1. Introduction

Aromatic compounds, including phenol, are among the most common organic pollutants in effluents from the paper, plastic, petroleum, dye, resin and wood industries [

1,

2]. Phenol is considered as toxic and mutagenic compound, which requires the development of effective technology to remove it from wastewater [

3,

4]. For this, various methods have been developed such as solvent extraction, microbial degradation, adsorption on activated carbon and chemical oxidation [

5]. Extraction methods are incomplete and expensive, while adsorption and oxidation treatments are extremely expensive for low effluent concentrations [

6,

7].

Wastewater treatment with enzymes is an alternative to traditional methods. The application of enzymes, such as peroxidases, laccase and tyrosinase for the removal of phenol from wastewater, has a number of advantages over conventional biological treatments including: the ability to treat a wide range of contaminant concentrations, pH, temperature, high reaction rates, and high specificity of enzymes for their substrates [

2,

8,

9]. Tyrosinase is widely used for the elimination of phenol. It is a copper metalloenzyme widely distributed in nature [

10]. In the present study, tyrosinase was obtained from button mushroom (

Agaricus bisporus) which is considered to be the major natural source of this enzyme [

11]. It catalyzes two very distinct reactions, the hydroxylation of monophenols to o-diphenols called cresolase activity and the oxidation of o-diphenols to o-quinones called catecholase activity, with consumption of molecular oxygen [

12,

13]. Tyrosinase is most often immobilized in supports for reuse and due to its greater thermal stability compared to its free form [

14]. Calcium alginate is one of the most commonly used matrices for enzyme immobilization due to its advantages such as good biocompatibility, non-toxicity, cost-effectiveness, low cost, availability and simplicity of preparation [

15,

16].

Therefore, the present study investigates for the first time the oxidation of phenol in a batch system using mushroom tyrosinase immobilized in calcium alginate beads and compares its performance with that of the free enzyme. The effects of phenol concentration, temperature, pH, and calcium alginate bead diameter were systematically examined to determine the optimal physicochemical conditions for the maximum removal of phenol from wastewater.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Material

Fresh white button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) purchased from the local market was used as a source of tyrosinase. Phenol (Prolabo) was used as substrate. The other chemical reagents are of an analytical grade.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of Tyrosinase Crude Extract

Tyrosinase was prepared according to the method described by Gouzi [

17]. Briefly, 260 g of button mushrooms, previously washed with distilled water, air-dried, and cooled to −15 °C, were crushed for 2 min in a blender containing 430 mL of acetone (99.5%) pre-chilled at −15 °C to remove water and phenolic compounds. The resulting homogenate was filtered and manually pressed through three layers of cheesecloth until a dry residue (acetone powder) was obtained. The acetone powder (23 g) was cooled by placing it in contact with ice for at least 4 h. The cold pulp was then suspended in 235 mL of distilled water using a blender and left overnight at approximately 5 °C. The suspension was filtered through three layers of cheesecloth, and the filtrate was subsequently centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min to remove residual particles. The resulting supernatant (140 mL) constituted the crude tyrosinase extract, which was aliquoted into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and stored at −15 °C until use.

2.2.2. Immobilization of Tyrosinase in Ca-Alginate Beads

For the preparation of calcium alginate beads, sodium alginate (0.25 g) was dissolved in warm 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), followed by the addition of tyrosinase solution (140 EU/mL) to a final volume of 10 mL. The solutions were thoroughly mixed using a magnetic stirrer until a transparent gel was formed. The resulting mixtures were then extruded dropwise into a cold, stirred 0.2 M CaCl

2 solution using a syringe fitted with a needle to obtain uniformly sized calcium alginate beads containing entrapped tyrosinase [

18]. The beads were allowed to harden overnight in the CaCl

2 solution, after which they were collected by filtration and washed with distilled water. The Ca-alginate beads were stored at 4 °C until further use. Immobilization efficiency was evaluated in terms of the efficiency factor (

ηenz) which was calculated from the maximum reaction rates of the immobilized tyrosinase in relation to the free tyrosinase [

19].

2.2.3. Determination of Tyrosinase Activity

The kinetics of phenol oxidation was carried out in a 250 ml Erlenmeyer (“batch” reactor) immersed in a water bath set at 35 °C and stirred continuously at 150 rpm, The reaction volume medium containing 29 mL of phenol as substrate at 2.5 mM prepared in phosphate buffer (pH 6.0-0.05 M) and 1 mL of crude tyrosinase extract or 220 tyrosinase immobilized in alginate beads. 1 mL from the reaction medium was taken every minute in order to monitor the evolution of the formation of o-benzoquinone. The absorbance was measured by UV-Visible spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU UV MIN-1240) at 400 nm [

7]. The initial velocity is estimated from the linear part of the absorbance versus time curve [

17]. In spectrophotometry an enzyme unit (EU) is defined as the quantity of enzyme that causes the increase in absorbance by 0.001 min

-1 [

20].

2.2.4. Kinetic Studies of Phenol Removal

The kinetic behavior of phenol oxidation was investigated in a batch reactor by measuring the initial reaction rates under standard operating conditions. Experiments were conducted at an initial phenol concentration of 2.5 mM. Samples consisting of 1 mL of free tyrosinase or 220 Ca-alginate beads containing immobilized tyrosinase were incubated in 29 mL of phenol solution with concentrations ranging from 0.0625 to 5 mM. The reactions were carried out in 0.05 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 6.0 and a temperature of 35 °C.The kinetic parameters, the Michaelis-Menten constant (K

m) and the maximum reaction velocity (V

max), were determined using the double-reciprocal Lineweaver–Burk plot [

21].

2.2.5. Effect of Temperature on Soluble and Immobilized Tyrosinase

The effect of temperature on the activity of free and immobilized tyrosinase was evaluated by measuring the initial rate of phenol oxidation at temperatures ranging from 30 to 70 °C under standard assay conditions.

Arrhenius’ law is commonly used to describe the temperature dependence of initial rate values. It is expressed algebraically as [

22]:

where

k0 is the Arrhenius constant,

Ea the activation energy (kJ/mol),

R the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol.K) and

T is the absolute temperature. The activation energy can be estimated by the slope of linear regression analysis of the natural logarithm of initial rate (v

0) versus the reciprocal of the absolute temperature, within a temperature range that does not induce enzyme denaturation.

2.2.6. Effects of pH

Phenol degradation (2.5 mM) was investigated at 35 °C over a pH range of 4.0–8.0 using free and immobilized tyrosinase, with acetate buffer (pH 4.0–5.6) and phosphate buffer (pH 6.0–8.0) used for pH adjustment. The effect of temperature on enzymatic degradation was also evaluated by varying the reaction temperature from 30 to 70 °C, with phenol solutions prepared in 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and treated with either free or immobilized tyrosinase.

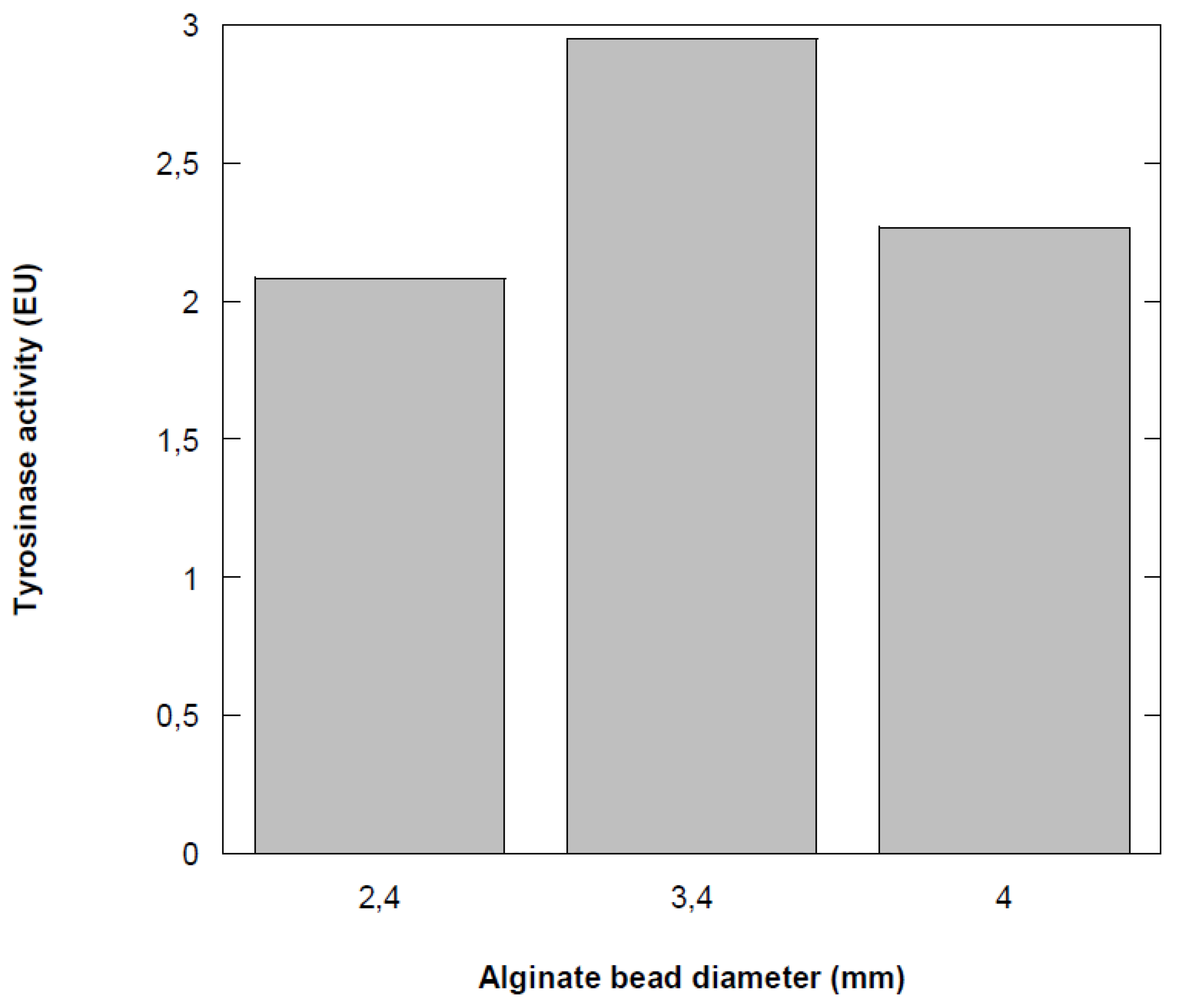

2.2.7. Effect of Tyrosinase Ca-Alginate Bead Size

The effect of Ca-alginate bead size on the initial rate of phenol oxidation (2.5 mM) catalyzed by immobilized tyrosinase was investigated. Beads with three different diameters (2.4, 3.4, and 4.0 mm) were prepared from 10 mL of a 2.5% (w/v) sodium alginate solution containing 1 mL of crude enzyme extract. The beads were transferred to an Erlenmeyer flask containing 29 mL of phenol solution (2.5 mM), and the reaction was carried out at 35 °C and pH 6.0 in 0.05 M phosphate buffer.

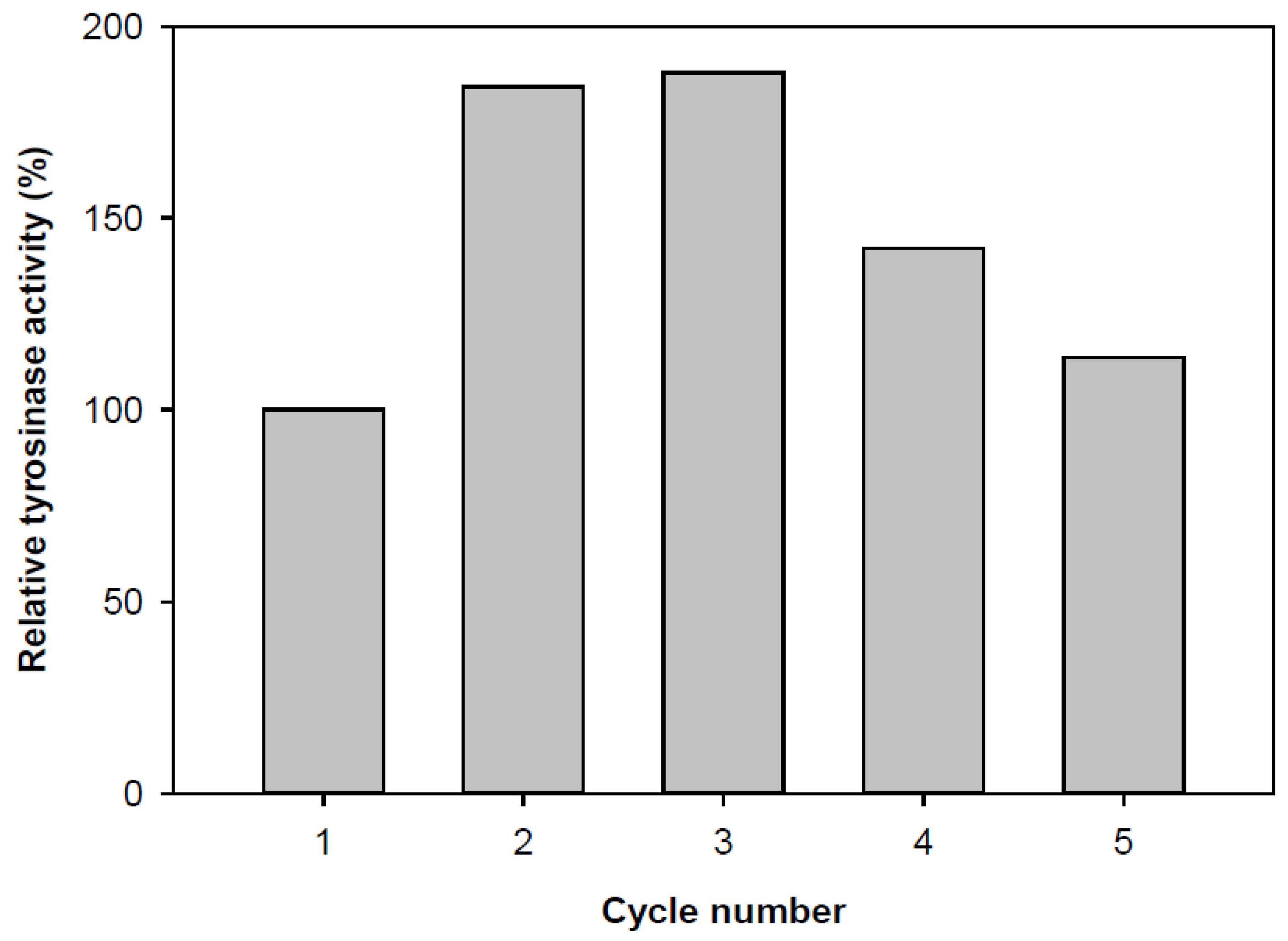

2.2.8. Reusability of the Immobilized Beads

One of the advantages of using immobilized enzyme is that they can be used repeatedly. Therefore, the reusability of immobilized tyrosinase beads was assessed by performing five consecutive phenol degradation cycles with the same beads. After each cycle, the beads were washed with 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), and their residual activity was measured at pH 6.0 and 35 °C using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer. The initial activity was defined as 100%, and activities in subsequent cycles were expressed as percentages of this value.

2.2.9. Data Analysis

All data analyses were performed using linear and non-linear regression fittings with the software programs KaleidaGraph (Copyright 1986-2005, Synergy Software) and SigmaPlot Version 14.5 (Copyright © 2020, Systat Software, Inc.) for Windows. All activity analyses conducted in this study were carried out in triplicate, and the average values of the data were considered.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Extraction of Tyrosinase from Agaricus Bisporus

The slightly modified method developed by Gouzi [

17] for the extraction of tyrosinase from

Agaricus bisporus was simple, rapid, and resulted in high enzymatic activity. The extraction procedure involves the preparation of acetone powder to remove water, endogenous phenols, and pigments. The crude extract exhibited significant activity towards phenol as a substrate, with a catalytic activity of 140 EU/ml (pH 6.0; 35 °C). Based on these findings, it can be concluded that this enzyme can be classified as a monophenol monooxygenase, commonly known as tyrosinase [

23].

3.2. Effect of pH

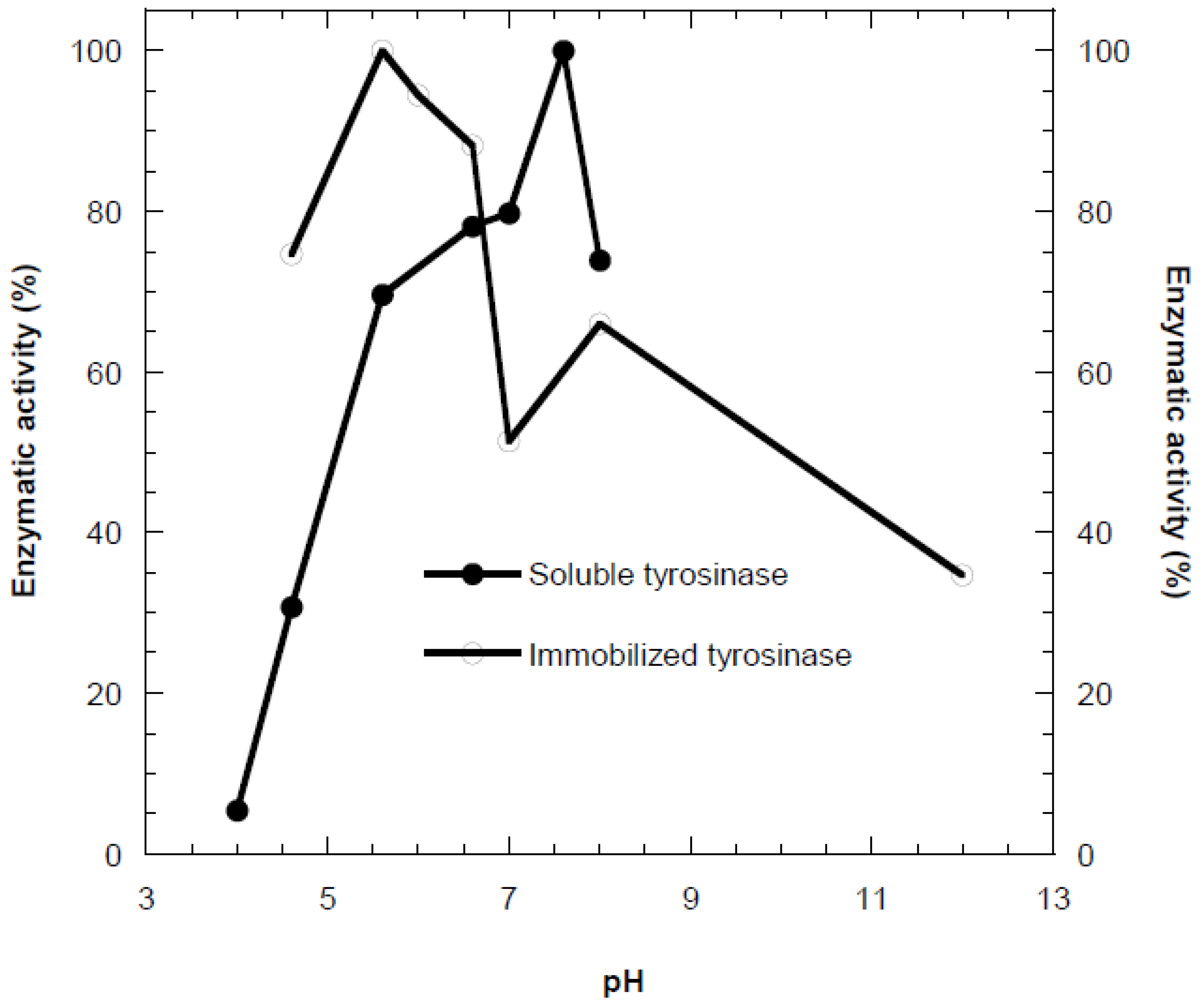

The effect of pH on the activity of free and immobilized tyrosinase was examined in the pH range of 4.0–8.0 at 35 °C (

Figure 1). Immobilization in calcium alginate resulted in a shift of the optimum pH by approximately two units toward the acidic region compared to the free enzyme. This behavior is mainly attributed to enzyme-support interactions, including ionic and polar interactions and hydrogen bonding within the alginate matrix. At alkaline pH values, electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged alginate and phenolate ions limits substrate diffusion toward the active sites. In contrast, under acidic conditions, phenol carries a partial positive charge, which enhances its attraction to the negatively charged support and improves catalytic efficiency [

18]. Similar acidic shifts in optimum pH upon tyrosinase immobilization have been reported in previous studies [

24,

25,

26].

3.3. Effect of Temperature

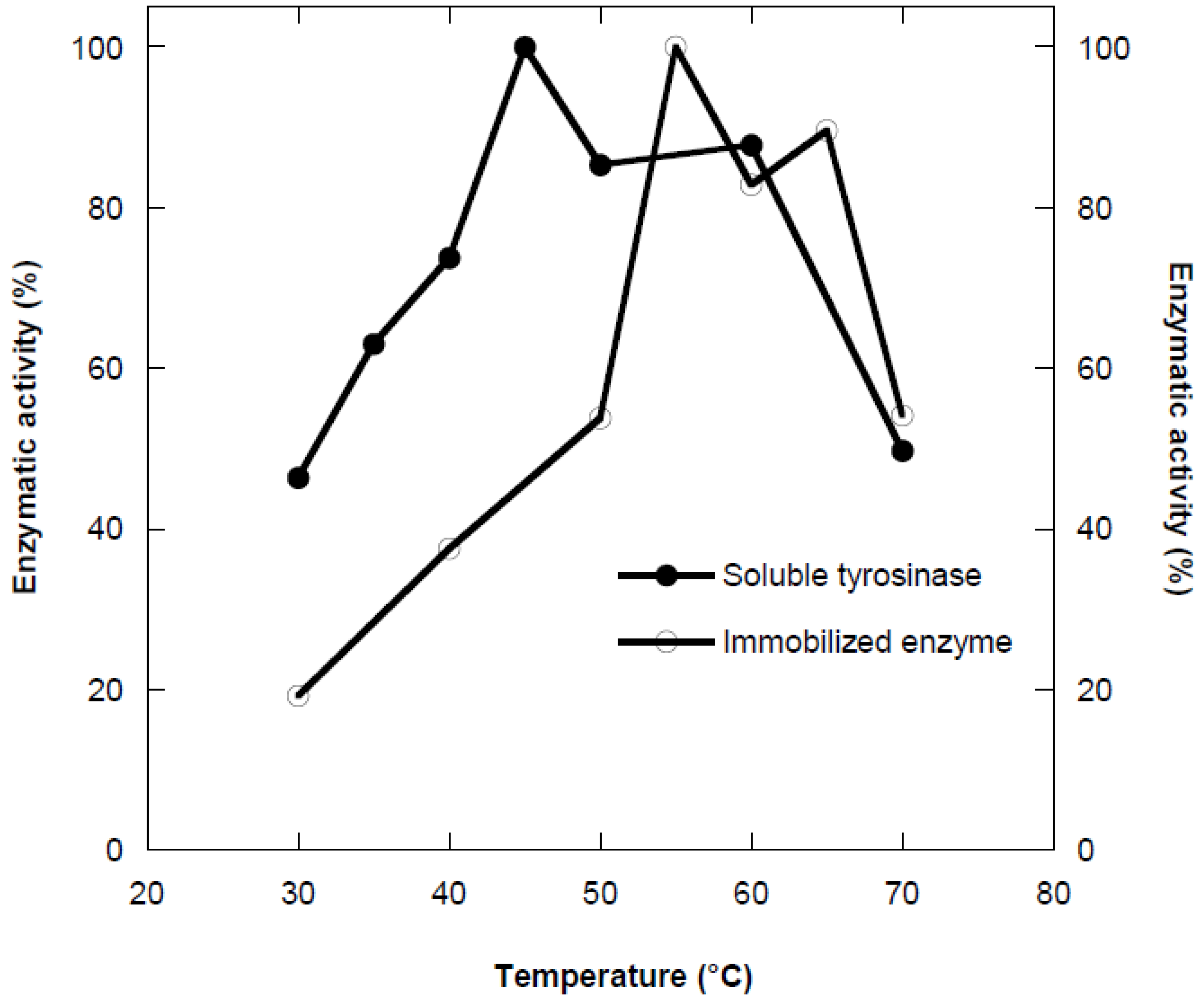

Temperature is one of the most important factors affecting enzyme activity. The activities obtained in a temperature range of 30-70 °C were expressed as percentage of the maximum activity. As shown in the

Figure 2, the optimum temperature was found to be 45 °C for free enzyme. The optimum reaction temperature for immobilized tyrosinase on Ca-alginate was determined as 55 °C.

This shift could be explained as multi-point ionic interaction between enzymes and polymeric matrix due to the activation energy of the enzyme to reorganize an optimum conformation for binding to its substrate. One of the main reasons for high thermal resistance of immobilized enzyme was its stability to various deactivating force due to restricted conformational mobility of the molecules following immobilization. Generally, the high temperature is preferable and essential for most of the enzyme activity since high temperature improves the conversion rates. Moreover, high temperature increases the substrate solubility as well as it reduces the microbial contamination.

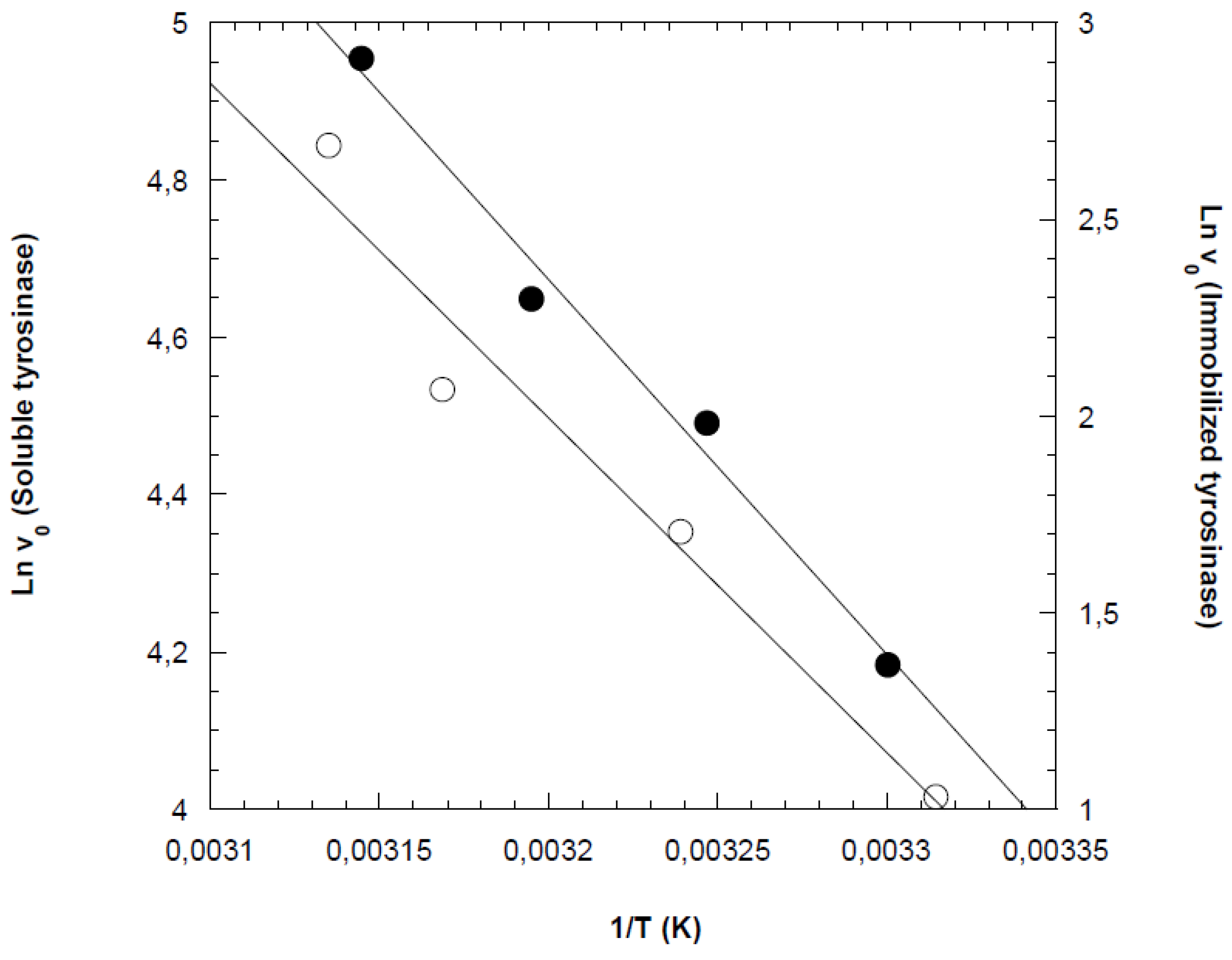

Arrhenius plots were constructed using the initial reaction rates obtained from the previous experiments, as shown in

Figure 3 for both free and cross-linked tyrosinases. From the slopes of the Arrhenius plots, the activation energies for phenol oxidation by free and immobilized tyrosinases were determined to be 39.5 kJ/mol and 50.4 kJ/mol, respectively. This result was consistent with expectations, as immobilization typically reduces the conformational stability of the enzyme. As a result, higher activation energy is required to achieve the correct enzyme conformation for effective substrate binding [

18,

27].

3.4. The Kinetic Parameters

K

m and V

max, for both free and immobilized enzymes were determined by varying phenol concentrations at a constant temperature and pH.

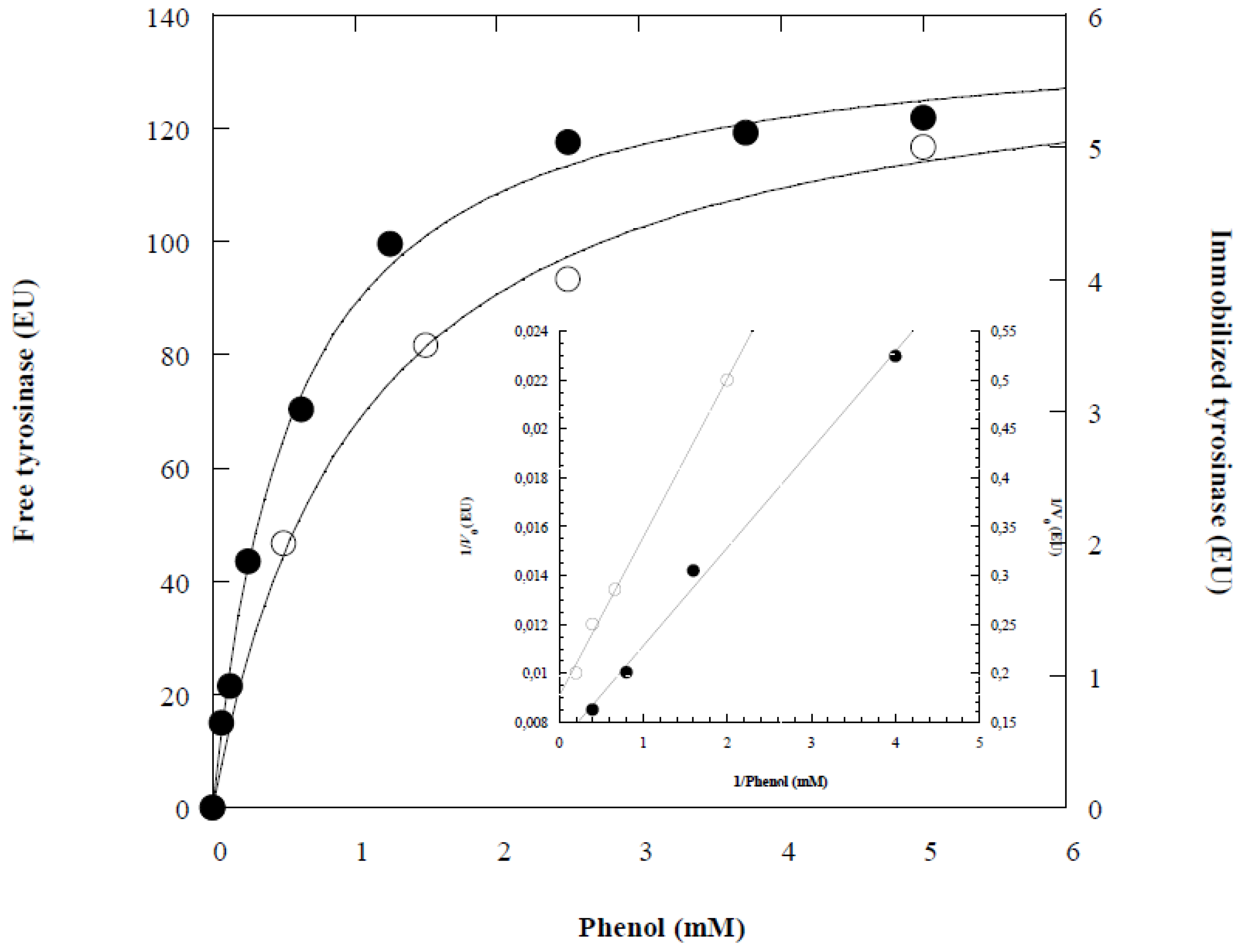

Figure 4 presents the relation between initial rate and phenol concentration for the free and immobilized tyrosinase.

Using Lineweaver-Burk method (

Figure 4), the Michaelis constant K

m and V

max of the free tyrosinase were 0.56 mM and 139.02 EU, respectively. In contrast, for the immobilized enzyme on Ca-alginate, K

mApp and V

maxApp were 1.04 mM and 5.96 EU, respectively (

Table 1). The increase in K

m for the immobilized enzyme may be attributed to conformational changes in the enzyme structure or due to the lower accessibility of the active site of an immobilized enzyme [

1,

15,

28]. The decrease in V

max value indicating lower reaction velocity might be due to change in the conformation of enzyme following immobilization or diffusional limitation of the substrate to the active site of the enzyme as reported in the literature [

25,

26].

Furthermore, the immobilized enzyme is surrounded by a different environment compared to the free enzyme, which can significantly impact its kinetic parameters. Additionally, the lower transporting of the substrate and products into and out the gel beads [

13,

29]. The decrease of the efficiency factor, ratio V

MaxApp/V

max shows that there was a decrease in diffusion efficiency of the substrate due to the immobilization process [

1].

3.5. Effect of Ca-Alginate Bead Size

The results depicted in

Figure 5 showed that the activity of the immobilized enzyme varies with bead diameter. The activity of immobilized tyrosinase is maximal at a diameter of 3.4 mm, with a decrease of approximately 30% on either side of this diameter. In the immobilized tyrosinase system, phenol must diffuse to enable the oxidation reaction, so the final size of the immobilization support significantly impacts enzyme activity. Previous studies have demonstrated that enzyme activity increases as bead size decreases, due to a reduction in mass transfer resistance [

30]. Additionally, decreasing the diameter of the alginate beads may reduce enzyme leakage [

31,

32]. These results can be explained by diffusional limitations that lead to the establishment of a concentration gradient of phenol within the particle. Berset [

33] reported that increasing the rate of mass transfer can be achieved by more vigorous agitation of the reaction medium or by reducing the diameter of the support particles, which decreases the thickness of the boundary layer.

3.6. Reuse Numbers

The reusability of immobilized tyrosinase was evaluated due to its importance for repeated applications in a batch reactor. Immobilization was performed using Ca-alginate, and the enzyme was reused up to five times. The residual activity of the immobilized enzyme on Ca-alginate gel beads during repeated use is shown in

Figure 6. The enzyme activity varied depending on the number of reuse cycles. Notably, it increased almost twofold after the second cycle, but after the fifth cycle, the activity returned to its initial value. The observed decrease in enzymatic oxidation yield can be attributed to the prolonged exposure of the enzyme to phenol degradation products [

4].

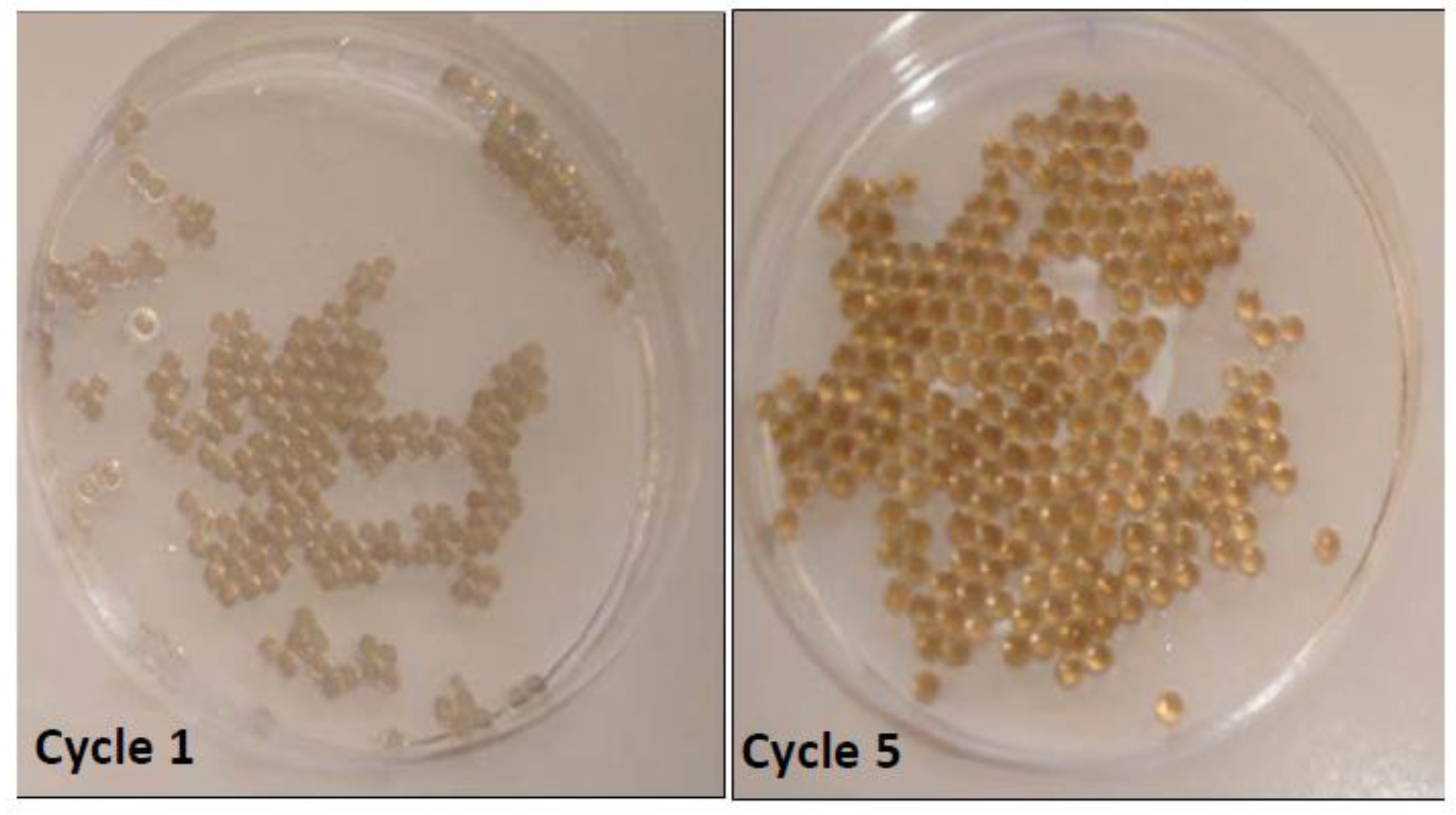

After two reuse cycles, an increase in the diameter of the alginate beads was observed, attributed to the swelling of the gel. This swelling facilitated the internal diffusion of the substrate, enhancing its accessibility to the enzyme (

Figure 7).

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, tyrosinase was successfully extracted from Agaricus bisporus using a simple and efficient method that yielded high phenolase activity. The enzyme demonstrated a strong affinity for phenol as a substrate, compared to the immobilized enzyme in alginate beads, which exhibited lower affinity. Furthermore, enzyme immobilization enhanced its thermal stability and shifted the optimal pH towards more acidic conditions.

Thermodynamic analysis using the Arrhenius plot revealed that immobilization resulted in a decrease in the enzyme’s conformational stability, as evidenced by an increase in the activation energy for phenol oxidation. These findings underscore the potential of mushroom tyrosinase as an effective biocatalyst for phenol removal in wastewater treatment applications.

Author Contributions

Experiments and Data Analysis: S.L. and H.G.; Methodology and Writing: H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We warmly thank Professor Hicham GOUZI for its contribution to the work presented here. We also thank the reviewers for their constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests in this work.

References

- Cadena, P. G., Wiggers, F. N., Silva, R. A., Lima Filho, J. L., & Pimentel, M. C. (2011). Kinetics and bioreactor studies of immobilized invertase on polyurethane rigid adhesive foam. Bioresource technology, 102(2), 513-518. [CrossRef]

- El-Shora, H. M., Elazab, N. T., Al-Anazi, A., El-Sayyad, G. S., Ibrahim, M. E., & Alfakharany, M. W. (2025). Fungal tyrosinase immobilized on chitosan, calcium alginate, and silica gel for phenol elimination and dye decolorization. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 110655. [CrossRef]

- Seetharam, G.B. and Saville, B.A. (2003). Degradation of phenol using tyrosinase immobilized on siliceous supports. Water Research. 37, 436-440. [CrossRef]

- de Mello, A. C. C., da Silva, F. P., Gripa, E., Salgado, A. M., & da Fonseca, F. V. (2023). Phenol Removal from Wastewater Using Tyrosinase Enzyme Immobilized in Granular Activated Carbon and Activated Chitosan Beads. Water, 15(21), 3778.

- Gandía-Herrero, F., Jiménez-Atiénzar, M., Cabanes, J., Garcia-Carmona, F. and Escribano, J. (2005). Evidence for a common regulation in the activation of a polyphenol oxidase by trypsin and sodium dodecyl sulfate. Biol. Chem. 386, 601-607. [CrossRef]

- Gianfreda, L., Sannino, F., Rao, M.A. and Bollag, J-M. (2003). Oxidative transformation of phenols in aqueous mixtures. Water Research. 37, 3205-3215. [CrossRef]

- Shao, J., Ling-Ling, H. and Yu-Min, Y. (2008). Immobilization of polyphenol oxidase on alginate- SiO2 hybrid gel: stability and preliminary applications in the removal of aqueous phenol. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 10, 2086-2089.

- Karam, J. and Nicell, J.A. (1997). Potential Applications of Enzymes in Waste Treatment. J. Chem. Tech. Biotechnol. 69, 141-153. [CrossRef]

- Faria, R.O., Moure?, V.R. and Mitchell, D.A. (2007). The biotechnological Potential of Mushroom Tyrosinases. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 45, 287-294.

- Steffens, J.C., Harel, E., Hunt, M.D. and Thipyapong, P. (1998). Polyphenol oxidase. In Polyphenols 96. Editors: J. Vercauteren, C. Chèze, J. Triaud. Editions. INRA, Paris (Les Colloques, n°87), pp. 223-250.

- Jolivet, S., Arpin, N., Wichers, H.J. and Pellon, G. (1998). Agaricus bisporus browning: a review. Mycol. Res. 102, No., 12, 1459-1483. [CrossRef]

- Burton, S.G. (1994). Biocatalysis with polyphenol oxidase: a review. Catalysis Today. 22, 459-487. [CrossRef]

- Fenoll, L.G., Rodriguez-Lopez, J.N., Garcia-Molina, F., Garcia-Canivas, F. and Tudela, J. (2002). Michaelis constants of mushroom tyrosinase with respect to oxygen in the presence of monophenols and diphenols . The international Journal of Biochemistry and Cell biology. 34, 332-336. [CrossRef]

- Orenes-Pinero, E., Garcia-Carmona, F. and Sanchez-Ferrer, A. (2006). Kinetic characterization of activity of Strptomyces antibiocus tyrosinase. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 39, 158- 163.

- Ndlovu, T., Ba, S., & Malinga, S. P. (2020). Overview of recent advances in immobilisation techniques for phenol oxidases in solution. Catalysts, 10(5), 467. [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y., Yang, G., Li, Y., Xu, L., Chen, X., Song, H., & Zhao, C. X. (2023). Alginate-based materials for enzyme encapsulation. Advances in colloid and interface science, 318, 102957. [CrossRef]

- Gouzi, H. and Benmansour, A. (2007). Partial purification and characterization of polyphenol oxidase extracted from Agaricus bisporus (J.E.Lange) Imbach. International journal of chemical reactor engineering. 5, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Munjal, N. and Sawhney, S.K. (2002). Stability and properties of mushroom tyrosinase entrapped in alginate, polyacrylamide and gelatine gels. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 30, 613-619. [CrossRef]

- David, A.E., Wang, N.S., Yang, V.C., Yang, A.J., (2006). Chemically surface modified gel (CSMG): an excellent enzyme-immobilization matrix for industrial processes. J. Biotechnol. 125, 395–407. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. and Flurkey, W.H. (2004). Purification and characterization of tyrosinase from gill tissue of Portabella mushrooms. Phytochemistry. 65, 671-678. [CrossRef]

- Lineweaver, H. and Burk, D. (1934). The Determination of Enzyme Dissociation Constants. 56, 658-666. [CrossRef]

- Gouzi, H., Depagne, C., & Coradin, T. (2012). Kinetics and thermodynamics of the thermal inactivation of polyphenol oxidase in an aqueous extract from Agaricus bisporus. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 60(1), 500-506. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Kjonaas, R. and Flurkey, W.H. (1999). Does N-hydroxyglycine inhibit plant and fungal laccases?. Phytochemistry. 52, 775-783. [CrossRef]

- Yahşi, A., Şahin, F., Demirel, G., & Tümtürk, H. (2005). Binary immobilization of tyrosinase by using alginate gel beads and poly (acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) hydrogels. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 36(4), 253-258. [CrossRef]

- Keerti, Gupta, A., Kumar, V., Dubey, A., & Verma, A. K. (2014). Kinetic characterization and effect of immobilized thermostable β-glucosidase in alginate gel beads on sugarcane juice. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2014(1), 178498.

- Malhotra, I., & Basir, S. F. (2020). Immobilization of invertase in calcium alginate and calcium alginate-kappa-carrageenan beads and its application in bioethanol production. Preparative biochemistry & biotechnology, 50(5), 494-503. [CrossRef]

- Wahab, W. A. A., Karam, E. A., Hassan, M. E., Kansoh, A. L., Esawy, M. A., & Awad, G. E. (2018). Optimization of pectinase immobilization on grafted alginate-agar gel beads by 24 full factorial CCD and thermodynamic profiling for evaluating of operational covalent immobilization. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 113, 159-170. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q., Xu, Z., Duan, Y., Zhu, Y., Ou, M., & Xu, X. (2017). Immobilization of tyrosinase on polyacrylonitrile beads: biodegradation of phenol from aqueous solution and the relevant cytotoxicity assessment. RSC Advances, 7(45), 28114-28123. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N., Singh, R., Kaur, K. and Singh, H. (1999). Studies of the physico-chemical properties and polyphenoloxidase activity in seeds from hybrid sunflower (Helianthus annuus) varieties grown in India. Food Chemistry. 66, 241-247. [CrossRef]

- Won, K., Kim, S., Kim, K.J., Park, H.W. and. Moon, S.J. (2005). Optimisation of lipase entrapment in Ca-alginate gel beads. Process Biochemistry. 40, 2149-2154. [CrossRef]

- Dey, G., Singh, B. and. Banerjee, R. (2003). Immobilization of α-Amylase Product by Bacillus circulans GRS 313. Brazilian Archives Of Biology and Techology. 46(2), 157-176.

- Ahmed, S. A. (2008). Invertase production by Bacillus macerans immobilized on calcium alginate beads. J Appl Sci Res, 4(12), 1777-1781.

- Berset, C. (1993). Enzymes immobilisées. In Biotechnologie, coordonnateur : Scriban, R, Paris, France (4ème ed., pp. 365-392). Tec et Doc-Lavoisier.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).