1. Introduction

Fabry disease (FD; OMIM 301500) is a rare X-linked lysosomal storage disease caused by deleterious variants in

GLA (NCBI, GRCh37.p13, NC_000023.10), which encodes the enzyme alpha-galactosidase A (α-Gal A; EC 3.2.1.22)[

1]. This leads to accumulation of its substrate, globotriaosylceramide (Gb3), its deacylated metabolite globotriaosylsphingosine (lyso-Gb3), and related analogs[

1,

2]. Progressive accumulation of Gb3 and lyso-Gb3 within lysosomes across a variety of cell types and organs disrupts cellular dysfunction, leading to serious complications such as renal failure, heart failure, and stroke, and ultimately reduces life expectancy[

3,

4].

While α-Gal A activity testing alone is sufficient to diagnose FD in males, it is necessary to identify a disease-causing mutation in

GLA in females, who typically exhibit normal or highly variable plasma α-Gal A activity due to skewed X chromosome inactivation[

5]. Routine methods for

GLA genotyping include real-time PCR[

6], multiplex PCR[

7], Sanger sequencing [

8,

9], next-generation sequencing (NGS)[

9,

10], and multiple ligation-dependent probe amplification[

11], which collectively identify pathogenic variants in over 96% of FD cases[

12]. To date, over 1,000 variants of

GLA have been registered in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) Professional[

13,

14]. These include missense mutations (58.5%), nonsense mutations (16.5%), deletions (13.0%), splicing defects (10.5%); insertions (1.0%), and insertion-deletion (indel) (0.5%) [

12]. With advances in gene mutation-detection technologies, previously undetectable intronic variants are increasingly being recognized. Compared with Sanger sequencing, long-read sequencing (LRS) offers superior detection of almost all types of mutations, including deep intronic variants[

15].

In 2002, Ishii et al. uncovered IVS4+919G > A, a variant that lies deep within intron 4 of

GLA and causes aberrant splicing of

GLA mRNA[

16]. Since then, intronic variants have emerged as important contributors to the mutational spectrum of FD. In this study, we report two novel deep intronic

GLA variants identified by LRS in two unrelated male FD patients. These variants were not detected by classical Sanger sequencing. Bioinformatic analyses supported the pathogenic potential of both variants. These findings highlight the value of LRS in expanding molecular diagnostics when conventional approaches fall short.

2. Case Description

Both presented with clinical, enzymatic, and pathological features suggestive of FD, but Sanger sequencing targeting

GLA exons and exon boundaries (National Center for Biotechnology Information reference sequence NM_000169.3) failed to detect pathogenic variants[

17]. For further precise the identification and validation of the possible inversion, we performed

GLA LRS, RNA Sequencing and quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) (Supplementary File S1). Patient data were obtained through retrospective clinical review, and α-Gal A activity and lyso-Gb3 levels were determined using dried blood spot samples.

2.1. Patient 1

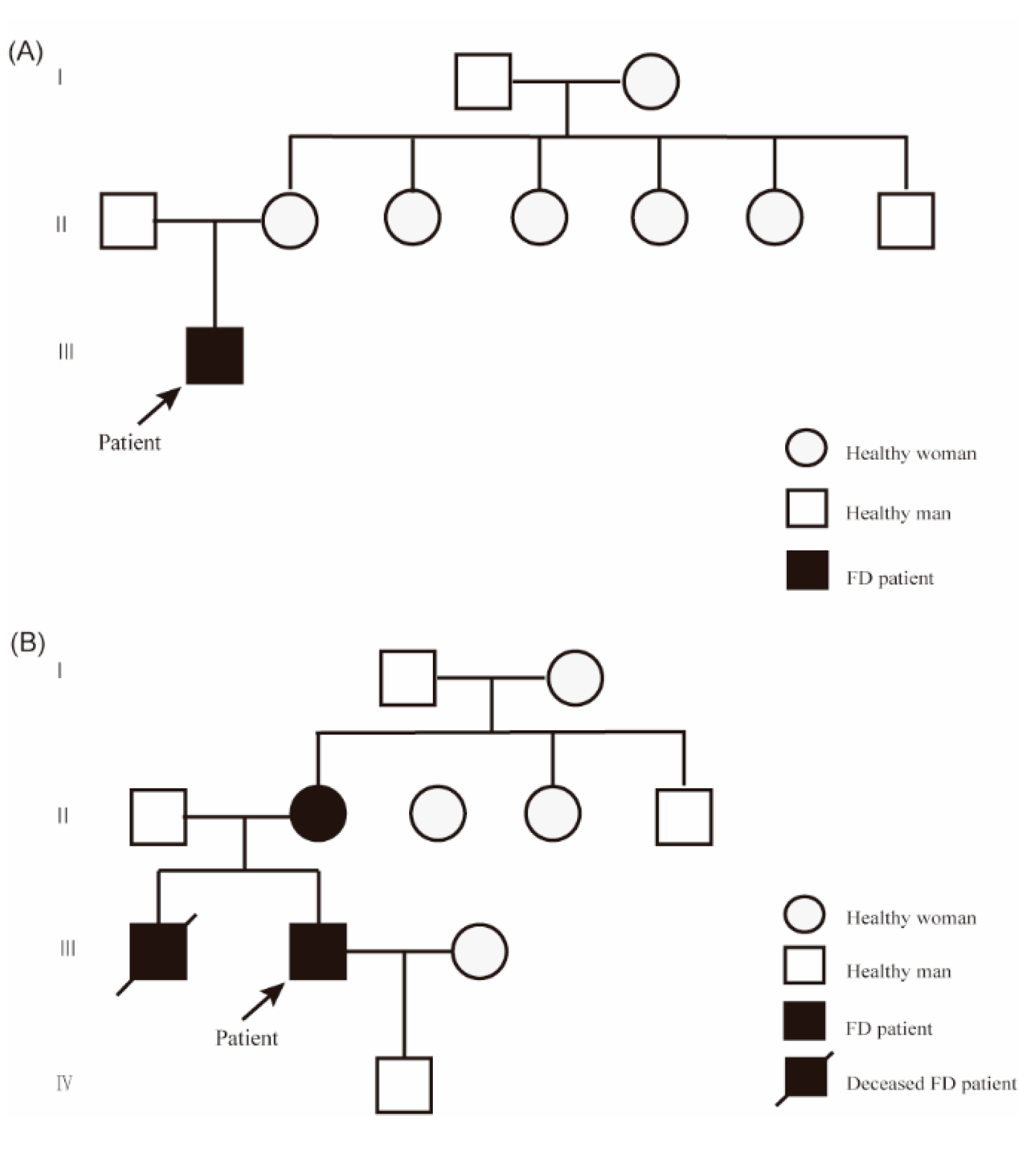

Patient 1, a 20-year-old Han Chinese man, presented with hypohidrosis and unexplained acroparesthesia since childhood, triggered by physical exertion, heat, or emotional stress. Additional symptoms included memory decline, occasional palpitations, dizziness, intermittent tinnitus, fatigue, and reduced exercise tolerance. The patient had undergone intussusception surgery at 8 months of age. Family history was negative for FD (

Figure 1A). Renal, heart, and brain assessments were unremarkable. Biochemical testing revealed markedly reduced α-Gal A enzyme activity in leukocytes (0.64 µmol/L/h; reference range: 2.40–17.65) and elevated plasma lyso-Gb3 levels (19.84 ng/mL; reference: < 1.11). Skin biopsy showed myeloid bodies in epithelial cells of sweat glands, consistent with FD (

Figure 2). Sanger sequencing did not detect pathogenic

GLA variants.

LRS identified a ~1.7-kb insertion within intron 4 of

GLA, located between g.100654565 and g.100654566 (NC_000023.10). The insertion corresponded to part of a long interspersed nuclear element-1 (LINE-1), annotated using the RepeatMasker web server under default settings (

https://www.repeatmasker.org/cgi-bin/WEBRepeatMasker). A 16-bp non-tandem duplication from intron 4 was present at both ends of the insertion. According to Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature[

18], this variant is described as NC_000023.10: g.[100654565_100654566ins1.7kb;100654550_100654565dup] (

Figure 3A, B; see Supplementary File S2 for the insert sequence). Sanger sequencing confirmed 5′ and 3′ breakpoints (

Figure 3C, D), and maternal testing was negative for the insertion.

RNA-seq of the case patient revealed two aberrant

GLA transcripts: one exhibited exon 5 skipping (NM_000169.3:r.640_801del), resulting in an in-frame deletion; the other showed intron 3 retention (NM_000169.3:r.547_548ins547+1_547+89), introducing a premature termination codon (NP_000160.1:p.Gly183fsTer28;

Figure 3A). The latter transcript was predicted to undergo nonsense-mediated decay.

Splicing analysis of the 1.7-kb insert using the Human Splicing Finder (HSF) web tool (

https://hsf.genomnis.com) identified 152 splicing signals, including 85 acceptor and 67 donor splice sites, 1,134 exonic splicing silencer (ESS) sites, 987 exonic splicing enhancer (ESE) sites, and 74 branch point sequences (BPSs). The exonic splicing regulatory (ESR) ratio, calculated as the number of ESEs divided by the number of ESSs, was < 1 (1,134/987) (

Figure 3E).

2.2. Patient 2

Patient 2, a 37-year-old Han Chinese man, presented with acroparesthesia and hypohidrosis starting at the age of 8 years. His medical history included hypertension, nephrotic syndrome, and a positive family history of FD. He underwent dialysis for 4 years prior to undergoing a kidney transplant at age 35. During the course of his illness, he also experienced tinnitus, hearing loss, palpitations, and diarrhea. Echocardiography showed left ventricular hypertrophy (left ventricular posterior wall thickness: 1.6 cm). Lab results revealed reduced α-Gal A activity (0.49 µmol/L/h), and elevated lyso-Gb3 levels (52.01 ng/mL). His older brother developed similar symptoms at age 8 and had a history of hypertension, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and lacunar infarction; he died after initiating dialysis at age 33. The patient’s 56-year-old mother reported burning sensations in her feet beginning at age 8, which disappeared after childbirth. The patient is currently receiving enzyme replacement therapy (

Figure 1B).

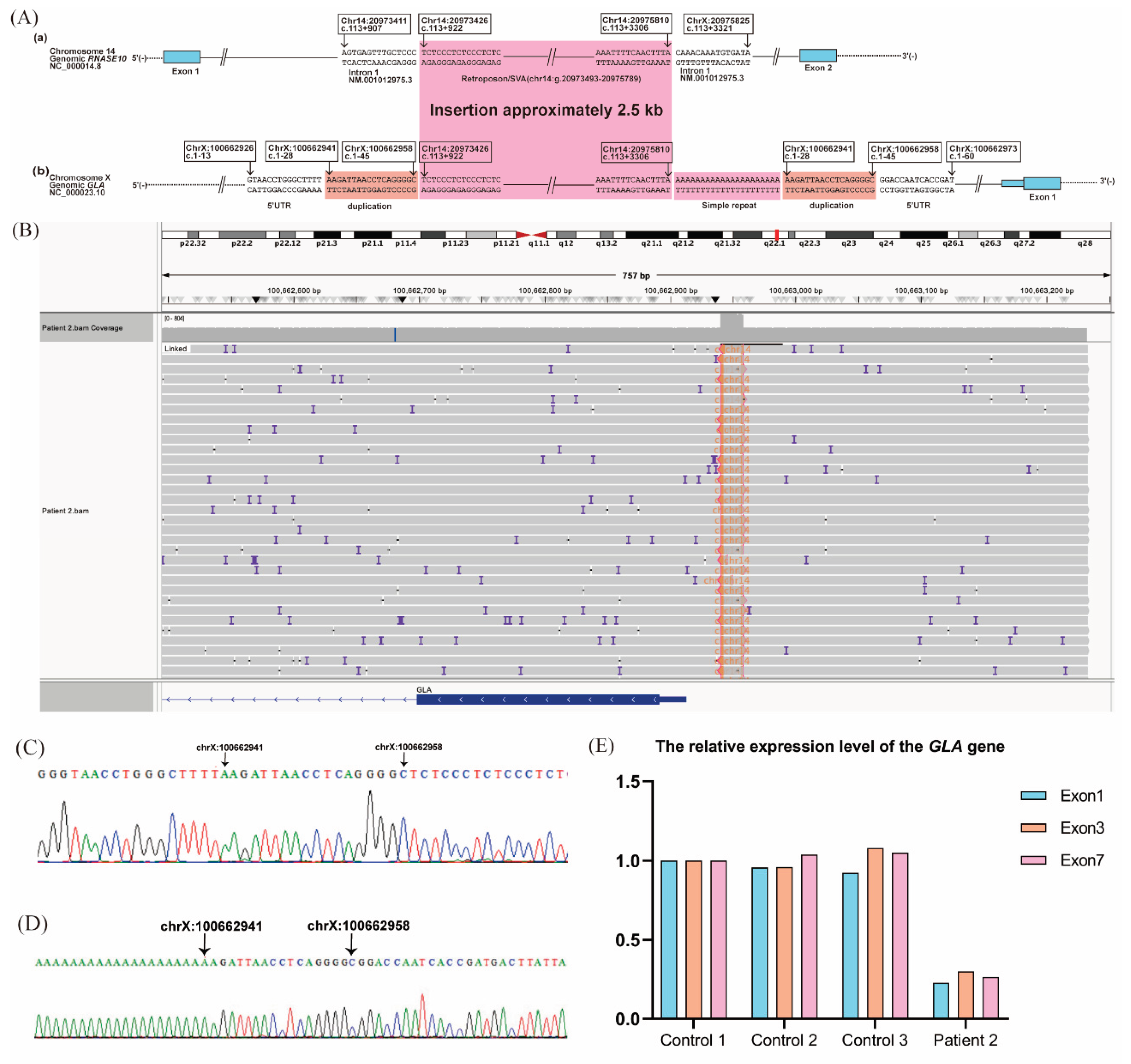

LRS identified a 2.5-kb insertion within the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) located between g.100662958 and g.100662959, along with a 21-adenine nucleotide duplication and an 18-bp duplication (g.100662941_100662958) downstream of the insertion. RepeatMasker annotated the inserted sequence as part of a SINE-VNTR-Alu (SVA) retroposon element. Homology analysis using BLAST revealed similarity between the insertion sequence and a deep intronic region of

RNASE10 intron 1 (GRCh37 chr14:g.20973426-20975810). This variant is described as NC_000023.10: g.[100662958_100662959ins2.5kb;G [

21];100662941_100662958dup] (

Figure 4A–D). Sanger sequencing confirmed the variants.

Unlike Patient 1, RNA-seq did not detect aberrant

GLA transcripts. However, RT-qPCR analysis showed reduced expression of exons 1, 3, and 7 in normal

GLA transcripts compared with healthy controls (

Figure 4E).

3. Discussion

We report two novel non-coding

GLA variants in two unrelated male patients with FD, including a 1.7-kb LINE-1 insertion within intron 4 associated with abnormal splicing, and a 2.5-kb insertion in the 5′-UTR homologous to

RNASE10 intron 1 linked to reduced expression of normal transcripts. Although NGS, which enables analysis of numerous genes and detection of complex variants, has been successfully used in FD diagnosis, deep intronic variants may still be missed because of limitations in exon-focused panels. LRS can identify complex genetic variants, including deep intronic variants and structural rearrangements, complementing routine diagnostic methods. In a cohort study of 207 Japanese patients with FD, seven (3.4%) had no pathogenic variants detected in the exonic regions or exon–intron boundaries of

GLA using standard gene analysis[

12]. In a study by Nowak et al., two of 12 patients showed no pathogenic variants on Sanger sequencing. Multiple amplicon sequencing subsequently identified a deep intronic variant (c.547+404T>G) in one patient, while mRNA and cDNA sequencing showed an exon 2 deletion in the other[

19]. In a 2024 cohort of 82 FD patients, Yao et al. reported three deep intronic variants identified by long-range PCR coupled with LRS that had been missed by Sanger sequencing[

15]. Similarly, our study uncovered two insertional variants, one in intron 4 and the other in the 5′-UTR region of

GLA, in FD patients who previously tested negative by conventional sequencing. Based on clinical symptoms, α-Gal A activity, and lyso-Gb3 levels, these two patients were classified as having non-classic and classic FD, respectively[

17].

Located more than 100 bp away from exon–intron boundaries, these deep intronic variants can affect ESEs or ESSs, potentially causing misregulated splicing[

20]. Splicing of pre-mRNAs removes introns and joins exons to form mature mRNA transcripts for translation. This process is guided by signals such as splice sites, BPSs, and regulatory elements, including ESEs and ESSs, which promote or inhibit the inclusion of coding segments in the final mRNA[

21,

22,

23,

24]. The prevalent c.639+919G >A mutation disrupts the binding of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1/A2 to an ESS, causing pseudoexon activation and FD[

25]. In our Patient 1, the ESR ratio was < 1, suggesting a predominance of splicing silencers over enhancers, which may contribute to exon skipping or impaired exon recognition during pre-mRNA splicing.

LINE-1 elements can drive inherited diseases through various mechanisms, including de novo LINE-1 insertions, insertion-mediated deletions, and genomic rearrangements[

26]. Wimmer et al.[

27] reported a patient with a LINE-1 insertion in intron 9 of the

NF1 gene, resulting in the skipping of the preceding exon and exonization of a short portion of the LINE-1 sequence. Alesi et al.[

28] described two siblings affected by neurofibromatosis type 1, in whom insertion of a 5′-truncated inverted LINE-1 element into intron 15 led to skipping of the upstream exon and generation of an alternative transcript lacking exon 15. Similarly, our Patient 1 was found to harbor a ~1.7-kb insertion derived from a LINE-1 element, predicted to disrupt normal splicing and result in aberrant transcription.

The 5′- and 3′-UTRs are critical for post-transcriptional gene regulation, influencing processes such as mRNA processing, stability, and translation initiation[

29]. The 5′-UTR, plays a particularly important role in ribosome recruitment and translation efficiency, impacting cellular proteome expression[

30,

31]. Variants in the 5′-UTR have been shown to impair translation and lead to disease, as exemplified by the heterozygous deletion of

MEN1[

32] and point mutation of

FGF13[

33]. SVA insertions can affect gene expression through mechanisms such as exon trapping and alternative splicing, potentially leading to truncated proteins[

34]. Pathogenic SVA insertions have been implicated in various diseases, including X-linked dystonia-parkinsonism (XDP), breast cancer, Fukuyama muscular dystrophy, and Batten disease[

34]. XDP cell models exhibit multiple transcriptional abnormalities surrounding the exons flanking the SVA insertion, including aberrant alternative splicing, partial intron retention, decreased transcription of exons, and decreased levels of the full-length

TAF1 mRNA[

35]. In our Patient 2, we identified an SVA insertion within the

GLA 5′-UTR that resulted in reduced gene expression. This discovery represents a crucial step toward understanding the molecular mechanisms by which retrotransposons contribute to FD pathogenesis, a phenomenon not previously reported.

4. Conclusions

Our study broadens the known genetic spectrum of GLA variants and provides further insight into the molecular basis of FD. When conventional Sanger sequencing fails to detect pathogenic variants, LRS should be considered. Integrating LRS into the diagnostic workflow ensures a more comprehensive approach, reducing the risk of missing clinically relevant variants in cases with negative results from conventional testing.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary file S1: title; Supplementary file S2: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, YjY, CL, ZxW, YY, ZyX, and WZ; methodology, YjY, XyZ, YwZ, YM, ZyX, and WZ; software, YjY and ZyX; investigation, YjY, XyZ, YwZ, YM, ZyX, and WZ; data curation, YjY, XyZ, YwZ, YM, ZyX, and WZ; writing—original draft preparation, YjY; writing—review and editing, YjY, XyZ, CL, YwZ, YM, ZxW, YY, ZyX, and WZ; visualization, YjY and ZyX; supervision, YwZ, ZyX and WZ; All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and revisions.

Funding

This study was supported by the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Multi-center Clinical Research Project of Peking University First Hospital,2022CR62), the Peking University Medicine Seed Fund for Interdisciplinary Research (BMU2021MX016), and the Research Fund for the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Rare Diseases (2024-173).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee at Peking University First Hospital (approval no. 2024-173-002, approved on day-month-year).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the two study patients, who were unrelated males evaluated at Peking University First Hospital in 2023.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We thank Michelle Kahmeyer-Gabbe, PhD, from Liwen Bianji (Edanz) (

www.liwenbianji.cn) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ortiz A, Germain DP, Desnick RJ, Politei J, Mauer M, Burlina A, Eng C, Hopkin RJ, Laney D, Linhart A, et al. Fabry disease revisited: Management and treatment recommendations for adult patients. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. (2018). 123(4): p. 416-427. [CrossRef]

- Pieroni M, Moon JC, Arbustini E, Barriales-Villa R, Camporeale A, Vujkovac AC, Elliott PM, Hagege A, Kuusisto J, Linhart A, et al. Cardiac Involvement in Fabry Disease: JACC Review Topic of the Week. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. (2021). 77(7): p. 922-936. [CrossRef]

- Michaud M, Mauhin W, Belmatoug N, Garnotel R, Bedreddine N, Catros F, Ancellin S, Lidove OGaches F. When and How to Diagnose Fabry Disease in Clinical Pratice. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. (2020). 360(6): p. 641-649. [CrossRef]

- Ter Huurne M, Parker BL, Liu NQ, Qian EL, Vivien C, Karavendzas K, Mills RJ, Saville JT, Abu-Bonsrah D, Wise AF, et al. GLA-modified RNA treatment lowers GB3 levels in iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from Fabry-affected individuals. American Journal of Human Genetics. (2023). 110(9): p. 1600-1605. [CrossRef]

- Tuttolomondo A, Chimenti C, Cianci V, Gallieni M, Lanzillo C, La Russa A, Limongelli G, Mignani R, Olivotto I, Pieruzzi F, et al. Females with Fabry disease: an expert opinion on diagnosis, clinical management, current challenges and unmet needs. Frontiers In Cardiovascular Medicine. (2025). 12: p. 1536114. [CrossRef]

- Filoni C, Caciotti A, Carraresi L, Donati MA, Mignani R, Parini R, Filocamo M, Soliani F, Simi L, Guerrini R, et al. Unbalanced GLA mRNAs ratio quantified by real-time PCR in Fabry patients' fibroblasts results in Fabry disease. European Journal of Human Genetics : EJHG. (2008). 16(11): p. 1311-1317. [CrossRef]

- Kornreich R, Desnick RJ. Fabry disease: detection of gene rearrangements in the human alpha-galactosidase A gene by multiplex PCR amplification. Human Mutation. (1993). 2(2): p. 108-111.

- Schiffmann R, Forni S, Swift C, Brignol N, Wu X, Lockhart DJ, Blankenship D, Wang X, Grayburn PA, Taylor MRG, et al. Risk of death in heart disease is associated with elevated urinary globotriaosylceramide. Journal of the American Heart Association. (2014). 3(1): p. e000394. [CrossRef]

- Schiffmann R, Swift C, McNeill N, Benjamin ER, Castelli JP, Barth J, Sweetman L, Wang XWu X. Low frequency of Fabry disease in patients with common heart disease. Genetics In Medicine : Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. (2018). 20(7): p. 754-759. [CrossRef]

- Farr M, Ferreira S, Al-Dilaimi A, Bögeholz S, Goesmann A, Kalinowski J, Knabbe C, Faber L, Oliveira JPRudolph V. Fabry disease: Detection of Alu-mediated exon duplication by NGS. Molecular and Cellular Probes. (2019). 45: p. 79-83. [CrossRef]

- Georgiou T, Mavrikiou G, Alexandrou A, Spanou-Aristidou E, Savva I, Christodoulides T, Krasia M, Christophidou-Anastasiadou V, Sismani C, Drousiotou A, et al. Novel GLA Deletion in a Cypriot Female Presenting with Cornea Verticillata. Case Reports In Genetics. (2016). 2016: p. 5208312. [CrossRef]

- Sakuraba H, Tsukimura T, Togawa T, Tanaka T, Ohtsuka T, Sato A, Shiga T, Saito SOhno K. Fabry disease in a Japanese population-molecular and biochemical characteristics. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports. (2018). 17: p. 73-79. [CrossRef]

- Domm JM, Wootton SK, Medin JAWest ML. Gene therapy for Fabry disease: Progress, challenges, and outlooks on gene-editing. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. (2021). 134(1-2): p. 117-131. [CrossRef]

- Germain DP, Oliveira JP, Bichet DG, Yoo H-W, Hopkin RJ, Lemay R, Politei J, Wanner C, Wilcox WRWarnock DG. Use of a rare disease registry for establishing phenotypic classification of previously unassigned GLA variants: a consensus classification system by a multispecialty Fabry disease genotype-phenotype workgroup. Journal of Medical Genetics. (2020). 57(8): p. 542-551. [CrossRef]

- Yao F, Hao N, Li D, Zhang W, Zhou J, Qiu Z, Mao A, Meng WLiu J. Long-read sequencing enables comprehensive molecular genetic diagnosis of Fabry disease. Human Genomics. (2024). 18(1): p. 133. [CrossRef]

- Ishii S, Nakao S, Minamikawa-Tachino R, Desnick RJFan J-Q. Alternative splicing in the alpha-galactosidase A gene: increased exon inclusion results in the Fabry cardiac phenotype. American Journal of Human Genetics. (2002). 70(4).

- ChineseFabryDiseaseExpertPanel. Expert consensus for diagnosis and treatment of Fabry disease in China (2021). Chin J Intern Med. (2021). 60(4): p. 321-330. [CrossRef]

- den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR, Hart RK, Greenblatt MS, McGowan-Jordan J, Roux A-F, Smith T, Antonarakis SETaschner PEM. HGVS Recommendations for the Description of Sequence Variants: 2016 Update. Human Mutation. (2016). 37(6): p. 564-569. [CrossRef]

- Nowak A, Murik O, Mann T, Zeevi DAAltarescu G. Detection of single nucleotide and copy number variants in the Fabry disease-associated GLA gene using nanopore sequencing. Scientific Reports. (2021). 11(1): p. 22372. [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Drago R, Custódio NCarmo-Fonseca M. Deep intronic mutations and human disease. Human Genetics. (2017). 136(9): p. 1093-1111. [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother WG, Chasin LA. Human genomic sequences that inhibit splicing. Molecular and Cellular Biology. (2000). 20(18): p. 6816-6825.

- Fairbrother WG, Yeh R-F, Sharp PABurge CB. Predictive identification of exonic splicing enhancers in human genes. Science (New York, N.Y.). (2002). 297(5583): p. 1007-1013.

- Wang Z, Rolish ME, Yeo G, Tung V, Mawson MBurge CB. Systematic identification and analysis of exonic splicing silencers. Cell. (2004). 119(6): p. 831-845.

- Pengelly RJ, Bakhtiar D, Borovská I, Královičová JVořechovský I. Exonic splicing code and protein binding sites for calcium. Nucleic Acids Research. (2022). 50(10): p. 5493-5512. [CrossRef]

- Palhais B, Dembic M, Sabaratnam R, Nielsen KS, Doktor TK, Bruun GHAndresen BS. The prevalent deep intronic c. 639+919 G>A GLA mutation causes pseudoexon activation and Fabry disease by abolishing the binding of hnRNPA1 and hnRNP A2/B1 to a splicing silencer. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. (2016). 119(3): p. 258-269. [CrossRef]

- Xie Z, Liu C, Lu Y, Sun C, Liu Y, Yu M, Shu J, Meng L, Deng J, Zhang W, et al. Exonization of a deep intronic long interspersed nuclear element in Becker muscular dystrophy. Frontiers In Genetics. (2022). 13: p. 979732. [CrossRef]

- Wimmer K, Callens T, Wernstedt AMessiaen L. The NF1 gene contains hotspots for L1 endonuclease-dependent de novo insertion. PLoS Genetics. (2011). 7(11): p. e1002371. [CrossRef]

- Alesi V, Genovese S, Lepri FR, Catino G, Loddo S, Orlando V, Di Tommaso S, Morgia A, Martucci L, Di Donato M, et al. Deep Intronic LINE-1 Insertions in NF1: Expanding the Spectrum of Neurofibromatosis Type 1-Associated Rearrangements. Biomolecules. (2023). 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Schuster SL, Hsieh AC. The Untranslated Regions of mRNAs in Cancer. Trends In Cancer. (2019). 5(4): p. 245-262. [CrossRef]

- Hinnebusch AG, Ivanov IPSonenberg N. Translational control by 5'-untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Science (New York, N.Y.). (2016). 352(6292): p. 1413-1416. [CrossRef]

- Grayeski PJ, Weidmann CA, Kumar J, Lackey L, Mustoe AM, Busan S, Laederach AWeeks KM. Global 5'-UTR RNA structure regulates translation of a SERPINA1 mRNA. Nucleic Acids Research. (2022). 50(17): p. 9689-9704. [CrossRef]

- Kooblall KG, Boon H, Cranston T, Stevenson M, Pagnamenta AT, Rogers A, Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Richardson T, Flanagan DE, Taylor JC, et al. Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (MEN1) 5'UTR Deletion, in MEN1 Family, Decreases Menin Expression. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research : the Official Journal of the American Society For Bone and Mineral Research. (2021). 36(1): p. 100-109. [CrossRef]

- Pan X, Zhao J, Zhou Z, Chen J, Yang Z, Wu Y, Bai M, Jiao Y, Yang Y, Hu X, et al. 5'-UTR SNP of FGF13 causes translational defect and intellectual disability. ELife. (2021). 10. [CrossRef]

- Chu C, Lin EW, Tran A, Jin H, Ho NI, Veit A, Cortes-Ciriano I, Burns KH, Ting DTPark PJ. The landscape of human SVA retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Research. (2023). 51(21): p. 11453-11465. [CrossRef]

- Nicoletto G, Terreri M, Maurizio I, Ruggiero E, Cernilogar FM, Vaine CA, Cottini MV, Shcherbakova I, Penney EB, Gallina I, et al. G-quadruplexes in an SVA retrotransposon cause aberrant TAF1 gene expression in X-linked dystonia parkinsonism. Nucleic Acids Research. (2024). 52(19): p. 11571-11586. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).