1. Introduction

Antibiotics, capable of inhibiting or eliminating bacterial growth, are used for the prevention and treatment of bacterial infections. Since the discovery of penicillin in 1928, antibiotics have been extensively applied in human disease treatment, veterinary medicine, and aquaculture [

1], playing a significant role in protecting human health and promoting animal growth [

1]. However, during their production and application, antibiotics may enter aquatic environments through multiple pathways such as wastewater discharge, medical waste disposal, and excretion from humans and animals [

2]. Residual antibiotics in aquatic environments can disrupt the balance of microbial communities [

3], directly impact the growth and reproduction of aquatic organisms [

4], and potentially promote the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance genes and resistant bacteria [

5]. These effects would pose serious threats to ecosystem stability and human health.

Sulfamethoxazole (SMX), a broad-spectrum antibacterial agent, have been extensively used in human medicine, animal husbandry, and aquaculture. Its widespread application has led to significant residues in both aquaculture and natural water bodies [

6]. Investigations revealed positive detection rate of 78.8% in the Yellow River Basin and 100% in the Jinjiang River [

7]. Reported concentrations vary widely across different aquatic environments: averaging 8.63 ng/L in the main stream of the Yellow River [

7], reaching 18.5 ng/L in natural waters adjacent to coastal aquaculture areas [

8], and up to 2.231 μg/L in Erlong Lake [

9]. Notably, concentrations can be substantially elevated in certain waters, with levels as high as 142.6 μg/L observed in wastewater treatment plants (Kairigo et al., 2020), and even reaching 5.57 mg/L in some aquaculture systems [

10].

Currently, various physical and chemical methods such as adsorption, reverse osmosis, photocatalytic oxidation, and ion exchange have been employed to remove SMX from aquatic environments. Among them, adsorption is considered a highly promising approach due to its high removal efficiency, low operational cost, and environmental friendliness [

11].

The production of biochar from agricultural and forestry wastes represents a promising strategy for the efficient utilization of materials such as crop straws, tree branches, and processing residues. This approach not only reduces greenhouse gas emissions like CO₂ but also improves soil structure and promotes plant growth when applied to soil, offering significant economic and ecological benefits [

12]. After activation via physical or chemical methods, these biomass-derived activated carbon exhibits a higher specific surface area, greater total pore volume, and more abundant surface functional groups, enabling effective adsorption of various antibiotics and other contaminants [

13]. As a result, biomass-derived activated carbon is considered a highly efficient and environmentally friendly material for removing pollutants from aquatic environments.

Maize is a widely cultivated crop with substantial straw residue, making it a promising feedstock for biochar production. Activated carbon derived from maize straw has demonstrated effective removal of pollutants such as phenol, aniline, and pentachlorophenol [

14,

15]. However, the efficiency of these activated carbon in removing SMX from aquatic environments may be influenced by activation methods and environmental factors [

16], and studies in this regard remain limited. In this study, two types of activated carbon derived from maize straw were prepared, and their adsorption characteristics for SMX were investigated. Subsequently, the factors influencing the SMX removal efficiency were examined for the activated carbon with superior adsorption performance. This work would provide a scientific basis for the high-value utilization of maize straw and the development of effective strategies for SMX remediation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation and Activation of Biochar

Corn straw was collected and washed to remove impurities, followed by drying at 105 °C for 24 h. The dried material was then crushed and sieved through a 10-mesh screen for use as the raw feedstock. The feedstock was pyrolyzed in a tube furnace (SK3-2-10-10, Zhuochi, China) under a nitrogen atmosphere (100 mL/min), with the temperature raised to 700 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min and then maintained for 3 h. The resulting product was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature and was stored as primary product for the subsequent use.

The primary product was mixed with solid KOH at a 1:1.5 mass ratio. Deionized water was added, and the mixture was shaken at 160 rpm and 25 °C for 24 h before being dried at 105 °C [

17]. The dried powder was then heated in the tube furnace under the same nitrogen atmosphere and heating rate as described above, and maintained at 800 °C for 1 h. After cooling to room temperature, the product was washed with 1 mol/L HCl and subsequently with deionized water until the filtrate reached a neutral pH of 7. The resulting activated carbon was dried and labeled as KOH-C.

The same primary product was mixed with a 27.9% H₃PO₄ solution at a 1:6 mass ratio. The mixture then underwent identical subsequent procedures of agitation, drying, pyrolysis, acid washing, rinsing, and drying. The final product was designated as H₃PO₄-C.

2.2. Characterization of the Biomass-Derived Activated Carbons

The porous characteristics, including pore size, pore volume, and specific surface area, were evaluated using a surface area and porosity analyzer (ASAP 2460, Micromeritics, USA). Surface functional groups were identified by an electrochemical in-situ FTIR spectrometer (FTIR-850, Gangdong, China). The mass percentages of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and nitrogen (N) were determined with an elemental analyzer (vario MACRO cube, Elementar, Germany).

2.3. Adsorption Kinetics Experiments

For each activated carbon (KOH-C and H₃PO₄-C), adsorption kinetics experiments were conducted using an activated carbon dose of 250 mg/L in a 200 mL of a 10 mg/L SMX (purity 99.8%) solution in conical flasks. The flasks were shaken in the dark at 160 rpm and 25 °C. At predetermined time intervals (5, 10, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 360, 720, and 1440 min), 5 mL samples were taken and filtered through 0.45 μm membranes. The SMX concentration (

cₜ) in the filtrate was determined by measuring the absorbance at 263 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (GeneQuant 100) and referring to a standard curve. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. The adsorption capacity at time

t (

Qₜ, mg/g) was calculated using Equation (1) [

13]:

where

c0 and

cₜ represent the initial and time-

t SMX concentrations (mg/L), respectively;

V denotes the volume of the solution (L); and

m is the mass of the activated carbon (g).

The kinetic data for both activated carbons were fitted to the pseudo-first-order (Equation 2) and pseudo-second-order (Equation 3) models [

18].

Where Qₑ and Qₜ are the adsorption capacities (mg/g) at equilibrium and at time t, respectively; t is the adsorption time (min); k₁ is the pseudo-first-order rate constant (1/min); and k₂ is the pseudo-second-order rate constant (g/(mg·min)).

2.4. Adsorption Isotherm Experiments

Two sets of 300 mL conical flasks, each containing 200 mL of SMX solutions at concentrations of 5, 8, 10, 12, and 15 mg/L, were prepared. For each set, 50 mg of KOH-C or H₃PO₄-C was added. The flasks were incubated in the dark at 15 °C, 25 °C, and 35 °C with shaking for 24 h. Post-equilibrium, SMX concentrations were determined following the same procedure. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

The adsorption isotherm data of SMX on both activated carbons were fitted using the Langmuir (Equation 4) and Freundlich (Equation 5) models [

18]:

where

Qe is the adsorption capacity of SMX at equilibrium point (mg/g);

Qmax denotes the maximum adsorption capacity of SMX (mg/g);

KL represents the Langmuir equilibrium constant (L/mg);

KF is the Freundlich affinity coefficient (mg¹⁻⁽¹

/ⁿ⁾·L⁽¹

/ⁿ⁾/g);

n denotes the index related to adsorption capacity and intensity; and

Ce is the equilibrium concentration of SMX in solution (mg/L).

2.5. Investigation of Factors Influencing SMX Adsorption

A three-factor, three-level Box-Behnken design was implemented using Design-Expert 13 software to conduct response surface methodology experiments. Based on preliminary single-factor experiments, pH (

A), temperature (

B), and adsorbent dosage (

C) were selected as the influencing factors, with removal rate as the response variable (

Table 1).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Design-Expert 13 was used to conduct a multi-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) and fit a quadratic regression model. This model established the relationship between pH, temperature, adsorbent dosage, and the SMX removal rate, thereby determining the optimal level combination of the three factors and generating a predicted removal rate. Prior to analysis, the removal rate data were subjected to an arcsine square root transformation. Verification experiments was subsequently performed by conducting triplicate experiments under the identified optimal conditions. A one-sample t - test was then applied to evaluate the statistical significance of the difference between the predicted value and the actual measured values.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Biomass-Derived Activated Carbon

3.1.1. Porous Parameters

The BET surface area, Langmuir surface area, total pore volume, micropore volume, and mesopore volume of KOH-C were significantly higher than those of H

3PO

4-C. This indicates that KOH activation is more effective in enhancing the specific surface area of biochar and developing its porous structure, which is conducive to pollutant removal [

19]. Furthermore, the micropore volume accounted for 64.6% and 68.3% of the total pore volume for KOH-C and H

3PO

4-C, respectively, while the mesopore volume accounted for 30.2% and 14.6%, respectively. The absolute mesopore volume per unit mass and its relative percentage in KOH-C were both greater than those in H

3PO

4-C. This porous structure is more favorable for the adsorption of larger molecular pollutants, such as SMX [

20].

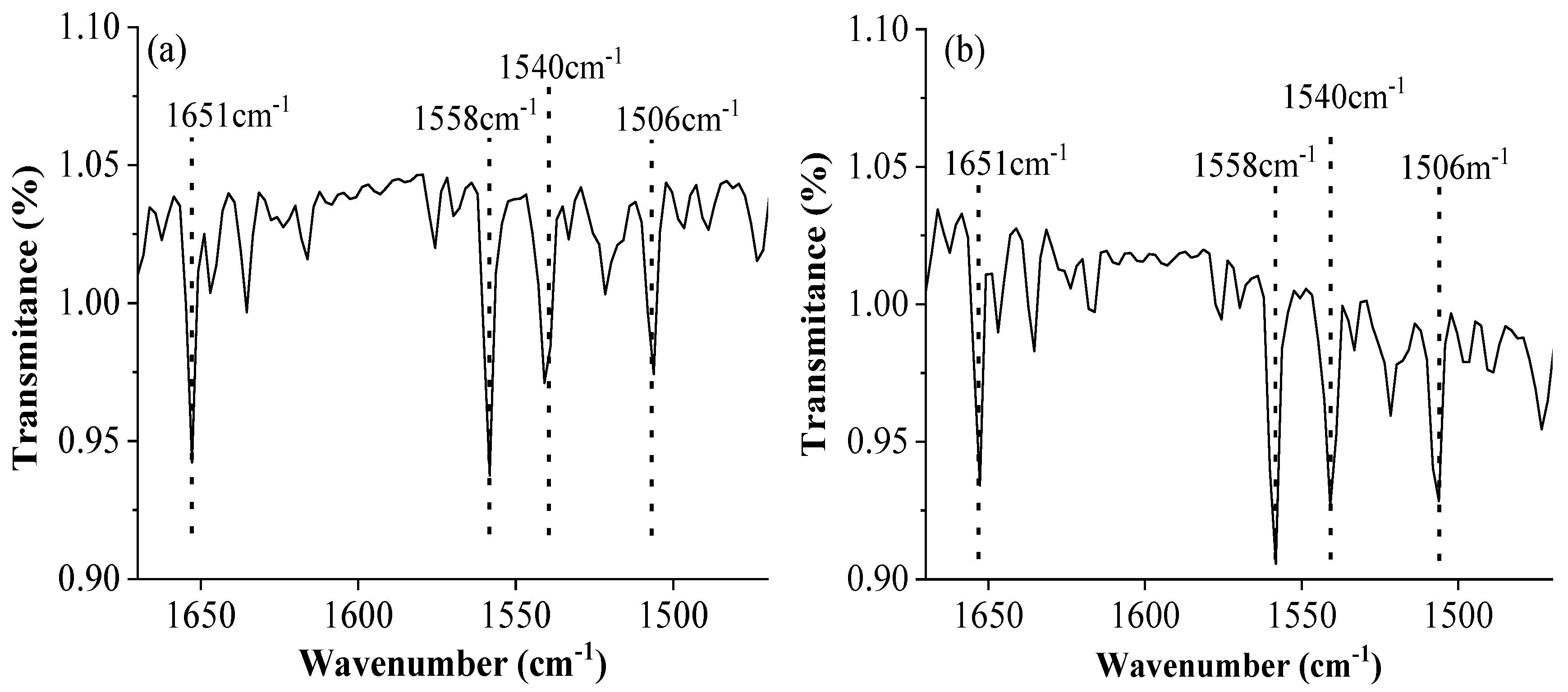

3.1.2. FTIR Characterization

The FT-IR spectra of KOH-C and H

3PO

4-C were remarkably similar (

Figure 1), indicating a comparable suite of functional groups. The absorption band at 1651 cm

-1 and 1558 cm

-1 indicated the presence of C=O and amide groups, respectively. Additionally, the peaks observed at 1506 cm

-1 and 1540 cm

-1 were attributed to the aromatic C=C vibrations and the C=N stretching in aromatic heterocycles, respectively.

3.1.3. Physicochemical Properties

KOH-C exhibited a higher carbon content but lower H/C and N/C ratios compared to H3PO4-C. This elemental composition suggests that KOH-C possesses a higher degree of carbon retention, greater aromaticity, and lower polarity, thereby contributing to its enhanced adsorption capacity [

13].

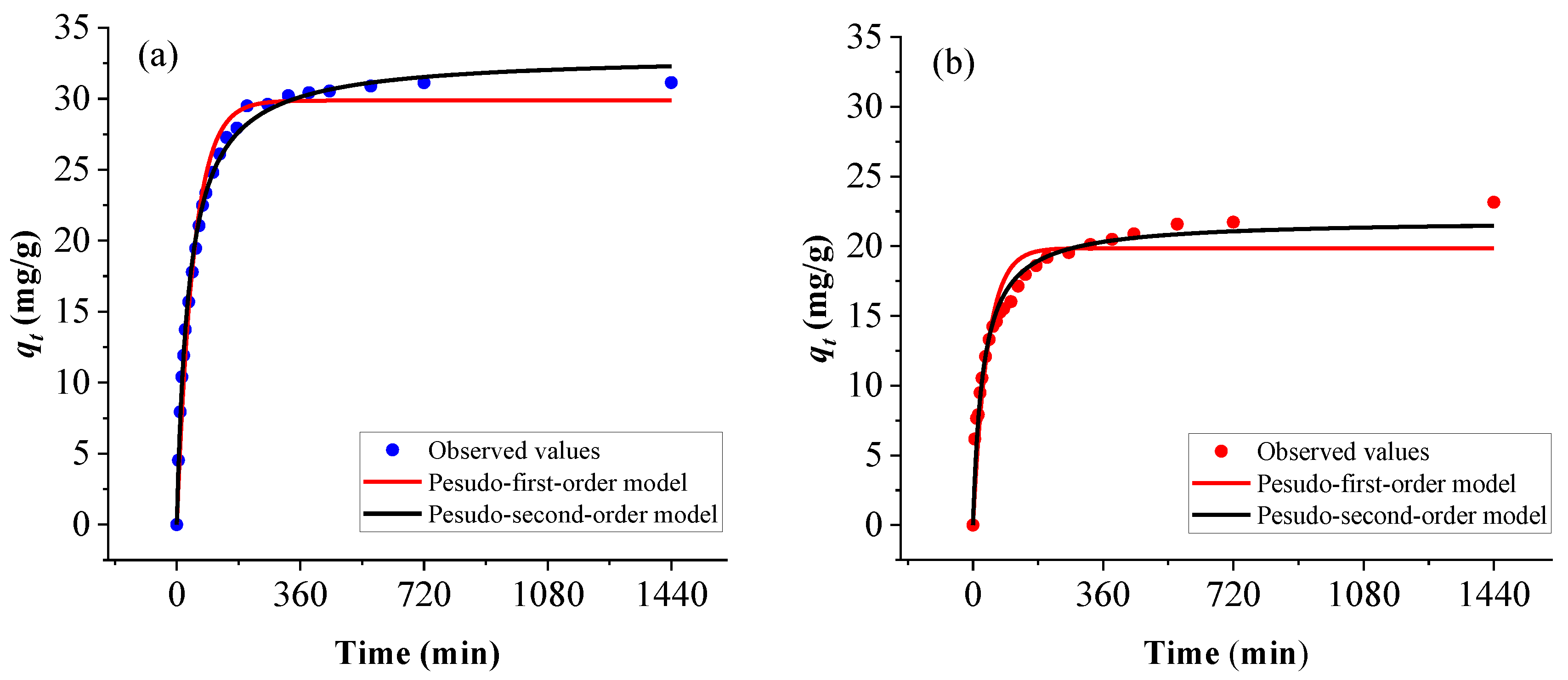

3.2. Adsorption Kinetics

As illustrated in

Figure 2, KOH-C and H

3PO

4-C exhibited similar SMX adsorption trends: rapid uptake occurred within 120 min, achieving over 80% of their respective maximum capacities, followed by a gradual approach to equilibrium around 360 min. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the abundant available active sites on the activated carbon surfaces initially, facilitating high adsorption rates. As these sites were progressively occupied by SMX molecules, the rate diminished until a balance between adsorption and desorption was established [

21].

The pseudo-second-order (PSO) kinetic model yielded higher R² values for both KOH-C and H

3PO

4-C compared to the pseudo-first-order model (

Table 4). Moreover, the experimentally derived adsorption capacities aligned more closely with the theoretical values calculated from the PSO model. This indicates that the adsorption process is best described by the PSO model, suggesting that chemisorption played a dominant role [

22]. Both

Figure 2 and

Table 4 further reveal that KOH-C possessed higher experimental and theoretical maximum adsorption capacities for SMX than H

3PO

4-C. This superiority is consistent with its larger specific surface area and mesopore volume, as presented in

Table 2.

Table 2.

The porous parameters of KOH-C and H3PO4-C.

Table 2.

The porous parameters of KOH-C and H3PO4-C.

| Borous parameters |

KOH-C |

H3PO4-C |

| BET surface area (m²/g) |

469.18 |

85.40 |

|

| Langmuir surface area (m²/g) |

746.17 |

204.6 |

|

| Total pore volume (cm³/g) |

0.268 |

0.082 |

|

| micropore volume (cm³/g) |

0.173 |

0.056 |

|

| mesoporous volume (cm³/g) |

0.081 |

0.012 |

|

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of KOH-C and H3PO4-C.

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of KOH-C and H3PO4-C.

| Adsorbent type |

N(%) |

C(%) |

H(%) |

N/C |

H/C |

| KOH-C |

0.9061 |

72.38 |

1.669 |

0.013 |

0.023 |

| H3PO4-C |

0.7079 |

32.63 |

2.266 |

0.022 |

0.069 |

Table 4.

Adsorption kinetic parameters of SMX on KOH-C and H3PO4-C.

Table 4.

Adsorption kinetic parameters of SMX on KOH-C and H3PO4-C.

| Adsorbent type |

Qeobserved

(mg/g)

|

Pesudo-first-order model |

|

Pseudo-second-order mode |

|

Qe,1(mg/g)

|

K1(min-1)

|

R2

|

Qe,2(mg/g)

|

K2(g/(mg·min))

|

R2

|

| KOH-C |

31.13 |

29.87 |

0.0205 |

0.9805 |

|

33.07 |

0.000858 |

0.9964 |

| H3PO4-C |

23.15 |

19.86 |

0.0252 |

0.9026 |

|

21.89 |

0.001640 |

0.9729 |

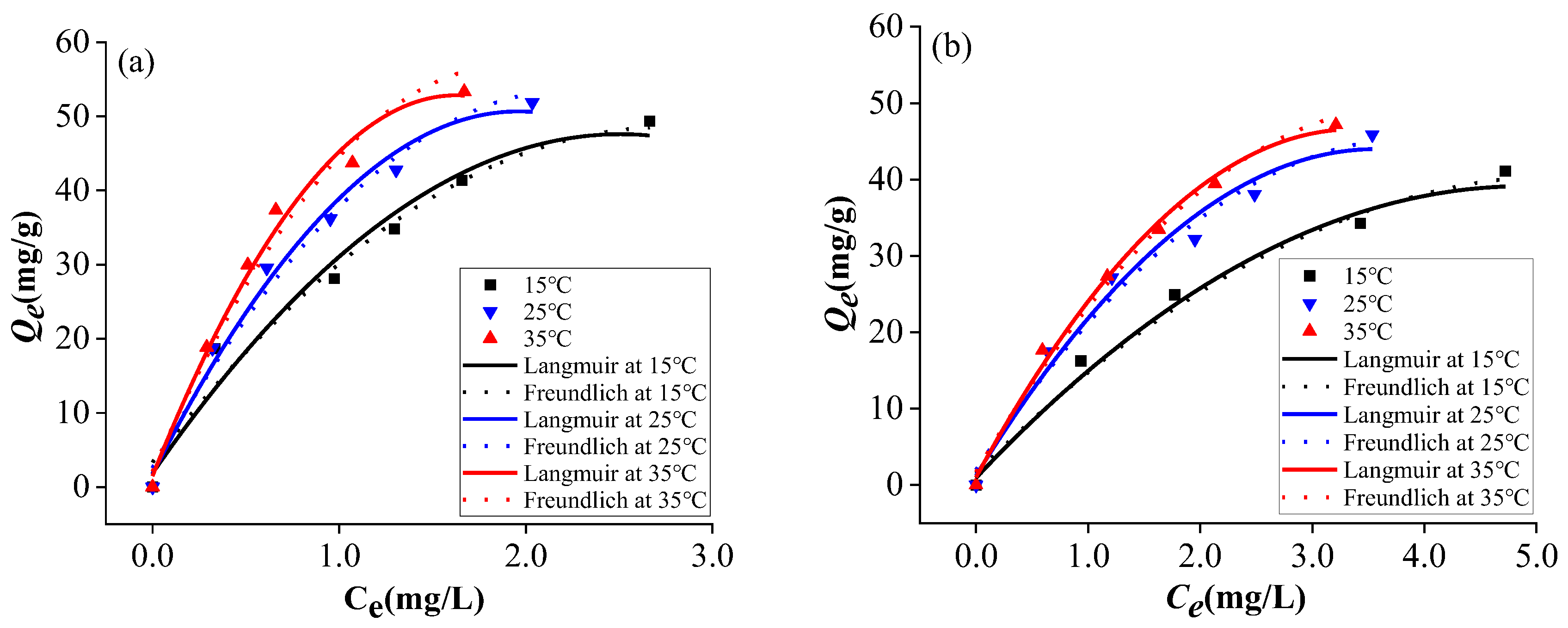

3.3. Adsorption Isotherms

The adsorption of SMX onto KOH-C and H₃PO₄-C was well fitted by both Langmuir and Freundlich models, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 5. The high

R² values demonstrated that both models could effectively represent the adsorption behavior. Nonetheless, the Langmuir model exhibited a markedly superior fit (with a higher correlation coefficient) compared to the Freundlich model. This suggests that the adsorption of both types of activated carbons on SMX is more akin to monolayer adsorption (

Table 5) [

18,

23]. The Freundlich parameter 1/n was less than 1 in all cases, suggesting that SMX adsorption was a favorable process [

24]. Furthermore, the increase in

KF values with temperature for both activated carbons indicated an endothermic adsorption process, which was enhanced at elevated temperatures [

20,

25].

The negative standard Gibbs free energy (Δ

G < 0) indicates that the adsorption of SMX onto the biomass-activated carbons is spontaneous within the temperature range of 15 ℃ to 35 ℃ (

Table 6). However, Δ

G decreases with increasing temperature, indicating a reduction in spontaneity. The positive entropy change (Δ

S > 0) indicates an increase in the disorder of the system during the adsorption process. Additionally, the positive enthalpy change (Δ

H > 0) suggests that the adsorption process is endothermic.

3.4. Analysis of the Response Surface Test Results

3.4.1. Model Fitting and Analysis of Variance

The full factorial BBD matrix for 3 factors (pH, temperature, and adsorbent dosage) and their responses (SMX removal rate) were represented in (Tabel 6). A quadratic polynomial regression model (

R² =0.9198) was obtained based on the results:

As shown in the analysis of variance (

Table 7), the regression model was highly significant (

P < 0.01). The non-significant lack-of-fit term (

P > 0.05) further validated the model’s reliability. Among the quadratic terms, the interactive effects of pH-dosage and pH-temperature significantly influenced SMX removal efficiency (

P < 0.05). Moreover, the main effects of temperature and dosage, along with the quadratic term of dosage, exhibited highly significant impacts (

P < 0.01). These results demonstrate that the model can effectively predict the SMX removal rate by KOH-C across varying conditions of pH, temperature, and adsorbent dosage.

Table 7.

Box-Behnken experimental design and SMX removal rates.

Table 7.

Box-Behnken experimental design and SMX removal rates.

| Run No. |

pH |

Temperature (℃) |

Adsorbent dosage (mg) |

Removal rate (%) |

| 1 |

4 |

15 |

175 |

97.89 |

| 2 |

10 |

15 |

175 |

98.96 |

| 3 |

4 |

35 |

175 |

99.96 |

| 4 |

10 |

35 |

175 |

99.00 |

| 5 |

4 |

25 |

50 |

98.35 |

| 6 |

10 |

25 |

50 |

94.41 |

| 7 |

4 |

25 |

300 |

98.85 |

| 8 |

10 |

25 |

300 |

99.54 |

| 9 |

7 |

15 |

50 |

96.64 |

| 10 |

7 |

35 |

50 |

98.39 |

| 11 |

7 |

15 |

300 |

96.82 |

| 12 |

7 |

35 |

300 |

99.81 |

| 13 |

7 |

25 |

175 |

99.13 |

| 14 |

7 |

25 |

175 |

99.23 |

| 15 |

7 |

25 |

175 |

99.78 |

| 16 |

7 |

25 |

175 |

99.12 |

| 17 |

7 |

25 |

175 |

98.98 |

Table 8.

ANOVA for response surface quadratic model for removal of SMX.

Table 8.

ANOVA for response surface quadratic model for removal of SMX.

| Source |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F-value

|

P-value

|

| Model |

0.0445 |

9 |

0.0049 |

8.91 |

0.0044**

|

|

A-pH |

0.0014 |

1 |

0.0014 |

2.58 |

0.1526 |

|

B-Temperature |

0.0128 |

1 |

0.0128 |

23.18 |

0.0019**

|

|

C-Adsorbent dosage |

0.0099 |

1 |

0.0099 |

17.79 |

0.0039**

|

| AB |

0.0038 |

1 |

0.0038 |

6.91 |

0.0340*

|

| AC |

0.0056 |

1 |

0.0056 |

10.07 |

0.0156*

|

| BC |

0.0015 |

1 |

0.0015 |

2.78 |

0.1391 |

|

A² |

0.0001 |

1 |

0.0001 |

0.1697 |

0.6927 |

|

B² |

<0.0001 |

1 |

<0.0001 |

0.0528 |

0.8248 |

|

C² |

0.0090 |

1 |

0.0090 |

16.30 |

0.0050**

|

| Residual |

0.0039 |

7 |

0.0006 |

|

|

| Lack of fit |

0.0020 |

3 |

0.0007 |

1.43 |

0.3575 |

| Pure error |

0.0019 |

4 |

0.0005 |

|

|

| Cor total |

0.0483 |

16 |

|

|

|

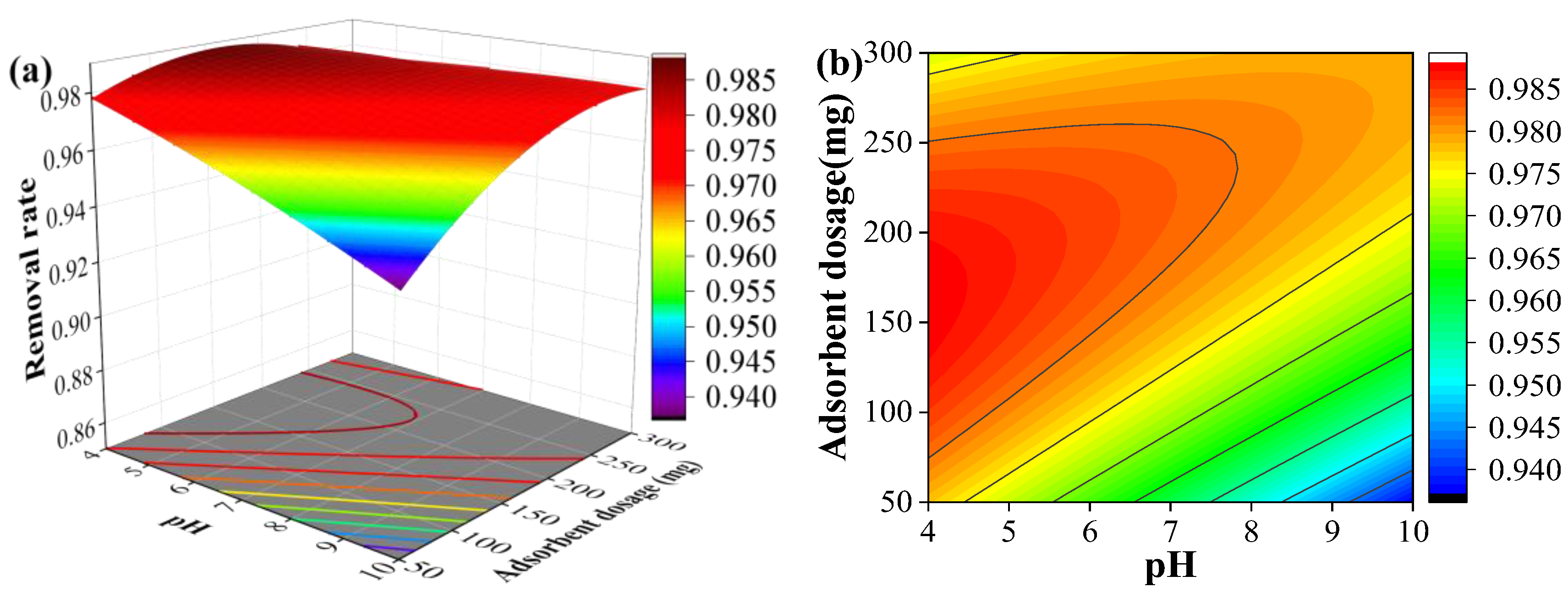

3.4.2. Analysis of Interaction Effects

Figure 4 illustrates the interactive effects of temperature and pH on the adsorption efficiency of SMX at a fixed adsorbent dosage of 175 mg (0.875g/L). Within the pH range of 4 - 6, the SMX removal rate increased markedly with rising temperature. In contrast, at pH values exceeding 6, the elevation of temperature did not significantly enhance the SMX removal efficiency. Across all tested temperature ranges, an increase in pH resulted in a decrease in the SMX removal rate.

Figure 5 demonstrates the combined influence of adsorbent dosage and pH on the adsorption of SMX at a constant temperature of 25 °C. For all pH ranges investigated, the SMX removal efficiency increased with higher adsorbent dosage. This enhancement is primarily attributed to the increased number of available adsorption active sites provided by the greater quantity of activated carbon. Within the dosage range tested, the SMX removal rate decreased as the pH increased.

3.4.3. Determination of the the Optimal Conditions for SMX Adsorption

Within the tested ranges of the factors, the optimal conditions for SMX adsorption on KOH-C were determined as follows: pH of 4, a temperature of 35 °C, and a dosage of 198.4 mg (equivalent to 0.992 g/L). Under these conditions, the predicted removal rate reached 99.9%. Subsequently, triplicate validation experiments were conducted, yielding an average removal efficiency of 99.8%. The negligible difference (0.1%) between the predicted and experimental values was confirmed to be statistically insignificant by a one-sample t-test (P = 0.423). These results demonstrate the high reliability of the fitted model.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Activation Methods on Biomass-Derived Activated Carbon

The adsorption of pollutants by biomass-derived activated carbon is primarily attributed to its abundant pores, diverse surface functional groups, and high specific surface area [

26]. However, the adsorption capacity of biochar produced via conventional methods for antibiotics and other contaminants is often limited due to its relatively small specific surface area, limited pore volume, and high ash content [

13]. In contrast, chemical activation with agents such as KOH, H₃PO₄, HNO

3, HCl, and ZnCl₂ can significantly modify these key characteristics, thereby enhancing adsorption performance [

20,

27,

28].

As demonstrated by Liang et al. [

28], different activation methods employ distinct pore-forming mechanisms, which profoundly influence the resulting activated carbon structure and adsorptive properties. H₃PO₄ works by hydrolyzing cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin and forming cross-links with biopolymers. This process inhibits the contraction and collapse of pores at high temperatures, ultimately fostering a porous structure [

28]. KOH activation, meanwhile, involves a two-stage mechanism. At moderate temperatures, it reacts with certain compounds in the biomass, initiating radial activation that creates numerous micropores. At subsequent higher temperatures, this radial activation continues, while intense reactions within the micropores lead to pore widening, a process known as transversal activation [

29].

In this study, the removal of SMX by both KOH-C and H₃PO₄-C was better described by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. Furthermore, the Langmuir model provided a fit for the SMX adsorption isotherms that was comparable to the Freundlich model across the tested temperatures. However, the KOH-C exhibited a superior specific surface area and pore structure compared to the H₃PO₄-C. Consequently, KOH-C demonstrated a higher SMX adsorption capacity than H₃PO₄-C. Although the activation efficiency achieved with KOH in this work was lower than that reported in other studies [

30,

31], the resulting activated carbon still demonstrated satisfactory SMX adsorption. Consequently, further investigation into optimizing the activation conditions is wanted.

4.2. Influencing Factors of SMX Removal by Biomass-Derived Activated Carbon

(1) Influence of pH

Solution pH significantly influences the ionization state of SMX: cationic (pH < 1.8), neutral (pH 1.8 - 5.6), or anionic (pH > 5.6) [

27]. It also determines the surface charge of activated carbon, consequently influencing the removal rate of contaminants. The surface of activated carbons is positively charged when the solution pH is below its point of zero charge (pH

pzc). Conversely, it becomes negatively charged at pH above the PZC [

32]. Therefore, an increase in pH generally enhances electrostatic repulsion between SMX and the activated carbon surface, leading to diminished removal efficiency [

32,

33]. However, our experimental results diverge from this general trend, as no significant reduction in SMX removal was observed with increasing pH. This phenomenon suggests that other mechanisms, such as pore diffusion and π-π conjugation effects, were predominant and effectively masked the influence of electrostatic repulsion under the tested conditions [

20].

(2) Influence of temperature

Temperature generally exerts a significant influence on the adsorption of antibiotics by activated carbon. For instance, the adsorption capacity and efficiency of norfloxacin onto corn straw-derived activated carbon increased progressively within the temperature range of 5 °C to 45 °C (Tan et al., 2018). Similar trends were observed for the adsorption of tetracycline and ciprofloxacin onto KOH-activated biochar [

34], SMX and ciprofloxacin onto bagasse biochar [

25], SMX onto KOH- or H₃PO₄-activated corn cob biochar [

27], sulfonamide antibiotics onto HNO₃-activated corn straw biochar, and SMX onto alfalfa-derived biochar [

32]. The primary reason may be that the adsorption process is endothermic, and elevated temperature enhances the hydrophobic interaction between the contaminant and activated carbon or biochar [

35]. In addition, increased temperature raises the kinetic energy of both SMX and solvent molecules, accelerating the diffusion of SMX to the activated carbon or biochar surface and into its pores, thereby facilitating contact with active sites [

35].

In the present study, at an activated carbon dosage of 175 mg (0.875 g/L), the removal rate of SMX increased markedly with rising temperature in the pH range of 4 - 6. In contrast, at pH values exceeding 6, the effect of temperature on SMX removal was less pronounced. This attenuation can be mainly attributed to the increased negative surface charges on both SMX and activated carbon at higher pH levels, which intensify electrostatic repulsion and thereby counteract the positive effect of temperature elevation[

32,

33].

(3) Influence of Dosage

For a fixed initial SMX concentration, a higher activated carbon dosage generally results in greater contaminant removal efficiency. However, the incremental gain in adsorption efficiency diminishes once the dosage exceeds a certain threshold [

32]. Therefore, the activated carbon dosage should be optimized according to the specific SMX concentration and water quality parameters to achieve cost-effectiveness in practical applications.

5. Conclusions

Compared to H3PO4-C, KOH-C exhibited a larger specific surface area and superior pore characteristics, resulting in a significantly enhanced capacity for adsorbing SMX. A response surface methodology study was employed to investigate the influencing factors on SMX removal by KOH-C. The results demonstrated that: 1) A quadratic regression model effectively described the relationships between pH, temperature, dosage, and SMX removal efficiency (R² =0.9198); 2) The interactive effects of pH-dosage and pH-temperature were significant (P < 0.05), while the main effects of temperature and dosage, along with the quadratic term of dosage, were highly significant (P < 0.01) on SMX removal; 3) A lower pH, a higher temperature, and a larger dosage were favorable for SMX removal, with a theoretical maximum removal efficiency of 99.9% .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and J.Z.; formal analysis: D.J.; funding acquisition: D.J. and J.X.; investigation: X.L., D.P., Z.Z., Z.N. and Y.Y.; methodology: X.L. and J.Z.; project administration: J.Z.; supervision: J.X. and J.Z.; writing—original draft: X.L.; writing—review and editing: J.X., J.Z., X.Y. and Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2025QC306, ZR2022ME100, ZR2023MC171).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author if needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Mr. Wenhao Dong and Mr. Yu Zhang for their valuable suggestions and assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Lei, L.; Ma, W.; Ma, C.; Song, L.; Chen, J.; Pan, B.; Xing, B. Cation-pi interaction: A key force for sorption of fluoroquinolone antibiotics on pyrogenic carbonaceous materials. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51, 13659–13667. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, W.; Cui, H.; Jia, X.; Huang, X. Occurrence and ecotoxicity of sulfonamides in the aquatic environment. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 820, 153178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, X.; Huang, Z.; Ohore, O. E.; Yang, J.; Peng, K.; Li, S.; Li, X. Impact of antibiotics on microbial community in aquatic environment and biodegradation mechanism: A review and bibliometric analysis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 66431–66444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbhuiya, N. H.; Adak, A. Determination of antimicrobial concentration and associated risk in water sources in West Bengal State of India. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2021, 193, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S.; Bhat, M. A.; Ahmed, S.; Siddiqui, W. A. Antibiotic residue contamination in the aquatic environment, sources and associated potential health risks. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2024, 46, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shi, W.; Liu, W; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Hu, J.; Ke, Y.; Sun, W.; Ni, J. A duodecennial national synthesis of antibiotics in China’s major rivers and seas. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 615, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Wang, K.; Yang, F.; Zhuang, T. Antibiotic pollution of the Yellow River in China and its relationship with dissolved organic matter. Distribution and Source Identification Water Research 2023, 235, 119867. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Yu, M.; Hong, M.; Sun, D. Residual characterization of multi-categorized antibiotics in five typical aquaculture waters. Ecology and Environment 2021, 20(5), 934. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Gao, H.; Yu, H. Pollution characteristics of four-type antibiotics in typical lakes in China. China Environmental Science 2021, 41, 4271–4283. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Ma, X.; Liao, X.; Cheng, S.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H. Characteristics of algae-derived biochars and their sorption and remediation performance for sulfamethoxazole in marine environment. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 430, 133092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zimmerman, A. R.; Chen, H.; Gao, B. Ball milled biochar effectively removes sulfamethoxazole and sulfapyridine antibiotics from water and wastewater. Environmental Pollution 2020, 258, 113809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, R.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, A. Soil and biochar: Attributes and actions of biochar for reclamation of soil and mitigation of soil borne plant pathogens. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 2024, 24, 1924–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayin, F; Akar, S. T; Akar, T. From green biowaste to water treatment applications: Utilization of modified new biochar for the efficient removal of ciprofloxacin. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2021, 24, 100522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Shang, H.; Cao, Y.; Yang, C.; Hu, W.; Feng, Y.; Yu, Y. Influence of adsorption sites of biochar on its adsorption performance for sulfamethoxazole. Chemosphere 2023, 326, 138408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Pan, Y.; Xun, L.; Kou, W. Preparation, characterization and adsorption performance of corn straw biochar. Renewable Energy Resour 2024, 42, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, F.; Sun, B.; Song, Z.; Zhu, L.; Qi, X.; Xing, B. Physicochemical properties of herb-residue biochar and its sorption to ionizable antibiotic sulfamethoxazole. Chemical engineering journal 2014, 248, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, J.; Ma, Z. Preparation of activated carbon from gasified rice husk char activated by KOH and its adsorption properties. Biomass Chemical Engineering 2021, 55, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kzhang, A; Li, X; Xing, J; Xu, G. Adsorption of potentiallytoxic elements in water by modified biochar. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2020, 8, 104196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Zhu, F.; Li, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, T. The mechanism of Zn-Fe bimetal/biochar composite catalyst for the activation of persulfate in pollutant degradation. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae 2025, 45, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Ma, Y.; Yao, G. Effect of KOH activation on the properties of biochar and its adsorption behavior on tetracycline removal from an aqueous solution. Environmental Science 2022, 43, 5635. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Shen, X.; Domene, X.; Alcañiz, J. M.; Liao, X. Comparison of biochars derived from different types of feedstock and their potential for heavy metal removal in multiple-metal solutions. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 9869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y.; Tan, X.; Zeng, G.; Li, X.; Liang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yan, Z.; Cai, X. Facile synthesis of Cu(Ⅱ) impregnated biochar with enhanced adsorption activity for the removal of doxycycline hydrochloride from water. Science of the Total Environment 2017, 592, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Jin, H.; She, D. Mechanism of a double-channel nitrogen-doped lignin-based carbon on the highly selective removal of tetracycline from water. Bioresource Technology 2022, 346, 126652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Chai, H.; Yu, Z.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Shen, L.; Li, J.; Ye, J.; Liu, D.; Ma, T.; Gao, D.; Zeng, W. Behavior and mechanism of cesium biosorption from aqueous solution by living synechococcus PCC7002. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Niu, Y.; Dong, K.; Wang, D. Removal mechanism of typical antibiotics by bagasse biochar. Technology of Water Treatment 2022, 48, 52–56+61. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Liu, T.; Zhang, C.; Cai, L. Preparation and optimization of loquat seeds based on microporous carbon via response surface method and study on its selective adsorption properties. Chinese Journal of Tropical Crops 2018, 39, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Bao, Y.; Wen, Q.; Wu, Y.; Fu, Q. Effects of H3PO4 modified biochar on heavy metal mobility and resistance genes removal during swine manure composting. Bioresource Technology 2022, 346, 126632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Hu, X. Sequential activation of willow wood with ZnCl2 and H3PO4 drastically impacts pore structure of activated carbon. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 221, 119387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hendawy, A. An insight into the KOH activation mechanism through the production of micro-porous activated carbon for the removal of Pb2+ cations. Applied Surface Science 2009, 255, 3723–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Ma, J.; Li, Z.; Xia, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y. Highly enhanced adsorption performance of tetracycline antibiotics on KOH-activated biochar derived from reed plants. Royal Society of Chemistry Advances 2020, 10, 5066–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, B.; Xie, Z.; Tang, J. Enhanced adsorption performance of tetracycline in aqueous solutions by KOH-modified peanut shell-derived biochar. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2023, 13, 15917–15931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. K.; Kan, E. Effects of pyrolysis temperature on the physicochemical properties of alfalfa-derived biochar for the adsorption of bisphenol A and sulfamethoxazole in water. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fang, C.; Wang, Q.; Chu, Y.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xue, X. Sorption of tetracycline on biochar derived from rice straw and swine manure. Royal Society of Chemistry Advances 2018, 8, 16260–16268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, F.; Li, J.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Guan, K. Preparation of iron-based biochar by KOH activation and its adsorption properties for tetracycline and ciprofloxacin. Journal of Water Resources and Water Engineering 2024, 35, 20–30+39. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Luo, J.; Fang, R.; Li, S.; Meng, Y. Influential factors of the norfloxacin adsorbed on the corn stalk biochars. Journal of Safety and Environment 2018, 18, 2401–2407. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).