The study of river basin ecosystems located within arid and semi-arid zones of both hemispheres is now particularly urgent. Freshwaters across our planet are experiencing tremendous stress, they are characterized by extremely high rates of habitat degradation and, consequently, loss of native biodiversity. However, perhaps no other type of freshwater habitat is in such a critical state as the ecosystems of arid and semiarid areas. Desertification, salinization of soils and surface waters, disruption of the natural hydrological regime, and reduced river flow – this is just a short list of the challenges threating these basins and the aquatic communities inhabiting them today [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Therefore, much effort is devoted to studying the current state and potential trends of communities of living organisms inhabiting freshwater in desert and semi-desert regions of the Earth. Among the most popular subjects among researchers are freshwater benthic invertebrate communities, characterized (normally) by relatively high taxonomic and functional diversity, and by the presence of organisms with various life cycles and positions in ecological networks (webs). The most important components of benthic communities in most basins globally are insects, crustaceans, molluscs, oligochaetes, nematodes, and several higher taxa. However, the high diversity of invertebrates and the vast area occupied by arid regions on the Earth's surface have resulted in uneven study of freshwater communities within individual basins, macroregions, and entire continents. For many basins, data are either completely absent, insufficient, or outdated. Therefore, case studies devoted to particular river basins/or groups of benthic invertebrates are now of great importance.

Among the latter, freshwater molluscs (gastropods and bivalves) are in urgent need of study. This is not to say that they have not attracted the attention of researchers. However, overall, there are relatively few studies on freshwater Mollusca of rivers and lakes in arid and semi-arid zones i.e. [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. In addition to their applied ecological sifnificance, the molluscan communities of these regions are of fundamental interest as model objects for studying some issues of evolution, taxonomy, and biogeography i.e., [

12,

13,

14].

This work is an example of such a specific study, the aim of which is to investigate the species richness of freshwater mollusks and the factors determining it in a single river basin. Studies of this kind remain relatively rare [

15].

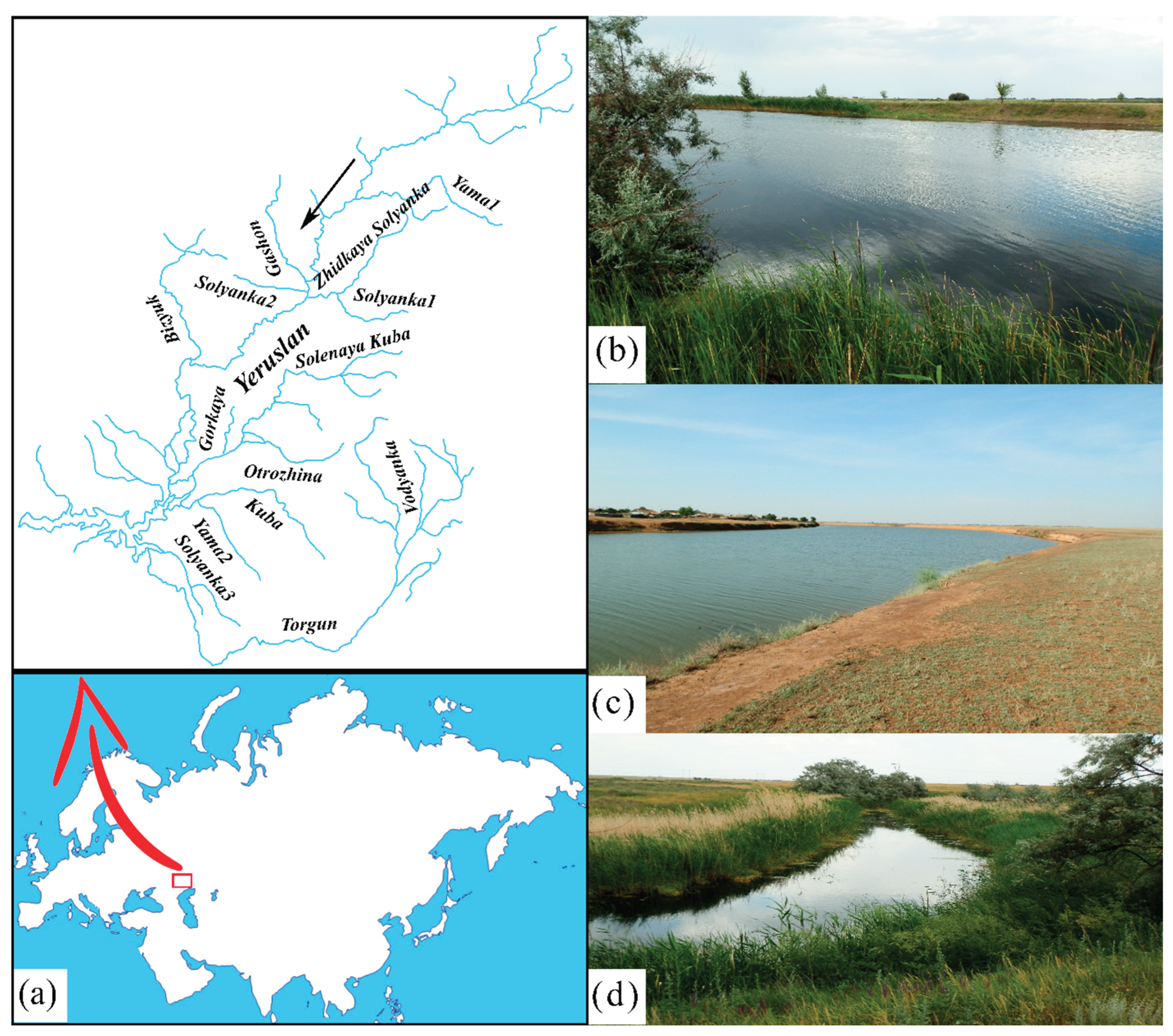

The studied riverine ecosystems belong to the Yeruslan River basin (a left tributary of the the Volga River, in the lower course of the latter), located in the southern East European Plain within the Saratov and Volgograd regions of the Russian Federation. The data provided in this article represent the first attempt to provide a comprehensive ecological and taxonomic analysis of the malacofauna of this river basin, which may make a small contribution to a better understanding of the functioning of river ecosystems in the arid zone of the European continent.

The history of studying the freshwater fauna of the Lower Volga basin began in the late 18th century [

16]. The literature contains a number of works on the mollusсs of water bodies belonging to this basin [

17,

18,

19,

20], but the data contained therein are far from complete and are largely outdated from the standpoint of current taxonomy and/or nomenclature. For many river basins in this region, information on their malacofauna is completely absent. One such basin is the Yeruslan River basin, located on the left bank of the Volga within the semi-desert and desert climatic zones. Information on the malacofauna of this river basin is limited to just one work, published more than 90 years ago [

21]. The malacological material used by the authors can be considered fragmentary; the data presented in this source were based on a sample made from a single station located in the lower reaches of the Yeruslan River and include a list of six species of freshwater molluscs, without accompanying information on the ecology and abundance of these species. The current whereabouts of this sample remains unknown, and thus we are unable to verify or correct the content of this species list.

Given that the Lower Volga region is currently experiencing significant climate change [

22], the availability of up-to-date, systematic data on freshwater mollusks in the river basins located within its territory has not only fundamental but also practical importance. This area is subject to prolonged dry periods with a total annual precipitation of 200–300 mm, and evaporation exceeds precipitation by 2–3 times [

23]. The river network in these conditions is practically undeveloped, and most small rivers do not have a constant inflow [

24]. These conditions, combined with anthropogenic factors, intensify desertification processes in arid areas, including the Lower Volga region [

25]. The riverine fauna in these regions is depleted and has an extremely patchy distribution [

26,

27].

1. Material and Methods

The primary material for this research was collected in the rivers of the Yeruslan basin during the summer period of 2015–2017 (

Figure 1). The Yeruslan River flows through the Saratov Low Trans-Volga region and the Caspian Lowland. It originates on the southwestern edge of the Obshchiy Syrt Uphills and flows into the Volgograd Reservoir, forming Yeruslan Bay. The river is 282 km long, and its catchment area is 5,570 km

2. In spring, the water level rises by 5–6 m, accounting for approximately 70% of the annual runoff. After the flood period ends, the river turns up into a series of isolated or semi-isolated stretches, and its tributaries partially dry up [

28].

The samples were taken from 15 lotic waterbodies, including the Yeruslan River proper. Molluscs were found in 11 of them. A total of 72 qualitative and quantitative samples were taken at 33 sampling stations. The location of the stations was determined in such a way that they were distributed at an equal distance from each other, which allows for maximum coverage of the upper, middle and lower reaches of the rivers. The collection of samples was made using the standard method [

29,

30]: benthic organisms were collected in the ripal (littoral) zone of rivers with a scraper (with 0.2 × 0.5 m sampling area), or (in deeper places) an Ekman-Bergi grab (sampling area = 1/40 m

2 × 2). The samples collected were washed immediately using a 0.50 mm sieve. All zoological material was preserved in a 95% ethanol solution, which was replaced with a 70% solution after one week. The species identification of molluscs was caried out using modern identification guides and manuals, primarily based on shell characteristics [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. The nomenclature of species and genera is given according to the MolluscaBase database (

https://www.molluscabase.org/index.php), except for

Theodoxus pallasi (see [

35] for discussion on the taxonomy and nomenclature of this species).

At the sampling sites, the depth, width, and the flow velocity were measured. Water pH (by means of a HANNA HI98127 pH meter with a thermometer) and dissolved oxygen content (by means of a HANNA HI9146 oximeter) were determined. Water samples were collected directly at the sampling sites from the surface (up to 0.5 m depth) using a 4-liter bathometer. Hydrochemical analysis of the samples was performed in the accredited laboratory of the Center for Monitoring the Water and Geological Environment, LLC (Samara).

The true species richness of mollusks was estimated using nonparametric algorithms [

36] followed by plotting. Similarity coefficients were calculated using the Bruy-Kurtis index, with results presented in ordination by means of the nonmetric scaling method (NMDS) [

37]. The Palia-Kovnatsky dominance coefficient (d) was calculated based on the abundance and occurrence of individuals [

38]. Mollusc diversity in the rivers was assessed using the Shannon index (H) and Pielou evenness (E) [

39]. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to elucidate the distribution patterns of molluscs across stations depending on environmental factors. The overall correlation between abundance and environmental conditions in biotopes was assessed using canonical correspondence analysis (CCA). The data on the abundance of individual mollusc taxa were preliminarily transformed using the common logarithm (lg(x+1)) to reduce the “weight” of rare species. The significance of individual canonical axes was assessed using a Monte Carlo simulation for 999 permutations [

40].

Statistical calculations were performed using Canoco version 4.5 software the R programming language (version 4.3.0) in the RStudio integrated environment with the following packages: vegan, Spade-R, CCA, and reshape. Differences between individual parameters were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05.

2. Results

In total, 28 species of freshwater mollusсs from 24 genera and 13 families were identified in the surveyed watercourses of the Yeruslan River basin: Acroloxidae (1 genus, 1 species), Lymnaeidae (3 / 4), Physidae (2 / 2), Planorbidae (5 / 5), Viviparidae (1 / 1), Valvatidae (1 / 2), Bithyniidae (2 / 2), Neritidae (1 / 1), Lithoglyphidae (1 / 1), Dreissenidae (1 / 2), Cardiidae (1 / 1), Unionidae (2 / 3), Sphaeriidae (3 / 3). The fauna is dominated by species with wide ranges (Holarctic and Transpalearctic), with a certain fraction of species of Ponto-Caspian origin (

Table 1).

The highest species richness of molluscs was recorded in the Yeruslan River – 22 taxa; in smaller rivers of the basin, the number of species found varied from 2 to 10. Two pond snail species appeared to dominate in the river fauna: Radix auricularia (64% frequency) and Lymnaea stagnalis (60%), which can be considered widespread species in the basin (frequency ≥ 50%).

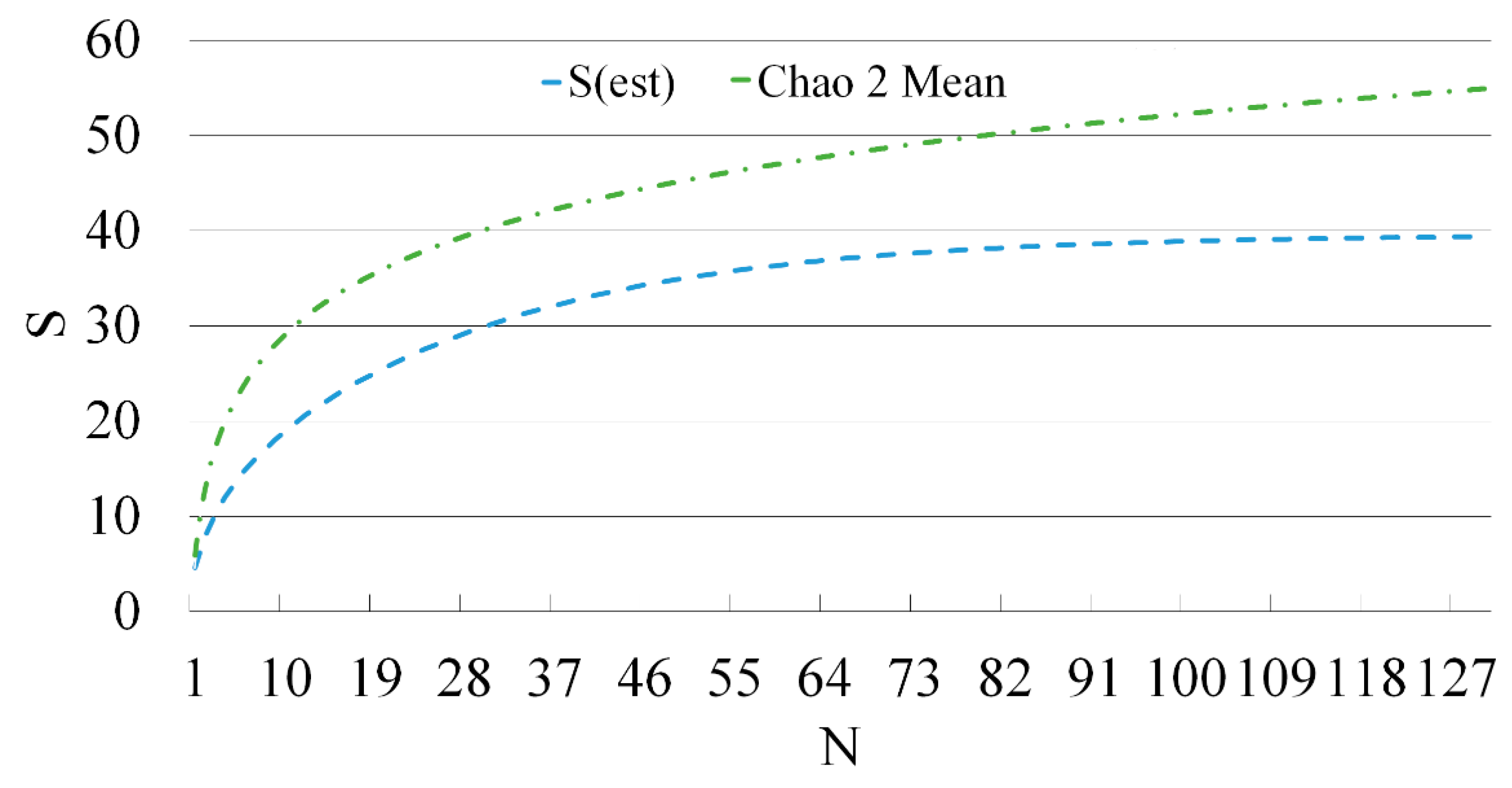

An estimation of the true species richness of the mollusc fauna for all rivers of the Yeruslan basin using a rarefaction curve revealed no horizontal asymptote (

Figure 2). The predicted mollusc species pool, with an increased sampling effort of 130 samples – an asymptotic straight line – is observed at the level of 39 taxa. However, the results of the non-parametric Chao2 method show that even more species – up to 55 – can be expected to be present within the study area.

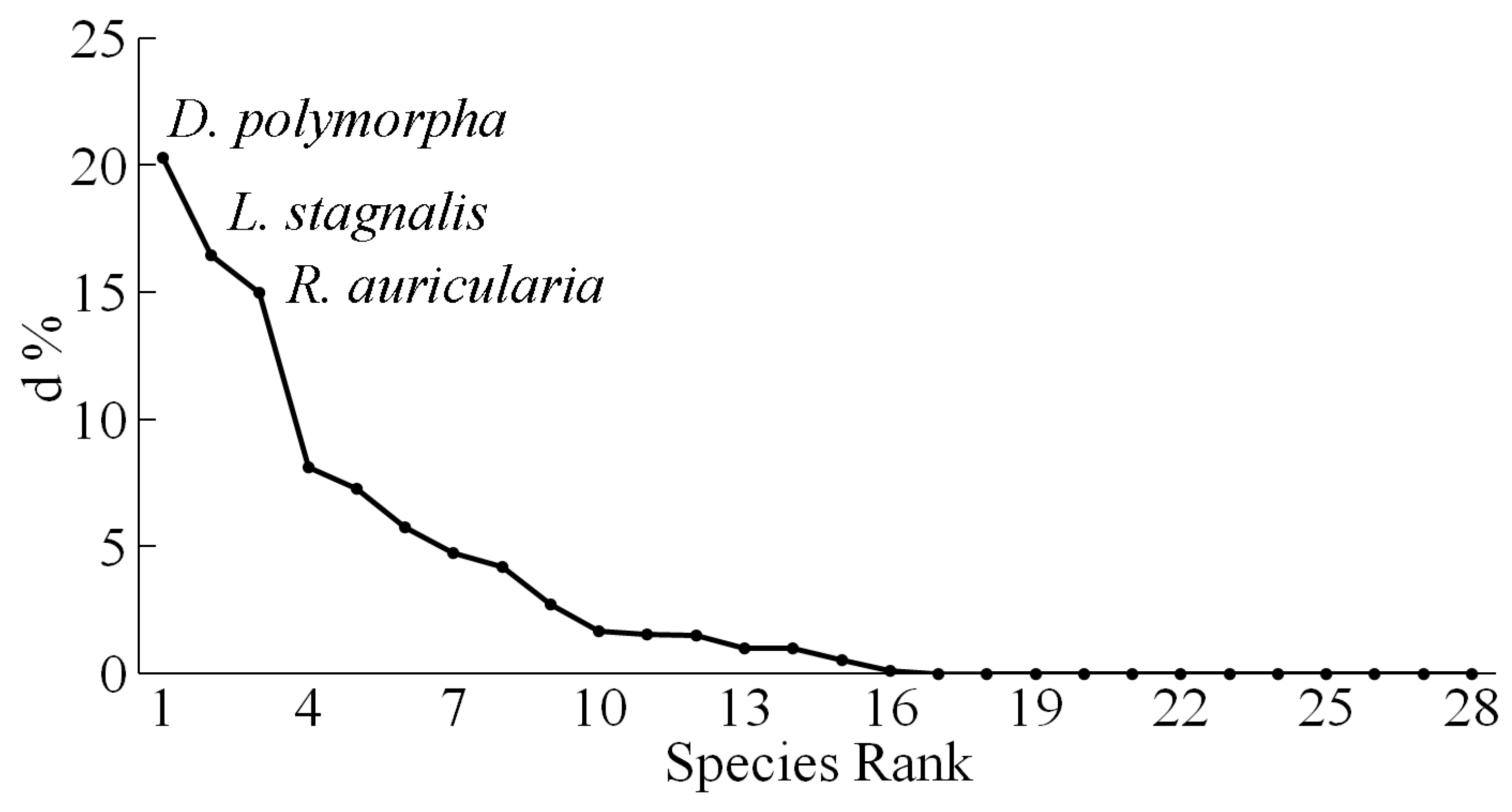

The malacofauna of all the studied rivers exhibits a few common patterns. The dominant species complex in the watercourses is formed by three taxa:

Dreissena polymorpha,

L. stagnalis, and

R. auricularia (

Figure 3). Moreover, at all surveyed stations where

D. polymorpha was encountered, this species was the most abundant. In the upper reaches of the Yeruslan River,

L. stagnalis and

R. auricularia predominate, while in the middle and lower reaches, only

D. polymorpha is present. The two lymnaeids,

L. stagnalis and

R. auricularia, were almost always the dominant species in the small watercourses of the basin.

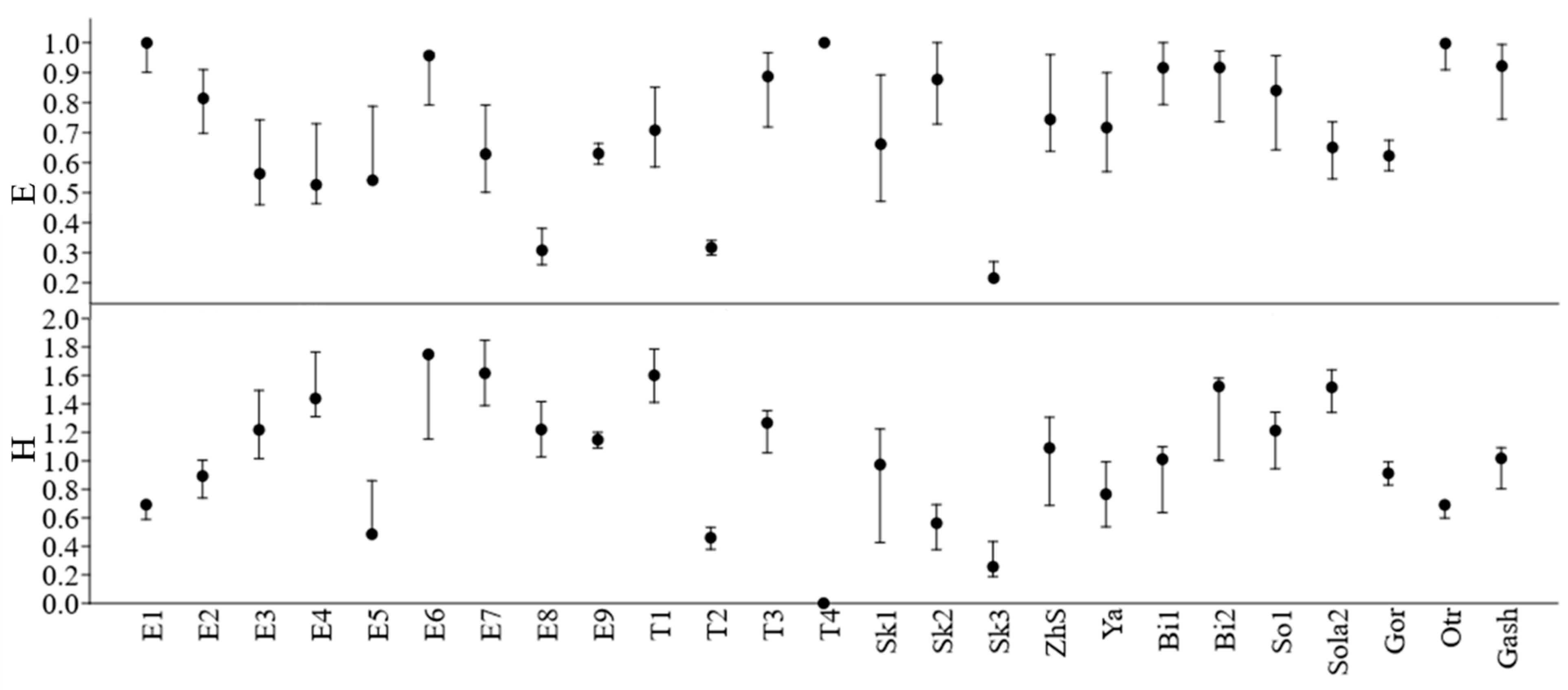

The Shannon diversity index of molluscan communities of the Yeruslan River basin had low values, averaging 1.05 bits/specimen (

Figure 4). Its peak was observed in the middle reaches of the Yeruslan River – 1.75 bits/specimen, and the minimum value was found in the lower reaches of the Torgun River, 0 bits/specimen, where only one species was discovered. The average index values in the Yeruslan River tributaries (0.99 bits/specimen) were virtually identical to those in the main river of the basin (1.16 bits/specimen). The average value of the mollusc evenness index in the watercourses was 0.71±0.05, which corresponds to the relative evenness of all species. Its maximum values (1.0) were observed in the lower reaches of the Torgun River, whereas the minimum (0.22) was found in the lower reaches of the Solenaya Kuba River. The average evenness values at the stations of the Yeruslan River – 0.66 (t = 8.96; p = 0.00) practically did not differ from that of its tributaries – 0.73 (t = 13; p = 0.00).

The studied rivers of the Yeruslan basin are characterized by low flow velocities of 0–0.05 (t = 4.58; p = 0.00) m/s and a maximum depth of only 3 m. The bottom substrates in most cases are represented by sandy and sandy-silty sediments with plant detritus. The area of macrophyte coverage is quite high and usually exceeds 50%. The rivers are characterized by high dissolved salt contents of 235–2870 (t = 6.79; p = 0.00) mg/L, with an average temperature of 26 °C. In terms of the ratio of predominant ions, all types of natural waters (according to classification by Alekin [

41]) are represented in the Yeruslan River basin. The main pollutants of the riverine waters are heavy metals (see Golovatyuk and Mikhailov [

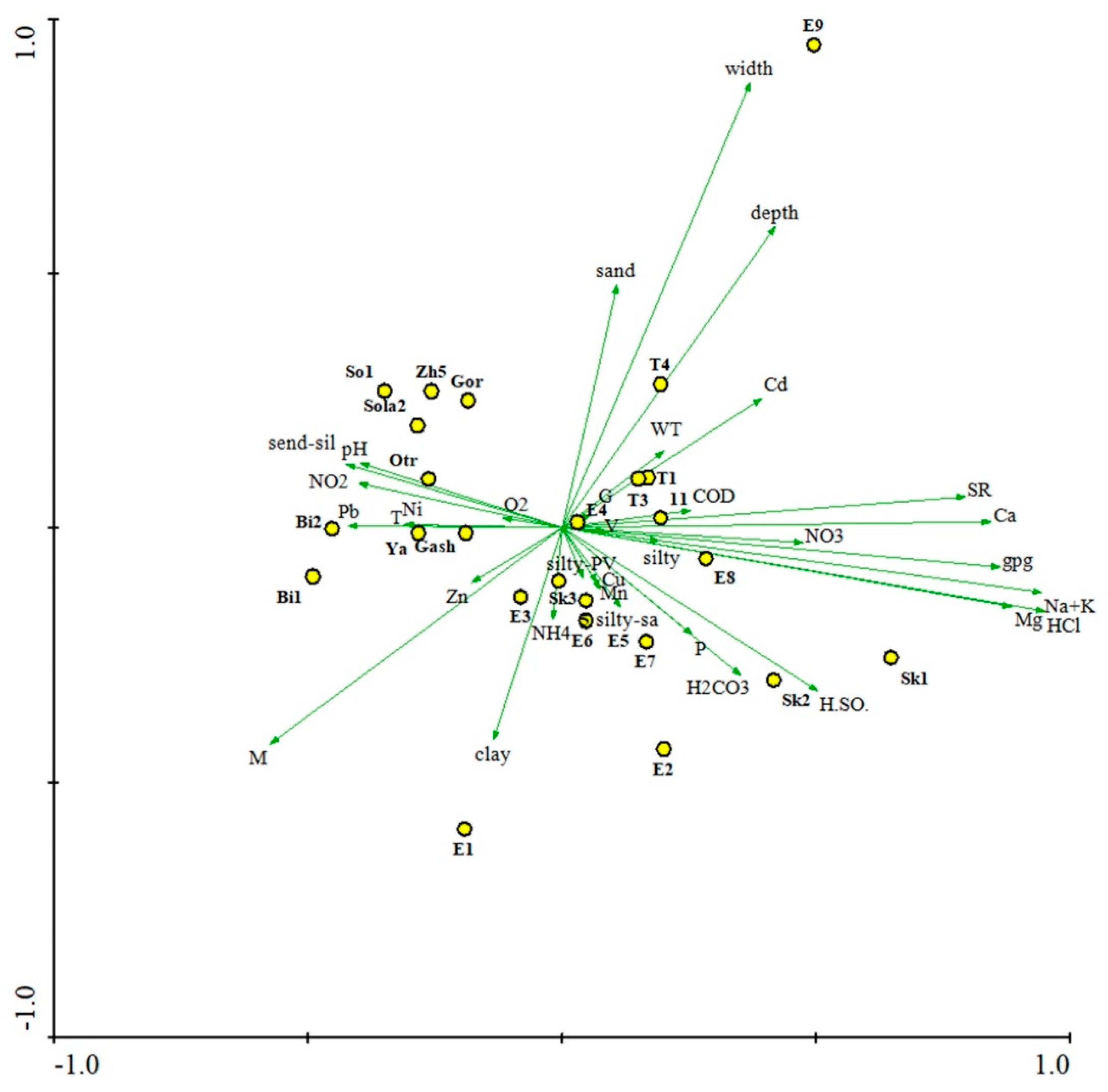

42] for a more detailed hydrological and physicochemical characteristics of the studied rivers). A principal component analysis (PCA) of the main environmental factors in the Yeruslan River basin revealed that the main differences between stations can be explained by ion ratios, dry matter concentration, and substrate type (

Figure 5). The first axis is primarily characterized by changes in dry matter content and macroion concentrations, while the second axis is characterized by changes in soil type and heavy metal content in the water. Variables related to river hydrological conditions are located along the second axis. Station No. 9 in the Yeruslan River is situated somewhat distantly from the others in the ordination, because of it was located in a river bay, where the habitat characteristics are significantly influenced by the waters of the Volgograd Reservoir.

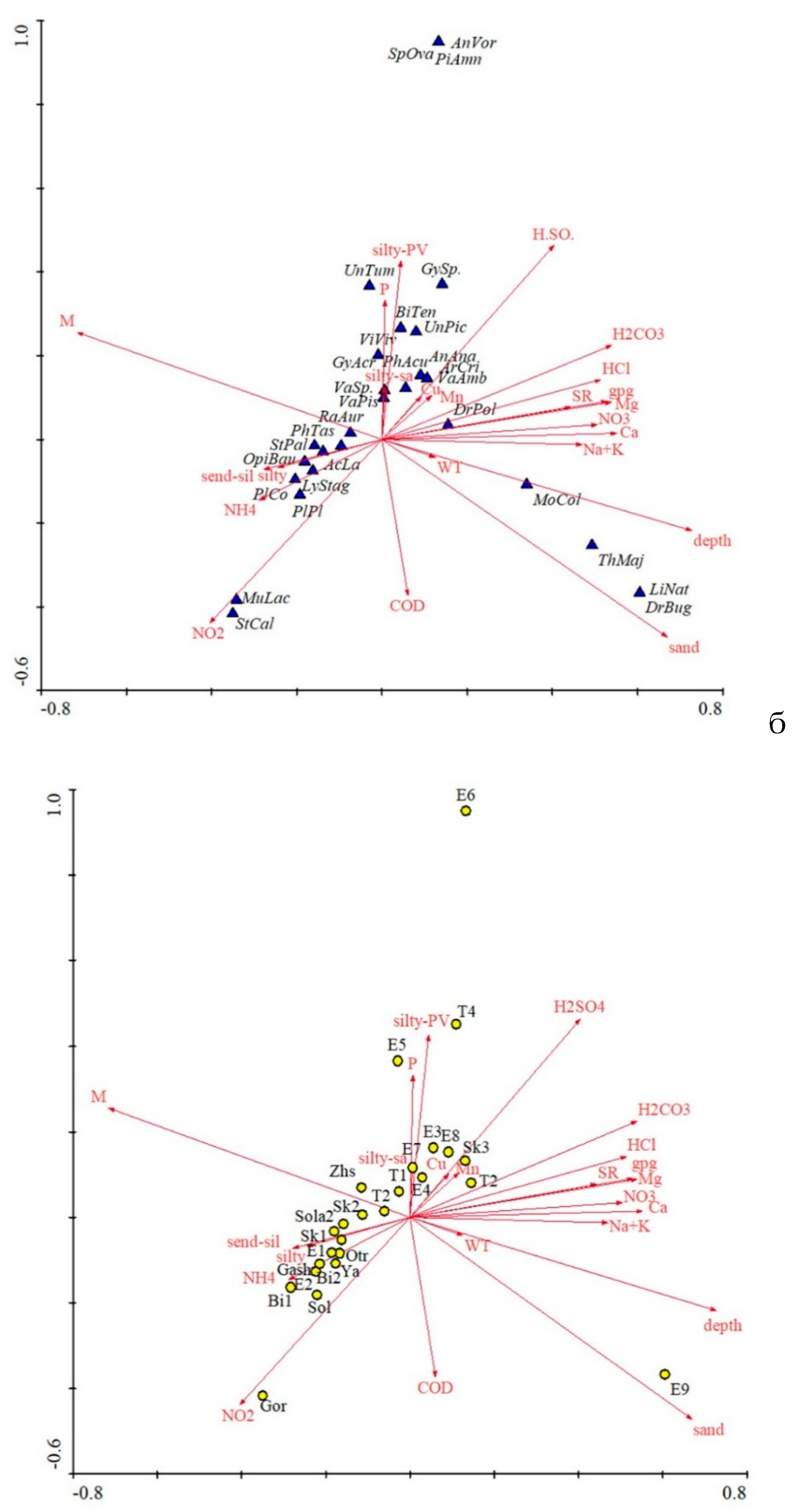

Figure 6 (a and b) shows the influence of abiotic and biotic environmental factors on molluscs in the rivers of the Yeruslan basin as it was revealed with help of canonical correspondence analysis (CCA). The significance of environmental factors was determined based on the Monte Carlo test between each pair of river stations in the multidimensional space of taxon diversity (

Table 2).

Based on its results, 11 of the 34 assessed variables were excluded from further analysis due to low lambda values, the use of which reduces the overall correlation coefficient. Of the remaining variables, only three have a significant effect on the distribution and abundance of molluscs. The multidirectionality of the vectors characterizing environmental conditions indicates a high relationship between the identified factors, which form a multicollinear complex. The loading on the first axis is 56%, whereas all canonical axes together explain 84% of the accumulated variance. The grouping of the factors is closely related to the position of species in the diagram. Along the main axis, various mollusc species and sampling stations are projected, determined primarily by the type of bottom substrate and nitrogen compounds. The second axis weakly correlates with the area of macrophyte coverage and the phosphate content of the water. The most isolated station is located in the Volga River backwater zone. This bay of the Yeruslan River is home to species of the Ponto-Caspian complex – Dreissena bugensis, Lithoglyphus naticoides, and Theodoxus pallasi — confined to deepwater areas with high transparency and a sandy bottom.

3. Discussion

Available literary sources [

17,

21] provide information on the presence of six species of freshwater mollusсs in the Yeruslan River basin. One of them,

Viviparus duboisianus (Mousson, 1863) [=

Viviparus viviparus of the current nomenclature], belongs to Gastropoda, the rest belong to bivalves. Of the latter, two species, listed in the literature as

Anodonta cellensis C. Pfeiffer, 1821 and

A. piscinalis Nilsson, 1823, are considered in modern taxonomy as junior synonyms of the duck mussel,

Anodonta anatina (Linnaeus, 1758) [

43]. Three other species of bivalve mollusks from the Yeruslan River basin, known from the literature, are

Unio pictorum (Linnaeus, 1758),

U. tumidus Philipsson, 1789 and

Pisidium casertanum (Poli, 1791) [in the current nomenclature known as

Euglesa casertana; see 44]. In the course of this research, 28 species were found in the watercourses of the Yeruslan basin, and 25 taxa from the final list were registered here for the first time (see

Table 1). Of the previously recorded species,

Euglesa casertana was not found by us alive, although it can be considered almost certain that this mollusc, which is among the most abundant and widespread representatives of the family Sphaeriidae [

44,

45,

46], inhabits the Yeruslan basin (we collected some empty shells which can belong to it, but a molecular study is needed in order to prove his presence in this basin). A relatively high species richness (22 species) was found within the main watercourse of the basin, the Yeruslan River, and six species were found in its tributaries.

It should be stressed that we did not include to the statistical analyses described above the data based on the finding of empty shells of various mollusc species in the rivers. The rationale for this is that dry shells can be transported over long distances by running waters and also washed out during spring floods from floodplain habitats, as well as from reservoirs located on terraces outside the floodplain but with intermittent connections to the river channel. Therefore, it cannot be definitively stated that these species are actually included in the mollusc community of a given river. Nevertheless, we identified this shell material and determined that at least five species are represented in it: Gyraulus albus (O.F. Müller, 1774), Segmentina nitida (O.F. Müller, 1774), Hippeutis complanatus (Linnaeus, 1758) [all – family Planorbidae], Pseudanodonta complanata (Rossmässler, 1835) [Unionidae], Sphaerium rivicola (Lamarck, 1818) [Sphaeriidae]. We could not find a single representative of the indicated species alive. In addition, data from a number of rivers and stations where mollusсs were either completely absent or only empty shells were found were omitted from the analysis. These rivers and stations were: Yama 2, Solyanka 3, Vodyanka, and Kuba.

Thus, if we consider the species represented only by empty shells, it can be argued that the analyzed dataset is relatively complete, since our collections contain about 90% of the expected number of species estimated using the non-parametric Chao 2 method.

The number of mollusс species recorded by us in the Yeruslan River basin was relatively low in comparison with the species richness typical for malacofaunas of lowland rivers in the forest-steppe and steppe zones of the East European Plain [

47,

48]. The species richness of the Yeruslan Basin malacofauna is characterized by a sharp predominance of gastropods (19 species), while in other bioclimatic zones both classes of freshwater molluscs are represented in approximately equal proportions [

47,

48]. The reasons for this disparity can only be determined hypothetically. Freshwater bivalves burrow into the bottom sediment and are therefore considered good indicators of the stability of riverine substrate conditions [

48]. However, the diversity of bottom deposits in the Yeruslan basin is rather high. At the stations we studied, they are represented by different types, from sand to silts with plant residues. The simplest factor explaining the reduced number of bivalve species is probably the peculiar temperature regime in the watercourses of this region, which warm up strongly in summer, so that the average water temperature in them can reach 30 °C [

29]. In addition, the hydrological regime of rivers is of great importance for bivalves. Low flow velocity, and often its complete absence, negatively affects the distribution and/or density of their populations [

50]. Due to these and other factors, such as the inflow of various organic pollutants as a result of anthropogenic activities, the local biota consumes oxygen at an increased level, exceeding the oxygen supply as a result of photosynthesis, mixing and diffusion [

51]. We observed low oxygen concentrations (7 mg/l) at most of the sampling stations, which may signal a shortage of this gas in the aquatic environment and limit the existence of bivalves. Prolonged hypoxia can lead to high mortality, while short-term hypoxic events often cause a decrease in growth and reproduction rates and even behavioral changes [

52].

The low values of the diversity index of mollusсan communities in the rivers of the Yeruslan basin may reflect the low productivity and stability of their host ecosystems. Considering that the loss of species in systems with high biodiversity has less impact on ecosystem functioning than in systems with low biodiversity [

53,

54], the disappearance of even a single species will lead to the loss of important functions and services provided by its representatvies (for example, food resources for higher trophic levels; nutrient cycling through excretion, deposit of faeces and pseudofaeces; empty shells may be important for ecosystem engineering processes, etc. [

55,

56]. The main reason for such changes in semi-desert regions may be the reduction of habitats as a result of periodic and even permanent drying of riverbeds.

According to the value of the homogeneity index of the studied malacocenoses, these can be classified as relatively sustainable communities. This means that the malacofauna is in a stable state, since the abundance of individual species in the surveyed watercourses does not vary much [

57]. At the same time, the level of species dominance remains low, and the group of dominant taxa consists of a low number of typical euryoecous mollusc species distributed both throughout the Volga basin and far beyond its borders [

31,

58].

Our data show that the bottom substrate plays an important role in regulating both distribution and abundance of mollusks in the studied watercourses (see

Figure 6). Many authors consider the nature of bottom sediments to be one of the most influential environmental factors determining the distribution of malacofauna [

59,

60]. This factor is closely related to such an important characteristic, primarily for gastropods [

61], as the area coverage with macrophytes. However, due to the fact that this factor was not very variable in the studied watercourses, it showed a low correlation with the abundance of mollusks.

Along with the type of bottom substrate, the viability and abundance of freshwater molluscs in the studied watercourses are affected by the level of nitrites and phosphates in the water (see

Figure 6). These nutrients are often the main components of wastewater. High levels of organic pollutants can contribute to diseases and death of aquatic organisms and changes in the species composition of their communities [

62]. However, their concentrations in the water in the studied river basin were far from critical, and the presence of these compounds rather increased the productivity of watercourses, which had a beneficial effect on the distribution and development of malacofauna in the arid region.

At last, one more important factor needs to be mentioned here. It is the level of water salinity, which affects the osmolality of freshwater mollusks [

63]. The dry residue values at some our stations reached 2870 mg/l, which is critical for many species of molluscs [

29]. According to our data, species of gill-breathing (branchiate) mollusks were absent at stations where its values were above 1000 mg/l. The only exceptions were the non-native bivalves of Ponto-Caspian origin from the genus

Dreissena.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.M., M.V.V. Methodology, R.A.M.; Software, R.A.M.; Literary Survey, R.A.M.; Species identification, M.V.V.; Statistical Analysis, R.A.M..; Fieldwork, R.A.M.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, R.A.M.; Writing – Review & Editing, all authors; Visualization, R.A.M.

Funding

The work was carried out within the framework of a state budgetary project (№ 1250130010890).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The primary materials (gastropod and bivalve samples) for this study are placed in Laboratory of Macroecology and Biogeography of Invertebrates, St.-Petersburg State University (curated by M. Vinarski). Original data, used and collected during this research, are available (with reservations) upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Doctor of Biological Sciences L.V. Golovatyuk for the opportunity to participate in expeditionary research in the Yeruslan River basin.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Verstraete, M.M., Scholes, R.J., Smith, M.S. Climate and desertification: looking at an old problem through new lenses. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7(8), 421–428. [CrossRef]

- Cañedo-Argüelles, M., Kefford, B.J., Piscart, C. et al. Salinisation of rivers: An urgent ecological issue. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 173, 157–176. [CrossRef]

- Zolotokrylin, A.N. Climatic desertification. Nauka Publishers: Moscow, Russia. 2003 (In Russian).

- Zolotokrylin, A.N. Global Warming, Desertification/Degradation, and Droughts in Arid Regions. Izvestiya Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk. Seriya Geograficheskaya. 2019, 1, 3–13. (In Russian) . [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Wang, T., Kang, W., David, M. Several challenges in monitoring and assessing desertification. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 73, 7561–7570. [CrossRef]

- Moyano-Salcedo, A.J., Piana, T., Crabot, J. et al. GLOBal river SALiniTy and associated ions (GlobSalt). Sci. Reps. 2025, 15, 18701. [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, S.I., Andreev, N.I., Mikhailov, R.A. Records of mollusks of the genus Caspiohydrobia Starobogatov, 1970 (Gastropoda, Hydrobiidae) in salt rivers of the Caspian Lowland. Biology Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 2020, 47, 912–919. [CrossRef]

- Idowu, R.T., Gadzama, U.N., Abbatoir, A., Inayng, I.M. Molluscan population of an African arid zone lake. Animal Res. Int. 2007, 4(2), 680–684. [CrossRef]

- Rossini, R.A., Tibbetts, H.L., Fenscham, R.J., Walter G.H. Can environmental tolerances explain convergent patterns of distribution in endemic spring snails from opposite sides of the Australian arid zone? Aquat. Ecol. 2017, 51, 605–624. [CrossRef]

- Paiva, F.F., Gomes W.I.A., Medeiros C.R. et al. Environmental factors influencing the occurrence of alien mollusks in semi-arid reservoirs. Limnetica. 2018, 37(2), 187–198. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Quintero, J.C. Environmental determinants of freshwater mollusc biodiversity and identification of priority areas for conservation in Mediterranean water courses. Biodiv. Conserv. 2011, 21, 3001–3016. [CrossRef]

- Colgan, D.J., Ponder, W.F. Incipient speciation in aquatic snails in an arid-zone spring complex. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2000, 71, 625–641. [CrossRef]

- Nguema, R.M., Langand, J., Galinier, R. et al. Genetic diversity, fixation and differentiation of the freshwater snail Biomphalaria pfeifferi (Gastropoda, Planorbidae) in arid lands. Genetica. 2013, 141, 171–184. [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, S.I., Peretolchina, T.E., Sitnikova, T.Ya. et al. On the genetic diversity and protoconch variability of snails of the genus Caspiohydrobia Starobogatov, 1970 (Caenogastropoda: Hydrobiidae). Ruthenica. Rus. Malac. J. 2024, 34(4), 157–169. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R., Morais, P., Antunes, C., Guilhermino, L. Factors affecting Pisidium amnicum (Müller, 1774; Bivalvia: Sphaeriidae) distribution in the River Minho Estuary: consequences for its conservation. Estuaries and Coasts. 2008, 31, 1198–1207. [CrossRef]

- Pallas, P.S. Reise durch verschiedene Provinzen des Russischen Reichs. Theil 1. Physicalische Reise durch verschiedene Provinzen des Russischen Reichs im 1768- und 1769 sten Jahren. Kayserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1771.

- Benhing, A.L. Zur Erforschung der am Flussboden der Wolga lebenden Organismen. Saratow, USSR, 1924. (In Russian).

- Borodich, N.D., Lavrov, V.L. On the bottom fauna of the Bolshoy Irgiz River. Biologia vnutrennikh vod: Informatsionnyi byulleten’. 1983, 59, 12–24. [In Russian].

- Vinarski, M.V., Karimov, A.V., Litvinov, K.V., Podolyako, S.A. The freshwater Mollusca fauna of the Astrakhan’ Reserve: the 21st century view. Trudy Astrakhanskogo Gosudarstvennogo Zapovednika, 2018, 18, 65–87. [In Russian].

- Zinchenko, T.D. The Chironomidae of the surface waters of the Middle and Lower Volga basin (Samara Region). IEVB RAS, Togliatti, Russia. 2002. (In Russian).

- Handbook on water resources of the USSR. Volume V. Lower Volga region. Moscow, USSR, 1934. (In Russian).

- Report on climate characteristics in the Russian Federation for 2020. Moscow, Russia, 2021.

- Mil’kov, F.N., Gvozdetsky, N.A. Physical Geography of the USSR. General Overview. European USSR. Caucasus. Geografgiz, Moscow, USSR, 1958. (In Russian).

- Surface Water Resources of the USSR. Volume 12. Lower Volga Region and Western Kazakhstan. Gidrometeoizdat, Leningrad, USSR. 1971. (In Russian).

- Chibilev, A.A. Steppes of Northern Eurasia. UrO RAN: Yekaterinburg, Russia. 1998. (In Russian).

- Burm, S.E., Davies, P.M. Community structure of the macroinvertebrate fauna and water quality of a saline river system in south-western Australia. Hydrobiologia. 1992, 248, 143–160.

- Golovatyuk, L.V., Mikhailov, R.A. Analysis of the spatial distribution of macrozoobenthos communities in a lowland river of the semi-desert zone. Bulletin of Tomsk State University. Series Biology. 2021, 53, 131–150. (In Russian). [CrossRef]

-

Encyclopedia of the Volgograd Region. Izdatel’: Volgograd, Russia. 2007. (In Russian).

- Zhadin, V.I. Molluscs of fresh- and brakishwaters of the USSR. The USSR Academy of Sciences Press: Moscow-Leningrad, USSR, 1952. (In Russian).

- Methodology for studying biogeocenoses of inland water bodies. Nauka Publishers: Moscow, USSR, 1975. (In Russian).

- Starobogatov, Ya.I.; Prozorova, L.A.; Bogatov, V.V.; Saenko, E.M. Molluscs. In: Identification Key to Freshwater Invertebrates of Russia and Adjacent Areas. Vol. 6.; Tsalolikhin, S.Ya., Ed. Nauka Publishers: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2004, pp. 9–492. (In Russian).

- Piechocki, A.; Wawrzyniak-Wydrowska, B. Guide to freshwater and marine mollusca of Poland. Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2016.

- Tsalolikhin, S.Ya. (ed). A Key for freshwater Zooplankton and Zoobenthos of European Russia. Vol. 2. KMK Ltd.: Moscow – St. Petersburg, Russia, 2016. (In Russian).

- Glöer, P. The freshwater gastropods of the West-Palaearctis. Vol. I Fresh- and brackish waters except spring and subterranean snails. The author: Hetlingen, Germany, 2019.

- Vinarski, M.V., Kijashko, P.V., Andreeva, S.I. et al. Atlas and catalogue of the living mollusks of the Aral and Caspian Seas. Vita Malacologica. 2024, 23, 1–124.

- Gotelli, N.J., Colwell, R.K. Estimating Species Richness. In: Biological Diversity: Frontiers in Measurement and Assessment. Oxford University Press: United Kingdom, 2011, 39–54.

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring biological diversity. Blackwell Publishing Co: Malden (MA) etc., USA, 2004.

- Shitikov, V.K., Rozenberg, G.S., Zinchenko, T.D. Quantitative hydroecology: methods of systemic identification. Samara Scientic Centre of RAS: Togliatti, Russia, 2003. (In Russian).

- Jost, L. Entropy and diversity. Oikos. 2006, 113, 363–375. [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P., Oksanen, J., Ter Braak, C.J.F. Testing the significance of canonical axes in redundancy analysis. Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 2011, 2, 269–277. [CrossRef]

- Alekin, О.А. Fundamentals of Hydrochemistry. Gidrometeoidat: Leningrad, USSR. 1970. (In Russian).

- Golovatyuk, L.V., Mikhailov, R.A. Hydrochemical state of the rivers of the semi-desert region of the Russian Plain (Yeruslan River basin, Lower Volga). Meteorology and Hydrology. 2021, 8, 75–87. (In Russian). [CrossRef]

- Bolotov, I.N., Kondakov, A.V., Konopleva, E.S. et al. Integrative taxonomy, biogeography and conservation of freshwater mussels (Unionidae) in Russia. Sci. Reps., 2020, 10, 3072. [CrossRef]

- Bespalaya, Yu.V., Vinarski, M.V., Aksenova, O.V. et al. Phylogeny, taxonomy, and biogeography of the Sphaeriinae (Bivalvia: Sphaeriidae). Zool. J. Linn. Soc., 2024, 201(2), 305–338. [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, J.G.J. The Sphaeriidae of Australia. Basteria. 1983, 47: 3–52.

- Piechocki, A. The Sphaeriidae of Poland (Bivalvia, Eulamellibranchia). Annales Zoologici of the Polish Academy of Sciences. 1989, 42, 249–319.

- Mikhailov, R.A. Species composition of freshwater mollusks in the reservoirs of the Middle and Lower Volga region. Bulletin of the Samara Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 2014, 16, 1765–1772. (In Russian).

- Mikhailov R.A. Malacofauna of different types of water bodies and watercourses of the Samara region. Kassandra LLC: Togliatti, Russia. (In Russian).

- Maio, J.D., Corkum, L.D. Relationship between the spatial distribution of freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Unionidae) and the hydrological variability of rivers. Can. J. Zool. 1995, 73, 663–671. [CrossRef]

- McMahon, R.F. Mollusca: Bivalvia. In: Ecology and classification of North American freshwater invertebrates. Academic Press: San Diego, USA, 1991, pp. 315–399.

- Wallace, R.B., Baumann, H., Grear, J.S. Gobler C. J. Coastal ocean acidification: The other eutrophication problem. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2014, 148, 1–13.

- Vaquer-Sunyer, R., Duarte, C.M. Thresholds of hypoxia for marine biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008, 105, 15452–15457. [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D. The ecological consequences of changes in biodiversity: a search for general principles. Ecology. 1999, 80, 1455–1470.

- Yachi, S., Loreau, M. Biodiversity and ecosystem productivity in a fluctuating environment: the insurance hypothesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999, 96, 1463–1468. [CrossRef]

- Holopainen, I.J. Population dynamics and production of Pisidium species (Bivalvia: Sphaeriidae) in the oligotrophic and mesohumic lake Paajarv, southern Finland. Arch. Hydrobiol. 1979, 54, 446–508.

- Vaughn, C.C., Hakenkamp, C.C. The functional role of burrowing bivalves in freshwater ecosystems. Freshw. Biol. 2001, 46, 1431–1446. [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.A., Iranawati, F., Andini, A.W. Ecology of bivalves in the intertidal area of Gili Ketapang Island, East Java, Indonesia. Aquaculture, Aquarium, Conservation & Legislation – International Journal of the Bioflux. 2018, 11, 55–56.

- Vinarski, M.V., Kantor, Yu.I. Analytical catalogue of fresh and brackish water molluscs of Russia and adjacent countries. A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of RAS, Moscow, Russia, 2016.

- Cerdeira, J.D., Otero, J., Alvarez-Salgado, X.A. et al. Multivariate substrate characterization: The case of shellfish harvesting areas in the Rías Altas (north-west Iberian Peninsula). Sedimentology. 2021, 68, 697–712.

- Bespalaya, Y.V., Travina, O.V., Tomilova, A.A., et al. Species Diversity, Settlement Routes, and Ecology of Freshwater Mollusks of Kolguev Island (Barents Sea, Russia). Inland Water Biology. 2022, 15(6), 836–849.

- Kiviat, E. Ecosystem services of Phragmites in North America with emphasis on habitat functions. AoB. Plants. 2013, 5, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Beslin, L.G. Environmental Influence on the Fish and Shellfish Biodiversity of Veli Lake in the Southwest Coast of India. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. 2013, 3, 7–12.

- Zhang, T., Yao, J., Xu, D. Et al. Effects of Short-Term Salinity Stress on Ions, Free Amino Acids, Na+/K+-ATPase Activity, and Gill Histology in the Threatened Freshwater Shellfish Solenaia oleivora. Fishes. 2022, 7(6), 346. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).