1. Introduction

The lung maintains optimal gas exchange conditions through its extensive alveolar surface area [

1,

2]. Structural integrity of alveolar units depend on the pulmonary extracellular matrix (ECM), composed of elastic fibers and collagen, providing the tissue with rigidity and elasticity essential for efficient respiration [

3]. Elastic recoil of alveolar septa is a fundamental property for normal lung function maintained through precise cell signaling and elastase expression [

4,

5]. Alveolar fibrin deposition is another indicator of respiratory distress or possible acute lung injury [

6]. The lung is also a major site of pathogen exposure; thus, the mucosal immune system must mediate protective inflammatory responses while limiting damage to the delicate alveolar architecture.

The lungs undergo significant structural and functional deterioration with advancing age, in response to the chronic, low-grade inflammatory state termed “inflammaging” [

1,

2,

7,

8,

9]. Inflammaging leads to pathologic remodeling of the ECM, resulting in reduced elasticity and decreased lung function [

6,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Key alterations include increased airspace volume, enhanced proteolysis, reduced alveolar branching complexity, and decreased capillary density [

14,

15,

16,

17]. This pathological airspace enlargement, termed “senile pulmonary emphysema,” is associated with measurable declines in pulmonary function, resulting in decreased activity tolerance and reduced quality of life [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Inflammaging also negatively impacts the mucosal immune response [

18,

23,

24]. As a result, respiratory infections disproportionately increase morbidity and mortality in elderly populations [

25,

26,

27].

The key feature of inflammaging is chronic inflammatory cytokine production. Cytokine-mediated inflammation is regulated by acetylcholine (ACh) in a brain-immune circuit termed the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAP) [

28,

29,

30]. Production of and responsiveness to ACh (cholinergic tone) decreases with aging, directly corresponding to the increased inflammatory cytokine production of inflammaging. Increasing cholinergic tone in the elderly results in decreased systemic inflammation, improved clinical outcomes following respiratory viral infection, and reduces all-cause mortality [

31,

32,

33,

34]. This suggests the effects of inflammaging could be mitigated by increased production of and/or response to ACh [

31,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44].

These observations led us to hypothesize that enhancing cholinergic tone might reverse the deleterious effects of aging/inflammaging on lung structure and function. To test this hypothesis, aged mice were treated with the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) antagonist donepezil to increase ACh bioavailability. Treated mice displayed higher voluntary running, increased blood oxygen saturation, reduced alveolar size, decreased overt inflammation, and increased elastic fiber content relative to age-matched controls. Treated mice also had larger quantities of induced bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT). These findings indicate that enhancing cholinergic tone may present a promising therapeutic avenue to improve lung structure, function, and immune responsiveness during aging.

2. Materials and Methods

Animal Studies: Male and female C57BL/6 mice were bred in-house and used in all studies. Animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at San Diego State University before initiation of experiments. Animals were given free access to food and water and were cared for according to guidelines set by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Care. Aged C57BL/6 male and female mice (18-24 mo.) were administered 2.5 mg/kg/day in the drinking water (based on intake volume of 5 mL/mouse/day) for 6 months. Additional lungs from young male and female C57BL/6 mice (4 mo.) were obtained from the NIA repository.

Voluntary Wheel Running (VWR): Mice were individually housed in a cage containing a disk-style running wheel (Innovive Products) with a magnet attached to the back of the disk, detectable via a magnetic inductive proximity switch counter. Mice had normal access to food and water during the trial, with each trial lasting 18 hours. Animals rested overnight between trials. Each animal had at least four separate running trials prior to donepezil treatment to determine baseline activity. Post-treatment VWR was compared to pre-treatment VWR for each animal.

Specific Blood Oxygen Measurement: A novel prototype pulse oximeter was used to measure oxygen saturation (SpO2). The wired reflectance pulse oximeter was fitted inside a half inch “Mini-Hair Claw Clip” (Hotop via Amazon), which was placed around the rib cage. Mice were acclimatized to the device by wearing the clip several times prior to analysis. The day before observation, animals had their chest, stomach, and abdomen shaved to ensure proper contact between the sensor and the skin. For measurement, each animal was lightly sedated with isoflurane to allow optimal sensor placement for pulse oximetry measurement. Testing started when animals had regained consciousness and were ambulatory. Each animal was tested twice; each test ran for 100 seconds. Data were transferred to a MATLAB program for analysis. SpO2 values lower than 70 were considered erroneous and removed.

Histology: Lungs were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours, then dehydrated in 100% ethanol [

45]. The samples were embedded in paraffin according to standard protocols for microtomy, and lungs were serially sectioned at 5 µm [

46].

Sections were processed for visualization and quality control via Hematoxylin and Eosin stain [

47]. A Modified Russell Movat Pentachrome stain was used to quantify elastic fibers (black) and fibrin (scarlet) [

48]. Collagen and iBALT were quantified via differential staining with Sirius Red and Fast Green as described [

49]. Slides were imaged using a BZ-X810 Fluorescence Microscope (Keyence Corp., Osaka, Japan). Images were captured with the 10x lens (100x total power), and exposure at 1/800. Image tiles were collated and combined into a large file of the whole tissue section.

Image Analysis: After capture, the images were given a 500-micron scale bar for comparison. Mean alveolar area (MAA) was quantified using the Keyence Hybrid Cell Count software program. See Appendix A for a more detailed methodology. MAA was derived from section-based morphometry without standardized air inflation, so values may be influenced by shrinkage and orientation (Figure A1). Each specimen had their percent of tissue area (%) analyzed for elastic fibers, fibrin, collagen, and iBALT, using the “Single Extraction” function of the cell counter. Thresholds for segmentation and color selection were applied uniformly across cohorts; extracted pixel area is reported as percent of tissue area (%). Section level sampling was balanced across cohorts and section fields were treated as independent observations. Identification of iBALT was based on morphology and location; immunophenotypic confirmation was not performed.

Statistical Analysis: All quantitative values are expressed as the mean ± standard error. Cohorts were compared via one-way ANOVA and one-tail t-tests. All one-way ANOVAs, one-tail t-tests, and additional descriptive statistics were performed with GraphPad Prism version 9.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Donepezil Treatment Preserves Physical Activity and Oxygenation in Aged Mice

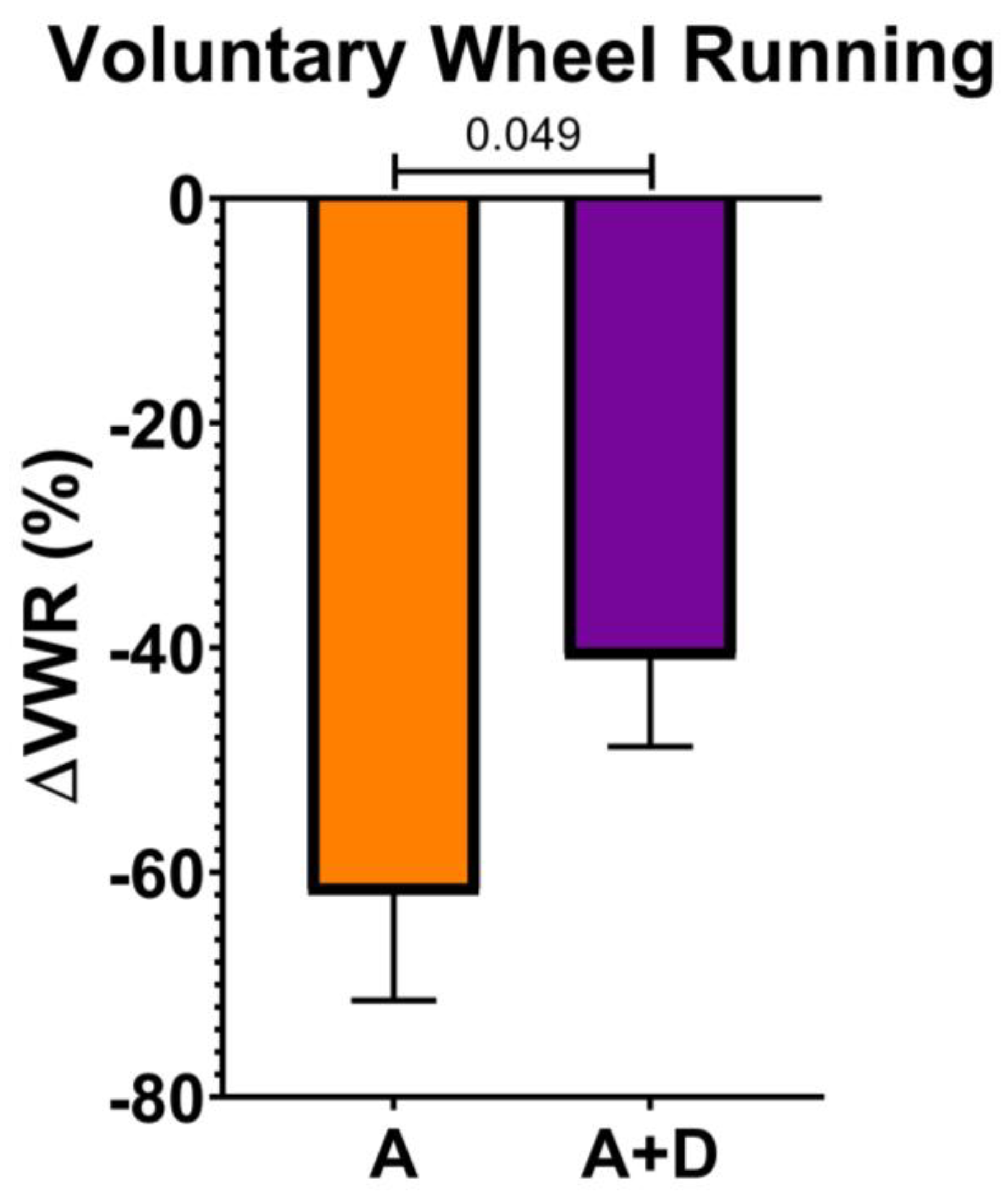

To assess the functional impact of donepezil treatment on healthspan, we first measured spontaneous activity using a VWR assay, a sensitive indicator of overall health in mice. Baseline activity was established at 12 months of age, after which donepezil treatment began at 18 months and continued for 6 months, with a final VWR assessment at 24 months. As expected, both aged groups showed substantial declines in voluntary activity by 24 months of age (

Figure 1). However, the decline was significantly attenuated in donepezil-treated mice (-41 ± 22%) compared to untreated aged controls (-62 ± 23%, p < 0.05). This preservation of approximately one-third of the age-related activity decline suggests that enhanced cholinergic signaling maintains physical capacity during aging.

3.2. Donepezil Treatment Improves Blood Oxygen Saturation

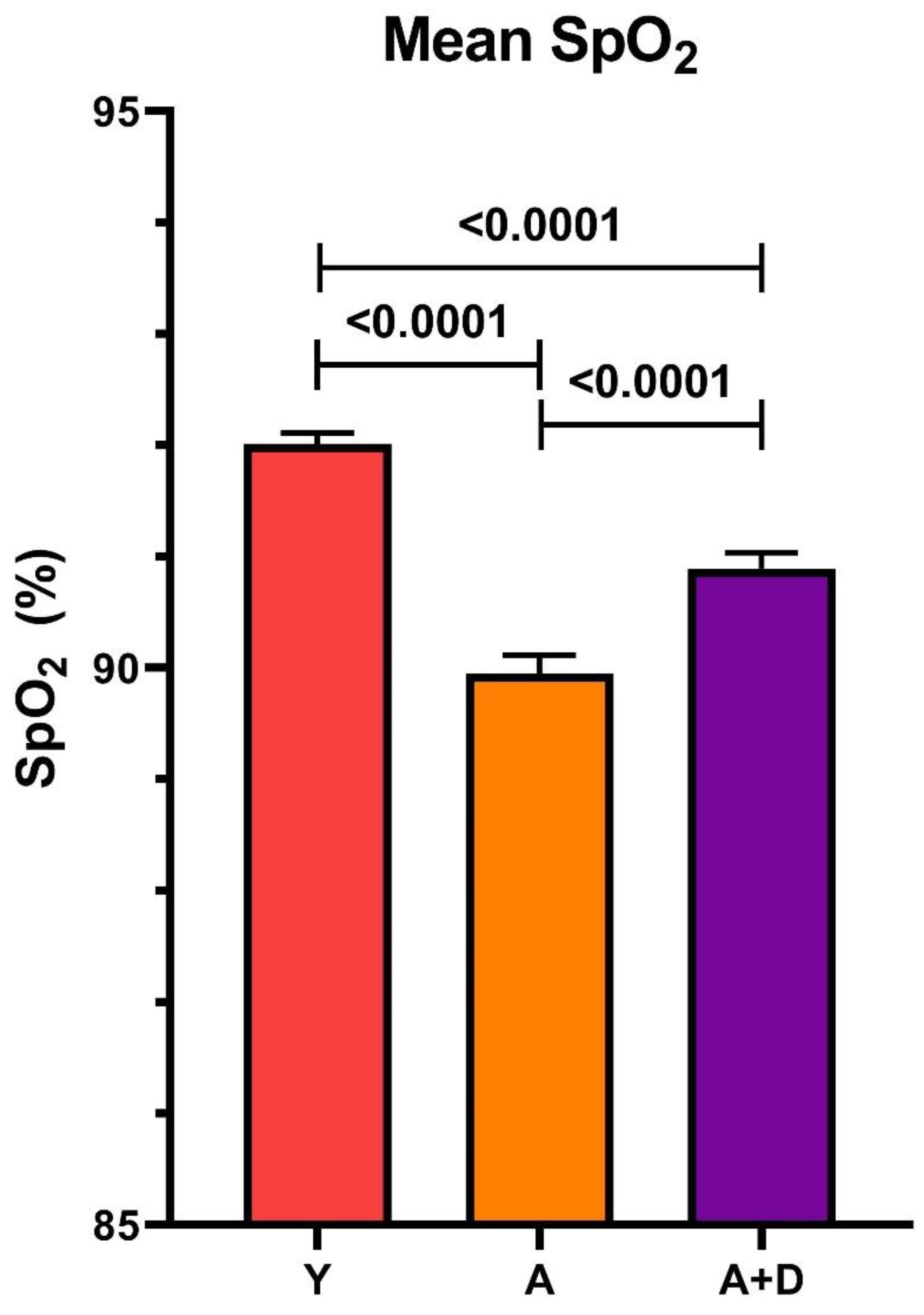

We next measured peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO₂) at 24 months using reflectance pulse oximetry, a non-invasive assessment of pulmonary gas exchange efficiency and cardiovascular function. One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences between groups (F₂,₁₈₅₁ = 53.59, p < 0.0001;

Figure 2). Young controls exhibited the highest SpO₂ (92 ± 2%), with all pairwise comparisons reaching statistical significance (p < 0.05). Critically, donepezil-treated aged mice (91 ± 4%) maintained oxygenation levels intermediate between young controls and aged untreated animals (90 ± 4%). While the absolute difference of 1% may appear modest, even small improvements in SpO₂ can reflect meaningful enhancement of pulmonary function and tissue oxygenation, particularly in the context of age-related physiological decline. Together with the preserved activity levels, these findings suggest that donepezil treatment maintains integrated cardiopulmonary function during aging.

3.3. Histological Assessment of Age-Related Pulmonary Changes

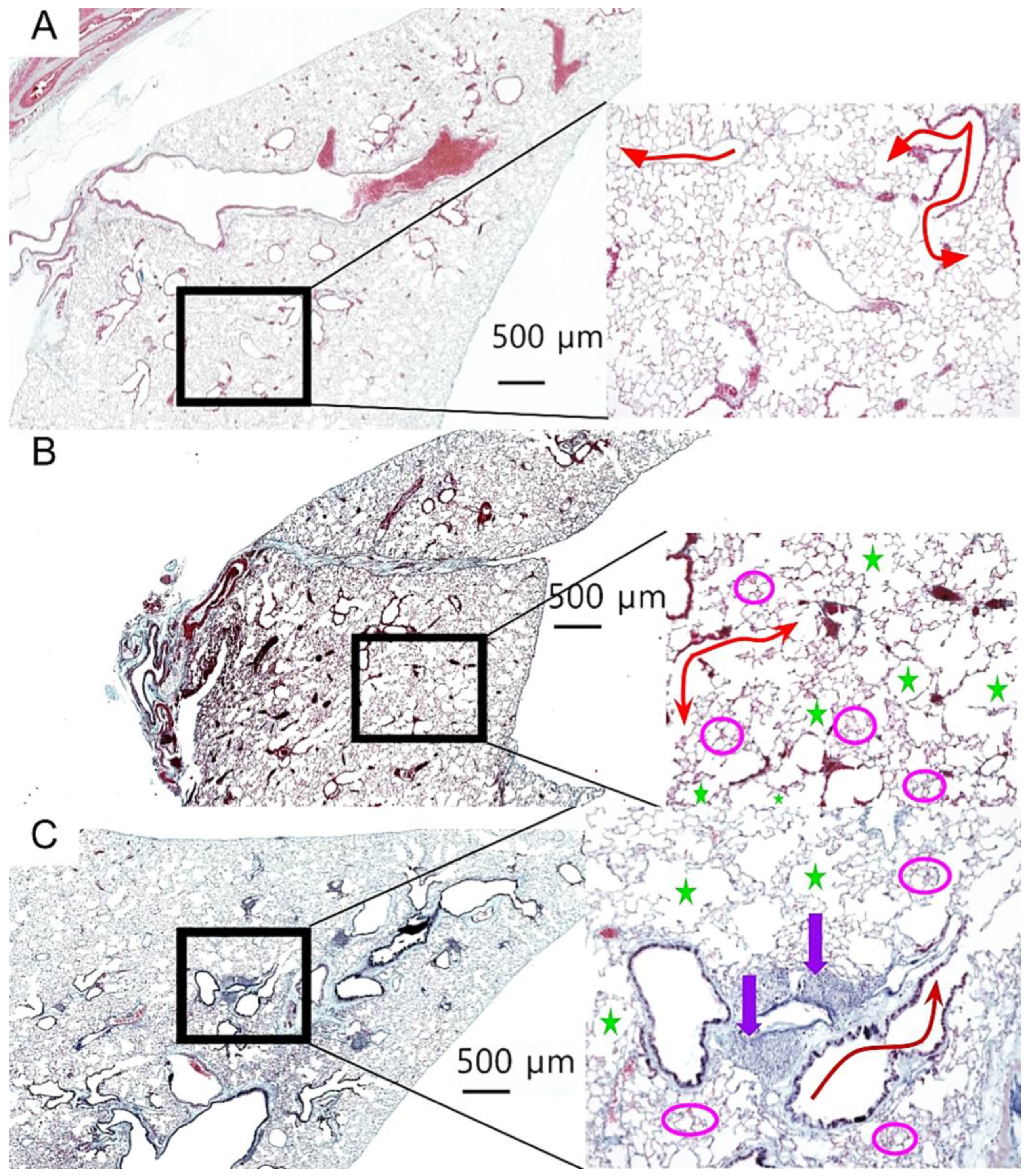

To assess the effects of aging and donepezil treatment on lung architecture, we performed comprehensive histological analysis of lung tissue sections. Representative images from each cohort are shown in

Figure 3, with magnified insets highlighting key architectural features. Young control lungs displayed normal alveolar architecture with uniform airspace size and intact extracellular matrix, with no histological evidence of age-related pathology (

Figure 3A). In contrast, both aged cohorts exhibited classical features of pulmonary aging, including alveolar enlargement, focal emphysematous changes, and fibrin deposition (

Figure 3B, 3C). Notably, donepezil-treated aged mice displayed prominent iBALT follicles, characterized by dense lymphocytic aggregates along the bronchi (

Figure 3C).

To quantify these observed changes, we measured mean alveolar area to assess airspace enlargement, fibrin deposition as a marker of chronic tissue injury, elastic fiber content to evaluate extracellular matrix integrity, and collagen distribution to distinguish pathological fibrosis from iBALT-associated stromal changes.

3.3.1. Donepezil Treatment Partially Preserves Alveolar Architecture in Aged Lungs

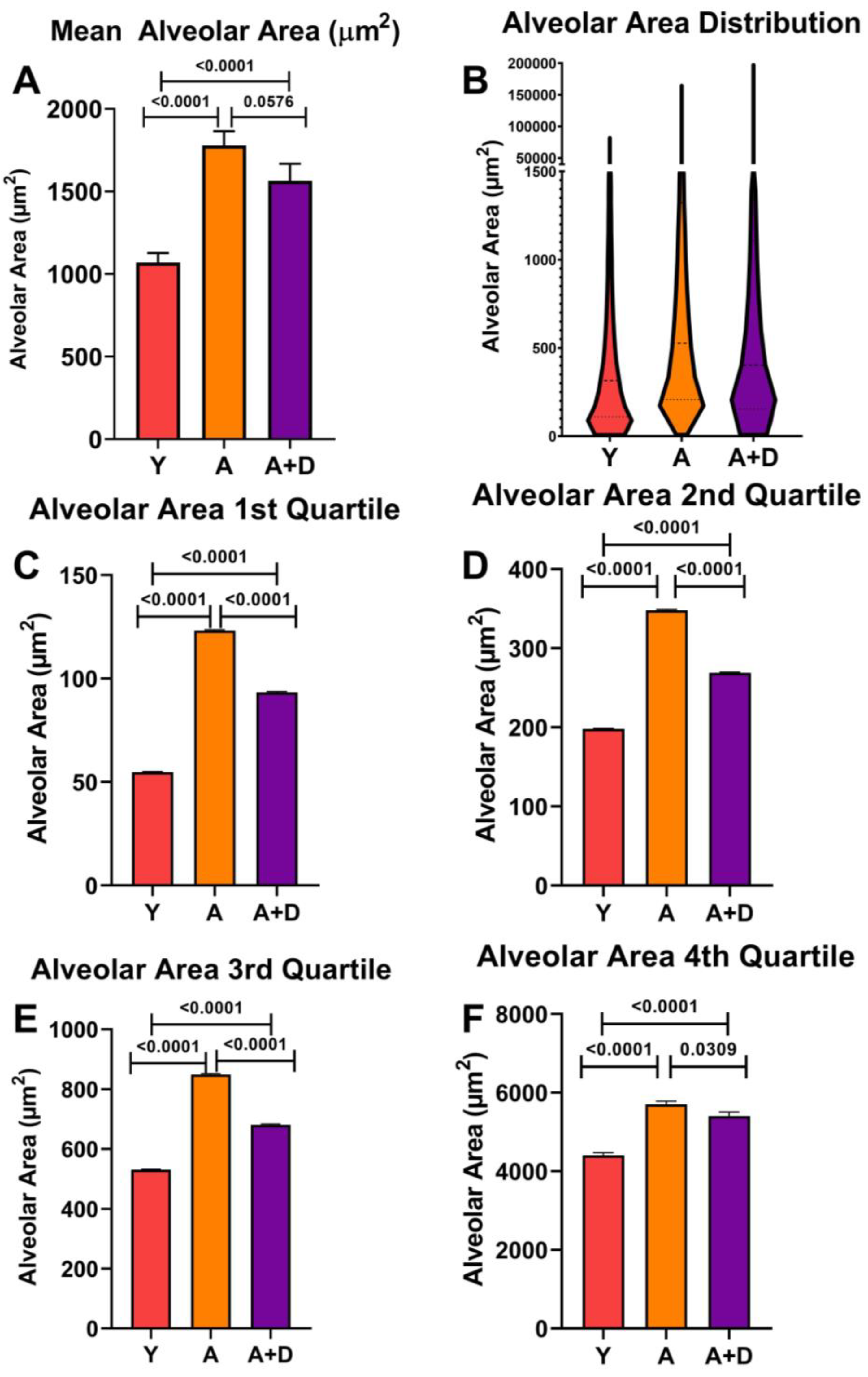

To assess whether donepezil affected age-related alveolar enlargement, we measured approximately 5,000 alveolar spaces per lung and calculated mean alveolar area (MAA). One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences between groups (F₂,₅₂ = 21.0, p < 0.0001;

Figure 4A). As expected, both aged untreated (1779 ± 390 µm²) and aged donepezil-treated mice (1564 ± 399 µm²) showed significantly increased MAA compared to young controls (1070 ± 252 µm²), consistent with age-related alveolar airspace enlargement. Notably, donepezil-treated aged mice showed a trend toward smaller MAA compared to aged untreated animals, approaching statistical significance (p = 0.058).

Visual analysis of the aged lungs (

Figure 3 B,C) showed a wide range of alveolar sizes. The distribution of individual alveolar sizes was analyzed using a violin plot of representative lungs, shown in

Figure 4B (Y: n= 4, A: n= 6, A+D: n= 6). Aged untreated mice displayed a pronounced rightward shift in the distribution, indicating widespread alveolar enlargement. In contrast, donepezil-treated aged mice maintained a substantial population of smaller alveoli alongside the age-related increase in larger alveoli, suggesting preservation or restoration of alveolar architecture.

To quantify the protective effect of donepezil on alveolar size, we performed quartile analysis of alveolar size distributions across four to six representative lungs per group (

Figure 4C-F). This analysis revealed that although young mice maintained the smallest alveoli across all quartiles (p < 0.0001), donepezil treatment consistently attenuated age-related alveolar enlargement across the entire size spectrum. In the first quartile containing the smallest alveoli, (

Figure 4C) donepezil-treated mice maintained significantly smaller alveoli than untreated aged animals (p < 0.001), demonstrating alveolar preservation. In the middle quartiles (

Figure 4D-E), donepezil-treated aged mice showed highly significant reductions in alveolar size compared to aged controls (p < 0.0001). Most strikingly, in the fourth quartile containing the largest and presumably most damaged alveoli, donepezil treatment significantly reduced maximum alveolar size compared to aged controls (p < 0.05;

Figure 4F), indicating that cholinergic enhancement limits the most severe emphysematous changes. The consistent size reduction across the entire distribution demonstrates that enhanced cholinergic signaling attenuates alveolar destruction or induces pulmonary remodeling in the aged lung.

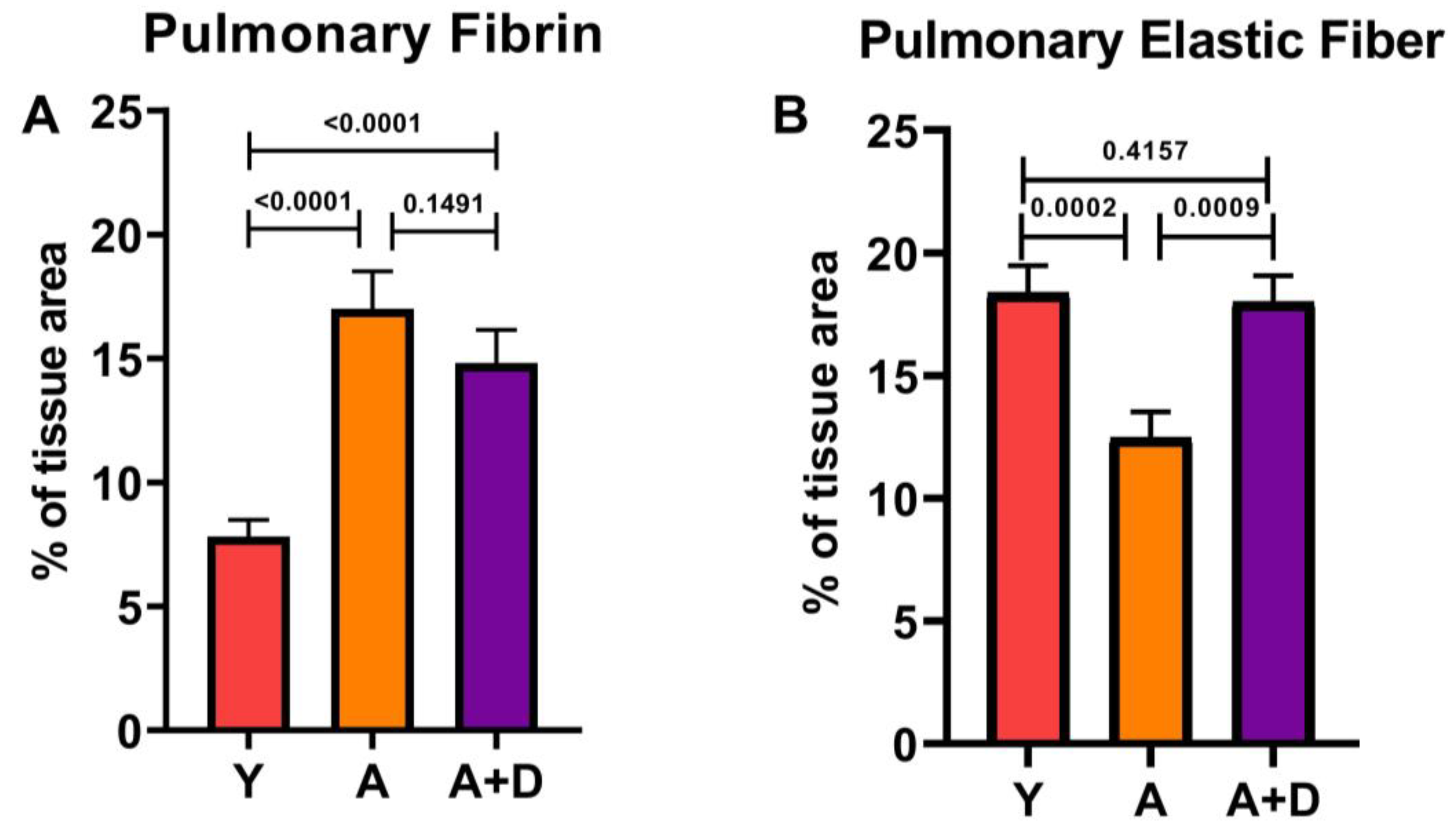

3.3.2. Donepezil Treatment Preserves Elastic Fiber Content in Aged Lungs

In order to examine composition of the extracellular matrix, we quantified fibrin and elastin on Modified Russell Movat Pentachrome-stained sections (

Figure 5). One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences in fibrin deposition between groups (F₂,₄₃ = 22.5, p < 0.0001; Figure 5A). As expected, both aged untreated (17.0 ± 5.4%) and aged donepezil-treated mice (14.8 ± 4.4%) showed significantly elevated fibrin compared to young controls (7.8 ± 3.1%), with no difference between the two aged cohorts. This age-related fibrin accumulation likely reflects chronic low-grade tissue injury and repair processes. In contrast, elastic fiber content showed a remarkable pattern of distribution (F₂,₅₄ = 9.3, p < 0.001; Figure 5B). Aged untreated mice exhibited substantial loss of elastic fibers (12.5 ± 4.8%) compared to young controls (18.4 ± 5.4%), consistent with age-related elastin degradation that contributes to loss of lung compliance. Strikingly, donepezil-treated aged mice maintained elastic fiber content (18.0 ± 3.7%) that was indistinguishable from young animals and significantly higher than aged untreated controls. This complete preservation of elastic fiber architecture suggests that enhanced cholinergic signaling may protect against or reverse age-related elastin degradation, potentially maintaining the structural integrity and mechanical properties of the aging lung.

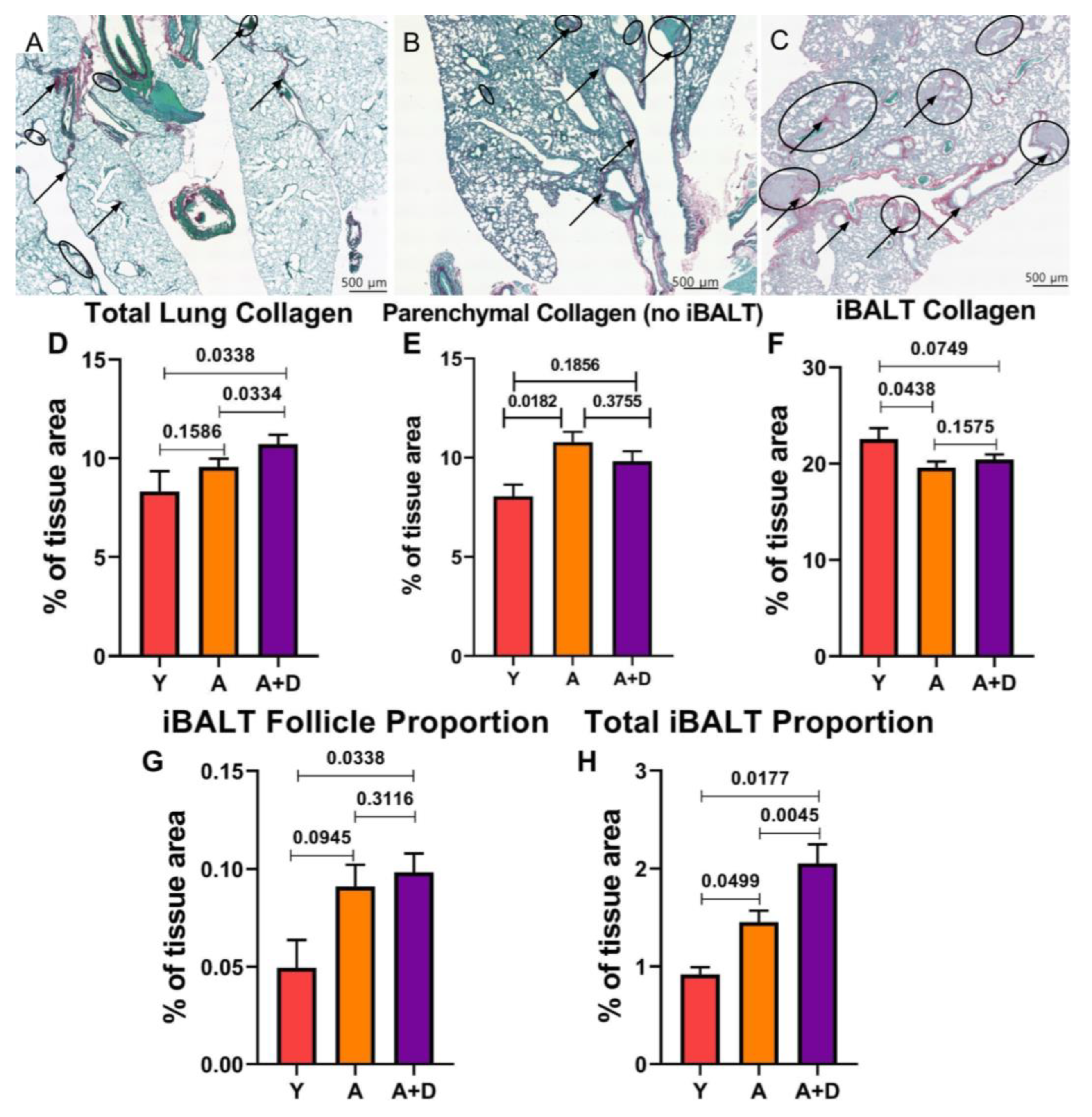

3.4. Donepezil Treatment Increases Total iBALT Without Inducing Pulmonary Fibrosis

Acetylcholine signaling has been implicated in TGF-b associated tissue remodeling pathways that could promote fibrosis [

50,

51]. To assess whether chronic donepezil treatment adversely affects lung architecture, we quantified collagen deposition using Picrosirius red and fast green (PSR) staining, which provides superior sensitivity for collagen detection compared to pentachrome staining. Representative images shown in

Figure 6 show minimal collagen deposition (black arrows) and sparse iBALT in young lungs (

Figure 6A), age-related alveolar enlargement with larger iBALT follicles (circled) in aged untreated mice (

Figure 6B), and prominent collagen-rich iBALT structures in aged donepezil-treated lungs (

Figure 6C).

Collagen tissue percentage was found to change with donepezil treatment (F

2,93 = 2.7777, p= 0.0674) approaching statistical significance. Donepezil-treated aged mice had increased total collagen tissue area percentage (10.72 ± 0.47%) compared to both young (8.17 ± 0.98%) and aged untreated animals (9.57 ± 0.41%; F₂,₉₃ = 2.78, p= 0.067;

Figure 6D). Visually, there was an obvious increase in iBALT structures in the aged animals. This raised the question of whether donepezil was inducing pathological fibrosis or if the increased collagen reflected changes in iBALT content. To differentiate between these possibilities, we separately quantified collagen in lung parenchyma (excluding iBALT) versus within iBALT structures themselves.

Analysis of parenchymal collagen (

Figure 6E) indicated a significant difference was detected between the groups (F

2, 64 = 4.020, p= 0.0227). Aged untreated mice had elevated collagen (10.77 ± 0.53%) compared to young controls (8.05 ± 0.59%), consistent with age-related tissue remodeling. The donepezil-treated aged mice showed intermediate parenchymal collagen (9.82 ± 0.50%) that did not differ significantly from either young or aged untreated groups. This indicate that donepezil treatment did not induce parenchymal fibrosis. If anything, the trend hinted that enhanced cholinergic signaling may partially protect against age-related collagen accumulation in the lung. There were also differences in collagen within iBALT structures (F

2,85 = 1.876, p=0.1595). Young mice showed higher iBALT collagen density (23.03 ± 0.71%) compared to both aged untreated (19.6 ± 0.63%) and aged donepezil-treated animals (20.4 ± 0.52%;

Figure 6F).

The lack of increased collagen density within individual iBALT structures in donepezil-treated mice suggested that the elevated whole-lung collagen stemmed from an overall increase in collagen-rich iBALT tissue. To test this, we measured both the average iBALT size and total tissue area occupied by iBALT structures. The average size of individual iBALT structures increased with age but was not affected by donepezil treatment (young: 0.0494 ± 0.0142%; aged untreated: 0.098 ± 0.0112%; aged + donepezil: 0.0983 ± 0.0096%; F₂,₉₀ = 1.38, p= 0.26;

Figure 6G). However, the total iBALT area as a percentage of lung tissue revealed significant differences (F₂,₉₀ = 5.65, p= 0.005;

Figure 6H). Young mice had minimal iBALT (0.919 ± 0.072%), whereas aged untreated mice showed age-associated increases (1.45 ± 0.115%). The donepezil-treated aged mice exhibited significantly greater total iBALT than either group (2.05 ± 0.196%).

Together, these findings demonstrate that enhanced cholinergic signaling via donepezil increases the total amount of iBALT in aged lungs without inducing parenchymal fibrosis or altering the collagen composition of individual iBALT structures. This represents the first evidence that acetylcholine signaling actively promotes the retention of protective tertiary lymphoid structures in the aging lung.

4. Discussion

Pulmonary aging represents a multifaceted process characterized by diminished oxygen absorption due to alveolar degradation following senile emphysema, loss of elastic fibrils, and pathological remodeling of respiratory tissue composition. Inflammaging is a key factor in this cumulative tissue damage [

52]. ACh is the primary regulator of immune-mediated inflammation. Production of and responses to ACh decrease with aging, corresponding to rise of inflammaging. This suggests the effects of inflammaging could be mitigated by improving cholinergic tone via increased ACh availability. We previously showed that donepezil treatment improved the lung elastic modulus of aged mice and improved lung elasticity [

53]. The present study confirms and extends those findings, showing that enhancing ACh availability facilitates protective remodeling and counteracts specific pathological processes associated with age-related pulmonary decline. Aged animals receiving donepezil treatment showed significantly decreased MAA, restoration of elastic fiber content to young levels, improved SpO₂ and spontaneous activity. Most remarkably, donepezil treatment increased iBALT content. This is a completely novel finding indicating that local ACh production plays a role in maintaining the critical tissue-resident memory niche. Together, these functional and structural improvements underscore the cholinergic system as a clinically relevant therapeutic target for restoring pulmonary function and augmenting respiratory immune protection in the aged. These findings add to the growing body of literature calling for therapeutic intervention in the cholinergic pathway to treat disorders of aging and respiratory health [

28,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59].

The non-invasive measures of voluntary activity and blood oxygen gave the first indication that donepezil therapy improved overall health and lung function. The VWR assay has been used as a non-invasive measure of health for well over 100 years [

60,

61]. Voluntary activity is a similarly robust measure of overall health in humans, one that is recapitulated in the aged C57Bl/6 mice used in these studies [

62,

63].

Human studies have shown that AChE inhibitor therapy improves mobility and reduces inflammation-associated pain, though these studies involved Alzheimer’s patients rather than healthy aging populations [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72]. The improved SpO₂ associated with donepezil treatment has important implications for human healthspan, as low oxygen saturation independently predicts increased all-cause mortality and mortality from pulmonary disease in aging populations [

73,

74].

The significant decreased MAA present in donepezil-treated animals indicated decreased senile emphysema, a hallmark of pulmonary aging that reflects chronic inflammatory damage to alveolar architecture [

75]. The results suggest that smaller alveoli are being protected or regenerated (or both) in response to donepezil treatment, a process that would support more efficient respiration compared to aged controls. We previously showed that altering cholinergic tone impacts pulmonary repair after influenza infection [

76]. The current findings further support the idea that enhanced cholinergic signaling successfully interrupted inflammatory feedback loops that otherwise lead to progressive tissue damage, as well as enhancing repair of the aged pulmonary environment.

The increase in elastic fiber content in aged donepezil treated lungs represents particularly compelling evidence for reversal of age-related pathological processes. Elastic fiber degradation is a causative factor in both senile emphysema and reduced lung compliance [

77,

78,

79]. The ability of enhanced cholinergic signaling to increase elastic fiber content suggests activation of regenerative pathways rather than simple protection from further damage. This is consistent with our previous research indicated that tensile properties improved and elastic modulus was reduced in donepezil-treated lungs indicating a role for ACh in restoring biomechanical properties essential for efficient respiratory function [

53]. In contrast, fibrin deposition remained elevated compared to young controls, suggesting that while ACh promotes matrix regeneration, resolution of chronic injury markers may require longer treatment duration or additional interventions.

The improved SpO₂ in donepezil-treated mice directly addresses one of the most clinically relevant consequences of pulmonary aging and is consistent with our structural findings [

80]. There is extensive literature support showing that inhibiting cholinergic signaling impacts lung remodeling, whereas increasing ACh signaling decreases acute inflammation, normalizes tissue repair and improves lung function [

32,

81,

82,

83,

84]. This supports our hypothesis that declining ACh availability represents a key mechanism of inflammaging, and that increasing cholinergic signaling can prevent deleterious consequences of aging, including respiratory deficiency. The mechanisms underlying these improvements align with the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7-nAChR) pathway [

85,

86,

87]. Enhanced ACh availability promotes alternative macrophage activation via α7-nAChR signaling, leading to decreased NF-κB activation and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production [

88]. This shift from pro-inflammatory toward anti-inflammatory, reparative macrophage phenotypes facilitates efferocytosis and tissue regeneration, directly addressing the dysfunctional repair mechanisms that characterize the aged lung.

Engagement of the a7-nAChR is also associated with bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis, leading us to analyze collagen deposition [

51]. We did not find any evidence that donepezil treatment led to fibrotic sequela; in fact, the untreated aged animals exhibited the most lung collagen. Rather than inducing fibrosis, increasing ACh availability may actively reduce ongoing fibrotic activity or reverse fibrotic damage through tissue repair mechanisms.

Donepezil Treatment Increases iBALT Formation: Implications for Respiratory Immunity

This study also showed that increased ACh availability dramatically increases iBALT formation. This represents a previously unknown role for the non-neuronal cholinergic system in tissue-specific immune function. Donepezil-treatment increased the number of iBALT regions, suggesting that ACh availability influences the development and maintenance of pulmonary adaptive immune capacity. This finding has profound therapeutic implications. iBALT serves as a site for antigen presentation, lymphocyte activation, memory cell development, and tissue resident memory lymphocyte sequestration [

89,

90]. Immune responses originating from iBALT tissue-resident memory cells induce rapid local protection against infection while producing less inflammation than immune responses originating from local lymph nodes [

91]. This decreased inflammation is likely due to the presence of tissue resident memory cholinergic lymphocytes retained in the iBALT producing local ACh as part of the secondary immune response [

76,

92]. The age-related loss of iBALT structures would therefore impair respiratory immune function through loss of local memory populations diminished anti-inflammatory capacity. Decreased ACh availability results in extended inflammation and abnormal tissue repair after respiratory viral infection, similar to the extended morbidity exhibited by the elderly [

76]. These findings support the possibility of an additional role for non-neuronal cholinergic function in respiratory immune protection. Collectively, these findings are consistent with the greatly increased susceptibility to respiratory infections associated with aging.

There are substantial clinical implications for our finding that donepezil treatment is associated with an increase in iBALT. Respiratory infections remain among the top causes of death in those over age 65. Our finding that cholinergic enhancement strengthens the lung’s capacity for local adaptive immunity is consistent with clinical studies showing donepezil treatment reduces risk of death from respiratory infection [

33,

34]. Our use of donepezil, an FDA-approved medication with an established safety profile in elderly patient populations, significantly enhances the translational relevance of our study. Retrospective analyses have demonstrated that donepezil treatment is associated with reduced overall mortality and pneumonia-related mortality [

33,

59,

93]. Furthermore, enhancing the respiratory immune response through iBALT formation suggests potential applications beyond simple anti-aging interventions, including enhancement of vaccine efficacy and respiratory infection resistance in elderly populations.

The current study shows that ACh acts as an autocrine/paracrine signal in iBALT retention. While this study did not identify the specific source(s) of pulmonary ACh production, our previous study indicated that cholinergic lymphocytes were retained in iBALT after respiratory infection, making them the likely source of immunomodulatory ACh [

76]. However, the lung has multiple other ACh sources, including cholinergic neurons and bronchial epithelium. Critical next steps include development of specific biomarkers for cholinergic lymphocytes to enable their isolation and characterization in human studies, direct measurement of tissue ACh levels and AChE inhibition, and evaluation of receptor dependence using receptor-deficient models. Additionally, future assessment of inflammatory mediators, macrophage polarization states, and iBALT immune function will provide deeper mechanistic insights.

This study has limitations. We did not directly measure receptor pathway engagement, so the observed changes could theoretically reflect systemic or off-target effects, though results were consistent with enhanced cholinergic signaling. Additionally, lack of a mid-treatment timepoint prevents differentiation between prevention of ongoing damage versus induction of tissue repair. Future studies will address these mechanistic questions and include detailed characterization of cholinergic lymphocyte function and local inflammatory parameters. These limitations reflect the practical constraints imposed by COVID-19 pandemic restrictions on laboratory access and resource allocation during the study period.

One key strength of this study is the aged murine model system. Employing an aged mouse model is a significant advantage, as murine pulmonary, cholinergic, and immunological aging closely parallels human systems. The use of naturally aged mice allowed us to evaluate the therapeutic impact of increased ACh bioavailability in a physiologically relevant model of human pulmonary aging. This translational relevance, combined with donepezil’s established clinical safety, positions our findings for rapid advancement to human studies.

5. Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that the non-neuronal cholinergic system represents a critical therapeutic target to reverse age-related pulmonary damage and enhance tissue-specific adaptive immune function. The comprehensive improvements observed with donepezil treatment included partial reversal of alveolar enlargement, restoration of elastic fiber content, enhanced blood oxygenation, and augmented adaptive immunity through iBALT retention. This provides compelling evidence that age-related pulmonary decline results from cholinergic dysfunction. In addition, our discovery that cholinergic enhancement dramatically increases iBALT formation reveals a previously unrecognized mechanism by which ACh availability influences adaptive immune capacity in the aged lung. These findings support a therapeutic paradigm whereby improving cholinergic tone could reverse multiple aspects of age-related respiratory decline while augmenting respiratory immune function.

The clinical translatability of these findings is straightforward, given the known safety profile and existing clinical use of acetylcholinesterase antagonists in elderly populations. Retrospective clinical analysis confirm that donepezil reduces mortality from respiratory infection, further supporting the therapeutic potential of our study. Future clinical studies examining respiratory function and infection outcomes in the context of cholinergic enhancement will determine whether targeting the non-neuronal cholinergic system can translate from a promising experimental intervention to a clinically meaningful approach for extending respiratory healthspan and reducing age-related infection susceptibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, KK and JP; methodology, KK, IN, KM, MS, MW, JP; software, KK, IN, KM; validation, KK, IN, KM, JP; formal analysis; KK, IN, KM, MW, DD, JP; investigation, KK, IN, KM, MW, DD; resources, IN, KM, MS, JP; data curation, KK, KM, JP; writing—original draft preparation, KK, JP; writing—review and editing, KK, IN, KM, MS, JP; visualization, KK; supervision, IN, MS, MW, JP; project administration, JP; funding acquisition, IN, KM, MS, JP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by an SDSU Big Idea Grant (KM, JP), and an SDSU Innovation grant (JP).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of San Diego State University (APF protocol code 18-06-008P approved 072418 and 21-06-004P approved 07192021).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECM |

Extracellular matrix |

| ACh |

Acetylcholine |

| CAP |

Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory pathway |

| AChE |

Acetylcholinesterase |

| iBALT |

Induced Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue |

| IACUC |

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| VWR |

Voluntary wheel running |

| LHS |

Lung and Heart sound (monitor) |

| SpO2

|

Peripheral oxygen saturation |

| MAA |

Mean alveolar area |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| BSAF |

Biebrich scarlet-acid fuchsin |

| PSR |

Picrosirius red |

| α7-nAChR |

α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor |

References

- Patwa, A.; Shah, A. Anatomy and physiology of respiratory system relevant to anaesthesia. Indian J Anaesth 2015, 59, 533-541. [CrossRef]

- Thurlbeck, W.M. Internal surface area of normal and emphysematous lungs. Aspen Emphysema Conf 1967, 10, 379-393.

- Suki, B.; Ito, S.; Stamenovic, D.; Lutchen, K.R.; Ingenito, E.P. Biomechanics of the lung parenchyma: critical roles of collagen and mechanical forces. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2005, 98, 1892-1899. [CrossRef]

- Faniyi, A.A.; Hughes, M.J.; Scott, A.; Belchamber, K.B.R.; Sapey, E. Inflammation, ageing and diseases of the lung: Potential therapeutic strategies from shared biological pathways. Br J Pharmacol 2022, 179, 1790-1807. [CrossRef]

- Bou Jawde, S.; Takahashi, A.; Bates, J.H.T.; Suki, B. An Analytical Model for Estimating Alveolar Wall Elastic Moduli From Lung Tissue Uniaxial Stress-Strain Curves. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 121. [CrossRef]

- Idell, S. Coagulation, fibrinolysis, and fibrin deposition in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2003, 31, S213-220. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Vitale, G.; Capri, M.; Salvioli, S. Inflammaging and ‘Garb-aging’. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2017, 28, 199-212. [CrossRef]

- Dugan, B.; Conway, J.; Duggal, N.A. Inflammaging as a target for healthy ageing. Age Ageing 2023, 52. [CrossRef]

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Pawelec, G.; Khalil, A.; Cohen, A.A.; Hirokawa, K.; Witkowski, J.M.; Franceschi, C. Immunology of Aging: the Birth of Inflammaging. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2023, 64, 109-122. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Ono, K.; Fujiwara, T.; Sawada, H.; Mori, I. [Pulmonary surfactant]. Nihon Ishikai Zasshi 1971, 66, 100-116.

- Cho, S.J.; Stout-Delgado, H.W. Aging and Lung Disease. Annu Rev Physiol 2020, 82, 433-459. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Prather, E.R.; Stetskiv, M.; Garrison, D.E.; Meade, J.R.; Peace, T.I.; Zhou, T. Inflammaging and oxidative stress in human diseases: From molecular mechanisms to novel treatments. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 4472-4472. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.K.; Weiss, D.J.; Westergren-Thorsson, G.; Wigen, J.; Dean, C.H.; Mumby, S.; Bush, A.; Adcock, I.M. Extracellular Matrix as a Driver of Chronic Lung Diseases. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2024, 70, 239-246. [CrossRef]

- Gillooly, M.; Lamb, D. Airspace size in lungs of lifelong non-smokers: effect of age and sex. Thorax 1993, 48, 39-43. [CrossRef]

- Tuder, R.M.; Yoshida, T.; Arap, W.; Pasqualini, R.; Petrache, I. State of the art. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of alveolar destruction in emphysema: an evolutionary perspective. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006, 3, 503-510. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Goodwin, J. Effect of aging on respiratory system physiology and immunology. Clin Interv Aging 2006, 1, 253-260. [CrossRef]

- Karrasch, S.; Holz, O.; Jorres, R.A. Aging and induced senescence as factors in the pathogenesis of lung emphysema. Respir Med 2008, 102, 1215-1230. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.J.; Speth, J.M.; Penke, L.R.; Wettlaufer, S.H.; Swanson, J.A.; Peters-Golden, M. Mechanisms and modulation of microvesicle uptake in a model of alveolar cell communication. J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 20897-20910. [CrossRef]

- Janssens, J.P.; Pache, J.C.; Nicod, L.P. Physiological changes in respiratory function associated with ageing. Eur Respir J 1999, 13, 197-205. [CrossRef]

- Meban, C. Cytochemistry of the gas-exchange area in vertebrate lungs. Prog Histochem Cytochem 1987, 17, 1-54. [CrossRef]

- Skloot, G.S. The Effects of Aging on Lung Structure and Function. Clin Geriatr Med 2017, 33, 447-457. [CrossRef]

- Idell, S.; Zwieb, C.; Boggaram, J.; Holiday, D.; Johnson, A.R.; Raghu, G. Mechanisms of fibrin formation and lysis by human lung fibroblasts: influence of TGF-beta and TNF-alpha. Am J Physiol 1992, 263, L487-494. [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Bientinesi, E.; Monti, D. Immunosenescence and inflammaging in the aging process: age-related diseases or longevity? Ageing Res Rev 2021, 71, 101422. [CrossRef]

- Soma, T.; Nagata, M. Immunosenescence, Inflammaging, and Lung Senescence in Asthma in the Elderly. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Boraschi, D.; Italiani, P. Immunosenescence and vaccine failure in the elderly: strategies for improving response. Immunol Lett 2014, 162, 346-353. [CrossRef]

- Smetana, J.; Chlibek, R.; Shaw, J.; Splino, M.; Prymula, R. Influenza vaccination in the elderly. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018, 14, 540-549. [CrossRef]

- Bridges, J.P.; Weaver, T.E. Use of transgenic mice to study lung morphogenesis and function. ILAR J 2006, 47, 22-31. [CrossRef]

- Gwilt, C.R.; Donnelly, L.E.; Rogers, D.F. The non-neuronal cholinergic system in the airways: an unappreciated regulatory role in pulmonary inflammation? Pharmacol Ther 2007, 115, 208-222. [CrossRef]

- Kolahian, S.; Gosens, R. Cholinergic regulation of airway inflammation and remodelling. J Allergy (Cairo) 2012, 2012, 681258. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, U. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway alleviates acute lung injury. Mol Med 2020, 26, 64. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.J.; Breathnach, C.; Tracey, K.J.; Donnelly, S.C. Manipulation of the inflammatory reflex as a therapeutic strategy. Cell Rep Med 2022, 3, 100696. [CrossRef]

- Bej, T.A.; Edmiston, E.; Wilson, B.; Phillips, J.; Jump, R.L. 1088. Evaluating the Effect of Donepezil on Mortality Among Alzheimer’s Disease Patients With and Without COVID-19 Infection. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Abe, Y.; Shimokado, K.; Fushimi, K. Donepezil is associated with decreased in-hospital mortality as a result of pneumonia among older patients with dementia: A retrospective cohort study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2018, 18, 269-275. [CrossRef]

- Edmiston, E.A.; Bej, T.A.; Wilson, B.; Jump, R.L.P.; Phillips, J.A. Donepezil-associated survival benefits among Alzheimer’s disease patients are retained but not enhanced during COVID-19 infections. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2023, 10, 20499361231174289. [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, N.; Oyabu, M.; Sato, T.; Maeda, T.; Minami, H.; Tamai, I. Decreased biosynthesis of lung surfactant constituent phosphatidylcholine due to inhibition of choline transporter by gefitinib in lung alveolar cells. Pharm Res 2008, 25, 417-427. [CrossRef]

- Barkauskas, C.E.; Cronce, M.J.; Rackley, C.R.; Bowie, E.J.; Keene, D.R.; Stripp, B.R.; Randell, S.H.; Noble, P.W.; Hogan, B.L. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J Clin Invest 2013, 123, 3025-3036. [CrossRef]

- Aegerter, H.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Jakubzick, C.V. Biology of lung macrophages in health and disease. Immunity 2022, 55, 1564-1580. [CrossRef]

- Doran, A.C.; Yurdagul, A., Jr.; Tabas, I. Efferocytosis in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 254-267. [CrossRef]

- Losa Garcia, J.E.; Rodriguez, F.M.; Martin de Cabo, M.R.; Garcia Salgado, M.J.; Losada, J.P.; Villaron, L.G.; Lopez, A.J.; Arellano, J.L. Evaluation of inflammatory cytokine secretion by human alveolar macrophages. Mediators Inflamm 1999, 8, 43-51. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, J.F.; Lu, Z.Y.; Massart, C.; Levon, K. Dynamic Immune/Inflammation Precision Medicine: The Good and the Bad Inflammation in Infection and Cancer. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 595722. [CrossRef]

- Reichrath, S.; Reichrath, J.; Moussa, A.T.; Meier, C.; Tschernig, T. Targeting the non-neuronal cholinergic system in macrophages for the management of infectious diseases and cancer: challenge and promise. Cell Death Discov 2016, 2, 16063. [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.M.; Waters, C.M. Epithelial repair mechanisms in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2010, 298, L715-731. [CrossRef]

- Sirianni, F.E.; Milaninezhad, A.; Chu, F.S.; Walker, D.C. Alteration of fibroblast architecture and loss of Basal lamina apertures in human emphysematous lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006, 173, 632-638. [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, W.J.; Frank, D.B.; Zepp, J.A.; Morley, M.P.; Alkhaleel, F.A.; Kong, J.; Zhou, S.; Cantu, E.; Morrisey, E.E. Regeneration of the lung alveolus by an evolutionarily conserved epithelial progenitor. Nature 2018, 555, 251-255. [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, R. Methods of lung fixation. Forensic Pathology Reviews 2006, 4, 437-451.

- An, Y.H.; Moreira, P.L.; Kang, Q.K.; Gruber, H.E. Principles of Embedding and Common Protocols. In Handbook of Histology Methods for Bone and Cartilage, 1 ed.; An. Y. H, Martin, K.L., Eds.An, Y.H., Martin, K.L., Eds.; Humana Press, Totowa, NJ: 2003; pp. 185-197.

- Cardiff, R.D.; Miller, C.H.; Munn, R.J. Manual hematoxylin and eosin staining of mouse tissue sections. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2014, 2014, 655-658. [CrossRef]

- Hogg, J.C.; Chu, F.; Utokaparch, S.; Woods, R.; Elliott, W.M.; Buzatu, L.; Cherniack, R.M.; Rogers, R.M.; Sciurba, F.C.; Coxson, H.O.; et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004, 350, 2645-2653. [CrossRef]

- Marlow, S.L.; Blennerhassett, M.G. Deficient innervation characterizes intestinal strictures in a rat model of colitis. Exp Mol Pathol 2006, 80, 54-66. [CrossRef]

- Lachapelle, P.; Li, M.; Douglass, J.; Stewart, A. Safer approaches to therapeutic modulation of TGF-beta signaling for respiratory disease. Pharmacol Ther 2018, 187, 98-113. [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Li, L.; Zhao, C.; Pan, M.; Qian, Z.; Su, X. Deficiency of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor attenuates bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice. Mol Med 2017, 23, 34-39. [CrossRef]

- Meiners, S.; Eickelberg, O.; Konigshoff, M. Hallmarks of the ageing lung. Eur Respir J 2015, 45, 807-827. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Navindaran, K.; Phillips, J.; Kenny, K.; Moon, K.S. Characterization of mechanical properties of soft tissues using sub-microscale tensile testing and 3D-Printed sample holder. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2023, 138, 105581. [CrossRef]

- Benfante, R.; Di Lascio, S.; Cardani, S.; Fornasari, D. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors targeting the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: a new therapeutic perspective in aging-related disorders. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021, 33, 823-834. [CrossRef]

- Cremin, M.; Schreiber, S.; Murray, K.; Tay, E.X.Y.; Reardon, C. The diversity of neuroimmune circuits controlling lung inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2023, 324, L53-L63. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Ichinose, M. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: an innovative treatment strategy for respiratory diseases and their comorbidities. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2018, 40, 18-25. [CrossRef]

- Wessler, I.K.; Kirkpatrick, C.J. The Non-neuronal cholinergic system: an emerging drug target in the airways. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2001, 14, 423-434. [CrossRef]

- Knoeller, G.E.; Mazurek, J.M.; Moorman, J.E. Health-related quality of life among adults with work-related asthma in the United States. Qual Life Res 2013, 22, 771-780. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.; Murali, M. Repurposing donepezil to treat COVID-19: a call for retrospective analysis of existing patient datasets. J Clin Immunol Microbiol 2021, 2, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Meijer, J.H.; Robbers, Y. Wheel running in the wild. Proc Biol Sci 2014, 281. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.C. Variations in Daily Activity Produced by Alcohol and by Changes in Barometric Pressure and Diet, with a Description of Recording Methods. American Journal of Physiology-Legacy Content 1898, 1, 40-56. [CrossRef]

- Goh, J.; Ladiges, W. Voluntary Wheel Running in Mice. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol 2015, 5, 283-290. [CrossRef]

- Bruunsgaard, H.; Pedersen, B.K. Age-related inflammatory cytokines and disease. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2003, 23, 15-39. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Odasso, M.; Speechley, M.; Chertkow, H.; Sarquis-Adamson, Y.; Wells, J.; Borrie, M.; Vanderhaeghe, L.; Zou, G.Y.; Fraser, S.; Bherer, L.; et al. Donepezil for gait and falls in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Neurol 2019, 26, 651-659. [CrossRef]

- Bizpinar, O.; Onder, H. Investigation of the gait parameters after donepezil treatment in patients with alzheimer’ s disease. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 2025, 32, 407-411. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Odasso, M.; Muir-Hunter, S.W.; Oteng-Amoako, A.; Gopaul, K.; Islam, A.; Borrie, M.; Wells, J.; Speechley, M. Donepezil improves gait performance in older adults with mild Alzheimer’s disease: a phase II clinical trial. J Alzheimers Dis 2015, 43, 193-199. [CrossRef]

- Beauchet, O.; Launay, C.P.; Allali, G.; Herrmann, F.R.; Annweiler, C. Gait changes with anti-dementia drugs: a prospective, open-label study combining single and dual task assessments in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Aging 2014, 31, 363-372. [CrossRef]

- Assal, F.; Allali, G.; Kressig, R.W.; Herrmann, F.R.; Beauchet, O. Galantamine improves gait performance in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008, 56, 946-947. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Odasso, M.; Schapira, M.; Soriano, E.R.; Varela, M.; Kaplan, R.; Camera, L.A.; Mayorga, L.M. Gait velocity as a single predictor of adverse events in healthy seniors aged 75 years and older. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005, 60, 1304-1309. [CrossRef]

- Morante, F.; Guell, R.; Mayos, M. [Efficacy of the 6-minute walk test in evaluating ambulatory oxygen therapy]. Arch Bronconeumol 2005, 41, 596-600. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Blanhir, J.E.; Palafox Vidal, C.D.; Rosas Romero Mde, J.; Garcia Castro, M.M.; Londono Villegas, A.; Zamboni, M. Six-minute walk test: a valuable tool for assessing pulmonary impairment. J Bras Pneumol 2011, 37, 110-117. [CrossRef]

- Camarri, B.; Eastwood, P.R.; Cecins, N.M.; Thompson, P.J.; Jenkins, S. Six minute walk distance in healthy subjects aged 55-75 years. Respir Med 2006, 100, 658-665. [CrossRef]

- Vold, M.L.; Aasebo, U.; Wilsgaard, T.; Melbye, H. Low oxygen saturation and mortality in an adult cohort: the Tromso study. BMC Pulm Med 2015, 15, 9. [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, T.; Chen, Q. Nocturnal oxygen saturation is associated with all-cause mortality: a community-based study. J Clin Sleep Med 2024, 20, 229-235. [CrossRef]

- Polverino, F. Best of Milan 2017-repair of the emphysematous lung: mesenchymal stromal cell and matrix. J Thorac Dis 2017, 9, S1544-S1547. [CrossRef]

- Horkowitz, A.P.; Schwartz, A.V.; Alvarez, C.A.; Herrera, E.B.; Thoman, M.L.; Chatfield, D.A.; Osborn, K.G.; Feuer, R.; George, U.Z.; Phillips, J.A. Acetylcholine Regulates Pulmonary Pathology During Viral Infection and Recovery. Immunotargets Ther 2020, 9, 333-350. [CrossRef]

- Labat-Robert, J.; Robert, L. Aging of the extracellular matrix and its pathology. Exp Gerontol 1988, 23, 5-18. [CrossRef]

- Colebatch, H.J.; Finucane, K.E.; Smith, M.M. Pulmonary conductance and elastic recoil relationships in asthma and emphysema. J Appl Physiol 1973, 34, 143-153. [CrossRef]

- Fagiola, M.; Reznik, S.; Riaz, M.; Qyang, Y.; Lee, S.; Avella, J.; Turino, G.; Cantor, J. The relationship between elastin cross linking and alveolar wall rupture in human pulmonary emphysema. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2023, 324, L747-L755. [CrossRef]

- Brandsma, C.A.; de Vries, M.; Costa, R.; Woldhuis, R.R.; Konigshoff, M.; Timens, W. Lung ageing and COPD: is there a role for ageing in abnormal tissue repair? Eur Respir Rev 2017, 26. [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Lee, J.W.; Matthay, Z.A.; Mednick, G.; Uchida, T.; Fang, X.; Gupta, N.; Matthay, M.A. Activation of the alpha7 nAChR reduces acid-induced acute lung injury in mice and rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2007, 37, 186-192. [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Matthay, M.A.; Malik, A.B. Requisite role of the cholinergic alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor pathway in suppressing Gram-negative sepsis-induced acute lung inflammatory injury. J Immunol 2010, 184, 401-410. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, N.M.; Miranda, C.J.; Perini, A.; Camara, N.O.; Costa, S.K.; Alonso-Vale, M.I.; Caperuto, L.C.; Tiberio, I.F.; Prado, M.A.; Martins, M.A.; et al. Pulmonary inflammation is regulated by the levels of the vesicular acetylcholine transporter. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0120441. [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, N.M.; Santana, F.P.; Almeida, R.R.; Guerreiro, M.; Martins, M.A.; Caperuto, L.C.; Camara, N.O.; Wensing, L.A.; Prado, V.F.; Tiberio, I.F.; et al. Acute lung injury is reduced by the alpha7nAChR agonist PNU-282987 through changes in the macrophage profile. FASEB J 2017, 31, 320-332. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Wei, T.; Chen, J.; Pan, T.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Song, J.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. alpha7nAChR activation in AT2 cells promotes alveolar regeneration through WNT7B signaling in acute lung injury. JCI Insight 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.W.; Li, L.; Huang, Y.Y.; Zhao, C.Q.; Xue, S.J.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.Z.; Xu, J.F.; Su, X. Vagal-alpha7nAChR signaling is required for lung anti-inflammatory responses and arginase 1 expression during an influenza infection. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2021, 42, 1642-1652. [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.A.; Bassi, C.; Saunders, M.E.; Nechanitzky, R.; Morgado-Palacin, I.; Zheng, C.; Mak, T.W. Beyond neurotransmission: acetylcholine in immunity and inflammation. J Intern Med 2020, 287, 120-133. [CrossRef]

- Veldhuizen, R.A.W.; McCaig, L.A.; Pape, C.; Gill, S.E. The effects of aging and exercise on lung mechanics, surfactant and alveolar macrophages. Exp Lung Res 2019, 45, 113-122. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.Y.; Randall, T.D.; Silva-Sanchez, A. Inducible Bronchus-Associated Lymphoid Tissue: Taming Inflammation in the Lung. Front Immunol 2016, 7, 258. [CrossRef]

- Marin, N.D.; Dunlap, M.D.; Kaushal, D.; Khader, S.A. Friend or Foe: The Protective and Pathological Roles of Inducible Bronchus-Associated Lymphoid Tissue in Pulmonary Diseases. J Immunol 2019, 202, 2519-2526. [CrossRef]

- Moyron-Quiroz, J.E.; Rangel-Moreno, J.; Kusser, K.; Hartson, L.; Sprague, F.; Goodrich, S.; Woodland, D.L.; Lund, F.E.; Randall, T.D. Role of inducible bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in respiratory immunity. Nat Med 2004, 10, 927-934. [CrossRef]

- Silva-Sanchez A, R.T. Anatomical Uniqueness of the Mucosal Immune System (GALT, NALT, iBALT) for the Induction and Regulation of Mucosal Immunity and Tolerance. Mucosal Vaccines 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, N.P.; Alstrup, A.K.; Mortensen, F.V.; Knudsen, K.; Jakobsen, S.; Madsen, L.B.; Bender, D.; Breining, P.; Petersen, M.S.; Schleimann, M.H.; et al. Cholinergic PET imaging in infections and inflammation using (11)C-donepezil and (18)F-FEOBV. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2017, 44, 449-458. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Donepezil treatment preserves voluntary activity. Percentage change in voluntary wheel running between age 12 months (baseline) and 24 months (post-treatment). Aged untreated mice (A) showed greater activity decline than aged mice treated with donepezil for 6 months (A+D). n = 6-8 per group. Significant differences were determined by one-tailed t-test. Bars represent mean ± SE; significance = p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Donepezil treatment preserves voluntary activity. Percentage change in voluntary wheel running between age 12 months (baseline) and 24 months (post-treatment). Aged untreated mice (A) showed greater activity decline than aged mice treated with donepezil for 6 months (A+D). n = 6-8 per group. Significant differences were determined by one-tailed t-test. Bars represent mean ± SE; significance = p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Donepezil treatment improves blood oxygenation in aged mice. SpO₂ in young (Y), aged untreated (A), and aged donepezil-treated (A+D) mice. Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc t-tests. n = 3-4 per group.

Figure 2.

Donepezil treatment improves blood oxygenation in aged mice. SpO₂ in young (Y), aged untreated (A), and aged donepezil-treated (A+D) mice. Mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc t-tests. n = 3-4 per group.

Figure 3.

Age-related changes to lung architecture. Lung sections stained with Modified Russell Movat Pentachrome. A: Young lung (age 4 months; n= 6). B: Aged control (24 months; n= 28). C: Aged donepezil-treated lungs (24 months; n= 20). Magnified images at right show evidence of age-related pulmonary pathology. Red arrow = alveolar tubule, green star = emphysematic alveoli; fuchsia circles = fibrin; purple arrow = iBALT. Imaged using a Keyence BZ-X810. Scale bar 500 µm, magnification 100x.

Figure 3.

Age-related changes to lung architecture. Lung sections stained with Modified Russell Movat Pentachrome. A: Young lung (age 4 months; n= 6). B: Aged control (24 months; n= 28). C: Aged donepezil-treated lungs (24 months; n= 20). Magnified images at right show evidence of age-related pulmonary pathology. Red arrow = alveolar tubule, green star = emphysematic alveoli; fuchsia circles = fibrin; purple arrow = iBALT. Imaged using a Keyence BZ-X810. Scale bar 500 µm, magnification 100x.

Figure 4.

Donepezil treatment preserves alveolar architecture. Mean alveolar area (MAA) in young (Y), aged untreated (A), and aged donepezil-treated (A+D) mice. A: Average MAA across all measured alveoli (~5,000 per lung; n= 15-21 per group). B: Violin plot showing distribution of individual alveolar sizes (n=4-6 representative lungs per group). (C-F): Average MAA within each quartile of the size distribution (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartiles, respectively; n=4-6 per group). Bars represent mean ± SE; *p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with pairwise t-tests.

Figure 4.

Donepezil treatment preserves alveolar architecture. Mean alveolar area (MAA) in young (Y), aged untreated (A), and aged donepezil-treated (A+D) mice. A: Average MAA across all measured alveoli (~5,000 per lung; n= 15-21 per group). B: Violin plot showing distribution of individual alveolar sizes (n=4-6 representative lungs per group). (C-F): Average MAA within each quartile of the size distribution (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartiles, respectively; n=4-6 per group). Bars represent mean ± SE; *p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with pairwise t-tests.

Figure 5.

Donepezil treatment restores pulmonary elastic fiber content. Quantification of extracellular matrix components in young (Y), aged (A), and aged donepezil-treated (A+D) lungs (Y: n=6, A: n= 21, A+D: n= 16). A: Fibrin deposition (% tissue area). B: Elastic fiber content (% tissue area.). Significant differences between the groups were determined by one-way ANOVA and one-tailed t-test. Bars represent mean ± SEM, significance= p<0.05.

Figure 5.

Donepezil treatment restores pulmonary elastic fiber content. Quantification of extracellular matrix components in young (Y), aged (A), and aged donepezil-treated (A+D) lungs (Y: n=6, A: n= 21, A+D: n= 16). A: Fibrin deposition (% tissue area). B: Elastic fiber content (% tissue area.). Significant differences between the groups were determined by one-way ANOVA and one-tailed t-test. Bars represent mean ± SEM, significance= p<0.05.

Figure 6.

Donepezil treatment increases iBALT. Representative histology of Picrosirius red (PSR)-stained lung sections from (A) young, (B) aged untreated, and (C) aged donepezil-treated mice. Black arrows indicate collagen; black circles highlight iBALT structures. (D) Total collagen (% tissue area) across entire lung. (E) Parenchymal collagen excluding iBALT. (F)Collagen density within iBALT structures. (G) Average individual iBALT follicle size (% of total tissue area). (H) Total iBALT area per lung (% of total tissue area). Groups: young (Y, n= 6), aged (A, n= 38), and aged donepezil-treated (A+D, n= 31). Bars represent mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with pairwise comparisons.

Figure 6.

Donepezil treatment increases iBALT. Representative histology of Picrosirius red (PSR)-stained lung sections from (A) young, (B) aged untreated, and (C) aged donepezil-treated mice. Black arrows indicate collagen; black circles highlight iBALT structures. (D) Total collagen (% tissue area) across entire lung. (E) Parenchymal collagen excluding iBALT. (F)Collagen density within iBALT structures. (G) Average individual iBALT follicle size (% of total tissue area). (H) Total iBALT area per lung (% of total tissue area). Groups: young (Y, n= 6), aged (A, n= 38), and aged donepezil-treated (A+D, n= 31). Bars represent mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA with pairwise comparisons.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).