Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

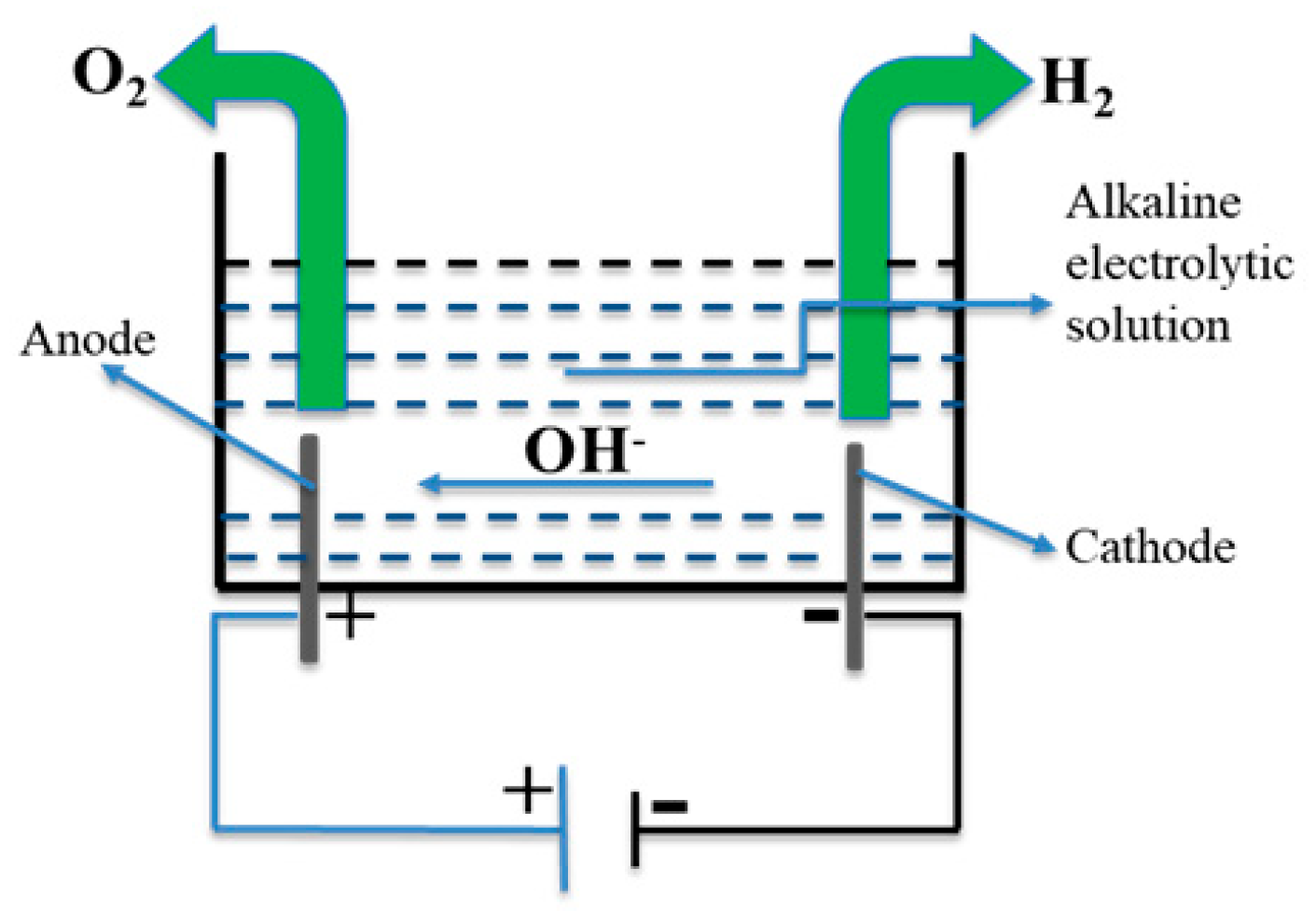

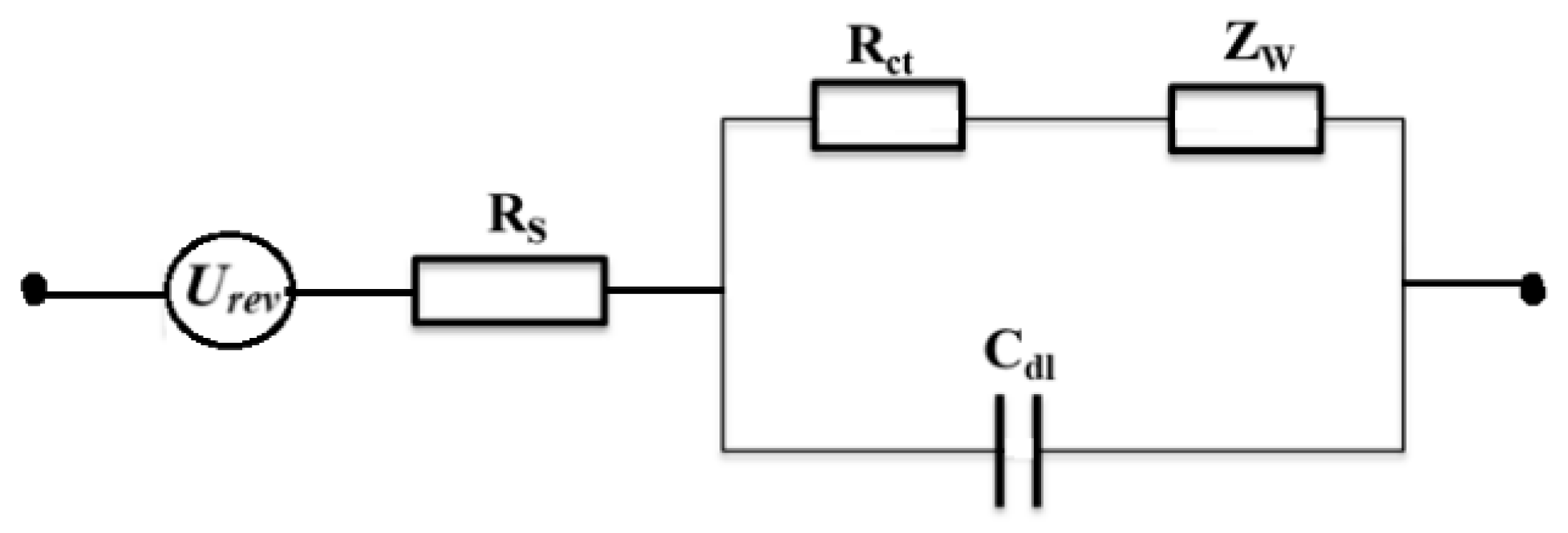

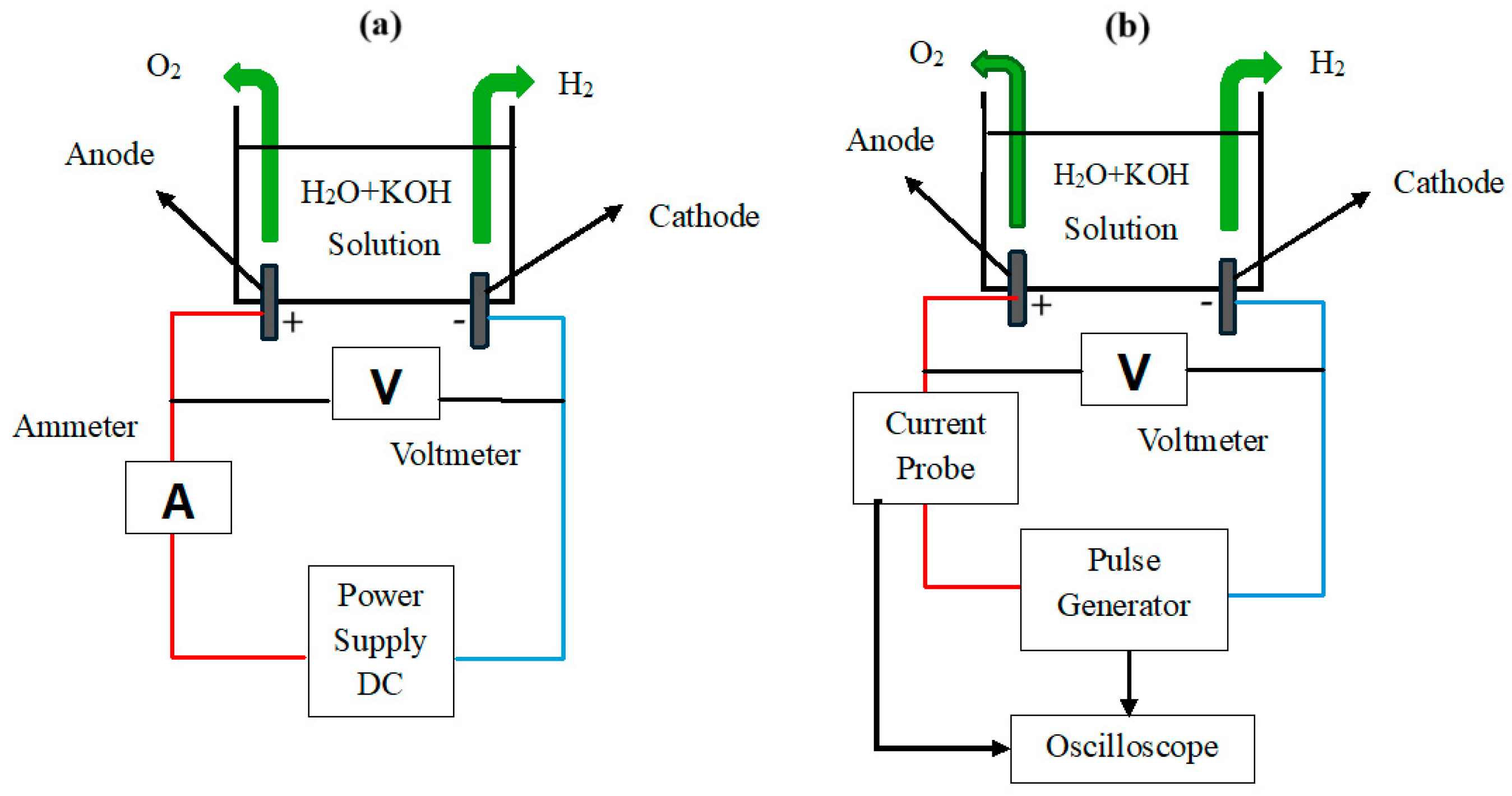

2.1. Conventional AWE

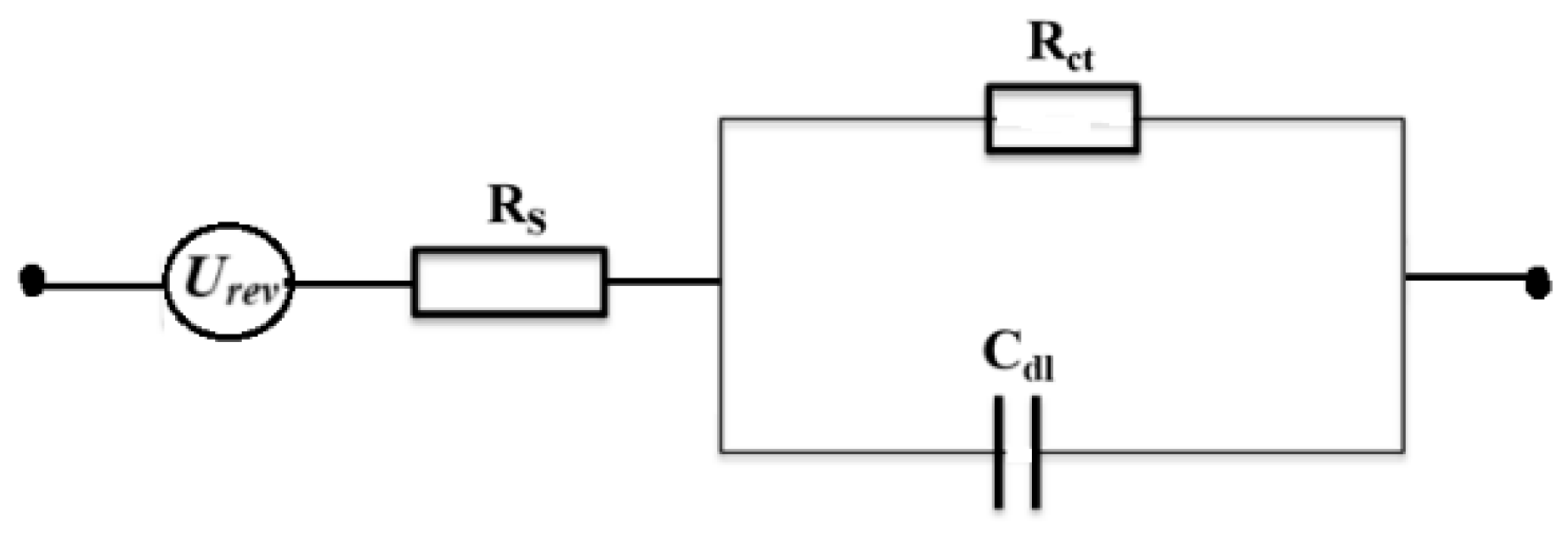

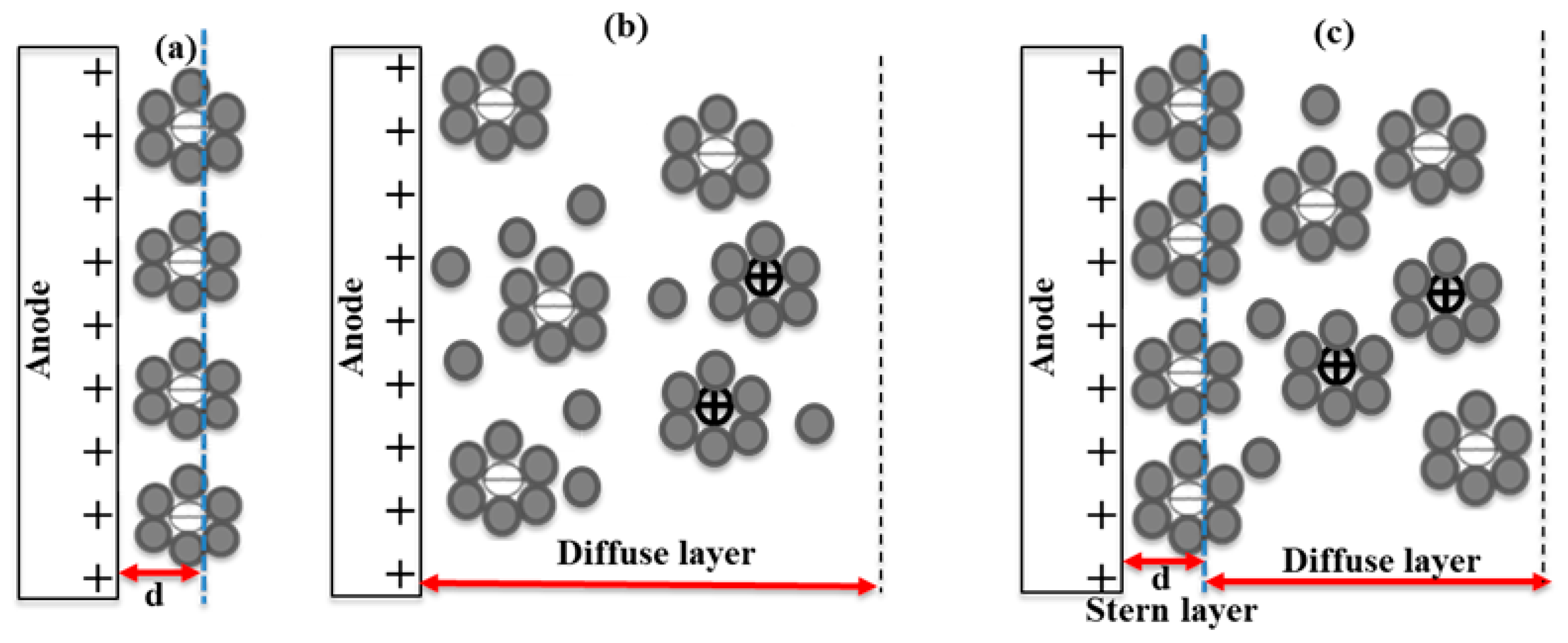

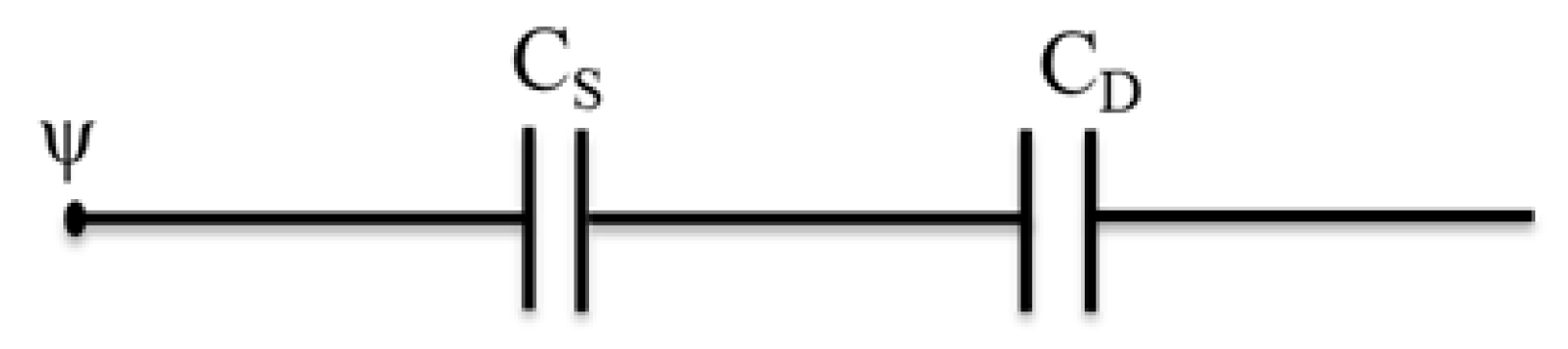

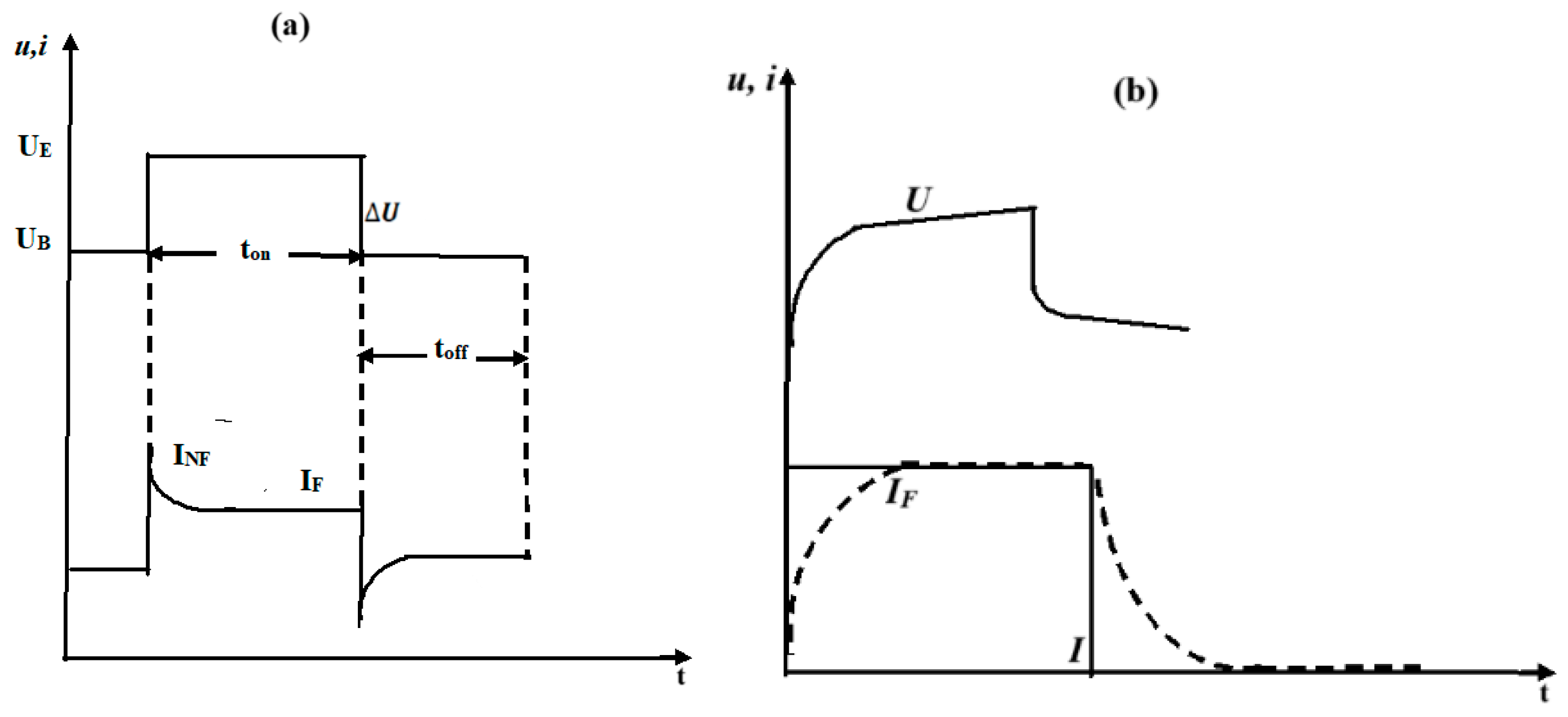

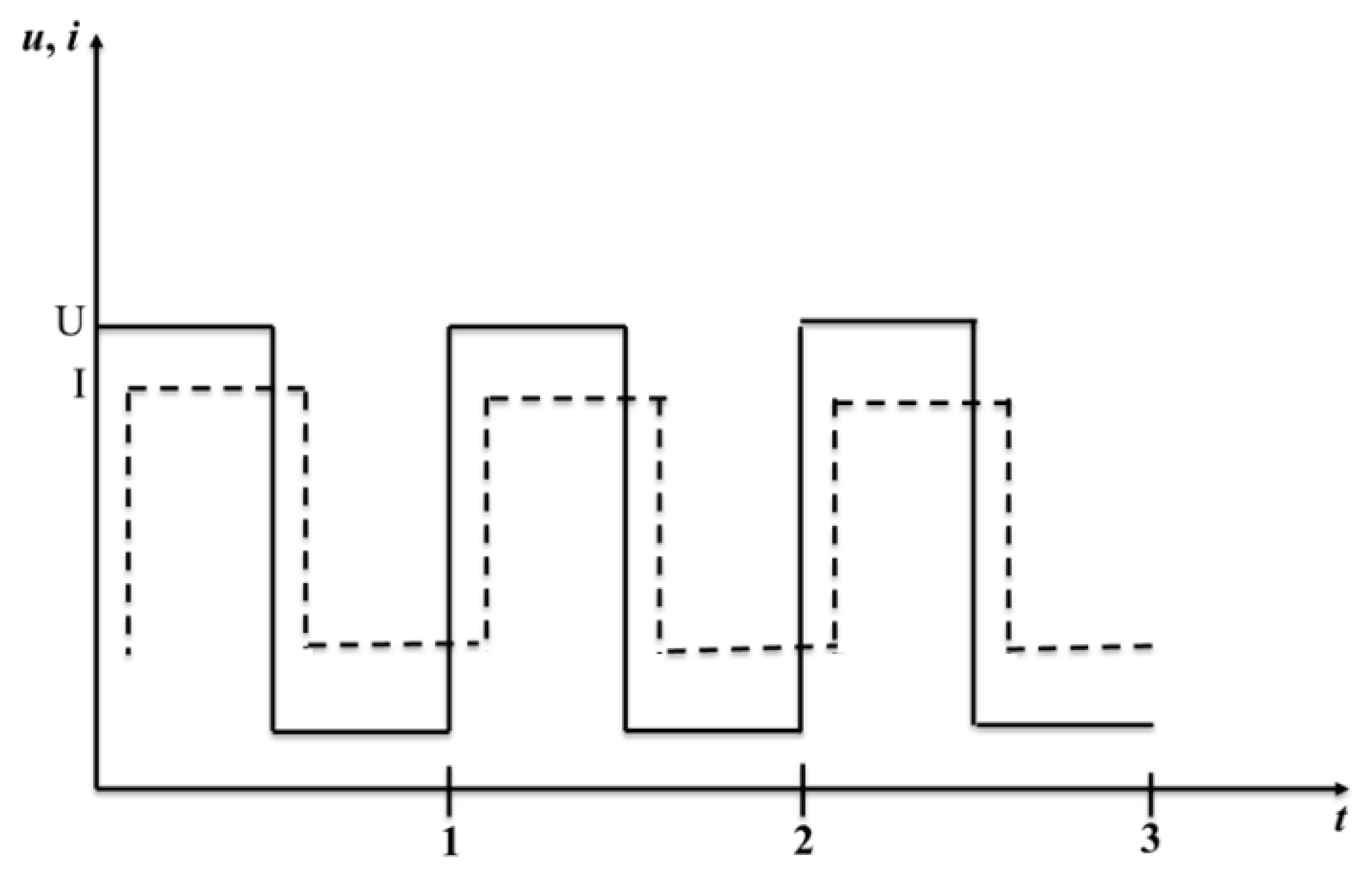

2.2. Electrical Double Layer and Pulsed AWE

3. Experimental

4. Results and Discussions

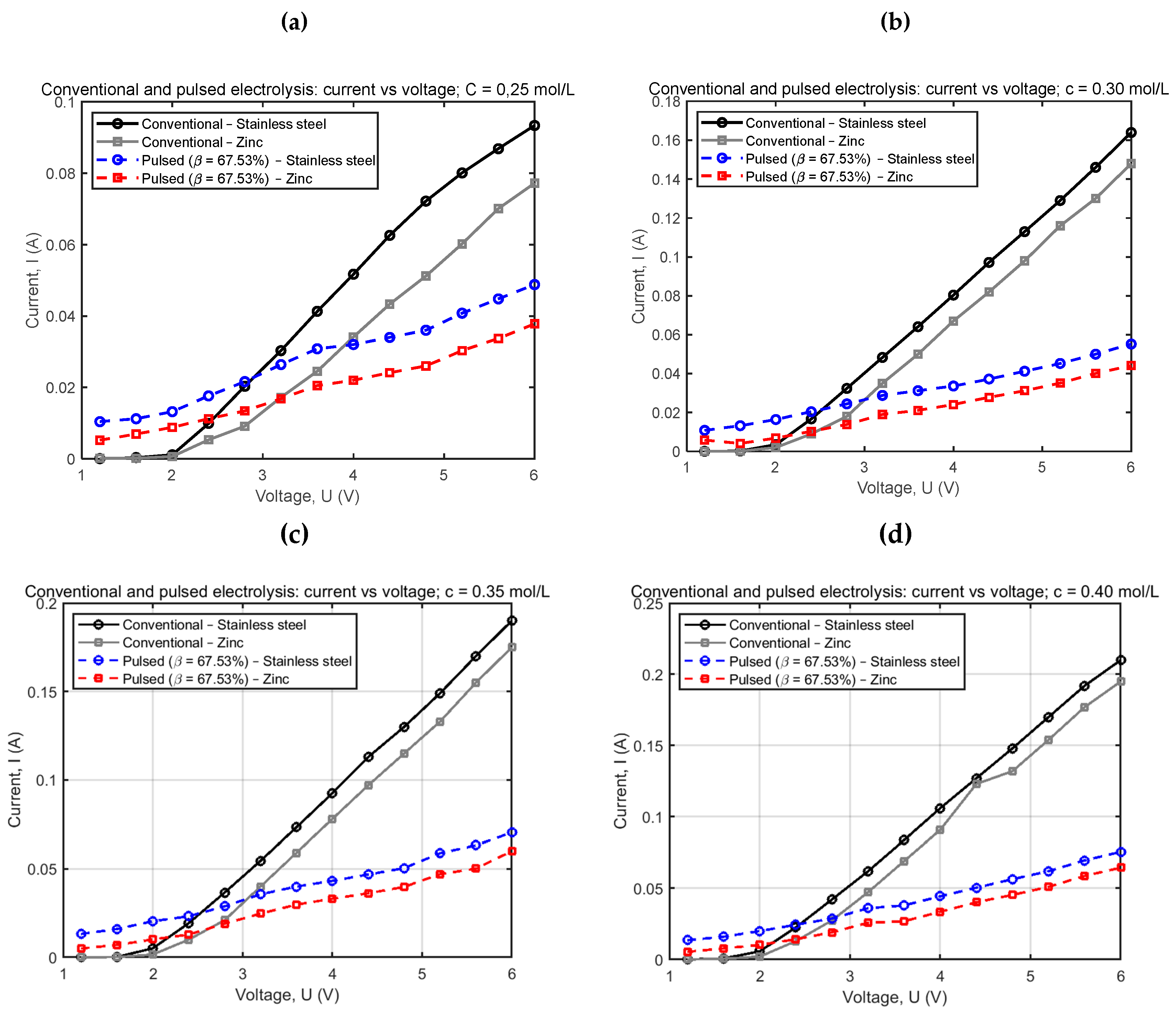

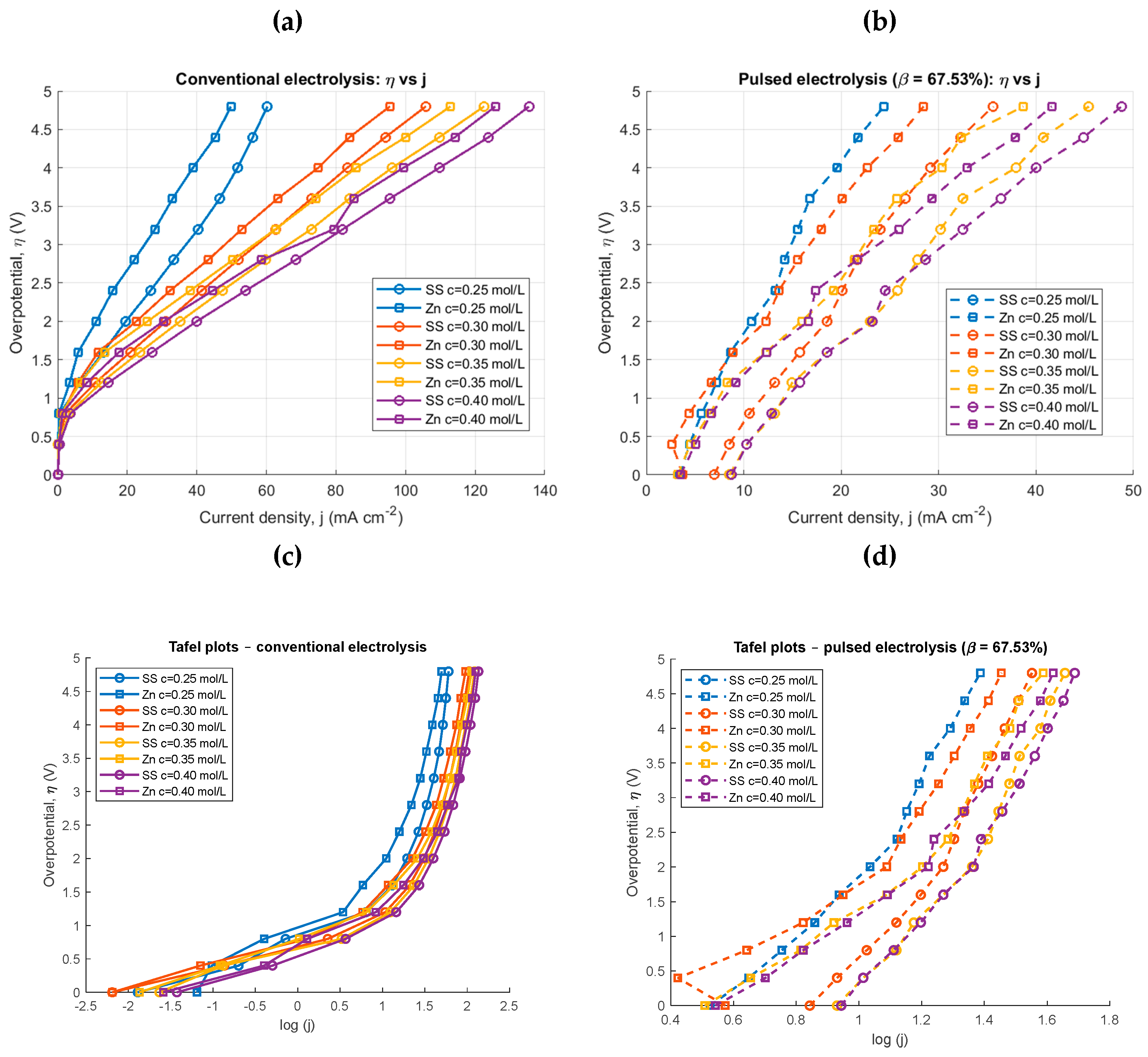

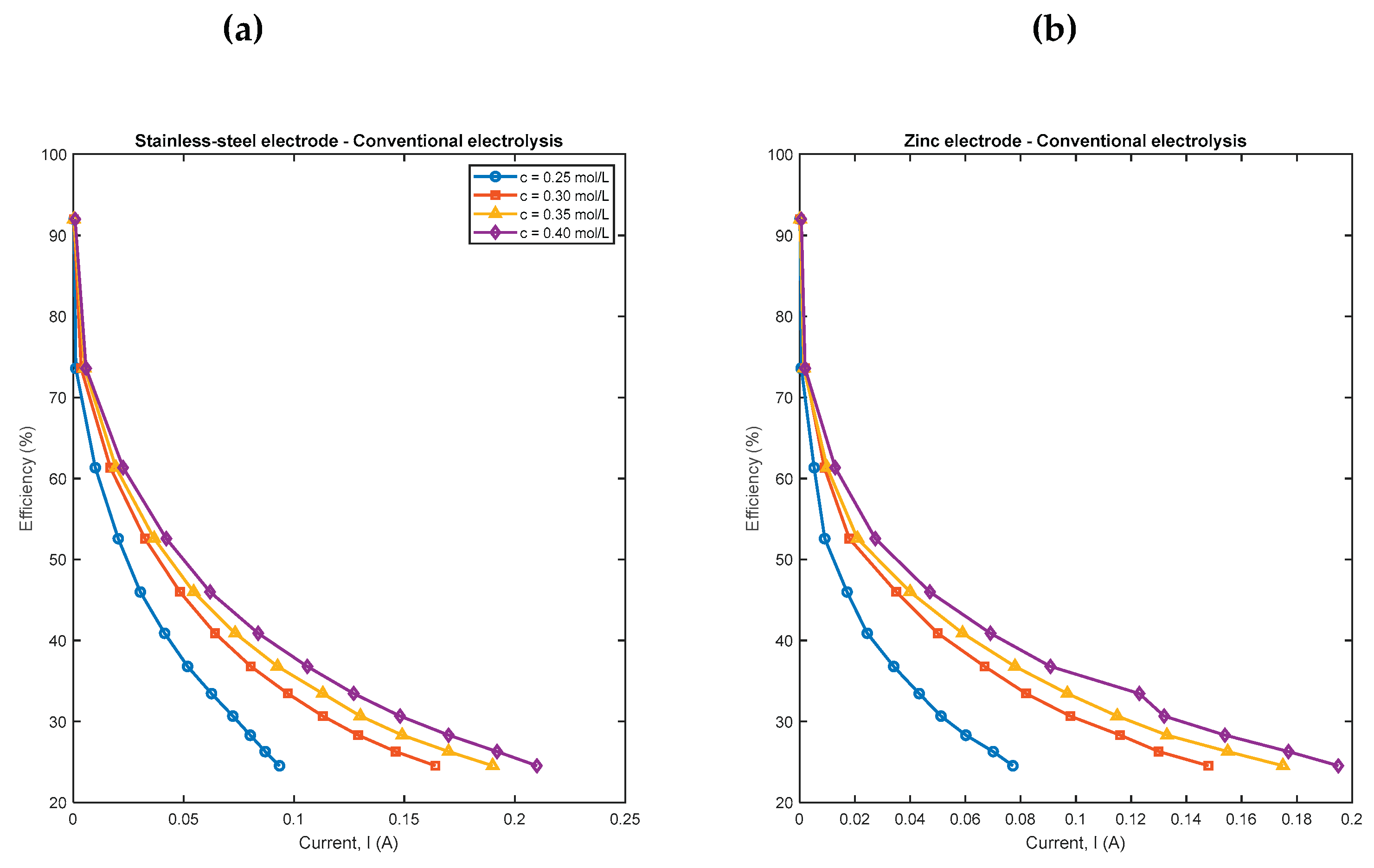

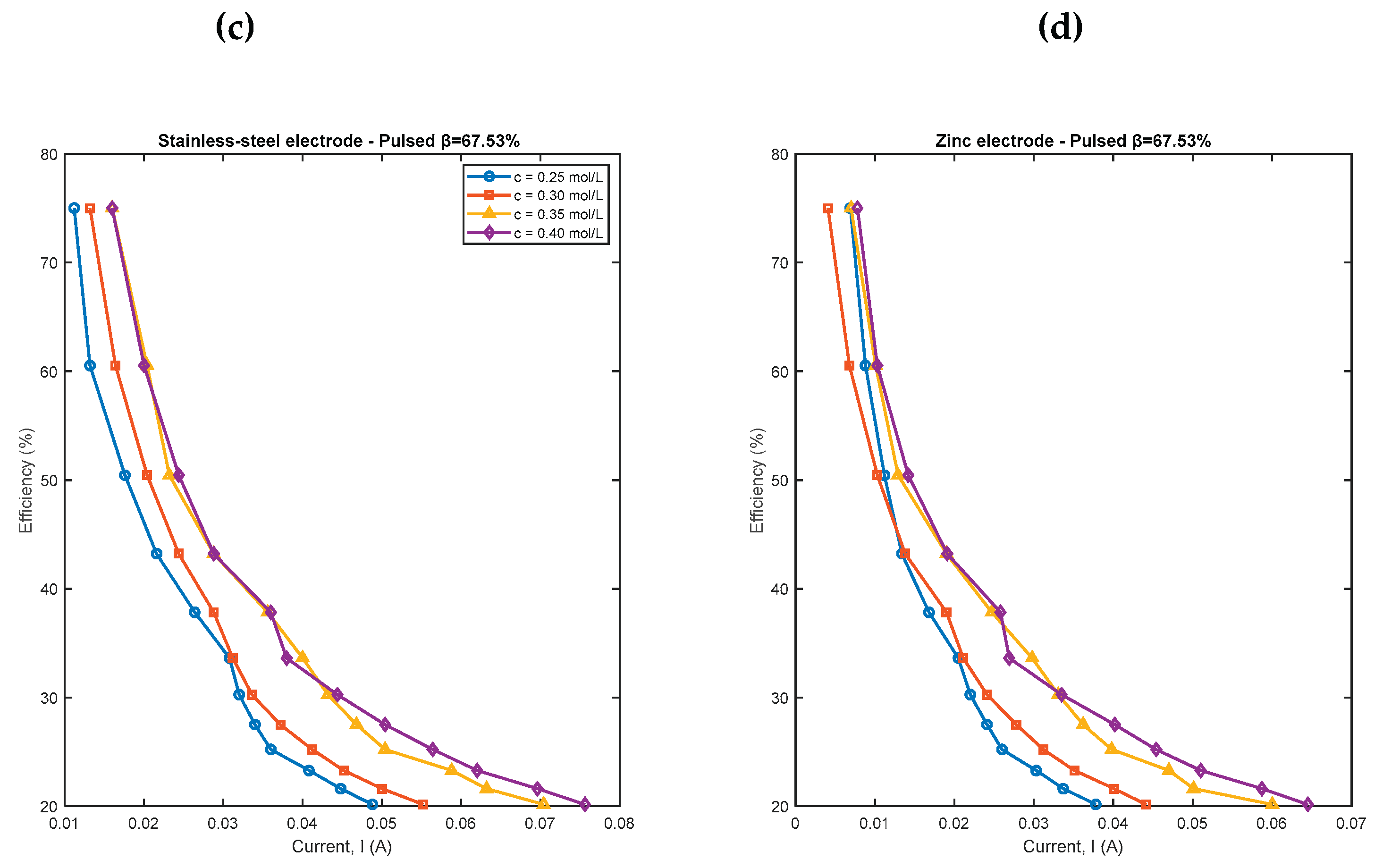

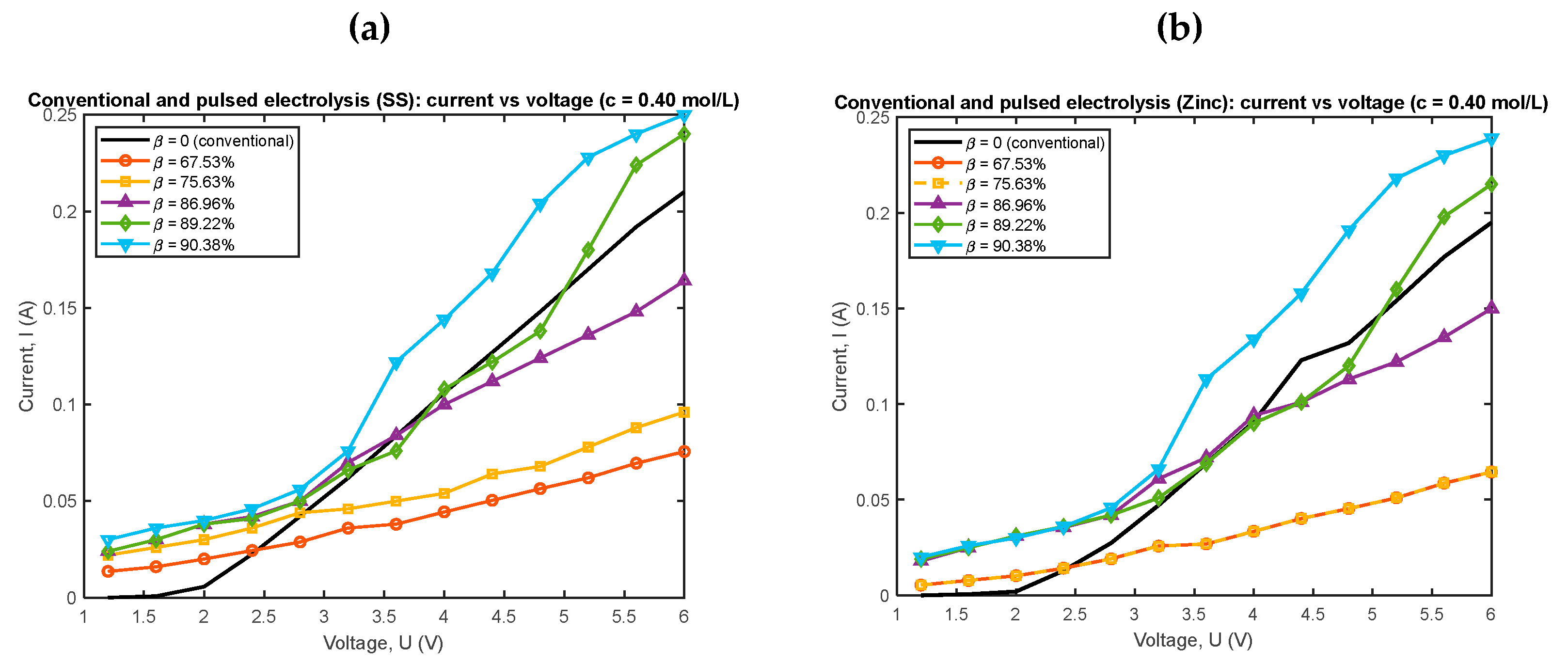

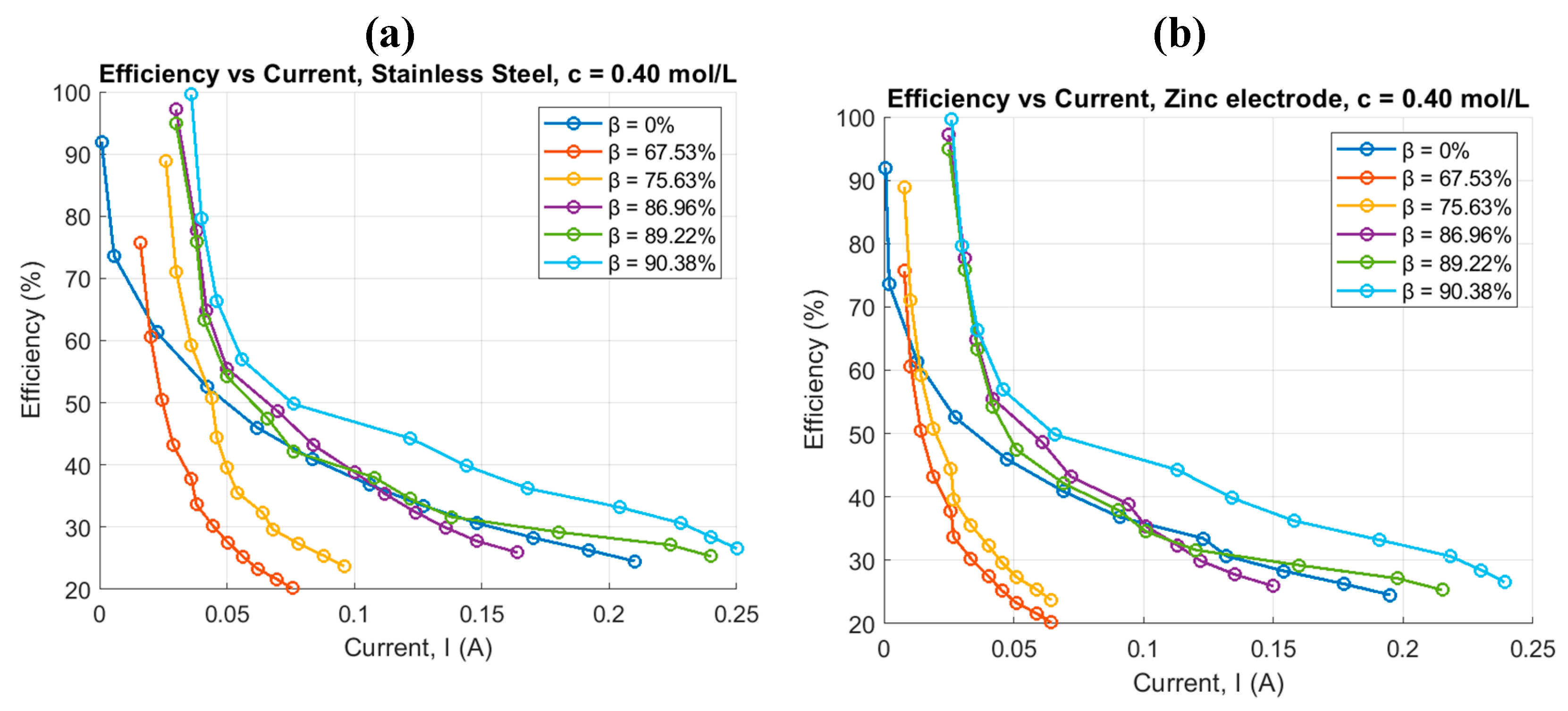

4.1. Conventional and Pulsed Electrolysis for Different Concentrations

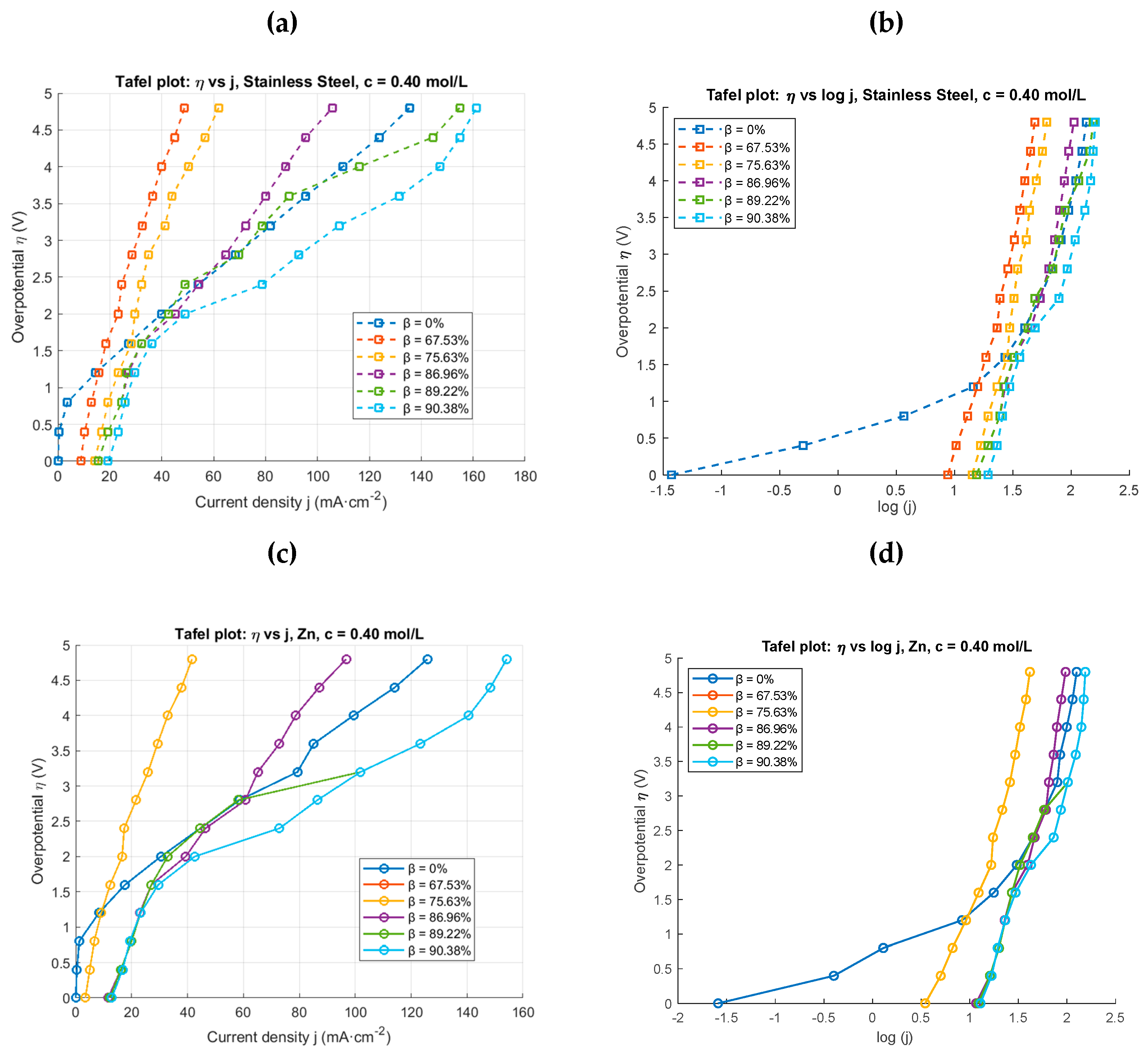

4.2. Pulsed Electrolysis at a Concentration and Different Duty Cycles

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- R. Lobo, “A Brief on Nano-Based Hydrogen Energy Transition,” Hydrogen, MDPI, pp. 679-693, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Lobo and M. Pinheiro, R. Lobo, in Advanced Topics in Contemporary Physics for Engineering: Nanophysics, Plasma Physics and Electrodynamics, Portugal: CRC Press-New York, ISBN 9781032247632, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Paulec, J. Tvarožek, P. Resutík, P. Špánik and M. Praženica, “Review of the Dynamic Response of Water Electrolyzers,” Electrical Engineering, vol. 107, pp. 10499-10506, 18 March 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. E. Conway, Electrochemical Supercapacitors: Scientific Fundamentals and Technological Applications, Springer, 1999. [CrossRef]

- GroB and S. Sakong, “Modelling the electric double layer at electrode-electrolyte interfaces,” Current Opinion in Electrochemistry - Elsevier, vol. 14, pp. 1-6, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. O. Bockris, A. K. N. Reddy, M. Gamboa-Aldeco and L. M. Peter, “Comprehensive Modern Electrochemistry : Modern Electrochemistry,” Platinum Metals Review, vol. 46, nº 1, pp. 15-17, 2002. [CrossRef]

- C. Haoran, X. Yanghong, H. Zhiyuan and W. Wei, “Optimum pulse electrolysis for efficiency enhancement of hydrogen production by alkaline water electrolyzers,” Applied Energy, vol. 358, p. 122512, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Pletcher and X. Li, “Prospects for alkaline zero gap water electrolysers for hydrogen production,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 36, pp. 15089-150104, 2011. [CrossRef]

- N. Colli, H. H. Girault and A. Battistel, “Non-Precious Electrodes for Practical Alkaline Water Electrolysis,” materials, MDPI, vol. 12, nº 1336, pp. 1-17, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Davida., C. Ocampo-Martínezc. and R. Sánchez-Peña., “Advances in alkaline water electrolyzers: A review,” Journal of Energy Storage, pp. 392-403, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Mabarak., S. Elmazouzi., D. Takky., Y. Naimi. e I. Colak, “Hydrogen Production by Water Electrolysis: Review,” em 12th IEEE International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications, Canada, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Vidas and R. Castro, “Recent Developments on Hydrogen Production Technologies: State-of-the-Art Review with a Focus on Green-Electrolysis,” Applied Sciences, MDPI, vol. 11363, p. 11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Decourt, B. Lajoie, R. Debarre and S. Olivier, Hydrogen-based energy conversion, Gravenhage, Netherlands: AT Kearney/ Energy Transition Institute, 2014. https://www.energy-transition-institute.com/documents/17779499/17781876/Hydrogen+Based+Energy+Conversion_FactBook.pdf.

- M. Faraday, “ On Electrical Decomposition,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, vol. 124, pp. 77-124, 1834. On electro-chemical decomposition, continued : Faraday, Michael, 1791-1867 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.

- S. Bespalko. and J. Mizeraczyk, “Overview of the Hydrogen Production by Plasma-Driven Solution Electrolysis,” energies, MDPI, nº 7508, p. 15, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. K. A. L. W. L. U. L. Lange, “Technical evaluation of the flexibility of water electrolysis systems to increase energy flexibility: A review,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, pp. 1571-1583, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Pinskya, P. Sabharwallb, J. Hartvigsenb and J. O. O’Brien, “Comparative Review of Hydrogen Production Technologies for Nuclear Hybrid Energy Systems,” Progress in Nuclear Energy, vol. 123, nº 103317, p. 16, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Marangio, M. Santarelli and M. Cali, “Theoretical model and experimental analysis of a high pressure PEM water electrolyser for hydrogen,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, pp. 1143-1158, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Ø. Ulleberg, “Modelagem de eletrolisadores alcalinos avançados: uma abordagem de simulação de sistemas,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 28, nº 1, pp. 21-33, 2003. [CrossRef]

- S. Tijani, N. A. B. Yusup and A. H. A. Rahim., “Mathematical modelling and simulation analysis of advanced alkaline electrolyzer system for hydrogen production,” Procedia Technology, vol. 15, pp. 798-806, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Yodwong, D. Guilbert, M. Oliveira, W. Kaewmanee, M. Hinaje and G. Vitale, “Performance modeling of PEM electrolyzer for hydrogen production using solar PV electricity under varying environmental conditions,” Energies, 13, 4792, MDPI, p. 14, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Carmo, D. L. Fritz, J. Mergel and a. D. Stolten, “A Comprehensive Review on PEM Water Electrolysis,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 38, nº 12, pp. 4901-4934, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ø. G. Martinsen. and A. Heiskanen, “Electrical double layer,” em Basics of Bioimpedance and Bioelectricity (fourth edition), 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Burt, G. Birkett and X. S. Zhao, “A review of molecular modelling of electric double layer capacitors,” Royal Society of Chemistry, vol. 16, pp. 6519-6538, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Gouy, “Sur la constitution de la charge électrique à la surface d’un électrolyte,” Journal de physique théorique appliquée, vol. 9, nº 1, pp. 447-458, 1910. [CrossRef]

- D. Chapman, “LI. A contribution to the theory of electrocapillarity,” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Review and Journal of Science, vol. 25, pp. 475-481, 1913. [CrossRef]

- H. Stern, “ZUR THEORIE DER ELEKTROLYTISCHEN DOPPELSCHICHT,” ZITSCHRITFT FUR ELEKTROCHEME, vol. 30, pp. 508-516, 1924. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Ebaid, M. Hammad and T. Alghamdi, “Thermoeconomic analysis of a 100 MW hybrid photovoltaic and hydrogen gas turbine power plant.,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 40, nº 36, pp. 12120-12143, 2015. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Ruiz and C. J. Felice, “Electrochemical-Fractal Model Versus Randles Model: A Discussion About Diffusion Process,” International Journal of Electrochemical Science, pp. 8484-8496, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Orazem and B. Tribollet, Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy; ISBN:9780470381588, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008. [CrossRef]

- H. Fricke, “The theory of electrolytic polarization,” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, vol. 14, nº 90, pp. 310-318, 1932. [CrossRef]

- C. Lim, “Transport Phenomena. Warburg Impedance,” MIT OpenCourseWare. https://ocw.mit.edu, acess: 25.11.2025, 2014. 10.626 Lecture Notes, Transient diffusion.

- L. Geddes and L. E. Baker, Principles of Applied Biomedical Instrumentation, 3rd edition, New York: John Wiley, LC: 88-27915; ISBN: 9780471608998; ISBN: 0471608998, 1989, pp. 853, chap. 13.

- E. Barsoukov and J. R. Macdonald, Impedance Spectroscopy: Theory, Experiment, and Applications - 2nd Edition. ISBN: 0-471-64749-7, Hoboken, New Jersey.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. Bard and L. R. Faulker, Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications - 2nd Edition. ISBN 0-471-04372-9, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2001. https://books.google.co.ao/books?id=eZ6HDAEACAAJ.

- F. Rocha, Q. Radiguès, G. Thunis and J. Proost, “Pulsed water electrolysis: A review,” Electrochimica Acta, pp. 20, 377, 138052, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J.-H. Kim, C.-Y. Oh, K.-R. Kim, J.-P. Lee and T.-J. Kim, “Electrical Double Layer Mechanism Analysis of PEM Water Electrolysis for Frequency Limitation of Pulsed Currents,” Energies, MDPI, vol. 14, nº 7822, p. 17, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. C. Cheg, Y. Xia, Z. Hu and W. Wei, “Optimum pulse electrolysis for effciency enhancement of hydrogen production by alkaline water electrolyzers,” Applied Energy, vol. 358, nº 122510, p. 10, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Puranen, V. Ruuskanen, L. Järvinen, M. Niemelä, A. Kosonen, P. Kauranen and J. Ahola, “Calculating active power for waterelectrolyzers in dynamicoperation: Simple, isn’t it?,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 91, pp. 267-271, 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Emanuel, Power Definitions and the Physical Mechanism of Power Flow, New Jersey, USA: Wiley, 2010. ISBN: 978-0-470-68399-8, 2010. [CrossRef]

- F. T. Ulaby and U. Ravaioli, Fundamentals of Applied Electromagnetics (8th ed.), London, UK: Person, 2023. Fundamentals of Applied Electromagnetics, Global Edition, 8/ed.

- P. Horowitz and W. Hill, The Art of Electronics (3rd ed.), Cambridge University Press, 2015. new08_popular_opamp_noise_plots_fullpageheight.

- N. Monk and S. Watson, “REVIEW OF PULSED POWER FOR EFFICIENT HYDROGEN PRODUCTION,” CORE, p. 15, 2016. 288373965.pdf.

- T. Paulec, P. Špánik, J. Tvarožek and M. Praženica, “Design of the Converter Prototype for Powering the Hydrogen Electrolyzer,” MDPI, Applied Science, 15, 2601, 2025. [CrossRef]

- V. Solorio and et.al, “Investigation of Pore Size on the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction of 316L Stainless Steel Porous Electrodes,” catalysts, MDPI, vol. 15, nº 38, pp. 1-14, 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Basori, W. Mohamad, M. Mansor, N. Tamaldin, A. Iswadi, M. Ajiriyanto and F. Susetyo, “Effect of KOH concentration on corrosion behavior and surface morphology of stainless steel 316L for HHO generator application,” J. Electrochem. Sci. Eng., vol. 13, nº 3, pp. 451-457, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Jiang, H. Huang and Q. e. a. Ji, “Investigation of high current density on zinc electrodeposition and anodic corrosion in zinc electrowinning,” J Solid State Electrochem, vol. 26, pp. 1455-1467, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Miličić, S. M. C. Blümner, A. Sorrentino and T. Vidaković-Koch, “Pulsed electrolysis – explained,” RSC Publishing, vol. 246, pp. 179-197, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Barauskien, G. Laukaitis and E. Valatka, “Stainless steel as an electrocatalyst for overall water splitting under alkaline and neutral conditions,” Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, vol. 950, 2023. [CrossRef]

| Conventional electrolysis | Pulsed electrolysis | |||||||

|

SS |

c (mol/L) | RS (Ω) | Rct (Ω) | I0 (µA) | c(mol/L) | RS (Ω) | Rct (Ω) | I0 (mA) |

| 0.25 | 60.14 | 540.77 | 23.4 | 0.25 | 100 | 1.23 | 10.24 | |

| 0.30 | 22.85 | 1118.69 | 11.3 | 0.30 | 79.96 | 1.17 | 10.77 | |

| 0.35 | 19.51 | 485.15 | 26.0 | 0.35 | 67.65 | 0.97 | 13.08 | |

| 0.40 | 19.93 | 199.39 | 63.3 | 0.40 | 58.56 | 0.94 | 13.44 | |

|

Zinc |

0.25 | 19.42 | 269.85 | 46.78 | 0.25 | 587.87 | 2.31 | 5.47 |

| 0.30 | 19.03 | 597.20 | 21.14 | 0.30 | 56.40 | 2.54 | 4.97 | |

| 0.35 | 24.87 | 1383.60 | 91.24 | 0.35 | 88.53 | 5.37 | 2.35 | |

| 0.40 | 46.64 | 164.18 | 76.89 | 0.40 | 106.36 | 2.41 | 5.23 | |

| Conventional electrolysis | Pulsed electrolysis, c = 0.40 mol/L | |||||||

|

SS |

c (mol/L) | RS (Ω) | Rct (Ω) | I0 (µA) | β (%) | RS (Ω) | Rct (Ω) | I0 (mA) |

|

0.40 |

19.93 |

199.39 |

63.3 |

67.53 | 58.56 | 0.94 | 13.44 | |

| 75.63 | 14.46 | 0.57 | 22.2 | |||||

| 86.96 | 28.38 | 0.53 | 23.9 | |||||

| 89.22 | 12.43 | 0.53 | 23.9 | |||||

| 90.38 | 36.26 | 0.42 | 30.1 | |||||

|

zinc |

0.40 |

46.64 |

164.18 |

76.89 |

67.53 | 106.36 | 2.41 | 5.23 |

| 75.63 | 58.87 | 3.58 | 3.53 | |||||

| 86.96 | 28.53 | 1.07 | 11.79 | |||||

| 89.22 | 13.87 | 1.02 | 12.37 | |||||

| 90.38 | 37.84 | 0.96 | 13.09 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).