1. Introduction

The emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs) has fundamentally transformed the landscape of artificial intelligence, demonstrating unprecedented capabilities across a diverse spectrum of cognitive tasks [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. These models, built upon the Transformer architecture [

7] and trained on massive corpora of text data, have exhibited remarkable proficiency in natural language understanding, generation, and increasingly, in tasks that require complex reasoning [

8,

9,

10,

11]. From solving mathematical word problems to engaging in multi-step logical inference, LLMs have progressively expanded the boundaries of what was previously considered achievable through purely statistical language modeling.

Reasoning, broadly defined as the cognitive process of drawing conclusions from available information through logical steps, represents one of the most fundamental and challenging capabilities for artificial intelligence systems to acquire [

12]. The ability to reason effectively underpins performance across numerous practical applications, including scientific discovery, medical diagnosis, legal analysis, and software engineering. Consequently, the development of robust reasoning capabilities in LLMs has emerged as a central focus of contemporary research, attracting substantial attention from both academic and industrial communities [

13,

14,

15].

The past several years have witnessed remarkable progress in enhancing the reasoning capabilities of LLMs through various methodological innovations. Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, introduced by Wei et al. [

16,

17,

18], demonstrated that explicitly encouraging models to generate intermediate reasoning steps before arriving at final answers can dramatically improve performance on complex reasoning tasks. This foundational insight has spawned a rich ecosystem of prompting-based techniques, including Self-Consistency [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], Zero-Shot CoT [

25,

26,

27], Least-to-Most prompting [

28], Tree of Thoughts [

29,

30,

31,

32], and Graph of Thoughts [

33,

34,

35]. Recent surveys have categorized these developments under the broader “Chain-of-X” paradigm [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Concurrently, training-based approaches have explored methods to internalize reasoning capabilities more deeply within model parameters, ranging from reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) [

40,

41,

42] to process reward models that provide step-level supervision [

43,

44,

45,

46].

Despite these advances, a fundamental limitation persists: LLMs exhibit a persistent error rate that prevents reliable scaling to extended sequential processes [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. While models can successfully navigate tasks requiring tens or perhaps hundreds of dependent reasoning steps, performance degrades catastrophically as task complexity increases. Recent empirical investigations using the Towers of Hanoi benchmark domain have starkly illustrated this phenomenon, demonstrating that even state-of-the-art reasoning models inevitably fail beyond approximately a few hundred steps [

52,

53]. This error propagation problem represents a critical barrier to deploying LLMs for solving problems at the scale routinely addressed by human organizations and societies.

The recognition of this scalability challenge has motivated the exploration of alternative paradigms that move beyond optimizing individual model performance. Massively Decomposed Agentic Processes (MDAPs), as exemplified by the MAKER framework [

52,

54], represent a promising new direction that achieves reliable long-horizon task execution through the combination of extreme task decomposition and multi-agent error correction. By decomposing complex tasks into minimal subtasks that can be tackled by focused microagents, and applying efficient voting schemes to correct errors at each step, MAKER has demonstrated the unprecedented capability of solving tasks with over one million LLM steps with zero errors. This achievement suggests that the path toward solving organizational and societal-scale problems may lie not solely in improving individual model capabilities, but in designing sophisticated agentic architectures that leverage the complementary strengths of multiple model instances.

This survey provides a comprehensive examination of reasoning in Large Language Models, synthesizing the extensive body of research that has emerged in this rapidly evolving field. We organize the landscape of LLM reasoning into a coherent taxonomy that encompasses three primary paradigms: prompting-based methods that elicit reasoning through carefully designed input structures, training-based methods that instill reasoning capabilities through specialized learning objectives, and multi-agent systems that achieve robust reasoning through collaborative architectures. For each paradigm, we analyze the underlying principles, review representative techniques, and evaluate empirical performance across major benchmarks.

The contributions of this survey are fourfold. First, we establish a unified taxonomy that organizes the diverse landscape of LLM reasoning approaches into a coherent framework, facilitating systematic comparison and analysis. Second, we provide an in-depth examination of the error propagation problem that limits long-horizon reasoning, synthesizing empirical evidence and theoretical perspectives on this critical challenge. Third, we analyze the emerging paradigm of massively decomposed agentic processes, examining how extreme decomposition combined with multi-agent error correction can achieve reliable reasoning at unprecedented scales. Fourth, we identify key open challenges and promising research directions, providing a roadmap for future investigations in this field.

The remainder of this survey is organized as follows.

Section 2 establishes the necessary background on LLMs and reasoning, defining key concepts and evaluation metrics.

Section 3 presents our proposed taxonomy of LLM reasoning approaches.

Section 4,

Section 5, and

Section 6 provide detailed analyses of prompting-based, training-based, and multi-agent reasoning methods, respectively.

Section 7 synthesizes empirical findings across major benchmarks.

Section 8 discusses key insights and lessons learned.

Section 9 identifies open challenges and future research directions.

Section 10 concludes the survey with a summary of key findings and their implications for the field.

2. Background and Preliminaries

This section establishes the foundational concepts necessary for understanding reasoning in Large Language Models. We begin by defining key terminology and formalizing the reasoning problem, then introduce the major model architectures and training paradigms that underpin modern LLMs, and conclude with an overview of evaluation metrics and benchmark datasets commonly employed in the field.

2.1. Large Language Models: Foundations

Large Language Models represent a class of deep neural networks trained on massive text corpora to model the statistical distribution of natural language [

1,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. The foundational architecture underlying virtually all contemporary LLMs is the Transformer [

7,

60,

61], which introduced the self-attention mechanism enabling models to capture long-range dependencies in text more effectively than prior recurrent architectures.

The core of the Transformer architecture is the self-attention mechanism, which computes attention weights as:

where

Q,

K, and

V represent query, key, and value matrices respectively, and

is the dimension of the key vectors. Multi-head attention extends this by computing multiple attention functions in parallel:

where each

.

Figure 1 illustrates the standard Transformer decoder block used in autoregressive language models.

The training of LLMs typically proceeds through two primary phases. The first phase, pretraining, involves optimizing the model on a next-token prediction objective:

where

represents model parameters and

T is the sequence length. The second phase, fine-tuning or alignment, adapts the pretrained model for specific downstream tasks [

40].

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of major LLM families relevant to reasoning research.

2.2. Defining Reasoning in LLMs

Reasoning in the context of LLMs refers to the capacity to derive new conclusions or solve problems by combining and manipulating available information through a sequence of logical steps [

13]. We formally define the reasoning task as follows.

Definition 1

(Reasoning Task). A reasoning task is a tuple where Q is the query space, C is the context space, A is the answer space, and is the reasoning function that maps queries and contexts to valid answers.

For multi-step reasoning, we extend this definition to include intermediate reasoning steps:

Definition 2

(Multi-Step Reasoning).

A multi-step reasoning process generates a sequence of intermediate steps such that:

where f is the step generation function and the final step yields the answer .

Table 2 categorizes the primary types of reasoning evaluated in LLM research.

2.3. The Error Propagation Problem

A critical challenge in LLM reasoning is the phenomenon of error propagation, wherein mistakes made in early reasoning steps compound as the reasoning chain extends [

47,

52].

Let

p denote the probability of a single-step error. For a task requiring

n sequential steps, the probability of completing the task without any error is:

This exponential decay is illustrated in

Figure 2, which shows how even small per-step error rates lead to catastrophic failure on long-horizon tasks.

The expected number of steps before first error follows a geometric distribution:

For , this yields an expected 100 steps before failure, far short of the millions of steps required for organizational-scale problems.

2.4. Evaluation Metrics and Benchmarks

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of major reasoning benchmarks.

The primary evaluation metrics are formally defined as:

where

n is total samples,

c is correct samples, and

k is the selection size.

2.5. Test-Time Compute and Inference Scaling

A recent paradigm shift concerns the allocation of computational resources at inference time [

68]. The relationship between test-time compute and performance can be characterized as:

where

is an empirically determined scaling exponent.

Figure 3 illustrates this scaling relationship across different reasoning benchmarks.

This observation has profound implications for the economics of LLM reasoning, suggesting that practitioners can achieve improved reasoning by dedicating more inference-time resources to each query rather than investing solely in ever-larger models [

69]. Recent work has explored the efficiency frontiers of “thinking budgets” in reasoning tasks, revealing scaling laws between computational resources and reasoning quality.

3. Taxonomy of LLM Reasoning Approaches

The landscape of techniques for enhancing reasoning in Large Language Models has grown remarkably diverse. To provide a structured understanding of this field, we propose a taxonomy that organizes existing approaches into three primary paradigms: prompting-based methods, training-based methods, and multi-agent systems. This section presents an overview of this taxonomy and discusses the relationships and complementarities among different approaches.

3.1. Taxonomy Overview

Figure 4 presents our proposed taxonomy of LLM reasoning approaches. At the highest level, we distinguish methods based on whether they primarily operate at inference time through prompt engineering (prompting-based), require model training or fine-tuning (training-based), or leverage multiple model instances working collaboratively (multi-agent systems).

3.2. Prompting-Based Methods

Prompting-based methods enhance reasoning capabilities by carefully designing the input provided to the model, without modifying its parameters [

70,

71,

72]. These approaches leverage the in-context learning abilities of pretrained LLMs to elicit reasoning behaviors through demonstration and instruction.

The foundational technique in this category is Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting [

16], which encourages models to generate intermediate reasoning steps before arriving at final answers. Building upon this foundation, Self-Consistency [

19] samples multiple reasoning paths and selects the most frequently occurring answer through majority voting. Zero-Shot CoT [

25] demonstrates that the simple prompt “Let’s think step by step” can elicit reasoning without requiring demonstration examples.

Structural extensions to CoT include Tree of Thoughts (ToT) [

29], which enables exploration of multiple reasoning branches with backtracking, and Graph of Thoughts (GoT) [

33], which allows arbitrary connections between reasoning units. These approaches provide greater flexibility in navigating complex solution spaces but typically incur higher computational costs.

Decomposition-based prompting techniques, including Least-to-Most prompting [

28] and decomposed prompting, address complex problems by explicitly breaking them into simpler subproblems. This approach proves particularly effective for tasks requiring compositional generalization beyond the complexity of training examples.

3.3. Training-Based Methods

Training-based methods aim to internalize reasoning capabilities within model parameters through specialized training objectives . These approaches typically build upon pretrained LLMs and apply additional training phases designed to enhance specific reasoning abilities.

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) [

40] represents the dominant paradigm for aligning LLMs with human preferences, including preferences for correct and well-reasoned responses. The RLHF pipeline involves training a reward model on human preference data, then using this reward model to guide policy optimization of the language model through algorithms such as Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO).

Process supervision approaches, exemplified by Process Reward Models (PRMs) [

43,

44,

73], provide fine-grained feedback on individual reasoning steps rather than only on final answers. This approach has demonstrated superior performance on mathematical reasoning tasks and offers greater interpretability and alignment benefits compared to outcome-only supervision [

45].

Self-taught reasoning methods, such as STaR [

74], enable models to bootstrap their reasoning capabilities by generating their own training data. Through iterative cycles of generating rationales, filtering for correct answers, and fine-tuning, these approaches can progressively improve reasoning performance without extensive human annotation.

The development of reasoning-specialized models such as OpenAI’s o1 [

68] and DeepSeek-R1 [

75] represents the culmination of training-based approaches, combining large-scale reinforcement learning with extended chain-of-thought generation to achieve substantial improvements on reasoning benchmarks.

3.4. Multi-Agent Systems

Multi-agent systems approach reasoning by orchestrating collaboration among multiple LLM instances [

76,

77,

78]. This paradigm recognizes that individual model instances, despite inherent error rates, can achieve greater collective reliability through appropriate coordination mechanisms [

79,

80].

Collaborative agent frameworks such as AutoGen [

77] and MetaGPT [

81] enable multiple agents with different roles to work together on complex tasks. These systems often incorporate human-in-the-loop elements and can leverage specialized tools and external knowledge sources.

Voting and verification mechanisms represent a crucial class of techniques for improving reliability [

19]. By generating multiple candidate solutions and applying consensus mechanisms, these approaches can significantly reduce error rates compared to single-sample generation. The effectiveness of voting scales with the number of samples and the diversity of reasoning paths.

The most recent and ambitious development in this paradigm is the concept of Massively Decomposed Agentic Processes (MDAPs), exemplified by the MAKER framework [

52]. MAKER achieves reliable long-horizon reasoning through extreme task decomposition into minimal subtasks, each handled by focused microagents, combined with efficient multi-agent voting for error correction at every step. This approach has demonstrated the capability to solve tasks with over one million steps with zero errors, suggesting a promising path toward organizational-scale problem solving.

3.5. Relationships Among Paradigms

The three paradigms identified in our taxonomy are not mutually exclusive; rather, they represent complementary approaches that can be combined synergistically. Prompting-based methods provide immediately accessible improvements without requiring model training, making them valuable for rapid prototyping and deployment. Training-based methods can internalize successful prompting strategies, potentially yielding more efficient inference. Multi-agent systems can incorporate both prompting and specially trained models as their constituent agents.

A key insight emerging from recent research is the relationship between test-time compute and training-time compute . Prompting-based methods and multi-agent systems represent alternative ways of investing computational resources at inference time, while training-based methods invest resources during model development. The optimal allocation between these modalities depends on factors including deployment scale, latency requirements, and the availability of training data.

The MAKER framework illustrates how these paradigms can be combined effectively. While MAKER employs relatively simple prompting strategies for individual microagents, its power derives from the sophisticated multi-agent orchestration layer that coordinates their collaboration and ensures error correction. This suggests that future advances may arise not only from improving individual techniques but also from developing more sophisticated integration strategies.

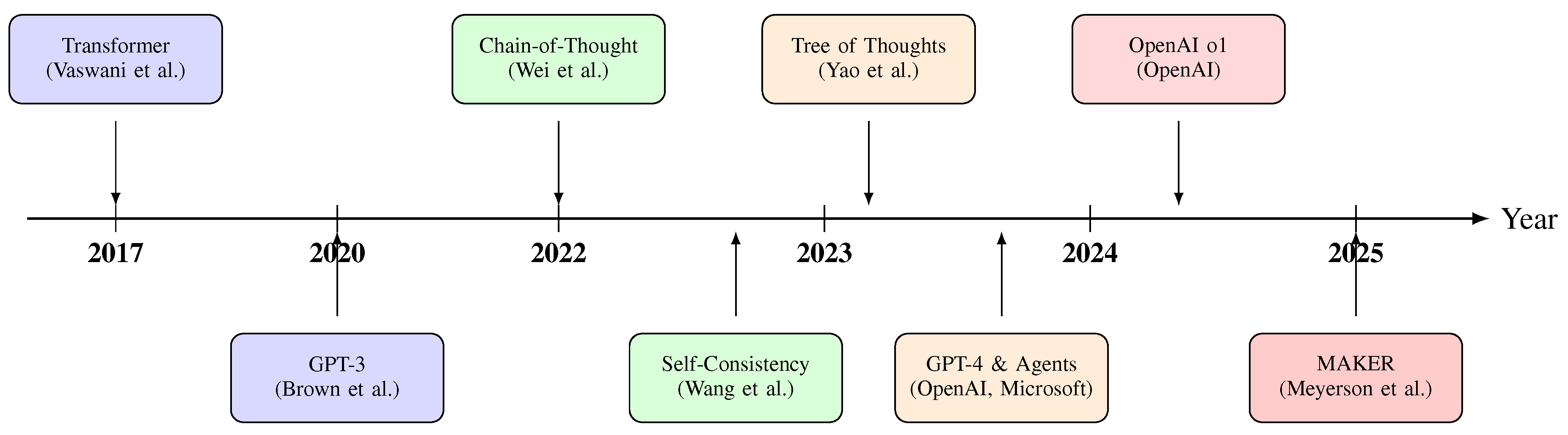

3.6. Evolution Timeline

Figure 5 presents a timeline of major developments in LLM reasoning, highlighting the progression from foundational architectures to contemporary massively decomposed approaches.

4. Prompting-Based Reasoning Methods

Prompting-based methods represent the most accessible and widely adopted approach to enhancing reasoning in Large Language Models [

36,

37,

82]. These techniques leverage the in-context learning capabilities of pretrained LLMs to elicit improved reasoning performance without requiring any modification to model parameters [

71]. This section provides a comprehensive analysis of major prompting-based reasoning techniques.

4.1. Chain-of-Thought Prompting

Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, introduced by Wei et al. [

16], represents a foundational breakthrough in LLM reasoning research. The key insight is that encouraging models to generate intermediate reasoning steps before producing final answers dramatically improves performance.

Formally, let

denote an LLM. Standard prompting computes:

where

q is the query and

are demonstrations. CoT prompting extends this to:

where

r represents the reasoning chain and

.

Figure 6 illustrates the difference between standard and CoT prompting.

Table 4 summarizes the performance improvements achieved by CoT prompting across various benchmarks.

4.2. Zero-Shot Chain-of-Thought

Kojima et al. [

25] demonstrated that significant reasoning improvements can be achieved through the simple prompt “Let’s think step by step.” The Zero-Shot CoT process can be formalized as:

where ⊕ denotes concatenation.

Figure 7 shows the two-stage Zero-Shot CoT pipeline.

4.3. Self-Consistency

Self-Consistency [

19,

20,

83] addresses the reliance on single reasoning paths by sampling multiple chains and aggregating through majority voting. Recent extensions include Universal Self-Consistency for free-form tasks and confidence-informed sampling for improved efficiency [

84]. Given

K sampled reasoning chains

and corresponding answers

, the final answer is:

The probability of selecting the correct answer improves with more samples. If each sample has probability

of being correct, the majority vote error rate is:

Figure 8 illustrates the Self-Consistency mechanism.

Table 5 shows the accuracy improvement with increasing sample count.

4.4. Tree and Graph of Thoughts

Tree of Thoughts (ToT) [

29,

30] enables systematic exploration of reasoning paths, while Graph of Thoughts (GoT) [

33,

34] further extends this to arbitrary graph structures. The search process can be formalized as finding the optimal path through a state space:

where

is the value function evaluating state quality.

Figure 9 compares the structural differences between CoT, ToT, and GoT.

Table 6 compares performance across reasoning structures.

4.5. Decomposition-Based Prompting

Least-to-Most prompting [

28] decomposes problems into subproblems. The two-stage process is:

Program of Thoughts (PoT) [

85] generates executable code:

Table 7 compares decomposition methods.

4.6. Reasoning with Tool Use

ReAct [

86] interleaves reasoning and action:

where

is thought,

is action,

is observation, and

is the environment.

Table 8 provides a comprehensive summary of prompting-based methods.

5. Training-Based Reasoning Methods

While prompting-based methods operate on frozen model parameters, training-based approaches aim to internalize reasoning capabilities more deeply within the model through specialized training objectives. This section examines the major paradigms for training LLMs to reason more effectively, ranging from alignment techniques to self-improvement methods and the emerging class of reasoning-specialized models.

5.1. Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) has emerged as the dominant paradigm for aligning LLM outputs with human preferences [

40]. The RLHF pipeline, as implemented in InstructGPT and subsequent models, comprises three main stages that progressively refine model behavior.

The first stage involves Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), where the model is trained on demonstrations of desired behavior collected from human labelers . These demonstrations typically include examples of helpful, truthful, and harmless responses across a variety of tasks. The SFT stage establishes a baseline of instruction-following capability upon which subsequent stages build.

The second stage trains a Reward Model (RM) to predict human preferences. Human labelers compare pairs of model outputs and indicate which response is preferable. These preference labels are used to train a reward model that assigns scalar scores to responses, with higher scores indicating greater alignment with human preferences. The reward model effectively distills human judgment into a differentiable signal that can guide model optimization.

The third stage applies reinforcement learning, typically using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), to fine-tune the language model to maximize the reward model’s scores. The PPO objective for RLHF can be expressed as:

where

is the reward model score,

is the policy being optimized,

is the reference policy (SFT model), and

controls the KL penalty strength. This optimization is constrained to prevent the model from deviating too far from the SFT initialization. The resulting model balances maximizing reward with maintaining the linguistic capabilities acquired during pretraining.

Figure 11 illustrates the complete RLHF training pipeline.

RLHF has proven highly effective for improving the quality and safety of LLM outputs. InstructGPT, despite having only 1.3 billion parameters, was preferred by human evaluators over the 175 billion parameter GPT-3 model 71% of the time [

40]. This dramatic improvement demonstrates that alignment training can be more efficient than simply scaling model size.

For reasoning tasks specifically, RLHF contributes by rewarding responses that demonstrate clear, logical reasoning steps. However, standard RLHF provides only sparse feedback on final answer quality, potentially failing to address errors in intermediate reasoning steps. This limitation motivates the development of process supervision approaches.

5.2. Process Reward Models

Process Reward Models (PRMs) [

43,

44,

73] extend the reward modeling paradigm by providing fine-grained feedback on individual reasoning steps rather than only on final answers. This approach, termed process supervision, offers several advantages over outcome supervision for training reasoning models [

45].

In outcome supervision, the reward model evaluates only the final answer, providing a single reward signal for the entire reasoning chain. The outcome reward can be formalized as:

where

is the correct answer and

is the reasoning chain. While simpler to implement, this approach fails to distinguish between correct reasoning that leads to wrong answers due to minor errors and fundamentally flawed reasoning that happens to arrive at correct answers.

Process supervision addresses this by evaluating each step independently:

where

evaluates the correctness of step

given the context. This formulation enables more targeted credit assignment.

Figure 12 contrasts process and outcome supervision approaches.

The development of PRMs requires step-level annotations, which are more expensive to collect than answer-level labels. Lightman et al. [

43] released PRM800K, a dataset containing 800,000 step-level human feedback labels on mathematical reasoning problems. Human labelers evaluated each step as correct, incorrect, or neutral, providing detailed supervision for training process reward models.

Empirical results demonstrate the superiority of process supervision for mathematical reasoning. On the MATH dataset, using a PRM to select among candidate solutions achieved 78.2% accuracy, compared to 72.4% for an Outcome Reward Model (ORM) and 69.6% for majority voting [

43]. This substantial improvement suggests that process supervision enables more effective identification of correct reasoning paths.

Beyond performance benefits, process supervision offers important alignment advantages. By directly rewarding models for following human-approved reasoning processes, PRMs encourage interpretable reasoning that can be verified step-by-step. This contrasts with outcome supervision, which may inadvertently reward models for correct answers obtained through opaque or unreliable reasoning.

5.3. Self-Taught Reasoning

Self-taught reasoning approaches enable models to improve their reasoning capabilities through self-generated training data, reducing dependence on expensive human annotation. The Self-Taught Reasoner (STaR) method [

74] exemplifies this paradigm through an iterative bootstrapping process.

STaR operates through repeated cycles of generation, filtering, and fine-tuning. The iterative process can be formalized as:

where

r is a rationale sampled from

that leads to the correct answer

. In each iteration, the model generates rationales for a large set of problems using few-shot prompting. Rationales that lead to correct answers are collected as training data, while those leading to incorrect answers are discarded. Additionally, for problems the model fails to solve, a rationalization step generates new rationales given the correct answer:

This provides training signal for difficult problems. The model is then fine-tuned on the collected rationales, and the process repeats.

Figure 13 illustrates the STaR iterative bootstrapping process.

This iterative approach enables progressive improvement in reasoning capability. Starting from few-shot performance, STaR models can bootstrap to substantially higher accuracy through successive iterations. On CommonsenseQA, STaR improved over the few-shot baseline by 35.9% and over a baseline fine-tuned without rationales by 12.5% [

74].

The effectiveness of STaR depends on the initial model having sufficient capability to generate some correct solutions. For very difficult problems or insufficiently capable base models, the bootstrapping process may fail to make progress. Additionally, domains with high chance performance (such as binary classification) can introduce noise through rationales that are correct by chance despite flawed reasoning.

Subsequent work has extended the self-improvement paradigm in various directions . Rejection sampling fine-tuning generates many candidate solutions per problem and fine-tunes on the correct ones. Iterative distillation uses a stronger model to generate training data for a weaker model, which is then further refined. These approaches collectively demonstrate the power of using LLM-generated data to enhance LLM reasoning.

5.4. Constitutional AI and RLAIF

Constitutional AI (CAI) [

87] introduces an alternative to pure human feedback by using AI feedback to guide model training. The approach defines a set of principles (a “constitution”) that the model should follow, then uses the model itself to evaluate and revise responses according to these principles.

The CAI training process involves two phases. In the supervised phase, the model critiques its own responses according to constitutional principles and generates revised responses that better adhere to these principles. The revised responses serve as training data for supervised fine-tuning. In the RL phase, a preference model is trained on AI-generated preference labels rather than human labels, and this preference model guides policy optimization.

For reasoning tasks, constitutional principles can encode expectations about logical consistency, step-by-step reasoning, and acknowledgment of uncertainty. By training models to critique and revise their own reasoning according to such principles, CAI can promote more reliable and transparent reasoning behaviors.

The shift from human feedback to AI feedback, termed Reinforcement Learning from AI Feedback (RLAIF), offers significant scalability advantages. Generating AI feedback is faster and cheaper than collecting human annotations, enabling training on larger and more diverse problem sets. However, AI feedback may encode biases present in the feedback model and may not capture all aspects of human preferences.

5.5. Reasoning-Specialized Models

The culmination of training-based reasoning research is the development of models specifically designed and trained for reasoning tasks. OpenAI’s o1 model [

68] and DeepSeek-R1 [

75] represent the current frontier of this approach.

OpenAI o1 was trained using large-scale reinforcement learning to perform extended chain-of-thought reasoning. The training objective can be conceptualized as:

where

is the space of reasoning chains,

is the answer derived from chain

r, and

penalizes excessively long reasoning. Unlike standard models that generate immediate responses, o1 produces lengthy reasoning chains (using “reasoning tokens”) before arriving at final answers. The training process taught the model to recognize and correct its own mistakes, decompose difficult problems, and try alternative approaches when initial strategies fail.

Table 9 compares the performance of reasoning-specialized models across key benchmarks.

The results of this training are striking. On the American Invitational Mathematics Examination (AIME), o1 achieved 74% accuracy with single sampling, compared to 12% for GPT-4o [

68]. With consensus over 64 samples, accuracy increased to 83%. On competition-level coding problems, o1 achieved performance competitive with human experts, suggesting that sustained reasoning training can enable near-human performance on challenging intellectual tasks.

DeepSeek-R1 [

75] demonstrates that reasoning capabilities can emerge through reinforcement learning without supervised fine-tuning on reasoning data. By training directly with RL from a base model, DeepSeek-R1-Zero developed sophisticated reasoning behaviors including self-verification, reflection, and extended chain-of-thought generation. DeepSeek-R1, which incorporates additional cold-start data, achieves performance comparable to o1 across mathematics, coding, and reasoning benchmarks while being released as an open-source model.

The architecture underlying DeepSeek-R1, a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) model with 671 billion total parameters and 37 billion active parameters, illustrates how architectural innovations can complement training advances . MoE architectures enable scaling to very large parameter counts while maintaining computational efficiency, supporting the intensive training required for reasoning specialization.

Figure 14 illustrates the extended reasoning process employed by o1-style models.

5.6. Comparative Analysis

Table 10 provides a comparative overview of training-based reasoning methods across key dimensions including supervision type, computational requirements, and target reasoning capabilities.

Each approach offers distinct trade-offs. RLHF provides broad alignment but sparse reasoning feedback. PRMs offer fine-grained reasoning supervision but require expensive annotation. Self-improvement methods reduce annotation costs but may plateau without external signal. Reasoning-specialized models achieve strong performance but require massive computational investment.

The emergence of o1 and DeepSeek-R1 suggests that the field is converging on a paradigm that combines large-scale reinforcement learning with extended chain-of-thought reasoning. However, even these advanced models exhibit persistent error rates on long-horizon tasks, motivating the multi-agent approaches discussed in the following section.

6. Multi-Agent Systems for Reasoning

Multi-agent systems represent a paradigm shift in LLM reasoning, moving from optimizing individual model performance to orchestrating collaborative intelligence among multiple model instances. This section examines the landscape of multi-agent reasoning approaches, from collaborative frameworks and debate mechanisms to the breakthrough concept of Massively Decomposed Agentic Processes that enables million-step reasoning with zero errors.

6.1. Foundations of Multi-Agent LLM Systems

The multi-agent paradigm for LLM reasoning is grounded in the observation that while individual model instances exhibit persistent error rates, ensembles of models can achieve greater reliability through appropriate coordination mechanisms [

76]. The error reduction principle can be formalized as follows. Given

k independent agents each with error probability

p, the ensemble error under majority voting is:

For , this probability decreases exponentially with k, providing the theoretical foundation for multi-agent reliability. This principle has deep roots in distributed computing, ensemble learning, and social choice theory, all of which inform the design of multi-agent LLM systems.

The fundamental components of multi-agent LLM systems include agents (individual LLM instances, potentially with different prompts, parameters, or specializations), communication protocols (mechanisms for agents to share information and coordinate actions), aggregation methods (strategies for combining outputs from multiple agents), and orchestration layers (systems that manage agent coordination and task allocation). The design of each component significantly impacts system performance, reliability, and computational efficiency.

Multi-agent systems offer several potential advantages over single-agent approaches. First, they enable error reduction through redundancy, as multiple agents can catch errors that any single agent might miss. Second, they support specialization, allowing different agents to focus on different aspects of a complex task. Third, they provide natural parallelization, as independent subtasks can be processed concurrently. Fourth, they offer robustness against individual agent failures, as the system can continue functioning even if some agents produce erroneous outputs.

Table 11 summarizes the key characteristics of major multi-agent frameworks.

6.2. Collaborative Agent Frameworks

AutoGen [

77] introduced a flexible framework for building applications with multiple LLM agents engaged in multi-turn conversation. The framework allows developers to define agents with different roles, capabilities, and behaviors, and to specify conversation patterns that enable collaborative problem-solving.

A key innovation in AutoGen is the concept of conversable agents that can receive messages, generate responses, and take actions based on configurable capabilities. Agents can be humans, LLMs, or combinations thereof, enabling human-in-the-loop workflows. The framework supports various conversation patterns, from two-agent dialogues to complex multi-agent group chats with dynamic speaker selection.

AutoGen has demonstrated success across diverse applications, including code generation and debugging, mathematical problem solving, and interactive data analysis [

79]. The framework’s flexibility enables rapid prototyping of multi-agent systems while its extensibility supports integration with external tools and knowledge sources [

88,

89].

Figure 15 illustrates a typical AutoGen conversation pattern for collaborative problem-solving.

MetaGPT [

81] takes a structured approach to multi-agent collaboration by encoding Standardized Operating Procedures (SOPs) into the framework. Inspired by human organizational practices, MetaGPT defines specialized roles (Product Manager, Architect, Engineer, QA) and structured workflows that mirror professional software development processes.

The core innovation of MetaGPT is the materialization of SOPs as prompt sequences that guide agent interactions. Rather than allowing free-form conversation, MetaGPT constrains interactions to follow defined procedures, with each role producing specific artifacts (requirements documents, architecture diagrams, code) that serve as inputs for subsequent roles. This structure reduces ambiguity and ensures systematic progress toward project completion.

On software development benchmarks, MetaGPT achieved remarkable results, with 100% task completion rate and 85.9% pass@1 on code generation [

81]. The success of MetaGPT suggests that importing organizational structures and workflows from human practice can significantly enhance multi-agent LLM system performance.

Figure 16 illustrates the MetaGPT software development pipeline with role-based specialization.

6.3. Debate and Verification Mechanisms

Multi-agent debate represents an approach where multiple LLM instances argue different positions and attempt to convince each other of the correct answer. The intuition is that flawed reasoning may be exposed through adversarial examination, allowing the truth to emerge from the debate process.

In a typical debate setup, two or more agents generate initial responses to a question, then take turns critiquing each other’s responses and defending their own positions. The debate dynamics can be modeled as:

where

is agent

i’s position at round

t,

are critiques from other agents, and

q is the original question. The debate continues for a fixed number of rounds or until consensus is reached. A judge (which may be another LLM or human) then evaluates the debate and determines the final answer through:

where

represents the debate history for agent

i.

Debate mechanisms have shown promise for improving truthfulness and reducing hallucinations. When agents must defend their claims against skeptical opposition, they are incentivized to provide stronger evidence and more rigorous reasoning. However, debates can also lead to stalemates when both sides produce plausible-sounding but ultimately incorrect arguments.

Verification through self-consistency and cross-agent validation represents a complementary approach. Rather than debating to reach consensus, agents independently generate solutions, and the solutions are compared for agreement. Disagreement signals potential errors that warrant further investigation, while agreement provides evidence of correctness.

Reflexion [

90] introduces verbal reinforcement learning where agents reflect on their failures and generate textual feedback to improve subsequent attempts. Unlike traditional RL that updates model weights, Reflexion maintains a memory of past failures and reflections that inform future actions. This episodic memory enables rapid adaptation without parameter updates.

On reasoning and decision-making tasks, Reflexion demonstrated substantial improvements through iterative self-reflection. On HotPotQA, Reflexion improved over strong baselines by 20%, while on ALFWorld decision-making tasks, it achieved 22% improvement over previous approaches [

90]. These results suggest that explicit reflection on errors is a powerful mechanism for reasoning improvement.

The Reflexion update rule can be formalized as:

where

is the episodic memory at trial

t, and the reflection function generates textual insights from the failed trajectory.

Figure 17 illustrates the Reflexion self-improvement loop.

6.4. MAKER: Massively Decomposed Agentic Processes

The MAKER framework [

52] represents a breakthrough in long-horizon LLM reasoning, demonstrating for the first time the ability to complete tasks with over one million LLM steps with zero errors. This achievement, which seemed out of reach given persistent per-step error rates in existing systems, is enabled by the combination of extreme task decomposition and multi-agent error correction.

The core insight underlying MAKER is that any per-step error rate, no matter how small, will eventually cause failure in sufficiently long sequential processes. However, if tasks can be decomposed into subtasks that are simple enough for focused microagents to solve reliably, and if multi-agent voting can correct the residual errors at each step, then reliable long-horizon execution becomes possible.

Figure 18.

Schematic of the MAKER approach. A complex task is decomposed into minimal subtasks. Each subtask is processed by multiple microagents whose outputs are aggregated through voting to ensure correctness.

Figure 18.

Schematic of the MAKER approach. A complex task is decomposed into minimal subtasks. Each subtask is processed by multiple microagents whose outputs are aggregated through voting to ensure correctness.

MAKER implements this insight through several key design choices. First, extreme decomposition breaks tasks into the smallest meaningful units that can be addressed by focused microagents. For the Towers of Hanoi benchmark, each individual disk move is treated as a separate subtask. This extreme granularity ensures that each subtask is simple enough for reliable solution.

Second, specialized microagents are designed for specific subtask types. Rather than using general-purpose prompts, microagents receive focused prompts tailored to their particular role. This specialization reduces the cognitive load on each agent and increases reliability.

Third, multi-agent voting aggregates responses from multiple microagents for each subtask. When agents agree, the consensus answer is accepted. When agents disagree, the system can apply additional verification strategies or request more agent opinions. The voting mechanism effectively filters out random errors that might occur in any single agent.

Fourth, the orchestration layer manages the overall process, decomposing tasks, dispatching subtasks to microagents, aggregating responses, and sequencing the results into coherent solutions. This layer provides the glue that enables the microagent ensemble to function as a coherent problem-solving system.

The results on the Towers of Hanoi benchmark are striking. While state-of-the-art reasoning models like o1 fail beyond a few hundred steps, MAKER successfully completed instances requiring over one million steps with zero errors. This represents a qualitative leap in capability, demonstrating that with appropriate architecture, LLM-based systems can achieve reliability far beyond what any individual model can attain.

6.5. Theoretical Analysis of Error Correction

The success of MAKER can be understood through the lens of error-correcting codes and distributed consensus. Consider a system where each microagent produces a correct output with probability

, and where

k agents are used for each subtask. With simple majority voting, the probability of an incorrect aggregate output is approximately:

For small p and moderate k, this probability can be made arbitrarily small.

For example, with (1% per-agent error rate) and agents, the voting error rate drops to approximately . With this enhanced per-step reliability, a million-step task has a reasonable probability of completing without error. The key insight is that voting provides exponential error reduction as the number of agents increases, enabling the scaling that would be impossible with single-agent approaches.

The expected number of errors in an

N-step task with voting can be bounded as:

For sufficiently large k, this approaches zero even for very large N.

Figure 19 illustrates the dramatic error reduction achieved through multi-agent voting.

However, this analysis assumes independent errors across agents. In practice, agents may make correlated errors due to shared training data, similar reasoning patterns, or systematic biases [

91]. The design of microagents and prompts must account for these correlations, potentially through diversity-promoting mechanisms such as varied prompts, different sampling temperatures, or even different underlying models. Understanding uncertainty quantification in AI systems is critical for designing robust multi-agent architectures.

6.6. Implications for Organizational-Scale Problems

The MAKER framework has profound implications for the application of LLMs to problems at organizational and societal scales. Human organizations routinely execute processes involving millions of dependent steps: managing supply chains, coordinating construction projects, running scientific research programs. The ability of MAKER to reliably complete million-step tasks suggests that similar reliability might be achievable for complex organizational processes.

Several challenges must be addressed to realize this potential. First, real-world tasks involve more complex decompositions than Towers of Hanoi, requiring sophisticated techniques for identifying subtask boundaries and dependencies. Second, many organizational tasks involve interaction with the physical world or human actors, introducing delays and uncertainties beyond pure computation. Third, the coordination overhead of multi-agent systems must be managed to maintain practical efficiency.

Despite these challenges, MAKER represents a significant step toward AI systems capable of reliable operation at human-organizational scales. The paradigm shift from improving individual model capability to designing effective multi-agent architectures opens new research directions and practical possibilities that were previously inaccessible.

7. Experimental Analysis

This section synthesizes empirical findings from the literature to provide a comprehensive analysis of LLM reasoning performance across major benchmarks. We examine performance trends, compare different reasoning approaches, and analyze the factors that contribute to success and failure in reasoning tasks.

7.1. Benchmark Performance Overview

Table 12 summarizes the performance of representative models and methods across major reasoning benchmarks. The data reflects significant progress over recent years, with the most advanced reasoning-specialized models approaching or exceeding human-level performance on several benchmarks.

Several patterns emerge from this comparison. First, reasoning-specialized models (o1, DeepSeek-R1) substantially outperform general-purpose models on challenging mathematical benchmarks like MATH and AIME. The performance improvement can be quantified as:

For AIME, this yields a 517% relative improvement from GPT-4 (12%) to o1 (74%), suggesting that specialized reasoning training enables qualitative improvements on the most difficult problems.

Second, Chain-of-Thought prompting provides consistent but moderate improvements over standard prompting across models [

36,

92]. The gains are more substantial for larger, more capable models, consistent with the observation that CoT is an emergent ability that manifests at scale [

3,

8].

Third, Self-Consistency (SC) provides additional gains beyond single-sample performance, with the improvement scaling with the number of samples [

20,

83]. The o1 model with 64-sample Self-Consistency achieves 83% on AIME, approaching human expert performance.

Fourth, performance on code generation benchmarks (HumanEval) shows a different pattern, with Claude 3 Opus and o1 achieving the highest scores. This may reflect differences in training data composition and optimization objectives across model families. Domain-specific benchmarks, such as those in medical tasks , reveal additional performance variations that highlight the importance of task-specific evaluation.

Figure 20 provides a visual comparison of model performance across reasoning benchmarks.

7.2. Performance on Long-Horizon Tasks

While the benchmarks in

Table 12 primarily assess reasoning within relatively short contexts, the critical challenge of long-horizon reasoning reveals fundamental limitations of current approaches.

Table 13 presents performance analysis on extended sequential reasoning tasks.

The Towers of Hanoi benchmark provides a controlled environment for studying long-horizon performance because solutions can be verified algorithmically and task complexity can be scaled precisely. For

n disks, the optimal solution requires:

allowing precise scaling of task complexity. The results reveal exponential performance degradation for single-model approaches, following:

where

p is the per-step error rate. Even o1, with its enhanced reasoning capabilities, fails on the majority of 500-step tasks.

In contrast, MAKER maintains near-perfect accuracy across all tested scales. At 500 steps, where o1 succeeds only 35% of the time, MAKER achieves 99.6% accuracy. This dramatic difference underscores the potential of multi-agent approaches for reliable long-horizon reasoning.

The scaling analysis extends to even longer horizons. While single-model approaches become essentially unusable beyond approximately 1,000 steps, MAKER successfully completed instances requiring over one million steps with zero observed errors [

52]. This qualitative leap in capability suggests that the MDAP paradigm addresses a fundamental limitation of single-model reasoning.

Figure 21 illustrates the performance scaling behavior of different approaches.

7.3. Analysis of Reasoning Errors

Understanding the types and causes of reasoning errors provides insight into the limitations of current approaches and opportunities for improvement. Analysis of error patterns across benchmarks reveals several common failure modes.

Table 14 categorizes the primary error types observed in LLM reasoning.

Calculation errors occur when models make mistakes in arithmetic operations despite correctly understanding the problem structure. These errors are particularly common in mathematical reasoning and can propagate through multi-step solutions. Program-based approaches (PoT, PAL) largely eliminate calculation errors by delegating computation to reliable interpreters.

Logical errors involve violations of valid inference rules or the introduction of unjustified steps. These may arise from pattern matching on superficially similar but logically distinct problems, or from gaps in the model’s understanding of logical principles. Chain-of-Thought and verification approaches can help expose logical errors by making reasoning explicit.

Comprehension errors stem from misunderstanding problem statements, misidentifying relevant information, or failing to recognize problem constraints. These errors are often triggered by ambiguous language, unusual problem formulations, or requirements that differ from training distribution.

Hallucination errors involve the introduction of fabricated facts, equations, or reasoning steps that have no basis in the problem or the model’s knowledge. Hallucinations represent a particularly pernicious failure mode because they can appear confident and plausible while being fundamentally incorrect.

Attention errors occur when models lose track of relevant information over long contexts or fail to connect information from different parts of a problem. These errors become more prevalent as problem complexity and context length increase, contributing to the degradation observed on long-horizon tasks.

7.4. Cost-Accuracy Trade-Offs

Reasoning methods involve trade-offs between computational cost and accuracy that are important for practical deployment.

Figure 22 illustrates these trade-offs for representative approaches.

Several observations emerge from this analysis. First, all approaches show diminishing returns as compute budget increases, suggesting inherent accuracy ceilings for each method. Second, MAKER achieves higher accuracy at comparable compute budgets, particularly for tasks requiring high reliability. Third, the gap between approaches widens at higher accuracy targets, with MAKER maintaining its advantage as reliability requirements increase.

The optimal choice of method depends on application requirements. For applications tolerating moderate error rates, single-sample inference from capable models may be most efficient. For applications requiring high reliability, the additional cost of multi-agent approaches may be justified by their superior accuracy.

7.5. Generalization Analysis

A critical question for LLM reasoning is the extent to which methods generalize beyond their training and evaluation distributions. Analysis of generalization behavior reveals both capabilities and limitations.

Compositional generalization refers to the ability to solve novel problems by composing familiar components in new ways. The compositional complexity of a problem can be characterized by:

where

are the compositional components,

measures distance from training distribution

, and

are component weights. Least-to-Most prompting demonstrates strong compositional generalization on the SCAN benchmark, achieving near-perfect accuracy on long compositions after training on short examples [

28]. However, this success does not uniformly transfer across tasks, and many methods struggle with compositions that differ significantly from training examples.

Distribution shift affects reasoning performance when test problems differ systematically from training or demonstration examples . Models trained primarily on competition mathematics may struggle with applied problems from different domains, even if the underlying mathematical techniques are similar. Active learning methods can help improve data utilization and model performance under distribution shift. Prompt-based approaches can provide some robustness through careful example selection, but significant distribution shifts typically degrade performance.

Scaling generalization concerns whether methods that work at small scales continue to work at larger scales. The error propagation problem represents a fundamental failure of scaling generalization for single-model approaches: methods that achieve high accuracy on short reasoning chains fail catastrophically on long chains. MAKER’s success at million-step scales suggests that appropriate architectural choices can address this limitation.

Figure 23 summarizes the generalization characteristics of different reasoning approaches.

8. Discussion

This section synthesizes the key insights emerging from our survey of LLM reasoning, examining the implications of current progress and persistent challenges, and discussing the broader context within which LLM reasoning research is situated.

8.1. Key Insights and Lessons Learned

The rapid progress in LLM reasoning over the past several years yields several important insights that inform both research directions and practical applications.

First, explicit reasoning structure dramatically improves performance. The success of Chain-of-Thought prompting and its variants demonstrates that encouraging models to generate intermediate steps before final answers unlocks latent reasoning capabilities [

36,

37]. This insight has proven remarkably robust across models, tasks, and domains, suggesting that explicit reasoning structure is a fundamental enabler of complex problem-solving in LLMs.

Second, decomposition is a powerful principle for handling complexity. From Least-to-Most prompting to the extreme decomposition of MAKER, methods that break complex problems into simpler components consistently outperform monolithic approaches. This principle echoes classical strategies in computer science (divide-and-conquer) and cognitive science (chunking), suggesting deep connections between human and machine problem-solving.

Third, verification and redundancy enable reliability. Self-Consistency, debate mechanisms, and multi-agent voting all leverage redundancy to filter out errors. The mathematical analysis of error correction in MAKER demonstrates that sufficient redundancy can achieve arbitrarily high reliability, a insight with profound implications for deploying LLMs in high-stakes applications .

Fourth, training and prompting are complementary. The most capable systems combine specialized training (as in o1 and DeepSeek-R1) with sophisticated prompting and inference-time computation. Neither approach alone achieves optimal performance; rather, they represent different ways of investing resources that can be combined synergistically.

Fifth, scale alone is insufficient for reliable reasoning. Despite the remarkable capabilities of large models, persistent error rates prevent scaling to long-horizon tasks without additional mechanisms for error correction. This finding suggests that qualitative architectural innovations, not just quantitative scaling, are required for the next generation of reasoning systems.

8.2. The Error Propagation Barrier

The error propagation problem represents perhaps the most fundamental barrier to deploying LLM reasoning at organizational scales. Even with single-step error rates below 1%, sequential processes with thousands or millions of steps will almost certainly fail without error correction.

Understanding this barrier requires appreciating its mathematical inevitability. For a process with n sequential steps and per-step success probability p, the overall success probability is . Even for , we have , , and . No incremental improvement in per-step reliability can overcome this exponential decay for sufficiently long processes.

The MAKER breakthrough demonstrates that the error propagation barrier is not insurmountable. By combining extreme decomposition with multi-agent error correction, MAKER achieves effective per-step reliability sufficient for million-step processes. This achievement suggests a path forward: rather than seeking ever-lower individual error rates, focus on architectural designs that enable effective error correction.

This insight has implications beyond LLM reasoning. Any system based on sequential processing with non-zero error rates faces similar barriers at sufficient scale. The principles of decomposition and error correction demonstrated by MAKER may find application in other AI systems, robotic process automation, and complex organizational workflows.

8.3. Relationship to Human Reasoning

LLM reasoning research invites comparison with human cognitive processes, though such comparisons must be made carefully . Several parallels and distinctions merit discussion.

Like humans, LLMs benefit from making reasoning explicit. Human problem-solvers often talk through problems, write notes, or draw diagrams to externalize their thinking. Chain-of-Thought prompting can be seen as encouraging similar externalization in LLMs [

93,

94]. The effectiveness of this approach for both humans and machines suggests that explicit reasoning scaffolds serve similar functions across different cognitive substrates.

Unlike humans, LLMs lack persistent memory and consistent identity across interactions. Each LLM inference is stateless, with no inherent memory of previous reasoning episodes. Approaches like Reflexion attempt to simulate episodic memory through prompt engineering, but they remain fundamentally different from human continuous learning and memory consolidation.

The multi-agent paradigm may be more analogous to organizational cognition than individual cognition. Organizations solve complex problems through division of labor, specialized roles, and aggregation mechanisms—precisely the elements present in frameworks like MetaGPT and MAKER. This parallel suggests that insights from organizational theory and distributed systems may be particularly relevant for advancing multi-agent LLM research.

8.4. Safety and Alignment Considerations

Advances in LLM reasoning raise important safety and alignment considerations [

95]. More capable reasoning systems are potentially more useful but also more dangerous if misaligned or misused.

On the beneficial side, improved reasoning can support better safety mechanisms. Process supervision with PRMs encourages interpretable step-by-step reasoning that can be audited for alignment with human values. Self-critique and reflection capabilities enable models to recognize and avoid harmful outputs. Explicit reasoning chains provide transparency that facilitates human oversight.

On the concerning side, enhanced reasoning capabilities could enable more sophisticated adversarial behaviors. Models that can reason through complex plans might find creative ways to circumvent safety guardrails. Long-horizon reasoning, if applied to harmful goals, could enable more damaging outcomes than simple reactive systems.

The multi-agent paradigm introduces additional considerations. Emergent behaviors in multi-agent systems can be difficult to predict and control. Voting mechanisms assume independent errors, but systematic biases might lead to incorrect consensus. The orchestration layer represents a critical control point that must be carefully designed to maintain safety guarantees.

Constitutional AI and related approaches [

87] offer frameworks for addressing these concerns by encoding safety constraints into the reasoning process itself. Extending these approaches to multi-agent systems, ensuring that both individual agents and their collective behavior remain aligned, represents an important direction for future research.

8.5. Computational Economics

The economics of LLM reasoning involve trade-offs between computational cost, accuracy, and latency that have significant practical implications . Understanding these trade-offs is essential for deploying reasoning systems effectively.

Inference-time computation (test-time compute) emerges as an alternative to training-time computation for improving reasoning performance. Self-Consistency, Tree of Thoughts, and multi-agent approaches all invest more computation at inference time to achieve higher accuracy. The optimal allocation between training and inference depends on deployment patterns: systems handling many queries may prefer more training investment, while systems handling few high-stakes queries may prefer inference-time approaches.

Multi-agent systems multiply computational costs but can achieve reliability levels impossible for single-agent approaches. The MAKER analysis shows that for tasks requiring very high reliability over long horizons, multi-agent costs are justified—indeed, required—to achieve acceptable performance. For less demanding applications, simpler approaches may be more cost-effective.

Latency considerations often favor simpler approaches. While multi-sample voting and multi-agent coordination improve accuracy, they also increase response time. Applications with strict latency constraints may need to accept lower reliability, highlighting the importance of understanding application requirements when selecting reasoning approaches.

The development of more efficient inference methods, including speculative decoding, model distillation, and efficient voting schemes, can shift these trade-offs favorably . Continued research on inference efficiency is essential for democratizing access to advanced reasoning capabilities. Advances in generative models and efficient representations can enable more cost-effective reasoning systems.

9. Future Research Directions

While significant progress has been made in LLM reasoning, numerous open challenges and unexplored directions remain. This section identifies key areas where future research can advance the field toward more capable, reliable, and useful reasoning systems.

9.1. Compositional Generalization

Despite progress on benchmark tasks, LLMs continue to struggle with compositional generalization—the ability to solve novel problems by combining familiar components in new ways [

96,

97]. This limitation becomes apparent when models encounter problems that require known techniques in unfamiliar configurations or at scales beyond training examples.

Future research should explore methods for improving compositional generalization in reasoning. Modular architectures that explicitly represent reusable reasoning components could enable more flexible composition. Curriculum learning strategies that systematically vary problem complexity during training may encourage more robust generalization. Formal methods for reasoning composition, drawing on program synthesis and theorem proving, could provide stronger guarantees of correct generalization.

Understanding the mechanisms underlying compositional reasoning in LLMs is equally important. Research on how transformers represent and manipulate compositional structures can inform architectural improvements. Analysis of failure modes in compositional generalization can guide targeted interventions to address specific weaknesses.

9.2. Hybrid Neurosymbolic Reasoning

Current LLM reasoning operates primarily through soft pattern matching in learned representations, lacking the formal guarantees provided by symbolic systems . Hybrid approaches that combine neural flexibility with symbolic rigor represent a promising direction for more reliable reasoning.

Neurosymbolic integration can take multiple forms [

93,

94,

98]. LLMs can generate formal specifications that are verified by symbolic systems, ensuring logical validity of reasoning steps. Symbolic planners can provide high-level reasoning structure while LLMs handle natural language understanding and generation. Program synthesis approaches like PAL and PoT [

85,

99,

100] already demonstrate the value of combining LLM capabilities with symbolic execution.

Advances in this direction require addressing the interface between neural and symbolic components. Natural language to formal language translation remains imperfect, potentially introducing errors at the boundary. Development of more robust translation methods, or architectures that operate natively across both modalities, could enable tighter integration.

9.3. Scaling Multi-Agent Architectures

The success of MAKER on million-step tasks motivates further investigation of multi-agent architectures for reasoning. Several dimensions of scaling merit exploration.

Scaling to more complex task structures beyond the well-defined decomposition of Towers of Hanoi requires advances in automatic task decomposition. Methods for identifying subtask boundaries, representing dependencies, and coordinating parallel execution in general domains remain underdeveloped. Learning-based approaches that discover effective decompositions from experience could enable broader application.

Scaling agent diversity beyond homogeneous microagents could leverage complementary strengths of different models or prompting strategies [

78,

80]. Heterogeneous agent ensembles, combining models with different architectures, training data, or specializations, might achieve greater robustness against correlated errors. Methods for managing and optimizing diverse agent populations present interesting research opportunities. Knowledge distillation techniques [

101,

102,

103] offer potential pathways for creating specialized lightweight agents.

Scaling coordination mechanisms beyond simple voting could enable more sophisticated collective reasoning. Weighted voting based on agent confidence or track record, iterative refinement through agent dialogue, and hierarchical organization with specialized meta-agents represent directions for more sophisticated coordination.

9.4. Continual Learning and Adaptation

Current LLM reasoning systems lack the ability to learn from experience during deployment, limiting their ability to improve or adapt to new domains . Developing methods for continual learning in reasoning systems could enable substantial improvements in practical utility.

Episode-level learning, as demonstrated by Reflexion, provides a starting point but relies on prompt-based memory that has limited capacity and no permanent consolidation. Methods for more durable learning from reasoning episodes, whether through model updates or external memory systems, could enable genuine improvement over deployment lifetime.

Domain adaptation represents a particularly important challenge. Organizations often need reasoning systems that work effectively in specialized domains with limited examples. Few-shot adaptation methods, potentially leveraging retrieval-augmented approaches, could enable more rapid specialization to new domains.

Meta-learning approaches that enable models to learn how to learn new reasoning skills could provide fundamental improvements in adaptability. Research on meta-reasoning—reasoning about reasoning strategies themselves—may yield insights applicable to continual learning.

9.5. Interpretability and Transparency

While explicit reasoning chains provide more transparency than direct answer generation, significant challenges remain in making LLM reasoning truly interpretable . Users cannot easily verify whether generated reasoning faithfully represents the model’s internal computations or is post-hoc rationalization.

Mechanistic interpretability research aims to understand the internal representations and computations underlying model behavior. Applying these techniques to reasoning tasks could reveal how models represent logical structure, track state across reasoning steps, and detect errors. Such understanding could inform both improvements to reasoning capability and development of monitoring systems.

Faithful explanations that accurately reflect model decision-making, rather than plausible-sounding but potentially misleading rationalizations, remain elusive. Research on methods for generating and verifying explanation faithfulness is essential for deploying reasoning systems in settings where transparency is required.

Interactive explanation systems that allow users to probe reasoning, request elaboration, or test counterfactuals could provide richer understanding than static reasoning chains. Development of such systems requires advances in both explanation generation and user interface design.

9.6. Multimodal Reasoning

While this survey has focused primarily on text-based reasoning, extending reasoning capabilities to multimodal settings is essential for many practical applications . Visual reasoning, mathematical diagram understanding, and reasoning about physical systems all require integrating multiple modalities.

Current multimodal models show promising reasoning capabilities but remain limited compared to their text-only counterparts on complex reasoning tasks. Research on how to effectively combine chain-of-thought style reasoning with visual or other modalities could enable new applications in scientific discovery, engineering design, and physical problem-solving.

The development of multimodal benchmarks specifically designed to test reasoning capabilities, beyond simple visual question answering, is needed to drive progress in this area. Benchmarks requiring genuine multimodal reasoning—where neither modality alone suffices—would provide clearer evaluation of integrated reasoning capabilities.

9.7. Theoretical Foundations

Despite empirical progress, theoretical understanding of LLM reasoning remains limited. Developing stronger theoretical foundations could guide research more effectively and provide guarantees important for deployment.

Computational complexity analysis of reasoning tasks can characterize the inherent difficulty of problems and inform expectations for model performance. Understanding which reasoning tasks are tractable for LLMs, and why, could guide benchmark development and application selection.

Learning-theoretic analysis of how reasoning capabilities emerge from training could inform curriculum design and data requirements. Understanding what aspects of pretraining data contribute to reasoning capability could enable more efficient training.

Formal models of multi-agent reasoning, drawing on distributed systems theory and social choice theory, could provide frameworks for analyzing and designing coordination mechanisms. Such frameworks could help establish reliability guarantees for multi-agent reasoning systems.

9.8. Real-World Deployment Challenges

Deploying LLM reasoning systems in real-world settings involves challenges beyond pure reasoning capability [

95]. Addressing these challenges is essential for translating research progress into practical value.

Robustness to adversarial inputs, including prompt injection attacks and intentionally misleading inputs, is critical for deployed systems . Research on robust reasoning that maintains correctness even under adversarial conditions is needed for security-sensitive applications.

Integration with existing workflows and systems requires consideration of interfaces, latency, and reliability requirements. Understanding how to effectively combine LLM reasoning with human oversight, traditional software systems, and physical processes is essential for deployment.

Cost management at scale requires continued progress on inference efficiency and intelligent resource allocation . Systems that can dynamically adjust reasoning depth based on problem difficulty and importance could enable more efficient deployment. Hardware acceleration and trustworthy real-time decision support systems are critical enablers for scaling LLM reasoning to production environments.

10. Conclusion

This survey has provided a comprehensive examination of reasoning in Large Language Models, spanning from foundational prompting techniques to emerging massively decomposed agentic processes. Through our analysis, several key findings emerge that characterize the current state of the field and point toward future directions.

The taxonomy we developed organizes LLM reasoning approaches into three complementary paradigms: prompting-based methods that leverage in-context learning to elicit reasoning, training-based methods that internalize reasoning capabilities through specialized objectives, and multi-agent systems that achieve reliability through collaboration and error correction. Each paradigm offers distinct trade-offs in terms of accessibility, capability, and computational requirements, and the most effective solutions often combine elements from multiple paradigms.

Chain-of-Thought prompting and its variants have established that explicit reasoning structure is fundamental to unlocking complex problem-solving capabilities in LLMs. The simple insight that encouraging models to show their work dramatically improves performance has spawned a rich ecosystem of techniques, from Self-Consistency voting to Tree and Graph of Thoughts, each extending the core principle in different directions.

Training-based approaches have demonstrated that reasoning capabilities can be substantially enhanced through specialized learning objectives. Process reward models provide fine-grained supervision that guides models toward valid reasoning steps. Self-improvement methods like STaR enable bootstrapping of reasoning capabilities from minimal supervision. The development of reasoning-specialized models such as OpenAI’s o1 and DeepSeek-R1 represents the culmination of these efforts, achieving performance approaching human experts on challenging benchmarks.