1. Introduction

Continuous monitoring of physiological and behavioral parameters in lab animals is crucial to modern science, medicine, and biological research(1). Accurate assessment of heart rate, blood oxygen, and locomotion is essential for understanding the physical abilities of a lab animal. Visual monitoring is limited by line-of-sight and lacks internal physiological detail like ECG. This is particularly useful in medicine to track the response to a treatment. Traditionally, these vitals are monitored with either a tethered or surgically implanted telemetry system(2)(4). However, these designs often reduce adaptability to the animal’s dynamic behavior, and invasive procedures can lead to high stress post-operation(9). Furthermore, these solutions are often cost-prohibitive and restricted by finite battery life, which can limit the scope of long-term experimental investigations.

Recent advancements in microelectronics and 3D printing(10) allow for the development of more efficient telemetry solutions. This paper introduces a novel, non-invasive telemetry platform built on the ESP32-S3 microcontroller. Our device is housed in a 3D-printed enclosure designed for external attachment to rats, bypassing the need for surgical intervention. The system integrates a BioAmp EXG Pill, a high-performance analog front-end (AFE) for publication-grade ECG signals, alongside an ISM330DHCX 6-axis inertial measurement unit (IMU) for movement analysis and a pulse oximeter for blood oxygen saturation. Additionally, the system includes integrated sensors animal’s container to track food and water consumption, providing a comprehensive data set of the subject's status.

A primary engineering challenge in mobile telemetry is managing the high-volume inbound data stream required for real-time monitoring. Our architecture addresses this by performing on-chip preprocessing of the ECG, temperature, and IMU data. This synchronized stream is then processed via Tamp, which significantly decreases data volume to meet the throughput constraints of Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE). By optimizing the uplink to a central server, we minimize radio "on-time" and power consumption. To ensure indefinite operational longevity, we implement a magnetic resonance wireless charging system. This technology facilitates autonomous charging through 2.5 cm of solid non-conductive material, such as the cage floor, ensuring a continuous power supply and making the system ideal for long-term, autonomous data collection.

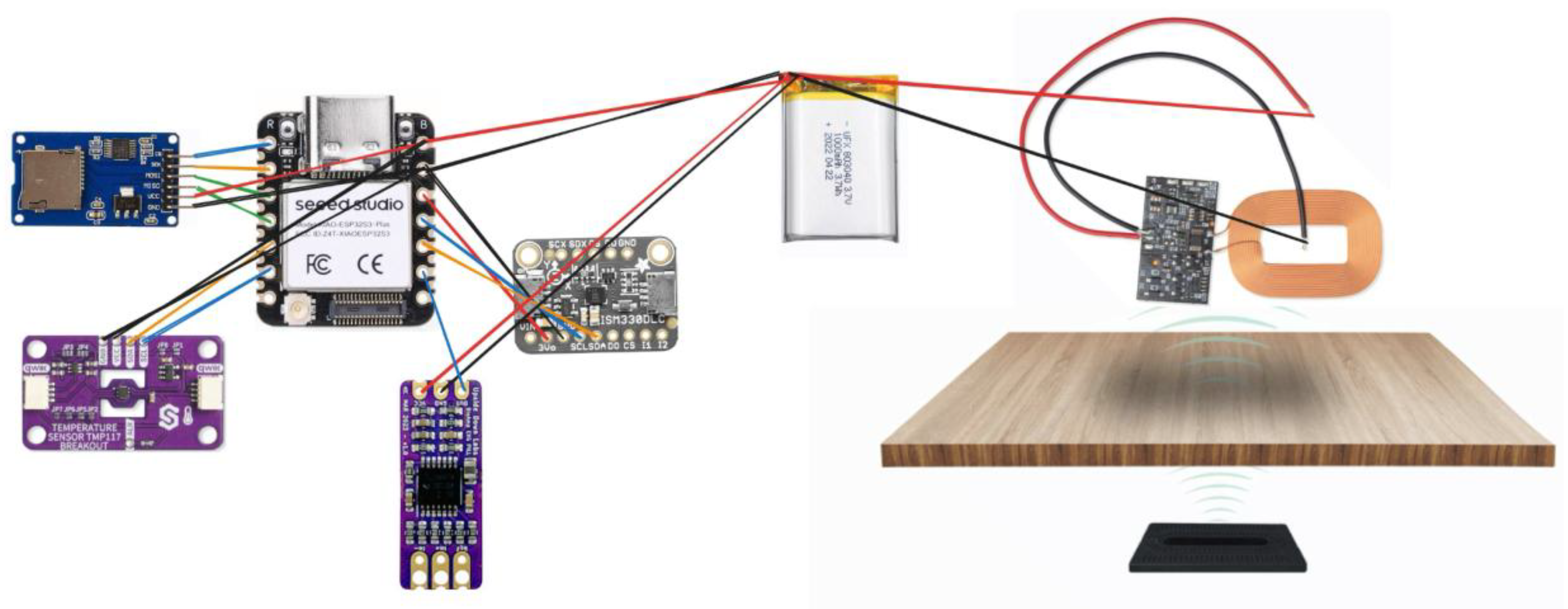

Figure 1.

Circuit Diagram of the hardware components.

Figure 1.

Circuit Diagram of the hardware components.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Overview

The proposed system is an embedded platform designed to acquire, compress, store, and transmit multiple biosignals in real time. The central processing unit is an ESP32-S3 microcontroller, selected due to its dual-core architecture, integrated Bluetooth Low Energy radio, and sufficient computational capability for signal processing tasks(11)(12).

The system performs several operations concurrently. High-rate biosignals are sampled, buffered, and processed in fixed-duration frames. These frames are compressed using a custom lossless pipeline and then transmitted over BLE. At the same time, all acquired data is written to an SD card. This dual-path design ensures that wireless transmission failures do not compromise data collection.

The complete processing flow is strictly ordered and deterministic: sensor sampling, temporal alignment, buffering, compression, packet assembly, BLE transmission, and SD storage. All buffers are statically allocated, and no dynamic memory allocation is used during runtime.

Outside the wearable, there are also other additions in the container for the rat itself. There are container trackers for food and water integrated via a central base station, as well as resonant charging transmitters underneath the container to charge the wearable.

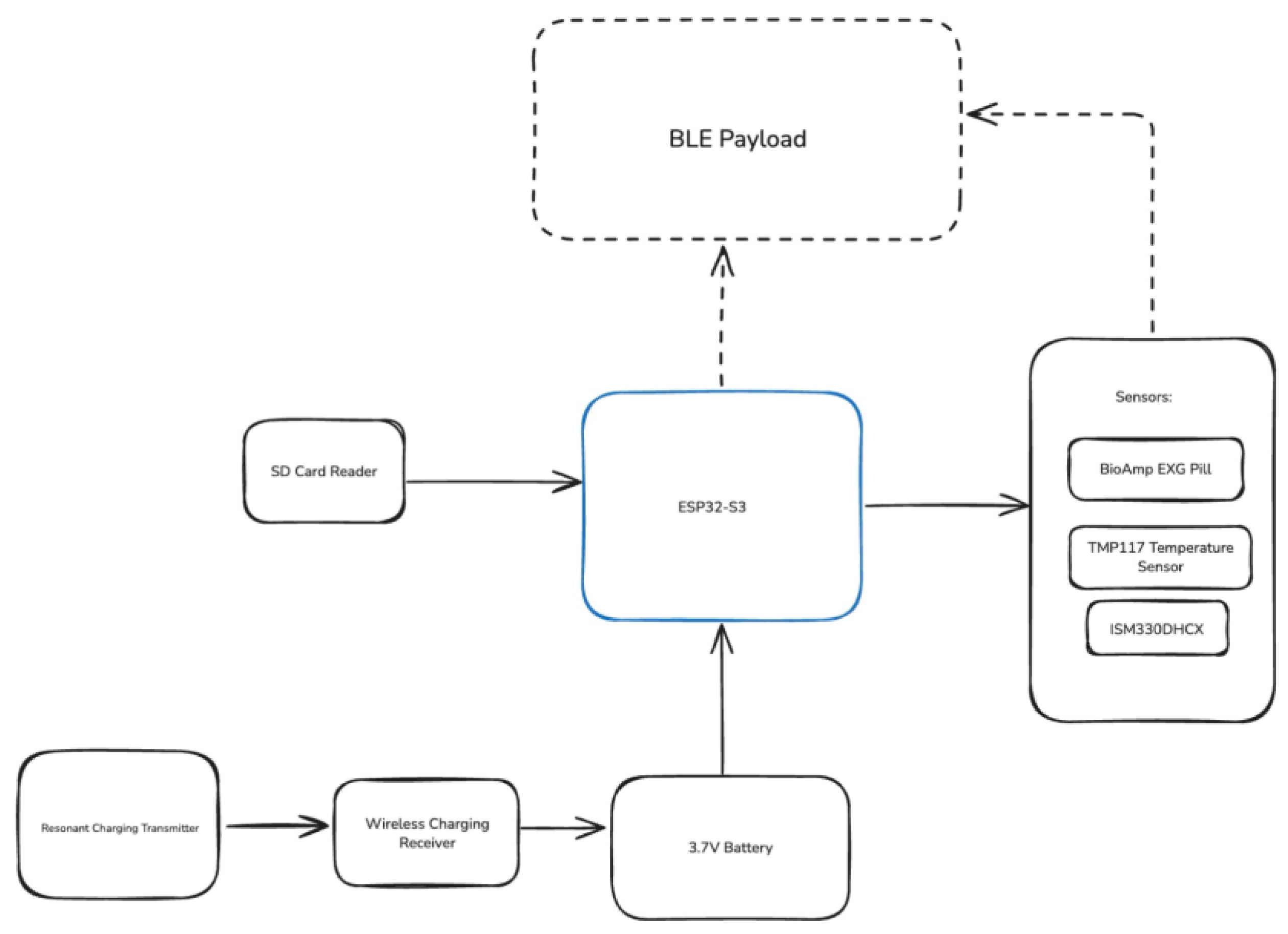

Figure 2.

The Wearable System Overview, listing all the hardware parts and outgoing data.

Figure 2.

The Wearable System Overview, listing all the hardware parts and outgoing data.

2.2. Sensor Acquisition and Sampling

2.2.1. Electrocardiogram Acquisition

Electrocardiogram (ECG) data is acquired using the analog-to-digital converter of the ESP32-S3 at a sampling rate of 2000 Hz. Each sample is stored as a signed 16-bit integer. This representation preserves the full resolution of the ADC while simplifying arithmetic operations during preprocessing.

ECG data represents the dominant portion of the total data volume generated by the system. As a result, any improvement in ECG compression efficiency has a direct and significant impact on overall bandwidth usage and storage requirements.

2.2.2. Inertial Measurement Unit Acquisition

Motion data is obtained using the ISM330DHCX inertial measurement unit. Both accelerometer and gyroscope signals are sampled at 500 Hz along the X, Y, and Z axes. Each axis is encoded as a signed 16-bit integer.

Physical motion signals are constrained by inertia and mechanical continuity. This results in a strong correlation between successive samples, making IMU data particularly suitable for prediction-based preprocessing.

2.2.3. Low-Frequency Physiological and Environmental Signals

Body temperature is measured using a TMP117 digital temperature sensor. Ambient light intensity is measured using a BH1750 sensor. Battery level is monitored using an analog input on the ESP32-S3.

These signals are sampled once every 30 seconds. Their data rate is several orders of magnitude lower than that of ECG and IMU signals. For this reason, they are transmitted in raw form without compression, simplifying implementation without significantly affecting bandwidth.

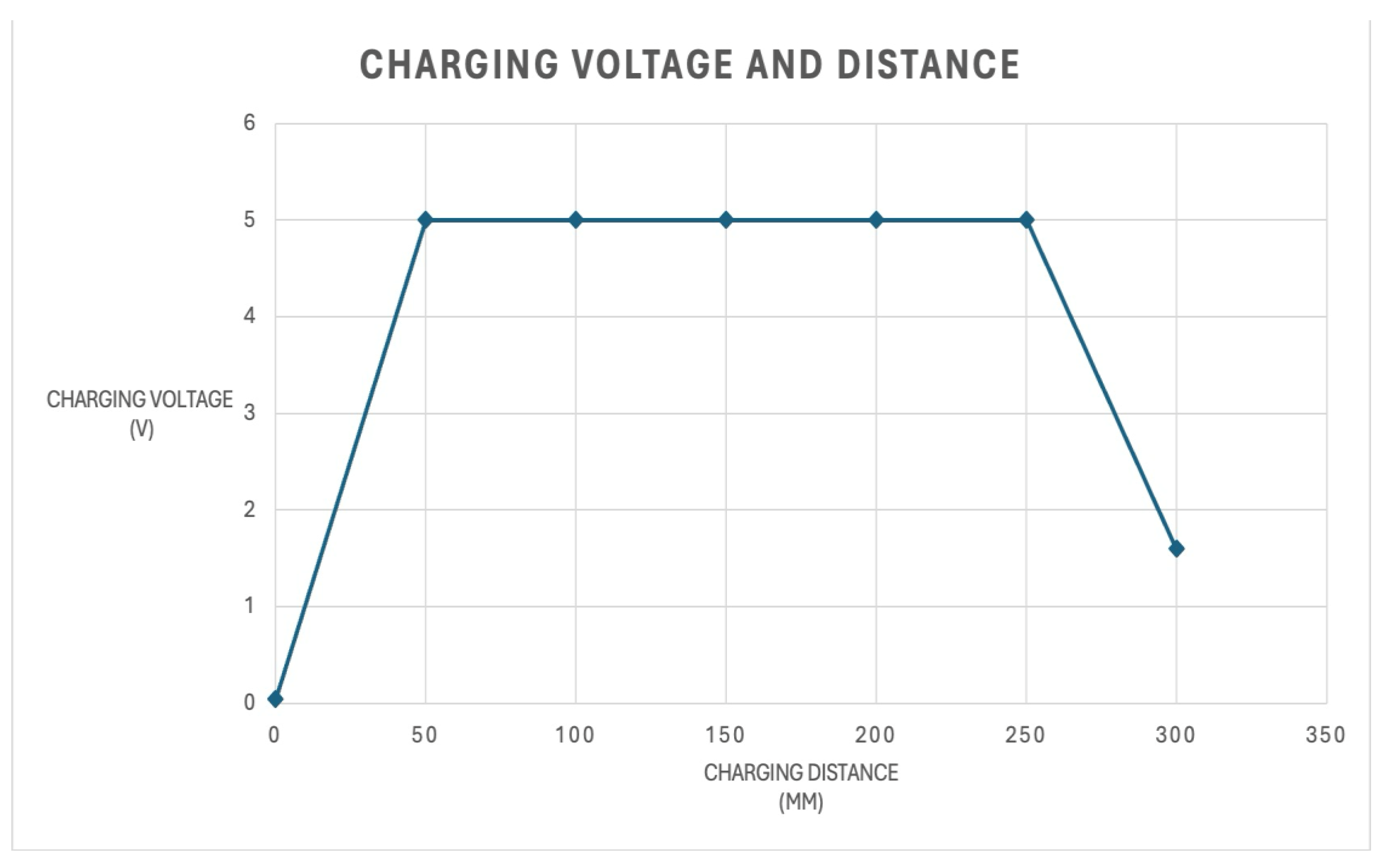

2.3. Resonant Wireless Power Transfer System

To enable autonomous, long-term monitoring, the system employs a magnetic resonance wireless charging link. Unlike inductive charging, which requires precise coil alignment and proximity (<5 mm), resonant WPT utilizes tuned LC circuits to facilitate efficient energy transfer over greater distances and with higher spatial tolerance(13).

The primary transmission station pads are placed underneath the glass container for the rat. The glass is only 1 cm thick, which is below the 2.5 cm maximum that the transmitters are rated for. The receiver is a flexible coil placed underneath the rat's belly and attached to the 3D-printed enclosure. That coil is then connected to the lithium-polymer (LiPO) battery. Energy transfer occurs automatically as the subject moves within the charging zone. The resonant link provides sufficient current to power the ESP32-S3 and its sensors while simultaneously trickle-charging the LiPo battery. The low-power nature of the resonant field ensures no significant thermal increase at the receiver coil, maintaining animal comfort.

The system operates within the 115–150 kHz range. This low-frequency resonant band helps to ensure high penetration through the non-conductive materials of the laboratory container (e.g., glass or wood) while remaining below the frequency bands that might introduce noise into the BioAmp EXG’s biopotential recordings.

Figure 3.

Charging distance and voltage with the resonant wireless charger.

Figure 3.

Charging distance and voltage with the resonant wireless charger.

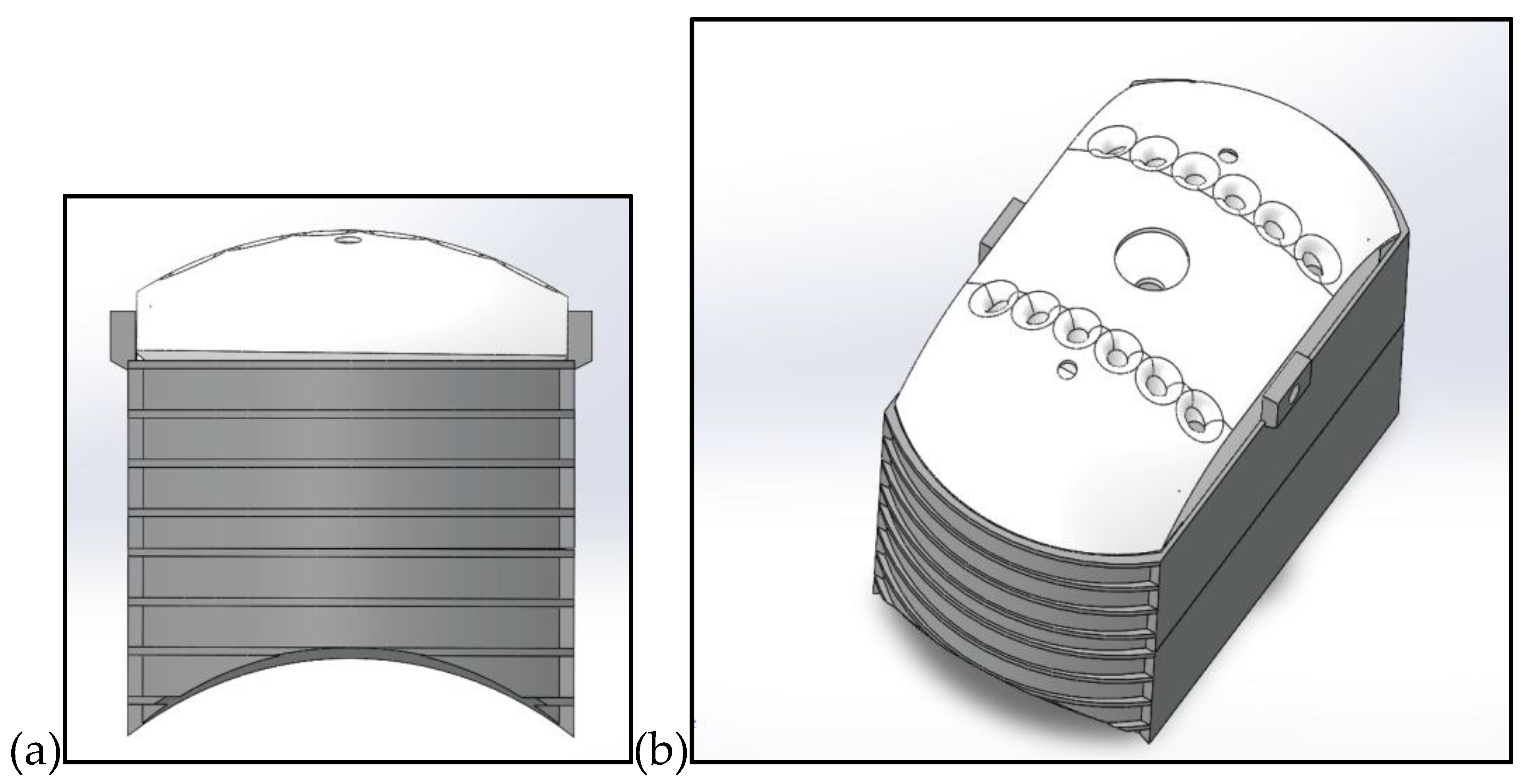

2.4. 3D Printed Case

To maintain the high-performance requirements of the telemetry system while ensuring the comfort of the subject, the device is housed in a custom-designed, 3D-printed enclosure. The case is fabricated using high-resolution resin (SLA), optimized for a minimal mass-to-volume ratio to ensure the total weight remains below the threshold for behavioral interference in rats(14).

Figure 4.

(a) front view of the fully connect case, with a curved bottom to fit on the back of the rat. (b) The top view of the model.

Figure 4.

(a) front view of the fully connect case, with a curved bottom to fit on the back of the rat. (b) The top view of the model.

2.5. Sensors Outside the Wearable

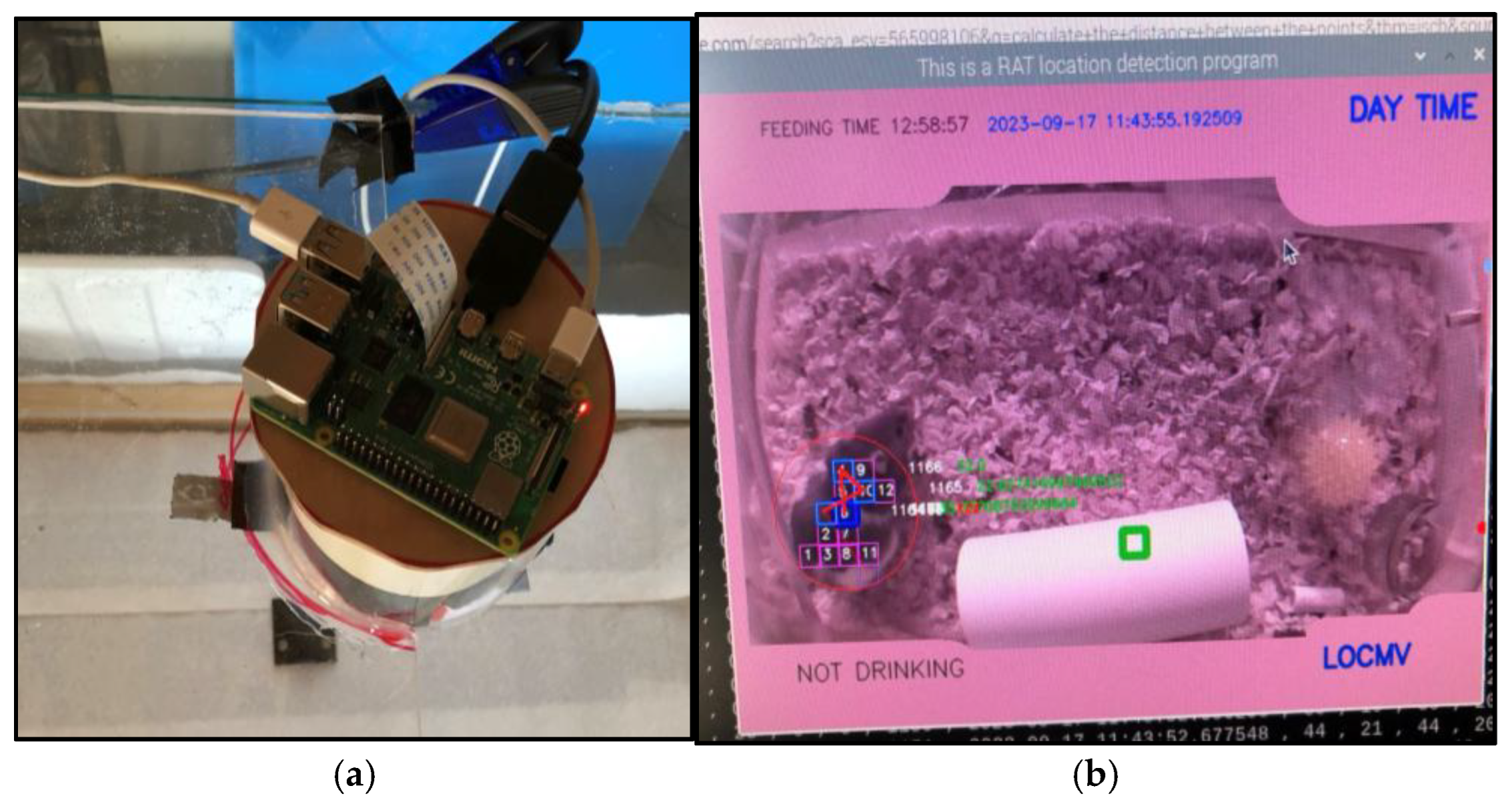

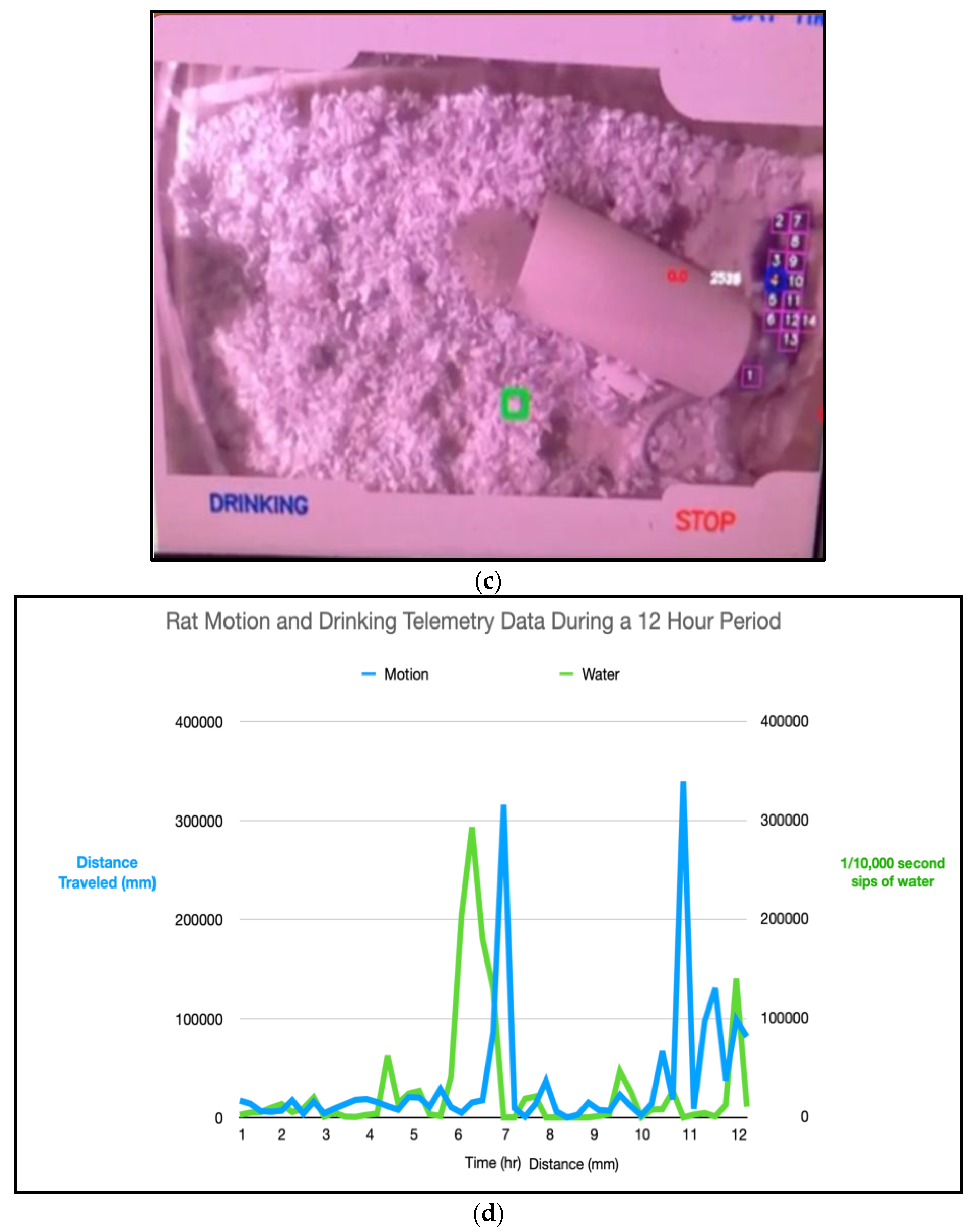

To provide contextual validation for the wearable sensor data, the laboratory container is monitored by an overhead Raspberry Pi 3 vision system. Utilizing a camera module and a custom computer vision pipeline, the system performs real-time object detection and centroid tracking of the subject.

This vision layer serves two primary functions:

Behavioral Annotation: It automatically classifies macro-behaviors, such as drinking, feeding, moving, or resting, by correlating the rat’s position with the integrated food and water trackers.

IMU Validation: The visual trajectory data provides a spatial ground truth for the 6-axis ISM330DHCX IMU readings, allowing for the precise calibration of locomotion and gait analysis algorithms.

The Raspberry Pi acts as the central base station, synchronizing the visual "action" timestamps with the compressed physiological data packets received via BLE, creating a unified, multi-modal dataset of the subject's status.

Figure 5.

(a) Cage setup, Raspberry PI with pi camera tracking the rat in its glass cage. (b) Camera feed with the vision model classifying that the rat is not drinking water and LOCMV and it is in motion. (c) rat is drinking water and not moving. (d) graph of the rat telemetry data.

Figure 5.

(a) Cage setup, Raspberry PI with pi camera tracking the rat in its glass cage. (b) Camera feed with the vision model classifying that the rat is not drinking water and LOCMV and it is in motion. (c) rat is drinking water and not moving. (d) graph of the rat telemetry data.

2.6. Temporal Alignment and Frame Structure

All sensor data is grouped into fixed-duration frames of one second. Each frame contains a complete set of high-rate samples and optional low-rate measurements when available. A timestamp, expressed in milliseconds since system boot, is associated with each frame.

This framing approach ensures that all signals within a frame correspond to the same time interval. It also simplifies both compression and reconstruction, as the number of samples per frame is known in advance.

2.7. Lossless Compression Pipeline

2.7.1. Motivation for Signal-Aware Compression

Generic compression algorithms operate on byte streams and do not consider the physical meaning of the data. When applied directly to raw biosignals, their performance is limited because the binary representation of successive samples does not exhibit sufficient repetition.

Physiological signals, however, evolve smoothly over time. By exploiting this property through preprocessing, it is possible to transform the data into a representation that is more suitable for dictionary-based compression while preserving exact reconstruction.

2.7.2. Linear Prediction

Linear prediction is used to reduce redundancy in time-series signals by estimating the current sample based on previous samples. Physiological signals such as ECG and IMU data change gradually due to physical and biological constraints. Because of this, consecutive samples tend to follow a locally linear trend.

Instead of compressing the original samples directly, the system compresses the prediction error, also called the residual. These residuals have much smaller amplitude than the original signal, which improves later compression stages.

A second-order predictor is used because it models both the signal level and its local slope.

Mathematical Formulation

Let x[i] be the original signal sample at index i.

The predicted value is computed as:

For the first two samples, prediction is not possible. These samples are stored directly:

Reversion (Signal Reconstruction)

To reconstruct the original signal, the inverse operation is applied:

Since all operations are integer-based and deterministic, reconstruction is exact.

2.7.3. Signed Residual Representation Issues

After prediction, the residuals r[i] are signed integers. Small residual values occur frequently, especially around zero. However, signed integers are represented using two’s complement encoding.

In two’s complement:

This creates large binary differences between small positive and small negative values, even though their numeric difference is minimal.

Although the magnitude difference is 2, the binary difference spans almost all bits. This causes abrupt changes in the most significant byte.

Dictionary-based compressors operate on byte sequences. Frequent changes between 0x00 and 0xFF in the high byte reduce repetition and pattern matching. This significantly degrades compression performance if the signed representation is used directly.

2.7.4. ZigZag Encoding

ZigZag(15) encoding remaps signed integers to unsigned integers so that values with small magnitude remain numerically small, regardless of sign. This removes sign extension from the most significant bits and produces smoother byte patterns.

Positive and negative values are interleaved in increasing order of magnitude.

The mapping process is executed by calculating for each element:

Inverse ZigZag Decoding

To recover the signed residual:

This operation restores the original signed value exactly.

2.7.5. Byte Packing

After ZigZag encoding, each value is stored as a 16-bit unsigned integer. To prepare the data for dictionary compression, each value is split into two bytes:

The pair of 8-bit values can be reconstructed as a single 16-bit value by the operation:

This step reveals repeated patterns in the high-order byte, which is often zero for small values. It also increases similarity between adjacent bytes.

2.7.6. Dictionary Compression Using TAMP

Tamp is a lossless compression library designed for embedded and resource-constrained systems by applying a simplified version of traditional dictionary-based compression. At its core, Tamp uses(7)(8)a modified LZSS algorithm (a derivative of LZ77), which scans the input data for repeated sequences and replaces them with references to earlier occurrences. When a match longer than a minimum threshold is found in a sliding window (a ring buffer of recently seen bytes), Tamp emits a token indicating the match length and offset; when no useful match exists, it emits a literal byte instead. This approach reduces redundancy by reusing repeated patterns rather than storing them again.

After identifying matches or literals, the algorithm packs the output into a tight bit stream, using a fixed, predefined Huffman coding for the lengths of matched sequences to make common lengths use fewer bits. A small header at the start of the compressed stream encodes key parameters like the window size and literal bit width, which the decompressor uses to interpret the rest of the data. Because the Huffman codes are static and the implementation avoids dynamic tables, Tamp’s compressor and decompressor remain very compact and low-memory, making it suitable for microcontrollers and similar systems where full DEFLATE or zlib would be too heavy.

It uses a sliding window of 1024 bytes and processes data at the byte level.

All compression buffers are statically allocated. The compressor does not perform memory allocation during runtime, which improves stability during long-term operation.

2.7.7. Packet Construction

Compressed ECG and IMU data are assembled into a single composite packet per frame. Low-frequency signals are appended only when new measurements are available.

This packet structure ensures that all high-rate signals remain synchronized. It also reduces BLE protocol overhead by avoiding multiple characteristics and repeated headers.

2.8. Bluetooth Low Energy Transmission

The ESP32-S3 operates as a BLE GATT server using the NimBLE stack. A single service exposes one characteristic that carries the composite biosignal packet. The maximum transmission unit is set to 512 bytes(18).

Connection parameters are selected to prioritize throughput and minimize latency. The connection interval is kept short, and slave latency is set to zero.

Reliable Transmission Using Indications

Data is transmitted using BLE indications(16). Each packet must be acknowledged by the client before the next packet is sent. This ensures reliable delivery at the application level(17).

Although indications introduce additional delay compared to unacknowledged transmission, the achieved throughput remains sufficient for the compressed data rate.

2.9. Parallel SD Card Logging

All acquired data is written to an SD card independently of BLE transmission. SD logging is treated as mandatory, while BLE transmission is treated as best-effort.

This separation ensures that temporary wireless disruptions do not result in data loss.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Validation of the Compression–Decompression Pipeline

The complete compression and decompression pipeline was evaluated through an extended stress test composed of 10,000 consecutive iterations. Each iteration processed a full ECG block containing 2000 samples acquired at 2000 Hz, corresponding to 4000 bytes of raw data per block.

All 10,000 tests completed successfully, resulting in a 100% success rate. No compression errors, decompression errors, or verification mismatches were observed. Every decompressed block matched the original input sample-by-sample, confirming that the pipeline operates in a strictly lossless manner.

This result is particularly relevant for embedded systems intended for long-term operation. It demonstrates that the pipeline maintains internal consistency over time and that the design choice to avoid runtime memory allocation prevented memory fragmentation and watchdog resets during extended execution.

3.2. Compression Performance and Timing Behavior

3.2.1. Compression Time

The average compression time per ECG block was approximately 145.6 ms, with very low dispersion:

This narrow distribution indicates highly predictable execution. The small standard deviation relative to the mean shows that compression time is largely insensitive to variations in signal content, including motion artifacts and amplitude changes.

Given that each block represents one second of data, the compression stage comfortably fits within the real-time constraint, leaving sufficient margin for additional tasks such as sensor acquisition, SD logging, and BLE packet assembly.

3.2.2. Decompression Time

Decompression performance was significantly faster:

This behavior aligns with the characteristics of dictionary-based compression schemes, where encoding is computationally heavier than decoding. The very small variance confirms that decompression cost is almost entirely data-independent, which simplifies receiver-side scheduling.

3.3. Compression Ratio and Data Reduction

Each raw ECG block consisted of 4000 bytes. After prediction, ZigZag encoding, byte splitting, and dictionary compression, the mean compressed size was approximately 2680 bytes, corresponding to a compression ratio of 1.49×.

This reduction was achieved without any loss of information and remained stable across all test iterations. The result confirms that the preprocessing stages successfully transformed the signal into a representation with high byte-level repetition, allowing the dictionary compressor to operate efficiently.

It is important to note that no entropy coding was applied beyond the dictionary compressor. The observed reduction is therefore attributable primarily to signal-aware preprocessing rather than aggressive statistical modeling.

3.4. Impact of Linear Prediction and Residual Processing

Linear prediction reduced the dynamic range of the ECG signal by modeling temporal continuity between adjacent samples. Instead of encoding absolute amplitudes, the compressor processed residual values that were small and centered near zero.

However, residuals alone were not sufficient to achieve effective compression. Signed integer representation introduced frequent sign-extension patterns in the most significant byte, which limited similarity between adjacent byte sequences.

ZigZag encoding resolved this issue by mapping signed residuals to unsigned values in a monotonic order of magnitude. After this transformation, both positive and negative residuals of similar size produced similar binary patterns. This directly increased repetition in the byte stream, especially in the most significant byte.

The subsequent step of splitting each 16-bit value into two 8-bit values exposed this repetition explicitly to the dictionary compressor. As a result, long runs of identical high-order bytes became common, which explains the consistent compression ratio observed throughout testing.

3.5. System Throughput and BLE Transmission Results

The compressed biosignal stream was transmitted over Bluetooth Low Energy using indication-based communication. Long-duration runtime statistics collected over approximately 300 minutes confirm stable operation with a total average data rate of 12.86 kbps.

Each high-frequency signal maintained an effective update rate close to 1 packet per second, matching the framing strategy used during packet construction.

No packet loss was detected, and all received packets were decoded correctly. The use of indications ensured that each transmission was acknowledged before the next packet was sent, preventing silent data drops.

Synchronization and Packet Integrity

The composite packet structure ensured that ECG, acceleration, and gyroscope data remained temporally aligned. All signals within a packet corresponded to the same acquisition window, eliminating inter-signal drift.

This design also simplified client-side processing. Each received packet represented a complete and self-contained data unit, allowing direct reconstruction without reordering or cross-stream buffering.

The measured throughput confirms that this approach remains well within the practical limits of BLE when combined with a large MTU and short connection interval.

3.6. Parallel SD Logging and Reliability Guarantees

Throughout all tests, data was written to the SD card in parallel with BLE transmission. This separation of responsibilities proved effective: wireless transmission was treated as opportunistic, while storage was treated as mandatory.

Even during extended runs, no interference was observed between compression, SD writing, and BLE transmission. This confirms that the system architecture successfully isolates time-critical paths from best-effort communication tasks.

4. Conclusions

The work presented in this study evaluated a complete embedded biosignal acquisition, compression, storage, and wireless transmission pipeline implemented on an ESP32-S3 platform. The system was designed to operate continuously under strict timing and reliability constraints, combining high-rate physiological signals with lower-rate contextual measurements. Through extensive testing under sustained runtime conditions, the proposed architecture was assessed with respect to correctness, timing behavior, compression efficiency, and wireless delivery reliability. The results obtained allow a clear assessment of whether the proposed design choices meet the practical requirements of long-term biosignal monitoring on resource-limited hardware.

Although raw compression speed expressed in kilobytes per second appears low when measured in isolation, this metric is not representative of system performance. Compression operates on fixed-size, once-per-second blocks and completes well within the available time budget.

Decompression speed, on the other hand, greatly exceeds the incoming data rate, ensuring that the receiver never becomes a bottleneck.

The overall system therefore, satisfies real-time constraints despite operating on a resource-limited embedded platform.

The experimental results confirm that:

The compression–decompression pipeline is fully deterministic and lossless

Execution time remains stable over long runtimes

Signal-aware preprocessing is responsible for the majority of compression gains

BLE transmission using indications sustains the required throughput without loss

Parallel SD logging provides a reliable fallback for long-term data capture

These findings support the suitability of the proposed approach for continuous biosignal monitoring applications where timing, reliability, and data integrity are critical.

Acknowledgments

This study is dedicated to the memory of Judy Campisi and we would also like to thank Brian Wang, Bárbara M. Quintela, and Nuno R. B. Martins for their valuable help and support.

References

- Morton, D. B.; et al. Refinements in telemetry procedures. In Laboratory Animals; BVAAWF/FRAME/RSPCA/UFAW Joint Working Group on Refinement, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, A. N.; et al. Timecourse of recovery after surgical intraperitoneal implantation of radiotelemetry transmitters in rats. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods 2007, 56(2), 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Pre-Implanted Animal Services; Data Sciences International (DSI), 2025.

- Bakker, J.; et al. Recovery time after intra-abdominal transmitter placement for telemetric (neuro) physiological measurement in freely moving common marmosets (Callitrix jacchus). Animal Biotelemetry 2(10) 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, L. R; et al. Biotelemetry transmitter implantation in rodents: impact on growth and circadian rhythms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2004, 286, R967–R974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Mulders, J.; et al. Wireless Power Transfer: Systems, Circuits, Standards, and Use Cases. Sensors (Basel) 2022, 22(15), 5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamp. 2025. Available online: https://tamp.readthedocs.io/en/latest/.

- Pugh, Brian. Tamp GitHub

. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/BrianPugh/tamp?utm.

- Cesarovic, N.; et al. Implantation of Radiotelemetry Transmitters Yielding Data on ECG, Heart Rate, Core Body Temperature and Activity in Free-moving Laboratory Mice. J Vis Exp 2011, (57), 3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vincentiis, S.; et al. 3D-printed weight holders design and testing in mouse models of spinal cord injury. Front Drug Deliv. 4 2024, 1397056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espressif Systems. 2025. Available online: https://www.espressif.com/en/products/socs/esp32-s3?

- Espressif Systems. ESP32 S3 Series: Datasheet. 2022.

- Mou, et al. Survey on magnetic resonant coupling wireless power transfer technology for electric vehicle charging. IET Power Electronics 2019, 12(12), 3005–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. P.; et al. Animal lifestyle affects acceptable mass limits for attached tags. Proc Biol Sci 2021, 288, 20212005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GitHub pages Protocol Buffers encoding documentation. 2025.

- Bluetooth Core Specifications. Part F: Attribute Protocol (ATT). Available online: https://www.bluetooth.com/wp-content/uploads/Files/Specification/HTML/Core-60/out/en/host/attribute-protocol.

- Bluetooth Core Specifications. Part G: Generic Attribute Profile (GATT). Available online: https://www.bluetooth.com/wp-content/uploads/Files/Specification/HTML/Core-54/out/en/host/generic-attribute-profile.

- Espressif Systems. Configurations Options Reference. 2016-2025. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).