0. Introduction

Nanoscience and technology have advanced rapidly in the past decade. Recently, scientists’ attention has been increasingly focused on the application of nanomaterials in biology, and as a new generation of light-emitting materials, upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) have caught their wide attention [

1,

2,

3]. In the past decade, the development of upconversion nanoluminescent materials has promoted the transformation of fluorescence imaging from micro to macro. Although other common fluorescent materials (including organic dyes, fluorescent proteins, metal complexes or semiconductor quantum dots) have made significant progress in real-time detection and bioimaging as basic biomarkers [

4,

5], they still have some drawbacks. These fluorescent materials often need to be excited by ultraviolet (UV) or visible light, which can induce spontaneous fluorescence of biological tissues, DNA damage and cell death of biological samples, resulting in low signal-to-noise ratio and limited sensitivity [

4,

5,

6]. In addition, the broad spectrum of emission spectra of these fluorescent materials makes them unsuitable for multiple biomarkers and have poor light stability.

In contrast, UCNPs has a lot of good properties. The main difference between UCNPs and other lightemitting imaging materials is that they can emit visible or ultraviolet light when exposed to near-infrared light. Non-radiation does not cause photodamage to biological tissues, and can effectively avoid self-fluorescence of organisms, with high detection sensitivity and high light penetration depth [

7,

8]. In addition, UCNPs also show the advantages of narrow emission bandwidth, high light stability, controllable emission spectrum, long life and low cytotoxicity [

2,

9,

10]. Although there are already numerous reviews on UCNPs, this review aims to offer a practical guidance framework for researchers in the biomedical field, focusing on how to select the most appropriate synthesis methods and surface modification strategies based on specific biological application scenarios (such as deep tissue imaging, in vitro diagnosis, etc.), and analyzing the key challenges and future opportunities faced by this field in transitioning from basic research to clinical translation.

1. Luminescence Mechanism and Composition of Upconversion Nanomaterials

1.1. Composition of Upconversion Nanomaterials

Rare earth (RE) doped upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) can emit light with higher energy than excitation light, and due to this unique ability, rare earth doped upconversion nanoparticles have recently received considerable attention. In general, rare-doped UCNPs consist of three components: a master matrix, a sensitizer and an activator6. The main matrix is one of the most important components of upconversion nanoparticles, because they can provide a suitable crystal field for the luminescence center and fix the doped ions. In the sensitized luminescence process, the sensitizer can be efficiently excited by the energy of the incident light source and transfer this energy to the activator that can emit radiation through radiation-free relaxation, making it transition to a higher energy level and emit upconversion fluorescence. Thus, the activator is the luminescent center of the upconversion nanoparticle, while the sensitizer enhances the up-conversion luminescence efficiency. Generally, dopants, i.e., sensitizers and activators, are added to the main matrix in relatively low concentrations (usually about 20% for sensitizers and <2% for activators).

Inorganic compounds of trivalent rare earth ions are usually ideal as the main matrix for upconversion nanoparticles. However, a principal matrix with low lattice photon energy requires minimizing non-radiative losses and maximizing upconversion emission. Trivalent Yb3+ ions with simple energy level structures are suitable for use as upconversion sensitizers [

11]. A huge majority of rare earth ions with three positive charges have many excited levels and are suitable for use as upconversion activators [

12,

13].

1.2. Luminescence Mechanism of Nanomaterials

Upconversion is a nonlinear optical process, which refers to the process in which a material absorbs two or more low energy (near infrared light) photons and emits high energy (visible or ultraviolet light) photons, so it can be classified as the anti-Stokes mechanism. The upconversion luminescence mechanism can be summarized into three main types: excited state absorption (ESA), energy transfer (ET) and photon avalanche (PA)[

14,

15].

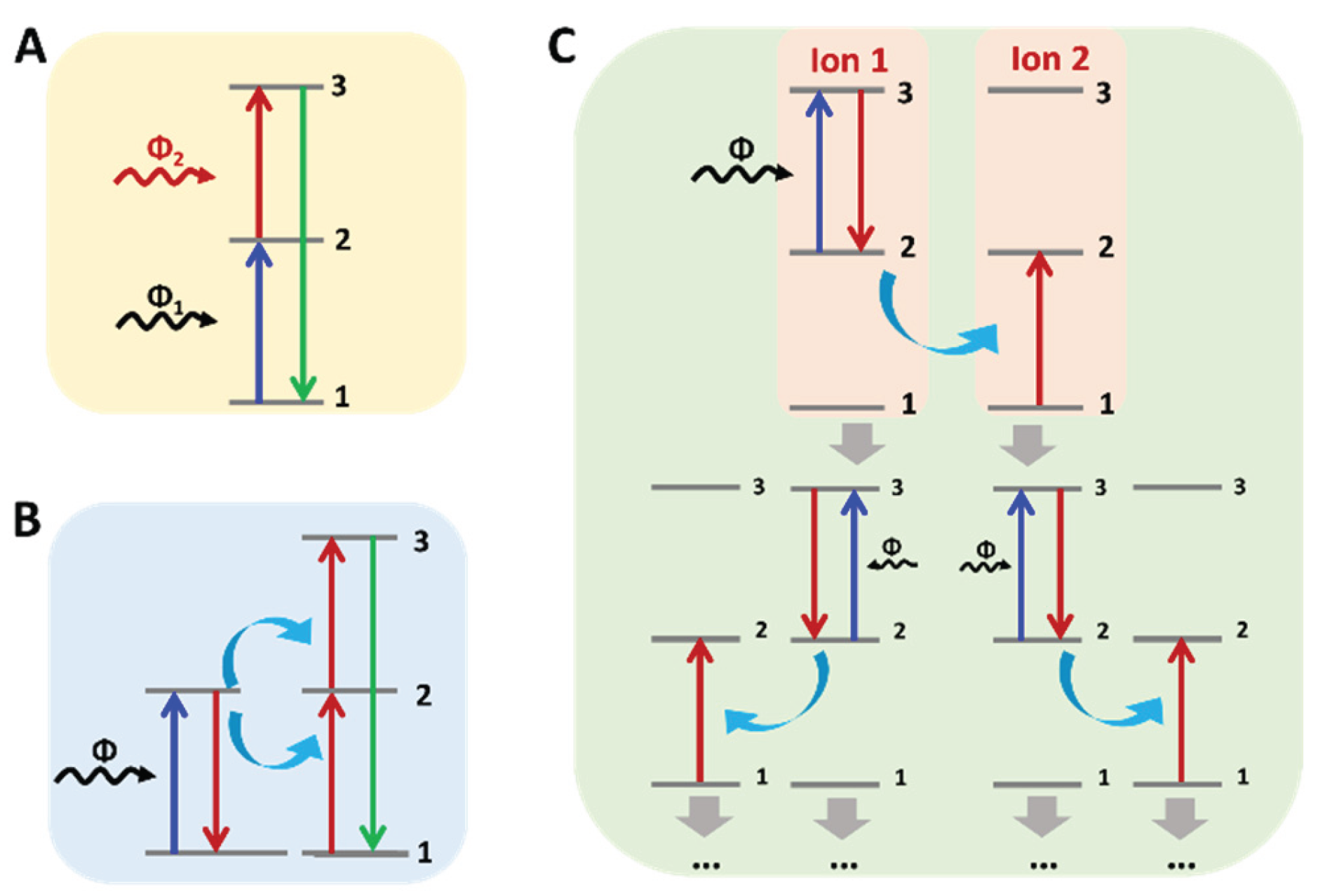

(1) Excited state absorption: Excited state absorption, also known as continuous two-photon absorption, is one of the most widely recognized models of upconversion luminescence [

16]. Excited state absorption refers to the process of continuous absorption of multiple photons by an ion from a low energy ground state level to a high energy excited state level, and upconversion luminescence is generated when it returns to the ground state. Excited state absorption generally involves the preparation of two photons of continuous. As shown in

Figure 1A under a suitable excitation light source, the first photon causes ions to enter the metastable intermediate excited state (state 2) from the ground state (state 1), which is called ground state absorption (GSA). If the energy difference between the intermediate excited state (state 2) and the higher excited state (state 3) matches the energy of the excitation light source, the ion will continue to absorb the second photon from state 2 to the higher excited state (state 3), and when the ion returns from the higher excited state (state 3) to the ground state (state 1), the upconversion luminescence will occur.

(2) Energy transfer: Energy transfer involves two or more ions. Unlike the excited state absorption process, energy transfer process 1 involves the exciting ion (sensitizer or donor) absorbing the energy provided by the light source and transferring the energy to another adjacent ion (activator or acceptor). Different types of ET mechanisms [

17] that have been well known include continuous energy transfer (SET), cross relaxation (CR), cooperative sensitization (CS), and cooperative luminescence(CL). For example, the energy transfer process of SET is shown in

Figure 1B: an activated ion in state 1 is elevated to state 2 by ET. The activated ion is then promoted again to state 3 by a second ET. Only the sensitized ions can absorb photons from the incident light in this process.

(3) Photon avalanche: Also known as absorption avalanche, photon avalanche was first discovered by Chivian and is one of the most efficient types of upconversion [

18]. Of all the upconversion processes, the photon avalanche process is the least observed.

Figure 1C shows the simple energy transfer process of the photon avalanche process. Initially, the sensitized ion (ion 1) in state 1 is promoted to state 2 by GSA. Next, an incident photon is pushed into state 3 by ESA. The basic process of photon avalanche is that an sensitized ion in state 3 (ion 1) can interact with an adjacent ion in the ground state (ion 2), and as a result of cross relaxation two ions are produced in state 2 (ion 1 and 2). Two newly created ions acting as sensitized ions can produce an additional four ions, which in turn can produce another eight ions, and so on. Finally, the intermediate excited state (state 2) acts as a storage vessel for energy and can build up an avalanche of ions in state 2.

2. Preparation Method of Upconversion Nanoparticles

2.1. Thermal Decomposition Method

Thermal decomposition method refers to the method of thermal decomposition of inorganic or organic precursors in high boiling point organic solvents, and is the traditional method used to prepare inorganic nanocrystals [

19,

20]. The specific process is generally composed of the following parts: (1) At room temperature, a certain amount of RE (CF3COO)3 precursor is added to the mixture of oleic acid (OA), 1-octadecene(OD) and organic oil amine (OM); (2) under the protection of argon and intense magnetic stirring,the solution is heated to 165 °C for 30 minutes to remove water and oxygen; (3) Under the protection of argon, the solution is heated to a high temperature (usually greater than 300 °C) for a period of time, and then the nanocrystals are cooled to room temperature to collect the products from the reaction mixture. The reaction temperature, reaction time, and the molar ratio of OA, OD, and OM in the reaction mixture all have an effect on the final nanocrystals. It should be noted that OM is sometimes introduced as a necessary component to regulate the reaction environment so that final products with different forms and sizes can be obtained(

Figure 2).

The most outstanding advantages of this method are the high quality of the product, the pure crystal phase and the strong upconversion luminescence ability [

20,

21]. However, this method also has the following disadvantages: (1) Pre-synthesis of RE (CF3COO)3 precursors is usually required; (2) the decomposition of trifluoroacetate produces toxic fluorinated and oxyfluorocarbon substances at the same time, so the reaction needs to be carefully handled in the fume hood; (3) the reaction environment requires inert atmosphore and dehydration, which further increases the difficulty of operation. In the pyrolysis method, the key factor to achieve size controllable and monodisperse UCNPs is the need to select the appropriate ligand. Yan et al. report that oleoamine ligands have significant effects on fluoride ion are an important buffer, because as the RE series atomic number increases, the alkalinity of RE oxides gradually decreases, so the lighter the rare earth element, the more OM is required [

22].

2.2. Coprecipitation Method

Due to the limitations of the thermal decomposition method, the coprecipitation method was developed and has been used as one of the most convenient methods for UCNPs synthesis [

23,

24]. The experimental process generally consists of the following parts: (1) RE salt is mixed with a solution of OA, OD (sometimes added with OM) at a certain proportion, heated to 165 °C and kept for 30 minutes, and then cooled to room temperature; (2) Methanol solution of NH4F and MOH (M = Li, Na, K) is added to the mixture and stirred for 30 minutes; (3) After removing the methanol and residual water by evaporation, the reaction mixture is heated to a high temperature (usually >300 °C) under the protection of argon to produce the desired nanocrystals (

Figure 3). The advantages of co-precipitation method are simple operation, non-toxic byproducts and low cost, so it is widely used in the preparation of various materials [

25,

26].

Although the synthesis of UCNPs by co-precipitation method has been significantly improved and has universal practicability, it is troubled by the long continuous operation of the experimental process, which usually takes more than 5 hours, including the removal of methanol solvent and the water generated during the synthesis process, and controlled crystal growth at a certain high temperature. In addition, the largescale synthesis of UCNPs using this method remains a major challenge.

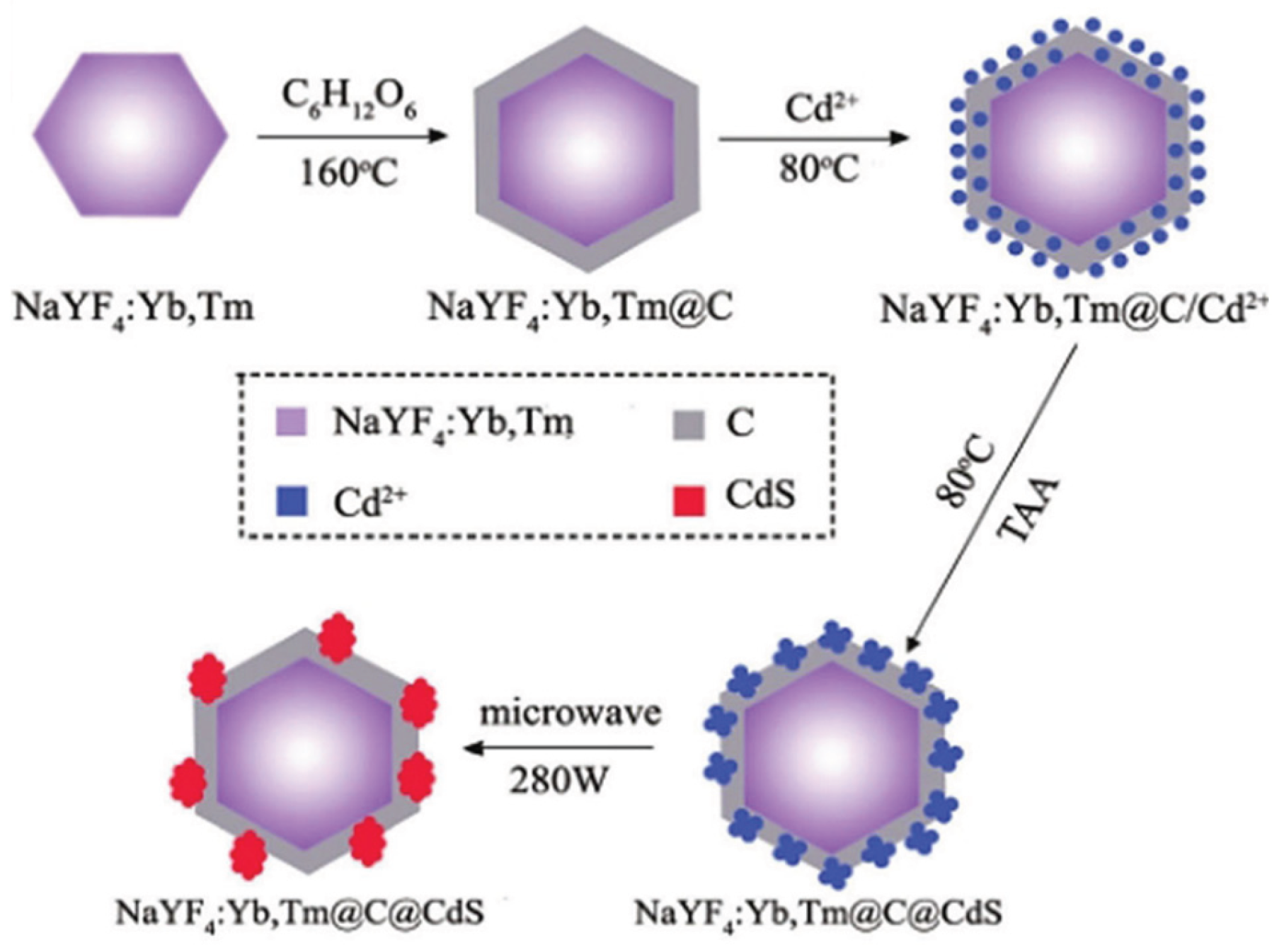

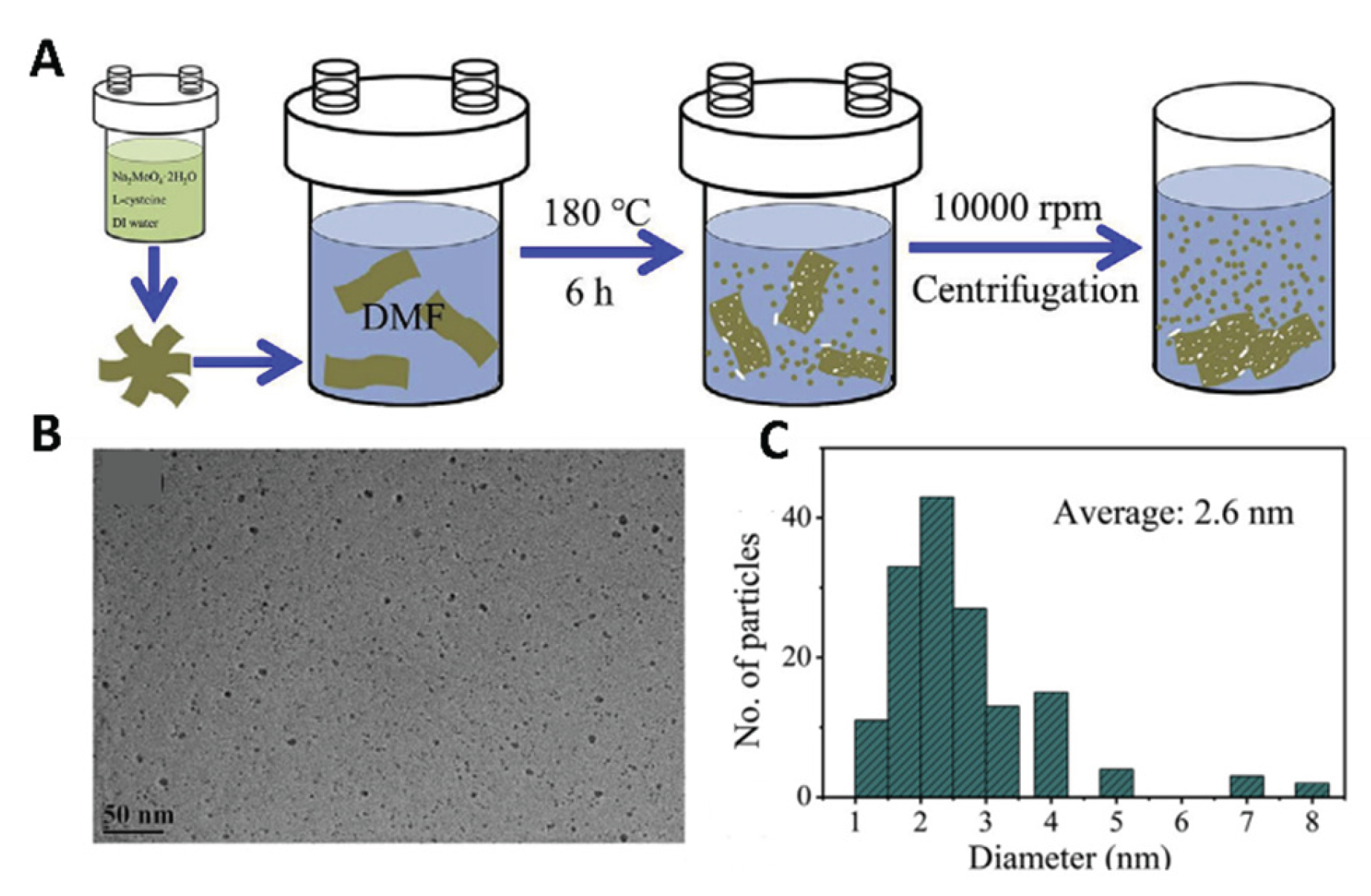

2.3. Hydrothermal/Solvothermal Method

Hydrothermal/solvothermal method is usually through a chemical reaction process between positive and negative ions, under high temperature and high pressure conditions to precipitate the product from the solvent, after appropriate treatment in the solvent to obtain nanoscale materials [

27,

28]. Because the method is simple to operate, the experimental process does not require strict operation, and the reaction temperature of the hydrothermal/solvothermal method is usually lower than that of the thermal decomposition method and co-precipitation method (

Figure 4), it is now widely used in the process of synthesizing UCNPs [

29,

30]. The advantages of using the hydrothermal/solvothermal method to synthesize high-quality UCNPs include: (1) high product purity, (2) easy control of the size, structure and morphology of the nanoparticles, (3) relatively low reaction temperatures (generally below 200 °C), and (4) the use of simple equipment and a simple overall process. However, in most cases, the hydrophilicity of UCNPs prepared using the hydrothermal/solvothermal method is insufficient due to the presence of hydrophobic organic ligands (such as OA) on the nanoparticle surface. Therefore, in order to improve the water solubility and biocompatibility of UCNPs, surface modification is a top priority.

2.4. Sol-Gel Method

Sol-gel method is a typical wet chemical method for the synthesis of UCNPs [

31,

32,

33], which can be generally divided into three types: (1) sol-gel route based on the hydrolysis and condensation of molecular precursors; (2) gelation route based on condensation of aqueous solution containing metal chelates; And (3) polymerizable complex routes. In the sol-gel method, rare earth nitrates or metallic alkols are usually used as starting reactants. By mixing the reactants in the liquid phase, a hydrolysis and condensation reaction is initiated, followed by a period of annealing at high temperatures

34. For the sol-gel method, the annealing process (temperature and time) is a critical step in the preparation process and can seriously affect the quality of the sample(

Figure 5). It should be noted that although the sol-gel method can be used for large-scale production, and the high crystallinity of the product formed at high annealing temperatures can provide high luminous intensity, the sol-gel derived nanocrystals usually have a wide particle size, irregular distribution, irregular morphology, and are insoluble in water, which are the disadvantages of the method.

3. Surface Modification of Upconversion Nanoparticles

Due to the effects of impurities and lattice defects on synthesized UCNPs, the quantum efficiency of UCNPs is lower than that of the corresponding bulk materials. In addition, because UCNPs are usually prepared in an organic environment, the particle surface is surrounded by hydrophobic molecules [

31,

35,

36], so they are mostly insoluble in water. Therefore, it is important to develop appropriate schemes to make them hydrophilic while maintaining upconversion efficiency to meet various requirements. For example, an ideal luminescent nanocrystal with good biocompatibility should meet several requirements, including: (1) high luminescent efficiency and low background noise; (2) good solubility and stability in the biological environment; (3) good biocompatibility, (4) appropriate size

1 (less than 100 nm).

However, UCNPs weakness is low upconversion efficiency [

37,

38]. At present, the urgent task is to improve the upconversion efficiency. Introducing inert crystal shells of undoped materials around each nanocrystalline doped with rare earth ions is an effective choice to improve the luminous efficiency of UCNPs [

39,

40]. The shell material usually has the same composition as the core master crystal, which can effectively reduce surface fluorescence quenching. In such structures, all doped ions are confined to the core of the nanocrystals, effectively inhibiting the non-radiative energy transfer from rare earth ions to the surface quenched site, which results in an increase in upconversion luminescence efficiency. As reported that wrapping 1.5 nm thick NaYF

4 shells on 8 nm NaYF

4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals enhanced their luminescence by nearly 30 times [

41,

42].

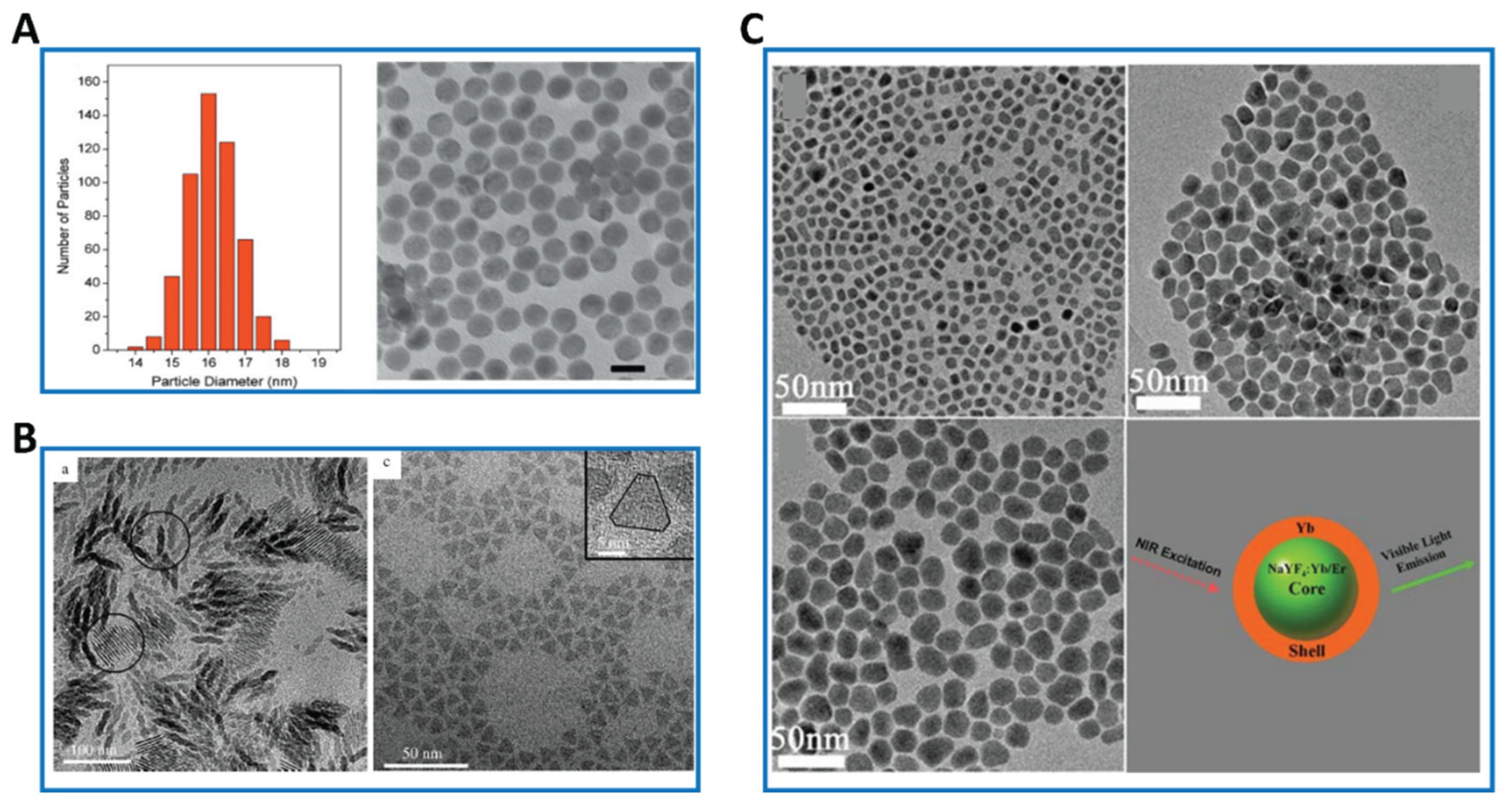

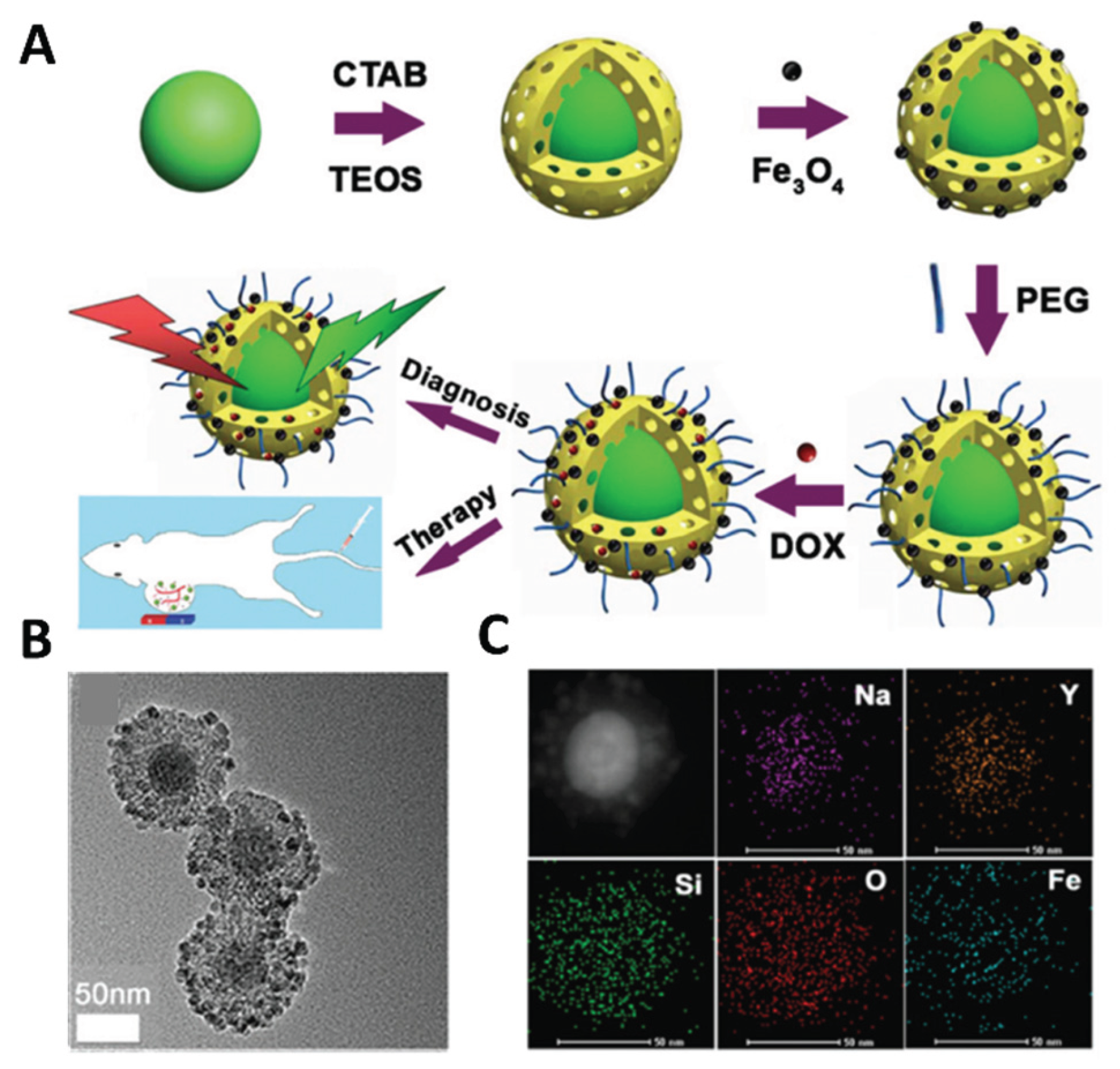

3.1. SiO2 Coating Method

SiO

2 coating involves the growth of amorphous silica shells on UCNPs cores [

43] (

Figure 6). Since SiO

2 coated UCNPs are rich in amino and carboxyl groups, amino and carboxyl group functionalization can be further utilized to achieve biomolecular coupling and their application in tumor therapy [

44,

45]. It provides a platform for the multifunctionalization of UCNPs. The disadvantage is that the method is time consuming and difficult to synthesize on a large scale. In addition, the coated SiO

2 layer may also affect the luminous intensity of UCNPs through light scattering, because the upconversion efficiency of UNCPs is already very low, so it cannot be an ideal surface modification method. Therefore, there is still a lot of work to be done to improve the general applicability of this method.

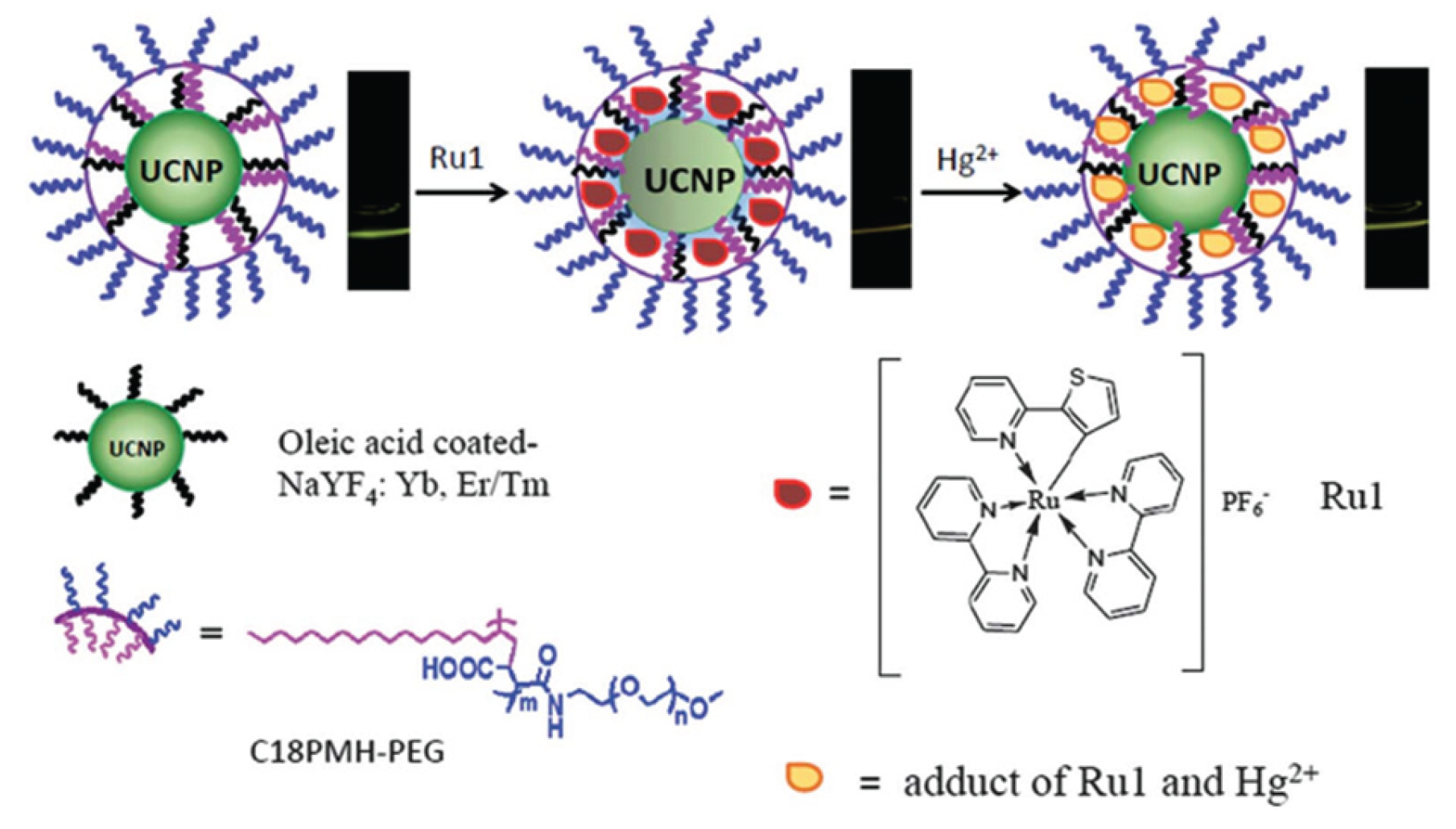

3.2. Polymer Coating Method

Polymer coating method refers to the use of the van der Waals effect between the hydrophobic chain of the amphiphilic polymer molecule and the hydrophobic chain on the surface of the nanoparticle [

46,

47], so that the polymer molecule is coated on the surface of the nanoparticle, and its hydrophilic end is exposed to make the nanoparticle water-soluble. The multifunctionalization of up-conversion nanoparticles can also be achieved by the amphiphilic coating. UCNPs can be formed by coating an amphiphilic polymer (C

18PMH-PEG) on NaYF

4:Yb/Er, Tm nanoparticles based on hydrophobic-hydrophobic interactions. The nanoparticle modified with the polymer will be used for selective luminescence detection of mercury ions in water. Using upconversion luminescence emission as the detection signal, the detection limit of mercury ions in aqueous solution of this nanoprobe is 8.2 ppb, which is much lower than the detection limit determined by UV/Vis technology (329 ppb)[

48] (

Figure 7). Compared with the SiO

2 coating method, the polymer-coated method is easier. In-situ coating of polymers on UCNPs surfaces demonstrates the development of multifunctional upconversion nanoparticles. However, coatings through hydrophobic interactions are unstable, and better methods are needed to form robust polymer coatings to meet a variety of application requirements.

3.3. Ligand Oxidation Method

Ligand oxidation method produces hydrophilic functional groups by oxidizing unsaturated carbon-carbon bonds contained in ligands on the surface of upconverted nanoparticles. It is reported that a large number of carboxylic acid groups will be produced on the surface of UCNPs after oxidation [

49], which not only makes the nanocrystals have good solubility in water, but also can be directly chemically coupled with biomolecules. The oxidation process has no significant negative effects on the shape, crystal structure, chemical composition and luminescence properties of upconverted nanomaterials [

49]. However, this method is limited to those nanoparticles that contain unsaturated carbon-carbon bond ligands. Because the experimental conditions are very demanding, the oxidation process may also result in the ligands being eliminated directly. If the oxidation of ligands can be achieved under mild experimental conditions, there will be no or less damage to the surface of UCNPs, which would be a more ideal situation. In addition, prolonged oxidation may result in the formation of brown MnO

2 by products, which are not easily separated and will weaken the upconversion fluorescence intensity [

50].

4. Biological Applications of Upconversion Nanoparticles

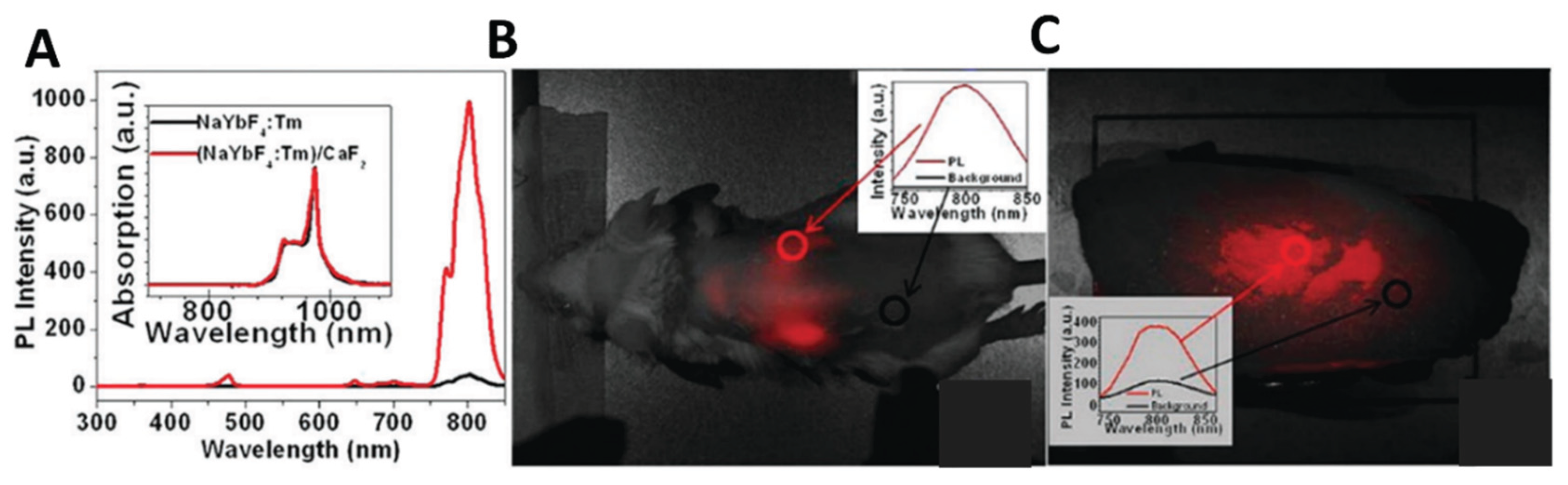

4.1. In Vitro Cell Imaging and In Vivo Tissue Imaging

Excitation of rare-earth-doped UCNPs usually requires only IR radiation. The use of IR radiation is of great advantage in cell and tissue imaging because they provide: (1) a high signal-to-noise ratio (2) long wavelength excitation light with great penetration (up to several inches of tissue penetration); And (3) long-term irradiation causes less light damage to cells/tissues [

51,

52]. Therefore, rare earth doped UCNPs is a good alternative to traditional fluorescent biomarkers (such as organic dyes and quantum dots) for in vitro cell imaging and in vivo tissue imaging.

(1) Labeling and imaging of in vitro cells. The application of UPCNs in vitro cell imaging can be divided into two scenarios. One is to covalently bind to targeted groups (such as folate, aptamer, protein, polypeptide, etc.), and use the targeted groups modified on the surface of up-conversion nanoparticles for in vitro cell imaging and targeted transport of tracer drugs; the other is to ingestion of up-conversion nanoparticles through cellular endocytosis for fluorescence imaging, so as to study the endocytosis mechanism and endocytosis of cells. Chatterjee et al.[

53] used NaYF

4:Yb,Er UCNPs for cell imaging for the first time. NaYF

4:Yb,Er UCNPs were functionalized by PEI and then covalently combined with folic acid to form folate-modified NaYF

4:Yb,Er UCNPs. Folate modified NaYF

4:Yb,Er UCNPs were then cultured with human HT29 breast cancer cell and human OVCAR3 ovarian cancer cells under physiological conditions for 24 hours. UCNPs modified with folate were able to specifically target the cells because of unusually high levels of folate receptors expressed on the surfaces of both types of cells, and when the folate modified UCNPs was connected to the cells, UCNPs could glow green upconversion fluorescence under a confocal microscope equipped with a 980nm laser (

Figure 8) .

(2) In vivo tissue imaging. Chatterjee et al.[

53] first reported the use of upconversion nanoparticles for in vivo imaging of deep tissue in Wistar rats. In their study, NaYF

4: Yb coated with PEI (5 wt %) and Er UCNPs were first used, and then 100 μL PEI-coated UCNPs (4.4 mg/mL) were injected subcutaneously into the groin and thigh sites of rats at a depth of 10 mm. The rats were then stimulated with a 980 nm excitation light source. The results showed that UCNPs injected into the skin of the abdomen, the muscle of the thigh and under the skin of the back showed visible fluorescence under a 980 nm excitation light source. However, when the quantum dots QDs (used as a control) were injected into the thicker skin of the back or abdomen, they did not show any fluorescence under UV excitation, and only the quantum dots injected into the translucent skin of the feet fluoresced. Thus, NIR radiation has been demonstrated to have better penetration than UV light, and NIR light-stimulated UCNPs has great potential for in vivo imaging and their application in tumor therapeutic. However, judging from the existing literature, the use of UCNPs for in vivo imaging is still at a preliminary stage.

4.2. Biological Detection and Analysis

(1) FRET based detection. Flourescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) is a process that occurs when energy is transferred between a donor and recipient. When the absorption spectra of two fluorescent molecules (energy donor and energy accepter) overlap in a certain region, and the distance between the donor and the accepter is less than 10 nanometers, the fluorescence molecule as an energy accepter can absorb the photon radiated by another fluorescent molecule as an energy donor, and energy transfer occurs. This process is called FRET. In recent years, FRET based analytical methods have received considerable attention as an important tool for biological detection due to their ease of operation and high sensitivity.

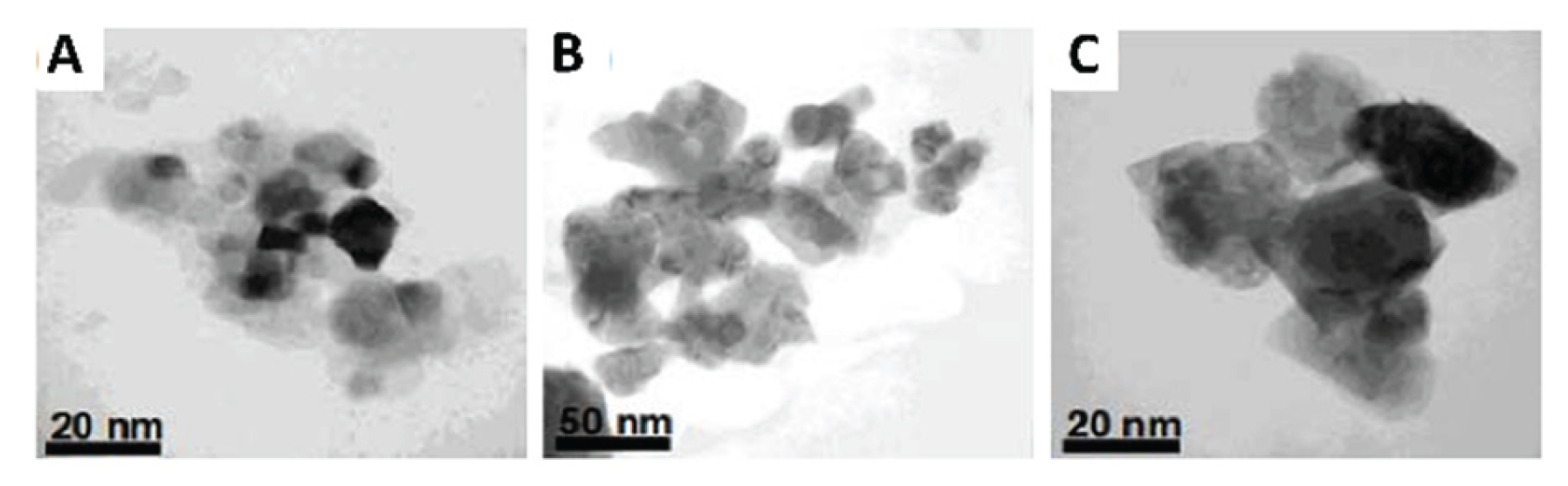

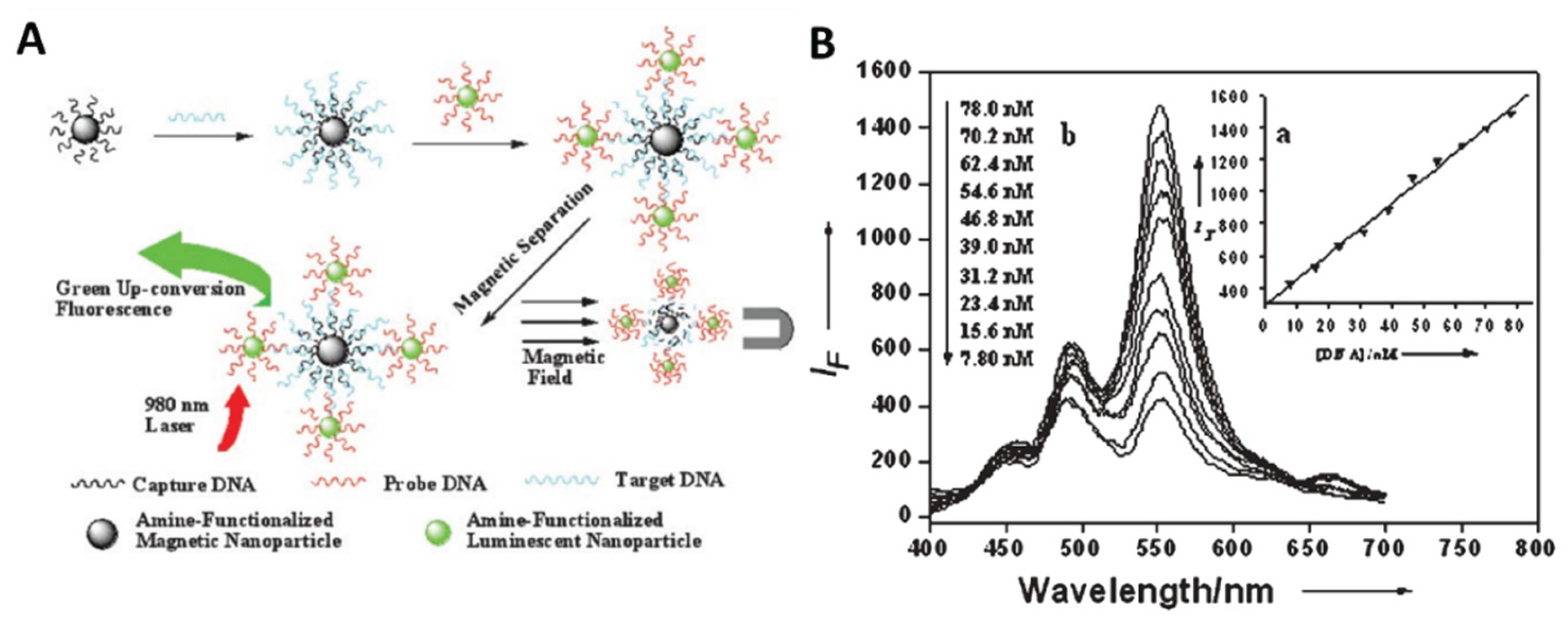

(2) Direct detection of biomolecules, also known as heterophase detection, refers to the specific recognition and high affinity between the molecules to be measured fixed on the substrate and the rare earth doped UCNPs labeled probe molecules. The detection based on bioaffinity system is realized according to the proportional relationship between the concentration of the object to be measured and the fluorescence intensity. Wang et al.

54 used NaYF

4:Yb, Er UCNPs to design a fluorescence sensor based on magnetic field separation to detect trace DNA sensitively(

Figure 9). Firstly, Fe

3O

4 magnetic nanoparticles were covalently linked to the capture DNA, and NaYF

4:Yb,Er UCNPs were covalently linked to the probe DNA. When the target DNA is added to the system, the long strand of target DNA can specifically recognize the complementary sequence fragments on the trapping DNA connected to the Fe

3O

4 magnetic nanoparticle and the probe DNA connected to the UCNPs, and finally form a three-strand nanocomplex, which is then purified by magnetic separation. It was found that the upconversion fluorescence intensity of UCNPs was linearly correlated with the concentration of target DNA in the range of 7.8-78.0 nm. This method is a good choice for detecting trace amounts of DNA.

4.3. Diagnosis and Treatment

The application of upconversion nanoparticles in the field of tumor diagnosis and treatment mainly involves the following three aspects:

(1) Drug delivery. The UCNPs-based drug delivery system can be used for drug tracer, evaluation of drug delivery efficiency and study of drug deliverymechanism. To date, most UCNPs drug delivery systems have been coated with PEG [

55,

56] or mesoporous silica [

57,

58,

59]. Liu and colleagues functionalized the amphiphilic polymer PEG by wrapping it in UCNPs, then loaded DOX molecules with pegylated UCNPs and covalently bound to FA for targeted drug delivery and cell imaging. The loading and release of DOX in UCNPs is controlled by changing pH, the drug dissociation rate increases in acidic environment, which is conducive to the control of drug release [

60].

(2) Photodynamic therapy (PDT). PDT is a relatively new clinical treatment method, which refers to the photosensitized agent that converts the adsorbated oxygen into reactive oxygen species or singlet oxygen to kill disease cells under the condition of high energy excitation light [

61,

62]. However, the high energy of the excitation light source is mostly visible light or even ultraviolet light, which limits the penetration depth of photodynamic therapy, and it is impossible to treat deep-seated tumors or too large tumors. While upconversion nanomaterials can emit visible light when excited by near infrared light, UCNPs can be used to activate photosensitizers in deep tissues, and the penetration depth of tissues can be increased due to weak absorption in the optical “transparent window”.

(3) Photothermodynamic therapy (PTT). PTT is a treatment that absorbs radiation light energy through a light absorber to generate heat, resulting in the local temperature of tumor cells being too high and thus dying. Various nanomaterials with high near-infrared absorbance, such as gold and silver nanoshells, nanorods and nanocages, have been used for PTT treatment of tumors [

63]. Song et al. reported the hexagonal phase NaYF

4 of the core-shell structure and their unique biological functional properties [

64] showed that HepG2 cells from human liver cancer and BCap-37 cells from human breast cancer were cultured with UCNPs in vitro and photothermally induced death occurred when exposed to a 980 nm excitation light source.

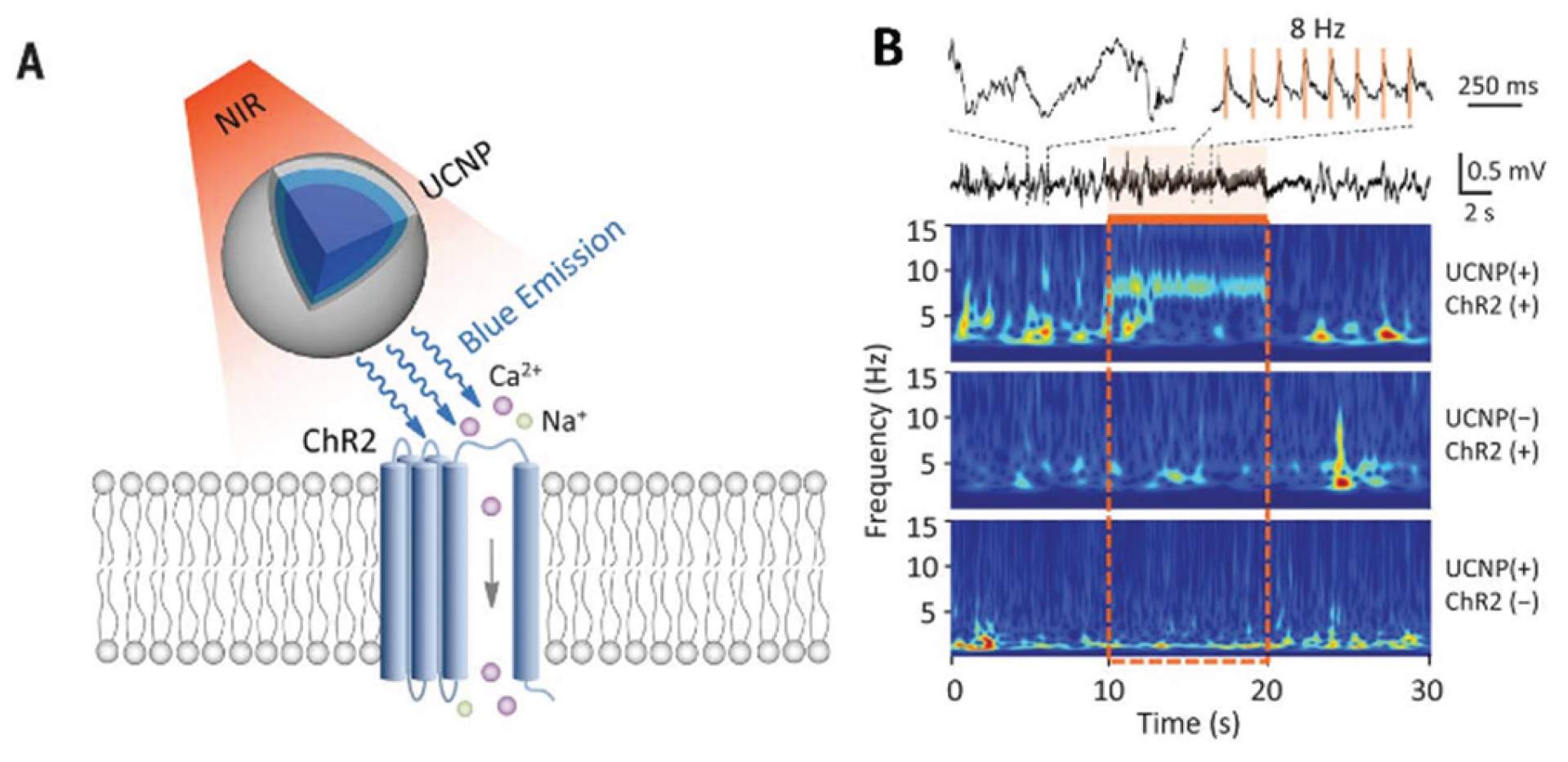

4.4. Optogenetics

Optogenetics has completely revolutionized the experimental study of neural circuits. It is expected to be used for treating neurological diseases. However, it’s limited because visible light cannot penetrate deeply into the brain tissue. UCNPs absorb near-infrared (NIR) light that penetrates the tissue and emit light of specific wavelengths. UCNP technology will facilitate minimally invasive optical manipulation of neuronal activity, offering potential for remote therapy applications. A non-invasive deep brain stimulation technique based on UCNPs has been developed by Chen et al. [

65](

Figure 10). The activation of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), the inhibition of hippocampal neurons, and the triggering of memory recall were successfully achieved. It demonstrated the application potential of UCNPs in various neural regulation scenarios. Hososhima et al.[

66]combined Lanthanide element nanoparticles with optogenetics for the first time and verified the matching of Lanthanide element nanoparticles with photosensitive protein in vitro experiments, and achieved the activation of neurons, providing a new idea for deep brain stimulation. In addition, a NIR optogenetic system based on lanthanide nanoparticles (LNPs) and photosensitive proteins (such as ChR2) was also proposed [

67]. The matching between LNPs and ChR2 was verified in vitro experiments, and the activation of neurons was achieved, providing a new idea for deep brain stimulation. It can be seen from this that upconversion nanoparticles have provided an important technological breakthrough for deep brain stimulation and neural regulation, demonstrating the broad prospects of the combination of optogenetics and nanotechnology. In the future, more precise targeted delivery methods should be developed to reduce side effects and explore their application potential in more neurological disease models.

5. Conclusion and Perspectives

Upconversion materials possess the ability to convert near-infrared radiation with lower energy into visible radiation with higher energy through nonlinear optical processes. Due to their unique luminescent properties, upconversion luminescent substances exhibit numerous advantages, such as large Stokes shift, strong photostability; good chemical and physical stability, low toxicity; near-infrared light excitation can reduce tissue damage to the organism while enhancing tissue penetration depth; zero background in the imaging process, which can significantly improve detection and imaging sensitivity. Therefore, upconversion nanoluminescent materials have great development potential in biology.

The core challenge in the application of up-converting nanoparticles (UCNPs) in biological analysis lies in their low luminescence efficiency, which limits the detection sensitivity. The complex surface chemistry makes biological functionalization difficult and prone to stability issues. The uncontrollability of size and morphology affects their biological distribution and pharmacokinetics, and the long-term biological safety and in vivo metabolic pathways remain unclear. To address these problems, future development will focus on fundamentally improving the luminescence efficiency by designing new core-shell structures (such as sensitizing shells or heterojunctions) and exploring non-terrestrial materials; developing standardized and replicable biological coupling strategies to achieve stable multifunctionality; and using artificial intelligence-assisted design to optimize synthesis parameters and performance. The ultimate goal is to achieve integrated multimodal diagnosis and treatment in deep tissues excited in the NIR-II region, combining high-resolution imaging with photodynamic/photothermal/chemotherapy, and promoting breakthrough applications in clinical translation areas such as high-sensitivity multiple detection, intraoperative navigation, and real-time feedback-based drug monitoring.”

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L..; methodology; software.; formal analysis, M.L.; investigation, J.W.; resources, L.L.; data curation, M.L.; writing—original draft preparation,; writing—review and editing, L.L.; visualization, P.W.; supervision, L.L.; project administration, L.L.; funding acquisition, L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Qing Lan Project of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions and the Technology Innovation Team project of Yancheng Polytechnic College, grant number YGKJ202505.

Acknowledgments

The project was funded by the Technology Innovation Team project of Yancheng Polytechnic College. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks all the team members for their assistance. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, F.; Tu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, D.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Du, J.; Fan, R.; Yang, C.; Kraemer, K. W.; Marques-Hueso, J.; Chen, G. Size-dependent lanthanide energy transfer amplifies upconversion luminescence quantum yields. Nat. Photonics 2024, 18, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Sen Gupta, R.; Bose, S. A comprehensive review on singlet oxygen generation in nanomaterials and conjugated polymers for photodynamic therapy in the treatment of cancer. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 3243–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Feng, J.; Gao, X.; Zhang, H. Nanocomposites based on lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles: diverse designs and applications. Light Sci. Appl. 2022, 11.222. [Google Scholar]

- Leiner, M. J. P. Luminescence chemical sensors for biomedical applications - scope and limitations S. Anal. Chim. Acta 1991, 255, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roda, A.; Guardigli, M.; Pasini, P.; Mirasoli, M.; Michelini, E.; Musiani, M. Bio- and chemiluminescence imaging in analytical chemistry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 541, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sheng, W.; Haruna, S. A.; Hassan, M. M.; Chen, Q. Recent advances in rare earth ion-doped upconversion nanomaterials: From design to their applications in food safety analysis. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. F. 2023, 22, 3732–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinegoni, C.; Razansky, D.; Hilderbrand, S. A.; Shao, F.; Ntziachristos, V.; Weissleder, R. Transillumination fluorescence imaging in mice using biocompatible upconverting nanoparticles. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34, 2566–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C. T.; Svensson, N.; Axelsson, J.; Svenmarker, P.; Somesfalean, G.; Chen, G.; Liang, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Andersson-Engels, S. Autofluorescence insensitive imaging using upconverting nanocrystals in scattering media. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93(17), 171103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Zhang, Q. Recent Advances on Functionalized Upconversion Nanoparticles for Detection of Small Molecules and Ions in Biosystems. Adv.Sci. 2018, 5, 170069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wang, F. Combating Concentration Quenching in Upconversion Nanoparticles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Jeon, E.; Kim, S.; Lee, J. Lanthanide-Doped Upconversion Nanomaterials: Recent Advances and Applications. Biochip J. 2020, 14, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, K.; Umezawa, M.; Soga, K. Review-Concept and Application of Thermal Phenomena at 4f Electrons of Trivalent Lanthanide Ions in Organic/Inorganic Hybrid Nanostructure. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 096006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Fu, H.; Jing, H.; Hu, X.; Chen, D.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Qin, X.; Huang, W. Synergistic Integration of Halide Perovskite and Rare-Earth Ions toward Photonics. Adv. Mater. 2025, 2417397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Deng, R.; MacDonald, M. A.; Chen, B.; Yuan, J.; Wang, F.; Chi, D.; Hor, T. S. A.; Zhang, P.; Liu, G.; Han, Y.; Liu, X. Enhancing multiphoton upconversion through energy clustering at sublattice level. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Loh, K. Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Fan, J.; Jung, T.; Nam, S. H.; Suh, Y. D.; Liu, X. Recent advances in upconversion nanocrystals: Expanding the kaleidoscopic toolbox for emerging applications. Nano Today 2019, 29, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, M.-K.; Bai, G.; Hao, J. Stimuli responsive upconversion luminescence nanomaterials and films for various applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1585–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Yu, J. In Situ Irradiated X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Investigation on Electron Transfer Mechanism in S-Scheme Photocatalyst. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 8462–8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Peng, D.; Chai, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, B.; Shen, D. Upconversion photoluminescence properties of Er3+ doped CaBi2Nb2O9 phosphors for temperature sensing. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. 2017, 28, 11921–11925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrone, F.; Naccache, R.; Mahalingam, V.; Morgan, C. G.; Capobianco, J. A. The Active-Core/Active-Shell Approach: A Strategy to Enhance the Upconversion Luminescence in Lanthanide-Doped Nanoparticles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 2924–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Li, C.; Li, G.; Shang, M.; Kang, X.; Lin, J. Colloidal synthesis and remarkable enhancement of the upconversion luminescence of BaGdF5:Yb3+/Er3+ nanoparticles by active-shell modification. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 5923–5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wang, F. Recent advances in the synthesis and application of Yb-based fluoride upconversion nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 1067–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y. W.; Du, Y. P.; Yan, Z. G.; Si, R.; You, L. P.; Yan, C.-H. From trifluoroacetate complex precursors to monodisperse rare-earth fluoride and oxyfluoride nanocrystals with diverse shapes through controlled fluorination in solution phase. Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 2320–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, C.; Qian, H. Recent Advances in Controlled Synthesis of Upconversion Nanoparticles and Semiconductor Heterostructures. Chem.Rec 2020, 20, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Zhang, W.; Sun, J. Structure and upconversion luminescence properties of BaYF5:Yb3+, Er3+ nanoparticles prepared by different methods. J. Alloys Compd 2011, 509, 3413–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passuello, T.; Piccinelli, F.; Pedroni, M.; Bettinelli, M.; Mangiarini, F.; Naccache, R.; Vetrone, F.; Capobianco, J. A.; Speghini, A. White light upconversion of nanocrystalline Er/Tm/Yb doped tetragonal Gd4O3F6. Opt. Mater. 2011, 33, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passuello, T.; Piccinelli, F.; Pedroni, M.; Polizzi, S.; Mangiarini, F.; Vetrone, F.; Bettinelli, M.; Speghini, A. NIR-to-visible and NIR-to-NIR upconversion in lanthanide doped nanocrystalline GdOF with trigonal structure. Opt. Mater. 2011, 33, 1500–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Wei, Q.; Ren, P.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y. Hydrothermal-solvothermal cutting integrated synthesis and optical properties of MoS2 quantum dots. Opt. Mater. 2018, 86, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Michael, E.; Komarneni, S.; Brownson, J. R.; Yan, Z. F. Microwave-hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis of kesterite, an emerging photovoltaic material. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 1985–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Li, B. Hydrothermal solvothermal synthesis and microwave absorbing study of MCo2O4(M = Mn, Ni) microparticles. Adv. Appl. Ceram 2019, 118, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisang, W.; Phuruangrat, A.; Thongtem, S.; Thongtem, T. Photoluminescence and photonic absorbance of Ce2(MoO4)3nanocrystal synthesized by microwave-hydrothermal/solvothermal method. Rare Met. 2018, 37, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Xie, J.; Zhao, B.; Liu, B.; Xu, S.; Ren, N.; Xie, X.; Huang, L.; Huang, W. Rare Earth Ion-Doped Upconversion Nanocrystals: Synthesis and Surface Modification. Nanomaterials 2015, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, R.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, P.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y. NIR-II upconversion nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 2985–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasleem, S.; Tahir, M. Recent progress in structural development and band engineering of perovskites materials for photocatalytic solar hydrogen production: A review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, 45, 19078–19111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, B. P.; Karmakar, A.; Ghosh, A. Recent Advancements in Ln-Ion-Based Upconverting Nanomaterials and Their Biological Applications. Part Part Syst. Char 2019, 36, 1900153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfbeis, O. S. An overview of nanoparticles commonly used in fluorescent bioimaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4743–4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Huang, L.; Han, G. Dye Doped Metal-Organic Frameworks for Enhanced Phototherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Zhou, J.; Schuck, P. J.; Suh, Y. D.; Schmidt, T. W.; Jin, D. Future and challenges for hybrid upconversion nanosystems. Nat. Photonics 2019, 13, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, B. S.; Hudry, D.; Busko, D.; Turshatov, A.; Howard, I. A. Photon Upconversion for Photovoltaics and Photocatalysis: A Critical Review. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 9165–9195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroter, A.; Hirsch, T. Control of Luminescence and Interfacial Properties as Perspective for Upconversion Nanoparticles. Small 2024, 20, 2306042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yan, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, B. Controlling upconversion in emerging multilayer core-shell nanostructures: from fundamentals to frontier applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 1729–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arppe, R.; Hyppanen, I.; Perala, N.; Peltomaa, R.; Kaiser, M.; Wuerth, C.; Christ, S.; Resch-Genger, U.; Schaferling, M.; Soukka, T. Quenching of the upconversion luminescence of NaYF4:Yb3+,Er3+ and NaYF4:Yb3+,Tm3+ nanophosphors by water: the role of the sensitizer Yb3+ in non-radiative relaxation. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 11746–11757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Guo, X.; He, G.; Qin, W. Ultraviolet Upconversion Emissions of Gd3+ in β-NaLuF4:Yb3+,Tm3+,Gd3+ Nanocrystals. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 3722–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Li, C.; Ma, P. a.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Z.; Huang, S.; Lin, J. Multifunctional NaYF4:Yb, Er@mSiO2@Fe3O4-PEG nanoparticles for UCL/MR bioimaging and magnetically targeted drug delivery. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 1839–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Zheng, W.; Li, Y. Silica-Coated Ga(III)-Doped ZnO: Yb3+, Tm3+Upconversion Nanoparticles for High-Resolution in Vivo Bioimaging using Near-Infrared to Near-Infrared Upconversion Emission. Inorg. Chem 2019, 58, 8230–8236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, F.; Xu, J.; Zhou, K.; Chen, C.; Cheng, J.; Li, P. Upconversion fluorescence enhancement of NaYF4:Yb/Re nanoparticles by coupling with SiO2 opal photonic crystals. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 8461–8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, K.; Fuku, R.; Kumar, B.; Hrovat, D.; Van Houten, J.; Piunno, P. A. E.; Gunning, P. T.; Krull, U. J. Unlocking Long-Term Stability of Upconversion Nanoparticles with Biocompatible Phosphonate-Based Polymer Coatings br. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 7285–7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Yang, Y. Upconversion circularly polarized luminescence of cholesteric liquid crystal polymer networks with NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNPs. Mater. Horiz. 2024, 11, 6455–6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zou, X.; Yao, L.; Li, F.; Feng, W. Cyclometallated ruthenium complex-modified upconversion nanophosphors for selective detection of Hg2+ ions in water. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Hu, H.; Yu, M.; Li, F.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Yi, T.; Huang, C. Versatile synthesis strategy for carboxylic acid-functionalized upconverting nanophosphors as biological labels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3023–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccache, R.; Vetrone, F.; Mahalingam, V.; Cuccia, L. A.; Capobianco, J. A. Controlled Synthesis and Water Dispersibility of Hexagonal Phase NaGdF4:Ho3+/Yb3+ Nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Liang, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, R.; Xu, Z. P. Recent progress in upconversion luminescence nanomaterials for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Jin, R.; Su, Q. Preparation and applications of polymer-modified lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles. Giant 2022, 12, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatteriee, D. K.; Rufalhah, A. J.; Zhang, Y. Upconversion fluorescence imaging of cells and small animals using lanthanide doped nanocrystals. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Y. Green upconversion nanocrystals for DNA detection. Chem. Comm. 2006, 2557–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Cheng, L.; Liu, Z. Drug delivery with upconversion nanoparticles for multi-functional targeted cancer cell imaging and therapy. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Gu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Yin, W.; Liu, X.; Yan, L.; Jin, S.; Ren, W.; Xing, G.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y. Mn2+ Dopant-Controlled Synthesis of NaYF4:Yb/Er Upconversion Nanoparticles for in vivo Imaging and Drug Delivery. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gai, S.; Yang, P.; Li, C.; Wang, W.; Dai, Y.; Niu, N.; Lin, J. Synthesis of Magnetic, Up-Conversion Luminescent, and Mesoporous Core-Shell-Structured Nanocomposites as Drug Carriers. Adv. Funct. Mater 2010, 20, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. N.; Bu, W.; Pan, L. M; Zhang, S.; Chen, F.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, K.-l.; Peng, W.; Shi, J. Simultaneous nuclear imaging and intranuclear drug delivery by nuclear-targeted multifunctional upconversion nanoprobes. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 7282–7290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Hao, R.; Qian, H.; Sun, S.; Sun, D.; Yin, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X. Upconversion nanoparticles modified with aminosilanes as carriers of DNA vaccine for foot-and-mouth disease. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E.; Liu, L.; Bai, L.; Xia, C.; Gao, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, B. Control synthesis, subtle surface modification of rare-earth-doped upconversion nanoparticles and their applications in cancer diagnosis and treatment. Mat. Sci. Eng. C-Mater 2019, 105, 110097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Y.-E. L.; Fan, W.; Hah, H.; Xu, H.; Orringer, D.; Ross, B.; Rehemtulla, A.; Philbert, M. A.; Kopelman, R. Photonic explorers based on multifunctional nanoplatforms for biosensing and photodynamic therapy. Appl.Opt 2007, 46, 1924–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, G. R.; Bhojani, M. S.; McConville, P.; Moody, J.; Moffat, B. A.; Hall, D. E.; Kim, G.; Koo, Y.-E. L.; Woolliscroft, M. J.; Sugai, J. V.; Johnson, T. D.; Philbert, M. A.; Kopelman, R.; Rehemtulla, A.; Ross, B. D. Vascular targeted nanoparticles for imaging and treatment of brain tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 6677–6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Hong, E.; Wang, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hu, R.; Wang, B. Advances in the application of upconversion nanoparticles for detecting and treating cancers. Photodiagn. Photodyn. 2019, 25, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Xu, S.; Sun, J.; Bi, S.; Li, D.; Bai, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Song, H. Multifunctional NaYF4: Yb3+, Er3+@Agcore/shell nanocomposites: integration of upconversion imaging and photothermal therapy. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 6193–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Weitemier, A. Z.; Zeng, X.; He, L. M.; Wang, X. Y.; Tao, Y. Q.; Huang, A. J. Y.; Hashimotodani, Y.; Kano, M.; Iwasaki, H.; Parajuli, L. K.; Okabe, S.; Teh, D. B. L.; All, A. H.; Tsutsui-Kimura, I.; Tanaka, K. F.; Liu, X. G.; McHugh, T. J. Near-infrared deep brain stimulation via upconversion nanoparticle-mediated optogenetics. Science 2018, 359, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hososhima, S.; Yuasa, H.; Ishizuka, T.; Hoque, M. R.; Yamashita, T.; Yamanaka, A.; Sugano, E.; Tomita, H.; Yawo, H. Near-infrared (NIR) up-conversion optogenetics. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, G.; Tan, P.; Li, Z.; Zang, S.; Wu, X.; Jing, J.; Fang, S.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hogan, P. G.; Han, G.; Zhou, Y. Near-infrared photoactivatable control of Ca2+ signaling and optogenetic immunomodulation. eLife 2015, 4, e10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).