1. Introduction

Humans possess a unique and profound ability to reason. By mentally progressing through a series of logical steps, we can draw inferences that would otherwise be out of reach, even without receiving new information from the outside world. In a similar way, large language models (LLMs) often perform better when they generate intermediate steps—a “chain of thought”—before arriving at an answer, leading to more accurate responses than if they answered directly.

Despite their impressive capabilities and significant social impact, LLMs are not inherently reliable. Like many deep neural networks, LLMs are often described as "black boxes" due to the extreme complexity of their internal structure, involving millions or even billions of parameters. This makes their reasoning and decision-making processes obscure and challenging for humans to interpret. While LLMs can be prompted to generate self-explanations to clarify their reasoning, research indicates that these explanations are frequently inconsistent and unreliable. Adding to this issue is the phenomenon of "model hallucinations," where an LLM generates incorrect or entirely fabricated responses that lack any basis in the provided data or knowledge. Such inaccuracies further erode trust in these models.

LLMs continue to encounter difficulties with multi-step deductive reasoning (Creswell et al., 2022), where they must apply a series of logical rules to a set of facts in order to answer a query. Specifically, this type of reasoning requires the model to apply a relevant rule to the supporting facts at each step, deriving new conclusions along the way. LLMs struggle particularly when the structure of the input diverges from the sequential order of rule applications (Berglund et al., 2023).

While LLMs perform well with single-step rule application, their effectiveness declines sharply in multi-step tasks due to challenges in rule grounding. In such cases, each step requires identifying and applying the correct rule and corresponding facts from an extensive mix of input rules, given facts, and previously inferred conclusions (Wang et al., 2024).

To improve on these limitations, the neuro-symbolic AI field advocates for additional mechanisms that enable more trustworthy, interpretable explanations. The goal is to equip users with tools to understand how LLMs reach their conclusions and verify the accuracy and reliability of their outputs. A promising approach is to integrate logic programming, which leverages formal rules and a domain-specific knowledge base. By incorporating symbolic reasoning systems, these methods can identify imprecise or incorrect statements produced by LLMs, offering a structured, rule-based approach to enhance both accuracy and transparency. This hybrid model aims to merge the LLMs' powerful generalization with the precision and reliability of rule-based systems, creating a more interpretable and trustworthy AI solution.

For certain classes of applications that require a high degree of accuracy and reliability (e.g., enterprise applications in the medical, legal or finance domain), LLMs are often combined with external tools and solvers in a hybrid architecture (Gur et al 2024). We believe this is the right approach, especially to tackle problems where precise logical reasoning, planning or constraint optimization is required, as LLMs are known to struggle for this class of problems

Logical reasoning—inferring a conclusion’s truth value from a set of premises—is a critical AI task with significant potential to impact fields like science, mathematics, and society. Symbolic AI, a subfield that employs rule-based, deterministic techniques, is well-suited for generating trustworthy, human-interpretable explanations (Sarker et al., 2021). While symbolic approaches lack the robustness, creativity, and generalization abilities of LLMs, they can complement neural systems to create a hybrid neuro-symbolic AI approach, leveraging the strengths of both methods. The symbolic components contribute faithfulness and reliability that an LLM alone cannot provide (Wan et al., 2024).

In this way, ProSLM (Vakharia et al 2024) combines the creativity and generalization abilities of a pretrained LLM with the robustness and interpretability of a symbolic reasoning engine. This allows users to gain insight into the reasoning behind the system's output, helping them identify potential hallucinations or inaccuracies in the model's response. Additionally, this framework is computationally efficient since it does not require additional training or fine-tuning of the LLM for specific domains.

This first chapter of the book focuses on logical reasoning problems in natural language (NL), a growing area of interest for neuro-symbolic architectures (Olausson et al., 2023). These architectures harness LLMs for generating declarative code and providing commonsense knowledge, while employing symbolic reasoning systems to perform precise logical reasoning. This approach mitigates the limitations each technology faces on its own: LLMs’ challenges in consistent, domain-accurate reasoning, and symbolic reasoners’ limitations with unstructured data and explicitly encoded commonsense knowledge (Galitsky, 2025). These symbolic system limitations reflect the well-known “knowledge acquisition” challenge, which also contributes to their brittleness (Pan et al., 2023).

While many prompting-based strategies have been proposed to enable LLMs to do such reasoning more effectively, they still appear unsatisfactory, often failing in subtle and unpredictable ways. In this work, we reformulate such tasks as modular neuro-symbolic logic programming.

1.1. Types of NL+LLM Reasoning

Existing studies on natural language reasoning (Prystawski et al., 2023) focus on using different prompting strategies on LLMs for better results. Despite significant progress on the LLM prediction accuracy of the final answer, no work has been done to evaluate the correctness of the intermediate steps. In our work, we propose to evaluate intermediate steps at different levels of granularity in order to better probe into the reasoning capabilities of LLMs.

To boost LLM logical reasoning capabilities, Ranaldi and Freitas (2024) fine-tune language models with logical reasoning data to improve logical reasoning capabilities of LLMs. LLMs have also been directly used as soft logic reasoners and a variety of prompting techniques are proposed in order to improve their performance under this paradigm (Wei et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2024). Using large language models as semantic parsers has also shown improvement on the reasoning performance (Olausson et al., 2023; Pan et al., 2023) where natural language reasoning problems are first parsed into logical forms before being fed into an inference engine to output the final answer.

To facilitate NL proof generation, ProofWriter (Tafjord et al., 2021) and FLD (Morishita et al., 2023) are logical reasoning datasets equipped with NL proofs, however both of them are synthetically generated dataset which neither contains abundant natural language variation nor encompasses challenging logical reasoning patters. Previous studies on proof generation focus on ProofWriter(Morishita et al., 2023; Saha et al., 2020, 2021; Yang et al., 2022) and ProntoQA (Saparov et al., 2023). LogicBench is a synthetically generated natural language QA dataset and is used for evaluating the logical reasoning ability of LLMs (Parmar et al., 2024). While FOLIO covers first-order logic and one or more inference rules are used in each example, LogicBench focuses on reasoning patterns covering propositional logic, first-order logic, and non-monotonic logic and focuses on the use of a single inference rule for each example.

Proofs for FOLIO (Han et al., 2022) are constructed in the form of a realistic expert-written logical reasoning dataset. Such proofs need to be written from scratch and are hard and time-consuming to write because humans need to manage both the language and reasoning complexity in the proof-writing process and manually construct many steps of reasoning. The resulting proofs contain more diverse types of inference rules and reasoning patterns in addition to containing more natural language variation and ensured semantic richness.

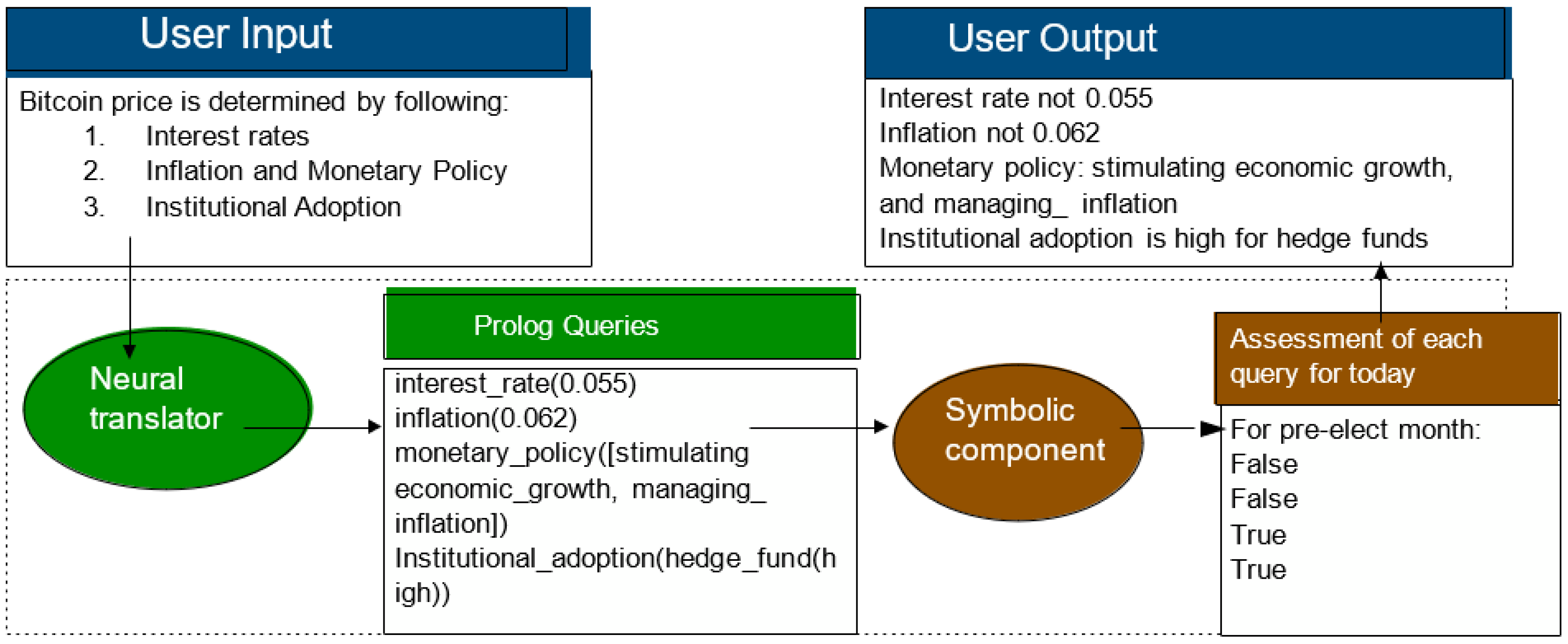

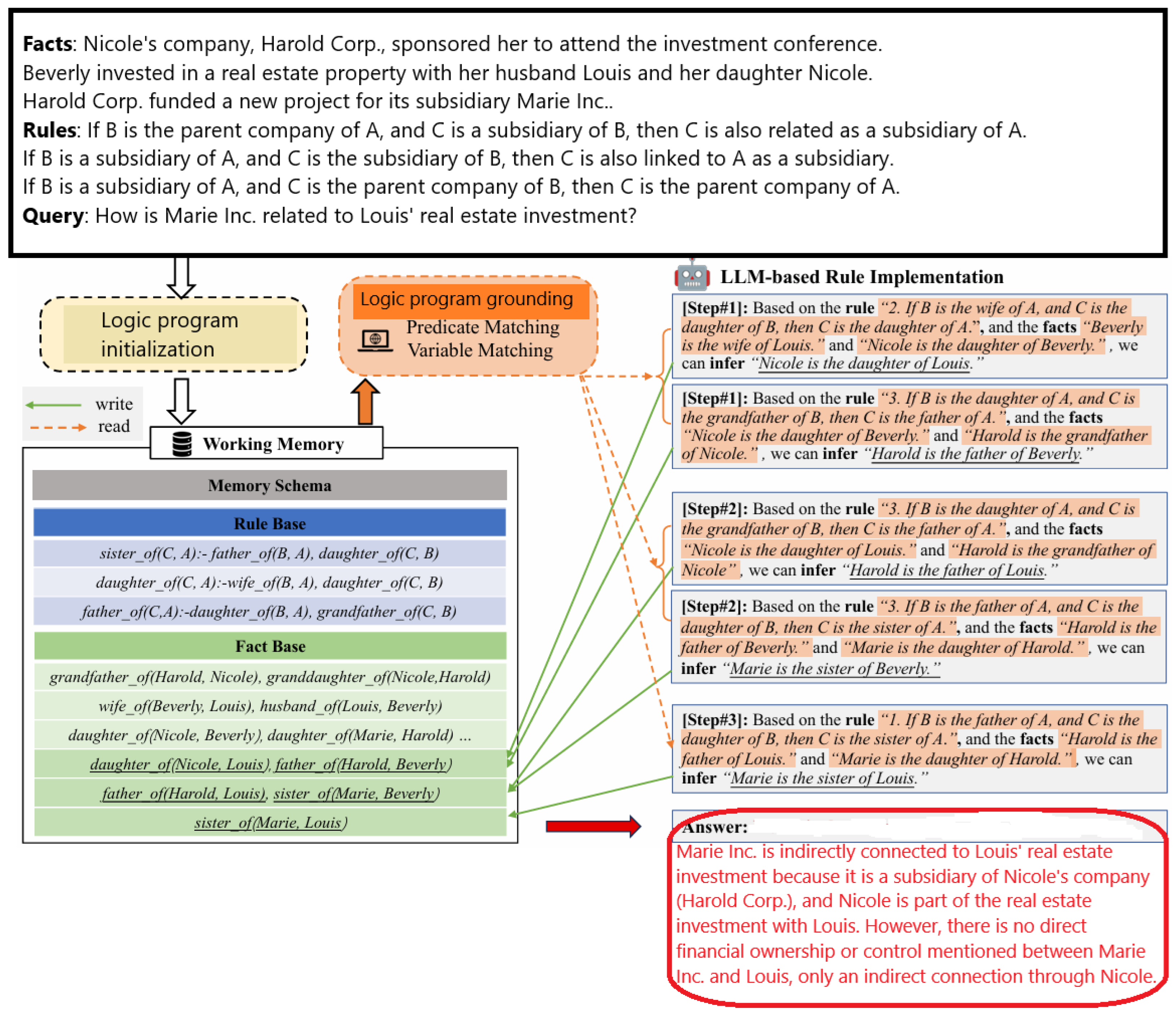

In pursuit of NL proof-generation objective, Vakharia et al. (2024) present a neuro-symbolic framework for knowledge base question-answering systems. Their approach, ProSLM, integrates a symbolic component designed for explainable context gathering prior to querying an LLM, using a knowledge base structured in Prolog. This symbolic layer connects a formal logic-based inference engine to a domain-specific knowledge base and serves two main functions:

1) generating an interpretable, retrievable chain of reasoning to provide context for the input query, and

2) validating the accuracy of a given statement (

Figure 1).

We follow this architecture in that LLM does everything but runs the logic program. Moreover, we wrap LLM and LP as agents and position these agents in adversarial setting. LP agent challenges LLM agent in what it believes is a correct inference result. LLM agent builds an LP attempting to prove that LLM’s result is contradictory to available knowledge.

1.2. Introductory Example with Adversarial Settings

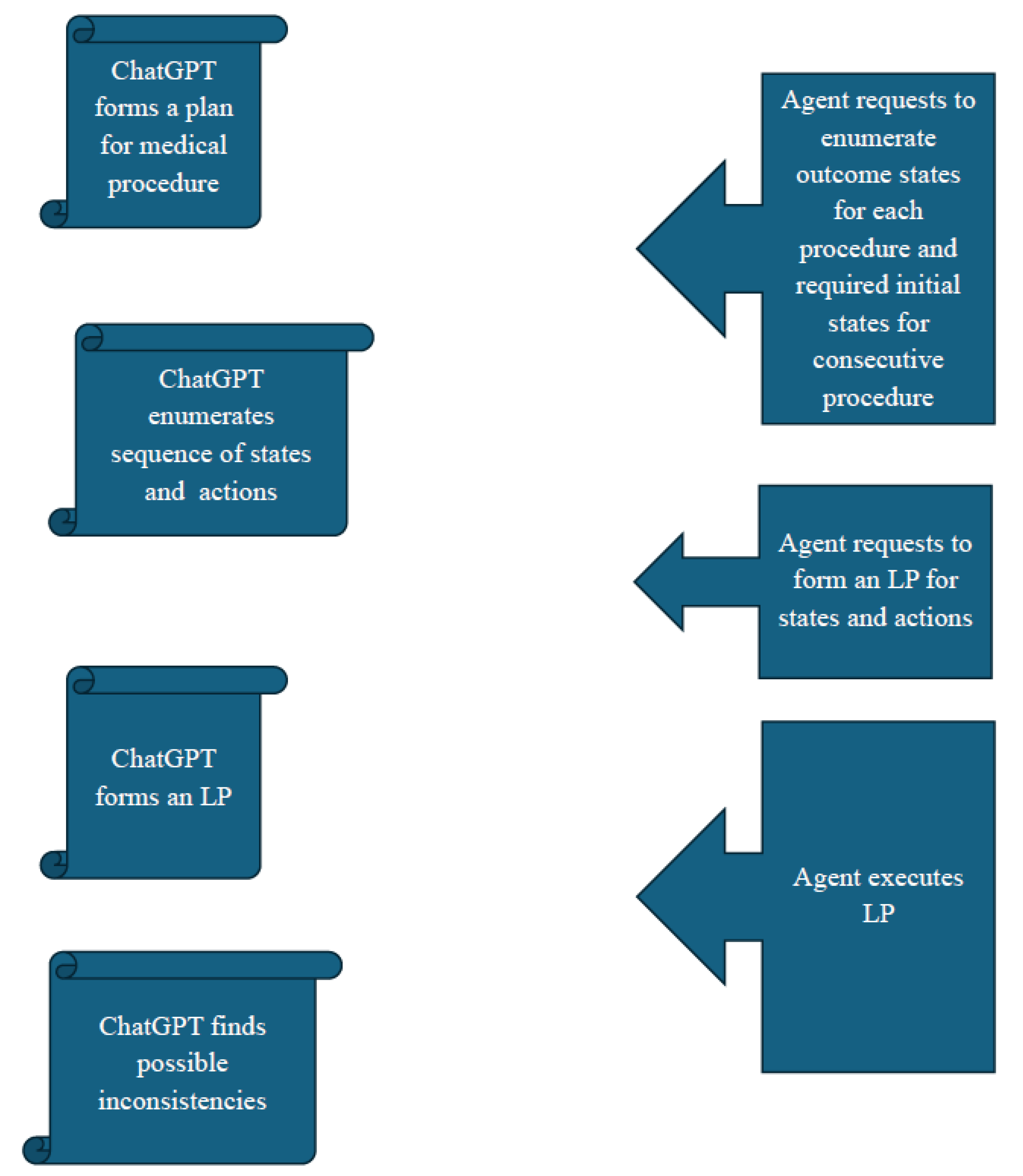

The author wishes to share his personal experience consulting ChatGPT for guidance on arranging his medical procedures. He initially planned to undergo both a colonoscopy and hernia surgery during a single hospital visit. When he asked ChatGPT if his hernia surgery could immediately follow a colonoscopy, he received the following response:

ChatGPT: “It’s sometimes possible to schedule a laparoscopic abdominal hernia surgery to follow a colonoscopy in one visit.”

With this confirmation, he began preparing for the colonoscopy, a process requiring at least 2-3 days. However, just a day before the scheduled procedures, his surgeon recommended canceling the colonoscopy, explaining that “Intestines with residual air and bloating after a colonoscopy are generally inappropriate for hernia surgery.”

In this case, ChatGPT's initial guidance led to a suboptimal arrangement of medical procedures. A step-by-step questioning approach would likely have yielded the necessary information:

Me: “What is the condition of the intestines after a colonoscopy?” ChatGPT: “Residual air and bloating.

Me: “Are intestines with residual air and bloating appropriate for hernia surgery?”

ChatGPT: “Generally not ideal for immediate hernia surgery.”

This experience highlights the need for enhanced questioning and reasoning guidance when using AI for complex decision-making (

Figure 2). This book explores a range of approaches to make LLMs more reliable and effective, with this ChatGPT interaction as a practical example of how improved guidance can lead to better outcomes

1.3. The Proposal

We propose a novel framework that integrates LLMs) with LP to tackle complex reasoning tasks. This approach addresses the limitations of LLMs in maintaining consistency across multi-step inferences and complex problem-solving scenarios. By combining the statistical and contextual strengths of LLMs with the rigor and structure of LP, our system establishes a symbiotic adversarial interaction. Here, the LLM initially operates independently, generating reasoning steps and constructing an LP representation of its inference. The LP module evaluates these reasoning steps through formal logic-based methods, providing structured feedback. The LLM then interprets the LP results, identifies inconsistencies, and refines its conclusions through an adversarial process. We refer to the system being proposed as Adversarial_LLM_LP.

This adversarial dynamic involves the LLM challenging its own initial reasoning using LP feedback, effectively creating a self-correcting loop. The interplay between the probabilistic reasoning of LLMs and the deterministic formalism of LP ensures that each system attempts to refine and potentially outperform the other’s conclusions. This process not only improves the reliability of the LLM's predictions but also enhances its ability to handle controversial or ambiguous tasks, making it a robust solution for complex reasoning.

We will conduct extensive evaluations of this adversarial LP-based neuro-symbolic framework on multiple reasoning datasets. These datasets were designed to test capabilities across a spectrum of logical and commonsense reasoning tasks. While we expect this framework to demonstrate performance comparable to state-of-the-art (SOTA) neuro-symbolic systems across complete datasets, we expect it to show a noticeable improvement on subsets involving controversial or complex queries. This underscores its ability to resolve intricate reasoning challenges that often stump purely neural or symbolic systems.

By leveraging the complementary strengths of LLMs and LP, our approach is intended to push the boundaries of neuro-symbolic reasoning, providing a scalable and consistent method for solving complex tasks in fields ranging from natural language processing to decision-making systems.

1.4. Allegory: A Crocodile and a Behemoth

Let us start with a joke:

A man created a circus act: a crocodile plays the piano while a hippopotamus sings. The performance was a phenomenal success.

Over drinks, the circus director probes the man:

- Surely, this is a trick. You're deceiving the audience.

- Well, yes, there is a trick. The hippopotamus just opens its mouth while the crocodile does the singing.

The humor here lies in the unexpected twist—what appears to be the hippopotamus singing is actually a hidden effort by the crocodile. The act is success depends on the audience's belief in the illusion, not realizing the real "work" is being done elsewhere.

In this context:

- 1)

The crocodile represents the LLM: It does all the "heavy lifting," such as processing complex reasoning, generating outputs, and adapting dynamically to tasks. Just as the crocodile sings while the hippo takes credit, the LLM performs the core computations and logic behind the scenes.

- 2)

The hippopotamus represents LP: It is narrowly focused, following strict rules or processes—much like how the hippo only opens its mouth to give the illusion of singing. It adds structure and visible results but lacks the broader, adaptable capabilities of the crocodile.

This analogy captures how LP might contribute visible formalism or structure to reasoning tasks while the LLM handles the bulk of the actual work, ensuring the performance is seamless and believable.

2. Commonsense Inference Rules

We first define a set of inference rules that can be used for derivations of proof steps.

- 1)

Widely-used inference rules. The most widely used logical reasoning inference rules include universal instantiation, hypothetical syllogism, modus ponens, modus tollens, disjunctive syllogism, conjunction introduction, conjunction elimination, transposition, disjunction introduction, material implication and existential introduction.

- 2)

Boolean identities. During the pilot annotation process, we found that Boolean identities are needed for certain derivations. For example, if "A or A" is true then "A" is true. We therefore allow the usages of Boolean identities

- 3)

Complex inference rules. Some complex inference rules are intuitively correct and can also be proved logically correct with an inference engine. For example, from "A XOR B", we know that "A implies not B". We include in

Table 1 the different categories of inference rules used in our protocol.

Here are the formal definitions of the widely used inference rules:

1. Universal Instantiation (UI): If a property or predicate applies to all elements of a domain, it also applies to any specific element within that domain.

∀x P(x) ⟹ P(c) where ∀x P(x) means "For all x, P(x) is true," and c is a specific instance from the domain.

2. Hypothetical Syllogism: If one statement implies a second, and the second implies a third, then the first statement implies the third.

(P→Q)∧(Q→R) ⟹ (P→R) where P, Q, and R are propositions and ‘→’ denotes "implies".

3. Modus Ponens (MP): If a conditional statement is true, and its antecedent (first part) is true, then the consequent (second part) must also be true.

(P→Q)∧P ⟹ Q where P→Q is a conditional, and P and Q are propositions.

4. Modus Tollens (MT): If a conditional statement is true, and its consequent (second part) is false, then the antecedent (first part) must also be false.

(P→Q)∧¬Q ⟹ ¬P where ‘¬’ denotes negation, and P and Q are propositions.

5. Disjunctive Syllogism (DS). If one part of a disjunction (an "or" statement) is false, then the other part must be true.

(P∨Q)∧¬P ⟹ Q where ‘∨’ denotes "or", and P and Q are propositions.

6. Conjunction Introduction (CI). If two statements are true, their conjunction (combined statement using "and") is also true.

P∧Q ⟹ P∧Q where P∧Q denotes "P and Q," P and Q are propositions.

7. Conjunction Elimination (CE). If a conjunction (combined statement using "and") is true, then both individual parts of the conjunction are also true.

P∧Q ⟹ P and P∧Q ⟹ Q where P∧Q is the conjunction, and P and Q are propositions.

8. Transposition. If a conditional statement is true, then its contrapositive is also true. That is, if P→Q, then ¬Q→¬P is also valid.

(P→Q)≡(¬Q→¬P) where ‘≡’ denotes logical equivalence, and ‘¬’ denotes negation.

9. Disjunction Introduction (DI). If one statement is true, then the disjunction (an "or" statement) with any other statement is also true.

P ⟹ (P∨Q) where P and Q are propositions.

10. Material Implication. A conditional statement P→Q is logically equivalent to ¬P ∨ Q (either P is false, or Q is true). (P→Q)≡(¬P∨Q)

11. Existential Introduction (EI). If a property holds for a particular individual, then there exists at least one element in the domain for which the property holds. P(c) ⟹ ∃x P(x) where c is a specific instance, there exists an x such that P(x) is true."

These reasoning rules are fundamental to formal logic and can be applied in various domains, including mathematics, philosophy, computer science, and artificial intelligence.

We proceed to the complex rule:

From a ⊕ b, we know a →¬b; from a → b and b → a, we know ¬(a ⊕ b).

¬b ⊕ b is always true; a ⊕ b is equivalent to ¬a ⊕¬b.

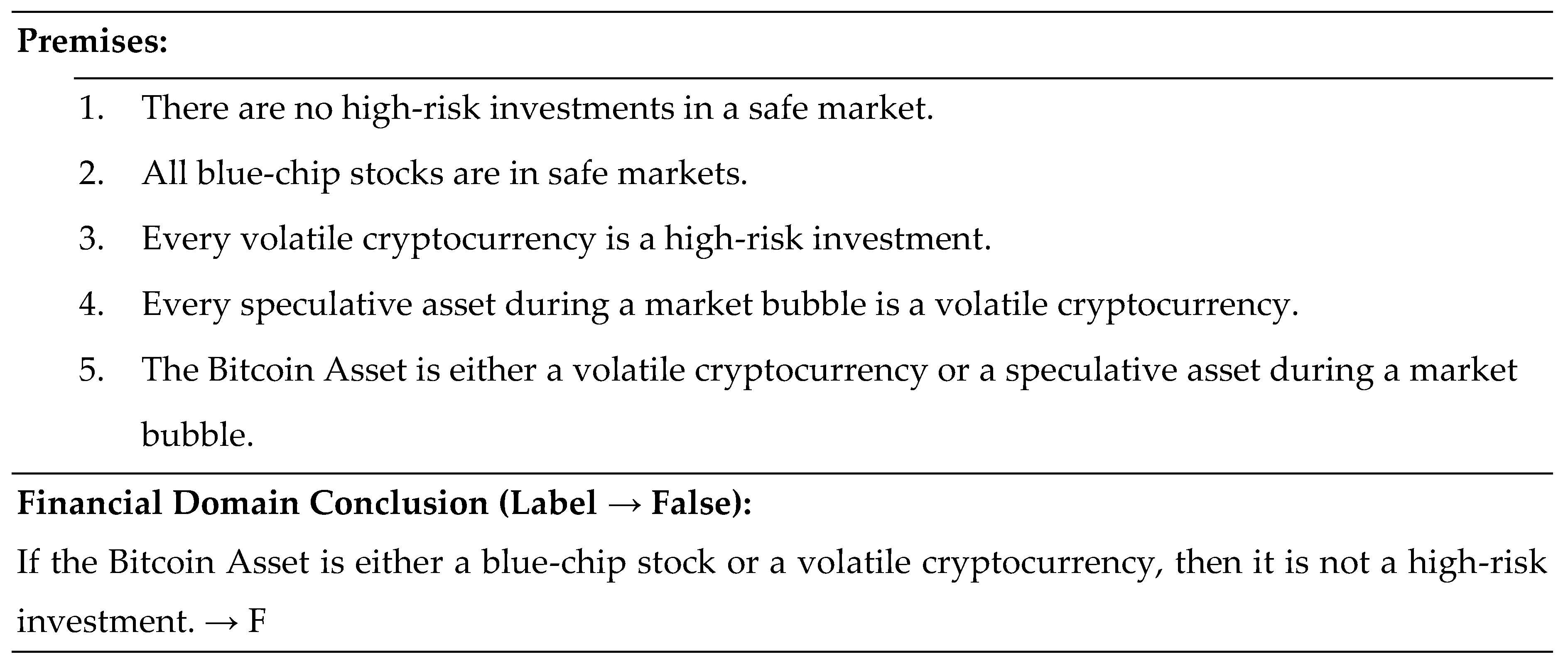

Let

a represent "The Bitcoin Asset is a volatile cryptocurrency, b represent "The Bitcoin Asset is a blue-chip stock."

a⊕

b means "The Bitcoin Asset is either a volatile cryptocurrency or a blue-chip stock, but not both." (

Figure 3).

Formula Derivation (

Table 1) is as follows:

From a⊕b, we know a→¬b. This means: if the Bitcoin Asset is a volatile cryptocurrency (a), then it is not a blue-chip stock (¬b).

-

From a→b and b→a, we know ¬(a⊕b). This means:

If the Bitcoin Asset being a volatile cryptocurrency implies it is a blue-chip stock (a→b), and being a blue-chip stock implies it is a volatile cryptocurrency (b→a), then it cannot be the case that the Bitcoin Asset is either a volatile cryptocurrency or a blue-chip stock but not both (¬(a⊕b)). In this case, the two characteristics are mutually inclusive, not exclusive.

-

¬b⊕b is always true

This means:

Either the Bitcoin Asset is not a blue-chip stock, or it is a blue-chip stock, but not both (¬b⊕b). This is always true as it covers all possible cases.

-

a⊕b is equivalent to ¬a⊕¬b

This means:

The Bitcoin Asset being either a volatile cryptocurrency or a blue-chip stock but not both (a⊕b) is equivalent to the statement that the Bitcoin Asset is neither a volatile cryptocurrency nor a blue-chip stock, or that it is not neither (¬a⊕¬b).

-

From ∀x(A(x)→C(x)) and A(mike)∧B(mike) we know C(mike)∧B(mike)

This means:

If for all financial assets x, If A(x) (being a high-risk investment) implies C(x) (causes market volatility), and if Mike's investment is both a high-risk investment (A(mike) and a speculative stock (B(mike)), then we know that Mike's investment causes market volatility (C(mike)) and is still a speculative stock (B(mike)).

This formula captures logical relations between financial characteristics like high-risk investments, volatility, and blue-chip stocks, applying propositional logic and predicate logic concepts.

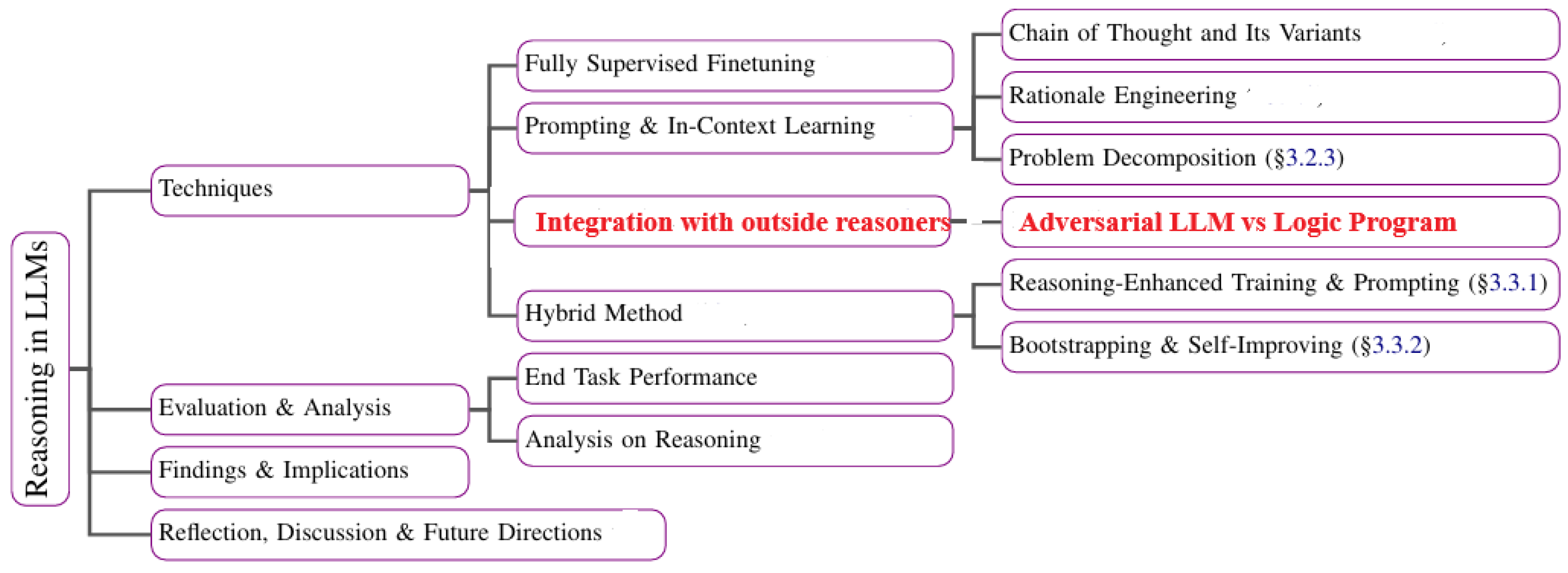

There is a broad spectrum of issues associated with reasoning in LLMs (

Figure 4). The focus of this chapter is

Integration with outside symbolic reasoning in adversarial setting.

3. Neuro-Symbolic Rule Application Framework

The logic program for implementing working memory consists of three core components (

Figure 5):

1) Fact base,

2) Rule base,

3) Logic program achema.

The fact base is a structured repository that stores facts derived from the input context and objects. These facts exist in both NL and symbolic forms to facilitate accurate reasoning during multi-step rule application. Symbolic facts are crucial for intermediate reasoning processes, ensuring a smooth transition between different reasoning steps.

The rule base holds a list of input rules. Similar to the fact base, these rules are stored in both NL and symbolic forms to enable precise symbolic referencing and language-based execution. These rules guide how facts are applied and manipulated during the program's execution.

The logic program schema serves as a unified framework that maintains a consistent vocabulary of predicates and objects relevant to the given instance. This prevents semantic duplication and ensures consistency in reasoning. For example, if predicates like subsidiary_of() or income_level() are defined in the schema, then similar but contextually irrelevant predicates like competitor_of() or noncommercial_status() will not be excluded or confused. All symbolic facts and rules are constructed using these standardized predicates and objects from the schema.

The rule application framework supports three fundamental operations:

- 1)

Read Operation: Retrieves relevant facts and rules from memory, ensuring that the system has the necessary information to carry out the next step in rule application. This retrieval can be selective, targeting only facts and rules pertinent to the specific query or context.

- 2)

Write Operation: Either adds new facts or rules to the memory or updates existing ones. This operation is context-sensitive—if the program involves scenarios where facts can change over time (e.g., an object’s location), it updates existing facts to reflect the new information. If new facts do not conflict with existing data, they are simply added. However, when new information contradicts current facts (e.g., a change in status), the memory updates the facts to avoid inconsistencies.

- 3)

Contextual Fact Management. The decision to add or update facts in memory is based on whether the input scenario involves dynamic or static facts. For example, in scenarios where an object’s status (such as its location or ownership) may change, the system updates the fact base. In static situations, new facts are appended without modification to existing ones. This approach allows the framework to maintain a dynamic and flexible reasoning environment, where facts and rules evolve over time, reflecting changes in context and ensuring accurate, real-time application of knowledge.

The functionality described in this framework—where facts can be added, updated, or replaced in response to new information—can be implemented using a Belief Revision or Belief Update formalism, particularly those associated with dynamic systems. Several formalisms exist for belief update:

AGM Belief Revision (Makinson 1985) is a foundational approach to belief revision. It defines a set of postulates for how rational agent s should revise their beliefs when they encounter new, potentially conflicting information (Darwiche and Pearl 1997). The operations in AGM that closely relate to the system’s read/write functionality are:

- 1)

Expansion: Adding new beliefs (facts) to the knowledge base without removing any existing beliefs. This corresponds to the "write" operation where new facts are added if there is no conflict.

- 2)

Revision: Modifying the knowledge base by incorporating new beliefs, especially when the new beliefs conflict with the existing ones. This is your "update" operation, where contradictory facts are resolved by adjusting the memory to reflect the most recent information.

- 3)

Contraction: Removing a belief from the knowledge base, often when it becomes inconsistent with newly acquired beliefs.

AGM provides a formalized approach to consistency maintenance by ensuring that revisions do not lead to contradictions in the knowledge base.

Dynamic Epistemic Logic models the evolution of an agent’s beliefs over time, accounting for actions or events that alter knowledge. DEL operates with epistemic models that represent the state of an agent's beliefs and uses event models to represent the impact of new information. It is particularly suited for systems where:

- 1)

Events (like new facts or rules) cause updates in the agent’s knowledge base.

- 2)

Public announcements or private observations can change the belief state of agents by either adding new information or removing/overriding old beliefs.

- 3)

Epistemic actions can involve common knowledge or private knowledge updates, which is useful for collaborative or multi-agent belief systems.

DEL fits well with scenarios where new observations (i.e., facts) update the belief system dynamically, just as your system reads new information and decides whether to update or append facts.

Bayesian Networks can also model belief updates, especially when facts are probabilistic rather than deterministic. In this case, the update is not a hard rewrite of a fact but rather an adjustment to the belief's probability, reflecting uncertainty about the truth of the fact. This formalism is useful in systems where evidence accumulates over time and affects the belief state in a non-binary fashion (i.e., beliefs are held with varying degrees of confidence).

Bayesian Update: the knowledge base gets updated with new evidence through the application of Bayes' Theorem, adjusting the probabilities of related beliefs. However, this method is more appropriate when working with probabilistic facts rather than pure logical predicates (Puga et al 2015). In update semantics, the state of a system is updated by new information, where updates are understood as changes to a knowledge state. Update semantics is used primarily in dynamic logic and temporal reasoning systems and can track how states evolve when an event occurs (like receiving new facts).

Given that the logic programing for LLM involves tracking changes to a fact base and applying symbolic rules iteratively, AGM Belief Revision would be the most suitable formalisms. They both provide mechanisms for adding new information, resolving contradictions, and maintaining the integrity of the knowledge base over time, closely aligning with your description of "read" and "write" operations in working memory.

4. Grounding of Logic Programming Clauses

At each step of rule application, Wang et al. (2024) begin by grounding the applicable rules along with their corresponding supporting facts from the logic program. For accurate grounding, a dual strategy of predicate and variable matching is used between facts and rules:

Predicate Matching checks if the predicates of the selected facts align with those in the rule’s premises. This matching, typically performed as an exact string match, can be adapted to use approximate string or model-based semantic matching to handle minor parsing inconsistencies, allowing for more flexible grounding.

Variable Matching ensures that the arguments of the facts can instantiate the rule premises’ variables without conflicts (i.e., each variable consistently aligns with the same argument) or match the objects specified in the rule premises.

Examples illustrating these matching processes follow.

Rule: brother_of(C, A) :- sister_of(B, A), brother_of(C, B)

F1: grandson_of(John, James) F2: sister_of(Mary, John) predicate unmatched

F2: sister_of(Mary, John) F3: brother_of(James, Mary) predicate matched

Rule: brother_of(C, A) :- sister_of(B, A), brother_of(C, B)

F2: sister_of(Mary, John) F3: brother_of(James, Mary) variable matched

F2: sister_of(Mary, John) F4: brother_of(Clarence, Timmy) variable unmatched

Note that the predicates of facts F1 and F2 do not align with rule R, and the arguments of F2 and F4 cannot instantiate variable B in rule R. After this symbolic grounding, rule R can apply to its supporting facts F2 and F3. Different rule grounding techniques are employed depending on the task type. For tasks like logical reasoning, where facts are neither chronologically ordered nor updated, grounding uses an exhaustive enumeration approach. This method considers all possible fact combinations for each rule, according to the number of premises. Both predicates and variables are checked for consistency, and a rule is deemed applicable only if no conflicts are present. To avoid redundant applications, each step’s applicable rules must include any newly inferred facts from the previous round. For constraint satisfaction tasks, which require rules to satisfy various constraint predicates, variable matching is used to rank the most applicable rule at each step.

4.1. LLM-Supported Rule Execution

LLMs are proficient at single-step rule application. Following symbolic rule grounding, which identifies the relevant rules and supporting facts from the logic program at each step, an LLM executes all applicable rules simultaneously. Each rule is accompanied by its supporting facts, and the LLM is prompted to infer potential new facts in both natural language (NL) and symbolic formats. These inferred facts are then incorporated into the logic program accordingly. At each step of rule application, the system verifies whether the newly inferred fact resolves the query (in logical reasoning tasks) or checks for conflicts between rules and facts (in constraint satisfaction, Galitsky 2024).

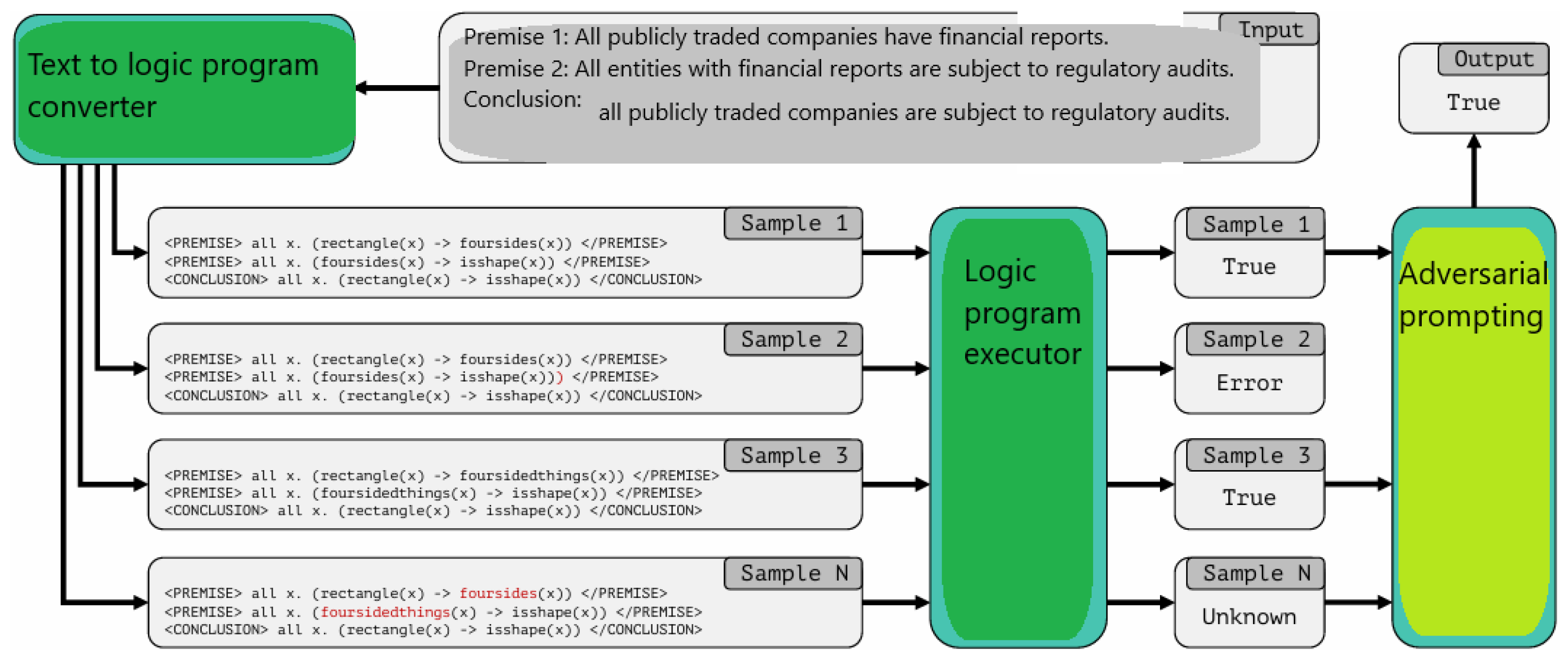

5. Logic Test Generation and Iterative Self-Refinement

To enhance the logical reasoning capabilities of LLMs, an automated reasoning feedback component can be integrated. This component generates declarative logic programs and creates tests to assess their semantic accuracy. By rigorously executing these tests, the feedback component identifies any logical or semantic errors, providing specific feedback on failed tests to refine the logic programs. This iterative feedback process continually improves the precision and reliability of the outputs (

Table 2 and

Figure 6).

Through repeated revisions, the system refines logical outputs until they meet established correctness standards. This approach is particularly effective for complex reasoning tasks, as it not only helps detect subtle logical errors but also enables the LLM to learn from test-driven feedback, progressively improving its ability to produce accurate, well-structured logic programs.

5.1. Building ASP Program

For sentences

All stocks are financial assets.

All tech stocks are stocks.

All high-growth tech stocks are tech stocks.

Some high-growth tech stocks are volatile.

If AssetX is a financial asset, then AssetX is not both a tech stock and a financial asset.

If AssetX is volatile, then AssetX is either a high-growth tech stock or a financial asset.

We have an ASP

% R1: All stocks are financial assets.

financial_asset(X) :- stock(X).

% R2: All tech stocks are stocks.

stock(X) :- tech_stock(X).

% R3: All high-growth tech stocks are tech stocks.

tech_stock(X) :- high_growth_tech_stock(X).

% R4: Some high-growth tech stocks are volatile.

{volatile(X)} :- high_growth_tech_stock(X).

% R5: If AssetX is a financial asset, then AssetX is not both a tech stock and a financial asset.

:- financial_asset(assetX), tech_stock(assetX), stock(assetX).

% R6: If AssetX is volatile, then AssetX is either a high-growth tech stock or a stock.

1 {high_growth_tech_stock(assetX); stock(assetX)} 1 :- volatile(assetX).

Table 3 enumerates the classes of logical expressions. The data used to fine-tune the LLM LP builder had the following three types of sources for these expressions:

NL description → LP code with compilation issues → Critic Feedback on compiler errors → LP code that compiles

NL description → LP code that compiles with test failures → Critic feedback on failures with explanations → LP code with all tests passing

NL description → LP code that compiles with all tests passing.

6. Chain of Thoughts Derive Logical Clauses

LLMs display emergent behaviors, such as the ability to “reason,” when they reach a certain scale (Wei et al., 2022). For instance, by prompting the models with “chains of thought”—reasoning exemplars—or a simple directive like “Let’s think step by step,” these models can answer questions with clearly articulated reasoning steps (Kojima et al., 2022). An example might be: “All elephants are mammals, all mammals have hearts; therefore, all elephants have hearts.” This capability has attracted significant interest, as reasoning is often seen as a defining feature of human intelligence that remains challenging for current AI systems to fully replicate (Mitchell, 2021).

In LLMs, the chain of thought (CoT) approach helps the model derive logical clauses and reach conclusions through a sequential, interpretable process. This structured reasoning enables LLMs to decompose complex tasks into a series of logical steps, improving both the clarity and coherence of responses. The CoT approach derives logical clauses as follows:

- 1)

Problem decomposition: the model first breaks down the input into distinct components. By analyzing the question's structure, the model identifies relevant entities, variables, and context that are essential for reasoning. As a result, we obtain a set of decomposed components, D=(E,V,X) where E is a set entities, V is a set of variables and X is a context.

- 2)

-

Sequential reasoning: the model establishes a sequence of logical steps, progressing from one inference to the next. This may involve if-then statements, comparisons, or assumptions that help clarify relationships and dependencies among the components. Each step in this sequence is guided by the preceding one, maintaining logical continuity. For each step i, we apply logical transformations Ti based on contextual knowledge and prior clauses:

Ci=Ti (Ci-1,D)

C1=T1(D) (initial clause derived directly from D)

This step yields intermediate clauses C1, C2,…,Cn.

- 3)

Intermediate conclusions: as the model moves through each logical step, it draws intermediate conclusions or generates "sub-clauses" that build on previous reasoning. These intermediate statements reflect partial answers or deductions that contribute to the final solution. For a subset of clauses {C,Ci,…,Ck}where k<n, derive sub-conclusions Sj such that Sj =Combine(C1,…,Ck) and output the set of sub-conclusions S={S1,S2,…,Sp}.

- 4)

Aggregation of clauses: the intermediate clauses are then combined or aggregated to form a coherent set of logical statements that address the initial query. This step ensures that all intermediate conclusions align and support the overarching response. We aggregate S and remaining Ci clauses such that Cfinal=Aggregate(S, Ck+1,…,Cn), outputting the final clause Cfinal.

- 5)

Final conclusion: The model synthesizes the chain of logical clauses into a comprehensive response. The CoT process allows LLMs to arrive at complex conclusions in a structured and transparent manner, improving accuracy and making the reasoning process traceable.

The CoT framework is especially valuable for tasks that require multi-step reasoning, like solving mathematical problems, constraint satisfaction, and scenario-based questions, where each logical step contributes critically to the overall solution.

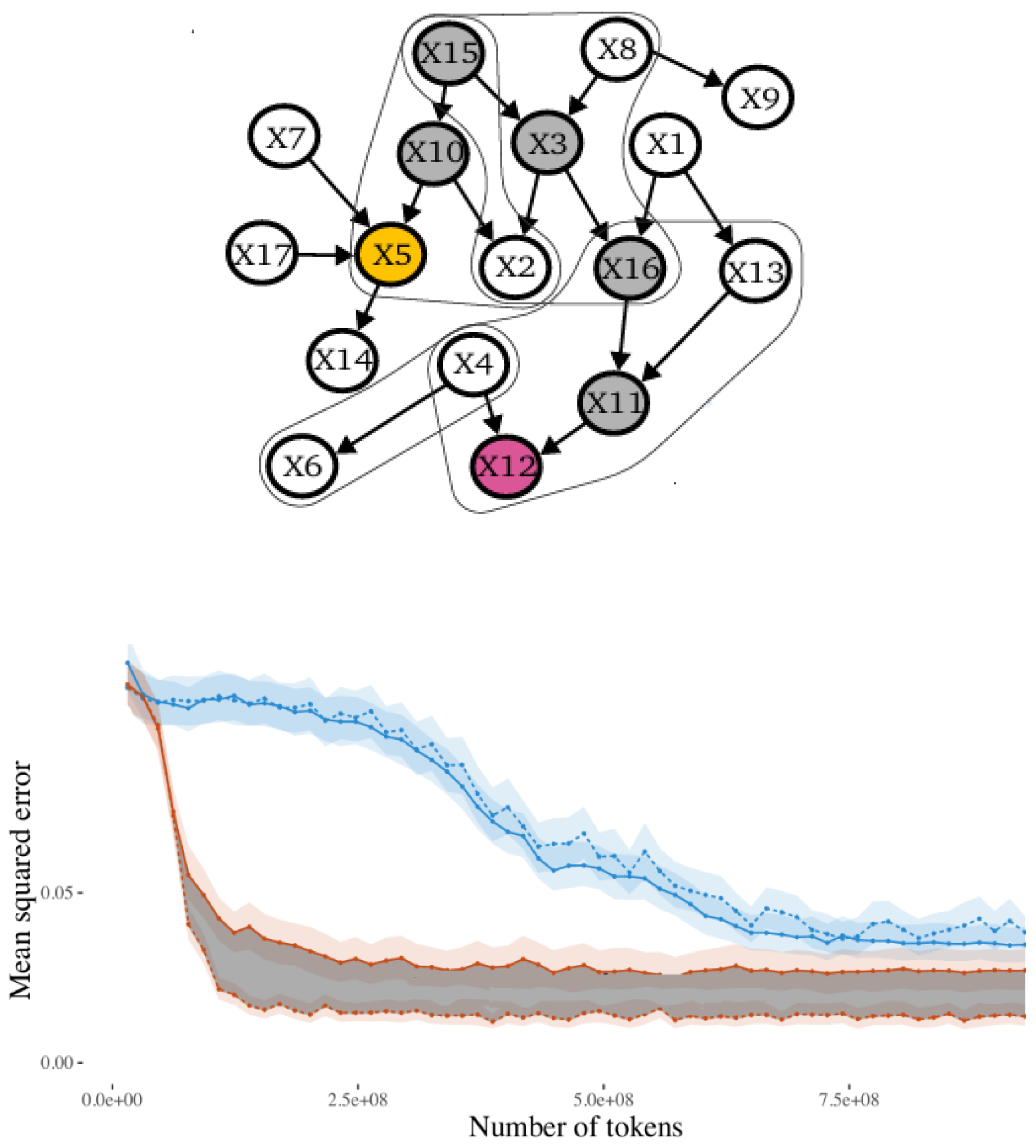

Prystawski et al. (2023) explore the mechanisms that make CoT reasoning effective in language models, proposing that reasoning works best when training data is structured in overlapping clusters of interdependent variables. This structure allows the model to chain accurate local inferences, enabling it to infer relationships between variables that were not seen together during training. The authors identify a "reasoning gap," demonstrating that reasoning through intermediate variables reduces bias when using a simple autoregressive density estimator trained on local samples from a chain-structured probabilistic model. They further validate this hypothesis in more complex models by training an autoregressive language model on samples from Bayes nets with only a subset of variables included in each sample. The models are tested for their ability to match conditional probabilities with and without intermediate reasoning steps, revealing that these steps improve accuracy only when training data is locally structured around variable dependencies. This approach to locally structured observations and reasoning also proves more data-efficient than training on all variables simultaneously, highlighting that the effectiveness of step-by-step reasoning stems from the localized statistical patterns in training data.

LLMs are trained on natural language documents, which often focus on closely related topics (Blei & Lafferty, 2007). When concepts frequently co-occur in data, their mutual influence can be assessed directly with simple statistical estimators. However, to infer the effect of one concept on another when they haven’t been seen together, a series of inferences connecting related concepts is necessary. CoT reasoning becomes beneficial precisely when the training data is locally structured, meaning observations occur in overlapping clusters of related concepts. These clusters can then form logical clauses that can be retained, boosting the accuracy of the system in future inference sessions.

Let us consider a task of building a probabilistic clause p::C:-A (Riguzzi et al 2018, Galitsky 2025). One may know the value of some variable A and intents to learn about another variable C, to compute p(C|A). However, to compute probabilities using observed samples from joint distributions, one needs to count A and C together, which is rare. Therefore, one would experience difficulties estimating p(C|A) directly. Instead, one might estimate it by building a chain of clauses via intermediate variables.

If conditioning on an intermediate variable

B figures out that

A and

C are independent of each other, then the conditional probability can be assessed by marginalizing over

B, using the fact that

For example, suppose we want to answer a question like “What is grown in Los Banos, CA?” using a model trained on Wikipedia text. Wikipedia pages for states and counties often contain information about the crops grown, while pages for cities typically indicate which county a city belongs to. However, city pages rarely mention the crops grown there directly. While an LLM might attempt to answer the question directly, it would likely have greater success by first identifying that Los Banos is located in Merced County, California. By adding this intermediate step—“Los Banos is in Merced County”—before answering with “cotton is grown in Los Banos,” an autoregressive model can more effectively utilize the dependencies present in its training data.

A visualization of a Bayes net for a logic program is depicted in

Figure 7. The pink variable is an example observed variable and the yellow variable is an example target variable. Gray variables are examples of useful intermediate variables for reasoning. Lines show examples of local neighborhoods from which training samples are drawn.

The prediction setting in the form of clauses is as follows:

Direct prediction clause: X5 :- X12.

Indirect prediction clause: X5 :- X12, X11, X16, X3, X15, X10.

The top curve shows the case of full observation (blue, on the top) and local geometry (gray are on the bottom).

Locality refers to which classes tend to appear together. In datasets with a local structure, concepts that strongly influence each other are also frequently seen together, while unrelated concepts appear together less often. By reasoning through appropriate intermediate variables, models trained on locally structured samples reduce bias. Combining LLMs with logic programming (LP) and deterministic back-propagation through these intermediates naturally enhances the accuracy of such hybrid systems.

The chart at the bottom of

Figure 7 compares direct prediction and free-generation estimators used as prompts. The model is prompted to predict a target variable either directly (direct prediction) or indirectly by first generating intermediate variables and their values (chain-based prediction). Prediction accuracy is measured by mean squared errors (MSE) between estimated and true conditional probabilities, calculated based on the number of training tokens per condition and estimator. The ribbons in the chart represent 95% confidence intervals.

Chain-of-thought reasoning benefits LLMs because:

1) without chaining, direct prediction can be inaccurate for some inferences, as relevant variables are rarely observed together during training; and

2) chain-of-thought reasoning improves estimation by sequentially linking local statistical dependencies that appear frequently in training.

7. Adversarial Interactions Between LLM and LP

An adversarial scenario in which a logic program and an LLM work together to solve a reasoning problem could involve a situation where they complement each other's weaknesses and strengths to identify inconsistencies or validate complex claims. A good example scenario is Fraud Detection in Financial Transactions. A financial institution needs to identify potentially fraudulent transactions based on a set of rules and patterns derived from historical data, regulations, and internal policies. Fraud detection is challenging due to the adversarial nature of fraudsters who constantly find new ways to bypass standard checks.

The logic program is responsible for checking compliance with known, rule-based patterns and detecting anomalies based on structured rules. For example, if a transaction exceeds $10,000 without a registered business justification, it is flagged. Transactions occurring at unusual hours for a particular account or region are flagged as suspicious. A series of transactions between accounts that lack common ownership are flagged if they involve round amounts and alternate back and forth.

An LLM augments this process by identifying and interpreting complex, less structured patterns, based on NL data (e.g., notes, emails, or text descriptions tied to transactions). The LLM can also adaptively recognize emerging fraud patterns, generalizing from recent case studies and text sources that describe new fraud techniques.

LP and LLM work together in an adversarial setup as follows:

- 1)

The logic program applies a set of predefined rules to detect straightforward cases of fraud. This step quickly flags transactions that match historical fraud patterns or violate specific transaction rules.

- 2)

LLM interpretation and cross-validation: For transactions that pass the initial LP checks, the LLM analyzes contextual information in the transaction metadata or associated communications (e.g., emails justifying the transactions, geographic locations mentioned, or references to businesses). It looks for semantic inconsistencies, vague justifications, or attempts to bypass standard language used in compliance statements.

In the adversarial scenario, a transaction is flagged as "suspicious" by the LP, but the reason provided in the transaction notes looks legitimate at first glance. The LLM, however, identifies inconsistencies in the language used. For example, it recognizes that the justification uses phrasing commonly associated with fraudulent attempts in other, similar cases. Conversely, the LLM might flag a transaction as unusual due to strange language in the metadata or patterns that resemble recent fraud cases. The LP then double-checks this against hard rules (e.g., verifying account ownership, transaction frequency) to see if any known rule has been violated.

If a transaction is flagged but lacks clear evidence under current rules, the LP updates its rules based on feedback from the LLM's analysis of new fraud patterns. This is iterative refinement. For example, if the LLM detects that recent fraud cases often involve certain phrases in transaction justifications, these patterns are incorporated into LP rules for future identification.

The adversarial aspect here also comes from fraudsters continually adapting their methods. The LLM can process recent cases described in news reports, legal documents, or company records and generate hypotheses for the LP to test. The LP then formalizes these patterns as new rules or updates existing ones.

In this adversarial scenario, the LLM provides flexible, adaptive reasoning over unstructured data and contextual clues, while the LP ensures strict compliance checks on rule-based, structured data. By working together:

- -

The LP enforces rigid constraints for fraud detection, catching straightforward cases.

- -

The LLM broadens the fraud detection scope by interpreting and adapting to new patterns based on natural language data and emerging case knowledge.

- -

The combined approach helps the financial institution stay ahead of evolving fraud tactics by incorporating both structured rule enforcement and adaptive pattern recognition.

This synergy between LP and LLM enhances accuracy in fraud detection, especially in cases where traditional rule-based systems alone might miss sophisticated or newly developed fraud techniques.

Let:

- F represent the set of all transactions.

- R represent the set of predefined fraud detection rules in the logic program.

- represent the LLM with capabilities for contextual analysis and natural language pattern recognition.

- S be the state of the system, comprising flagged transactions and new insights generated from the reasoning process.

We define two main processes: deductive filtering by the logic program) and abductive hypothesis generation by the LLM. Deductive Filtering by LP operates with a set of rules R designed to detect known patterns of fraudulent transactions. These rules are applied as follows:

Rule-Based Flagging: For each transaction t F, if t violates a rule r R, then t is flagged as suspicious. Let flag(t) denote that a transaction (t) has been flagged by LP based on rule r. flag(t) = r R s.t. r(t)). The LP outputs a set of flagged transactions Fflagged = { F|flag(t)} and a set of rules applied to each flagged transaction. Let denote the initial flagged set from rule-based filtering.

Abductive Hypothesis Generation by LLM: For transactions in and transactions that were not flagged by the LP but still appear anomalous in unstructured context, the LLM analyzes textual, contextual, and semantic information to generate hypotheses about potential fraud. The LLM may identify semantic patterns in justifications, transaction descriptions, or other natural language metadata. LLM is also expected to generate a hypothesis if it finds inconsistencies or patterns in the transaction's textual context that resemble recent fraud cases.

Let denote a hypothesis generated by the LLM about transaction t based on detected patterns or inconsistencies. The LLM then suggests new patterns as rules, based on hypotheses. It also refines the flagged set, creating a set Fhypothetical = { F| }.

The feedback loop for rule update and validation is formulated as follows. For rule update, the LLM provides feedback to the LP by suggesting new rules , which are generalized patterns extracted from the analysis. The logic program updates its rule base R R R, enhancing its detection capability for the next iteration.

Under iterative testing, the LP re-applies the updated rule set R to the transaction set

F to flag any additional transactions that may match the newly learned rules. This iterative process continues until no new transactions are flagged or until convergence criteria (e.g., detection threshold) are met.

repeat until

=

.

In this adversarial interaction, the LP and LLM achieve a complementary balance: the LP enforces structured, rule-based detection grounded in formal rules, while the LLM dynamically adapts to identify emerging patterns and continuously refine the detection process. Together, they enable robust fraud detection in an evolving, adversarial environment. This formalized interaction allows the system to iteratively evolve its rules, improving detection accuracy and adapting to novel fraud tactics that a strictly rule-based approach might overlook.

8. Evaluation

8.1. Datasets

We conducted various experiments using the FOLIO benchmark (Han et al., 2022), which includes a thousand training examples and a validation dataset sized at 20% of the training set. Each FOLIO problem consists of a set of premises (in natural language) and a conclusion (also in natural language), with the task being to determine whether the conclusion is True, False, or Uncertain given the premises. FOLIO also provides First-Order Logic translations for each premise and conclusion.

P-FOLIO (Han et al., 2024) expands on these tasks, introducing different levels of granularity and metrics to evaluate the reasoning capabilities of LLMs. Human-authored reasoning chains have shown to significantly improve LLM performance in logical reasoning via many-shot prompting and fine-tuning.

Additionally, we utilized the CLUTRR and ProofWriter datasets, both designed for logical reasoning tasks that apply commonsense or predefined rules. For CLUTRR, we selected 235 test instances requiring 2–6 steps of rule application. From ProofWriter, we selected instances needing 3–5 steps of reasoning from the open-world assumption subset, totaling 300 instances with balanced labels.

The SimpleQA dataset (OpenAI, 2024) focuses on short, fact-based queries, which narrows the scope of evaluation but simplifies the assessment of factuality. SimpleQA was constructed to prioritize high accuracy, with reference answers supported by sources from two independent AI trainers, and questions formulated to facilitate clear grading of predicted answers. As a factuality benchmark, SimpleQA allows for testing calibration—the degree to which a language model can accurately reflect its knowledge. Calibration is assessed by prompting the model to state its confidence level (as a percentage) alongside its answer. By plotting the correlation between the model’s stated confidence and actual accuracy, we evaluate calibration. Ideally, a well-calibrated model's accuracy should match its stated confidence; for instance, if the model expresses 75% confidence across a set of answers, its accuracy would indeed be 75% for that set.

8.2. Competitive Systems

WM-Neurosymbolic (Wang et al., 2023) enhances LLMs with an external working memory, forming a neuro-symbolic framework for multi-step rule application to boost reasoning capabilities. This working memory stores facts and rules in both natural language and symbolic representations, supporting accurate retrieval during rule application. After storing all input facts and rules in memory, the framework iteratively applies symbolic rule grounding through predicate and variable matching, followed by rule implementation via the LLM.

Scratchpad-CoT (Nye et al., 2021) facilitates chain-of-thought reasoning using a "scratchpad" approach, where transformers are trained to break down multi-step computations by emitting intermediate steps in a separate space. On tasks ranging from long addition to program execution, scratchpads significantly improve LLMs' ability to perform stepwise computations.

Logic-LM (Pan et al., 2023) leverages LLMs to translate natural language problems into symbolic formulations, then uses symbolic solvers like the Z3 theorem prover (De Moura and Bjørner, 2008) to perform deterministic inference.

LLM-ARC (Kalyanpur et al., 2024) combines LLMs with an Automated Reasoning Critic (ARC) in a neuro-symbolic framework aimed at advancing reasoning. Here, the LLM Actor generates declarative logic programs and creates tests for semantic accuracy, while the ARC evaluates the code, executes tests, and provides feedback on failures to iteratively refine the model.

LINC (Olausson et al., 2023) uses an LLM as a semantic parser to translate premises and conclusions from natural language into first-order logic expressions, which are then processed by an external theorem prover to carry out deductive inference symbolically.

In

Table 4, we compare our adversarial system with two types of baselines: CoT-based methods (

grayed rows), symbolic-based methods(Logic-LM) and state-of-the-art neuro-symbolic systems (LINC, WM-Neurosymbolic, and LLM-ARC), highlighted in

turquoise.

When our LP based method does not return an answer caused by symbolic formulation errors, we use CoT based approach (

Section 6). We observe that our adversarial method demonstrates consistent performance overall with the competitive neuro-symbolic systems. However, we underperform LINC on ProofWriter, WM-Neurosymbolic on CLUTRR and LLM-ARC on FOLIO.

Our adversarial neuro-symbolic system is effective on top of different LLMs with varying abilities in symbolic parsing and one-step rule application. Specifically, GPT-3.5-based setting delivers a noticeable boost on computational logical problems (CLUTRR). At the same time, GPT-4 has a great accuracy at more human-related tasks (ProofWriter). Our adversarial approach leverages an advancement of LLMs; one can expect that it will efficiently complement future LLM systems. Compared to previous symbolic-based methods that perform both rule grounding and implementation either symbolically or by LLMs, our framework exhibits improvement. Adversarial LLM-LP integration demonstrates flexibility and robustness, separately implementing rule grounding and execution.

We proceed to our evaluation on a specific dataset with controversial, more complex problems which require a number of knowledge sources to make decision upon. The computational definition of a

controversial is based on inconsistent or even opposite results obtained by an LLM on a given problem. We automatically classify such problems from the evaluation sets, forming datasets FOLIO_

controversial (about 1/7 of FOLIO), CLUTRR_

controversial (about 1/10 of CLUTRR)

, and ProofWriter_

controversial (about 1/7 of ProofWriter). We run WM-Neurosymbolic and our adversarial system on these subsets and provide the results in

Table 5. Our adversarial system outperforms WM-Neurosymbolic in two out of three datasets (other than ProofWriter_

controversial).

9. Discussion

The neuro-symbolic framework for rule application can incorporate an external working memory that stores both facts and rules in natural language and symbolic formats, supporting accurate tracking throughout the reasoning process (Wang et al. 2024). This memory enables iterative application of symbolic rule grounding and LLM-based rule execution. During symbolic rule grounding, the framework matches rule predicates and variables with relevant facts to determine which rules are applicable at each step. Experimental results indicate the framework's effectiveness and robustness across various reasoning tasks.

LLMs have shown exceptional performance across many tasks but often struggle with complex reasoning that requires retention or grounding of long-term information from context or interaction history (Touvron et al., 2023). While extending LLMs' context length is one approach, recent advances involve augmenting LLMs with external memory. For instance, Park et al. (2023) integrate external memory modules for LLMs in extended dialogues to improve interaction quality, while Wang et al. (2024) represent long-form context in memory for retrieval in knowledge-intensive tasks.

However, existing memory architectures typically store only natural language or parametric entries, making accurate referencing and revision challenging. To address this, symbolic memory has been proposed. ChatDB (Hu et al., 2023) utilizes a structured item database as symbolic memory for precise information recording, and Yoneda et al. (2023) developed symbolic world memory to track robot states for embodied reasoning. Our approach leverages external memory to store both natural language and symbolic facts and rules, enhancing precise rule grounding for multi-step applications.

Additionally, Ranaldi and Freitas (2024) fine-tuned LLMs with logical reasoning data to improve inference capabilities. LLMs have been applied as soft logic reasoners, and a range of prompting techniques have been proposed to enhance performance in this domain (Zhou et al., 2024). Using LLMs as semantic parsers has also shown to improve reasoning accuracy (Olausson et al., 2023) by first converting natural language reasoning problems into logical forms before using an inference engine for the final output.

Wu et al. (2023) present a method for creating tricky natural language instructions that cause code-generating LLMs to produce code that works correctly but contains security vulnerabilities. Their approach uses an evolutionary search process and a carefully designed loss function. The system automatically finds harmless-looking prefixes or suffixes to add to a user’s prompt — text that appears completely innocent and unrelated to coding — but that still strongly pushes the model toward producing insecure code. This makes it possible to perform near worst-case “red-teaming” tests in realistic situations, where users give prompts in plain natural language.

In this book we will treat reasoning in a broader perspective. In Galitsky (2024) we proposed reasoning applications designed to generate diagnostic assessments for input financial indicators, derived from labels (e.g., risk categories, market events, regulatory breaches, and/or portfolio conditions) associated with previously observed cases. The system can construct extended discourse trees that represent multiple discourse structures across varying levels of granularity (e.g., full report, section, paragraph, sentence, phrase, or token) for historical financial cases, along with the rhetorical relations linking those structures. New financial data (e.g., submitted via the autonomous agent) can be parsed to identify relevant fragments and the rhetorical relations among them. These fragments are then matched to fragments of prior cases by aligning nodes within the extended discourse tree, enabling the system to produce context-aware and historically grounded risk or compliance diagnoses. In the consecutive chapters we

10. Conclusions

Our experiments demonstrate the framework’s superiority over CoT-based, symbolic based, and LLM-LP collaboration baselines, and show its robustness across various rule application steps and settings. In the future, we will extend our framework to incorporate more backbone LLMs and datasets, especially on more complex and long-term reasoning tasks.

There is growing recognition in the LLM audience that LLM-only solutions do not meet the standard for production applications that require a high degree of accuracy, consistency and explicability. More specifically, current state-of the-art LLMs are known to struggle for problems involving precise logical reasoning, planning and constraint solving. As a result, there is a rise in the development of hybrid neuro-symbolic systems, where the reasoning is offloaded to a symbolic solver, and the LLM is used at the interface layer to map between unstructured data (text) and structured logical representations. Unlike standard tools or simple APIs, integration between an LLM and a symbolic reasoner can be fairly sophisticated as the reasoning engine has its own world model and decision procedures.

The adversarial interaction between LLMs and logic programs significantly enhances the accuracy of solving complex logical problems. This integration creates a dynamic, adaptive framework that leverages the structured, rule-based rigor of logic programming and the flexible, context-aware reasoning capabilities of LLMs. The LP provides a formal foundation for consistent rule enforcement, ensuring that well-defined logical constraints are respected, while the LLM contributes by identifying patterns and drawing inferences from nuanced or unstructured data. Through this interaction, the two systems address each other's limitations—LLMs can mitigate LP's rigidity when it encounters cases outside of its predefined rules, and LP can counterbalance the occasional ambiguity in LLM predictions, leading to a more robust and reliable reasoning process.

In an adversarial setup, the LLM and LP act as checks and balances, where each system critiques or validates the outputs of the other. This interplay is particularly beneficial in complex reasoning tasks like fraud detection or scientific hypothesis evaluation, where new patterns and irregularities often arise. The LP detects standard rule violations, while the LLM’s adaptability enables it to flag novel anomalies or emerging trends that do not yet have formalized rules. By iteratively refining outputs based on each other’s feedback, the combined neuro-symbolic system not only improves accuracy in real-time but also learns to adapt to evolving patterns or requirements, a feature that pure logic-based systems would find challenging to achieve.

Moreover, this adversarial approach enhances the transparency and explainability of the system's outputs. The structured logic program offers clear, traceable reasoning steps, allowing users to follow the logic behind conclusions, while the LLM supplements this with insights from broader contextual or probabilistic knowledge. This combination supports interpretability, which is essential in fields where understanding the reasoning process is as important as the outcome. Over time, the system’s rules and logic pathways are iteratively refined and expanded based on both structured feedback and natural language data, progressively increasing its depth and reliability. This iterative refinement not only improves immediate accuracy but also builds a richer, more sophisticated logic framework, positioning the LLM-LP system as a powerful tool for tackling increasingly complex and evolving reasoning tasks.

References

- Berglund L, Meg Tong, Max Kaufmann, Mikita Balesni, Asa Cooper Stickland, Tomasz Korbak, and Owain Evans. 2023. The reversal curse: Llms trained on" a is b" fail to learn" b is a". arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.12288.

- Blei DM and J. D. Lafferty, “A correlated topic model of Science,” The Annals of Applied Statistics, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 17– 35, 2007.

- Creswell A, Murray Shanahan, and Irina Higgins. 2022. Selection-inference: Exploiting large language models for interpretable logical reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.09712.

- Darwiche A; Pearl, Judea (1997-01-01). "On the logic of iterated belief revision". Artificial Intelligence. 89 (1): 1–29.

- Galitsky B (2024) Multi case-based reasoning by syntactic-semantic alignment and discourse analysis. US Patent 12,106,054.

- Galitsky B (2025) Employing LLM to solve Constraint Satisfaction. Health Applications of Neuro Symbolic AI.

- Gur I, Hiroki Furuta, Austin Huang, Mustafa Safdari, Yutaka Matsuo, Douglas Eck, and Aleksandra Faust. A real-world web agent with planning, long context understanding, and program synthesis, 2024. arXiv 2307.12856.

- Han S, Hailey Schoelkopf, Yilun Zhao, Zhenting Qi, Martin Riddell, Luke Benson, Lucy Sun, Ekaterina Zubova, Yujie Qiao, Matthew Burtell, David Peng, Jonathan Fan, Yixin Liu, Brian Wong, Malcolm Sailor, Ansong Ni, Linyong Nan, Jungo Kasai, Tao Yu, Rui Zhang, Shafiq Joty, Alexander R. Fabbri, Wojciech Kryscinski, Xi Victoria Lin, Caiming Xiong, and Dragomir Radev. 2022. Folio: Natural language reasoning with first-order logic.

- Hu C, Jie Fu, Chenzhuang Du, Simian Luo, Junbo Zhao, and Hang Zhao. 2023. ChatDB: Augmenting LLMs with databases as their symbolic memory. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.03901.

- Kojima T, Shixiang Shane Gu, Machel Reid, Yutaka Matsuo, and Yusuke Iwasawa. 2022. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Makinson D (1985). How to give up: A survey of some formal aspects of the logic of theory change. Synthese, 62:347–363.

- Mao, J., Gan, C., Kohli, P., Tenenbaum, J.B., Wu, J.: The neuro-symbolic concept learner: Interpreting scenes, words, and sentences from natural supervision (2019).

- Mitchell M. 2021. Abstraction and analogy making in artificial intelligence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1505(1):79–101.

- Nye M, Anders Johan Andreassen, Guy Gur-Ari, Henryk Michalewski, Jacob Austin, David Bieber, David Dohan, Aitor Lewkowycz, Maarten Bosma, David Luan 2021. Show your work: Scratch pads for intermediate computation with language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.00114.Top of Form.

- Olausson T, Alex Gu, Ben Lipkin, Cedegao Zhang, Armando Solar-Lezama, Joshua Tenenbaum, and Roger Levy. LINC: A neurosymbolic approach for logical reasoning by combining language models with first order logic provers. EMNLP pages 5153–5176, Singapore, December 2023.

- OpenAI (2024) SimpleQA https://openai.com/index/introducing-simpleqa/.

- Pan, L., Albalak, A., Wang, X., Wang, W.: Logic-LM (2023) Empowering large language models with symbolic solvers for faithful logical reasoning. In: Bouamor, H., Pino, J., Bali, K. (eds.) Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023. pp. 3806–3824.

- Park JS, Joseph O’Brien, Carrie Jun Cai, Meredith Ringel Morris, Percy Liang, and Michael S Bern stein. 2023. Generative agents: Interactive simulacra of human behavior. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, pages 1–22.

- Prystawski B, Michael Y. Li, and Noah D. Goodman. 2023. Why think step by step? reasoning emerges from the locality of experience. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023).

- Puga, J., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. Bayes' theorem. Nat Methods 12, 277–278 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Ranaldi L and Andre Freitas. 2024. Aligning large and small language models via chain-of-thought reasoning. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 1812–1827.

- Riguzzi, Fabrizio; Swift, Theresa (2018-09-01), "A survey of probabilistic logic programming", Declarative Logic Programming: Theory, Systems, and Applications, ACM, pp. 185–228, doi:10.1145/3191315.3191319, ISBN 978-1-970001-99-0, S2CID 70180651, retrieved 2023-10-25.

- Rozière B, Naman Goyal, Eric Hambro, Faisal Azhar, et al. 2023. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971.

- Sarker MK, Lu Zhou, Aaron Eberhart, Pascal Hitzler (2021) Neuro-Symbolic Artificial Intelligence: Current Trends. arXiv:2105.05330.

- Simeng Han, Aaron Yu, Rui Shen, Zhenting Qi, Martin Riddell, Wenfei Zhou, Yujie Qiao, Yilun Zhao, Semih Yavuz, Ye Liu, Shafiq Joty, Yingbo Zhou, Caiming Xiong, Dragomir Radev, Rex Ying, Arman Cohan (2024) P-FOLIO: Evaluating and Improving Logical Reasoning with Abundant Human-Written Reasoning Chains. arXiv:2410.09207.

- Touvron H, Thibaut Lavril, Gautier Izacard, Xavier Martinet, Marie-Anne Lachaux, Timothée Lacroix,.

- Vakharia P, Abigail Kufeldt, Max Meyers, Ian Lane, and Leilani H. Gilpin (2024) ProSLM : A Prolog Synergized Language Model for explainable Domain Specific Knowledge Based Question Answering.

- Wan, Z., Liu, C.K., Yang, H., Li, C., You, H., Fu, Y., Wan, C., Krishna, T., Lin, Y., Raychowdhury, A.: Towards cognitive ai systems: a survey and prospective on neuro-symbolic AI (2024).

- Wang S, Zhongyu Wei, Yejin Choi, Xiang Ren (2024) Symbolic Working Memory Enhances Language Models for Complex Rule Application. arXiv:2408.13654.

- Wang W, Li Dong, Hao Cheng, Xiaodong Liu, Xifeng Yan, Jianfeng Gao, and Furu Wei. 2024. Augmenting language models with long-term memory. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36.

- Wei J, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, brian ichter, Fei Xia, Ed H. Chi, Quoc V Le, and Denny Zhou. (2022) Chain of thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Wu F, Xiaogeng Liu and Chaowei Xiao(2023) DeceptPrompt: Exploiting LLM-driven Code Generation via Adversarial Natural Language Instructions. arXiv:2312.04730v2.

- Yoneda T, Jiading Fang, Peng Li, Huanyu Zhang, Tianchong Jiang, Shengjie Lin, Ben Picker, David.

- Yunis, Hongyuan Mei, and Matthew R Walter. 2023. Statler: State-maintaining language models for embodied reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.17840.

- Zhou P, Jay Pujara, Xiang Ren, Xinyun Chen, Heng Tze Cheng, Quoc V. Le, Ed H. Chi, Denny Zhou, Swaroop Mishra, and Huaixiu Steven Zheng. 2024. Self-discover: Large language models self-compose reasoning structures.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).