1. Introduction

Gait analysis is essential for evaluating human locomotion and identifying abnormalities associated with musculoskeletal, neurological, and age-related conditions. Traditional gait laboratories rely on three-dimensional motion capture systems and force plates to quantify ground reaction forces (GRFs) and temporal gait parameters [

1,

2]. Although considered the clinical gold standard, these systems require specialized facilities, skilled personnel, and significant financial investment, limiting their availability in routine clinical practice and particularly in community or resource-limited settings [

3,

4]. As a result, many patients who could benefit from objective gait assessment—such as older adults, individuals recovering from lower-limb injuries, or those undergoing rehabilitation—lack access to quantitative evaluation tools.

To address these limitations, wearable gait assessment technologies have emerged as promising alternatives, offering the potential for portable, cost-effective, and real-time gait monitoring. Early innovations, such as shoe-integrated wireless sensors, laid the foundation for today’s smart insole systems [

5,

6]. Recent advances have further enabled the integration of wearable systems with mobile and cloud-based platforms, enhancing their applicability for remote monitoring and community-based care [

7].

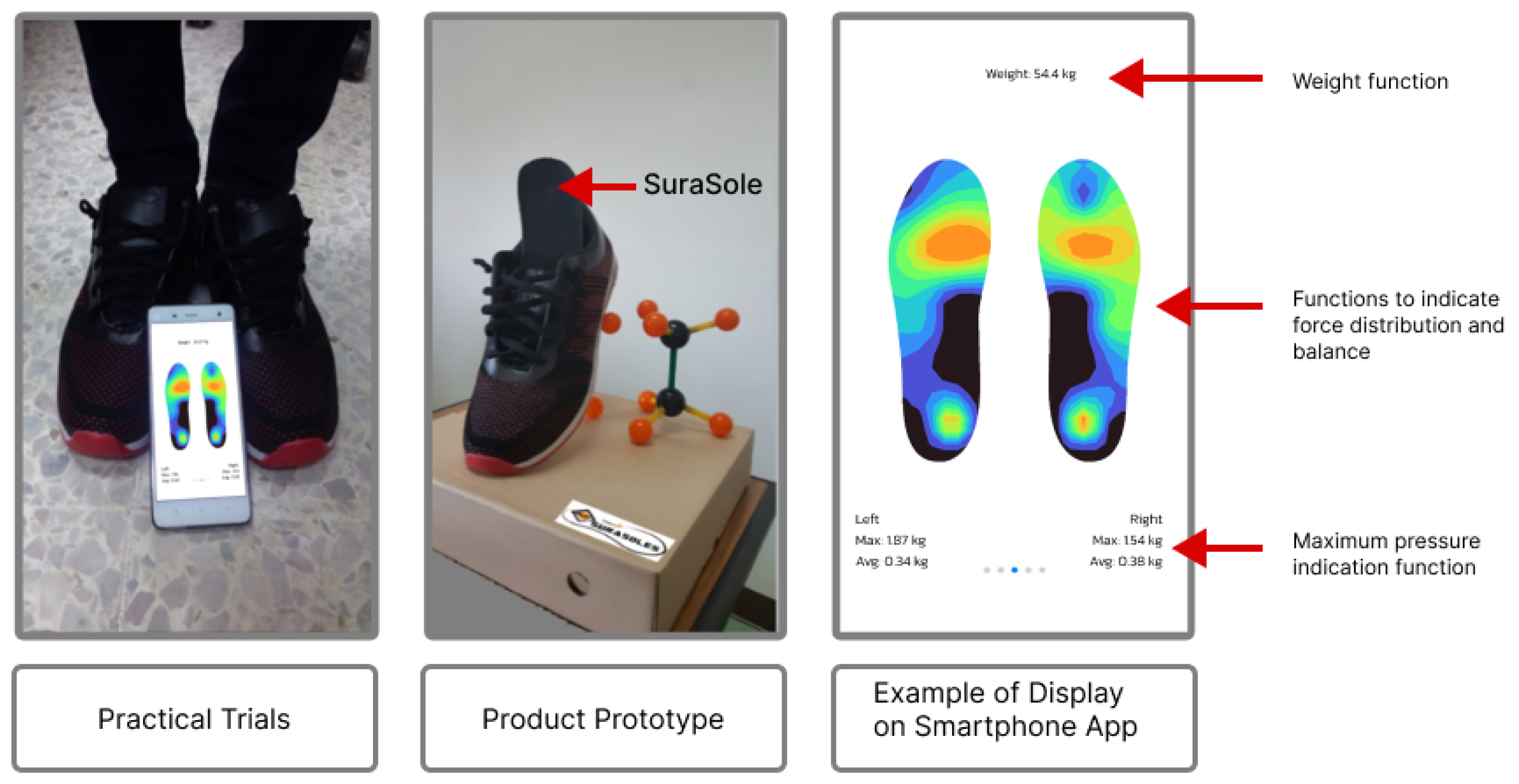

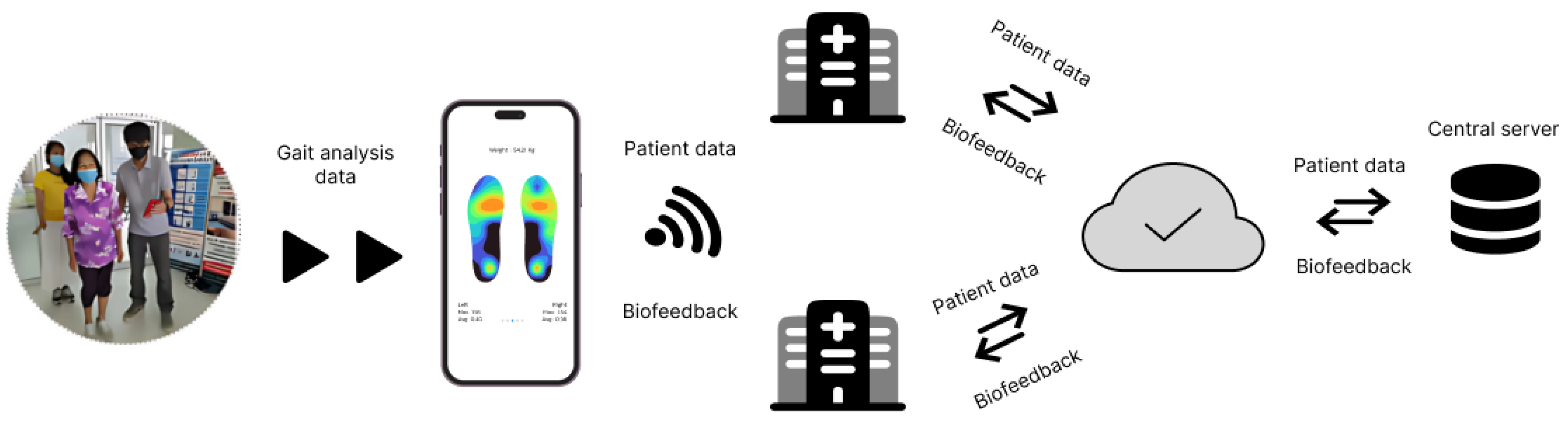

SuraSole® is a locally developed smart insole system that integrates eight pressure sensors, wireless data transmission, and a mobile application designed for real-time visualization and remote data storage. Unlike many imported alternatives, SuraSole is engineered to be affordable, portable, and suitable for deployment in outpatient clinics, rehabilitation centers, and community health programs. Its potential applications include fall-risk assessment, post-operative monitoring, gait retraining, and remote rehabilitation—areas in which objective gait analysis tools are particularly lacking. Despite its increasing use in community health projects in Thailand, no previous study has quantitatively validated its GRF and temporal parameter measurements against gold-standard laboratory systems.

This study addresses this gap by performing a comprehensive clinical and technical validation of the SuraSole insole compared with laboratory-grade force plates and 3D motion capture. By evaluating agreement in GRF across key gait phases—weight acceptance, mid-stance, and push-off—along with temporal gait parameters such as velocity, cadence, stance time, and swing time, this study provides essential evidence for the device’s accuracy, reliability, and suitability for clinical decision-making. Establishing the validity of a low-cost, accessible gait analysis tool has the potential to greatly expand the availability of quantitative gait assessment, especially in regions where laboratory systems are not feasible.

2. Literature Review

Wearable sensor systems have emerged as essential tools for gait analysis, offering a portable, cost-effective alternative to traditional laboratory-based methods such as three-dimensional motion capture and force plates. These technologies have proven valuable in clinical diagnostics, rehabilitation monitoring, and sports performance [

6,

8]. Early work by [

5] on shoe-integrated wireless sensors laid the foundation for modern smart insole systems. Advances in sensor miniaturization, wireless communication, and mobile integration have since improved the usability of these devices, allowing real-time data transmission to smartphones and cloud platforms for remote monitoring [

7].

Several wearable insole systems have been developed and validated in recent years. The OpenGo insole, which integrates 13 force sensors, has been shown to reliably measure temporal gait parameters and estimate the center of pressure (COP). In a comparative validation study, OpenGo demonstrated good agreement with force plates and instrumented treadmills, though its precision in COP measurement was somewhat limited [

9]. Nonetheless, the system achieved high test–retest reliability for temporal parameters (ICC

), making it suitable for clinical monitoring and rehabilitation.

Similarly, the eSHOEs system, embedded with four pressure sensors, has been validated against the GAITRite walkway for measurements of step time, stride time, and swing time. The device showed minimal average differences (<0.05 seconds), confirming its capability for accurate gait monitoring in both healthy individuals and post-surgical patients [

10]. Its portability and consistency support its application in self-rehabilitation programs.

Beyond insole-based systems, other wearable platforms such as inertial measurement units (IMUs) and accelerometry-based detectors have expanded the scope of mobile gait monitoring. These systems offer practical benefits for everyday use and fall risk detection, particularly in older adults and those undergoing rehabilitation [

11,

12,

13].

The SuraSole® smart insole system was developed to address these accessibility and cost barriers. Incorporating eight strategically placed pressure sensors, wireless data transmission, and a cloud-linked mobile application, SuraSole is designed to be deployed in outpatient clinics, rehabilitation departments, and community health programs without requiring laboratory infrastructure. Although SuraSole has been increasingly used in community screening projects in Thailand, formal validation of its GRF and temporal measurements is necessary before widespread clinical adoption.

This study builds upon previous research by quantitatively validating SuraSole against gold-standard force plates and 3D motion capture, focusing on both kinetic (GRF) and temporal gait parameters. By situating SuraSole among existing wearable systems and evaluating its clinical performance, this work contributes to the growing literature on accessible gait technologies and supports the integration of low-cost, locally developed devices into routine clinical assessment.

A comparison of commonly used smart insole and wearable gait analysis systems, including sensor configuration, sampling rate, and key measured parameters, is summarized in

Table 1.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional validation study was conducted at the Excellence Center for Gait and Motion, King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Thai Red Cross Society, Bangkok, Thailand. Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (IRB No. 0713/65). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

3.2. Participants

Inclusion Criteria

Healthy individuals aged over 18 years

No history of lower limb injuries in the past 3 months

Shoe size between 36 and 43 (European size)

Ability to walk independently

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with neuromuscular disorders

Individuals with orthopedic conditions (e.g., lower limb fractures, spinal/knee injuries, osteoarthritis, ankle sprains)

Individuals using gait aids, orthotic devices, or prostheses

Individuals with chronic conditions (e.g., uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, stroke history)

A total of 20 healthy participants meeting the criteria were enrolled.

3.3. Instruments

3.3.1. SuraSole® Smart Insole System

SuraSole is a lightweight, sensor-embedded insole designed for portable gait assessment. Each insole integrates eight force-sensitive resistor (FSR) pressure sensors located at key plantar regions: heel, midfoot, lateral forefoot, medial forefoot, and toe-off area. The system samples pressure data at 20 Hz, which are transmitted via Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) to the SuraSole Med mobile application.

Calibration and preprocessing:

Participants’ height and weight were entered into the system before testing.

Raw sensor voltages were converted to estimated force values using device-specific calibration curves.

Data are normalized to body weight and time-synchronized with force plate recordings using event-based alignment (initial contact detection).

Sensor data were filtered and preprocessed within the mobile application to minimize noise and enhance signal quality.

The application provides real-time visualization of weight distribution and stores processed data on a secure cloud server.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate the device in practical use, the mobile display interface, and the system’s data transmission workflow.

3.3.2. Laboratory-Based Gait Analysis System

The reference system included:

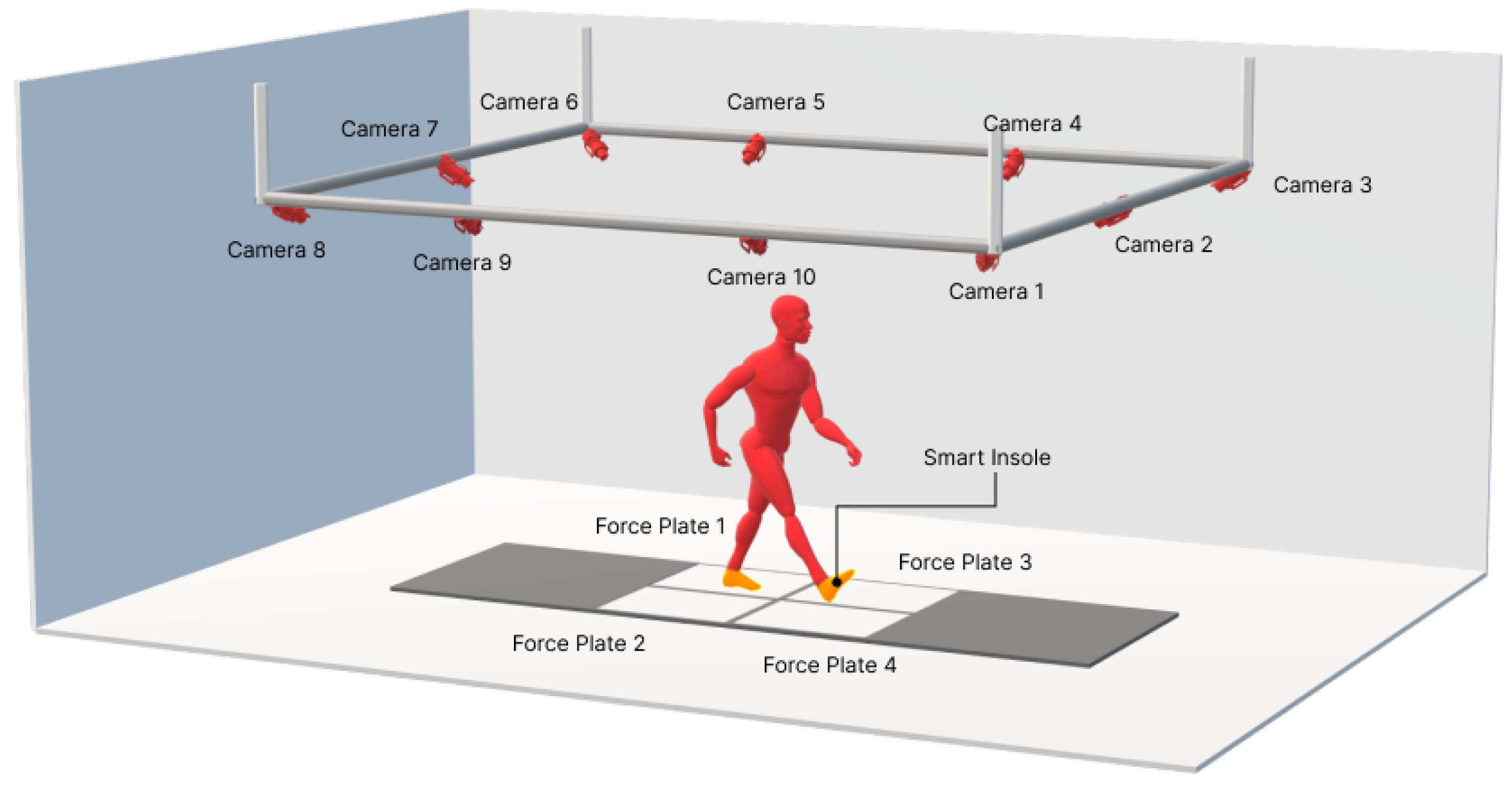

Force plates: Bertec FP4060-07-1000, sampling at 1000 Hz, used as the gold standard for GRF measurement.

Motion capture: OptiTrack® Prime 17W cameras, sampling at 100 Hz, used to determine temporal gait parameters (velocity, cadence, stance time, swing time, and cycle time).

Reflective markers were placed on anatomical landmarks of the foot, including the heel, first and fifth metatarsophalangeal joints, and hallux.

3.4. Experimental Protocol

Participants were fitted with standardized athletic shoes containing SuraSole insoles and reflective markers. The gait assessment protocol consisted of:

Preparation: Standardized shoes were worn to minimize footwear variability. The SuraSole calibration procedure was completed before testing.

Walking Trials: Each participant walked at a self-selected, comfortable pace along a walkway embedded with four force plates. Trials were monitored to ensure clean single-foot contact with force plates; however, participants were encouraged to walk as naturally as possible. A total of five walking trials were recorded per participant.

Data Collection: GRF (ground reaction force) data were collected simultaneously from the SuraSole insole and laboratory-grade force plates. Temporal gait parameters were collected from both the SuraSole app and the motion capture system. Event alignment was performed based on heel-strike timing. The schematic of the experimental setup is illustrated in the

Figure 3.

3.5. Outcome Measures

Demographic data: Age, sex, height, weight, and BMI were recorded.

Ground Reaction Force (GRF) data: Peak GRF values were extracted for three gait phases—weight acceptance, mid-stance, and push-off. Although GRF signals were normalized to body weight during preprocessing, values are reported in Newtons to allow direct comparison with laboratory force plate measurements.

Temporal Gait Parameters: The following parameters were measured: Walking velocity (m/s), cadence (steps/min), cycle time (s), stance time (s), and swing time (s).

3.6. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0.

4. Results

4.1. Participant Demographics

Twenty healthy adults participated in the study, including 9 females (45%) and 11 males (55%). The mean age was 33.55 ± 12.9 years, mean body weight was 67.4 ± 11.9 kg, and mean height was 164 ± 7.3 cm. The average BMI was 25.1 ± 4.5 kg/m². A detailed summary of participant characteristics is presented in

Table 2.

4.2. Ground Reaction Force (GRF) Analysis

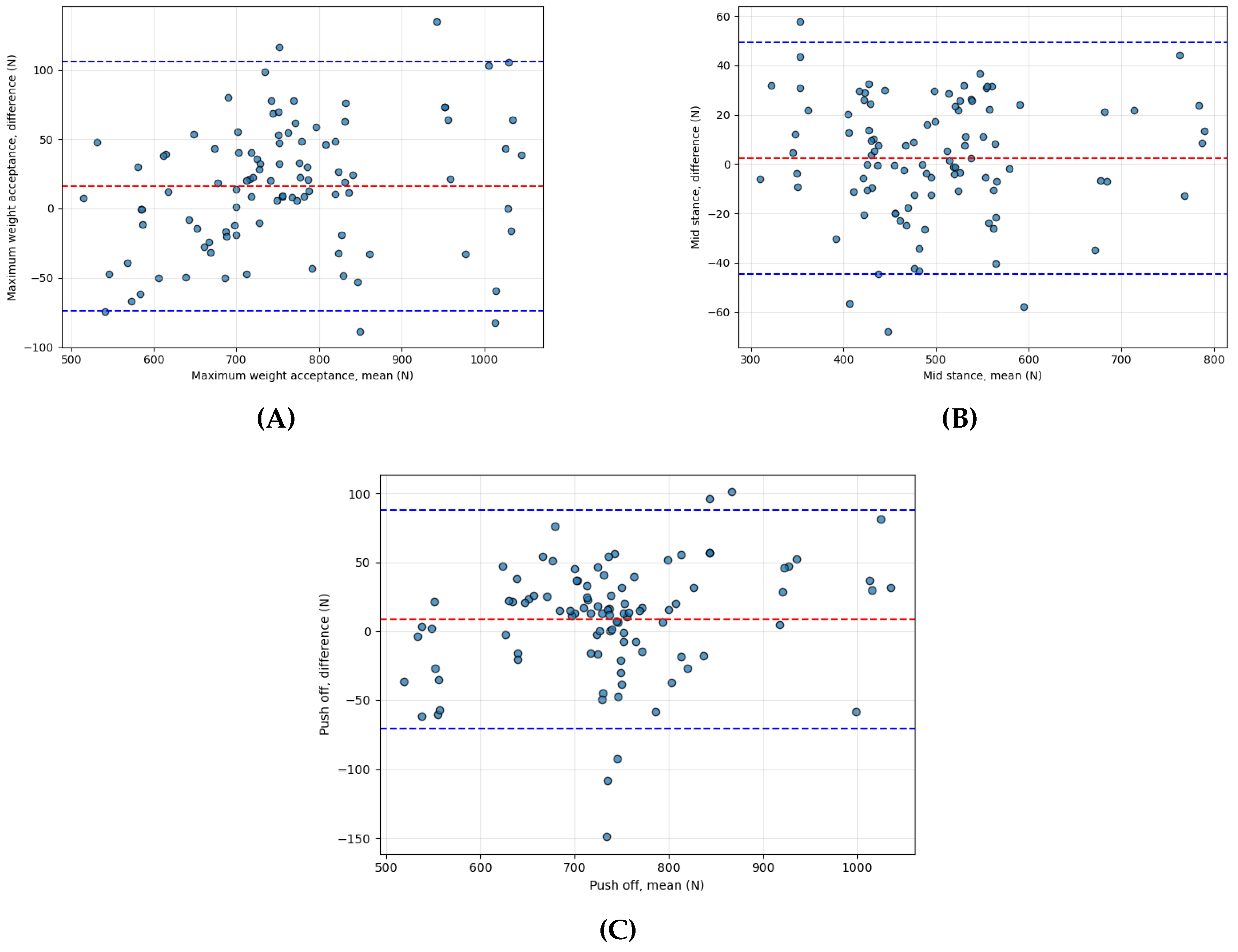

Agreement between the SuraSole insole and the laboratory force plate was assessed for three phases of the stance cycle: maximum weight acceptance, mid-stance, and push-off. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) indicated excellent reliability across all phases, with values ranging from 0.97 to 0.99 (

Table 3).

Bland-Altman analysis demonstrated small mean differences between systems:15.93 N (maximum weight acceptance), 2.38 N (mid-stance), 8.64 N (push-off). The corresponding 95% limits of agreement were narrow and consistent with high measurement agreement (

Table 4). Bland–Altman plots (

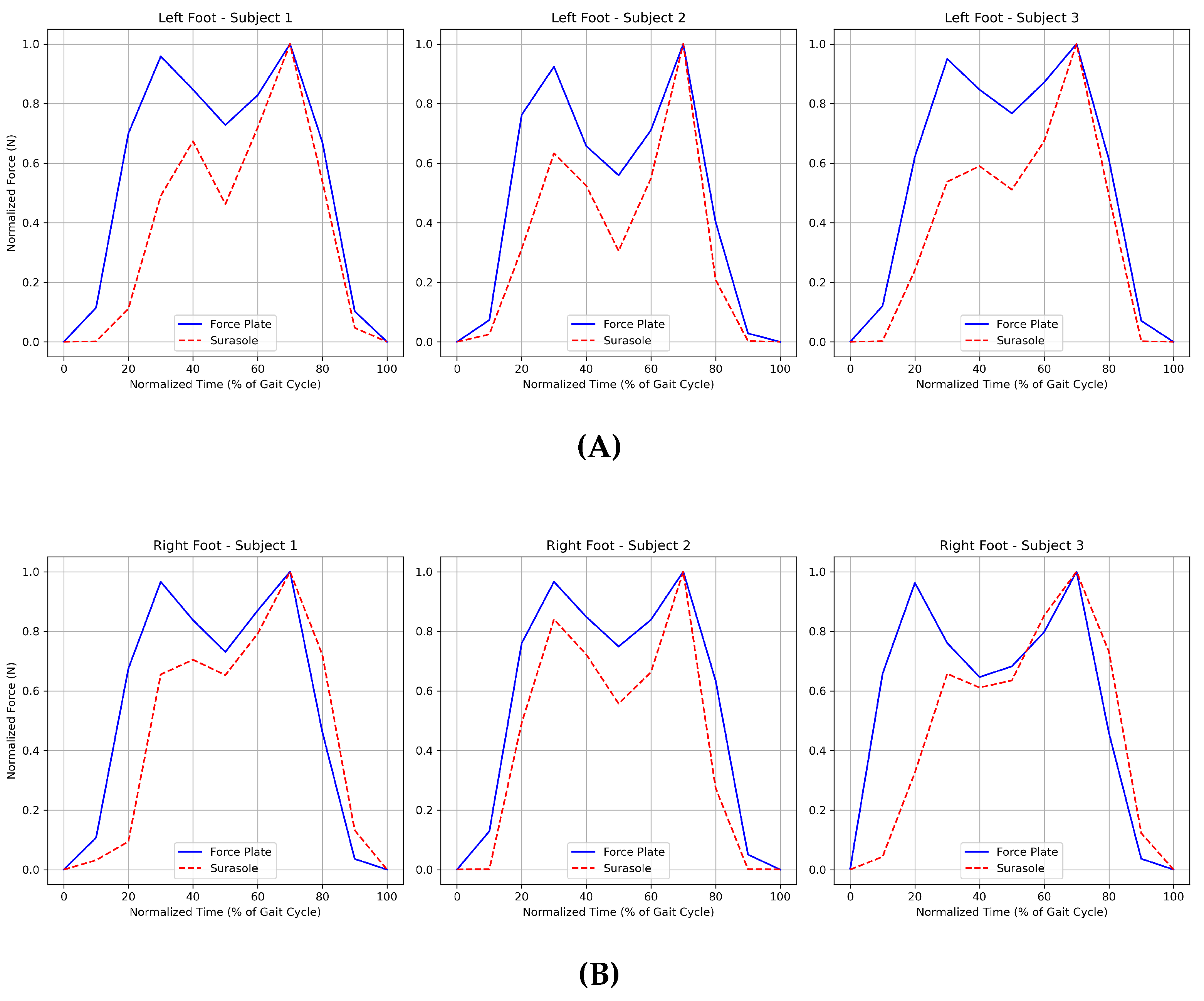

Figure 4) illustrate the distribution of differences and confirm systematic consistency between the two methods.

GRF curves for selected participants showed similar waveform patterns between SuraSole and the force plate across the gait cycle, further supporting agreement in kinetic measurements (

Figure 5a,b).

4.3. Temporal Gait Parameter Analysis

Temporal gait parameters, including velocity, cadence, stance time, swing time, and cycle time—were compared between SuraSole and the motion capture system. ICC values ranged from 0.62 to 0.81, indicating moderate to good reliability depending on the parameter (

Table 5). The highest agreement was observed for cycle time (ICC = 0.81), while stance time demonstrated the lowest reliability (ICC = 0.62).

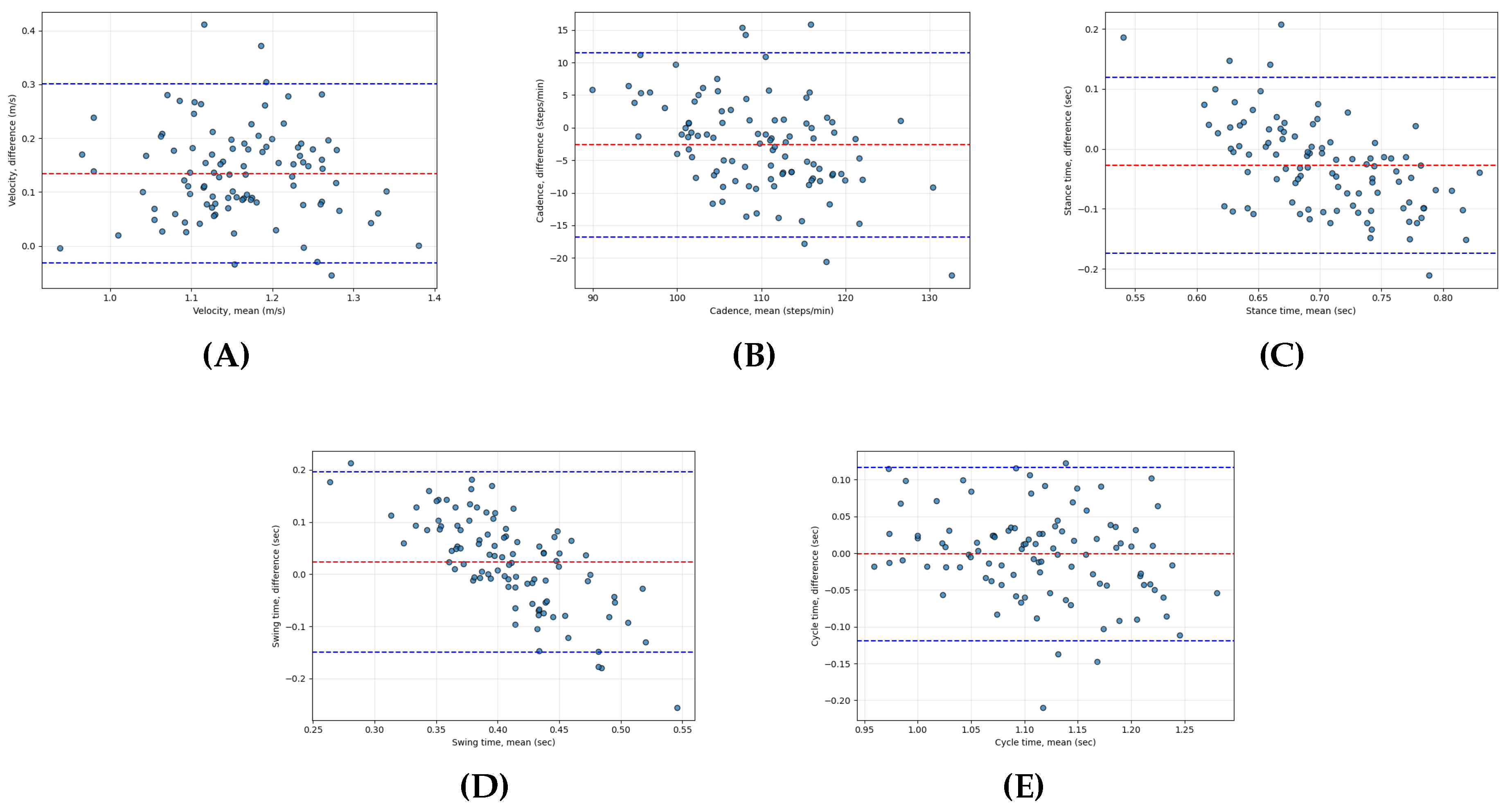

Mean differences from the Bland–Altman analysis were 0.13 m/s for velocity, –2.64 steps/min for cadence, –0.03 s for stance time, 0.02 s for swing time, and –0.001 s for cycle time; full comparison data, and limits of agreement (LoA) are presented in

Table 6 and illustrated in

Figure 6.

Although the SuraSole system produced consistent temporal trends, the magnitude of differences suggests that temporal precision is limited by the device’s 20 Hz sampling frequency compared with the 100 Hz motion capture system.

4.4. Summary of Key Findings

SuraSole demonstrated excellent agreement with the laboratory force plate for GRF measurements across all three stance phases.

Temporal gait parameters exhibited lower reliability, with performance varying by parameter and influenced primarily by sampling frequency.

These findings support the use of SuraSole for clinical GRF assessment and general temporal analysis, but not for applications requiring high temporal precision (e.g., detailed gait event timing).

5. Discussion

This study evaluated the clinical and technical validity of the SuraSole® smart insole system by comparing its ground reaction force (GRF) and temporal gait parameter measurements with those obtained from laboratory-grade force plates and a 3D motion capture system. The findings demonstrate that SuraSole provides highly reliable GRF estimates across key phases of the gait cycle—maximum weight acceptance, mid-stance, and push-off—while offering moderate reliability for temporal gait parameters. These results support the feasibility of using a low-cost, portable, locally developed sensor-embedded insole for clinical gait assessment and community-based health monitoring.

5.1. Agreement in Ground Reaction Force Measurement

The GRF results showed excellent agreement between SuraSole and the laboratory force plate, with ICC values ranging from 0.97 to 0.99. The mean differences across gait phases were small, and Bland–Altman plots demonstrated narrow limits of agreement, indicating that SuraSole can reliably capture phase-specific GRF characteristics during walking. These findings align with previous smart insole validation studies, such as the Moticon OpenGo insole, which reported strong correlations with force plate measurements during walking and running activities [

12]. Similarly, Cramer et al. validated the Insole3 system and reported robust GRF estimation during dynamic activities [

13].

SuraSole uses eight strategically placed force-sensitive resistor sensors, which may explain its ability to capture GRF patterns with good fidelity. Although SuraSole has fewer sensors than Moticon’s 13-sensor system, its placement in key load-bearing regions provides sufficient data for phase-specific GRF estimation. This suggests that sensor configuration, rather than sensor quantity alone, plays a critical role in accurately capturing GRF trends.

5.2. Temporal Parameter Reliability and Sampling Rate Considerations

In contrast to the GRF findings, agreement for temporal gait parameters ranged from moderate to good (ICC = 0.62–0.81). These results reflect a common limitation in pressure-based insoles with lower sampling frequencies. SuraSole samples at 20 Hz, whereas motion capture systems typically operate at 100–200 Hz, and some validated insoles operate at 50–100 Hz [

9,

17]. Lower sampling frequencies limit the temporal resolution required to accurately detect gait events such as heel strike, toe-off, and mid-swing, resulting in small but meaningful discrepancies in stance and swing time measurements [

18].

Comparable results have been reported in the literature. The eSHOEs system, which samples at 50 Hz, demonstrated high accuracy for step and stride timing but was less precise for rapid gait transitions [

4]. IMU-based systems, which often exceed 100 Hz, have shown superior temporal precision but cannot directly measure GRF [

11,

14]. Thus, the moderate temporal agreement observed in SuraSole is consistent with expectations for a device operating at a lower sampling frequency and designed primarily for portability and affordability.

5.3. Clinical and Practical Implications

Despite limitations in temporal accuracy, the strong GRF agreement observed in this study positions SuraSole as a promising tool for clinical gait assessment, especially in settings where access to laboratory equipment is limited. GRF patterns provide essential information for evaluating weight-bearing behavior, gait symmetry, post-surgical recovery, and fall risk. In Thailand and many other countries, gait laboratories are available only in tertiary hospitals, limiting their use for screening older adults or monitoring rehabilitation progress. A portable insole-based solution can help bridge this gap by providing clinicians with quantitative data during routine outpatient visits.

SuraSole’s integration with a mobile application and secure cloud platform enables remote monitoring and potential use in home-based rehabilitation programs. Such capabilities align with the growing emphasis on telemedicine and community-based care, particularly for populations with mobility impairments. Because the device is locally manufactured, it offers a cost advantage over imported systems, reducing financial barriers to implementation in public hospitals and community clinics.

5.4. Comparison with Previous Wearable Insole Studies

The performance of SuraSole compares favorably with several established smart insole systems. Moticon’s OpenGo demonstrated excellent GRF validity but remains relatively expensive and less accessible in Southeast Asia. Insole3 provides strong temporal and kinetic accuracy but relies on proprietary hardware not widely available. SuraSole’s validation contributes new knowledge by assessing a low-cost, regionally developed device in a real clinical environment, addressing a gap in the literature where validation studies have predominantly been performed in high-income countries.

Additionally, most previous studies focused on either kinetic or temporal validation, while this study evaluates both domains simultaneously. This dual validation provides a more comprehensive characterization of device performance and informs realistic expectations for clinical use.

5.5. Interpretation of Findings and Future Development

The excellent GRF performance indicates that the current hardware configuration is adequate for capturing functional loading patterns. However, the moderate temporal accuracy suggests opportunities for improvement. Increasing the sampling rate to 50–100 Hz, integrating IMU sensors to detect gait events more precisely, or implementing machine learning–based event detection algorithms could substantially enhance temporal validity.

Future studies should evaluate SuraSole in diverse populations, including older adults, patients recovering from orthopedic surgery, and individuals with neurological conditions such as stroke or Parkinson’s disease. Longitudinal studies are also warranted to determine the device’s sensitivity to clinical change over time and its applicability for fall-risk prediction.

6. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings. First, the sample consisted of healthy adults, which limits the generalizability of the results to clinical populations with gait impairments such as older adults, post-operative patients, or individuals with neurological disorders. Validation in these groups is necessary to determine applicability in real clinical settings. Second, participants walked at a self-selected speed, which may have introduced variability in temporal gait parameters. Controlled-speed protocols or treadmill-based assessments may reduce variability in future studies. Third, the SuraSole insole samples at 20 Hz, considerably lower than the 100–1000 Hz sampling rate of motion capture and force plate systems. This difference likely contributed to reduced temporal accuracy. Fourth, the study required participants to achieve accurate foot placement on embedded force plates, which may have influenced natural walking behavior. Finally, the SuraSole system estimates GRF based on pressure sensor output and does not directly measure shear forces or center-of-pressure trajectories, which may limit its use in applications requiring detailed kinetic modeling.

7. Conclusions

The SuraSole® smart insole demonstrated excellent agreement with laboratory force plates for phase-specific ground reaction force measurements and moderate accuracy for temporal gait parameters. These results indicate that SuraSole is a viable, low-cost, and portable alternative for gait assessment in clinical and community settings, particularly where access to laboratory-based systems is limited. Its reliable GRF performance supports use in routine evaluations of weight-bearing behavior, gait symmetry, and rehabilitation progress. While improvements in sampling frequency and sensor integration may enhance temporal measurement precision, the current system already offers substantial value for clinical screening and tele-rehabilitation applications. As a locally developed technology, SuraSole holds promise for expanding access to quantitative gait assessment in resource-limited environments and enabling scalable community-based mobility monitoring initiatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L., T.V. and P.Y.; methodology, T.L. and T.V.; software, D.K.A. and W.J.; validation, T.V. and P.Y.; formal analysis, T.L., D.K.A. and T.V.; project administration, T.V.; funding acquisition, T.L. and T.V.; investigation, T.L., D.K.A., T.V. and P.Y.; resources, D.K.A. and W.J.; data curation, T.L., T.V. and W.J.; writing—original draft, T.L., D.K.A. and T.V.; writing—review and editing, D.K.A. and S.L.; visualization, D.K.A.; supervision, T.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ratchadapisek Somphot Fund, Graduate Affairs, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (Grant Number GA66/57).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted at the Excellence Center for Gait and Motion, King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Thai Red Cross Society, Bangkok, Thailand, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (IRB No. 0713/65) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has also been obtained from the patients for the publication of this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to ethical considerations.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants for their time and effort in this study. We also acknowledge Chulalongkorn University for granting access to the Excellence Center for Gait and Motion, which was vital for this research. This work was supported by the Ratchadapisek Somphot Fund, Graduate Affairs, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (Grant Number GA66/57).

Conflicts of Interest

The SuraSole® system was developed locally; however, the authors declare that the study was conducted independently, and the funders had no role in study design, data analysis, or interpretation.

References

- Armand, S; et al. Current practices in clinical gait analysis in Europe: A comprehensive survey-based study from the European Society for Movement Analysis in Adults and Children (ESMAC) standard initiative. Gait Posture 2024, 111, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bland, JM; Altman, DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986, 1, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S; et al. Toward pervasive gait analysis with wearable sensors: A systematic review. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2016, 20(6), 1521–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagos, H; et al. Mobile gait analysis via eSHOEs instrumented shoe insoles: a pilot study for validation against the gold standard GAITRite®. J Med Eng Technol. 2017, 41(5), 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthik, P; Salian, KHD; Ranjith, S; Salian, J; Shetty, KA. Wearable sensor-based gait analysis: Advanced feature extraction techniques. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, TK; Li, MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016, 15(2), 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovecchio, N; Zago, M; Sforza, C. Gait analysis in the rehabilitation process. In Gait Analysis: Clinical and Research Applications; Springer, 2021; pp. 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerbekke, MS; et al. Concurrent validity and reliability of wireless instrumented insoles measuring postural balance and temporal gait parameters. Gait Posture 2016, 51, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saboor, A; et al. Latest research trends in gait analysis using wearable sensors and machine learning: A systematic review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 167830–167864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenum, J; Hsu, MM; Pantelyat, AY; Roemmich, RT. Clinical gait analysis using video-based pose estimation: Multiple perspectives, clinical populations, and measuring change. PLOS Digit Health 2024, 3(3), e0000467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storm, FA; Cesareo, A; Reni, G; Biffi, E. Wearable inertial sensors to assess gait during the 6-minute walk test: A systematic review. Sensors 2020, 20(9), 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stöggl, T; Martiner, A. Validation of Moticon’s OpenGo sensor insoles during gait, jumps, balance and cross-country skiing specific imitation movements. J Sports Sci. 2017, 35(2), 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramer, LA; Wimmer, MA; Malloy, P; O’Keefe, JA; Knowlton, CB; Ferrigno, C. Validity and reliability of the Insole3 instrumented shoe insole for ground reaction force measurement during walking and running. Sensors 2022, 22(6), 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, CC; Hsu, YL. A review of accelerometry-based wearable motion detectors for physical activity monitoring. Sensors 2010, 10(8), 7772–7788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, BJ; Veith, NT; Hell, R; Döbele, S; Roland, M; Rollmann, M; Holstein, J; Pohlemann, T. Validation and reliability testing of a new, fully integrated gait analysis insole. J Foot Ankle Res. 2015, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, SJM; Benbasat, AY; Scarborough, DM; Krebs, DE; Paradiso, JA. Gait analysis using a shoe-integrated wireless sensor system. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2008, 12(4), 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, S; Ilius, FA; Jamal, DM. Wearable sensor systems for fall risk assessment: A review. Front Digit Health 2022, 4, 921506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X; Zhao, C; Zheng, B; Guo, Q; Duan, X; Wulamu, A; Zhang, D. Wearable devices for gait analysis in intelligent healthcare. Front Comput Sci. 2021, 3, 661676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).