Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population Sampling and Data Collection

2.2. Bacterial Isolation and Identification

2.3. Antibiotics Susceptibility Testing (AST)

2.4. Molecular Analysis

2.5. Quality Control

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Sampling and Data Collection

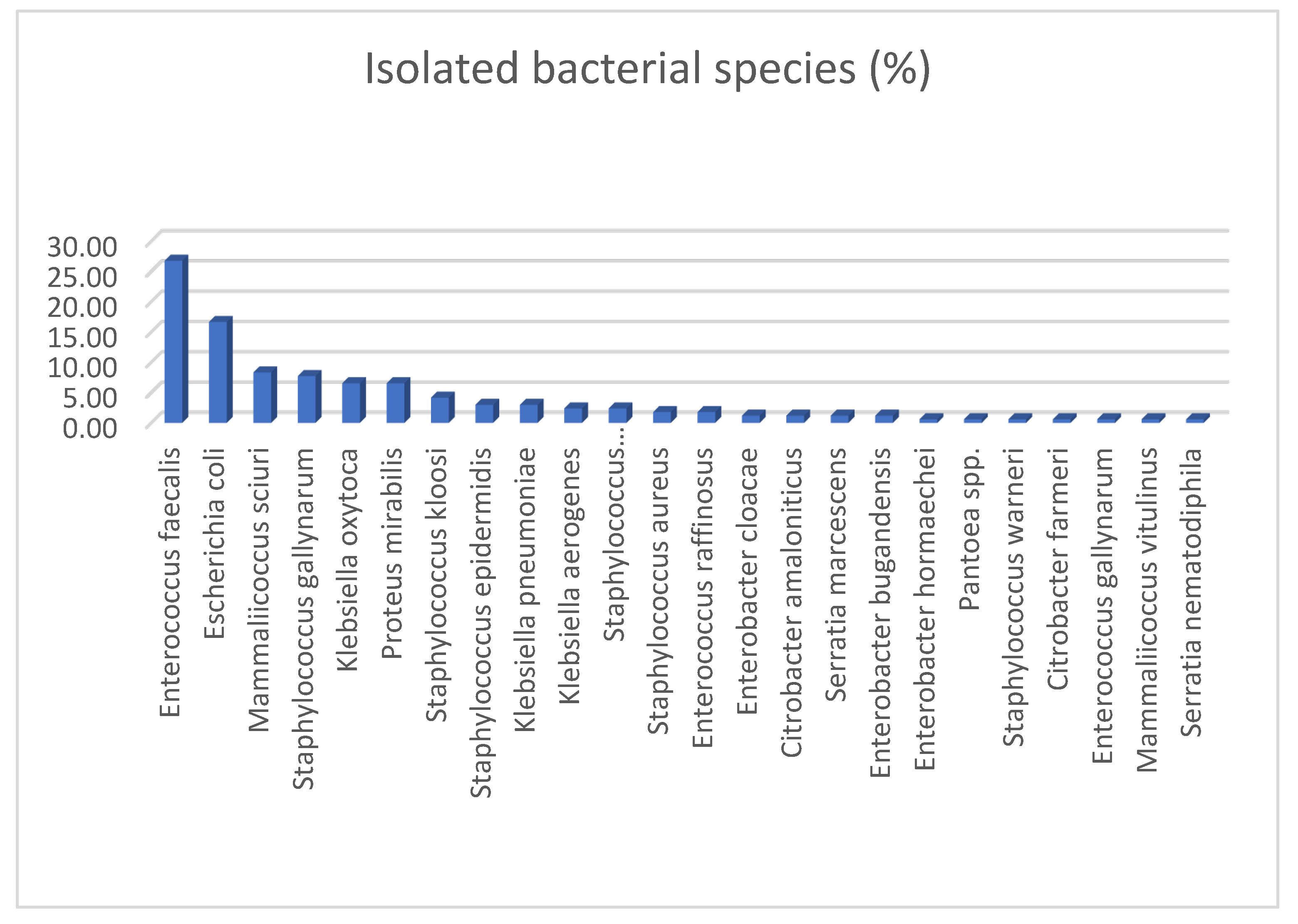

3.2. Bacterial Isolation and Identification

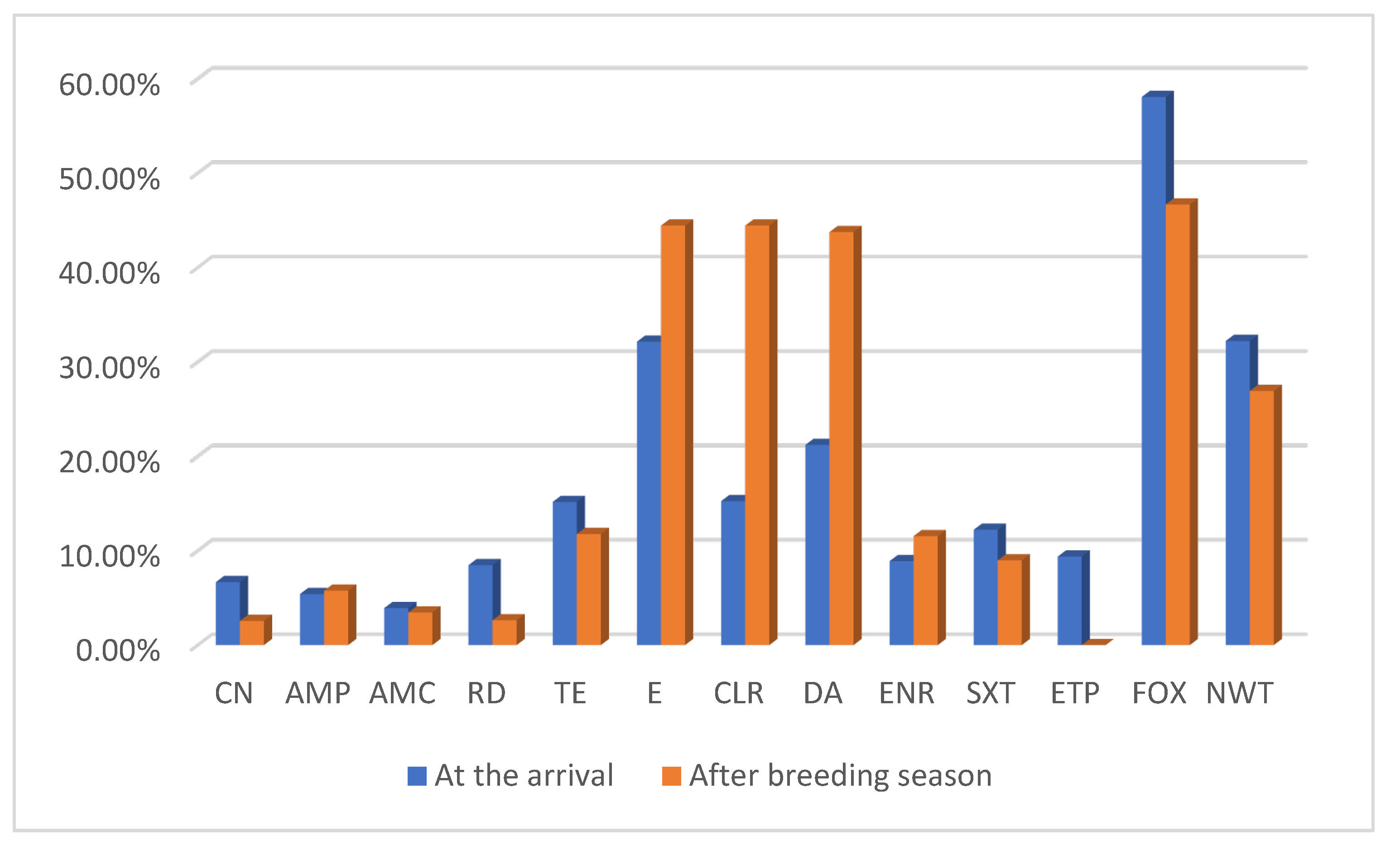

3.3. Antibiotics Susceptibility Testing (AST)

3.3.1. Comparison of NWT Proportions Across Sampling Periods and Age Classes

3.4. Molecular Analysis

3.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Matrix-assisted laser desorption–ionization time- of-flight mass spectrometry |

| WT | Wild type |

| NWT | Non-wild type |

| CN | Gentamicin |

| AMP | Ampicillin |

| AMC | Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid |

| FOX | Cefoxitin |

| RD | Rifampicin |

| DA | Clindamycin |

| TE | Tetracycline |

| E | Erythromicyn |

| CLR | Clarithromycin |

| ENR | Enrofloxacin |

| SXT | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| ETP | Ertapenem |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| AST | Antimicrobial susceptibility test |

| CoNS | Coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| MRS | Methicillin-resistant staphylococci |

| ARGs | Antimicrobial resistance genes |

References

- World Health Organization. (2023). Antimicrobial resistance. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance.

- O’Neill, J. (2016). Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: Final report and recommendations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. Wellcome Trust & HM Government. Retrieved from https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160525_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf.

- Llor, C., & Bjerrum, L. (2014). Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Therapeutic advances in drug safety, 5(6), 229–241. [CrossRef]

- Abbassi, M. S., Badi, S., Lengliz, S., Mansouri, R., Salah, H., & Hynds, P. (2022). Hiding in plain sight—Wildlife as a neglected reservoir and pathway for the spread of antimicrobial resistance: A narrative review. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 98(6), fiac045. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), World Health Organization (WHO), & World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) (Founded as OIE). (2022). One Health Joint Plan of Action 2022–2026: Working together for the health of humans, animals, plants and the environment. Rome: FAO. [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson-Palme, J., Abramova, A., Berendonk, T. U., Coelho, L. P., Forslund, S. K., Gschwind, R., Heikinheimo, A., Jarquín-Díaz, V. H., Khan, A. A., Klümper, U., Löber, U., Nekoro, M., Osińska, A. D., Ugarcina Perovic, S., Pitkänen, T., Rødland, E. K., Ruppé, E., Wasteson, Y., Wester, A. L., & Zahra, R. (2023). Towards monitoring of antimicrobial resistance in the environment: For what reasons, how to implement it, and what are the data needs?. Environment international, 178, 108089. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, E., Scarpellini, R., Celli, G., Marliani, G., Zaghini, A., Mondo, E., Rossi, G., & Piva, S. (2024). Wild birds as potential bioindicators of environmental antimicrobial resistance: A preliminary investigation. Research in veterinary science, 180, 105424. [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, L., Fioretti, A., Russo, T. P., Barco, L., Raia, P., De Luca Bossa, L. M., Sensale, M., Menna, L. F., & Dipineto, L. (2013). First report of Salmonella enterica serovar Infantis in common swifts (Apus apus). Avian Pathology, 42(4), 323–326. [CrossRef]

- Miniero, R., Carere, C., De Felip, E., Iacovella, N., Rodriguez, F., Alleva, E., & Di Domenico, A. (2008). The use of common swift (Apus apus), an aerial feeder bird, as a bioindicator of persistent organic microcontaminants. Annali dell’Istituto Superiore di Sanità, 44(2), 187–194. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18660568/.

- EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing) (2025). EUCAST disk diffusion method for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (Version 13.0). https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/eucast/pdf/disk_test_documents/2025/Manual_v_13.0_EUCAST_Disk_Test_2025.pdf.

- Fernandes, C. J., Fernandes, L. A., & Collignon, P., on behalf of the Australian Group on Antimicrobial Resistance (AGAR). (2005). Cefoxitin resistance as a surrogate marker for the detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 55(4), 506–510. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A. B., Lau, E. F., Greve, T., & Nørskov-Lauritsen, N. (2025). The EUCAST disk diffusion method for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of oral anaerobes. APMIS, 133(2), Article e70002. [CrossRef]

- EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing) (2025). EUCAST breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters (Version 15.0). https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Breakpoint_tables/v_15.0_Breakpoint_Tables.pdf.

- EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing) (2019). Definitions of S, I and R. https://www.eucast.org/newsiandr.

- EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing) (2023). Expected resistant phenotypes Version 1.2. Retrived from https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/Expert_Rules/2023/Expected_Resistant_Phenotypes_v1.2_20230113.pdf.

- Stegger, M., Andersen, P. S., Kearns, A., Pichon, B., Holmes, M. A., Edwards, G., Laurent, F., Teale, C., Skov, R., & Larsen, A. R. (2012). Rapid detection, differentiation and typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus harbouring either mecA or the new mecA homologue mecA(LGA251). Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 18(4), 395–400. [CrossRef]

- Lack, D. (1955). The food of the swift. Journal of Animal Ecology, 24(1), 120–136. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1882.

- Wayman, C., Fernández-Piñas, F., Fernández-Valeriano, R., García-Baquero, G. A., López-Márquez, I., González-González, F., Rosal, R., & González-Pleiter, M. (2024). The potential use of birds as bioindicators of suspended atmospheric microplastics and artificial fibers. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 282, 116744. [CrossRef]

- Smith, H. G., Bean, D. C., Clarke, R. H., Loyn, R., Larkins, J. A., Hassell, C., & Greenhill, A. R. (2022). Presence and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Escherichia coli, Enterococcus spp. and Salmonella sp. in 12 species of Australian shorebirds and terns. Zoonoses and Public Health, 69(6), 615–624. [CrossRef]

- Musa, L., Stefanetti, V., Casagrande Proietti, P., Grilli, G., Gobbi, M., Toppi, V., Brustenga, L., Magistrali, C. F., & Franciosini, M. P. (2023). Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Commensal E. coli Isolated from Wild Birds in Umbria (Central Italy). Animals, 13(11), 1776. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M., Silva, N., Igrejas, G., Silva, F., Sargo, R., Alegria, N., Benito, D., Gómez, P., Lozano, C., Gómez-Sanz, E., Torres, C., Caniça, M., & Poeta, P. (2014). Antimicrobial resistance determinants in Staphylococcus spp. recovered from birds of prey in Portugal. Veterinary Microbiology, 171(3-4), 436–440. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ripa, L., Gómez, P., Alonso, C. A., Camacho, M. C., Ramiro, Y., de la Puente, J., Fernández-Fernández, R., Quevedo, M. Á., Blanco, J. M., Báguena, G., Zarazaga, M., Höfle, U., & Torres, C. (2020). Frequency and characterization of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes of coagulase-negative Staphylococci from wild birds in Spain: Detection of tst-carrying S. sciuri isolates. Microorganisms, 8(9), 1317. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Maldonado, B., Rodríguez-Alcázar, P., Fernández-Novo, A., González, F., Pastor, N., López, I., Suárez, L., Moraleda, V., & Aranaz, A. (2022). Urban birds as antimicrobial resistance sentinels: White storks showed higher multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli levels than seagulls in central Spain. Animals, 12(19), 2714. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A. E., Hromádková, T., Jabir, T., Vipindas, P. V., Krishnan, K. P., Mohamed Hatha, A. A., & Briedis, M. (2022). Dissemination of multidrug resistant bacteria to the polar environment: Role of the longest migratory bird Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea). Science of the Total Environment, 815, 152727. [CrossRef]

- Colín-Castro, C. A., López-Jácome, L. E., Rodríguez-García, M. J., Garibaldi-Rojas, M., Rojas-Larios, F., Vázquez-Larios, M. del R., … Garza-González, E. (2025). The ongoing antibiotic resistance and carbapenemase-encoding genotypes surveillance: The first quarter report of the INVIFAR network for 2024. PLOS ONE, 20(4), e0319441. [CrossRef]

- Jubeh, B., Breijyeh, Z., & Karaman, R. (2020). Resistance of Gram-Positive Bacteria to Current Antibacterial Agents and Overcoming Approaches. Molecules, 25(12), 2888. [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, I.N., Juárez-Fernández, G., Höfle, U. et al. Staphylococcus aureus Carriage in the Nasotracheal Cavities of White Stork Nestlings (Ciconia ciconia) in Spain: Genetic Diversity, Resistomes and Virulence Factors. Microb Ecol 86, 1993–2002 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wellbrock, A. H. J., Bauch, C., Rozman, J., & Witte, K. (2017). ‘Same procedure as last year?’ Repeatedly tracked swifts show individual consistency in migration pattern in successive years. Journal of Avian Biology, 48(6), 797–805. [CrossRef]

- Åkesson, S., Klaassen, R., Holmgren, J., Fox, J. W., & Hedenström, A. (2012). Migration routes and strategies in a highly aerial migrant, the common swift Apus apus, revealed by light-level geolocators. PLoS ONE, 7(7), e41195. [CrossRef]

- Gulumbe, B. H., Haruna, U. A., Almazan, J., Ibrahim, I. H., Faggo, A. A., & Bazata, A. Y. (2022). Combating the menace of antimicrobial resistance in Africa: A review on stewardship, surveillance and diagnostic strategies. Biological Procedures Online, 24(1), 19. [CrossRef]

- Kimera, Z. I., Mshana, S. E., Rweyemamu, M. M., Mboera, L. E. G., & Matee, M. I. N. (2020). Antimicrobial use and resistance in food-producing animals and the environment: An African perspective. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, 9(1), 37. [CrossRef]

- Guèye, E. F. (2024). Trends and prospects of poultry value chains in Africa. Journal of Agriculture, Science and Technology, 23(4), 19–46. [CrossRef]

- Said, B., Pétermann, Y., Howlett, P., & Guidi, M. (2025). Rifampicin exposure in tuberculosis patients with comorbidities in Sub-Saharan Africa: Prioritising populations for treatment — a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 64(8), 1149–1163. [CrossRef]

- Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (AIFA). (2024). L’uso degli antibiotici in Italia. Rapporto Nazionale 2023. Roma: AIFA. https://www.aifa.gov.it/documents/20142/2766777/Rapporto_Antibiotici_2023.pdf.

- World Health Organization. (2022). The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) antibiotic book. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/365135.

- Baranauskaite-Fedorova, I., & Dvarioniene, J. (2023). Management of Macrolide Antibiotics (Erythromycin, Clarithromycin and Azithromycin) in the Environment: A Case Study of Environmental Pollution in Lithuania. Water, 15(1), 10. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ortiz, E., Blanco Gutiérrez, M. D. M., Calvo-Fernandez, C., Mencía-Gutiérrez, A., Pastor Tiburón, N., Alvarado Piqueras, A., Pablos-Tanarro, A., & Martín-Maldonado, B. (2024). Addressing challenges in wildlife rehabilitation: Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria from wounds and fractures in wild birds. Animals, 14(8), 1151. [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, Ł., Gaffke, L., Pierzynowska, K., Cyske, Z., Choszcz, M., Węgrzyn, G., & Węgrzyn, A. (2022). Enrofloxacin—the ruthless killer of eukaryotic cells or the last hope in the fight against bacterial infections? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(7), 3648. [CrossRef]

- EMA (European Medicines Agency) (2025). European sales and use of antimicrobials for veterinary medicine: Annual surveillance report for 2023. European Medicines Agency. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/european-sales-use-antimicrobials-veterinary-medicine-annual-surveillance-report-2023_en.pdf.

- Russo, T. P., Minichino, A., Gargiulo, A., Varriale, L., Borrelli, L., Pace, A., Santaniello, A., Pompameo, M., Fioretti, A., & Dipineto, L. (2022). Prevalence and phenotypic antimicrobial resistance among ESKAPE bacteria and Enterobacterales strains in wild birds. Antibiotics, 11(12), 1825. [CrossRef]

- Soh, H. Y., Tan, P. X. Y., Ng, T. T. M., Chng, H. T., & Xie, S. (2022). A Critical Review of the Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Safety Data of Antibiotics in Avian Species. Antibiotics, 11(6), 741. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Y., Chen, C. K., Chen, Y. Y., Fang, A., Shaw, G. T., Hung, C. M., & Wang, D. (2020). Maternal gut microbes shape the early-life assembly of gut microbiota in passerine chicks via nests. Microbiome, 8(1), 129. [CrossRef]

- Teyssier, A., Lens, L., Matthysen, E., & White, J. (2018). Dynamics of gut microbiota diversity during the early development of an avian host: Evidence from a cross-foster experiment. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9, 1524. [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska, B., Sysa, M., Godela, A., & Biczak, R. (2024). Antibiotics amoxicillin, ampicillin and their mixture—Impact on bacteria, fungi, ostracods and plants. Molecules, 29(18), 4301. [CrossRef]

| Antimicrobial class | Antimicrobial | Code (μg) | Bacterial order tested | ECOFFs (NWT<mm) | EUCAST clinical zone diameter breakpoints (R<mm) |

| Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin | CN (10) | Bacillales, | S. aureus (18); S. epidermidis (20) | |

| Enterobacterals | E. coli, P. mirabilis, Serratia marcescens (16); K. oxytoca, C. freundii, E. cloacae (15); K. pneumoniae, K. aerogenes (14); | ||||

| Penicillins +/- beta-lactamase inhibitors | Ampicillin | AMP (10) | Enterobacterals, | E. coli (13); P. mirabilis (19) | |

| Lactobacillales | E. faecalis (12) | ||||

| Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid | AMC (30) | Enterobacterals | E. coli (14); K. pneumoniae (22); P. mirabilis (22) | ||

| Lactobacillales | N. A. | ||||

| Cephalosporins | Cefoxitin | FOX (30) | Bacillales | - | S. aureus, CoNs (22); S. epidermidis (27) |

| Rifamycins | Rifampicin | RD (5) | Bacillales | S. aureus (24); S. epidermidis (30) | |

| Lactobacillales | N. A. | ||||

| Lincosamides | Clindamycin | DA (2) | Bacillales | S. aureus, S. epidermidis (21) | |

| Tetracyclines | Tetracycline | TE (30) | Bacillales, | S. aureus (20) | |

| Enterobacterals | E. coli (21) | ||||

| Lactobacillales | N. A. | ||||

| Macrolides | Erythromycin | E (15) | Bacillales | S. aureus (22) | |

| Clarithromycin | CLR (15) | Bacillales | N. A. | ||

| Fluoroquinolones | Enrofloxacin | ENR (5) | Bacillales, | N. A. | |

| Lactobacillales, | N. A. | ||||

| Enterobacterals | N. A. | ||||

| Sulfonamides + dihydrofolate reductase inhibitors | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | SXT (25) | Bacillales, | S. aureus (23) | |

| Lactobacillales, | E. faecalis (26) | ||||

| Enterobacterals | E. coli (22); K. oxytoca (21); K. pneumoniae (18); E. cloacae, P. mirabilis (20) | ||||

| Carbapenems | Ertapenem | ETP (10) | Enterobacterals, | E. coli (24); K. pneumoniae (22) | |

| Bacillales | N. A. |

| Gene | Sequences (5′–3′) | Product size (bp) | References |

| mecA | Fw: TCCAGATTACAACTTCACCAGG | 162 | Stegger et al. (2012) |

| Rev: CCACTTCATATCTTGTAACG | |||

| mecC | Fw: AAAAAAAGGCTTAGAACGCCTC | 138 | Stegger et al. (2012) |

| Rev: GAAGATCTTTTCCGTTTTCAGC |

| Grouped swifts | Tot isolates (n) | Enterobacterales (n); (%) | Bacillales (n); (%) | Lactobacillales (n); (%) |

| TOTAL | 168 | 71; (42.26%) | 48; (28.57%) | 49; (29.17%) |

| AT THE ARRIVAL | 90 | 31; (34.44%) | 33; (36.67%) | 26; (28.89%) |

| AFTER BREEDING SEASON | 78 | 40; (51.28%) | 15; (19.23%) | 23; (29.49%) |

| Adults at the arrival | Adults after breeding season | Juveniles | |

| CN | 3.33% (1/30) | 0% (0/13) | 5.60% (7/125) |

| AMP | 0% (0/24) | 0% (0/10) | 4.85% (5/103) |

| AMC | 0% (0/29) | 0% (0/13) | 3.45% (4/116) |

| RD | 5.26% (1/19) | 0% (0/7) | 5.63% (4/71) |

| TE | 16.67% (5/30) | 15.38% (2/13) | 13.51% (15/111) |

| E | 22.22% (2/9) | 20% (2/10) | 31.60% (12.38) |

| CLR | 22.22% (2/9) | 20% (2/10) | 34.21% (13/38) |

| DA | 22.22% (2/9) | 20% (2/10) | 26.31% (10/38) |

| ENR | 10% (3/30) | 23.08% (3/13) | 9.91% (11/111) |

| SXT | 3.33% (1/30) | 15.38% (2/13) | 9.91% (11/111) |

| ETP | 0% (0/20) | 0% (0/10) | 8% (6/75) |

| FOX | 44.44% (4/9) | 50% (2/4) | 54.29% (19/35) |

| NWT | 33.33% (10/30) | 38.46% (5/13) | 28.8% (36/125) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).