1. Introduction

Radiation therapy is one of the main modalities of cancer treatment, and well over half of patients receive it at some point in their care. From the first X-ray experiments in 1895 to the arrival of linear accelerators, conformal planning, and image-guided delivery, the field has grown through a long series of practical innovations rather than any single breakthrough. Conventional treatment is built around fractionation: doses are spread out over multiple sessions at standard dose rates so that healthy tissues can repair, while tumors—usually less capable of repair—accumulate damage [

1]. Even so, finding the right balance between tumor control and normal-tissue safety is still challenging. Late toxicities remain a major barrier to dose escalation, and the therapeutic window stays narrow [

2].

This enduring trade-off has motivated the search for new approaches, including the emerging concept of

FLASH radiation therapy (FRT). FLASH therapy introduces a completely different concept, delivering radiation at ultra-high dose rates (

Gy/s) over extremely short timescales. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that such delivery can spare normal tissues while preserving tumor control, a phenomenon now referred to as the

“FLASH effect” [

3,

4]. The underlying mechanisms are still under investigation, with hypotheses ranging from transient oxygen depletion to differential effects on DNA damage repair pathways [

5,

6].

If the FLASH effect can be reliably harnessed, radiotherapy could go beyond its traditional trade-off between efficacy and toxicity. The dosimetric requirements of FLASH RT are particularly demanding. The delivery of high doses (

Gy/s mean dose rate) in total irradiation times typically below 200 ms results in instantaneous dose rates greater than

Gy/s during the microsecond-long pulses. Conventional dosimeters, specifically air-filled ionization chambers, suffer from drastically reduced collection efficiency and large uncertainties (

) due to heavy

ion recombination under these high dose-per-pulse conditions [

7,

8]. To overcome these limitations, active, real-time

solid-state detectors (SSDs) with excellent spatial and temporal resolution are being rapidly developed and characterized. Their role may not be merely supportive but foundational: without accurate measurement and monitoring, clinical translation of FLASH would not be achievable.

The rise of FLASH therapy has done more than encouraging biological curiosity—it has pushed the field to rethink how accelerators and treatment systems are designed. Experimental UHDR beamlines are evolving quickly, from tweaked clinical linacs to compact cyclotrons and purpose-built research platforms, and this diversity has made it clear that we need detectors capable of performing reliably across very different beam structures and energies. Just as crucial is the creation of a solid metrological framework so that results from one institution can be meaningfully compared with those from another. With no standardized dosimetry protocols yet in place, data from different centers remain hard to align. In this landscape, solid-state detectors take on an especially important role: their speed, small footprint, and robustness position them as strong contenders for the foundation of future UHDR dosimetry standards. This review places SSD technologies within the broader technical and translational trajectory of FLASH radiotherapy and outlines the key gaps that must be closed before the technique can move into routine clinical use.

Several broad reviews have previously summarized the general challenges of UHDR dosimetry, most notably the comprehensive work of Romano et al. [

9], which discusses beam time structure, ion recombination, and the limitations of conventional detectors across accelerator types. However, that review treats solid-state detectors only briefly, as one class among many technologies. In contrast, the present manuscript provides a focused and up-to-date synthesis of solid-state detector (SSD) performance—including SiC diodes, silicon diodes, LGADs, and pixel detectors—with emphasis on saturation mechanisms, integrating-mode operation, and high-bandwidth readout electronics. By incorporating experimental results published after 2022 and by analyzing SSD behavior specifically under FLASH-relevant instantaneous dose rates, this review complements and extends the broader perspective of Romano et al., offering a detector-specific framework aimed at future UHDR dosimetry standards.

2. Defining Dosimetric Challenges in FLASH-RT

In FLASH radiotherapy, the definition of dose rate is not unique, and several conventions are used in the literature:

Average dose rate: total dose divided by irradiation time, expressed in Gy/s over the full beam-on period.

Instantaneous dose rate: dose per pulse divided by pulse duration, which can exceed Gy/s in electron beams.

Pulse-averaged dose rate: mean dose per pulse averaged over the repetition period, relevant for pulsed beams.

Dose-averaged dose rate (DADR): definitions used in proton pencil-beam scanning to capture heterogeneity in delivery.

These distinctions matter because the FLASH effect may depend not only on the average dose rate but also on the temporal microstructure of the beam.

2.1. Electron and Photon Beam Microstructure

Electron FLASH beams from clinical linacs are delivered in macropulses of a few s at repetition rates of 100–1000 Hz, with instantaneous dose rates above Gy/s. Photon FLASH beams inherit this pulse structure. Beyond the macropulse, linacs also exhibit a radiofrequency (RF) substructure: ∼30 ps bunches separated by ∼350 ps at 2856 MHz. This ns-scale modulation was resolved experimentally using a low-gain avalanche detector. While the picosecond (ps) substructure is real, the subsequent chemical and biological stages—radical diffusion, oxygen depletion, and DNA damage fixation—unfold over nanoseconds to microseconds. Because tissue integrates dose deposition over these longer windows, the fine RF bunching is effectively averaged out. The consensus is that the parameters on the s-scale (dose per pulse, pulse width, repetition rate, and mean dose rate) are biologically determinative factors.

Although the nanosecond-scale microstructure of electron and photon beams may not directly change the biological damage they produce, it may impact on how detectors behave. Space-charge buildup, ion recombination, and charge-collection dynamics all hinge on the instantaneous current within a pulse. As a result, two FLASH beams with the same mean dose rate may look quite different from a dosimetric standpoint if their temporal structure is not comparable. Therefore, detectors may need not only high saturation limits but also enough bandwidth to resolve the beam on the time scales that matter for energy deposition. Therefore, the temporal characterization is not a secondary detail—it may be relevant to defining FLASH conditions in a way that can be reproduced across systems and institutions.

2.2. Proton Beam Microstructure

Proton delivery for radiotherapy is highly dependent on the type of accelerator used, which dictates the temporal microstructure of the beam. The two primary types of accelerators produce distinct time structures, both of which are relevant for Ultra-High Dose Rate (UHDR) dosimetry:

Synchrotrons: The beam extraction from a synchrotron occurs in long macro-pulses referred to as spills. These spills typically last between to 2 seconds. Within each long spill, there is a fine temporal substructure, which consists of 10– bunches separated by approximately due to the Radiofrequency (RF) cavity bucket dynamics.

Cyclotrons (specifically, Isochronous Cyclotrons): These accelerators produce beams that are often described as quasi-continuous. The beam is inherently bunched at the accelerator’s RF frequencies, which are typically in the tens of MHz range (High Freq), resulting in nanosecond (ns) pulses separated by approximately

. Resolving this fine temporal structure requires the high-bandwidth capabilities of Solid-State Detectors (SSDs) like LGADs [

14].

These distinctions in temporal structure are crucial because detector performance, particularly the linearity and saturation of conventional dosimeters, can be heavily influenced by the instantaneous current within a pulse, even if the mean dose rate is the same across different beam types.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of beam temporal microstructures. (A) Electron Beams from Linacs: The radiation is delivered in microsecond-scale macropulses (typically 1–5 s) at a repetition rate of 100–1000 Hz. Within each macropulse, the beam consists of a train of picosecond-scale RF micropulses (bunches) separated by approximately 350 ps (for a standard 2856 MHz S-band linac). Proton Beams: (B) Isochronous cyclotrons (top) produce a quasi-continuous beam consisting of nanosecond-scale pulses at high frequencies (tens of MHz). (C) Synchrotrons (bottom) extract the beam in long spills (0.5–2 s), which also contain a nanosecond-scale substructure due to the RF cavity bucket dynamics.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of beam temporal microstructures. (A) Electron Beams from Linacs: The radiation is delivered in microsecond-scale macropulses (typically 1–5 s) at a repetition rate of 100–1000 Hz. Within each macropulse, the beam consists of a train of picosecond-scale RF micropulses (bunches) separated by approximately 350 ps (for a standard 2856 MHz S-band linac). Proton Beams: (B) Isochronous cyclotrons (top) produce a quasi-continuous beam consisting of nanosecond-scale pulses at high frequencies (tens of MHz). (C) Synchrotrons (bottom) extract the beam in long spills (0.5–2 s), which also contain a nanosecond-scale substructure due to the RF cavity bucket dynamics.

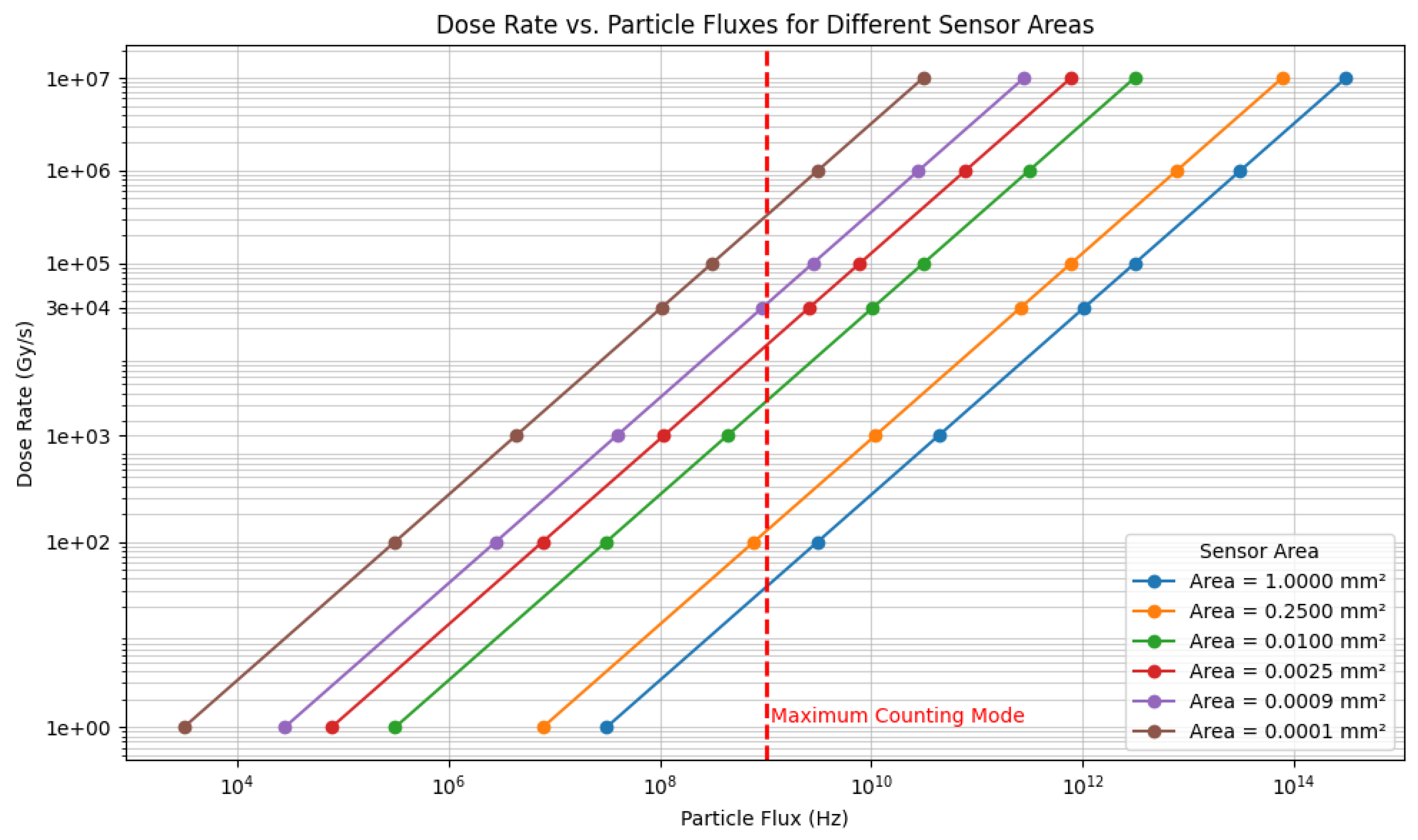

2.2.1. Maximum Dose Rate in Counting Mode

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the instantaneous Dose Rate and the particle flux (Particles/ns) traversing the sensor with different transverse areas. The relation is a

direct mathematical scaling derived from the fundamental definition of absorbed dose in water and the characteristics of the radiation beam:

The calculation uses a constant energy deposition value () corresponding to electrons, which are treated as Minimum Ionizing Particles (MIPs).

In Ultra-High Dose Rate (UHDR) dosimetry, this area-dependent scaling is critical when considering the particle counting approach. The ability of a solid-state detector (SSD) to resolve and count individual particles sets the fundamental upper limit on the dose rate measurable in this mode, as it is restricted by the detector’s signal decay time and the bandwidth of the readout electronics, causing signal merge (pile-up).

Assuming a highly optimistic, theoretical upper bound for individual particle resolution of , the graph allows us to determine the maximum operational dose rate for a counting-mode detector based on its sensor area:

A large sensor, such as the detector (relevant for SiC diodes), hits the limit at a very low rate of .

Conversely, the smallest pixel sensor, (, typical for pixel detectors), can theoretically handle rates up to (or ) while still operating within the counting limit.

This calculation can be readily scaled to other particle types or energies by substituting their respective energy deposition values.

2.3. Temporal Resolution and the FLASH Debate

A central question is whether the FLASH effect depends primarily on mean dose rate (MDR) or on instantaneous dose rate within pulses. Detector physics studies, however, note that recombination and saturation in ion chambers depend on dose per pulse (DPP) and pulse width, which can be influenced by ns bunching. Mechanistic hypotheses involving radical chemistry and transient oxygen depletion also operate on ns-

s timescales. To avoid ambiguity, studies should at minimum report

s-scale parameters: MDR, DPP, pulse width, repetition rate, and total irradiation time [

9,

21]. Having established the temporal structure and dosimetric constraints of FLASH, we now turn to the detector technologies capable of operating under these conditions.

3. Solid-State Detectors (SSDs) and Their Principles

SSDs are crucial for FLASH dosimetry because their charge collection time is typically on the order of picoseconds to nanoseconds, circumventing the ion recombination issues that plague gas-filled ionization chambers at UHDRs. This section reviews the key SSD technologies being deployed in FLASH research.

3.1. Standard Silicon Diodes vs. Silicon Carbide (SiC)

Standard silicon PIN diodes have long been used in clinical dosimetry but face saturation challenges at the highest UHDRs. The primary comparison in the field is currently between traditional Silicon (Si) and emerging Silicon Carbide (SiC) technologies.

Wide Bandgap Advantage: SiC has a wider bandgap (3.2 eV vs. 1.12 eV for Si) [

10]. This physical property results in significantly lower leakage currents. Furthermore, SiC exhibits greater radiation hardness, maintaining stability after cumulative doses that would degrade standard silicon performance [

11,

12].

Linearity and Saturation: A key limitation of standard silicon diodes at FLASH dose rates is

saturation due to the space-charge effect (where high charge density shields the electric field). SiC detectors demonstrate exceptional linearity up to much higher dose-per-pulse (DPP) values (e.g., 11 Gy/pulse) and instantaneous dose rates (up to 4 MGy/s) compared to standard Si diodes [

11].

Thermal Stability: SiC offers superior thermal stability, which is advantageous for detectors placed close to high-power FLASH beam exits [

11].

A further advantage of SiC lies in its ability to operate without bias in certain high-flux regimes. Zero-bias operation reduces electronic noise, minimizes leakage current drift, and—importantly for clinical environments—simplifies the integration of the detector into compact dosimetry probes. Several groups have demonstrated that even under unbiased conditions, SiC maintains linearity at UHDR due to its high saturation velocity and reduced charge yield [

11,

17]. In contrast, standard silicon diodes often require elevated reverse biases to counteract space-charge screening, which increases the risk of breakdown or thermal runaway during long experimental sessions. These distinctions point to a future in which SiC may serve as the foundational material for primary dosimetry standards in UHDR beamlines.

3.2. Low Gain Avalanche Detectors (LGADs)

LGADs are specialized silicon sensors featuring an internal gain layer (typically providing amplification of 10–50) designed to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio. While originally developed for single-particle tracking in high-energy physics, their application in FLASH requires a nuanced approach due to the extreme particle flux.

The Saturation Challenge: In a counting mode at low flux (e.g., < 10 Gy/s), the internal gain of an LGAD is highly beneficial for resolving single particles. However, at FLASH dose rates ( Gy/s), the particle flux is too high for counting. The simultaneous arrival of thousands of particles generates a massive charge cloud that can instantaneously saturate the gain layer and the readout electronics.

Operating as a "Fast Diode": To utilize LGADs in UHDR environments, they can be operated in current-integrating mode, similar to a standard diode. Furthermore, they are often operated at lower bias voltages. Reducing the bias suppresses the avalanche gain mechanism, effectively turning the LGAD into a standard, albeit very thin (50 m), silicon diode.

Advantages in FLASH: Even without the gain, LGADs remain valuable because of their thin active volume and fast charge collection times (tens of picoseconds). This allows them to measure the temporal structure of the beam (e.g., pulse width and shape) with high fidelity, provided the gain is managed to prevent saturation [

13,

14].

Another unique feature of LGADs is their segmentation. Strip or pixelated LGAD architectures can provide spatially resolved fluence measurements with sub-millimeter granularity while preserving nanosecond timing. This capability is particularly relevant for mapping the radial dependence of instantaneous dose rate within a macropulse—a quantity that cannot be inferred from average beam profiles. As FLASH beamlines evolve toward more complex delivery geometries, including scanned electron beams and prototype UHDR photon systems, segmented LGADs may enable novel methods of online beam monitoring and feedback control.

3.3. Miniaturized Pixel Detectors (Timepix)

Pixel detectors like Timepix are hybrid silicon sensors capable of providing high spatial resolution. Like LGADs, they must adapt to the flux conditions.

Counting vs. Integrating: Timepix is typically designed for counting mode (low flux). At FLASH rates, the pile-up is instantaneous. To be useful, these detectors must utilize

Time-over-Threshold (ToT) or integrating modes to handle the high flux [

15].

Application: Their primary value in FLASH lies in high-resolution, two-dimensional mapping of beam profiles and, when counting is possible (in beam tails), for particle track recognition and LET determination [

16].

Recent developments in Timepix3 and Timepix4 ASICs further open possibilities for UHDR dosimetry. Their continuous-readout architecture and nanosecond timestamping allow for hybrid operational modes in which pixels record time-over-threshold while maintaining partial temporal correlation across the array. Although they cannot directly count particles at FLASH intensities, the rich per-pixel information can be used to reconstruct beam uniformity, detect anomalous micro-discharges in the accelerator, or characterize the stability of the pulse train over long irradiation sequences. These capabilities suggest that pixel detectors will play a complementary role in multi-detector FLASH instrumentation systems.

3.4. Review of Experimental Results

Several groups have experimentally validated the performance of these SSDs under specific FLASH conditions.

Silicon Carbide (SiC) Studies: Significant work by

Fleta et al. has established the robustness of SiC diodes for absolute dosimetry. In their tests with 20 MeV electron beams, SiC diodes operated without external bias demonstrated linearity up to a dose-per-pulse (DPP) of

11 Gy/pulse (corresponding to instantaneous dose rates of ∼4 MGy/s) with deviations less than 3% [

11]. Furthermore, they reported exceptional radiation hardness, with a sensitivity reduction of only 0.018% per kGy of accumulated dose. Similar results were reported by

Gimondi et al.[

17] and

Guarrera et al.[

18], who tested encapsulated SiC devices in UHDR electron and proton beams. They observed linearity (

) up to

21 Gy/pulse and stable response after cumulative doses exceeding 90 kGy, confirming SiC as a superior alternative to standard silicon for high-flux reference dosimetry.

LGAD Monitoring Studies: The application of LGADs for beam monitoring has been pioneered by

Medina et al. [

19] and colleagues. Their experiments with segmented LGAD strips in clinical beams demonstrated that while counting efficiency drops due to pile-up at high fluxes, the detectors can be successfully operated in current-integrating modes to monitor beam fluence. Specifically,

Medina et al. validated thin silicon sensors (similar to LGAD structures) on UHDR electron beams, showing response linearity extending beyond

10 Gy/pulse when readout saturation is managed [

19]. Additionally,

Isidori et al. utilized LGADs to resolve the single-pulse charge deposition of a medical linac with nanosecond precision, providing the experimental basis for using these sensors to characterize the fine temporal microstructure of FLASH beams that slower detectors integrate over [

14].

4. Operational Modes and Electronic Readout

The extreme UHDR environment necessitates a shift from conventional counting-based readout to charge integration. This distinction is critical for all silicon-based sensors, including LGADs and Timepix.

4.1. High-Flux Integrating Mode

In the high-flux environment of a microsecond-long macropulse ( instantaneous dose rate), individual particles cannot be resolved.

Principle: The detector operates in an integrating mode. The total charge generated by the pulse is collected and measured.

LGAD Specifics: For LGADs, this means the "counting" capability is abandoned. The device is treated as a current source. If the bias voltage is high (nominal gain mode), the current spike can be large enough to damage readout electronics or induce non-linear space-charge effects. Therefore, operating at reduced bias (low gain) is often necessary to maintain linearity.

SiC Specifics: SiC diodes are naturally suited for this mode due to their wide bandgap and resistance to saturation effects, as discussed in

Section 3.1.

A key engineering challenge is that these transient currents frequently exceed the slew rate or input range of conventional preamplifiers. To address this, several groups are developing custom front-ends based on current conveyors, fast transimpedance amplifiers, or passive integration networks with GHz bandwidth [

9,

14]. The design of such electronics cannot be decoupled from the detector physics: the biasing scheme, depletion depth, and carrier mobility directly shape the current waveform that the electronics must process.

4.2. Low-Flux Counting Mode

Counting mode remains relevant only for:

Beam Setup/Diagnostics: Characterizing the beam at very low currents before switching to FLASH parameters.

Beam Tails: Measuring scatter or penumbra regions where the flux is sufficiently low ( Gy/s).

Single Particle Timing: Using LGADs in their high-gain mode to characterize the RF-structure of the beam, but only under conditions where the total flux is heavily attenuated (e.g. single electron mode).

5. Emerging Concepts and Future Directions

5.1. SSD Radiation Hardness Strategies

Radiation damage to silicon-based detectors is a major concern, as it changes the detector’s operational characteristics (increasing leakage current, changing depletion voltage).

Material Selection: Utilizing wide-bandgap materials like SiC significantly increases intrinsic radiation tolerance compared to Si.

Defect Engineering: For silicon devices (like LGADs), strategies include introducing impurities (carbon/oxygen) to trap lattice defects. However, SiC remains the superior candidate for longevity in high-dose clinical environments.

6. Discussion

Taken together, the studies reviewed in this work indicate that no single detector class can meet all FLASH dosimetry needs. Instead, the emerging consensus is that hybrid systems—combining SiC diodes for absolute dosimetry, LGADs for temporal profiling, and pixel detectors for spatial mapping—are required to fully characterize UHDR beams. The major challenges remain standardization, calibration at UHDR, and cross-institutional reproducibility. In this section we synthesize the performance of each SSD technology and evaluate its clinical translation potential.

The successful clinical translation of FLASH radiotherapy is currently hindered by a “dosimetry gap.” As reviewed, the transition from conventional dose rates to Ultra-High Dose Rates (UHDR) exceeding renders standard ionization chambers unreliable. The literature identifies Solid-State Detectors (SSDs) as the foundational technology to bridge this gap, but the choice of detector material and operating mode is critical.

6.1. Silicon (Si) vs. Silicon Carbide (SiC)

The most significant comparison for FLASH dosimetry is between standard Silicon and Silicon Carbide. The data reviewed consistently positions

SiC as the more robust candidate for absolute dosimetry. Its wide bandgap (3.2 eV) [

10] confers superior radiation hardness, maintaining stability after tens of kGy of accumulated dose [

11]. More importantly, SiC demonstrates superior linearity at UHDR, resisting saturation up to doses (21 Gy/pulse) where standard silicon diodes fail [

17,

21]. In addition to material selection, mechanical robustness and packaging are increasingly recognized as critical factors for UHDR detectors. Encapsulated SiC devices, for instance, demonstrate superior thermal and mechanical stability compared to bare die structures, enabling operation near beam exits or in environments with significant secondary radiation. Additionally, integrating detectors into fiber-coupled or water-equivalent housings may facilitate their deployment in small-animal irradiators and prototype clinical machines.

6.2. High-Flux Integrating Mode

There is a clear need for an appropriate electronic readout. Under FLASH conditions, the saturation of the detector often originates not from the sensor material itself, but from the inability of the readout electronics to clear the massive instantaneous charge cloud [

20]. To mitigate space-charge effects in standard diodes, high reverse bias voltages are required. However, SiC diodes inherently mitigate these saturation effects due to their high charge carrier mobility and lower signal yield per unit dose, effectively extending the dynamic range before space-charge screening occurs [

18]. For instance, SiC has shown linearity up to 21 Gy/pulse, whereas optimized silicon diodes may deviate from linearity at substantially lower doses [

17,

21].

6.3. The Role of LGADs: Specialized Timing, Not Counting

While LGADs are often highlighted for their gain, their role in FLASH is distinct. At UHDR, they cannot be used as counting detectors. Instead, they serve as specialized, ultra-fast diodes. By operating them in a current-integrating mode (often at reduced bias to mitigate saturation), researchers can exploit their thin active layers (

m) for superior temporal resolution (ps-scale) [

13,

14]. They are indispensable for resolving the beam’s temporal microstructure (RF bunches), but they do not replace SiC for robust, absolute dose quantification in a clinical setting.

Looking forward, hybrid detection systems that combine SiC for absolute charge measurement and LGADs for temporal profiling may offer the most reliable path to clinical QA in FLASH. Such systems could provide simultaneous measurement of dose-per-pulse, pulse width, and instantaneous dose-rate variations across the irradiation field—parameters currently impossible to measure with a single device.

6.4. The Necessity of Nanosecond-Resolution

A critical theme in FLASH research is the ambiguity surrounding the biological driver of the effect. To determine if the RF substructure influences outcomes, dosimetry must resolve these features. The ability of LGADs (in low-bias/fast-diode mode) and fast digitizers to reconstruct the instantaneous dose rate profile is a radiobiological necessity. Accurate correlation of biological response with physical parameters requires the detailed reporting of pulse width and microstructure, achievable only through these high-bandwidth solid-state sensors.

7. Conclusions

The implementation of FLASH radiotherapy demands a paradigm shift in dosimetry. We have reviewed how that while conventional ionization chambers fail under UHDR conditions, Solid-State Detectors (SSDs) provide the necessary physical characteristics to define the FLASH beam. Among them, Silicon Carbide (SiC) stands out as the foundational tool for absolute dose measurement due to its radiation hardness and linearity. LGADs, when adapted to integrating modes, offer the high-speed temporal resolution necessary to resolve the beam microstructure. Ultimately, the successful clinical adoption of FLASH will depend on a dosimetry framework that strategically employs these advanced SSDs to characterize both the integrated dose and the temporal dynamics of the delivery.

Ultimately, establishing consensus dosimetry standards for FLASH will require coordinated multi-institutional efforts, similar to those that standardized proton dosimetry in the early 2000s. Intercomparisons using SiC-based reference detectors, cross-calibration with calorimetric standards, and the development of open-source analysis frameworks will all be essential steps. Moreover, as UHDR delivery technologies diversify—ranging from linac-based electron beams to laser-driven sources—detectors must be validated across a broader range of energies, repetition rates, and pulse structures. Continued collaboration between detector physicists, accelerator scientists, and clinical researchers will therefore be indispensable for translating FLASH therapy safely and reproducibly into clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

During preparation of this manuscript, AI-assisted language tools were used to improve content, clarity and grammar. The author reviewed all text and takes full responsibility for the scientific content.

References

- Joiner, M.; van der Kogel, A. A brief history of fractionation in external-beam radiotherapy. Medical Physics International Journal 2022, Special Issue 08, 1001–1012. Available online: http://mpijournal.org/pdf/2022-SI-08/MPI-2022-SI-08-p1001.pdf.

- Bourhis, J.; Overgaard, J.; Baumann, M.; et al. Radiotherapy toxicities: mechanisms, management, and future directions. The Lancet 2024, 403(10419), 1234–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaudon, V.; Caplier, L.; Monceau, V.; et al. Ultrahigh dose-rate FLASH irradiation increases the differential response between normal and tumor tissue in mice. Science Translational Medicine 2014, 6(245), 245ra93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozenin, M.C.; Hendry, J.H.; Limoli, C.L. FLASH radiotherapy: The next breakthrough in radiation oncology? Clinical Oncology 2019, 31(7), 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratx, G.; Kapp, D.S. A computational model of radiolytic oxygen depletion during FLASH irradiation. Physics in Medicine and Biology 2019, 64(18), 185005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.C.L.; Ruda, H.E. Mechanisms of Action in FLASH Radiotherapy: A Comprehensive Review of Physicochemical and Biological Processes on Cancerous and Normal Cells. Cells 2024, 13(10), 835. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/13/10/835. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.R.; Rahman, M.; Zhang, R.; Williams, B.B.; Gladstone, D.J.; Pogue, B.W.; Bruza, P. Dosimetry for FLASH radiotherapy: A review of tools and the role of radioluminescence and Cherenkov emission. Frontiers in Physics 2020, 8, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, K.; Adrian, G.; Butterworth, K.; McMahon, S.J. A quantitative analysis of the FLASH radiotherapy effect in vitro. Radiotherapy and Oncology 2020, 152, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, F.; Bailat, C.; Jorge, P. G.; Lerch, M. L. F.; Darafsheh, A. Ultra-high dose rate dosimetry: Challenges and opportunities for FLASH radiation therapy. Medical Physics 2022, vol. 49, 4912–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Napoli, M. SiC detectors: A review on the use of silicon carbide as radiation detection material. Frontiers in Physics 2022, 10, 898833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleta, C.; Guardiola, C.; Henao, A.; Jiménez, M.; López-Paz, I.; Pellegrini, G.; Söderlund, M.J. State-of-the-art silicon carbide diode dosimeters for ultra-high dose-per-pulse radiation at FLASH radiotherapy. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2024, 69(9), 095015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, F.; Milluzzo, G.; Okpuwe, C.; Camarda, M.; De Napoli, M. First Characterization of Novel Silicon Carbide Detectors with Ultra-High Dose Rate Electron Beams for FLASH Radiotherapy. Applied Sciences 2023, 13(5), 2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, G.T.; Arcidiacono, R.; Arcoba, L. C.; Croci, G.; Garbini, M.; Sadrozinski, H. F. W.; Tornago, M.; Zhang, Y. Time-resolved synchrotron light source X-ray detection with Low-Gain Avalanche Diodes. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A 2024, 1070, 167990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidori, T.; McCavana, P.; McClean, B.; McNulty, R.; Minafra, N.; Raab, N.; Rock, L.; Royon, C. Performance of a low gain avalanche detector in a medical linac and characterisation of the beam profile. Physics in Medicine and Biology 2021, 66(13), 135002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, C.; Šolc, J.; Granja, C.; Bodenstein, E.; Horst, F.; Pawelke, J.; Jakubek, J. Radiation measurements using Timepix3 with silicon sensor and bare chip in proton beams for FLASH radiotherapy. Journal of Instrumentation 2024, 20(04), C04030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleter, L.; Marek, L.; Echner, G.; Ochoa-Parra, P.; Winter, M.; Harrabi, S.; Jakubek, J.; Jäkel, O.; Debus, J.; Martišíková, M. An in-vivo treatment monitoring system for ion-beam radiotherapy based on 28 Timepix3 detectors. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 15452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimondi, S.; Biasi, G.; Guarracino, M.; Petasecca, M.; Villani, G.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Gigliotti, P.; Scaringella, C.; Vanzani, M. Comprehensive dosimetric characterization of novel silicon carbide detectors with UHDR electron beams for FLASH radiotherapy. Medical Physics 2024, 51(9), 6390–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarrera, M.; Biasi, G.; Gimondi, S.; Petasecca, M.; Villani, G.; Marinelli, V. Charge collection efficiency and radiation hardness of SiC diodes under ultra-high dose-per-pulse electron beams for FLASH radiotherapy. Physics in Medicine and Biology 2024, 69(1), 015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, E.; Vignati, A.; et al. First experimental validation of silicon-based sensors for monitoring ultra-high dose rate electron beams. Frontiers in Physics 2024, 12, 1258832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, A.B.; Biasi, G.; Petasecca, M.; Lerch, M.L.F.; Villani, G.; Feygelman, V. Semiconductor dosimetry in modern external-beam radiation therapy. Physics in Medicine and Biology 2020, 65(16), 16TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Loo, B.; Tang, R.; Harken, A.; Higa, B.; Schaer, D.; Koong, A.; Schüler, E. Characterization of a diode dosimeter for UHDR FLASH radiotherapy. Physics in Medicine and Biology 2022, 67(11), 115002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).