1. Introduction

The Theory of Mind (ToM), otherwise known as mentalizing or mindreading, is the human ability to infer and reflect upon the mental and emotional states of oneself and others (Hiatt et al. 2011). ToM is at the core of human social intelligence, facilitating meaningful communication, enabling empathy, and providing the means by which we explain, predict, judge and influence one another’s behavior. ToM is essential for social intelligence, and developing agents with theory of mind is a requisite for efficient interaction and collaboration with humans. Thus, it is important to build a path forward for enabling agents with this type of reasoning, as well as methods for robustly assessing the of models’ theory of mind reasoning capabilities.

ToM is a fundamental human ability to infer the mental states, intentions, emotions, and beliefs of others, enabling the dynamic adjustment of behavior to social and environmental contexts (Baron-Cohen et al., 1985). This capability has been widely integrated into AI agent frameworks to enhance their interaction with humans (Langley et al., 2022).

In shared workspace settings, where close collaboration between humans and AI agents occurs, ToM becomes even more critical in shaping the AI agent’s framework (Hiatt et al., 2011). By leveraging ToM, AI agents can better understand, infer, and predict human behaviors, dynamically adapting their strategies to improve team performance and coordination.

From the human perspective, ToM also plays a pivotal role in how individuals perceive and interact with AI agents during collaboration (Gero et al., 2020). Humans build mental models of AI agents, attributing mental states and roles to them based on their expectations and the agents’ observed behavior. This reciprocal process underpins effective human-AI collaboration, where humans anticipate AI capabilities and roles while expecting them to align with their mental models.

At the core of what defines us as humans is the ToM concept: the ability to track other people’s mental states. The recent development of large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT has led to intense debate about the possibility that these models exhibit behavior that is indistinguishable from human behavior in theory of mind tasks.

There are systematic failures that limit the collaboration efficiency of LLM-based agents, and a prompt-engineering method is needed to mitigate those failures by incorporating explicit belief state representations about world knowledge in the model input.

Prior research has tested LLMs’ ToM via variants of text-based tests such as the unexpected transfer task (also known as Smarties Task) or unexpected contents task (also known as the “Maxi Task” or “Sally–Anne” Test) (Kosinski, 2023; Moghaddam and Honey 2023). Results indicate that leading LLMs can pass more than 90% of these test cases.

In contrast, Ullman (2023) found that LLMs struggle with complex ToM inferences involving communication or second-order beliefs. In the study of Li et al. (2024), ToM evaluations occur in the midst of an interactive team task, where the mental states of agents change dynamically with each interaction. As agents exchange information through communication at every timestamp, the complexity of reasoning increases, since agents’ mental states may be updated through both observations and communication. Ullman (2023)’s tests can be considered more challenging than the static text-based tests used in prior research.

The recent rise of LLMs made text-based tests of ToM particularly interesting. LLMs have already shown some successes across many challenging benchmarks and tasks designed to test various aspects of reasoning (Lewkowycz et al. 2022; Mahowald et al. 2023). While there are many cautionary voices that suggest such models may be acquiring formal rather than functional abilities, that has not stopped people from testing them on functional abilities as well, including ToM reasoning. While some of these tests offer a pessimistic evaluation (Sap et al. 2022), recent work by Kosinski (2023) applied variations on classic Theory-of-Mind tasks to several LLs, concluded that current.

ToM is not an innate ability. It is an empirically established fact that children develop a ToM at around the age of four (Baron-Cohen et al. 1999). It has been demonstrated that around this age, children are able to assign false beliefs to others, by having them undertake the Sally-Anne test. The child is told the following story, accompanied by dolls or puppets: Sally puts her ball in a basket and goes out to play; while she is outside Anne takes the ball from the basket and puts it in a box; then Sally comes back in. The child is asked where will Sally look for her ball. Children with a developed ToM are able to identify that Sally will look for her ball inside the basket, thus correctly assigning a false belief to the character, that they them selves know to be untrue.

During the 1980s, the ToM hypothesis of autism gained traction, which states that deficits in the development of ToM satisfactorily explain the main symptoms of autism. This hypothesis argues that the inability to process mental states leads to a lack of reciprocity in social interactions. Although a deficiency in the identification and interpretation of mental states remains uncontested as a cause of autism, it is no longer viewed as the only one, and the disorder is now studied as a complex condition involving a variety of cognitive and reasoning limitations (Askham 2022).

1.1. Current Limitations of LLMs in Handling ToM

The failure of inference hypothesis posits that LLMs struggle to generate inferences about the mental states of speakers, a critical component of theory of mind reasoning (Amirizaniani et al. 2024). For example, recognizing a faux pas in a given scenario requires contextual understanding that extends beyond the information explicitly encoded within the story. In tests of faux pas recognition, essential knowledge—such as the social norm that calling someone’s newly purchased curtains “horrible” is inappropriate—is not explicitly stated in the narrative. Yet, this implicit knowledge is crucial for accurately inferring the mental states of the characters. The inability to draw upon external, non-embedded information fundamentally limits GPT-4’s and similar models’ ability to compute such inferences reliably.

Even when language models demonstrate the ability to infer mental states, they often fail to resolve ambiguity between competing possibilities. This phenomenon mirrors the classic philosophical paradox of the “rational agent caught between two appetitive bales of hay,” where indecision leads to inaction. In this case, GPT models might correctly identify a faux pas as one of several plausible alternatives but fail to rank these possibilities by likelihood or importance. Instead, responses sometimes indicate uncertainty, suggesting that the speaker might not know or remember, yet present this as one hypothesis among many (Strachan et al., 2024). This behavior reflects a broader limitation: while the model can generate the correct inference, it often refrains from selecting or emphasizing it over less probable explanations.

Further complicating matters, even if one assumes that LLMs are capable of accurately inferring mental states and recognizing false beliefs or gaps in knowledge as the most likely explanation, these models often hesitate to commit to a single interpretation. This reluctance may stem from inhibitory mitigation processes built into the models, which prioritize cautious and noncommittal outputs. Such processes may cause the models to adopt an overly conservative stance, avoiding decisive answers even when they can generate the correct explanation.

These challenges highlight the dichotomy between the models’ ability to produce language that aligns with complex reasoning tasks and their limitations in applying this reasoning in a structured, human-like way. While LLMs are undeniably powerful in generating language, their reluctance to prioritize or commit to the likeliest inference undermines their ability to perform robustly in tasks requiring nuanced social understanding and contextual reasoning (Mohan et al. 2024). Addressing this conservatism and improving their ranking of alternatives will be crucial steps in advancing their theory of mind capabilities.

Sclar et al. (2024) demonstrate that LLMs struggle with basic state tracking—a foundational skill that underpins ToM reasoning. The ability to track mental states inherently depends on accurately maintaining representations of physical and contextual states, yet this proves to be a significant challenge for current models. Sclar et al. (2024)’s experiments further reveal that improving ToM reasoning during fine-tuning is not as simple as training on datasets that involve state tracking alone. Instead, the data must explicitly require the application of ToM principles, such as reasoning about others’ beliefs, intentions, or perspectives. Unfortunately, existing ToM training datasets rarely embody this necessary complexity, which may be a critical factor behind the lagging performance of LLMs in this area.

Moreover, there has been limited research on whether LLMs can implicitly leverage ToM knowledge to predict behavior or assess whether an observed behavior is rational. These abilities are essential for effective social interaction and for models to engage appropriately in environments requiring nuanced understanding of others’ actions and motives. Without these skills, LLMs remain constrained in their capacity to interpret or generate responses that align with human social reasoning.

The challenges extend beyond state tracking to encompass broader deficiencies in basic ToM capabilities. This includes the inability of LLMs to generalize beyond literal patterns or contexts in their training data, highlighting the importance of purpose-built datasets. Such datasets would need to emphasize tasks requiring explicit ToM reasoning, which is largely absent from text data found on the web or generated through random processes (Sclar et al., 2024). Addressing this gap will be crucial for the development of models capable of robust and meaningful ToM reasoning.

The mixed performance of LLMs, combined with their sensitivity to small perturbations in the prompts they receive, underscores serious concerns regarding their robustness and interpretability. Minor changes in a scenario, such as altering a character’s perceptual access or slightly rephrasing a prompt, can lead to drastic shifts in the model’s responses. This inconsistency reveals an unsettling fragility in their reasoning capabilities and suggests that their apparent successes may not stem from genuinely robust cognitive processes (Ullman, 2023). Instead, these successes may rely on shallow heuristics or pattern-matching techniques that fail to generalize across variations in input.

Even in cases where LLMs exhibit an impressive ability to solve cognitively demanding tasks—challenges that require intricate reasoning and are known to be difficult even for human adults (Apperly and Butterfill, 2009)—their performance on simpler, more straightforward tasks cannot be taken for granted. While these models may excel at tasks that involve complex rule-following or abstract problem-solving, they frequently falter when confronted with scenarios that require basic logic, consistency, or common-sense reasoning. This paradox highlights a critical gap between their surface-level performance and deeper cognitive understanding.

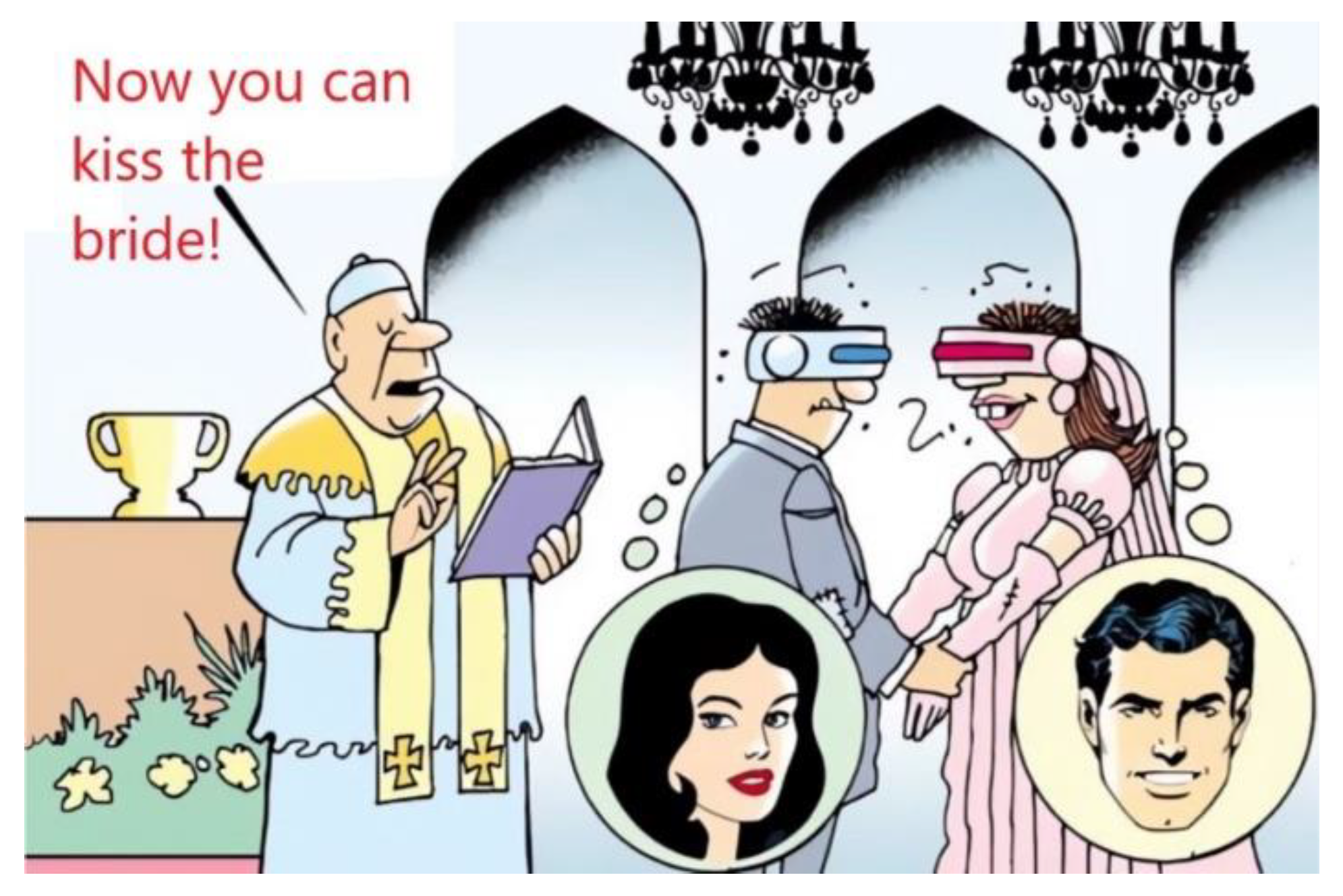

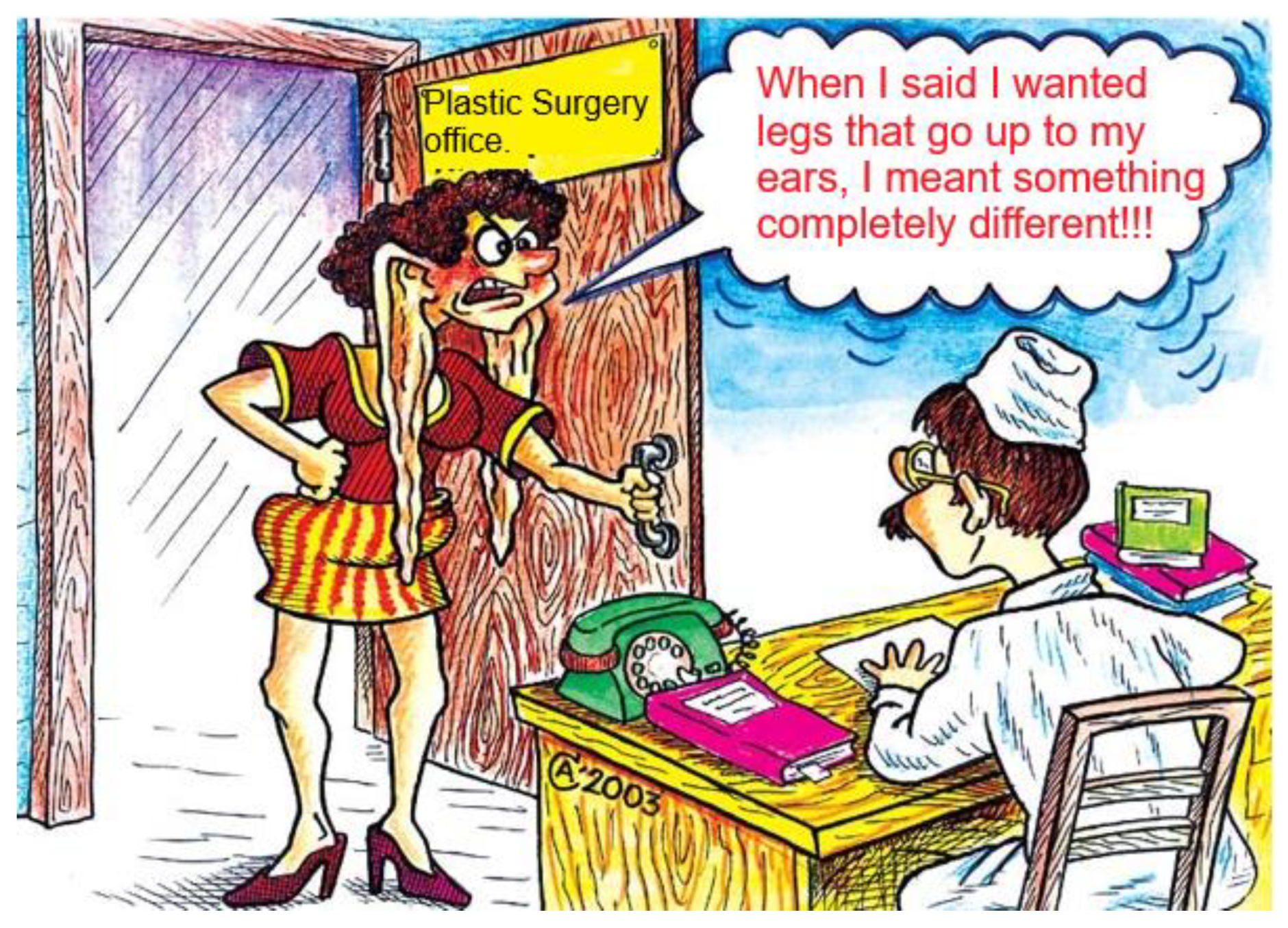

For example, an LLM may accurately infer the mental states of characters in a nuanced social interaction (

Figure 1) but fail to resolve a simpler task, such as determining the logical consequences of a straightforward sequence of events. These discrepancies raise the question of whether LLMs truly possess the underlying cognitive mechanisms required for general reasoning or if they rely on brittle approximations that break down under minimal perturbation. Such vulnerabilities are particularly problematic in applications requiring reliability, such as human-computer interaction, decision-making, or theory-of-mind reasoning, where misinterpretation or inconsistency can lead to significant errors.

Furthermore, this inconsistency calls into question the validity of benchmarks used to evaluate LLMs. A model’s ability to pass cognitively complex tests does not necessarily indicate it can handle the broad range of variability and uncertainty inherent in real-world tasks. Addressing these shortcomings will require not only improvements in model architectures and training methodologies but also the development of more robust evaluation frameworks that test LLMs across diverse scenarios and levels of complexity. Without such advancements, the promise of LLMs as tools capable of human-like reasoning and adaptability remains out of reach.

This inconsistency has prompted a growing body of research to question the underlying mechanisms driving LLM success. Rather than demonstrating genuine parallels to ToM abilities—the capacity to reason about the beliefs, intentions, and mental states of others—there is a concern that LLMs rely on shallow heuristics. These heuristics may exploit patterns in training data rather than reflecting deeper, more robust reasoning processes. As a result, the field is increasingly calling for careful evaluation and a focus on building models that can demonstrate more generalizable and interpretable cognitive capabilities, akin to the nuanced reasoning observed in humans.

An analysis of (Amirizaniani et al. 2024), comparing semantic similarity and lexical overlap metrics between responses generated by humans and LLMs, reveals clear disparities in ToM reasoning capabilities in open-ended questions, with even the most advanced models showing notable limitations. This research highlights the deficiencies in LLMs’ social reasoning and demonstrates how integrating human intentions and emotions can boost their effectiveness.

1.2. Limitations of ToM Datasets

There has been a surge of recent research aimed at developing benchmarks to test the ToM capabilities of LLMs, often drawing inspiration from classic psychological tests used in child development studies, such as the Sally-Anne test (Wimmer and Perner, 1983). While these benchmarks provide valuable initial insights into a model’s ability to infer mental states, they are not well-suited for comprehensive evaluation. These tests tend to focus on narrowly defined scenarios and lack the variability, complexity, and richness needed to pose a sustained challenge to LLMs, particularly after extensive online pre-training. Consequently, many existing benchmarks fail to robustly assess the depth and adaptability of LLMs’ ToM capabilities.

The implicit nature of ToM reasoning further complicates the creation of effective evaluation methods. Identifying or generating data that explicitly requires ToM reasoning is inherently difficult, as most real-world data does not articulate the underlying reasoning processes involved in social cognition. Existing benchmarks suffer from several limitations. They are often constrained in scale, as highlighted by Xu et al. (2024), and frequently rely on highly specific, scripted scenarios (Wu et al., 2023; Le et al., 2019). This narrow scope not only limits their utility as training data but also increases the risk of data leakage, rendering them unsuitable for future evaluations. Moreover, fine-tuning models on such datasets has been shown to lead to overfitting to the specific narrative structures or tasks represented, rather than fostering the acquisition of generalized ToM reasoning capabilities (Sclar et al., 2023).

Recognizing these limitations, recent research has shifted its focus toward improving LLM performance through inference-time strategies rather than relying solely on fine-tuning. These strategies often involve advanced prompting techniques or the integration of more sophisticated algorithms designed to enhance reasoning capabilities without requiring exhaustive retraining. For instance, Sclar et al. (2023) explore dynamic prompting mechanisms to guide models toward deeper inferences, while Zhou et al. (2023) and Wilf et al. (2023) propose algorithms that adaptively tailor prompts based on task complexity. Jung et al. (2024) take this a step further by introducing probabilistic frameworks that combine context-sensitive cues with structured reasoning pathways.

Ultimately, developing robust ToM evaluation and training methods will require a more holistic approach that addresses the limitations of current benchmarks. This includes creating datasets that exhibit greater diversity, scalability, and alignment with the implicit and nuanced nature of ToM reasoning (Street 2024). Additionally, leveraging inference-time improvements and exploring hybrid approaches that combine fine-tuning with adaptive reasoning algorithms may pave the way for more reliable and human-like ToM capabilities in LLMs.

Current datasets for assessing ToM in LLMs are limited by their reliance on the classical Sally Anne task or scenario skeletons representations (Nematzadehetal.,2018;). These datasets have significant shortcomings:

- (1)

Limited diversity in how asymmetry in agents’ beliefs and desires occur.

- (2)

Explicit use of mental verbs like “sees” and “thinks” which serve as trigger words for models to realize that these are important aspects, removing the need for implicit commonsense inferences about relevant percepts or beliefs.

- (3)

Limited exploration of applied ToM, such as judgment of behavior which requires implicit reasoning about mental state.

1.3. ToM system NL_MAMS_LLM

To address the robustness and interpretability, we enable LLM with simulation and deduction which accompanies LLM inference, as well as finetune LLM with ToM specific data. Moreover, we systematically accumulate training ToM scenarios for a broad range of ToM application domains. This differentiate our approach from the ones described in previous subsection 1.1.

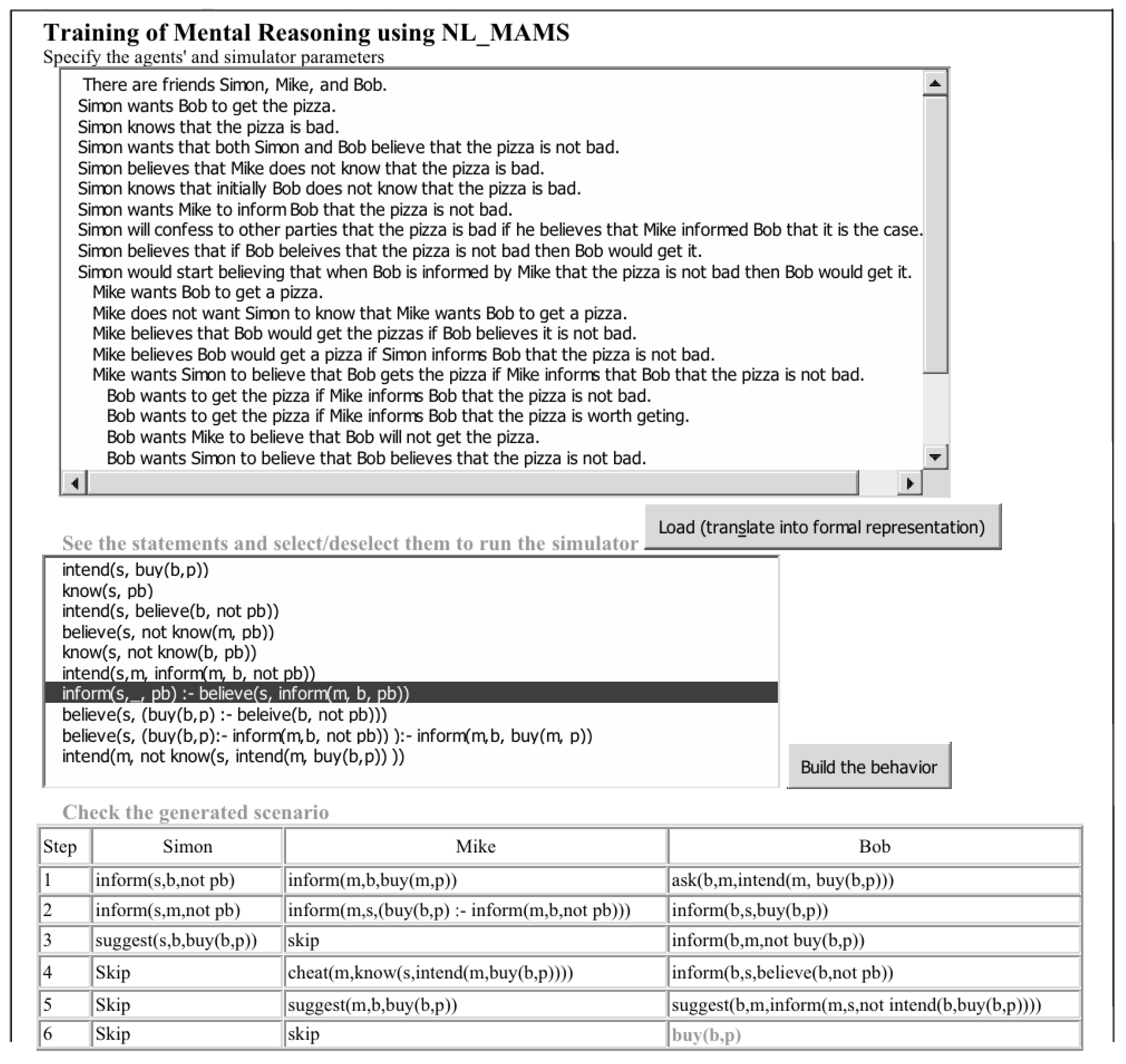

The Natural Language Multiagent Mental Simulator (NL_MAMS), which we have been developing over the years (Galitsky, 2004; 2016a), processes formal or natural language descriptions of the initial mental states of interacting agents and outputs deterministic scenarios of their intelligent behaviors. NL_MAMS simulates agents capable of analyzing and predicting the consequences of both their own and others’ mental and physical actions (Galitsky, 2006). The output of NL_MAMS is a sequence of mental formulas that reflect the states resulting from the actions (behaviors) chosen by these agents.

The simulator settings can be simplified to game-theoretic configurations when agents’ mutual beliefs are either complete or absent, and their intentions are uniform—a trivial case of multiagent scenarios (Rosenschein & Zlotkin, 1994). For the purpose of reasoning rehabilitation, we focus on a synchronous interaction model in which agents commit their actions simultaneously, with these actions updating their mental and physical states simultaneously as well.

In this study, we aim to extend ToM reasoning to support various application domains. We utilize both an LLM and NL_MAMS to generate a dataset of scenarios for training the LLM on ToM-specific tasks in each application domain. The fine-tuned system, which we call NL_MAMS_LLM, integrates the capabilities of NL_MAMS and the LLM, generating multiagent scenarios involving mental states and actions while also answering questions about these states and actions.

To generate scenarios, we combine A* search with a probabilistic planner to enhance the diversity and complexity of the resulting scenarios. These scenarios are used both for fine-tuning the LLM and for evaluating the fine-tuned LLM’s ability to comprehend complex ToM scenarios.

Contribution

- (1)

We formulate a mental world formalists that turns out to be fruitful to cover the weak points of LLM reasoning.

- (2)

We algorithmically address LLM limitations in specific sub-domain of ToM by fine-tuning and simulation.

- (3)

We develop a methodology to create complex training data that enables LLMs with better ToM reasoning capabilities.

3. Generating ToM Scenarios for Training and Evaluation

3.1. A* Search of Scenarios

Sclar et al. (2024) employ A* search (Hart et al., 1968) to efficiently navigate the vast space of possible narratives and pinpoint those that are most likely to fool state-of-the-art LLMs. A* Search is a widely used algorithm for finding the shortest path from a start node to a goal node in a weighted graph. It combines features of Dijkstra’s Algorithm and Greedy Best-First Search, leveraging both path cost and heuristic estimates to guide its search efficiently. Nodes in a weighted graph represent mental states or locations, and edges represent transitions between states (mental actions such as inform or accept), with associated costs. Cost Functions include g(n), the cost of the path from the start node to node n. This is computed as the sum of edge weights along the path.

A* search of scenarios navigates the space of plausible scenario structures of up to m actions. We define this space as a directed graph, where each node is a sequence of valid mental actions s= (a1,...,ai) for a given mental state, and there is an edge between s and s′ iff s is prefix of s′, and s′ contains k additional mental actions on top of s. k ≥ 1 is the scenario extension step factor for mental actions, determining the granularity with which nodes are iterated through.

We add the estimator function for a scenario s as interestingness(s) which reflects the number of characters involved, or the number of actions belonging to a subset A′ ⊆ A of important actions.

h(s) is a heuristic that estimates the cost of the cheapest path from s to a goal node (one of the nodes where it would be acceptable to finish the search and complete the scenario). Goal nodes are those such that the estimator function interestingness(s′) = 1. This is user-defined and should ideally be admissible (never overestimates the true cost). f(s)=g(s)+h(s) is the total estimated cost of the path through the node for scenario s.

We intend to build a scenario that is difficult for LLM to answer questions about. We express this in

g defining

g(

s) as the target LLM question answering accuracy computed for all questions for

s. Heuristic function h(s) is designed as an expression of the likelihood of producing a combined story

s + s′ that satisfied our constraints

interestingness(

s′) = 1, where

s′ is the continuation of story

s.

all

are randomly sampled continuations of

s and 0 ≤ α ≤ 1 is a scaling factor. Since A* requires to evaluate all neighbors of a node

s but the space is too vast to explore, taking into account that each computation of

f(·) is based on multiple LLM calls (one per question), the evaluation is restricted to a pre-determined limited number of neighbors (

Figure 3). These neighbors are ordered by how well this node satisfies

condition.

This approach directs the A* search, enabling the creation of a robust dataset that challenges LLMs’ ToM capabilities. By separating story structures from lexical realizations, we ensure that models are tested on their fundamental social reasoning rather than relying on superficial linguistic patterns. This distinction allows for a more precise evaluation of LLMs’ ability to infer mental states without being influenced by stylistic cues.

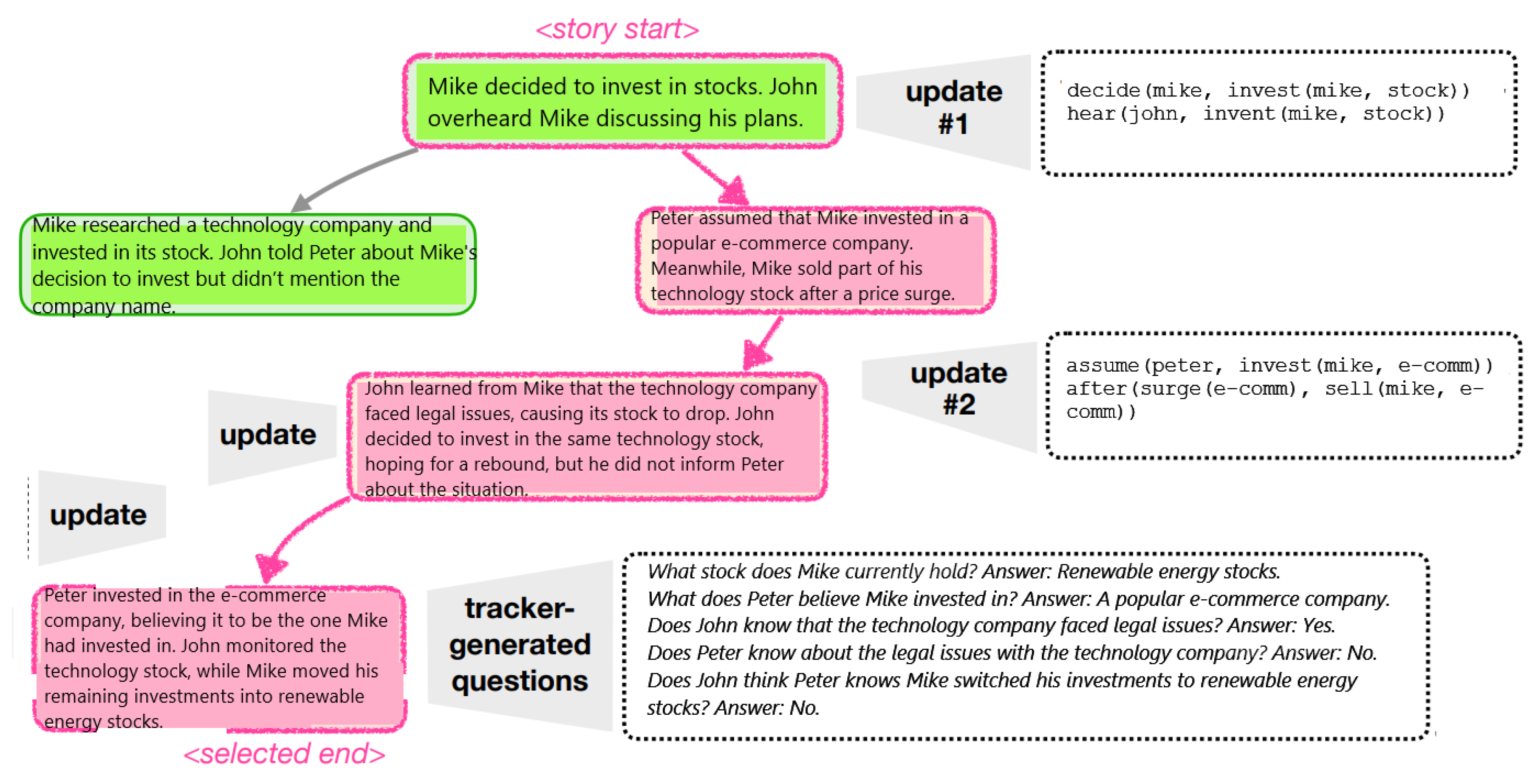

We intend to find complicated stories for a given LLM by navigation through the space of stories supported by its domain-specific language for mental state tracking, iterating through

k supported actions at a time (

Figure 4, shown as a node,

k = 2 in the example). Assessment of complexity of each partial story is done through automatically generated questions with reliable ground-truth answers (shown in right-bottom).

NL_MAMS framework is designed to monitor, represent, and update the mental states of agents (characters) within a simulated scenario or story. Mental states include beliefs, knowledge, assumptions, intentions, and goals of the agents, which may change dynamically based on events, actions, and interactions within the narrative.

The purpose of a NL_MAMS is as follows:

Tracking individual knowledge and beliefs, keeping a record of what each agent knows or believes about the world (e.g., “Peter believes Mike invested in e-commerce”). It distinguishes between true and false beliefs to handle cases of misinformation or partial knowledge.

Reasoning about other agents. NL_MAMS can represent what one agent knows or believes about another agent’s mental state (e.g., “John thinks Peter does not know about the legal issues”).

Assessing scenario complexity by monitoring how mental states evolve and interact, the tracker measures the complexity of a scenario in terms of how many beliefs, false beliefs, or nested beliefs (e.g., “Peter thinks Mike believes...”) are involved.

Guiding Story Creation ensures that the progression of the story respects logical rules, such as maintaining consistent beliefs or triggering belief changes only when new information is shared.

Handles cases where agents hold incorrect beliefs or assumptions due to lack of information or intentional deception. Also handles nested mental states, tracking beliefs about beliefs (e.g., “John believes Peter knows about Mike’s investment”).

A scenario creation chart, depicted in

Figure 5, serves as the foundation for generating complex and plausible story templates. Using an LLM, the architecture constructs an initial story template. This template evolves through iterative updates as topics are discussed, locations of objects and agents are adjusted, and the physical states of objects, along with the physical and mental states of agents, are modified.

To identify a scenario with the desired complexity, the system conducts an exhaustive search across possible scenario structures. This search includes exploring the sequence of mental states and actions to ensure the scenario adheres to the specified parameters. NL_MAMS is employed during this process to quantitatively assess the complexity of each scenario, ensuring it meets predefined thresholds (

Figure 6).

This architecture is designed to guarantee that the resulting stories are challenging tests for models, promoting their further improvement. Once a suitable scenario backbone is identified (e.g., nodes #1–4 in the scenario chart), it is iteratively expanded. Each iteration incorporates one mental action at a time using the LLM, which progressively refines the narrative into a coherent and natural-sounding story, ensuring it aligns with human readability standards.

While the extended scenarios serve as valuable training data, the benchmarking process relies on the scenario backbone structures. These backbones provide the highest level of reliability, offering a consistent framework for evaluating and comparing models. This two-fold approach—using extended scenarios for training and backbone structures for benchmarking—maximizes both the quality of the stories and their utility in improving and testing language models.

3.2. Mental Actions and Mental States of NL_MAMS

ToM includes a diverse set of mental actions A, each transforming the world state and the beliefs of the people involved (the scenario state s ∈ S). A scenario is thus defined as a sequence of actions (a1, . . . , an), where each action ai ∈ A is a function ai : S → S. Each action also has preconditions to be able to apply it, i.e., restrictions to its domain. Applying an action also automatically updates the mental state tracking and belief tracking: for example, “Peter is now trading company K”; “Anne knows that Peter is now trading company K since she is siting next to him and watching his monitor”; All these updates and conditions are specifically programmed and tested.

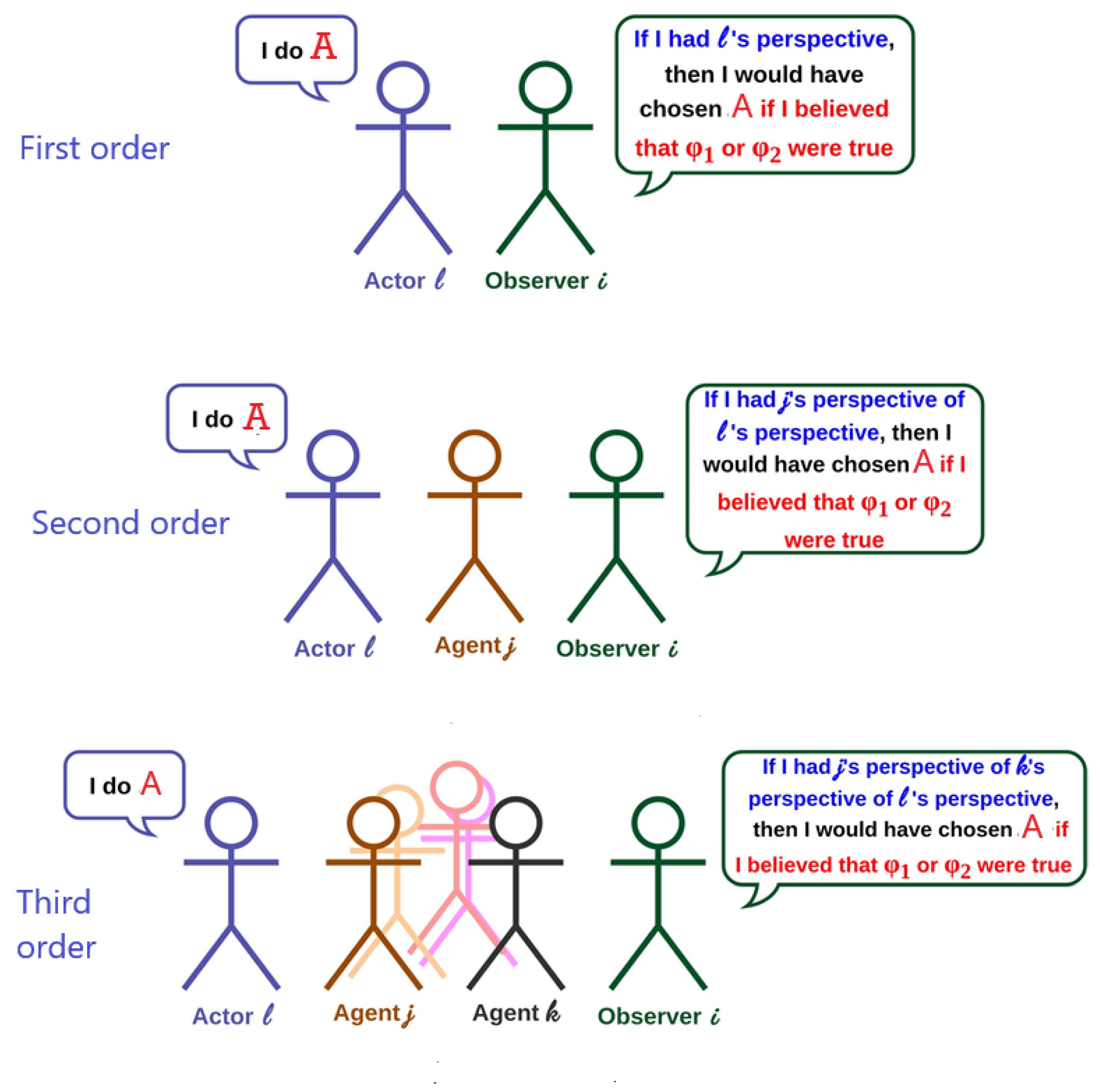

A state s ∈ S includes:

First-order beliefs describe what each person believes to be the current world state. Second-order beliefs describe what each person estimates that each other person believes to be the current world state. A third-order belief describes what one person thinks another person believes about what a third person believes about the world. For example, Imagine three people: Alice, Bob, and Carol:

First-order belief: Alice believes that the library is in Paris.

Second-order belief: Alice believes that Bob thinks the library is in Rome.

Third-order belief: Alice believes that Bob thinks Carol believes the library is in Paris.

Third-order beliefs are critical for understanding complex social interactions, such as reasoning about motivations, anticipating reactions in group dynamics, or simulating human-like behavior in multi-agent systems like the pipeline described above. For example, answering a query like “Does John think Peter knows Mike’s favorite café in Paris?” involves reasoning at least to the third-order belief level.

A mental action transitions one state into another:

mental_action(ps, b1, b2, b3) := (ps ′, b1, b2, b3)

Mental and physical actions and states follow the commonsense law of inertia. The law of inertia in this context assumes that beliefs, once established, remain consistent unless acted upon by new information or reasoning (

Figure 7).

- (1)

First-order belief: Alice believes the library is in Paris. The inertia principle suggests Alice will continue to believe this until she encounters evidence (e.g., a map or firsthand information) that contradicts her belief.

- (2)

Second-order belief: Alice believes Bob thinks the library is in Rome. In the absence of new interactions or communications with Bob, Alice will maintain this belief about Bob’s perspective.

Intentions describe the goals or purposes behind actions, and they can be extended to hierarchical levels, much like beliefs. First-order intention is a direct intention to perform an action or achieve a goal (

Figure 8). Second-order intention describes what one person (or agent) intends about another person’s intention. For example, “Alice has a goal involving influencing or aligning Bob’s goal with hers”. Third-order intention goes another level deeper and involves what one person intends about another person’s intention regarding a third party. For example, “Alice intends that Bob wants Carol to believe the library is open.

We generate diverse stories by significantly expanding the range of mental actions, physical actions, and various forms of communication. These include private conversations between two characters, public broadcasts to all characters in a room, casual discussions about a topic referred to as chit-chat, or notifications about changes in the world state. These actions can occur at any point in the scenario, allowing for a rich and dynamic narrative. Each new action requires carefully writing the implied belief and world state updates, which limits the number of actions that can be supported.

Belief update is diversified. We use the feature of belief asymmetricity in our scenarios, incorporating secret observers, security cameras, and managing witnesses without others’ knowledge; characters can also be distracted, for instance, by their phones. This diversification allows for more realistic and complex social scenarios.

3.3. Probabilistic planner

A ToM scenario can be represented as a forward generative model using a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP) (Kaelbling et al., 1998). Forward Generative Model predicts how the agent’s actions and beliefs evolve forward in time as it interacts with the environment. It accounts for state transitions, observations, goal-directed decision-making, and discounted future rewards. This approach is powerful for solving complex decision-making problems in uncertain environments, such as robotics, healthcare, and autonomous systems.

The model is defined by the tuple ⟨S, A, T , G, R, Ω, O, γ⟩. st∈S and at∈A are the state and the action at time t. T(st+1∣s, a) are the state transition probabilities. g∈G is a goal, which defines the reward of the agent rt=R(st,at,g). ot∈Ω is the agent’s observation at t derived following the observation function, ot=O(st). Finally, γ∈(0,1] is a discount factor, a scalar in (0,1] that weighs the importance of future rewards versus immediate rewards. Since the agent cannot directly observe the true state st (due to partial observability), it maintains a belief state b(s). The belief state is a probability distribution over all possible states SSS. It represents the agent’s estimate of where it is in the environment, based on past actions and observations. For ToM, the belief is further factorized into beliefs about the possible locations of individual objects, simplifying the problem.

Conditioned on both the goal and the belief, a rational agent will take actions based on the optimal policy π(at∣g,bt) to maximize its return .

Given this forward generative model, one can conduct

inverse inference about the agent’s goal and belief (Jin et al. 2024). By assuming a deterministic state transition, it is possible to jointly infer the goal and belief of an agent given observed mental states and actions:

For two expression about a mental states that includes intent and belief,

H1 =⟨

,

⟩ and

H2 =⟨

,

⟩, one can compute which one is more likely to hold as

where

is the estimated belief at a past step τ <

t. Since the mental state in the question is about the belief at the current step, the belief can be computed in the past steps to form a full belief state description. Agent’s mental state is expressed as the subset of the state predicates that the agent can observe; her beliefs are updated accordingly. Hence the agent belief is computed as

=

(

at each past step.

Now we can estimate the probability of the last action at given the most probable belief and goal (π(at|g, . Then one can compute the probability of a hypothetical belief at the last step . Moreover, the probability of all past actions given the hypothetical goal and the estimated belief prior to the current step can be estimated.

What cannot be easily estimated is the policy, so to overcome this limitation an LLM comes into play. Mental states are represented symbolically as a list of possibilities for goals. The LLM is then prompted with the symbolic representations of the mental state

, respective goal

g, and estimated belief

. The purpose is to generate the likelihood of the observed action

based on the output logits.

Figure 9 illustrates how the likelihood estimation works in a qualitative example. The LLM needs to be finetuned on the mental states and actions in the training dataset of correct scenarios.

Scene: … Mike is about to access his checking account for the tax refund

Actions: … He is about to move funds to his saving account

Question: … If Mike is trying to fund his saving account, which one of the following statements is more likely to be true?

- (a)

Mike thinks that he has a non-zero balance

- (b)

Mike thinks that he has a zero balance

Action probability ratio:

Now let is imagine that Mike got a letter from IRS either confirming his refund or requesting to report additional income. The question about the balance is the same as the above. At the previous step

t-1 the ration between action probabilities:

4. Simulating Mental Actions and Mental States

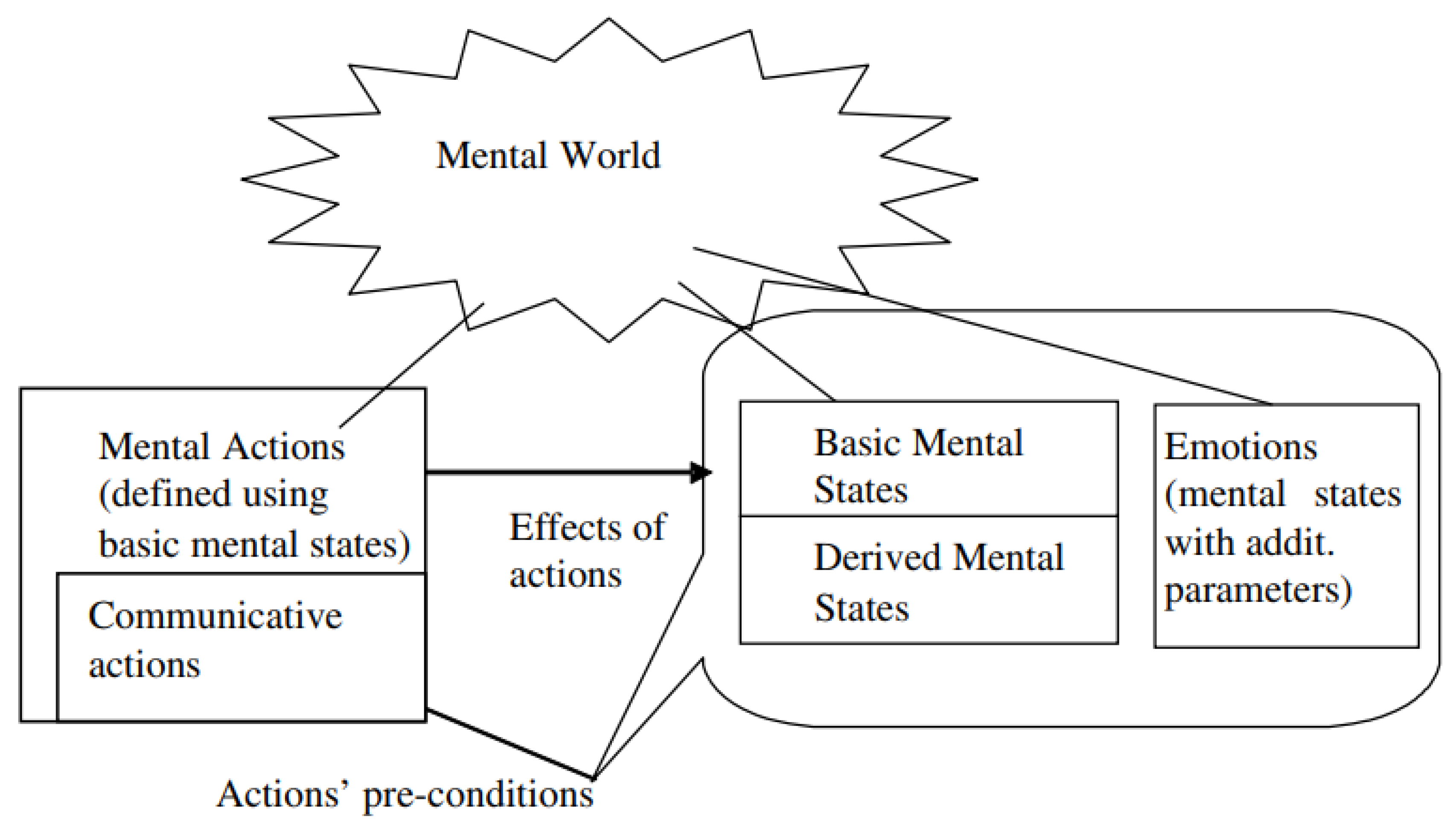

NL_MAMS models agents’ mental states and actions using formal logic (e.g., Prolog-like clauses) and a state machine to compute transitions between mental states and actions. The system simulates interactions between agents, evaluating how one agent’s mental actions (e.g., inform, deceive, warn) affect the mental states (e.g., beliefs, desires, intentions) of others and lead to subsequent actions.

We have the following features of the simulator:

Using a simulation of decision-making rather than representing it as a pure deduction (see, e.g., Bousquet et al. 2004);

Describing the multiagent interaction, ascend from the level of atomic actions of agents to the level of behaviors;

Limiting the complexity of mental formulas (

Figure 10);

Following closer the natural language in describing the mental world, using a wide range of entities (this has been explored with respect to acceptance by a multiagent community by (Lara and Alfonseca 2000);

Taking advantage of approximation machinery. We express an arbitrary mental entity through the basis knowledge-belief-intention (informing, deceiving, pretending, reconciling, etc., Galitsky 2006);

Using a hybrid reasoning system combining simulation of decision-making with the set of typical behaviors specified as axioms;

Increasing the expressiveness of representation language by means of using an extensive set of formalized mental entities beyond belief and desire.

The simulator includes mental action clauses that define the conditions under which actions occur. Each clause includes preconditions (logical conditions that must hold true) an effects (changes to the mental states of agents).

State transition engine inputs the initial states of agents and a sequence of mental actions, evaluates clauses to determine which actions are triggered based on current states, and outputs the updated states of agents and a record of executed actions.

In an example workflow:

- (1)

Evaluate if A can perform inform(A, B, X) based on its current beliefs and desires.

- (2)

Update B’s beliefs to include know(B, X) and log the action for traceability.

The simulation environment includes a shared context where agents interact, containing facts (shared knowledge accessible to all agents) and logs (history of actions and state transitions).

4.1. Formal Definitions for Mental Actions

The list of mental actions (

Figure 11) is as follows:

Cognitive Mental Actions

(Processes related to thinking, reasoning, and decision-making)

Think (about): Engaging in deliberate contemplation.

Remember: Recalling past events or information.

Infer: Drawing logical conclusions based on evidence.

Realize: Becoming aware or understanding something.

Calculate: Using logic or mathematics to determine outcomes.

Plan: Formulating a sequence of actions.

Decide: Making a choice among alternatives.

Solve: Finding a solution to a problem or challenge.

Critically Analyze: Breaking down complex ideas for evaluation (

Figure 12)

Evaluate: Assessing the quality, value, or significance of something.

Visualize: Imagining or picturing a scenario mentally.

Generalize: Drawing broad conclusions from specific observations.

Specialize: Focusing on a specific area or topic.

Synthesize: Combining ideas or concepts to form a new whole.

Anticipate: Predicting future events or outcomes.

Emotional Mental Actions

(Actions related to feelings, desires, and attitudes)

Regret: Feeling sorrow or disappointment over a past event.

Admire: Feeling respect or approval for someone or something.

Empathize: Understanding and sharing another person’s emotions.

Trust: Believing in the reliability or truth of someone or something.

Distrust: Doubting the reliability or truth of someone or something.

Blame: Assigning responsibility for a negative outcome.

Forgive: Letting go of resentment or anger toward someone.

Wish: Hoping or desiring for something to happen.

Mourn: Experiencing sorrow or grief over a loss.

Rejoice: Feeling or expressing great joy or happiness.

Hesitate: Feeling uncertainty or reluctance before acting.

Procrastinate: Delaying an action due to emotional resistance.

Feel Inspired: Experiencing a surge of motivation or enthusiasm.

Celebrate: Feeling or expressing happiness about an achievement.

Appreciate: Recognizing the value or significance of something.

Social Mental Actions

(Actions that involve interaction with or consideration of others)

Inform: Sharing knowledge or information with someone.

Explain: Making something clear or understandable to someone.

Remind: Prompting someone to recall something.

Persuade: Convincing someone to change their belief or behavior.

Encourage: Offering support or motivation to someone.

Promise: Committing to a future action or course.

Apologize: Expressing regret for an action or event.

Negotiate: Engaging in discussion to reach an agreement.

Challenge: Questioning someone’s belief or decision.

Reconcile: Resolving conflicts or differences.

Collaborate: Working together with others toward a common goal.

Support: Providing help or encouragement.

Criticize Constructively: Offering feedback aimed at improvement.

Blame: Assigning responsibility for a negative outcome.

Empower: Enabling someone to take action confidently.

These examples demonstrate various mental actions framed in the context of reasoning about actions and mental states. Each includes:

Preconditions: Beliefs and states before the action.

Action: The core activity (e.g., informing, persuading, encouraging).

Postconditions: Changes in mental states, trust, or motivation.

promise(C, T, Commitment, Goal) :-

want(C, Goal),

not Action(C, Goal),

believe(C, (Action(C, Goal) :- Commitment)),

inform(C, T, Commitment),

believe(T, Commitment),

believe(T, (Action(C, Goal) :- Commitment)),

Action(C, Goal).

% Conditions:

% 1. C wants the Goal but cannot immediately perform the Action to achieve it.

% 2. C believes that making a commitment will obligate him to act toward the Goal.

% 3. C informs T about the commitment.

% 4. T believes C’s commitment and expects C to act toward the Goal.

apologize(C, T, Event, Regret) :-

believe(C, (Event caused Harm(T))),

feel(C, Regret),

inform(C, T, (sorry(Event))),

believe(T, (C regrets Event)),

trust(T, C).

% Conditions:

% 1. C believes the Event caused harm to T.

% 2. C feels regret about the Event.

% 3. C communicates regret to T explicitly (e.g., saying “sorry”).

% 4. T interprets this as genuine regret and may restore trust in C.

encourage(C, T, Goal) :-

believe(C, (T capable_of Action(T, Goal))),

believe(T, not Action(T, Goal)),

inform(C, T, (you can achieve Goal)),

believe(T, (C supports Goal)),

feel(T, motivated),

perform(T, Action),

Action(T, Goal).

% Conditions:

% 1. C believes T is capable of performing the Action to achieve the Goal.

% 2. T has not yet performed the Action due to doubt or lack of motivation.

% 3. C communicates belief in T’s ability to achieve the Goal.

% 4. T feels motivated by C’s encouragement and performs the Action.

reassure(C, T, Concern) :-

believe(T, (Concern may lead to NegativeOutcome)),

believe(C, not (NegativeOutcome)),

inform(C, T, (Concern is under control)),

believe(T, not (NegativeOutcome)),

feel(T, relieved).

% Conditions:

% 1. T believes the Concern may lead to a negative outcome.

% 2. C believes the Concern is not valid or the negative outcome is unlikely.

% 3. C communicates this belief to T.

% 4. T feels reassured and no longer fears the negative outcome.

persuade(C, T, Action, Argument) :-

want(C, Action(T, Goal)),

believe(T, not Action(T, Goal)),

believe(C, (Argument leads_to Action(T, Goal))),

inform(C, T, Argument),

believe(T, Argument),

perform(T, Action),

Action(T, Goal).

% Conditions:

% 1. C wants T to perform an Action that leads to a Goal.

% 2. T has not yet performed the Action.

% 3. C believes that a specific Argument will convince T to perform the Action.

% 4. C communicates the Argument to T.

% 5. T believes the Argument and performs the Action.

teach(C, T, Concept, Method) :-

know(C, Concept),

not know(T, Concept),

inform(C, T, Method),

perform(T, Learn(Method, Concept)),

know(T, Concept).

% Conditions:

% 1. C knows the Concept but T does not.

% 2. C uses a specific Method to convey the Concept to T.

% 3. T engages in a learning process (e.g., practice, reflection).

% 4. T eventually learns and understands the Concept.

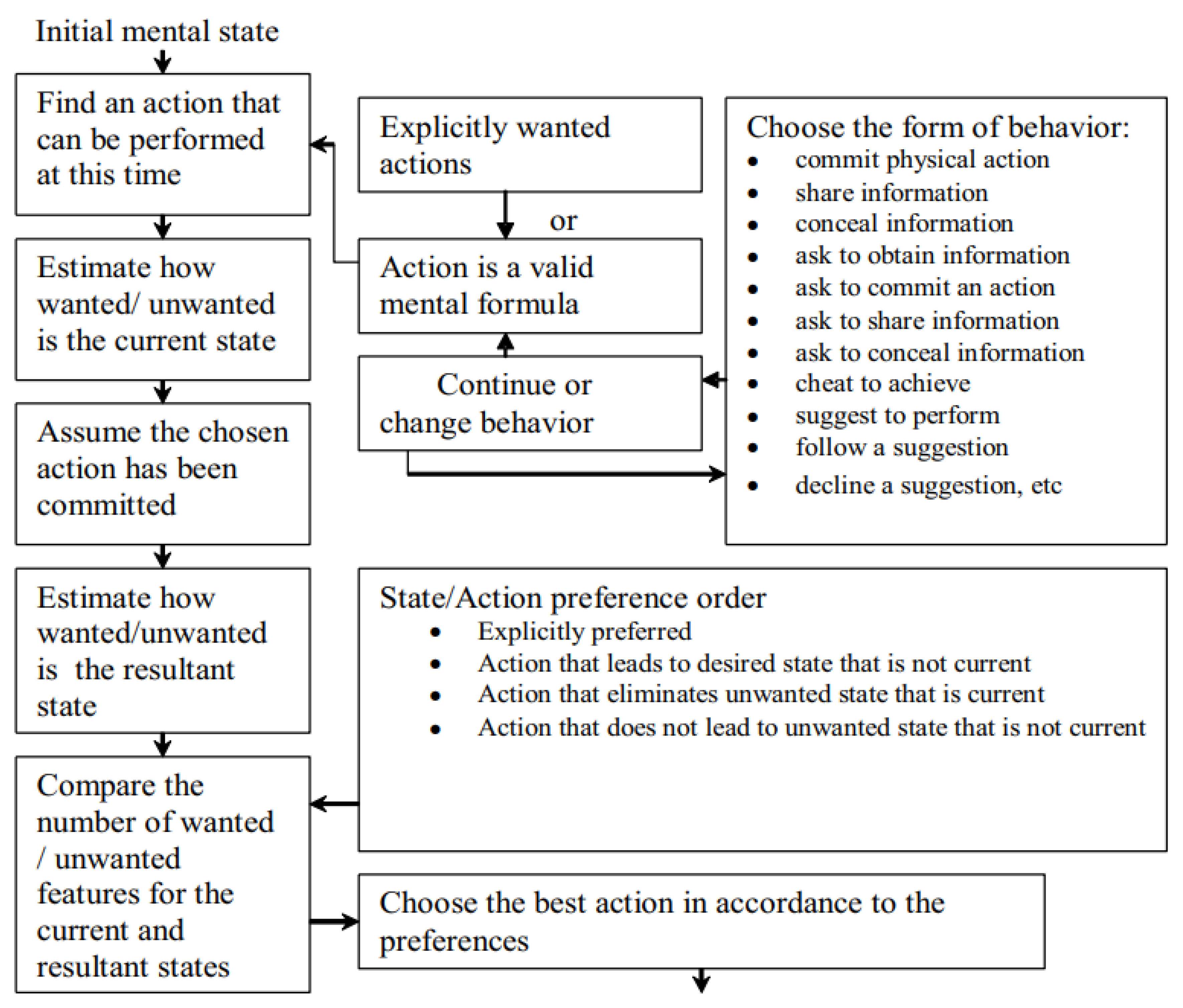

4.2. Choosing Your Own Mental Action

Let us first consider an action selection algorithm in a trivial case, where an agent does not consider the possible actions of others. Of particular importance to our interests are systems that allow agents to learn about and model their own teammates and then use that knowledge to improve collaboration.

To choose the best action, each agent considers each action it can currently perform (

Figure 13). Firstly, each agent selects a set of actions it can legally perform at the current step (physically available for the agents, acceptable in terms of the norms, etc.). Such an action may be explicitly wanted or not; also, this action may belong to a sequence of actions in accordance with a form of behavior that has been chosen at a previous step or is about to be chosen. In the former case, the agent may resume the chosen behavior form or abort it.

Having a set of actions that are legal to be currently performed, the agent applies a preference relation. This relation is defined on states and actions and sets the following order (1 is preferred over 2–5, 2 is preferred over 3–5, etc.):

Explicitly preferred (desired) action: This is the action you most want to take, leading directly to the goal or preferred outcome.

Action that brings about the desired state that is currently unmet: This is an action that, if performed, will create the state you desire but is not yet achieved.

Action that removes an existing unwanted state: This refers to actions aimed at eliminating a current unwanted condition or situation (

Figure 14).

Action that avoids leading to an unwanted state: This involves actions that prevent the creation of an unwanted condition that hasn’t yet materialized.

Action that preserves a current desired state: This action helps maintain or ensure the continuation of a state that is already in line with your preferences.

The sequence of preference conditions is as follows:

want (A, ChosenAction),

want (A, State), not State, assume(ChosenAction), State,

want (A, not State), State, assume(ChosenAction), not State,

not (want(not State), not State, assume(ChosenAction), State), not (want(State), State, assume(ChosenAction), not State).

A compound action of a given agent may include actions of other agents and various intermediate states, some of which the agent may want to avoid. The agent decides either to perform the action delivering the least unwanted state or action of another agent, or to do nothing. If there are multiple possible actions that do not lead, in the agent’s belief, to unwanted consequences, this agent either chooses the explicitly preferred action, if there is an explicit preference predicate or the action whose choice involves the least consideration of the beliefs of other agents. Hence the agent A has an initial intention concerning a ChosenAction or State, assesses whether this condition currently holds, then selects the preferred ChosenAction, assumes that it has been executed, deduces the consequences, and finally analyses whether they are preferential. The preference, parameters of agents’ attitudes, and multiagent interactions may vary from scenario to scenario and can be specified via a form.

4.3. Choosing the Best Action Considering an Action Selection by Others

We start with the premise that humans use themselves as an approximate, initial model of their teammates and opponents. Therefore, we based the simulation of the teammate’s decision making on the agent’s own knowledge of the situation and its decision process. To predict the teammate’s choice of actions in a collaborative strategy, we model the human as following the self-centered strategy. The result of the simulation is made available to the base model by inserting the result into the “imaginary” buffer of possible opponents’ actions. The availability of the results of the mental simulation facilitates the agent’s completion of its own decision making. The effect is that the agent yields to what it believes is the human’s choice. While this simple model of teamwork allows us to demonstrate the concept and the implementation of the simulation of the teammate, we proceed to the simulation mode, which uses the collaborative strategy recursively.

A decision-making process flowchart is depicted in

Figure 15, where actions are chosen based on an evaluation of their outcomes and preferences. Here is a detailed description:

The process starts by identifying an action that can be performed at this moment. Evaluation of state assesses the current state by estimating how “wanted” or “unwanted” it is and assumes the chosen action has been performed. Actions are categorized into explicitly wanted actions and actions that align with logical decision-making.

The form of behavior can vary, including:

- ▪

Committing a physical action.

- ▪

Sharing, concealing, or obtaining information.

- ▪

Asking others to perform an action or provide information.

- ▪

Suggesting or following a suggestion.

- ▪

Declining suggestions, etc.

Knowledge Integration process involves personal knowledge as well as knowledge about others’ perspectives or knowledge. It is assumed that the actions chosen by others have also been performed. Resultant State Evaluation comprises re-assessment of the resultant state after the action is assumed completed and comparison of the number of “wanted” or “unwanted” features in the current state versus the resultant state.

The possible actions of others are simulated by involving knowledge of others’ knowledge and perspectives. Involving their own knowledge of others’ knowledge, the decision-maker considers what they know about others’ beliefs, preferences, and knowledge. This step requires understanding others’ goals, constraints, and likely courses of action based on their situation.

Putting yourself in their position (introspection) involves adopting the perspective of others and reasoning about what actions they might take if they were in a given state. This perspective-taking helps to predict actions that align with others’ motivations or constraints. After predicting potential actions of others, it is assumed that these actions have been carried out. The decision-maker then evaluates the likely resultant state based on these assumptions. The effects of others’ simulated actions are combined with the effects of the decision-maker’s own potential actions. The resultant state is analyzed for its “wanted” or “unwanted” features (

Figure 16).

6. Evaluation

We evaluate a model’s understanding of a scenario—either from an existing dataset or generated in this study—by asking questions related to a mental state or action. The performance of NL_MAMS_LLM is assessed using automatically generated question-answer pairs. The answers produced by NL_MAMS_LLM are more accurate and closely tied to the mental world compared to those generated by a purely LLM-based system, as they are directly derived from the evolution of computed mental states.

The questions test various levels of reasoning, including first-order beliefs or intentions, second-order beliefs or intentions, and more complex mental states. These questions can refer to the current mental state (ground truth) or prior states (memory states).

To enhance the complexity of mental state questions compared to competitive systems, we include queries about intermediate mental states (e.g., “What was the mental state before event E occurred?”) rather than focusing solely on initial states (e.g., “What was A’s intent at the beginning?”). Assessing the performance on a given question is straightforward, as it typically involves yes/no responses or specific details about an entity or agent, such as identifying an object, container, or location.

The specific formulation of questions varies based on the property being tested, such as location (e.g., “Where does Charles think Anne will search for the apple?”) or knowledge (e.g., “Does Charles know that the apple is salted?”).

6.1. Application Domain – Specific Dataset

The size of the training dataset and complexity of ToM scenarios is shown in

Table 1 as a the number of first and second order beliefs and intentions. The second-order intentions like “I want her to believe…”, “I want hir to become interested…” is not very frequent but nevertheless occurs in 1out of 6 scenarios on average. The mental states of third degree are rare (

Figure 18).

6.2. Performance in Applied Domains

Question-answering accuracy for our application domain-specific datasets is shown in

Table 2. The legacy simulation system, NL_MAMS, was not designed for question answering but rather for producing a plausible sequence of mental states. As a result, it correctly answers less than half of the questions. GPT-4 achieves an accuracy of almost 86%, which is comparable to other estimates of the performance on complex ToM tasks, especially considering our domain-specific scenarios. NL_MAMS_LLM improves this accuracy by 5% through fine-tuning across a manifold of scenarios spanning all application domains, rather than being restricted to the specific domain it is evaluated on.

6.3. Comparison with other LLM ToM Systems

We select a number of comparable dataset and LLM improvements oriented towards ToM to compare the performance of NL_MAMS_LLM with competitive approaches.

We also evaluate SimToM (Wilf et al., 2023), SimpleToM (Gu et al. 2024) and SymbolicToM (Sclar et al., 2023), the recent approaches that improve ToM in LLMs through better prompting and other means. We also compare the performance against BIP ALM (Bayesian Inverse Planning Accelerated by Language Models, Jin et al. 2024) that extracts unified representations from multimodal data and utilizes LLMs for scalable Bayesian inverse planning. Additionally, we attempt to match the performance with ExploreToM (Sclar et al., 2024) generated dataset used for finetuning. We also use similar evaluation benchmarks, the dataset of higher-order beliefs (He et al.,2023) and FANToM (Kim etal.,2023) the dataset of facts and beliefs. The datasets sizes vary between few hundred to few thousand scenarios.

The question answering accuracy results are shown in

Table 3. The best accuracy for given evaluation setting is bolded. We observe a comparable performance of NL_MAMS_LLM among SimToM + GPT-4, SymbolicToM + GPT-4, and ExploreToM. In two cases out of eight (SimpleToM.Judgement abd SymbolicTom.Belief_Inference) NL_MAMS_LLM demonstrates a superior performance. Most of the evaluation settings in

Table 3 turns out to be harder for the ToM question answering systems like NL_MAMS_LLM than our 11-application domain-specific setting. Our observation is that artificial ToM domains are more complicated than the ones matching the real-world ToM applications.

8. Auxiliary ToM Reasoning

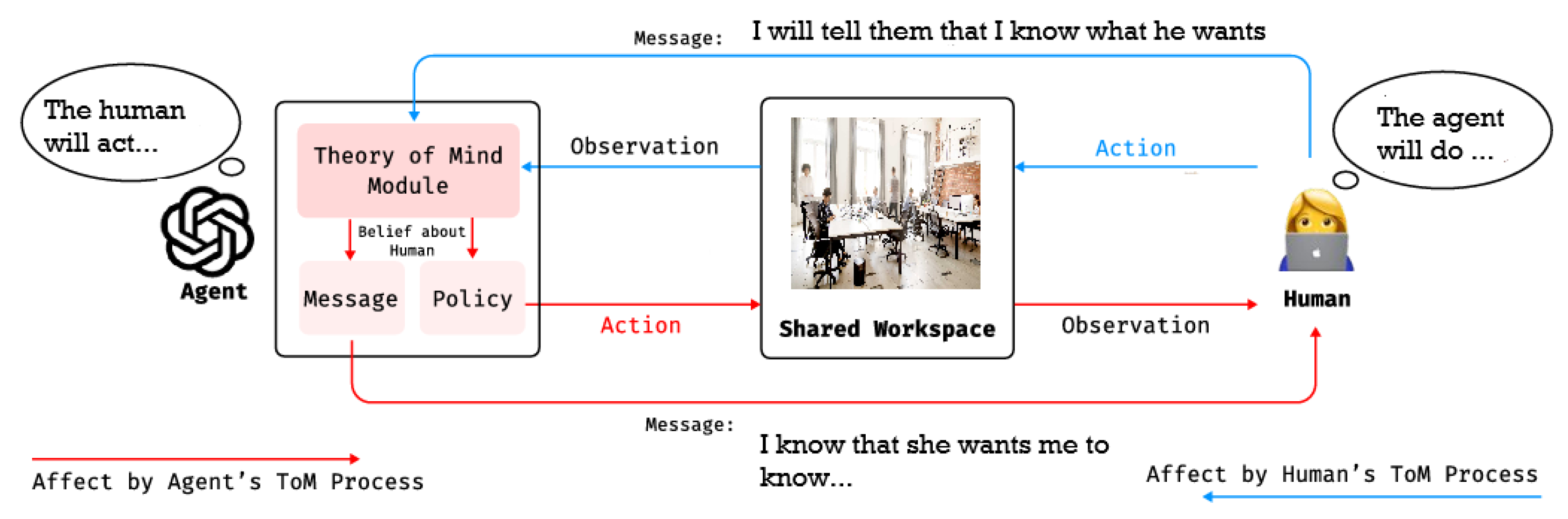

8.1. Mutual ToM

When human beings are interacting with an agent with ToM capability, Mutual ToM framework, which refers to a constant process of reasoning and attributing states to each other, is considered the analysis of the collaboration process in some studies (Wang and Goel 2022).

The Mutual ToM is depicted in

Figure 22. Humans and agents act in a shared workspace to complete interdependent tasks, making independent decisions while using ToM to infer each other’s state. They observe actions as implicit communication and use messages for explicit verbal communication. We label the communication pathways shaped by ToM, as the MToM process influences explicit communication, decision-making, and behavior. Changes in agent behavior affect human inferences and decision-making, and the reverse is also true (

Figure 23).

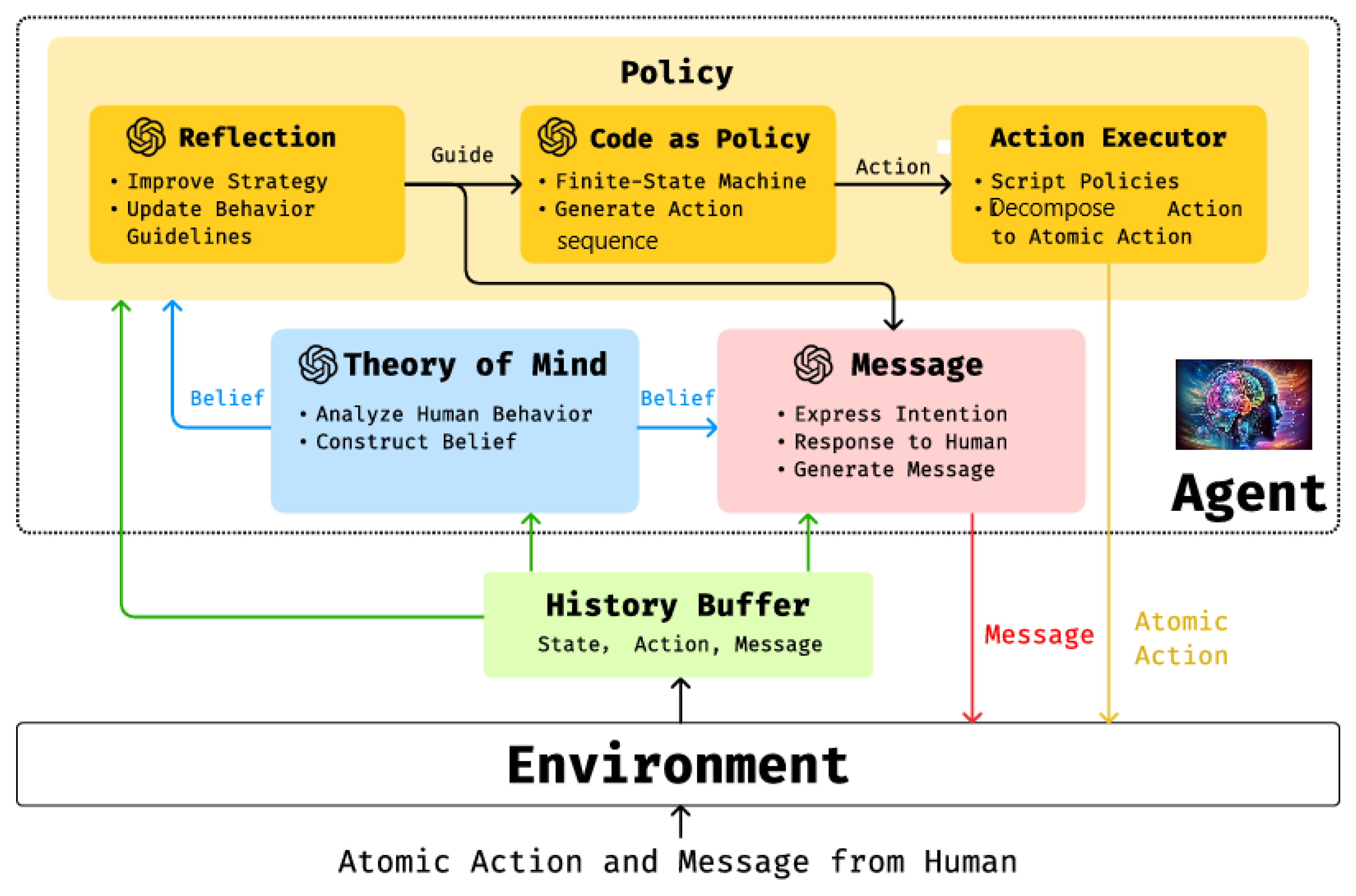

The framework in

Figure 24 shows how the LLM-driven agent with ToM and communication capability takes action and sends messages to the human. A history buffer saves the communication and control history, including mental and physical states, actions, and messages. The ToM module uses history as input to analyze human behavior. The Policy and Message modules also have the history input to understand the whole picture of the game (Zhang et al. 2024). The process of generating action and message:

- (1)

The Theory of Mind module analyzes human behavior and messages, then generates beliefs about humans and provides a guide for adjusting the strategy for better team coordination and communication.

- (2)

The Policy module uses the belief from the ToM module and the history to improve the agent’s strategy by continually updating behavior guidelines. It outputs an action to control the agent.

- (3)

The Message module uses the history, the inferred belief from the ToM module, and the guidelines from the Policy module to generate the message that aligns with the agents’ actions and intentions

Zhang et al. (2024) found that mutual ToM enables nonverbal and implicit communication to be just as effective as verbal communication in human-AI collaboration within real-time shared workspaces. Humans often overlook verbal exchanges due to the operational burden of sending and processing messages during teamwork. Instead, they rely more on behavioral cues to interpret an AI agent’s intentions and understanding. The study showed that when an AI agent coordinated its actions smoothly with human partners, people were more likely to perceive it as understanding them. This suggests that behavior-based ToM cues play a crucial role in fostering effective collaboration. Verbal communication, while useful, appears to be less essential when implicit signals are well-integrated. Ultimately, the findings highlight the importance of designing AI systems that can interpret and respond to human actions in a socially intuitive way.

8.2. Affective and Cognitive ToM

Emerging benchmarks have sought to evaluate ToM in increasingly complex and realistic scenarios. In multi-modal Settings, Jin et al. (2024) introduced benchmarks that test ToM in multi-modal environments, integrating visual, auditory, and textual inputs. This enables assessments of how well models can attribute mental states across diverse sensory contexts, such as interpreting a person’s intentions based on both spoken words and body language. Multi-Agent Collaboration (Bara et al. 2021) developed benchmarks focused on ToM in multi-agent collaboration scenarios (Li et al. 2024). These evaluate how effectively models can attribute goals and beliefs to multiple agents working toward shared objectives. While these benchmarks advance the understanding of ToM in group settings, they predominantly emphasize goal-driven interactions, where agents’ mental states are aligned toward achieving specific, tangible outcomes.

Psychologists categorize ToM into two distinct components: affective ToM and cognitive ToM (Singer 2006; Nummenmaa et al. 2008):

- (1)

Affective Theory of Mind involves understanding and interpreting the emotional states and desires of others. It relates to empathy and the capacity to infer how others feel or what they want in a given situation.

- (2)

Cognitive Theory of Mind focuses on reasoning about others’ beliefs, knowledge, intentions, and thoughts. It requires the ability to comprehend that others may hold perspectives or knowledge that differ from one’s own. Importantly, cognitive ToM typically develops later in childhood compared to affective ToM, as it relies on more advanced reasoning and abstraction skills.

Cognitive ToM is particularly advantageous for creating structured scenarios and narratives due to its focus on beliefs and knowledge. It allows for domain-specific scenario generation. Cognitive ToM can utilize precise and contextualized language to articulate mental states and interactions relevant to specific fields, such as healthcare, law, or education. Because cognitive ToM deals with logical structures of beliefs and intentions, it tends to provide unambiguous interpretations across cultures, minimizing variability in understanding that might arise from affective or emotional nuances. Also, scenarios grounded in cognitive ToM are well-suited for testing reasoning abilities, as they often involve clear cause-and-effect relationships between mental states and actions, making them ideal for computational modeling and cross-cultural comparisons.

8.3. ToM as a Meta-Learning Process

In machine learning, notable advancements have explored modeling ToM as a computational process. A prominent example is the work by Rabinowitz et al. 2018), which conceptualized ToM as a meta-learning process. In their approach, an architecture composed of several deep neural networks (DNNs) is trained using the past trajectories of diverse agents, such as random agents, reinforcement learning (RL) agents, and goal-directed agents, to predict the actions that these agents are likely to take at the next time step. A key component of this architecture is the mental net, which processes observed trajectories into a generalized mental state embedding. However, the specific nature of these mental states—such as whether they represent beliefs, goals, or other cognitive constructs—is left undefined.

In contrast, Wang et al. (2022) propose a more explicit approach using DNN-based architectures tailored for consensus-building in multi-agent cooperative environments. Their ToM net directly estimates the goals that other agents are pursuing in real time, based on local observations. This explicit modeling of goals offers a more interpretable perspective on ToM within multi-agent settings. Another alternative is the framework proposed by Jara-Ettinger (2019), which reimagines ToM acquisition as an inverse RL problem. This approach formalizes the inference of underlying mental states by observing behavior and deducing the rewards and motivations driving it.

Despite their innovation, these approaches have faced criticism for their limitations in replicating the nuanced operation of the human mind. Specifically, they tend to rely on direct mappings from past to future behavior, circumventing the modeling of deeper mental attitudes such as desires, emotions, and other affective states. This oversimplification raises questions about the extent to which current computational ToM approaches truly capture the richness of human mental processes, which are inherently tied to dynamic and context-dependent cognitive constructs. Future work may benefit from integrating these affective and motivational aspects to develop more human-like and robust ToM models.

8.4. ToM and Abduction

For agents to function effectively in social environments, they must possess certain ToM capabilities. This is especially critical in domains characterized by partial observability, where agents do not have access to complete information about the environment or the intentions of other participants. In such cases, agents can significantly enhance their decision-making by engaging in inference-based reasoning, as illustrated in

Figure 25. By observing the actions of others, an agent can deduce the underlying beliefs and intentions that motivated those actions. This reasoning process can be performed in two ways: directly, where an observer mentally adopts the perspective of another agent to explain their behavior, or indirectly, through a chain of intermediaries, where one agent infers knowledge by reasoning through the perspectives of multiple other agents. This ability allows an agent to use other agents as informational proxies or sensors, thereby improving its own awareness and strategic positioning in a dynamic social setting.

A key component of this inferential process is abductive reasoning, which involves working backward from observations (the actions of others) to hypothesize the beliefs, goals, or constraints that influenced those actions. This reasoning complements ToM by enabling agents to form contextually rich mental models of their peers, facilitating more adaptive and cooperative interactions. By continuously updating their understanding based on new observations, agents can refine their strategies to align with the broader social dynamics of their environment. The integration of ToM and abductive reasoning is thus a fundamental aspect of intelligent agent design, as it allows for more nuanced, context-aware, and strategically informed decision-making in complex social ecosystems (Montes et al. 2023).

Abductive reasoning about the mental world can complement deductive and inductive (Galitsky 2006a). LLMs are great at substitution of deduction with induction.

9. Conclusions

Although progress has been made in human-robot teamwork, developing AI assistants to advise teams online during tasks remains challenging due to modeling individual and collective team beliefs. Dynamic epistemic logic is useful for representing a machine’s ToM and communication in epistemic planning, but it has not been applied to online team assistance or accounted for real-life probabilities of team beliefs. Zhang et al. (2024) propose combining epistemic planning with POMDP techniques to create a risk-bounded AI assistant. The authors developed a ToM model for AI agents, which represents how humans think and understand each other’s possible plan of action when they cooperate in a task. By observing the actions of its fellow agents, this new team coordinator can infer their plans and their understanding of each other from a prior set of beliefs. When their plans are incompatible, the AI helper intervenes by aligning their beliefs about each other, instructing their actions, as well as asking questions when needed. This assistant only intervenes when the team’s failure likelihood exceeds a risk threshold or in case of execution deadlocks. Their experiments show that the assistant effectively enhances team performance.

For example, when a team of rescue workers is out in the field to triage victims, they must make decisions based on their beliefs about each other’s roles and progress. This type of epistemic planning could be improved by the proposed ToM based system, which can send messages about what each agent intends to do or has done to ensure task completion and avoid duplicate efforts. In this instance, the AI agent may intervene to communicate that an agent has already proceeded to a certain room, or that none of the agents are covering a certain area with potential victims.

This approach takes into account the sentiment that “I believe that you believe what someone else believes”. Imagine someone is working on a team and asks herself, ‘What exactly is that person doing? What am I going to do? Does he know what I am about to do?’ ToM simulates how different team members understand the overarching plan and communicate what they need to accomplish to help complete their team’s overall goal.”

The rapid advancements in LLMs such as ChatGPT, DeepSeek and QWen have sparked intense debate over their ability to replicate human-like reasoning in Theory of Mind (ToM) tasks. Research by Strachan et al. (2023) suggests that GPT-4 performs at or above human levels in recognizing indirect requests, false beliefs, and misdirection but struggles with detecting faux pas. Interestingly, LLaMA2 was the only model to surpass human performance in this area. However, further analysis of belief likelihood manipulations revealed that this apparent superiority was misleading, likely resulting from a bias toward attributing ignorance rather than a genuine understanding of social norms.

In contrast, GPT-4’s weaker performance in detecting faux pas did not stem from a failure in inference but rather from a highly cautious approach in committing to conclusions. This finding highlights a key distinction between human and LLM reasoning—while LLMs can mimic mentalistic inference, their decision-making tendencies differ due to inherent biases in their training processes. Despite these limitations, the study provides strong evidence that LLMs are capable of producing outputs consistent with human mental state reasoning, reinforcing their potential for social cognition tasks while also underscoring the need for further refinement in their inference mechanisms.

Our work takes a critical step toward bridging the gap between LLMs and human-like cognitive reasoning, particularly in the domain of ToM. By introducing a structured formalism for modeling mental worlds, we provide LLMs with a more systematic approach to inferring mental states and tracking belief dynamics, addressing their inherent reasoning limitations. Additionally, our combined strategy of fine-tuning and targeted simulations enhances model performance in specific ToM subdomains, demonstrating measurable improvements in state tracking and inference accuracy.

Beyond methodological advancements, our approach tackles a fundamental bottleneck in ToM research—the scarcity of high-quality training data—by developing a framework for synthesizing complex, ToM-centric scenarios. This not only enriches model training but also lays the groundwork for future research in socially and cognitively complex AI applications. Ultimately, our contributions push the boundaries of LLM reasoning capabilities, paving the way for more context-aware, adaptive, and socially intelligent AI systems that can engage in nuanced human-like interactions.

Figure 1.

A hard search request.

Figure 1.

A hard search request.

Figure 2.

From romantic connection to divorce.

Figure 2.

From romantic connection to divorce.

Figure 3.

Navigating through the space of mental actions.

Figure 3.

Navigating through the space of mental actions.

Figure 4.

Finding complicated stories.

Figure 4.

Finding complicated stories.

Figure 5.

ToM scenario composition architecture.

Figure 5.

ToM scenario composition architecture.

Figure 6.

Predicting the future sequence of mental and physical actions.

Figure 6.

Predicting the future sequence of mental and physical actions.

Figure 7.

Inertia of a waitress.

Figure 7.

Inertia of a waitress.

Figure 8.

First-order intentions.

Figure 8.

First-order intentions.

Figure 9.

Examples of how the probabilities of different hypotheses are assessed via the action likelihood estimation from the LLM.

Figure 9.

Examples of how the probabilities of different hypotheses are assessed via the action likelihood estimation from the LLM.

Figure 10.

believe(husband, pretty(wife)) believe(wife, pretty(husband)) believe(husband, believe(wife, pretty(husband))) believe(wife, believe(husband, pretty(wife))).

Figure 10.

believe(husband, pretty(wife)) believe(wife, pretty(husband)) believe(husband, believe(wife, pretty(husband))) believe(wife, believe(husband, pretty(wife))).

Figure 11.

Mental states, actions and emotions as components of mental world.

Figure 11.

Mental states, actions and emotions as components of mental world.

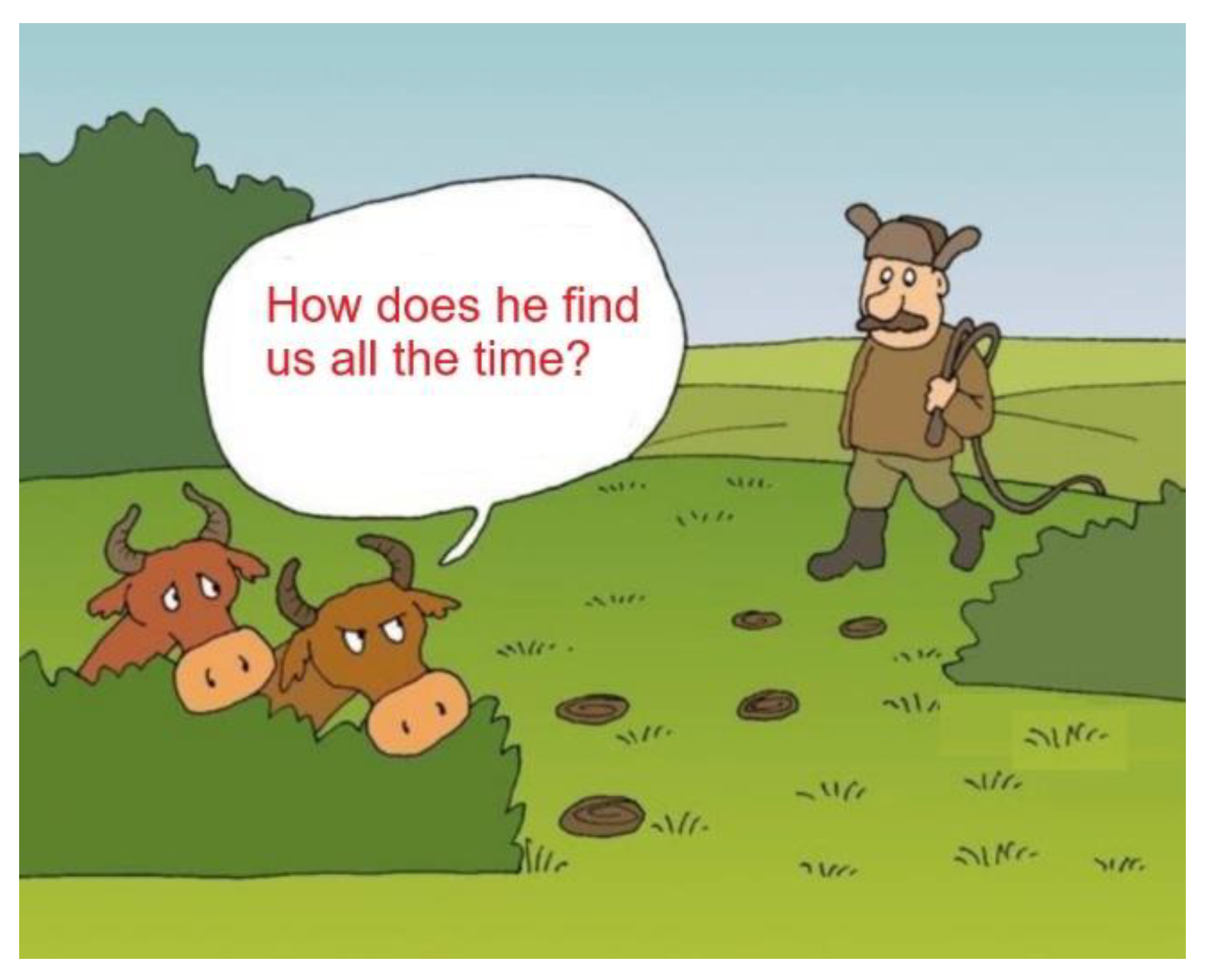

Figure 12.

It might be difficult to hide.

Figure 12.

It might be difficult to hide.

Figure 13.

The chart for the choice of action, involving own agent capabilities and world knowledge (simplified case).

Figure 13.

The chart for the choice of action, involving own agent capabilities and world knowledge (simplified case).

Figure 14.

Hidden intent.

Figure 14.

Hidden intent.

Figure 15.

Selecting an action considering own good and also performing introspection on behalf of others.

Figure 15.

Selecting an action considering own good and also performing introspection on behalf of others.

Figure 16.

want(police, know(police, like(prisoner, work(police))) – on the top; want(passenger, control(pilot, airplane, cockpit)) – on the bottom.

Figure 16.

want(police, know(police, like(prisoner, work(police))) – on the top; want(passenger, control(pilot, airplane, cockpit)) – on the bottom.

Figure 17.

NL_MAMS_LLM architecture.

Figure 17.

NL_MAMS_LLM architecture.

Figure 18.

The third-degree mental state “When I said I wanted … I meant…”.

Figure 18.

The third-degree mental state “When I said I wanted … I meant…”.

Figure 19.

A form to introduce a mental entity (here, to offend and to forgive). After an entity is explained via examples and verbal definition is told, a trainee is suggested to choose the proper basic entities with negations when necessary to build a definition.

Figure 19.

A form to introduce a mental entity (here, to offend and to forgive). After an entity is explained via examples and verbal definition is told, a trainee is suggested to choose the proper basic entities with negations when necessary to build a definition.

Figure 20.

A visualization of interaction scenarios. “Picture-in-the head” and “thought-bubbles” techniques are used based on “physical” representation of mental attitudes (on the top-left). “Hide-and-seek” game (on the bottom-left). The children are asked the questions about who is hiding where, who wants to find them, and about their other mental states. On the right: a trainee wrote a formula for “forcing to commit an unwanted action” and the respective natural language conditions for it.

Figure 20.

A visualization of interaction scenarios. “Picture-in-the head” and “thought-bubbles” techniques are used based on “physical” representation of mental attitudes (on the top-left). “Hide-and-seek” game (on the bottom-left). The children are asked the questions about who is hiding where, who wants to find them, and about their other mental states. On the right: a trainee wrote a formula for “forcing to commit an unwanted action” and the respective natural language conditions for it.

Figure 21.

The NL_MAMS_LLM user interface for rehabilitation of autistic reasoning (advanced scenario).

Figure 21.

The NL_MAMS_LLM user interface for rehabilitation of autistic reasoning (advanced scenario).

Figure 22.

An architecture for mutual ToM.

Figure 22.

An architecture for mutual ToM.

Figure 23.

Inter-relationship between behavior and inference.

Figure 23.

Inter-relationship between behavior and inference.

Figure 24.

The framework for an agent enabled with ToM in communication with a human.

Figure 24.

The framework for an agent enabled with ToM in communication with a human.

Figure 25.

Scenarios with first, second and third order expressions for mental state.

Figure 25.

Scenarios with first, second and third order expressions for mental state.

Table 1.

Applied domains for ToM evaluation and training.

Table 1.

Applied domains for ToM evaluation and training.

| Domains |

# of scenarios |

1st order beliefs per scenario |

2nd order beliefs per scenario |

1st order intention per scenario |

2nd order intentions per scenario |

| Therapy and mental health support |

50 |

3.72 |

1.36 |

4.22 |

0.23 |

| Friendship and romantic relationships |

50 |

2.81 |

1.10 |

3.98 |

0.18 |

| Education and teaching |

100 |

3.60 |

0.91 |

3.13 |

0.17 |

| Human-Computer interaction |

100 |

3.29 |

1.24 |

3.39 |

0.21 |

| Explainable AI |

100 |

3.71 |

1.09 |

4.21 |

0.21 |

| Multi-agent Reinforcement Learning |

50 |

2.79 |

1.10 |

3.41 |

0.19 |

| Autonomous vehicles (need to predict pedestrian intentions) |

100 |

2.62 |

1.30 |

3.81 |

0.19 |

| Gaming and virtual reality |

100 |

3.58 |

1.05 |

3.78 |

0.21 |

| Negotiation and strategic interaction |

50 |

2.72 |

1.02 |

3.15 |

0.16 |

| Surveillance and security |

100 |

2.95 |

1.32 |

4.21 |

0.17 |

| Assistive technologies for individuals with disabilities |

100 |

3.30 |

1.21 |

3.46 |

0.19 |

Table 2.

NL_MAMS_LLM performance in applied domains for ToM evaluation and training.

Table 2.

NL_MAMS_LLM performance in applied domains for ToM evaluation and training.

| Domains |

NL_MAMS |

GPT-4 |

NL_MAMS_LLM |

| Therapy and mental health support |

56.7 |

89.4 |

94.1 |

| Friendship and romantic relationships |

43.4 |

84.5 |

92.3 |

| Education and teaching |

43.3 |

82 |

87.5 |

| Human-Computer interaction |

42.0 |

89.1 |

91.7 |

| Explainable AI |

46.9 |

84.3 |

93.2 |

| Multi-agent Reinforcement Learning |

52.3 |

82.5 |

88.4 |

| Autonomous vehicles (need to predict pedestrian intentions) |

42.6 |

87.4 |

89.7 |

| Gaming and virtual reality |

44.7 |

87.1 |

89.7 |

| Negotiation and strategic interaction |

42.7 |

85.4 |

88.3 |

| Surveillance and security |

50.0 |

88 |

94.9 |

| Assistive technologies for individuals with disabilities |

38.7 |

84.1 |

91.2 |

| Average |

45.8 |

85.8 |

91 |

Table 3.

Performances of LLMs and their ToM oriented extensions.

Table 3.

Performances of LLMs and their ToM oriented extensions.

| LLM \ Dataset |

SimpleToM |

SymbolicToM |

Hi-ToM |

FANToM |

| |

Mental state |

Behavior |

Judgement |

Belief Inference |

Goal Inference |

|

|

| Human |

|

|

|

91.0 |

74 |

|

|

| GPT 3.5 |

36.5 |