1. Introduction

1.1. The Concept of Homeostatic Control of Food Intake

The term homeostasis was coined by Cannon in 1929 as a refinement of Bernard’s 1878 notion of the constancy of the internal environment, as reviewed by Geary [

1]. Homeostatic control of nutrient intake that purportedly drives food choices to ensure nutrient needs are met, is implied as an aspect of several partially overlapping concepts that can be found in the literature: ‘Self-selection’ and ‘Nutrient-specific hungers’ [

2], ‘Nutritional wisdom’ [

3], ‘Intuitive eating’ [

4], ‘Energy balancing’ [

5], ‘Nutrient balancing’ [

6,

7], ‘Nutritional intelligence’ [

8] and weight and adiposity regulation [

9]. Whilst these concepts differ as to which variables are homeostatically regulated and how homeostasis is achieved, they have in common the notion of negative-feedback control, with a more or less flexible reference level for the regulated variable. They also all recognize that cooperation between behavior and metabolic regulation is fundamental to homeostasis of nutrient status. In a different context, the ability of early humans to recognize (develop a preference for) novel sources of nutritious food and incorporate them into their food culture (cuisine) may partly explain their survival during periods of pre-history where all other hominin species became extinct [

10].

1.2. Models and Mechanisms of Homeostatic Influences on Energy and Macronutrient Intake

Regarding intake of energy and of protein, a degree of negative-feedback control (intake being affected by current status vis a vis requirement) is generally accepted [

11,

12,

13]. For example, on a timescale of months or longer, increased energy requirements, caused, for example, by pregnancy or very high physical activity, are accompanied by a corresponding increased appetite and food intake, which typically reverses when the requirement is reduced. Extensive research suggests that appetite is modulated by a complex network of physiological, psychological, social and environmental factors that influence the motivation to initiate an eating event (meal frequency), terminate an eating event (meal size) and food choice [

14,

15]. However, most research in this area focuses on understanding the energy imbalance that can lead to obesity [

16], and in that context, a person’s appetite on a given occasion cannot be predicted from a simple homeostatic model [

5,

17].

1.3. Is micronutrient Intake Affected by Micronutrient Requirements?

The 2000 Institute of Medicine report on Dietary Reference Intakes [

11] stated that in contrast to energy, intakes of non-energy yielding nutrients (micronutrients) are independent of the corresponding requirements (no homeostatic control). Despite substantial refinements in the understanding of appetite control since then (reviewed by Carreiro et al. [

18] and Watts et al. [

15]), it appears that no subsequent publications have directly and quantitatively addressed this apparent distinction between macro- and micronutrients. Only two reviews (Berthoud et al. [

19] and Geary [

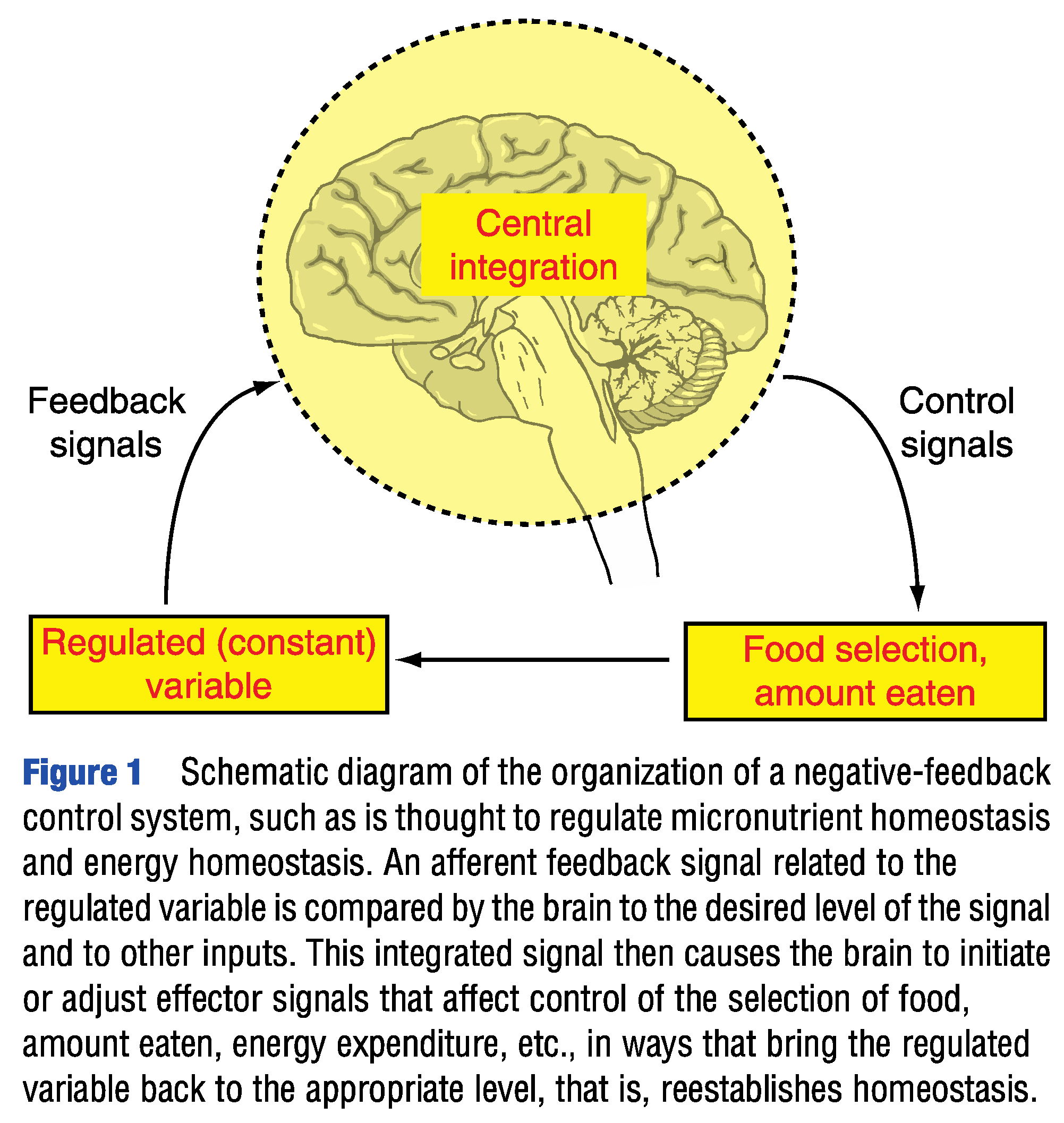

20]) have presented the homeostatic control of energy and micronutrients in humans as conceptually identical. (

Figure 1).

Detailed animal studies have demonstrated homeostatic control of sodium status, including control of water and salt intake [

21], and similar negative-feedback control of intake has been reported for protein [

22], calcium [

23] and vitamin C [

24]. Data from observational studies are consistent with the idea that negative feedback control also affects human food choices, in contexts where this is not simply implementation of dietary advice. For example, Brunstrom and Schatzker [

25] used food pictures to show that combinations of food choices that improve overall nutritional balance were preferred; increased intake of salt in Addisons’s disease [

2] was associated with increased sensitivity to the taste of salt [

26]. However, it does not appear that any quantitative experimental investigations explicitly addressing feedback-regulated control of micronutrient intake (other than sodium) in humans have been published since before World War II.

The aim of this article is to present the hypothesis that negative-feedback regulation of micronutrient status may have important effects on human food choice, at least in certain situations, with potentially wide-ranging consequences, to briefly review historic and recent relevant research and to outline some potential tests of this hypothesis.

Definitions (in the present context of micronutrient homeostasis)

Homeostasis: Maintenance of an appropriate level of available nutrient in the blood or tissues where this nutrient is needed.

Control: A mechanism that contributes to regulation of an outcome (e.g. nutrient status) by modulation of a process (e.g. food preference) which affects this outcome.

Requirement: The amount of a nutrient needed to meet demands for normal physiological processes, including ‘losses’ due to utilization, limited bioavailability, replenishment of storage depots etc.

Nutrient status: The amount of a nutrient presently available in the tissues or circulation. (A regulated variable for all those nutrients that are subject to homeostasis).

Intake: The amount ingested of a nutrient or a food per unit time. (Hypothesized to be a controlled variable for many nutrients).

Appeal: The perceived intrinsic pleasantness of a food. (The control of nutrient intake is hypothesized to involve changes in the relative appeal of nutrient-rich and nutrient-poor foods).

Preference: That one food is selected in greater quantity and/or frequency than another, when both are equally available. Preference is positively associated with appeal, everything else being equal.

Appetite: The desire to eat, resulting in intake. Appetite is positively associated with appeal, everything else being equal.

Negative-feedback regulation: That information about changes in an outcome (such as nutrient status) is used to control a process (such as nutrient intake) to change in the direction that supports maintenance of a reference level of this outcome (homeostasis).

2. Previous Concepts and Research, Historic Context

Soon after vitamins and minerals were discovered to be essential nutrients early in the 20

th century, researchers started to investigate whether animals [

2,

27] and human infants [

28] are able to select diets that provide sufficient intake of all the studied micronutrients and how such selection might operate. Different approaches focused on either physiologically determined innately recognized ‘specific hungers’ [

2] as for sugar or sodium, or how learned associations between food flavors and micronutrient content might shape adequate nutritional choices [

27]. However, the hypotheses tested in rat models often contrasted with practical observations and concerns in animal husbandry, such as farm animals consuming unhealthy amounts of concentrate feeds if given the opportunity [

29]. Subsequently, priorities for experimentation with humans changed, along with improved ethical standards [

30] and ‘variety seeking’ (reduced preference for any recently consumed food) became considered the primary mechanism to ensure ingestion of a good balance of nutrients [

31]. The observed inconsistencies between different experimental designs and concepts were interpreted as teleological biases undermining the entire concept of homeostatic nutrient intake control [

32], and the paucity of data linking individual micronutrient requirements to intake in humans was interpreted as an absence of effect [

11].

The research on macronutrient intake control has passed through stages with increasingly complex models. Initially (until around 2000), the main emphasis was on physiological aspects of feedback regulation. As the obesity epidemic gained pace, research on factors affecting voluntary food intake increasingly focused on understanding how some people become obese or under-nourished [

18]. Regarding micronutrients, later literature reviews on human food choice rarely mentioned earlier concepts (e.g.[

33]) regarding the possibility that micronutrient status might affect food intake preferences [

34,

35]. This also applied to reviews focused on food choice in the evolutionary context [

36], on balancing nutrient intake with nutrient requirements [

7] or on human ability and preference to select foods with optimal nutrient composition [

8]. Two recent reviews [

37,

38] explicitly stated that humans have not evolved homeostatic feedback mechanisms to control micronutrient intake, even though no data or other evidence for this absence were specified in these reviews. In contrast, three books describe how a connection between micronutrient requirements and intake in animals could be relevant for human nutrition [

39,

40,

41]. For example, one of them explained how mixing vitamins into pig rations caused the pigs to consume less vegetation [

42] and suggested that human food fortification may have a similar effect on vegetable intake [

41]. However, these books do not seem to have influenced current thinking in the nutrition research community. No research intended to assess the presence or absence of moderate (i.e., ecologically relevant) associations between an individual’s requirements and their intake of micronutrients is apparent in the literature (although it must be acknowledged that the lack of methods for determining nutrient requirements of individuals precludes testing this directly). It appears as if an absence of data caused a lack of awareness, resulting in relevant data not being collected, further eroding awareness and so on.

Interestingly, already during the earliest studies on diet choice in animals, some factors causing apparent inconsistencies were identified and explained. By 1933, Harris and colleagues had identified ways to ‘deceive’ rats into unhealthy choices and vitamin deficiencies [

27], e.g. by presenting them with too many choices, or by unpredictably changing the flavor-nutrient associations among the food options. Such observations do not necessarily (as previously claimed by Galef [

32]) invalidate the hypothesis that micronutrient intake is affected by requirements. On the contrary, by demonstrating some limits to regulation, they may be particularly significant in today’s varied and inconsistent ‘foodscape’ [

40], including the conundrum of how multiple-ingredient (ultra-processed) foods may affect human health [

43].

3. Proposed Concept and Model

3.1. Core Elements of Concept

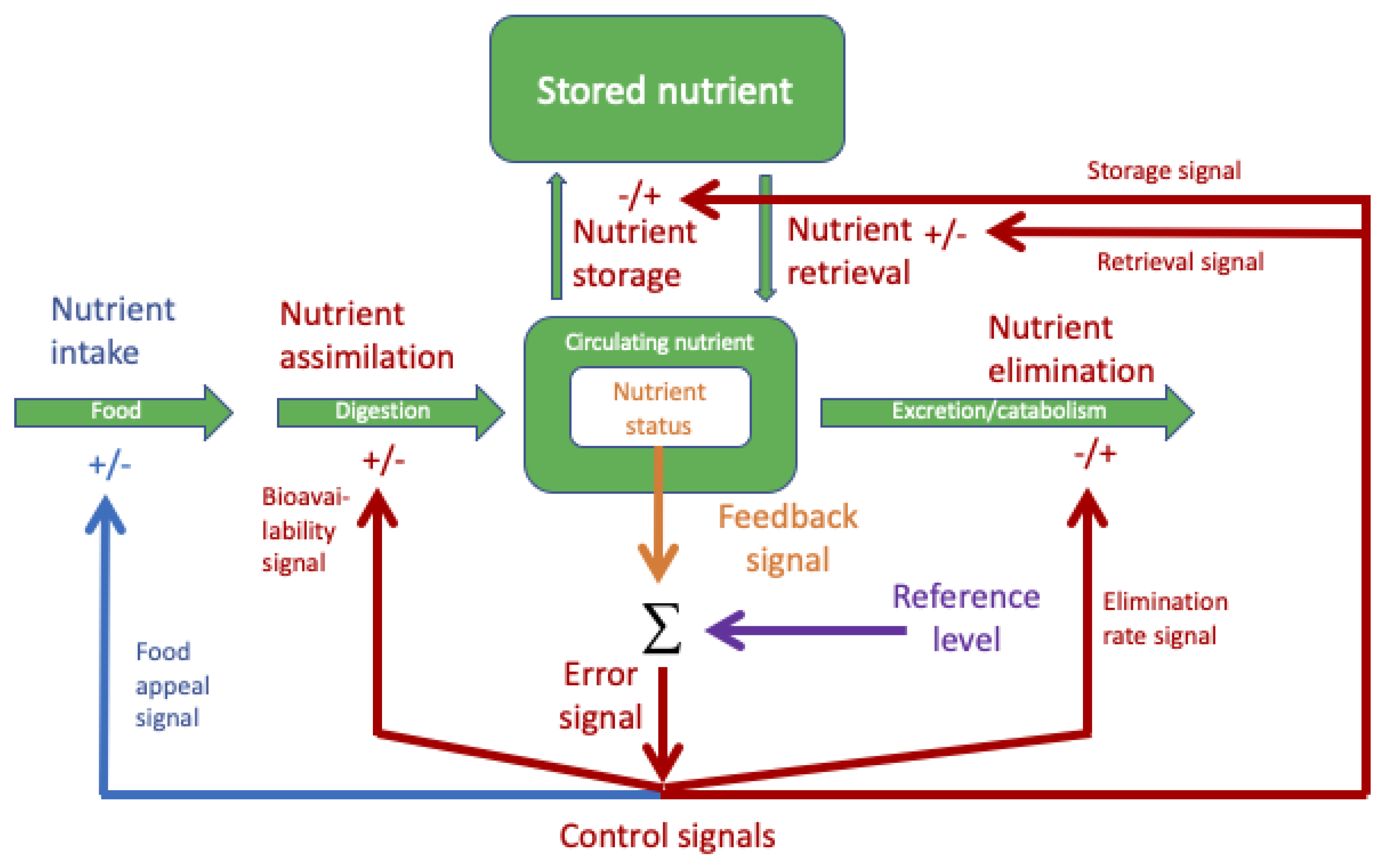

To summarize the discussion above, enhanced preference for nutrient-rich foods in response to insufficient supply of the corresponding nutrient in the overall diet is a key prerequisite for feedback control to increase intake (see

Figure 2). While the present paper focuses on micronutrients, the concept described below is not specific to any given nutrient. Indeed, it is compatible with several published (macro-)nutrient intake control models, such as energy balancing [

5], nutritional geometry [

6], body weight and adiposity regulation [

9], sodium homeostasis [

21] and the framework of feeding behavior [

44].

The figure depicts both increases and decreases in the ‘Food appeal signal’. In the former case, low nutrient status leads to increased preference for and intake of nutrient-containing foods, as has been found for several micro- and macronutrients in animal studies [

22,

24]. In the latter case, excessively high nutrient status leads to decreased preference for foods containing this nutrient, as has been observed for sodium and protein [

21,

45], and indicated by excessively high micronutrient content in meals occurring significantly less frequently than random chance [

25].

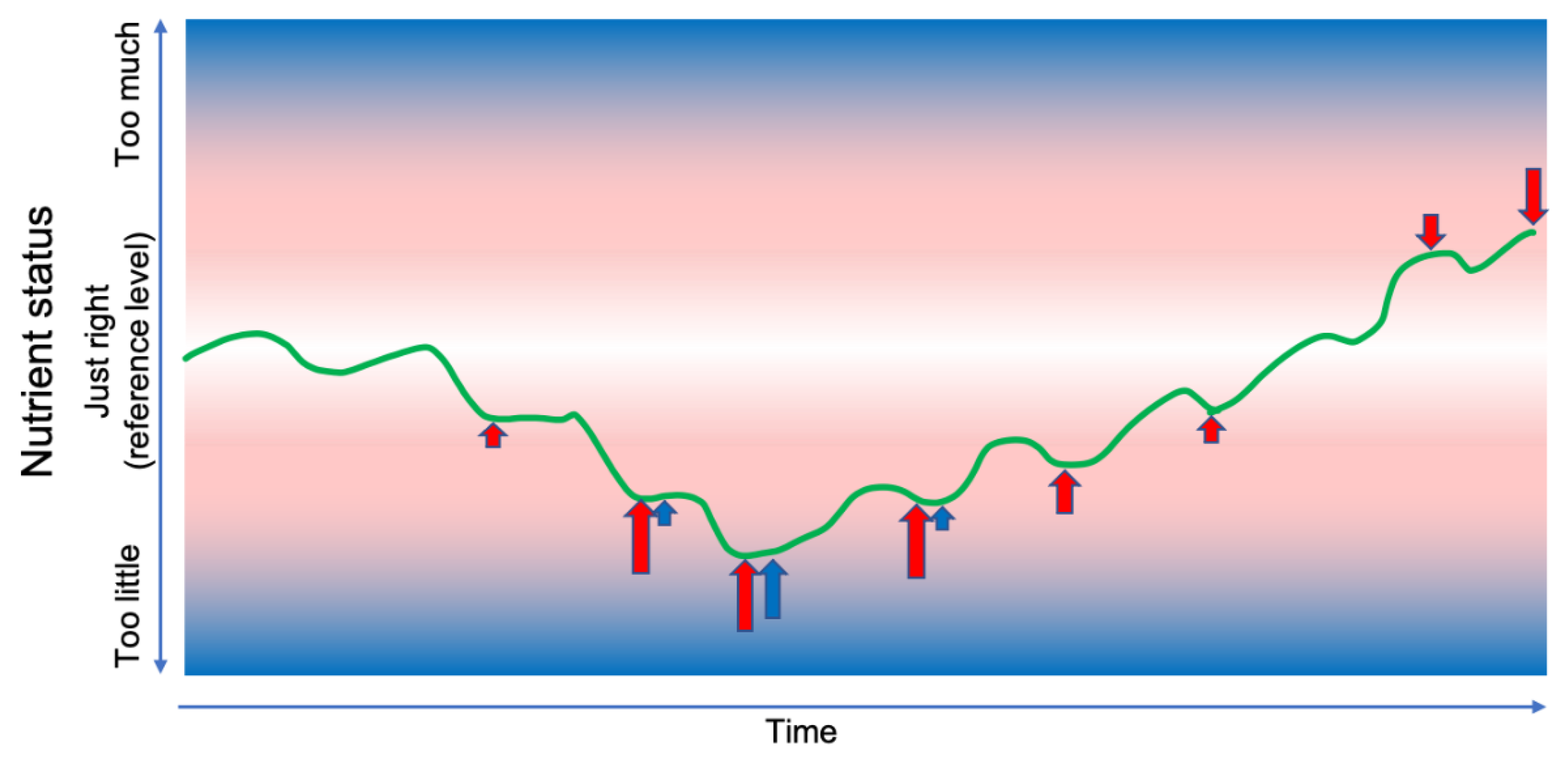

Several internal homeostatic mechanisms, including changes in bioavailability, storage and excretion) fine-tune the effective nutrient status (i.e., concentrations in tissues or blood). Due to these internal controls, behavioral feedback control of intake may operate only intermittently, requiring a larger threshold of deviation from the reference level than the internal mechanisms (see

Figure 3), and behavioral controls may involve substantial lag and hysteresis. Finally, it is likely that not all the negative-feedback controls shown exist for every micronutrient.

3.2. Possible Mechanisms for Intake Control

For such a scheme to operate, a mechanism must exist to distinguish between rich and poor sources of the regulated nutrient. While some nutrients, such as sugar, sodium, glutamate [

46] and possibly calcium [

47] correspond with specific taste receptors, the sense of taste is far from sufficiently accurate to directly sense even macronutrient composition directly [

48], and most micronutrients have no known specific taste receptor. However, animal experiments have clearly demonstrated a second option, ‘flavor-nutrient learning’ for micronutrients, to develop a heightened appeal of a characteristic flavor of a food that contains a needed micronutrient [

49]. This is an ability that humans may share. For example, experimentally imposed low or high protein intake affected subsequent protein intake and preference for savory flavors in women [

45], even though the results of efforts to assess flavor-nutrient learning for energy-yielding macronutrients in humans have been inconsistent in other human studies [

50,

51]. A third potential route could be through modulation of the non-nutrient-specific ‘variety seeking’ [

31], where a low nutrient status could enhance the propensity for consumption of unfamiliar foods in general and thus increase the opportunity to alleviate an insufficient supply of a nutrient in the habitual diet. Overall food deprivation in mice affects specific neurons that increase the motivation to seek food, even in the presence of a predator [

52]. While this study addressed total food intake rather than a specific nutrient, Yuan et al. [

53] reported that deficiency in any one of 8 essential amino acids activated the same neuronal pathway to increase explorative behavior in stressed mice, although these authors interpreted this as an ‘antidepressant effect’ of leucine deprivation (illustrating the lack of awareness suggested above).

These three mechanisms (taste sensing, flavor-nutrient learning and modulation of variety seeking) are not mutually exclusive, but may all operate together in the control of the same nutrient.

However, paraphrasing a paper by Forbes and Kyriazakis [

54]: if food appeal in humans is affected by negative-feedback regulation, why don't we always choose wisely? There are several potential answers to this question:

If the content of a nutrient in the habitual diet is sufficiently high and stable to allow the status of this nutrient to stay within the internally regulated zone (red background in

Figure 3), then this nutrient may not affect food preferences/intake at all – this may apply to most nutrients in most diets.

If the content of a nutrient in the habitual diet is variable, for example changes with seasons of the year, then food rich in this nutrient will become more preferred during nutrient-depleted periods than during periods of plenty. The magnitude of this effect, and how quickly it appears once sub-optimal levels occur, will depend on the capacity for storage, which varies with the nutrient.

If an individual has never previously experienced borderline deficiency (the lower blue band in

Figure 3) of a nutrient, then if it does occur, they will not immediately be able to adjust their intake; they first must learn which foods counteract the nutrient imbalance. If such foods are not encountered at this stage, the imbalance may persist and cause harm.

After having experienced one or more episodes of nutrient imbalance, and learned how to counteract it, presumably the response to future episodes will be faster and more targeted – as found for farm animals [

54].

Note that some animal studies indicate that nutrient-related preferences may manifest as aversion to nutrient-poor foods [

55], even in the absence of a nutrient-rich preferred alternative (in which case it is indistinguishable from loss of appetite). This may also apply to humans; it is possible that such reduced preference for a nutritionally inadequate habitual diet is experienced as increased variety seeking.

4. Proposed Research and Implications

4.1. Testing the Hypothesis - Is Micronutrient Intake Affected by Requirement?

Ethical considerations limit what nutrient manipulations are acceptable in future human studies; however, some options are still possible. The response to repeated intake of a distinctive food providing micronutrients to individuals at risk of deficiency could be recorded without ethical concerns, particularly if combined with objective measures of nutritional status. However, this would not be expected to show any effect in populations where deficiency problems are rare. Studies focusing on food appeal and behavior without changing the participants’ diets (as in the study by Brunstrom & Schatzker [

25]) are not ethically problematic, and could involve volunteers who experience predictable and quantifiable changes in their requirements, such as pregnancy, lactation, blood donation or surgery. Some pathologies such as celiac disease are associated with micronutrient deficiencies [

56], which are resolved after treatment, so changes in selected food appeal before and after treatment could detect changes associated with improved nutritional status. Observational studies could support or contradict the hypothesis, but are not sufficient to demonstrate causality, due to the risk of unrecognized confounding factors. Potentially, for certain micronutrients Mendelian randomization designs could be used. These use genetic variants related to micronutrient sufficiency (i.e. those involved in the metabolism of specific micronutrients) as exposure variables and investigate the putatively causal effect of this on micronutrient intake as the outcome. Intriguingly, an early study with data on MTHFR(C677T) genotypes and on intake of methionine and B-vitamins in 1492 people [

57] found 10% higher intake of vitamin B2 (a co-factor for the MTHFR enzyme) in 124 people with TT genotype (with lower enzyme activity) compared with those with CC or CT genotypes. While this small sample did not yield sufficient statistical power to detect significance, the larger datasets available today could be analyzed to find out if this trend is reproducible. Another approach could be to identify genetic loci associated with intake of specific micronutrients, and therefore likely to have a role in their regulation, as it has recently been done for macronutrients [

58].

Another experimental option is to reduce the requirement, as in a randomized placebo-controlled trial (RPCT) of micronutrient supplementation. Some relevant data may already exist, from published studies that (for any reason) combined a micronutrient RPCT with assessment of habitual dietary intake, and could be analyzed for effects of supplementation on intake [

59]. For example, our hypothesis predicts that supplementation with vitamin C will reduce the intake of vitamin C-rich foods such as vegetables and fruits, by preventing this micronutrient from being the most limiting nutrient [

54]. As explained above and discussed in other reviews [

8,

44] the effects should not be expected to be large or rapid, particularly in populations with high food security. Therefore, researchers should initially be encouraged to carry out pilot studies with a variety of designs to estimate the sample sizes required to test this hypothesis.

4.2. Consequences if This Concept has Significant Effect on Food Choices

4.2.1. Regarding Populations at Risk of Micronutrient Deficiencies

As detailed on pages 212-224 in the Institute of Medicine’s [

11] consensus report, if micronutrient intakes are in fact correlated with their requirements (individual nutritional status), then the established methods for estimating nutrient deficiency at the population level will give incorrect (too high) estimates. In other words, micronutrient malnutrition may be less widespread than expected. In this case, micronutrient provision to vulnerable populations could be made more efficient (target the individuals in greatest need) by being distributed in a food (e.g. a gum or a cookie) with a distinctive taste, rather than as tablets or injections. Individuals at risk of deficiency should then theoretically develop a preference for the taste and come back for more, while those at risk of excessive intake (page 123 in [

11]) may discover that they do not like it.

4.2.2. Regarding Addition of Micronutrients to Food in General

If human homeostatic intake control works in the same ways as in laboratory animals, then it may also be ‘confused/deceived’ by the same factors, specifically unpredictable contents of micronutrients and/or excessive variety of flavors [

27]. If this is the case, then the control of micronutrient intake may be less accurate for humans in a modern society with thousands of foods to choose from, not to mention the existence of fortified foods and nutritional supplements, compared with a population consuming a traditional diet composed of far fewer, easily identifiable and nutritionally distinct ingredients. There are no indications that modern diets (as defined above) cause more micronutrient deficiencies than traditional diets. However, even a small change in food choice preferences could have substantial health consequences in the long run, if it systematically reduces the relative intake of foods with high micronutrient density, such as vegetables, fish and whole-grain cereals, since these are exactly the foods that are associated with good health [

60,

61]. Micronutrient-dense foods are also major dietary sources of non-essential dietary constituents such as fiber, phytochemicals [

62] and nitrate [

63], which were present in excess of optimal intake in ancient and pre-human diets, and therefore presumably were not subject to natural selection for feedback control of low intake. While people who consume micronutrient supplements are obviously not at risk of deficiency in the supplemented nutrients, feedback regulation could lead to reduced intake of such other important dietary constituents, which may be at least as important for the differential effect of a healthy diet as the essential micronutrients themselves [

64,

65].

If future research confirms such a relation, then this should be taken into account when evaluating the risk/benefit balance of non-targeted fortification or supplementation with micronutrients.

4.3. Conclusion and Recommendations

Homeostatic negative-feedback control of micronutrient intake may affect human dietary habits. If it does, this would be sufficiently important for public health that it is worthwhile to investigate. Researchers are recommended to consider negative-feedback regulation of micronutrient status as a possibility to take into account, whenever planning or analyzing research that involves changes in micronutrient intake (whether depletion or supplementation), in humans or animals. Specifically, food intake information should routinely be collected both during and after such interventions, to allow testing for corresponding effects on the habitual diet.

The text continues here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.A., C.A. and K.B.; Methodology, K.B., N.G., J.M.B. and P.J.R.; Supervision, C.A. and K.B.; Visualization, N.G., A.M., K.B., J.M.B. and P.J.R.; Writing - original draft, W.A., C.A., and K.B.; Writing - review & editing, W.A., C.A., N.G., A.M., J.M.B., P.J.R., R.M., H.-R.B., F.P., G.L., M.S., S.L., A.H. and K.B.

Funding

The writing of this paper received no external funding dedicated to this topic. However, Tabuk University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, funded a PhD scholarship to Wahebah Alanazi, and funded the APR to support her general scientific development.

Acknowledgments

Mona Albalawi. Melissa Bateson, Iain Brownlee, Adam Drewnowski, Joanna Dwyer, Gunnar Cedersund, James McCutcheon, Ilias Kyriazakis, Mohammed Salman, Jonathan Sholl, Gavin Stewart, Inge Tetens and Renger Witkamp are gratefully acknowledged for helpful inspiration, discussions and/or critically reviewing and commenting on a draft of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The following authors declare financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Mark Schatzker authored two popular science books on this general topic, in 2015 and 2021, for which he is eligible to receive royalties. Fred Provenza authored a popular science book on this general topic, in 2018, for which he is eligible to receive royalties. All other authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The funder had no role in the design of the present review; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of information from the literatre; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviation is used in this manuscript:

| RPCT |

Randomized placebo-controlled trial |

References

- Geary, N. Energy homeostasis from Lavoisier to control theory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 2023, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, C. Total self regulatory functions in animals and human beings. Harvey Lecture Series 1943, 38, 63–103. Available online: https://www.ssib.org/web/classic3.php.

- Albrecht, W. Discriminations in Food Selection by Animals. The Scientific Monthly 1945, 60, 347–352. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/18318.

- Tylka, T. Development and psychometric evaluation of a measure of intuitive eating. Journal of Counseling Psychology 2006, 53, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P.; Brunstrom, J. Appetite and energy balancing. Physiology & Behavior 2016, 164, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubenheimer, D.; Senior, A.M.; Mirth, C.; Cui, Z.; Hou, R.; Le Couteur, D.G.; Solon-Biet, S.M.; Léopold, P.; Simpson, S.J. An integrative approach to dietary balance across the life course. Iscience 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholl, J. Everything in moderation or moderating everything? Nutrient balancing in the context of evolution and cancer metabolism. Biology & Philosophy 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunstrom, J.M.; Flynn, A.N.; Rogers, P.J.; Zhai, Y.J.; Schatzker, M. Human nutritional intelligence underestimated? Exposing sensitivities to food composition in everyday dietary decisions. Physiology & Behavior 2023, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speakman, J.R.; Hall, K.D. Models of body weight and fatness regulation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2023, 378, 20220231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.; Stewart, B. Defining the 'generalist specialist' niche for Pleistocene Homo sapiens. Nature Human Behaviour 2018, 2, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: Applications in Dietary Assessment; The National Academies Press.: Washington, DC, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, C.; Reed, S.; Henagan, T. Homeostatic regulation of protein intake: in search of a mechanism. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2012, 302, R917–R928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raubenheimer, D.; Simpson, S. Protein Leverage: Theoretical Foundations and Ten Points of Clarification. Obesity 2019, 27, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, M.; Beaulieu, K.; Gibbons, C.; Halford, J.C.G.; Blundell, J.; Stubbs, J.; Finlayson, G. The Control of Food Intake in Humans. In Endotext [Internet]; Feingold, K., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M., Eds.; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth (MA), 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278931/.

- Watts, A.G.; Kanoski, S.E.; Sanchez-Watts, G.; Langhans, W. The physiological control of eating: signals, neurons, and networks. Physiol Rev 2022, 102, 689–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, R.; Horgan, G.; Robinson, E.; Hopkins, M.; Dakin, C.; Finlayson, G. Diet composition and energy intake in humans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 2023, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, E.; Mattes, R.D. Interindividual variability in appetitive sensations and relationships between appetitive sensations and energy intake. Int J Obes (Lond) 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreiro, A.; Dhillon, J.; Gordon, S.; Higgins, K.; Jacobs, A.; McArthur, B.; Redan, B.; Rivera, R.; Schmidt, L.; Mattes, R.; et al. The Macronutrients, Appetite, and Energy Intake. Annual Review of Nutrition 2016, 36, 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthoud, H.R.; Münzberg, H.; Richards, B.K.; Morrison, C.D. Neural and metabolic regulation of macronutrient intake and selection. Proc Nutr Soc 2012, 71, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, N. Appetite. In Encyclopedia of Human Behaviour (Second edition); Ramachandran, V.S., Ramachandran, V., Eds.; Elsevier, 2012; pp. 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, A.; Zafra, M.; Simón, M.; Mahía, J. Sodium Homeostasis, a Balance Necessary for Life. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Peters, K.; Denton, B.; Lee, K.; Chadchankar, H.; McCutcheon, J. Restriction of dietary protein leads to conditioned protein preference and elevated palatability of protein-containing food in rats. Physiology & Behavior 2018, 184, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tordoff, M.G. Calcium: taste, intake, and appetite. Physiol Rev 2001, 81, 1567–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuo, T.; Nakamura, F.; Suwabe, T.; Sako, N. Vitamin C deficiency in osteogenic disorder Shionogi/Shi Jcl-od/od rats: effects on sour taste preferences, lick rates, chorda tympani nerve responses, and taste transduction elements. Chemical Senses 2023, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunstrom, M.J.; Schatzker, M. Micronutrients and food choice: A case of 'nutritional wisdom' in humans? Appetite 2022, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosowicz, J.; Pruszewicz, A. The "taste" test in adrenal insufficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1967, 27, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, L.; Clay, J.; Hargreaves, F.; Ward, A. Appetite and Choice of Diet. The Ability of the Vitamin B Deficient Rat to Discriminate between Diets Containing and Lacking the Vitamin. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character 1933, 113, 161–190. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/81776. [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.M. Results of the self-selection of diets by young children. Can Med Assoc J 1939, 41, 257–261. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC537465/. [PubMed]

- Tribe, D. The Behaviour of the Grazing Animal: A Critical Review of Present Knowledge. Grass and Forage Science 1950, 5, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed on 13 January).

- Rolls, B.J.; Rowe, E.A.; Rolls, E.T.; Kingston, B.; Megson, A.; Gunary, R. Variety in a meal enhances food intake in man. Physiol Behav 1981, 26, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galef, B.G. A Contrarian View of the Wisdom of the Body as it Relates to Dietary Self-Selection. Psychological Review 1991, 98, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P.; Vollmecke, T.A. Food Likes and Dislikes. Annual Review of Nutrition 1986, 6, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual Models of Food Choice: Influential Factors Related to Foods, Individual Differences, and Society. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, G.; Adan, R.; Belot, M.; Brunstrom, J.; de Graaf, K.; Dickson, S.; Hare, T.; Maier, S.; Menzies, J.; Preissl, H.; et al. The determinants of food choice. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2017, 76, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulijaszek, S.J. Human eating behaviour in an evolutionary ecological context. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2002, 61, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytekin, N.; Godfri, B.; Cunliffe, A. 'The hunger trap hypothesis': New horizons in understanding the control of food intake. Medical Hypotheses 2019, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, P.J.; Field, M.S.; Andermann, M.L.; Bailey, R.L.; Batterham, R.L.; Cauffman, E.; Frühbeck, G.; Iversen, P.O.; Starke-Reed, P.; Sternson, S.M.; et al. Neurobiology of eating behavior, nutrition, and health. J Intern Med 2023, 294, 582–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenza, F.D. Nourishment: what animals can teach us about rediscovering our nutritional wisdom; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, Vermont, 2018; p. 404 pages. ISBN 978-1603588027. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzker, M. The Dorito Effect. The Surprising New Truth About Food and Flavor; Simon & Schuster: New York, 2015; p. 262. ISBN 978-1-5011-1613-1. [Google Scholar]

- Schatzker, M. The End of Craving. Recovering the Lost Wisdom of Eating Well; Avid Reader Press: New York, 2021; ISBN 978-1-5011-9247-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, H.; Terrill, S.; Jensen, A.; Becker, D.; Norton, H. Comparison of free-choice and complete rations for growing-finishing pigs on pasture and drylot. 1957, 16, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valicente, V.M.; Peng, C.H.; Pacheco, K.N.; Lin, L.T.; Kielb, E.I.; Dawoodani, E.; Abdollahi, A.; Mattes, R.D. Ultraprocessed Foods and Obesity Risk: A Critical Review of Reported Mechanisms. Advances in Nutrition 2023, 14, 718–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriazakis, I.; Tolkamp, B.; Emmans, G. Diet selection and animal state: an integrative framework. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 1999, 58, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffioen-Roose, S.; Smeets, P.; van den Heuvel, E.; Boesveldt, S.; Finlayson, G.; de Graaf, C. Human protein status modulates brain reward responses to food cues. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2014, 100, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Issanchou, S. Nutrient sensing: What can we learn from different tastes about the nutrient contents in today's foods? Food Quality and Preference 2019, 71, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordoff, M.G.; Alarcón, L.K.; Valmeki, S.; Jiang, P.H. T1R3: A human calcium taste receptor. Scientific Reports 2012, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattes, R.D. Taste, teleology and macronutrient intake. Current Opinion in Physiology 2021, 19, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanoel, D.E.; Thomas, D.T.; Blache, D.; Milton, J.T.; Wilmot, M.G.; Revell, D.K.; Norman, H.C. Sheep deficient in vitamin E preferentially select for a feed with a higher concentration of vitamin E. Animal 2016, 10, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeomans, M.R. The Role of Learning in Development of Food Preferences. In The Psychology of Food Choice; Shepherd, R., Raats, M., Eds.; CABI: London, 2006; pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans, M.R. Flavour-nutrient learning in humans: An elusive phenomenon? Physiology & Behavior 2012, 106, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo Salgado, I.; Li, C.; Burnett, C.J.; Rodriguez Gonzalez, S.; Becker, J.J.; Horvath, A.; Earnest, T.; Kravitz, A.V.; Krashes, M.J. Toggling between food-seeking and self-preservation behaviors via hypothalamic response networks. Neuron 2023, 111, 2899–2917.e2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Wu, S.; Zhou, Z.; Jiao, F.; Yin, H.; Niu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Chen, S.; Guo, F. Leucine deprivation results in antidepressant effects via GCN2 in AgRP neurons. Life Metabolism 2023, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, J.M.; Kyriazakis, I. Food preferences in farm animals: why don't they always choose wisely? Proc Nutr Soc 1995, 54, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozin, P. Specific aversions as a component of specific hungers. J Comp Physiol Psychol 1967, 64, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledsoe, A.C.; King, K.S.; Larson, J.J.; Snyder, M.; Absah, I.; Choung, R.S.; Murray, J.A. Micronutrient Deficiencies Are Common in Contemporary Celiac Disease Despite Lack of Overt Malabsorption Symptoms. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2019, 94, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husemoen, L.L.N.; Toft, U.; Fenger, M.; Jorgensen, T.; Johansen, N.; Linneberg, A. The association between atopy and factors influencing folate metabolism: is low folate status causally related to the development of atopy? International Journal of Epidemiology 2006, 35, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, J.; Dashti, H.; Sarnowski, C.; Lane, J.; Todorov, P.; Udler, M.; Song, Y.; Wang, H.; Kim, J.; Tucker, C.; et al. Genetic analysis of dietary intake identifies new loci and functional links with metabolic traits. Nature Human Behaviour 2022, 6, 155–+. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, W.; Stewart, G.; Brandt, K.; Allen, C. The Impact of Specific Micronutrients (Vitamin C, Magnesium, Zinc, Iodine, or Selenium Supplementation) on Dietary Intake of these Micronutrients in Randomised Placebo-Controlled (RCT) Human Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. 2023. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023487123.

- Fransen, H.P.; Beulens, J.W.J.; May, A.M.; Struijk, E.A.; Boer, J.M.A.; de Wit, G.A.; Onland-Moret, N.C.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; Bueno-De-Mesquita, H.B.; Hoekstra, J.; et al. Dietary patterns in relation to quality-adjusted life years in the EPIC-NL cohort. Preventive Medicine 2015, 77, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, J.; Hart, A.; Owen, H.; Zeilmaker, M.; Bokkers, B.; Thorgilsson, B.; Gunnlaugsdottir, H. Fish, contaminants and human health: Quantifying and weighing benefits and risks. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 54, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A.; Dwyer, J.; King, J.C.; Weaver, C.M. A proposed nutrient density score that includes food groups and nutrients to better align with dietary guidance. Nutrition Reviews 2019, 77, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.Z.; Blekkenhorst, L.C.; Bondonno, N.P.; Sim, M.; Woodman, R.J.; Croft, K.D.; Lewis, J.R.; Hodgson, J.M.; Bondonno, C.P. A food composition database for assessing nitrate intake from plant-based foods. Food Chemistry 2022, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A.; Gomez-Carneros, C. Bitter taste, phytonutrients, and the consumer: a review. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000, 72, 1424–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WCRF/AICR. Wholegrains, vegetables and fruit and the risk of cancer. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018; World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research, 2018; Available at dietandcancerreport.org. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).