Submitted:

24 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

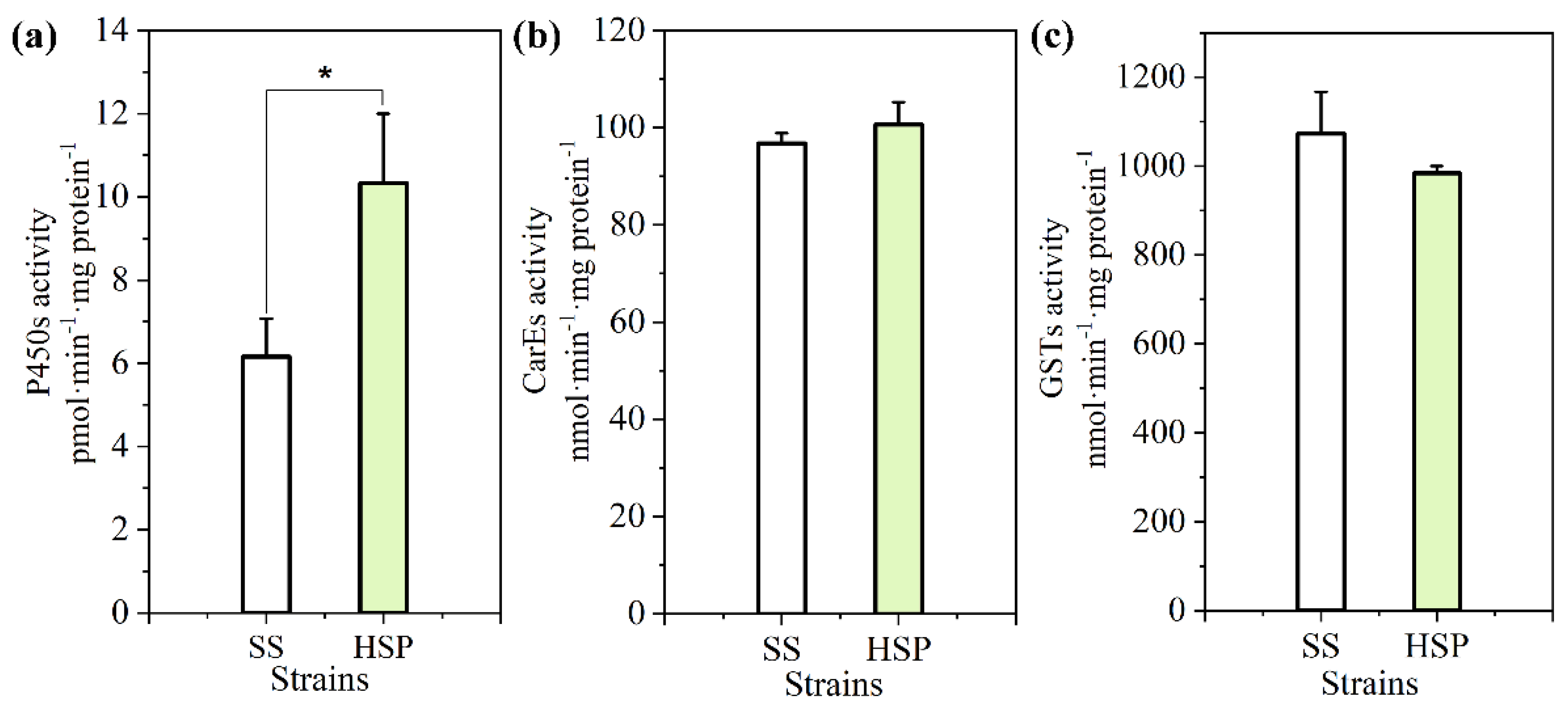

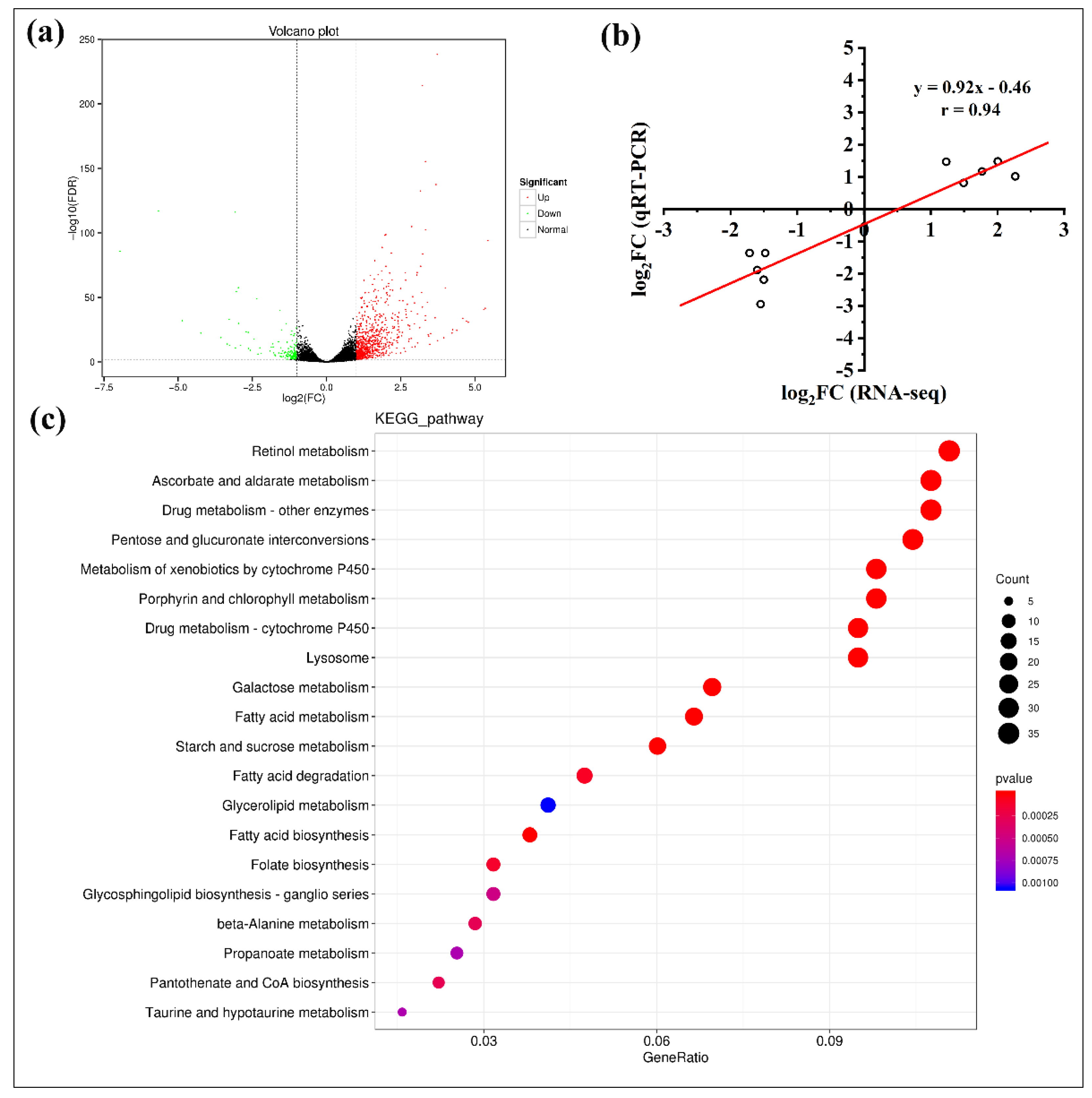

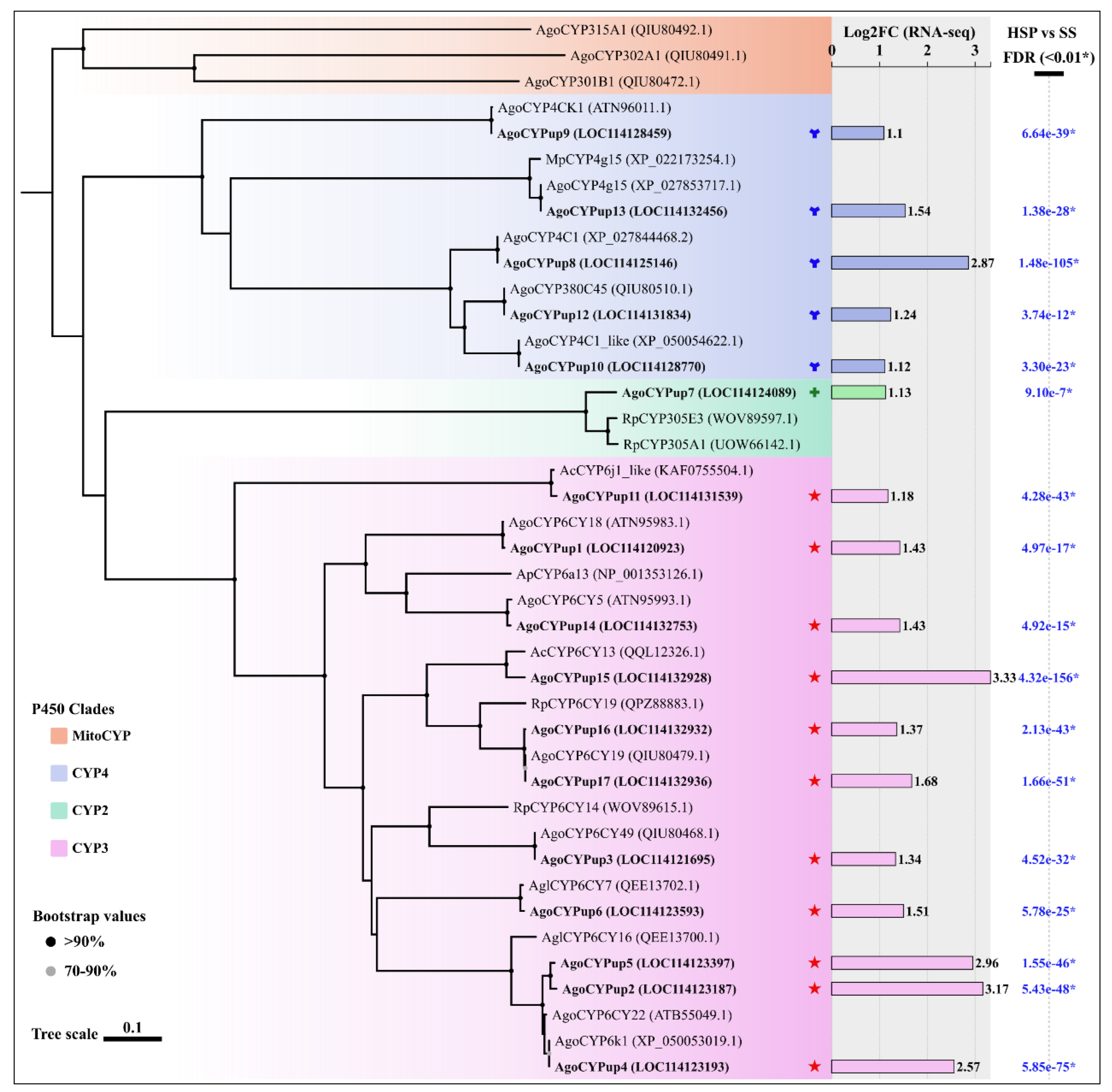

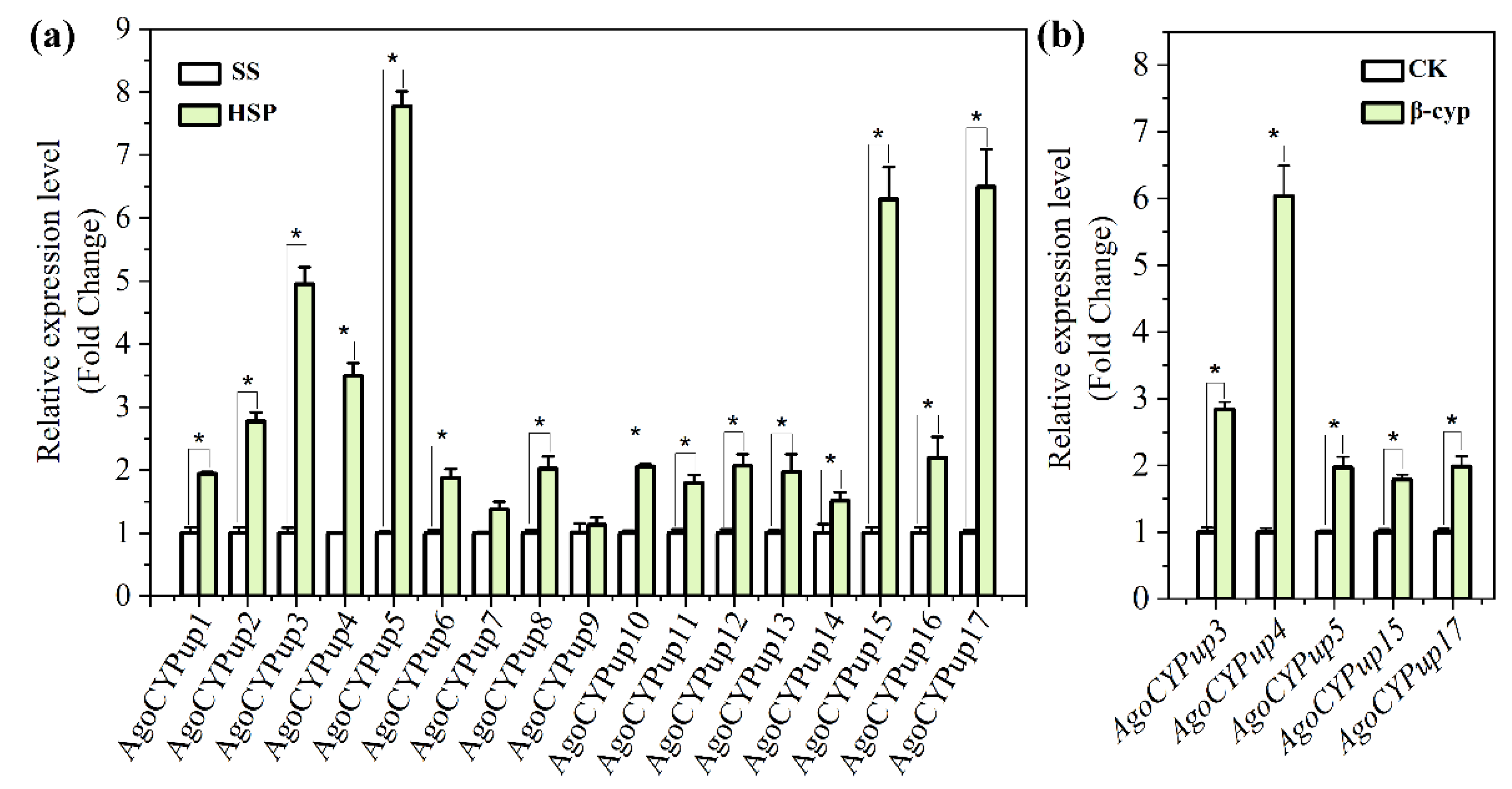

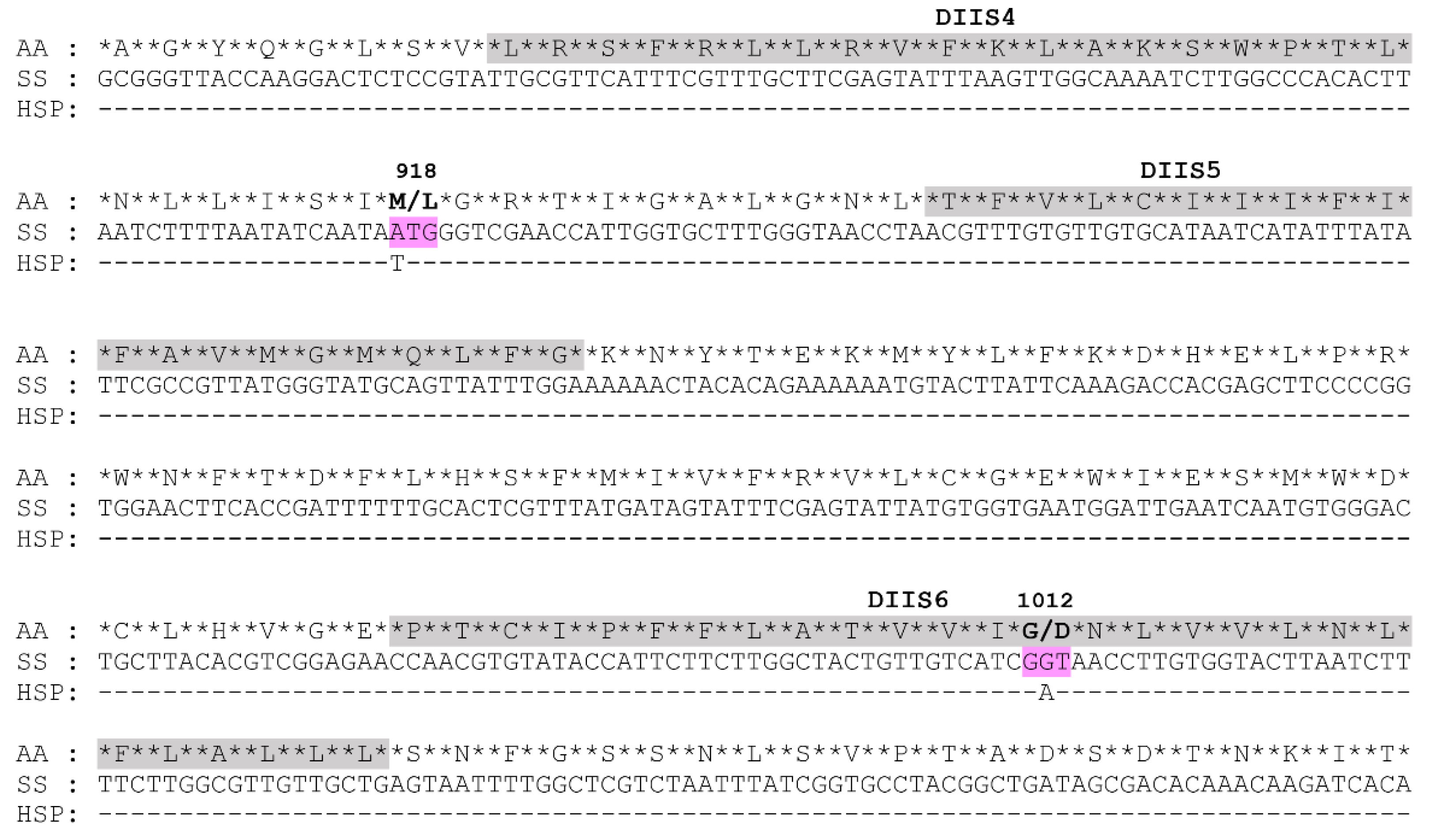

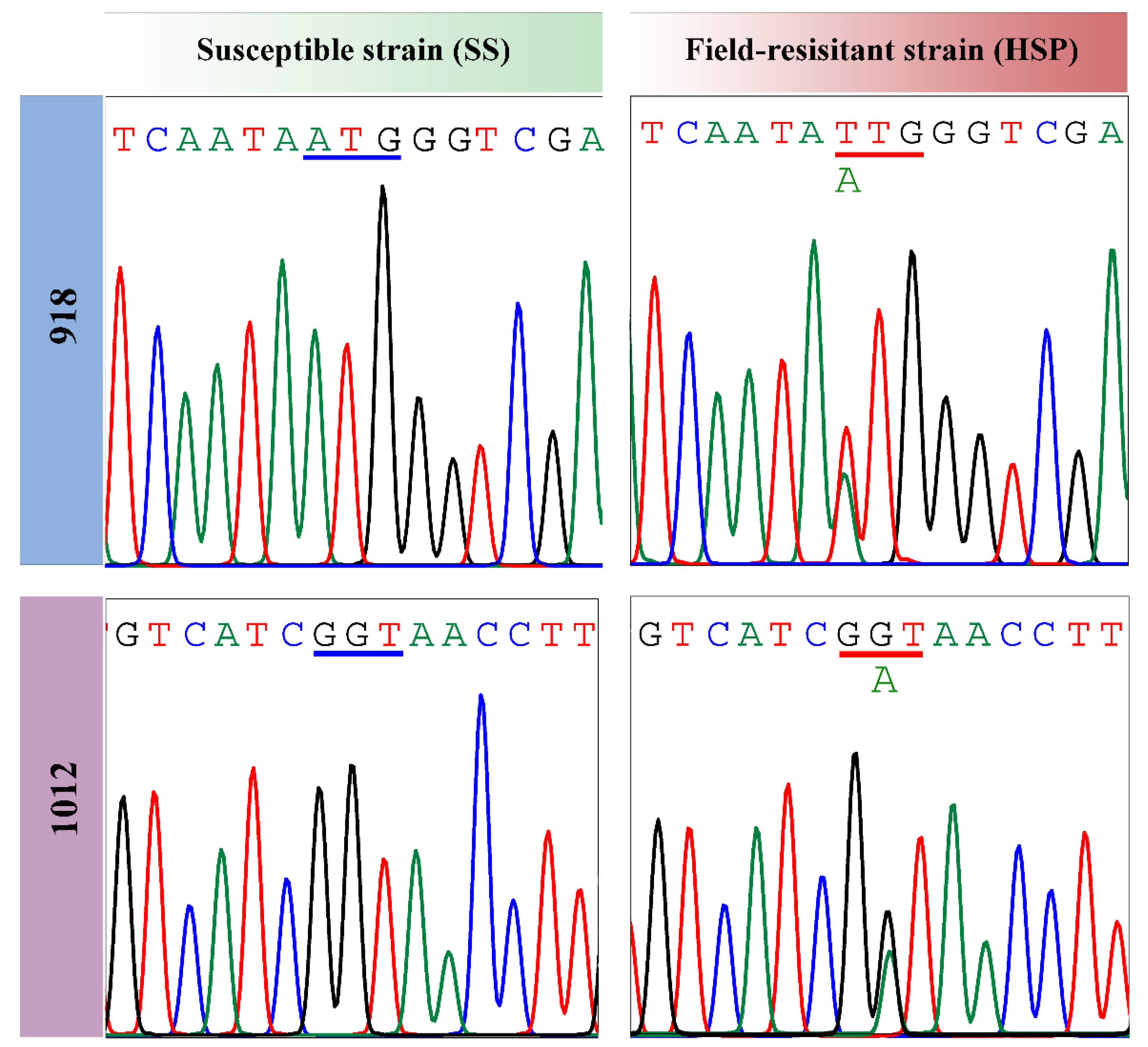

Chinese wolfberry (Lycium barbarum L.), a specialty crop of ecological, medical and economic values in Ningxia province of China, is subjected to severe Aphis gossypii Glover damage. Currently, A. gossypii populations showing extremely high-level resistance to beta-cypermethrinin in the major wolfberry planting areas in Ningxia. The specific resistance mechanisms, however, are still not known. In this work, we collected a field A. gossypii strain (HSP) from a wolfberry orchard of Ningxia in 2021 using a single-time sampling method and its resistance to beta-cypermethrin was determined to be extremely high (994.74‒fold) as compared with a susceptible strain (SS). Then we explored the potential resistance mechanisms from two aspects of metabolic detoxification and target-site alterations. Bioassay of beta-cypermethrin with or without the synergist showed that piperonyl butoxide (PBO) significantly increased the toxicity of beta-cypermethrin (4.72‒fold) to the HSP strain while triphenyl phosphate (TPP) and diethyl maleate (DEM) exhibited no significant synergistic effects. Correspondingly, the O-demethylase activity of the cytochrome P450s in the HSP strain was 1.68‒fold higher than that in the susceptive strain (SS), whereas changes of carboxylesterases and glutathione S-transferases in their activities were unremarkable. Also, fifteen upregulated P450 genes were identified by both RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR technologies, containing eleven CYP6 genes, three CYP4 genes and one CYP380 gene. Especially, five CYP6 genes of high relative expression levels (> 3.00‒fold) were intensively expressed by the beta-cypermethrin induction in the HSP aphids. These metabolism-related results indicate the key role of the P450-mediated metabolic detoxification in the HSP resistance to beta-cypermethrin. Sequencing of voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) genes identified a prevalent M918L mutation and a new G1012D mutation in the HSP A. gossypii. Moreover, heterozygous 918M/L and 918M/L+G1012D mutations were the dominant genotypes with frequencies of 60.00% and 36.67% in the HSP population, respectively. Overall, VGSC mutations along with P450-mediated metabolic resistance were contributed to the extremely high resistance of the HSP wolfberry aphids to beta-cypermethrin, providing support for A. gossypii control and resistance management in the wolfberry planting areas of Ningxia using insecticides with different modes of action.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Insects

2.3. Bioassays

2.4. Synergistic Bioassays

2.5. Enzyme Activity Analysis

2.6. Transcriptome Sequencing and Analysis

2.7. Reverse Transcriptase Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

2.8. VGSC Mutations Analysis in A. gossypii

2.9. Determination of VGSC Mutation Frequencies in A. gossypii

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Resistance of the HSP A. gossypii To Beta-Cypermethrin

3.2. Effect of Synergists on A. gossypii Resistance to Beta-Cypermethrin

3.3. Detoxification Enzyme Activities

3.4. Comparative Transcriptomics of the SS and HSP Strains

3.5. Cytochrome P450 DEGs and phylogenetic Analysis

3.6. Relative Expression Levels of the Cytochrome P450 DEGs

3.7. Target-Site Mutations and Frequencies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, X.; Wang, J.; Robinson, B. H.; Zhao, X. Water-use patterns of Chinese wolfberry (Lycium barbarum L.) on the Tibetan Plateau. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 255, 107010.

- Qi, J.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, N.; Chen, X.; Jiang, T.; Xu, H.; Lei, H. Insights into the improvement of bioactive phytochemicals, antioxidant activities and flavor profiles in Chinese wolfberry juice by select lactic acid bacteria. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101264.

- Lu, W.; Jiang, Q.; Shi, H.; Niu, Y.; Gao, B.; Yu, L. Partial least-squares-discriminant analysis differentiating Chinese wolfberries by UPLC–MS and Flow Injection Mass Spectrometric (FIMS) fingerprints. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 9073-9080.

- Tian, Y.; Xia, T.; Qiang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, M. Nutrition, bioactive components, and hepatoprotective activity of fruit vinegar produced from Ningxia wolfberry. Molecules 2022, 27, 4422.

- Chen, X.; Wan, W.; Feng, S.; Xu, S.; Yang, J.; Duan, L. Biological activities of four components of essential oils against the wolfberry aphid (Aphis gossypii). Acta Entomol. Sin. 2019, 62, 453-460.

- Yan, L.; Guo, R.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Wei, Q.; Han, Y.; Liu, M.; Ma, X. Morphology and bionomics of Aphis gossypii (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on Chinese wolfberry (Lycium barbarum). Acta Entomol. Sin. 2017, 60, 666-680.

- Chen, X.; Tie, M.; Chen, A.; Ma, K.; Li, F.; Liang, P.; Liu, Y.; Song, D.; Gao, X. Pyrethroid resistance associated with M918 L mutation and detoxifying metabolism in Aphis gossypii from Bt cotton growing regions of China. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 2353-2359.

- Peng, T.; Pan, Y.; Yang, C.; Gao, X.; Xi, J.; Wu, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhu, E.; Xin, X.; Zhan, C.; Shang, Q. Over-expression of CYP6A2 is associated with spirotetramat resistance and cross-resistance in the resistant strain of Aphis gossypii Glover. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 126, 64-69.

- Li, R.; Cheng, S.; Chen, Z.; Guo, T.; Liang, P.; Zhen, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liang, P.; Gao, X. Establishment of toxicity and susceptibility baseline of broflanilide for Aphis gossypii Glove. Insects 2022, 13, 1033.

- Wang, F.; Liu, C.; He, J.; Tian, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R. Resistance of wolfberry aphid in Ningxia. J. Northwest A&F Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 45, 61-67.

- Chen, X.; Xia, J.; Shang, Q.; Song, D.; Gao, X. UDP-glucosyltransferases potentially contribute to imidacloprid resistance in Aphis gossypii glover based on transcriptomic and proteomic analyses. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 159, 98-106.

- Chen, X.; Tang, C.; Ma, K.; Xia, J.; Song, D.; Gao, X. Overexpression of UDP-glycosyltransferase potentially involved in insecticide resistance in Aphis gossypii Glover collected from Bt cotton fields in China. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 1371-1377.

- Valmorbida, I.; Coates, B. S.; Hodgson, E. W.; Ryan, M.; O’Neal, M. E., Evidence of enhanced reproductive performance and lack-of-fitness costs among soybean aphids, Aphis glycines, with varying levels of pyrethroid resistance. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 2000-2010.

- Dong, K.; Du, Y.; Rinkevich, F.; Nomura, Y.; Xu, P.; Wang, L.; Silver, K.; Zhorov, B. S. Molecular biology of insect sodium channels and pyrethroid resistance. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 50, 1-17.

- Wang, K.; You, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xian, W.; Song, Y.; Ge, Y.; Lu, X.; Ma, Z. Widespread resistance of the apple aphid Aphis spiraecola to pyrethroids in China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 208, 106289.

- Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, H.; Wan, Q.; Pan, B. Transcription profiling and characterization of Dermanyssus gallinae cytochrome P450 genes involved in beta-cypermethrin resistance. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 283, 109155.

- Wang, X.; Xiang, X.; Yu, H.; Liu, S.; Yin, Y.; Cui, P.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Jiang, C.; Yang, Q. Monitoring and biochemical characterization of beta-cypermethrin resistance in Spodoptera exigua (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Sichuan province, China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 146, 71-79.

- Xi, J.; Pan, Y.; Bi, R.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Peng, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Hu, X.; Shang, Q. Elevated expression of esterase and cytochrome P450 are related with lambda–cyhalothrin resistance and lead to cross resistance in Aphis glycines Matsumura. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 118, 77-81.

- Ye, M.; Nayak, B.; Xiong, L.; Xie, C.; Dong, Y.; You, M.; Yuchi, Z.; You, S. The role of insect cytochrome P450s in mediating insecticide resistance. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1-18.

- Li, R.; Sun, X.; Liang, P.; Gao, X. Characterization of carboxylesterase PxαE8 and its role in multi-insecticide resistance in Plutella xylostella (L.). J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 1713-1721.

- Li, R.; Zhu, B.; Shan, J.; Li, L.; Liang, P.; Gao, X. Functional analysis of a carboxylesterase gene involved in beta-cypermethrin and phoxim resistance in Plutella xylostella (L.). Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 2097-2105.

- Zhang, L.; Shi, J.; Shi, X.; Liang, P.; Gao, J.; Gao, X. Quantitative and qualitative changes of the carboxylesterase associated with beta-cypermethrin resistance in the housefly, Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae). Comp. Biochem. Phys. B 2010, 156, 6-11.

- Gao, S.; Tan, Y.; Han, H.; Guo, N.; Gao, H.; Xu, L.; Lin, K. Resistance to beta-cypermethrin, azadirachtin, and matrine, and biochemical characterization of field populations of Oedaleus asiaticus (Bey-Bienko) in Inner Mongolia, northern China. J. Insect Sci. 2022, 22, 1.

- Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, H.; Wan, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Pan, B. Susceptibility of Dermanyssus gallinae from China to acaricides and functional analysis of glutathione S-transferases associated with beta-cypermethrin resistance. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 171, 104724.

- Pavlidi, N.; Vontas, J.; Van Leeuwen, T. The role of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) in insecticide resistance in crop pests and disease vectors. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 27, 97-102.

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Shi, C.; Zhu, X. Transcriptome-based identification and characterization of genes associated with resistance to beta-cypermethrin in Rhopalosiphum padi (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Agriculture 2023, 13, 235.

- Carletto, J.; Martin, T.; Vanlerberghe-Masutti, F.; Brévault, T. Insecticide resistance traits differ among and within host races in Aphis gossypii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2010, 66, 301-307.

- Scott, J. G. Life and death at the voltage-sensitive sodium channel: Evolution in response to insecticide use. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2019, 64, 243-257.

- Cominelli, F.; Chiesa, O.; Panini, M.; Massimino Cocuzza, G. E.; Mazzoni, E. Survey of target site mutations linked with insecticide resistance in Italian populations of Aphis gossypii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 4361-4370.

- Bass, C.; Nauen, R. The molecular mechanisms of insecticide resistance in aphid crop pests. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 156, 103937.

- Sun, L.; Gao, X.; Zheng, B. Cloning of partial sodium channel gene from strains of fenvalerate-resistant and susceptible cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii Glover). Agric. Sci. China 2003, 36, 1301-1305.

- Rinkevich, F. D.; Du, Y.; Dong, K. Diversity and convergence of sodium channel mutations involved in resistance to pyrethroids. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2013, 106, 93-100.

- Chen, A.; Zhang, H.; Shan, T.; Shi, X.; Gao, X. The overexpression of three cytochrome P450 genes CYP6CY14, CYP6CY22 and CYP6UN1 contributed to metabolic resistance to dinotefuran in melon/cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 167, 104601.

- Chen, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Xia, X. J. J. o. P. S. The cross-resistance patterns and biochemical characteristics of an imidacloprid-resistant strain of the cotton aphid. J. Pestic. Sci. 2015, 40, 55-59.

- Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248-254.

- Quan, Q.; Hu, X.; Pan, B.; Zeng, B.; Wu, N.; Fang, G.; Cao, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhan, S. Draft genome of the cotton aphid Aphis gossypii. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 105, 25-32.

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357-360.

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G. M.; Antonescu, C. M.; Chang, T.-C.; Mendell, J. T.; Salzberg, S. L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290-295.

- Peng, T.; Pan, Y.; Tian, F.; Xu, H.; Yang, F.; Chen, X.; Gao, X.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Shang, Q. Identification and the potential roles of long non-coding RNAs in regulating acetyl-CoA carboxylase ACC transcription in spirotetramat-resistant Aphis gossypii. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 179, 104972.

- Jin, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, K.; Dong, H. Detoxification enzymes associated with butene-fipronil resistance in Epacromius coerulipes. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 227-235.

- Zhao, L.; Wang, C.; Gao, X.; Luo, J.; Zhu, X.; Wan, S. Characterization of P450 monooxygenase gene family in the cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover. J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 2022, 25, 101861.

- Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Cui, L.; Wang, Q.; Huang, W.; Ji, X.; Yang, Q.; Rui, C. Overexpression of ATP-binding cassette transporters associated with sulfoxaflor resistance in Aphis gossypii glover. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 4064-4072.

- WHO, Status of resistance in houseflies, Musca domestica, document VBC/EC/ 80.7. World Health Organization 1980, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Mollah, M. M. I.; Khatun, S. Exploring selected bioinsecticides for management of cotton aphids (Aphis gossypii Glover) of brinjal in Bangladesh. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101289.

- Qu, Y.; Ullah, F.; Luo, C.; Monticelli, L. S.; Lavoir, A.-V.; Gao, X.; Song, D.; Desneux, N. Sublethal effects of beta-cypermethrin modulate interspecific interactions between specialist and generalist aphid species on soybean. Ecotoxicol Environ. Saf. 2020, 206, 111302.

- Mollah, M. M. I.; Rahman, M. M.; Miah, M. A.; Mala, M.; Hassan. M. Z. Efficacy of insecticides on the incidence and infestation of lablab bean aphid (Aphis craccivora Koch) under field conditions. J. Patuakhali Sci. Techn. Univ. 2013, 4, 53-59.

- Wang, K.; Zhao, J.; Han, Z.; Chen, M. Comparative transcriptome and RNA interference reveal CYP6DC1 and CYP380C47 related to lambda-cyhalothrin resistance in Rhopalosiphum padi. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 183, 105088.

- Zeng, X.; Pan, Y.; Song, J.; Li, J.; Lv, Y.; Gao, X.; Tian, F.; Peng, T.; Xu, H.; Shang, Q. Resistance risk assessment of the ryanoid anthranilic diamide insecticide cyantraniliprole in Aphis gossypii Glover. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 5849-5857.

- Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Dong, W.; Gu, Z.; Wang, C.; Chen, A.; Shi, X.; Gao, X. Mutations in the nAChR β1 subunit and overexpression of P450 genes are associated with high resistance to thiamethoxam in melon aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover. Comp. Biochem. Phys. B 2022, 258, 110682.

- Everaert, C.; Luypaert, M.; Maag, J. L. V.; Cheng, Q. X.; Dinger, M. E.; Hellemans, J.; Mestdagh, P. Benchmarking of RNA-sequencing analysis workflows using whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR expression data. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1559.

- Teng, M.; Love, M; Davis, C; Djebali, S.; Dobin, A.; Graveley, B; Li, S.; Mason, C.; Olson, S.; Pervouchine, D.; Sloan, C.; Wei, X.; Zhan, L.; Irizarry, R. A benchmark for RNA-seq quantification pipelines. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 74.

- Munkhbayar, O.; Liu, N.; Li, M.; Qiu, X. First report of voltage-gated sodium channel M918V and molecular diagnostics of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor R81T in the cotton aphid. J. Appl. Entomol. 2021, 145, 261-269.

- Burton, M. J.; Mellor, I. R.; Duce, I. R.; Davies, T. G. E.; Field, L. M.; Williamson, M. S. Differential resistance of insect sodium channels with kdr mutations to deltamethrin, permethrin and DDT. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 41, 723-732.

- Vais, H.; Atkinson, S.; Eldursi, N.; Devonshire, A. L.; Williamson, M. S.; Usherwood, P. N. R. A single amino acid change makes a rat neuronal sodium channel highly sensitive to pyrethroid insecticides. FEBS Lett. 2000, 470, 135-138.

- Hyeock Lee, S.; Smith, T.; C. Knipple, D.; Soderlund, D. Mutations in the house fly Vssc1 sodium channel gene associated with super-kdr resistance abolish the pyrethroid sensitivity of Vssc1/tipE sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999, 29, 185-194.

| Strain | Insecticide/synergist1 | Slope ± SE | LC50 (μg·mL‒1) (95% CL) |

Chi-square | RR2/SR3 |

| SS | beta-cypermethrin | 1.11 ± 0.12 | 2.33 (1.54–3.18)*4 | 0.42 | — |

| HSP | beta-cypermethrin | 2.02 ± 0.16 | 2317.74 (2025.90–2644.88) | 5.30 | 994.74 |

| beta-cypermethrin + PBO | 1.74 ± 0.18 | 491.23 (363.19 ‒ 611.38)* | 2.26 | 4.72 | |

| beta-cypermethrin + TPP | 2.04 ± 0.19 | 2169.48 (1864.02 ‒ 2533.14) | 4.85 | 1.07 | |

| beta-cypermethrin + DEM | 1.63 ± 0.16 | 2441.71 (2044.55 ‒ 2919.19) | 3.00 | 0.95 |

| Genotype of VGSC | Genotype frequency(%)5 | |

| 918 | 1012 | |

| M/M1 | G/G3 | 3.33 |

| G/D4 | 0.00 | |

| D/D | 0.00 | |

| M/L2 | G/G | 60.00 |

| G/D | 36.67 | |

| D/D | 0.00 | |

| L/L | G/G | 0.00 |

| G/D | 0.00 | |

| D/D | 0.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).