1. Introduction

In the digital era, data served as the foundation for technological advancement, influencing a wide range of applications from business analytics to artificial intelligence. The surge in personal data—including health, financial, and geolocation records—created vast potential for innovation, provided that such data could be securely and selectively shared. Sharing health information, for example, significantly enhanced patient care, prevented fraud, and supported public health initiatives.

Traditional cloud-based platforms, while offering convenience, often failed to guarantee robust data protection, as evidenced by major breaches and misuse cases. High-profile incidents such as the 2014 iCloud breach, the 2018 Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandal, and Instagram’s 2019 data leak raised serious concerns about the reliability and accountability of centralized data storage services. As a result, individuals and organizations grew increasingly hesitant to trust cloud providers with sensitive information.

In response to these growing concerns, regulatory bodies implemented frameworks like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to reinforce user privacy and data ownership rights. Nevertheless, enforcement alone proved insufficient. Technological innovations were needed to complement regulatory efforts and ensure end-to-end data security.

Blockchain technology, with its decentralized and immutable architecture, presented a promising alternative. It eliminated the need for a central authority and enhanced trust through transparent, tamper-resistant ledgers. Despite its advantages, integrating privacy into blockchain-based data sharing remained challenging. Existing systems either compromised data availability or relied on centralized key management mechanisms, which reintroduced single points of failure.

To overcome these issues, this paper introduced BlockShare, a decentralized data sharing platform that ensured fine-grained, privacy-preserving access using blockchain. By integrating zero-knowledge proofs and an authenticated data structure, BlockShare empowered users with verifiable and secure control over their data without sacrificing privacy.

2. Related Work

Advancements in privacy-preserving systems, blockchain technology, and machine learning methodologies were evident in the works of Patel, Kabra[

1], Malipeddi, Talwar[

2], and Recharla[

3]. Blockchain technology, highlighted by platforms like Polkadot [

4] and Corda [

5], emerged as a tool for applications requiring high data integrity and transparency. Zhang et al. [

6] developed frameworks leveraging zero-knowledge proofs for smart contracts, echoing Akshar Patel’s[

7] innovations in decentralized computing and economic incentives for scalability. Akshar Patel’s[

8] research on attack thresholds in Proof of Stake blockchain protocols addressed critical vulnerabilities in consensus mechanisms. Kabra’s[

9] work on self-supervised gait recognition and his music-driven biofeedback systems exemplified advancements in biometric tools and biomechanics. Recharla[

10] contributed to fault-tolerant systems in Hadoop MapReduce and decentralized file exchange hubs, enhancing scalability and reliability. Mehul Patel’s[

11] methodologies for traffic surveillance and water potability prediction demonstrated the integration of real-time adaptability and machine learning for public benefit.

Blockchain’s decentralized structure supported data privacy, making it ideal for healthcare, finance, and IoT [

12]. Features such as permissioning and audit trails [

13] were reflected in Recharla’s[

14] scalable systems. Talwar[

15] advanced adversarial AI evaluations with RedTeamAI and explored instructional assessment using language models. Kabra’s[

16] GLGait framework set real-world benchmarks for gait recognition, while his biofeedback systems extended these innovations. Malipeddi[

17] contributed hybrid detection strategies for Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) using honeypot sensors. Collectively, the efforts of Akshar Patel[

18], Mehul Patel[

19], Kabra[

20], Talwar, Malipeddi, and Recharla[

21] addressed critical challenges in privacy, security, and scalability.

Despite these contributions, most prior systems either relied on centralized control or lacked flexibility in access management. Few approaches effectively combined authenticated data structures with zero-knowledge proof mechanisms to support verifiable yet private disclosures. This work addressed these gaps by introducing BlockShare, which enabled fine-grained, verifiable data sharing without revealing underlying sensitive information.

3. Platform Overview and Security Features

BlockShare was developed as a blockchain-based data sharing platform designed to ensure security, privacy, and control over sensitive information. The system comprised four components: data originator, data custodian, blockchain network, and data beneficiary. Raw data, such as medical records or financial transactions, were stored off-chain by custodians. For each data item, an authenticated data structure (ADS) was generated and stored on the blockchain, enabling later verification without revealing the original data.

The platform’s key innovation lay in the use of a Merkle tree-based ADS that enabled fine-grained validation of shared data. Instead of storing entire datasets on-chain, only the Merkle Root was maintained. This approach reduced storage costs and preserved privacy while still allowing for integrity checks on any disclosed subset of data.

To facilitate secure sharing, data owners selectively revealed parts of their data along with a cryptographic Merkle Path, allowing recipients to verify the information’s authenticity against the stored root. Sensitive attributes could be hidden or generalized as needed.

Additionally, BlockShare employed zero-knowledge proofs to demonstrate data conditions without revealing the data itself. For example, a user could prove vaccination within the past 14 days without disclosing the exact date or location. This capability was essential in contexts requiring privacy-preserving verification, such as border control or workplace health checks.

The platform adhered to three core security principles: - Data Integrity: Shared data accurately reflected the original input without tampering. - Data Completeness: Only the relevant subset of attributes was disclosed as required. - Zero-Knowledge Privacy: Verification of conditions was achieved without exposing unnecessary information.

By combining these elements, BlockShare provided a trustworthy and efficient mechanism for secure data sharing in decentralized ecosystems.

4. DataSecure Architecture

This section introduced DataSecure, a novel approach for secure and transparent data exchange using blockchain technology. The proposed method aimed to ensure the authenticity of shared data through a robust version control system. In addition, it incorporated a privacy-preserving protocol that leveraged zero-knowledge proofs to protect sensitive information while maintaining compliance with data integrity standards.

4.1. Enhanced Data Integrity Verification

Data Structure Design and Storage. The integrity verification of shared data was realized through a decentralized model built on blockchain technology. As part of the DataSecure framework, original data records were generated from verified data sources and distributed across multiple owners for local storage. Simultaneously, a cryptographic data structure (ADS) was constructed for each record and stored on the blockchain as a verification of the data’s authenticity. For this purpose, the system applied a Hash Tree Structure (HTS) [

22], which generated a Merkle Root serving as the ADS for integrity verification.

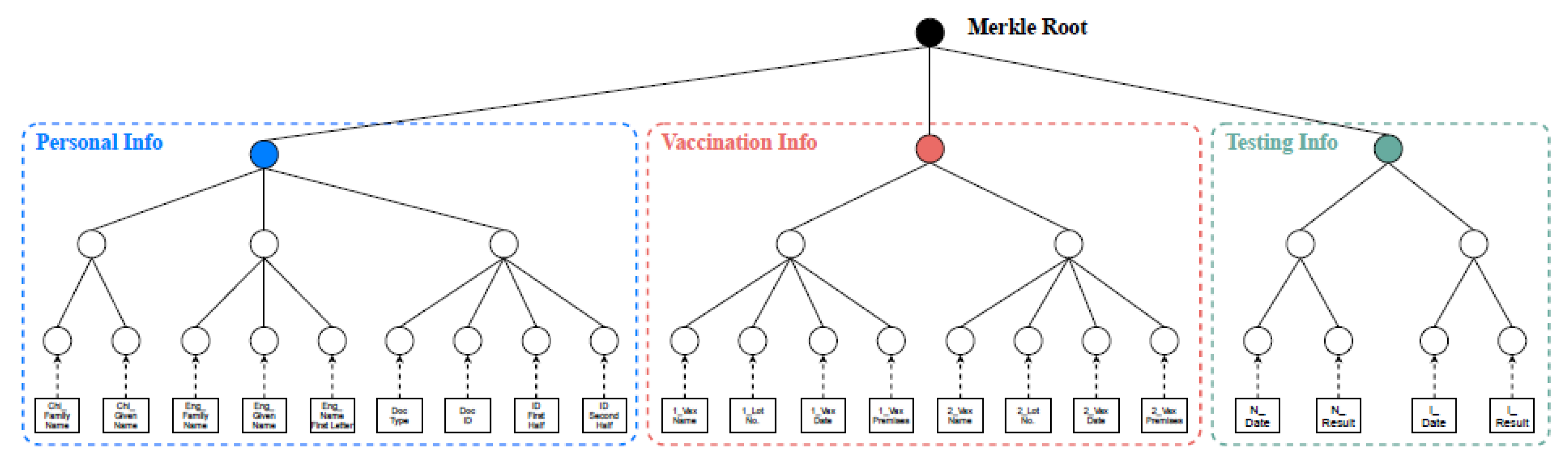

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the ADS construction process for a health monitoring record was presented. During the global health crisis, various countries implemented health monitoring systems to track public health data. A typical health monitoring record included demographic details, health status, and test results (e.g., PCR or antigen tests). To validate their health status, individuals were often required to present their health records when accessing certain services. A key concern was the potential for users to manipulate or forge records to circumvent screenings or conceal information.

To counter this, the system developed a custom HTS designed for precise health data management. To ensure privacy and protect against attacks such as rainbow table attacks, each data attribute was combined with a random value, producing a uniquely “salted” entry. The cryptographic hash for each leaf node was calculated as

where

represented a cryptographic hash function,

v denoted the attribute’s value,

was a randomly generated number assigned to the attribute, and ∥ indicated concatenation. Hashes for internal nodes were recursively derived from their respective child nodes. Ultimately, the Merkle Root, as shown in

Figure 1, was obtained by aggregating the hashes from the subtrees.

Due to the high costs of blockchain transactions, storing the entire HTS on-chain was not feasible. Instead, the process was optimized by storing only the Merkle Root, which was sufficient for validation.

Tailored Data Sharing and Authentication. In real-world data sharing scenarios, it was often necessary to implement varying levels of privacy protection. Data owners preferred to reveal only specific information depending on the recipient’s requirements. For example, an individual might have needed to confirm vaccination status without disclosing their identification number, vaccine type, or vaccination site.

Creating and storing separate ADS instances for every possible version of a data record was impractical. To solve this, a “single-ADS-for-multiple-versions” strategy was adopted. Here, each record was associated with a single ADS stored on-chain.

In this structure, individual data attributes were further subdivided into smaller sub-attributes and represented as leaf nodes in the HTS to support customized privacy levels. As shown in

Figure 1, an ID attribute could be split into two parts—representing the first and second halves of the number—and included in the HTS. This allowed the data owner to disclose only the necessary portions of the record while maintaining the integrity check through the consistent Merkle Root.

Moreover, data owners could obscure sensitive attributes using hash functions to generate a tailored version of the record. For any shared attribute, the data owner also constructed a verification component known as the Merkle Path, derived from the ADS. This component, together with the on-chain ADS, enabled the recipient to authenticate the data’s integrity.

4.2. Utilizing Zero-Knowledge Proofs for Stronger Privacy

In scenarios involving sensitive data exchange, privacy protection is crucial, and sometimes data obfuscation still exposes more details than necessary. For instance, while confirming someone’s vaccination status for a specified time frame (e.g., within the past two weeks), the visitor may still need to disclose the exact vaccination date.

To address this concern and enhance privacy, this paper suggest using non-interactive zero-knowledge (NIZK) proofs [

23] as a means to validate shared attributes while keeping the underlying data private. This approach allows the data owner to prove that certain criteria are met without revealing the exact value of the attribute, thus minimizing exposure of personal details.

In this method, the data owner first defines a condition for a specific attribute, which generally corresponds to the requirement of the recipient. Then, the data owner produces a proof that they meet this condition and shares it with the recipient, without disclosing the actual attribute value. This way, the data owner can show that they satisfy conditions such as being vaccinated within a certain period without revealing the exact date, location, or other identifying factors.

The formal definition of zero-knowledge condition verification is as follows:

4.3. Verification of Zero-Knowledge Conditions

Consider an attribute value v, a range R, a random salt value , a hash h of the attribute, the root of the ADS associated with the data record d, and global parameters . This scheme enables the prover to convince the verifier that they possess knowledge of an assignment to v such that , without revealing the actual value of v. The verification process consists of the following steps:

This verification framework ensures three core features of the BlockShare platform. First, it supports multiple data versions, enabling the creation of several variations of a data record tailored to different sharing contexts. Second, data integrity is guaranteed, as a single authenticated data structure (ADS) can validate all permissible versions of the same data. Finally, privacy is reinforced through two complementary mechanisms: obfuscation and generalization. Obfuscation hides sensitive attributes using cryptographic hashing, while generalization abstracts attributes—for instance, expressing age ranges or time windows instead of precise values.

In summary, the combination of dynamic data verification and zero-knowledge proofs ensures secure and verifiable data exchanges. It empowers data owners to retain control over what information is shared, supporting privacy and security. The following features are provided:

Multiple Data Versions Support: The system enables the creation of several variations of a data record to fulfill different requirements.

Ensuring Data Integrity: A single ADS can verify multiple versions of the same data.

Improved Privacy: Privacy is maintained through two main mechanisms: (i) Data Obfuscation: Certain attributes can be hidden, ensuring that sensitive details are not disclosed. (ii) Generalization: Data attributes can be made less specific, such as "within the last two weeks" or "ages 30-40."

5. System Deployment and Performance Analysis

This section covers the implementation of the SecureShare platform and provides a comprehensive performance evaluation.

5.1. System Architecture and Development

We developed a prototype for the SecureShare system, which includes the components for data providers, users, and verifiers, implemented using JavaScript and Python. The blockchain component is built using Solidity. The system integrates cryptographic techniques to maintain both privacy and integrity, with proof generation and verification handled by Circom and Snarkjs. The testing was carried out on a high-performance workstation featuring an Intel Core i7 3.9 GHz octa-core processor, 32 GB RAM, and a 512 GB SSD. All evaluations were performed using a randomly generated dataset.

5.2. System Performance Evaluation

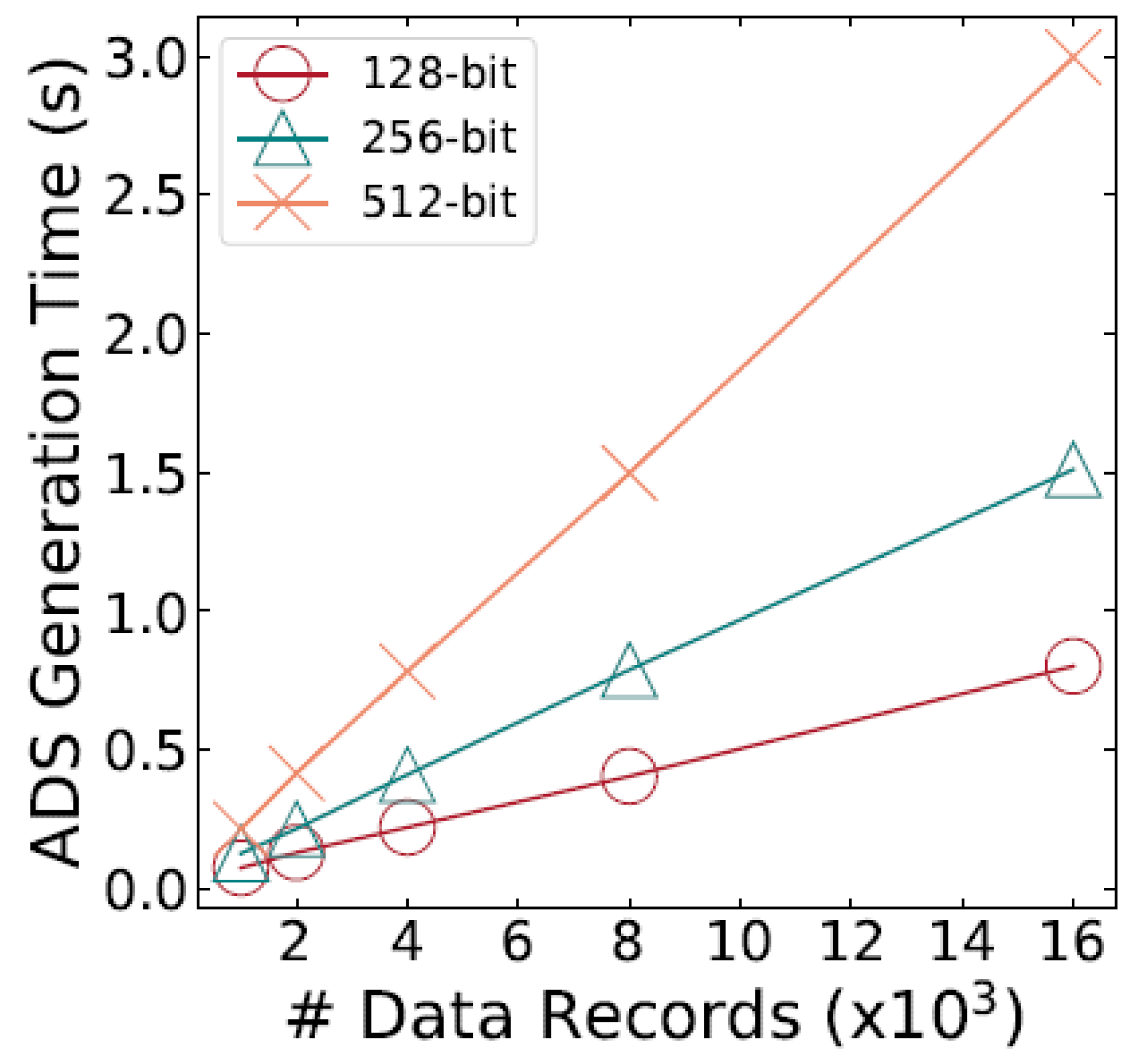

1) Data Structure Construction: We begin by evaluating the time taken to build the secure data structure (ADS) at various hash function lengths, using datasets with sizes of 500, 1K, 2K, 4K, and 8K entries. As shown in

Figure 2, the time for ADS construction increases proportionally with the dataset size. For 500 records, the ADS construction takes about 50 milliseconds, while for 8K records, the process takes approximately 1.5 seconds with a 128-bit hash. Even with a more complex 512-bit hash, building the ADS for 500 records still takes less than 0.3 seconds. For 8K records, the construction time reaches around 5 seconds, demonstrating the efficiency of the hashing function.

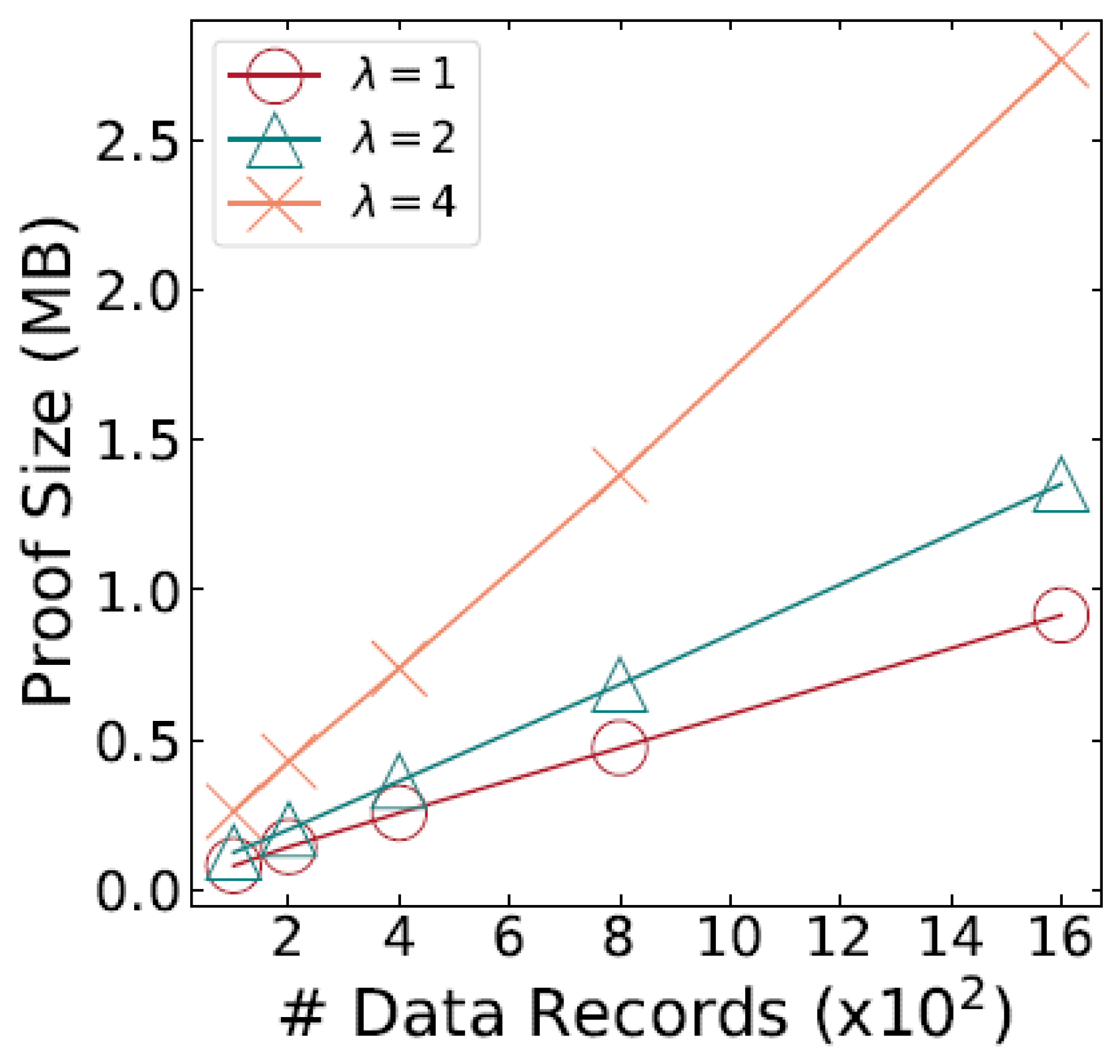

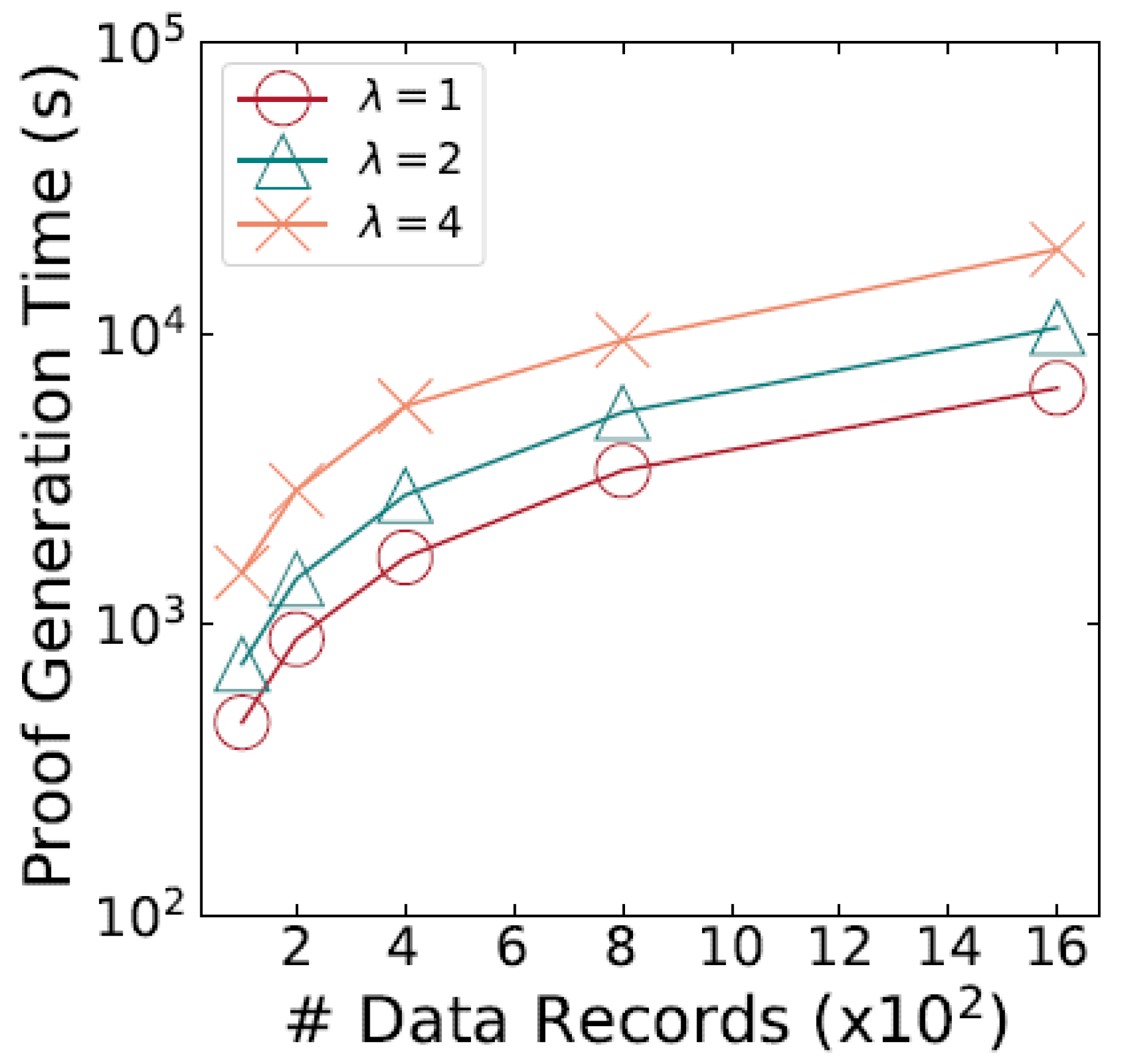

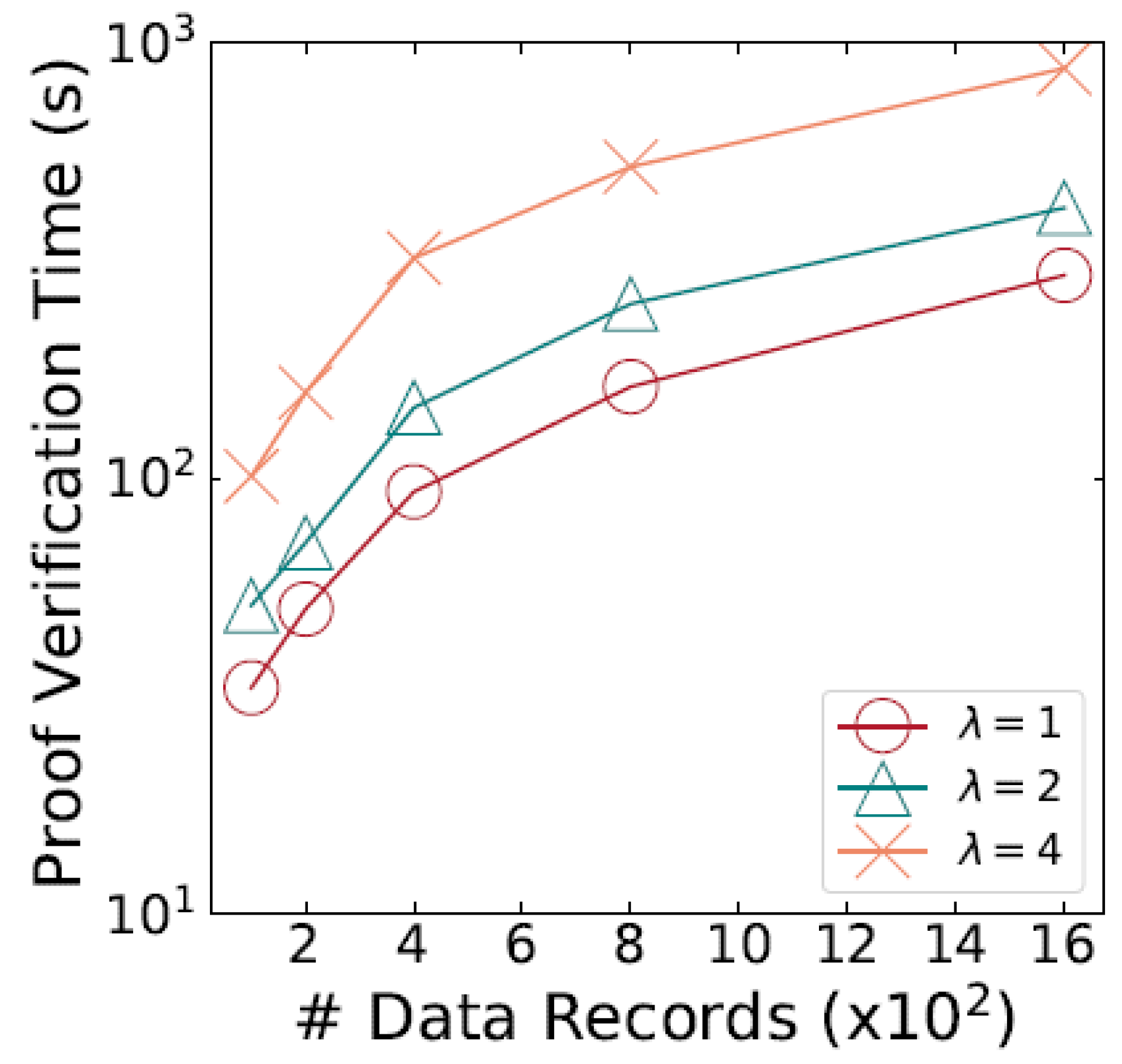

2) Proof Performance: Next, this paper evaluate the efficiency of the cryptographic proofs based on three primary criteria: (i) the size of the proof, (ii) the time needed for proof generation, and (iii) the time required for proof validation. We introduce to represent the number of attributes that must be verified for each dataset entry. Three distinct experimental setups are conducted, with values of 1, 3, and 5, respectively.

In

Figure 3, this paper show how the size of the cryptographic proofs changes as the record count grows from 200 to 1.2K. For a dataset containing 200 records, where each record includes a single attribute to be validated, the proof size is approximately 60KB. As the dataset expands to 1.2K records, with each record containing five attributes to verify, the proof size grows to about 2.3MB. Nevertheless, the total proof size stays under 3MB, indicating that SecureShare scales efficiently as the dataset grows.

Figure 4 illustrates the time taken to generate proofs for datasets of different sizes. For a dataset of 200 records, generating the proof for each record with one attribute takes around 5 minutes. As the dataset size increases and the number of attributes to verify per record rises, the proof generation time also increases. This reflects the trade-off between proof size and the time required to generate the proof within the cryptographic framework. One possible enhancement to mitigate this issue is pre-generating proofs for frequently occurring attribute conditions and reusing them.

Figure 5 presents the time taken for the verifier to validate the proofs, based on the size of the dataset. With 200 records and a single attribute to verify, the verification process takes about 20 seconds. However, for a larger dataset of 1.2K records, the verification time increases to roughly 4 minutes, which is still relatively quick. This demonstrates the strong performance of the proof verification process, a key feature that could drive broader adoption of SecureShare by data users.

3) Blockchain Costs: The SecureShare smart contract is deployed on the Rinkeby testnet of the Ethereum blockchain, where it handles the storage and retrieval of ADS metadata. As shown in

Table 1, the initial deployment of the contract requires around 450,000 gas units. The gas consumption for invoking methods is also recorded. Since the ADS only stores metadata and avoids large-scale data transfers, the gas cost for storing ADS data is relatively low—around 60,000 gas for a 256-bit ADS, irrespective of the dataset size. When retrieving ADS from the blockchain, the gas cost is about 25,000 gas, which translates to roughly

$0.05 when ETH is priced at

$1,500. This low cost is attributed to the minimal gas usage required for reading data from the blockchain.

The proposed system supports multiple data versions by enabling the generation of different record representations while maintaining integrity using a single ADS. This design choice enhances scalability and flexibility in privacy-preserving data exchange. Moreover, privacy is upheld through obfuscation techniques and generalization strategies that reduce information exposure without compromising verification. These capabilities collectively enable dynamic, fine-grained, and secure data sharing in decentralized networks.

6. Conclusion

This paper presented BlockShare, a privacy-preserving data sharing platform built on blockchain architecture. The proposed system introduced a novel authenticated data structure and incorporated zero-knowledge proofs to ensure the integrity and privacy of shared data. Through comprehensive evaluation, we demonstrated the system’s efficiency in proof generation, verification, and secure data sharing with minimal computational overhead. Unlike traditional systems that rely on centralized entities, BlockShare empowers users with full control over their data while enabling secure collaboration. The results indicate that BlockShare can serve as a foundational framework for future privacy-aware applications in domains such as healthcare, finance, and government services. However, further enhancements can be made to reduce proof generation times for large datasets and to extend compatibility with other decentralized storage networks. Overall, BlockShare marks a significant advancement in secure, decentralized data exchange.

References

- Kabra, A. MUSIC-DRIVEN BIOFEEDBACK FOR ENHANCING DEADLIFT TECHNIQUE. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH 2025, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, D. RedTeamAI: A Benchmark for Assessing Autonomous Cybersecurity Agents. OSF Preprints, 2025. Accessed on May 16, 2025.

- Recharla, R. Benchmarking Fault Tolerance in Hadoop MapReduce with Enhanced Data Replication. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Wireless Communications Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkadot, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Polkadot: Decentralized Web 3.0, Year. URL or other relevant details.

- Corda. Corda: A Distributed Ledger for Financial Services. Journal Name 2017, Volume, Pages. Additional notes if available.

- Zhang, A.N. Privacy-Preserving Blockchain Systems: A Survey. Journal Name 2019, Volume, Pages. Other relevant details.

- Patel, A. Empowering Scalable and Trustworthy Decentralized Computing through Meritocratic Economic Incentives. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th Intelligent Cybersecurity Conference (ICSC), 2024; pp. 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A. Evaluating Attack Thresholds in Proof of Stake Blockchain Consensus Protocols. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th Intelligent Cybersecurity Conference (ICSC), 2024; pp. 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, A. SELF-SUPERVISED GAIT RECOGNITION WITH DIFFUSION MODEL PRETRAINING. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH 2025, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recharla, R. Building a Scalable Decentralized File Exchange Hub Using Google Cloud Platform and MongoDB Atlas. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Wireless Communications Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M. Robust Background Subtraction for 24-Hour Video Surveillance in Traffic Environments. TIUTIC 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, A.N. MedicBlock: A Blockchain-Based Medical Data Sharing Platform. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2021, 17, 7669–7678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.N. Audit Mechanism for Blockchain-Enabled Systems. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2020, 69, 4298–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recharla, R. FlexAlloc: Dynamic Memory Partitioning for SeKVM. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Wireless Communications Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), 2025; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, D. Language Model-based Analysis of Teaching: Potential and Limitations in Evaluating High-level Instructional Skills. OSF Preprints, 2025. Accessed on May 16, 2025.

- Kabra, A. GLGAIT: ENHANCING GAIT RECOGNITION WITH GLOBAL-LOCAL TEMPORAL RECEPTIVE FIELDS FOR IN-THE-WILD SCENARIOS. PARIPEX INDIAN JOURNAL OF RESEARCH 2025, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malipeddi, S. Analyzing Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) Using Passive Honeypot Sensors and Self-Organizing Maps. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics (ESCI), 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A. Evaluating Robustness of Neural Networks on Rotationally Disrupted Datasets for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Foundation and Large Language Models (FLLM); 2024; pp. 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M. Predicting Water Potability Using Machine Learning: A Comparative Analysis of Classification Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Energy Internet (ICEI); 2024; pp. 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, A. EVALUATING PITCHER FATIGUE THROUGH SPIN RATE DECLINE: A STATCAST DATA ANALYSIS. PARIPEX INDIAN JOURNAL OF RESEARCH 2025, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recharla, R. Parallel Sparse Matrix Algorithms in OCaml v5: Implementation, Performance, and Case Studies. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Wireless Communications Signal Processing and Networking (WiSPNET), 2025; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hash, A.N. Secure Hashing Algorithms. Cryptography Journal 1987, Volume, Pages. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.N. Zero-Knowledge Proofs in Cryptography. Cryptographic Theory and Applications 2017, Volume, Pages. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).