Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

23 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

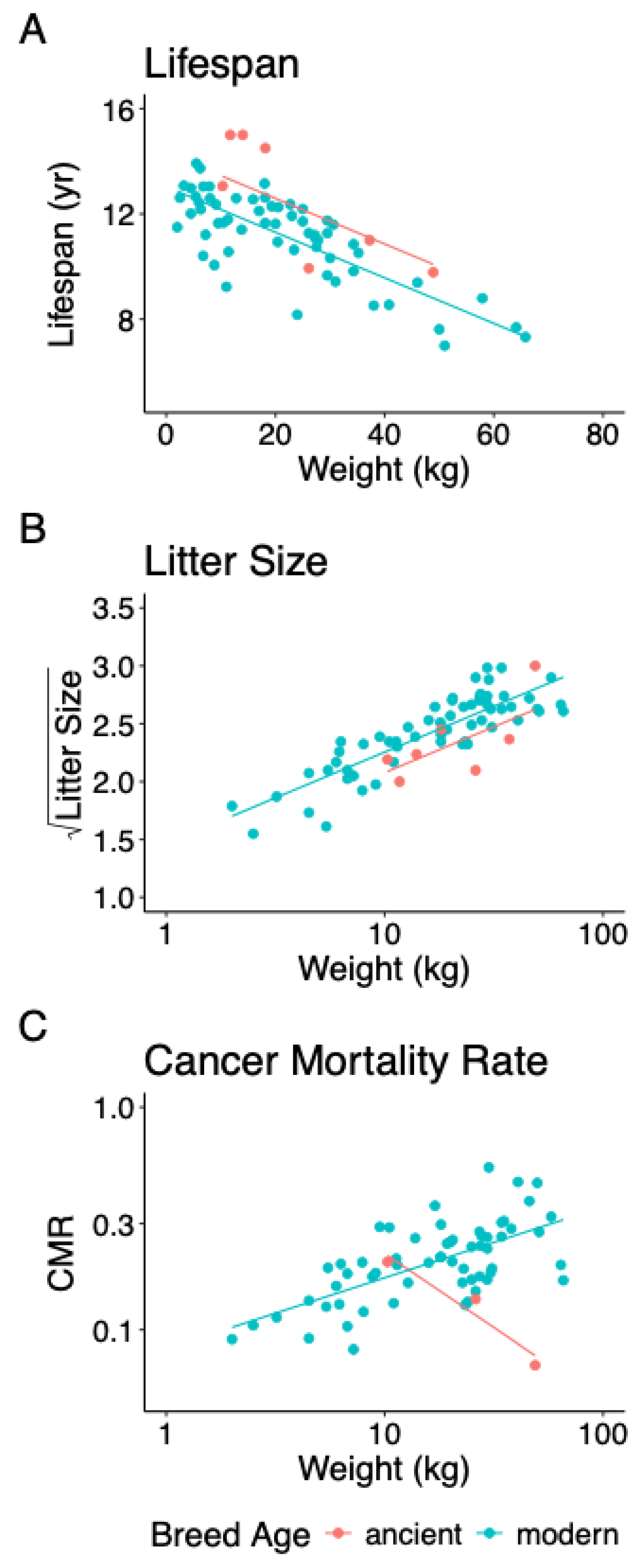

Background/Objectives: The well-established inverse relationship between lifespan and weight across dog breeds is associated with higher cancer mortality in larger breeds. However, Peto’s Paradox implies that larger-bodied species experience lower than expected cancer mortality because of higher levels of cancer suppression. Therefore, it has been hypothesised that recently established large dog breeds experience high cancer mortality because of a lag in their evolution of cancer suppression. This “adaptive lag hypothesis” predicts that ancient breeds, which have had more time to evolve optimal cancer suppression, exhibit lower cancer mortality rates, longer lifespans, and smaller litter sizes (a cost of cancer suppression) compared to modern breeds of the same size. Methods: The adaptive lag hypothesis is tested here by comparing ancient and modern breeds defined by their levels of modern European genetic admixture. Results: Ancient breeds have significantly longer lifespans and smaller litters than modern breeds of the same size after controlling for phylogenetic relationships. The sparse data on cancer mortality rates of ancient breeds do not allow a definitive test of a difference between ancient and modern breeds, but ancient breeds show a significant departure from the increase in cancer mortality rate with weight observed for modern breeds. Conclusions: The results are consistent with the adaptive lag hypothesis, that the evolution of cancer suppression in large modern dog breeds has lagged behind their increased risk of cancer, thus shortening their lives compared to smaller breeds and compared to ancient breeds of the same size.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

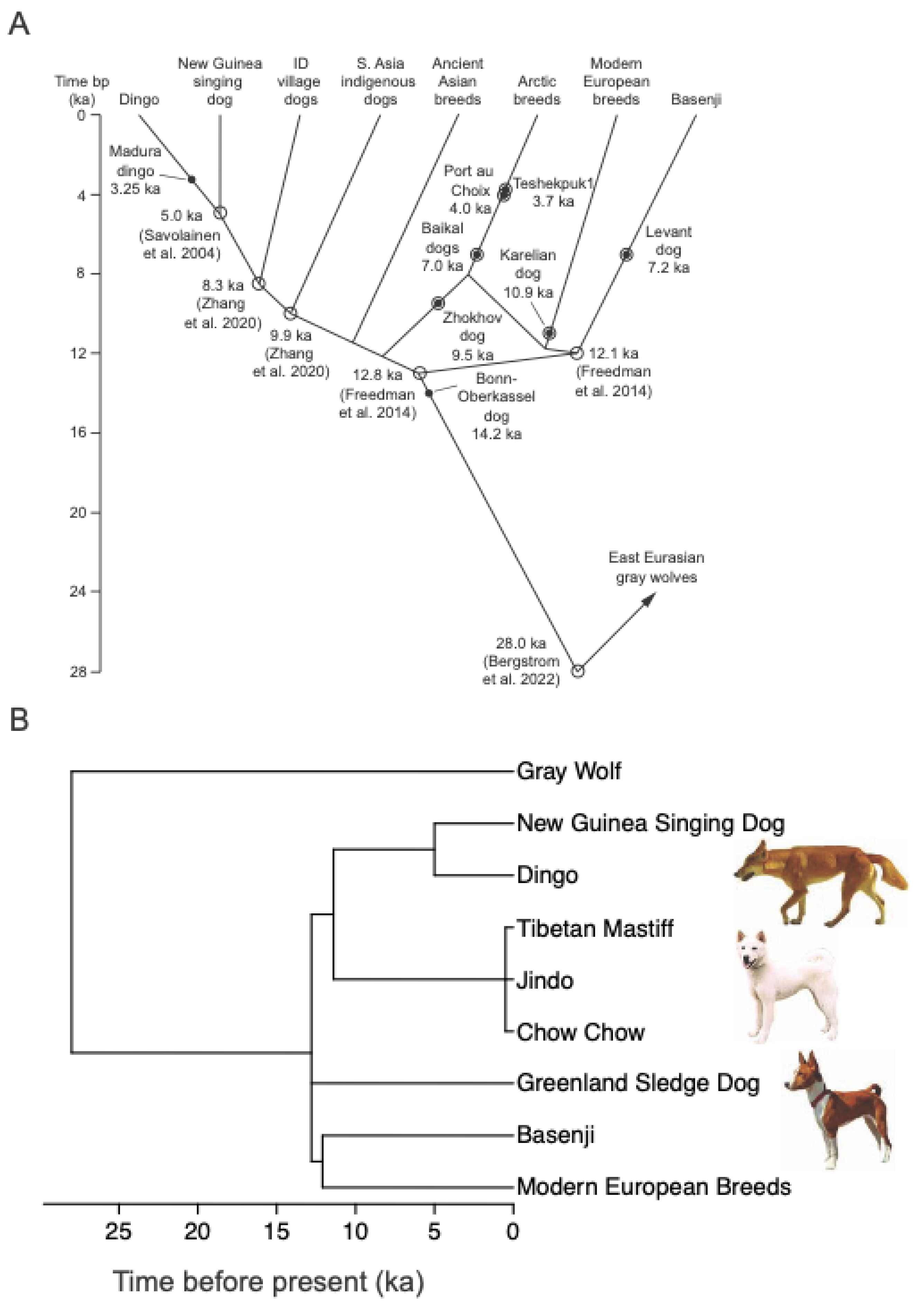

2.1. Identification of Ancient and Modern Breeds

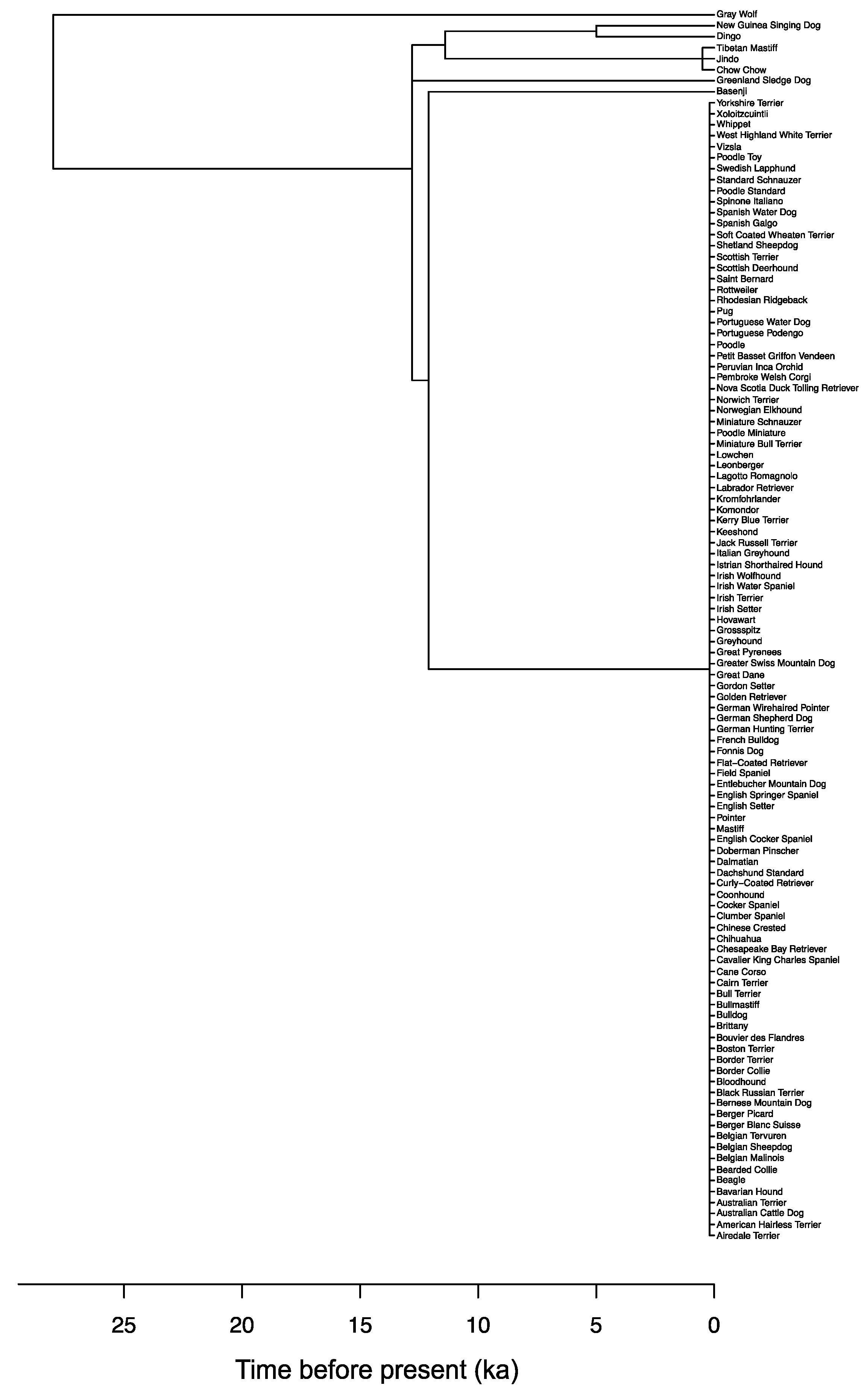

2.2. Ancient Breed Lineages and Phylogeny

2.3. Breed Life History Data

2.4. Phylogenetic Comparative Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Lifespan

3.2. Litter Size

3.3. Cancer Mortality Rate

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGLS | Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares |

| LRS | Lifetime Reproductive Success |

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Breed | Modern European Admixture (%) | Mean Adult Mass (kg)* | Litter Size* | Midpoint Life Expectancy (yr)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basenji | 15.3 | 10.43 [68] | 4.8 [56] | 13.5 [68] |

| Chow Chow | 13.1 | 26.08 [68] | 4.4 [56] | 10 [68] |

| Dingo (captive) | 7.0 | 14 [69] | 5 [69] | 15 [70] |

| Greenland Sledge Dog | 17.0 | 37.25 [71] | 5.6 [56] | 11 [72] |

| Jindo | 10.1 | 18.14 [68] | 6 [73] | 14.5 [68] |

| New Guinea Singing Dog (captive) | 0.3 | 11.7 [69] | 4 [74] | 15 [75] |

| Tibetan Mastiff | 5.1 | 48.76 [68] | 9 [76] | 11 [68] |

References

- da Silva, J.; Cross, B.J. Dog life spans and the evolution of aging. The American Naturalist 2023, 201, E000–E000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, J.M.; Creevy, K.E.; Promislow, D.E.L. Mortality in North American dogs from 1984 to 2004: An investigation into age-, size-, and breed-related causes of death. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2011, 25, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.A.; Waclaw, B. Cancer genes, environment, and “bad luck”. Science 2017, 355, 1266–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetti, C.; Li, L.; Vogelstein, B. Stem cell divisions, somatic mutations, cancer etiology, and cancer prevention. Science 2017, 355, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetti, C.; Vogelstein, B. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science 2015, 347, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.A. Somatic evolutionary genomics: Mutations during development cause highly variable genetic mosaicism with risk of cancer and neurodegeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 1725–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.A.; Nowak, M.A. Problems of somatic mutation and cancer. Bioessays 2004, 26, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunney, L. Lineage selection and the evolution of multistage carcinogenesis. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 1999, 266, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunney, L. The population genetics of multistage carcinogenesis. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 2003, 270, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunney, L. Size matters: height, cell number and a person’s risk of cancer. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2018, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Lee, D.H.; Han, K.-D.; Yoon, H.; Shin, C.M.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, N. Adult height in relation to risk of cancer in a cohort of 22,809,722 Korean adults. British Journal of Cancer 2019, 120, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Cairns, B.J.; Casabonne, D.; Wright, F.L.; Reeves, G.; Beral, V. Height and cancer incidence in the Million Women Study: prospective cohort, and meta-analysis of prospective studies of height and total cancer risk. Lancet Oncology 2011, 12, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunney, L. The effect of body size and inbreeding on cancer mortality in breeds of the domestic dog: a test of the multi-stage model of carcinogenesis. R Soc Open Sci 2024, 11, 231356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austad, S.N.; Fischer, K.E. Mammalian aging, metabolism, and ecology: evidence from the bats and marsupials. Journal of Gerontology 1991, 46, B47–B53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, B.A.; Cayuela, H.; Janzen, F.J.; Lemaître, J.-F.; Gaillard, J.-M.; Lawing, A.M.; Iverson, J.B.; Christiansen, D.G.; Martínez-Solano, I.; Sánchez-Montes, G.; et al. Diverse aging rates in ectothermic tetrapods provide insights for the evolution of aging and longevity. Science 2022, 376, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austad, S.N. Animal size, metabolic rate, and survival, among and within species. In The Comparative Biology of Aging; Wolf, N.S., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2010; pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Speakman, J.R. Body size, energy metabolism and lifespan. Journal of Experimental Biology 2005, 208, 1717–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, O.; Colchero, F.; Lemaitre, J.F.; Conde, D.A.; Pavard, S.; Bieuville, M.; Urrutia, A.O.; Ujvari, B.; Boddy, A.M.; Maley, C.C.; et al. Cancer risk across mammals. Nature 2022, 601, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peto, R. Quantitative implications of the approximate irrelevance of mammalian body size and lifespan to lifelong cancer risk. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2015, 370, 20150198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegglen, L.M.; Caulin, A.F.; Chan, A.; Lee, K.; Robinson, R.; Campbell, M.S.; Kiso, W.K.; Schmitt, D.L.; Waddell, P.J.; Bhaskara, S. Potential mechanisms for cancer resistance in elephants and comparative cellular response to DNA damage in humans. The Journal of the American Medical Association 2015, 314, 1850–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, Z.T.; Mellon, W.; Harris, V.K.; Rupp, S.; Mallo, D.; Kapsetaki, S.E.; Wilmot, M.; Kennington, R.; Noble, K.; Baciu, C.; et al. Cancer prevalence across vertebrates. Cancer Discovery 2024, OF1–OF18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulls, S.; Platner, L.; Ayub, W.; Moreno, N.; Arditi, J.-P.; Dreyer, S.; McCain, S.; Wagner, P.; Burgstaller, S.; Davis, L.; et al. Cancer prevalence is related to body mass and lifespan in tetrapods and remarkably low in turtles. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, G.; Baker, J.; Amend, S.R.; Pienta, K.J.; Venditti, C. No evidence for Peto’s paradox in terrestrial vertebrates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2025, 122, e2422861122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroi, A.M.; Koufopanou, V.; Burt, A. Cancer selection. Nature Reviews Cancer 2003, 3, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulin, A.F.; Maley, C.C. Peto’s Paradox: evolution’s prescription for cancer prevention. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2011, 26, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunney, L. Resolving Peto’s paradox: Modeling the potential effects of size-related metabolic changes, and of the evolution of immune policing and cancer suppression. Evolutionary Applications 2020, 13, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seluanov, A.; Gladyshev, V.N.; Vijg, J.; Gorbunova, V. Mechanisms of cancer resistance in long-lived mammals. Nature Reviews Cancer 2018, 18, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollis, M.; Schiffman, J.D.; Boddy, A.M. Evolution of cancer suppression as revealed by mammalian comparative genomics. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 2017, 42, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollis, M.; Schneider-Utaka, A.K.; Maley, C.C. The evolution of human cancer gene duplications across mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2020, 37, 2875–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagan, A.; Baez-Ortega, A.; Brzozowska, N.; Abascal, F.; Coorens, T.H.H.; Sanders, M.A.; Lawson, A.R.J.; Harvey, L.M.R.; Bhosle, S.; Jones, D.; et al. Somatic mutation rates scale with lifespan across mammals. Nature 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunney, L. The real war on cancer: The evolutionary dynamics of cancer suppression. Evolutionary Applications 2013, 6, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galis, F.; Van Der Sluijs, I.; Van Dooren, T.J.M.; Metz, J.A.J.; Nussbaumer, M. Do large dogs die young? Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 2007, 308B, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, T.B.L.; Rose, M.R. Evolution of senescence: late survival sacrificed for reproduction. Philosophical Transactions - Royal Society of London, B 1991, 332, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dujon, A.M.; Boutry, J.; Tissot, S.; Lemaitre, J.F.; Boddy, A.M.; Gerard, A.L.; Alvergne, A.; Arnal, A.; Vincze, O.; Nicolas, D.; et al. Cancer susceptibility as a cost of reproduction and contributor to life history evolution. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartke, A. Growth hormone and aging. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders 2021, 22, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrander, E.A.; Wayne, R.K.; Freedman, A.H.; Davis, B.W. Demographic history, selection and functional diversity of the canine genome. Nature Reviews Genetics 2017, 18, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plassais, J.; Kim, J.; Davis, B.W.; Karyadi, D.M.; Hogan, A.N.; Harris, A.C.; Decker, B.; Parker, H.G.; Ostrander, E.A. Whole genome sequencing of canids reveals genomic regions under selection and variants influencing morphology. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plassais, J.; vonHoldt, B.M.; Parker, H.G.; Carmagnini, A.; Dubos, N.; Papa, I.; Bevant, K.; Derrien, T.; Hennelly, L.M.; Whitaker, D.T.; et al. Natural and human-driven selection of a single non-coding body size variant in ancient and modern canids. Current Biology 2022, 32, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, C.; Paoloni, M.C. Cancer biology in dogs. In The Dog and its Genome; Ostrander, E.A., Giger, U., Lindblad-Toh, K., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, New York, 2006; pp. 451–472. [Google Scholar]

- Tyner, S.D.; Venkatachalam, S.; Choi, J.; Jones, S.; Ghebranious, N.; Igelmann, H.; Lu, X.; Soron, G.; Cooper, B.; Brayton, C.; et al. p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes. Nature 2002, 415, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemand, I.; Anglo, A.; Jeantet, A.-Y.; Cerutti, I.; May, E. Testicular wild-type p53 expression in transgenic mice induces spermiogenesis alterations ranging from differentiation defects to apoptosis. Oncogene 1999, 18, 6521–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, B.; Gluba, W.; Bernier, B.; Turner, T.; Mohammad, K.; Guise, T.; Sutherland, A.; Thorner, M.; Scrable, H. Modulation of mammalian life span by the short isoform of p53. Genes & development 2004, 18, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, C.; Snyder-Mackler, N.; Promislow, D.E.L. How size and genetic diversity shape lifespan across breeds of purebred dogs. GeroScience 2023, 45, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, G.; Karlsson, E.K.; Perri, A.; Webster, M.T.; Ho, S.Y.W.; Peters, J.; Stahl, P.W.; Piper, P.J.; Lingaas, F.; Fredholm, M.; et al. Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 8878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, H.G.; Dreger, D.L.; Rimbault, M.; Davis, B.W.; Mullen, A.B.; Carpintero-Ramirez, G.; Ostrander, E.A. Genomic analyses reveal the influence of geographic origin, migration, and hybridization on modern dog breed development. Cell Reports 2017, 19, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- vonHoldt, B.M.; Pollinger, J.P.; Lohmueller, K.E.; Han, E.; Parker, H.G.; Quignon, P.; Degenhardt, J.D.; Boyko, A.R.; Earl, D.A.; Auton, A.; et al. Genome-wide SNP and haplotype analyses reveal a rich history underlying dog domestication. Nature 2010, 464, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinding, M.-H.S.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Ramos-Madrigal, J.; de Manuel, M.; Pitulko, V.V.; Kuderna, L.; Feuerborn, T.R.; Frantz, L.A.; Vieira, F.G.; Niemann, J. Arctic-adapted dogs emerged at the Pleistocene–Holocene transition. Science 2020, 368, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.K.; Darwent, C.M.; Wictum, E.J.; Sacks, B.N. Using multiple markers to elucidate the ancient, historical and modern relationships among North American Arctic dog breeds. Heredity 2015, 115, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerborn, T.R.; Appelt, M.; Bougiouri, K.; Bachmann, L.; Nielsen, I.B.; Buckley, R.M.; Egevang, C.; Diaz-Maroto, P.F.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Gotfredsen, A.B.; et al. Origins and diversity of Greenland’s Qimmit revealed with genomes of ancient and modern sled dogs. Science 2025, 389, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, A.; Frantz, L.; Schmidt, R.; Ersmark, E.; Lebrasseur, O.; Girdland-Flink, L.; Lin, A.T.; Storå, J.; Sjögren, K.-G.; Anthony, D.; et al. Origins and genetic legacy of prehistoric dogs. Science 2020, 370, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, A.; Stanton, D.W.G.; Taron, U.H.; Frantz, L.; Sinding, M.-H.S.; Ersmark, E.; Pfrengle, S.; Cassatt-Johnstone, M.; Lebrasseur, O.; Girdland-Flink, L.; et al. Grey wolf genomic history reveals a dual ancestry of dogs. Nature 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-j.; Wang, G.-D.; Ma, P.; Zhang, L.-l.; Yin, T.-T.; Liu, Y.-h.; Otecko, N.O.; Wang, M.; Ma, Y.-p.; Wang, L. Genomic regions under selection in the feralization of the dingoes. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, A.H.; Gronau, I.; Schweizer, R.M.; Ortega-Del Vecchyo, D.; Han, E.; Silva, P.M.; Galaverni, M.; Fan, Z.; Marx, P.; Lorente-Galdos, B. Genome sequencing highlights the dynamic early history of dogs. PLoS Genet 2014, 10, e1004016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, P.; Leitner, T.; Wilton, A.N.; Matisoo-Smith, E.; Lundeberg, J. A detailed picture of the origin of the Australian dingo, obtained from the study of mitochondrial DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 12387–12390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balme, J.; O’Connor, S.; Fallon, S. New dates on dingo bones from Madura Cave provide oldest firm evidence for arrival of the species in Australia. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 9933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borge, K.S.; Tønnessen, R.; Nødtvedt, A.; Indrebø, A. Litter size at birth in purebred dogs—A retrospective study of 224 breeds. Theriogenology 2011, 75, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagel, M. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature 1999, 401, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025.

- Orme, D.; Freckleton, R.; Thomas, G.; Petzoldt, T.; Fritz, S.; Isaac, N.; Pearse, W. Package ‘caper’: Comparative Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R, 1.0.3 2023.

- Pagel, M.; O’Donovan, C.; Meade, A. General statistical model shows that macroevolutionary patterns and processes are consistent with Darwinian gradualism. Nature communications 2022, 13, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Sadle River, NJ, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Warton, D.I.; Hui, F.K. The arcsine is asinine: the analysis of proportions in ecology. Ecology 2011, 92, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.D. The moulding of senescence by natural selection. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1966, 12, 12–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medawar, P.B. An Unsolved Problem of Biology; H. K. Lewis: London, 1952; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, M.; Hasegawa, A.; Hosoi, Y.; Sugiura, K. A current life table and causes of death for insured dogs in Japan. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2015, 120, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.W.; Abhayaratne, B.M.; Blott, S.C. Trends in genetic diversity for all Kennel Club registered pedigree dog breeds. Canine Genetics and Epidemiology 2015, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, J.F.; Kimura, M. An Introduction to Population Genetics Theory; Harper & Row: New York, 1970; p. pp. xiv, 591. [Google Scholar]

- American Kennel Club. The American Kennel Club. Available online: https://www.akc.org.

- Corbett, L.K. Australia and Oceania (Australasian). In Canids: Foxes, Wolves, Jackals, and Dogs: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan; Sillero-Zubiri, C., Hoffmann, M., Macdonald, D.W., Eds.; IUCN--The World Conservation Union, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S. Australian Mammals: Biology and Captive Management; CSIRO publishing, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- The Royal Kennel Club. The Kennel Club. Available online: https://www.thekennelclub.org.uk.

- Purina. Greenland Dog. Available online: https://www.purina.co.uk/find-a-pet/dog-breeds/greenland-dog#no-back.

- PetGuide.com. Korean Jindo. Available online: https://www.petguide.com/breeds/dog/korean-jindo/.

- San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. New Guinea Singing Dog. Available online: https://sdzwildlifeexplorers.org/animals/new-guinea-singing-dog.

- Wisdom Panel. New Guinea Singing Dog. Available online: https://www.wisdompanel.com/en-us/dog-breeds/new-guinea-singing-dog.

- Fetch, Pet Care. Breed Breakdown: The Tibetan Mastiff. Available online: https://www.fetchpetcare.com/blog/breed-breakdown-the-tibetan-mastiff/.

| Large | Giant | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, x (yr) | lx | mx | lxmx | lx | mx | lxmx | ||

| 2 | 0.9818 | 8.3 | 8.1358 | 0.9620 | 8.8 | 8.4272 | ||

| 3 | 0.9754 | 8.5 | 8.3137 | 0.9494 | 9.0 | 8.5416 | ||

| 4 | 0.9675 | 8.3 | 8.0173 | 0.9359 | 8.5 | 7.9770 | ||

| 5 | 0.9500 | 8.3 | 7.8723 | 0.8914 | 7.5 | 6.6480 | ||

| 6 | 0.9357 | 7.8 | 7.3107 | 0.8320 | 6.3 | 5.2201 | ||

| 39.6497 | 36.8140 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).