1. Introduction

Sports therapy is important for managing common orthopedic conditions in older adults, including chronic low back pain [

1,

2,

3], osteoarthritis of the lower extremities [

4,

5,

6]), articular cartilage damage [

7], chronic neck pain [

8,

9], and subacromial pain syndrome and rotator cuff injuries [

10,

11]. However, the shortage of physiotherapy and sports therapy specialists in the European Union (EU) poses a substantial burden on national healthcare systems across the EU. According to Palm et al. [

12] long waiting times due to limited physiotherapy coverage, physical distance and difficulties to reach the facilities and low perceived quality of treatments present burdens which affect elderly people – particularly in rural areas – to the greatest extent. The lack of access to therapy services leads not only to a perceived but to a measurable decline in care quality and reduced patient satisfaction, for example due to frequent therapist turnover [

12,

13].

This trend is occurring within the broader context of demographic change in the EU. The mean age of the population is 41.9 in the EU compared to 29.2 in the rest of the world leading to an increasing old age dependency ratio (people aged 65 or older compared to people between 15 and 64) [

14]. Furthermore, healthcare coverage for the older population has been shown to be dependent on the economic status and margin of healthcare expenditures [

15]. The present study was conducted as part of a digital health research and development project in a region in Germany that is strongly affected by demographic change with a predicted population decline by 13% over the next 12 years, alongside a significant increase in the proportion of elderly individuals underscoring the urgent need for innovative, digitalized healthcare solutions [

16].

The significant potential of digital healthcare is increasingly acknowledged in scientific discourse [

17].However, a holistic, patient-centered and scalable approach is lacking; according to the literature, there are also unanswered questions regarding design, architecture and use [

18]. Current implementations remain largely limited to virtualizing therapist–patient communication, leaving many aspects of digital care, particularly gamification and individualized progression measurements and the possibility to apply therapy at any time and location, untapped. To date, musculoskeletal conditions represent the primary area of application for digital remote therapy in physiotherapy, which has been one of the first implementations of digital applications in the health sector [

19].

Besides the teletherapy approach, traditional app-based home exercise programs are already in use and demonstrate that patients are generally receptive to digital therapy offerings and appreciate the perceived enhanced motivation through this new technology [

20]. Mixed reality (augmented and virtual reality) applications have shown early evidence of improved physiological function and motivation – both critical for enhancing compliance in therapy in accordance with the Technology Acceptance Model [

21] and achieving long-term health outcomes [

22]. Augmented reality (AR) is particularly suited to adapt digital training programs to individual symptoms, physical capacity, and therapeutical context. Initial results in highly specialized AR health applications show promising outcomes, such as improved balance and reduced fall risk among geriatric patients [

23] as well as short-term reductions of pain [

21]. Therefore, AR health technology shows promising potential to extend the therapeutic options regarding active therapy, which forms an important part of prevention and rehabilitation of musculoskeletal conditions [

24,

25].

Although the end goal of the development is to enhance therapeutic effectiveness and patients’ health, the foundation of a successful AR-based health application is its usability and user acceptance. These, in turn, strongly dependent on how users perceive this new technology. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), originally developed by Davis et al. [

26], provides a robust theoretical framework for understanding and predicting technology adoption in various domains, including healthcare. TAM posits that two core perceptions – perceived usefulness (the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system will enhance their performance) and perceived ease of use (the degree to which a person believes that using the system will be free of effort) – directly influence users’ attitudes and intentions to use new technologies. Since its original formulation (TAM 1), which focused on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use as primary determinants of technology adoption, the model has been expanded and refined. TAM 2 [

27] incorporates additional social influence processes (such as subjective norm, voluntariness, and image) and cognitive instrumental processes (including job relevance, output quality, and result demonstrability), offering a more comprehensive view of organizational and professional contexts. TAM 3 [

28] further integrates factors influencing perceived ease of use, such as computer self-efficacy, perceptions of external control, computer anxiety, and perceived enjoyment. Understanding and addressing these determinants during early development stages is critical for ensuring that potential users – both patients and therapists – are willing and able to use such a system. Currently, evidence on how the early development process of AR health applications is shaped by the TAM factors is sparse. Therefore, this study guided and monitored the early development of an AR-based sports therapy application focusing on factors that can improve user experience and user acceptance and should thus be central to the later stages of the development.

The present study is part of the interdisciplinary research project (“STAR” – Sports Therapy with Augmented Reality) which aims to enable the use of digital exercise programs in physiotherapeutic care through the application of AR technology. The study is grounded in the theoretical framework of the TAM and took place during the initial phases of the development process. The focus was on the development of the technical background, software and artificial intelligence model, hence focusing on the improvement of usability and user acceptance during an iterative development cycle.

With the STAR system, patients can perform sports therapy exercise programs under the guidance of a virtual therapist. To support this, comprehensive exercise catalogs are being developed for orthopedic conditions based on the latest findings in sports medicine. These catalogs are designed for the general population – regardless of age or physical condition – and are particularly relevant for the aging population (e.g., knee osteoarthritis). Therefore, a central focus of the development process is ensuring intuitive usability without requiring prior technical knowledge.

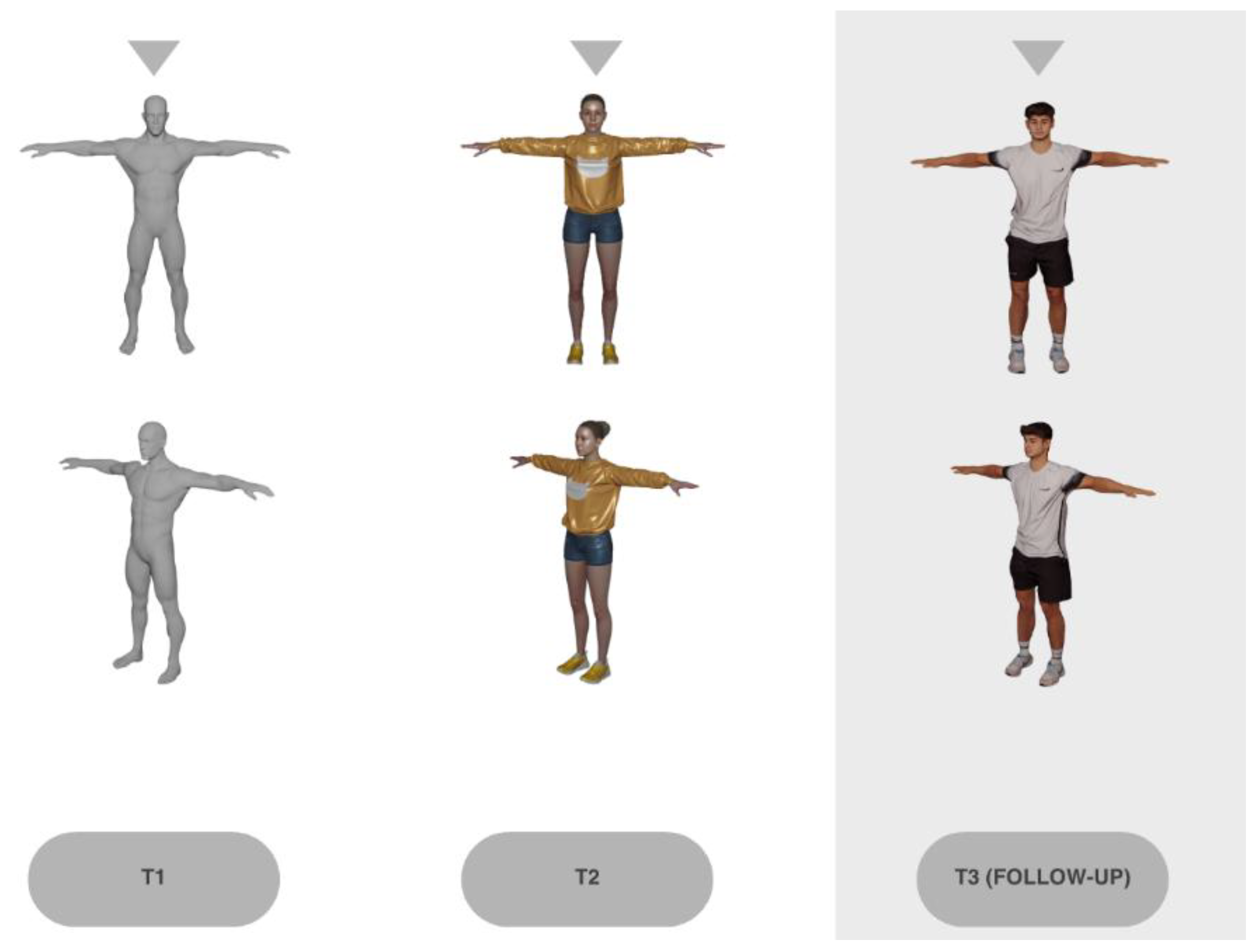

The STAR system utilizes state-of-the-art motion capture technology to evaluate patient movements and exercise performance in real time. An AI-supported system will be implemented and is intended to identify faulty or potentially harmful movement patterns, track progress, and, over time, independently integrate individualized exercise progressions or regressions into the program, approximating the therapeutic quality of one-on-one care. Both the exercises and the corresponding corrective feedback are delivered via a three-dimensional avatar (virtual therapist). One major advantage of AR technology over virtual reality (VR) is that 3D animations are projected into the user's real environment, allowing patients to remain aware of their surroundings and use training equipment if needed. This feature facilitates a smooth transition from supervised therapy sessions to independent, AR-assisted home training, effectively bridging the gap between initial therapy and ongoing independent exercise.

The development process follows a user-centered approach according to Farao et al. [

29], with the aim of maximizing benefit for both healthcare professionals and patients. The central research questions of this study stem from this objective:

First, the study investigates whether perceived system usability improves across the first two development cycles, measured using the System Usability Scale (SUS). Second, it examines changes in user acceptance based on the Technology Usage Inventory (TUI). The findings are intended to inform the target group–oriented development and optimization of the STAR system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study employs a user-centered, exploratory design featuring iterative development and evaluation. Its methodological foundation integrates elements from the Information Systems Research Framework [

30] and the Design Thinking approach [

31], as recommended by Farao et al. [

29] for health-related technologies.

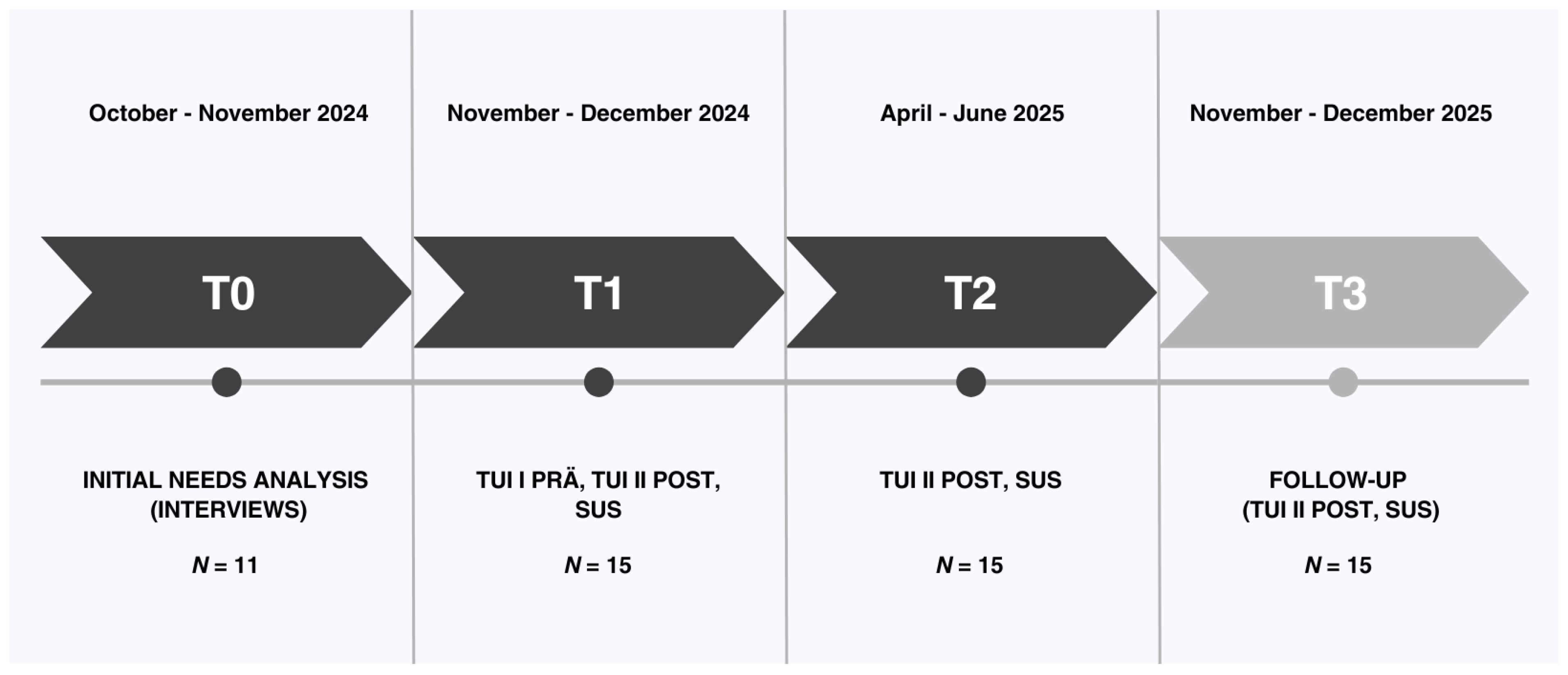

The whole STAR project is designed as a monocentric investigation and includes four data collection points (T0–T3) which are visualized in figure 1. The present study evaluated the results from the first three phases (T0, T1 and T2), which corresponded to one successive iteration of the STAR prototype, featuring functional enhancements. Data collection and analysis were guided by the principles of user-centered design as outlined in DIN EN ISO 9241-210 [

32] and included two different quantitative instruments (System Usability Scale [SUS] published by Brooke [

33] and Technology Usage Inventory [TUI] published by Kothgassner et al. [

34]).

In order to enhance the rigor and transparency of the reporting methods and results of the interview, the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) Checklist [

35] was adhered to.

Figure 1.

Timeline for the two iteration cycles. The current study took place at T0, T1 and T2.

Figure 1.

Timeline for the two iteration cycles. The current study took place at T0, T1 and T2.

2.2. Participants

For prior need analysis (T0), participants were recruited via purposive sampling: MB invited patients (aged ≥ 50 years, currently receiving treatment for chronic back pain) and physiotherapists (any age, minimum two years’ clinical experience). In total, seven patients and four physiotherapists completed interviews. No participants dropped out.

For iteration loops, participants were chosen to represent potential user groups. A total of 15 individuals from two predefined target groups were recruited by NK and JB for the study: patients (n = 10), defined by being currently enrolled in some form of physiotherapy or exercise therapy, and sports/physiotherapists (n = 5). No participants dropped out throughout the study. Since the study was exclusively about usability and user acceptance, did not include any practical exercise program and hence no measures of therapeutic quality, patients were not required to be classified within a predefined category of musculoskeletal problems. However, they needed to be enrolled in an active exercise or physiotherapy program either at a healthcare facility, at a gym or at home. Recruitment was conducted through cooperating healthcare facilities. Eligibility criteria included a minimum age of 18 years and willingness to test the system on two separate dates and complete two subsequent questionnaires. No prior digital experience or knowledge of augmented reality was required for participation. Dividing participants into two groups allowed for the comparison of professional and experience-based differences in perceived usability and user acceptance. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was reviewed and approved by the responsible ethics committee at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (protocol code: 2024-085; date of approval: 16.07.2024).

2.3. Intervention

The intervention under evaluation involves the development – with focus on the technical aspects of the system – of the STAR system with its hardware platform, the Microsoft HoloLens 2, an optical see-through AR headset that overlays digital content onto the real-world environment. The system’s core component is a virtual 3D therapist that demonstrates movement exercises and provides audiovisual support as users perform them. Although the artificial intelligence real-time feedback will only be part of the future development process of the system, an interactive pain scale is already incorporated: users are regularly prompted to report their current pain intensity. If a pain level greater than 3 (on a scale from 0 to 10) is reported, the system automatically activates a feedback algorithm that offers a simplified version of the exercise or a modified regression program with less strenuous movement variations. This allows for personalized training adaptation based on both physical capacity and the subjective perception of pain.

2.4. Testing Procedure

All tests took place in the healthcare facilities (physio therapy or sports therapy practices) in individual settings with one project employee (NK or JB) and one study participant each, so that individual support was guaranteed. Information about the testing procedure, including a written declaration of consent, was provided in advance.

First, to inform the development of the (AR)–based sports therapy system, an exploratory needs analysis (T0) was conducted prior to the formal usability study. Although this analysis did not adhere to rigorous scientific standards, it provided valuable insights on user expectations that can be integrated into the development process of the system.

A qualitative, semi-structured interview approach was selected to capture the perspectives of both end users (patients) and clinicians (physiotherapists). In October and November 2024, interviews (30–45 min each) were conducted either in person or via video conference. Participants first viewed a brief demonstration of a conceptual AR exercise module (static screenshots and narrated walkthrough), then responded to open-ended questions. The interviews were recorded for subsequent transcription.

Second, two iteration loops were conducted to test and evaluate technical functions of the STAR system (T1 and T2) separately for patients and sports/physiotherapists. Before the T1 test, the pre-version of the TUI questionnaire (TUI I) was completed. This was no longer necessary at T2. In the first test iteration (T1), the focus was on basic functionalities such as navigation, control (via hand and voice commands), and the initial display of movement exercises. At the beginning, the functionality of the application and the operation of the AR glasses were explained. The participants then put on the glasses and received verbal instructions from the project employee (e.g. “Please click on the top menu item.”) to make it easier to get started with the application. After selecting a sample exercise, the test subjects viewed the displayed exercise and tried out the various functions in parallel, such as rotating the avatar or selecting the pain scale using voice commands. After the first iteration loop, the STAR system was adapted according to user feedback. In the second iteration (T2), the system was expanded to include an interactive tutorial, improved display of the exercises including edited voiceover explanations, and had undergone further technical improvements. The procedure at T2 was therefore identical to T1 with the exception that the participants started by viewing and interacting with the tutorial first before viewing the exercises. After the second feedback of participants, the system was once again adapted.

During the two tests T1 and T2, the test subjects did not yet perform any exercises themselves, but were in an observer role in order to evaluate the technical functionality of the system. The test subjects were given sufficient time to test the application and to view all menu items and various exercise instructions. Verbal feedback that was given during the testing was noted by the project employees. At the end of the test, the participants first had the chance to give additional feedback that arised after finishing the testing. Such feedback was also noted by the project employees. Furthermore, they completed the post version of the TUI questionnaire (TUI II) and the SUS questionnaire.

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Prior Needs Analysis

The interview guidelines (in German language) were developed through a structured, multi-stage process combining theoretical groundwork and iterative refinement. The aim was to establish a tool that enabled systematic and comparable data collection while accounting for both patient and professional perspectives.

First, a focused review of the literature and existing interview instruments in the field of chronic back pain was conducted to identify relevant thematic domains and established question formats. Building on this, the project team generated additional items during a structured brainstorming phase, with emphasis on personal challenges, expectations regarding digital health applications, and potential facilitators and barriers to AR-based therapy.

The resulting pool of questions was consolidated to remove redundancies and prioritize content. Two guideline versions were then created: one for patients, focusing on therapy experiences, self-management, and openness toward digital interventions, and one for physiotherapists, concentrating on feasibility, clinical integration, and requirements for digital support. To ensure comprehensibility, technical terms were simplified and scenario-based prompts (e.g., real-time feedback during exercises) were included.

Draft versions of the guidelines were iteratively refined via structured team feedback. Adjustments concerned the order, clarity and thematic focus of questions to ensure alignment with broader project objectives.

2.5.2. System Usability Score (SUS)

The SUS captures users’ subjective assessments of a system’s usability. It is designed to be technology-agnostic, making it applicable across a broad spectrum of systems and technological contexts. The SUS comprises ten items, evenly divided into five positively worded and five negatively worded statements, each rated on a five-point Likert scale. Responses are used to derive individual item scores, which are subsequently converted into an overall SUS score ranging from 0 to 100.

The scoring procedure involves adjusting responses based on item orientation: for positively worded (odd-numbered) items, one is subtracted from the raw score, whereas for negatively worded (even-numbered) items, the raw score is subtracted from five. For instance, a response of 4 to item 1 results in a score of 3 (4 − 1), while a response of 2 to item 2 yields a score of 3 (5 − 2). The adjusted scores are then summed and multiplied by 2.5 to obtain the final SUS score.

A score of 68 or higher is generally interpreted as indicative of acceptable usability. To facilitate interpretation, previous research has introduced an adjective rating scale that qualitatively classifies SUS scores [

36]. This scale ranges from "outstanding" (90–100) to "very poor" (0–34), thereby offering a more intuitive understanding of usability outcomes.

2.5.3. Technology Usage Inventory (TUI)

The TUI is designed to evaluate an individual's intention to use a specific technology and is grounded in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Intention to use is conceptualized as a multifaceted construct influenced by a range of explanatory variables. In alignment with TAM 2 and TAM 3, the TUI incorporates both technology-specific and psychological factors. Accordingly, it expands upon the core acceptance constructs of TAM 1—such as perceived usability, usefulness, immersion, and accessibility—by including additional psychological dimensions such as technology anxiety, curiosity, interest, and skepticism.

With the exception of the technology anxiety and interest scales, all items are tailored to the specific technology under evaluation. Each scale comprises three to four items, rated using a 7-point Likert scale. Additionally, a separate ninth scale captures intention to use through three items, each rated via a 100 mm visual analog scale. Altogether, the TUI comprises 33 items and is modular in structure, allowing for the exclusion of individual scales or adaptation of item wording (e.g., incorporating the name of a specific technology).

In the present study, all scales were utilized. For each scale, item responses are summed to yield a total score, with possible values ranging from 1 (lowest expression of the construct) to 21 (for 3-item scales) or 28 (for 4-item scales). For the intention to use scale, the response position on each visual analog line is measured as the distance (in millimeters) from the right endpoint (representing complete rejection) to the middle of the cross. These three distances are then summed to generate a maximum possible score of 300.

2.6. Data Analyses

2.6.1. Qualitative Analysis

For the initial needs analysis (T0), interview recordings were transcribed verbatim, anonymized, and checked for accuracy. The analysis followed the structured coding approach described by Gioia et al. [

37]. First, the research team systematically reviewed the transcripts to identify relevant statements and insights. These excerpts were transferred as direct quotes into a shared Excel matrix, accompanied by the corresponding interview number and line reference to ensure traceability (first-order concepts). In a next step, related first-order concepts were grouped into broader categories (second-order themes), which were then further consolidated into overarching aggregate dimensions. To capture the salience of each theme, the frequency of participants mentioning a given category was documented.

Qualitative feedback at T1 and T2 was documented during and after both testing sessions. Participants were encouraged to comment spontaneously while interacting with the STAR prototype as well as to share their impressions in a brief discussion following each session. All feedback was noted in written form by project staff to ensure comprehensive capture of user perspectives.

Subsequently, the documented comments were organized thematically according to recurring areas of concern and suggestion (safety, content, technological aspects). This allowed the research team to identify central patterns across participants rather than focusing on isolated statements.

2.6.2. Quantitative Analysis

In the first step, all questionnaires were manually analyzed according to the official manuals [

38,

34]. For each participant the according questionnaire was manually scanned and all data was transferred into an excel sheet. For the SUS score, this included the scores for each of the 10 items. For the TUI it included the scores for every item and a linear scale for the items of the subscale intention to use for which a ruler was used to measure the distance from the right end of the line to the middle of the cross that the participant had marked on the line. The resulting data set was analyzed with the statistical programme SPSS statistics (version 30; IBM corp.). To answer the question whether TUI and SUS factors differ between the two testing points, paired-sample t-tests were performed. For the TUI scores Cohen's d was calculated as a measure of effect size.

However, the sample size was small meaning that statistical analyses should be viewed with caution and it should be taken into account that the interpretation is therefore limited. Thus, an additional descriptive analysis was conducted to describe improvements in the acceptance levels of the TUI and SUS scores.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the usability and user acceptance of a novel AR therapy system prototype in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. Through an iterative, user-centered development cycle involving patients and therapists, the goal was to improve the system’s usability and user acceptance, as measured by the System Usability Scale (SUS) and the Technology Usage Inventory (TUI). The decision to use two different questionnaires was made to not only capture how usability changed throughout the first iteration loop but to examine psychological factors regarding user acceptance such as skepticism and curiosity. For example, Fink et al. [

40] conducted a study on factors for user acceptance of a drone-based medication delivery system and found that user acceptance is influenced by the psychological factors curiosity and skepticism. This study showed that combining the SUS and the TUI leads to more in-depth insights on the relationship between usability, user acceptance and psychological factors.

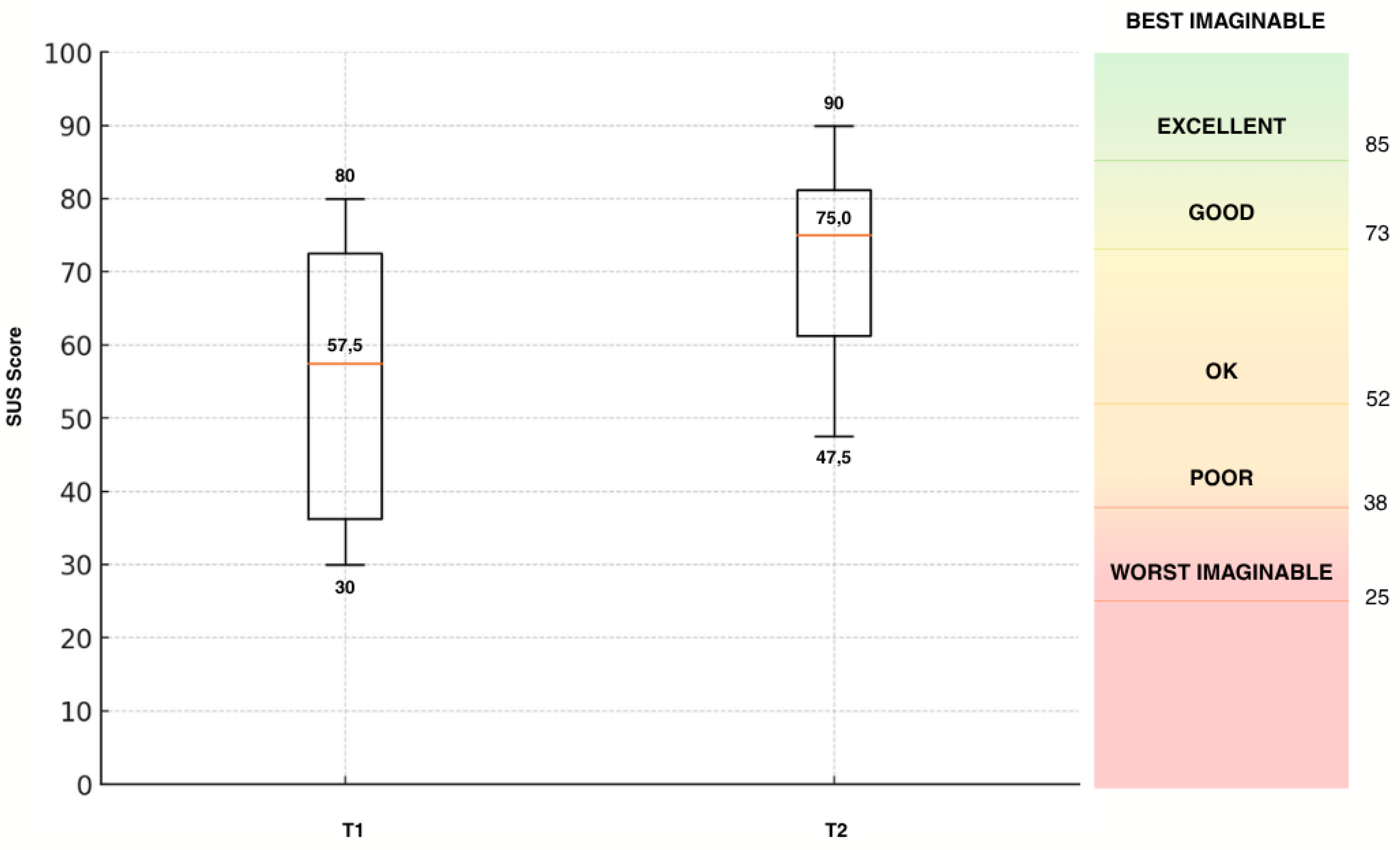

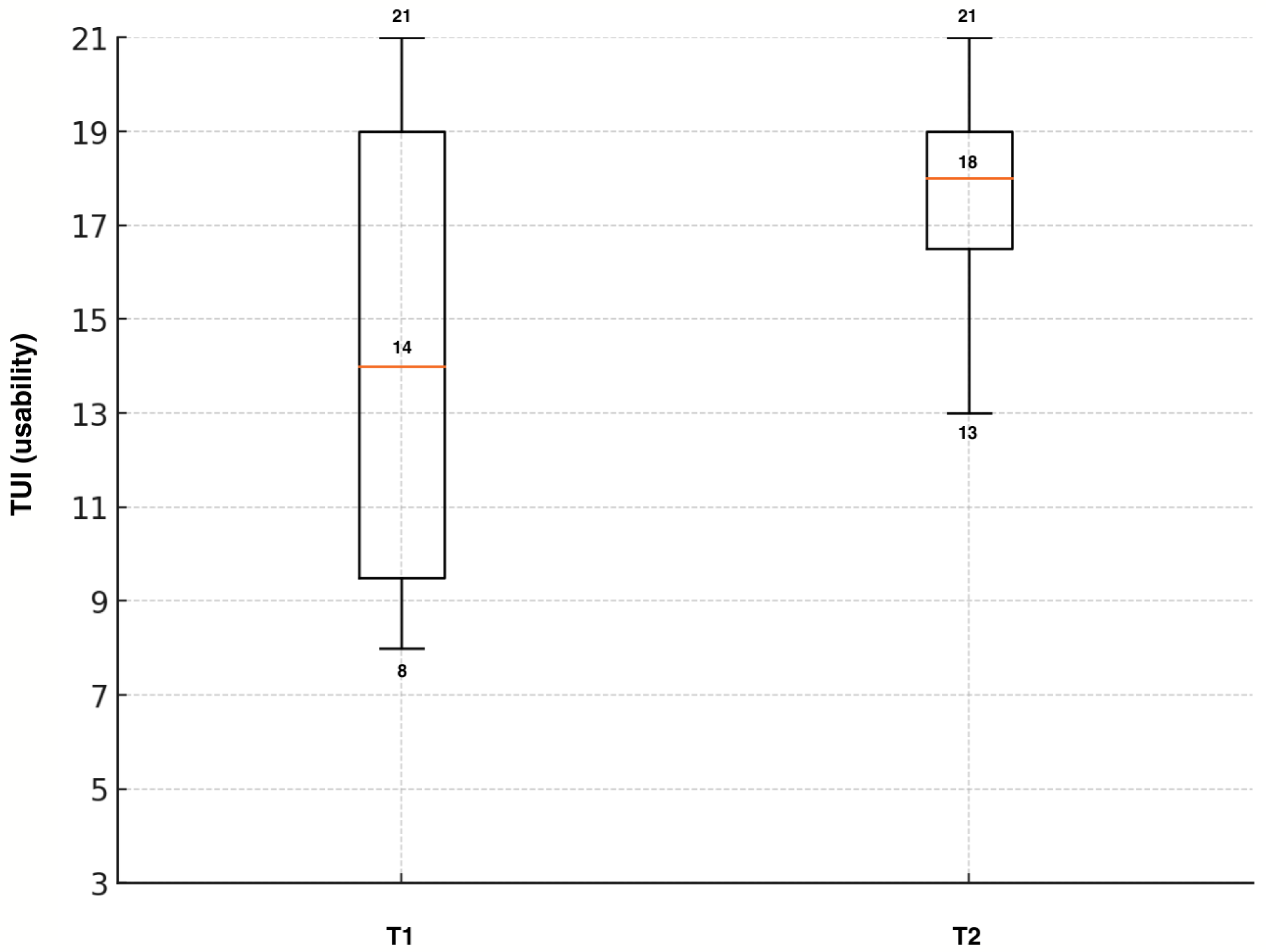

The results indicate that the aim of improving the system’s usability and user acceptance was successful: usability ratings increased over the design iteration, and final SUS scores exceeded the 68-point benchmark of average usability, approaching the “good” usability range identified in prior studies using the same hardware [

41]. Likewise, participants’ TUI responses reflected an increased user acceptance in both patient and clinician groups.

These findings align with the study aims and resonate with trends in the current literature. Recent reviews emphasize that demonstrating solid usability and acceptability is a crucial preliminary step before evaluating therapeutic effectiveness of digital and mixed reality interventions [

42,

43,

44]. Most studies done on AR in rehabilitation generally report positive user feedback, underscoring the potential of AR in rehabilitation when it is designed with the user in mind [

44]. The higher SUS and TUI scores at T2 are consistent with these patterns. For instance, Gsaxner et al. [

41] found that early medical AR applications typically achieved above-average SUS scores in the low-to-mid 70s, indicating good usability yet room for improvement. The SUS outcomes for the STAR system are in line with those values, suggesting that iterative design can indeed push usability toward the upper tiers observed in comparable AR systems. High usability is not merely a nicety; it directly supports technology acceptance. As Xu et al. [

45] demonstrated in the context of virtual reality exergames for older adults, perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness are significant predictors of users’ willingness to adopt a new rehabilitation technology.

The STAR study addressed both factors: iterative enhancements made the interface more intuitive (boosting ease of use) while also starting to tailor features to patient and therapist needs and thereby slightly enhancing perceived usefulness although this is the aspect with the most room for improvement.

When comparing the findings with similar studies on AR usability in healthcare and other digital rehabilitation tools, both commonalities and differences emerge. On the whole, the positive usability results echo those reported by Luciani et al. [

46], who tested a AR-based upper-limb rehab system based on the same AR glasses: clinicians in their study rated the system’s usability as “okay” (mean SUS ≈ 68) and expressed a high willingness to use it (4.4 out of 5 on a TAM-based willingness-to-use scale). Likewise, studies of other rehabilitation technologies, such as virtual reality exergames, have found older patient groups to be surprisingly open to using novel systems when the design is appropriately tailored. Stamm et al. [

47] reported that hypertensive seniors gave high usability ratings to VR exercise games and had intention-to-use scores comparable to those of tech-savvy reference groups. These parallels indicate that whether AR or VR, a well-designed interactive rehabilitation tool can achieve good usability and user acceptance across diverse user populations.

However, there are also notable differences and unique challenges highlighted in the literature. One concerns the hardware and interaction constraints of AR headsets. The participants in this study, like those in Blomqvist et al.’s [

48] pilot with older adults, initially experienced issues such as the device feeling heavy, difficulties with hand gesture controls, and time-consuming calibration. These factors can detract from user experience – for example, Blomqvist and colleagues observed that despite enjoying the AR training’s motivational feedback, users found the interface physically and technically challenging without further improvements. In the STAR study, these same pain points were targeted during the iterative design cycles: interface adjustments were made to simplify menu navigation and gesture control, and a tutorial was provided to mitigate setup friction. The improved SUS scores post-iteration suggest that many usability barriers due to AR’s form factor or interaction style can be overcome by responsive design changes. Nonetheless, some inherent limitations of current AR technology remain; a narrow field of view, occasional technical flaws and user fatigue are recurrent themes in AR rehabilitation research. While users generally have a positive attitude towards AR in healthcare, achieving seamless integration into therapy will require addressing these ergonomic and technical issues. Unlike screen-based or mobile rehab apps, head-mounted AR brings immersion and encumbrance, so future work should continue refining device comfort and reliability to support long-term use. This was shown by the – only non-significant – improvements in the intention to use scale showing that there is still a gap to fill before the system can be purposefully implemented in a broader pilot study on therapeutic effectiveness. Bridging this gap by foundational technical improvements will be part of the next phase of the STAR development process.

An important part of such development processes is the involvement of all potential user groups. Indeed, the literature shows that clinician buy-in is just as important as patient buy-in for new rehab technologies [

49]. Therapists must feel that a system is not only easy to use but also enhances their workflow and does not threaten patient safety or quality of care [

49]. By engaging therapists throughout development, this study addressed this need – although the sample was small – and found that both therapists and patients were positive towards features like real-time feedback which are set to be integrated soon. As stated in recent literature clinicians particularly prioritize applications that are easy to use and can be efficiently integrated into existing daily workflow processes and provide added value through increased patient engagement [

50]. Furthermore, they should provide reliable and up-to-date information that can help inform clinical decision making. The latter also includes seamless integration into the existing clinical systems such as electronic health records. Patients in turn value features that encourage sustained engagement, provide a meaningful health benefit and have minimal technical barriers hence increasing ease of use and accessibility [

51,

52].

The user-centered approach of this study helped bridge a gap noted in earlier studies: researchers have pointed out that many prototype systems stay in lab stages without clinical adoption because they lack real-world usability or fail to integrate clinician perspectives [

41,

49]. This study contributes to closing that gap, demonstrating that involving both patients and clinicians in the design loop can yield an AR application that is acceptable to all stakeholders in the rehabilitation process.

4.1. Limitations

A potential modulating factor in the changes from T1 to T2 is the experience that the participants had at the time of the second testing. All participants reported that they had never worn an augmented reality device before at T1. Therefore, at T1 not only the application but the whole hardware-software combination of the AR technology was new to the participants making it naturally hard to immediately use the system smoothly. Since users typically get used quickly to the handling of the device there is a steep learning curve that could have influenced the results at T2. This means that the improvements in usability might be partially attributed to the learning effect that already occurred during the first testing. For T3 an ad-hoc group will be implemented to mitigate the effects of experience with the new technology. Implementing an ad-hoc group has been proven to be an effective way to control the effect of familiarization throughout the iteration loops [

40].

Regarding future research it is necessary to recruit a higher number of participants, particularly more therapists. Furthermore, other health care providers like physicians and occupational therapists should be included to broaden the viewpoint and receive more comprehensive feedback from other target groups.