Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

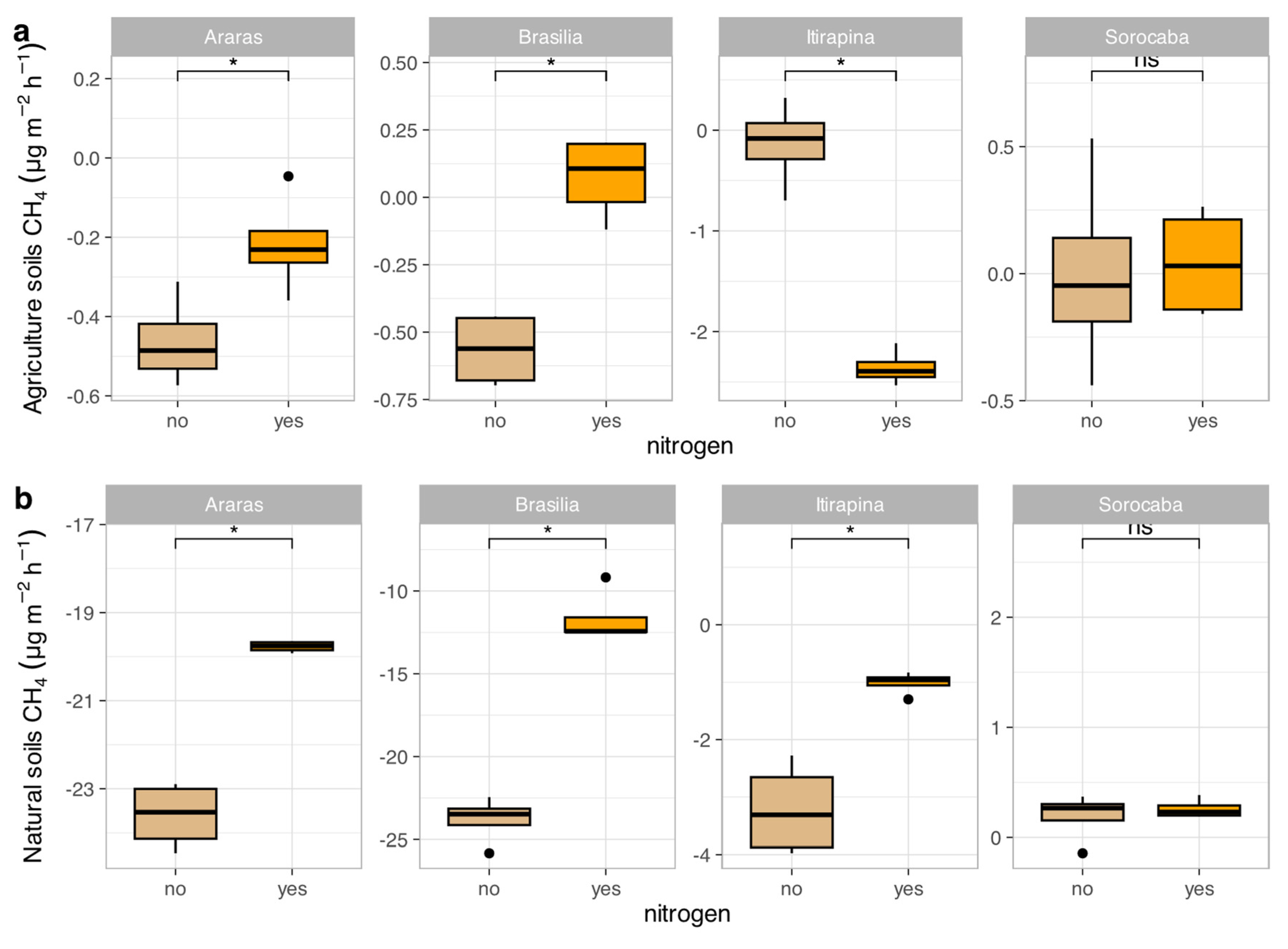

2.1. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Methane (CH₄) Fluxes

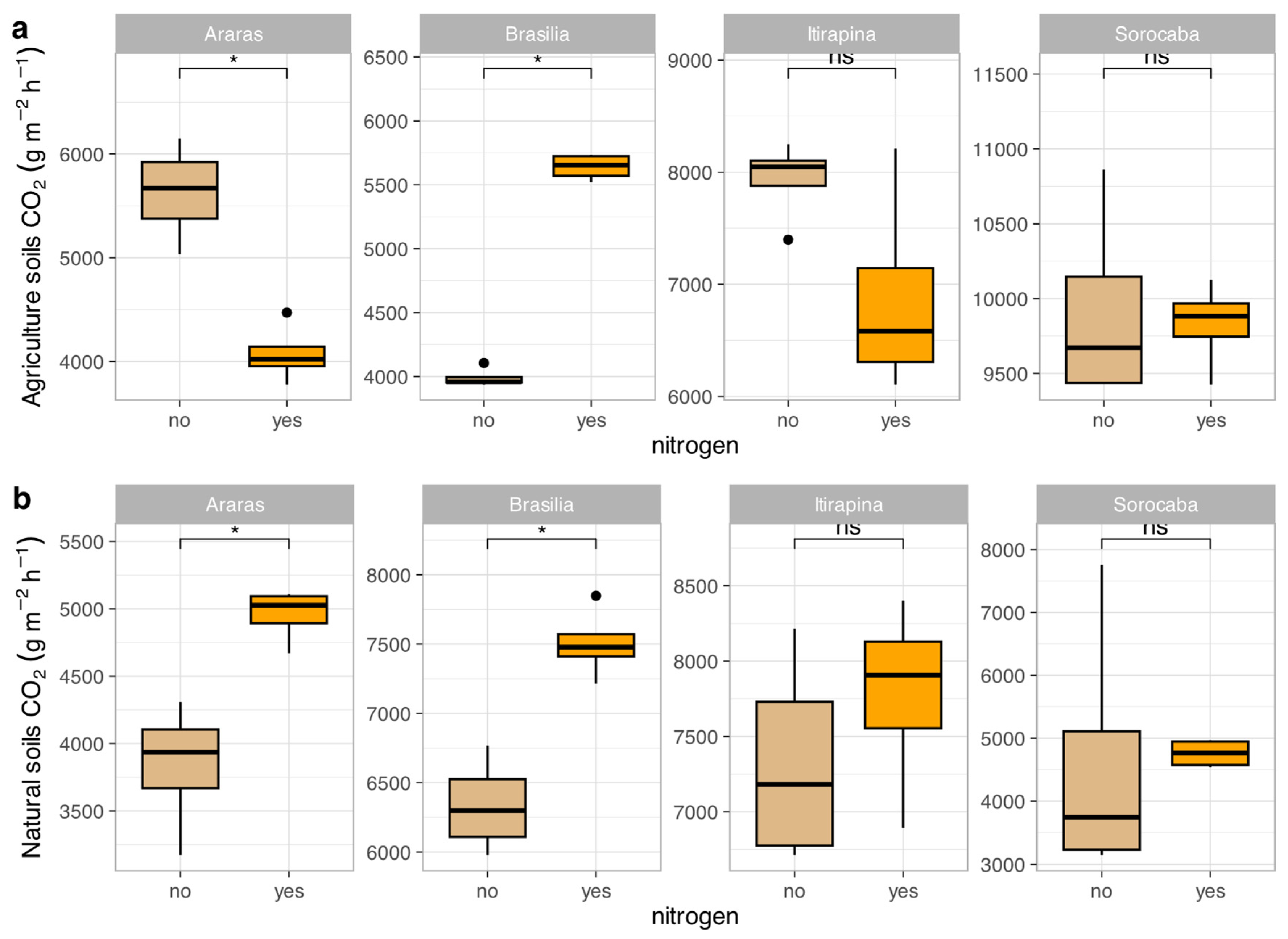

2.2. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) Fluxes

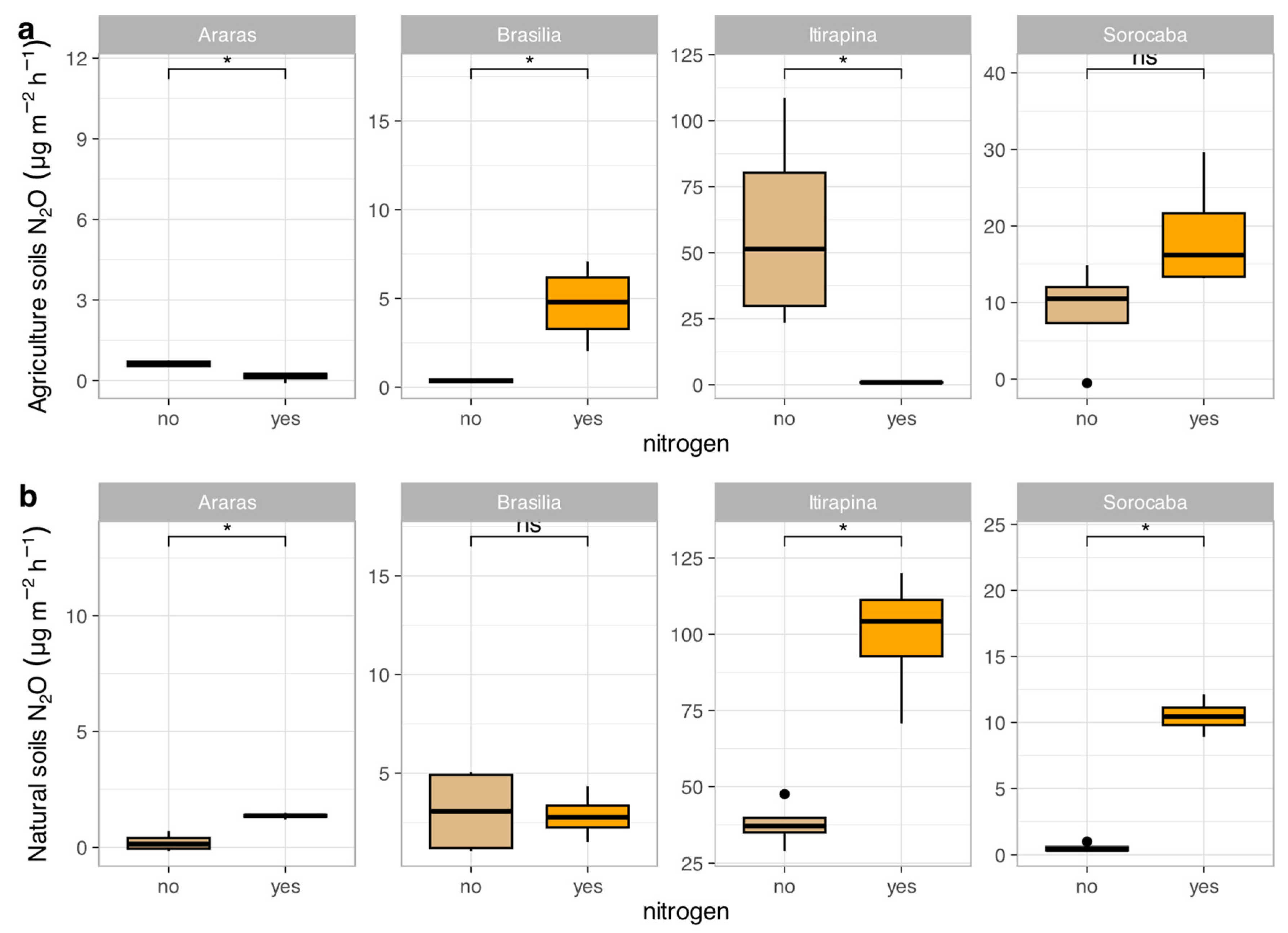

2.3. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Nitrous Oxide (N₂O) Fluxes

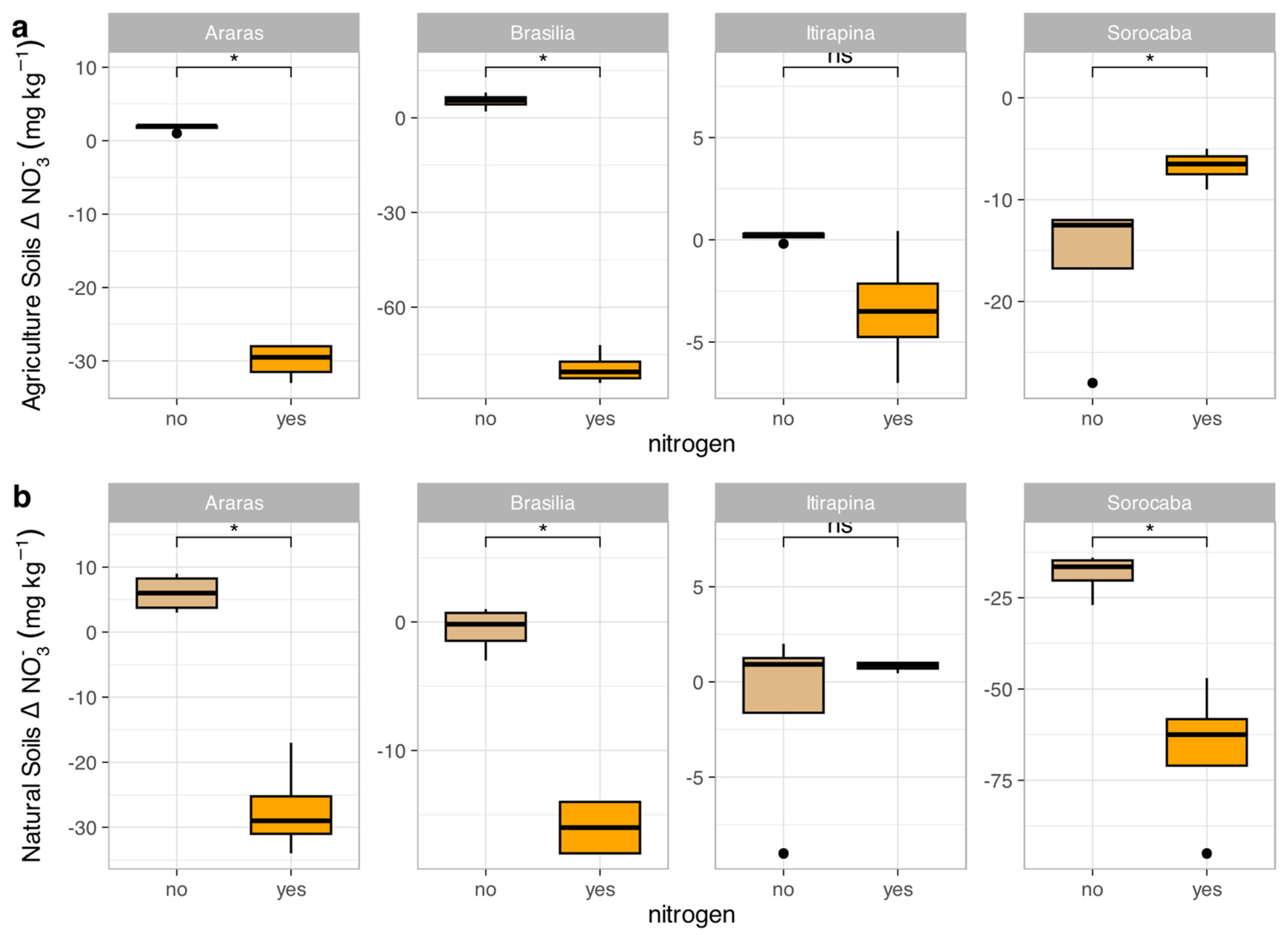

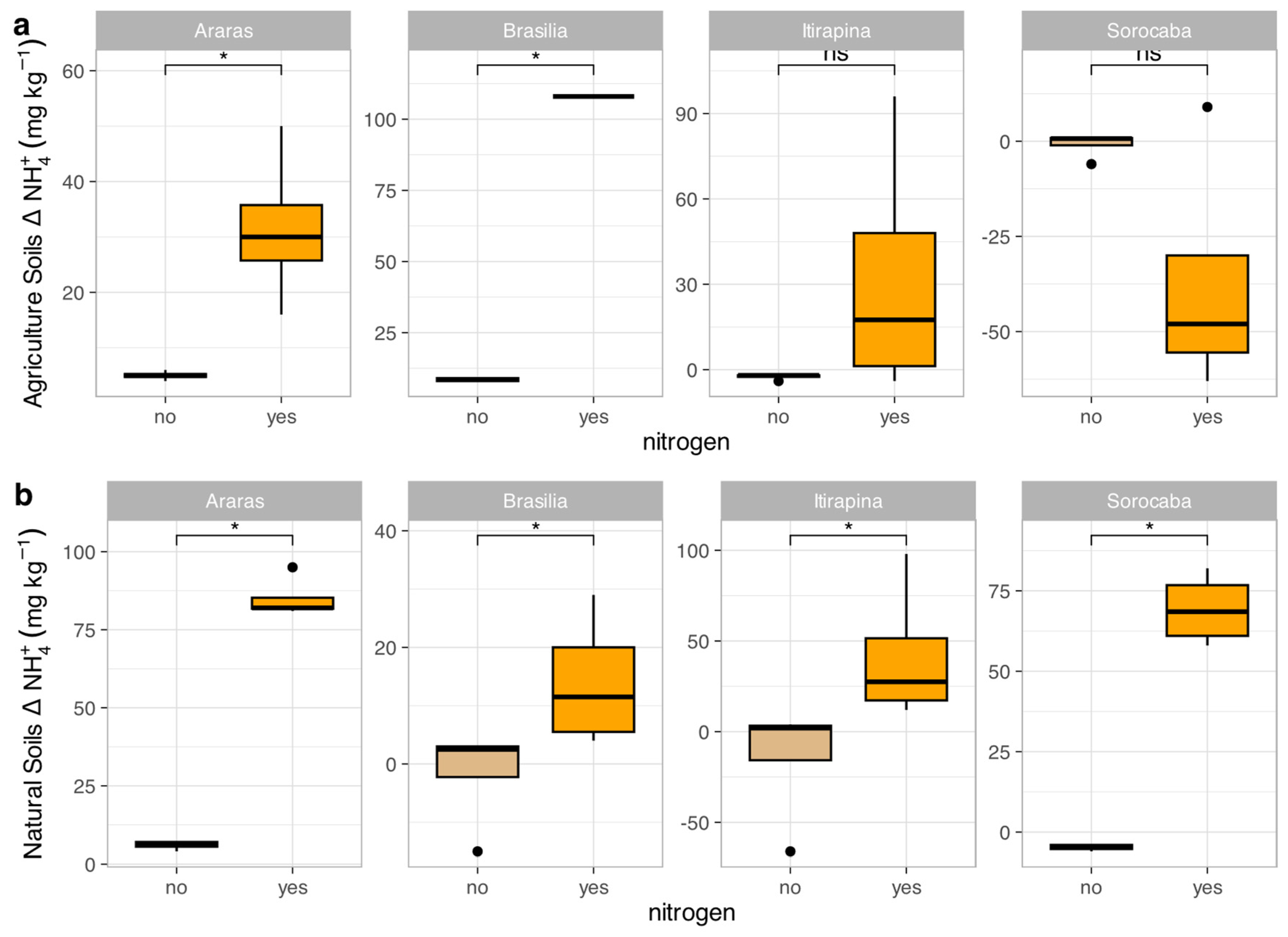

2.4. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Nitrate and Ammonium Consumption

3. Discussion

3.1. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Methane (CH₄) Fluxes

3.2. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) Fluxes

3.3. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Nitrous Oxide (N₂O) Fluxes

3.4. Effect of Ammonium Sulfate Addition on Nitrate and Ammonium Consumption

3.5. Innovative Perspective: Precision Agriculture in the Cerrado

4. Materials and Methods

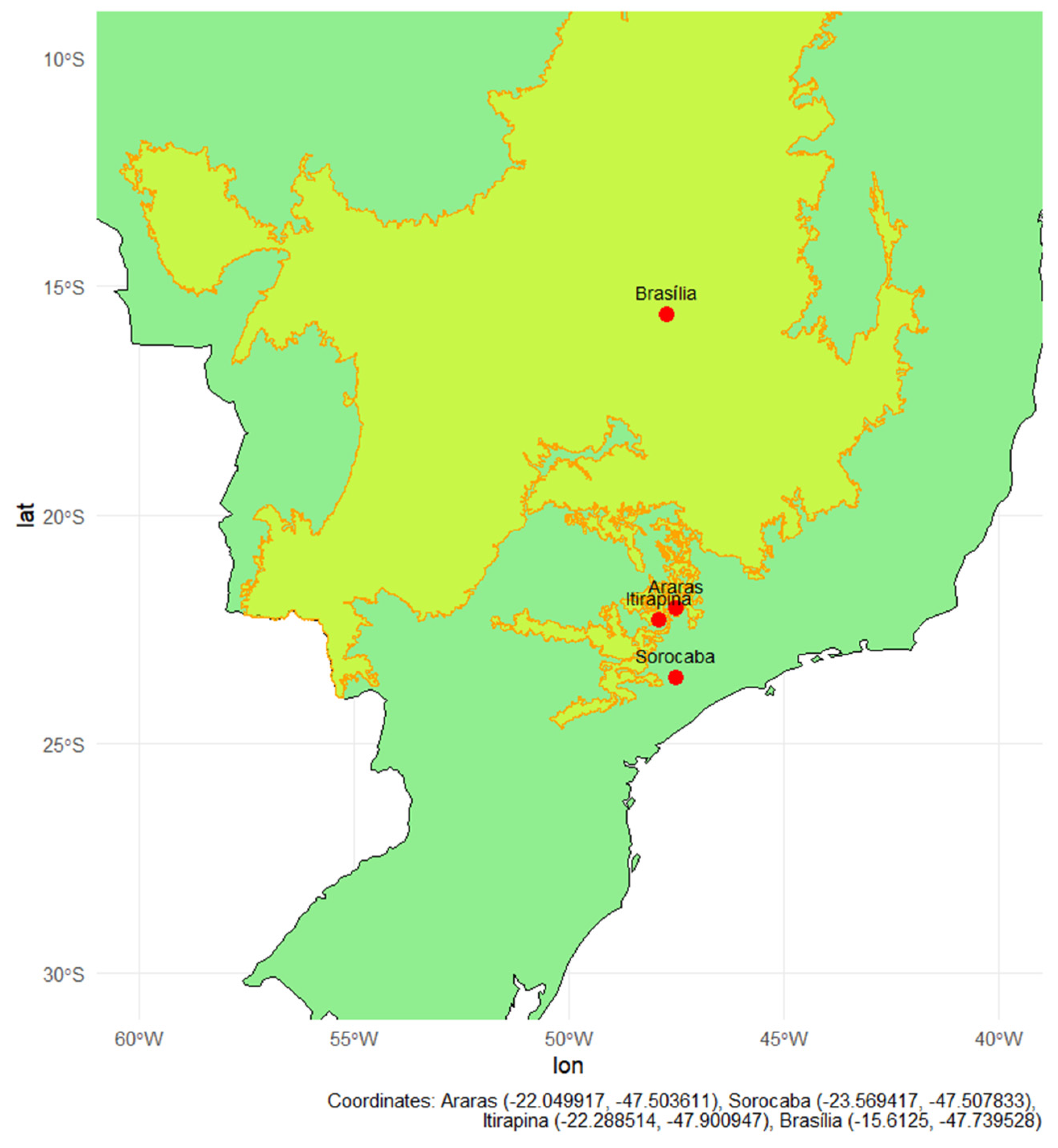

4.1. Experimental Design

4.2. Soil Sampling and Processing

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| CH₄ | Methane |

| CO₂ | Carbon Dioxide |

| N₂O | Nitrous Oxide |

| NH₄⁺ | Ammonium |

| NO₃⁻ | Nitrate |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| FAPESP | São Paulo Research Foundation |

| CAPES | Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel |

| CNPq | National Council for Scientific and Technological Development |

| AOB | Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria |

| AOA | Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaea |

| MMO | Methane Monooxygenase |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

References

- Lopes, A. S.; Guimarães Guilherme, L. R. A career perspective on soil management in the Cerrado region of Brazil. Adv. Agron. 2016, 137, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, E. E.; Rodrigues, A. A.; Martins, E. S.; Bettiol, G. M.; Bustamante, M. M. C.; Bezerra, A. S.; Bolfe, E. L. Cerrado ecoregions: A spatial framework to assess and prioritize Brazilian savanna environmental diversity for conservation. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 818–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, A. F. D.; Rodrigues, R. D. A. R.; Silveira, J. G. D.; Silva, J. J. N. D.; Daniel, V. D. C.; Segatto, E. R. Nitrous oxide emissions from a tropical Oxisol under monocultures and an integrated system in the Southern Amazon–Brazil. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2020, 44, e0190123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.; Simões, S. J.; Dalla Nora, E. L.; de Sousa-Neto, E. R.; Forti, M. C.; Ometto, J. P. H. Agricultural expansion in the Brazilian Cerrado: Increased soil and nutrient losses and decreased agricultural productivity. Land 2019, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Ciência; Tecnologia e Inovação [MCTI. Nota metodológica: Desagregação das estimativas de emissões e remoções do inventário nacional de gases de efeito estufa por unidade federativa (1990 a 2022) . Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação, Brasília. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mcti (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Gomes, L. C.; Bianchi, F. J. J. A.; Cardoso, I. M.; Fernandes, R. B. A.; Filho, E. I. F.; Schulte, R. P. O. Agroforestry systems can mitigate greenhouse gas emissions in the Brazilian Cerrado. Agrofor. Syst. 2019, 93, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishisaka, C. S.; Youngerman, C.; Meredith, L. K.; do Carmo, J. B.; Navarrete, A. A. Differences in N₂O fluxes and denitrification gene abundance in the wet and dry seasons through soil and plant residue characteristics of tropical tree crops. Front. Environ. Sci. 2019, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira Neto, M.; Piccolo, M. D. C.; Costa Junior, C.; Cerri, C. C.; Bernoux, M. Emissão de gases do efeito estufa em diferentes usos da terra no bioma Cerrado. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2011, 35, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodelier, P. L. E.; Pérez, G.; Veraart, A. J.; Krause, S. Methanotroph ecology, environmental distribution and functioning. In Methanotrophs: Microbiology fundamentals and biotechnological applications;Microbiology Monographs; Lee, E. Y., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Vol. 32, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodelier, P. L. E.; Laanbroek, H. J. Nitrogen as a regulatory factor of methane oxidation in soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 47, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo, J. B.; Sousa Neto, E. R.; Duarte-Neto, P. J.; Ometto, J. P. H. B.; Martinelli, L. A. Conversion of the coastal Atlantic forest to pasture: Consequences for the nitrogen cycle and soil greenhouse gas emissions. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 148, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, K. R. Soil methane oxidation and land-use change: From process to mitigation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 80, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S. J.; Sherlock, R. R.; Kelliher, F. M.; McSeveny, T. M.; Tate, K. R.; Condron, L. M. Pristine New Zealand forest soil is a strong methane sink. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2004, 10, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escanhoela, A. S. B.; Pitombo, L. M.; Brandani, C. B.; Navarrete, A. A.; Bento, C. B.; do Carmo, J. B. Organic management increases soil nitrogen but not carbon content in a tropical citrus orchard with pronounced N₂O emissions. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 234, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitombo, L. M.; Cantarella, H.; Packer, A. P. C.; Ramos, J. C.; Carmo, J. B. Straw preservation reduced total N₂O emissions from a sugarcane field. Soil Use Manag. 2017, 33, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hütsch, B. W. Tillage and land use effects on methane oxidation rates and their vertical profiles in soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1998, 27, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, B. C.; Smith, K. A.; Klemedtsson, L.; Brumme, R.; Sitaula, B. K.; Hansen, S.; Priemé, A.; MacDonald, J.; Horgan, G. W. The influence of soil gas transport properties on methane oxidation in soil. J. Environ. Qual. 1997, 26, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodelier, P. L. E.; Laanbroek, H. J. Nitrogen as a regulatory factor of methane oxidation in soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 47, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hawwary, A.; Brenzinger, K.; Lee, H. J.; Dannenmann, M.; Ho, A. Greenhouse gas (CO₂, CH₄, and N₂O) emissions after abandonment of agriculture. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2022, 58, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, E.; Cerri, C. E. P.; Cherubin, M. R.; Maia, S. M. F. Greenhouse gas emissions and carbon stock in agricultural soils of the Cerrado biome under different management systems. Soil Use Manag. 2021, 37, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, J. M. Nitrification in agricultural soils. In Nitrogen in agricultural systems; Schepers, J. S., Raun, W. R., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 2008; pp. 173–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, C. A.; Wakelin, S. A.; Tillman, R. W. Nitrogen cycling in grazed pastures at elevated CO₂: N₂O emissions and soil N dynamics. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst 2022, 122, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, C.; Liu, L.; Hu, S.; Compton, J. E.; Greaver, T. L.; Li, Q. Soil nitrogen cycling following repeated nitrogen fertilizer application in a tropical wet forest. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2018, 32, 1230–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leininger, S.; Urich, T.; Schloter, M.; Schwark, L.; Qi, J.; Nicol, G. W.; Prosser, J. I.; Schuster, S. C.; Schleper, C. Archaea predominate among ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in soils. Nature 2006, 442, 806–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Raij, B.; Andrade, J. C.; Cantarella, H.; Quaggio, J. A. Análise química para avaliação da fertilidade de solos tropicais; Instituto Agronômico: Campinas, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, R. J.; Edberg, J. C.; Stucki, J. W. Determination of nitrate in soil extracts by dual-wavelength ultraviolet spectrophotometry. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1985, 49, 1182–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krom, M. D. Spectrophotometric determination of ammonia: A study of a modified Berthelot reaction using salicylate and dichloroisocyanurate. Analyst 1980, 105, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitombo, L. M.; Ramos, J. C.; Quevedo, H. D.; do Carmo, K. P.; Paiva, J. M. F.; Pereira, E. A.; do Carmo, J. B. Methodology for soil respirometric assays: Step by step and guidelines to measure fluxes of trace gases using microcosms. MethodsX 2018, 5, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M. A.; Banfield, M.; Sanaullah, M.; Van Zwieten, L.; Carminati, A. Root Exudates Induce Soil Macroaggregation Facilitated by Fungi in Subsoil. Front. Environ. Sci. 2018, 6, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/.

| Site | Land Use | CH4 (µg kg soil-1day-1) |

CO2 ( g kg soil-1day-1) |

N2O ( µg kg soil-1day-1) |

pH |

NH4 + (mg/kg) |

NO3- (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Araras | Native | -23,7 ± 0,5 | 4287,08±1951,41 | 0,42 ± 1,40 | 6,1 | 7,5 | 24,6 |

| Sugar Cane | 0,4 ± 0,2 | 7473,04±4180,79 | 0,70 ± 1,79 | 4,7 | 5,5 | 2,7 | |

| Sorocaba | Native | 0,2 ± 0,1 | 4547,27±2580,50 | 2,68 ± 17,12 | 6,4 | 1,0 | 49,9 |

| Citrus | 0,3 ± 0,1 | 11010,61±5245,86 | 12,92 ± 50,46 | 5,0 | 1,4 | 9,2 | |

| Brasília | Native | -24,0 ±0,8 | 6358,41± 1478,54 | 2,18 ± 5,49 | 4,2 | 8,0 | 6,6 |

| Mayze/Soybeans | -0,7 ±0,1 | 4084,12± 1013,36 | 0,37 ± 0,38 | 5,0 | 8,8 | 21,7 | |

| Itirapina | Native | -3,4 ± 0,6 | 7428,24± 2490,61 | 55,01 ± 51,27 | 3,9 | 6,4 | 1,7 |

| Sugar Cane | -0,2 ± 0,3 | 8178,47±3613,80 | 41,32 ± 80,62 | 5,3 | 1,9 | 1,0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).