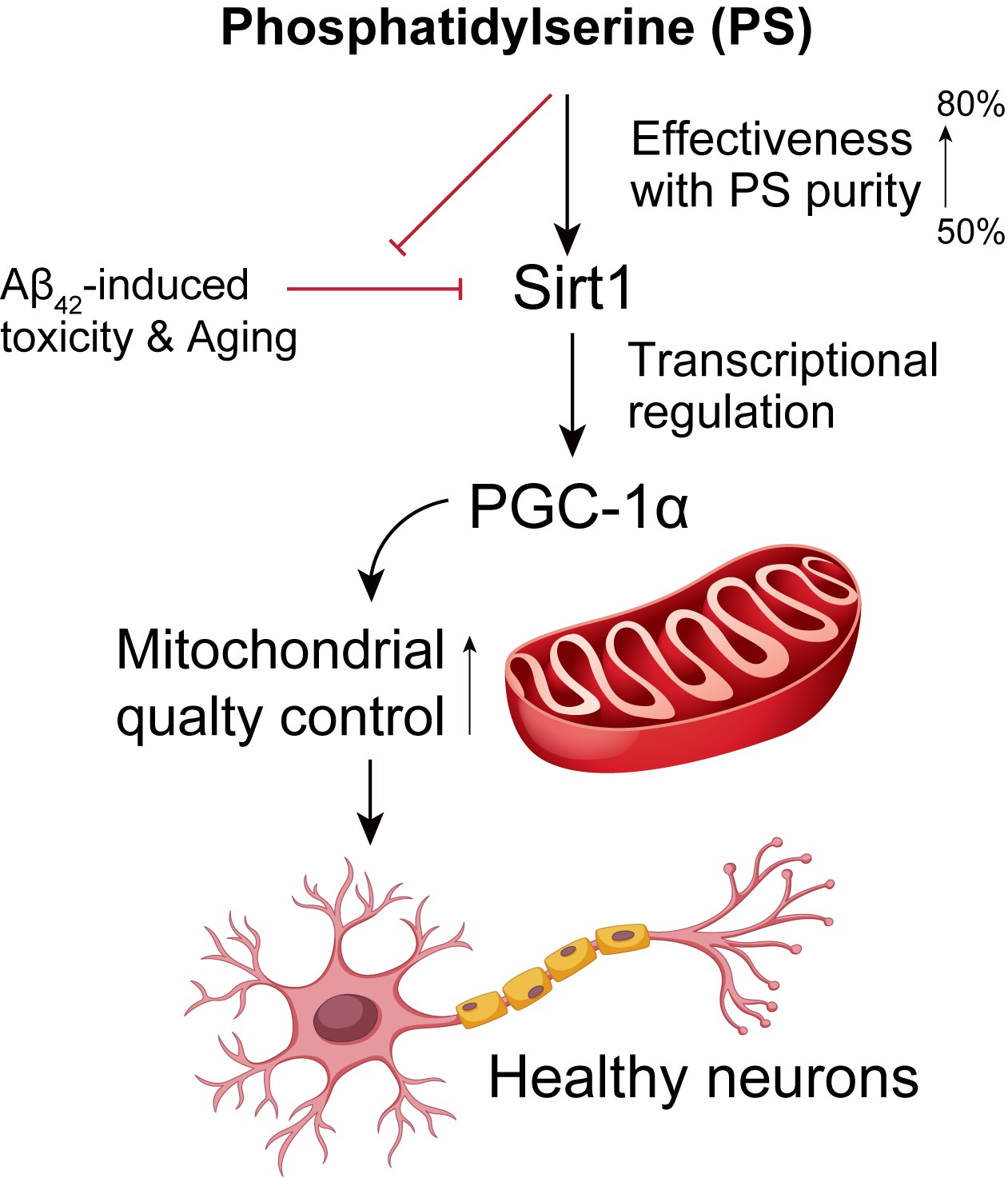

Figure 4B–E). Summary diagram of the proposed mechanism, indicating that PS at higher purities (up to 80%) mitigates Aβ

42-induced toxicity and oxidative stress by enhancing SIRT1 expression, which regulates PGC-1α (

Figure 4F). This pathway promotes mitochondrial quality control and sustains neuronal health.

Figure 3.

Protective effects of PS purity on SIRT1 and PGC-1α expression in an Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Model. (A) Representative images of hESC-derived cortical neurons treated with Aβ42 peptide (10 µM) to induce AD-like conditions, followed by treatment with PS at varying purities (50%, 70%, and 80%). Cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) to assess cell viability, with PI-positive cells indicating cell death. (B) Quantification of cell death percentage based on PI staining. (C) Immunoblot analysis of SIRT1 and PGC-1α protein expression under Aβ42 treatment, with and without PS at different purities. (D and E) Quantification of relative SIRT1 (D) and PGC-1α (E) protein density from immunoblot, normalized to actin. Data are presented as means ±SEM, with sample sizes as indicated in each panel. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: ns - non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Protective effects of PS purity on SIRT1 and PGC-1α expression in an Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) Model. (A) Representative images of hESC-derived cortical neurons treated with Aβ42 peptide (10 µM) to induce AD-like conditions, followed by treatment with PS at varying purities (50%, 70%, and 80%). Cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) to assess cell viability, with PI-positive cells indicating cell death. (B) Quantification of cell death percentage based on PI staining. (C) Immunoblot analysis of SIRT1 and PGC-1α protein expression under Aβ42 treatment, with and without PS at different purities. (D and E) Quantification of relative SIRT1 (D) and PGC-1α (E) protein density from immunoblot, normalized to actin. Data are presented as means ±SEM, with sample sizes as indicated in each panel. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: ns - non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Discussion

This study highlights the potential of phosphatidylserine (PS) in preserving neuronal health through purity-dependent modulation of key regulatory proteins, specifically SIRT1 and PGC-1α, using human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived cortical neurons. The Rosette Neural Aggregate (RONA) method is known as efficiently mimicking the human cortex by differentiating hESCs into functionally mature neuron complex using timed retinoic acid application (

Figure 1A,B) [

3,

29,

30]. This culture allows to effectively replicate human cortical architecture and reliable testing of chemical efficacy and neurotoxicity in a controlled environment [

3,

29,

30,

31]. By integrating this system, our data underscore the importance of PS purity in neuronal function, showing that higher PS purity enhances neuroprotective pathways, attenuates AD-like pathology, and supports mitochondrial quality control, providing insights into how PS purity could influence neurodegenerative disease progression. Consistent with prior studies demonstrating that SIRT1 plays a critical role in cellular aging, metabolic regulation, and neuroprotection, we observed a significant, purity-dependent increase in SIRT1 expression [

32,

33,

34]. Specifically, 80% PS purity resulted in the highest levels of SIRT1 and PGC-1α, a transcriptional coactivator regulated by SIRT1 that potentially enhances mitochondrial biogenesis and function (

Figure 1C–E). This finding aligns with previous research suggesting that SIRT1-mediated upregulation of PGC-1α can contribute to neuroprotection by promoting mitochondrial health and reducing oxidative stress [

32,

34,

35]. This effect of PS purity suggests that PS enhances the SIRT1-PGC-1α axis, potentially mitigating age-related declines in these proteins in cortical neurons.

Figure 4.

Phosphatidylserine-Induced mitochondrial quality control via SIRT1 and PGC-1α in an AD model. (A) MitoSOX assay quantifying mitochondrial oxidative stress by measuring superoxide levels in hESC-derived cortical neurons exposed to Aβ42 (10 µM) with varying levels of PS purity (50%, 70%, 80%). (B-E) qPCR analysis of Drp1 (B) and Fis1 (C) mRNA levels, genes associated with mitochondrial fission, Mfn1 (D) and Mfn2 (E) mRNA levels, genes associated with mitochondrial fusion. (F) Summary diagram illustrating the proposed mechanism: PS at higher purities mitigates Aβ42-induced toxicity and oxidative stress by enhancing SIRT1 expression, which in turn regulates PGC-1α. This pathway promotes mitochondrial quality control, supporting healthy neuronal function. Data are presented as means ±SEM, with sample sizes as indicated in each panel. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: ns – non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

Phosphatidylserine-Induced mitochondrial quality control via SIRT1 and PGC-1α in an AD model. (A) MitoSOX assay quantifying mitochondrial oxidative stress by measuring superoxide levels in hESC-derived cortical neurons exposed to Aβ42 (10 µM) with varying levels of PS purity (50%, 70%, 80%). (B-E) qPCR analysis of Drp1 (B) and Fis1 (C) mRNA levels, genes associated with mitochondrial fission, Mfn1 (D) and Mfn2 (E) mRNA levels, genes associated with mitochondrial fusion. (F) Summary diagram illustrating the proposed mechanism: PS at higher purities mitigates Aβ42-induced toxicity and oxidative stress by enhancing SIRT1 expression, which in turn regulates PGC-1α. This pathway promotes mitochondrial quality control, supporting healthy neuronal function. Data are presented as means ±SEM, with sample sizes as indicated in each panel. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: ns – non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

To further investigate the regulatory relationship between SIRT1 and PGC-1α, we conducted experiments using SIRT1 knockdown, revealing that PS-induced Pgc-1α expression is indeed SIRT1-dependent (

Figure 2A–C). This SIRT1-mediated modulation of Pgc-1α is critical, as PGC-1α is known for its role in mitochondrial quality control, which is essential in high-energy-demanding cells such as neurons [

33,

34,

35]. Our Secrete-Pair™ Dual Luminescence Assay, used to measure

PGC-1α activity, demonstrated that PS treatment activates the

PGC-1α promoter in a SIRT1-dependent manner, supporting previous findings that SIRT1 can regulate PGC-1α transcriptionally (

Figure 2D–F) [

33,

34,

35]. This observation provides evidence that PS exerts its effects on mitochondrial health through a SIRT1-PGC-1α regulatory axis, emphasizing the relevance of PS purity in therapeutic strategies or supplements targeting mitochondrial dysfunction [

32,

34,

36].

The neuroprotective effects of PS were further substantiated in an Aβ

42-induced AD model, where we observed that PS, particularly at 70% and 80% purities, mitigated Aβ

42-induced cytotoxicity, as demonstrated by reduced cell death (

Figure 3A-B). These findings corroborate prior studies suggesting that SIRT1 and PGC-1α play protective roles against AD pathology [

33,

35,

37]. Notably, treatment with higher than 70% PS purity counteracted the Aβ

42-induced downregulation of SIRT1 and PGC-1α, indicating that PS not only preserves neuronal viability but supports the expression of essential proteins in the face of neurotoxic insults (

Figure 3C–E). This suggests that PS supplementation, particularly at high purities, may serve as a viable approach to mitigate early AD pathology by modulating critical proteins involved in cellular health [

33,

36,

38].

Given the observed effects on mitochondrial regulators, we explored the impact of PS on mitochondrial quality control in the Aβ

42-treated neurons. MitoSOX staining revealed a significant reduction in mitochondrial oxidative stress with increasing PS purity, with the highest purity (80%) showing the most pronounced effect (

Figure 4A). Additionally, our qPCR data indicated that PS treatment modulated the expression of mitochondrial fission (Drp1 and Fis1) and fusion (Mfn1 and Mfn2) genes, which are often dysregulated in neurodegenerative conditions, including AD (

Figure 4B–E) [

34,

39,

40]. Previous studies suggest that mitochondrial dynamics are critical for maintaining mitochondrial health and neuronal survival, and the observed restoration of fission/fusion gene expression with high-purity PS points to its role in promoting mitochondrial stability and function [

33,

34,

39]. Our findings thus extend the current understanding of PS’s neuroprotective role in the human cortical neuron model, proposing that PS purity is a key determinant in modulating mitochondrial homeostasis in AD-like conditions (

Figure 4F).

Author Contributions

S.M.J., S.C., Y.S.L., H.J., and S.U.K. designed the study and wrote the paper. H.J. and S.U.K. performed hESC-culture, S.M.J., S.C., E.J.K., T.D.K., and J.S. performed immunoblot and qPCR with quantification on non-treated hESC-derived neuron culture. S.M.J., S.C., J.Y.L., and E.J.K performed immunoblot and qPCR with quantification on Aβ42-induced AD model. S.C. and S.U.K. performed luciferase assay with quantification. Y.S.L., H.J. and S.U.K. collected data and performed statistic review. H.J. and S.U.K. designed visualization of summary.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI22C2064).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Park, S.; Rim, C. H.; Yoon, W. S. Where is clinical research for radiotherapy going? Cross-sectional comparison of past and contemporary phase III clinical trials. Radiat Oncol 2020, 15 (1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-020-01489-4 From NLM Medline.

- Hall, A. R.; Angst, D. C.; Schiessl, K. T.; Ackermann, M. Costs of antibiotic resistance - separating trait effects and selective effects. Evol Appl 2015, 8 (3), 261-272. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12187 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE.

- Yang, S. H.; Van, H. T.; Le, T. N.; Khadka, D. B.; Cho, S. H.; Lee, K. T.; Chung, H. J.; Lee, S. K.; Ahn, C. H.; Lee, Y. B.; et al. Synthesis, in vitro and in vivo evaluation of 3-arylisoquinolinamines as potent antitumor agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2010, 20 (17), 5277-5281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.06.132 From NLM Medline.

- Dadachova, E. Future Vistas in Alpha Therapy of Infectious Diseases. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci 2019, 50 (4 Suppl 1), S49-S52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmir.2019.06.052 From NLM Medline.

- Arora, A.; Scholar, E. M. Role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005, 315 (3), 971-979. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.105.084145 From NLM Medline.

- Favre-Bulle, I. A.; Taylor, M. A.; Marquez-Legorreta, E.; Vanwalleghem, G.; Poulsen, R. E.; Rubinsztein-Dunlop, H.; Scott, E. K. Sound generation in zebrafish with Bio-Opto-Acoustics. Nat Commun 2020, 11 (1), 6120. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19982-5 From NLM Medline.

- Heinemeier, K. M.; Schjerling, P.; Heinemeier, J.; Moller, M. B.; Krogsgaard, M. R.; Grum-Schwensen, T.; Petersen, M. M.; Kjaer, M. Radiocarbon dating reveals minimal collagen turnover in both healthy and osteoarthritic human cartilage. Sci Transl Med 2016, 8 (346), 346ra390. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aad8335 From NLM Medline.

- Karodeh, Y. R.; Wingate, L. T.; Drame, I.; Talbert, P. Y.; Dike, A.; Sin, S. Predictors of Academic Success in a Nontraditional Doctor of Pharmacy Degree Program at a Historically Black College and University. Am J Pharm Educ 2022, 86 (10), ajpe8600. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe8600 From NLM Medline.

- Hashimoto, Y.; Zhang, S.; Blissard, G. W. Ao38, a new cell line from eggs of the black witch moth, Ascalapha odorata (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), is permissive for AcMNPV infection and produces high levels of recombinant proteins. BMC Biotechnol 2010, 10, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6750-10-50 From NLM Medline.

- Modi, S.; Lehmann, R.; Maxwell, A.; Solomon, K.; Cionni, R.; Thompson, V.; Horn, J.; Caplan, M.; Fisher, B.; Hu, J. G.; et al. Visual and Patient-Reported Outcomes of a Diffractive Trifocal Intraocular Lens Compared with Those of a Monofocal Intraocular Lens. Ophthalmology 2021, 128 (2), 197-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.07.015 From NLM Medline.

- Manor, I.; Magen, A.; Keidar, D.; Rosen, S.; Tasker, H.; Cohen, T.; Richter, Y.; Zaaroor-Regev, D.; Manor, Y.; Weizman, A. The effect of phosphatidylserine containing Omega3 fatty-acids on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial, followed by an open-label extension. Eur Psychiatry 2012, 27 (5), 335-342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.05.004 From NLM Medline.

- Sugarbaker, P. H.; Chang, D.; Jelinek, J. S. Concerning CT features predict outcome of treatment in patients with malignant peritoneal mesothelioma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2021, 47 (9), 2212-2219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2021.04.012 From NLM Medline.

- Ferraro, S.; Klugah-Brown, B.; Tench, C. R.; Yao, S.; Nigri, A.; Demichelis, G.; Pinardi, C.; Bruzzone, M. G.; Becker, B. Dysregulated anterior insula reactivity as robust functional biomarker for chronic pain-Meta-analytic evidence from neuroimaging studies. Hum Brain Mapp 2022, 43 (3), 998-1010. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25702 From NLM Medline.

- Zheng, J.; Wu, Y.; Tong, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, H. Dual-Carbon confinement strategy of antimony anode material enabling advanced potassium ion storage. J Colloid Interface Sci 2022, 622, 738-747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2022.04.154 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE.

- Busnadiego, I.; Fernbach, S.; Pohl, M. O.; Karakus, U.; Huber, M.; Trkola, A.; Stertz, S.; Hale, B. G. Antiviral Activity of Type I, II, and III Interferons Counterbalances ACE2 Inducibility and Restricts SARS-CoV-2. mBio 2020, 11 (5). https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01928-20 From NLM Medline.

- McConnell, J. D.; Roehrborn, C. G.; Bautista, O. M.; Andriole, G. L., Jr.; Dixon, C. M.; Kusek, J. W.; Lepor, H.; McVary, K. T.; Nyberg, L. M., Jr.; Clarke, H. S.; et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med 2003, 349 (25), 2387-2398. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa030656 From NLM Medline.

- Hayes, G. D.; Frand, A. R.; Ruvkun, G. The mir-84 and let-7 paralogous microRNA genes of Caenorhabditis elegans direct the cessation of molting via the conserved nuclear hormone receptors NHR-23 and NHR-25. Development 2006, 133 (23), 4631-4641. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.02655 From NLM Medline.

- Min, J. L.; Hemani, G.; Hannon, E.; Dekkers, K. F.; Castillo-Fernandez, J.; Luijk, R.; Carnero-Montoro, E.; Lawson, D. J.; Burrows, K.; Suderman, M.; et al. Genomic and phenotypic insights from an atlas of genetic effects on DNA methylation. Nat Genet 2021, 53 (9), 1311-1321. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00923-x From NLM Medline.

- Merech, F.; Hauk, V.; Paparini, D.; Fernandez, L.; Naguila, Z.; Ramhorst, R.; Waschek, J.; Perez Leiros, C.; Vota, D. Growth impairment, increased placental glucose uptake and altered transplacental transport in VIP deficient pregnancies: Maternal vs. placental contributions. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2021, 1867 (10), 166207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2021.166207 From NLM Medline.

- Tang, J.; Qu, L. K.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Michaelson, J. S.; Degenhardt, Y. Y.; El-Deiry, W. S.; Yang, X. Critical role for Daxx in regulating Mdm2. Nat Cell Biol 2006, 8 (8), 855-862. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb1442 From NLM Medline.

- Li, Y.; Cao, H.; Allen, C. M.; Wang, X.; Erdelez, S.; Shyu, C. R. Computational modeling of human reasoning processes for interpretable visual knowledge: a case study with radiographers. Sci Rep 2020, 10 (1), 21620. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77550-9 From NLM Medline.

- Wilson, E. O.; Spaulding, T. J. Effects of noise and speech intelligibility on listener comprehension and processing time of Korean-accented English. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2010, 53 (6), 1543-1554. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0100) From NLM Medline.

- Oderich, G. S.; Tallarita, T.; Gloviczki, P.; Duncan, A. A.; Kalra, M.; Misra, S.; Cha, S.; Bower, T. C. Mesenteric artery complications during angioplasty and stent placement for atherosclerotic chronic mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg 2012, 55 (4), 1063-1071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2011.10.122 From NLM Medline.

- Schulz, V.; Schmidt-Vogler, C.; Strohmeyer, P.; Weber, S.; Kleemann, D.; Nies, D. H.; Herzberg, M. Behind the shield of Czc: ZntR controls expression of the gene for the zinc-exporting P-type ATPase ZntA in Cupriavidus metallidurans. J Bacteriol 2021, 203 (11). https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00052-21 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE.

- Cutler, J.; Wittmann, M. K.; Abdurahman, A.; Hargitai, L. D.; Drew, D.; Husain, M.; Lockwood, P. L. Ageing is associated with disrupted reinforcement learning whilst learning to help others is preserved. Nat Commun 2021, 12 (1), 4440. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24576-w From NLM Medline.

- Roig, J.; Groen, A.; Caldwell, J.; Avruch, J. Active Nercc1 protein kinase concentrates at centrosomes early in mitosis and is necessary for proper spindle assembly. Mol Biol Cell 2005, 16 (10), 4827-4840. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.e05-04-0315 From NLM Medline.

- Hernychova, L.; Alexandri, E.; Tzakos, A. G.; Zatloukalova, M.; Primikyri, A.; Gerothanassis, I. P.; Uhrik, L.; Sebela, M.; Kopecny, D.; Jedinak, L.; et al. Serum albumin as a primary non-covalent binding protein for nitro-oleic acid. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 203, 116-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.01.050 From NLM Medline.

- Wu, K.; Song, W.; Zhao, L.; Liu, M.; Yan, J.; Andersen, M. O.; Kjems, J.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Y. MicroRNA functionalized microporous titanium oxide surface by lyophilization with enhanced osteogenic activity. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2013, 5 (7), 2733-2744. https://doi.org/10.1021/am400374c From NLM Medline.

- Xu, J. C.; Fan, J.; Wang, X.; Eacker, S. M.; Kam, T. I.; Chen, L.; Yin, X.; Zhu, J.; Chi, Z.; Jiang, H.; et al. Cultured networks of excitatory projection neurons and inhibitory interneurons for studying human cortical neurotoxicity. Sci Transl Med 2016, 8 (333), 333ra348. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aad0623 From NLM Medline.

- Yin, X.; Xu, J. C.; Cho, G. S.; Kwon, C.; Dawson, T. M.; Dawson, V. L. Neurons Derived from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Integrate into Rat Brain Circuits and Maintain Both Excitatory and Inhibitory Synaptic Activities. eNeuro 2019, 6 (4). https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0148-19.2019 From NLM Medline.

- Weick, J. P.; Johnson, M. A.; Skroch, S. P.; Williams, J. C.; Deisseroth, K.; Zhang, S. C. Functional control of transplantable human ESC-derived neurons via optogenetic targeting. Stem Cells 2010, 28 (11), 2008-2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.514 From NLM Medline.

- Chen, J.; Liu, B.; Yao, X.; Yang, X.; Sun, J.; Yi, J.; Xue, F.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Y.; Chen, B.; et al. AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1alpha Signaling Pathway: Molecular Mechanisms and Targeted Strategies From Energy Homeostasis Regulation to Disease Therapy. CNS Neurosci Ther 2025, 31 (11), e70657. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.70657 From NLM Medline.

- D’Alessandro, M. C. B.; Kanaan, S.; Geller, M.; Pratico, D.; Daher, J. P. L. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev 2025, 107, 102713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2025.102713 From NLM Medline.

- McGill Percy, K. C.; Liu, Z.; Qi, X. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: Guiding the path to targeted therapies. Neurotherapeutics 2025, 22 (3), e00525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurot.2025.e00525 From NLM Medline.

- Tang, M. B.; Liu, Y. X.; Hu, Z. W.; Luo, H. Y.; Zhang, S.; Shi, C. H.; Xu, Y. M. Study insights in the role of PGC-1alpha in neurological diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Front Aging Neurosci 2024, 16, 1454735. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2024.1454735 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE.

- Ma, X.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.; Yang, B.; Miao, Z. Phosphatidylserine, inflammation, and central nervous system diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 14, 975176. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.975176 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE.

- Panes, J. D.; Godoy, P. A.; Silva-Grecchi, T.; Celis, M. T.; Ramirez-Molina, O.; Gavilan, J.; Munoz-Montecino, C.; Castro, P. A.; Moraga-Cid, G.; Yevenes, G. E.; et al. Changes in PGC-1alpha/SIRT1 Signaling Impact on Mitochondrial Homeostasis in Amyloid-Beta Peptide Toxicity Model. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 709. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.00709 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE.

- Duan, H.; Xu, N.; Yang, T.; Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhang, M.; et al. Effects of a food supplement containing phosphatidylserine on cognitive function in Chinese older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord 2025, 369, 35-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.09.131 From NLM Medline.

- Joshi, A. U.; Saw, N. L.; Shamloo, M.; Mochly-Rosen, D. Drp1/Fis1 interaction mediates mitochondrial dysfunction, bioenergetic failure and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Oncotarget 2018, 9 (5), 6128-6143. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23640 From NLM PubMed-not-MEDLINE.

- Manczak, M.; Calkins, M. J.; Reddy, P. H. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics and abnormal interaction of amyloid beta with mitochondrial protein Drp1 in neurons from patients with Alzheimer’s disease: implications for neuronal damage. Hum Mol Genet 2011, 20 (13), 2495-2509. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddr139 From NLM Medline.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).