1. Introduction

Long Gamma-Ray Bursts

Long Gamma Ray Bursts (GRBs) are the most powerful electro-magnetic explosions known in the Universe. They consist in intense emissions of gamma and hard X-rays typically lasting from 2 s up to several 103 seconds (the “prompt emission”) followed by a longer decay phase (the “afterglow”) that usually is observable in X, optical, IR and radio, lasting for weeks or months.

Gamma-Ray Bursts (GRBs) are usually divided in “short” GRBs (lasting <2 s in the observer frame), arising from binary NSt mergers and from giant magnetar flares, and “long” GRBs (>2 s), supposed to be produced by narrowly collimated-jet-emitting collapsing Wolf-Rayet stars (collapsars) seen head-on. This categorization was first proposed by Kouveliotou et al. (1993).

We shall henceforth quote energy levels in units of Fifty-One-Erg (foe) defined as 1 foe=1051 erg, equivalent to the canonical SN-1a energy. Long GRBs typically release (isotropic equivalent) electromagnetic energy budgets of 1 to 4,000 foe and more (1051 to 1055 erg) in the progenitor rest frame.

In

Section 2, we shall argue that the most widely accepted model for explaining long GRBs, namely the “collapsar model”, has failed many critical experimental tests and theoretical criteria and that it should therefore be discarded. We argue furthermore that most available evidence hints at long GRBs as being isotropic explosions. The shall engage in the daunting task of identifying a physical process able to generate up to 10

55 erg of energy in 10

1 to 10

3 seconds.

In

Section 3, we introduce such a new isotropic model for long GRBs, the “teranova model”, named according to peak luminosity nova-kilonova, etc… convention. According to this new theory, long GRBs are tremendously energetic *isotropic* detonations (teranovae) powered by unbinding neutron stars. We cautiously develop a possible, albeit very rare, scenario leading a NSt to unbind, namely a collision between a high-speed magnetar and a supergiant star.

In

Section 4, we confront the teranova theory with observational data. We show that the new model seems to elegantly solve most of the problems that are plaguing the jetted collapsar model.

2. Difficulties Of The Collapsar Model

The failures of the predominant collapsar model

The main (experimental and theoretical) failures of the collapsar model of long GRBs: the clearly non-periodic pattern of the light curves (suggesting that they do not arise from highly anisotropic, rotating sources), the absence of any clear-cut observation of jetted collapsars from the side, even after several years of intense monitoring, the lack of any realistic mechanisms for creating the SN-1c progenitors, the lack of good physical reason why only supernovae of type 1c should be associated with bursts, the absence of any associated SNe in cases when they should have been detectable, the (radio-imaged) spherical afterglows expanding at relativistic speeds, the unexplained extreme energy levels, the totally unexplainably duration of the longest bursts (ultra-long GRBs), the observed blueshifts of some associated SNe, the significant proton contribution to synchrotron radiation, the existence of multiple precursors and, last but not least, the internal collapsar model theoretical inconsistencies.

Some of the collapsar model experimental failures (the TeV photons showers experienced in some very powerful long bursts and the kilonova emissions detected in some nearby long bursts) shall be dealt with in a following paper.

We conclude that new ideas are now needed to develop a new, more satisfactory model.

Non-periodical light curves

The most serious and obvious problem of the collapsar model is the absence of any periodicity in the time-resolved (bolometric or energy-specific) light curves. This is especially disturbing since long GRB prompt emissions typically last 10(1 to 3) sec, looking only at their t90 (the time interval during which 90% of the energy is received), while their emitting sources are supposed to rotate tens to hundreds of times per second.

That is, the prompt phase light curves extend over many progenitor periods, as newly born neutron stars left over from supernovae explosions are known to rotate with spin rates of 10 to 100 Hz (see e.g. Ott et al. 2006). During the collapse, the collapsar should quickly reach spinning rates that would translate into detectable light curve periodicity.

Some authors have in fact found oscillatory features in some burst light curves, but only of small amplitudes, hinting at ancillary pulsations or eclipsing phenomena, rather than entire source rotation (Hou et al. 2014).

This non-periodicity does not proceed from a limitation of the detectors since for example the Fermi observatory tags individual arriving photons with 2 microseconds precision in its full 128 spectral channels (Lesage et al. 2023).

Blazars offer perhaps the best counter-example. In the cosmic zoo, blazars are the closest thing that exist to a jetted collapsar pointing at us. As it turns out, blazars have been found to display some light curve periodicity, obviously with much longer periods, expressed in hundreds of days (see e.g. Bhatta (2019).

By visual inspection, long GRB light curves really do not suggest highly anisotropic, fast rotating sources, but rather a roughly isotropic (and chaotic) phenomenon, a SN-like explosion, albeit more powerful.

Quasi-absence of off-axis collapsars

Even after trying for dozens of years, astronomers have never detected with a satisfactory level of confidence any jet-emitting collapsar seen from the side. Not a single direct visual case and only a handful of indirect, tentative, unconfirmed cases. Whereas the collapsar model predicts that hundreds of off-axis collapsar should occur every day, since those should be a thousand times more frequent than head-on collapsars (i.e. detected long GRBs), which happens once every second day on average Universe-wide. Heuristic arguments suggest that, even if considering only distances z<0.1 (d< 400 Mpc), we should observe 1 off-axis collapsar every 10 to 30 days.

Many teams have expressed hopes of having serendipitously identified one off-axis long GRB, based on different indirect indices, like similarities with typical X-ray light curves of LGRBs or with typical associated SN light curves (see e.g. Butler et al. (2005), Huang et al. (2004), Mazzali et al. (2005), Krühler et al. (2009), Ramirez-Ruiz et al. (2005), Dado & Dar (2018 B), Izzo et al. (2020). However, in all cases the evidence has remained peacemeal and inconclusive.

Systematic searches for off-axis jetted collapsars were undertaken as well, relying on indirect evidence, but mostly without success (see e.g. Corsi et al. 2016 and Taddia et al. 2019). Recently, a sample of 14 GRB-lacking SNe of type 1c-BL, found in galaxies typical for long GRBs, was investigated with the VLA radio telescopes, with just one possible positive result − that was however compatible with other explanations (Schroeder et al, 2025).

The most ambitious systematic search program was the afterglow-based survey conducted at the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) at the Palomar observatory, aiming at finding LGRB-like optical afterglows with no simultaneous burst as seen from the Earth. Ho et al. (2020) and Ho et al. (2022) reported that over a four-year period, from June 2018 to August 2022, the ZTF scoring the sky every night, has discovered exactly 3 suitable transients, with redshifts spectroscopically measured between z=0.876 and z=2.9. A grand total of 3 off-axis afterglow candidates over the whole Universe up to z=2.9 during a 4 yr interval is a far cry from the 100,000 to 200,000 cases per year that would be absolutely needed if the collapsar model was to be upheld. Clearly, something is deeply wrong with our picture of the central engines powering long GRBs.

If we cannot find any off-axis long GRB, however strong we try, the most straightforward explanation for this is that there is no such thing as an off-axis burst, i.e. that long GRBs are isotropic.

No credible mechanism for creating the SN-progenitors

All SNe associated with long GRBs belong to type 1c, or sometimes 1b. From the complete absence of any H and He lines in their spectra, it is inferred that the progenitors of SN 1c were stripped of their hydrogen and helium layers before going supernova. The counter-hypothesis that He was still present in the progenitor and that the He lines were just smeared out in the spectra has been eliminated after detailed analysis by Modjaz et al. (2016).

This stripping of the core is supposed to have occurred either from the star’s own strong stellar wind or from the action of a companion star in a binary system. However, as Modjaz et al. (2016) emphasized, neither of these models does succeed in removing the whole He-layer (so that less than 0.2 M⊙ remains).

Weird exclusivity of type 1c/1b SNe

Furthermore, the collapsar model fails to explain why the associated SN should systematically belong to the 1c-BL class, and never to the more usual hydrogen & helium-showing Type II core collapse SNe.

The usual collapsar modelling assumes a stripped core (and hence relies on hydrogen free Wolf-Rayet stars), since this is needed to be in line with empirical observations, but this feature is imported and does not really come out as a natural consequence in the collapsar model.

Whereas there is a big physical difference between a stripped and an usual progenitor, and hence there should exist a solid physical reason why only SNe of type 1c (or 1b) may appear alongside long gamma-ray bursts.

Frequent absence of associated SNe

The collapsar model in its second version, the 1999 “Collapsar with Hypernova” model (Woosley & MacFadyen 1999), has become the generally accepted theory after it triumphed with the observation of GRB 030329A, the second closest long GRB observed at the time, at z=0.1685 (d=590 Mpc), that belonged to the typical cosmological long GRB class.

Observationally, however, most long GRBs come out without any associated SN. Among the 1,000 long GRBs that have been localized with high angular precision after SN1998bw, only ∼50 have been found to display an associated SN (Klose et al. 2019).

Far-away SNe are clearly most difficult to observe, due to intrinsic faintness or galaxy extinction. However, even in the relatively local Universe, up to z<0.15, Dado & Dar (2018 A) have found that just 50% of long GRBs displayed an associated SN, i.e. 5 in a sample of 10 GRBs with a known redshift z<0.15. Some nearby bursts have conspicuously lacked any SN, as emphasized by Tanga et al. (2018), who gave three examples of long bursts, namely GRB 060505, GRB 060614 and GRB 111005A (the latter at z=0.01326, at this time the second closest long GRB ever detected), showing no coincident SN even after intense search trial by MUSE and even as a radio afterglow was found.

One way to iron out this issue of the missing associated supernovae would be to reactivate the original, 1993-Failed Supernova Collapsar model (Woosley 1993). However, this solution would transform the other half of the burst sample, namely the 50% of SN-having long GRBs, into a problem.

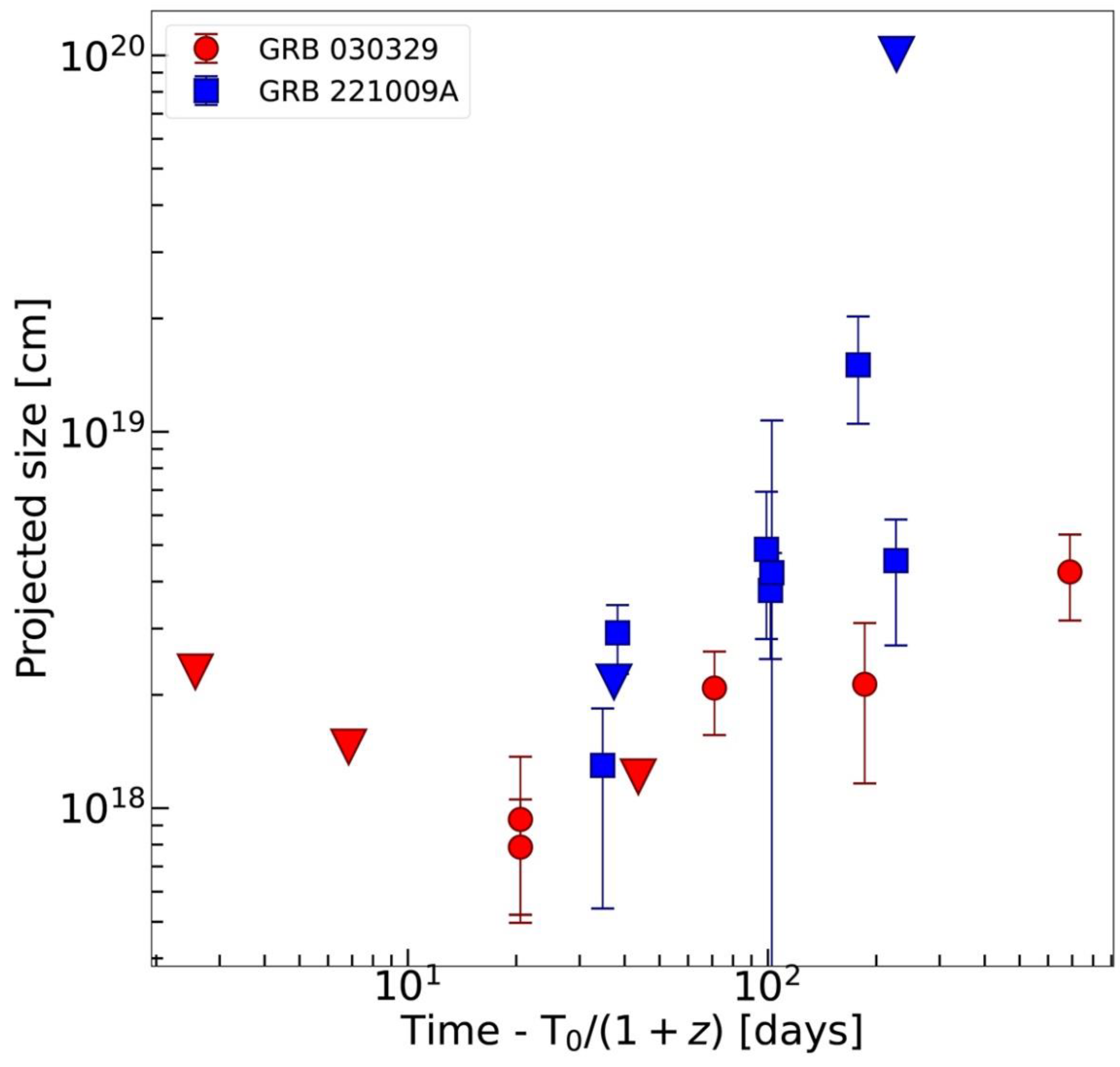

Relativistically-expanding spherical afterglows

In two lucky cases (bursts that were both powerful and nearby), namely for GRB 030329A, the historical first SN-having cosmological long burst at z=0.1685 and for GR 221009A the BOAT at z=0.1505, the afterglow scenery could be imaged directly via radio VLBI. The size and expansion speed of the emission region could be estimated and the results tended again to be very difficult to reconcile with the collapsar model (Taylor et al. 2004, Giarratana et al. 2024).

The best fit was a spherical emission zone expanding with a Lorentz factor Γ=3 to 5 for 030329A (Taylor et al. 2004), i.e. beta = 0.94-0.98, and even faster for 221009A, after correcting for relativistic geometric effects as per Rees (1966). The kinetic energy budget required for such a relativistically-expanding bubble was estimated at 300 foe. This result destroyed all the brave efforts by the collapsar model to bring down long GRB energy budgets to “reasonable” levels (i.e. not exceeding 1 foe, the canonical SN e-m budget).

Absence of neutrino detection

No clear-cut detection of neutrinos coming from GRBs was reported so far (Abbasi et al., 2022; Ai & Gao 2023). Ai & Gao (2023) showed that, in the case of the BOAT GRB 221009A, the absence of any VHE neutrino detection must lead to discard two collapsar sub-models, namely the dissipative photosphere model and the internal shock model (except if the different sub-jets had extreme bulk Lorentz factors of respectively Γ>∼400Γ and Γ>∼200). Only the “Internal-collision-induced Magnetic Reconnection and Turbulence” (ICMART) collapsar submodel remained unscathed by the neutrino non-detection.

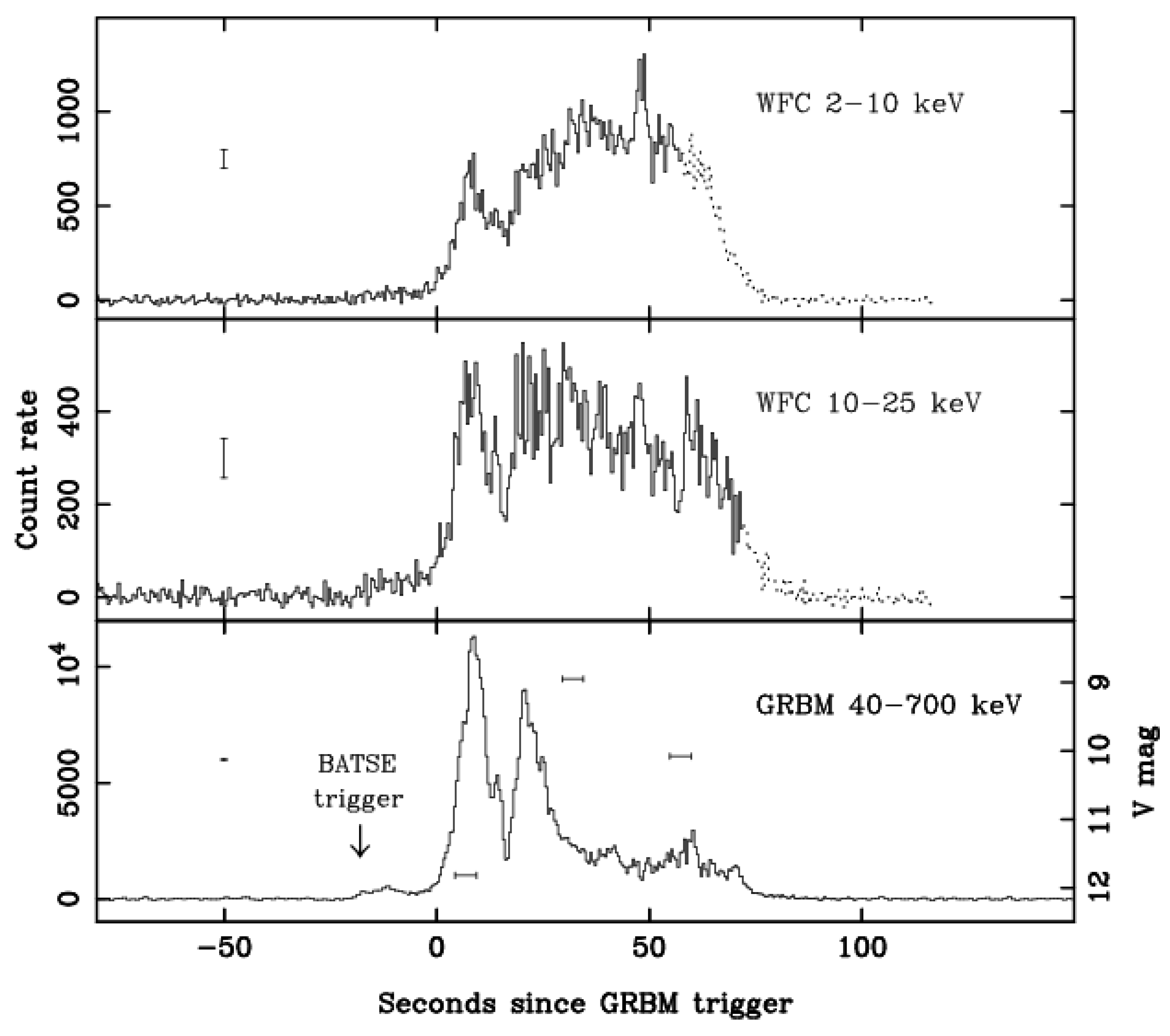

Unexplainable ultra-long GRBs

Ultra-long GRBs (ULGRBs) are generally defined as bursts exceeding 1,000 sec, though this duration sometimes includes the X-ray phase following the pure gamma-ray phase. Most authors agree that ultra-long bursts cannot be generated by fast-collapsing classical Wolf-Rayet stars, since, as pointed out by Boër, Gendre & Stratta (2015), during such ultra-long bursts, we see a continuous emission of the source for up to 6,000 sec in gamma-rays, and 20,000 sec in X-rays, both emissions showing a strong correlation, and since they display a much stronger thermal emission than usual LGRBs. All of this seems all but impossible to reconcile with the scenario of a star emitting focused jets while undergoing a very brief, millisecond-long, collapse.

Even as they represent a small minority (less than one percent) of LGRBs, these ultra-long bursts are only adding to the collapsar model woes.

Multiple precursors

Some long GRBs have been found to be preceded by one weaker energy release, in gamma and X-rays, coming several seconds to hundreds of seconds before the main gamma-ray pulse. 10% to 20% of long GRBs seem to display such precursors. We may however expect the real proportion to be higher, as it is very likely that not all precursors are captured, due to detector availability and energy thresholds and other practical limitations. Some bursts even showed two precursors, like GRB 210204A (Kumar et al. 2022).

In the collapsar model, precursors are interpreted as either (1) the first emergence of the jet outside of the stellar envelope. This first jet would be later dimmed by a “rarefaction wave” propagating backwards. Reinforced by this wave, a final, stronger relativistic jet would finally arrive (a scenario that works only for single precursors preceding the main pulse by not more than 10 sec). (2) Alternatively, the precursor may be interpreted as a tinier jet taking place during an intermediary collapse of the Wolf-Rayet Star into a neutron star, before entering into main-jet-emitting black-hole forming collapse (Wang & Mészáros 2007). The latter explanation runs into intrinsic difficulties for the bursts displaying more than two precursors.

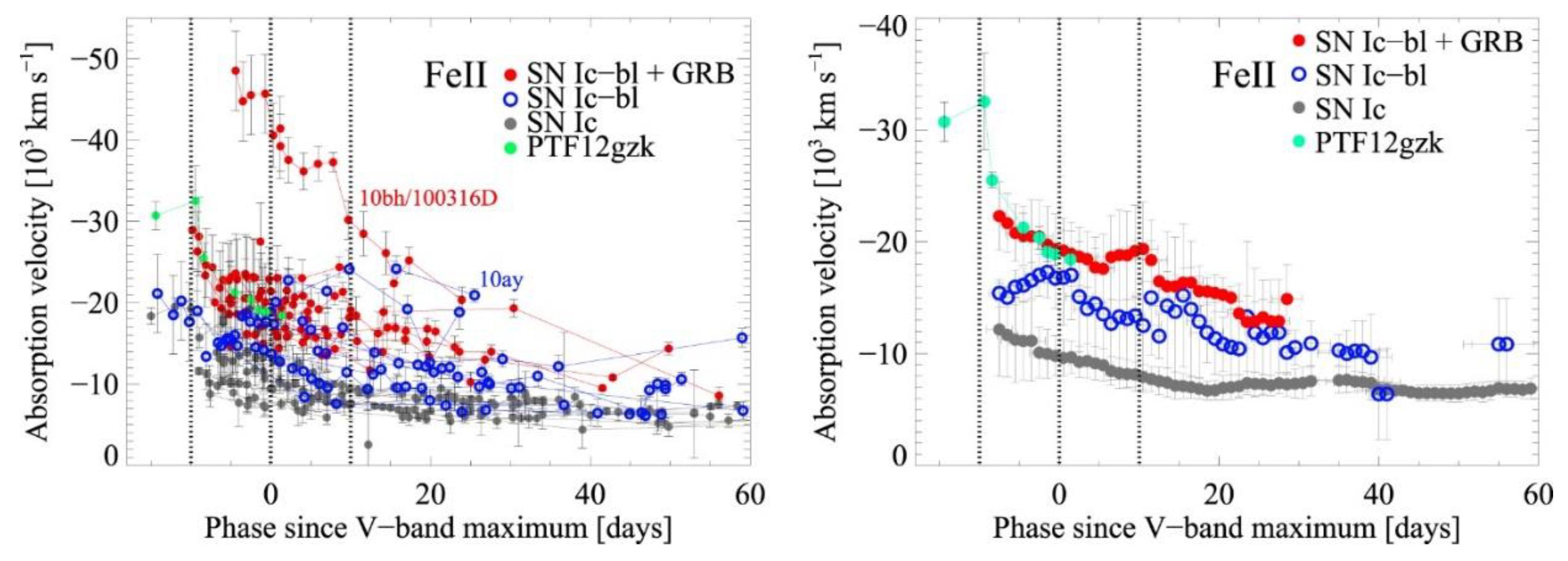

Blueshifted supernovae

Modjaz et al (2016) have identified in the spectra of GRB-associated SNe an increased photospheric expansion velocity of 5,000-10,000 km/s on average. That could be interpreted as very bright SNe or as a blueshift of the whole SN. The latter case, the most likely as we shall argue in

Section 4, may not be accounted for by the collapsar model.

Overwhelming proton contribution to observed synchrotron radiation

Ghisellini et al. (2020) have shown that the (time-integrated) spectral energy distribution (SED) of most long GRBs can be best fitted with three patched power law functions instead of two, i.e. with a Band function (Band et al. 1993) containing two patch points (or “breaks”).

However, this improved Band-Ghisellini function implies a slow cooling down (>1 s) for the particles emitting the cool component of the synchrotron radiation. The only way to explain that (while keeping the other parameters, like the magnetic field strength, at reasonable levels) is to assume a synchrotron radiation predominantly emitted by protons. Such a proton-dominated synchrotron radiation cannot be accounted for by the jetted collapsar model.

Internal inconsistencies and weaknesses of the collapsar model

Finally, the collapsar model is plagued by internal inconsistencies and mathematical weaknesses.

No suitable modelling of the prompt emission light curve could be developed so far. The light curves are chaotic, very different in each case and they have resisted any standardization and any classification attempt, other than very superficial (see e.g. Bošnjak, Duran & Pe’er 2022). The precise physical mechanism powering the prompt phase gamma emission has remained a mystery (see e.g. Hennessy et al, 2025 or Bordoloi & Iyyani, 2025). It could be a baryonic fireball or a Poynting flux dominated jet. The radiation mechanism could be synchrotron, synchrotron self-Compton, or Comptonization of quasi-thermal emission from the photosphere, none of these models fitting convincingly to the data (Zhang B.-B. et al. 2016; Poolakkil, Preece & Veres 2023; Shao & Gao 2025). The energy dissipation and particle acceleration mechanisms vary from shocks to magnetic reconnections.

The required extreme jet collimation is another modelling challenge. Most models of jet formation rely on neutrino-induced heating or magnetic collimation, without them being able to cope with observational data.

Worse, some recent works have led to the conclusion that the collapsar model was impossible altogether. The first 3D-GRMHD simulations of a collapsar demonstrated that any associated supernova was in fact entirely excluded: the collapsar’s nascent jets actually sweeps away the external star layers, while the core swiftly collapses into a black hole, preventing any supernova-like explosion to happen (Gottlieb et al. 2022).

Similarly, the jets generated by the collapsing core are supposed to explode the star’s external layers, but it is doubtful that the jet energy budget suffices to impart the kinetic energy released by the (effectively observed) SN 1c-BL. Besides, in order to transfer the required kinetic energy to the external layers, the jets should be less collimated than required by observed GRBs, or start with unreasonable energy levels (Mazzali et al. 2014).

Conclusion

By assuming highly anisotropic explosions, the collapsar model has helped us keeping long GRB “decent” by apparently reducing their total energy budget down to SN-levels or below. However, this craving for decency has led us to a dead end, with a model that does not work mathematically and was disproven by observations. Worse, it has made us blind to very interesting physics.

3. The Teranova Model

1---Binding energies of NSt vs long GRB energy releases

Long GRBs are measured to release total (isotropic equivalent) energies in their rest frame that are comparable in magnitude to the binding energy of neutron stars (NSts).

The total binding energy ε can be expressed as Mgrav=NB*mB−ε/c2 with NB is the number of baryons, mB is the mass of the baryon and the gravitational mass Mgrav is the final mass of the star once formed. Most of ε is supposed to come from gravitational binding energy (GBE), the remaining part consisting in other potential energies, notably from the strong interaction, the Pauli exclusion principle, etc.

For calculating the gravitational binding energies (GBE) of a NSt, the Newtonian formula gives a first approximation:

for the gravitational binding energy E

grav of a sphere of mass M and radius R With R

g=2GM/c

2 is the Schwarzschild or gravitational radius.

(Equation 1)

To refine GBE estimations, relativistic effects are taken into account with numerical simulations. Lattimer (2005) provided values from different models. With Rg/R=0.15, the GBE should remain around 10%. With a ratio Rg/R = 0.33, NSt should typically possess a binding energy from 17 to 35% of the gravitational mass, depending on the models.

Jiang, Wen & Chen (2019) estimated that NSt binding energies may, depending on the equation of state and compactness, take values from 5% to 50% of the gravitational mass for a non-rotating NSt from 1.40 M⊙ up to 2.47 M⊙. We shall keep in this paper the broadest interval (5 to 50%), in order to remain on the safe side.

The possible ranges for NSt gravitational masses and radii are not known accurately. According to theory, neutron stars may exist with gravitational masses between 1.44 and 2.16 M⊙. However, observational results suggest that neutron stars may exist from M=1.20-1.30 M⊙ up to M=2.50-2.90 M⊙. The most massive NSt masses measured so far are PSR B1516+02B, a 7.95 ms pulsar member of a binary system, with an individual mass M=1.94 (+0.17 −0.19) M⊙ and PSR J1748-2021B a 59.665Hz (16.76 ms) pulsar with a mass M=2.74 +/−0.21 M⊙ belonging to another binary system, (Freire 2008, Freire et al. 2008).

As for NSt radii, the NICER experiment has obtained the first precise estimations in the case of the 205.53 Hz millisecond pulsar J0030+0451. Two separate sub-projects have obtained for this object either a mass of 1.44 M⊙ (+0.15/ ‒0.14) and a radius of 13.02 km (+1.24/ ‒1.06 km) (Miller et al. 2019) or a mass of 1.34 M⊙ (+0.15/ −0.16 M⊙) and for the equatorial radius 12.71 km (+1.14/ −1.19 km) (Riley et al. 2019).

For such examples of existing NSts, the Newtonian formula gives binding energies between 9% for the smaller NSt (J0030+0451) and 17% for the larger one (PSR J1748-2021B).

Recently, the most precise estimate for a 1.4 M⊙-NSt radius was obtained by Guedes et al. (2025), at 12.48 km (+0.41/‒0.40 km), by interpreting quasi-periodic oscillations detected in the light curves of two (thirty-year old) short GRBs (namely GRB 910711A and 931101B), as quasiradial and quadrupolar oscillations of binary neutron star merger remnants.

From these models and observations, NSts may be considered to be endowed with binding energies ranging between 90 and 2,700 foe ‒ admitting a very broad interval for possible NSt mass values ranging between 1 and 3 M⊙ and a binding energy of 5% to 50% of the gravitational mass.

Long GRBs have been observed to release between 10 and 4,000 foe in isotropic equivalent electromagnetic energy, with a few exceptions below and above (see e.g. Ghirlanda et al. (2015), Caballero-Garcia et al (2023), Poolakkil et al. (2021) and Belkin et al. (2024)). That is, there is a rough match between both energy distributions, at least between the central regions of those distributions. We shall discuss the mismatch in the lower and higher segments of the spectrum at the end of

Section 4.

2---Could unbinding NSt provide the central engines for long GRBs?

This comparison suggests the idea that exploding neutron stars could indeed be the central engines of (at least a majority of) long GRBs. However, neutron stars are usually thought of as dead ends of stellar evolution. Due to their extremely strong gravity, they are supposed to have no other option than to grow further by aggregating more mass −or at best to stay unchanged − and never to decrease in size or even explode.

NSt mergers during a binary coalescence and giant magnetic flares may provide rare minor deviations to this rule, allowing NSts to liberate some of their mass. It is believed that NSts may expell 3-5*10−2 M⊙ of NSt matter during binary mergers (see e.g. Pian et al. 2017), or ~10−6 M⊙ of crustal matter during magnetic flares (Patel et al 2025).

Everybody shall agree, however, that a NSt can unbind in principle, provided it is given enough energy for its component particles to reach escape velocity ‒ that means, a tremendous amount of energy. In that paper, we argue that such scenarios do indeed occur in Nature, albeit very rarely.

(((However, since the extreme physics at play is utterly unknown, we shall restrict our discussion to energy levels and the energy conservation law as a last safe bulwark.)))

3---The Fast-Accreting Shooting NSt Scenario

The main scenario that we suggest in that paper is a collision between a hypervelocity NSt and a supergiant star, for instance a blue supergiant.

Such collisions between hypervelocity NSts and blue supergiants have barely been investigated so far, perhaps because they seem so weirdly asymetric (they pit an object of 20-30 km against one of 10(7 to 9) km) and because they have a vanishingly low probability to occur.

However, when it comes to explaining extremely rare events, very low frequency turns out to be an advantage. Indeed, long GRBs have occurrence rates of barely 2*10−9 to 2*10−10 *Gyr−1 in any given galaxy, assuming 400 events Universe-wide per year for a total number of 2*1011 to 2*1012 galaxies).

In that scenario that we call the “Fast-Accreting Shooting NSt scenario”, we begin with a NSt endowed with a very strong magnetic field ‒ a magnetar or a highly magnetized pulsar.

This object is darting within its home galaxy at a high speed ‒ typically in a range of 0.1%-1% of the speed of light. This compact star was initially (rectilinear collision, or unbound collision) accelerated either by the central galactic supermassive black hole (SMBH) or by an asymmetric SN explosion, or by a binary system companion gone supernova. Alternatively, the shooting NSt was a member of a multiple system (loop collision, or bound collision) comprising at least one NSt and one supergiant star. The NSt was deflected onto the supergiant companion after some external perturbation. Or the NSt dived into the supergiant after a coalescence process. We shall detail these different cases below.

When the collision between the blue supergiant star and the hypervelocity magnetar takes place, several outcomes are possible, depending on the striking angle, speed and spin of the shooting NSt, and on the supergiant star mass, density function and spin.

The shooting NSt might just superficially dive into some exterior layers and escape again thanks to its very high speed, or it may punch deeply into the supergiant hydrogen layers. It may possess sufficient speed to come out again at the other side of the supergiant (provided it is still there), as suggested by Hirai & Podsiadlowski (2022), or it may slow down sufficiently and inspiral around the supergiant core.

Fast Accretion

In the case of a deep dive into the supergiant, the shooting NSt will aggregate sizeable amounts of gas from the target star’s envelope.

A hypervelocity NSt punching at 0.1%-1% of the speed of light into a 30 R⊙-star (diameter 150 light-seconds) shall spend several hours or more diving across the host supergiant before escaping on the other end − even if it was not slowed down.

We argue that, due to its high speed, the shooting NSt will enter “Hyper-Eddington mode” and build an accretion torus of ~1-10 M⊙ or more within a time shorter than its host-star-crossing time.

Friction forces in the accretion torus will convert 10-20% of this accreted mass into thermal energy. This tremendous release of radiation shall be absorbed in part (perhaps as much as 50%) by the NSt at the center of the accretion torus, implying that ~0.1 to 1 M⊙ (or 180 to 1,800 foe) or more of thermal energy shall be absorbed by the NSt in a very short time (the range of most long GRBs) if 1-10M⊙ was accreted in the first place.

We argue that during this whole fast-accretion process, the shooting NSt shall be mostly shielded at lower altitudes above its surface against infalling matter absorption by its extremely strong magnetic field and, at the poles, by the radiative pressure, due to extreme temperatures, as summarized e.g. by Mushtukov et al. (2025). Therefore, it has good chance not to become a black hole before reaching critical unbinding temperature.

We argue that in favorable cases, all of this can take place during no more than (10 to 100)*103 seconds, so that the travel time within the supergiant star should be long enough to pursue this whole process until it brings the NSt to critical unbinding temperature.

When the NSt unbinds and explodes, it sequentially frees the accretion torus that had formed around it, since the central gravitationally attractive body has gone. The inner tore will be liberated first (its particles changing their trajectories from small circles to larger circles and finally straight lines). Then the median torus will deviate away similarly and then the external part of the torus. This could be one of the reasons why the long GRB explosion total energy can exceed the binding energy of the shooting NSt itself.

4---The prompt phase interpreted as the front-wave emergence into the photosphere

When the NSt explodes, the blast wave carrying the expelled particles (neutrons, protons, atomic nuclei…) propagating at close to the speed of light will create inside the supergiant an extremely violent shock along its path. This shockwave will imprint a tremendous momentum into the supergiant star’s envelope, basically blowing it away into the ISM.

We argue that the most energetic radiation of the whole process is generated along the first shock wave path. Similarly, the shells expelled by supernovae have been measured to emit their hardest X-rays along the front bubble rushing across ISM.

Since the supergiant star is optically thick, in particular for the X and gamma photons, the prompt phase that we see from the Earth should essentially consist in that first shock wave when it emerges into the supergiant star photosphere. This should be followed by the thermal radiation induced by the violent heating up of the supergiant envelope and finally followed by the scenery (if we could resolve it) of the supergiant envelope expanding away in all directions at fast speeds.

Since the front wave should reach the photosphere at different times along different directions (depending on the initial position of the NSt within the host star, relative to the supergiant center and to the Earth), and since the light needs different times to reach us from these different photosphere point locations, the gamma-ray emissions (the prompt phase) should extend over some period of time.

If we could resolve the supergiant apparent disk, we would see first a gamma-ray-shining dot along the line of sight between us and the detonating NSt. That would be the first seeing of the blast wave reaching the photosphere. This event would be followed by a growing, gamma-ray emitting ring centered on the previously shining spot. The ring would increase in radius until it reaches the edges of the visible disk of the supergiant on all sides and then disappear altogether. Immediately following these gamma-ray rings would come, at each spot, the view of the expelled supergiant layers expanding into space.

Early Afterglow: the accretion torus liberation

In most long GRBs, the (gamma-ray) prompt phase is followed by an X-ray phase divided in two parts. The first part shows a steep decay where the X-ray flux follows a power law with a coefficent α>2 and significant spectral changes. The second part is a plateau, that typically lasts 103‒104 s, with a slower X-ray flux decay (0<α<0.80) (Fiore, Menegazzi & Stratta 2025). Later on, the classical afterglow sets in.

In the teranova theory, the early steep X-ray decay phase may correspond to the ending of the NSt blast wave escaping through the photosphere. The X-ray plateau may be generated by the accretion torus ejecta crossing the (blown-away and fast-expanding) supergiant photosphere. First the very-high energy inner rings of the accretion torus, second the lower energy medium and finally the external rings. (We remind here that this plateau phase is quite challenging to account for in the collapsar model.)

The reason why the X-ray plateau lasts longer than the gamma prompt phase is that the supergiant envelope has inflated in the meantime, and that the accretion torus particles are liberated gradually, in a process that is slightly longer (lasting t=r/c with r the torus radius) than the practically instantaneous NSt explosion.

Later Afterglow: continuation of the expansion

In the teranova model, the later X, UV and optical afterglow phase, after the “jet break”, should stem from the further expansion of the NSt ejecta, accretion torus ejecta and supergiant blown-away external layers across the ISM, shocking the thin matter found there, all of them moving chaotically in all directions at high temperatures while slowly cooling down.

All of this fast-expanding matter has been heated to millions of degree by the NSt explosion shockwave rushing across, not to mention the intense synchrotron and inverse Compton scattering radiations produced by the same ejecta.

Long GRBs akin to SNe-Ia but with a NSt central engine

The teranova model implies, if correct, that long GRBs bear a deep similarity with SNe of type Ia in so far as the central engine of both is an compact star that explodes.

1a-SNe are powered by white dwarves, long GRBs by NSts. The first generate 1-2 foe of energy (out of which most in kinetic energy and 1% in e-m energy), the second thousand times more. Actually, the exact balance between e-m energy budget (that we see) and kinetic energy budget (that we almost never see due to the distance of most long GRBs) will depend on the size and final shape of the supergiant host at explosion time. If mostly wiped out, i.e. aggregated into the shooting NSt’s accretion torus, it will offer less resistance to the blast wave, implying that a larger share of the initial kinetic energy will remain as such. This goes a long way towards explaining the broad interval of long GRB e-m energy budgets from 10 to 4,000 foe.

It was possible to directly measure the residual kinetic energy share of the initial total energy budgets in just two cases, thanks to direct radio imaging, namely for GRB 030319A and GRB 221009A).

6---Associated SN of type Ic-BL

The teranova theory provides the so bitterly sought-after mechanism for generating the H&He stripped progenitor of the ensuing type-1c supernova.

When the magnetar explodes deep in the interior of the blue supergiant star, and the accretion torus is liberated, a huge tsunami of high-Lorentz factor ejecta (typically up to a few thousand foe), much larger than those of classical supernovae (1 foe for 1a-SNe) is released. The explosion blows away all the supergiant star’s remaining H and He layers.

If the NSt blows up far enough from the blue supergiant star core, then we may expect this core to overcome the explosion in relatively good shape, to some degree (albeit with some imprinted momentum), because it is more strongly gravitationally bound than the rest of the supergiant star. This creates the stripped core.

That stripped core later evolves into a SN 1c-BL a few hours or days later, depending on the quantity of H and He nuclear fuel left inside of it.

The broad line (BL) type of supernova, i.e. the very high photosphere expansion velocities, may be explained by the abrupt heating up of the core induced before the explosion by the interaction with the spinning NSt’s magnetic field. That very strong and rotating magnetic field of the shooting magnetar triggers electrical currents in the supergiant core, transferring tremendous amounts of energy to it while slowing down its spin rate.

Indeed, as hinted at by Mazzali et al. (2014), the measured kinetic energy level of the SNe 1c-BL associated with long GRBs never exceeds the maximum rotation energy of a NSt, that is, roughly, 20 foe ‒ a budget which exceeds by 20 to 2,000 times the kinetic energy of a typical core-collapse supernova (Mazzali et al. 2014).

7---Associated SN… or not

To explain why some long GRBs appear to be associated with a supernova, and some not, the teranova model offers two different explanations, that apply to different cases.

In the first case, the explosion takes place close enough to the blue supergiant center to smash the core into pieces, leaving no SN-progenitor behind. The burst ends up lacking any associated SN.

In the second case, the shooting NSt is situated in front of the supergiant core, as seen from the Earth. The high-energy hotchpotch produced by the NSt unbinding NSt & accretion torus liberation, and the overheated expelled supergiant star external layers, forms an optically thick curtain that keeps the ensuing associated SN, on the other side of the hotchpoth, undetectable.

For comparison, Ryu et al. (2024) found that the cloud expelled by two red giants colliding at 1,000 km/s (a cloud very similar in content and temperature to our ejecta) would remain optically thick for typically 7-8 months. Usual SN ejecta are known to be optically thick.

This second explanation (SN hidden from view) matches well with the empirical fact that, in the case of relatively nearby bursts, half of them appear not to show any associated SN (as obtained by Dado & Dar 2018 A). Indeed, if randomly distributed, the shooting NSt should detonate about half of the time within the near hemisphere of the host supergiant star, and about half of the time in the far hemisphere. This explanation also harmonizes well with the fact that only blueshifted (and no redshifted) GRB-SNe have been discovered (Modjaz et al. 2016).

In summary, the shooting NSt model offers a natural explanation to four open issues: (1) why all associated SNe belong to type 1c (2) how their progenitors are created, (3) why an associated SN is detected only about half of the time, and (4) why they all seem blueshifted, to different degrees, but never redshifted.

3---Existing studies on collisions between hypervelocity stars

Collisions involving massive stars or hypervelocity stars have been studied in specific cases.

Balberg, Sari & Loeb (2013) and Balberg & Yassur (2023) have theoretically investigated such events within dense stellar clusters orbiting around the central galactic black hole. Kremer et al. (2020) have simulated stellar collisions leading to intermediate-mass black holes of above 50 M⊙. Balberg, Sari & Loeb (2013), Balberg & Yassur (2023), Dessart et al. (2024) and Ryu et al. (2024) focused on collisions between same-size 1 M⊙ red giants in dense stellar clusters of galactic centres at relatively modest speeds v>100 km/s. They found that even as such non-hyper-velocities, 10% of the kinetic energy of the incoming red giants was converted into thermal energy, producing a supernova-like transient.

Kremer et al. (2022) have investigated collisions of NSts with main sequence stars between 0.5 and 1.5 M⊙ in globular clusters to investigate the formation of millisecond pulsars.

However, collisions between hypervelocity neutron stars and supergiant stars have been studied remarkably little. The research coming closest to our GRB-producing scenario was conducted by Hirai & Podsiadlowski (2022), who have numerically simulated a shooting 1.4 M⊙ NSt punching at 1,000 km/s into different stars from 1 up to 10 M⊙. In their scenario, the shooting NSt was born out of an asymmetric SN explosion in a tight binary system and it rushed by chance right into its companion.

The authors tested target companion stars with masses M=1, 5, 10 M⊙ and radii R=0.94, 2.53, 4.82 R⊙. The latter case is of interest to us as it belongs to the (inferior segment of) the supergiant class.

The authors have studied how the supergiant star external layers evolve during this disruptive event ‒ swept away or rearranged ‒ as well as the incoming NSt trajectory during and after its diving into the target star. They demonstrated that in some cases the shooting NSt entirely cross the target star, and may even come back and delve again into the target supergiant.

The authors did not, however, focus on the processes that are of interest to us here, namely the accretion process around the NSt during its deep-dive into the supergiant, potentially leading to its overheating. They were mostly interested in the binary system dynamics at large. They have restricted themselves to hydrodynamical simulations with gravity as the only acting force (enforcing linear&angular momentum as well as kinetic+potential energy conservation). They did not include magnetic fields, nor friction forces, nor thermal energy at this was not in their focus. Neither did they attempt to develop realistic gas accretion processes around the shooting NSts, since the applied simulation grid within the 3 tested stars consisted in 600 steps in the radial direction, i.e. about 6,000 km between grid points on average in the case of the larger star. Such spacing was not meant to simulate the gas accreting around a 25 km-wide NSt. The implemented simulation would basically remain the same with a compact object of same mass and 2,000 km radius. Moreover, the authors used a cubic-spline kernel to soften the gravitational potential of the point-like NSt. The adaptive adjustment led to softening lengths of up to 3 grids points, i.e. much larger than the physical size of the NS, and therefore their calculations did not model the accretion flux. Also, they did not touch the part of the star family that is of most interest to long GRBs, namely the supergiants with masses M>10 M⊙.

9---Fast Accreting Shooting NSt Energetics

Obstacle Supergiant Star

In order to be able to foster a classical, cosmological long GRB, the supergiant star encountered by the shooting NSt along its way should contain a mass in excess of M≈50-100 M⊙, with a radius R≈20-200 R⊙ It should belong to the category of the (blue, yellow and red) supergiants of the kind of Zeta Puppis (56 M⊙, 20 R⊙ or 50 light-seconds), Epsilon Orionis/ Alnilam (64 M⊙ 42 R⊙ or 100 light-seconds), Eta Carina A (100 M⊙, 240 R⊙ or 600 light-seconds), Rho Cassiopeiae (40 M⊙, 700-900 R⊙ or max 1,750-2,250 light-seconds) or R136a1 (200 M⊙, 43 R⊙ or 120 light-seconds). In some cases, for magnetars having masses in the lower range, even a star like Alpha Cygni (20 M⊙, 190-220 R⊙ or 500 light-sec radius) or Beta Orionis (Rigel), 18-24 M⊙, 67-80 R⊙) might be big enough to provide enough fuel reserves. We shall say “blue” supergiant to simplify, because blue supergiant stars are the most frequent case, but our supergiant host could basically be either blue, yellow or red.

A diameter of 20 to 200 R⊙ (50 to 5,000 light-seconds) implies that the shooting NSt, even at one percent of the speed of light, shall need, before escaping at the other end of the supergiant, even if not slowing down, at least 5,000 to 500,000 sec (1.5 to 15 hrs), likely giving if sufficient time to accrete enough material to overheat, even if numerical simulations will need to confirm this in more detail.

Speed at collision time

A shooting magnetar diving into a supergiant star will need a minimum speed to continue zipping through its host and so as accrete further until overheating. Otherwise, the shooting NSt would grind to a halt before reaching critical temperature, and plunge down to the core, where it could build a static Thorne-Żytkow object (a supergiant containing a NSt in its core). A speed of 1,000 km/s should be sufficient, since like Hirai & Podsiadlowski (2022) have shown, a shooting NSt endowed with that speed can cross a whole 10 M⊙-star and re-emerge on the other side. But lower speeds like 500 km/s may suffice as well, since a NSt belonging to a binary system with a supergiant will touch upon that supergiant (after coalescence or after some external perturbation) at typically 500-1,000 km/s, and since it seems likely that this binary evolution process (loop or bound collisions) should be the most prevalent collision type in the Universe for producing long GRBs. Numerical simulations will yet need to be done to settle this minimum entry speed issue.

Hypervelocity Neutron Stars have been observed even outside of multiple systems. In the Milky Way (MW), young (independent) NSts have been observed darting at velocities of several hundreds of km*s-1 (i.e. of the same order as the galactic escape velocity). Some pulsars have been found to exhibit speeds exceeding 1’000 km*s-1, like the central compact object RX J0822-4300 with 1,100 km/s or like PSR B1508+55 with a transverse speed of 1,083 km/s (Sartore et al. 2010).

Pulsars may also reach such speeds by evolving into NSts from hypervelocity main sequence massive stars. The first hypervelocity hydrogen-burning star (HVS) was discovered by Brown et al. (2005). It displayed a radial velocity of 853 km/s. In the meantime, over 1,100 hydrogen-burning HVSs have been found, with speeds ranging from 445 km/s up to 3’000 km/s in the galaxy rest frame, out of which 591 were discovered in the Data Release 7 (DR7) of the Large Sky Area Multi-object Fiber Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST) and the second Gaia data release (DR2) (Li Y.-B. et al. 2021).

Hypervelocity NSt formation mechanisms

We may list 9 possible scenarios leading to a hypervelocity NSt colliding with a supergiant star.

The first 7 cases involve independent (unbound) HV NSt and may be described as leading to “rectilinear collisions” or “unbound collisions”. The Cases 8 and 9 involves NSts that are parts of a multiple systems and may be called “loop collisions” or “bound collisions”.

Case 1 − A NSt is generated by a core-collapse SN and is accelerated by an asymmetric explosion.

Case 2 − A NSt is member of a multiple star system (binary or higher multiplicity) and is ejected when one companion goes supernova, without intercepting its companion, as first conceptualized by Zwicky (1957). Tauris (2015) theoretically investigated the maximum possible velocities for such HVSs (of type G/K dwarfs and late-type B stars) if they are produced from very close binaries disrupted by a core-collapse supernova explosion. They found possible speeds up to ∼770 and ∼1,280 km/s in the Galactic rest frame.

Case 3 − The NSt (resp. its progenitor) may be expelled from a dense stellar cluster, following N-body interactions (see e.g. Sartore et al. 2010).

The four next cases involve interactions with a central galactic supermassive black hole, single or binary (SMBH/SMBHB).

Case 4 ‒ Tidal breakup of binary star system by a (single) central galactic SMBH. This mechanism was first put forward in a prescient paper by Hills (1988), who therein coined the name “hypervelocity star”. The author suggested that a stellar binary interacting with the Milky Way’s central black hole, if the latter existed, could eject one of both stars away from the other at a velocity of up to 4’000 km/s. At this time, the central Milky Way SMBH was only hypothesized and no HVSt had yet been discovered. Hills went on to suggest that the discovery of such an object would provide solid evidence for the existence of a SMBH at the center of the Milky Way.

Case 5 ‒ Single-star encounter with a (binary) central galactic SMBH. Guillochon & Loeb (2015) have shown that the process can accelerate stars up to 30% of the speed of light, or more.

Case 6 ‒ Single-star encounter with a cluster of stellar mass black holes around the central SMBH.

Case 7 ‒ Interaction between a globular cluster with a single or binary SMBH in the galactic center (Rasskazov et al. 2019).

Cases 8 and 9 take place within binary or multiple systems, describing “loop collisions” or “unbound collisions”.

Case 8 − A NSt orbiting around a supergiant star (typically a X-binary or a higher-multiplicity system) could rush into its companion after undergoing some external perturbation, or due to the system intrinsic instability. Such events should be more frequent in high-density blue galaxies.

Case 9 − A NSt orbiting around a supergiant star (typically a X-binary or a higher-multiplicity system) ends up merging in a classical coalescence scenario. Such an inspiralling towards the supergiant would obviously need, to produce a teranova, to be completed before the end of the supergiant’s life, i.e. within a few million years. For a very tight or very excentric binary, one could imagine the coalescence to be accelerated by the orbiting NSt being deflected into the supergiant by rubbing (via gravitational tidal forces and magnetic field interactions) the atmosphere and photosphere of its companion at each flyby.

For a binary system comprising one 1.5-M

⊙ NSt and one 50-60 M

⊙ star (like Zeta Puppis with M=56 M

⊙ and R=20 R

⊙ or Epsilon Orionis/ Alnilam with M=64 M

⊙ and R=42 R

⊙), the typical NSt orbital speed when approaching the supergiant photosphere is given from the Newtonian gravitational force by:

(Equation 2)

For a given NSt mass (say 1.5M⊙), the only relevant factor is √(M/R) of the supergiant. We have for example vdelving=900 km/s for Zeta Puppis and vdelving=660 km/s for Epsilon Orionis.

Possible energy sources for heating up the shooting NSt

As possible energy sources for heating up our shooting NSt during its crossing of the blue supergiant star, on top of its preexisting internal (thermal) energy, we may list the initial kinetic, rotational and magnetic energies of the incoming shooting magnetar. Those can be transformed, at best at 100%, into heat via friction and magnetic interactions. Finally, there is the energy radiated inwards by the accretion torus that shall form at fast pace during the NSt rushing across the supergiant.

A quick review of these energy sources makes clear that the latter source (the accretion process) is the only one they may contribute significantly to the (gigantic) energy budget required for the NSt to reach critical temperature.

The kinetic energy would need a HV NSt exceeding half the speed of light to play a significant role. No such object has ever been found, and we may assume that such relativistic speed NSt come up too rarely in Nature to play a significant role. The rotational energy may power only low-luminosity long GRBs, up to 100 foe (see e.g. (Mazzali et al. 2014). The magnetic energy budget even of the most extreme magnetars does not exceed 0.01 foe (see e.g. Igoshev, Popov & Hollerbach (2021). Finally the thermal energy at typical collision time (with the shooting NSt age expected to be aged over 1,000 yr) will not provide a significant amount of the gravitational binding energy (at most 1%), as opposed to what was the case in the early instants after their creation.

The latter conclusion may change in one case, namely in the Hirai-Podsiadlowski process, where an asymmetric SN in a binary system sends a freshly born NSt right into its companion star by chance. In such a (rare) case, given a distance between both companions not exceeding 1 light-week to 1 light-month and a speed of roughly 0.01 c, we might end up with a very young (1-10 yr-old) NSt at collision time. In such a rare case, the shooting magnetar may still contain a significant amount of thermal energy, i.e. it would request a much lower energy input to unbind and could thus reach burst status with a less massive companion as co-progenitor.

10---From Super- to Hyper-Eddington mode

The hypervelocity NSt will gravitationally dominate a large sector of the supergiant when punching into it. It will build up an accretion disk by grabbing sizeable swathes of matter from the supergiant envelope.

Along its path within the supergiant, the shooting NSt will basically dig a “tunnel” of radius rtunnel proportional to the Hill radius, i.e. rtunnel = a*rHill with 0<a<1.

The gas captured by the shooting NSt will accumulate into an accretion torus. The NSt itself should absorb directly only a tiny portion of this infalling matter, since it is shielded by its strong magnetic field and high spin rate and ultra-hot polar regions emitting hard X-rays.

Depending on its initial speed and striking angle, the NSt may begin to inspiral around the supergiant core, doing several orbits before reaching critical temperature, or it may run along an almost straight line. We argue that it shall be able to capture during this deep dive a significant amount of gas, i.e. several solar masses, into its accretion torus.

Inside the supergiant star, the shooting NSt is surrounded by a sphere of gravitational influence, or Hill sphere, extending over a radius (Hill radius) of

(Equation 3)

with d the distance between the NSt and the supergiant center and α=(MSupG/MNSt).

Implying that the ratio of Hills sphere volume V

Hill to Supergiant volume V

SupG is given at the time of diving (d=R) by:

(Equation 4)

If we take as example a 2M⊙-NSt and as coprogenitor Zeta Puppis (56 M⊙, 20 R⊙ or 50 light-seconds) for illustration purposes, we obtain (α=28) a Hill radius at rHill=0.23*RSupG =11 light-sec, and the Hill sphere reaching about 1.1% of the total supergiant mass, i.e. comprising 0.64 M⊙ assuming a homogenous density. Even if staying at the same distance from the core, after diving, and running in a circular orbit around the core, the shooting NST&torus system would need roughly to continue along 10 times the Hill diameter, i.e. 4.6 RSupG i.e. not even one full circle inside the supergiant, to aggregate about 6 M⊙ – sufficient matter to bring the NSt into critical temperature, assuming a binding energy of 30% of the gravitational mass and assuming that 10% of the accreted matter goes into heating the NSt. A curved path inside the supergiant reaching several radii in length can be achieved by the NSt, while rushing in a straight line, in case the supergiant is rotating in the direction inverse to the transverse NSt speed vector component.

This means that we have sufficient fuel reserves for any long GRB scenario. Given that supergiant stars can reach masses of 100 M⊙ and even more, and given that 10-20% of the accreted matter can be transformed into pure energy by friction forces, and given that 20-40% of that thermal energy may be absorbed directly by the shooting NSt at the center, we obtain that we have in principle enough energy (in the largest supergiant stars) to feed any long GRB isotropic energy budget.

Eddington obstacle

The Eddington luminosity is defined as an upper “limit” for the mass transfer rate above which the inside-out radiation pressure from the warming accretion sphere should exceed the outside-in gravitation pressure from the infalling gas, impeding further growth of the mass transfer rate.

The Eddington luminosity is generally estimated, for a NSt, in the spherical hydrogen accretion case, at:

(Equation 5) (Bachetti et al. 2022).

Empirically, it has been noticed that, in our Galaxy, all known High-Mass X-Ray Sources (HMXR) or High-Mass X-Ray Binaries HMXB) are indeed staying below their Eddington luminosities. A study by Sidoli & Paizis (2018) of 56 galactic and 2 extragalactic HMXRs monitored by ESA’s INTEGRAL satellite between 2002 and 2016 has obtained peak luminosities ranging from 1035 to 1038 erg/sec, with a maximum value measured at 3*1038 erg/sec.

ULXs

However, some HMXRs in nearby galaxies (the so-called Ultra-Luminous X-Ray sources, ULXs) have been observed to sometimes significantly outshine their Eddington luminosities. During periods of time, these ULXs radiate so brightly that they were initially thought to be powered by black holes. These super-Eddington ULX objects dominate the X-ray landscape in their host galaxies, accounting for up to 80% of all X-ray emissions (Misra 2023).

Since then, a dozen of these ULXs have been unambiguously identified as harboring NSts (Li L. et al. 2024), thanks to the discovery of spatially coincident radio pulsars (hence the acronym PULX for pulsating ULX).

Furthermore, the ULXs in nearby galaxies have been observed to exceed their Eddington “limit” by a factor of 10, 100 and even 1,000.

The first super-Eddington ULX to be discovered was M82 X-2 (Bachetti et al. 2014) in the M82 galaxy at a distance of 3.1-4.7 Mpc (Bachetti et al. 2022). During some phases of intense activity, M82 X-2 has been recorded to exceed its Eddington luminosity ceiling or “limit” by a factor of 100; it typically reached peak luminosities of LumX =1.8×1040 erg/sec (Bachetti et al. 2014).

M82 X-2 has an orbital period (in the binary) of 2.532948(4) day, a semi-major axis of 22.215(5) light-sec, and a magnetic field of 109 to 1010 Tesla (Bachetti et al. 2022). The pulsations have an average period of 1.37 s (with a 2.5 day sinusoidal modulation). The pulsations result from the rotation of a magnetized neutron star, and the modulation arises from its orbit in the binary system. The pulsed flux alone corresponds to LumX in region (3‒30 keV) = 4.9×1039 erg s-1. The pulsating source (M82 X-2) is spatially coincident with a variable ULX which can reach LumX=1.8×1040 erg/sec in the 0.3‒10 keV range. This association implies a luminosity ~100 times the Eddington “limit” for a 1.4 solar mass object (Bachetti et al. 2014).

There have been suggestions that we could be observing an anisotropic emission, so that the real total radiation rate would be much lower. The idea would be to interpret these ULXs as highly collimated beams pointing at us by chance (in the same way as LGRB-collapsars).

However, attempts to settle the iso/aniso-tropicity debate from observational data have failed, in the case of NGC 6946 X-1 (Beuchert et al. 2024). Furthermore, the orbital decay of M82-X2 was recently measured over a time interval of 7 yr. It was shown to be compatible with an average mass transfer rate between the donor (8 M⊙) and the pulsar (1.4 M⊙) exceeding 150-200 times the Eddington limit, which confirms that the peak emissions (up to 100 times over Eddington “limit” during flares) could indeed have been isotropic and powered by an over-Eddington mass transfer rate. (Bachetti et al. 2022).

Other examples are the two ULXs in the NGC 7424 galaxy at 10.8 Mpc (i.e. 2CXO J225728.9−410211 (X-1) and 2CXO J225724.7−410343 (X-2)), that both have been observed to reach 1040 erg/sec during some intense phases (Soria et al. 2024) and the ULX of galaxy NGC 7793 with a 0.42 sec pulsar called NGC7793 P3 reaching at times 5*1039 erg/sec (Israel et al. 2017 A).

The record-holder ULX so far is the pulsar in the NGC 5907 galaxy that was found to outshine its Eddington luminosity by a factor 1,000 with LumX =[1.9 to 2.5]* 1041 erg/sec (if isotropic) during a short period, as measured by XMM-Newton on 28 Feb 2003 and 09 Jul 2014 (Israel et al. 2017 B; Pintore et al. 2018).

The Mechanism Behind The Super-Eddington Mode

These ULX observations imply that neither the Eddington mass-transfer-rate, nor the Eddington luminosity are real “limits” in the strict sense. They should rather be considered as phase transition points, i.e. as obstacles that can be overcome with sufficient pressure from the environment, that is, given a very strong external forcing of the matter inflow rate.

Recently, even a supermassive black hole (SMBH) has been observed to reach Super-Eddington mode. JWST observations have revealed that LID-568, a SMBH with a mass of 7.2*106 M⊙ at redsift z≈4, is reaching a luminosity of 40 times its Eddington value. This could help explaining why supermassive SMBHs have formed so early in the history of the Universe (Suh et al. 2025).

In the meantime, theoretical models have been developed to describe the super-Eddington modes of ULX binaries (see e.g. Ghodla & Eldridge 2023; Heinzeller & Duschl 2007; Chashkina, Abolmasov & Poutanen 2017; Dall'Osso, Perna & Stella 2015).

The results show that, if a NSt is initially submitted to an intense (super-Eddington) overflow of infalling matter, and if this strong flow proves persistent, a new phase sets in. The inner accretion disk becomes thicker vertically (i.e. along the direction of the rotation and magnetic field axes). The accretion disk evolves from a thin disk to a thick disk (Chen & Dai 2024).

The thickness H increases with stronger mass inflow like:

(Equation 6) (Chashkina, Abolmasov & Poutanen 2017)

This accretion torus thickening makes the inner part radiatively inefficient, i.e. optically thick. Its internal temperature increases without its outward radiation pressure to follow suit, which allows the super-Eddington flow to continue unabated (Dall'Osso, Perna & Stella 2015).

Besides, the central NSt’s extreme magnetic field impedes most particles to fall closer to the NSt surface than the magnetic radius, shielding inside the so-called magnetosphere our NSt against too much fattening.

The accretion disk inner limit radius R

inner decreases with stronger mass inflows like

(Equation 7) (Chashkina, Abolmasov & Poutanen 2017)

where RA is known as Alfvén, or Alfvénic, radius, μ is the neutron star magnetic moment and (dM/dt) is the accretion rate. The dimensionless coefficient zeta (ξ) is determined by the accretion flow structure. For instance, for spherical accretion, ξ=1.

Below the magnetosphere radius RA, all particles are deviated along the field lines to the regions situated above both magnetic poles. Some of the deviated particles shell the polar caps, that consequently undergo fast heating and shine heavily in X-rays. But most of the particles accumulate in two accretion columns located above both poles.

These accretion columns were first predicted by Basko (1976). They are now a robust feature of numerical simulations. These accretion columns may feed plasma jets, alleviating the pressure inside the columns. These jets should dart into the supergiant layers (ironically like the collapsar jets, but without necessarily escaping the host star) recycling the unused gas out of the torus back into the supergiant star.

The columns are maintained at some distance from the poles by the pressure of the keV radiations emitted by the overheated polar regions. The accretion column radiates radially (in the NSt rotation axis cylindrical coordinates), as was established by magneto-hydrodynamical (MHD) simulations (Zhang L., Blaes & Jiang 2022 and 2023).

In summary, given large enough mass transfer pressure, passing the Eddington luminosity hurdle has been proven possible for an accreting NSt, observationally and theoretically.

From Super- to Hyper-Eddington

Starting from this ULX Super-Eddington mode, we argue that an even more intense mode, that we shall call “Hyper-Eddington mode”, can set in the case of our magnetar punching with extreme speed into a blue supergiant star and building up an accretion disk at a tremendously fast rate. This new mode shall basically be identical to the ULX one, just with all parameters reaching much higher values.

The super-Eddington mass transfer rate estimated to take place in the binary M82-X2 amounts to 4.7*10−6 M⊙/yr. As this NSt shines at about 100 times its Eddington luminosity, we could call this hecto-Eddington mode and kilo-Eddington mode in the case of the NGC 5907 ULX.

As for our shooting NSt diving into a blue supergiant and capturing into its accretion torus up to 10-20 M⊙ in up to 100 hours, we shall coin the expression “Tera-Eddington” mode, since it should undergo a much higher mass transfer rate of typically 109 to 1010 times stronger.

We argue that a Tera-Eddington mode may occur in Nature provided the afore mentioned necessary conditions are met ‒ even if this mode is exceeding the most extreme rate known so far, namely the kilo-Eddington mode of the ULX of NGC 5907, by a large factor.

It is beyond doubt that a pulsar shooting with high speed into a supergiant star shall be exposed to a dramatically stronger influx of matter than a pulsar slowly nibbling at its companion’s envelope, over the Roche lobe, from a farther distance.

Moreover, none of the recent research on Super-Eddington modes have fallen across any new, higher upper limit for the accretion rate above the previous Eddington “limit”. More observations and more modelling shall obviously be needed before we may confirm the existence of this tera-Eddington mode.

Exponentially increasing heating rate

Inside the accretion torus, the heating of the central shooting magnetar should become a self-reinforcing process. To begin with, the matter inflow rate increases steadily, since the accretion process will raise the torus mass, which will in turn increase the Hill radius, increasing the influx rate, and so on. Second, the stronger accretion rate will make the inner part of the accretion disk thicker and thicker, thus insulating more efficiently, thereby applying a growing share of the (itself growing) thermal energy produced in the torus into heating the NSt. Third, the innermost particle orbit in the disk becomes smaller with increasing infalling matter mass and thus pressure. The accretion torus will thus convert by friction a higher proportion of the infalling mass into energy per unit mass.

As a result, the accretion torus in Hyper-Eddington mode will work like an inferno oven fed with an increasing flow of fuel just while increasing its heating-efficiency with higher temperatures... It is straightforward to conclude that our shooting NSt shall undergo an exponential temperature rise with no other issue, if the game goes on long enough (i.e. if the host supergiant star is large enough and the initial shooting magnetar speed high enough), than reaching critical temperature and unbinding.

Maximum energy budget

From the size of the largest stars, we may infer that the total quantity of fuel available to feed the fast-accreting shooting star scenario is in principle sufficient to account for any known long GRB, including the BOAT. 15’000 foe (8.3 M⊙) could have been produced with a total efficiency rate of 10% by a large target supergiant containing at least 100 M⊙. Such objects are known to exist. For these estimates to work, we must assume that the gamma-ray and hard X-ray energy release (i.e. the e-m Eiso that observatories have been measuring so far) represent the largest share of the total initial kinetic energy budget, at least in the most energetic bursts (say 70-80% or more), with the final kinetic energy remaining in the ejecta representing a smaller share.

11---Model Naming

Following the “nova” naming trail convention, we have coined the term “teranova” by following the peak luminosity trail.

Long GRBs typically reach peak luminosities of 1051 to 1052 erg/sec, whereas a classical nova typically reaches an absolute peak of 1039 erg/sec.

Along the same path, the term kilonova was introduced by Metzger et al. in 2010 to characterize the peak brightness of the radioactive decay glow arising from neutron star binary merger ejecta, which they showed should reach roughly 1,000 times that of a classical nova.

If following the total energy release trail, we would have called our model “giganova”, since long GRBs may reach between 4*1052 and 4*1054 ergs in total isotropic equivalent electromagnetic energy, whereas classical novae typically emit 3*1044 to 2*1045 ergs in optical light.

4. Submitting The Teranova Model To Observations

In this section, we shall show that the teranova model can account quite well for most observational data and offers satisfactory answers to theoretical issues (in any case more satisfactory answers than the collapsar model).

1---Host Star Radius from Burst Duration

If we get back to the hypothesis that the intense gamma-ray emission (the prompt phase) observed at the beginning of the burst is mainly emitted by the blast wave of atomic nuclei and baryons expelled by the exploding NSt at the exact points in time when they emerge into the supergiant star’s photosphere, then the apparent duration of the gamma phase as measured from the Earth should provide us an estimation of the supergiant original radius.

We assume that the ejecta front wave propagates at practically the speed of light radially in all directions. This makes sense, given their initial temperatures of at least 1013 K and is further confirmed by the results of direct afterglow imaging for GRB 030329 and 221009A (Taylor et al. 2004 and Giarratana et al. 2024). We define R as the supergiant star radius and we assuming a spherical shape in a first approximation. We call d the distance between the Earth and the blue supergiant photosphere’s nearest point to the Earth. We may then constrain the minimum and maximum possible supergiant radius by deriving the first and last arrival times of the gammay-rays in the four possible geometrically-extreme spatial positions of the exploding NSt within the blue supergiant star:

First extreme position: the NSt unbinds within the blue supergiant star just below the photosphere point that is nearest to the Earth. In that case, the gamma radiation will begin to shower on the Earth at time t=d/c (as counted in the supergiant rest frame with t=0 at the explosion start). This of course describes the ejecta rushing straight towards us. The latest gamma-rays to reach the Earth shall be the ones sent by the baryons first receding from us at an angle of 45 degrees to the line of sight and then reaching the farthest point of the photosphere still visible to us ‒ on the edge of the projection disk. These gamma-rays shall reach us at the time t=d/c+(1+sqrt(2))*(R/c). That means that the total prompt phase duration shall read (in the supergiant star rest frame), assuming the host star to be optically thick (so that we see nothing of the blast wave rushing into the far hemisphere).

, that is:

∆t being the prompt phase duration in the supergiant star’s rest frame and R the supergiant radius.

(Equation 8)

Second extreme position: the NSt unbinds in the central region of the supergiant star, close to the core. In that case, the gamma rays will last from t=d/c+R/c until t=d/c +2*(R/c) in the optically thick case, that is,

(Equation 9)

Third extreme position: the NSt unbinds close to the edge of the supergiant disk, as seen from the Earth. In that case, the gamma rays will last from t=d/c+R/c until t=d/c +3*(R/c) in the optically thick case, that is

(Equation 10)

Fourth extreme position: the NSt unbinding takes place close to the farthest end of the blue supergiant, as seen from the Earth. In that case, the gamma rays will last from t=d/c +2*(R/c) to t=d/c+(1+sqrt(2))*(R/c) in the optically thick case, that is

(Equation 11)

Hence, the destroyed supergiant star must have had an original radius, in the optically thick case, now expressed as a function of the prompt duration ∆t

obs as measured in the observer’s time, that shall be comprised between:

(Equation 12)

For short:

(Equation 13)

We shall call this formula the Prompt-Duration-Host-Radius Formula.

For the cases with redshift z>0.1 where relativistic effects need to be taken into account, we notice that all the prompt durations (in the 4 extreme geometrical cases) measured in the burst rest frame will need to be multiplied by a factor (1+β) where beta is the apparent recession speed of the Earth as seen from the supergiant coprogenitor (or the cosmological recession speed of the supergiant as seen from the Earth) in order to obtain the observed time interval. Indeed, the distance Earth-supergiant should increase by an amount of vcosmol*Δt during the prompt phase duration. Which means that the light will need vcosmol*Δt/c to cover that increase in distance. Hence, to recover the real rest frame duration from the observed time interval, we need to divide the observed time interval by the factor (1+β)

On the other hand, the exact parameter for measuring the time dilation between rest frame and observer frame is the (cosmological) Lorentz factor Γ of the host galaxy, given by the formula γcosmol=(1+z)/(1+βcosmol) where gamma is the Lorentz factor of the receding host galaxy. We end up with equation (13) agaun:

For short:

(Equation 13 again)

By setting c=1, we obtain the radius in light-seconds. The logarithmic expectation value of the supergiant star radius is thus given in light-seconds by the prompt phase rest frame duration directly.

This formula represents of course a first approximation, since the real-life explosions may involve some degree of dirtiness, i.e. the blast wave may not be entirely spherically symmetric (particularly in case of excentric position of the shooting NSt inside the supergiant when unbinding), the supergiant star may possess huge lobes and not be exactly spherical, not to mention that the supergiant star may have been already partially destroyed (by the shooting NSt) when the detonation takes place, which will tend to reduce its spherical symmetry and to weaken the optical thickness hypothesis.

A further problem is that the estimation interval remains quite broad, with an uncertainty by a factor of six. Nevertheless, this represents a significant improvement, since it allows for the first time to interpret the prompt phase light curve in a straightforward way and to obtain physical information about the coprogenitor.

Moreover, the detection or non-detection of an associated SN shall now help us localize the exploding NSt within the host supergiant, i.e. narrowing the uncertainty interval on the supergiant radius.

2—Ultra-long GRBs linked to largest supergiant stars

Since ultra-long GRBs (ULGRBs) have been identified as a category of their own in the 2010s, there has been some debate regarding their classification, i.e. on whether they represent the tail of the long burst duration distribution, or whether they proceed from an entirely different kind of central engine.

In the teranova model, the ultra-long GRBs represent a critical testing ground. Indeed, the prompt duration host radius formula implies that the UGRBs must have taken place inside larger host stars, and that’s all. Apart from that, ULGBs are just long GRBs like the others, like their identical phenomenology suggests.

Now, if the theory is correct, the supergiant host radii obtained from the Prompt Duration Radius formula should never exceed the empirically-known maximum possible sizes of supergiant stars, even in the case of record ultra-long GRBs. This provides a first testing ground for the teranova model.

This plausibility check only works provided we are considering ULGRs that emit continuously, i.e. if excluding those ultra-long GRBs that show distinct emission episodes, separated by long quiescent periods ‒ hinting at another phenomenon. The latter category, like the double-peaked GRB 220627A, shall be dealt with in a following paper.

The case of the longest ultra-long GRB 111209A

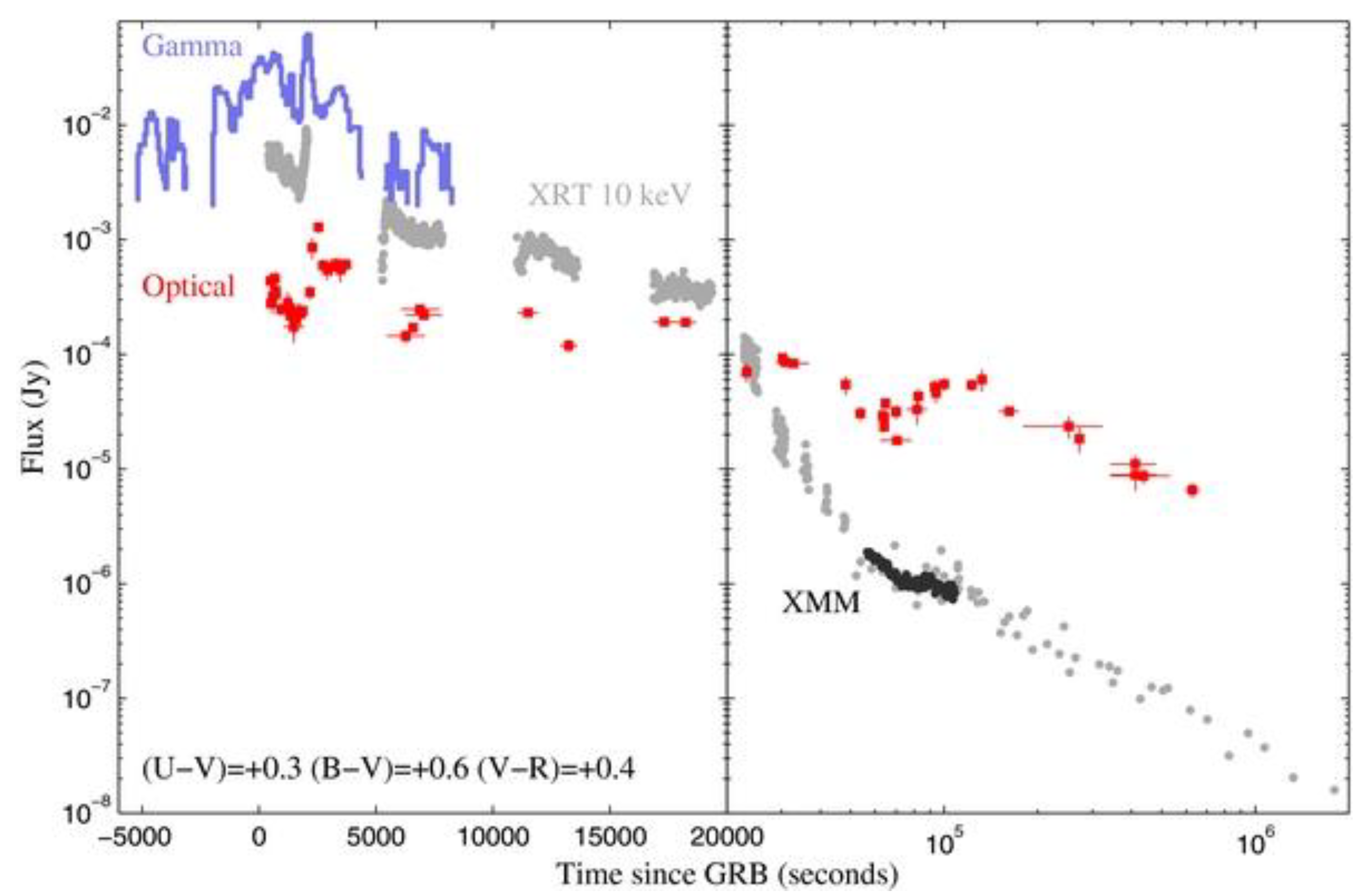

For our plausibility check, we thus rely on the longest continuous ULGRB ever recorded, namely GRB 111209A, using the observational data (

Figure 1) provided by Gendre et al. (2013).

This burst lasted in its gamma phase approx. ~8,000 sec. As the burst took place at a z=0.677, we obtain that the prompt phase lasted ~4,770 sec in the local rest frame. This indicates according to our Prompt-Duration Host Radius formula that the host supergiant star radius reached between 780 to 4,600 R⊙ (or 1,950 and 11,500 light-seconds).

The upper limit for supergiant radii is believed to lie around 1,500 R⊙. The estimated radius bracket is thus compatible with observational data. Furthermore, for the lower value part of the formula to apply, we must conclude that the shooting NSt has exploded either on the near side of the host supergiant, or close to the edge of the projected disk. The discovery of a very luminous supernova (SN2011kl) associated with the burst eliminates the first scenario. Hence, we must assume a detonation close to the projected disk edge, in which case we need to use R=c∆t/2. We thus obtain R=(4770/2)/2.5=950 R⊙.

Hence, the teranova model framework passes the ULGRB plausibility test. These ultra-long bursts can now be integrated smoothly into the general model describing long gamma-ray bursts.

The host supergiant star of GRB 111209A must have been similar for instance to the yellow supergiant Rho Cassiopeiae (40 M⊙, 600-1,000 R⊙) or to the red hypergiant Mu Cephei (25 M⊙, 970-1,270 R⊙).

3---The meaning of the 2 sec threshold

This analysis above allows us to interpret the typical lower limit for a LGRB duration (about 2 sec in the rest frame) as implying that, from the Prompt duration host radius formula, the bursts may be hosted by stars with radii of R=0.3 to 2 R⊙ and not smaller. Keeping the higher end of this interval, we may tentatively conclude that R=2 R⊙ should represent a lower limit for typical LGRB host star radii.

For clarity purposes, we define a burst proceeding from an NSt unbinding as a “major burst” (usually giving rise to a long GRB), and a burst proceeding from a NSt binary merger or from a giant magnetic flare a “minor burst” (i.e. giving rise to a short GRB).

Indeed, the classification after duration only (the 2s threshold) may not be sensitive enough. Some long bursts could in fact be short ones in the rest frame, after taking account of the redshift and cosmological time dilation. Even in the observer’s frame, some “long bursts” by phenomenology have been found to last less than 2s. We investigate these ultra-short major bursts below.

The case of LGRBs shorter than 2 sec: the ultra-short LGRBs

A case in point is the burst GRB 200826A at z=0.7486, with a duration of 0.5 s in the rest frame. It displayed a typical LGRB phenomenology ‒ prompt phase and afterglow with typical spectral distribution, isotropic energy of 4.7 foe (assuming a z=0.71+/-0.14 as per Rhodes et al. 2021) or 8 foe (assuming z=0.759 as per Rossi et al. 2022) not to mention an associated supernova. Moreover, GRB 200826A took place in a low-mass blue galaxy with a relatively high metallicity and a very high star formation rate (4.0 M⊙ /yr). All of this was very typical of a long burst (Rossi et al. 2022).

Other examples of major bursts with durations lower than 2s were GRB 060505 (z=0.089) and 060614 (z=0.125) both without associated SN, GRB 111005A (z=0.0133), GRB 040924 (rest frame duration 1s, with an associated SN) and GRB 090426 with spectrum and afterglow typical of LGRBs (Rossi et al. 2022). With the growth in follow-up capacity, we can expect a larger and larger share of the short GRBs to be classified as major bursts.